Despite a seasonal vaccine and multiple therapeutic treatments, influenza A remains a significant threat to human health. The biggest obstacle in producing a vaccine or treatment for influenza A is their universality or efficacy against not only seasonal variances in the influenza virus but also all human, avian, and swine serotypes and, therefore, potential pandemic strains.

KEYWORDS: influenza A, M2e, monoclonal antibody, treatment, universal

ABSTRACT

Influenza virus infection causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Humans fail to make a universally protective memory immune response to influenza A. Hemagglutinin and neuraminidase undergo antigenic drift and shift, resulting in new influenza A strains to which humans are naive. Seasonal vaccines are often ineffective, and escape mutants have been reported to all treatments for influenza A. In the absence of a universal influenza A vaccine or treatment, influenza A will remain a significant threat to human health. The extracellular domain of the M2-ion channel (M2e) is an ideal antigenic target for a universal therapeutic agent, as it is highly conserved across influenza A serotypes, has a low mutation rate, and is essential for viral entry and replication. Previous M2e-specific monoclonal antibodies (M2e-MAbs) show protective potential against influenza A; however, they are either strain specific or have limited efficacy. We generated seven murine M2e-MAbs and utilized in vitro and in vivo assays to validate the specificity of our novel M2e-MAbs and to explore the universality of their protective potential. Our data show our M2e-MAbs bind to the M2e peptide, HEK cells expressing the M2 channel, as well as influenza virions, and MDCK-ATL cells infected with influenza viruses of multiple serotypes. Our antibodies significantly protect BALB/c mice that are highly susceptible to influenza A virus from lethal challenge with H1N1 A/PR/8/34, pH1N1 A/CA/07/2009, H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004, and H7N9 A/Anhui/1/2013 by improving survival rates and weight loss. Based on these results, at least four of our seven M2e-MAbs show strong potential as universal influenza A treatments.

IMPORTANCE Despite a seasonal vaccine and multiple therapeutic treatments, influenza A remains a significant threat to human health. The biggest obstacle in producing a vaccine or treatment for influenza A is their universality or efficacy against not only seasonal variances in the influenza virus but also all human, avian, and swine serotypes and, therefore, potential pandemic strains. The extracellular domain of the M2-ion channel (M2e) has huge potential as a target for a vaccine or treatment against influenza A. It is the most conserved external protein on the virus. Antibodies against M2e have made it to clinical trials but have not succeeded. Here, we describe novel M2e antibodies produced in mice that are protective at low doses; we also extensively tested them to determine their universality and found them to be cross protective against all strains tested. Additionally, our work begins to elucidate the critical role of isotype for an influenza A monoclonal antibody therapeutic.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza is a health concern worldwide. Despite the development of an influenza vaccine in the 1940s, we remain subject to seasonal outbreaks and the use of seasonal influenza vaccines (1). This is because influenza’s high mutation rate induces changes in the virus’ most immunogenic regions, and these regions are particularly tolerant to mutations (i.e., the globular head domain of hemagglutinin). This process, or antigenic drift, is the reason we need seasonal vaccination (2, 3). Influenza A virus (IAV) is also capable of antigenic shift, or abrupt changes in the virus, which has caused four pandemics since 1900 and potentially more going back to even the Middle Ages (2, 4, 5). Antigenic shift can even cause the seasonal influenza vaccine to be completely ineffective (1).

Treatments for influenza have been developed and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved as recently as October 2018 (2, 6, 7). However, there is no current influenza treatment to which viral escape mutants have not been isolated (8, 9). Considering the variability in the efficacy of the influenza vaccine and the potential of an IAV pandemic, it is critical to develop a treatment for IAV which is universal and avoids viral escape mutants.

We aimed to produce such a treatment. Considering that antibody-mediated responses are protective against IAV infection and the basis of seasonal influenza vaccines (10), we were determined to produce antibody therapeutics. We chose to target the highly conserved extracellular domain of the matrix 2 protein (M2e) and to use an M2e vaccine which uses gold nanoparticles (AuNP) and soluble CpG as an adjuvant (sCpG), the AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccine, in mice for the production of our M2e-specific antibodies (11, 12). This vaccine has been shown to induce protection against H1N1 A/PR/8/1934 (PR8), pH1N1 A/CA/07/2009 (CA07), H3N2 A/Victoria/3/75, and H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (VN1203) (12, 13).

M2e-specific monoclonal antibodies (M2e-MAbs) are protective against IAV (11, 14). However, many M2e-MAbs are limited in their binding to different strains and develop escape mutants (15, 16). The most in-depth studies have been completed on M2e-MAb 14C2, which induces protection against recognized strains partially through limiting viral budding, of which the degree is dependent on other mutations in the virus (15, 17). While the human M2-MAb TCN-032 targets a more conserved epitope present in 99.8% of IAV strains (cross species) than 14C2 and some of the other murine antibodies, TCN-032 showed limited protection in clinical trials (18, 19). There was a 35% overall reduction in symptoms and a reduction in viral load, as well as a reduction in viral shedding in patients treated with TCN-032. However, the length of illness and reduction in grade 2 symptoms were not significantly decreased. These studies were completed with patients who were treated with TCN-032 1 day postinfection (19). Considering the limitations of TCN-032 when administered so early in infection, it is concerning that it might have greater limitations when administered in a clinical setting, where patients do not present symptoms until 1 or 2 days postinfection (20).

Upon considering the robust and lifelong antibody response produced by the AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccination and its potentially universal protection in mice, we were determined to produce M2e-specific antibodies in mice utilizing the AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccine (21, 22). In comparison, TCN-032 was produced from a patient antibody isolate (18). We hypothesized that M2e-MAbs produced from a vaccine that appears to confer universal protection in mice will potentially bind to universal epitopes. Additionally, by utilizing mice to produce the M2e-MAbs, we could take advantage of the use of a vaccine, repeated administrations, and spleen harvesting immediately after stimulation. Finally, the B cell which produced TCN-032 was isolated from a patient’s peripheral blood; it represents 1 of 17 M2e-specific B cells isolated from 23 seropositive patients from a cohort of 140 adults (18). By using a mouse to produce the monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), we can not only enhance B cell affinity maturation through repeated and directed vaccination but also isolate many splenic B cells immediately after a vaccination boost. We generated seven antibodies produced by the AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccine and analyzed the potential of our antibodies as universal treatments for IAV using BALB/c mice, which are highly susceptible to and an established model of IAV infection (20). Importantly, our data establish that several of our M2e-MAbs universally recognize and protect against influenza A. Our M2e-MAbs show unprecedented cross protection against influenza A strains, and further analysis of the M2e-MAbs’ immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses points to previously unappreciated contributions of IgG3 subclasses to host protection from influenza A virus infection.

RESULTS

The production of M2e-MAbs and their confirmation.

To maximize B cell affinity maturation, we vaccinated mice with AuNP-M2e-CpG three times 21 days apart and harvested spleens 10 weeks later. Three days prior to spleen removal, mice were boosted with an additional fourth dose of AuNP-M2e-CpG vaccination (Fig. 1A). The mouse selected for hybridoma production had high M2e-specific serum antibody titers for total IgG and both IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses, prior to the vaccination boost (Fig. 1B). Of 68 hybridoma clones, 7 were found to be M2e peptide specific by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Table 1, Fig. 2A to D).

FIG 1.

The production of monoclonal antibodies. (A) Diagram containing all time points for vaccination and spleen harvest for hybridoma production. (B) M2e peptide was used as the coating antigen for ELISAs. Serum from specified mice and time point was added. Positive-control mouse serum was taken 21 days postvaccination, and negative-control serum is from a naive BALB/c mouse. M2e-specific titer was detected by a total IgG or subclass-specific secondary antibody. OD490, optical density at 490 nm. n = 18 to 19; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies and their IgG subclasses

| Clone name | IgG subclass |

|---|---|

| 391 | IgG1 |

| 472 | IgG2a |

| 522 | IgG1 |

| 602 | IgG2a |

| 770 | IgG2a |

| 934 | IgG3 |

| 1191 | IgG2b |

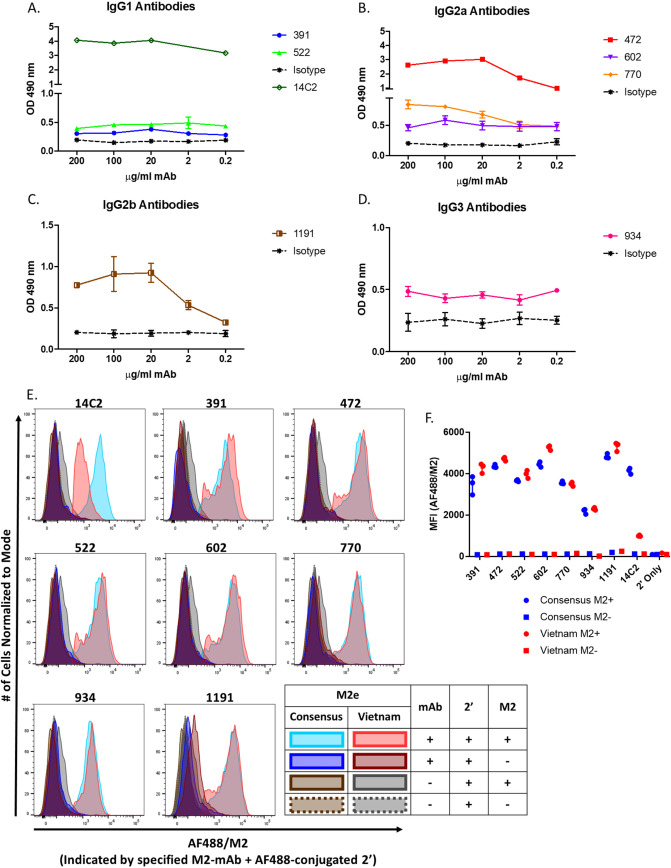

FIG 2.

Seven generated monoclonal antibodies are M2e specific. (A to D) Coating antigen for ELISAs was the vaccine sequence M2e peptide. Antibodies were added at specified concentrations. M2e-specific binding was detected by a total IgG secondary antibody. OD490, optical density at490 nm. n = 1 to 3 (seven 14C2 wells were beyond detection). (E and F) M2 expression was induced in 293 cells with tetracycline. 14C2 or the indicated MAb clone binding was confirmed by flow cytometry detecting secondary staining with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody. Binding of M2e-MAb to M2-expressing 293 cells graphed as population histograms (E) or mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of AF488 (F). Sequence of M2 is specified in the figure legend (consensus or Vietnam).

Knowing that the 7 M2e-specific antibodies bound to M2e peptide via ELISA, we tested to see if these antibodies bound to the homotetrameric form of the protein. For this analysis, we compared the binding of our antibodies to two HEK cell lines which can be induced by tetracycline to express the consensus or VN1203 M2 channel sequences. VN1203 contains three mutations in the M2e region divided over the most variable region in M2e (between amino acids [aa] 11 and 20) (Table 2). By flow cytometry, we confirmed that each of our antibodies bound strongly and similarly to M2 expressed by both HEK cell lines, demonstrating their ability to bind to the native conformation of the channel and suggesting that epitopes of these M2e-MAbs are potentially in more highly conserved regions of M2e. Additionally, we tested 14C2 as a control, which as expected bound strongly to the consensus sequence but showed decreased binding to the sequence of VN1203 due to a mutation (I11T) within the 14C2 epitope (Fig. 2E and F) (18). 14C2 is the most broadly available M2e-MAb and was the first produced. It is widely tested and shown to recognize only specific strains (15, 17), preventing its use as a universal influenza therapeutic. The use of 14C2 as a control confirms not only our assay’s sensitivity but also that our antibodies all bind to an epitope that is distinct from that of 14C2.

TABLE 2.

M2e sequences of influenza A viruses from humans, birds, and swine compared with the consensus sequencea

M2e sequences of viruses used in experiments, including viruses from humans, birds, and swine for the M2e sequence (11, 12). The consensus is derived from seasonal influenza viruses circulating since 1957 (H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2; shown). The table also includes the vaccine sequence used in the AuNP-M2e-CpG vaccine. The vaccine sequence substitutes serine (S) for the cysteines (Cs) in the M2e consensus sequence to prevent cross-linking sulfide bonds between AuNPs (12). Changes made for the AuNP-M2e-CpG vaccine are shown in red. Mutations from the consensus sequence are shown in blue. The epitope for 14C2 is shown on the consensus sequence in gray. Additionally, recognition by the M2e-MAb 14C2 of each of these strains (reported in the studies referenced by binding to peptide [P] or infected cells [I]) is indicated as positive (+); if relative values are reported, positive binding but less than half of consensus/positive-control binding (<+); or negative (−) next to the name of the strain under the virus column (15, 18, 26). *, indicates we confirmed the binding of 14C2 to this strain within our experiments. Note, we did not find binding results for 14C2 for Anhui1 or swTX. However, it is unlikely 14C2 binds to these M2e sequences, as swTX has the same mutations in 14C2’s epitope as CA07, to which 14C2 does not bind, and Anhui1 has mutations in the same positions as CA07 (positions 11 and 13) and an additional mutation (position 14), for a total of 3 mutations in the epitope of 14C2.

M2e-MAbs bind to influenza A-infected cells and virions.

We next wanted to determine if the antibodies were able to bind the M2 protein in a less artificial system and further test their universal potential. We performed infected cell ELISAs by testing eight IAV strains, as follows: PR8, CA07, FM1, swNE, swTX, swMO, VN1203, and Anhui1. These viruses have considerable diversity in M2e sequences (Table 2) and also represent zoonotic and pandemic threats. We saw strong binding by antibodies 391, 472, 522, 602, and 1191 to all strains, suggesting they bind to highly conserved epitopes. The binding of antibody 770 was comparatively lower against all strains and specifically against CA07. Antibody 934 showed low binding to all strains (Fig. 3A to H). Binding of the NP-specific MAb was low for all assays, demonstrating the cells were intact and that the M2-specific MAbs were binding epitopes on the surface of infected cells. Additionally, the binding of most antibodies appeared to remain high at low doses, and to further investigate this, we wanted to analyze the binding kinetics of each antibody.

FIG 3.

M2e-MAbs bind to influenza A-infected cells. (A to H) MDCK-ATL cells, infected with the indicated virus at an MOI of 0.5 for 12 hours, were used as the coating antigen for ELISAs, and the indicated MAb clone was tested for virion reactivity. MAb H16-L10, specific for theinternal nucleoprotein (NP), was used as a control demonstrating cells were intact and not permeabilized. Background staining of uninfected MDCK-ATL cells was subtracted. OD450, optical density at 450 nm. (I and J) Bmax and Kd values were calculated in GraphPad Prism 7.02 using a nonlinear best fit regression for one-site specific binding.

Influenza A-infected cell and viron ELISAs are the most translationally relevant assays for evaluating the binding of M2e-MAbs in vitro. They allow for M2e-MAb binding to M2e in its native conformation and as a homotetramer, which is critical, as the M2e conformation has been shown to be important for the binding of multiple antibodies, and some M2 antibodies have been found to bind between 2 M2e on a tetramer (23–25). We determined both the maximum binding (Bmax) and equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) for our seven M2e-specific antibodies to determine the their binding efficiency at low doses. The Bmax is the highest binding (expressed as optical density [OD]) the antibody can achieve with a given amount of epitope. Kd represents the concentration (mg/ml) at which the antibody is binding at half its Bmax. Therefore, the higher the Bmax and lower the Kd, the more efficient the binding, indicating that an antibody would be effective at low doses. Bmax values varied by strain. However, 391, 472, 522, and 602 consistently showed the highest binding for all viruses (Fig. 3I). We found that nearly all our antibodies had low Kd values for all viruses; the only Kd values above 4.0 μg/ml were for 472 binding to H7N9 (6.1 μg/ml) and for 934 (Fig. 3J). These results indicate that most of our antibodies bind efficiently to M2 expressed on cells infected by a variety of viruses, demonstrating their universality. Additionally, these antibodies are expected to target infected cells via Fc receptor-mediated pathways. Many of these pathways have already been indicated as pathways by which M2e-specific antibodies protect against influenza (11, 26–29).

M2 is more highly expressed on infected cells than influenza virions (15, 30). However, some M2e-specific antibodies have been shown to bind to influenza virions and induce protection through partial neutralization by preventing membrane scission or blocking ion channel activity (15, 17, 31). Therefore, we tested to see if our antibodies were capable of binding to influenza virions from the eight different influenza strains tested in virion ELISAs. Excitingly, antibodies 391, 472, 522, 601, and 1191 bound to all influenza virions. Antibody 770 showed moderate binding to all strains with the exceptions of CA07 and swNE. Again, we observed weak binding from 934 and no binding with the NP-specific MAb (Fig. 4A to H). Kinetic analysis revealed consistently high Bmax and low Kd values from most of our antibodies, except 770 and 934. Antibody 770 displayed highly variable Bmax and Kd values, and 934 showed results consistent with its low binding (Fig. 4J and K).

FIG 4.

M2e-MAbs bind to influenza virions. (A to H) Specified influenza A virions were used as the coating antigen for ELISAs, and the indicated MAb clone was tested for virion reactivity. MAb H16-L10 was used as a control demonstrating virions were intact. Background was subtracted.OD450; optical density at 450 nm. (I) Plaque assay with PR8 using virus preincubated with 25/ml of specified M2e-MAb or adamantane. n = 3, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test. (J and K) Bmax and Kd values were calculated in GraphPad Prism 7.02 using a nonlinear best fit regression for one-site specific binding.

Considering that our antibodies bind to both infected cells and influenza virions and that the binding of virions to the ELISA plate can alter the virion and protein structures, we also directly tested if our antibodies are capable of viral neutralization. We tested our viral propagation in MDCK2 cells via plaque assay with 25 µg/ml of one of our M2e-MAbs or a control (14C2 or adamantane). We found that 934 was the only MAb that significantly inhibited viral replication in MDCK2 cells, despite low binding in the infected cell and virion ELISAs. It is possible that 934 binds more effectively to free virions. Three other MAbs, namely, 472, 602, and 770, also trended toward partially neutralizing infection. Only the positive controls, 14C2 and adamantanes, completely limited viral replication of MDCK2 cells (Fig. 4I).

Our results demonstrate that five out of seven of our antibodies strongly bind the M2 protein expressed by infected cells and influenza virions via ELISA. The eight strains tested represent the variety in M2e sequences in humans, birds, and swine, including H5N1 and H7N9 viruses that are considered pandemic threats. Our data further indicate that our antibodies may be capable of targeting both infected cells and influenza virions, suggesting potential protection through diverse antibody-mediated mechanisms, although they are likely nonneutralizing mechanisms. Finally, the variety of M2e sequences tested confirms that many of these antibodies bind to highly conserved epitopes and are likely candidates to provide universal protection against IAV.

M2e-MAbs protect BALB/c mice from lethal PR8 infection even at low doses.

To determine if our M2e-specific antibodies’ high binding efficiency to influenza-infected cells and virions translated to protection, we challenged our mice with a 5× 50% lethal dose (LD50) of PR8 after prophylactic administration of each M2e-specific antibody. Additionally, we titrated the dose of each antibody to determine their individual efficacy. The antibodies displayed various degrees of protection, which for the most part correlated with their binding results via ELISA (Fig. 5A to G). While 391 displayed high binding to PR8-infected cells and virions, the protection provided by 391 appears to be limited, as protection did not increase with dosage (Fig. 5A). All other antibodies which were protective increased protection in a dose-responsive manner. Antibodies 472 and 602 were the most protective antibodies, providing slight protection at as low as 25 μg (Fig. 5B and D). Furthermore, as 770 was also very protective, it appears that IgG2a antibodies are a protective IgG subclass against IAV infection, which is consistent with the literature (32, 33). IgG subclass and binding specificity both play a role in our protection study results, as the IgG2b MAb 1191 is not very protective, despite strong binding, and it is established that IgG2b antibodies are generally more inhibitory than IgG2a (Fig. 5G) (34, 35). The most unexpected result was that 934 was highly protective (Fig. 5F), despite limited binding to M2e peptide, virions, or infected cells and despite it being an IgG3 isotype, which is not traditionally known for strong Fc receptor-mediated functions; although, it is reported to potentially have an alternative integrin receptor for inducing phagocytosis (36–39). It is possible this is related to 934’s partial neutralization of the virus in vitro.

FIG 5.

M2e-MAbs protect from lethal PR8 challenge. (A to G) BALB/c mice were passively immunized with indicated dose of M2e-MAb clone 1 day prior to infection with 5× LD50 H1N1 A/PR/8/34. n is indicated for each graph. Experiments wereperformed at BCM, and endpoint was considered weight loss cut off at 30%. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; log-rank analysis. *, indicates significance compared with PBS control; #, indicates significance compared with isotype control. Percent weight loss data for survival analysis are shown to the right of each graph. Weight loss was analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test to compare weights between groups on individual days. Heatmap below each weight loss curve is indicative of significantly different weight loss from control group. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; log-rank analysis. *, indicates significance compared with PBS control, unless all PBS controls died in which case treatment groups were compared with isotype control. Black indicates a group is no longer included in comparisons; either all mice in that group were dead at time point of comparison (B) or in the case of the isotype control, if all PBS animals have died, this became the control group (A, E, F, and G). Results for curve mean comparisons of days 0 to 14 postinfection by a 2-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s comparison are shown to the left of the heatmap; *, indicates significance compared with PBS control; and #, indicates significance compared with isotype controls with (L) or if necessary to indicate low or high isotype control dose (H). If entire control group died before day 14, the comparison includes only days with weights for the control group.

We have included weight loss data for all experiments. Most of our antibodies significantly improve weight loss in mice in a dose-dependent manor. However, it is important to note that as these antibodies are nonneutralizing, as in they do not prevent infection, therefore, we expected to and do see weight loss in all groups.

Many of our antibodies are highly protective against PR8. Apart from the surprising results concerning 391 and 934, most antibodies showed results consistent with their binding to PR8-infected cells and virions. Antibodies 472, 522, and 602 all displayed strong binding efficiency and are protective. Antibody 770 bound more moderately to all strains than many of the other antibodies; however, its relatively strong protection against PR8 suggests that it might also be protective against the other viruses despite its moderate binding via ELISA.

M2e-MAbs show universal potential, protecting BALB/c mice from lethal pH1N1 A/CA/07/2009, H5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004, and H7N9 A/Anhui/1/2013 infection.

To further test the protection provided by our M2e-MAbs and to determine the universality of that protection, we prophylactically treated mice with a low dose (25 μg) or a high dose (100 μg) of five or six M2e-MAbs with functional IgG subtypes and challenged them with 10× LD50 of CA07, VN1203, or Anhui1.

CA07 is a pandemic strain isolated early in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and is related to the current circulating H1N1 strain. All M2e-MAbs were at least partially protective against pH1N1. Antibody 770 was the least protective, and while it delayed disease progression, almost all mice treated with the low and high dose eventually succumbed to disease. This is consistent with the low binding of 770 to this variant of the M2 channel in all ELISA results. All other antibodies improved with increasing dosage. Antibodies 391, 522, and 934 increased from 40% to 50% protection at 25 μg to 80% protection with the 100-μg dose. Antibody 472 increased from 70% protection to 100%. Antibody 602 was the most effective antibody against CA07 challenge, protecting 100% of mice at the low and high doses (Fig. 6A and B). M2e-MAbs also significantly decreased weight loss, especially 602 (Fig. 6A and B). However, none of the antibodies induced a decrease in viral titer at day 3 (Fig. 7A).

FIG 6.

M2e-MAbs protect from lethal influenza A infection. (A to G) BALB/c mice were passively immunized with indicated dose of M2e-MAb clone 1 day prior to infection with CA07 (A and B), VN1203 (C to E), or Anhui1 (F and G). Experiments performed at UGA were monitoredhumane endpoints based on comprehensive point system evaluating weight and clinical signs. (A, B, D, E, F, and G) n = 10. (C and H) n = 5. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; log-rank analysis. *, indicates significance compared with PBS control; #, indicates significance compared with isotype control. Percent weight loss data for survival analysis are shown to the right of each graph. Weight loss was analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test to compare weights between groups on individual days. Heatmap below each subfigure is indicative of significantly different weight loss from control group. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; log-rank analysis. *, indicates significance compared with PBS control, unless all PBS controls died in which case treatment groups were compared with isotype control (indicated by black squares; C, D, F, and G). Results for curve mean comparisons of days 0 to 14 postinfection by a 2-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s comparison are shown to the left of the heatmap; *, indicates significance compared with PBS controls; #, indicates significance compared with isotype controls. If entire control group died before day 14, comparison only includes days with weights for control group.

FIG 7.

M2e-MAbs viral titers at day 3 after lethal influenza A infection. (A to C) BALB/c mice were passively immunized with indicated dose of M2e-MAb clone 1 day prior to infection with CA07 (A), VN1203 (B), or Anhui1 (C). Lungs for viral titers were removed on 3 dpi. Viral titers were determined through a TCID50. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; log-rank analysis.

In challenges with a 10× LD50 of highly virulent VN1203, we found that 25 μg of 391, 472, and 522 administered prophylactically was significantly protective (Fig. 6C). Antibodies 391, 472, 522, 602, and 934 were each partially protective at one or both doses, with 100 μg of 934 protecting 90% of mice (Fig. 6D). Because many of our antibodies were still partially protective against this virus, we increased the prophylactic dose to 200 μg to determine if we could see an additional dose-dependent improvement. We found that 200 μg of 472, 522, 602, and 770 administered prophylactically was extremely protective. Antibodies 472, 522, and 770 were each 100% protective, while 602 was 80% protective (Fig. 6E). These results are consistent with the strong binding of all these antibodies to HEK cells expressing M2 from this virus, as well as its virions and infected cells. Additionally, considering that 602 bound to this virus at the lowest levels out of all eight virions tested, it is promising that it is 80% protective. Additionally, we did see a significant reduction in viral titer in mice treated with 100 μg of 472 (Fig. 7B) and report significantly decreased weight loss with all antibodies (Fig. 6C to E).

Finally, for Anhui1 challenges, all antibodies tested (391, 472, 522, 602, and 770) were extremely protective at both low and high MAb doses. Only four mice cumulatively from all treatment groups reached humane endpoints from the 10× LD50 challenge (Fig. 6F and G). The dose 25 μg of 770 and 522 protected 80% and 90% of the mice, respectively, and 472 protected 90% of mice with a 100 μg dose. All other groups, including the 25-μg dose of 472, survived at 100%. All the antibodies displayed strong binding to Anhui1 in virion ELISAs. Again, we saw a significant reduction in viral titer in mice treated with 100 μg of 472 (Fig. 7C) and significantly lower weight loss in treated mice (Fig. 6F and G).

These results demonstrate that our M2e-specific antibodies are not only protective against the lab strain PR8 but also highly protective against avian and swine-origin influenza viruses. To determine the efficacy of our antibodies comparatively between these different strains, we plotted the protection provided against each strain of virus against each MAb dose tested (Fig. 8A to G). Antibody 472 followed by 602 seemed the most highly protective against all strains (Fig. 8B and D). Antibodies 391 and 522 are strongly protective against CA07, VN1203, and Anhui1. However, that protection decreases to low levels against PR8 (Fig. 8A and C). Because these four antibodies appear to bind strongly to all these strains via ELISA, it is possible that this difference in protection is IgG subclass dependent, as 472 and 602 are IgG2a antibodies and 391 and 522 are IgG1 antibodies (Fig. 8H and I). This is consistent with literature comparing the Fc-mediated protection of M2e-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies (32). 770, another IgG2a antibody, is less universally protective. However, the protection provided by 770 appears to be correlated with its ability to bind to the channel measured via ELISA. 770 is strongly protective against Anhui1, moderately protective against PR8 and VN1203, and not protective against CA07 (Fig. 8E). These results seem to correlate with ELISA data demonstrating moderate binding to PR8, VN1203, and Anhui1, but limited to no binding to CA07 (Fig. 8H and I). Despite negative results for binding in our ELISAs, 934 was highly protective against all strains we tested (Fig. 8F, H, and I). Finally, 1191 does not protect, likely due to its being an IgG2b antibody, which is generally more immune suppressive than IgG2a subclass antibodies (34, 35), despite high binding in ELISAs (Fig. 8G, H, and I). Overall, at least 5 of our antibodies, namely, 391, 472, 522, 602, and 934, show high potential for universal protection in murine models. Additionally, 770 shows high protection against many strains despite lower binding results than the other antibodies. These results strongly suggest that these antibodies are protective against the additional strains tested in our ELISA studies. The protection provided to all these strains implies that these antibodies have potential as a universal IAV therapeutic.

FIG 8.

Cross-protective analysis of M2e-MAb protection from lethal influenza A infection. (A to G) BALB/c mice were passively immunized with the indicated dose of M2e-MAb clone 1 day prior to infection with 5× LD50 H1N1 A/PR/8/34, 10× LD50 CA07,10× LD50 VN1203, or 10× LD50 Anhui1. Each graph represents the combined data from Fig. 5 and 6, as well as additional experiments divided by antibody. The number of experiments included in each data set and the R squared values of each line of best fit are included in Table 2. PBS groups were considered the baseline 0-µg dose for both treatment and isotype groups within the same experiment. All experiments, n = 8 to 10. H1N1 A/PR/8/34 experiments performed at BCM, and endpoint was considered weight loss cut off of 30%. A/CA/07/2009, VN1203, and Anhui1 experiments performed at UGA monitored humane endpoints based on comprehensive point system evaluating clinical signs and weight loss. Trend lines were determined analyzed by both linear and nonlinear regression and the appropriate trendline, and the most appropriate trend line was determined by the R squared value. If only data points were 100% survival, the line connecting data points is displayed rather than a nonlinear curve with an R2 of 1. If R squared value is below 0.4, average means were connected by a line. (H and I) Heatmap created using the absorbance of each antibody at 100 μg/ml when binding to infected cells (H) or virions (I) via ELISA for comparison between antibodies. Raw data are in Fig. 3 and 4.

DISCUSSION

The influenza vaccine is subject to both antigenic drift and antigenic shift. In the absence of a consistent and effective vaccine for IAV, we need effective therapeutics for seasonal epidemics and potential pandemics. The six FDA-approved antiviral drugs for influenza infection include two M2 channel blockers or adamantanes, three NA inhibitors, and one endonuclease inhibitor (2, 6, 7). None of these treatment options avoids the development of viral resistance. Mutations preventing adamantane binding and have made this class of drugs completely ineffective for the past decade (8, 40, 41). While transmission of NA inhibitor-resistant strains has been limited and thus far only single or double NA inhibitor drug resistance, the high rate of development of viral resistance in several studies and the isolation of additional mutations which increase the transmission of these viruses are cause for alarm (8, 42–45). Finally, in clinical trials with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil, the virus did develop resistance to in some patients (46).

Given the high dependence of current vaccine efforts on predictions of antigenic drift, the emergence of viral resistance in clinical trials or isolates against all current IAV therapies, and the high mortality rate as a result of influenza infections annually, it is necessary to explore other options for treating influenza that would potentially be universally protective. To that end, we considered the potential of an MAb therapy. It is well established that antibody protection is effective against IAV. In fact, the efficacy of seasonal vaccines is partially determined by the titers of neutralizing antibodies (i.e., antibodies which prevent the virus from infecting through binding) (10). However, antibodies also provide protection from IAV through many nonneutralizing mechanisms (33). Nearly all Fc receptor mechanisms have been shown to be effective against IAV (4, 29, 33, 35, 47, 48). While T cell responses also contribute to protection against influenza, the protection provided by antibodies can be sufficient to prevent lethality, as transferred immunized serum and IAV-specific MAbs are protective in animal models (4, 14, 49). M2e serum and M2e-MAbs, specifically, have been found to induce protection through a variety of Fc-dependent mechanisms, including antibody-mediated phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages, NK cell-mediated antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and complement induction (11, 25–27, 50). Depending on the epitope of an M2e-MAb, there are thus a wide variety of mechanisms of protection, including the blocking of ion channel activity, the prevention of membrane scission during viral budding, and the decreasing the expression of M2 on the surface of infected cells (15, 30, 31, 51). Further contributing to the potential of an M2e-MAb therapy, while not meeting efficacy goals, the clinical trials for TCN-032 did not find evidence of the development of escape mutants.

Six of our seven M2e-MAbs developed from the AuNP-M2e-CpG vaccine are a potential universal treatment for IAV. The M2e-specific antibodies we produced bind to M2e expressed on virions and infected cells expressing a range of M2e sequences which represent M2e variations seen in M2 proteins across human, swine, and avian IAVs. This cross-reactivity in binding and/or protection suggests that six of our M2e-MAbs (391, 472, 522, 602, 934, and 1191) bind to a fairly universal epitope. These binding results are similar to those published for TCN-032 (18). Antibody 770, on the other hand, likely binds to a less conserved epitope and has less universal potential, due to its distinct decrease in binding to and protection against some of the strains tested, specifically CA07 and swNE. Antibody 770 has similar, but not the same binding results as those published for 14C2 (Table 2), which also does not recognize CA07 (15, 18, 28).

Furthermore, our results demonstrate the importance of FC-mediated mechanisms and antibody subclass. For over 30 years, studies have attempted to determine the most effective antibody subtypes against IAV. Early studies suggested that IgG2a or IgG2b antibodies were most critical to IAV responses (52, 53). More recent, general antibody studies have suggested that IgG2b antibodies should be more inhibitory than IgG2a and more activating than IgG1 antibodies (34–36). However, IAV-specific studies indicate that IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies are most critical to IAV (32) and published IgG2b subclass MAbs which are protective against IAV are often directed at hemagglutinin (HA) and explicitly or likely neutralizing (54–56). Comparisons of all seven of our antibodies suggest that IgG2a might be the most effective subclass of M2e-MAbs against IAV. However, further analysis of M2e-MAbs with the same variable region and different IgG subclass, as well as M2e-MAb’s protective effector functions, will be critical for determining the most effective and protective IgG subclass for M2e-MAbs.

Confirming the potential for these antibodies to be universally protective, almost all of our M2e-specific antibodies are protective against not only PR8 but also CA07, VN1203, and Anhui1. Highly effective M2e-specific antibodies with strong antiviral IgG subclasses can be titrated down to low doses and remain effective. Antibodies 472 and 602 are protective against PR8 at as low as 25 μg. Furthermore, 25 μg of 391, 472, 522, and 602 is also partially, if not completely, protective against CA07, VN1203, and Anhui1, demonstrating that these antibodies are highly effective against highly virulent avian strains of IAV in vivo. These viral challenges demonstrate protection against avian and swine influenza viruses that are public health concerns (2). Furthermore, the level of cross protection provided by this number of M2e-MAbs is unprecedented. Our ongoing studies are focused on further analysis and optimization of our M2e-MAbs to develop an effective IAV treatment that protects regardless of antigenic drift and shift and the development of effective, low dose therapeutic cocktails of M2e-MAbs to prevent treatment-induced viral escape mutants.

While we hypothesize that our M2e-MAbs can be developed into a universal treatment based on their recognition of and protection against a wide breadth of the variants of M2e, we are conscious of the fact that other M2e-specific antibody treatments have produced escape mutants when tested through in vitro and in vivo passaging (15–17). Further examination of these antibodies, their epitopes, and their ability to avoid escape mutants will be required to determine their potential as an IAV treatment.

However, based on our results, our antibodies are competitive with not only other M2e-MAbs but also other monoclonal therapy approaches against IAV. Compared with HA-stalk MAbs and NA MAbs, there are three critical evaluations, as follows: effective dosage, cross protection, and known effector functions. The doses we report here are competitive with effective doses reported with HA-stalk (33) and NA MAbs (57). In regard to cross protection, while HA-stalk MAbs are cross protective and some have been shown to bind even between HA-stalk groupings (58), two recent issues have developed to possibly hurt their clinical potential, as follows: first, the potential for escape mutants (59); and second, the potential for limited efficacy in patients due to the high numbers of HA-head group antibodies in patient serum, which can block HA-stalk antibody binding (60). NA-specific MAbs have been found to be effective against a variety of influenza A viruses, including H7N9 (59). They are generally NA subtype specific; however, there are some highly conserved epitopes that could increase cross protection (57, 61). M2e-MAbs are also competitive when it comes to effector functions. While HA-stalk MAbs are capable of both neutralizing and Fc receptor-mediated mechanisms to mediate protection (33, 58, 62, 63), Fc receptor mechanisms have been shown to be critical for protection in vivo, suggesting HA-stalk MAbs do not protect predominantly through neutralization (33). NA has also been shown to be capable of inhibiting HA-stalk antibodies from activating Fc receptor-mediated immune mechanisms (64). NA-specific antibodies are thought to predominantly limit viral spread during budding (similar to some M2e-specific MAbs), but not much is known about their activation of Fc receptor-mediated activity (61). Overall, we consider M2e-specific antibodies the most promising option not only because they are competitive in all of these comparisons but also because of how highly conserved the sequence is and because of the selective pressure to maintain the M2e sequence because it shares coding regions with M1 (11, 65).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

At Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), BALB/c mice were ordered from or were bred internally from breeders obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Mice were 6 to 8 weeks old at the start of experiments. All mice were cared for in the animal facilities of the Center for Comparative Medicine at BCM and Texas Children’s Hospital, and all protocols were approved by the BCM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

At University of Georgia (UGA), female BALB/c mice were purchased from Envigo RMS, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA. The institutions’ animal care and use committees approved all protocols for animal experiments.

All institutions follow the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” formulated by the National Society for Medical Research.

AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccination.

The AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccine was prepared as described in Tao et al. (12). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and vaccinated dropwise intranasally with 25 μl of the AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccination [8.2 μg M2e, 60 μg AuNPs, and 20 μg sCpG per animal, as described in Tao et al. (13)].

We vaccinated 3 times 21 days apart prior to boosting, as this protocol has been demonstrated to produce consistently high antibody titers in all IgG subclasses (significantly higher than 2 vaccinations) and to produce memory B cells that can be activated to produce an increased antibody titer even to geriatric age in mice, 16 months postvaccination (12, 13, 21, 22).

Serum isolation.

Blood was collected from the submandibular vein 5 days prior to B cell isolation. Serum was isolated from the blood sample and frozen at −30°C.

Viruses.

At BCM, PR8 was obtained from ATCC and passaged through C57B6/J mice 10 times and BALB/c mice 6 times before isolation and then stored at −80°C. At UGA, human IAVs PR8, CA07, and H1N1 A/FM/1/1947-MA (FM1) were propagated in the allantoic cavity of embryonated chicken eggs at 37°C for 48 h. Avian influenza viruses H7N9 A/Anhui/1/2013 (Anhui1) and VN1203 were propagated in the allantoic cavity of embryonated chicken eggs at 37°C for 18 to 24 h. Swine influenza viruses H1N1 A/sw/NE/A01444614/2013 (swNE), H3N2 A/sw/TX/A01049914/2011 (swTX), and H1N2 A/sw/MO/A01444664/2013 (swMO) were provided via the National Swine Surveillance repository (National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Ames, IA) and propagated in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK-ATL) cells in minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 0.05% tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Worthington) at 37°C for 48 to 72 h. MDCK-ATL cells were obtained from the International Reagent Resource (Influenza Division, WHO Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Atlanta, GA, USA). All experiments using H7N9 or highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus were reviewed and approved by the institutional biosafety program at the UGA and were conducted in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) enhanced containment. Work with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus followed guidelines for use of select agents approved by the CDC. All viruses are wild type (WT; not PR8 background), and the M2e sequence was confirmed within 2 passages.

Virus purification.

At BCM, to purify virus that had been passaged through mice, as described above, the mouse cohort for the final passage were sacrificed using isoflurane overdose, and their lungs were removed and placed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on ice (0.75 ml/lung). Lungs were homogenized and centrifuged at 850 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was placed in an Ultracel-100 tube (Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit; Ultracel-100 regenerated cellulose membrane) and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The solution remaining in the top of the filter tube was placed in a new 15-ml tube and centrifuged at 850 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Finally, the supernatant was aliquoted into cryo tubes for storage at −80°C.

At UGA, IAVs were treated with 1:1000 betapropiolactone (BPL; final concentration of 2 μM) for 72 h at 4°C. Inactivation of human and swine IAVs was verified by plaque assay. Inactivation of avian influenza viruses was confirmed by two passages in embryonated chicken eggs by following protocols approved by the University of Georgia Office of Biosafety and following select agent guidelines. Inactivated virus was spun in a tabletop centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and then 36 ml of the clarified virus was added to a 50-ml ultrafuge tube and spun in ultracentrifuge (ThermoFisher Scientific, Sorvall WX+ ultracentrifuge series, rotor AH-629) at 12,280 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. A total of 30 ml of the clarified supernatant was transferred to a new 50-ml ultrafuge tube, and 5 ml of chilled 30% sucrose in NaCl-Tris-EDTA (NTE) buffer (NaCl-Tris-EDTA buffer) was added to the bottom of the ultrafuge tube. Virus was then pelleted through a sucrose cushion at 77,000 × g for 2 hours at 4°C. Sucrose/media supernatant was aspirated without disturbing the pellet, and the pellet resuspended in 500 μl PBS. The virus was dialyzed (10 kDa molecular weight cut-off [MWCO]; ThermoFisher Scientific) for 12 hours in PBS. Samples were removed from dialysis cassettes, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Virus quantification.

Lungs were homogenized in 1 ml of sterile PBS using a Tissuelyser homogenizer (Qiagen), clarified by centrifugation, and titrated for infectious virus by the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay. The 50% infectious dose was calculated using the method of Spearman-Karber (66).

Hybridoma production.

Hybridoma production was performed by the Protein and Monoclonal Antibody Production Core at BCM. A fusion between mouse splenocytes from the chosen M2e-immunized mouse (442) and the mouse SP2/0-Ag14 myeloma cell line was performed using standard polyethylene glycol (PEG) fusion methodology. Newly formed hybridomas from the fusion were plated in ClonaCell medium D (StemCell Technologies, Inc.), a semisolid methylcellulose-based selection medium, and allowed to grow for 2 weeks prior to identifying, picking, and transferring individual hybridoma clones to wells of prefed 96-well tissue culture plates with the aid of the StemCell Technologies ClonaCell EasyPick robot. The hybridomas were allowed to grow 3 days, and supernatant from the 96-well plates of hybridomas was screened by indirect ELISA for MAbs to the M2e peptide. Those hybridomas showing a strong ELISA reaction were moved up to 24-well tissue culture plates and screened two more times by ELISA to confirm the positive results. Positive hybridomas were expanded in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) + 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen.

Antibody production was performed by expanding the hybridomas in IMDM + 10% super low bovine IgG FBS (HyClone). The hybridomas were allowed to overgrow and the antibody-containing supernatant harvested when the viability was less than 50%. Cells were removed by centrifugation, and the sterile supernatant was stored at 4°C until the mouse MAb was purified using protein G Sepharose.

HEK cell staining and flow.

Matrix protein 2 (M2)-expressing HEK cells were grown according to methods outlined in Gabbard, et al. (67) in Protein Engineering, Design, & Selection and according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Flp-InTM T-RExTM 293 Cell Line system). M2 expression was induced in 293 cells with tetracycline, and cells were trypsinized for 5 minutes with 0.05% trypsin with EDTA. Cells were washed with PBS + 2% FBS. Cells were stained for 20 minutes at room temperature with indicated MAb clone in PBS + 2% FBS. Cells were then washed with PBS + 2% FBS and centrifuged at 600 × g. Cells were then stained with secondary staining with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody, washed again, and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). M2 expression and MAb binding were confirmed by flow cytometry using the commercially available M2e-specific MAb clone 14C2 (IgG1) as the primary antibody.

Peptide ELISAs.

Serum samples at 1:1,000 dilution or specified concentrations of M2e-MAbs were analyzed in triplicate via ELISA (plate, Corning and ref number 9018; lot, 10017015). The M2e peptide was used as the coating antigen for ELISAs [vaccine sequence, specifications reported in Tao et al. (12)]. The vaccine sequence is based on the consensus sequence, which is derived from seasonal influenza viruses circulating since 1957 (H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2; shown). The vaccine sequence used in the AuNP-M2e-CpG vaccine substitutes serine (S) for the cysteines (Cs) in the M2e consensus sequence to prevent cross-linking sulfide bonds between AuNPs (12). All sequences are shown in Table 2. Serum or M2e-MAbs were added, and M2e specificity was detected by an subclass-specific secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Southern Biotech, total IgG: 1030-05; IgG1: 1070-05; IgG2a: 1080-05). Absorbance was measured at 490 nm.

Infected cell ELISAs.

The 96-well tissue culture plates (ThermoFisher Scientific) were seeded with 100 μl/well of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml MDCK-ATL cells and incubated in a 37°C and 5% CO2 incubator for approximately 24 h or until reaching confluence. Plates were washed 3 times with PBS and infected with 50 μl/well of the specified virus diluted in MEM culture medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 for 2 hours; 100 μl/well of overlay (25 ml 2× overlay medium with 25 ml of 2.4% Avicel) was added and incubated in a 37°C and 5% CO2 incubator for 18 to 22 hours. Overlay was aspirated, plates were washed with PBS, and then 100 μl/well of 4% formalin in 1× PBS was added and incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes to fix the plates with limited cell permeabilization. The formalin was washed away with PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and 50 μl of the indicated MAb was added in 4-fold dilutions and incubated at 4°C overnight. The nucleoprotein (NP)-specific MAb H16-L10 was used as a control, demonstrating limited permeabilization. H5N1- and H7N9-infected cells were fixed with 80:20 methanol:acetone for ≥10 minutes, following required BSL3 protocols, resulting in increased permeabilization, as reflected in NP-specific binding. Plates were washed with PBS-T, and 50 μl/well of a 1:10,000 dilution of HRP-goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) was added to plates and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Plates were washed with PBS-T, and 50 μl/well of the tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Vector Laboratories) was added for 10 to 15 minutes for color change; the reaction was stopped with the addition of 50 μl/well H2SO4. Absorbance was measured at optical density at 450 nm (OD450).

Virion ELISAs.

Nunc Maxisorp flat-bottom plates (ThermoFisher Scientific) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl/well of purified influenza virions at 0.5 μg/ml in bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). After being washed 3 times with PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), plates were blocked with 100 μl/well of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 2 hours. After another wash, 50 μl of the indicated MAb was added in 4-fold dilutions and incubated at 4°C overnight. The NP-specific MAb H16-L10 was used as a control, demonstrating virions remained intact for the assay. Addition of HRP-goat anti-mouse IgG, subsequent development, and reading were as described for the “Infected Cell ELISAs” protocol.

Plaque assay.

MDCK2 cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells per well and grown to confluence over 2 days. PR8 virus was incubated with 25 µg/ml of specified M2e-MAb or adamantane at 4°C for 30 minutes. Then, cells were infected with dilutions of antibody-virus mixtures between 10−3 and 10−8 in triplicate. Cells were lightly shaken every 10 to 15 minutes during an hour incubation at 37°C. After incubation, a 0.27% agar overlay containing 4 ng/ml of TPCK-trypsin was added to the wells. The assay was incubated at 37°C for 3 days. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 1 hour and then stained with a 0.4% crystal violet solution for 10 minutes. Plaques were then counted for the dilution, with clearly defined plaques (containing between 10 and 150 plaques) and PFUs calculated.

Protection studies.

Mice were given an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of the specified MAb at a specified dose 24 hours before virus challenge with 10× the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of the specified virus. H1N1 challenge virus was administered in 20 μl of PBS intranasally to mice anesthetized with isoflurane. The pH1N1 and H5N1 challenge viruses were administered in 30 μl of PBS intranasally to mice anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. The H7N9 virus was administered intranasally to mice anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol in tert-amyl alcohol (avertin; Aldrich Chemical Co.). The viral inoculum titer of each challenge with pH1N1, H7N9, and H5N1 was determined on MDCK-ATL cells to confirm dose. If specified, a subset of mice were humanely euthanized, and tissues collected to determine virus titer 3 days postinfection (dpi). All animals were monitored for body weight and humane endpoints for euthanization. Survival and weight loss were monitored for up to 21 dpi or until all animals recovered to at least 90% starting body weight.

Statistical analysis.

All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 7. For comparisons of antibody titers between groups at a single time point and plaque assays, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test was performed. Survival analysis utilized a Mantel-Cox log-rank test. Weight loss was analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test to compare weights between groups on individual days. Results for curve mean comparisons of days 0 to 14 postinfection by a 2-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s comparison are shown to the left of the heatmap. All statistics for a particular data set are indicated in the figure legends (****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). Line of best fit regression analysis was performed using either linear regression or nonlinear (agonist) versus normalized response regression. The line of best fit was determined by which regression had the highest R squared value (Table 3). Regressions with an R squared value below 0.4 were only seen in isotype control analysis and were not used.

TABLE 3.

| M2e-MAb | No. of studies (R2 value) for: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR8 | CA07 | VN1203 | Anhui1 | All isotype controls | |

| 391 | 3 (0.47) | 1 (0.99) | 1 (0.89) | 1 (1) | 4 (0.56) |

| 472 | 2 (0.95) | 1 (0.98) | 2 (0.82) | 1 (0.98) | 4 (<0.4)b |

| 522 | 4 (0.48) | 1 (1) | 2 (0.96) | 1 (0.999) | 6 (0.47) |

| 602 | 3 (0.63) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.98) | 1 (1) | 5 (<0.4)b |

| 770 | 3 (0.92) | 1 (0.94) | 2 (0.88) | 1 (0.99) | 4 (0.82) |

| 934 | 1 (0.96) | 1 (0.99) | 1 (0.999) | 3 (0.82) | |

| 1191 | 2 (0.41) | 1 (NA) | |||

Listed are the number of studies included in the analysis of each line of best fit and the R squared value for the selected line of best fit (linear or nonlinear) shown in the graph in Fig. 8. NA, neuraminidase.

For any data set with an R squared values less than 0.4 for both regressions, a line of best fit was not selected.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this work was supported by the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (R01AI130065; 2017 to 2021); The Albert and Margaret Alkek Foundation, Houston, Texas (2015); and NIAID under award number AI053831. This project was supported by the Protein and Monoclonal Antibody Production Shared Resource at Baylor College of Medicine with funding from NIH Cancer Center Support grant P30 CA125123.

L.B., S.M.T., and S.P. designed experiments. L.B., S.L.R., A.Y.S., S.K.J., C.A.J., T.K., and D.T.L. performed experiments. L.B., S.L.R., S.K.J., C.A.J., T.K., S.M.T., and S.P. analyzed data. L.B. wrote the manuscript. L.B., S.L.R., S.M.T., and S.P. edited the manuscript.

We thank Harvinder Singh Gill at Texas Tech University who provided the AuNP-M2e+sCpG vaccine used in these experiments. We thank and acknowledge the BCM Protein and Monoclonal Antibody Production Core for producing our hybridomas and monoclonal antibodies. We thank Suzanne Epstein (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD) for providing A/PR/8/1934 (H1N1) and A/FM/1/1947-MA (H1N1). We also thank Earl G. Brown (University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada) for approving the sharing of A/FM/1/1947-MA (H1N1). We thank Ted Ross (University of Georgia, Athens, GA) for providing A/CA/07/2009 (H1N1), and Richard Webby (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) for providing A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9) and A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1). Next, we thank Jon Yewdell (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for sharing the NP-specific hybridoma H16-L10. A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9) was provided via the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) was also provided by Richard Webby. Finally, we thank Bailee Kain, who assisted in weighing mice for some of the studies in the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sridhar S, Brokstad KA, Cox RJ. 2015. Influenza vaccination strategies: comparing inactivated and live attenuated influenza vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 3:373–389. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3020373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 2008. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Annu Rev Pathol 3:499–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2014. Continuing challenges in influenza. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1323:115–139. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Webby RG, Thomas PG. 2006. Influenza and the challenge for immunology. Nat Immunol 7:449–455. doi: 10.1038/ni1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton BS, Whittaker GR, Daniel S. 2012. Influenza virus-mediated membrane fusion: determinants of hemagglutinin fusogenic activity and experimental approaches for assessing virus fusion. Viruses 4:1144–1168. doi: 10.3390/v4071144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anonymous. 2018. FDA approves new drug to treat influenza. U.S. Food and Drug Adminstration, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anomymous. 2018. Influenza (flu) antiviral drugs and related information. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/information-drug-class/influenza-flu-antiviral-drugs-and-related-information.

- 8.Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, Gubareva L, Bresee JS, Uyeki TM, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 60:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takashita E, Morita H, Ogawa R, Nakamura K, Fujisaki S, Shirakura M, Kuwahara T, Kishida N, Watanabe S, Odagiri T. 2018. Susceptibility of influenza viruses to the novel Cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Front Microbiol 9:3026–3026. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soema PC, Kompier R, Amorij J-P, Kersten GFA. 2015. Current and next generation influenza vaccines: formulation and production strategies. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 94:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng L, Cho KJ, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2015. M2e-Based universal influenza A vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 3:105–136. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tao W, Ziemer KS, Gill HS. 2014. Gold nanoparticle-M2e conjugate coformulated with CpG induces protective immunity against influenza A virus. Nanomedicine (Lond) 9:237–251. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao W, Hurst BL, Shakya AK, Uddin MJ, Ingrole RS, Hernandez-Sanabria M, Arya RP, Bimler L, Paust S, Tarbet EB, Gill HS. 2017. Consensus M2e peptide conjugated to gold nanoparticles confers protection against H1N1, H3N2 and H5N1 influenza A viruses. Antiviral Res 141:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treanor JJ, Tierney EL, Zebedee SL, Lamb RA, Murphy BR. 1990. Passively transferred monoclonal antibody to the M2 protein inhibits influenza A virus replication in mice. J Virol 64:1375–1377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.64.3.1375-1377.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. 1988. Influenza A virus M2 protein: monoclonal antibody restriction of virus growth and detection of M2 in virions. J Virol 62:2762–2772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.62.8.2762-2772.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zharikova D, Mozdzanowska K, Feng J, Zhang M, Gerhard W. 2005. Influenza type A virus escape mutants emerge in vivo in the presence of antibodies to the ectodomain of matrix protein 2. J Virol 79:6644–6654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6644-6654.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. 1989. Growth restriction of influenza A virus by M2 protein antibody is genetically linked to the M1 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:1061–1065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grandea AG, III, Olsen OA, Cox TC, Renshaw M, Hammond PW, Chan-Hui P-Y, Mitcham JL, Cieplak W, Stewart SM, Grantham ML, Pekosz A, Kiso M, Shinya K, Hatta M, Kawaoka Y, Moyle M. 2010. Human antibodies reveal a protective epitope that is highly conserved among human and nonhuman influenza A viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:12658–12663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911806107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramos EL, Mitcham JL, Koller TD, Bonavia A, Usner DW, Balaratnam G, Fredlund P, Swiderek KM. 2015. Efficacy and safety of treatment with an anti-m2e monoclonal antibody in experimental human influenza. J Infect Dis 211:1038–1044. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouvier NM, Lowen AC. 2010. Animal models for influenza virus pathogenesis and transmission. Viruses 2:1530–1563. doi: 10.3390/v20801530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bimler L, Song AY, Le DT, Murphy Schafer A, Paust S. 2019. AuNP-M2e + sCpG vaccination of juvenile mice generates lifelong protective immunity to influenza A virus infection. Immun Ageing 16:23. doi: 10.1186/s12979-019-0162-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao W, Gill HS. 2015. M2e-immobilized gold nanoparticles as influenza A vaccine: role of soluble M2e and longevity of protection. Vaccine 33:2307–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho KJ, Schepens B, Moonens K, Deng L, Fiers W, Remaut H, Saelens X. 2016. Crystal structure of the conserved amino terminus of the extracellular domain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus gripped by an antibody. J Virol 90:611–615. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02105-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho KJ, Schepens B, Seok JH, Kim S, Roose K, Lee JH, Gallardo R, Van Hamme E, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Fiers W, Saelens X, Kim KH. 2015. Structure of the extracellular domain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus in complex with a protective monoclonal antibody. J Virol 89:3700–3711. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02576-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu TM, Freed DC, Horton MS, Fan J, Citron MP, Joyce JG, Garsky VM, Casimiro DR, Zhao Q, Shiver JW, Liang X. 2009. Characterizations of four monoclonal antibodies against M2 protein ectodomain of influenza A virus. Virology 385:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang R, Song A, Levin J, Dennis D, Zhang NJ, Yoshida H, Koriazova L, Madura L, Shapiro L, Matsumoto A, Yoshida H, Mikayama T, Kubo RT, Sarawar S, Cheroutre H, Kato S. 2008. Therapeutic potential of a fully human monoclonal antibody against influenza A virus M2 protein. Antiviral Res 80:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Bakkouri K, Descamps F, De Filette M, Smet A, Festjens E, Birkett A, Van Rooijen N, Verbeek S, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2011. Universal vaccine based on ectodomain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A: Fc receptors and alveolar macrophages mediate protection. J Immunol 186:1022–1031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolpe A, Schepens B, Ye L, Staeheli P, Saelens X. 2018. Passively transferred M2e-specific monoclonal antibody reduces influenza A virus transmission in mice. Antiviral Res 158:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T, Bachmann MF. 2004. Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J Immunol 172:5598–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamb RA, Zebedee SL, Richardson CD. 1985. Influenza virus M2 protein is an integral membrane protein expressed on the infected-cell surface. Cell 40:627–633. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei G, Meng W, Guo H, Pan W, Liu J, Peng T, Chen L, Chen C-Y. 2011. Potent neutralization of influenza A virus by a single-domain antibody blocking M2 ion channel protein. PLoS One 6:e28309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Den Hoecke S, Ehrhardt K, Kolpe A, El Bakkouri K, Deng L, Grootaert H, Schoonooghe S, Smet A, Bentahir M, Roose K, Schotsaert M, Schepens B, Callewaert N, Nimmerjahn F, Staeheli P, Hengel H, Saelens X. 2017. Hierarchical and redundant roles of activating FcγRs in protection against influenza disease by M2e-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies. J Virol 91:e02500-16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02500-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. 2014. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20:143–151. doi: 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. 2005. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science 310:1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nimmerjahn F, Gordan S, Lux A. 2015. FcgammaR dependent mechanisms of cytotoxic, agonistic, and neutralizing antibody activities. Trends Immunol 36:325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruhns P, Jönsson F. 2015. Mouse and human FcR effector functions. Immunol Rev 268:25–51. doi: 10.1111/imr.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavin AL, Barnes N, Dijstelbloem HM, Hogarth PM. 1998. Cutting edge: identification of the mouse IgG3 receptor: implications for antibody effector function at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol 160:20– 23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saylor CA, Dadachova E, Casadevall A. 2010. Murine IgG1 and IgG3 isotype switch variants promote phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans through different receptors. J Immunol 184:336–343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawk CS, Coelho C, Oliveira DSLd, Paredes V, Albuquerque P, Bocca AL, Correa dos Santos A, Rusakova V, Holemon H, Silva-Pereira I, Felipe MSS, Yagita H, Nicola AM, Casadevall A. 2019. Integrin β1 promotes the interaction of murine IgG3 with effector cells. J Immunol 202:2782–2794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pielak RM, Schnell JR, Chou JJ. 2009. Mechanism of drug inhibition and drug resistance of influenza A M2 channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:7379–7384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902548106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayden FG, de Jong MD. 2011. Emerging influenza antiviral resistance threats. J Infect Dis 203:6–10. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia V, Aris-Brosou S. 2014. Comparative dynamics and distribution of influenza drug resistance acquisition to protein m2 and neuraminidase inhibitors. Mol Biol Evol 31:355–363. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan S, Boltz DA, Seiler P, Li J, Bragstad K, Nielsen LP, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2010. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza virus possesses lower transmissibility and fitness in ferrets. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001022. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong DDY, Choy K-T, Chan RWY, Sia SF, Chiu H-P, Cheung PPH, Chan MCW, Peiris JSM, Yen H-L. 2012. Comparable fitness and transmissibility between oseltamivir-resistant pandemic 2009 and seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses with the H275Y neuraminidase mutation. J Virol 86:10558–10570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00985-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hussain M, Galvin HD, Haw TY, Nutsford AN, Husain M. 2017. Drug resistance in influenza A virus: the epidemiology and management. Infect Drug Resist 10:121–134. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S105473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N, Lee N, De Jong MD, Hurt AC, Ishida T, Sekino H, Yamada K, Portsmouth S, Kawaguchi K, Shishido T, Arai M, Tsuchiya K, Uehara T, Watanabe A. 2018. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Engl J Med 379:913–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huber VC, Lynch JM, Bucher DJ, Le J, Metzger DW. 2001. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis makes a significant contribution to clearance of influenza virus infections. J Immunol 166:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huber VC, McKeon RM, Brackin MN, Miller LA, Keating R, Brown SA, Makarova N, Perez DR, Macdonald GH, McCullers JA. 2006. Distinct contributions of vaccine-induced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a antibodies to protective immunity against influenza. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13:981–990. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00156-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas PG, Keating R, Hulse-Post DJ, Doherty PC. 2006. Cell-mediated protection in influenza infection. Emerg Infect Dis 12:48–54. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.051237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simhadri VR, Dimitrova M, Mariano JL, Zenarruzabeitia O, Zhong W, Ozawa T, Muraguchi A, Kishi H, Eichelberger MC, Borrego F. 2015. A human anti-M2 antibody mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and cytokine secretion by resting and cytokine-preactivated natural killer (NK) cells. PLoS One 10:e0124677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughey PG, Roberts PC, Holsinger LJ, Zebedee SL, Lamb RA, Compans RW. 1995. Effects of antibody to the influenza A virus M2 protein on M2 surface expression and virus assembly. Virology 212:411–421. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reale MA, Bona CA, Schulman JL. 1985. Isotype profiles of anti-influenza antibodies in mice bearing the xid defect. J Virol 53:425–429. doi: 10.1128/JVI.53.2.425-429.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hocart M, Mackenzie J, Stewart G. 1988. The IgG subclass responses induced by wild-type, cold-adapted and purified haemagglutinin from influenza virus A/Queensland/6/72 in CBA/CaH mice. J Gen Virol 69:1873–1882. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-8-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oh H-LJ, Åkerström S, Shen S, Bereczky S, Karlberg H, Klingström J, Lal SK, Mirazimi A, Tan Y-J. 2010. An antibody against a novel and conserved epitope in the hemagglutinin 1 subunit neutralizes numerous H5N1 influenza viruses. J Virol 84:8275–8286. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02593-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wohlbold TJ, Chromikova V, Tan GS, Meade P, Amanat F, Comella P, Hirsh A, Krammer F. 2016. Hemagglutinin stalk- and neuraminidase-specific monoclonal antibodies protect against lethal H10N8 influenza virus infection in mice. J Virol 90:851–861. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02275-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng JQ, Mozdzanowska K, Gerhard W. 2002. Complement component C1q enhances the biological activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin-specific antibodies depending on their fine antigen specificity and heavy-chain isotype. J Virol 76:1369–1378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.3.1369-1378.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiong F-F, Liu X-Y, Gao F-X, Luo J, Duan P, Tan W-S, Chen Z. 2020. Protective efficacy of anti-neuraminidase monoclonal antibodies against H7N9 influenza virus infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:78–87. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1708214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Impagliazzo A, Milder F, Kuipers H, Wagner MV, Zhu X, Hoffman RM, van Meersbergen R, Huizingh J, Wanningen P, Verspuij J, de Man M, Ding Z, Apetri A, Kukrer B, Sneekes-Vriese E, Tomkiewicz D, Laursen NS, Lee PS, Zakrzewska A, Dekking L, Tolboom J, Tettero L, van Meerten S, Yu W, Koudstaal W, Goudsmit J, Ward AB, Meijberg W, Wilson IA, Radosevic K. 2015. A stable trimeric influenza hemagglutinin stem as a broadly protective immunogen. Science 349:1301–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prachanronarong KL, Canale AS, Liu P, Somasundaran M, Hou S, Poh YP, Han T, Zhu Q, Renzette N, Zeldovich KB, Kowalik TF, Kurt-Yilmaz N, Jensen JD, Bolon DNA, Marasco WA, Finberg RW, Schiffer CA, Wang JP. 2018. Mutations in influenza A virus neuraminidase and hemagglutinin confer resistance against a broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stem antibody. J Virol 93:e01639-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01639-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrews SF, Huang Y, Kaur K, Popova LI, Ho IY, Pauli NT, Henry Dunand CJ, Taylor WM, Lim S, Huang M, Qu X, Lee J-H, Salgado-Ferrer M, Krammer F, Palese P, Wrammert J, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. 2015. Immune history profoundly affects broadly protective B cell responses to influenza. Sci Transl Med 7:316ra192. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krammer F, Fouchier RAM, Eichelberger MC, Webby RJ, Shaw-Saliba K, Wan H, Wilson PC, Compans RW, Skountzou I, Monto AS. 2018. NAction! How can neuraminidase-based immunity contribute to better influenza virus vaccines? mBio 9:e02332-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02332-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He W, Chen C-J, Mullarkey CE, Hamilton JR, Wong CK, Leon PE, Uccellini MB, Chromikova V, Henry C, Hoffman KW, Lim JK, Wilson PC, Miller MS, Krammer F, Palese P, Tan GS. 2017. Alveolar macrophages are critical for broadly-reactive antibody-mediated protection against influenza A virus in mice. Nat Commun 8:846. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00928-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terajima M, Cruz J, Co MDT, Lee J-H, Kaur K, Wrammert J, Wilson PC, Ennis FA. 2011. Complement-dependent lysis of influenza a virus-infected cells by broadly cross-reactive human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 85:13463–13467. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05193-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kosik I, Angeletti D, Gibbs JS, Angel M, Takeda K, Kosikova M, Nair V, Hickman HD, Xie H, Brooke CB, Yewdell JW. 2019. Neuraminidase inhibition contributes to influenza A virus neutralization by anti-hemagglutinin stem antibodies. J Exp Med 216:304–316. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Furuse Y, Suzuki A, Kamigaki T, Oshitani H. 2009. Evolution of the M gene of the influenza A virus in different host species: large-scale sequence analysis. Virol J 6:67. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hierholzer JC, Killington RA. 1996. Virus isolation and quantitation, p 25–46. In Mahy BWJ, Kangro HO (ed), Virology methods manual. Academic Press, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gabbard J, Velappan N, Di Niro R, Schmidt J, Jones CA, Tompkins SM, Bradbury AR. 2009. A humanized anti-M2 scFv shows protective in vitro activity against influenza. Protein Eng Des Sel 22:189–198. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzn070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]