Chlamydia trachomatis is a strict intracellular bacterium that causes sexually transmitted infections and eye infections that can lead to lifelong sequelae. Treatment options are limited to broad-spectrum antibiotics that disturb the commensal flora and contribute to selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

KEYWORDS: Chlamydia trachomatis, antibacterial agents, intracellular bacteria, mode of action, virulence inhibitors

ABSTRACT

Chlamydia trachomatis is a strict intracellular bacterium that causes sexually transmitted infections and eye infections that can lead to lifelong sequelae. Treatment options are limited to broad-spectrum antibiotics that disturb the commensal flora and contribute to selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Hence, development of novel drugs that specifically target C. trachomatis would be beneficial. 2-Pyridone amides are potent and specific inhibitors of Chlamydia infectivity. The first-generation compound KSK120 inhibits the developmental cycle of Chlamydia, resulting in reduced infectivity of progeny bacteria. Here, we show that the improved, highly potent second-generation 2-pyridone amide KSK213 allowed normal growth and development of C. trachomatis, and the effect was only observable upon reinfection of new cells. Progeny elementary bodies (EBs) produced in the presence of KSK213 were unable to activate transcription of essential genes in early development and did not differentiate into the replicative form, the reticulate body (RB). The effect was specific to C. trachomatis since KSK213 was inactive in the closely related animal pathogen Chlamydia muridarum and in Chlamydia caviae. The molecular target of KSK213 may thus be different in C. trachomatis or nonessential in C. muridarum and C. caviae. Resistance to KSK213 was mediated by a combination of amino acid substitutions in both DEAD/DEAH RNA helicase and RNase III, which may indicate inhibition of the transcriptional machinery as the mode of action. 2-Pyridone amides provide a novel antibacterial strategy and starting points for development of highly specific drugs for C. trachomatis infections.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis is the causative agent of sexually transmitted infection and of trachoma, an eye infection that can lead to blindness. Annually, over 130 million sexually transmitted infections are caused by C. trachomatis (1, 2). Symptoms include cervicitis in women and urethritis in both men and women (3). While most infections cause mild symptoms or are asymptomatic, infections left untreated can lead to reactive arthritis (4), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), or infertility in women (5).

Chlamydia is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterium with a unique developmental cycle. It alternates between two major forms as follows: the replicative form, called reticulate bodies (RBs), and the infective form, called elementary bodies (EBs) (6). Infection begins when the EBs attach and internalize into the host cell. EBs invaginate in the host cell in a vacuole-like niche termed an inclusion, where the EBs transition into intermediate bodies (IBs) and later differentiate into RBs. RBs are metabolically active and replicate within the inclusions until they eventually redifferentiate into EBs. From the time C. trachomatis first enters the cells, it takes about 48 h before the newly formed EBs exit the host cells by lysis or by secretion of the whole inclusion (extrusion) and EBs are disseminated to infect surrounding cells (7).

Regulation of gene expression in Chlamydia corresponds to its unique life cycle in the host cell and is divided among three time-dependent clusters of genes as follows: early genes, mid-cycle genes, and late genes (8). Immediate early genes are expressed directly after attachment and internalization of EBs (9). When the DNA decondense and by the time EBs differentiate into RBs, a second class of early genes is transcribed (10). Mid-cycle genes are the most abundant, and their expression occurs when RBs start replicating and continues throughout the developmental cycle. Late genes are transcribed at the end of the developmental cycle when RBs redifferentiate into EBs (8).

C. trachomatis infections are routinely treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, most commonly azithromycin or doxycycline (11), which increase the risk of emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the microbiome (12). Treatment of trachoma with azithromycin can induce resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae (13), and azithromycin resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium is a consequence of the single-dose azithromycin regimen for sexually transmitted C. trachomatis (14, 15). Point-of-care testing and home testing for sexually transmitted infections prior to doctor visits are increasingly available and reduce the need for broad-spectrum antibiotics. Compounds with selective effects against C. trachomatis are therefore of great interest to reduce selective pressure on emergence of antibiotic resistance in commensal and pathogenic bacteria.

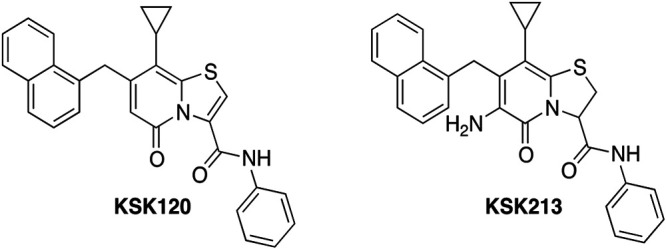

We have developed 2-pyridone amides that effectively inhibit Chlamydia infectivity (16–19) without disturbing growth of representative commensal microorganisms (16, 18). To evaluate the potency of 2-pyridone amides, we use a reinfection assay where we harvest progeny from an infection with compound-treated C. trachomatis and then infect new untreated cells and measure the number of Chlamydia inclusions formed (16, 18, 19). We have previously shown that the 2-pyridone amide KSK120 (Fig. 1) disturbs development of Chlamydia inclusions during treatment, leading to fewer progeny bacteria and lack of glycogen accumulation in the Chlamydia inclusion (17). Amino acid substitutions in the C. trachomatis glucose 6-phosphate (G6-P) transporter UhpC mediates resistance to KSK120, suggesting a direct effect on glucose metabolism (17). KSK120 was further modified using structure-activity relationships (SAR), and we developed more potent 2-pyridone amides with reduced toxicity to human cells (16, 18) as well as an orally bioavailable compound (19). In this study, we explored one of the most potent 2-pyridone amides, KSK213 (21A in reference 16) (Fig. 1), and investigated its mode of action.

FIG 1.

Chemical structures of KSK120 and KSK213.

(Parts of this study were included in a Ph.D. dissertation by Carlos Núñez-Otero at Umeå University.)

RESULTS

KSK213 does not alter the developmental cycle or growth of C. trachomatis.

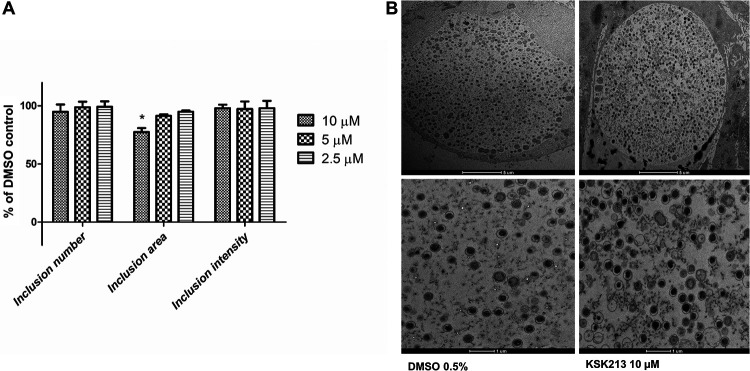

We used immunostaining and automated microscopy to investigate how KSK213 affected C. trachomatis inclusions in HeLa cells. KSK213 reduced neither the number of inclusions nor their immunostaining intensity at 10 μM, 5 μM, and 2.5 μM (Fig. 2A). The inclusion area was not affected at 5 μM and 2.5 μM, concentrations which are well above the 50% effective concentration (EC50) (59 nM) (16) but was reduced at the highest concentration of 10 μM. The results suggested that inclusion development and bacterial replication were not affected by KSK213 except at very high concentrations.

FIG 2.

C. trachomatis inclusions grow with normal morphology and numbers in the presence of KSK213. (A) HeLa cells infected with C. trachomatis L2 were treated with 10 μM, 5 μM, or 2.5 μM KSK213 or just 0.1% DMSO for 45 hpi prior to fixation. The number, area, and immunostaining intensity of the Chlamydia inclusions were quantified by automated microscopy and compared to DMSO-treated controls. Bars show means, and error bars show standard deviation from three experiments. Statistical significance (*) was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis (P < 0.05) and Dunn’s posttest (P < 0.05). (B) Representative transmission electron micrographs of Chlamydia inclusions in HeLa cells treated with 10 μM KSK213 (right) or 0.5% DMSO (left) (scale bar 5 μm, top) and a closeup of the bacteria inside the inclusion (scale bar 1 μm, bottom).

As KSK213 did not visibly reduce bacterial density of the Chlamydia inclusions, we further verified this by quantifying the number of Chlamydia genomes by quantitative PCR (qPCR). C. trachomatis-infected HeLa cells were treated with KSK213 at 10 μM and 1 μM for 48 h with 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 1 μg/ml doxycycline as controls. Genomic DNA extracted from purified EBs was used as a DNA standard for semiquantification of genome copies. The number of genome copies was similar in samples treated with KSK213 at 1 μM and 10 μM compared to that of DMSO while the doxycycline control had significantly lower numbers (Table 1). The results confirmed that KSK213 did not reduce C. trachomatis replication.

TABLE 1.

Quantitative PCR of C. trachomatis L2 treated with DMSO, KSK213, or doxycycline throughout the developmental cycle

| Sample (concentration) | Cq mean | Cq SD | Genome copies mean | Genome copies SD | R2 | Slope | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO (0.5%) | 17.474 | 0.157 | 1.0 × 105 | 1.0 × 104 | 0.997 | −3.826 | 82.542 |

| KSK213 (1 μM) | 18.036 | 0.305 | 0.74 × 105 | 1.3 × 104 | 0.997 | −3.826 | 82.542 |

| KSK213 (10 μM) | 17.896 | 0.211 | 0.8 × 105 | 1.0 × 104 | 0.997 | −3.826 | 82.542 |

| Doxycycline (1 μg/ml) | 29.270a | 0.304 | 0.9 × 102 | 2.0 × 101 | 0.997 | −3.826 | 82.542 |

Statistical significance was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc test (P < 0.05).

To determine if KSK213 treatment affects C. trachomatis differentiation and development, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM). At 48 hours postinfection (hpi), all developmental forms of Chlamydia were present, predominantly EBs, and there was no visible difference in distribution or morphology of bacteria in infections treated with 10 μM KSK213 compared to that of the DMSO-treated control (Fig. 2B). This shows that KSK213 did not block differentiation into the infectious EB form.

Since the first-generation 2-pyridone amide KSK120 affects glycogen accumulation in the Chlamydia inclusion, we investigated whether this was the case also for KSK213. C. trachomatis-infected HeLa cells were treated with 5 μM KSK213 or KSK120 and were stained by iodine glycogen staining. KSK213-treated infections had the same dark glycogen staining as those of the DMSO control, showing that KSK213 did not affect glycogen accumulation and indicating another mode of action compared to KSK120 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Progeny EBs from KSK213-treated infections enter new cells but do not differentiate into RBs.

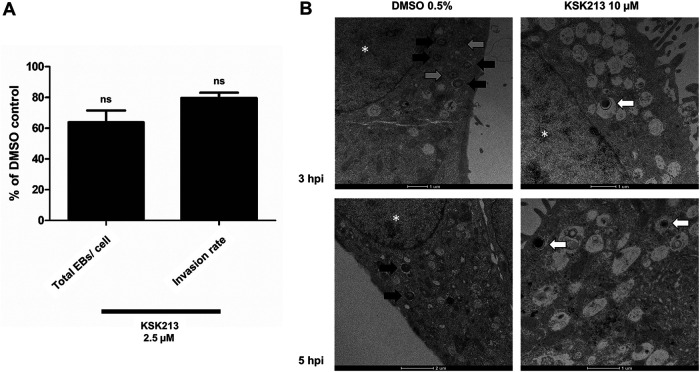

As KSK213 did not affect replication and differentiation of C. trachomatis, we hypothesized that the progeny EBs were unable to invade new cells. Using differential immunostaining of extracellular and intracellular bacteria and confocal microscopy, we quantified the proportion of extracellular and intracellular bacteria upon reinfection of new cells. Attachment and internalization of progeny Chlamydia into the new cells were, however, not significantly reduced after KSK213 treatment (Fig. 3A). We then used TEM to visualize early reinfection and confirmed that Chlamydia progeny grown with KSK213 were able to attach to and invade new cells (Fig. 3B). At 3 hpi and 5 hpi, EBs from DMSO-treated infections had differentiated into RBs, while only the EB form was detected from KSK213-treated infections. The results show that KSK213 treatment did not stop the progeny EBs from entering new cells, but differentiation into RBs failed (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

C. trachomatis L2 EBs produced in the presence of KSK213 enter new HeLa cells but fail to differentiate into RBs in the first 5 h after reinfection. (A) Differential staining of attached and internalized EBs upon reinfection of cells after 0.1% DMSO or 2.5 μM KSK213 treatment. The bars show, in comparison to the DMSO control, the total number of attached and internalized EBs per cell and the fraction of internalized EBs out of the total number of EBs. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann-Whitney U test; ns, no statistical significance. (B) Representative TEM pictures of individual bacteria reinfecting cells after treatment with 0.5% DMSO (left) or 10 μM KSK213 (right) at 3 hpi (top) and 5 hpi (bottom). Gray arrows point to intermediate bodies (IBs), black arrows point to reticulate bodies (RBs), and white arrows point to elementary bodies (EBs). *, cell nuclei.

Essential early gene transcription is not activated in KSK213-treated EBs upon reinfection.

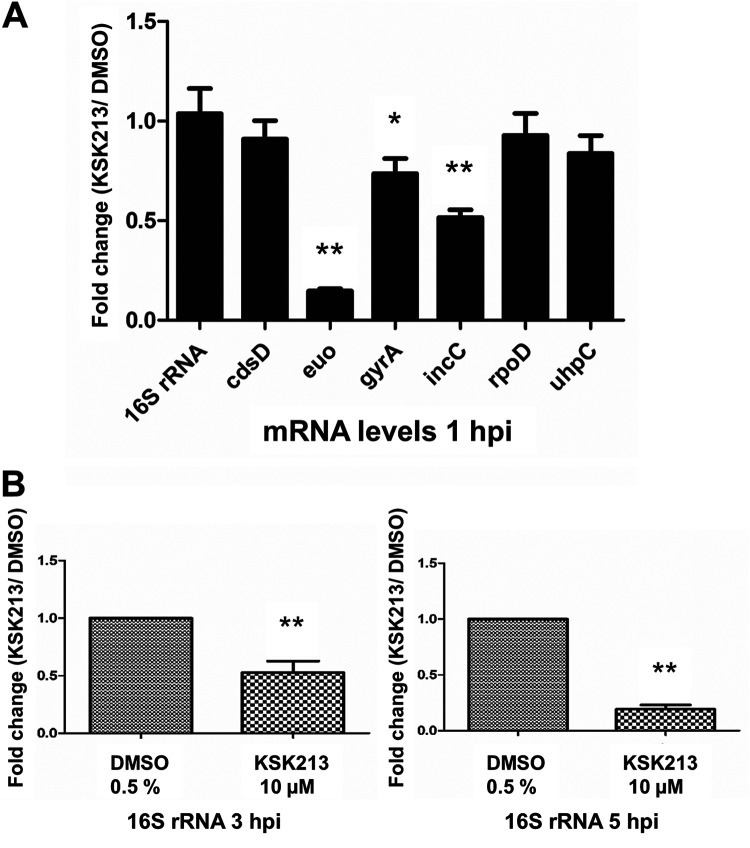

After observing that EBs produced during KSK213 treatment were able to enter cells but not differentiate into RBs, we evaluated transcriptional activity upon reinfection using semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). HeLa cells were infected with EBs produced during KSK213 treatment, and the expression of seven genes was measured upon reinfection in new cells at three different time points. Six genes with differential expression during the developmental cycle were selected as follows: euo, gyrA, and incC expressed in early development, rpoD constitutively expressed, and cdsD and uhpC expressed in late development. 16S rRNA was used for normalization. Levels of the early genes euo, gyrA, and incC were significantly lower at 1 hpi (Fig. 4A) after KSK213 treatment compared to DMSO treatment. The constitutively expressed rpoD levels did not differ significantly between KSK213 and DMSO at 1 hpi, and the late genes cdsD and uhpC mRNAs were detected at very low and similar levels (Fig. 4A). The levels of 16S rRNA were significantly lower in KSK213-treated samples at 3 hpi and 5 hpi normalized to 1 hpi and compared to the DMSO control (Fig. 4B). This confirmed that transcription was not activated normally and that 16S rRNA was not suitable for normalization at these later time points. The results show that EBs produced in the presence of KSK213 failed to activate early transcription upon reinfection.

FIG 4.

KSK213 treatment reduces early gene expression in C. trachomatis L2 upon reinfection of HeLa cells. (A) Expression of seven genes at 1 hpi normalized to 16S rRNA levels. Bars show the fold change after 10 μM KSK213 treatment compared to the 0.5% DMSO control. (B) 16S rRNA levels at 3 and 5 hpi normalized to the levels at 1 hpi. Bars show the fold change after 10 μM KSK213 treatment compared to the 0.5% DMSO control. Statistical analysis comparing KSK213 to DMSO treatment was assessed by Mann-Whitney U test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Mutations in helicase and RNase III mediate resistance to KSK213.

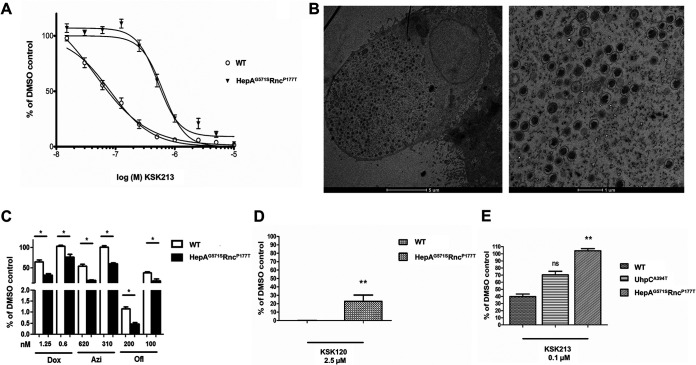

To investigate the mode of action of KSK213, we selected for resistance to the compound by serial passaging C. trachomatis serovar L2 15 times in the presence of increasing concentrations of KSK213 (from 0.5 μM to 0.7 μM). The resistant strain was about 10-fold more tolerant of KSK213, with an EC50 of 500 nM, than the wild-type (WT) strain, which had an EC50 of 46 nM in this experiment (Fig. 5A). Whole-genome sequencing of the cloned KSK213-resistant isolates revealed a high frequency (97 to 100%) of two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), G1711A in the DEAD/DEAH RNA helicase gene CTL0077 and C529A in the RNase III gene CTL0549, respectively, in three out of four clonal isolates. We chose one of the isolates for further investigation. The mutation in the RNase III gene was a C to A nucleotide change at position 529, which translates to a proline to threonine substitution at position 177. In the helicase gene, there was a G to A change at position 1711, causing a glycine to serine substitution at position 571. The strain was named C. trachomatis HepAG571SRncP177T. The development of RBs and EBs in HepAG571SRncP177T was normal, as confirmed by TEM (Fig. 5B). To determine if these mutations could mediate a nonspecific resistance to commonly used antibiotics, we tested the growth inhibitory effect of doxycycline, azithromycin, and ofloxacin in HepAG571SRncP177T and in the WT by quantifying Chlamydia inclusion-forming units (IFUs) 48 hpi. The mutant was significantly more susceptible to all tested antibiotics (Fig. 5C), which ruled out unspecific resistance mechanisms to antimicrobial compounds. We also found that HepAG571SRncP177T was cross-resistant to KSK120, as it was significantly less susceptible to KSK120 than to the wild type (Fig. 5D). Finally, we evaluated whether the previously published KSK120-resistant strain C. trachomatis UhpCA394T (17), was cross-resistant to KSK213. UhpCA394T was not significantly resistant to KSK213, although more viable progeny were produced at 2.5 μM compared to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 5E). The finding that resistance to both KSK213 and KSK120 was mediated by mutations in DEAD/DEAH RNA helicase and RNase III may suggest that the compounds target gene expression.

FIG 5.

Amino acid substitutions in DEAD/DEAH box helicase (HepAG571S) and RNase III (RncP177T) mediate resistance to KSK213 and cross-resistance to KSK120. (A) Dose-dependent inhibition by KSK213 in the reinfection assay with the C. trachomatis L2 strain HepAG571SRncP177T and the wild type (WT). (B) Representative transmission electron micrographs of HepAG571SRncP177T at 48 hpi. An inclusion on the left and a closeup of bacteria within the inclusion on the right. (C) Growth inhibition by doxycycline (Dox), azithromycin (Azi), and ofloxacin (Ofl) in HepAG571SRncP177T and WT. Bars show average number of inclusions as percent of the 0.5% DMSO control. (D) Inhibition of Chlamydia infectivity by 2.5 μM KSK120 in the reinfection assay with the C. trachomatis L2 strains HepAG571SRncP177T and WT. (E) Inhibition of Chlamydia infectivity by 0.1 μM KSK213 in the reinfection assay with the C. trachomatis L2 strains WT, UhpCA394T, and HepAG571SRncP177T. Bars in panels D and E show average number of inclusions upon reinfection after KSK213 treatment in percent of the 0.5% DMSO control. Error bars in all panels show standard deviation. Statistical significance was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s posttest or Mann-Whitney U test in panels C, D, and E. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, no statistical significance.

KSK213 has similar activity in different human cell lines.

To evaluate if the effect of KSK213 was dependent on the host cell type, we tested the effect of KSK213 on C. trachomatis grown in 10 different human cancer cell lines. Eight of the cell lines were obtained from the NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen library (20), a well-established resource in cancer and virology research. The cell lines were isolated from different types of tumors (colon, lung, central nervous system [CNS], renal, melanoma, ovarian, breast, and prostate). Other cell lines used were A2EN (polarized endocervical cells) and HT-29 (colorectal cells), both good models of Chlamydia infection in humans, as the endocervix and rectum are infection sites for C. trachomatis. The potency of KSK213 against C. trachomatis was similar in all cell lines tested (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), which may indicate that host cell factors are not responsible for the effect of KSK213.

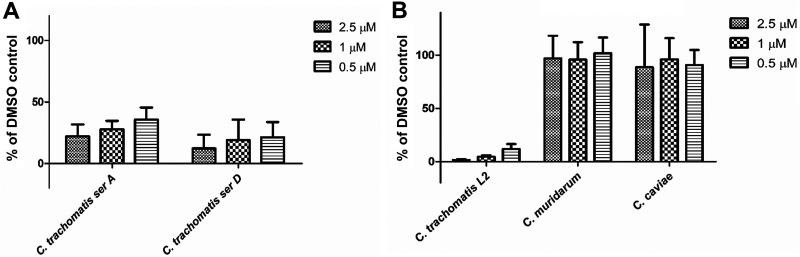

KSK213 is selective for C. trachomatis.

KSK213 has a potent inhibitory effect on the sexually transmitted C. trachomatis serovars LGV and D, while it is inactive against gut bacteria and is nontoxic in human cells (16). To determine if KSK213 also inhibits other Chlamydia serovars and species, we performed the reinfection assay on a trachoma ocular strain, C. trachomatis serovar A, and on two Chlamydia species pathogenic to animals. C. trachomatis serovar A was as sensitive to KSK213 as the genital serovar D (Fig. 6A). To our surprise, 2.5 μM KSK213 had no effect on the mouse pathogen Chlamydia muridarum or the guinea pig pathogen Chlamydia caviae grown in HeLa cells (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). As the growth of these Chlamydia strains was variable in HeLa cells, we also repeated the experiments in Vero cells and confirmed that KSK213 did not affect C. muridarum and C. caviae while C. trachomatis infectivity was inhibited by over 90% also in Vero cells (Fig. 6B). The lack of effect in these other Chlamydia species indicates a selective activity against C. trachomatis.

FIG 6.

KSK213 reduces the infectivity of different C. trachomatis serovars but is inactive in C. muridarum and C. caviae. HeLa cells infected with C. trachomatis serovar A or D (A) or Vero cells infected with C. trachomatis L2, C. muridarum, or C. caviae (B) were incubated for 46 to 48 h (36 h for C. muridarum) prior to cell lysis and reinfection of fresh cells. Inclusion numbers upon reinfection were quantified 44 hpi and presented as a percent of a DMSO-treated control. Bars show mean, and error bars show standard deviation of three experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we discovered that the highly potent second-generation 2-pyridone amide KSK213 affects Chlamydia infection in different ways than the first-generation compound KSK120. Chlamydia inclusions treated with KSK213 had unaltered morphology, bacterial numbers, and glycogen deposits. Further, mutations in the C. trachomatis glucose importer uhpC that mediate resistance to KSK120 (17) did not mediate resistance to KSK213, suggesting that glycogen metabolism is not the target for KSK213. KSK213 and KSK120 are highly similar 2-pyridone amide compounds, but a major difference is the C-2/C-3 double bond of KSK120. This increases the planarity compared to that of KSK213 and makes KSK120 less polar and more prone to aggregation, which can lead to nonspecific binding and off-target effects (21). Off-target effects may be apparent only at high concentrations, and we therefore used micromolar concentrations of KSK213 in this study, although KSK213 is effective at low nanomolar concentrations. At the highest concentration, 10 μM, KSK213 reduced inclusion size, but otherwise there were no visible changes to Chlamydia development even at high concentrations, suggesting a specific effect of KSK213 on EB infectivity. This aligns with the fact that KSK213 is 10 times more potent and less toxic to host cells than KSK120 (16).

The progeny EBs from KSK213-treated cells were able to attach to and enter new cells, but transition into RBs was not seen at 5 hpi, a development that generally occurs by 2 hpi (8, 10, 22). The differentiation from EB to RB requires early protein expression (23), and we found that gene expression in early reinfection was reduced after KSK213 treatment. euo and other early transcribed genes had significantly lower mRNA levels after KSK213 treatment. The gene euo encodes for a master transcriptional regulator that is expressed even before the genomic DNA is decondensed. It is not known how it is regulated, but it is crucial for Chlamydia development as a repressor of late genes (9). Since KSK213 treatment allows growth and development, regulation of Euo cannot be the direct target, and we hypothesize that KSK213 disturbs EB maturation, resulting in dysfunctional early gene regulation and reduced viability of the produced EBs. Early invasion and avoidance of lysosomal fusion is dependent on proteins preloaded in EBs (24), and inactivated EBs can invade host cells and avoid lysosomal degradation up to 30 hpi (23, 26, 27). The content of proteins needed for host cell invasion may not have been affected by KSK213 treatment, but these EBs were unable to start transcription of early genes after invasion of the host cell and, therefore, remained undifferentiated.

Chlamydia development depends on an intricate interplay with the host cell, and several small compounds targeting different host cell functions have been shown to reduce Chlamydia infectivity, although not as effectively as 2-pyridone amides (28, 29). We used a library of human tumor cell lines with defined gene expression and properties to investigate whether the effect of KSK213 was enhanced or reduced depending on the host cell. KSK213 was equally potent in all cell types.

The similar effect in different cell types indicated that KSK213 directly targets C. trachomatis. We used our established method to select for compound-resistant C. trachomatis followed by whole-genome sequencing of the mutant isolates (17, 30, 31). The mutant HepAG571SRncP177T presented a 10-fold resistance to KSK213 and had amino acid substitutions in DEAD/DEAH RNA helicase and RNase III, proteins that are involved in gene transcription and RNA processing. The HepAG571S mutation was located in a structural region of the protein, and the mutation on RncP177T occurred within the double-stranded RNA binding motif (DRBM), which is involved in recognition and binding to double-stranded mRNAs. The mutations may affect recognition and processing of mRNA, and their individual contribution to the resistance phenotype demands separation of two mutations. Backcrossing of the mutant to the parental strain is a way to separate mutations but demands an independent selection marker. We did not succeed in selecting for rifampin or streptomycin resistance in HepAG571SRncP177T, likely due to the strain’s enhanced sensitivity to antibiotics. Interestingly, HepAG571SRncP177T was cross-resistant to KSK120. Multiple mutations that are not directly involved in glucose metabolism also mediate resistance to KSK120. Individual amino acid substitutions in either the gene repair enzyme RecC or the elongation factor-P (EF-P) conferred resistance to KSK120, and a combination of substitutions in RNA polymerase RpoC and in UhpC lead to a higher degree of resistance to KSK120 than UhpCA394T substitutions alone (17). Another class of 2-pyridone compounds inhibits virulence in Listeria monocytogenes by binding to the master transcription regulator of virulence, PrfA (32). We hypothesize that chemical substitutions in the 2-pyridone amides result in species-specific inhibitors of Chlamydia gene regulation. Thus, KSK213 and KSK120 may target gene regulation differently, but the cross-resistance may occur by a more general resistance mechanism compensating for the gene dysregulation. Reduced RNase III function leads to an increased level of most transcripts (33), which is one way to overcome reduced expression. A malfunctioning RNA helicase may have a similar effect by reducing the accessibility of RNases to mRNA strands.

The various Chlamydia species and serovars are adapted to their animal hosts and cause a variety of clinical manifestations (34, 35). We investigated whether KSK213 is effective in different Chlamydia species and observed that C. muridarum and C. caviae were not susceptible to KSK213. This was particularly interesting in the case of C. muridarum, a mouse pneumonitis pathogen that is closely related to C. trachomatis and shares 99% of its open reading frames (36–38). One well-studied difference between C. muridarum and the genital serovars of C. trachomatis is tryptophan metabolism. Genital serovars of C. trachomatis can synthesize tryptophan from indole while C. muridarum and ocular strains of C. trachomatis, such as C. trachomatis serovar A (37, 38), lack this function. Since C. trachomatis serovar A turned out to be equally susceptible to KSK213 as the genital serovars L2 and D, tryptophan metabolism is unlikely to be the target of KSK213. Lack of tryptophan also induces a particular persistent growth form (39) that was not observed after KSK213 treatment. 2-Pyridone amides are known to be selective for Chlamydia (16, 18), and our data suggest that KSK213 may target functions specific to C. trachomatis or bind to a molecular target that is not essential in other Chlamydia species.

In conclusion, our data show that KSK213 treatment results in C. trachomatis progeny that fail to activate transcription and differentiate into RBs in early reinfection. Mutations in genes important for mRNA stability mediate resistance, indicating that 2-pyridone amides target gene regulation. Our current hypothesis is that KSK213 disturbs gene regulation during EB maturation resulting in defect EBs, and future efforts will focus on discovering the molecular target of 2-pyridone amides. Compounds interfering with transcription of bacterial virulence is a novel strategy for development of highly selective antibacterial agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and Chlamydia propagation.

HeLa 229 (CCL-2.1; ATCC), Vero (CCL-81; ATCC), HT29 (HTB-38; ATCC), and A2EN (40) were cultured at 37°C (5% CO2) in growth medium (RPMI with 25 mM HEPES and 2 mM l-glutamine [HyClone] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS] [Sigma]). Cell lines NCI-H23, HCC-2998, SF-268, UACC-257, OVCAR-5, SN12C, DU-145, and HS 578T (NCI-60 Human Tumor Cell Lines Screen [20]) were cultured under the same conditions.

Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu (VR-902B; ATCC), Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu UhpCA394T (17), Chlamydia trachomatis serovar A (VR-571B; ATCC), Chlamydia trachomatis serovar D strain UW-3 (VR-885; ATCC), Chlamydia muridarum (VR-123; ATCC), and Chlamydia caviae (laboratory of Roger Rank, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) (41) were cultured in HeLa cells unless stated otherwise. EBs were isolated as previously described (25), and stocks were stored at −80°C in SPG buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM sodium phosphate, and 5 mM l-glutamic acid).

Glycogen staining.

Staining of glycogen in the inclusions was performed as described (17). Briefly, HeLa cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C (5% CO2). Cells were infected with C. trachomatis L2 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) for 1 h. After incubation, the buffer was replaced by growth medium with KSK213 or KSK120 at 5 μM or 0.5% DMSO. Infection proceeded for 48 h before the growth medium was removed, and cells were stained with potassium iodine (Sigma) and iodine (Sigma) in 50% methanol and 50% glycerol for 30 min. Afterward, the iodine solution was removed, and the samples were air dried for 90 min. Samples were visualized with a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope.

Characterization of C. trachomatis inclusions by automated microscopy.

Monolayers of HeLa cells in 96-well plates were infected with C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu at an MOI of 0.5 in HBSS (Gibco). After 1 h, the buffer was substituted with growth medium containing 2.5 μM, 5 μM, or 10 μM KSK213 or just DMSO. Infection proceeded for 45 to 48 h at 37°C (5% CO2), and then cells were fixed with methanol and the inclusions were stained with in-house anti-EB rabbit antibodies (42) (1:1,000) for 1 h followed by washing with water 3×. Inclusions were visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 1 h. Excess antibody was washed away with water, and the plates were analyzed by automated microscopy (ArrayScan VTI HCS; Thermo Scientific). Experiments were performed three times in triplicate.

qPCR.

HeLa cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 105 cells/well. The following day, the cells were infected with Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu in HBSS at an MOI of 3. After 1 h, the buffer was replaced with growth medium containing KSK213 at 10 μM or 1 μM, 0.5% DMSO, or 1 μg/ml doxycycline as a control. Incubation proceeded for 48 h, and then the cells were osmotically lysed by the addition of Milli-Q (MQ) water followed by a 20-min incubation at room temperature (RT). 4× SPG was added to a final concentration of 1×, and the supernatant from the wells was centrifuged at 20,000 × g, 4°C for 15 min. The pellets with EBs were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) once, and DNA was extracted using DNeasy cell culture kit (Qiagen) and spin columns from E.Z.N.A. DNA extraction from tissue (Omega) according to the manufacturer’s (Qiagen) conditions. Standard genomic DNA was extracted using the same kits from gradient-purified Chlamydia EB stocks isolated as previously described (25).

omcB primers (300 nM) and omcB probe (100 nM) (Table S1 in the supplemental material) were mixed with 5 μl of extracted DNA and added to TaqMan Fast Advanced master mix (Applied Biosystems) in a total volume of 25 μl, and qPCR was performed in a QuantStudio 7 Flex real-time qPCR machine (Applied Biosystems). The program selected was the following: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 s and 60°C for 20 s. The resulting threshold cycle (CT) values were compared to the standard DNA and quantified. Experiments were performed twice in triplicate for each condition.

Internalization assay.

HeLa cells were infected with C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu at an MOI of 0.5. After 1 h of infection, the cell supernatant was replaced with growth medium containing 2.5 μM KSK213 or an equal volume of DMSO. EB progeny was harvested 46 hpi by lysing the cells with water for 20 min at RT and adding SPG (4× to final 1× SPG) before storing at −80°C until use. Equal volumes of DMSO- and KSK213-treated progeny were used to infect HeLa cells seeded on coverslips. To determine the capacity of the progeny to invade cells, EBs were incubated for 1 h at 37°C before unattached bacteria were washed away with PBS. Growth medium was then added, and infection was allowed to proceed an additional hour before cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at RT. Half of the coverslips were treated with 0.1% saponin for 5 min to permeabilize the cells. Cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at RT or at 4°C overnight. EBs were stained with monoclonal antibody (MAb) anti-chlamydia lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Chlamydia Biobank catalog no. CT601; RRID, AB_2721933) (1:1,000) and donkey anti-mouse Alexa 594 (Invitrogen) (1:1,000). Cells were stained with HCS CellMask blue stain (Thermo Fisher). The fraction of infected cells was calculated by taking the number of EBs from permeabilized cells and subtracting the number of EBs from nonpermeabilized cells and then dividing by the number of EBs from permeabilized cells. The infection rate was calculated by setting the DMSO-treated infection fraction to 100%. Data were collected from three independent experiments. From each experiment, the number of IFUs was quantified for 100 cells for each condition. Images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse C1 Plus scanning laser confocal microscope using a 60× oil immersion objective. Automated EZ-C1 software was used to capture the images, together with a Nikon Digital sight DS-U2 camera controller and a Nikon C1-SHV camera. We generated projection images by z-stacks and analyzed them with ImageJ software.

RT-qPCR.

HeLa cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 105 cells/well. After 24 h, they were infected with Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu in HBSS at an MOI of 3. After 1 h, the buffer was replaced with growth medium containing KSK213 at 10 μM or with 0.5% DMSO. The plates were incubated for 48 h, and the cells were lysed with MQ water for 20 min. 4× SPG was added to a final concentration of 1×, and fresh HeLa cells previously seeded in 24-well plates were reinfected. After 1 h, the buffer was replaced with growth medium. RNA was isolated at 1 hpi, 3 hpi, or 5 hpi using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase treatment was performed in the column by adding 80 μl of DNase I in RDD buffer (Qiagen) and incubating for 30 min at 37°C. The concentrations and quality of RNA was determined by Nanodrop spectrophotometer measurements (A260/280). RNA was stored at −80°C until use.

Synthesis of cDNA was performed with RevertAid first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 0.6 to 0.7 μg of RNA in 20 μl and according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All of the cDNA product was mixed for qPCR with 2× SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) to a total concentration of 1× SYBR green. Primers corresponding to genes expressed at different time points of the infection were designed or selected from other publications (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The primers were added at a concentration of 300 nM in a total of 50 μl of PCR mix. qPCR was performed in a QuantStudio 7 Flex real-time qPCR instrument using the following program: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 90°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min followed by melt curve generation at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 15 s. ΔΔCq values were calculated from the mean of six quantification cycle (Cq) values generated using QuantStudio real-time PCR software and establishing 16S rRNA as expression control. Relative fold change in expression comparing KSK213- to DMSO-treated samples was calculated by the 2–ΔΔCq (Livak) method. Melt curves were analyzed to identify nonspecific binding. The final PCR products were also analyzed by 1% agarose gels to identify background gene expression. Experiments were performed twice with RNA extraction in biological triplicates per condition and technical duplicates on qPCR.

Transmission electron microscopy.

HeLa cells plated in 6-well plates at 6 × 105 cells/well were infected with Chlamydia trachomatis L2/434/Bu at an MOI of 0.5. After 1 h, the buffer was replaced with growth medium containing DMSO or KSK213 at 10 μM, and incubation proceeded for 48 h. One set of samples was fixed and processed for TEM, while the other was used to reinfect cells. EBs were isolated by osmotic lysis with MQ water followed by SPG 4× addition to 1× concentration and were used to infect fresh HeLa cells. After 1 h, the medium was replaced by growth medium, and the cells were fixed at 1 hpi, 3 hpi, or 5 hpi prior to imaging. Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (TAAB Laboratories, Aldermaston, England) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated with ethanol, a final step in propylene oxide, and embedded in Spurr’s resin (TAAB Laboratories, Aldermaston, England). Samples were sectioned 70 nm thick and picked on Formvar coated Cu grids, contrasted with uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate, and finally examined with a Talos 120C (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) operating at 120 kV. Micrographs were acquired with a Ceta 16M charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) using TEM Image and Analysis software version 4.17 (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Selection for KSK213 resistance and whole-genome sequencing.

Generation of the KSK213-resistant strain was achieved by repetitive passaging of the C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu strain in 0.5 μM KSK213 (later passages at 0.7 μM). Initially, almost all of the harvested bacteria were passaged onto new cells to maintain the MOI. As the strain became more resistant, the amount of harvest that was passaged was gradually reduced. Once high-level resistance was detected, the resistant strain was clonally purified, and DNA was prepared from gradient-purified bacteria. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy DNA tissue kit (Qiagen).

DNA libraries for whole-genome sequencing were constructed using the TruSeq DNA Library preparation kits (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Samples were sequenced using Illumina MiSeq technology to produce 2 × 151-bp pair-end reads according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following sequencing, sequence reads were trimmed of low-quality bases using fastp software version 0.20.0 (43). The passed filter sequences were assembled using a SPAdes assembler version 3.11.1. (44). We performed read mapping and variant calling using CLC Genomics workbench version 20.0.4 (Qiagen, Denmark), using the Basic Variant Detection tool with ploidy set to 1, ignoring positions with coverage above 200,000 and broken pairs and nonspecific matches. The minimum read length was set to 20, minimum coverage was set to 10, and there was a minimum frequency of 90%.

Reinfection assay.

Experiments to measure the effect of the compounds on progeny reinfection were performed as described previously (16). Briefly, cells were infected with Chlamydia trachomatis (serovar L2, D, or A), Chlamydia muridarum, or Chlamydia caviae in HBSS at an MOI of 0.5. In all infections with serovars A or D, we centrifuged for 30 min at 900 × g and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After 1 h, the HBSS was replaced with growth medium supplemented with KSK213 at different concentrations. The infected cells were incubated for 46 to 48 h or 36 h for C. muridarum at 37°C (5% CO2). Cells and inclusions were osmotically lysed by the addition of MQ water and incubated for 20 min at RT. After incubation, 4× SPG was added to the wells, and a fresh monolayer of HeLa cells was infected with the 1× SPG supernatant diluted in HBSS. The buffer was replaced by growth medium after 1 h, and incubation proceeded for 44 to 46 h or 36 h for C. muridarum. The infected cells were then fixed with methanol, incubated for 10 min, and washed with PBS. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 1% BSA, and subsequent staining with in-house anti-EB rabbit antibodies (1:1,000) in C. trachomatis and C. muridarum was performed. C. caviae was stained with anti-Slc1 C. caviae antibodies (1:500) kindly provided by Barbara Sixt (Umeå University). After 1 h, the cells were washed 3× with MQ water and then stained with FITC conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and DAPI for 1 h. The plates were washed again with MQ water and analyzed by ArrayScan. Experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate or triplicate.

Statistical analyses.

All of the analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism version 5. Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc tests were performed when multiple groups were compared. Mann-Whitney U test was used for pairwise comparisons.

Data availability.

Sequences have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers CP054426 to CP054433.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Barbara Sixt for her advice, the A2EN and HT29 cell lines, the C. caviae strain, and the C. caviae antibodies. We thank Niklas Arnberg and Nitesh Mistry for providing the human cell line collection. We thank Xijia Liu for advice in the statistical analyses. We also thank Betty Guo and Jörgen Johansson for their advice and comments on the manuscript.

Umeå Centre for Microbial Research (UCMR) and Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden (MIMS) are acknowledged. The authors acknowledge the facilities and technical assistance of Umeå Core Facility Electron Microscopy (UCEM) at the Chemical Biological Centre (KBC), Umeå University, a part of the National Microscopy Infrastructure NMI (VR-RFI 2016-00968).

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2017-02339 and 2017-00695 for F.A., Å.G., and S.B., and 2018-04589 for F.A.), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation (KAW 2013.0031 for F.A. and S.B.), the Göran Gustafsson foundation, the Kempe Foundation (SMK-1755), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SB12-0070), the National Institutes of Health (R01AI134847-01A1), the Erling Perssons Stiftelse, the Michael J. Fox foundation (all for F.A.), and the Swedish Government Fund for Clinical Research (for Å.G.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2012. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections—2008. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. 2015. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 10:e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan SJ, Aaron KJ, Schwebke JR, Van Der Pol BJ, Hook EW. 2018. Defining the urethritis syndrome in men using patient reported symptoms. Sex Transm Dis 45:e40–e42. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denison HJ, Curtis EM, Clynes MA, Bromhead C, Dennison EM, Grainger R. 2016. The incidence of sexually acquired reactive arthritis: a systematic literature review. Clin Rheumatol 35:2639–2648. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3364-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB. 2010. Risk of sequelae after chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. J Infect Dis 201:134–155. doi: 10.1086/652395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AbdelRahman YM, Belland RJ. 2005. The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beeckman DS, De Puysseleyr L, De Puysseleyr K, Vanrompay D. 2014. Chlamydial biology and its associated virulence blockers. Crit Rev Microbiol 40:313–328. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.726210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw EI, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Scidmore MA, Fields KA, Hackstadt T. 2000. Three temporal classes of gene expression during the Chlamydia trachomatis developmental cycle. Mol Microbiol 37:913–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufrêne YF. 2015. Sticky microbes: forces in microbial cell adhesion. Trends Microbiol 23:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belland RJ, Zhong G, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, Sharma J, Beatty WL, Caldwell HD. 2003. Genomic transcriptional profiling of the developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331135100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohlhoff SA, Hammerschlag MR. 2015. Treatment of chlamydial infections: 2014 update. Expert Opin Pharmacother 16:205–212. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.999041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. 2011. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien KS, Emerson P, Hooper PJ, Reingold AL, Dennis EG, Keenan JD, Lietman TM, Oldenburg CE. 2019. Antimicrobial resistance following mass azithromycin distribution for trachoma: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 19:e14–e25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30444-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pond MJ, Nori AV, Witney AA, Lopeman RC, Butcher PD, Sadiq ST. 2014. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant mycoplasma genitalium in nongonococcal urethritis: the need for routine testing and the inadequacy of current treatment options. Clin Infect Dis 58:631–637. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Hamasuna R. 2008. Azithromycin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium—positive patients with nongonococcal urethritis is associated with induced macrolide resistance. Clin Infect Dis 47:1546–1553. doi: 10.1086/593188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good JAD, Silver J, Núñez-Otero C, Bahnan W, Krishnan KS, Salin O, Engström P, Svensson R, Artursson P, Gylfe Å, Bergström S, Almqvist F. 2016. Thiazolino 2-pyridone amide inhibitors of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity. J Med Chem 59:2094–2108. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engström P, Syam Krishnan K, Ngyuen BD, Chorell E, Normark J, Silver J, Bastidas RJ, Welch MD, Hultgren SJ, Wolf-Watz H, Valdivia RH, Almqvist F, Bergström S. 2014. A 2-pyridone-amide inhibitor targets the glucose metabolism pathway of Chlamydia trachomatis. mBio 6:e02304-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02304-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Good JAD, Kulén M, Silver J, Krishnan KS, Bahnan W, Núñez-Otero C, Nilsson I, Wede E, de Groot E, Gylfe Å, Bergström S, Almqvist F. 2017. Thiazolino 2-pyridone amide isosteres as inhibitors of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity. J Med Chem 60:9393–9399. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulén M, Núñez-Otero C, Cairns AG, Silver J, Lindgren AEG, Wede E, Singh P, Vielfort K, Bahnan W, Good JAD, Svensson R, Bergström S, Gylfe Å, Almqvist F. 2019. Methyl sulfonamide substituents improve the pharmacokinetic properties of bicyclic 2-pyridone based Chlamydia trachomatis inhibitors. Med Chem Commun (Camb) 10:1966–1987. doi: 10.1039/C9MD00405J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoemaker RH. 2006. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat Rev Cancer 6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovering F. 2013. Escape from Flatland 2: complexity and promiscuity. Med Chem Commun (Camb) 4:515–519. doi: 10.1039/c2md20347b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moulder JW. 1991. Interaction of Chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev 55:143–190. doi: 10.1128/MR.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scidmore MA, Rockey DD, Fischer ER, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. 1996. Vesicular interactions of the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion are determined by chlamydial early protein synthesis rather than route of entry. Infect Immun 64:5366–5372. doi: 10.1128/IAI.64.12.5366-5372.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai W, Li Z. 2014. Conserved type III secretion system exerts important roles in Chlamydia trachomatis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7:5404–5414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. 1981. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/IAI.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid SL, Conner SD. 2003. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature 422:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nature01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rey-Ladino J, Koochesfahani KM, Zaharik ML, Shen C, Brunham RC. 2005. A live and inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis strain induces the maturation of dendritic cells that are phenotypically and immunologically distinct. Infect Immun 73:1568–1577. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1568-1577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aeberhard L, Banhart S, Fischer M, Jehmlich N, Rose L, Koch S, Laue M, Renard BY, Schmidt F, Heuer D. 2015. The proteome of the isolated Chlamydia trachomatis containing vacuole reveals a complex trafficking platform enriched for retromer components. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004883. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elwell CA, Kierbel A, Engel JN. 2011. Species-specific interactions of Src family tyrosine kinases regulate Chlamydia intracellular growth and trafficking. mBio 2:e00082-11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00082-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao X, Gylfe Å, Sturdevant GL, Gong Z, Xu S, Caldwell HD, Elofsson M, Fan H. 2014. Benzylidene acylhydrazides inhibit chlamydial growth in a type III secretion- and iron chelation-independent manner. J Bacteriol 196:2989–3001. doi: 10.1128/JB.01677-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mojica SA, Salin O, Bastidas RJ, Sunduru N, Hedenström M, Andersson CD, Núñez-Otero C, Engström P, Valdivia RH, Elofsson M, Gylfe Å. 2017. N-acylated derivatives of sulfamethoxazole block Chlamydia fatty acid synthesis and interact with FabF. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00716-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00716-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Good JAD, Andersson C, Hansen S, Wall J, Krishnan KS, Begum A, Grundström C, Niemiec MS, Vaitkevicius K, Chorell E, Wittung-Stafshede P, Sauer UH, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Almqvist F, Johansson J. 2016. Attenuating Listeria monocytogenes virulence by targeting the regulatory protein PrfA. Cell Chem Biol 23:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Court DL, Gan J, Liang YH, Shaw GX, Tropea JE, Costantino N, Waugh DS, Ji X. 2013. RNase III: genetics and function; structure and mechanism. Annu Rev Genet 47:405–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunes A, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP. 2013. Genomic features beyond Chlamydia trachomatis phenotypes: what do we think we know? Infect Genet Evol 16:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borel N, Polkinghorne A, Pospischil A. 2018. A review on chlamydial diseases in animals: still a challenge for pathologists? Vet Pathol 55:374–390. doi: 10.1177/0300985817751218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, Davis RW. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, Hickey EK, Peterson J, Utterback T, Berry K, Bass S, Linher K, Weidman J, Khouri H, Craven B, Bowman C, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Nelson W, DeBoy R, Kolonay J, McClarty G, Salzberg SL, Eisen J, Fraser CM. 2000. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res 28:1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson JH, Porcella SF, Mcclarty G, Caldwell HD. 2005. Comparative genomic analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis oculotropic and genitotropic strains. Infect Immun 73:6407–6418. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6407-6418.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonner CA, Byrne GI, Jensen RA. 2014. Chlamydia exploit the mammalian tryptophan-depletion defense strategy as a counter-defensive cue to trigger a survival state of persistence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:17. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckner LR, Schust DJ, Ding J, Nagamatsu T, Beatty W, Chang TL, Greene SJ, Lewis ME, Ruiz B, Holman SL, Spagnuolo RA, Pyles RB, Quayle AJ. 2011. Innate immune mediator profiles and their regulation in a novel polarized immortalized epithelial cell model derived from human endocervix. J Reprod Immunol 92:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murray ES. 1964. Guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis virus: I. Isolation and identification as a member of the psittacosis-lymphogranuloma-trachoma group. J Infect Dis 114:1–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/114.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marwaha S, Uvell H, Salin O, Lindgren AEG, Silver J, Elofsson M, Gylfe Å. 2014. N-acylated derivatives of sulfamethoxazole and sulfafurazole inhibit intracellular growth of Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2968–2971. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02015-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. 2018. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequences have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers CP054426 to CP054433.