Two novel ISCR1-associated dfr genes, dfrA42 and dfrA43, were identified from trimethoprim (TMP)-resistant Proteus strains and were shown to confer high levels of TMP resistance (MIC, ≥1,024 mg/liter) when cloned into Escherichia coli isolates. These genes were hosted by complex class 1 integrons, suggesting their potential for dissemination.

KEYWORDS: antimicrobial resistance gene, dihydrofolate reductase, enzymatic parameter, inhibitor binding, integron, mechanism of resistance, trimethoprim

ABSTRACT

Two novel ISCR1-associated dfr genes, dfrA42 and dfrA43, were identified from trimethoprim (TMP)-resistant Proteus strains and were shown to confer high levels of TMP resistance (MIC, ≥1,024 mg/liter) when cloned into Escherichia coli isolates. These genes were hosted by complex class 1 integrons, suggesting their potential for dissemination. Analyses of enzymatic parameters and TMP affinity were performed, and the results suggested that the mechanism of TMP resistance for these novel dihydrofolate reductases (DHFRs) is the reduction of binding with TMP.

INTRODUCTION

Trimethoprim (TMP), synthesized for clinical use in early 1960, is a competitive inhibitor for bacterial enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (1). As a result of its simple structure and good efficacy, TMP and its combination with sulfonamides have been broadly used in clinics and animal farms for several decades (2–5). The use, particularly preventative use, of this inexpensive and effective drug for the treatment of bacterial infection further increases the prevalence of TMP-resistant bacteria around the world. Since the report of the first plasmid-mediated dfr gene in 1972 (6), >40 different dfr genes responsible for high-level TMP resistance have been identified in Gram-negative bacteria (7–11). Their products are mainly classified into two DHFR families, i.e., DfrA and DfrB (12). The acquisition of extra dfr genes in mobile genetic elements, including integrons, plasmids, and transposons, is an important cause for TMP resistance in bacteria (3, 7–11).

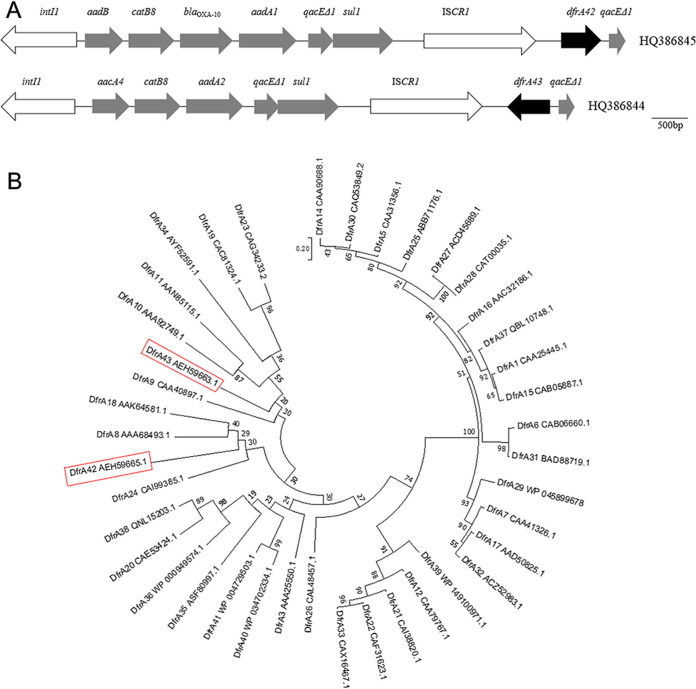

By screening for antibiotic-resistant bacteria as previously reported (13, 14), two Proteus strains, Proteus vulgaris LK4 and Proteus penneri LTe9, were isolated from surface waters near hospitals in Jinan, China. Integrase-coding genes and ISCR1 elements were identified from these strains by PCR amplification using IntI1F/IntI1R (15) and 513mF/513mR (14) primers. Gene cassettes of class 1 integron and ISCR1-containing downstream fragments were then amplified using primers hep58/hep59 (16) and 513BF/qacEΔ1-B (14), respectively. A 3.2-kb amplicon with aadB-catB8-blaOXA-10-aadA1 gene cassettes was identified in P. vulgaris LK4, and a 2.4-kb amplicon with aacA4-catB8-aadA2 gene cassettes was identified in P. penneri LTe9. Using primer pair 513BF/qacEΔ1-B, 1.3-kb ISCR1-containing fragments were identified in both strains. After sequencing, the 1.3-kb fragments from the two strains were shown to putatively encode a 177- and a 195-amino-acid-long protein, respectively. The genetic structures and full sequences of these complex class 1 integrons hosted by the two Proteus strains (HQ386845, 8,639 bp; HQ386844, 7,927 bp) were obtained by assembling sequences of PCR amplicons and are shown in Fig. 1A. Gaps were closed by Sanger sequencing. By homologous searches using the BLAST algorism, the two putative proteins were shown to have the highest sequence similarities with known family A DHFRs. Amino acid sequences of known DfrAs and these two putative proteins were subsequently phylogenetically analyzed with MEGA to generate a maximum-likelihood tree (JTTmodel, 1,000 bootstraps) (Fig. 1B). This phylogenetic analysis suggested that these two putative proteins indeed encode family A DHFRs. Further comparison of the two DHFRs with all 41 previously known family A DHFRs suggested that they have low sequence similarities with all other DHFRs: the most-similar DHFRs with those from P. vulgaris LK4 are DfrA8, DfrA24, and DfrA18, which share 34%, 32%, and 32% identity, respectively; whereas the most-similar DHFRs with those from P. penneri LTe9 are DfrA9, DfrA10, and DfrA11, which share 35%, 32%, and 29% identity, respectively. Therefore, a suggestion can be made that the complex class 1 integrons from P. vulgaris LK4 and P. penneri LTe9 encode a novel family A DHFR. The two novel genes were subsequently named dfrA42 and dfr43, and their proteins were designated DfrA42 and DfrA43.

FIG 1.

Genetic structures of two novel dfr genes and phylogenetic analysis of DHFRs. (A) Genetic structures of complex class 1 integrons. Gray and black arrows, antibiotic resistance genes (dfrA42 and dfrA43); white arrows, conserved genetic elements of complex class 1 integrons; accession numbers HQ386845 and HQ386844, respectively. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of DHFRs. Red boxes, DfrA42 and DfrA43. GenBank accession numbers are listed alongside protein names. Numbers at each node are bootstrap values. Bar, evolutionary distance.

To further confirm that these dfr genes, along with other previously known representative acquired TMP resistance-conferring dfr genes, can indeed lead to TMP resistance, we cloned coding regions of folA (encoding Escherichia coli chromosomal DHFR [EcDHFR], 480 bp), dfrA1 (474 bp), dfrA42 (574 bp), and dfrA43 (588 bp) into the pACYC184 vector (low copy number, downstream of the catI gene) and pET15b(+) vector (downstream of the T7 promoter), using the GB/dir homologous recombination-based cloning method (17), and transformed the recombinant vectors into E. coli DH5α. All transformants of recombinant plasmid have been verified by PCR. Promoters driving the expression of folA and dfrA genes were supplied by the backbones of the two common cloning vectors: for pET15b(+), folA/dfrA genes were under the control of T7 promoter; for pACYC184, folA/dfrA genes were under the control of the promoter for chloramphenicol resistance gene catI, which drives the expression of both dfrA/folA and catI. MICs for TMP and co-trimoxazole were measured for P. vulgaris LK4, P. penneri LTe9, and all constructed E. coli strains using the broth microdilution method (Table 1). Similar high levels of TMP resistance (>1,024 g/liter) were found for dfrA42- and dfrA43-harboring E. coli strains, confirming that they can indeed lead to TMP resistance. Meanwhile the two novel dfr genes can also lead to strong resistance to co-trimoxazole (>64/1,216 g/liter). These results show that both dfrA42 and dfrA43 are functional dfr genes that lead to resistance to TMP and co-trimoxazole.

TABLE 1.

MICs for TMP and co-trimoxazole in dfr-containing and control strains

| Strain, plasmid | MIC (mg/liter) (susceptibilitya) |

|

|---|---|---|

| TMP | Co-trimoxazole | |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 4 (S) | 1/19 (S) |

| P. vulgaris LK4, dfrA42 | 3,072 (R) | ≥64/1,216 (R) |

| P. penneri LTe9, dfrA43 | 3,072 (R) | ≥64/1,216 (R) |

| P. mirabilis JN29, dfrA1 | 4,096 (R) | ≥64/1,216 (R) |

| E. coli DH5α | 4 (S) | 0.0625/1.1875 (S) |

| E. coli DH5α, pET15b | 4 (S) | 0.25/4.75 (S) |

| E. coli DH5α, folA-pET15b | 8 (S) | 0.5/9.5 (S) |

| E. coli DH5α, dfrA42-pET15b | 3,072 (R) | ≥64/1,216 (R) |

| E. coli DH5α, dfrA43-pET15b | 3,072 (R) | 64/1,216 (R) |

| E. coli DH5α, dfrA1-pET15b | 3,072 (R) | 64/1,216 (R) |

| E. coli DH5α, pACYC184 | 2 (S) | 0.25/4.75 (S) |

| E. coli DH5α, folA-pACYC184 | 4 (S) | 1/19 (S) |

| E. coli DH5α, dfr42-pACYC184 | 2,048 (R) | 64/1,216 (R) |

| E. coli DH5α, dfrA43-pACYC184 | 1,024 (R) | 64/1,216 (R) |

| E. coli DH5α, dfrA1-pACYC184 | 2,048 (R) | 64/1,216 (R) |

R, resistant; S, susceptible.

Resistance mechanisms of the two novel DHFRs found in this work were further analyzed biochemically. To determine the enzymatic parameters of TMP resistance-conferring DHFRs, recombinant EcDHFR, DfrA1, DfrA42, and DfrA43 proteins were overexpressed using the pET15b(+) vector and purified to apparent homogeneity. NADPH:DHF (dihydrofolate) oxidoreductase enzymatic parameters were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of rates of decreasing absorbance at 340 nm (for NADPH) at different concentrations of DHF as previously reported (18). The kinetic constants Km and Kcat were calculated and are shown in Table S1. With these results, a conclusion that TMP resistance conferred by these DHFRs is due to significantly higher catalytic activities or efficiencies cannot be drawn. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was performed to compare the binding of TMP with TMP-sensitive and TMP-resistant DHFRs following previously published protocol (19). A strong and significant (10- to 40-fold; P = 5.12 × 10−6 for DfrA42, P = 5.64 × 10−9 for DfrA43) reduction of affinity with TMP was found for DfrA42 and DfrA43 in comparison with EcDHFR (Table S1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), leading to the suggestion that reduction in binding of TMP is responsible for increased TMP resistance for DfrA42 and DfrA43.

In conclusion, two novel acquired TMP resistance-conferring family A DHFRs were identified from complex class 1 integrons from Proteus species and named DfrA42 and DfrA43. Phenotypic analysis, measurement of enzymatic parameters, and affinity analysis with TMP of these novel TMP-resistant DHFRs and previously known representative DHFRs suggest that reduction in TMP binding is responsible for TMP resistance.

Data availability.

Nucleotide sequences for all dfr genes in this study can be found in GenBank under accession numbers HQ386845 (dfrA42-containing integron), HQ386844 (dfrA43-containing integron), JX089581.1 (dfrA1), and NC_000913.3 (folA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Luyao Bie for providing the dfrA1 gene and Lichuan Gu for help on protein purification. We also thank the Core Facilities for Life and Environmental Sciences of Shandong University for assistance with ITC and biochemical parameter analysis.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 31770042 and 31770043), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2017YFD0400300), Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (grant number 2020CXGC011305), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (grant number ZR2020MH308), the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (grant numbers 2018JC013 and 2018JC027), and the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology Open Project Funds, Shandong University (grant number M2019-04).

The funding sources have no roles in study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Then RL. 2004. Antimicrobial dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors—achievements and future options: review. J Chemother 16:3–12. 10.1179/joc.2004.16.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huovinen P, Sundström L, Swedberg G, Sköld O. 1995. Trimethoprim and sulfonamide resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:279–289. 10.1128/aac.39.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sköld O. 2001. Resistance to trimethoprim and sulfonamides. Vet Res 32:261–273. 10.1051/vetres:2001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wrobel A, Arciszewska K, Maliszewski D, Drozdowska D. 2020. Trimethoprim and other nonclassical antifolates an excellent template for searching modifications of dihydrofolate reductase enzyme inhibitors. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 73:5–27. 10.1038/s41429-019-0240-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kranz J, Schmidt S, Lebert C, Schneidewind L, Mandraka F, Kunze M, Helbig S, Vahlensieck W, Naber K, Schmiemann G, Wagenlehner FM. 2018. The 2017 update of the German clinical guideline on epidemiology, diagnostics, therapy, prevention, and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in adult patients. Part II: therapy and prevention. Urol Int 100:271–278. 10.1159/000487645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming MP, Datta N, Gruneberg RN. 1972. Trimethoprim resistance determined by R factors. Br Med J 1:726–728. 10.1136/bmj.1.5802.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tagg KA, Watkins LF, Moore MD, Bennett C, Joung YJ, Chen JC, Folster JP. 2019. Novel trimethoprim resistance gene dfrA34 identified in Salmonella Heidelberg in the USA. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:38–41. 10.1093/jac/dky373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambrose SJ, Hall RM. 2019. Novel trimethoprim resistance gene, dfrA35, in IncC plasmids from Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:1863–1866. 10.1093/jac/dkz148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wüthrich D, Brilhante M, Hausherr A, Becker J, Meylan M, Perreten V. 2019. A novel trimethoprim resistance gene, dfrA36, characterized from Escherichia coli from calves. mSphere 4:e00255-19. 10.1128/mSphere.00255-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sánchez-Osuna M, Cortés P, Llagostera M, Barbé J, Erill I. 2020. Exploration into the origins and mobilization of dihydrofolate reductase genes and the emergence of clinical resistance to trimethoprim. Microb Genom 6:mgen000440. 10.1099/mgen.0.000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambrose SJ, Hall RM. 2020. A novel trimethoprim resistance gene, dfrA38, found in a sporadic Acinetobacter baumannii isolate. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:3694–3695. 10.1093/jac/dkaa379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Recchia GD, Hall RM. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology 141:3015–3027. 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu H, Broersma K, Miao V, Davies J. 2011. Class 1 and class 2 integrons in multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria isolated from the Salmon River, British Columbia. Can J Microbiol 57:460–467. 10.1139/w11-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia R, Ren Y, Xu H. 2013. Identification of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance qnr genes in multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from hospital wastewaters and receiving waters in the Jinan area, China. Microb Drug Resist 19:446–456. 10.1089/mdr.2012.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu H, Davies J, Miao V. 2007. Molecular characterization of class 3 integrons from Delftia spp. J Bacteriol 189:6276–6283. 10.1128/JB.00348-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White PA, McIver CJ, Rawlinson WD. 2001. Integrons and gene cassettes in the Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2658–2661. 10.1128/aac.45.9.2658-2661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Li Z, Jia R, Yin J, Li A, Xia L, Yin Y, Müller R, Fu J, Stewart AF, Zhang Y. 2018. ExoCET: exonuclease in vitro assembly combined with RecET recombination for highly efficient direct DNA cloning from complex genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 46:e28. 10.1093/nar/gkx1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cammarata M, Thyer R, Lombardo M, Anderson A, Wright D, Ellington A, Brodbelt JS. 2017. Characterization of trimethoprim resistant E. coli dihydrofolate reductase mutants by mass spectrometry and inhibition by propargyl-linked antifolates. Chem Sci 8:4062–4072. 10.1039/c6sc05235e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batruch I, Javasky E, Brown ED, Organ MG, Johnson PE. 2010. Thermodynamic and NMR analysis of inhibitor binding to dihydrofolate reductase. Bioorg Med Chem 18:8485–8492. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Nucleotide sequences for all dfr genes in this study can be found in GenBank under accession numbers HQ386845 (dfrA42-containing integron), HQ386844 (dfrA43-containing integron), JX089581.1 (dfrA1), and NC_000913.3 (folA).