Intravenous administration of the last-line polymyxins results in poor drug exposure in the lungs and potential nephrotoxicity, whereas inhalation therapy offers better pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics for pulmonary infections by delivering the antibiotic directly to the infection site. However, polymyxin inhalation therapy has not been optimized, and adverse effects can occur.

KEYWORDS: polymyxin, lung epithelial cells, toxicity, apoptosis, zinc, calcium

ABSTRACT

Intravenous administration of the last-line polymyxins results in poor drug exposure in the lungs and potential nephrotoxicity, whereas inhalation therapy offers better pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics for pulmonary infections by delivering the antibiotic directly to the infection site. However, polymyxin inhalation therapy has not been optimized, and adverse effects can occur. This study aimed to quantitatively determine the intracellular accumulation and distribution of polymyxins in single human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Cells were treated with the iodine-labeled polymyxin probe FADDI-096 (5.0 and 10.0 μM) for 1, 4, and 24 h. Concentrations of FADDI-096 in single A549 cells were determined by synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence microscopy. Concentration- and time-dependent accumulation of FADDI-096 within A549 cells was observed. The intracellular concentrations (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM], n ≥ 189) of FADDI-096 were 1.58 ± 0.11, 2.25 ± 0.10, and 2.46 ± 0.07 mM following 1, 4, and 24 h of treatment at 10 μM, respectively. The corresponding intracellular concentrations following the treatment at 5 μM were 0.05 ± 0.01, 0.24 ± 0.04, and 0.25 ± 0.02 mM (n ≥ 189). Over 24 h, FADDI-096 was mainly localized throughout the cytoplasm and nuclear region. The intracellular zinc concentration increased in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. This is the first study to quantitatively map the accumulation of polymyxins in human alveolar epithelial cells, and it provides crucial insights for deciphering the mechanisms of their pulmonary toxicity. Importantly, our results may shed light on the optimization of inhaled polymyxins in patients and the development of new-generation, safer polymyxins.

TEXT

Antibiotic resistance is a major global health challenge, and respiratory infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative bacteria are particularly worrisome (1–3). Given the dearth of new antibiotics active against MDR Gram-negative bacteria in the drug discovery pipeline, polymyxins are increasingly used as a last-line therapy (4–7). However, the current dosing recommendations for intravenously administered polymyxins are suboptimal, particularly for lung infections due to limited drug exposure at the infection site (8–12). Dose fractionation studies involving subcutaneous administration of polymyxins (up to 160 mg/kg/day with both polymyxin B and colistin) have shown minimal effectiveness in neutropenic murine lung infection models with Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (13, 14). Unfortunately, simply increasing the dose of intravenous polymyxins in patients is not feasible, as dose-dependent nephrotoxicity can occur in up to 60% of patients (15–17). Worryingly, the increased use of polymyxins in clinical practice has been accompanied by increasing reports of polymyxin resistance worldwide (18).

Inhalation of polymyxins has shown superior antimicrobial efficacy to intravenous administration for the treatment of patients with lung infections (19–21). Direct administration to the lungs also has the advantage of minimizing systemic availability and therefore nephrotoxicity (12, 19, 22). However, current inhaled polymyxin therapy is empirical, and optimization of the dosage regimens using pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic/toxicodynamic (PK/PD/TD) principles is urgently required (23–26). While inhaled polymyxins may produce very high drug concentrations in the lungs (up to 1,137 mg/liter in the human epithelial lining fluid [ELF]) (19, 22), they may also potentially cause local adverse effects (e.g., bronchospasm and chest tightness), which may lead to poor patient compliance and cessation of therapy (21, 27, 28). There is thus an urgent need to investigate the mechanism by which polymyxins cause pulmonary toxicity. We have recently reported that toxicity in human alveolar epithelial cells is time- and concentration-dependent and is mediated through both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis (29). Moreover, localization of polymyxins in mitochondria, mitochondrial toxicity, and resultant oxidative stress have been observed in both kidney and alveolar epithelial cells treated with polymyxins (29–32). However, no quantitative information is currently available on the disposition of polymyxins in single alveolar epithelial cells. Such knowledge is critical for elucidating the mechanisms of polymyxin-associated pulmonary toxicity, optimization of inhaled polymyxins, and development of novel strategies to ameliorate this toxicity. In the present study, we employed correlative synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) and confocal fluorescence microscopy to determine the intracellular accumulation of polymyxins in single human alveolar epithelial cells.

RESULTS

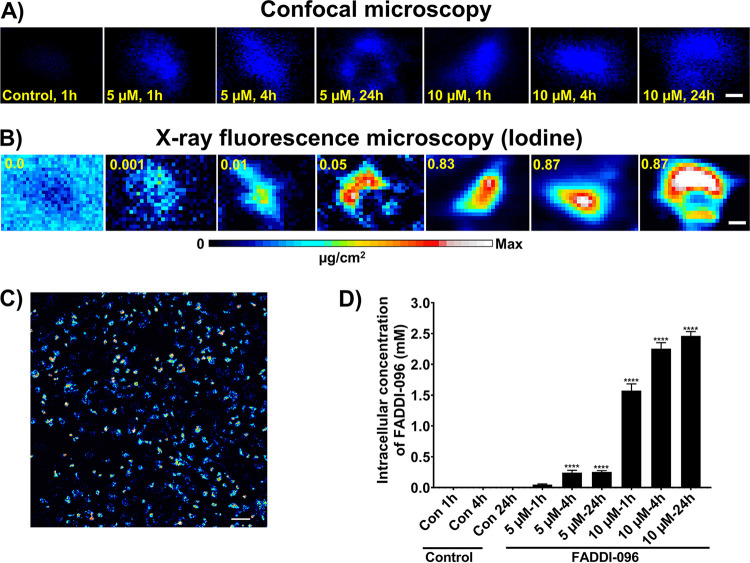

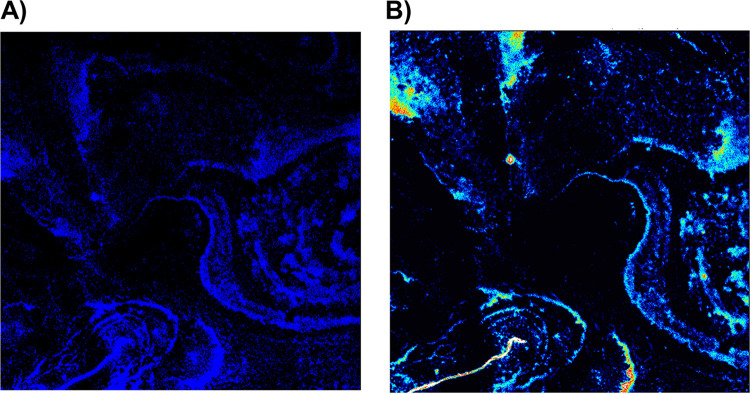

Figure 1 shows images from confocal fluorescence microscopy and XFM of the same cells for quantitative mapping of FADDI-096 in single human alveolar epithelial cells. In images acquired in the high-resolution mode, the fluorescence responses from FADDI-096 were mainly localized throughout the cytoplasm and nuclear region, with higher fluorescence intensity in the latter (Fig. 1A and B). The spatial correlation of the optical fluorescence from the dansyl group of FADDI-096 (Fig. 1A) and the iodine X-ray fluorescence signal from the XFM (Fig. 1B) in the same cells revealed a very consistent intracellular distribution of FADDI-096 in both XFM and fluorescence microscopy imaging. Furthermore, the overlaps of the detected fluorescence signals from iodine and dansyl groups were confirmed by XFM imaging and fluorescence microscopy, respectively (Fig. 2). Measurement of iodine content and the equivalent FADDI-096 concentration via XFM (Fig. S1 and Tables S1 to S3 in the supplemental material) revealed polymyxin accumulation within the cells (Fig. 1A to D). The concentration of FADDI-096 within the cells is detailed in Tables S1 and S2. There was a significant difference in the intracellular concentration between the 5.0 μM and 10.0 μM treatment groups at each time point, but minor changes within each group between 4 and 24 h. This shows nonlinear concentration-dependent (e.g., an ∼30-fold difference between the concentrations of 5.0 and 10.0 μM at 1 h) and time-dependent accumulation (e.g., ∼1.6-fold difference at 1 and 24 h with the 10.0 μM treatment) of the polymyxin probe in the A549 cells (Fig. 1D and Table S2). Overall, the intracellular concentrations of the polymyxin probe were substantially higher than the extracellular concentrations of 5 and 10 μM at both 1 h (10- and 150-fold, respectively) and 24 h (50- and 246-fold, respectively).

FIG 1.

Intracellular distribution of FADDI-096 in single A549 cells determined with confocal fluorescence microscopy (signal from dansyl) and synchrotron XFM imaging (signal from iodine). (A and B) A549 cells without treatment (control) and treated with 5.0 or 10.0 μM FADDI-096 for 1, 4, and 24 h. Signal intensities are linearly scaled for iodine from the minimum to the maximum; the numbers at the top of the relevant panels show the maximum pixel value (μg/cm2) in each sample. Bar, 5 μm. (C) Representative signal intensities from low-resolution XFM images of A549 cells treated with 10.0 μM FADDI-096 for 24 h. Bar, 50 μm. (D) Intracellular accumulation of FADDI-096 in single A549 cells measured by XFM (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = at least 189 cells; ****, P < 0.0001).

FIG 2.

Fluorescence signals from the (A) dansyl group and (B) iodine of FADDI-096 loaded on to the silicon nitride windows by fluorescence microscopy and XFM imaging, respectively.

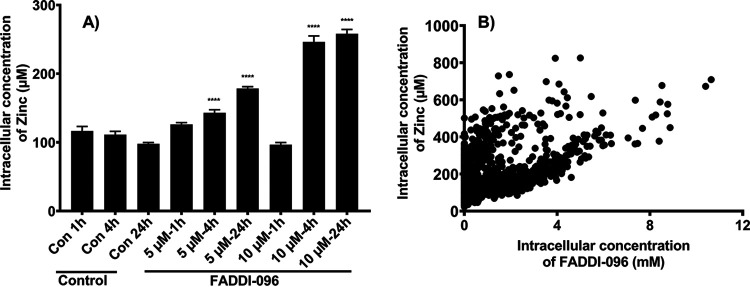

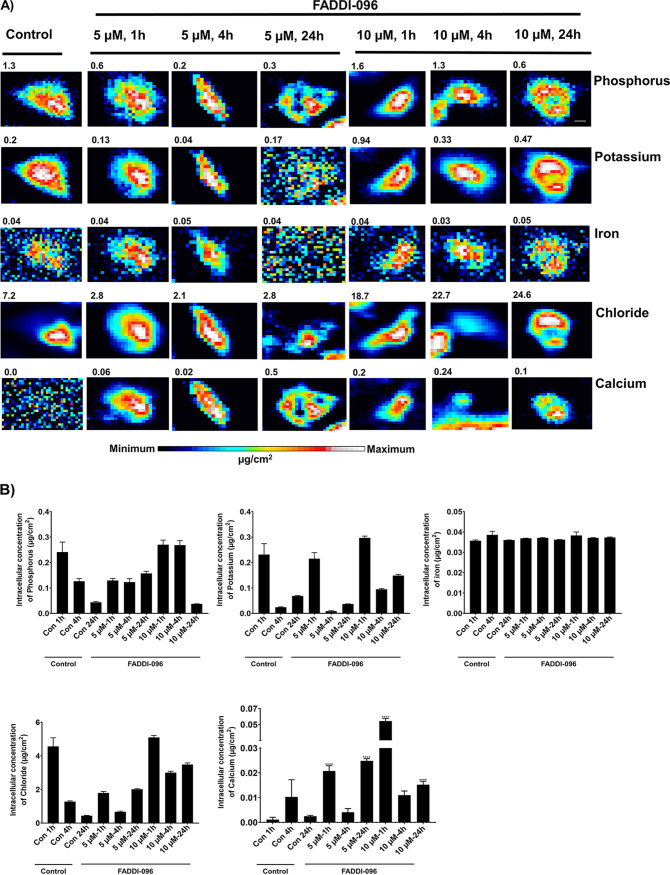

A concentration- and time-dependent increase in the intracellular zinc concentration was also observed (Fig. 3A). There was a positive correlation (P < 0.0001; Pearson’s r = 0.48) between intracellular concentrations of zinc and FADDI-096 (Fig. 3B) based on the readings on each pixel. With FADDI-096 treatments at 5 and 10 μM, intracellular concentration of calcium also significantly increased at both 1 h (18- and 16-fold, respectively) and 24 h (10- and 6-fold, respectively) (Fig. 4A and B). Compared to the untreated control at each time point, however, FADDI-096 did not dramatically alter the intracellular concentrations (i.e., varying within 3- to 5-fold) of potassium, iron, phosphorus, or chloride (Fig. 4).

FIG 3.

(A) Intracellular concentration of zinc in single A549 cells measured by XFM following treatments with 5.0 or 10.0 μM FADDI-096 for 1, 4, and 24 h (mean ± SEM; n = at least 189 cells; ****, P < 0.0001). (B) Correlation between the intracellular concentration of zinc and FADDI-096 in single human lung epithelial A549 cells treated with 5.0 or 10.0 μM FADDI-096 for 1, 4, and 24 h (P < 0.0001; Pearson’s r = 0.48).

FIG 4.

Intracellular distribution of elements (P, K, Fe, Cl, and Ca) in single A549 cells determined with XFM. (A) Untreated A549 cells (control) and cells treated with 5.0 or 10.0 μM FADDI-096 for 1, 4, and 24 h. Signal intensities are linearly scaled separately for each element from the minimum to the maximum; the numbers at the top of the relevant panels show the maximum pixel value (μg/cm2) in each sample. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Intracellular accumulation of elements in single A549 cells measured by XFM (mean ± SEM; n = at least 189 cells; ****, P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Direct administration of polymyxins to the lungs provides significant PK/PD/TD advantages by achieving high exposure in the epithelial lining fluid (ELF) with minimal systemic absorption (12, 19, 22). Inhalation of polymyxins mitigates the risk of their nephrotoxicity while achieving favorable clinical outcomes in patients with severe lung infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens (19–21, 33). However, high polymyxin concentrations achieved in the ELF following pulmonary delivery (e.g., up to 1,137 mg/liter [19]) have the potential to cause substantial accumulation of polymyxins in alveolar epithelial cells and lung toxicity. Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand the quantitative disposition of polymyxins in alveolar epithelial cells for optimizing inhalation therapy.

XFM has been shown as a powerful tool for measuring the spatiotemporal accumulation of metal-containing drugs in a model tumor microenvironment (34). In this study, we employed the dual-modality polymyxin FADDI-096 fluorescent probe, which contains nonradioactive iodine (XFM contrast) and a dansyl fluorophore (for fluorescence imaging) (35). FADDI-096 is structurally similar to the clinically available polymyxins (colistin and polymyxin B) with comparable antibacterial activity (as measured by MIC) and ability to cause oxidative damage in rat and human kidney proximal tubular cells (35). Thus, the chemical and pharmacological properties of FADDI-096 closely reflect those of clinically used colistin and polymyxin B. Direct imaging of FADDI-096 showed the overlap of fluorescence signals from the iodine and dansyl groups detected by XFM imaging and fluorescence microscopy, respectively, demonstrating the chemical stability of this polymyxin probe in A549 cells during the culture and imaging period (Fig. 2).

Using XFM, we have shown for the first time the extensive accumulation of FADDI-096 within single human alveolar epithelial cells at the millimolar level in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Based on previous in vitro studies in human alveolar epithelial cells (50% effective concentration [EC50], ∼1 mM), the concentrations of FADDI-096 utilized here (5.0 and 10.0 μM) were relatively low in order to avoid cell death and maintain cell morphology for drug localization investigations (29, 30). Both concentrations also allow us to directly compare the accumulation of FADDI-096 between human alveolar epithelial and kidney tubular cells (29, 35). We have previously shown that exposing A549 cells to colistin and polymyxin B led to the activation of caspases, mitochondrial damage (e.g., loss of membrane potential, reactive oxygen species [ROS] production, and loss of filamentous morphology), and ultimately apoptotic death (29). Similar dose- and time-dependent toxicity in renal tubular cells was observed in vitro and in vivo (31, 35, 36). In the present study, our observations of concentration- and time-dependent accumulation of FADDI-096 in A549 cells are in agreement with the literature. The average concentrations of FADDI-096 in A549 cells following 1 and 4 h of exposure to 10.0 μM FADDI-096 were ∼158-fold (1.58 ± 0.11 mM) and ∼225-fold (2.25 ± 0.09 mM) higher than the extracellular concentration at the corresponding time points (Fig. 1D; see also Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). However, the increase in concentration after this time point was less dramatic, with a 24-h concentration of 2.46 ± 0.07 mM. Although the average intracellular concentration achieved with the 5.0 μM treatment at each time point was considerably lower than those with 10 μM treatment, a similar pattern in the accumulation was evident over 24 h. These results demonstrated the rapid absorption and accumulation of polymyxins in human lung epithelial cells and provide important information for the optimization of inhaled polymyxins for lung infections, considering the concentration- and time-dependent killing of bacteria by polymyxins (37, 38).

The rapid absorption and accumulation of polymyxins in human alveolar epithelial cells described above supports our recent pharmacokinetic findings that showed a 7-fold longer terminal half-life of colistin in ELF compared to that in plasma (4.2 h versus 0.57 h) following a single inhaled dose of colistin (5.28 mg/kg) in neutropenic lung-infected mice (24). In that study, the PK modeling results suggested that following rapid absorption of colistin into plasma, a portion was retained in the lungs, which was subsequently slowly released into systemic circulation. The extraordinarily high accumulation of the polymyxin probe within A549 cells may explain the reported adverse effects associated with lung delivery in patients (21, 27, 28). Notably, the accumulation of the polymyxin probe within A549 cells (e.g., ∼225-fold increase at 4 h treated with 10.0 μM) was substantially lower than its accumulation in single human kidney tubular HK-2 cells (∼1,930- to 4,760-fold greater) under the same conditions (35). This difference might be due to the expression of two key membrane transporters (i.e., megalin and oligopeptide transporter 2 [PEPT2]) that are involved in the cellular uptake of polymyxins in renal tubular cells (39–41). Furthermore, the substantially higher accumulation in human kidney (HK-2) cells also explains the significantly higher toxicity of polymyxin B (EC50, 0.35 mM) (42) compared to A549 cells (EC50, 1.74 mM) (29). Overall, our results support administering the polymyxins directly to the lungs in order to minimize potential nephrotoxicity. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the PK/PD/TD relationship of inhaled polymyxins in patients.

Using immunostaining and confocal microscopy, we previously showed that in A549 cells polymyxin B colocalized with early endosomes, lysosomes, ubiquitin, and especially mitochondria (30). Those results are in agreement with activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in A549 cells by polymyxins (29), as well as with the substantial accumulation reported here. Furthermore, accumulation of the polymyxin probe in the nuclear region is consistent with our recent transcriptomic data from A549 cells showing the activation of genes associated with DNA damage repair and arrest of the cell cycle in response to polymyxin treatment (43).

Our XFM results showed that the treatment with FADDI-096 did not change the intracellular concentrations of phosphorus, potassium, iron, or chloride. However, unlike in human kidney tubular HK-2 cells (31), a significant increase in the intracellular zinc concentration was evident in a concentration- and time-dependent manner following treatments with the polymyxin probe (Fig. 3A). The intracellular concentrations of zinc in human alveolar epithelial cells in the present study are consistent with those in several other types of cells in the literature (44, 45). In the respiratory tract, zinc plays key roles as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent, an essential component of various proteins involved in DNA synthesis and repair, in membrane stabilization, and in cellular growth (46, 47). The increased intracellular zinc concentration in response to the treatment with FADDI-096 very likely represents a protective response to the oxidative stress and DNA damage (48) caused by polymyxins. The tumor suppressor protein p53 has an important role in DNA repair, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis, and its binding to specific DNA-binding domains can transcriptionally activate downstream processes of DNA repair (49, 50). The DNA-binding region of this protein contains zinc, and an increased cellular concentration of zinc in FADDI-096-treated cells might contribute to repair of the damaged DNA caused by polymyxins (51). Furthermore, the role of zinc in cell death decision and apoptosis cannot be ruled out due its pleotropic nature (52). The alterations in homeostasis of intracellular zinc concentrations suggest the activation of pathways for cellular toxicities and their protective feedbacks following FADDI-096 treatment. Moreover, the significantly increased intracellular concentrations of calcium in the FADDI-096-treated cells compared to their untreated controls (Fig. 4B) suggest the triggering of apoptotic processes in A549 cells. Collectively, our findings on the significantly increased concentrations of polymyxin probe, zinc, and calcium in A549 cells support the current literature on oxidative stress, DNA damage, and cell cycle perturbation caused by polymyxins (31, 43).

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to quantify the intracellular accumulation and disposition of polymyxins in single lung epithelial cells. It provides key mechanistic insights into polymyxin-induced pulmonary toxicity, and further systems pharmacology studies are required to optimize their inhalation therapy in the clinic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatments.

Human lung epithelial cells (A549 cells, ATCC CCL-185) were employed to determine the intracellular disposition of polymyxins (29). In brief, cells were grown and subcultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). A549 cells (1 × 105 cells/ml) were seeded on sterile silicon nitride windows (Silson, Blisworth, UK) in 12-well plates in the supplemented DMEM at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 until 70% confluence. Cells were then treated with 5.0 and 10.0 μM a dual-modality iodine-labeled fluorescent polymyxin probe, FADDI-096 (32, 35, 53), in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS for 1, 4, and 24 h. After treatment, cells were washed and fixed with a high-purity solution of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). After air drying inside a biosafety cabinet, windows were used for XFM imaging and confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence imaging with FADDI-096.

The design and synthesis of the FADDI-096 peptide has been described in a previous report (35). Confocal fluorescence images of A549 cells on silicon nitride windows for the controls (no treatment) and samples treated with FADDI-096 were acquired using a Nikon inverted C1 confocal microscope equipped with a 405-nm laser and Plan Fluor 10× (numerical aperture [NA], 0.3) air objective (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The z-stacks were acquired, and a maximum intensity projection was produced.

Application of XFM for elemental mapping.

The elemental contents in A549 cells were determined using the XFM beamline at the Australian Synchrotron (54). An incident X-ray beam of 10.5 keV was used to scan the cells on silicon nitride windows; this energy was chosen to induce K-shell ionization of elements with atomic numbers below 30 (Z ≤ Zn). The X-ray fluorescence was detected by a silicon drift diode detector (Vortex; SII NanoTechnology, CA, USA). The three-dimensional data sets (x, y, energy) were generated for elemental mapping using the MAPS software suite (v1.6.5) (54, 55). K emission lines were analyzed for Na, Mg, Al, Si, P, S, Cl, Ar, K, Ca, Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn, whereas the L emission line was applied for iodine. The thin-film standards SRM-1832 and SRM-18323 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD) were employed for absolute calibration of areal densities (μg/cm2). First, pure FADDI-096 solution was tested for fluorescence and XFM imaging. Both high-resolution (scan area of 50 × 50 μm2) and low-resolution (scan area of 1,002 × 1,002 μm2) imaging of A549 cells treated with and without FADDI-096 were conducted to investigate the spatial disposition and determine the drug concentration per cell, respectively. For analysis of cell images, the fluorescence signal of zinc from XFM imaging was employed to segment the cells. Briefly, the binary converted images were used to segment the individual cells by employing functions in ImageJ (NIH, USA) such as Watershed (56, 57). The cell sizes were fixed from 100 to 500 μm2, and the generated overlay from zinc was employed for determination of elements for each treatment. After cell segmentation of XFM images, the quantity of elements per area was determined as an average reading (ng/cm2). The number of segmented cells for each treatment was at least 189. For FADDI-096, the resulting quantity of iodine was employed to determine the equivalent mole of FADDI-096 per cell. Molecular weights and an average cell volume of 2,000 μm3 were employed for determination of the intracellular concentrations of the polymyxin probe and zinc (58). Details for calculations of the intracellular concentrations are provided in the supplemental material. Intracellular concentrations are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey’s test (P < 0.05), and Pearson’s correlation were performed using Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Monash Micro Imaging (MMI), Monash University, Australia. Part of this research was undertaken on the X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) beamline at the Australian Synchrotron (part of ANSTO).

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants R01 AI132681 and R01 AI146160) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; grant APP1104581). J.L. is an NHMRC Principal Research Fellow and T.V. is an NHMRC Industry Career Development Fellow.

We have no conflicts to declare.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). 2018. Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (GLASS) report: early implementation 2017–2018. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahern S, Tacey M, Esler M, Oldroyd J, Dean J, Bell B. 2017. The Australian cystic fibrosis data registry annual report 2015. Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK, Jr, Bradley J, Guidos RJ, Jones RN, Murray BE, Bonomo RA, Gilbert D, Infectious Diseases Society of America.. 2013. 10 × ’20 progress—development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 56:1685–1694. 10.1093/cid/cit152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theuretzbacher U, Gottwalt S, Beyer P, Butler M, Czaplewski L, Lienhardt C, Moja L, Paul M, Paulin S, Rex JH, Silver LL, Spigelman M, Thwaites GE, Paccaud JP, Harbarth S. 2019. Analysis of the clinical antibacterial and antituberculosis pipeline. Lancet Infect Dis 19:e40–e50. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theuretzbacher U, Outterson K, Engel A, Karlen A. 2020. The global preclinical antibacterial pipeline. Nat Rev Microbiol 18:275–285. 10.1038/s41579-019-0288-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassamali Z, Jain R, Danziger LH. 2015. An update on the arsenal for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infections: polymyxin antibiotics. Int J Infect Dis 30:125–132. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, Paterson DL, Shoham S, Jacob J, Silveira FP, Forrest A, Nation RL. 2011. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3284–3294. 10.1128/AAC.01733-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandri AM, Landersdorfer CB, Jacob J, Boniatti MM, Dalarosa MG, Falci DR, Behle TF, Bordinhao RC, Wang J, Forrest A, Nation RL, Li J, Zavascki AP. 2013. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients: implications for selection of dosage regimens. Clin Infect Dis 57:524–531. 10.1093/cid/cit334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zavascki AP, Goldani LZ, Li J, Nation RL. 2007. Polymyxin B for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pathogens: a critical review. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:1206–1215. 10.1093/jac/dkm357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoniu SA, Cojocaru I. 2012. Inhaled colistin for lower respiratory tract infections. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 9:333–342. 10.1517/17425247.2012.660480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yapa SW, Li J, Patel K, Wilson JW, Dooley MJ, George J, Clark D, Poole S, Williams E, Porter CJ, Nation RL, McIntosh MP. 2014. Pulmonary and systemic pharmacokinetics of inhaled and intravenous colistin methanesulfonate in cystic fibrosis patients: targeting advantage of inhalational administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2570–2579. 10.1128/AAC.01705-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landersdorfer CB, Wang J, Wirth V, Chen K, Kaye KS, Tsuji BT, Li J, Nation RL. 2018. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of systemically administered polymyxin B against Klebsiella pneumoniae in mouse thigh and lung infection models. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:462–468. 10.1093/jac/dkx409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheah SE, Wang J, Nguyen VT, Turnidge JD, Li J, Nation RL. 2015. New pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of systemically administered colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in mouse thigh and lung infection models: smaller response in lung infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:3291–3297. 10.1093/jac/dkv267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pogue JM, Lee J, Marchaim D, Yee V, Zhao JJ, Chopra T, Lephart P, Kaye KS. 2011. Incidence of and risk factors for colistin-associated nephrotoxicity in a large academic health system. Clin Infect Dis 53:879–884. 10.1093/cid/cir611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vattimo MDFF, Watanabe M, da Fonseca CD, Neiva LBDM, Pessoa EA, Borges FT. 2016. Polymyxin B nephrotoxicity: from organ to cell damage. PLoS One 11:e0161057. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubin CJ, Ellman TM, Phadke V, Haynes LJ, Calfee DP, Yin MT. 2012. Incidence and predictors of acute kidney injury associated with intravenous polymyxin B therapy. J Infect 65:80–87. 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z, Cao Y, Yi L, Liu JH, Yang Q. 2019. Emergent polymyxin resistance: end of an era? Open Forum Infect Dis 66:ofz368. 10.1093/ofid/ofz368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boisson M, Jacobs M, Gregoire N, Gobin P, Marchand S, Couet W, Mimoz O. 2014. Comparison of intrapulmonary and systemic pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) and colistin after aerosol delivery and intravenous administration of CMS in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7331–7339. 10.1128/AAC.03510-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naesens R, Vlieghe E, Verbrugghe W, Jorens P, Ieven M. 2011. A retrospective observational study on the efficacy of colistin by inhalation as compared to parenteral administration for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia associated with multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Infect Dis 11:317. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodson ME, Gallagher CG, Govan JR. 2002. A randomised clinical trial of nebulised tobramycin or colistin in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 20:658–664. 10.1183/09031936.02.00248102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Athanassa ZE, Markantonis SL, Fousteri MZ, Myrianthefs PM, Boutzouka EG, Tsakris A, Baltopoulos GJ. 2012. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled colistimethate sodium (CMS) in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 38:1779–1786. 10.1007/s00134-012-2628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YW, Zhou Q, Onufrak NJ, Wirth V, Chen K, Wang J, Forrest A, Chan HK, Li J. 2017. Aerosolized polymyxin B for treatment of respiratory tract infections: determination of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic indices for aerosolized polymyxin B against pseudomonas aeruginosa in a mouse lung infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00211-17. 10.1128/AAC.00211-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YW, Zhou QT, Cheah SE, Zhao J, Chen K, Wang J, Chan HK, Li J. 2017. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of pulmonary delivery of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a mouse lung infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02025-16. 10.1128/AAC.02025-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westerman EM, De Boer AH, Le Brun PP, Touw DJ, Roldaan AC, Frijlink HW, Heijerman HG. 2007. Dry powder inhalation of colistin in cystic fibrosis patients: a single dose pilot study. J Cyst Fibros 6:284–292. 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westerman EM, Le BP, Touw DJ, Frijlink HW, Heijerman HGM. 2004. Effect of nebulized colistin sulphate and colistin sulphomethate on lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 58:113–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham S, Prasad A, Collyer L, Carr S, Lynn IB, Wallis C. 2001. Bronchoconstriction following nebulised colistin in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 84:432–433. 10.1136/adc.84.5.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira GH, Muller PR, Levin AS. 2007. Salvage treatment of pneumonia and initial treatment of tracheobronchitis caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli with inhaled polymyxin B. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 58:235–240. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed MU, Velkov T, Lin YW, Yun B, Nowell CJ, Zhou F, Zhou QT, Chan K, Azad MAK, Li J. 2017. Potential toxicity of polymyxins in human lung epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02690-16. 10.1128/AAC.02690-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed MU, Velkov T, Zhou QT, Fulcher AJ, Callaghan J, Zhou F, Chan K, Azad MAK, Li J. 2019. Intracellular localization of polymyxins in human alveolar epithelial cells. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:48–57. 10.1093/jac/dky409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azad MA, Akter J, Rogers KL, Nation RL, Velkov T, Li J. 2015. Major pathways of polymyxin-induced apoptosis in rat kidney proximal tubular cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2136–2143. 10.1128/AAC.04869-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yun B, Azad MAK, Nowell CJ, Nation RL, Thompson PE, Roberts KD, Velkov T, Li J. 2015. Cellular uptake and localization of polymyxins in renal tubular cells using rationally designed fluorescent probes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:7489–7496. 10.1128/AAC.01216-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velkov T, Abdul Rahim N, Zhou QT, Chan HK, Li J. 2015. Inhaled anti-infective chemotherapy for respiratory tract infections: successes, challenges and the road ahead. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 85:65–82. 10.1016/j.addr.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang JZ, Bryce NS, Lanzirotti A, Chen CKJ, Paterson D, de Jonge MD, Howard DL, Hambley TW. 2012. Getting to the core of platinum drug bio-distributions: the penetration of anti-cancer platinum complexes into spheroid tumour models. Metallomics 4:1209–1217. 10.1039/c2mt20168b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azad MAK, Roberts KD, Yu HH, Liu B, Schofield AV, James SA, Howard DL, Nation RL, Rogers K, de Jonge MD, Thompson PE, Fu J, Velkov T, Li J. 2015. Significant accumulation of polymyxin in single renal tubular cells: a medicinal chemistry and triple correlative microscopy approach. Anal Chem 87:1590–1595. 10.1021/ac504516k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallace SJ, Li J, Nation RL, Rayner CR, Taylor D, Middleton D, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Turnidge JD. 2008. Subacute toxicity of colistin methanesulfonate in rats: comparison of various intravenous dosage regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1159–1161. 10.1128/AAC.01101-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velkov T, Roberts KD, Nation RL, Thompson PE, Li J. 2013. Pharmacology of polymyxins: new insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol 8:711–724. 10.2217/fmb.13.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valcke Y, Pauwels R, Van der Straeten M. 1990. Pharmacokinetics of antibiotics in the lungs. Eur Respir J 3:715–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Balamuthusamy S, Simon EE, Batuman V. 2008. Silencing megalin and cubilin genes inhibits myeloma light chain endocytosis and ameliorates toxicity in human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295:F82–F90. 10.1152/ajprenal.00091.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu XX, Chan T, Xu CH, Zhu L, Zhou QT, Roberts KD, Chan HK, Li J, Zhou FF. 2016. Human oligopeptide transporter 2 (PEPT2) mediates cellular uptake of polymyxins. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:403–412. 10.1093/jac/dkv340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki T, Yamaguchi H, Ogura J, Kobayashi M, Yamada T, Iseki K. 2013. Megalin contributes to kidney accumulation and nephrotoxicity of colistin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:6319–6324. 10.1128/AAC.00254-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azad MA, Finnin BA, Poudyal A, Davis K, Li J, Hill PA, Nation RL, Velkov T, Li J. 2013. Polymyxin B induces apoptosis in kidney proximal tubular cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4329–4335. 10.1128/AAC.02587-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azad MAK, Li M, Zhu Y, Yu HH, Velkov T, Li J. 2019. Transcriptomic analysis reveals perturbations of cellular signalling networks in human lung epithelial cells due to polymyxin treatment. VIIN Young Investigator Symposium, poster P-8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maret W. 2015. Analyzing free zinc(II) ion concentrations in cell biology with fluorescent chelating molecules. Metallomics 7:202–211. 10.1039/c4mt00230j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciccotosto GD, James SA, Altissimo M, Paterson D, Vogt S, Lai B, de Jonge MD, Howard DL, Bush AI, Cappai R. 2014. Quantitation and localization of intracellular redox active metals by X-ray fluorescence microscopy in cortical neurons derived from APP and APLP2 knockout tissue. Metallomics 6:1894–1904. 10.1039/c4mt00176a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho E, Courtemanche C, Ames BN. 2003. Zinc deficiency induces oxidative DNA damage and increases p53 expression in human lung fibroblasts. J Nutr 133:2543–2548. 10.1093/jn/133.8.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho E. 2004. Zinc deficiency, DNA damage and cancer risk. J Nutr Biochem 15:572–578. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.St Croix CM, Leelavaninchkul K, Watkins SC, Kagan VE, Pitt BR. 2005. Nitric oxide and zinc homeostasis in acute lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2:236–242. 10.1513/pats.200501-007AC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho E, Ames BN. 2002. Low intracellular zinc induces oxidative DNA damage, disrupts p53, NFκB, and AP1 DNA binding, and affects DNA repair in a rat glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:16770–16775. 10.1073/pnas.222679399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lane DP. 1992. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature 358:15–16. 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yun B, Zhang T, Azad MAK, Wang J, Nowell CJ, Kalitsis P, Velkov T, Hudson DF, Li J. 2018. Polymyxin B causes DNA damage in HK-2 cells and mice. Arch Toxicol 92:2259–2271. 10.1007/s00204-018-2192-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chimienti F, Aouffen M, Favier A, Seve M. 2003. Zinc homeostasis-regulating proteins: new drug targets for triggering cell fate. Curr Drug Targets 4:323–338. 10.2174/1389450033491082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deris ZZ, Swarbrick JD, Roberts KD, Azad MA, Akter J, Horne AS, Nation RL, Rogers KL, Thompson PE, Velkov T, Li J. 2014. Probing the penetration of antimicrobial polymyxin lipopeptides into Gram-negative bacteria. Bioconjug Chem 25:750–760. 10.1021/bc500094d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Howard DL, de Jonge MD, Afshar N, Ryan CG, Kirkham R, Reinhardt J, Kewish CM, McKinlay J, Walsh A, Divitcos J, Basten N, Adamson L, Fiala T, Sammut L, Paterson DJ. 2020. The XFM beamline at the Australian Synchrotron. J Synchrotron Radiat 27:1447–1458. 10.1107/S1600577520010152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vogt S. 2003. MAPS: a set of software tools for analysis and visualization of 3D X-ray fluorescence data sets. J Phys IV France 104:635–638. 10.1051/jp4:20030160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.James SA, Feltis BN, de Jonge MD, Sridhar M, Kimpton JA, Altissimo M, Mayo S, Zheng CX, Hastings A, Howard DL, Paterson DJ, Wright PFA, Moorhead GF, Turney TW, Fu J. 2013. Quantification of ZnO nanoparticle uptake, distribution, and dissolution within individual human macrophages. ACS Nano 7:10621–10635. 10.1021/nn403118u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frame KK, Hu WS. 1990. Cell-volume measurement as an estimation of mammalian-cell biomass. Biotechnol Bioeng 36:191–197. 10.1002/bit.260360211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.