Abstract

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) and community-engaged research have been established in the past 25 years as valued research approaches within health education, public health, and other health and social sciences for their effectiveness in reducing inequities. While early literature focused on partnering principles and processes, within the past decade, individual studies, as well as systematic reviews, have increasingly documented outcomes in community support and empowerment, sustained partnerships, healthier behaviors, policy changes, and health improvements. Despite enhanced focus on research and health outcomes, the science lags behind the practice. CBPR partnering pathways that result in outcomes remain little understood, with few studies documenting best practices. Since 2006, the University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research with the University of Washington’s Indigenous Wellness Research Institute and partners across the country has engaged in targeted investigations to fill this gap in the science. Our inquiry, spanning three stages of National Institutes of Health funding, has sought to identify which partnering practices, under which contexts and conditions, have capacity to contribute to health, research, and community outcomes. This article presents the research design of our current grant, Engage for Equity, including its history, social justice principles, theoretical bases, measures, intervention tools and resources, and preliminary findings about collective empowerment as our middle range theory of change. We end with lessons learned and recommendations for partnerships to engage in collective reflexive practice to strengthen internal power-sharing and capacity to reach health and social equity outcomes.

Keywords: community–academic partnerships, community-based participatory research, community-engaged research, measures, tools, resources, participatory action research

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) and community-engaged research (CEnR) have established themselves in the past 25 years as valued research approaches within health education and other health and social science disciplines for their effectiveness in reducing inequities (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013; Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel, & Minkler, 2018). CBPR, as the most recognized form of health-focused CEnR, has sought to integrate community partners throughout research processes, aiming to prevent stereotyping, stigmatizing, or other research practices that have historically harmed communities (Tuck & Yang, 2012). CBPR is committed to principles of colearning and health equity actions (Israel et al., 2013; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998), with goals to equalize power between researchers and researched (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Gaventa & Cornwall, 2015). CBPR has drawn from the Global South tradition of activist participatory research from the 1970s (Wallerstein & Duran, 2018), and from Brazilian Paulo Freire’s praxis-based empowerment education, recognizing “expertise in the world of practice, beyond academia” (Freire, 1970; Hall, Tandon, & Tremblay, 2015). Praxis, or reflexive practice, means cycles of theory and practice, such that research results and theorizing lead to transformative actions, followed by continuous listening/dialogue/action/reflection (Wallerstein & Auerbach, 2004).

Early attention to CEnR and CBPR principles and practices has turned increasingly to outcomes, including accelerated publication of systematic reviews identifying changes in support networks, empowerment, sustainable partnerships, and health status (Anderson et al., 2015; Drahota et al., 2016; O’Mara-Eves et al., 2015). A new scoping review (Ortiz et al., 2020) identified 100 English-language reviews of distinct outcomes and populations since the groundbreaking Agency for Healthcare Research Quality 2004 review (Viswanathan et al., 2004). CBPR policy impacts on health have been well-documented (Cacari-Stone, Minkler, Freudenberg, & Themba, 2018; Minkler, Garcia, Rubin, & Wallerstein, 2012), and seen as equally important to partnership success as specific grant outcomes (Devia et al., 2017; Jagosh et al., 2012). Despite greater focus on outcomes, the science regarding effective CBPR lags practice, particularly how best to understand power-sharing practices that create pathways toward outcomes (Wallerstein, Muhammad, et al., 2019).

Since 2006, the University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research (UNM-CPR), with University of Washington’s Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (UW-IWRI) and partners across the country, has engaged in a targeted investigation to fill this gap in science and practice of CBPR. Our inquiry seeks to identify which partnering practices, under which contexts and conditions, contribute to research, community, and health equity outcomes. Our investigation has spanned three National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding stages, first identifying a CBPR conceptual model and measures of partnering practices and outcomes, next surveying partnerships across the country and conducting case studies, and currently, testing intervention collective-reflection processes and tools to strengthen partnering and societal equity outcomes. Our national team has also sought to understand how to achieve equitable partnering, through reflection on power across positionalities of hierarchy across university–community structures, funding streams, and societal inequities.

This article presents the design of our third-stage National Institute of Nursing Research–funded grant, Engage for Equity (E2): its history, aims, foundational theory, instruments, intervention tools, and resources. It complements two other articles in this Special Collection, one on E2 Tools and one on Trust. We end with learnings and recommendations related to collective-reflection practice and outcomes.

Background to E2

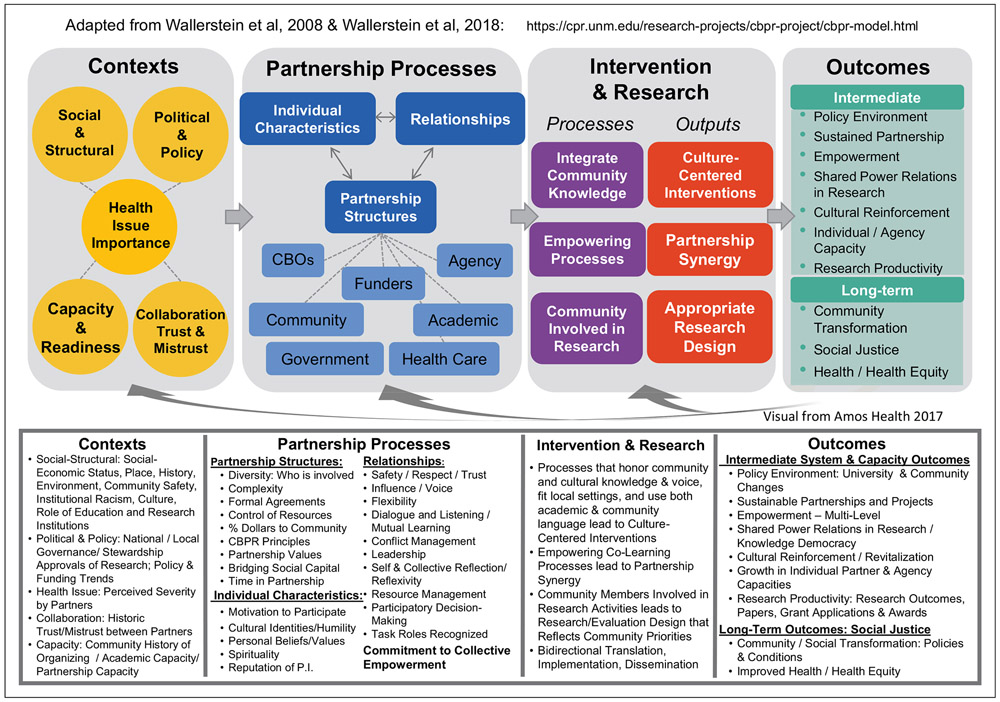

In 2006, UNM-CPR received pilot NIMHD funding, through the Native American Centers for Health mechanism to partner with UW-IWRI for an exploratory study of CBPR. With guidance from a think tank of national academic and community CBPR experts and community consultations, we produced a CBPR conceptual model (Belone et al., 2016; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010; Wallerstein et al., 2008) with four domains (see Figure 1): contexts (i.e., policies, historic trust/mistrust, community capacities); partnering processes (structural, individual, and relational dynamics); intervention and research designs as outputs of shared decision making; and CBPR, capacity, and health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Community-based participatory research conceptual model.

Note. CBOs = community-based organizations; CBPR = community-based participatory research; P.I. = principal investigator.

The mixed-methods Research for Improved Health (RIH) study followed (2009-2013), with the addition of the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center as principal investigator (PI; Lucero et al., 2018). UW led two Internet surveys of federally funded partnerships: a key informant survey (KIS) for the PIs requesting factual information, and a community engagement survey (CES) for academic and community partners on perceptions of partnering processes and outcomes using existing and newly created scales mapped onto the CBPR model. Based on the data from surveys of 200 partnerships and 450 partners in 2009, we validated scale psychometrics (Oetzel et al., 2015), analyzed associations between ~25 promising practices and outcomes (Duran et al., 2019; Oetzel, Duran, et al., 2018; Wallerstein, Oetzel, et al., 2019), and identified relational and structural pathways toward outcomes (Oetzel, Wallerstein, et al., 2018). Seven case studies, led by UNM, deepened knowledge of contexts, power-sharing, and actions towards social-racial equity (Devia et al., 2017; Wallerstein, Muhammad, et al., 2019).

In Stage 3, E2 (2015-2020) expanded our UNM-CPR and UW partnership to include Community–Campus Partnerships for Health, National Indian Child Welfare Association, Rand Corporation, and University of Waikato. The think tank has continued, meeting almost annually to provide guidance and coparticipate in publications. E2’s specific aims were to refine and implement a second round of partnership surveys and to conduct an intervention trial of collective-reflection tools to strengthen partnership capacity to achieve outcomes. Through surveys, E2 has had the benefit of assessing CEnR practices from across the continuum of engagement in research, from minimal community involvement, to shared leadership and community-driven approaches (CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force, 2011). Through the intervention, we have also extended a challenge to academic and community partners to reflect on their community engagement practices and goals, and to encourage them to move along the continuum toward higher levels of partnership, shared power, and equity outcomes.

Our intervention grounded in reflexive practice has led us as a national team to adopt theory and values from complementary, though distinct, traditions. At the core is Freire’s (1970) emancipatory philosophy, emphasizing cocreation of knowledge and reflection/action cycles toward social justice. Power equity is key to our practice, both in our team and in the field, as we recognize our issues of power and privilege (Muhammad et al., 2015). We have integrated Indigenous theories of multiple ways of knowing through cognitive, physical, spiritual, and embodied knowledge, recognizing the importance of interdependent relationships and community stewardship as healing research and community development practices for future generations (Spiller, Barclay-Kerr, & Panoho, 2015; Tuhiwai Smith, 2012). We draw from culture-centeredness (Dutta, 2007) and cognitive/epistemic justice theory to privilege community meaning-making (Fricker, 2007), knowledge democracy from the Global South (Hall et al., 2015; Santos, 2016), and practice-based knowledge (Green & Glasgow, 2006), holding ourselves accountable to benefit communities. A key commitment is to illuminate our differences, including distinct organizational missions, and to recognize that tensions enable critical dialogue for change. Ultimately, our E2 team seeks to create actionable knowledge to improve CBPR/CEnR and participatory action research science and to translate data into community–academic activism for equity, while being cognizant of community struggles and gifts.

Method

E2 has two phases: (1) refining surveys to deepen understanding of partnering pathways toward outcomes and (2) implementing a collective-reflection intervention to strengthen partnerships. Institutional review board approval is from UNM Health Sciences Center (HRPO#16-098).

Phase 1 Surveys

Using the RIH sampling strategy (Pearson et al., 2015), we identified 384 federally funded CBPR/CEnR projects from four public, online repositories in 2015: NIH/RePORTER (exporter.nih. gov), PCORI Portfolio of Funded Projects (pcori.org), Prevention Research Centers (cdc.gov/prc), and Native American Centers for Health American Indian projects (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-16-297.html). To refine instruments, for the KIS with questions on the facts of the partnership, we retained RIH items on funding, community approvals, research type, trainings conducted for members, and dollars shared with community (Pearson et al., 2015); and added questions on advisory structures, roles of approval bodies and community advisory boards, and stage of partnership to better understand community stewardship by stage (Dickson et al., 2020).

Using RIH psychometrics and insights from our RIH case studies for the CES, we added new scales on community organizing histories, collective reflection about equity, and intervention fit with community culture and knowledge and modified others, for example, influence and community dissemination and policy advocacy within the community involvement in research scale. E2 and think tank members pretested the surveys for readability, length, content, sequence, and usability before they were fielded.

From September 2016 to March 2017, 384 PIs were invited to complete the KIS; seven stated they did not meet criteria. A total of 199 PIs consented to the survey (53% response rate); 13 self-screened out as they did not have community partners who could complete the CES; seven did not complete the survey, leaving 179 projects for analysis. See Dickson et al. (2020) for the analysis of the KIS on diversity of populations, PI and partnership characteristics, factor analysis of scales that promote community stewardship, and analysis of promising practices by partnership stage. To expand our understanding of practices and outcomes within early-stage or pilot partnerships, as potentially different from federally funded partnerships, we surveyed a convenience sample of 36 new partnerships from three training networks1; 86% of PIs responded (n = 31).

The 189 PIs who responded to the KIS were invited to complete the CES, and asked to nominate up to six partners (two academic and four community). From November 2016 to July 2017, CES invitations were sent to 631 participants; 11 were excluded during recruitment, leaving 620, with 429 consenting to the survey (69% response rate). Of this total, 381 surveys were used for CES analysis as they were ≥75% complete. For the new partnerships, 133 CES invitations were sent Summer 2018, with 85 consenting to the survey (64% response rate) and 76 cases meeting our completeness criterion for analysis. Gift cards of $20.00 were sent as incentives in advance of participants receiving their KIS and CES Internet links.

While this article focuses on the design of E2 versus forthcoming results, we have seen that preliminary E2 psychometric and scale structure analyses are consistent with original RIH data (Oetzel et al., 2015; Oetzel, Wallerstein, et al., 2018), and produce seven higher order constructs within the four model domains (Boursaw et al., 2020; see Table 1). One of these higher order constructs, collective empowerment, supports Freirian cycles of reflection/action as our theory of change. Four CES scales comprise collective empowerment: collective reflection, evidence of community fit, shared CBPR values, and influence to effect change; together they contribute to synergy of partner actions towards outcomes. These scales mirror definitions from community empowerment literature, as people participating collectively, with core values for change, critical reflection, and influence centered in their community to gain control and improve quality of their living conditions (Cornell Empowerment Group, 1989).

Table 1.

Higher Order Constructs.

| Higher order constructs | CBPR model domain | Individual scales |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity | Context | Community history, bridging social capital, and partnership capacity |

| Collective empowerment | Partnership processes | Collective reflection/reflexivity, community fit, shared CBPR principles, influence/agency |

| Relationships | Partnership processes | Leadership, conflict resolution, participation, trust |

| Community involvement in research | Intervention and research design | Background/design, interpretation and dissemination, community action |

| Synergy | Intervention and research design | Synergy scale |

| Systems and capacity changes | Intermediate outcomes | Personal and agency capacity, shared power relations, and sustainability |

| Future outcomes | Outcomes | Policy, research, health, and social change |

Note. CBPR = community-based participatory research.

Phase 2 Intervention

E2’s second phase focused on testing participatory reflection/action processes. This involved implementing a randomized clinical trial (RCT) that compared two ways of delivering collective reflection tools: face-to-face workshops versus access to materials on the Web. From the 69 partnerships in our sample whose PI responded they had partners to invite to a workshop and from which more than two partners had filled out the CES survey, we randomized 39 partnerships into the workshop intervention and assigned the remaining 30 to Web-based access. Of the 39 partnerships invited to attend the workshops, 25 accepted. We held three 2-day workshops in Fall 2017, with each workshop hosting eight to nine partnerships. E2 paid for three people per partnership (academic PI, community PI/coordinator, and another) to attend; some partnerships brought others (n = 81).

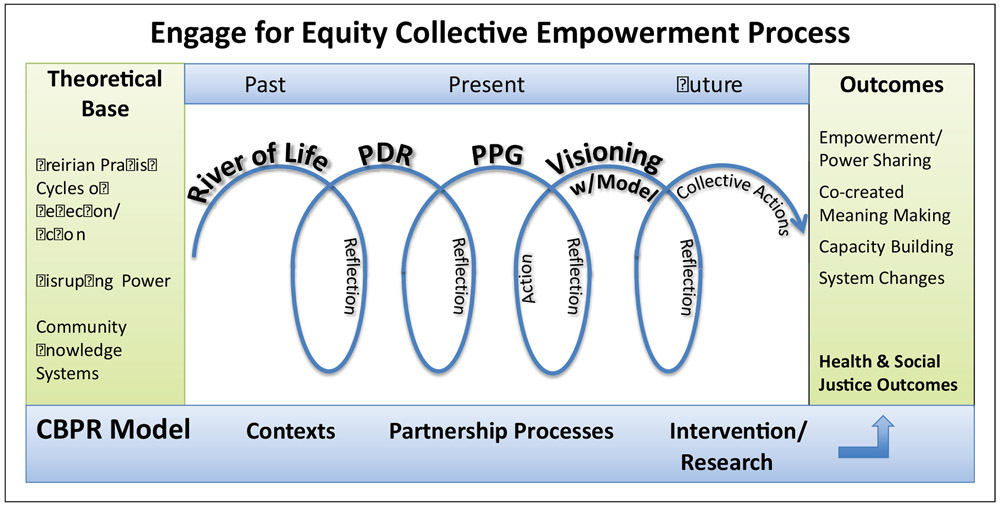

While the tools were developed simultaneously with the measures, both were based on our CBPR conceptual model and underlying theory of change (see Figure 2). In our intervention, we hypothesized that Freirian collective reflection/action processes that honor community knowledge and fit can contribute to collective empowerment processes, which, in turn, can disrupt and transform power relations toward greater equity outcomes within and outside partnerships (Cook, Brandon, Zonouzi, & Thomson, 2019).

Figure 2.

Theory of change: Collective empowerment process.

Note. PDR = partnership data reports; PPG = promising practices guide; CBPR = community-based participatory research.

To facilitate collective reflection/action processes, we adapted or developed four tools: two qualitative (River of Life and CBPR Model as Visioning Tool) and two quantitative (Partnership Data Reports [PDR] containing customized data from each partnership’s CES data, and the Promising Practices Guide [PPG] of national benchmarks). Each tool is meant to deepen a partnership’s understanding of the dynamic relationship among CBPR model domains, with feedback loops from outcomes back to context, partnering, and intervention/research. Trust development may be also supported by use of the tools, with trust seen as cutting across all model domains (Belone et al., 2016), and developed through dynamic processes of respect and mutual participation (Lucero, 2013; see Lucero et al., 2020). These tools and collective reflection/action processes were made available to all partnerships through the website, for both the non–workshop partnerships, as well as those that attended the workshop (see examples of tools in https://engageforequity.org and (Parker et al., 2020).

Workshop.

The workshop intended to create a shared space for teams to apply tools to their projects, to reflect on practices they are doing well and those they want to strengthen, and to encourage them to share tools and collective-reflection learnings with their larger partnerships. Partnerships varied highly by funding source, type of study, community partners, and priority populations (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Project and Partnership Features in Intervention (N = 69).

| Web (n = 30) |

Workshop (n = 39) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of partnerships and projects | n | % | n | % |

| Who initiated the project | ||||

| Community partners | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| Academic partners | 12 | 40 | 17 | 44 |

| Both | 16 | 53 | 20 | 51 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Types of community partners (not mutually exclusive) | ||||

| Patients or caregivers | 14 | 47 | 17 | 44 |

| Health care (staff, providers, clinics, systems) | 24 | 80 | 27 | 69 |

| Community (individuals, associations, organizations) | 26 | 87 | 35 | 90 |

| Government (local, state, federal, tribal agencies) | 16 | 53 | 25 | 64 |

| Policy makers | 12 | 40 | 9 | 23 |

| Nationally based membership associations | 4 | 13 | 6 | 15 |

| Other community partners | 10 | 33 | 11 | 28 |

| Primary study type | ||||

| Pilot | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Descriptive | 3 | 10 | 3 | 8 |

| Intervention | 20 | 67 | 19 | 49 |

| Policy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dissemination and implementation | 3 | 10 | 8 | 21 |

| Some other type | 2 | 7 | 7 | 18 |

| Race, ethnicity, or population group (projects chose all that apply) | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 7 | 23 | 18 | 46 |

| Asian | 6 | 20 | 2 | 5 |

| Black or African American | 17 | 57 | 17 | 44 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| White | 17 | 57 | 14 | 36 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 16 | 53 | 12 | 31 |

| LGBTQ | 3 | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 19 | 63 | 22 | 56 |

| Persons with disabilities | 4 | 13 | 2 | 5 |

| Immigrants | 5 | 17 | 2 | 5 |

| Additional population group(s) | 15 | 50 | 16 | 41 |

| None of the above indicated | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Web (n = 30) |

Workshop (n = 39) |

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Length of project in years | 2.4 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Length of partnership in years (n = 38 for workshop) | 7.9 | 5.1 | 6.1 | 4.9 |

Note: LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer. Pearson’s chi-square tests comparing distributions of categorical variables between Web and workshop groups were statistically nonsignificant (p > .05) in all cases, as were independent-samples t tests comparing mean values for continuous variables between web and workshop groups.

During each workshop, E2 national team and think tank facilitators guided partnership teams through each of the tools, with large group report-backs. For peer-to-peer support, community members and academics met once in separate groups. With the two qualitative tools, team members used markers, crayons, and butcher paper to create their own images. Teams first created their “River of Life,” as a metaphor of their shared journey. This enabled partners to reflect on their context (the CBPR model domain), which included their project’s past (see text in Figure 2) and their successes and barriers along the way. Many teams incorporated community histories and relationships that preceded funding, some going back decades or even a century.

For the visioning exercise, teams adapted and cocreated their own CBPR model as a planning guide for where they wanted to be in the next several years. Each team first brainstormed outcomes they desired (project future), then examined how facilitators and barriers in their social-political environments might affect their pathway toward these (often drawing on their Rivers), and next assessed which partnering practices from the model were going well and/or could be strengthened. Finally, they brainstormed how collaborative practices were influencing their research/intervention actions and how to better integrate cultural knowledge or build community research capacity.

The quantitative PDR tool provided each partnership with the statistical means of their present-day data from each CES scale and some KIS constructs. In some cases, participants attending the workshops had not completed the surveys, and some who had completed the survey (all unidentified) were not present. Whether they had taken the survey or not, team members used the PDR to identify areas for action, aided by key reflection questions, such as “Which practices matter most to you? How do your data fit the priorities you identified in your CBPR visioning exercise?” A checklist of practices enabled team members to note their priorities for future action.

The PPG presented national benchmarks of promising partnering practices associated with outcomes from aggregated survey data from 379 federally funded partnerships: 200 RIH partnerships surveyed from 2009, and 179 E2 partnerships from 2015 (these were partnerships included for analysis from the 199 who initiated the KIS, with 138 partnerships of these completing the CES). Quotes from RIH case studies supplemented the survey data to provide commonsense meanings for each practice. PPG national data provided recommendations for each promising practice and teams reflected on their current practices and plans for the future. Participants were reminded that tools and resources were available on the website to support their use with their partnerships.

Web-Based Intervention.

For the Web-based arm, we constructed the E2 website (engageforequity.org), which in future years will be hosted by Community–Campus Partnerships for Health. The Web delivery system was intended to test whether a minimalist intervention was sufficient for change and to allow for broader dissemination than the more resource-intensive workshops (Glasgow et al., 2014). The website focuses on the model and step-by-step processes for using the four tools, with instructional and storytelling videos, downloadable facilitation guides, and examples. It also offers additional tools, for example, how to develop shared principles. A new Web app (not included in the original RCT) is being beta-tested that allows PIs to register partners to take the Internet-based CES and receive a personalized PDR and an excel spreadsheet of their aggregated data for analysis.

Intervention Evaluation.

Workshop evaluations included daily group debriefs, and a participant survey and team interviews at the end of the workshop. The survey assessed compatibility and complexity of tools, intentions to use and/or adapt, and people’s perceived capacity to meet challenges; interviews explored team reflections and intentions to take learnings back home (see Parker et al., 2020, for survey results, contextualized with some team interviews). Analyses of team interviews are uncovering the importance of facilitation, the facilitation positionality in relation to the projects (i.e., shared race/ethnicity), and the value of the CBPR model as an overarching implementation framework for strengthening collective reflection (Sánchez et al., 2020; see Table 3 for exemplar quotes). During the workshops, facilitators held daily collective reflections on our own learnings, further identifying that we saw teams recommitting to power-sharing and trust development (Lucero et al., 2020) as a result of workshop participatory processes.

Table 3.

Quotes From Intervention Participants.

| Quotes about the importance of collective reflection for action |

|---|

| The community was not involved in the research design. Now that I’ve gone through this training and now that I reflect on how we [the community] were involved in the actual writing of the application, it really highlights to me how disengaged we were in this process of designing the project. |

| I think it was very nice to reflect because often, we get to these places with a lot of different expectations, and then we have to figure out, how can we work through these? I think [in the workshop] we worked through a lot of issues here together, and we realized these are things that we need to work on, and we talked about ways to change those. |

| Is there accountability, how do we look at this partnership from both sides of the coin, academic and community, and do we have a middle ground for that, do we talk about the hard subjects, do we talk about the resources, do we talk about the leadership? You know those are the topics that are very difficult sometimes it takes courage to address. And how we develop the capacity where people feel empowered enough where they will have those discussions, there needs to be more transparency in some things that are happening. There needs to be some things happening that aren’t happening. We need to spend some time, and I go back to the whole reflection piece, we need to look at our partnership structure and see is it effective? If it’s not effective what do we need to do to make it more effective? I know that we’ve developed these relationships over the years and sometimes I think relationships are taken for granted. |

| Having a facilitated discussion by someone who is not afraid to ask difficult questions is different because we don’t have an external facilitator when we meet. |

| So it is nice to have someone externally doing that for us, to help us identify strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities. I think it helped us facilitate some discussions that maybe we’d been dancing around, it gave more pointed conversation. |

To evaluate the impact of the two intervention delivery systems on changes in partnering practices and outcomes, we repeated the CES with the 68 workshop and Web-assigned partnerships (n = 266) from July-September 2018, adding dissemination and implementation questions on partnership use of the website and use/adaptations of the tools (72% response rate). We are currently analyzing these data. In addition, 1-year post interviews are being conducted with a sample of workshop-only, Web-only, and workshop partnerships also accessing the Web to better understand outcomes within each arm. Documentation by Google analytics of 2 years of web use (December 2017-May 2019) found that 59 people from 21 workshop–attendee partnerships used the Web, versus 15 people from 11 partnerships among the exclusive-Web participants. Forthcoming is our analysis of triangulated survey, interview, and Web analytic data to better understand the impact of mode of intervention delivery on changes in practices and outcomes.

In addition to evaluating the RCT, E2 national team members, including many students from different disciplines and with periodic think tank engagement, have regularly reflected on learnings and challenges. We remain committed to the E2 intervention intentions: to identify effective collective-reflection strategies to strengthen challenges to power imbalances within and outside partnerships and to improve health equity outcomes. A national team committee early on drafted our theory/values statement, yet we often find challenges in our practice. For example, despite inclusivity values, during one workshop, a transgender partnership felt marginalized because of noninclusive gender language; we had not been “walking our talk.” During our daily facilitator debrief, we decided to change our introductions to include gender self-identifying pronouns as normal practice. A reinforced learning was the importance of separate academic and community discussions to provide community partners extra support within partnerships.

Our ongoing reflections typically occur through informal dialogue, but we have also applied our tools to our own think tank partnership. During the Fall 2018 think tank meeting, for instance, we conducted our own formal River of Life, leading us to reconfront an internal conflict from 2009. The UNM team had published our CBPR model in a chapter in the 2008 CBPR for Health book, excluding think tank members who had collaborated with input on the model. Though upsetting even 10 years later, we discussed our rebuilding of trust through acknowledging the breach, apologies, and changed practices, such as renewed data-sharing/publication agreements.

Discussion

This article has focused on design of E2, including the unique opportunity to field an RCT. By collecting longitudinal data, we will be analyzing the impacts of the tools we have developed and our approach to building empowerment through collective-reflection. Importantly, our national team, with the think tank, has sought to capture lessons learned throughout our 15-year collaborative process for a broad range of CBPR/CEnR research and practices.

Collective Reflection

We have seen the importance of collective reflection: in our intervention tools and trainings, which promote the Freirian praxis of collective reflection/action cycles, and in contributing to our collective empowerment theory of change based on the CBPR conceptual model. We still believe that other tools and trainings, such as resources to help partnerships choose an equitable decision-making model or combatting racism, may be needed after partners identify areas of strength or concern. We believe that the theoretical grounding and extant literature supports CEnR projects to engage in collective reflection to reap the full benefits of community engagement (O’Mara-Eves et al., 2015).

Mixed-Methods Reflection Tools

We have seen the value of our tools for partners to identify current practices and goals for improving collective actions. The River of Life and Visioning with the CBPR Model have enabled reflection on how their contexts and practices contribute to outcomes; the PDR and PPG have provided quantitative information on their practices and outcomes, and enabled reflection compared to national benchmarks. We recommend partnerships look at tools and survey instruments available on the website (http://engageforequity.org) to identify what might help them strengthen their ability to reach their desired goals.

CBPR Conceptual Model

While the conceptual model carries the CBPR name from the public health literature, we have found its four domains to be generalizable across a continuum of CEnR projects. We have seen the model as both an overall implementation framework to support reflection/action processes within each domain, and a tool for visioning, planning, and evaluation design. Responding to the long text boxes under each of the four domains, some have said it seems too prescriptive or complicated. We have since introduced a double-sided model, with one side showing the comprehensive model and the second side showing the top four-color domains with headings only. This second side helps partnerships create their own adaptation and produce their own process and outcome indicators for pragmatic evaluation use. Its use has been growing worldwide, with model translations now in Swedish, Spanish, Portuguese, and German, being used for both research and nonresearch collaborations (see Wallerstein et al., in press). We recommend partnerships create their own model, starting with desired outcomes, using the visioning guide as a strategic planning effort to reflect on their own their contexts, processes, and future goals (see examples in Parker et al., 2020).

Stronger Theorizing About CBPR

We have sought to understand the role of power within partnerships, similar to many participatory action research projects, such as how external funding hierarchies or academic privilege can stymie power-sharing intentions. Within universities, we have seen hierarchies with students, and we consciously promote safe reflexivity spaces, especially important for students of color or from other marginalized identities, so they can be equal team contributors. Externally, we have observed power dynamics in many spaces: in a multisite case study analysis (Wallerstein, Muhammad, et al., 2019); in survey analyses (Oetzel, Wallerstein, et al., 2018); in workshops, even among committed CEnR partners; and among our think tank, such as recognizing academics benefit from NIH funding more than community partners. Our analysis of pathways identifies “collective empowerment” as a middle-range theory of change (comprising collective reflection, influence, shared values, and community fit), similar to theories of synergy and trust (Jagosh et al., 2015; Khodyakov et al., 2011; Lucero et al., 2020), yet we still need to better understand the journeys of disrupting power hierarchies and power-sharing through community members perceiving their influence and fit of work to community, as well as how to activate and sustain reflection/action cycles. We recommend continued work to help explain the theoretical mechanisms of CBPR and CEnR to achieve improved health and health equity.

Limitations

By focusing on design and theories, this article is limited in not presenting outcome analyses and comprehensive guidance for practice in the field. The design itself has two key limitations. First, the measures are self-report. While the participants are experts in reflecting on their own partnerships and reflection is a key theoretical component of our approach, self-reports have certain biases and may not reflect actual contexts, processes, and outcomes. Unfortunately, it would be cost prohibitive to corroborate self-reports with direct observations. A second limitation is the lack of a true control group for the RCT. Although we have a comparison group for the in-person intervention in terms of the Web-only intervention, we do not know how the interventions have gains compared to “business as usual.”

Conclusion

In sum, our long-term partnership has been rewarding in terms of identifying promising practices, advancing the science of CBPR, and being able to reflect on our own processes. Our E2 products offer potential avenues for other partnerships to enhance their critical reflection of strengths, challenges, and areas for improvement. These theoretical and practical lessons inspire us to continue striving for health and societal equity.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our partners with the E2 study: the University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research, University of Washington’s Indigenous Wellness Research Institute and School of Medicine, Community Campus Partnerships for Health, National Indian Child Welfare Association, University of Waikato, and RAND Corporation; and the national think tank of community and academic CBPR scholars and experts. We are particularly grateful to all the partnerships that responded to our internet surveys and who participated in our E2 workshops and use of the website, and therefore were key to the learnings presented here.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for Engage for Equity: Advancing CBPR Practice Through a Collective Reflection and Measurement Toolkit was from the National Institute of Nursing Research: 1 R01 NR015241. We are thankful for our previous Research for Improved Health NARCH V study (U26IHS300293) and partners that led to Engage for Equity (UNM, UW and the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center), with support from the Indian Health Service in partnership with the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and additional funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, National Cancer Institute, National Center for Research Resources, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. Finally, we appreciate our first pilot NARCH III grant (U26IHS300009), with funding from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The University of Minnesota’s Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leaders, the University of Michigan’s Community Academy, and pilot grants from Morgan State University’s National Institutes of Health Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity grant.

References

- Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner-Brown J, & Krause LK (2015). Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, (6), CD009905. 10.1002/14651858.CD009905.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belone L, Tosa J, Shendo K, Toya A, Straits K, Tafoya G, … Wallerstein N (2016). Community-based participatory research for co-creating interventions with Native communities: A partnership between the University of New Mexico and the Pueblo of Jemez. In Zane N, Bernal G, & Leong FTL (Eds.), Evidence-based psychological practice with ethnic minorities: Culturally informed research and clinical strategies (pp. 199–220). Baltimore, MD: United Book Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boursaw B, Oetzel J, Dickson E, Thein T, Sanchez-Youngman S, Peña J, Parker M, Magarati M, Littledeer L, Duran B, & Wallerstein N (2020). Psychometrics of measures of community-academic research partnership practices and outcomes. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Cacari-Stone L, Minkler M, Freudenberg N, & Themba MN (2018). Community-based participatory research for health equity policy making. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 277–292). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Brandon T, Zonouzi M, & Thomson L (2019). Destabilising equilibriums: Harnessing the power of disruption in participatory action research. Educational Action Research, 27, 379–395. 10.1080/09650792.2019.1618721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Empowerment Group. (1989). Empowerment and family support. Networking Bulletin, 1, 1–23 [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A, & Jewkes R (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science & Medicine, 41, 1667–1676. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devia C, Baker EA, Sanchez-Youngman S, Barnidge E, Golub M, Motton F, … Wallerstein N (2017). Advancing system and policy changes for social and racial justice: Comparing a rural and urban community-based participatory research partnership in the U.S. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 17. 10.1186/s12939-016-0509-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson E, Magarati M, Boursaw B, Oetzel J, Devia C, Ortiz K, & Wallerstein N (2020). Characteristics and practices within research partnerships addressing health and social equity. Nursing Research, 69(1), 51–61. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B, Naaf M, Estabillo JA, Gomez ED, … Aarons GA (2016). Community-academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state ofthe literature and recommendations for future research. The Milbank Quarterly, 94, 163–214. 10.1111/1468-0009.12184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Oetzel J, Magarati M, Parker M, Zhou C, Roubideaux Y, Muhammad M, Pearson C, Belone L, Kastelic SH, & Wallerstein N (2019). Toward health equity: A national study of promising practices in community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(4), 337–352. 10.1353/cpr.2019.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta MJ (2007). Communicating about culture and health: Theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Communication Theory, 17, 304–328. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder & Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker M (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa J, & Cornwall A (2015). Power and knowledge. In Bradbury H (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 465–471). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 10.4135/9781473921290.n46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Fisher L, Strycker LA, Hessler D, Toobert DJ, King DK, & Jacobs T (2014). Minimal intervention needed for change: definition, use, and value for improving health and health research. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4, 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, & Glasgow RE (2006). Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 29, 126–153. 10.1177/0163278705284445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B, Tandon R, & Tremblay C (2015). Strengthening community university research partnerships: Global perspectives. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: University of Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.). (2013). Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, Macaulay AC, Greenhalgh T, Wong G, … Pluye P (2015). A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health, 15, 725. 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, … Greenhalgh T (2012). Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. The Milbank Quarterly, 90, 311–346. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F, Ohito E, Jones A, Lizaola E, & Mango J (2011). An exploration of the effect of community engagement in research on perceived outcomes of partnered mental health services projects. Social Mental Health, 1, 185–199. 10.1177/215686931131613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J (2013). Trust as an ethical construct in community-based participatory research partnerships. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero JE, Boursaw B, Eder M, Greene-Moton E, Wallerstein N, & Oetzel JG (2020). Engage for equity: The role of trust and synergy in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 372–379. 10.1177/1090198120918838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, Kastelic S, Magarati M, Oetzel J, Pearson C, Schulz A, Villegas M, & White Hat ER (2018). Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. Journal of Mixed Methods, 12(1), 55–74. 10.1177/1558689816633309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force. (2011). Principles of community engagement (2nd ed., NIH Publication No. 11-7782). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Garcia AP, Rubin V, & Wallerstein N (2012). Community-based participatory research: A strategy for building healthy communities and promoting health through policy change. Berkeley: PolicyLink and School of Public Health, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL, Avila M, Belone L, & Duran B (2015). Reflections on researcher identity and power: The impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41, 1045–1063. 10.1177/0896920513516025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Duran B, Sussman A, Pearson C, Magarati M, Khodyakov D, & Wallerstein N (2018). Evaluation of CBPR partnerships and outcomes: Lessons and tools from the Research for Improved Health Study. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 237–250). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel JG, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Sanchez-Youngman S, Nguyen T, Woo K, Wang J, Schulz A, Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula J, Israel B, & Alegria M (2018). Impact of participatory health research: A test of the community-based participatory research conceptual model. BioMed Research International, Article ID 7281405. 10.1155/2018/7281405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Zhou C, Duran B, Pearson C, Magarati M, Lucero J, … Villegas M (2015). Establishing the psychometric properties of constructs in a community-based participatory research conceptual model. American Journal of Health Promotion, 29(5), e188–e202. 10.4278/ajhp.130731-QUAN-398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, & Thomas J (2015). The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15, 1–23. 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz K, Nash J, Shea L, Oetzel J, Garoutte J, Sanchez-Youngman S, & Wallerstein N (2020). Partnerships, processes, and outcomes: A health equity–focused scoping meta-review of community-engaged scholarship. Annual Review of Public Health. Advance online publication. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Magarati M, Burgess E, Sanchez-Youngman S, Boursaw B, Heffernan A, Garoutte J, & Koegel P (2020). Engage for equity; Development of community-based participatory research tools. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 359–371. 10.1177/1090198120921188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Duran B, Oetzel J, Margarati M, Villegas M, Lucero J, & Wallerstein N (2015). Research for improved health: Variability and impact of structural characteristics in federally funded community engaged research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 9, 17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez V, Sanchez-Youngman S, Dickson EL, Burgess El., Haozous E, Trickett E, … Wallerstein N (2020). CBPR implementation framework for community-academic partnerships. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos B d. S. (2016). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller C, Barclay-Kerr H, & Panoho J (2015). Wayfinding leadership: Groundbreaking wisdom for developing leaders. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck E, & Yang WK (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tuhiwai Smith L (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, … Whitener L (2004). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence: Summary. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11852/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Auerbach E (2004). Problem-posing at work: popular educator’s guide. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Grass Roots Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Belone L, Burgess E, Dickson E, Gibbs L, Parajon LC, … Silver G (in press). Community based participatory research: Embracing praxis for transformation. In International SAGE handbook for participatory research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100(Suppl. 1), S40–S46. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2018). Theoretical, historical, and practice roots of CBPR. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 17–29). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.). (2018). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Muhammad M, Avila M, Belone L, Lucero J, Noyes E, … Duran B (2019). Power dynamics in community based participatory research: A multi-case study analysis partnering contexts, histories and practices. Health Education & Behavior, 46(1 Suppl.), 19S–32S. 10.1177/1090198119852998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Magarati M, Pearson C, Belone L, … Dutta M (2019). Culture-centeredness in community based participatory research: Its impact on health intervention research. Health Education Research, 34, 372–388 10.1093/her/cyz021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, & Rae R (2008). What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community based participatory research for health: Process to outcomes (2nd ed., pp. 371–392). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]