Abstract

Aim

To assess postoperative complications and control of hormone secretions following pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) performed on multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) patients with duodenopancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (DP-NETs).

Background

The use of PD to treat MEN1 remains controversial, and evaluating the right place of PD in MEN1 disease makes sense.

Methods

Thirty-one MEN1 patients from the Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines MEN1 cohort who underwent PD for DP-NETs between 1971 and 2013 were included. Early and late postoperative complications, secretory control and overall survival were analyzed.

Results

Indication for surgery was: Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (n = 18; 58%), nonfunctioning tumor (n = 9; 29%), insulinoma (n = 2; 7%), VIPoma (n = 1; 3%) and glucagonoma (n = 1; 3%). Mean follow-up was 141 months (range 0–433). Pancreatic fistulas occurred in 5 patients (16.1%), distant metastases in 6 (mean onset of 43 months; range 13–110 months), postoperative diabetes mellitus in 7 (22%), and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in 6 (19%). Five-year overall survival was 93.3% [CI 75.8–98.3] and ten-year overall survival was 89.1% [CI 69.6–96.4]. After a mean follow-up of 151 months (range 0–433), the biochemical cure rate for MEN-1 related gastrinomas was 61%.

Conclusion

In MEN1 patients, pancreatoduodenectomy can be used to control hormone secretions (gastrin, glucagon, VIP) and to remove large NETs. PD was found to control gastrin secretions in about 60% of cases.

Introduction

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is an autosomal dominant hereditary syndrome with a prevalence of 2/100,000 individuals. The disease is triggered by a mutation in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene [1–3]. The most common MEN1 lesions are (in order of frequency) primary hyperparathyroidism, neuroendocrine duodenopancreatic tumors (DP-NETs) and pituitary tumors, neuroendocrine thymic tumors, bronchic tumors, and adrenal tumors.

DP-NETs are the primary cause of MEN1-cancer-related deaths [4–6]. Surgery (pancreatoduodenectomy—PD) is recommended for large, non-functioning tumors (> 2 cm in diameter) located on the head of the pancreas because of the risk of malignant spread [7, 8]. PD may also be indicated in order to control the secretion of glucagonomas, Vipomas and insulinomas. Several authors have concluded that PD is the best option for patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES) because gastrinomas tend to be numerous and located in the duodenum [9–11]. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) can be an efficient, surgery-free means of controlling acid secretion, but surgery is more likely to prevent metastatic spread.

PD is a surgery with significant postoperative mortality [12]. Moreover, though MEN1-related DP-NETs tend to be slow-growing, they are often multiple and scattered throughout the pancreatic gland, meaning that there is a major risk that new tumors will develop in the portion that remains after surgery. The controversy surrounding the use of PD for MEN1 is therefore substantiated, and it seems relevant to evaluate the role of PD in MEN1 disease. The aim of this study was (1) to describe the clinical characteristics and surgical indications for PD in MEN1 patients, (2) to describe surgical complications and survival, and (3) to assess secretory control in functioning tumors with a particular focus on ZES patients.

Methods

Population

Our study population was extracted from the 1400-patient cohort of the Groupe d’étude des Tumeurs Endocrines (GTE). All MEN1 patients who underwent PD for DP-NET between 1971 and 2013 in nine hospitals with high-volume of pancreatic surgery were included in this retrospective study. Patients who underwent a previous pancreatic surgery before PD were excluded. The MEN1 cohort was approved by the Consultative Committee on Treatment of Information in Health Research (CCTIRS) and the National Committee for Data Protection (CNIL). Diagnosis of MEN1 was defined according to the clinical practice guidelines of the GTE [13]. The diagnosis of insulinoma was based on the presence of hypoglycemic symptoms associated with low plasma glucose concentrations and abnormally high serum insulin or C-peptide [14]. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome criteria were the presence of continuous specific clinical symptoms associated with ZES features found on endoscopy, an inability to discontinue high-dose proton pump inhibitors, and at least 2 out of the 4 National Institute of Health (NIH) criteria and a histological confirmation of gastrinoma [15, 16]. A diagnosis of VIPoma was confirmed in patients with the association of watery diarrhea and a high serum vasoactive intestinal peptide level. A diagnosis of glucagonoma was confirmed in patients with glucagonoma syndrome and elevated blood glucagon levels [17, 18]. DP-NETs were defined as nonfunctioning when there were no clinical symptoms of hormonal hypersecretion [8, 19].

Recorded data

The main outcomes of the study were 90-day postoperative mortality and morbidity defined with the Dindo-Clavien classification and humoral secretion control [20]. We also analyzed the onset of metastases in the 5 years following surgery.

Postoperative mortality included all deaths occurring before hospital discharge or up to 90 days. Morbidity included any complications that appeared before hospital discharge and/or readmission within 90 days. Postoperative pancreatic fistula was defined according to the 2016 criteria of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) [21]. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage and delayed gastric emptying were defined according to the 2007 criteria of ISGPS [22, 23]. Exocrine insufficiency was defined as symptoms such as steatorrhea and weight loss resolving after treatment with pancreatic enzymes. Endocrine insufficiency was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and/or HbA1c > 6.5%, and/or the need to modify diet, take oral medication or insulin to control blood glucose levels.

Humoral secretion control was considered for each type of secreting DP-NET. Insulinoma, glucagonoma, and VIPoma secretions were considered to be cured if the patients had no symptoms and humoral secretions were normal. PPI use was classified into 3 categories: complete withdrawal, prophylactic treatment (e.g. prescribed after PD in order to avoid ulcerations), or maintenance of pre-surgery treatment. ZES was considered clinically cured if the patient had no recurrent symptoms without use of PPIs, probably cured when there were no recurrent symptoms but prophylactic use of PPIs, and biochemically cured when there were normal concentrations of fasting gastrin and/or the secretin stimulation test was negative for gastrin.

The following variables were collected for all patients: date of birth, gender, dates of MEN1 and DP-NET diagnosis, date of PD, DP-NET characteristics at that time, number of duodenopancreatic lesions, presence of lymph nodes, occurrence of distant metastases and the status of the JunD transcription factor.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were described using means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians and ranges when appropriate. Qualitative variables were expressed in percentage. The 90-day mortality rate and complications were also expressed as percentages. Overall survival was defined as the time from surgery to death (all causes). Five-year and ten-year overall survival were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed with STATA 12 statistical software.

Results

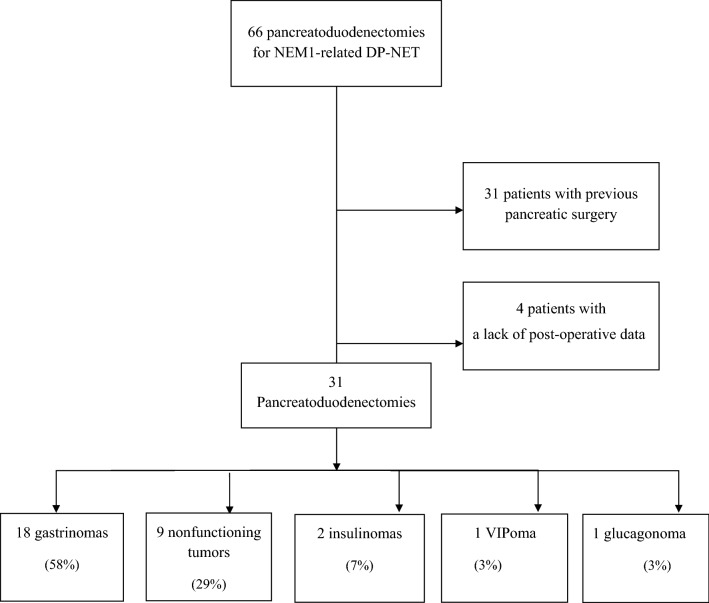

We analyzed 31 MEN1 patients (47% of all PDs in the GTE cohort) who underwent PD for DP-NET (Fig. 1). Trends in demographic data, associated lesions at the time of surgery, results of genetic testing and the main indications for surgery are displayed Table 1. A summary of patient characteristics, tumors, postoperative course, and follow-up are displayed in Table 2. Briefly, among the 31 patients, 18 (58%) underwent PD for ZES, 9 (29%) for a nonfunctioning PNET > 2 cm in size, 2 (7%) for insulinomas, one (3%) for a VIPoma and one (3%) for a glucagonoma. In ZES patients, 12 had surgery to control acid secretion, 5 patients with positive nodal status had surgery to prevent metastatic spread, and in 1 case surgery was done because a large NET was located in the head of the pancreas. Overall morbidity was 26%—16% of these were cases of severe clinically significant morbidity (grade III or more). Five patients (16.1%) developed pancreatic fistulas. Four patients were grade B which two required radiological guided drainage at seventh and eighth postoperative day without reoperation (grade IIIa). One patient was grade C and underwent reoperation at seventh postoperative day (grade IIIb).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Table 1.

Demographic data, lesions at time of surgery and genetic diagnosis

| Until 2000 | 2001 and after | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 13 | (%) | N = 18 | (%) | ||

| Sex ratio Men/total | 7/13 | 54 | 8/18 | 44 | 0.6 |

| Age at MEN1 diagnosis | 43.5 ± 15.1 | 36.9 ± 17.2 | 0.3 | ||

| Age at DP-NET diagnosis | 42.9 ± 14.5 | 42..6 ± 14.9 | 0.9 | ||

| Age at DP-NET surgery | 43. ± 14.4 | 44..4 ± 14.3 | 0.8 | ||

| DP-NET known before MEN1 diagnosis | 5/13 | 38 | 3/18 | 17 | 0.2 |

| pHPT at time of DP-NET surgery | 7/13 | 54 | 13/18 | 72 | 0.4 |

| Pituitary adenoma at time of DP-NET surgery | 1/13 | 8 | 8/18 | 44 | 0.04 |

| Adrenal at time of DP-NET surgery | 2/13 | 15 | 3/18 | 17 | 1 |

| Thymic NET at time of DP-NET surgery | 0/13 | 0 | 0/18 | 0 | 1 |

| Bronchic NET at time of DP-NET surgery | 0/13 | 0 | 0/18 | 0 | 1 |

| Previous gastric surgery | 1/13 | 8 | 0/18 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Index cases | 4/13 | 31 | 1/18 | 5 | 0.1 |

| Genetic tests performed | 10/13 | 77 | 18/18 | 100 | 0.06 |

| Positive MEN1 mutations found | 8/10 | 80 | 16/18 | 89 | 0.6 |

| Indication for ZES | 7/13 | 54 | 11/18 | 61 | 0.7 |

| Indication to control H + secretion among ZES | 7/7 | 100 | 5/11 | 45 | 0.04 |

| Indication for large non-functioning NET | 3/13 | 23 | 6/18 | 33 | 0.7 |

Table 2.

Type of neuroendocrine tumor and follow-up

| No | Age/Sex | Year of surgery | Type of secretion | Location of the largest NET | Size of the largest NET | Post-operative complication | Late complications | Distant Metastasis Delay (months) | Follow-up (months) | Status | Cause of death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63/M | 1971 | ZES | Unknown | Unknown | 54 | Died | Cachexia | ||||

| 2 | 38/F | 1981 | ZES | Unknown | 11 mm | 433 | Died | Unknown | ||||

| 3 | 48/F | 1983 | Insulinoma | Head | 9 mm | 180 | Died | Epidermoid Carcinoma (Lung) | ||||

| 4 | 54/F | 1987 | ZES | Unknown | 11 mm | Mellitus diabetes | 374 | Alive | ||||

| 5 | 39/M | 1991 | VIPoma | Head | 60 mm | Liver | 17 | 78 | Died | Metastasis | ||

| 6 | 31/M | 1992 | ZES | Unknown | 8 mm | Mellitus Diabetes | 167 | Died | Chronic Ethylism | |||

| 7 | 46/M | 1993 | ZES | Duodenum | 4 mm | Delayed gastric emptying | Exocrine Insufficiency | 150 | Died | Thymic Carcinoma | ||

| 8 | 39/F | 1995 | NFT | Head | 35 mm | Liver | 0 | 204 | Alive | |||

| 9 | 60/M | 1996 | ZES | Duodenum | 8 mm | Exocrine Insufficiency | 195 | Alive | ||||

| 10 | 26/M | 1999 | NFT | Head | 60 mm | Mellitus Diabetes | Liver | 26 | 182 | Alive | ||

| 11 | 54/M | 1999 | ZES | Duodenum | 15 mm | Fistula/delayed gastric emptying | Liver | 36 | 180 | Died | Metastasis | |

| 12 | 15/M | 1999 | NFT | Head | 30 mm | 155 | Alive | |||||

| 13 | 59/F | 2000 | Insulinoma | Head | 12 mm | 157 | Alive | |||||

| 14 | 25/M | 2001 | ZES | Duodenum | 7 mm | Fistula/delayed gastric emptying/Haemorrhage | Mellitus Diabetes | Liver | 13 | 198 | Alive | |

| 15 | 62/M | 2002 | ZES | Unknown | Unknown | 178 | Died | Operative* | ||||

| 16 | 40/M | 2003 | NFT | Head | 90 mm | 163 | Alive | |||||

| 17 | 17/M | 2003 | ZES | Duodenum | 10 mm | 70 | Alive | |||||

| 18 | 34/F | 2004 | ZES | Duodenum | 12 mm | 110 | Alive | |||||

| 19 | 48/M | 2005 | ZES | Duodenum | 20 mm | Exocrine Insufficiency | 156 | Alive | ||||

| 20 | 28/F | 2006 | Glucagonoma | Head | 25 mm | Mellitus Diabetes | 114 | Alive | ||||

| 21 | 34/F | 2006 | ZES | Duodenum | 10 mm | 146 | Alive | |||||

| 22 | 66/M | 2006 | NFT | Head | 50 mm | Mellitus Diabetes | Liver | 60 | 86 | Alive | ||

| 23 | 57/F | 2006 | ZES | Duodenum | 23 mm | Mellitus Diabetes | Liver | 110 | 118 | Alive | ||

| 24 | 18/F | 2008 | NFT | Head | 14 mm | Fistula/Delayed gastric emptying | 108 | Alive | ||||

| 25 | 28/F | 2009 | NFT | Head | 25 mm | Exocrine Insufficiency | 90 | Alive | ||||

| 26 | 44/F | 2009 | NFT | Head | > 20 mm | Fistula/Delayed gastric emptying/Haemorrhage | 83 | Alive | ||||

| 27 | 47/F | 2009 | NFT | Head | 25 mm | 44 | Alive | |||||

| 28 | 35/M | 2010 | ZES | Duodenum | Unknown | Haemorrhage | 0 | Died | Operative | |||

| 29 | 30/F | 2011 | ZES | Duodenum | 10 mm | 69 | Alive | |||||

| 30 | 64/F | 2011 | ZES | Unknown | < 20 mm | Exocrine Insufficiency | 84 | Alive | ||||

| 31 | 40/M | 2013 | ZES | Duodenum | 7 mm | Fistula/Delayed gastric emptying | 43 | Alive | ||||

*After surgery for enterocutaneous fistula

Three patients (9.7%) showed a post-PD haemorrhage. Two were grade B with embolization and relaparotomy and one were grade C with death at the fourth postoperative day.

Six patients (19.4%) showed delayed gastric emptying. Seven patients (22%) developed diabetes mellitus and 5 patients (16%) developed pancreatic exocrine insufficiency.

During the mean follow-up period of 141 months (range 0–433), 6 patients developed distant liver metastasis. All distant metastases had a duodenopancreatic origin and occurred after a mean of 43 months (range 13–110) (Table 2). Among patients with metachroneous metastases, PD was indicated for 3 NETs which were > 40 mm and located in the head of the pancreas and for 3 ZES with gastrinomas of the duodenum. Half of these patients had positive nodes. One additional patient had preoperative undiagnosed synchronous liver metastases. The newly discovered metastases were resected during PD, and a 35 mm NET was removed from the head of the pancreas. Two patients underwent surgery for liver metastases, the first at 36 months and the second 96 months after PD. Seven patients (23%; 3 with ZES and with nonfunctioning tumors) developed new tumors in the remnant pancreas, but none had additional pancreatic surgery. Overall, 9 patients died. This included 3 deaths (33%) that were not directly due to MEN1 disease (alcohol, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, sudden and unknown cause) and one case related to MEN1 but not DP-NETs (thymic carcinoma) (Table 2). Two deaths were directly related to DP-NET metastases (6%) following a loss of interaction of the JunD transcription factor. Mean age at death was 58 ± 10.1 years. Five-year overall survival was 93.3% [CI 75.8–98.3] and ten-year survival was 89.1% [CI 69.6–96.4]. During the follow-up all selected patients have not received additional pancreatic resections.

Long-term use of PPIs for ZES patients is shown in Table 3. Eleven patients out 18 (61%) no longer required PPIs for secretion control. Six patients remained on prophylactic PPIs in order to protect the gastroenteroanastomosis from ulcers, and five patients were able to stop taking PPIs completely without secretory complications or abdominal symptoms. Three ZES patients who developed liver metastasis required an antisecretory dose of PPIs, and 4 patients with no metastases were not biochemically cured. One metastatic patient who had been taking PPI for secretion control developed a perforated ulcer when the dosage was reduced. After a mean follow-up of 151 months (range 0–433), the rate of biochemical cured MEN-1 related gastrinomas was 61%.

Table 3.

ZES patients requiring Proton Pump Inhibitors after surgery

| No | Sex | Year of surgery | Positive nodes | Distant metastasis | Antisecretory PPIs * withdrawal | Daily use of PPIs* | Follow-up (months) | Persistent ZES*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 1971 | Yes | No | NA** | NA** | 54 | Yes |

| 2 | F | 1981 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 433 | Unknown |

| 4 | F | 1987 | No | No | Yes | Omeprazole 20 mg | 374 | No |

| 6 | M | 1992 | Unknown | No | Yes | No | 167 | No |

| 7 | M | 1993 | Yes | No | Yes | Omeprazole 20 mg | 150 | No |

| 9 | M | 1996 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 195 | No |

| 11 | M | 1999 | Yes | Yes | No | Omeprazole 80 mg | 180 | Yes |

| 14 | M | 2001 | Yes | Yes | No | Omeprazole 80 mg | 198 | Yes |

| 15 | M | 2002 | Unknown | No | Yes | No | 178 | No |

| 17 | M | 2003 | Yes | No | Yes | Omeprazole 10 mg | 70 | No |

| 18 | F | 2004 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 110 | No |

| 19 | M | 2005 | Yes | No | Yes | Rabeprazole 10 mg | 156 | No |

| 21 | F | 2006 | No | No | Yes | Omeprazole 20 mg | 146 | No |

| 23 | F | 2006 | Unknown | Yes | No | Esomeprazole 160 mg | 118 | Yes |

| 28 | M | 2010 | Yes | No | NA** | NA** | 0.1 | NA** |

| 29 | F | 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 69 | No |

| 30 | F | 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | Lansoprazole 15 mg | 84 | No |

| 31 | M | 2013 | Yes | No | Unknown | Unknown | 43 | Unknown |

*Proton Pump Inhibitor

**Not applicable

***PPIs withdrawal clinically impossible and/or gastrinemia not normalized without IPP

Discussion

The management of patients with MEN1 remains controversial. The significant risk of surgery-related death should be considered when PD is indicated. However, though the growth of DP-NETs tends to be slow, these tumors are the primary cause of MEN1-cancer-related deaths [4, 5, 24]. One of the main aims of this study was to inform the clinical decision-making process, particularly for the care of patients with one or several MEN1-related NET(s) located in the duodenum or in the head of the pancreas. The results of this study showed that the clinical presentation of patients undergoing PD has changed over time. Surgery was indicated most often to control hormone secretions and secondly to remove large NETs. Surgery was often done to control gastrin secretion, and the complications were similar to those observed in other types of pancreatic surgery. (3) Finally, PD appears to be an efficient strategy for controlling gastrin secretion in patients with ZES and no distant metastases.

The study has several limitations. At present, this is the largest study to evaluate PD in MEN1 patients [9–11] but the number of patients remains low with difficulty to draw robust conclusions. The cohort involves a group of patients with a tumor syndrome, which generally involves complex treatment strategies and often more surgeries during follow-up. In this study patients who had already undergone pancreatic surgery were excluded in order to assess the specific role of PD. But during the life MEN1 patients who undergo PD can receive additional pancreatic resections and this might influence the reported outcome. This study covers a very long period (42 years). The clinical presentation of operated patients had changed over time (Table 1). MEN1 is now diagnosed earlier, and more associated MEN1 lesions are recognized at time of surgery. Moreover, cases registered before 1991 were retrospectively reviewed and the older pathological reports lacked some pertinent criteria such as grade, immunostaining or Ki67 index, and the duodenum was not always extensively screened for small or dispersed gastrinomas.

Indications for ZES should theoretically have disappeared with the appearance of PPIs in the 1990s, but this was not the case. The number of patients operated for ZES remained stable because indications for secretion control decreased and indications for cancer cure or prevention increased (Table 1). Indeed, indications versus abstention for non-functioning NETs date back to the 2000s [8]. In contrast, surgery has always been recommended for insulinoma (n = 2), glucagonoma (n = 1) and VIPoma (n = 1), as confirmed in the most recent guidelines [19].

PD theoretically carries a higher risk of fistula in MEN1 patients because of the soft consistency of the pancreatic gland and because the pancreatic duct and biliary tract are thin [24–26]. Present study found a pancreatic fistula rate of 16% and a post-operative mortality of 3% (one death from hemorrhage at the fourth postoperative day). These results are consistent with those of Eshmuminov’s meta-analysis (pancreatic fistula rate of 14.5% in 22,376 patients) [12]. Complications and failure to rescue after pancreatic surgery is correlate with hospital volume [27]. In our study all PD were performed in high volume centers with more than 20 pancreatic resections.

The occurrence of liver metastasis is a major prognostic factor for ZES patients [4, 5, 28]. In our study, 20% of ZES patients developed liver metastases after a mean follow-up of 151 (range 0–433) months, which is much higher than the 3% in Fraker et al. or 0% in Bartsch et al. after a mean follow-up of 104 months [29, 30]. Nevertheless, the probability of metastasis occurrence is likely variable due to the apparent heterogeneous nature of MEN1-related ZES. The NIH group reported the existence of aggressive (14% of cases) and a more common non-aggressive form (86% of cases) of ZES [15]. Patients with non-aggressive forms were found to have increased survival, even those who developed associated metastases. Finally, aggressive tumor growth was associated with significantly shorter survival in comparison with liver metastases without aggressive tumor growth. Five-year survival in patients with aggressive disease was 88% (95% CI 53–98), whereas 100% (95% CI 92–100) of patients with non-aggressive disease with or without metastases were alive at 5 years (p = 0.0012). These observations raise the question of whether PD could be used to prevent metastasis from developing in cases of non-agressive ZES. Unfortunately, there is currently no efficient way to define groups of ZES at a higher risk of death. In our study, five-year and ten-year overall survival was respectively 93.3% [CI 75.8–98.3] and 89.1% [CI 69.6–96.4] with a mean follow-up of 141 months. The negative effect of a JunD-LOI genotype on survival was confirmed in a 2013 study of the whole GTE cohort of 820 patients [31]. In the present study, death was directly related to the metastatic spread of DP-NETs in 2 cases (6%) with a JunD-LOI genotype. JunD-LOI status should therefore potentially be considered when making the decision to operate or not. As far as NFT-NETs are concerned, metastatic status is strongly correlated with the size of the pancreatic tumor, and large NETs have always been found in the pancreatic gland rather than the duodenum [32]. So, as expected, all the metastatic cases in our population harbored NFT-NETs larger than 20 mm.

The biochemical cure rate for the gastrinomas in our series was 61% with a mean follow-up of 151 months (range 0–433). Tonelli et al. and Lopez et al. reported 77% and 54% cure rates, respectively, but with shorter follow-up times [9–11]. Even if it is difficult to statistically compare these results, they all indicate that PD can effectively control ZES-related gastrin secretion in patients with no metastatic disease. On the other hand, stopping PPI treatment may be dangerous, particularly for metastatic patients.

This study on a relatively large cohort of MEN1 patients confirms that PD results in a rate of complications that is typical for pancreatic surgery. PD can be used to control hormone secretions (gastrin, glucagon, VIP), to remove large NETs located on the head of the pancreas and for ZES when there are associated NETs in the pancreatic head or if pathological nodes develop around the duodenum.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brandi ML, Gagel RF, Angeli A, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of MEN type 1 and type 2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5658–5671. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marini F, Falchetti A, Del Monte F, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:38. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2990–3011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito T, Igarashi H, Uehara H, Berna MJ, Jensen RT. Causes of death and prognostic factors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: a prospective study: comparison of 106 MEN1/Zollinger–Ellison syndrome patients with 1613 literature MEN1 patients with or without pancreatic endocrine tumors. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013;92(3):135–181. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182954af1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goudet P, Murat A, Binquet C, et al. Risk factors and causes of death in MEN1 disease. A GTE (Groupe d'Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines) cohort study among 758 patients. World J Surg. 2010;34(2):249–55. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadowski SM, Triponez F. Management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in patients with MEN 1. Gland Surg. 2015;4(1):63–8. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2014.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pieterman CRC, de Laat JM, Twisk JWR, van Leeuwaarde RS, et al. Long-term natural course of small nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in MEN1-results from the Dutch MEN1 Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3795–3805. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Triponez F, Sadowski SM, Pattou F, et al. Long-term Follow-up of MEN1 patients who do not have initial surgery for small ≤2 cm nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, an AFCE and GTE study: Association Francophone de Chirurgie Endocrinienne & Groupe d'Etude des Tumeurs Endocrines. Ann Surg. 2018;268(1):158–164. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonelli F, Fratini G, Nesi G, et al. Pancreatectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related gastrinomas and pancreatic endocrine neoplasias. Ann Surg. 2006;244(1):61–70. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000218073.77254.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez CL, Waldmann J, Fendrich V, et al. Long-term results of surgery for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms in patients with MEN1. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(8):1187–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0828-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez CL, Falconi M, Waldmann J, et al. Partial pancreaticoduodenectomy can provide cure for duodenal gastrinoma associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2013;257(2):308–314. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182536339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eshmuminov D, Schneider M, Clavien, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of post-operative pancreatic fistula rates using the updates 2016 International Study Group pancreatic fistula definition in patients undergoing pancreatic resection with soft and hard pancreatic texture. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20(11):992–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakker RV, Newey PJ, Walls GV, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) Endocrine Soc J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2990–3011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al. Endocrine society. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3):709–728. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83(1):43–83. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000112297.72510.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metz DC, Cadiot G, Poitras P, et al. Diagnosis of Zollinger–Ellison in the era of PPIs. Int J Endocr Oncol. 2017;4(4):167–185. doi: 10.2217/ije-2017-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lévy-Bohbot N, Merle C, Goudet P, et al. Prevalence, characteristics and prognosis of MEN 1-associated glucagonomas, VIPomas, and somatostatinomas: study from the GTE (Groupe des Tumeurs Endocrines) registry. Groupe des Tumeurs Endocrines. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28(11):1075–81. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)95184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couvelard A, Glucagonoma HO. In: Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: practical approach to diagnosis, classification, and therapy. Stefano LR, Fausto S, editors. Switzerland: Springer; 2015. pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Vienna Consens Conf Particip Neuroendocrinol. 2016;103(2):153–171. doi: 10.1159/000443171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clavien PA, Barjun J, Makuuchi M, et al. The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the ISGPS definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after international study group on pancreatic surgery. Surgery. 2017;161(3):584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142(1):20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wente MN, Bassi C, Büchler M, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2007;142(5):761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jilesen AP, van Eijck CH, Hof KH, et al. Postoperative complications, in-hospital mortality and 5-year survival after surgical resection for patients with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2016;40(3):729–748. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3328-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farges O, Bendersky N, Truant S, et al. The theory and practice of pancreatic surgery in France. Ann Surg. 2017;266:797–804. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atema JJ, Jilesen AP, Busch OR, et al. Pancreatic fistulae after pancreatic resections for neuroendocrine tumours compared with resections for other lesions. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17(1):38–45. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Amrani M, Clement G, Truant S, et al. Failure-to-rescue in patients undergoing pancreatectomu: is hospital volume a standard for quality improvement programs? Nationwide analysis of 12,333 patients. Ann Surg. 2018;268(5):799–807. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cadiot G, Vuagnat A, Doukhan I, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Groupe d'Etude des Néoplasies Endocriniennes Multiples (GENEM and groupe de Recherche et d'Etude du Syndrome de Zollinger–Ellison (GRESZE) Gastroenterology. 1999;116(2):286–93. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraker DL, Norton JA, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome alters the natural history of gastrinoma. Ann Surg. 1994;220(3):320–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartsch DK, Fendrich V, Langer P, et al. Outcome of duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2005;242(6):757–64. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189549.51913.d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thevenon J, Bourredjem A, Faivre L, et al. Higher risk of death among MEN1 patients with mutations in the JunD interacting domain: a Groupe d'étude des Tumeurs Endocrines (GTE) cohort study. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(10):1940–1948. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anlauf M, Perren A, Klöppel G. Endocrine precursor lesions and microadenomas of the duodenum and pancreas with and without MEN1: criteria, molecular concepts and clinical significance. Pathobiology. 2007;74(5):279–284. doi: 10.1159/000105810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]