Abstract

A mounting body of evidence indicates that dietary fiber (DF) metabolites produced by commensal bacteria play essential roles in balancing the immune system. DF, considered nonessential nutrients in the past, is now considered to be necessary to maintain adequate levels of immunity and suppress inflammatory and allergic responses. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are the major DF metabolites and mostly produced by specialized commensal bacteria that are capable of breaking down DF into simpler saccharides and further metabolizing the saccharides into SCFAs. SCFAs act on many cell types to regulate a number of important biological processes, including host metabolism, intestinal functions, and immunity system. This review specifically highlights the regulatory functions of DF and SCFAs in the immune system with a focus on major innate and adaptive lymphocytes. Current information regarding how SCFAs regulate innate lymphoid cells, T helper cells, cytotoxic T cells, and B cells and how these functions impact immunity, inflammation, and allergic responses are discussed.

Keywords: Microbiota, Dietary fiber, Short-chain fatty acids, Innate lymphoid cells, B cells, Th1, Th17, Tregs, CD8, Microbial metabolites

Subject terms: Mucosal immunology, T-helper 17 cells

Introduction

The colon and the adjacent part of the small intestine contain many microbes, which are predominantly bacteria and some fungal species. These microbes produce a myriad of metabolites from dietary components and host-produced biomolecules in the gut.1,2 Some of these metabolites function as important regulators of host physiology and the immune system. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), may be the best examples of these biologically active microbial metabolites. SCFAs are efficiently produced by certain bacterial species in the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla (Fig. 1). As the most abundant anions in the colonic lumen, SCFAs are absorbed and partially utilized by colonic epithelial cells. They reach other organs and exert regulatory functions to control glucose and fat metabolism; they also regulate the immune system. SCFAs promote immunity and suppress inflammatory responses in the intestine and other organs. These functions are mediated by multiple mechanisms, including histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition, G-protein-coupled receptor (GPR) signaling, acetyl-CoA production, and metabolic integration. Through combinations of these mechanisms, SCFAs can promote both immune responses and immune tolerance. In this review, the functions of SCFAs and their receptors in regulating immune cells, with a focus on innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), T cells, and B cells, are discussed.

Fig. 1.

Major prebiotic sources and production of SCFAs. SCFAs, such as acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4), are produced from a number of DF and digestion-resistant starches by the cooperative catabolic activity of commensal bacteria. These bacteria have complex carbohydrate-degrading enzymes and/or the enzymes involved in SCFA-producing pathways, such as the succinate, acrylate, and propanediol pathways. Food rich in DF enhances the growth of the commensal bacteria that produce SCFAs. Whole grains are a good source of inulin, arabinoxylan, and β-glucan. Fruits are a good source of pectin. Human breast milk is a rich source of oligofructose, which is used to produce SCFAs in infants. Starches engineered to be resistant to digestion also reach the colon for microbial fermentation. Inadequate DF consumption is common in certain demographic groups in developed countries, leading to SCFA deficiency-related immune insufficiency and dysregulation. Produced SCFAs have strong local effects on the intestine and can exert systemic effects following transport to other organs through the portal vein and blood circulatory system

Overview of the immunoregulatory effects of SCFAs

In general, the available body of evidence indicates that SCFAs enhance immunity to defend against pathogens. In experimental animals, SCFAs increase immunity to extracellular bacteria (C. rodentium and C. difficile), viruses (influenza and respiratory syncytial viruses), and intracellular pathogens (Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella typhimurium).3–6 In contrast, DF and SCFAs exacerbate helminth infection.7 Whether this is a universal phenomenon or specific to certain helminth types remains to be established.

DF and SCFAs have protective effects on allergic diseases.8–11 DF and SCFAs suppress allergic responses in the lungs in experimental animals and are linked to decreased allergic responses in humans. DF and SCFAs are also implicated in suppression of experimental food allergy in animals.10 As discussed later in this article, SCFAs suppress ILC2 and IgE responses,10,12,13 and these effects, in part, account for the observed beneficial effects on allergic diseases.

High levels of DF intake and SCFA production decrease colitis in animals and human patients.14–16 SCFA administration ameliorates various types of experimental colitis, such as T-cell- and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis.17,18 However, some human clinical studies have reported mixed or no clear beneficial effects of SCFA-based therapies, suggesting varied levels of benefit depending on patient characteristics and treatment regimens.19,20 Ffar2 (GPR43) plays an important role in increasing barrier immunity to control invading microbes in gut tissues.6 SCFAs, however, can exacerbate acute colitis in animals induced with DSS or 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid.21,22 Moreover, DF and SCFAs suppress chronic colitis and inflammation-associated colon cancer development.23,24 Beyond colitis, SCFAs are also implicated in ameliorating autoimmune neuroinflammation, kidney inflammation, and atherosclerosis.25–27 The protective effects of SCFAs are likely to be mediated through both tissue cells and immune cells, including epithelial cells, myeloid cells, T cells, B cells, and ILCs.

It should be noted that some of the anti-inflammatory effects of DF could be mediated by non-SCFA pathways. Certain functions of DF are mediated by physical properties, such as bulking fecal content and binding ions, biomolecules, and bacteria.28,29 Moreover, DF can contain other biologically active plant materials, which often have antioxidant and other protective activities. For example, ferulic acid, a phenolic compound in some plant cell walls, is released upon DF degradation by bacteria and can exert anti-inflammatory and other beneficial effects, in part, through its antioxidant properties.30,31 The effect of DF on microbiome composition is also significant in suppressing chronic inflammation and metabolic diseases.32–34

Production and distribution of SCFAs in the body

SCFAs are mainly produced by commensal microbes as the end products of carbohydrate fermentation under anaerobic conditions in the colon (Fig. 1). SCFAs are incompletely oxidized metabolites and water soluble due to their short hydroxyl carbon backbones that contain fewer than six carbons. SCFAs are distinguished from hydrophobic medium-chain (C6-12) and long-chain (>C13) fatty acids. While DF (commonly called prebiotics) is the major source of SCFAs,35 other nutrients, such as proteins and peptides, can be metabolized to produce SCFAs, albeit at low levels.36 In this regard, proteins are the major source of minor volatile SCFAs, such as isobutyrate and isovalerate.37 While not a major source, C2 can also be produced from alcohol in host cells.38 Digestion-resistant oligofructose, inulin, pectin, and arabinoxylan are good prebiotics that are fermented by microbes to produce C2, C3, and C4.39,40 Cellulose, lignin, and chitin are types of insoluble dietary fiber; therefore, their bioavailability for the production of SCFAs is relatively low compared to that of soluble dietary fiber in the gut. Moreover, host carbohydrate biopolymers, such as mucins, can be fermented by certain microbes in the context of DF deficiency, leading to loss of the protective mucous layer.41

In the proximal colon of humans, the luminal concentrations of C2, C3, and C4 reach as high as ~130 mmol/kg of luminal content.42 The SCFA concentration in the distal colon is lower but still high at ~80 mmol/kg, and the concentration in the small intestine is ~15 mmol/kg. The lower part of the small intestine, particularly the last segment (the ileum), has significant levels of SCFAs. A significant portion of the SCFAs produced in the colon are absorbed into colonocytes.43,44 Much of the absorbed SCFAs are used by colonocytes, but some reach the blood by passive diffusion and active transport through solute transporters. The portal vein that moves absorbed nutrients from the intestine to the liver maintains fairly high SCFA concentrations at ~250 μM for C2, 20–200 μM for C3, and 15–65 μM for C4.45 SCFAs are also detectable in the peripheral blood at 20–150 μM for C2, 1–13 μM for C3, and 1–12 μM for C4 depending on the host condition. Comparable levels of SCFAs are present in mouse blood.45 These blood SCFA concentrations are considered high enough to affect host cells throughout the body.

Microbes are highly heterogeneous in their SCFA-producing capacity.46,47 The optimal diversity of commensal microbes, promoted by high levels of DF consumption and good health, leads to enrichment of SCFA producers.31 These microbes have polysaccharide utilization loci (PULs), which encode enzymes that recognize and degrade complex carbohydrates. PUL gene products allow microbes to make mono- and disaccharides from DF and other carbohydrates. These saccharides are utilized by microbes to produce SCFAs. Microbes with PULs may or may not produce SCFAs themselves because additional enzymes are required to ferment sugars into SCFAs. Most enteric and acetogenic bacteria produce C2 via the reductive acetogenesis process.48 Bacteria metabolize sugars to produce C3 through several different pathways, including the succinate, acrylate, and propanediol pathways.49 The succinate pathway is the preferred pathway for Bacteroidetes and some Firmicutes species. C4 is produced from acetoacetyl-CoA, which is produced from two molecules of acetyl-CoA. Butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase generates C4 from butyryl-CoA. Roseburia, Eubacterium, Anaerostipes, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii species have butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA-transferase, which extends acetyl-CoA to produce C4.36,49 Another pathway to produce C4 is via phosphotransbutyrylase and butyrate kinase. For example, certain Coprococcus species and many Clostridium species in the Firmicutes family have butyrate kinase to produce C4.50

SCFA production can be altered by changes in the host condition, such as alterations in diet and the health status. Diets rich in dietary fiber, of course, increase SCFA production in the gut and increase SCFA levels in the blood. It has been reported that infection by helminths increases SCFA production by enriching Trichinella spiralis, a SCFA-producing species.51 This could benefit parasites because SCFAs suppress Th2 or antihelminth immune responses. In contrast, it has been reported that infection by influenza virus decreases intestinal SCFA production, leading to increased superinfection by pneumococci in the lungs.5 Thus, infection can alter SCFA production. The potentially distinct effects of SCFAs on the immune responses to different pathogens will be discussed later.

Cellular uptake and intracellular functions of SCFAs

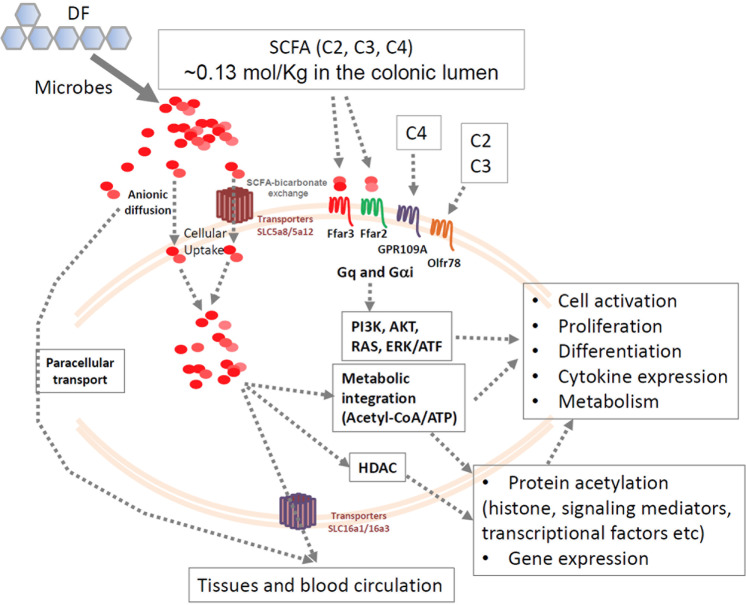

SCFAs enter cells through passive diffusion and carrier-mediated absorption through solute transporters (Fig. 2). The major transporters include SLC5a8 (also called sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter 1) and SLC16a1 (monocarboxylate transporter 1).52–55 These transporters can transport SCFAs and related metabolites, such as ketone bodies, lactate, and pyruvate, into cells.52,53,56–66 Other transporters include SLC16a3 and SLC5a12.67 SLC5a8 and SLC5a12 are expressed in the apical membrane, whereas SLC16A3 is expressed in the basolateral membrane. SLC16a1 is expressed in both the apical and basolateral membranes.67 These transporters allow efficient transport of SCFAs from the gut lumen into colonocytes and lamina propria and eventually to the blood.

Fig. 2.

Transport, G-protein-coupled receptors, and intracellular functions of SCFAs. SCFAs are imported into colonocytes and tissues via several transporters and paracellular transport. Intracellular SCFAs are utilized within colonocytes, but some are further transported to the blood circulation. SCFAs activate cell-surface GPRs, such as Ffar2, Ffar3, GPR109A, and Olfr78, to activate signaling pathways, such as the PI3K, AKT, RAS, and ERK1/2 pathways. These signals crosstalk and boost cytokine signaling to induce cell activation and proliferation. SCFAs, particularly C3 and C4, are effective HDAC inhibitors and induce protein acetylation, which regulates cell activation and gene expression. SCFAs are also readily converted into acetyl-CoA to fuel the TCA cycle for the production of ATP and metabolic building blocks and to further support protein acetylation activity

SCFAs are important nutrients for host cells. A significant portion of estimated calories come from SCFAs produced in the colon.68 It has been estimated that ~70% of the energy required to support colonocytes comes from SCFAs.69 SCFA metabolism in the intestine, liver, and muscles facilitates the production of cholesterol, long-chain fatty acids, glucose, glutamine, and glutamate.70 It is expected that SCFAs are metabolized by many cell types, including immune cells, which has the potential to support cell activation and functional maturation. For example, B cells can take up SCFAs to increase acetyl-CoA levels for fatty acid synthesis and fuel the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle).45 This function of SCFAs is important for immune cell differentiation, as described in detail in the next sections.

SCFAs have long been known as natural inhibitors of HDACs.71 C4 and C3 have higher HDAC-inhibiting activity than C2.72–74 SCFAs directly inhibit class I/II HDACs.73,75,76 The activity of class III HDACs, such as Sirt1, may be indirectly downregulated by SCFAs through gene expression regulation.77 Histone acetyl transferases (HATs) induce acetylation of proteins, whereas HDACs remove acetyl groups, thus antagonizing the acetylation activity of HATs.78 With effects on both acetyl-CoA production and HDAC inhibition, SCFAs effectively promote protein acetylation, which affects the functions of many proteins, including histones and their activity related to chromosomal conformation and gene expression.79–81 SCFA-mediated HDAC inhibition promotes cell type-specific biological processes, and this function is largely independent of cell-surface SCFA receptors.

Cell-surface GPRs sense SCFAs in the extracellular space

SCFAs in extracellular tissue spaces are sensed by several GPR (Fig. 2). Ffar2 and Ffar3 (GPR41) sense the presence of C2, C3, and C4 with somewhat different sensitivities.82,83 The agonistic activity of C2 and C3 specific for Ffar2 starts at ~10 μM and peaks at 10 mM for Ffar2-overexpressing Chinese hamster ovary cells.84 C4 and other longer chain SCFAs can activate Ffar2 only at high (millimolar) concentrations. Thus, Ffar2 is activated more readily by C3 and C2 than C4.84 In contrast, Ffar3 is activated better by C3 and C4 than C2. Ffar3 is expressed in apical enterocytes and basolateral enteroendocrine cells in the human colon.85 Enteroneuronal cells and sympathetic ganglia express Ffar3, which is relevant for the regulatory effect of SCFAs on gut motility.86,87 Ffar3 is also expressed by cells in adipose and pancreatic tissues and by renal smooth muscle cells.83,88–90 This expression pattern of Ffar3 in various cell types is in line with the effect of SCFAs on the production of gut hormones, such as glucagon-like peptide 1, peptide YY, cholecystokinin, and leptin, to regulate metabolism and obesity. In the immune system, Ffar3 is expressed by thymic medullary epithelial cells, B cells (follicular, GC, and B1b), spleen CD8+ dendritic cells (CD8+ DCs), neutrophils, Nkp46+ ILC3s, and blood monocytes (Table 1). Ffar2 is also expressed on enterocytes, mucosal mast cells, and enteroendocrine cells.91,92 Ffar2 is also expressed by leukocytes, such as eosinophils, basophils, neutrophils, monocytes, and DCs.93 RNA-seq data indicate that thymic medullary epithelial cells, B cells, and Nkp46+ ILC3s also express Ffar2 (Table 1). GPR109A senses C4 and niacin (vitamin B3).94,95 GPR109A expression has been detected in neutrophils and macrophages (Table 1). Another SCFA receptor, Olfr7, senses C2 and C3. It is expressed in the kidneys by renal afferent arterioles and autonomic nervous cells.96–98 This is consistent with the effects of C2 and C3 on renin production and the regulation of blood pressure. In the immune system, Olfr78 mRNA is expressed by T cells (CD8, γδ, and NKT), B cells (follicular and GC), and ILC2s (Table 1). SCFA-sensing GPRs play comprehensive roles from metabolic to neuronal and immune regulation through their fast-acting signaling. More studies are required to determine the cell-specific functions of these receptors. It is expected that these receptors are probably activated in intestinal tissues due to the high SCFA levels, but we need to better understand when and where these receptors are activated in systemic tissues where SCFA levels are relatively low.

Table 1.

Expression of SCFA receptors or transporters in the immune systema

| Molecules | Cell types that express the molecules at the mRNA level with relative expression levels indicated |

|---|---|

| Ffar2/GPR43 | ILC3s > Neutrophils > MZ B cells > Pre-T cells (double-negative thymocytes) > DCs (spleen) > ILC2s > Alveolar macrophages |

| Ffar3/GPR41 | Thymic medullary epithelial cells > Follicular B cells > GC B cells > DCs (CD8) > B1b cells ≈ Neutrophils ≈ Nkp46+ ILC3s ≈ Blood monocytes |

| Gpr109a/Hcar2 | Neutrophils > Red pulp macrophages > Alveolar macrophages |

| Olfr78 | CD8 T cells (memory) > γδ T cells > Follicular B cells > GC B cells > NKT cells > ILC2s |

| Slc5a8 | Thymic medullary epithelial cells >> NKT cells = Neutrophils |

| Slc5a12 | Thymic medullary epithelial cells > Mast cells > NK cells ≈ NKT cells = ILC3s > ILC2s ≈ Thymocytes (double positive) ≈ pDCs > Macrophages > DCs (CD8) |

| Slc16a1 | Pro-B cells > Mast cells ≈ Thymocytes (double-negative and positive) > Naive CD8 T cells > Effector CD8 T cells ≈ GC B cells ≈ NKT cells ≈ ILC2s |

Distinct regulation of ILC subsets by SCFAs and GPR signaling

ILCs are present throughout the body, including barrier tissues, and appear to be a key target of regulation by microbial metabolites.99 ILCs do not express antigen receptors but are similar to T cells in the expression of cytokines and master transcription factors (i.e., RORγt for ILC3s, Gata3 for ILC2s, and T-bet for ILC1s). They are primarily activated by cytokines produced by various tissue and myeloid cells in an ILC group-specific manner.100 ILCs originate from progenitors in the fetal liver and adult bone marrow (BM).101–103 The development of common ILC progenitors in the BM requires IL-7 and a number of transcription factors, such as Id2, TOX, and Nfil3.104–108 ILCs include group 1 (NK cells and non-NK ILC1s), group 2 (ILC2s), and group 3 (ILC3s).109 ILC1s produce IFNγ. ILC2s produce IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. ILC3s produce IL-22, IL-17A/F, and GM-CSF. ILC3s are subdivided into lymphoid tissue-inducer (LTi) cells and other ILC3s, which are further divided into natural cytotoxicity receptor (NCR)+ and NCR− ILC3 subsets.51,52 ILC1s respond to and control infection by obligate intracellular pathogens (i.e., viruses, Salmonella, and Toxoplasma gondii). ILC2s respond to helminth infection. ILC3s respond to extracellular pathogens (bacteria and fungi) and are effective in clearing pathogens. In addition, ILCs, such as ILC2s and ILC3s, stimulate tissue remodeling and repair110,111 and regulate adaptive immunity.112,113 Moreover, ILC2s induce beiging of white adipose tissue for lipolysis.114,115 ILC3s are important regulators of intestinal barrier immunity and regulate the microbiota.109,116–118

In general, peripheral ILC activity is profoundly affected by the microbiota. In particular, ILC3 activity is highly regulated by the microbiota.119–121 There are several mechanisms by which microbes regulate ILCs. First, the microbiota stimulates epithelial cells and antigen-presenting cells, such as macrophages and DCs.122 Triggering TLRs on these cells can induce ILC-stimulating cytokines.123 The microbiota increases the numbers and activity of ILC3s by inducing the expression of IL-1β and IL-23.123–126 On the other hand, Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin/TSLP, IL-33, and IL-25 trigger ILC2 proliferation and functional activation, whereas type I/II IFNs suppress ILC2 responses.127,128 Commensal microbes induce the expression of IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18, which increases ILC1 activity.116,121,129 While there is no clear evidence that microbes directly regulate NK cells and ILC1s, the activity of these cells may be indirectly affected by microbiota-stimulated mononuclear phagocytes, which produce activating cytokines, such as type I interferons.120

It has been observed that the metabolites produced by commensal bacteria greatly influence ILCs. Microbial metabolites are diverse, including those derived from carbohydrates, proteins, phytochemicals, and host biomolecules.1 Some of these metabolites activate aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X receptor, and TGR5, which are differentially expressed by various host cells. For example, indole-3-acetate (I3A) agonizes AhR, which is a transcription factor that induces certain groups of genes, including those that encode enzymes that metabolize toxic chemicals or factors that regulate cell differentiation and activation. I3A increases NCR+ and LTi ILC3 responses in an AhR-dependent manner.124,126,130

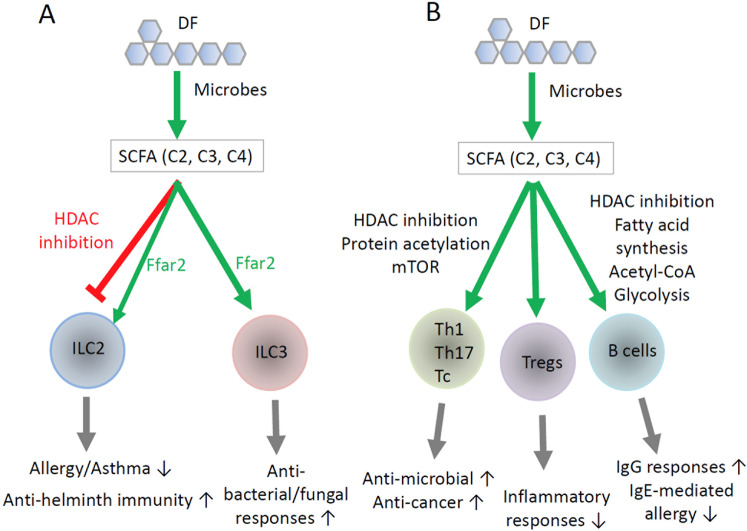

As major carbohydrate metabolites, SCFAs can regulate ILCs.13,131,132 SCFA positively regulate intestinal ILC3s. Infection by extracellular bacteria, such as Citrobacter rodentium and Clostridium difficile, induces ILC3 responses, which are effective in clearing the infection (Fig. 3). Defective ILC3 responses have been observed in Ffar2-deficient mice infected by these pathogens.132,133 Colonic ILC3s express Ffar2, and Ffar2 agonism promotes ILC3 activity in the intestine.132 Chun et al. reported that Ffar2 increased AKT and STAT3 signaling and the numbers of IL-22+CCR6+ ILC3s. Another group reported that C2 is beneficial in ameliorating C. difficile infection.133 This amelioration is mediated by Ffar2-dependent recruitment of neutrophils and ILC3s. In this context, neutrophils highly express GPR43 and are chemotactically attracted to SCFAs. C2 also facilitates inflammasome activation to facilitate the release of IL-1β from neutrophils. Ffar2 signaling augments the expression of IL-1β receptor on ILC3s, resulting in Ffar2- and IL-1β-enhanced ILC3 responses. We also observed that Ffar2 supports the proliferation and function of colonic ILC3s.134 Ffar2 signaling also has a positive effect on ILC1s, but compared to that on ILC3s, the effect seems smaller. Ffar2 signaling costimulates cytokine signaling for robust ILC proliferation and activation. Key pathways that are boosted by Ffar2 signaling are the STAT3, STAT5, STAT6, and PI3K pathways. In this regard, mTOR activation, cell proliferation, and IL-22 production are enhanced by Ffar2 activation in ILC3s. A recent report indicated that SCFAs can also function as AhR agonists in intestinal epithelial cells.135 Thus, there is a possibility that the ILC3-boosting activity of SCFAs is mediated, in part, by their AhR activation function.

Fig. 3.

Direct regulation of ILCs, T cells, and B cells by SCFAs. A SCFAs differentially regulate ILC2s and ILC3s. In general, SCFAs increase ILC3 activity, while they suppress ILC2 activity. Ffar2 signaling in ILC2s and ILC3s triggers PI3K, AKT, and mTOR activity to promote cell proliferation and activation. The effects of SCFAs and GPR43 on ILCs are not identical. While Ffar2 signaling increases the activity of both ILC2s and ILC3s, SCFAs increase ILC3 function but suppress ILC2s. This implies that the GPR signaling vs. intracellular functions of SCFAs can play distinct roles in regulating ILC2s. B DF and SCFAs support the activity of T helper cells, T cytotoxic cells, Tregs, and B cells. A key function of SCFAs is increasing protein acetylation and cellular metabolism in T and B cells. This influences naive T-cell differentiation into Th1 cells, Th17 cells, and Tregs. SCFAs do not polarize naive T cells undergoing differentiation themselves but costimulate T cells along with cytokines and TCR activation to vigorously generate effector Th1 and Th17 cells. In a TGFβ-rich environment in a steady state, such as in the intestine, SCFAs induce the generation of IL-10-producing Tregs. SCFAs also boost the effector function of CD8 T cells to promote cytotoxic activity. SCFAs also energize B cell activation and differentiation into GC B cells and plasma cells for the production of IgG and IgA but suppress the production of IgE. The regulatory effects of SCFAs on immune cells reach beyond the intestine. While Ffar2 is important in the regulation of ILCs, the intracellular effects of SCFAs, such as those mediated by acetyl-CoA and HDAC inhibition, play major roles in the regulation of T and B cells. Overall, SCFAs support the effector functions of lymphocytes to defend against microbial pathogens and cancer but can weaken immunity against helminths. SCFAs can also exert anti-inflammatory and antiallergy functions, in part, by strengthening gut barrier immunity, supporting Treg activity, and suppressing IgE production, mast cells, and ILC2s

While Ffar2 signaling supports ILC2 activity, SCFAs contradictorily suppress overall ILC2 activity.134 Thus, the effects of SCFAs and Ffar2 signaling on ILC2s can be different, which may be because SCFAs regulate cells via several different mechanisms beyond cell-surface GPRs. Other groups have also reported that SCFAs suppress ILC2 responses and associated allergic responses in the lungs.12,13 The detailed mechanism remains speculative, but Ffar2-independent intracellular mechanisms are likely to be involved. In this regard, ILC2s express SCFA transporters to take up SCFAs for intracellular functions.134 SCFAs acetylate histones in ILC2s, and HDAC inhibition appears to be involved in this process.12,13 Administration of butyrate producers, such as Clostridia butyricum and Clostridia sporogenes, induce elevated levels of C3 and C4 in the lungs and decrease the numbers of IL-5/IL-13-producing ILC2s.13 Additionally, C4 administration suppresses the Alternaria alternata (an allergenic fungus) extract-induced ILC response and reduces lung allergy severity (Table 2).12 Thus, SCFAs regulate ILC subsets in a shared yet distinct manner through multiple mechanisms that involve GPR signaling and GPR-independent intracellular functions.

Table 2.

Regulation of infection, inflammation, and allergy by DF and SCFAs

| Diseases | Exacerbation | Protection | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection by extracellular pathogens |

C. rodentium C. difficile |

6,45,133 | |

| Infection by intracellular pathogens |

Influenza virus Respiratory syncytial virus Listeria monocytogenes Salmonella typhimurium |

3–5,184,185 | |

| Infection by helminths | Trichuris muris | 7 | |

| Colitis | Acute 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)- or dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis | Chronic DSS- or azoxymethane (AOM)/DSS-induced colitis | 20–23,186,187 |

| Autoimmune diseases |

Experimental autoimmune encephalitis Cuprizone-induced demyelination Chronic kidney disease Type I diabetes |

25,27,34,174,188,189 | |

| Allergic diseases |

Allergen-induced lung allergy/asthma, peanut-induced food allergy in mice |

10,12,13 | |

| Other inflammatory diseases | Spontaneous SCFA-induced urethritis in mice | Atherosclerosis | 145,160 |

SCFAs support both the effector and regulatory functions of T cells depending on the host condition

Early work identified the potential of SCFAs in regulating cytokine production by T cells and other cells.136–138 Later, it was determined that SCFAs promote the activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs).139 Tregs are heterogeneous, including both FoxP3+ T cells and FoxP3− T cells, which may or may not produce IL-10. FoxP3+ Tregs express CTLA4, TGF-β1, IL-35, galectin-1, granzymes, and other effector molecules to suppress major types of immune cells and thus prevent inflammatory diseases.140 While the exact phenotype of the increased Treg population established by SCFAs is equivocal, the consensus in the field is that SCFAs increase the activity of FoxP3+ T cells and IL-10 production.141,142 SCFAs, when administered orally, efficiently increase the numbers of Tregs in the colon. DF feeding can also increase Treg numbers in the intestines and lungs.143 In support of this role of SCFAs, SCFA-producing bacteria, such as certain Clostridia strains, support the generation of FoxP3+ T cells.144 Thus, SCFAs maintain tolerogenic T cells in the steady state to prevent potential inflammatory responses in the intestine (Fig. 3). The HDAC-inhibiting function of SCFAs increases histone acetylation to regulate gene expression. The FoxP3 and IL-10 gene loci are targets of such regulation in the steady state.141,142 A question that arises is how SCFAs selectively induce the expression of a few genes, such as FoxP3 and IL-10. Indeed, this is not highly likely because SCFAs regulate a myriad of other genes in T cells undergoing activation.72 Moreover, indirect functions of SCFAs mediated through other cell types, such as DCs, are also important in inducing Tregs and IL-10 expression.

SCFAs also boost the generation of Th1 and Th17 cells during active immune responses.72,145 SCFAs promote Th1 and Th17 polarization in vitro in the presence of appropriate cytokines. Moreover, SCFAs support Th1 and Th17 responses not only in the intestine but also in systemic tissues, such as the spleen and lymph nodes, during C. rodentium infection (Table 2).6 It has also been reported that the adjuvant effect of cholera toxin involves the SCFA-Ffar2 axis.146 It appears that SCFAs boost T-cell responses in a manner dependent on host conditions or the immunological milieu (Fig. 3). In the steady state, SCFAs favor IL-10-mediated immune tolerance. However, during active immune responses, SCFAs help generate the effector T cells required to clear pathogens. This can also be applied to cytotoxic (CD8) T cells. SCFAs increase the cytotoxic activity and IL-17 production capacity of CD8 T cells.147 Moreover, C4 enhances the memory T-cell response upon antigen re-encounter.148 A major mechanism appears to involve HDAC inhibition and metabolic regulation rather than cell-surface GPRs. Indeed, most mature T cells hardly express SCFA-sensing GPRs, except Olfr78, which is expressed by some memory CD8 T cells (Table 1). A SCFA-related metabolite, β-hydroxybutyrate, is generated through ketogenesis by host cells and can epigenetically modify Lys 9 of histone H3 (H3K9) associated with certain genes, such as Foxo1 and Ppargc1a (which encodes PGC-1α). These factors upregulate the expression of the cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase Pck1,149 which is required for optimal memory CD8 T-cell generation. It is important to note that SCFAs and related HDAC inhibitors are likely to affect many genes in CD8 T cells, the effect of which has yet to be studied. While the increased effector T-cell population can fight infections, there is a possibility that SCFAs may also increase potentially harmful inflammatory responses (Table 2). Indeed, chronic SCFA feeding induces Th17-mediated urethritis, resulting in hydronephrosis.145 Whether SCFAs exacerbate other chronic inflammatory diseases should be studied.

SCFAs profoundly affect the mTOR pathway in T cells and regulate cellular metabolism.72 SCFAs are readily converted to acetyl-CoA, which is a key metabolic currency that fuels major metabolic processes, such as the mitochondrial TCA cycle, fatty acid synthesis, and protein acetylation. The TCA cycle produces ATP and metabolic building blocks. Increased levels of ATP fuel many cellular activities and relieve AMP-induced suppression of mTOR activation.150 Appropriate regulation of mTOR activity is critical for normal T-cell differentiation into effector vs. regulatory T cells. For example, polarization of Th1 and Th17 cells requires high mTOR activity.151,152 In T cells, SCFAs induce acetylation of S6K, which is downstream of the mTOR pathway.72,153 This is likely induced by the HDAC-inhibiting activity of SCFAs. Thus, S6K could be a potential molecular target of SCFAs involved in increasing mTOR activity in T cells. In general, mTOR activity promotes effector T cells at high levels but promotes FoxP3+ Treg generation at low levels. Increased mTOR activity and ATP levels induced by SCFAs support the generation of Th1 cells, Th17 cells, and IL-10+ T cells.

SCFAs regulate certain tissue cells and antigen-presenting cells through HDAC and GPR triggering. DCs and macrophages are regulated by SCFAs, indirectly regulating T-cell activity. SCFAs suppress not only the hematopoiesis of myeloid DCs but also the functional maturation of DCs.21,154–156 SCFAs also suppress the upregulation of the expression of MHC II, CD80, CD86, and IL-12, which are important for activating T cells and generating Th1 cells.157 It has been reported that SCFA-treated DCs have decreased IL-12 production but increased IL-23p19 production.21 Signaling through GPR109a and Ffar2 induces Treg-inducing DCs.158 SCFAs also generate tolerogenic macrophages that induce IL-10 production in T cells in a GPR109a-dependent manner.158 It has also been reported that C4 conditions macrophages to decrease the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6, and this effect is likely to be mediated via HDAC inhibition.159,160 Thus, the direct and indirect effects of SCFAs can coordinately support both effector T cells and regulatory T cells in various host conditions.

SCFAs regulate antibody production

Commensal microbiota species regulate B cell responses and antibody production. In germ-free mice and mice treated with antibiotics, the production of IgG and IgA in response to pathogens is decreased.45,161,162 Moreover, DF feeding generally has positive effects on blood and gut luminal levels of antibodies, such as IgG and IgA.163–165 Similarly, shorter prebiotics, such as galacto-oligosaccharides, increase IgA production.10 A mechanism of B cell regulation by DF appears to be mediated by enrichment of certain microbes that promote B cell responses. DF enriches DF-utilizing microbes, leading to increased SCFA production. In this regard, certain probiotics, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria species, increase the production of IgG and IgA. SCFAs, when administered in the drinking water, increase antibody production.45 SCFAs boost B cell differentiation into germinal center (GC) B cells and plasma cells in secondary lymphoid tissues, such as Peyer’s patches, the mesenteric lymph nodes and the spleen. SCFAs enhance the effect of the activation signals from B cell receptor and cytokine receptors when triggered by IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10.45 While DF and SCFAs increase the production of IgG and IgA, they suppress IgE production. This is in line with the decrease in IgE-mediated allergic responses mediated by DF and SCFAs.10 However, DF and SCFAs exacerbate helminth infections and related inflammatory responses (Table 2).7 This is because IgE is a key effector molecule in defense against helminth infection, and therefore, decreased IgE levels can weaken antihelminth immune responses.

B cells undergo activation, proliferation, differentiation, and antibody secretion, and these processes require efficient production of energy and cell constituents, such as lipids and proteins.166 B cells require glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid synthesis during activation. Glycolysis is particularly important for the survival of GC B cells, and oxidative phosphorylation is relatively more important for the maintenance of plasma cells.167,168 B cells require fatty acid synthesis to become plasma cells.169,170 SCFAs increase the levels of Acetyl-CoA and ATP. Acetyl-CoA fuels the TCA cycle to generate ATP in B cells. This leads to activation of mTOR, which is required for normal B cell activation to differentiate into plasma cells.45 SCFAs also participate in fatty acid synthesis in B cells through acetyl-CoA, which is converted to malonyl-CoA to enter the fatty acid synthesis process. Thus, SCFAs have the capacity to support B cell metabolism upon B cell activation. Along with the metabolic effect, HDAC inhibition by SCFAs is thought to play a key role because trichostatin A, which is a pan-HDAC inhibitor, can mimic the B cell-boosting activity of SCFAs. SCFAs induce epigenetic regulation of key genes involved in metabolic regulation and cell differentiation, such as Aicda, Xbp1, and Irf4, all of which play key roles in B cell differentiation and antibody production.45 SCFAs increase the number of Tfh cells, which are specialized T helper cells that support B cell differentiation into plasma cells.45 SCFAs also increase the levels of epithelial cytokines, such as IL-6,6 which stimulates B cells for antibody production.171

B cells express GPRs to sense SCFAs (Table 1), and it has also been reported that mice deficient in Ffar2 have a relatively low intestinal IgA response.172 Thus, DF and SCFAs can regulate B cells via a number of direct and indirect mechanisms. However, SCFAs can suppress activation-induced deaminase expression and IgG1 production at high SCFA concentrations, and mice fed a diet low in insoluble/soluble DF have increased IgG1 production over those fed high levels of DF.173 Overall, DF and SCFAs are significant factors in regulating host antibody responses (Fig. 3).

Concluding remarks

The broad and lymphocyte-specific regulatory functions of SCFAs have significant impacts on the immune system. ILC3s, T cells, and B cells in the intestine are the primary targets of regulation by SCFAs because the levels of SCFAs are highest in the gut, where SCFAs support the activity of these lymphocytes to promote balanced intestinal immunity and immune tolerance. These effects of SCFAs on lymphocytes appear to work together with those on epithelial cells and myeloid cells to strengthen intestinal barrier immunity, regulate microbes, and prevent harmful inflammatory responses. A significant portion of gut-derived SCFAs are transported out of the gut to impact other organs; therefore, SCFAs affect immune cells beyond the cells in the gut. Indeed, it has been reported that DF and SCFAs increase immune responses in the lungs during viral infection and regulate inflammatory responses in the central nervous system. Moreover, SCFAs regulate systemic lymphocyte responses mediated by CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, B cells, and ILCs during infection.

Because many children and adults, particularly those in certain demographic groups in developed countries, do not consume enough dietary fiber, SCFA deficiency has become a potential health problem. SCFA deficiency can result in weak or imbalanced immunity and increase infection by bacterial and viral pathogens or perhaps enhance susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. For example, decreased blood levels of SCFAs were observed in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as long-term multiple sclerosis.174

While SCFAs are beneficial, SCFAs have the potential to exacerbate certain infections and inflammatory diseases. For example, infection by helminths is likely to be worsened by DF deficiency because SCFAs decrease IgE production and ILC2 activity and suppress mast cells. On the other hand, SCFAs exert beneficial effects on allergic responses because they can decrease the activity of the same immune effectors. It has been documented that chronic elevation of SCFA levels higher than physiological levels can cause T-cell-induced inflammatory responses in the renal system.145 To make the topic even more complex, the functions of SCFAs and their GPRs are not always equivalent because SCFAs can regulate cellular responses in SCFA receptor-independent manners, and many cell types lack or hardly express SCFA-sensing GPRs. This suggests that the functional SCFA system, which is composed of DF, microbes, SCFAs, transporters, receptors, HDACs, cellular metabolism, and downstream signaling pathways, can regulate the immune system in many different ways. Further studies are required to dissect these regulatory mechanisms and determine their impacts on the immune system in various host conditions.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks current and past laboratory members for their invaluable input. Special thanks go to J.H. Park, M.H. Kim, Y. Qie, A. Sepahi, and Q.Y. Liu. This study was supported, in part, by the NIH (R01AI121302, R21AI14889801, R01AI074745, and R01AI080769) and Kenneth and Judy Betz Professorship at the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center at the University of Michigan to C.H.K.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.Kim CH. Immune regulation by microbiome metabolites. Immunology. 2018;154:220–229. doi: 10.1111/imm.12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glowacki RWP, Martens EC. In sickness and health: effects of gut microbial metabolites on human physiology. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008370. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antunes KH, et al. Microbiota-derived acetate protects against respiratory syncytial virus infection through a GPR43-type 1 interferon response. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3273. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trompette A, et al. Dietary fiber confers protection against flu by shaping Ly6c(-) patrolling monocyte hematopoiesis and CD8(+) T cell metabolism. Immunity. 2018;48:992–1005.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sencio V, et al. Gut dysbiosis during influenza contributes to pulmonary pneumococcal superinfection through altered short-chain fatty acid production. Cell Rep. 2020;30:2934–2947.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MH, Kang SG, Park JH, Yanagisawa M, Kim CH. Short-chain fatty acids activate GPR41 and GPR43 on intestinal epithelial cells to promote inflammatory responses in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:396–406.e310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myhill LJ, et al. Fermentable dietary fiber promotes helminth infection and exacerbates host inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 2020;204:3042–3055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trompette A, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2014;20:159–166. doi: 10.1038/nm.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gourbeyre P, et al. Perinatal and postweaning exposure to galactooligosaccharides/inulin prebiotics induced biomarkers linked to tolerance mechanism in a mouse model of strong allergic sensitization. J. Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:6311–6320. doi: 10.1021/jf305315g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle RJ, et al. Prebiotic-supplemented partially hydrolysed cow’s milk formula for the prevention of eczema in high-risk infants: a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71:701–710. doi: 10.1111/all.12848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toki S, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A suppresses murine innate allergic inflammation by blocking group 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) activation. Thorax. 2016;71:633–645. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thio CL, Chi PY, Lai AC, Chang YJ. Regulation of type 2 innate lymphoid cell-dependent airway hyperreactivity by butyrate. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;142:1867–1883.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis G, et al. Dietary fiber-induced microbial short chain fatty acids suppress ILC2-dependent airway inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2051. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. A prospective study of long-term intake of dietary fiber and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:970–977. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amre DK, et al. Imbalances in dietary consumption of fatty acids, vegetables, and fruits are associated with risk for Crohn’s disease in children. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2016–2025. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheppach W, et al. Effect of butyrate enemas on the colonic mucosa in distal ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:51–56. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91094-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslowski KM, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sina C, et al. G protein-coupled receptor 43 is essential for neutrophil recruitment during intestinal inflammation. J. Immunol. 2009;183:7514–7522. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinhart AH, Hiruki T, Brzezinski A, Baker JP. Treatment of left-sided ulcerative colitis with butyrate enemas: a controlled trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996;10:729–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1996.d01-509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breuer RI, et al. Short chain fatty acid rectal irrigation for left-sided ulcerative colitis: a randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 1997;40:485–491. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berndt BE, et al. Butyrate increases IL-23 production by stimulated dendritic cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1384–G1392. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00540.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarrerias A, et al. Short-chain fatty acid enemas fail to decrease colonic hypersensitivity and inflammation in TNBS-induced colonic inflammation in rats. Pain. 2002;100:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim M, Friesen L, Park J, Kim HM, Kim CH. Microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, restrain tissue bacterial load, chronic inflammation, and associated cancer in the colon of mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018;48:1235–1247. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, et al. Manipulation of the gut microbiota using resistant starch is associated with protection against colitis-associated colorectal cancer in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:366–375. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrade-Oliveira V, et al. Gut bacteria products prevent AKI induced by ischemia-reperfusion. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015;26:1877–1888. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Digby JE, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of nicotinic acid in human monocytes are mediated by GPR109A dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:669–676. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haghikia A, et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity. 2016;44:951–953. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torre M, Rodriguez AR, Saura-Calixto F. Effects of dietary fiber and phytic acid on mineral availability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1991;30:1–22. doi: 10.1080/10408399109527539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:172–184. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadar SS, Vyawahare NS, Bodhankar SL. Ferulic acid ameliorates TNBS-induced ulcerative colitis through modulation of cytokines, oxidative stress, iNOs, COX-2, and apoptosis in laboratory rats. EXCLI J. 2016;15:482–499. doi: 10.17179/excli2016-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Backhed F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marino E, et al. Gut microbial metabolites limit the frequency of autoimmune T cells and protect against type 1 diabetes. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:552–562. doi: 10.1038/ni.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim CH. Microbiota or short-chain fatty acids: which regulates diabetes? Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018;15:88–91. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou J, et al. Fiber-mediated nourishment of gut microbiota protects against diet-induced obesity by restoring IL-22-mediated colonic health. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:41–53.e44. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar V, Sinha AK, Makkar HP, de Boeck G, Becker K. Dietary roles of non-starch polysaccharides in human nutrition: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012;52:899–935. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.512671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003;62:67–72. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarling EJ, Ruchim MA. Protein origin of the volatile fatty acids isobutyrate and isovalerate in human stool. J. Lab Clin. Med. 1987;109:566–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gemma S, Vichi S, Testai E. Individual susceptibility and alcohol effects:biochemical and genetic aspects. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita. 2006;42:8–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose DJ, DeMeo MT, Keshavarzian A, Hamaker BR. Influence of dietary fiber on inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer: importance of fermentation pattern. Nutr. Rev. 2007;65:51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Topping DL, Clifton PM. Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:1031–1064. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desai MS, et al. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167:1339–1353.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, Naylor CP, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28:1221–1227. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruppin H, Bar-Meir S, Soergel KH, Wood CM, Schmitt MG., Jr Absorption of short-chain fatty acids by the colon. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:1500–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Binder HJ, Mehta P. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate active sodium and chloride absorption in vitro in the rat distal colon. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:989–996. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim M, Qie Y, Park J, Kim CH. Gut microbial metabolites fuel host antibody responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barcenilla A, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1654–1661. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1654-1661.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charrier C, et al. A novel class of CoA-transferase involved in short-chain fatty acid metabolism in butyrate-producing human colonic bacteria. Microbiology. 2006;152:179–185. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller TL, Wolin MJ. Pathways of acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal microbial flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:1589–1592. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1589-1592.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reichardt N, et al. Phylogenetic distribution of three pathways for propionate production within the human gut microbiota. ISME J. 2014;8:1323–1335. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Louis P, et al. Restricted distribution of the butyrate kinase pathway among butyrate-producing bacteria from the human colon. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2099–2106. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2099-2106.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piekarska J, et al. Trichinella spiralis: the influence of short chain fatty acids on the proliferation of lymphocytes, the goblet cell count and apoptosis in the mouse intestine. Exp. Parasitol. 2011;128:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H, et al. SLC5A8, a sodium transporter, is a tumor suppressor gene silenced by methylation in human colon aberrant crypt foci and cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8412–8417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430846100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyauchi S, Gopal E, Fei YJ, Ganapathy V. Functional identification of SLC5A8, a tumor suppressor down-regulated in colon cancer, as a Na(+)-coupled transporter for short-chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13293–13296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yanase H, Takebe K, Nio-Kobayashi J, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Iwanaga T. Cellular expression of a sodium-dependent monocarboxylate transporter (Slc5a8) and the MCT family in the mouse kidney. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2008;130:957–966. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0490-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki T, Yoshida S, Hara H. Physiological concentrations of short-chain fatty acids immediately suppress colonic epithelial permeability. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;100:297–305. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508888733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gopal E, et al. Sodium-coupled and electrogenic transport of B-complex vitamin nicotinic acid by slc5a8, a member of the Na/glucose co-transporter gene family. Biochemical J. 2005;388:309–316. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyauchi S, et al. Sodium-coupled electrogenic transport of pyroglutamate (5-oxoproline) via SLC5A8, a monocarboxylate transporter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:1164–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thangaraju M, et al. Sodium-coupled transport of the short chain fatty acid butyrate by SLC5A8 and its relevance to colon cancer. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2008;12:1773–1782. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0573-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh N, et al. Blockade of dendritic cell development by bacterial fermentation products butyrate and propionate through a transporter (Slc5a8)-dependent inhibition of histone deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:27601–27608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gopal E, et al. Expression of slc5a8 in kidney and its role in Na+-coupled transport of lactate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:44522–44532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin PM, et al. Expression of the sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporters SMCT1 (SLC5A8) and SMCT2 (SLC5A12) in retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:3356–3363. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin PM, et al. Identity of SMCT1 (SLC5A8) as a neuron‐specific Na+‐coupled transporter for active uptake of l‐lactate and ketone bodies in the brain. J. Neurochem. 2006;98:279–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halestrap AP, Wang X, Poole RC, Jackson VN, Price NT. Lactate transport in heart in relation to myocardial ischemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997;80:17A–25A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hadjiagapiou C, Schmidt L, Dudeja PK, Layden TJ, Ramaswamy K. Mechanism (s) of butyrate transport in Caco-2 cells: role of monocarboxylate transporter 1. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G775–G780. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.4.G775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alrefai W, et al. Regulation of butyrate uptake in Caco-2 cells by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G197–G203. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00144.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ritzhaupt A, Ellis A, Hosie KB, Shirazi-Beechey SP. The characterization of butyrate transport across pig and human colonic luminal membrane. J. Physiol. 1998;507:819–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.819bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sivaprakasam S, Bhutia YD, Yang S, Ganapathy V. Short-chain fatty acid transporters: role in colonic homeostasis. Compr. Physiol. 2017;8:299–314. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c170014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bergman EN. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol. Rev. 1990;70:567–590. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scheppach W. Effects of short chain fatty acids on gut morphology and function. Gut. 1994;35:S35–S38. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.1_suppl.s35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.den Besten G, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Licciardi PV, Ververis K, Karagiannis TC. Histone deacetylase inhibition and dietary short-chain fatty acids. ISRN Allergy. 2011;2011:869647. doi: 10.5402/2011/869647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park J, et al. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;1:80–93. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hinnebusch BF, Meng S, Wu JT, Archer SY, Hodin RA. The effects of short-chain fatty acids on human colon cancer cell phenotype are associated with histone hyperacetylation. J. Nutr. 2002;132:1012–1017. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J. Nutr. 2003;133:2485S–2493S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2485S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sealy L, Chalkley R. The effect of sodium butyrate on histone modification. Cell. 1978;14:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu X, et al. Short-chain fatty acids from periodontal pathogens suppress histone deacetylases, EZH2, and SUV39H1 to promote Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication. J. Virol. 2014;88:4466–4479. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03326-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peserico A, Simone C. Physical and functional HAT/HDAC interplay regulates protein acetylation balance. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011;2011:371832. doi: 10.1155/2011/371832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ellmeier W, Seiser C. Histone deacetylase function in CD4(+) T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:617–634. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0037-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Benton CB, Fiskus W, Bhalla KN. Targeting histone acetylation: readers and writers in leukemia and cancer. Cancer J. 2017;23:286–291. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cousens LS, Gallwitz D, Alberts BM. Different accessibilities in chromatin to histone acetylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:1716–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eberle JA, Widmayer P, Breer H. Receptors for short-chain fatty acids in brush cells at the “gastric groove”. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:152. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown AJ, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11312–11319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Le Poul E, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25481–25489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tazoe H, et al. Expression of short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR41 in the human colon. Biomed. Res. 2009;30:149–156. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.30.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inoue D, et al. Short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR41-mediated activation of sympathetic neurons involves synapsin 2b phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1547–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kimura I, et al. Short-chain fatty acids and ketones directly regulate sympathetic nervous system via G protein-coupled receptor 41 (GPR41) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8030–8035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016088108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nøhr MK, et al. GPR41/FFAR3 and GPR43/FFAR2 as cosensors for short-chain fatty acids in enteroendocrine cells vs FFAR3 in enteric neurons and FFAR2 in enteric leukocytes. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3552–3564. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xiong Y, et al. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate leptin production in adipocytes through the G protein-coupled receptor GPR41. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1045–1050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bahar Halpern K, Veprik A, Rubins N, Naaman O, Walker MD. GPR41 gene expression is mediated by internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-dependent translation of bicistronic mRNA encoding GPR40 and GPR41 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20154–20163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.358887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Karaki S-I, et al. Expression of the short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, in the human colon. J. Mol. Histol. 2008;39:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9145-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Karaki S-I, et al. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim CH, Park J, Kim M. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids, T cells, and inflammation. Immune Netw. 2014;14:277–288. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.6.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tunaru S, Lättig J, Kero J, Krause G, Offermanns S. Characterization of determinants of ligand binding to the nicotinic acid receptor GPR109A (HM74A/PUMA-G) Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:1271–1280. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Thangaraju M, et al. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2826–2832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pluznick JL, et al. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:4410–4415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xu LL, et al. PSGR, a novel prostate-specific gene with homology to a G protein-coupled receptor, is overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6568–6572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weber M, Pehl U, Breer H, Strotmann J. Olfactory receptor expressed in ganglia of the autonomic nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;68:176–184. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim CH, Hashimoto-Hill S, Kim M. Migration and tissue tropism of innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Scoville SD, Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Cellular pathways in the development of human and murine innate lymphoid cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2019;56:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bando JK, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Identification and distribution of developing innate lymphoid cells in the fetal mouse intestine. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:153–160. doi: 10.1038/ni.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zook EC, Kee BL. Development of innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:775–782. doi: 10.1038/ni.3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yang Q, Bhandoola A. The development of adult innate lymphoid cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016;39:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu W, et al. NFIL3 orchestrates the emergence of common helper innate lymphoid cell precursors. Cell Rep. 2015;10:2043–2054. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Seehus CR, et al. The development of innate lymphoid cells requires TOX-dependent generation of a common innate lymphoid cell progenitor. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:599–608. doi: 10.1038/ni.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yokota Y, et al. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;397:702–706. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cherrier M, Sawa S, Eberl G. Notch, Id2, and RORγt sequentially orchestrate the fetal development of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:729–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Boos MD, Yokota Y, Eberl G, Kee BL. Mature natural killer cell and lymphoid tissue-inducing cell development requires Id2-mediated suppression of E protein activity. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1119–1130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vivier E, et al. Innate lymphoid cells: 10 years on. Cell. 2018;174:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hams E, et al. IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells induce pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:367–372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315854111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Eyerich K, Dimartino V, Cavani A. IL-17 and IL-22 in immunity: driving protection and pathology. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017;47:607–614. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seehus CR, et al. Alternative activation generates IL-10 producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1900. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02023-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hepworth MR, et al. Immune tolerance. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells mediate intestinal selection of commensal bacteria-specific CD4(+) T cells. Science. 2015;348:1031–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Molofsky AB, et al. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:535–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee MW, et al. Activated type 2 innate lymphoid cells regulate beige fat biogenesis. Cell. 2015;160:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Colonna M. Innate lymphoid cells: diversity, plasticity, and unique functions in immunity. Immunity. 2018;48:1104–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cherrier DE, Serafini N, Di Santo JP. Innate lymphoid cell development: a T cell perspective. Immunity. 2018;48:1091–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kotas ME, Locksley RM. Why innate lymphoid cells? Immunity. 2018;48:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Satoh-Takayama N, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ganal SC, et al. Priming of natural killer cells by nonmucosal mononuclear phagocytes requires instructive signals from commensal microbiota. Immunity. 2012;37:171–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gury-BenAri M, et al. The spectrum and regulatory landscape of intestinal innate lymphoid cells are shaped microbiome. Cell. 2016;166:1231–1246.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Soderholm AT, Pedicord VA. Intestinal epithelial cells: at the interface of the microbiota and mucosal immunity. Immunology. 2019;158:267–280. doi: 10.1111/imm.13117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mortha A, et al. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014;343:1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Qiu J, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates gut immunity through modulation of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;36:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kiss EA, et al. Natural aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands control organogenesis of intestinal lymphoid follicles. Science. 2011;334:1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1214914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zelante T, et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity. 2013;39:372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mosconi I, et al. Intestinal bacteria induce TSLP to promote mutualistic T-cell responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:1157–1167. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Duerr CU, et al. Type I interferon restricts type 2 immunopathology through the regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:65–75. doi: 10.1038/ni.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fuchs A, et al. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-gamma-producing cells. Immunity. 2013;38:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lee JS, et al. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat. Immunol. 2011;13:144–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kim SH, Cho BH, Kiyono H, Jang YS. Microbiota-derived butyrate suppresses group 3 innate lymphoid cells in terminal ileal Peyer’s patches. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3980. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02729-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chun E, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptor Ffar2 regulates colonic group 3 innate lymphoid cells and gut immunity. Immunity. 2019;51:871–884 e876. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fachi JL, et al. Acetate coordinates neutrophil and ILC3 responses against C. difficile through FFAR2. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217:e20190489. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sepahi A, Liu Q, Friesen L, Kim CH, et al. Commensal dietary fiber metabolites regulate innate lymphoid cell responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2020;2:317–330. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Marinelli L, et al. Identification of the novel role of butyrate as AhR ligand in human intestinal epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:643. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Nancey S, et al. Butyrate strongly inhibits in vitro stimulated release of cytokines in blood. Digestive Dis. Sci. 2002;47:921–928. doi: 10.1023/a:1014781109498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Cavaglieri CR, et al. Differential effects of short-chain fatty acids on proliferation and production of pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines by cultured lymphocytes. Life Sci. 2003;73:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kurita-Ochiai T, Fukushima K, Ochiai K. Volatile fatty acids, metabolic by-products of periodontopathic bacteria, inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production. J. Dent. Res. 1995;74:1367–1373. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740070801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Smith PM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.McCrudden FH, Fales HL. The cause of the excessive calcium excretion through the feces in infantilism. J. Exp. Med. 1913;17:24–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.17.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Arpaia N, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Furusawa Y, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Thorburn AN, et al. Evidence that asthma is a developmental origin disease influenced by maternal diet and bacterial metabolites. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7320. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Atarashi K, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Park J, Goergen CJ, HogenEsch H, Kim CH. Chronically elevated levels of short-chain fatty acids induce T Cell-mediated ureteritis and hydronephrosis. J. Immunol. 2016;196:2388–2400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yang W, et al. Microbiota metabolite short-chain fatty acids facilitate mucosal adjuvant activity of cholera toxin through GPR43. J. Immunol. 2019;203:282–292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Luu M, et al. Regulation of the effector function of CD8(+) T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:14430. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32860-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Bachem A, et al. Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote the memory potential of antigen-activated CD8(+) T cells. Immunity. 2019;51:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zhang H, et al. Ketogenesis-generated beta-hydroxybutyrate is an epigenetic regulator of CD8(+) T-cell memory development. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020;22:18–25. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Dennis PB, et al. Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Science. 2001;294:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Delgoffe GM, et al. The mTOR kinase differentially regulates effector and regulatory T cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;30:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Chen S, et al. Effect of inhibiting the signal of mammalian target of rapamycin on memory T cells. Transplant. Proc. 2014;46:1642–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Fenton TR, Gwalter J, Ericsson J, Gout IT. Histone acetyltransferases interact with and acetylate p70 ribosomal S6 kinases in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010;42:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Millard AL, et al. Butyrate affects differentiation, maturation and function of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2002;130:245–255. doi: 10.1046/j.0009-9104.2002.01977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Wang B, Morinobu A, Horiuchi M, Liu J, Kumagai S. Butyrate inhibits functional differentiation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Cell. Immunol. 2008;253:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Nascimento CR, Freire-de-Lima CG, da Silva de Oliveira A, Rumjanek FD, Rumjanek VM. The short chain fatty acid sodium butyrate regulates the induction of CD1a in developing dendritic cells. Immunobiology. 2011;216:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Frikeche J, et al. Impact of valproic acid on dendritic cells function. Immunobiology. 2012;217:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Singh N, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014;40:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]