Abstract

Bacteriophage therapy is currently experiencing a renaissance. Therapeutic efficacy of bacteriophages depends on phage-bacterial and phage-host interactions. The appearance of neutralizing anti-phage antibody has been speculated to be one of the few reasons for bacteriophage therapy's failure. This study aimed to know whether there is a rise in the neutralizing antibody on the parenteral injection of bacteriophages in an animal model. This study included bacteriophages against five different bacteria, namely Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella Typhi and Staphylococcus aureus. These bacteriophages were isolated, propagated and purified. Bacteriophage specificity was confirmed by spot testing on the respective bacterial lawn. Weekly subcutaneous injection of purified bacteriophages (109PFU) was given to five rabbits for six weeks. Blood samples were collected before administering the next dose every week. The antibody response was tested by phage neutralization followed by plaque assay by using double agar overlay method. The rise in anti-phage neutralizing antibodies was observed usually after the 3rd week after immunization. Complete neutralization of bacteriophages could be seen between 3 and 5 weeks after immunization. A further rise in bacteriophage counts (PFU), especially on 1:1000 and 1:2000 serum dilutions, could be noticed by the end of 6th week against most bacteriophages injected. Background anti-phage neutralizing antibodies were observed against bacteriophage specific to Escherichia coli. However, it was absent against bacteriophages specific to other four bacteria. Bacteriophage interacts with mammalian host and induces anti-phages neutralizing antibody production. However, neutralization of phage depends on repeated administration and duration of therapy. The significant rise in neutralizing antibody could be seen at the end of 3rd week. Therefore, bacteriophage can be effectively used in acute cases where therapy duration is less than 2 weeks. However, for prolonged therapy, bacteriophage cocktail of different antigenicity may be suggested.

Keywords: Neutralizing antibody, Bacteriophage therapy, Animal model, Immunological response

Introduction

Continuous and intensive use of antibiotics since 1960 has led to the emergence of multi-drug resistant bacterial infections, which are currently a significant challenge in clinical practice. Increased antibiotic resistance and subsequent therapeutic failure of antibiotics have fuelled the discussion on potential alternatives to antibiotics to treat bacterial infections [1]. These alternative approaches are based on the development of biologics. These biological alternatives may include passive immunization, vaccination, targeted modulation of the host immune response, bacteriophage therapy [2]. Bacteriophage therapy is currently experiencing a renaissance because lytic phages can effectively deal with even multidrug-resistant bacteria [3]. Several studies have unequivocally confirmed the effectiveness of phage therapy in laboratory animals, chickens, fish and human beings [4–17]. The therapeutic efficacy of bacteriophages depends on phage-bacterial and phage-host interactions [18]. Despite the evident success of phage therapy; the issues of the evolution of phage-resistant bacteria during treatment, endotoxin storm, transfer of virulent and antibiotic resistance genes in commensal bacteria and immune neutralization are considered significant hurdles to be addressed in phage therapy[19].

Data indicate that phages can interact with the mammalian immune system in various ways that are both direct and indirect [20, 21]. Existence of phage neutralizing antibody before the start of therapy or after repeated therapeutic administration might be a reason for bacteriophage therapy's failure. High-titer bacteriophages usually stimulate the host immune system in an immunocompetent host. In guinea pig and rabbits, the effect of dosing, priming, and boosting has been demonstrated on a humoral immune response about 50 years ago [22–25]. Few studies have reported the antiphage antibody during therapeutic applications in a rodent model [26–28]. However, studies on human subjects have demonstrated anti-phage antibody in > 30% of the subjects even before therapy [29, 30]. However, these interaction data remains patchy, incomplete, and limited to small numbers of phages, cell types, and disease models [20]. There is a need to study the systemic anti-phage immune response in conjunction with the duration of treatment and administration route. Therefore, the present study was planned to evaluate the effect of repeated parenteral injections of bacteriophages on the neutralizing antibody response in an animal model.

Material and methods

The present study was carried out in the Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, from September 2017 to July 2019. The study protocol was approved by the institutional animal ethics committee [Letter no. Dean/2017/CAEC/246 dated 21.11.2017].

Isolation and purification of bacteriophages

This study included partially characterized bacteriophages against five different bacteria, namely Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella Typhi and Staphylococcus aureus. Bacteriophages were isolated from water collected from sewage, hospital premises and river Ganges at Varanasi. The water samples were treated with 1% chloroform and mixed gently for 10 min. It was centrifuged at 13,416 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The centrifugation process was repeated twice, and the pellet was discarded each time, and the supernatant was collected. Bacteriophage isolation was performed by adopting the method used by Adams [31]. Five millilitres of LB broth was inoculated with host bacteria and incubated at 37 °C for overnight in a shaker incubator. About 10 ml of the supernatant water from natural source was mixed with 5 ml of a bacterial culture grown in LB broth and incubated at 37 °C in a shaker overnight. Next day it was treated with 1% chloroform following the similar steps as mentioned above for the water sources. Simultaneously, the specific bacterial strain was lawn cultured on Mueller Hinton agar (MHA) media. The chloroform treated LB supernatant of the broth was dropped on the incubated bacterial lawn and further incubated overnight at 37 °C. MHA plates showing clear zone on the bacterial lawn were washed with Tris Magnesium sulphate Gelatin (TMG) buffer. The removed content was collected in a centrifuge tube. It was treated with 1% chloroform similarly as described earlier. Phages were propagated on the host bacteria in LB broth. After bulk production, the bacteria were killed with 1% chloroform and centrifuged. The clear supernatant was collected. The supernate was subjected to filtration using 0.22 µm membrane filters. The filtrate was further processed for purification (toxin-free) and concentration of phages. The harvested fluid was subjected to membrane dialysis against polyethylene glycol (PEG 6000; 20% in 2.5 M NaCl) for overnight and then washed with PBS (phosphate buffered saline) at 4 °C. This process was repeated thrice at 4 °C. The purified phage preparation was considered a mixture of more than one phages, not the single phage clone.

Purified phages were kept as stock at – 20 °C after checking its lytic activity. Ten-fold dilutions of the phage stock were prepared. Phage titre (PFU/mL) of the stock was determined by double agar overlay technique by applying the formula used by Kropinski et al. [32].

Immunization of rabbits

Weekly subcutaneous injections of partially purified phage particles (109 PFU/mL) against different bacteria were given in the volume of 100 μL to five 7–9 months old male rabbits for six weeks. Weekly blood samples were collected from the ear vein before administering the next dose. Serum was separated and stored at − 20 °C for further assays.

Plaque reduction assay

Collected rabbit's serum was heat-inactivated at 56 °C for one hour in a water bath. It was diluted serially in normal saline from 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000 and 1:2000. Diluted serum (450 μL) was allowed to react with phage (50 μL) for 30 min at 37 °C in a water bath. The titre of phages used as antigens was 1 × 106 PFU/mL. The mixture was diluted up to 1000 times with TMG buffer after incubation and subjected to PFU determination by the double-agar overlay method [33]. The dilution of serum neutralizing the phage was estimated by observing a decrease in the PFU number.

Result and discussion

Rise of anti-phage antibody

Exhibition of resistance by a host against foreign antigens or microorganisms or their products is a natural phenomenon. A significant consequence may be the specific antibodies production on challenging the mammalian immunological system with bacteriophages. Data regarding the anti-phage humoral responses during phage treatment are scarce. In the present study, we looked for the neutralizing antibody response against the bacteriophages after boosting doses. We prepared the phage preparations without full characterization. We aimed to see the induction of neutralizing antibody against a single or mixture of phages to mimick the bacteriophage cocktail usually recommended in clinical practice. In clinical practice, mostly around 109/mL dose of bacteriophages is recommended. Therefore we used the same dose subcutaneously at the weekly interval. Blood was collected just before injecting the subsequent dose. The serum's plaque reduction activity was determined after exposing the bacteriophage with the rabbit's serum and then counting the plaque-forming unit (PFU) using the soft agar overlay method. We picked the 106 PFU/mL bacteriophage concentration for the ease of plaque counting.

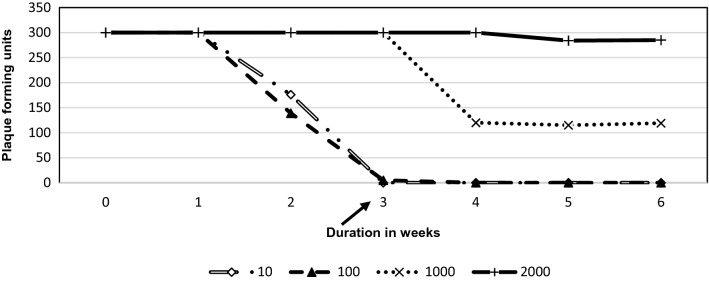

At the serum dilution of 1:10, the highest level of plaque reducing antibody appeared against bacteriophages specific to S. aureus as the PFU counts came down from > 300 to 10 at the end of the second week. However, complete neutralization could be observed only on day 28. A similar pattern was observed for K. pneumoniae as the PFU counts came down to 58 on day 14, but complete neutralization could be seen on day 28 only. Against S. Typhi the appearance of plaque reducing antibody was quick as the PFU count came down from > 300 to 34 in the first week and complete neutralization (0 PFU) could be seen only on day 28 again. It was P. aeruginosa against which the antibody appeared could neutralize entirely at the end of 3rd week, i.e. day 21. It is intriguing to see that the serum sample collected from the rabbit before administering specific phages against E. coli could reduce the PFU count from > 300 to 176. Despite the presence of pre-existing neutralizing antibody against E. coli phages, the complete neutralization could be seen only on day 28 (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5; Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Table 1.

Showing immune response against bacteriophages specific to Escherichia coli in rabbit serum obtained at a different time interval

| Serum dilution | Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage against Escherichia coli [Phage dilution-10–2] | |||||||

| 10× | 176 | 140 | 97 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100× | 175 | 148 | 96 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1000× | 177 | 149 | 94 | 92 | 37 | 46 | 49 |

| 2000× | 211 | 202 | 92 | 90 | 68 | 89 | 102 |

PFU Plaque forming unit

Table 2.

Showing Immune response against bacteriophages specific to Klebsiella pneumoniae in rabbit serum obtained at a different time interval

| Serum dilution | Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage against Klebsiella pneumoniae [Phage dilution-10–2] | |||||||

| 10× | > 300 | > 300 | 68 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100× | > 300 | > 300 | 89 | 12 | 3 | 5 | 28 |

| 1000× | > 300 | > 300 | 289 | 135 | 141 | 177 | > 300 |

| 2000× | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | 176 | 288 | > 300 |

PFU Plaque forming unit

Table 3.

Showing Immune response against bacteriophages specific to Salmonella Typhi in rabbit serum obtained at a different time interval

| Serum dilution | Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage against Salmonella typhi [Phage dilution-10–2] | |||||||

| 10× | > 300 | 34 | 22 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100× | > 300 | 64 | 60 | 47 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1000× | > 300 | 87 | 82 | 65 | 39 | 5 | 6 |

| 2000× | > 300 | 92 | 90 | 82 | 59 | 8 | 37 |

PFU Plaque forming unit

Table 4.

Showing immune response against bacteriophages specific Pseudomonas aeruginosa in rabbit serum obtained at a different time interval

| Serum dilution | Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage against Pseudomonas aeruginosa [Phage dilution-10–2] | |||||||

| 10× | > 300 | > 300 | 176 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100× | > 300 | > 300 | 139 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1000× | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | 120 | 115 | 119 |

| 2000× | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | 284 | 285 |

PFU Plaque forming unit

Table 5.

Showing immune response against bacteriophages specific to Staphylococcus aureus in rabbit serum obtained at a different time interval

| Serum dilution | Day 0 | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage against Staphylococcus aureus [Phage dilution-10–2] | |||||||

| 10× | > 300 | > 300 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 100× | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1000× | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 |

| 2000× | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 | > 300 |

PFU Plaque forming unit

Fig. 1.

Neutralization of Escherichia coli specific phages with serum after immunization at different serum dilutions

Fig. 2.

Neutralization of Klebsiella pneumoniae specific phages with serum after immunization at different serum dilutions

Fig. 3.

Neutralization of Salmonella typhi specific phages with serum after immunization at different serum dilutions

Fig. 4.

Neutralization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa specific phages with serum after immunization at different serum dilutions

Fig. 5.

Neutralization of Staphylococcus aureus specific phages with serum after immunization at different serum dilutions

We examined the appearance of neutralizing antibodies at higher dilutions of the serum to delineate if the rise of titre is very high. On further dilution of rabbit serum to 1:100, the antibody against E. coli and P. aeruginosa could completely neutralize the phages on day 28. The antibody against S. typhi and S. aureus phages was able to neutralize completely on day 35 of the immunization. K. pneumoniae specific phage could not induce the sufficient antibody to show complete neutralization even on day 42. On the contrary, the PFU counts increased in the last week (6th) compared with 5th week from 5 to 28 CFU. A similar rise in CFU was observed when serum was diluted to 1:2000 especially against phage specific to E. coli (89 PFU to 102 PFU), K.pneumoniae (176 to > 300) S. aureus (340 PFU to 480 PFU) and S. Typhi (8PFU to 37 PFU) (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5; Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). P.aeruginosa specific phage did not show such a rise in PFU when serum was diluted to 1:2000 during the last two weeks of study.

We observed the rise of anti-phage neutralizing antibody in rabbit after bacteriophages administration irrespective of bacterial species reaching the highest levels usually after 4 weeks, at the serum dilution of both 1:10 and 1:100. This observation implies that the phage therapy outcome will not be affected when a short course of antibacterial treatment is required. Cases of acute septicaemia, pyogenic infections, bacterial pneumonia, acute urinary tract infection etc. may be treated effectively with phages without the risk of immune neutralization. However; based on the present study's observations, if phage therapy has to be continued beyond 3 weeks, the new lytic phages that are not neutralized by the patient's serum who has undergone the previous phage therapy may be picked up.

In a few preliminary reports rise in neutralizing antibody production against orally or parenterally administered phages with booster dosage have already been reported in guinea pig and rabbit model, but they have not looked for the duration when the serum from immunized animal caused complete neutralization of specific bacteriophage [22–24]. In another study in a murine bacteremia model by antibiotic-resistant P. aeruginosa and E. coli strains, an increase in anti-phage IgG levels was detectable on 10th day after administration 109 PFU of the respective phages [26, 27]. Orally administered single phage (E. coli phage T4) in mice showed that secretion of IgA in the gut lumen and IgG production in the blood but without correlating with the time required for complete neutralization [34]. It is intriguing to note that in a recent study of bacteriophage therapy in humans with Staphylococcus phage cocktail (MS-1) orally and locally, the majority did not lead a noticeably higher level of antiphage antibodies in their sera during phage administration. In a clinical study, anti-phage antibody titres were studied in 57 patients before and after phage therapy for different types of infections [16]. Even in those individual cases with an increased immune response, mostly by induction of IgG and IgM, the presence of antiphage antibodies did not translate into unsatisfactory clinical results of phage therapy. Our finding also shows the concordance with the studies mentioned above. A report has recently suggested that antiphage antibodies are not necessarily an obstacle to phage therapy implementation [29].

The decline in antiphase antibody

We noted that after 6 weeks of immunization, the titre of the neutralizing antibody dropped as the PFU count increased in all the cases excepting phage for P.aeruginosa. The initial IgM response was possibly dropped down in 6-week duration, and IgG response might have been switched on [18]. The IgG antibody is known for having less neutralizing activity. Moreover, another possibility could be that when the serum is highly diluted, both the immunoglobulins (IgG and IgM) becomes indetectable. This observation implies that the neutralizing antibody titre does not rise too high.

Anti phage antibody against commensal bacteria

The other significant observation was the presence of background neutralizing antibodies against phages of E. coli. Earlier studies have shown the presence of antiphage antibodies in sera of absolutely healthy individuals [29, 34, 35]. These so-called "natural antibodies" may result from the high prevalence of phages in nature, which are well known for their abundance in almost every environment [15]. E. coli being the commensal flora since birth in mammals might be inviting a lot of specific bacteriophages to flourish in the gut. This colonization might be leading to induction of neutralizing antibody formation. The absence of such background levels of antiphage antibody against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella Typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus implies that the bacteria mentioned above should not be considered as the part of commensal flora.

The humoral immune response against bacteriophages depends on various factors, i.e., route of administration, a dose of phage cocktail, the duration of the host's treatment, and immune status. Although phage therapy is rarely given through the subcutaneous route, we had chosen subcutaneous route for the ease of administration as earlier studies had shown the comparable immune response when protein antigens were given either intravenous or subcutaneous [36]. Further research questions that need to be addressed are (i) What were the different types of immunoglobulins induced after phage therapy, e.g. IgM, IgG, IgA? (ii) What was the number of phages circulating in blood after the appearance of the neutralizing antibody? (iii) If followed for long-duration, what is the longevity of these anti-phage antibody titres? (iv) What is the status and role of the cell-mediated immune response against these bacteriophages? (v) Are non-neutralizing antibodies being induced due to phage immunization? Thus many queries remain to be answered.

The rise in anti-phage neutralizing antibodies was observed 3 weeks after immunization. Complete neutralization of bacteriophages was found at the end of 3–5 weeks. Background (natural) anti-phage antibodies were observed against bacteriophage specific to E. coli in the rabbit serum. It was absent against other four bacteriophages specific to K. pneumoniae, S. Typhi, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Thus, our observation suggests that the same bacteriophage can be effectively used in acute bacterial infection. However, in cases of chronic infections transition to antigenically different bacteriophage cocktail may be recommended, usually, after three weeks.

Funding

No funding was provided as this study was the part of MD, Microbiology degree thesis work.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data and material will be made available whenever needed.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Institute Ethics Committee permission was taken (Letter no. Dean/2017/CAEC/246 dated 21.11.2017).

Consent for publication

We hereby agree to publish our article in the journal of Virus Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Belinda L, Sebastian L. A call for a multidisciplinary future of phage therapy to combat multi-drug resistant bacterial infections. Infect Microbe Dis. 2020;2:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zumla A, Rao M, Wallis RS, Kaufmann SH, Rustomjee R, Mwaba P, et al. Host-directed therapies for infectious diseases: current status, recent progress, and future prospects. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(4):e47–e63. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00078-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sybesma W, Pimay JP. Expert round table on acceptance and re-implementation of bacteriophage therapy. Silk route to the acceptance and re-implementation of bacteriophage therapy. Biotechnol J. 2016;11(5): 595–600. 10.1002/biot.201600023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bogovazova GG, Voroshilova NN, Bondarenko VM. The efficacy of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophage in the therapy of experimental Klebsiella infection. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1991;4:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakai T, Park SC. Bacteriophage therapy of infectious diseases in aquaculture. Res Microbiol. 2002;153(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park K, Cha KE, Myung H. Observation of inflammatory responses in mice orally fed with bacteriophage T 7. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;117(3):627–633. doi: 10.1111/jam.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith HW, Huggins MB, Shaw KM. Factors influencing the survival and multiplication of bacteriophages in calves and their environment. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1127–1135. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-5-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith HW, Huggins MB. The control of experimental Escherichia coli diarrhoea in calves by means of bacteriophage. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1111–1126. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-5-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith HW, Huggins MB. Effectiveness of phages in treating experimental E. coli diarrhoea in calves, piglets and lambs. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2659–2675. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-8-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith HW, Huggins MB. Successful treatment of experimental Escherichia coli infections in mice using phages: its general superiority over antibiotics. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:307–318. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-2-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soothill JS, Lawrence JC, Ayliffe GAJ. The efficacy of phages in the prevention of the destruction of pig skin in vitro by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Med Sci Res. 1988;16:1287–1288. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soothill JS. Treatment of experimental infections of mice by bacteriophage. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:258–261. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-4-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soothill JS. Bacteriophage prevents destruction of skin grafts by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Burns. 1994;20:209–211. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abedon ST, Kuhl SJ, Blasdel BG, Kutter EM. Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(2):66–85. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.2.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Górski A, Międzybrodzki R, Borysowski J, Dąbrowska K, Wierzbicki P, Ohams M, et al. Phage as a modulator of immune responses: practical implications for phage therapy. Adv Virus Res. 2012;83:41–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394438-2.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucharewicz-Krukowska A, Slopek S. Immunogenic effect of bacteriophage in patients subjected to phage therapy. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1987;35(5):553–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruttin A, Brüssow H. Human volunteers receiving Escherichia coli phage T4 orally: a safety test of phage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(7):2874–2878. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2874-2878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodyra-Stefaniak K, Miernikiewicz P, Drapała J, Drab M, Jończyk-Matysiak E, Lecion D, et al. Mammalian host-versus-phage immune response determines phage fate in vivo. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14802. doi: 10.1038/srep14802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furfaro LL, Payne MS, Chang BJ. Bacteriophage therapy: clinical trials and regulatory hurdles. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:376. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Belleghem JD, Dąbrowska K, Vaneechoutte M, Barr JJ, Bollyky PL. Interactions between bacteriophage, bacteria, and the mammalian immune system. Viruses. 2019;11:10. doi: 10.3390/v11010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krut O, Bekeredjian-Ding I. Contribution of the immune response to phage therapy. J Immunol. 2018;200(9):3037–3044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uhr JW, Finkelstein MS. Antibody formation. IV. Formation of rapidly and slowly sedimenting antibodies and immunological memory to bacteriophage phi-X 174. J Exp Med. 1963;117:457–477. doi: 10.1084/jem.117.3.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uhr JW, Finkelstein MS, Baumann JB. Antibody formation. III. The primary and secondary antibody response to bacteriophage phi X 174 in guinea pigs. J Exp Med. 1962;115:655–670. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.3.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha'jek P. Neutralization of bacterial viruses by antibodies of young animals. The development of the avidity of 19S and 7S neutralizing antibodies in the course of primary and secondary response in young rabbits immunized with PhiX 174 bacteriophage. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 1970;15:9–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02867042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stashak PW, Baker PJ, Roberso BS. The serum antibody response to bacteriophage phi chi 174 in germ-free and conventionally reared mice. I. Assay of neutralizing antibody by a 50 per cent neutralization method. Immunol. 1970;18:295–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang B, Hu B, Xu M, Yan Q, Liu S, Zhu X, Sun Z, Reed R, Ding L, Gong J, Li QQ, Hu J. Use of bacteriophage in the treatment of experimental animal bacteremia from imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:309–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Hu B, Xu M, Yan Q, Liu S, Zhu X, Sun Z, Reed R, Ding L, Gong J, Li QQ, Hu J. Therapeutic effectiveness of bacteriophages in the rescue of mice with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bacteremia. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biswas B, Adhya S, Washart P, Paul B, Trostel AN, Powel B, Carlton R, Merril CR. Bacteriophage therapy rescues mice bacteremic from a clinical isolate of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun. 2002;70:204–210. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.204-210.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Żaczek M, Łusiak-Szelachowska M, Jończyk-Matysiak E, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Międzybrodzki R, Owczarek B, Kopciuch A, Fortuna W, Rogóż P, Górski A. Antibody production in response to Staphylococcal MS-1 phage cocktail in patients undergoing phage therapy. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1681. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singla S, Harjai K, Katare OP, Chhibber S. Encapsulation of bacteriophage in liposome accentuates its entry into macrophage and shields it from neutralizing antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams MH. Bacteriophages. New York and London: Inter-science Publishers; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kropinski AM, Mazzocco A, Waddell TE, Lingohr E, Johnson RP. Enumeration of bacteriophages by double agar overlay plaque assay. In: Bacteriophages, 2009; pp. 69–76. Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Łusiak-Szelachowska M, Żaczek M, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Miedzybrodzki R, Klak M, Fortuna W, et al. Phage neutralization by sera of patients receiving phage therapy. Viral immunol. 2014;27(6):295–304. doi: 10.1089/vim.2013.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majewska J, Beta W, Lecion D, Hodyra-Stefaniak K, Kłopot A, Kaźmierczak Z, et al. Oral application of T4 phage induces weak antibody production in the gut and in the blood. Viruses. 2015;7(8):4783–4799. doi: 10.3390/v7082845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dąbrowska K, Miernikiewicz P, Piotrowicz A, Hodyra K, Owczarek B, Lecion D, Mierczak ZK, Letarov A, Gorski A. Immunogenicity studies of proteins forming the T4 phage head surface. J Virol. 2014;88(21):12551–12557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02043-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genovese MC, Covarrubias A, Leon G, Mysler E, Keiserman M, Valente R, et al. Subcutaneous abatacept versus intravenous abatacept: a phase IIIb noninferiority study in patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2854–2864. doi: 10.1002/art.30463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data and material will be made available whenever needed.