Abstract

This study was conducted to determine the changes in sexual functioning and alexithymia levels in patients with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. This descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted with 162 patients with type 2 diabetes. Data were collected using the Information Form, Toronto Alexithymia Scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. For 83.3% of the participants, there was a decrease in sexual functioning after diabetes, 69.8% after the COVID-19 pandemic, and 67.2% due to both conditions. The majority of the patients stated the reasons for experiencing sexual problems related to not seeing sexuality as a priority (77.1%), and stress/anxiety experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic (67.9%). Moreover, patients' alexithymia, anxiety, and depression levels were found to be high during the pandemic, when the study was conducted. A positive correlation was identified between alexithymia and anxiety and depression. Further, multiple regression results indicated that about 50% of alexithymia levels could be explained by anxiety and depression levels. The anxiety, depression, and alexithymia scores of those who had decreased sexual functioning before and during the pandemic period were statistically significantly higher than those who did not have any change (p < 0.01). During the COVID-19 pandemic when the study was conducted, high levels of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression were observed in participants, and it was found that their sexual functioning was negatively affected. Healthcare professionals should evaluate their patients in extraordinary situations such as epidemics and pandemics in terms of sexual functioning as well as other vital functions.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, COVID-19, Changes in sexual functioning, Alexithymia, Anxiety, Depression, Turkey

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide, and sexual dysfunction is one of the important comorbidities accompanying type 2 diabetes [1]. Men with type 2 report experiencing erectile dysfunction at a rate three times higher than their counterparts without diabetes (35–75%) [2, 3]. Other reasons for sexual dysfunction in these patients include ejaculatory dysfunction, low testosterone, hypogonadism, and sexual anorexia [4]. Sexual dysfunction is seen in 30–84% of women with type 2 diabetes, and it is associated with hypogonadism, dyspareunia, decreased sexual desire, and hormonal irregularity [2, 5].

In patients with type 2 diabetes, sexual dysfunction occurs due to many factors as well as psychological and social reasons [3]. Studies have shown that anxiety and depression are associated with sexual dysfunction in both men and women [6, 7]. The presence of psychological disorders increases sexual dysfunction [8, 9].

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) China office shared information about some pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in Wuhan City. The WHO later named this outbreak as the “Coronavirus disease 2019” (COVID-19). The rapid global spread of the disease led to the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [10]. As of December 29, 2020, there were 82,124,644 confirmed cases in the world, 58,107,717 people recovering, while 1,792,035 patients died due to the virus [11].

Since the date of the first virus-related (2019-nCoV) case notification, social, economic, and political arrangements have been made for preventive purposes both in Turkey and in many countries worldwide [10]. Within the scope of these measures, social isolation and quarantine practices restricted people's social lives [12].

The Covid-19 pandemic has had many physiological and psychological effects on individuals [13]. The rapid launch of the quarantine implementation caused a radical change in the lifestyle of the population [14]. Mass social isolation can result in problems with mental health in most people [12].

COVID-19 outbreak constituted a health threat for the whole population and created many physiological and psychological effects [15, 16]. In addition to high infectivity and fatality rates, COVID-19 has impacted psychological problems including anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders through various ways: fear of getting sick, restriction of social life, the economic loss caused psychological problems including anxiety, depression [17, 18]. Another psychological condition experienced during the pandemic is alexithymia [19]. Alexithymia is a mental health trait characterized by difficulty in understanding, defining, and expressing one's own emotions [20]. Individuals with alexithymia tend to think concretely and have symptoms such as difficulty in distinguishing between physical and emotional sensations [21]. Individuals with severe alexithymia cannot cognitively recognize and express their emotions [22]. Previous studies have found that traumatic situations experienced are associated with alexithymia [23–25].

Tang et al. detected severe alexithymia in individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. The decrease in emotion sharing due to social isolation, the stress and anxiety experienced can trigger alexithymia symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this period, alexithymia has become an important condition that threatens mental health [19]. Furthermore, alexithymia is more common especially in patients with diabetes than in non-diabetic individuals, and it even worsens glycemic control [26].

COVID -19 increases the number and severity of complications in patients with diabetes [27] The mortality rate of these patients due to COVID-19 is 7.3%, which is more than the non-diabetic patients [28]. Meta-analysis studies have shown that the mortality rate increases in COVID-19 patients with diabetes [27]. The presence of diabetes has been associated with a poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients. In the records of a local hospital in Wuhan, 15 (18.3%) of 82 patients who died due to COVID-19 were also reported to have diabetes. [29]. When the underlying diseases of 73% of infected male patients were examined, it was seen that 20% were diabetic [30] In the literature, the relationship of diabetes with adverse outcomes such as intensive care admission, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation, and mortality in COVID-19 disease has been stated. Fear of death and catching the disease causes stress and anxiety in patients with type 2 diabetes [31]. Th authors consider that this situation will cause alexithymia in individuals with diabetes and may affect sexual functioning. Studies have shown that alexithymia is common in patients with sexual dysfunction [32] and that erectile dysfunction is associated with alexithymia [33, 34]. However, the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic process and sexual dysfunction in diabetic patients with alexithymia is unknown.

With the WHOs' official declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, people's social lives and sexual health and behavior have also changed [35]. Sexual life is the most affected area for people during the pandemic [36]. No study has examined the change in the sexual functioning of individuals with diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the relationship between this condition, alexithymia, anxiety, and depression. This study will contribute to closing this gap in the literature.

Purpose of the Study

This study was conducted to investigate the change in sexual functioning of patients with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic and to determine the relationship between this change and anxiety, depression, and alexithymia. In alignment with this purpose, the following questions are researched:

Is there a change in the sexual functioning of patients with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What are the levels of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression of patients with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic, and is there a relationship between them?

Is there a difference between patients who developed sexual dysfunction during and before the COVID-19 pandemic and those who did not in terms of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression?

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This descriptive and cross-sectional study was conducted with type 2 diabetes patients during the COVID -19 pandemic between May 21 and July 5, 2020. in Istanbul, Turkey.

Sample

The study consisted of volunteers who were at least 18 years of age, were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and were literate. A simple random sampling method performed by a computer was used in selecting the participants from 3000 people who had been admitted to the Research and Training Hospital Diabetes Polyclinic before the pandemic period and whose information was available in the hospital automation system. The computer program enumerates the items in the sampling frame, determines its random numbers, and presents the selected items to the researcher in writing or digitally [37]. Electronic medical records of the patients were examined and those with psychiatric diseases (depression, mania, psychosis, obsessive–compulsive disorder, etc.), mental retardation, dementia, and Alzheimer's were not included in the study. Moreover, the information form included the question of the presence of existing psychiatric and neurological diseases. If these diagnoses were reported by the patient, the patient was excluded from the study.

To determine the sample size, a power analysis was conducted in the G-Power 3.1 program by taking into consideration the values of the data obtained from a similar study in the literature [38]. The required sample size [alpha] at an effect size of 0.5 and an error level of 0.05 was determined as 165. The strength of the analysis with this sample size was found to be 90.2%. Three people were excluded from the study as they did not fill in the questionnaire completely. The study was completed with 162 people.

Procedure

Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Istanbul Medeniyet University Göztepe Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee for Clinical Research (Approval number: 2020\0225). Participants were invited to the study via the internet and telephone. Participants wishing to participate in the study were informed about study objectives, procedures, and data privacy. They were told participation was voluntary, and they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants read and approved the consent forms online. The study was conducted in compliance with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects of the Helsinki Declaration. Data collection forms were created using SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey.com), which provides electronic self-control and facilitates data collection and tracking by preventing multiple data entries from the same person. (SurveyMonkey-SurveyDevelopment Software http://www.surveymonkey.com). Confidentiality was guaranteed by completely deactivating electronic records and IP address records.

Data Collection

Data were collected using the Information Form, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS).

Information Form

The information form created by the researchers was prepared in line with the literature [38, 39]. The form includes questions about socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status), number of chronic diseases other than diabetes, duration of diabetes, HbA1c level in the last 3 months, and sexual functioning. Questions on sexual functioning addressed the change in sexual desire, change in sexual functioning, change in frequency of sexual intercourse, change in sexual satisfaction level, and change in the duration of sexual intercourse. The response options provided for these questions included 'decreased after the COVID-19 pandemic, increased after the COVID-19 pandemic, no change occurred in sexual functioning, decreased after diabetes, and increased after diabetes.' At the same time, there were questions on whether they had a sexual partner, the effects of sexual change on mood, difficulty in discussing sexual problems with a health care professional, whether the change in sexual functioning was resolved, and the reasons for sexual problems. People could select more than one option.

HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale)

HADS is a self-report questionnaire designed to screen the symptoms of anxiety and depression in individuals with medical diseases other than psychiatric illnesses. It was developed by Zigmond and Snaith [40], and its Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Aydemir et al. [41]. The scale addresses symptoms such as tension, anxiety, fear, panic, difficulty in relaxation, and restlessness [40].

The 4-point Likert-scale consisting of 14 items has 2 sub-dimensions, which are Anxiety (HADS-Anxiety) and Depression (HADS-Depression). Each sub-dimension contains 7 items. The score given to each question varies between 0–3. Scores for HADS- Anxiety and HADS- Depression are added and evaluated separately. If the score obtained from each sub-dimension is between 0–7, it indicates a normal situation, if it is between 8–10, it indicates the border state, and if it is 11 and above, it indicates high (abnormal situation). Cronbach's alpha value was found to be 0.85 for the anxiety sub-dimension and 0.78 for the depression sub-dimension by Aydemir et al. [41]. In this study, it was found to be 0.89 for the anxiety sub-dimension and 0.81 for the depression sub-dimension.

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS)

The scale developed by Bagby et al., consisting of 20 questions [22]. Its Turkish validity and reliability study was performed by Gulec et al. [42]. This scale evaluates the status of alexithymia, which is defined as the lack of self‐emotion and excitement. This 5-point Likert scale includes the answers "Never", "Rarely", "Sometimes", "Often" and "Always". The scale has a subscale. The Difficulty in Recognizing Emotions subscale consists of seven items (items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 13, and 14), which is defined as difficulty in identifying emotions and distinguishing them from bodily sensations accompanying emotional arousal. Besides, the Difficulty in Speaking Emotions subscale consists of five items (items 2, 4, 11, 12, and 17), which is defined as a difficulty in transferring emotions to others. Obtaining high scores on the scale indicates that there is difficulty in expressing feelings. The lowest score that can be obtained from the scale is 20, and the highest score is 100. A total score of 51 and below indicates a normal status, a score of between 52 and 60 points at a possible alexithymia condition, and a score of 61 and above refers to alexithymia [43]. The Cronbach's alpha value of the Turkish version developed by Gulec is 0.78, and for this study, it was found to be 0.79.

Statistical Analysis

Data were assessed by using the SPSS 15.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess whether the data had a normal distribution. In data analysis, average, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were used for calculations. Independent groups t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare ages, durations of diabetes, HADS-Anxiety and HADS-Depression Scale and Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) scores of those who had decreased sexual functioning and those who did not have any change before and during the pandemic. In comparing the dichotomy and categorical data of patients with and without a decrease in sexual functioning, the Pearson's Chi-squared test was implemented. In analyzing the relationship between the levels of anxiety, depression, and alexithymia, the Spearman correlation test was used. The effects of alexithymia on anxiety and depression levels were evaluated using multiple regression analysis. The data were evaluated at the significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the 162 type 2 diabetes patients participating in the study was 56.33 years (± 13.44), and 55.6% of the participants were female, 80.2% were married and 31.5% were primary education graduates. The majority (56.7%) had another chronic disease in addition to diabetes. Participants’ mean diabetes duration was 9.06 years (± 4.02), and the HbA1c mean was 9.40 ± 2.2 Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and disease-related characteristics of diabetes patients (N: 162)

| Variables | Mean ± SD (Min Max) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.33 ± 13.44 (21- 89) | |

| 25–35 | 11.1 | |

| 35–45 | 16 | |

| 45–55 | 30.2 | |

| 65 and above | 42.5 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 55.6 | |

| Male | 44.4 | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 80.2 | |

| Single | 19.8 | |

| Education Level | ||

| Primary education | 31.5 | |

| High school | 30.2 | |

| University | 24.1 | |

| Master's | 14.2 | |

| Presence of chronic disease(s) in addition to diabetes | ||

| Yes | 56.7 | |

| No | 43.2 | |

| Number of chronic diseases in addition to diabetes | 1.8 ± 0.6 (1–6) | |

| Duration of diabetes (year) | 9.06 ± 4.02 (1–39) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 9.40 ± 2.26 (5–14) | |

Research Question 1: Change in Sexual Functioning

While there was no difference in HbA1C and duration of diabetes between those with and without decreased sexual functioning (p > 0.05), there was a gender difference (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with diabetes in terms of sexual functioning

| Variables | Decrease in pre-pandemic sexual functioning | Decrease in sexual functioning during the pandemic | Decrease in sexual functioning due to both Diabetes and Covid-19 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease | No Change | Test Value | Decrease | No Change | Test Value | Decrease | No Change | Test Value | |

| Age | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 56.36 ± 11.22 | 56.18 ± 12.23 | bp < .05** | 56.45 ± 13.02 | 56.06 ± 13.58 | bp < .05** | 56.66 ± 12.96 | 57.05 ± 13.98 | bp < .05** |

| Gender % | |||||||||

| Female | 74 (54.8) | 16 (59.3) | bp < .05** | 66 (58.4) | 24 (49) | bp < .05** | 63 (57.8) | 12 (48) | bp < .05** |

| Male | 61 (45.2) | 11 (40.7) | 47 (41.6) | 25 (51) | 46 (42.2) | 13(52) | |||

| Duration of Diabetes | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.11 ± 4.85 | 8.98 ± 4.56 | bp < .05** | 9.56 ± 5.58 | 7.91 ± 3.45 | bp < .05** | 9.81 ± 2.58 | 7.02 ± 3.15 | bp < .05** |

| HbA1c (%) | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | 9.48 ± 2.31 | 9.39 ± 2.03 | bp < .05** | 9.51 ± 2.31 | 9.36 ± 2.17 | bp < .05** | 9.51 ± 2.35 | 9.35 ± 2.11 | bp < .05** |

bMann–Whitney U Test **p < 0.05

According to their statements, 82.7% of the participants had sexual partners. For 83.3% of the participants, there was a decrease in sexual functioning after diabetes, 69.8% after the COVID-19 pandemic, and 67.2% due to both conditions. No patient reported an increase in sexual functioning. As stated, 83.3% of the participants had a decrease in sexual desire, 82.1% in the frequency of sexual intercourse, 80.2% in the level of sexual intercourse satisfaction, and 79.6% in the duration of sexual intercourse before the pandemic, that is, after the diagnosis of diabetes. For 69.8% of the participants, there was a decrease in sexual desire, 67.9% in the frequency of sexual intercourse, 67.9% in sexual satisfaction level, and 67.3% in the duration of sexual intercourse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The majority of participants stated the reasons for sexual problems during the COVID-19 pandemic were not considering sexuality as a priority (77.1%) and stress/anxiety experienced during the pandemic (67.9%). Most of the participants (81.5%) stated that they had difficulty in discussing the change in sexual functioning with healthcare staff. Furthermore, only 22.2% of the participants reported that they could find a solution to the change in sexual functioning, and 66.7% of them stated that the change in sexuality affected their mood (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of diabetes patients related to sexual functions (N: 162)

| Variables | % |

|---|---|

| Sexual partner | |

| Yes | 82 |

| No | 17.3 |

| Change in sexual function* | |

| Decreased before the COVID-19 pandemic | 83.3 |

| Decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic | 69.8 |

| No Change | 14.8 |

| Change in sexual desire * | |

| Decreased before the COVID-19 pandemic | 83.3 |

| Decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic | 69.8 |

| No Change | 17.3 |

| Change in frequency of sexual intercourse * | |

| Decreased before the COVID-19 pandemic | 82.1 |

| Decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic | 67.9 |

| No Change | 20.3 |

| Change in sexual satisfaction level * | |

| Decreased before the COVID-19 pandemic | 80.2 |

| Decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic | 67.9 |

| No Change | 21.60 |

| Change in the duration of sexual intercourse* | |

| Decreased before the COVID-19 pandemic | 79.6 |

| Decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic | 67.3 |

| No Change | 17.9 |

| Reason for having sexual problems * | |

| Not considering sexuality as a priority | 77.1 |

| Stress/anxiety experienced during the COVID- 19 pandemic | 67.9 |

| Fear of COVID-19 disease transmission | 50 |

| Unwillingness of the sexual partner | 33.3 |

| Physical complaints | 25.9 |

| Reporting changes in sexual functions to healthcare staff | |

| Yes | 18.5 |

| No | 81.5 |

| Finding solutions to changes in sexual functions | |

| Yes | 22.2 |

| No | 77.8 |

| The change in sexuality affecting the mood | |

| Yes | 66.7 |

| No | 33.3 |

*More than one option was selected

Research Question 2: Alexithymia, Anxiety and Depression Scores

The mean TAS score of the participants was 76.92 ± 0.76. A score of 61 and above suggests the presence of alexithymia. Participants’ mean HADS-Anxiety score was 10.54 ± 4.32 (1–21), and their mean HADS-Depression score was 8.08 ± 4.46. The fact that HADS-Anxiety and HADS-Depression mean scores are between 8 and 10 demonstrates the presence of borderline anxiety and depression levels. When the relationship between HADS-Anxiety, HADS-Depression, and TAS levels was examined, a positive significant correlation was found between the means of anxiety and depression scores (r = 0.823, p = 0.005). A positive relationship was found between both anxiety and alexithymia (r = 0.702, p = 0.041) and depression (r = 0.896, p = 0.003). Furthermore, in the multiple regression analysis, it was observed that the alexithymia scores of the patients were affected by 50% of their anxiety and depression levels (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of variables affecting alexithymia level (N = 162)

| Independent variables | B | Standard Error | Standard Beta (β) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 32.245 | 3.165 | – | 10.187 | p < 0.01 |

| HADS-anxiety | 4.823 | 0.451 | 0.966 | 10.700 | p < 0.01 |

| HADS-depression | – 2.203 | 0.543 | – 0.366 | – 4.057 | p < 0.01 |

Dependent Variable: Toronto Alexithymia Scale R: .503 Adjusted R2: .509 F: 82.544

Research Question 3: Changes in Sexual Functioning and Alexithymia Anxiety and Depression Levels

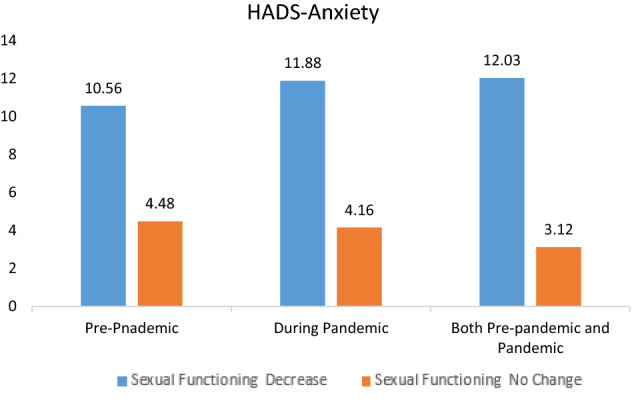

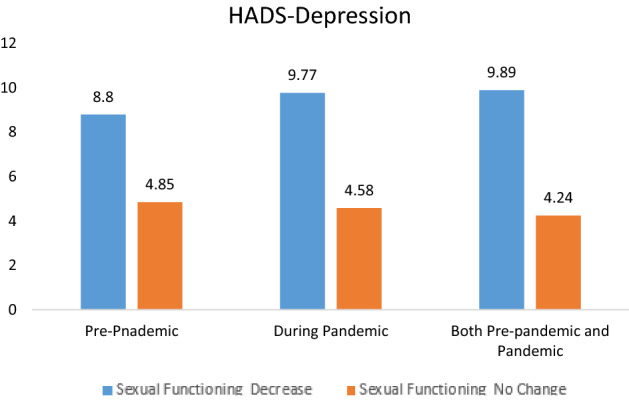

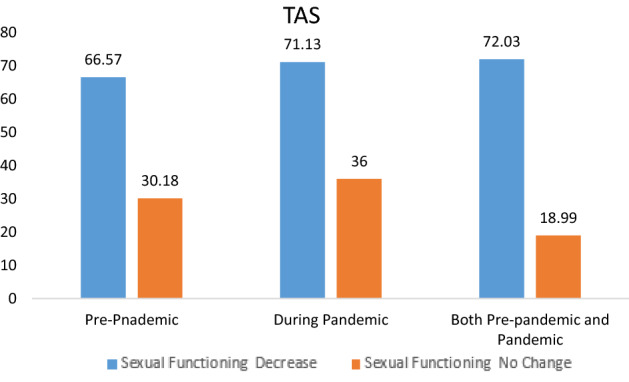

When compared with those with decreased sexual functioning due to diabetes, COVID-19, and both, it was found that the HADS-Anxiety (Fig. 1), HADS-Depression (Fig. 2), TAS scores (Fig. 3) of those with decreased sexual functioning were statistically significantly higher. (p < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the anxiety levels of patients with diabetes in terms of sexual functioning

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the depression levels of patients with diabetes in terms of sexual functioning

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the alexithymia levels of patients with diabetes in terms of sexual functioning

Discussion

In this study examining the change in sexual functioning of patients with type 2 diabetes during COVID-19, it was found that participants had high levels of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression, and their sexual functioning was negatively affected.

Change in Sexual Functioning

Results suggest the vast majority of participants (83.3%) experienced a decline in sexual functioning after diabetes, 69.8% after the COVID-19 pandemic, and 67.2% due to both conditions. Although sexual dysfunction is common in individuals with diabetes [3], it is seen that this situation has become more prominent during the pandemic [17]. In previous mass disasters, it was reported that there was a significant decrease in the sexual behaviors of people, the frequency of sexual intercourse, and the degree of satisfaction with their sexual life [44]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, factors such as quarantine implementation, children not going to school and difficulty in finding a moment of intimacy, fear of infection, and the need to maintain physical distance have affected people's sexual lives [45]. Additionally, it was reported in the literature that the virus was transmitted via fecal–oral route [46] and that couples reduced all the contact from simple kissing to full sexual intercourse due to the fear of transmitting the disease to each other [45]. In light of this information, a decrease in sexual functioning is expected in individuals with diabetes. However, no studies investigating the sexual functioning of diabetics during the COVID-19 pandemic were found. Besides, the fact that a significant portion of the patients (42.5%) in our study were 65 years of age or older is thought to be related to the high rate of decrease in sexual functioning both in the pre-pandemic period and during the pandemic. This is because sexual dysfunctions are associated with age in diabetes [39]. In addition, the HbA1c levels of the patients in our study being 9.40 ± 2.26, and the mean duration of diabetes being 9.06 ± 4.02 years are thought to increase sexual dysfunction. In their study, Amar et al. stated that there was a positive correlation between sexual dysfunction and the duration of diabetes [39, 47]. According to the results of a meta-analysis, diabetes duration and the HbA1c level directly affect sexual dysfunction in diabetes [5].

Keeping and sustaining sexual desire and willingness alive during the pandemic is one of the most important challenges that couples face [45]. In the literature, it has been stated that couples' emotional bonds were weakened during the COVID-19 period [45, 48]. In this study, it was found that sexual desire, frequency of intercourse, level of satisfaction in sexual intercourse, and duration of intercourse significantly decreased in participants due to both diabetes and the pandemic process. It is thought that the reasons for this may be the obligation to share every moment during the day and the restriction of people's own space.

In addition, when the reasons why diabetic patients had sexual problems were investigated in this study, it was found that the first reason was not considering sexuality as a priority (77.1%) during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the second was stress/anxiety (67.9%) experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has a more severe course in individuals with chronic diseases compared to the healthy population [49]. Case fatality rates for patients with comorbid disease are numerically higher than the average population, and diabetes is in the high-risk group [28]. However, according to reports from China [50] and Italy [51], especially elderly patients with chronic diseases including diabetes, were at higher risk for severe COVID-19 and mortality. The fact that the population included in the study had both diabetes and a high proportion of individuals aged 65 and above explains that the individuals do not consider sexuality as a priority during the COVID-19 pandemic and that people experience anxiety in this period.

In this study, 81.5% of the participants reported that they did not discuss the change in sexual functioning with healthcare staff. The proportion of participants who found a solution to the change in sexual functioning was only 22.2%. Since both COVID-19 [45] and diabetes [3] affect the sex lives of people, it is important for healthcare professionals to monitor patients. Diabetic patients do not share their sexual problems with healthcare professionals because they are embarrassed. They think that healthcare professionals will not be interested in this issue. They feel insecure while explaining themselves, and they consider this issue unnecessary [52]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is expected that patients do not consult healthcare professionals because hospitals are risky areas for infection. However, the healthcare team's support to patients about possible sexual problems and treatment options that may arise during the course of diabetes and COVID-19 pandemic is important for patients to maintain their sexual health during this period. This is because sexuality should be seen as a vital activity such as movement, eating and drinking, and breathing and should be evaluated routinely by healthcare staff. People's concerns about COVID-19 and sexuality should be reduced. There are studies in literature showing that sex, kissing, and touching are not harmful to people who have sexual partners and are not infected with COVID-19 [45].

Individuals with type 2 diabetes are at risk of sexual dysfunction due to diabetes. It is important to evaluate people with diabetes in terms of sexual function Extraordinary situations such as pandemics affect people with diabetes, as well as all individuals. Thus, extra care might need to be taken to meet their needs should additional dysfunction emerge during the pandemic. It is necessary to approach and evaluate people with diabetes looking more holistically. Sharing information about diabetes and its complication with patients will be beneficial to reduce the concerns of patients on this issue. Informing patients through online interviews during the quarantine periods may be possible.

Alexithymia, Anxiety and Depression Levels

COVID-19 pandemic has caused many physiological and psychological changes in people [19]. The uncertainty of how long the pandemic will last and what it may lead to, the fear that the disease will be transmitted to the person or his family, the unreliable assessment of the place of residence in terms of infection creates fear and stress in people and causes anxiety and depression [12, 53]. In a study conducted with 4872 participants above the age of 18 in Wuhan, it was found that the rate of depression was 48.3%, the rate of anxiety was 22.6%, the rate of depression and anxiety was 19.4% during the COVID-19 outbreak [54]. In studies conducted with patients with diabetes, it was found that anxiety and depression were observed at a high rate during the COVID-19 pandemic [55, 56]. Similar to the literature, in this study, anxiety, and depression symptoms were observed with a high rate in participants.

Another psychological condition experienced during the pandemic is alexithymia [19]. Tang et al. detected severe alexithymia in people during the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. In this study, it was determined that diabetes patients had a high rate of alexithymia. Moreover, in this study, a significant positive correlation was found between alexithymia, anxiety, and depression. Studies in the literature also show that the level of alexithymia is high in diabetic patients and that there is a positive correlation between alexithymia, anxiety, and depression. [57–59]. In the literature, no studies were found investigating the alexithymia levels of individuals with type 2 diabetes and the relationship between anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors consider that this study will contribute to filling the gap in the literature.

Alexithymia, Anxiety, and Depression Levels with a Change in Sexual Functioning

Psychological factors affect people's sexual health and behavior. It is stated in the literature that anxiety and depression affect the decrease in sexual desire [60, 61]. Negative emotions affect sexual functioning negatively [45]. Additionally, it has been reported in the literature that people with sexual dysfunction have higher levels of alexithymia [61]. In this study, it was found that those with decreased sexual functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic had higher levels of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression than those who did not. T)he anxiety, depression, and alexithymia scores of those who had decreased sexual functioning before and during the pandemic period were significantly higher than those who did not have any change. These findings are similar to the literature.

In literature there are studies showing that sexual dysfunction can be seen in diabetic patients who are at serious risk of complications due to COVID-19, and this should be investigated [62]. This study investigated the sexual dysfunction associated with COVID-19 in the population with type 2 diabetes and examined the level of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression. It is important to evaluate people with diabetes in terms of alexithymia, anxiety, depression, and sexual functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological intervention programs can be developed for this purpose. Besides, in terms of alexithymia, people with diabetes can be directed to online interviews to understand and express their feelings. Healthcare staff should support people during the COVID-19 pandemic both physiologically and psychologically in order to protect and maintain sexual health.

Limitations of the Study

There are several limitations to this study. One of them is the evaluation of sexual functioning according to patients' self-reports. A structured scale was not used to assess change in sexual functioning. The cross-sectional design of the study limited the ability to make inferences about the causality aspects of sexual functioning change. No comparison was made with a non-diabetic control group. Another limitation is that the results of the study reflect only Turkish culture and cannot be generalized to other cultures. Comparative studies in larger populations are needed.

Conclusion

As a result, sexual dysfunction, which is common in patients with type 2 diabetes, became more prominent during the pandemic. Anxiety, depression, and alexithymia increased in people during the pandemic, and all these contributed to the development of sexual dysfunction. Most of the patients reported that they had difficulty in talking to healthcare staff about sexual problems and finding solutions to sexual problems. During the pandemic period, interventions aimed at improving mental health and reducing concerns about sexuality should be planned for specific patient populations.

Healthcare professionals may help patients with issues related to sexual functioning. The most important step is to ask if they have sexual health problems, would like to discuss these issues further, and would like information or referrals for help [63]. Healthcare professionals view sexual functions as vital functions such as movement, eating, and breathing, and this problem is easily resolved if they evaluate patients as holistic in terms of these functions. In addition, patients with diabetes can be evaluated in terms of sexual dysfunction by telehealth methods during the pandemic period. Healthcare professionals should evaluate their patients in extraordinary situations such as epidemics and pandemics in terms of sexual functioning as well as other vital functions.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the participants of this study. The authors did not accept any funding from public or private facilities for performing this study.

Author’s Contribution

The authors have confirmed that all of the authors meet the IC-MJE criteria for authorship credit (www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html), as follows: (BD, AO and EYA) making substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; (BD, AO and EYA) data collection, data analysis and manuscript writing; (BD, AO and EYA) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No restrictions and no conflict of interest. This manuscript and the content of this manuscript have not been published elsewhere. The study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the İstanbul Medeniyet University GEAH Training and Research Hospital (Approval number: 2020\0225).

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Berna Dincer, Email: berna.dincer@medeniyet.edu.tr.

Elif Yıldırım Ayaz, Email: drelifyildirim@hotmail.com.

Aytekin Oğuz, Email: aytekinoguz@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Tamás V, Kempler P. Sexual dysfunction in diabetes. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014;126:223–232. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53480-4.00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Esposito K. Diabetes and sexual disorders. Diabetes Complicat., Comorbidities, Relat. Disord. 2020;42:473–494. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36694-0_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Esposito K. Diabetes and sexual dysfunction: current perspectives. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2014;7:95–105. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S36455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amidu N, Owiredu WKBA, Gyasi-Sarpong CK, Alidu H, Antuamwine BB, Sarpong C. The inter-relational effect of metabolic syndrome and sexual dysfunction on hypogonadism in type II diabetic men. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2017;29(3):120–125. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2017.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahmanian E, Salari N, Mohammadi M, Jalali R. Evaluation of sexual dysfunction and female sexual dysfunction indicators in women with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019;11(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13098-019-0469-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basson R, Gilks T. Women’s sexual dysfunction associated with psychiatric disorders and their treatment. Women’s Health. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1745506518762664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, Rosenbaum T, Abdo C, Byers ES, Graham C, Nobre P, Wylie K. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2016;13(4):538–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bąk E, Marcisz C, Krzemińska S, Dobrzyn-Matusiak D, Foltyn A, Drosdzol-Cop A. Relationships of sexual dysfunction with depression and acceptance of illness in women and men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14(9):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erden S, Kaya H. Sexual dysfunction and anxiety levels of type 2 male diabetics. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2015;28(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. 2020. WHO characterizes COVID-19 as a pandemic. World Heatlh Organization. www.who.int/emergencies (Accessed December 29, 2020).

- 11.www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-cases. (Accessed December 29, 2020).

- 12.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China . Psychol. Health Med. 2020;26(13):22. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aktug ZB, Iri R, Aktug Demir N. COVID-19 immune system and exercise. J. Human Sci. 2020;17(2):513–520. doi: 10.14687/jhs.v17i2.6005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siyu, C., Xia, M., Wen, W., Cui, L., Yang, W., Liu, S. et al.: Mental health status and coping strategy of medical workers in China during The COVID-19 outbreak. In medRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press (2020). https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.23.20026872

- 16.Huang, L., Xu, F. M., Liu, H. R.: Emotional responses and coping strategies of nurses and nursing college students during COVID-19 outbreak. In medRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.05.20031898

- 17.Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lahiri D, Lavie CJ. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(5):779–788. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohde C, Hougaard Jefsen O, Nørremark B, Aalkjær Danielsen A, Østergaard SD. Psychiatric symptoms related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2020 doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang W, Hu T, Yang L, Xu J. The role of alexithymia in the mental health problems of home-quarantined university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Personal Individ. Differ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beyens I, Frison E, Eggermont S. “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, facebook use, and facebook related stress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;64:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caretti V, Porcelli P, Solano L, Schimmenti A, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. Reliability and validity of the Toronto Structured Interview for Alexithymia in a mixed clinical and nonclinical sample from Italy. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(3):432–436. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagby M, Taylor GJ, Ryan D. Toronto Alexithymia scale: relationship with personality and psychopathology measures. Psychother. Psychosom. 1986;45(4):207–215. doi: 10.1159/000287950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westwood H, Kerr-Gaffney J, Stahl D, Tchanturia K. Alexithymia in eating disorders: systematic review and meta-analyses of studies using the Toronto Alexithymia scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017;99:66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karsikaya S, Kavakci O, Kugu N, Guler AS. Migren hastalarında travma sonrası stres bozuklugu: migren, travma ve aleksitimi. Noropsikiyatri Arsivi. 2013;50(3):263–268. doi: 10.4274/npa.y6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franzoni E, Gualandi S, Caretti V, Schimmenti A, Di Pietro E, Pellegrini G, Pellicciari A. The relationship between alexithymia, shame, trauma, and body image disorders: investigation over a large clinical sample. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2013;9:185. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S34822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Topsever P, Filiz TM, Salman S, Sengul A, Sarac E, Topalli R, Gorpelioglu S, Yilmaz T. Alexithymia in diabetes mellitus. Scott. Med. J. 2006;51(3):15–20. doi: 10.1258/RSMSMJ.51.3.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P, Anikhindi SA, Bansal N, Singla V, Khare S, Srivastava A. Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID-19? a meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020;14(4):535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Cardiology. COVID-19 clinical guidance for the cardiovascular care team. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 1, 1-4 (2020).

- 29.Zhang B, Zhou X, Qiu Y, Song Y, Feng F, Feng J, Wang J. Clinical characteristics of 82 cases of death from COVID-19. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0235458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Yu T. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joensen LE, Madsen KP, Holm L, Nielsen KA, Rod MH, Petersen AA, Rod NH, Willaing I. Diabetes and COVID-19: psychosocial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in people with diabetes in Denmark—what characterizes people with high levels of COVID-19-related worries? Diabet. Med. 2020;37(7):1146–1154. doi: 10.1111/dme.14319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wise TN, Osborne C, Strand J, Fagan PF, Schmidt CW. Alexithymia in patients attending a sexual disorders clinic. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(5):445–450. doi: 10.1080/00926230290001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madioni F, Mammana LA. Toronto alexithymia scale in outpatients with sexual disorders. Psychopathology. 2001;34(2):95–98. doi: 10.1159/000049287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mnif L, Damak R, Mnif F, Ouanes S, Abid M, Jaoua A, Masmoudi J. Alexithymia impact on type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a case-control study. Annales d’Endocrinologie. 2014;75(4):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott-Sheldon LA, Mark KP, Balzarini RN, Welling LL. Call for proposals: Special issue of archives of sexual behavior on the impact of COVID-19 on sexual health and behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01725-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman I, Benz CR. Qualitative-quantitative research methodology: exploring the interactive continuum. New York: SIU Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tazik S, Madani Y, Gholamali Lavasani M, Besharat M. Examining the moderating effect of alexithymia on the relationship between emotional schemas and sexual dysfunctional beliefs in women and men with diabetes. J. Psychol. Sci. 2017;16(62):238–250. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiferaw WS, Akalu TY, Petrucka PM, Areri HA, Aynalem YA. Risk factors of erectile dysfunction among diabetes patients in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2020;32:100232. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2020.100232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aydemir Ö. Validity and reliability of Turkish version of hospital anxiety and depression scale. Turk Psikiyatr Derg. 1997;8(4):280–287. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gulec H, Kose S, Gulec MY, Citak S, Evren C, Borckardt J, Sayar K. Reliability and factorial validity of the Turkish version of the 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS-20) Clin. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2009;19(3):214. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craparo G, Faraci P, Gori A. Psychometric properties of the 20-item toronto alexithymia scale in a group of Italian younger adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2015;12(4):500–507. doi: 10.4306/pi.2015.12.4.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu S, Han J, Xiao D, Ma C, Chen B. A report on the reproductive health of women after the massive 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010;108:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibarra FP, Mehrad M, Mauro MD, Godoy MFP, Cruz EG, Nilforoushzadeh MA, Russo GI. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual behavior of the population. the vision of the east and the west. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2020;46:104–112. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.s116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. Novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ammar M, Trabelsi L, Chaabene A, Charfi N, Abid M. Evaluation of sexual dysfunction in women with type 2 diabetes. Sexologies. 2017;26(3):17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2016.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cocci A, Presicce F, Russo GI, Cacciamani G, Cimino S, Minervini A. How sexual medicine is facing the outbreak of COVID-19: experience of Italian urological community and future perspectives. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2020;14:1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41443-020-0270-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, Li C, Ai Q, Lu W, Liang H, Li, Si.He J. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui D, Du B, Li LJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rutte A, Welschen LM, Van Splunter MM, Schalkwijk AA, de Vries L, Snoek FJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes patients’ needs and preferences for care concerning sexual problems: a cross-sectional survey and qualitative interviews. J. Marital Ther. 2016;42(4):324–337. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2015.1033578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma S, Sharma M, Singh G. A chaotic and stressed environment for 2019-nCoV suspected, infected and other people in India: fear of mass destruction and causality. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51:102049. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Fu H, Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):0231924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alzahrani A, Alghamdi A, Alqarni T, Alshareef R, Alzahrani A. Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among patients with type II diabetes attending primary healthcare centers in the western region of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst. 2019;13(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khan P, Qayyum N, Malik F, Khan T, Khan M, Tahir A. Incidence of anxiety and depression among patients with Type 2 diabetes and the predicting factors. Cureus. 2019 doi: 10.7759/cureus.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shayeghian Z, Moeineslam M, Hajati E, Karimi M, Amirshekari G, Amiri P. The relation of alexithymia and attachment with type 1 diabetes management in adolescents: a gender-specific analysis. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00396-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martino G, Bellone F, Langher V, Caputo A, Catalano A, Quattropani MC, Morabito N. Alexithymia and psychological distress affect perceived quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019 doi: 10.6092/2282-1619/2019.7.2328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fares C, Bader R, Ibrahim JN. Impact of alexithymia on glycemic control among Lebanese adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2019;18(1):191–198. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00412-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mieras M. Seksuele lust, de hersenen en ons lichaamsbewustzijn [Sexual desire, the brain and our interoceptive consciousness] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2018;162:2758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nimbi FM, Tripodi F, Rossi R, Simonelli C. Expanding the analysis of psychosocial factors of sexual desire in men. J. Sex. Med. 2018;15(2):230–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.11.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69, 343–6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Barbera L, Zwaal C, Elterman D, McPherson K, Wolfman W, Katz A, Matthew A. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2017 doi: 10.3747/co.24.3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]