Abstract

The present work describes the preparation of bivalent Ni(II), Co(II) and Cu(II) complexes of [(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene]amino]thiourea (MTHC) by mixing in 1:2 ratio of corresponding metal salt and Schiff base ligand in ethanolic medium. The prepared ligand and its complexes are confirmed using elemental analysis, magnetic moments, FT-IR, NMR, electronic and ESR spectroscopy techniques. The spectroscopic data reveals that metal complexes are in square planar in nature. In DNA binding studies, the higher intrinsic binding constants (Kb) of Ni(II), Co(II) and Cu(II) complexes are 2.713 × 106 M−1, 5.529 × 106 M−1 and 2.950 × 106 M−1 respectively, evident that complexes are avid binder with DNA base pairs. The moderate anti-bacterial activity (in-vitro) against staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli bacterial culture may be due to the high electron density of ligand which prevents the charge reduction of metal ion. In the presence and absence of H2O2, it is notified that there is no appreciable DNA cleavage activity of Ni(II) and Co(II) complexes except Cu(II) complex which is due to aprotonation in the medium.

Keywords: [(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene]amino]thiourea; Transition metal complexes; DNA interactions And antibacterial activity

[(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene]amino]thiourea, transition metal complexes, DNA interactions and antibacterial activity.

1. Introduction

Aromatic hetero cyclic thiazole compound containing nitrogen and sulphur cause to act as a nucleophile. This nuleophilic characteristic of the molecule accentuates the scientists to employ in the synthesis of not only drugs like Sulfthiazol, Abafungin, Tiazofurin, Agrochemicals but also in Cosmetics and Liquid crystals. Thiazoles exist in coenzyme like thiamine (B1) and lienamycin (Figure 1) as a natural product which shows potent antitumor activity [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Figure 1.

Thiazole containing natural molecules: (a). Vitamin thiamine (B1) and (b). Leinamycin.

Analog behavior of thiosemicarbazone in the fields of pharmacological and biological activities emphasizes to condense thiazole and thiosemicarbazide compounds in order to get its derivatives that contain –C=N–N–C=S- and also its transition metal complexes support to employ in a diverse applications such as antimicrobial, antitumour,anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-degenerative and anti-HIV agents etc [10, 11, 12, 13].

Binding of small organic compounds with DNA alters the structure and function of the genetic material. Amongst a plethora of such binders like thiazole and thiosemicarbazone derivatives have exhibited their affinity towards DNA via. different modes of bindings or cleavage, uphold them as a promising antineoplastic agent and also stabilize topoII-DNA complex in the cell that leads to apoptosis. Electrophilic (C5) and nucleophilic substitution (C2) on thiazole ring along with nucleophile system in thiosemicarbazone and its ancillary moieties contribute to their broad spectrum of biological activities [14, 15, 16, 17]. Further, the coordinating with the metal ions such as iron, cobalt, nickel, copper and zinc often results to enhance biological activities of the precursor ligands through modifying lipophilicity and the mechanism of their action within the cell [18,19]. The metal complexes are mainly being considered due to their wide applications in the field of electrochemical, catalysis, biochemical and pharmacological researches including low toxicity [20, 21, 22].

Indeed, carboxylic acid, NO2 and OH [23] groups in heterocyclic compounds release more free radicals in the medium that may cause to damage unhealthy cells along with healthy microbial cells. Hence, in the light of this propinquity research and continuation of our work on carbothioamide Schiff bases [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30], we are herein reporting the synthesis and characterization of [(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene]amino]thiourea and its bivalent Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes and investigated the DNA interactions, cleavage and bacterial inhibition efficiency in the absence of oxygen, hydroxyl and NO2 anicillary groups.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and instruments

All starting compounds were of analytical grade and double distilled water used throughout the experiments. The commercially purchased reagents, 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxy propane 99% (Aldrich), Ethanethioamide 99% (Spectrochem), thiosemicarbazide 99% (Aldrich)) and solvents were used without further purification unless otherwise noted. C, H, N and S (elemental analysis) were estimated on Thermo Scientific Flash 2000 Organic Elemental Analyzer, IISc, Bangalore. Melting points (LAB JUNCTION, LJ-935) were determined in evacuated capillaries. All the infrared spectra were recorded in the 4000-400cm−1 region (KBr disc) on a Nicolet protage 460 FT-IR spectrophotometer. 1H and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 at 400 and 100 MHz Bruker NMR spectrometer. Magnetic susceptibility of the complexes were carried at room temperature using magnetic susceptibility balance (Sherwood Scientific, Cambridge, England) and using CuSO4.5H2O as standard. Electronic spectra of the complexes were recorded on ELICO SL159 UV-Visible spectrophotometer in DMF solvent. EPR spectrum was recorded on various E-112 X-band spectrophotometer in DMSO solvent at liquid nitrogen temperature. DNA cleavage abilities of the compounds were studied using Gel Electrophoresis UVITEC, Cambridge, UK. All bacterial strains used were collected from Department of Biotechnology, MSRIT and Ramaiah Medical college, Bangalore. EtBr quenching studies were performed on F-2300 spectrofluorimeter (Hitachi, Japan) equipped with 1.0 cm quartz cell at 298k. The excitation and emission slit widths were kept at 5 nm and the excitation wavelengths 307nm (complex 2a), 305nm (complex 2b) and 304nm (complex 2c) and the emission wavelengths were at 595 nm, 604.5 nm and 623nm respectively. The excitation and emission wavelength for EB-DNA complex were fixed at 540 nm and 600 nm respectively.

2.2. Synthesis of the Schiff base and its complexes

The ligand was prepared using the following steps and schematic representation of the detailed path shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of compound 1(IT) and compound 2(ITHC). (i). HCl, Br2;(ii).Imidazolidinethione, ethanol; (iii). Thiosemicarbazide, EtOH, Reflux for 2 h.

2.2.1. Preparation of 2-bromomalonaldehyde

2-Bromomalonaldehyde, a starting material was synthesized by following a procedure described in the literature [31,32]. At below 35 °C, 0.15M bromine solution was added dropwise to the 1, 1, 3, 3-tetramethoxypropane (0.12M) in presence of conc HCl (4.3ml) and continuously stirred for another 30 min. A slurry compound obtained was cooled below 50 °C and separated by rotary evaporation, then washed thoroughly with cold dichloromethane and dried in a vacuum over anhydrous CaCl2. (Yield: 65%, MP: 148 °C).

2.2.2. Preparation of 2-Methylthiazole-5-carbaldehyde(MT) (1)

The equimolar mixture of bromomalonaldehyde and ethanethioamide in acetonitrile stirred vigorously for 1 h at room temperature and stirring continued for 2 h at 80 °C. Then, the solvent was removed under vacuum and to maintain the alkaline medium dil. NaOH was added. The dark yellow colour slurry formed was extracted in ethyl acetate and dried in vacuum desiccators over anhydrous CaCl2. Yield: 82%,1H-NMR (DMSO, 400MHz): δ 2.80 (s; 3H), δ 8.27 (s; 1H), δ 9.98 (s; 1H), 13C-NMR (DMSO, 100MHz): δ 20.17; δ139.46; δ151.44; δ174.83; δ182.03. IR (cm−1): 3431 (NH), 1596 (C=N), 1165 (C=S).

2.2.3. Preparation of the [(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene]amino]thiourea (MTHC) (2)

An ethanolic solution of 2-methyl-1,3-thiazole-5-carbaldehyde was added to 5% aqueous acetic acid solution of thiosemicarbazide. The resulting mixture was refluxed on water bath for 45–60 min. On cooling to room temperature, dark yellow compound formed was collected and washed with hot water for several times and dried in vacuum. Yield: 78%, MP: 228 °C, 1H-NMR (DMSO, 400MHz): δ 2.64 (s; 3H), δ 7.60(s; 1H), δ 7.90 (s; 1H), δ 8.21(s; 1H), δ 8.23 (s; 1H),δ 11.52 (s; 1H), 13C-NMR (DMSO, 100MHz): δ 19.25; δ134.13; δ135.37; δ144.92; δ167.75; δ177.69. IR (cm−1): 3331 (NH), 1534 (C=N), 1159 (C=S).

2.2.4. Preparation of the metal complexes

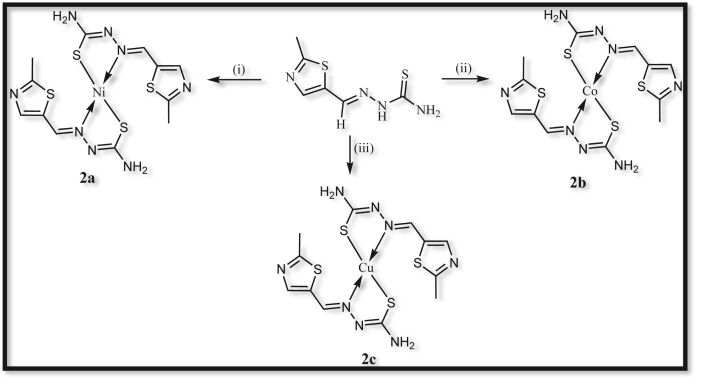

The following general procedure (Figure 3) was adopted for the synthesis of metal–MTHC complexes in 1:2 mol ratio. To an ethanolic MTHC ligand addes ethanolic solution of metal salt in a round bottom flask which was refluxed for about 2 h. The solid complex obtained was collected by filtration and washed with hot aqueous ethonal (2a: Yield: 76%, MP: 223 °C. 2b: Yield: 68%, MP: 222 °C. 2c: Yield: 65%, MP: 223 °C).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of metal complexes 2a, 2b, and 2c. (i). NiCl2.6H2O, EtOH, Reflux;(ii). CoCl2.6H2O, EtOH, Reflux;(iii). CuCl2.2H2O, EtOH, Reflux.

2.3. DNA interaction experiments

The DNA binding interaction of the synthesized compounds was investigated unsing absorption titrations and ethidium bromide displacement methods.

2.3.1. DNA interactions-electronic absorption spectroscopy

The DNA binding potency of newly synthesized ligand and its metal complexes with CT-DNA was investigated using ELICO SL150 electronic spectrometer. A stock solution of CT-DNA was prepared in 50mM Tris–HCl/50mM NaCl buffer solution (pH 7). The ratio of the absorbance at 260 nm and 280nm (A260/A280) gave 1.9 was evidence proteins free DNA. The DNA concentration was calculated by measuring the absorbance at 260nm taking its molar extinction coefficient (6600dm3mol−1cm−1). Absorption titrations were conducted for fixed concentration of the compounds and varying the DNA concentration (25–300 μL). A quantitative comparison and the intrinsic binding constant (Kb) was evaluated from the following Eq. (1) [33].

| (1) |

where εa, εb and εf correspond to apparent, bound and free metal complexes extinction coefficients respectively. A plot of [DNA]/(εa-εf)Vs [DNA] gave a slope of 1/(εb-εf) and a Y-intercept equal to 1/Kb(εb-εf), where Kb is the ratio of the slope to the Y-intercept.

2.3.2. Ethidium bromide displacement studies by Fluoresence Emission Spectroscopy

Ethidium bromide displacement studies by Fluorescence Emission Spectroscopy is an appropriate technique to compare the binding mode of the medicinal molecules with DNA. The width of the slit for emission and excitation was taken 5nm. All the other parameters of the fluorescencent spectrometer like response time (0.04s), excitation voltage (700V) and scan rate (1500 nm/min) was kept constant for each data set. A quartz cell of one centimeter diameter was used through out the experiment and background correction was done with an appropriate blank buffer solution. EtBr (EB) displacement experiments were carried out by adding metal complexes to the mixture of 10 μL of EB in Tris-HCl buffer solution (50μM, pH,7.2) and 24 μL of DNA solution. Fluorescence measurements were carried out at the exicitation wavelengths 307nm (complex 2a), 305nm (complex 2b) and 304nm (complex 2c) and the emission wavelengths were at 595 nm, 604.5 nm and 623nm respectively. In EB-DNA complex spectra excitation and emission wavelengths were fixed at 540 nm and 600 nm respectively.

2.4. DNA cleavage studies

Agarose gel electrophoresis was employed to evaluate the extent of pUC18 DNA cleavage activity of MTHC and its Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes in the presence and absence of an oxidizing agent, H2O2 at pH of 7.1. The experimental mixture (20 μL) contains 50mM of Tris-HCl (12–19 μL of pH 7.1), pUC18 DNA (1 μL of 200 μg/ml) and 5μL of 9.5mM of metal complex was further incubated at 37 °C for 60 min and then added 2 μL of 0.25% bromophenol blue +0.25% xylene cyanol +30% glycerol mixture. Thereafter it was loaded on 1% agarose gel containing 5μL ethidium bromide to carry out electrophoresis experiments in Tris-acetic acid-EDTA (TAE) buffer at 100V for 50 min. The cleavage ability of the compounds was examined using UV transilluminator by measuring the capacity of conversion from super coiled to open circular (OC) or nicked circular (NC) DNA form.

2.5. Antibacterial studies

By following Kirby-Bauer method [34], the bacterial inhibition potency of newly synthesized ligand and its metal complexes were probed over gram-positive (Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus subtilis) and gram-negative (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichiacoli) bacterial strains by comparing with ciprofloxacin taken as standard reference. The isolated strains were sub-cultured and incubated into 50 mL of nutrient broth at 37 °C for 18 h. In well diffusion method, 100 μL of this bacterial cultures were spread over nutrient agar and further 5mm size wells were developed to inject 9.5mM concentration of the compounds dissolved in DMSO. These bacterial strains on agar plate were brooded at 37 °C for 24 h to work out antibacterial experiments. By quantifying the zone inhibition around the wells in mm, the magnitude of anti bacterial activity of all the compounds was evaluated.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of the ligand and its metal complexes

The synthesized MTHC ligand and its Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes were air-stable, non-hygroscopic with sharp melting point. The less hydrophilic nature and high repulsion between the substituted groups reduce the aggregation of molecules which leads to the poor solubility of complexes in a polar solvents like water, methanol, and ethanol but readily soluble in aprotic solvents like DMF and DMSO etc. The analytical data of the ligand and its complexes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analytical data of ligands and metal complexes.

| Compounds | Color | Yield (%) | Melting Point (0C) | Elemental analysis Found (Cal)% |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | S | ||||

| MT (1) | Brown | 82 | 47.56 (47.23) | 4.51 (4.59) | 29.25 (29.02) | 25.35 (25.21) | |

| MTHC (2) | Dark yellow | 78 | 228 | 35.42 (35.98) | 3.83 (4.03) | 27.32 (27.98) | 32.59 (32.02) |

| [Ni(MTHC)2] (2a) | Gold | 76 | 223 | 31.81 (31.52) | 3.32 (3.09) | 24.9 (24.51) | 28.38 (28.05) |

| [Co(MTHC)2](2b) | Dark green | 68 | 222 | 31.89 (31.51) | 3.52 (3.08) | 24.32 (24.49) | 28.87 (28.03) |

| [Cu(MTHC)2](2c) | Dark yellow | 65 | 223 | 31.54 (31.19) | 2.90 (3.05) | 24.73 (24.25) | 27.80 (27.75) |

3.1.1. Infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectra of MTHC and its complexes were recorded in the region 4000-400 cm−1 using KBr disc. In the IR spectrum of MTHC (Figure 4) shows characteristic bands in 3269–3415 cm−1 regions are assigned to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrational modes of terminal –NH2 group and a band at 1171 cm−1 region is assigned to υ(C=S) stretching vibration.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectrum of Ligand, MTHC.

The vibrational bands between 1054-1087cm−1 and 703-1102cm−1 are revealed to aromatic C–S and aliphatic C–S stretching modes of the compounds. The anamolous shift of peak from 1596cm−1 region to a lower frequency (1494-1544cm−1) in the spectra of complexes suggests the involvement of azomethine (>C=N) nitrogen in chelation. In addition, an appearance of the additional band in the region 481-491cm−1 related to υ(M-N) signifies the complexation formed through metal and sulfur atom. The IR data of the compounds are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

FT-IR spectral data (cm−1) of ligands and metal complexes.

| Compound | ν(CH) | ν(NH) | ν(C=N) | ν(C–N) +ν(N–N) | C=S | ν(C–S) | ν(M-N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2970w | 3431m | 1596s | 1102m | 1165s | 1102 m | - |

| 2 | 2989w | 3331w | 1534s | 1092m | 1159s | 1092 m | - |

| 2a | 2943w | 3432m | 1494s | 1020m | - | 705w | 486 |

| 2b | 2971w | 3430w | 1544s | 1102w | - | 703w | 491 |

| 2c | 2969w | 3431w | 1544m | 1103m | - | 706w | 481 |

3.1.2. NMR analysis

1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of ligands, 2-Methylthiazole-5-carbaldehyde(MT) (1) and [(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene] amino]thiourea (MTHC) (2) were recorded in DMSO-d6 (400MHz) (Figure 5). The peak obtained at δ9.98 ppm in 1H and δ182.03 ppm in 13C-NMR confirms formation of the carbonyl moiety in compound 1. Absence of these peaks and the presence of a new peak at δ11.52 ppm corresponds to –NH proton (NH group next to C=S) that evidences the formation of thiosemicarbazone ligand. In 1H-NMR, the disappearance of peak at δ4.00 ppm discloses that the ligand is in amide state, even in polar solvent and is also confirmed from 13C-NMR Peak at around δ177.69 ppm.

Figure 5.

(a) 1H-NMR and (b) 13C-NMR spectrum of MT (1) and MTHC(2).

3.1.3. Electronic absorption spectra and magnetic studies of complexes

The electronic spectra of the metal complexes were recorded in DMF solvent in the spectral range 200–1100nm. In electronic spectra of the metal complexes, a peak observed between 32222-33783cm−1 is due to π→π∗ transition of the aromatic ring. The second band appeared around 22222-23041cm−1 is attributed due to azomethine group of the ligand to metal charge transfer bands. From the electronic spectrum of complex 2a, the observed peak at 16474cm−1 is assigned to 1A1g→1B1g and 1A1g→1A2g bands which suggest the square planar geometry of the Ni(II) complex [35]. The magnetic moment for the square planar Ni(II) complex is expected as diamagnetic or small paramagnetic in nature. But an abnormal magnetic moment (1.2BM) for the complex 2a may be due to spin orbit coupling and negligible metal-metal interactions which leads to anti ferromagnetism [36]. In complex 2b, the d-d transition band obtained at 14614cm−1 may be due to the square planar geometrical structure around the cobalt(II) metal ion. This can be evidenced from its magnetic moment value 3.01BM but the square planar complexes of Co(II) are having low spin magnetic values in the range of 2.2–2.9 [37]. Similarly complex 2c, exhibits a broad single d-d band appeared at 13157cm−1 which implies the three allowed spin transitions, 2B1g→2A1g(ν1), 2B1→2B2g(ν2) and 2B1←2Eg, probably due to square planar geometry around the copper(II) ion. The magnetic moment value of the complex (1.66BM) also coincides with the expected magnetic moment value for the square planar Cu(II) complexes (1.7BM) [38]. The UV-Visible spectra of complexes are shown in Figure 6 and data are given in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Electronic spectra of metal complexes, 2a, 2b and 2c.

Table 3.

Electronic spectral and magnetic moment data of metal complexes.

| Complex | π→π∗ (cm−1) | LMCT–transition (cm−1) | d→d transition (cm−1) | Magnetic Moment (BM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 33222 | 22371 | 16474 | 1.20 |

| 2b | 33222 | 22222 | 14614 | 3.01 |

| 2c | 33783 | 23041 | 13157 | 1.66 |

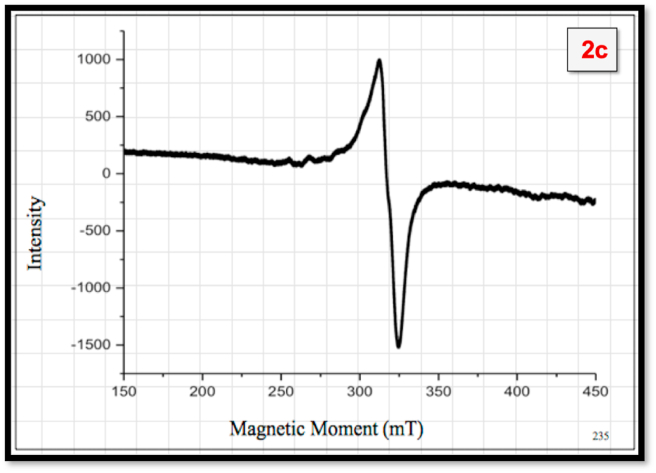

3.1.4. Electron spin resonance spectroscopy

The ESR spectrum of copper complex 2c was recorded in DMSO solvent at liquid nitrogen temperature (LNT). In ESR spectrum (Figure 7), the absence of half field signal at 1600T confirms the presence of ms = ±2 transitions and absence of Cu–Cu metal interaction. The ESR data of the complex (Table 4) corroborates axially symmetric g-tensor parameters with g|| >g⊥>2.0023 which refers to an unpaired electron present in dx2-y2 ground state and is a characteristic of square-planar geometry or square base pyramidal or octahedral geometry with D4h symmetry [39,40]. The g|| (greater than 2.3) suggests the bonding between metal (Cu2+) and ligand (MTHC) possess ionic character [41, 42, 43, 44]. The calculated gav value (gav=(g||+2g⊥)/3) lying in the range of 2.12–2.16 suggests the square planar structure of copper complex [45].

Figure 7.

ESR spectrum of 2c for X-band in liquid nitrogen temperature (LNT) in DMSO.

Table 4.

ESR spectral assignments for the Cu(II) complex.

| Complex | g// | g | gav | G | A//(10−4) | A (10−4) | Aavg (10−4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2c | 2.3323 | 2.0825 | 2.165 | 4.10 | 88.18 | 125.30 | 0.00377 |

| K// | K | K | α2 | β2 | γ2 | F | |

| 0.8928 | 0.4401 | 0.4424 | 0.6133 | 1.2996 | 0.3158 | 264 |

According to Hathaway, G factor decides the presence and absence of interaction between copper centers. The calculated G factor of the present complex greater than 4 implies an absence of interaction between the copper centers [46, 47, 48, 49]. The ESR parameters g‖, g⊥, A‖ and A⊥ of the complex and the energies of d-d transitions are used to evaluate the orbital reduction parameters (K‖, K⊥) [50]. Hathaway has pointed out that, for the pure σ–bonding, K‖ ≈K ≈ 0.77, for in-plane π-bonding, K⊥<K‖ and for out-of-plane π-bonding, K⊥>K‖. The orbital reduction parameters (K⊥<K‖) observed (Table 4) are assigned in plane π-bonding. The reduction of P value related to free ion (0.036 cm−1) may be attributed to the strong covalent bond between Cu(II) ion and MTHC synthesized ligand according to Giordan and Bereman who suggests the identification of bonding groups from the values of dipolar term P [35]. The molecular-orbital coefficients, α2 (a measure of the covalency of in-plane σ-bonding between the 3d orbital and the ligand orbitals) and β2 (the covalent in-plane π -bonding) are calculated by employing the following Eqs. (2) and (3) [51].

| (2) |

| (3) |

where λ = -828 cm−1 for the free copper ion and E is the electronic transition energy.

The empirical factor (f = g‖/A‖ cm) indexes of distortion from an idealized geometry. The value of ‘f’ factor for the compound 2c is 264 which signifies large distortion of the planar structure due to rigidity of bidentate thiosemcarbazone derivative [52].

3.2. DNA binding studies

3.2.1. Electronic absorption spectroscopy

The investigation of the interactions between synthesized complexes (2a, 2b and 2c) with CT-DNA by electronic absorption spectroscopy has paramount importance in understanding the binding mechanism. An intense band observed around 237–350 nm (Figure 8) is attributed to π→π∗ intra-ligand transition. Under the identical experimental conditions on addition of CT-DNA to the complexes exhibit a negligible red shift (1–2nm) along with hypochromism. The magnitude of hypochromism and red shift determines the binding strength and intrinsic binding constant Kb for complexes with CT-DNA. Therefore, by considering the obtained results, hypochromism with a red shift evidences an intercalation binding mode established between the π∗ orbital of the ligand and π orbital of base pairs in DNA results in reduction of π–π∗ transition energy [48,49]. On the other hand, the coupling π orbital with partially filled electrons, thus decreases the transition probabilities, which leads to hypochromism and further results in the red shift. The extent of the hypochromism along with or without small red shift commonly reflects the intercalative binding strength [53,54]. The substituent like chloride, methoxy etc neucleophilic or electrophilic nature of the functional group slightly modifies dipole of the ligand which may in turn changes dipole-dipole interactions in the binding sites resulting in the increasing binding capacity of a ligand with DNA strands. However, the skeleton of ligand plays a vital role in binding interactions than the substituents.

Figure 8.

Electronic absorption spectra of metal complexes 2a, 2b and 2c in the absence and presence of increasing amounts of CT-DNA. Arrow shows the change in the absorbance with increase the DNA concentration. Inset: plot of [DNA]/(εA-εF) Vs [DNA].

The slope and y-intercept of [DNA]/(εa−εf) versus [DNA] graph (Figure 8, inset) has been used to computate binding constant for the metal complexes. From Table 5, the DNA binding constansts are in the order of 106 M−1 which is evidence for equal to the classical intercalators [55].

Table 5.

Electronic absorption data upon addition of CT-DNA to the complexes.

| Complex | λmax (nm) |

Δλ (nm) | %H | Kb (M−1) | R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | Bound | |||||

| 2a | 318 | 320 | 2 | 41.58 | 2.713 × 106 | 0.999 |

| 2b | 310 | 311 | 1 | 10.39 | 5.529 × 106 | 0.999 |

| 2c | 321 | 323 | 2 | 17.83 | 2.950 × 106 | 0.999 |

3.2.2. EB-displacement studies by Fluoresence Emission Spectroscopy

Fluorescence emission spectral studies were carried out to ascertain the interaction of metal complexes with DNA while displacing EB from EB-DNA complex. EB establishes intercalative binding with DNA, thus, increases fluorescence intensities in the formation of EB-DNA complex. A decrease or increase in fluorescence intensity (Figure 9(i)) has been observed in fluorescence EB displacement experiments conducted in Tris-HCl buffer solution while enhancing the metal complexes concentration. Tris- HCl buffer solution (pH,7.2) is used in these experiments since EB is non-emissive because of quenching of free EB by the solvent molecules [56]. The Stern –Volmer quenching constant Ksv value was computed using the classical Stern-Volmer Eq. (4)

| (4) |

where F0 and F are fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of quencher, respectively; ksv is a linear Stern-Volmer quenching constant; [Q] is the concentration of quencher and is the average fluorescence life time of the bimolecule [10−8 s] in absence of the quencher [57].

Figure 9.

(i) Fluorescence titration of CT-DNA and EB (intercalator) with complexes 2a, 2b and 2c (ii) Stern-Volmer plot for fluorescence quenching of metal complexes by EB in absence and presence of CT-DNA and Plot of log (Fo- F)/F as a function of log [Q] (iii) Plot of F0/F as function of [Q].

Quenching rate constant Kq which suggests static and dyamic quenching of compounds with EB-DNA complex. Kq is calculated from the below equation derived from Eq. (5)

| (5) |

The Stern-Volmer plots, i.e F0/F vs [Q] shown in Figure 9(iii) and slope of linear graph is equal to Ksv. The larger values of the quenching rate constant Kq, implies that the quenching is due to the formation of a complex between metal complexes and DNA, i.e static quenching. The number of binding stoichiometry (n) has been determined from Eq. (6) [57]:

| (6) |

The slope of log (F0–F)/F vs log [Q ] plot (Figure 9(ii)) gives the binding stoichiometry (n) which is equal to 1.007 for 2a, 1.43 for 2b and 1.22 for 2c (Table 6).

Table 6.

Fluorimetric spectral data with addition of CT-DNA to complexes 2a, 2b and 2c.

| Complex | Stern-Volmer Quenching constant x104 (M−1) Ksv | Quenching rate constant Kq x1012 (M−1s−1) | Number of binding site (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 1.891 | 1.891 | 1.007 |

| 2b | 3.361 | 3.361 | 1.43 |

| 2c | 8.067 | 8.067 | 1.22 |

Based on the fluorescence and absorption studies data, it is observed the metal complexes are interacting with DNA through intercalative mode.

3.3. DNA cleavage studies

Gel electrophoresis is a well advanced technique to find sequences of RNA and DNA of the living organisms which helps to curtail the growth of the diseased microbes with a suitable drug, including death of the infected (cancer or tumor) cells by inhibiting topoisomerase II (to avoid replication of damaged DNA) in the human body. It functions on the basis of DNA migration under the presence of an electric field employed. For comparative studies, the cleavage of DNA strands (agarose gel electrophoresis) by ligand and its complexes were investigated with and without the addition of H2O2 (Figure 10). The prepared ligand and its metal complexes (except complex 2c) are unable to exert appreciable cleavage efficiency under physiological experimental conditions. This may be due to non-protonation of metal complexes which leads to non formation of ROS to do cleavage of pUC18 DNA and may be due to the concentration of solvent DMSO, O2· OH. radical scavenger [58]. However, on complexation with Cu2+ ions, the activity has been enhanced moderately due to its affinity towards DNA strands [59, 60, 61, 62].

Figure 10.

Gel electrophoresis diagram: Lane 1: DNA control; lane 2: DNA + H2O2; lane 3: compound 2 + DNA; lane 4: compound 2 + DNA + H2O2; lane 5: compound 2a + DNA; lane 6: compound 2a + DNA + H2O2; lane 7: compound 2b + DNA; lane 8: compound 2b + DNA + H2O2; lane 9: compound 2c + DNA; lane 10: compound 2c + DNA + H2O2.

3.4. Antibacterial studies

Microorganisms in biosphere play a vital role to maintain an environmental equilibrium. Among those, disease–causing microorganisms are vulnerable to human health that must be deprived or controlled using habitual anti-microbial agents.

In-vitro studies of newly synthesized ligand which is a basic core of many antimicrobial drugs and its bactericidal function in presence of metal through coordination(well diffusion method) were performed against Ciprofloxacin, a reference, with gram-positive strains Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus subtilis and same as with gram-negative strains Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, shown in Figure 11 and those results are incorporated into Table 7.

Figure 11.

Anti-bacterial activity of metal complexes 2a, 2b and 2c on Bacillus subtilis, S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa and E. coli bacterial strains and Ciprofloxacin as standard drug.

Table 7.

Antibacterial activities of the compounds (20 μg/mL).

| Compound | Bacterial Strain Zone of Inhibition (in mm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | S. epidermidis | P. aeruginosa | E. coli | |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 2a | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2b | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 2c | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

Overtone's and Chelation theory converses on dipole moment of the metal complex which is a measure of metal ion polarity by partial sharing of positive charge and over lapping Pi/d electrons of ligand in presence of the solvent. It is used to get lipophilicity which plays a significant role in regulating antimicrobial activity. From the antibacterial screening data, it is observed that metal complexes have not shown better inhibiting activity than the ligands [63,64].

Overall, comparison of bacterial inhibition growth by all the metal complexes is not satisfactory against the tested organisms, shown in Figure 12. The underlying causes of this ironical result are Physio-chemical properties of the complexes like coordination of metal-ligand (mono nuclear, neutral complex), charge distribution (dipole moment of a molecule), ancillary methyl group at the position 2 of thiazole which causes for the weaken the activy of thiazole compound and partition coefficient of the metal complexes between the solvent and bacterial membrane. Liophilicity (log P) saturation by the metal complexes are not attained because of absence of lipophilic groups like benzene, flavonoids in thiazole as well as the presence of electron rich N and S in the ligand reduces non polar nature in metal ion that leads to poor interactions with the bacterial membrane, hence, exerts moderate antibacterial activity. The high strength of the bond between metal and ligand provides a less number of metal ions to diffuse by passive transport through the cell membrane or interact with the receptor of bacterial membrane. Hence, metal complexes show less anti-bacterial efficacy than the ligand [46,47,65,66]. Similar observations have been noticed in previous studies with different substituents such as cyclic amine group, p-tolyl,ethoxy carbonyl and electron withdrawing groups like NO2 respectively [17] and/or substituents on thiosemicabazone moiety [67,68] and even in the absence of hydrogen bond acceptor and hydrophobic portions which also exhibits moderate inhibitory activity [14,17].

Figure 12.

Column 3-D cylindrical chart of the anti-bacterial activity of Ligand and its Ni(II), Co(II) and Cu(II) complexes.

4. Conclusion

Newly synthesized [(E)-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methylidene]amino]thiourea and its Ni(II), Co(II) and Cu(II) complexes were prepared and investigated their anti-bacterial, DNA-binding and DNA cleavage studies. The in-vitro antibacterial activity results indicates moderate inhibitory activity of the metal complexes. It may be due to high electron density in ligand which supports to get a strong bond between metal ion and ligand and also absence of methoxy, chloride etc substituent functional groups and also absence of hydrophobic groups cause to get low liophilicity nature by metal complexes that results in less interaction with the bacterial memebrane. The DNA binding interactions of the complexes by absorption and fluorescence studies shows complexes are interacted through intercalation mode with DNA. It is observed that except copper(II) complex, ligand and its Ni(II) and Co(II) complexes shows no significant DNA cleavage activity both in presence and absence of hydrogen peroxide due to aprotonation nature of the metal complexes.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Basappa C Yallur: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

P. Murali Krishna: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Malthi Challa: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Kandikere Ramaiah Prabhu, Department of Organic Chemistry, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, for kind technical support.

Contributor Information

Basappa C. Yallur, Email: yallurbc@msrit.edu.

P. Murali Krishna, Email: muralikp@msrit.edu.

References

- 1.SiddiquiN, ArshadM F., Ahsan W., AlamM S. Thiazoles: a valuable insight into the recent advances and biological activities. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Drug Res. 2009;1(3):136–143. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matjaž B., Perdih Andrej, Renko Miha, Anderluh G., Dušan T., Tom S. Structure-Based discovery of substituted 4,5′-bithiazoles as novel DNA gyrase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55(14):6413–6426. doi: 10.1021/jm300395d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hara M., Asano K., Kawamoto I., Takiguch T., Katsumata S., Takahashi K.I., Nakano H., Leinamycin A new antitumor antibiotic from Streptomyces: producing organism, fermentation and isolation. J. Antibiot. 1989;42(12):333–335. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara M., Saitoh Y., Nakano H. DNA strand scission by the novel antitumor antibiotic leinamycin. Biochemist. 1990;29:5676–5681. doi: 10.1021/bi00476a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asia A., Hara M., Kakita S., KandaY, Yoshida M., Saito H., Saitoh Y. Thiol-mediated DNA alkylation by the novel antitumor antibiotic leinamycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118(28):6802–6803. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitra K., Kim W., Daniels J.S., Gates K.S. Oxidative DNA cleavage by the antitumor antibiotic leinamycin and simple 1,2-Dithiolan-3-one 1-oxides: evidence for thiol-dependent conversion of molecular oxygen to DNA-cleaving oxygen radicals mediated by polysulfides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119(48):11691–11692. [Google Scholar]

- 7.BreydoL ZangH., Mitra K., Gates K.S. Thiol-independent DNA alkylation by leinamycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123(9):2060–2061. doi: 10.1021/ja003309r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gates K.S. Mechanisms of DNA damage by leinamycin. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13(10):953–959. doi: 10.1021/tx000089m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayana B., Vijaya Raj K.K., Ashalatha B.V., Suchetha N.K., Sarojini B.K. Synthesis of some new 5-(2-substituted-1, 3-thiazol-5-yl)-2-hydroxy benzamides and their 2-alkoxy derivatives as possible antifungal agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2004;39(10):867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar Shalin, Durga Nath D., Saxena P.N. Applications of metal complexes of Schiff base. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2009;68(3):181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahid H.C., Adrea S., Supuran C.T. Zinc complexes of benzothiazole-derived Schiff bases with antibacterial activity. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2003;18(3):259–263. doi: 10.1080/1475636031000071817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faizul A., Satendra S., Sukhbir L.K., Prakash O. Synthesis of Schiff bases of naphtha [1,2-d]thiazol-2-amine and metal complexes of 2-(2′-hydroxy)benzylideneaminonaphtho -thiazole as potential antimicrobial agents. J. Zhejiang Univ. - Sci. B. 2007;8(6):446–452. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reji T.F., Devi S.K.C., Thomas K.K., Sreejalekshmi K.G., Manju S.L., Barathan A., Rajasekharan K.N. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of thiazole analogs of the anticancer marine alkaloid dendrodoine. Indian J. Chem. 2008;47B(7):1145–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stella C., Barbara P., Daniela C., Domenico S., Elisa G., Girolamo C., Patrizia D. Thiazoles: their benzofused systems, and thiazolidinone derivatives: versatile and promising tools to combat antibiotic resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63(15):7923–7956. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stella C., Petri G.L., Barbara P., Daniela C., Funel N., Bergonzini C., Mantini G., Dekker H., Geerke D., Peters G.J., Cirrincione G., Giovannetti E., Patrizia D. Imidazo[2,1-b] [1,3,4]thiadiazoles with antiproliferative activity against primary and gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;189(1):112088. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stella C., Daniela C., Barbara P., Camilla P., ElisaG GirolamoC., Patrizia D. Therapeutic strategies to counteract antibiotic resistance in MRSA biofilm-associated infections. ChemMedChem. 2021;61:65–80. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stella C., Giovanna L.P., Barbara P., Btissame E.H., Daniela C., Vincenzo A., Ugo P., Alessandro P., NiccolaF, Godefridus J.P., Girolamo C., Elisa G. Patrizia D, 3-(6-phenylimidazo [2,1-b][1,3,4]thiadiazol-2-yl)-1H-indole derivatives as new anticancer agents in the treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Molecules. 2020;25(2):329–345. doi: 10.3390/molecules25020329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh Nanda K., Anju S., Sodhi A., Priya R. In vitro and in vivo antitumour studies of a new thiosemicarbazide derivative and its complexes with 3d-metal ions. Transition Met. Chem. 2000;25:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrew J.H., Hannah K., Abedawn I.K., Abdolrasoul H.E., Roger D.W., Colin J.S., Tom B., Keith R.F. DNA sequence recognition by an imidazole-containing isopropyl-substituted thiazole polyamide (thiazotropsin B) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3469–3474. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra A.P., RajendraK J. Microwave synthesis, spectroscopic, thermal and biological significance of some transition metal complexes containing heterocyclic ligands. J. Chem. Pharmaceut. Res. 2010;2(6):51–61. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinusha H.M., Shiva Prasad K., Chandan S., Muneera B. Imino-4-Methoxyphenol thiazole derived Schiff base ligands: synthesis, spectral characterization and antimicrobial activity. Chem. Sci. J. 2015;6(3):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venugopal N., Krishnamurthy G., Bhojyanaik H.S., Murali Krishna P., Synthesis Spectral characterization and biological studies of Cu (II), Co (II) and Ni (II) complexes of azo dye ligand containing 4‒amino antipyrine moiety. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1183:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cansu A., Ö Burcu, Hayriye G.B., Mustafa Z., Nazan D.Y. Developmental toxicity of (4S)-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid in zebrafish (daniorerio) Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2017;60:1–10. e17160547. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murali Krishna P., Gopal Reddy N.B., Harish B.G., Yogesh P., Munirathnam N. Synthesis, structural studies, molecular docking and DNA binding studies of 4N-substituted hydrazinecarbothioamides. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1175:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umesha K., Yallur B.C., Manjunatha D.H., Murali Krishna P. BSA interaction and DNA cleavage studies of newly synthesized anti-bacterial Benzothiazol-2-yl-malonaldehyde. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1196:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yallur B.C., Umesha K., Murali Krishna P., Manjunatha D.H. BSA binding and antibaterial studies of newly synthesized 5,6-Dihydroimidazo[2,1-b]thiazole-2-carbaldehyde. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;222:117–192. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sennappan M., Murali Krishna P., Amar A.H., Hari Krishna R. Synthesis, characterization, nucleic acid interactions and photoluminescent properties of methaniminium hydrazone Schiff base and its Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1164:271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gopal Reddy N.B., Murali Krishna P., Shantha Kumar S.S., Yogesh P., Munirathinam N. Structure and spectroscopic investigations of a bi-dentate N'-[(4-ethylphenyl) methylidene]-4-hydroxybenzohydrazide and its Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Cd(II) complexes: insights relevant to biological properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1137:543–552. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yallur B.C., Murali Krishna P., Amar A.H. Benzo[4,5]imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole-2-carbaldehyde. IUCrData. 2016;1:x160778. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murali Krishna P., Hussain Reddy K. Synthesis, structural characterization and DNA studies of trivalent cobalt complexes of (2E)-4N-substituted-2- [4-(propan-2-yl)benzylidene]hydrazine- carbothioamide. Mediterranean J. Chem. 2017;6(3):88–98. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trofimenko S. Dihalomalonaldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 1963;28(11):3243–3245. doi: 10.1021/jo01046a526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.John W.T., John McGuire J., James K.C. Synthesis of (6R)- and (6S)-5,10-dideazatetrahydrofolate oligo-γ-glutamates: kinetics of multiple glutamate ligations catalyzed by folylpoly-γ-glutamate synthetase. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3(18):3388–3398. doi: 10.1039/b505907k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfe A., Shimer G.H., Meechan T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons physically intercalate into duplex regions of denatured DNA. Biochemist. 1987;26(20):6392–6396. doi: 10.1021/bi00394a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veronica M.E., Ascp M.T.B.S., Don E.E., Ascp M. Experiences with the kirby-bauer method of antibiotic susceptibility testing. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1970;54(2):193–198. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/54.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raman N. Antifungal active tetraaza macrocyclic transition metal complexes: designing, template synthesis, and spectral characterization. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2009;35:234–238. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assefa W., Raju V.J.T., Chebude Y., Retta N. DinuclearMetal complexesderived from a bis-chelating heterocyclic ligand. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2009;23(2):187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aderoju A.O., Balogun S. Spectral, magnetic, thermal and antibacterial properties of some metal (II) complexes of aminoindanyl Schiff base. Eur. J. Appl. Sci. 2012;4(1):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lever A.B.P. Elsevier; 1968. Inorganic Electronic Spectroscopy; p. 320. 318. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salah B., Radha M., HoumamB, TouhamiL, DjemouiB Electronic structure and physico-chemical property relationship for thiazole derivatives. Asian J. Chem. 2013;25(16):9241–9245. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boas J.F., Dunhill R.H., Pilbrow J.R., Srivastava R.C., Smith T.D. Electron spin resonance studies of copper(II) hydroxy-carboxylic acid chelates in aqueous and non-aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Soc. 1969:94–108. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kivelson D., Neiman R. ESR studies on the bonding in copper complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 1961;35:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao Sanjayi, Reddy Hussian. Synthesis and spectral studies of copper(II) and nickel(II) complexes of isomeric and heterocyclic benzoylhydrazones. Indian J. Chem. 1996;35A:681–686. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adel E., Badar E.S., Ahmed A.E., Synthesis Spectroscopic characterization and thermal behavior on novel binuclear Transition metal complexes of hydrazones derived from 4,6-diacetylresorcinol and xalyldihydrazine. Spectrochim. Acta A. 2008;69:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hathaway B.J. A new look at the stereochemistry and electronic properties of complexes of the copper(II) ion. In: Struct J., Bond, editors. Vol. 57. 1984. pp. 55–118. (Complex Chemistry). (Berlin) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abeda Jamadar. University of York; Helistong, England: 2012. Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes of Aroylhydrazones as Potential Antitubercular Agents. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanja P.K., Cvetković D.D., Barna D.J. The effect of lipophilicity on the antibacterial activity of some 1-benzylbenzimidazole derivatives. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2008;73(10):967–978. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svetlana V.B., Angelica V.S., Marina V.O., Тatyana V.V., German L.P. Solubility, lipophilicity and membrane permeability of some fluoroquinolone antimicrobials. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2016;93:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pratviel G., Bernadou J., Meunier B. DNA and RNA cleavage by metal complexes. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 1998;45:251–312. [Google Scholar]

- 49.You-Shan Li, Ma Bin Peng Li, Cao Sheng-Li, Bai Lu-Lu, Yang Chao-Rui, Wan Chong-Qing, Hao-JieYan, Ding Pan-Pan, Li Zhong-Feng, Ying-Ying Meng Ji Liao, Wang Hai-Long, Jing Li, Xu Xingzhi. Synthesis, crystal structures and antitumor activity of two platinum(II) complexes with methyl hydrazinecarbodithioate derivatives of indolin-2-one. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;127:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maki A.H., Megarvery B.R. Electron spin resonance in transition metal chelates. I. Copper (II) bis-acetylacetonate. J. Chem. Phys. 1958;29(1):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeyasubramanian K., Samath S.A., Thambidurai S., Murugesan R., Ramalingam S.K. Cyclicvoltammetric and ESR studies of a tetraaza 14-membered macrocyclic copper(II) complex derivedfrom 3-salicylideneacetylacetone and o-phenylenediamine: stabilization and activation ofunusual oxidation states. Transition Met. Chem. 1996;20:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajeev Chikate C., AvadhootR B., Subhash B.P., Doulas X.W. Transition metal quinone–thiosemicarbazone complexes 1: evaluation of EPR covalency parameters and redox properties of pseudo-square-planar copper(II)–naphthoquinone thiosemicarbazones. Polyhedron. 2005;24(8):889–899. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakthikumar K., Raja J.D., Sankarganesh M., Rajesh J., Antimicrobial Antioxidant and DNA inInteraction of water-soluble complexes of Schiff base of MorpholineMoiety. Indian J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2018;80(4):727–738. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nahid S., Somaye M., Robabeh A. DNA interaction studies of a new platinum (II) complex containing different aromatic dinitrogen ligands. Bioinorgan. Chem. Appl. 2011:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2011/429241. Article ID 429241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Almeida S., Lafayette E., da Silva L., Amorim C., de Oliveira T., Ruiz A., Júnior L., Synthesis DNA binding, and antiproliferative activity of novel acridine-thiosemicarbazone derivatives. Intl. J. Molecular Sci. 2015;16(6):13023–13042. doi: 10.3390/ijms160613023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shivakumara N., Murali Krishna P., Synthesis Spectral characterization, evaluation of their DNA interaction of 5-substituted-2-thiadiazole-amine. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1199:126999. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun Y., Ji F., Liu R., Lin J.Xu Q., Gao C. Interaction mechanism of 2-aminobenzothiazole with herring sperm DNA. J. Lumin. 2012;132(2):507–512. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kevin D.F.C., Robert L.H., Ted W.J. Lipophilic efficiency: the most important efficiency metric in medicinal chemistry. Future Med. Chem. 2013;5(2):113–115. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rabindra Reddy P., Raju N., Raghavaiah P., Hussain S. Picolinic acid based Cu(II) complexes with heterocyclic bases – crystal structure, DNA binding and cleavage studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;79:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perin N., Nhili R., Cindrić M., Bertoša B., Vušak D., Martin-Kleiner I., Laine W., Karminski-Zamola G., Kralj M., David-Cordonnier M.H., Hranjec M. Amino substituted benzimidazo[1,2-a]quinolines: antiproliferative potency, 3D QSAR study and DNA binding properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;122:530–545. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Küng A., Pieper T., Wissiack R., Rosenberg E., Keppler B.K. Hydrolysis of the tumor-inhibiting ruthenium(III) complexes HIm trans-[RuCl4(im)2] and HInd trans-[RuCl4(ind)2] investigated by means of HPCE and HPLC-MS. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2001;6(3):292–299. doi: 10.1007/s007750000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thota S., Vallala S., Yerra R., Rodrigues D.A., Raghavendra N.M., Barreiro E.J. Synthesis, characterization, DNA binding, DNA cleavage, protein binding and cytotoxic activities of Ru(II) complexes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;82:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manimaran A., Jayabalakrishnan C. DNA-binding, catalytic oxidation, CC coupling reactions and antibacterial activities of binuclear Ru (II) thiosemicarbazone complexes: synthesis and spectral characterization. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2012;3:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prabhakaran R., Anantharaman S., Thilagavathi M., Kaveri M.V., Kalaivani P., Karvembu R., Dharmaraj N. Preparation, spectroscopy, EXAFS, electrochemistry and pharmacology of new ruthenium(II) carbonyl complexes containing ferrocenylthiosemicarbazone and triphenylphosphine/arsine. Spectrochim. Acta. 2011;78(2):844–853. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Constantinescu T., Lungu C.N., Lung I. Lipophilicity as a central component of drug-like properties of chalchones and flavonoid derivatives. Molecules. 2019;24(8):1505. doi: 10.3390/molecules24081505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Echeverría J., Opazo J., Mendoza L., UrzúaA, Wilkens M. Structure-activity and lipophilicity relationships of selected antibacterial natural flavones and flavanones of Chilean flora. Molecules. 2017;22:608. doi: 10.3390/molecules22040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dilovic Ivica, MitraRubcic VisnjaVrdoljak, Kraljevic Sandra, MarijetaKralj Ivo Piantanida, Cindric Marina. Novel thiosemicarbazone derivatives as potential antitumor agents: synthesis, physicochemical and structural properties, DNA interactions and antiproliferative activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16(9):5189–5198. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vijesh A.M., Isloor Arun M., Shetty Prashanth, Sundershan S., Kun Fune Hoong. New pyrazole derivatives containing 1, 2, 4-triazoles and benzoxazoles as potent antimicrobial and analgesic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;62:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.