Abstract

Purpose

To assess the efficacy and safety of topical application of clotrimazole versus others in the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC).

Method

Four electronic databases, registries of ongoing trials, and manual search were used to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy of clotrimazole to other antifungal agents in patients who were clinically diagnosed with oral candidiasis up to November 1st, 2019. Primary outcomes were clinical response and mycological cure rates. Secondary outcomes include relapse rate, incidence of systemic infections, and compliance. Adverse effects were also evaluated.

Results

Sixteen RCTs with a total of 1685 patients were included. Half of the eligible studies were considered at high risk of performance bias and more than a third, at high risk of reporting bias. Our analysis showed no significant difference in clinical response between clotrimazole and all other antifungal agents. However, clotrimazole was less effective in terms of mycologic cure and relapse rate. Sensitivity analysis comparing clotrimazole to other topical antifungal agents only showed no differences in clinical response, microbiologic cure or relapse. Further sensitivity analysis showed significant efficacy of fluconazole over clotrimazole.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis indicated that clotrimazole is less effective than fluconazole but as effective as other topical therapies in treating OPC. Well-designed high-quality RCT is needed to validate these findings.

Keywords: Clotrimazole, Oral candidiasis, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OPC, oropharyngeal candidiasis; OR, odds ratio

1. Introduction

Candida is a part of normal flora residing on the skin, in gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts. About 45% of healthy individuals carry candida in their oral cavities (Shin et al., 2003). In certain conditions when host immune defense is compromised, candida can multiply in the superficial epithelium of the oral mucosa and become pathogenic causing oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), a common fungal infection (Farah et al., 2010, Millsop and Fazel, 2016, Naglik et al., 2003). Candida albicans is the most etiologic species of OPC; however, C. glabrata, C. dubliniensis, and C. krusei, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis have also been described (Patel et al., 2012, Sangeorzan et al., 1994). Multiple predisposing factors are associated with OPC including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, solid organ or hematologic malignancies, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, diabetes mellitus, hyposalivation, denture use, as well as exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, immunomodulators, and xerostomic agents (Belazi et al., 2005, Compagnoni et al., 2007, Farah et al., 2010, Figueiral et al., 2007, Palmer et al., 1996, Scully, 2003, Soysa et al., 2008, Worthington et al., 2002). Diagnosis is generally made by physical examination and medical history review and confirmed by microscopic examination with a potassium hydroxide preparation that reveals pseudohyphae or budding yeast from swaps or scrapings obtained from oral lesions as well as cultures positive for candida species (Thompson et al., 2010).

Several topical and systemic antifungal agents are currently available for the treatment of OPC. For mild disease, topical agents, including clotrimazole troches, miconazole mucoadhesive buccal, or nystatin suspension, are recommended (Pappas et al., 2016). For moderate to severe cases, oral fluconazole is recommended as first-line systemic antifungal agent (Pappas et al., 2016). Topical application to manage OPC minimizes drug interactions and adverse effects known to be associated with systemic antifungal agents; however, limitations exist such as local irritation, unpalatable taste, sugar content especially when used in patients with dental caries or uncontrolled diabetes, and lack of compliance due to the need for frequent administration (Sherman et al., 2002, Thompson et al., 2010).

As with all azole-type antifungal agents, clotrimazole primarily exhibits its pharmacological action through the inhibition of 14-α-lanosterol demethylation and, therefore, interferes with the biosynthesis of ergosterol, a major component of the fungal cell membrane (Hitchcock et al., 1990). For the treatment of OPC, clotrimazole is usually formulated to contain a 10 mg troche that is slowly dissolved in the mouth 5 times daily for 14 days (Crowley and Gallagher, 2014, Pappas et al., 2016). Several trials have evaluated the safety and efficacy of topical clotrimazole in the treatment of OPC but to date, no systematic review has been published to evaluate these findings. The aim of this review is to assess the safety and efficacy of topical application of clotrimazole versus others in the treatment of OPC taking into consideration all dosage regimens (dose, formulation, frequency, and duration) and all patient populations.

2. Materials and method

This review was performed according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Shamseer et al., 2015).

2.1. Search strategies

The search was conducted by two independent authors (TA and MA) who identified eligible studies through a comprehensive search of four databases: Medline through PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochran Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). These databases were searched up to November 2019 using Patients, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, and Study design (PICOS) strategy (Table 1). In our search strategy, the following terms were used in combination: (“candidiasis” OR “candidiosis” OR “oral candidiasis” OR “oral candidiases” OR “oropharyngeal candidiasis” OR “thrush” OR “candida stomatitis” OR “prosthetic stomatitis” OR “candida mucositis” OR “oral moniliasis” OR “rhomboid glossitis”) AND “clotrimazole” AND (“randomized controlled trial” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “randomized controlled study” OR “RCT”). Other sources were used to search for more studies, which include registries of ongoing trials: clinicaltrial.gov, controlled-trial.com, centerwatch.com, and world health organization portal. A hand search was conducted by checking the reference lists of articles retrieved.

Table 1.

PICOS strategy for clinical evidence.

| PICOS | Clinical Review |

|---|---|

| Population | Patients with oral candidiasis |

| Intervention | Clotrimazole used in treating oral candidiasis regardless of dosage regimen |

| Comparator | Placebo or other antifungal therapies |

| Outcome | Clinical response, mycological cure, relapse rate, and adverse outcomes |

| Study design | Published or unpublished randomized controlled trials of any size and duration |

2.2. Inclusion criteria

We included published and unpublished randomized controlled trials that compared the efficacy of clotrimazole to placebo or other antifungal agents in patients who were diagnosed with oral candidiasis with no restriction on age, gender, or race. Diagnosis of oral candidiasis was based on clinical signs and symptoms, which confirmed by positive potassium hydroxide smear examination and positive local fungal cultures. All formulations, dosages, and durations were considered in this review.

2.3. Outcome measure

Primary outcomes were clinical response rate defined as the cure or improvement of signs and symptoms attributable to the oral lesion as well as mycological cure rate defined as negative culture’s result. Secondary outcomes include relapse rate, the incidence of systemic infections, and compliance. Adverse effects were also evaluated.

2.4. Study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment

Two reviewers (TA and MA) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all identified studies. Selected studies were reviewed as full text for further assessment of inclusion. Double data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers (TA and MA).

For the quality assessment and risk of bias of the included studies, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions (Version 5.1.0) and the RevMan 5.3 software were used. Quality assessment was undertaken independently by two authors (TA and AA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Quantitative analyses of efficacy, including clinical, mycological, and relapse rate for clotrimazole were conducted using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) software. The efficacy outcomes were measured as odds ratio (OR), reported with its 95% confidence interval (CI), and plotted on a forest plot. Heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 index that ranged from 0% to 100%. We used the I2 value of 50% as the cutoff for significant heterogeneity. If no significant heterogeneity was detected, a fixed-effects model was used to determine the combined effect estimate. If significant heterogeneity was detected, fixed-effects and random-effects models were both used. Due to the limited number of studies reporting these outcomes and variability in the method of reporting, systemic infections, compliance, and adverse effects were evaluated using descriptive analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

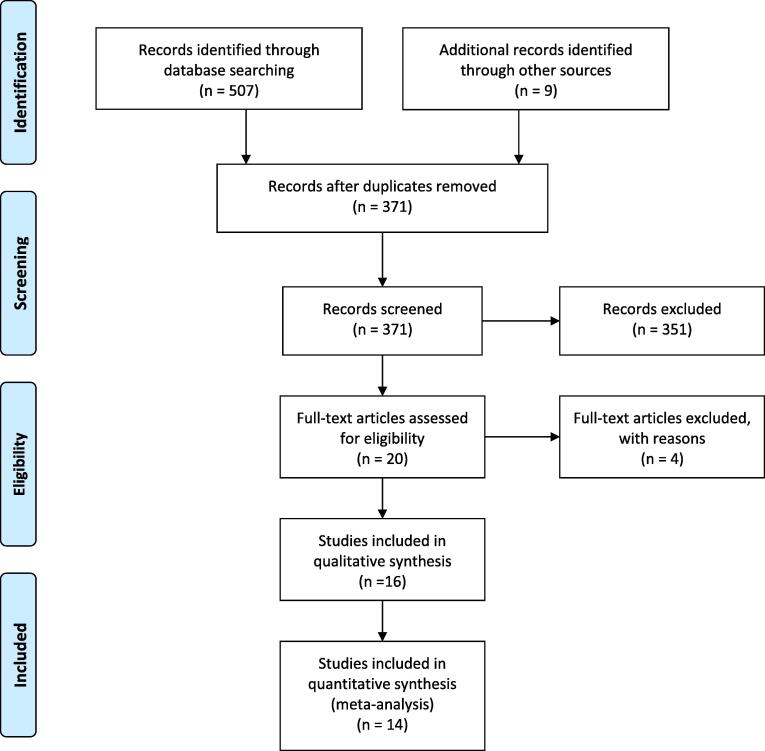

The initial search through the databases yielded 507 studies (Fig. 1). Duplicate studies (n = 145) were initially excluded using bibliographic management software (EndNote X8.1). Through the initial screening of the titles and abstracts of the remaining 371 results, 351 studies were excluded, among which, 331 studies were irrelevant, 12 studies were duplicates, 4 were nonclinical, and 4 studies in registries of ongoing trials were excluded due to either no results being available or participants not yet having been recruited. Full texts of the remaining 20 study manuscripts were thoroughly assessed for eligibility. Four studies were excluded because a primary outcome of interest was not clearly reported in one study, whereas three studies evaluated different outcomes than what we measure in this analysis. No study was excluded due to the unavailability of the full text version of the article. Sixteen trials were included in the systematic review.

Fig. 1.

Search strategy: Study selection process using preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA).

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

Sixteen trials were published between 1976 and 2010, and the majority were conducted in the United States. A total of 1685 patients were included with an average age ranging between 26 and 50 years. The clotrimazole troche was the formulation used in 14 studies. Clotrimazole 10 mg 5 times daily for 14 days was the most used regimen. Seven studies specifically addressed HIV patients and 3 studies restrictively included cancer patients. Comparators were placebo in 2 studies, fluconazole in 5 studies, itraconazole in 2 studies, nystatin in 2 studies, different doses of clotrimazole in 2 studies, as well as ketoconazole, miconazole and garlic, each in a single study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Year | Country | Total No. eligible patients | Mean age (years) | Diagnosis of OC | Clotrimazole |

Control |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation | Dose (mg) | Frequency (times/day) | Duration (days) | Medication | Formulation | Dose (mg) | Frequency (times/day) | Duration (days) | ||||||

| (Montes et al., 1976) | 1976 | USA | 12 | 32 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 10 | 14 | Clotrimazole | Troches | 50 | 10 | 14 |

| (Kirkpatrick & Alling, 1978) | 1978 | USA | 20 | 26 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Placebo | Troches | – | 5 | 14 |

| (Yap & Bodey, 1979) | 1979 | USA | 48 (52 episodes) | 44 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Clotrimazole | Troches | 50 | 5 | 14 |

| (Lawson & Bodey, 1980) | 1980 | USA | 84 (88 episodes) | 43 | C + M | Troches | 50 | 5 | 14 | Nystatin | Vaginal tablet | – | 5 | 14 |

| (Shechtman et al., 1984) | 1984 | USA | 16 | – | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 2–28 | Placebo | Troches | – | 5 | 2–28 |

| (Thamlikitkul et al., 1988) | 1988 | Thailand | 45 | 38 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 4 | 7 | Ketoconazole | Tablets | 200 | 1 | 7 |

| (Koletar et al., 1990) | 1990 | USA | 39 | 33 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Fluconazole | Capsules | 100 | 1 | 14 |

| (Conrad & Lentnek, 1990) | 1990 | USA | 86 | 40 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Nystatin | Pastille | 1–2 a | 5 | 14 |

| (Redding et al., 1992) | 1992 | USA | 24 | – | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Fluconazole | Tablets | 100 | 1 | 14 |

| (Pons et al., 1993) | 1993 | USA | 334 | 37 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Fluconazole | Capsules | 100 | 1 | 14 |

| (Sangeorzan et al., 1994) | 1994 | USA | 45 (82 episodes) | 39 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Fluconazole | Capsules | 100b | 1 | 14 |

| (Murray et al., 1997) | 1997 | USA | 162 | 40 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Itraconazole | Solution | 200 | 1 | 14 |

| (Linpiyawan et al., 2000) | 2000 | Thailand | 29 | 32 | – | Troches | 10 | 5 | 7 | Itraconazole | Solution | 100 | 2 | 7 |

| (Sabitha et al., 2005) | 2005 | India | 74 | – | C | 1% solution | 2–4 drops | 4 | 14 | Garlic | Paste | qs c | 4 | 14 |

| (Sholapurkar et al., 2009) | 2009 | India | 89 | 50 | C + M | mouth paint | - d | 3 | 14 | Fluconazole | Mouth rinse | - d | 3 | 14 |

| (Vazquez et al., 2010) | 2010 | USA | 578 | 37 | C + M | Troches | 10 | 5 | 14 | Miconazole | Buccal tab | 50 | 1 | 14 |

C = Clinical diagnosis; Co = control; I = intervention; M = mycological diagnosis; OC = oral candidiasis.

a. This is a 3-arm study: clotrimazole 10 mg vs 1 nystatin pastille (200,000 units) vs 2 nystatin pastilles (400,000 units).

b. After initial 200 mg dose.

c. Quantity sufficient to cover the entire lesion with one drop of 2% lignocaine jelly.

d. 1% mouth paint to be applied to affected area with index finger vs 2 mg/ml fluconazole in distilled water to rinse 5 ml for 2–3 min then swallow.

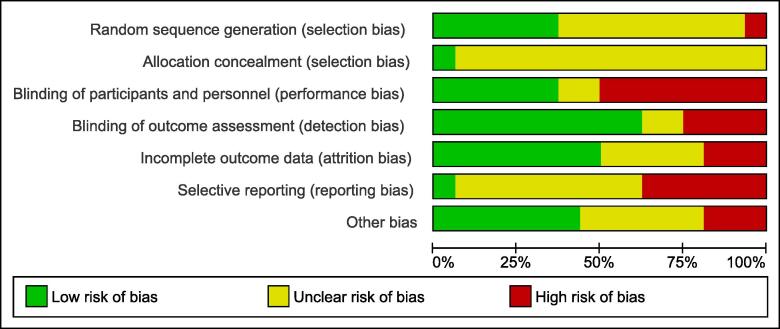

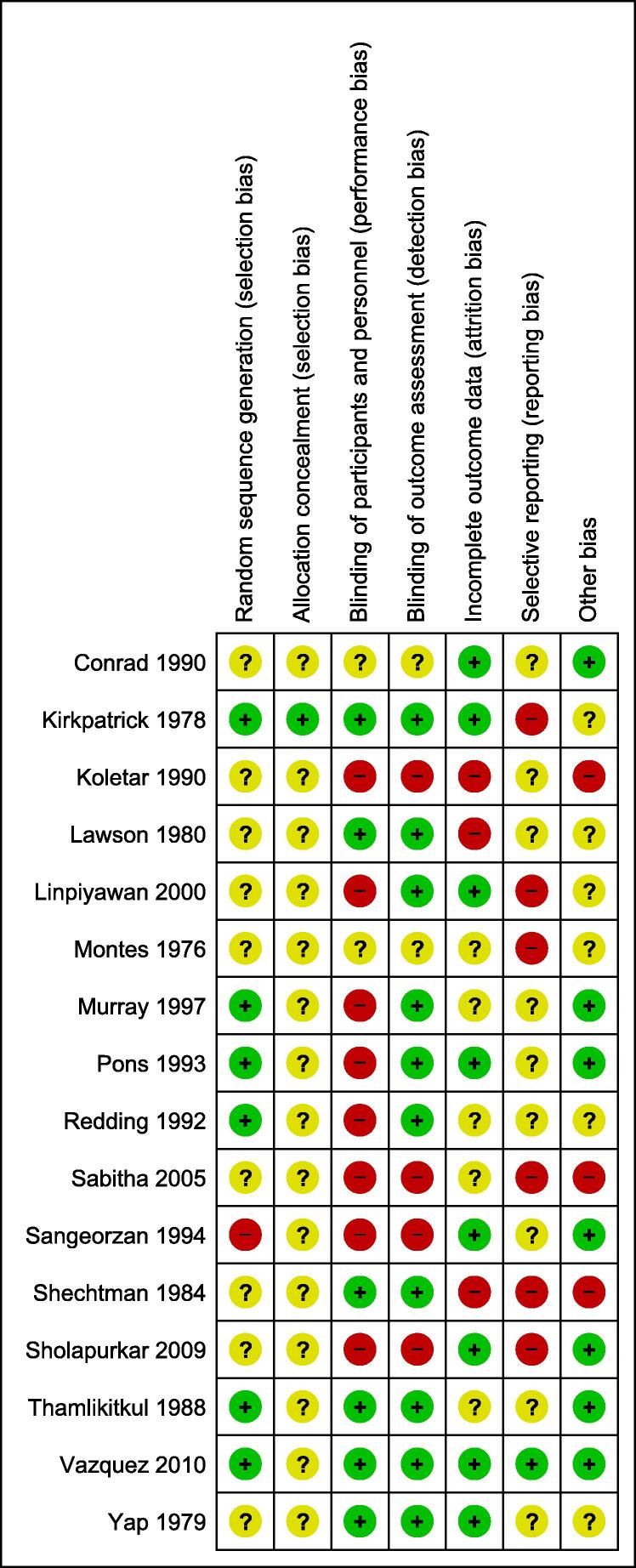

3.3. Study quality and risk of bias assessment

Half of the eligible studies were judged to have a high risk of performance bias, while 6 out of 16 studies were judged to have a high risk of reporting bias. Detailed risk of bias assessment for each included study and across all studies is summarized in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. There was a high agreement on the risk of bias assessment between authors.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgement about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgement about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.4. Efficacy assessment

Clinical and mycological outcomes of the individual studies are summarized in Table 3. Meta-analysis of clinical and mycological outcomes of clotrimazole is summarized in Table 4. Twelve studies compared the efficacy of clotrimazole to all other (topical and systemic) antifungal agents. Two studies were excluded from the overall quantitative analysis due to unclear reporting in one study while clinical and mycological outcomes were not assessed separately in the other study. An additional study was excluded from the quantitative analysis of mycological cure because a separate assessment for this outcome was not provided. Therefore, 10 studies were included in the quantitative analysis of clinical response and showed no significant difference (OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.65–1.11, I-squared = 45.0%) (Conrad and Lentnek, 1990, Koletar et al., 1990, Lawson and Bodey, 1980, Murray et al., 1997, Pons et al., 1993, Redding et al., 1992, Sabitha et al., 2005, Sangeorzan et al., 1994, Sholapurkar et al., 2009, Vazquez et al., 2010) while 9 studies were included in the quantitative analysis of mycological cure and showed that clotrimazole was significantly less likely to achieve mycological cure in a fixed-effects model (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.49–0.79, I-squared = 58.1%) and random-effects model (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.36–0.88, I-squared = 58.1%) (Koletar et al., 1990, Lawson and Bodey, 1980, Murray et al., 1997, Pons et al., 1993, Redding et al., 1992, Sabitha et al., 2005, Sangeorzan et al., 1994, Sholapurkar et al., 2009, Vazquez et al., 2010).

Table 3.

Clinical and mycological outcomes of clotrimazole versus control agents.

| Study | Specific population studied | Control | % Clinical response a (No. of clinical responses/Total evaluable patients) |

% Mycological cure b (No. of mycological cures/Total evaluable patients) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clotrimazole | Control | P-value | Clotrimazole | Control | P-value | |||

| (Montes et al., 1976) | Non-specific | Clotrimazole 50 mg | 100 (6/6) | 100 (6/6) | NS | 50 (3/6) | 50 (3/6) | NS |

| (Kirkpatrick & Alling, 1978) | Non-specific | Placebo | 100 (10/10) | 10 (1/10) | P < 0.001 | 90 (9/10) | 10 (1/10) | – |

| (Yap & Bodey, 1979) c | Cancer | Clotrimazole 50 mg | 96 (25/26) | 96 (25/26) | – | 34 (9/26) | 69 (18/26) | – |

| (Lawson & Bodey, 1980) c | Cancer | Nystatin | 94 (34/36) | 100 (30/30) | – | 56 (20/36) | 47 (14/30) | – |

| (Shechtman et al., 1984) | Cancer | Placebo | 86 (6/7) | 17 (1/6) | P = 0.025 | 43 (3/7) | 0 (0/6) | P = 0.12 |

| (Thamlikitkul et al., 1988) | Non-specific | Ketoconazole | 100 | 100 | – | 64 | 64 | – |

| (Koletar et al., 1990) | HIV | Fluconazole | 65 (11/17) | 100 (16/16) | P = 0.018 | 20 (3/15) | 75 (12/16) | P = 0.004 |

| (Conrad & Lentnek, 1990) | Non-specific | Nystatin | 83 (19/23) | 77 & 79 d | NS | 52 (12/23) | 29 & 47 d | NS |

| (Redding et al., 1992) | HIV | Fluconazole | 73 (8/11) | 100 (13/13) | NS | 63 (5/8) | 85 (11/13) | NS |

| (Pons et al., 1993) | HIV | Fluconazole | 94 (128/136) | 98 (149/152) | NS | 48 (56/118) | 65 (89/136) | P = 0.005 |

| (Sangeorzan et al., 1994) c | HIV | Fluconazole | 91 (31/34) | 96 (45/47) | NS | 27 (9/33) | 49 (22/45) | NS |

| (Murray et al., 1997) | HIV | Itraconazole | 70 (52/74) | 77 (58/75) | P = 0.349 | 32 (24/74) | 60 (45/75) | P < 0.001 |

| (Linpiyawan et al., 2000) | HIV | Itraconazole | 100 (15/15) e | 100 (12/12) | NS | – | – | – |

| (Sabitha et al., 2005) | Non-specific | Garlic paste | 87 (26/30) | 100 (26/26) | P > 0.05 | 50 (15/30) | 46 (12/26) | P > 0.05 |

| (Sholapurkar et al., 2009) | Non-specific | Fluconazole | 79 (22/28) | 96 (26/27) | P < 0.05 | 86 (24/28) | 89 (24/27) | NS |

| (Vazquez et al., 2010) | HIV | Miconazole | 69 (199/287) | 65 (188/290) | P = 0.1 | 25 (71/287) | 27 (79/290) | P = 0.58 |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; NS = not statistically significant

a. Defined as cure or improvement at end of treatment.

b. Defined as negative findings on culture or absence of pseudohyphae/budding yeast on smear at end of treatment.

c. Denominators in this study represent total number of episodes instead of total number of patients.

d. Clinical cure was 77% (13/17) in 1 nystatin pastille group vs 79% (15/19) in 2 nystatin pastilles group. Clinical plus mycological cure was 29% (5/17) in 1 nystatin pastille group vs 47% (9/19) in 2 nystatin pastilles group.

e. This is a global evaluation: a summary of clinical and mycological cure or improvement.

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of the efficacy of clotrimazole.

| Control | Clinical response |

Mycological cure |

Relapse |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | No. of patients | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No. of studies | No. of patients | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No. of studies | No. of patients | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

| Placebo | 2 | 33 | 61.63 (6.95–546.12) | 0 | 2 | 33 | 27.83 (3.15–246.12) | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| Fluconazole | 4 | 426 | 0.23 (0.09–0.57) | 0 | 4 | 384 | 0.40 (0.26–0.61) | 21.4 | 4 | 271 | FEM: 2.04 (1.17–3.55) REM: 3.45 (1.06–11.30) |

52.9 |

| Other topical and systemic agents | 10* | 1388 | 0.85 (0.65–1.11) | 45 | 9 | 1287 | FEM: 0.62 (0.49–0.79) REM: 0.56 (0.36–0.88) |

58.1 | 10* | 918 | 1.46 (1.08–1.97) | 17.6 |

| Other topical agents | 3* | 702 | 1.20 (0.87–1.67) | 0 | 2 | 643 | 0.93 (0.66–1.32) | 0 | 3* | 475 | 1.11 (0.73–1.70) | 0 |

FEM = fixed-effects model; REM = random-effects model.

*one of the studies was divided into 2 comparisons.

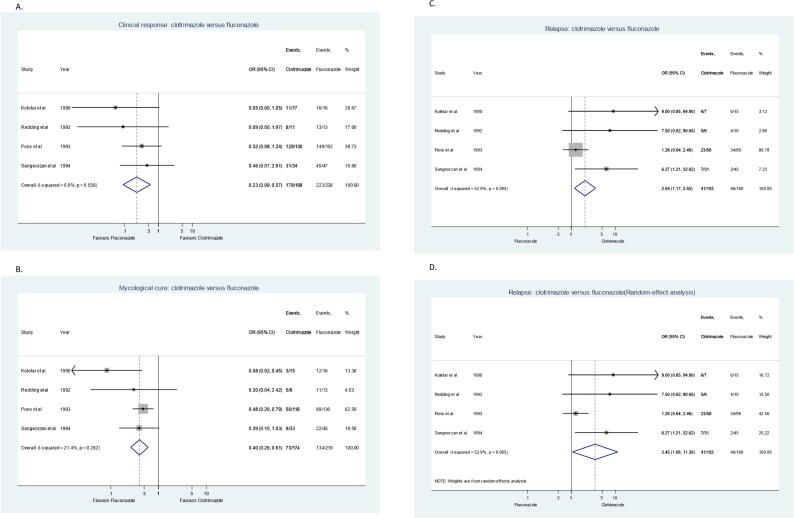

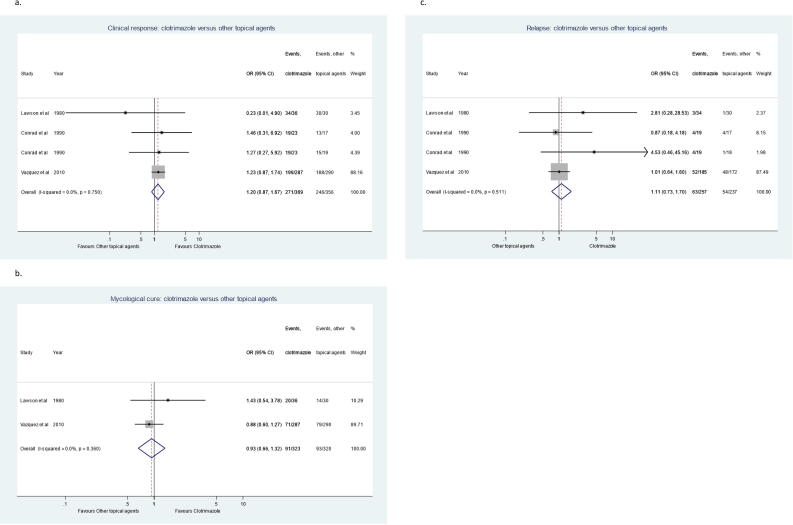

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to compare the efficacy of clotrimazole troches to fluconazole tablets or capsules (Fig. 4) and showed that clotrimazole is significantly less likely to achieve clinical response and mycological cure (clinical OR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.09–0.57; mycological OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.26–0.61) (Koletar et al., 1990, Pons et al., 1993, Redding et al., 1992, Sangeorzan et al., 1994). Moreover, when efficacy of clotrimazole was compared to only other topical antifungal agents (Fig. 5), there was no significant difference in meta-analysis for clinical response using data from 3 studies (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.87–1.67) (Conrad and Lentnek, 1990, Lawson and Bodey, 1980, Vazquez et al., 2010) and for mycological cure using data from 2 studies (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.66–1.32) (Lawson and Bodey, 1980, Vazquez et al., 2010). The reason for excluding one study for mycological cure was because a separate assessment for this outcome was not provided. Further sensitivity analysis was conducted to compare clotrimazole troches to placebo and reported that clotrimazole is significantly more likely to achieve clinical response and mycological cure (clinical OR = 61.63, 95% CI = 6.95–546.12; mycological OR = 27.83, 95% CI = 3.15–246.12) (Kirkpatrick and Alling, 1978, Shechtman et al., 1984).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots for the evaluation of clotrimazole versus fluconazole in the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. (A) Clinical response, (B) Mycological Cure, (C) Relapse rate (Fixed-effect analysis), and (D) Relapse rate (Random-effect analysis).

Fig. 5.

Forest plots for the evaluation of clotrimazole versus other topical antifungal agents in the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. (A) Clinical response, (B) Mycological Cure, (C) Relapse rate.

3.5. Safety assessment

Fifteen trials provided safety evaluations. Seven of the 15 trials reported an absence of adverse effects of clotrimazole while 8 trials reported specific adverse effects, gastrointestinal adverse effects being the most reported. An altered taste sensation, headache, dizziness, pruritus, rash, sweating, anemia, cough, dry mouth, fatigue, abnormal liver function tests, increased gamma-glutamyltransferase, and pain were also reported. The distribution of adverse effects of clotrimazole and comparators across studies is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Adverse effects of clotrimazole and controls.

| Study | No. of evaluable patients |

Control | Adverse effects of clotrimazole | Adverse effects of control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clotrimazole | Control | ||||

| (Montes et al., 1976) | 6 | 6 | Clotrimazole 50 mg | Pruritus in 1 patient | None |

| (Kirkpatrick & Alling, 1978) | 10 | 10 | Placebo | None | None |

| (Yap & Bodey, 1979) | 24 | 24 | Clotrimazole 50 mg | Nausea and abdominal pain in 1 patient (group not specified) | Nausea and abdominal pain in 1 patient (group not specified) |

| (Lawson & Bodey, 1980) | 36 episodes | 30 episodes | Nystatin | Nausea in 20 patients | Nausea in 3 patients |

| (Shechtman et al., 1984) | 7 | 6 | Placebo | – | – |

| (Thamlikitkul et al., 1988) | 23 | 22 | Ketoconazole | None | None |

| (Koletar et al., 1990) | 17 | 16 | Fluconazole | Nausea in 3 patients (2/3 discontinued therapy due to nausea and altered taste sensation) | Nausea in 3 patients |

| (Conrad & Lentnek, 1990) | 26 | 19 & 23 * | Nystatin | None | None |

| (Redding et al., 1992) | 11 | 13 | Fluconazole | Nausea in 2 patients | Flatulence in 1 patient |

| (Pons et al., 1993) | 158 | 176 | Fluconazole | Gastrointestinal in 22 patients;Headache, dizziness, pruritus, rash, sweating, or dry mouth in 13 patients | Gastrointestinal in 26 patients;Headache, dizziness, pruritus, rash, sweating, or dry mouth in 16 patients |

| (Sangeorzan et al., 1994) | 22 | 23 | Fluconazole | None | Rash in 1 patient |

| (Murray et al., 1997) | 81 | 81 | Itraconazole | Gastrointestinal in 20 patients, rash in 5 patients, headache in 5 patients, and abnormal liver function tests in 5 patients | Gastrointestinal in 21 patients, rash in 5 patients, and abnormal liver function tests in 7 patients |

| (Linpiyawan et al., 2000) | 15 | 14 | Itraconazole | None | Transient elevation in liver enzymes in 2 patients |

| (Sabitha et al., 2005) | 30 | 26 | Garlic paste | None | Bad odour in 5 patients |

| (Sholapurkar et al., 2009) | 28 | 27 | Fluconazole | None | Gastrointestinal in 1 patient |

| (Vazquez et al., 2010) | 287 | 290 | Miconazole | 152 patients reported ≥ 1 of the following: gastrointestinal, headache, anemia, cough, dry mouth, fatigue, increased GGT, and pain | 161 patients reported ≥ 1 of the following: gastrointestinal, headache, anemia, cough, dry mouth, fatigue, increased GGT, and pain |

GGT = gamma-glutamyltransferase; OC = oral candidiasis.

* 1 nystatin pastille group (n = 19); 2 nystatin pastille group (n = 23).

3.6. Secondary outcomes

The relapse of OPC was reported in 11 studies. Four studies (Koletar et al., 1990, Pons et al., 1993, Redding et al., 1992, Sangeorzan et al., 1994) reported the relapse of OPC after clotrimazole troches compared to fluconazole tablets or capsules (Fig. 4). Relapse of OPC was significantly higher after treatment with clotrimazole compared to fluconazole using a fixed-effects model (OR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.17–3.55, I-squared = 52.9%) and random-effects model (OR = 3.45, 95% CI = 1.06–11.30, I-squared = 52.9%). Ten studies reported the relapse of OPC after clotrimazole therapy compared to all other antifungal agents (topical and systemic) (Conrad and Lentnek, 1990, Koletar et al., 1990, Lawson and Bodey, 1980, Linpiyawan et al., 2000, Murray et al., 1997, Pons et al., 1993, Redding et al., 1992, Sangeorzan et al., 1994, Thamlikitkul et al., 1988, Vazquez et al., 2010). When data from these 10 studies were pooled in meta-analysis, relapse was significantly higher after clotrimazole therapy (OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.08–1.97). However, when relapse after clotrimazole therapy was compared to only other topical antifungal agents (Fig. 5), there was no significant difference when data from 3 studies were pooled in meta-analysis (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.73–1.70) (Conrad and Lentnek, 1990, Lawson and Bodey, 1980, Vazquez et al., 2010). Meta-analysis of relapse rate of clotrimazole are summarized in Table 4.

Two studies reported the incidence of systemic infections. In one study, 3 (12%) patients in clotrimazole 10 mg group versus 1 (4%) patient in clotrimazole 50 mg group developed systemic candidiasis after initially achieving clinical cure of OPC (Yap & Bodey, 1979). In the second study, 5 (14%) and 4 (13%) patients developed systemic candidiasis in clotrimazole and nystatin groups, respectively, despite having initial cure or improvement of oropharyngeal infection (Lawson & Bodey, 1980).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis exclusively and comprehensively analyzing the literature on efficacy and safety of clotrimazole in the treatment of OPC in various patient population. Although other systematic reviews in the treatment of OPC have been previously published, these either addressed other antifungal agents (Lyu et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2016) or specific patient population including patients with denture stomatitis, HIV, and cancer (Emami et al., 2014, Pienaar et al., 2010, Worthington et al., 2010).

This meta-analysis showed that clotrimazole is significantly more effective than placebo with regards to both clinical response and mycological cure of OPC. However, it showed that clotrimazole is significantly less effective than fluconazole in clinical response and mycological cure and associated with significantly more relapse. Although no significant difference was demonstrated in clinical response, clotrimazole was significantly less effective with regards to mycological cure rate and was associated with significantly more OPC relapse compared to other antifungal agents including both systemic and topical therapies when data from all studies were pooled in one analysis. However, when clotrimazole was compared to only other topical antifungal agents, no significant difference in clinical response, mycological cure, or relapse rate was demonstrated. Given the topical application of clotrimazole, adverse effects are expected to be mild. Gastrointestinal adverse reactions were the most frequently reported adverse effects and no serious reactions were reported. Our descriptive analysis of 2 studies demonstrated that systemic candidiasis may occur after topical antifungal therapy despite initial cure or improvement of OPC, although this occurred infrequently. The incidence rate of OPC did not significantly differ when clotrimazole 10 mg was compared to higher doses or to nystatin.

Topical antifungal agents, including clotrimazole, are often indicated for the management of OPC, because of their limited systemic exposure, adverse effects, and drug interactions usually associated with systemic antifungal therapies (Albengres et al., 1998). Furthermore, the growing trends of non-albicans species along with fluconazole-resistant C. albicans after repeated exposure may further intensify the importance of initiating topical antifungal agents particularly in mild cases (Patel et al., 2012).

In the 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis, clotrimazole troches, 10 mg 5 times daily was recommended as first line for the treatment of mild OPC (Pappas et al., 2016). However, the World Health Organization recommended clotrimazole only as an alternative agent when fluconazole is not available or contraindicated in HIV infected adults and children (“WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee,” 2014). Both guidelines supported their recommendations with a number of individual randomized controlled trials. Our review, however, focused solely on clotrimazole and included 16 randomized controlled trials that were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively for multiple efficacy outcomes using both fixed and random-effects models to provide more supportive evidence that may be considered in the future iterations of these guidelines.

A few limitations of this review should be highlighted. First, risk of bias cannot be excluded as several studies in this review were considered at high risk of performance bias and reporting bias. Moreover, all except one did not provide sufficient information about allocation concealment. In addition, although dosing regimens for clotrimazole and comparators such as fluconazole were similar across several studies, not all studies consistently evaluated the same formulation, dose, frequency, and duration of study medications. Few studies were excluded from the quantitative analysis due to unclear reporting of certain outcomes. Finally, approximately one-half the studies reported an absence of adverse effects related to clotrimazole therapy which might indicate inaccurate reporting leading to overestimation of its favorable safety profile. Therefore, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution.

In summary, clotrimazole is an effective agent for the treatment of OPC. Our analysis showed no significant difference in clinical response between clotrimazole and all other antifungal agents when data from all studies (including both topical and systemic agents) were pooled together in a single analysis. However, clotrimazole was less effective in terms of mycologic cure and relapse rate. Of note, when clotrimazole was compared exclusively to other topical antifungal agents, there were no differences in clinical response, microbiologic cure or relapse. Clotrimazole is significantly more effective than placebo but less effective than fluconazole. That makes clotrimazole a considerable alternative option to treat OPC when fluconazole is unavailable or contraindicated. Compliance with clotrimazole remains a major concern due to the need for multiple daily administration. High quality randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Thamer A. Almangour: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision. Keith S. Kaye: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Mohammed Alessa: Literature review and double data extraction. Khalid Eljaaly: Methodology. Fadilah Sfouq Aleanizy: . Aynaa Alsharidi: Review and Validation. Fahad M. Al Majid: . Naif H. Alotaibi: . Abdullah A Alzeer: Investigation, Methodology. Faris S. Alnezary: Investigation, Methodology. Abdullah A. Alhifany: Statistical analysis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through research group No (RG- 1441-437). We would also like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University for supporting this work by Grant Code:19-MED-1-02-0003.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Thamer A. Almangour, Email: talmangour@gmail.com, talmangour@ksu.edu.sa.

Keith S. Kaye, Email: keithka@med.umich.edu.

Fadilah Sfouq Aleanizy, Email: faleanizy@KSU.EDU.SA.

Aynaa Alsharidi, Email: aalsharidi@ksu.edu.sa.

Fahad M. Al Majid, Email: almajid@ksu.edu.sa.

Naif H. Alotaibi, Email: nalotaibi4@ksu.edu.sa.

Abdullah A Alzeer, Email: aalzeer@ksu.edu.sa.

Faris S. Alnezary, Email: falnezar@central.uh.edu.

Abdullah A. Alhifany, Email: falnezar@central.uh.edu, aahifany@uqu.edu.sa.

References

- Albengres E., Le Louet H., Tillement J.P. Systemic antifungal agents. Drug interactions of clinical significance. Drug Saf. 1998;18(2):83–97. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199818020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belazi M., Velegraki A., Fleva A., Gidarakou I., Papanaum L., Baka D., Karamitsos D. Candidal overgrowth in diabetic patients: potential predisposing factors. Mycoses. 2005;48(3):192–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnoni M.A., Souza R.F., Marra J., Pero A.C., Barbosa D.B. Relationship between Candida and nocturnal denture wear: quantitative study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2007;34(8):600–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad D.A., Lentnek A.L. Comparitive evaluation on nystatin pastille and clotrimazole troche for the treatment of candidal stomatitis in immunocompromised patients. Curr. Therap. Res. – Clin. Exp. 1990;47(4):627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley P.D., Gallagher H.C. Clotrimazole as a pharmaceutical: past, present and future. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014;117(3):611–617. doi: 10.1111/jam.12554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami E., Kabawat M., Rompre P.H., Feine J.S. Linking evidence to treatment for denture stomatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Dent. 2014;42(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah C.S., Lynch N., McCullough M.J. Oral fungal infections: an update for the general practitioner. Aust. Dent. J. 2010;55(Suppl 1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiral M.H., Azul A., Pinto E., Fonseca P.A., Branco F.M., Scully C. Denture-related stomatitis: identification of aetiological and predisposing factors – a large cohort. J. Oral Rehabil. 2007;34(6):448–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock C.A., Dickinson K., Brown S.B., Evans E.G., Adams D.J. Interaction of azole antifungal antibiotics with cytochrome P-450-dependent 14 alpha-sterol demethylase purified from Candida albicans. Biochem. J. 1990;266(2):475–480. doi: 10.1042/bj2660475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick C.H., Alling D.W. Treatment of chronic oral candidiasis with clotrimazole troches. A controlled clinical trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978;299(22):1201–1203. doi: 10.1056/nejm197811302992201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koletar S.L., Russell J.A., Fass R.J., Plouffe J.F. Comparison of oral fluconazole and clotrimazole troches as treatment for oral candidiasis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990;34(11):2267–2268. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson R.D., Bodey G.P. Comparison of clotrimazole troche and nystatin vaginal tablet in the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Curr. Therap. Res. – Clin. Exp. 1980;27(6 I):774–779. [Google Scholar]

- Linpiyawan R., Jittreprasert K., Sivayathorn A. Clinical trial: clotrimazole troche vs. itraconazole oral solution in the treatment of oral candidosis in AIDS patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2000;39(11):859–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu X., Zhao C., Yan Z.M., Hua H. Efficacy of nystatin for the treatment of oral candidiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:1161–1171. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s100795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millsop J.W., Fazel N. Oral candidiasis. Clin. Dermatol. 2016;34(4):487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes L.F., Soto T.G., Parker J.M., Ramer G.N. Clotrimazole troches: a new therapeutic approach to oral candidiasis. Cutis. 1976;17(2):277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P.A., Koletar S.L., Mallegol I., Wu J., Moskovitz B.L. Itraconazole oral solution versus clotrimazole troches for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Ther. 1997;19(3):471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naglik J.R., Challacombe S.J., Hube B. Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases in virulence and pathogenesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67(3):400–428. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.3.400-428.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G.D., Robinson P.G., Challacombe S.J., Birnbaum W., Croser D., Erridge P.L., Zakrzewska J.M. Aetiological factors for oral manifestations of HIV. Oral Dis. 1996;2(3):193–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1996.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas P.G., Kauffman C.A., Andes D.R., Clancy C.J., Marr K.A., Ostrosky-Zeichner L., Sobel J.D. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;62(4):e1–e50. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P.K., Erlandsen J.E., Kirkpatrick W.R., Berg D.K., Westbrook S.D., Louden C., Patterson T.F. The changing epidemiology of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with HIV/AIDS in the era of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res. Treat. 2012;2012:262471. doi: 10.1155/2012/262471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar E.D., Young T., Holmes H. Interventions for the prevention and management of oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with HIV infection in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;(11):Cd003940. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003940.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons V., Greenspan D., Debruin M. Therapy for oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: a randomized, prospective multicenter study of oral fluconazole versus clotrimazole troches. The Multicenter Study Group. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1993;6(12):1311–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding S.W., Farinacci G.C., Smith J.A., Fothergill A.W., Rinaldi M.G. A comparison between fluconazole tablets and clotrimazole troches for the treatment of thrush in HIV infection. Spec. Care Dentist. 1992;12(1):24–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1992.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabitha P., Adhikari P.M., Shenoy S.M., Kamath A., John R., Prabhu M.V., Padmaja U. Efficacy of garlic paste in oral candidiasis. Trop. Doct. 2005;35(2):99–100. doi: 10.1258/0049475054037084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangeorzan J.A., Bradley S.F., He X., Zarins L.T., Ridenour G.L., Tiballi R.N., Kauffman C.A. Epidemiology of oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: colonization, infection, treatment, and emergence of fluconazole resistance. Am. J. Med. 1994;97(4):339–346. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis. 2003;9(4):165–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Stewart L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechtman L.B., Funaro L., Robin T., Bottone E.J., Cuttner J. Clotrimazole treatment of oral candidiasis in patients with neoplastic disease. Am. J. Med. 1984;76(1):91–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman R.G., Prusinski L., Ravenel M.C., Joralmon R.A. Oral candidosis. Quintessence Int. 2002;33(7):521–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin E.S., Chung S.C., Kim Y.K., Lee S.W., Kho H.S. The relationship between oral Candida carriage and the secretor status of blood group antigens in saliva. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2003;96(1):48–53. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.S1079210403001604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholapurkar A.A., Pai K.M., Rao S. Comparison of efficacy of fluconazole mouthrinse and clotrimazole mouthpaint in the treatment of oral candidiasis. Aust. Dent. J. 2009;54(4):341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soysa N.S., Samaranayake L.P., Ellepola A.N. Antimicrobials as a contributory factor in oral candidosis–a brief overview. Oral Dis. 2008;14(2):138–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamlikitkul V., Danpakdi K., Visuthisakchai S., Kulpreedarat T. Randomized controlled trial of clotrimazole troche and ketoconazole for oropharyngeal candidiasis. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 1988;71(12):654–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G.R., 3rd, Patel P.K., Kirkpatrick W.R., Westbrook S.D., Berg D., Erlandsen J., Patterson T.F. Oropharyngeal candidiasis in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010;109(4):488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez J., Patton L., Epstein J., Ramlachan P., Mitha I., Noveljic Z., Attali P. Randomized, comparative, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter trial of miconazole buccal tablet and clotrimazole troches for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis: study of miconazole lauriad<sup>®</ sup> efficacy and safety (SMiLES) HIV Clin Trials. 2010;11(4):186–196. doi: 10.1310/hct1104-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- . WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee, 2014. In: Guidelines on the Treatment of Skin and Oral HIV-Associated Conditions in Children and Adults. Geneva: World Health Organization Copyright (c) World Health Organization. [PubMed]

- Worthington H.V., Clarkson J.E., Eden O.B. Interventions for preventing oral candidiasis for patients with cancer receiving treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002;(3):Cd003807. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd003807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington H.V., Clarkson J.E., Khalid T., Meyer S., McCabe M. Interventions for treating oral candidiasis for patients with cancer receiving treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;(7):Cd001972. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001972.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap B.S., Bodey G.P. Oropharyngeal candidiasis treated with a troche form of clotrimazole. Arch. Intern. Med. 1979;139(6):656–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.W., Fu J.Y., Hua H., Yan Z.M. Efficacy and safety of miconazole for oral candidiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2016;22(3):185–195. doi: 10.1111/odi.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.