Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ultrasonic emulsification, W/o and o/w emulsions, Microfluidics, In-line emulsification, Polymeric particles synthesis, High-power ultrasound

Highlights

-

•

Fast generation of W/O and O/W emulsions with low-reagent consumption.

-

•

Images show the initial formation of the emulsion by cavitation bubbles.

-

•

Emulsion droplet diameter is independent of ultrasound power.

-

•

Emulsions with different HLB values were formed in continuous flow.

-

•

Submicron polymeric particles with low dispersity were synthesized from miniemulsions.

Abstract

The use of ultrasound to generate mini-emulsions (50 nm to 1 μm in diameter) and nanoemulsions (mean droplet diameter < 200 nm) is of great relevance in drug delivery, particle synthesis and cosmetic and food industries. Therefore, it is desirable to develop new strategies to obtain new formulations faster and with less reagent consumption. Here, we present a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microfluidic device that generates oil-in-water or water-in-oil mini-emulsions in continuous flow employing ultrasound as the driving force. A Langevin piezoelectric attached to the same glass slide as the microdevice provides enough power to create mini-emulsions in a single cycle and without reagents pre-homogenization. By introducing independently four different fluids into the microfluidic platform, it is possible to gradually modify the composition of oil, water and two different surfactants, to determine the most favorable formulation for minimizing droplet diameter and polydispersity, employing less than 500 µL of reagents. It was found that cavitation bubbles are the most important mechanism underlying emulsions formation in the microchannels and that degassing of the aqueous phase before its introduction to the device can be an important factor for reduction of droplet polydispersity. This idea is demonstrated by synthetizing solid polymeric particles with a narrow size distribution starting from a mini-emulsion produced by the device.

1. Introduction

Using ultrasound to create oil-in-water or water-in-oil mini-emulsions (50 nm to 1 µm in diameter [1]) and nanoemulsions (mean droplet diameter < 200 nm [2]) is a common procedure in the laboratories involved in hydrophobic drug delivery [3], [4], [5], cosmetic formulations [6], food preparation [7], [8] and nanoparticle synthesis [9], [10]. Essential characteristics of these mini-emulsions are their capability of crossing biological barriers [3], [11]; their enhanced kinetic stability with respect to conventional emulsions (droplet diameter > 1.0 µm) [12]; the possibility of tuning their rheological properties [13] and their ability to increase the rate and selectivity of many chemical reactions occurring at their abundant aqueous-organic interfacial areas [14], [15].

The formation of kinetically stable mini-emulsions requires careful selection of surfactants and stabilizers depending on the amount and chemical nature of the continuous and dispersed phases. Equally important is the methodology employed for the mini-emulsions formation, which can be classified in a high- or low-energy method [16], [17]. Despite some guidelines for selecting an appropriate surfactant and a suitable technique for mini-emulsions formulation, it is common to find the best solution by an iteration process [18], [19]. As nano- and mini-emulsions become more relevant in industry and research, it would be desirable to count on a convenient and reliable method for small scale testing of emulsion formulations. Microfluidics technology handles accurately µL-pL volumes, and this characteristic could be used to formulate mini-emulsions with very low volumes. Also, creating microfluidics protocols that allow for testing many different reagents combinations in short times could be useful to tailor specific characteristics or functionalities for a particular mini-emulsion, without the cost of large reagents consumption.

Low-frequency ultrasonication (20–100 kHz) is a high-energy method widely used for macroscale emulsion formulations [20]. In microfluidic channels the use of low-frequency ultrasound generates cavitation bubbles [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], which have been used for DNA fragmentation [26], cell disruption [27], [28], generation of chemi- and sonoluminescence [29], mixing of low and high-viscosity fluids [30], [31], dissolution of gas bubbles in water [32] and liquid–liquid extraction process [33], [34]. The demonstration of emulsion preparation using ultrasound in microfluidic devices has been described in conference proceedings [35], [36], [37], and in two research articles some of the mechanism of octane and water emulsification have been reported [33], [34]. Different small-scale reactors with sonication have been explored for preparing mini-emulsions and the size and polydispersity of the emulsion droplets have been measured: a glass flow-through cell with a 2.0 mm inner diameter [38], epoxy resin channels with a 1.0 – 1.5 mm in diameter [39] and an ultrasonic bag reactor with microstructures inside which can be considered as a scaled-up microfluidic sonoreactor [40].

Guided by previous reports of ultrasound-assisted microfluidic devices [22], [26], we developed a PDMS-based microfluidic platform that incorporates a continuous flow microreactor with four inlet channels that permits mixing different amounts of oil, water and surfactants to generate oil-in-water or water-in-oil mini-emulsions employing high-power ultrasound as the driving force. This microfluidic device provides a microscale method for rapidly finding formulations that minimize the emulsion droplet size and polydispersity and permits observation of some underlying mechanisms of emulsion formation in the microchannels.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ultrasound-assisted microfluidic devices

Microchips were constructed using conventional photolithography techniques [41]. In brief, master molds of SU 8–3035 (MicroChem) with 174 ± 4-µm-height were built over silicon wafers. The design of the microchip includes four inlet channels of 60 ± 3-µm-wide, two for the aqueous phase and two for the oil phase. Each pair of channels merges at a Y–junction into 160 ± 2-µm-wide channels, which merge again into a single serpentine channel 290 ± 4–µm-wide and 7.01 cm long. The master molds were used to cast polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) devices with a relation of 10:0.9 of PDMS:curing agent (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning). The microchips were bound to 1.0 mm thick glass slides (2947-75X50, Corning) using oxygen plasma treatment (Corona Treater, BD-20AC, Electro Technic Products). The fluids were introduced into the device at different constant flows using syringe pumps (NE-1000, New Era Pump Systems). In the same glass slide, a Langevin piezoelectric with a resonant frequency of 61 kHz (SMBLTF60W25, Steminc) was attached using epoxy glue [26]. A sinusoidal electrical signal at 61 kHz (typically at ± 1.0 V) was produced with a function generator (UTG 9000C, Unit-T) and was magnified (100 × ) with a power amplifier (PZD 350A, Trek) to feed the piezoelectric. An attenuated signal of the current intensity and voltage from the amplifier were recorded in an oscilloscope (UTD 2000, Unit-T) for electrical power calculations. A custom made microscope slide holder fabricated with cardboard was used to mount the microfluidic sonication device in which only the edges of the glass substrate were in contact with the holder and the center was suspended in air [22]. An external fan was used to keep the piezoelectric and microfluidic device cool during operation, but still, we recorded a temperature rise from 20 °C (controlled room temperature) to 32–35 °C inside the device using a non-contact IR thermometer.

2.2. Mini-emulsions in the microfluidic device

Emulsions were prepared using four fluids: a) pure hexadecane 99% (Sigma-Aldrich) as an oil phase (O); b) ultrapure water (Milli-Q) as an aqueous phase (W); c) solutions of a nonionic oleophilic surfactant, Span 80 (Sigma-Aldrich) in hexadecane at different concentrations (S80) and d) solutions of a nonionic hydrophilic surfactant, Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich) in water at different concentrations (T80). We produced three sets of mini-emulsions with different water-to-hexadecane weight ratios: W:O = 9:1, W:O = 1:1 and W:O = 1:9 all with 2% (w/w) of total surfactants. Within each set, the relative amount of Span 80 and Tween 80 was varied to obtain different hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) of the surfactants in the emulsions. The HLB value of the mixture (HLBmix) can be calculated as: HLBmix = HLBS80 xS80 + HLBT80 xT80, where: HLBS80 and HLBT80 are the HLB value of pure Span 80 = 4.3 and pure Tween 80 = 15, respectively, and xS80 and xT80 are the weight fraction of Span 80 and Tween 80, respectively, considering only the weight of the surfactants (xS80 + xT80 = 1). Using the densities of the aqueous and oil phases with or without surfactants, individual fluid flow can be obtained by keeping the total flow fixed at 1 mL/h (Fig. 1). We used hexadecane as model oil as it does not significantly swells PDMS in comparison with other small size alkanes [42], and it has been used to prepare model mini- and nanoemulsions with water [43], [44]. The surfactants employed here are also used to model the HLB effect [16].

Fig. 1.

Example of the flow rates employed to prepare the W:O = 9:1 mini-emulsions set with different mixtures of Span 80 and Tween 80 solutions to obtain distinct HLB values at fixed W:O ratios. The total flow was always 1 mL/h. Seven different HLB values for this set of mini-emulsions are indicated with vertical dotted red lines. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.3. Video and image acquisition

Microphotographs and videos of the working microdevice were acquired with a high-speed camera (Phantom Miro M110, Vision Research) coupled to an inverted microscope (DMI3000-B, Leica). Color fluorescent images were obtained with a conventional digital camera (Canon Power Shot SX260 HS) mounted in the microscope ocular using Epifluorescent light (PhotoFluor II, 89 North) and fluorescent cubes (FITC-5050A: λex = 450–500 nm, λem = 515–565 nm or LF561/LP-C: λex = 554–568 nm, λem > 575 nm, Semrock). Fluorescein sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in water (12 µM) or Nile red (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in hexadecane (0.35 µM) were used to dye the aqueous or oil phase, respectively.

2.4. Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

The hydrodynamic size and size distribution of emulsion droplets were measured (10 runs of 5 s each) at 25 ˚C with a DLS equipment (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern). The emulsions were diluted in deionized water or in hexadecane in a ratio of 1:50 a few minutes after formation and the measurements were taken immediately. The polydispersity Index (PDI) was obtained from the equipment software that uses the cumulants analysis.

2.5. Synthesis of polymeric particles

We prepared an O/W emulsion (1:9 vol ratio) using the ultrasound assisted microfluidic device. The oil phase consisted in a mixture of 1,6-hexanediol diacrylate with 1-hydroxycyclohexyl phenyl ketone as photo initiator (1% w/w) and was introduced into the device at 0.1 mL/h. The aqueous phase was a 10 mM solution of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which was infused at 0.9 mL/h. In some experiments the aqueous phase was previously degassed by sonication in a water bath for 5 or 30 min before being introduced to the device. The mini-emulsion coming from the microdevice (1 mL) was collected in a vial filled with 5 mL of 10 mM SDS solution with constant stirring and then irradiated by UV light (100 W, B100AP, Analytik Jena) for 1 h to complete solidification of oil droplets. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used to determine particle size and size distribution. The diameter of at least 300–450 particles from three independent experiments were obtained using the ImageJ software [45]. This data were used to calculate the volume-weighted particle size distribution to account for the large particles found in the experiment without water degasification. The average particle diameter 〈 D 〉and the standard deviation, σ, of 〈 D 〉were obtained from the fitting parameters of a Gaussian curve to the volume-weighted distribution and the particles PDI was calculated as σ/ 〈 D 〉.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Microchip design and operation

The microfluidic device was fabricated in PDMS with four inlet channels that merge into a serpentine channel with a single outlet (Fig. 2a). These four inlets allow continuous feeding of two aqueous phases (e.g. pure water (W) and water with Tween 80 (T80)) and two oil phases (e.g. pure hexadecane (O) and hexadecane with Span 80 (S80)) into the device. Since the injection flow rate at each inlet is programmable and independent, it is possible to modify the feed ratio of each component, allowing the amount of each surfactant to change while keeping the water-to-oil ratio constant. To obtain mini-emulsions with the incoming water–oil mixtures, we energized a Langevin piezoelectric transducer attached to the same chip glass slide at its resonant frequency and continuously collected the mini-emulsions at the end of the device for their characterization.

Fig. 2.

a) PDMS microfluidic device for mini-emulsions generation. Four inlet channels labeled i1 to i4 help to introduce water and oil phases with or without surfactants and merge the liquids into a single serpentine channel. The microchip is bound to a glass slide together with a Langevin piezoelectric transducer. Introducing the liquids in continuous flow and energizing the piezoelectric produces mini-emulsions. b) Finite element method (FEM) simulation of the vibration displacements in the Z-axis of the microfluidic slide at the piezoelectric resonant frequency of 61 kHz.

The piezoelectric transducer was centered on the slide x-axis and 1.0 cm from the slide edge along the y-axis, while the PDMS device was oriented so that the inlets were closer to the piezoelectric, and the outlet was on the opposite side (Fig. 2a). This configuration was chosen to give the maximum acoustic energy to the fluids at the beginning of the serpentine [26]. We also performed a simulation of the behavior of the ultrasonic waves on the chip glass slide using the finite element method (FEM) at the nominal resonant frequency of the piezoelectric (61 kHz) (Fig. 2b). The orange circle in Fig. 2b is the piezoelectric attachment area. In this place vibrations are longitudinal, while out of this zone the vibrations become flexural waves that travel radially outward from the piezoelectric transducer along the glass slide interacting with the PDMS microchip. The oscillation amplitude of the flexural waves decreases along the radial direction of the x-y plane. Although we have not experimentally measured the vibration displacement in our system, a similar behavior of the radial decrease has been previously reported [26] as well as a maximum displacement amplitude of 0.24 or 1.2 µm for the glass surface with or without a PDMS attached using an equivalent glass slide and piezoelectric transducer [26].

The oscillation amplitude of the flexural waves decreases along the radial direction of the x-y plane. Although we did not experimentally measured the vibration displacement in our system, a similar behavior of the radial decrease has been reported [26] as well as a maximum displacement amplitude of 0.24 or 1.2 µm in the glass surface with or without a PDMS attached using an equivalent glass slide and piezoelectric transducer [26].

3.2. Power effect on mini-emulsions formation and droplet size

We tested the effect of the electrical power supplied to the piezoelectric on the formation of mini-emulsions (W:O = 9:1; HLB = 15) within the microdevice by monitoring the changes in the emulsion under the microscope while continuously increasing the power. Samples of the mini-emulsions were collected and analyzed by DLS at different power intervals. In the range of 0.0 – 0.9 W (0–0.02 W/cm2), stable large oil in water droplets were formed without any other effects noticed (Fig. 3a). In the second power range of 0.9 – 1.9 W (0.02–0.05 W/cm2), droplet destabilization with some coalescence was observed (Fig. 3b). From 2.0 W (0.05 W/cm2) the threshold for cavitation bubbles formation is reached and they can be observed throughout the channel, but neither their number nor their energy are sufficient to homogenize the entire sample so that large regions of non-emulsified fluids are visible (Fig. 3c). This behavior is observed up to 4.8 W (0.13 W/cm2), since at higher power the formation of cavitation bubbles throughout the entire microchannel is uniform and more energetic, therefore, the fluids are completely emulsified (Fig. 3d). In the interval of 4.8 – 25 W (0.13–0.67 W/cm2), we collected emulsion aliquots and measured the droplet hydrodynamic diameter by DLS. We found that the mean value did not change significantly with the power increase in this range, with an average diameter of 280 ± 30 nm (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Effect of the electrical power on the mini-emulsification process and on the mean droplet diameter. (a) Within the range of 0–0.9 W, stable micron-size droplet formation is observed. (b) In the range of 0.9 – 1.9 W, some droplet coalescence is observed. (c) At 2.0 W the cavitation threshold is reached and emulsification starts to occur, but several zones showed poor emulsification. This behavior is observed up to 4.8 W. (d) Above 4.8 and up to 25 W (maximum power tested), a homogeneous mini-emulsion was produced in all the microchannels. (e) The average droplet diameters of ten different experiments in the 4.8–25 W range are plotted in the graph (red dots). The mean of all data (280 nm) is shown with a green line and the standard deviation is represented with a shaded green area (±30 nm). Total flow = 1000 μL/h; water:hexadecane ratio is 9:1 with 2% w/w of Tween 80. Scale bar = 300 µm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

It has been shown that there is a threshold in the sonication power to form emulsions [46], and once this threshold is achieved, initial droplet diameters and polydispersity can be exponentially reduced by increasing the power input, but only up to a certain lower limit [47], [48]. After that, the size is insensitive to sonication power and in fact, higher power can result in larger droplets [44], [46], [47]. Different explanations have been given for this observation: first, a power increase leads to heating and an increment in the number of cavitation bubbles, which shields the energy transfer and prevents droplet rupture [20], [44]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that at higher potency, the droplets coalesce more easily and therefore, grow [46], [47].

Fig. 3 shows that a 2.0 W threshold is needed to start mini-emulsion formation in the microfluidic device. In the region between 2.0 and 4.8 W it is likely that the emulsion had a high polydispersity and large droplet diameters due to the instability in its formation. However, after reaching 4.8 W the droplet size is insensitive to the power input. Thus, in all the following experiments we used a power of 15.0 W. This corresponds to an energy consumption of 5.4 × 1010 J/m3 considering a flow rate of 1 mL/h, which is about 5 to 10-fold higher than the emulsions with 10% of hexadecane prepared at 80 kHz inside ultrasonic bag-reactors [40]. However, there is room for increasing the emulsification efficiency in our device, as higher flow rates can be tested as well as other piezoelectrics with lower resonance frequencies that consume less power [40].

3.3. Cavitation as the driving force for mini-emulsion generation

3.3.1. Cavitation in pure liquids inside the microfluidic device

Cavitation has been demonstrated to be the force for two-phase mixing and droplet rupture in the emulsification process when ultrasound is employed [49]. To form cavitation bubbles, the amount of dissolved gas and vapor pressure of the fluids are important factors to be considered [50]. For that reason, we first explored the effect of ultrasound on the individual liquid phases inside the microdevice, with or without previous degasification. In the first experiment, ultrapure water without degasification was introduced in the device and the piezoelectric was switched on. We observed the formation of cavitation bubbles (~5 – 20 µm diameter) on the glass surface (Fig. 4a) and along the microchannel PDMS sidewalls (Fig. 4b and 4c). At the interface between glass and PDMS, some stable cavitation bubbles were noticed, while on the PDMS walls, transient cavitation was more prevalent and the bubbles presented steady growth, dissolution, fragmentation (Fig. 4d-f), jetting, microstreaming (Video 1), free floating and fusion [51]. These bubbles could oscillate about a fixed position for 1–3 ms, and then show fast displacements backwards and forwards in the channel, even at counterflow speeds as large as 5.2 mm/s (Fig. 4g-j).

Fig. 4.

Ultrasound effect on deionized water or hexadecane inside the microchannels. a) Bubbles attached to the glass surface are observed when water without degasification treatment is flown through the microdevice and the piezoelectric turned on. Scale bar = 70 µm. b) A section of the serpentine microchannel with flowing water and the piezoelectric turned off. The PDMS structures were shaded for clarity of the picture. Scale bar = 300 µm. c) The same section of the microchannel as in b) but with the piezoelectric turned on. Many cavitation bubbles are observed mainly along the PDMS walls. Scale bar = 300 µm. d-f) A cavitation bubble on top of a PDMS wall oscillates and fragments into secondary bubbles that move in opposite directions. Scale bar = 10 µm. g-j) A cavitation bubble moves along a PDMS walls in counterflow. Scale bar = 10 µm. k) Microphotograph of a channel section filled with pure water degassed for 30 min before its injection into the microchip. Only a few bubbles are observed when the piezoelectric is turned on. Scale bar = 70 μm. l) Microchannel section filled with pure hexadecane without degasification and the piezoelectric turned on. Only a few bubbles are observed (enclosed by the red circles). Scale bar = 70 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In a second experiment, water was degasified in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min prior to its injection into the microchannel. In this case, when the piezoelectric was turned on, the number of observed bubbles was greatly reduced in comparison with the previous test (Fig. 4k). Pure hexadecane was also injected in the microdevice without degasification and subjected to ultrasonication. Also in this case very few stable cavitation bubbles were observed compared to the untreated water (Fig. 4l). Together the results indicate that the air dissolved in water greatly enhances the formation of cavitation bubbles, which are essential for the mini-emulsion formation as explained below.

3.3.2. Cavitation in water-hexadecane mixtures

When the piezoelectric is energized and water and hexadecane are simultaneously introduced into the device, numerous cavitation bubbles appear at the interface between the PDMS and glass mainly in the channels introducing the aqueous phase. Very quickly the cavitation bubbles appear and spread throughout the whole serpentine microchannel giving a creamy emulsion. This emulsion is completely opaque under the optical microscope, therefore, to observe the emulsification mechanism, we used a high-speed camera to capture the initial moments of mixing. Fig. 5a shows one of the cavitation bubbles attached to the glass-PDMS interface acting as an emulsifying element through a microvortex when water and hexadecane flows meet (Video 2). These microvortexes capture and break oil droplets into smaller ones and are the main responsible for emulsification of the liquids. The cavitation bubbles move fast along the microchannel sidewall in the direction of the flow or against it, contributing further to the oil droplet rupture. Many of them, after a few milliseconds, fragment in two or more smaller droplets creating high-speed jets and some times they reduce their size by scattering or shooting tiny bubbles into the fluid. Similar behaviors have been observed in the mixing of two aqueous streams assisted by ultrasound [31].

Fig. 5.

a) Microvortex generated by a cavitation bubble as an emulsifying element captured by a fast camera at 20,000 fps (Video 2). W:O ratio 2:1 with 2% w/w of Tween 80. Total flow rate is 300 µL/h. Scale bar = 10 µm. b–e) Microphotographs of a large water droplet disrupted by a trapped air bubble (red arrow) presenting microstreaming captured at 60 fps (Video 3). O = hexadecane with 2% w/w of Span 80; W = water; E = emulsion. W:O ratio 1:1. Total flow rate 400 µL/h. The time interval between each microphotograph is 79 ms. Scale bar = 300 µm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In one of our initial trial devices we observed an air bubble trapped on a PDMS wall within a manufacturing defect in the shape of a cavity. This large bubble (~50 µm) presented steady cavitation, which generated a larger microvortex that helped to break and emulsify a micrometer-size water droplet moving in the microchannel together with the continuous hexadecane medium. Fig. 5b-e presents a sequence of microphotographs of this process. On the right side of the photos emulsion formation can be observed (see Video 3). The speed and flow strength in the surroundings of a comparable trapped acoustic bubble have been measured by particle tracking velocimetry [52] and a similar approach could be followed to design pits [40] or sharp microstructures [27] along the channel that could seed or trap cavitation bubbles that harness the ultrasonication energy in a more controlled and efficient way [25].

3.4. Formation of gas/vapor bubbles in the device

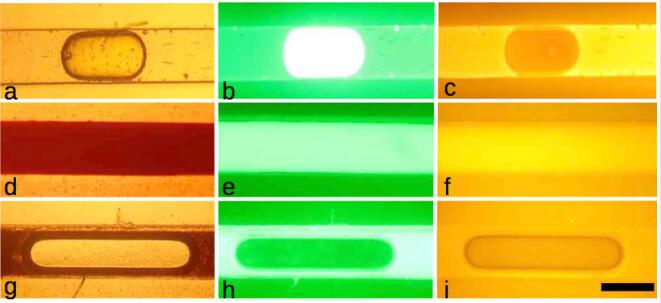

Once formed throughout the sono-emulsification process, the mini-emulsion flows continuously along the microchannel. However, occasionally, emulsion void regions (~2.0 mm long) were visible along the serpentine microchannel and in the exit tubing. We identified that these regions are most likely air bubbles and ruled out the possibility that micron size water droplets or large oil plugs were left without emulsification by performing the following tests. Nile red, a hydrophobic fluorescent dye, was dissolved in hexadecane with Span 80, while fluorescein sodium salt, a hydrophilic fluorescent dye, was dissolved in water. Both solutions were introduced into the microdevice with the piezoelectric turned off. Water-in-oil droplets were formed and observed under a fluorescent microscope equipped with two specific fluorescent filter sets for the employed dyes. In the first row of Fig. 6, a water droplet in oil is observed in a bright field image (Fig. 6a). A fluorescence image of the same water droplet collected with filters that allow emission only from fluorescein molecules shows a very bright droplet while the oil remains dark (Fig. 6b). The same water droplet was imaged in Fig. 6c, but now with filters that allow emission only from Nile red in the oil. In this case the oil surrounding the droplet fluoresces, while the water droplet remains dark (Fig. 6c). The second row of Fig. 6 shows the microphotographs of a mini-emulsion formed in the microchannels after the ultrasonication process. In the bright field image, the mini-emulsion appears opaque (Fig. 6d), while in the fluorescent images, it shows homogeneous fluorescence with both filter sets (Fig. 6e and 6f) because the water droplets containing fluorescein are homogeneously dispersed in hexadecane dyed with Nile red. The third row of Fig. 6 shows a bubble formed during the emulsification process. In bright field, the bubble appears transparent, while the surrounding mini-emulsion appears dark (Fig. 6g). With the first set of filters, the bubble does not fluoresce, indicating the absence of water with fluorescein inside it (Fig. 6h). Finally, an image acquired with the Nile red fluorescent filters shows no brightness in the bubble, also indicating the absence of hexadecane with Nile red in its interior (Fig. 6i). These tests show that the bubble is a non-condensed phase, most likely formed by air and water vapor coming from the non-degasified water. These large air bubbles are displaced by the mini-emulsion flow within the microchannel and do not interfere with the characterization of the mini-emulsion.

Fig. 6.

(a-c) Color microphotographs of a micrometer-size droplet of water with fluorescein sodium salt in a continuous medium of hexadecane with Nile red. a) Bright field. b) Fluorescent image acquired with filters for fluorescein in water. c) Fluorescent image acquired with filters for Nile red in hexadecane. d–f) Color microphotographs of a W/O mini-emulsion stained with fluorescein and Nile red in bright field and the same filter sets mentioned above. g–i) Color microphotographs of an air bubble surrounded with the mini-emulsion stained with fluorescein and Nile red. The air bubble does not fluoresce with any filter set. W:O ratio is 1:9 and 2% w/w of Span 80. Scale bar = 300 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. Formation and characterization of O/W or W/O mini-emulsions over a range of HLB values

Small droplet size and low polydispersity are two important properties that are sought after when formulating mini-emulsions. One of the critical factors to test is the composition of the surfactants employed. This can be achieved by scanning the relative concentrations of the surfactants to find an HLB value that provides the desired characteristics [53], [54], [55]. Our microfluidic system allows HLB screening to be performed very easily and quickly with low amount of reagents. The four-inlet microfluidic device shown in Fig. 1a was fed with pure water (W) and water with Tween 80 (T80) at inlets i1 and i2. Meanwhile, pure hexadecane (O) and hexadecane with Span 80 (S80) were fed into inlets i3 and i4. With this configuration both, the total flow and water-hexadecane ratio can be kept constant, while changing the surfactant composition varying the HLB over the whole accessible range possible with Span 80 and Tween 80 (HLB = 4.3 to 15). We formulated O/W and W/O emulsions using three different water:hexadecane ratios (9:1, 1:1, and 1:9) at seven different HLB values each. The droplet size and polydispersity index (PDI) of the resulting emulsions were measured by DLS and are displayed in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Droplet diameter and PDI of emulsions prepared in the ultrasound-assisted microfluidic device at seven different HLB values over the accessible range using Span 80 and Tween 80 (4.3 to 15). Three different water:hexadecane ratios were prepared: Left: water:hexadecane 9:1; Middle: water:hexadecane 1:1 and right: water:hexadecane 1:9. Colors represent different types of emulsions. Blue: O/W; yellow: W/O; white: bicontinuous and green: instable (immediate phase separation). Each point represents the average of three independent experiments and the error bars are the standard deviation. All the formulations contained 2% w/w of surfactants. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

At every tested ratio of water:oil, the mini-emulsions have a minimum diameter at a specific HLB value. For example, with a 9:1 water:hexadecane ratio the minimum diameter (200 nm) corresponds to an HLB value of 9.0. In this case, the lowest value of the polydispersity index (PDI) also corresponds to the same HLB value. At HLB = 4.3 and 5, unstable dispersions are formed and immediately phase separation is observed. These two HLB values correspond to surfactant content of pure or almost pure Span 80, a surfactant normally used to prepare W/O emulsions. But the phases proportions used in this case, favor an oil-in-water emulsion. When a ratio of 1:1 water:oil is employed, highly viscous emulsions are observed at the channel exit for all the HLB values tested. At HLB = 4.3 and 5 w/o emulsions were formed, while at HLB = 7, a bicontinuous system (w/o and o/w) was identified by the dyeing method [56]. From HLB = 9 to 15.0, oil in water emulsions were formed. The minimum droplet diameter was measured again at HLB = 9 and almost all PDI values for these emulsions were bigger than those for 9:1 W:O ratio. For 1:9 water:hexadecane ratio, HLB values from 4.3 to 11 favored water in oil emulsions, finding a minimum droplet size at HLB = 4.3. At the high HLB values of 13 and 15, immediately phase separation was observed. In these last two cases a high proportion of Tween 80 was used, which favors oil-in-water emulsions that is contrary to the W:O proportions used in these points. The minimum observed PDI correspond to HLB = 9.0.

The maximum PDIs found were in the 1:1 W:O formulations, which are the emulsions with the largest droplets. Also the PDIs of the 9:1 W:O emulsions obtained at varying the HLB resemble the graph of droplet diameter as a function of HLB, establishing a direct correlation between PDI and droplet size for these systems. This has been observed for other emulsions [55], [57]. However, for the mixtures with 1:9 W:O ratio there is no correlation between PDI and droplet size.

3.6. Polymeric particle synthesis starting from a mini-emulsion

The device versatility was used to prepare an O/W mini-emulsion serving as a template for the synthesis of solid acrylate polymeric particles. Fig. 8 shows SEM micrographs of the resulting particles for different degasification times of the aqueous phase. Without degassing (Fig. 8a), a highly polydisperse sample is produced in which 85% of particles have diameters between 0.3 and 1.0 µm, and the rest spread out up to 4.9 µm, making this sample clearly unattractive for further applications. To quantify the spread of these heterogeneous particles we calculated their volume-weighted size distribution (Fig. 8d) which is more sensitive to the presence of large particles than the number–weighted distribution [58]. The obtained mean particle diameter is 2.86 µm with a standard deviation of ± 1.37 µm, resulting in a PDI of 48%. Since an increase in the sonication power failed to eliminate these large droplets, we decided to give a degassing treatment to the aqueous phase for 5 and 30 min before its introduction into the microfluidic device. This reduced the overall cavitation process in the aqueous phase, but maintained the cavitation in the organic phase, which, in contrast to the hexadecane employed before, presented cavitation when sonicated inside the microfluidic device (Video 4). The results are shown in Fig. 8b and 8c. Compared to the particles obtained without water degassing, these samples followed a normal size distribution with an average diameter and standard deviation of 1290 ± 343 nm and 1228 ± 398 nm for the 5- and 30-min treatment, respectively (Fig. 8e and 8f). Compared to the particles obtained without water degassing, the standard deviation and the PDI of these degassed samples were considerably reduced to 27% for 5 min and 32% for 30 min of degassing.

Fig. 8.

SEM micrographs of polymeric particles for different degasification times of the aqueous phase (a) 0 min, b) 5 min and c) 30 min) and volume weighted particle size distribution for the same polymeric particles (d) 0 min, e) 5 min and f) 30 min).

A possible explanation of these results is as follows. Since the particle size significantly depends on the cavitation process, more homogeneous cavitation results in a more stable process of oil droplet rupture. With a large amount of the dissolved gas in the continuous (aqueous) phase, more chaotic cavitation is expected resulting in the inhomogeneous droplet rupture and broader particle size distribution. Another reason may be the stability of droplets formed under such a vigorous cavitation: while some droplets are ruptured with formation of smaller ones, the others may coalesce due to the excessive mechanical emulsion perturbation. This does not happen when the cavitation is more homogeneous because there is less dissolved gas in the medium [44], [46], [47], [48].

4. Discussion

In this section we would like to mention some of the main aspects that need to be addresed in future work to imporve this device: 1) Microreactor dimensions. The height (175 µm) and width (290 µm) of the serpentine microreactor were chosen to be considered a microfluidic channel (i.e. < 1000 µm) and they are within the range of reported microchannels in which cavitation has been observed (20–1000 µm height, 100–1000 µm width) [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. For the channel length (7.0 cm), an intermediate value was chosen within reported values (1.2–28 cm). In a subsequent work it would be desirable to study how the dimensions of the microchannel correlate with the size and polydispersity of the emulsion droplets. A similar experiment has been done to determine the mixing efficiency of two liquids in a microchannel with ultrasound, finding better results when the channel depth and width increased form 250 to 1000 µm [30]. This coincides with studies in which higher power densities were required to initiate cavitation in a microchannel with a 200 × 200 µm cross-section compared to a 10 × 20 × 20 mm small reactor [21]. The results were explained in terms of the confinement effect, in which the small dimensions of the microchannels restrict the oscillation of the cavitation bubbles [21], [59]. However, it should also be considered that as the channel size increases, the volume fraction that creates effective cavitation diminishes [21], [60]. In the case of mini-emulsions, this could mean that as the dimensions of the channel increase, a larger emulsion volume is obtained but with larger and more polydisperse droplets, both of which are undesirable. Finally, the channel length could be also optimized. In this case, it is likely that the power threshold needed to start cavitation increses with length because the applied pressure drop to move the fluids is higher in longer channels. However, a too short channel might be insufficient to mix and break up the dispersed phase droplets.

2) Temperature control. During sonoemulsification a large amount of energy is dissipated as heat, which can increase the temperature of the sample [44]. Although microfluidic devices are known to dissipate the heat excess very well, we used a fan to help removing some of the heat produced. Despite this, an increase of 12–15° C above room temperature was observed. This difference usually does not affect the properties of emulsions prepared with long chain hydrocarbon such as hexadecane used in this work [44], and could even promote the emulsification process as the interfacial tension decreases on heating [40], [59]. Nevertheless, to work with heat sensitive samples it would be crucial to incorporate an efficient cooling system (e.g. [59]).

3) Radical formation. One of the main critics to generate mini- and nanoemulsions with ultrasound for the food, cosmetic and drug delivery industry is the formation of free radicals during the collapse of the cavitation bubbles [24], [29]. These radicals together with increased temperature are likely to be responsible for the degradation of oils, proteins and other labile molecules [61], [62]. However, there has been an enormous effort to find ultrasonication conditions in which the deterioration of such molecules are kept at minimum or null [63], [64] and these conditions should be incorporated into the microfluidic device.

4) Scale-up of the microreactor. Although the platform presented in this work was conceived for carring out screening experiments at small scale with low reagent consumption, it would be desirable to scale up the formulation once the best conditions are found. PDMS would not be the most suitable material for this purpose, as it will deform with higher flow rates and could be swollen by some organic solvents [42]. Suitable materials to construct, for example, several identical units in parallel [24], [65] are silicon–glass [65] or engraved metal [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], in which impedance differences are minimized [66] and which are capable of withstanding higher pressures employed for emulsion production on a L/h scale. Another alternative would be the use of sonoreactor bags [40].

5. Conclusions

In this work we developed and characterized a microfluidic platform that permits to prepare mini-emulsions in continuous flow with the aid of an ultrasound actuator directly attached to the device. We observed cavitation in the microchannels in the aqueous phase and found that it is the main driving force for mixing and droplet breakage in the O/W or W/O mini-emulsions with hexadecane. It was confirmed that other organic phases such as 1–6 diacrylate hexanodiol, presented a certain degree of cavitation that can drive the emulsification process. The four-inlet channel microdevice permits to introduce different ratios of aqueous and oil phases together with distinct amounts of two different surfactants in a continuous flow. This opens the possibility to explore a broad range of surfactant formulations with different HLB values and correlate this parameter with mini-emulsion droplet size and polydispersity index, employing a minimum amount of reagents (<500 µL). Although, we maintained 2% w/w as the total surfactant concentration, the device can be easily used for other amounts of surfactants in a fixed composition of oil and water, or even more lateral channels can be included for other additives. Fabrication of solid particles form a mini-emulsion template also demonstrates the device versatility. Degasification of the aqueous phase has improved the PDI of the resulting particles reducing it down to 24%.

In comparison with other reported methodologies [38], [39], attachment of the piezoelectric to the microfluidic device increases the power delivered to the sample, so it is not necessary to perform several emulsification cycles or any homogenization pretreatment. Another advantage of the system presented in this work is the posibility to directly observe under the microscope the events at the beginning of the emulsification process due to acoustic cavitation, which provides valuable information on its mechanism.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Erick Nieves: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Giselle Vite: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Anna Kozina: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Luis F. Olguin: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

E.N. acknowledge CONACyT Mexico for a PhD fellowship 297311 and Posgrado en Ciencias Químicas (UNAM) for its support. We thank Alma Jessica Díaz Salazar for technical assistance, Dr. Josefa Bernal for access to the DLS equipment and Dr. Samuel Tehuacanero-Cuapa for SEM images acquisition. The authors acknowledge DGAPA-UNAM for financial support through PAPIIT grant IT203318 and IN100619 and Facultad de Química UNAM for complementary support through PAIP grant 5000-9023.

References

- 1.Slomkowski S., Alemán J.V., Gilbert R.G., Hess M., Horie K., Jones R.G., Kubisa P., Meisel I., Mormann W., Penczek S., Stepto R.F.T. Terminology of polymers and polymerization processes in dispersed systems (IUPAC recommendations 2011) Pure Appl. Chem. 2011;83(2011):2229–2259. doi: 10.1351/PAC-REC-10-06-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jafari S., McClements D.J., editors. Nanoemulsions. Applications and Characterization, Academic Press; Formulation: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao F., Zhang Z., Bu H., Huang Y., Gao Z., Shen J., Zhao C., Li Y. Nanoemulsion improves the oral absorption of candesartan cilexetil in rats: Performance and mechanism. J. Control. Release. 2011;149:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh Y., Meher J.G., Raval K., Khan F.A., Chaurasia M., Jain N.K., Chourasia M.K. Nanoemulsion: Concepts, development and applications in drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2017;252:28–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gianella A., Jarzyna P.A., Mani V., Ramachandran S., Calcagno C., Tang J., Kann B., Dijk W.J.R., Thijssen V.L., Griffioen A.W., Storm G., Fayad Z.A., Mulder W.J.M. Multifunctional Nanoemulsion Platform for Imaging Guided Therapy Evaluated in Experimental Cancer. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4422–4433. doi: 10.1021/nn103336a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yukuyama M.N., Ghisleni D.D.M., Pinto T.J.A., Bou-Chacra N.A. Nanoemulsion: Process selection and application in cosmetics - A review. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2016;38:13–24. doi: 10.1111/ics.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvia-Trujillo L., Soliva-Fortuny R., Rojas-Graü M.A., McClements D.J., Martín-Belloso O. Edible Nanoemulsions as Carriers of Active Ingredients: A Review. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017;8:439–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030216-025908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanmugam A., Ashokkumar M. Characterization of Ultrasonically Prepared Flaxseed oil Enriched Beverage/Carrot Juice Emulsions and Process-Induced Changes to the Functional Properties of Carrot Juice. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015;8:1258–1266. doi: 10.1007/s11947-015-1492-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han Z.H., Yang B., Qi Y., Cumings J. Synthesis of low-melting-point metallic nanoparticles with an ultrasonic nanoemulsion method. Ultrasonics. 2011;51:485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera-Rangel R.D., González-Muñoz M.P., Avila-Rodriguez M., Razo-Lazcano T.A., Solans C. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles in oil-in-water microemulsion and nano-emulsion using geranium leaf aqueous extract as a reducing agent. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018;536:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.07.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harun S.N., Nordin S.A., Gani S.S.A., Shamsuddin A.F., Basri M., H. Bin Basri, Development of nanoemulsion for efficient brain parenteral delivery of cefuroxime: Designs, characterizations, and pharmacokinetics. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2018;13:2571–2584. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S151788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delmas T., Piraux H., Couffin A.C., Texier I., Vinet F., Poulin P., Cates M.E., Bibette J. How to prepare and stabilize very small nanoemulsions. Langmuir. 2011;27:1683–1692. doi: 10.1021/la104221q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helgeson M.E. Colloidal behavior of nanoemulsions: Interactions, structure, and rheology. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;25:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2016.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piradashvili K., Alexandrino E.M., Wurm F.R., Landfester K. Reactions and polymerizations at the liquid-liquid interface. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:2141–2169. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Entezari M.H., Keshavarzi A. Phase-transfer catalysis and ultrasonic waves II: Saponification of vegetable oil. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001;8:213–216. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(01)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A. Gupta, A. Zayed, M. Badruddoza, P.S. Doyle, P.S.D. Ankur Gupta, Abu Zayed Md Badruddoza, A General Route for Nanoemulsion Synthesis using Low Energy Methods at Constant Temperature, Langmuirfile///Users/Luisolguin/Documents/Manuscripts/Nanoemulsion-Chip/Second Atempt/Articulos Citados/Ultrasound Chips/Dong Zhengya 2015 Lab Chip-High-Power Ultrason. Microreactor Its Appl. Gas–Liquid Mass Transf. 3 (2017) 7118–7123. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01104.

- 17.Fryd M.M., Mason T.G. Advanced Nanoemulsions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2012;63:493–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar H., Kumar V. Ultrasonication assisted formation and stability of water-in-oil nanoemulsions: Optimization and ternary diagram analysis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;49:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leong T.S.H., Wooster T.J., Kentish S.E., Ashokkumar M. Minimising oil droplet size using ultrasonic emulsification. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009;16:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Modarres-Gheisari S.M.M., Gavagsaz-Ghoachani R., Malaki M., Safarpour P., Zandi M. Ultrasonic nano-emulsification – A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;52:88–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iida Y., Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Sivakumar M., Endo Y. Ultrasonic cavitation in microspace. Chem. Commun. 2004:2280–2281. doi: 10.1039/b410015h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tandiono S.-W., Ohl D.S.-W., Ow E., Klaseboer V.V.T., Wong A., Camattari C.-D. Ohl, Creation of cavitation activity in a microfluidic device through acoustically driven capillary waves. Lab Chip. 2010;10:1848–1855. doi: 10.1039/c002363a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.S.-W. Ohl, C.-D. Ohl, Acoustic Cavitation in a Microchannel, in: Handb. Ultrason. Sonochemistry, Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2016: pp. 99–135. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-278-4_6.

- 24.Dong Z., Delacour C., Carogher K.M., Udepurkar A.P., Kuhn S. Continuous ultrasonic reactors: Design, mechanism and application. Materials (Basel). 2020;13 doi: 10.3390/ma13020344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandez Rivas D., Kuhn S. Synergy of Microfluidics and Ultrasound: Process Intensification Challenges and Opportunities. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016;374:225–254. doi: 10.1007/s41061-016-0070-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng Q., Lomonosov A.M., Furlong E.E.M.M., Merten C.A. Fragmentation of DNA in a sub-microliter microfluidic sonication device. Lab Chip. 2012;12:4677. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40595d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Z., Lu C. A Microfluidic Device with Integrated Sonication and Immunoprecipitation for Sensitive Epigenetic Assays. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:1965–1972. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tandiono T., Siak-Wei Ow D., Driessen L., Sze-Hui Chin C., Klaseboer E., Boon-Hwa Choo A., Ohl S.W., Ohl C.D. Sonolysis of Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris in microfluidics. Lab Chip. 2012;12:780–786. doi: 10.1039/c2lc20861j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tandiono S.W., Ohl D.S.W., Ow E., Klaseboer V.V., Wong R., Dumke C.D. Ohl, Sonochemistry and sonoluminescence in microfluidics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:5996–5998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019623108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Z., Zhao S., Zhang Y., Yao C., Yuan Q., Chen G. Mixing and residence time distribution in ultrasonic microreactors. AIChE J. 2017 doi: 10.1002/aic.15493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ozcelik A., Ahmed D., Xie Y., Nama N., Qu Z., Nawaz A.A., Huang T.J. An acoustofluidic micromixer via bubble inception and cavitation from microchannel sidewalls. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:5083–5088. doi: 10.1021/ac5007798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong Z., Yao C., Zhang Y., Chen G., Yuan Q., Xu J. Hydrodynamics and mass transfer of oscillating gas-liquid flow in ultrasonic microreactors. AIChE J. 2016;62:1294–1307. doi: 10.1002/aic.15091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao S., Dong Z., Yao C., Wen Z., Chen G., Yuan Q. Liquid-liquid two-phase flow in ultrasonic microreactors: Cavitation, emulsification, and mass transfer enhancement. AIChE J. 2018;64:1412–1423. doi: 10.1002/aic.16010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao S., Yao C., Dong Z., Liu Y., Chen G., Yuan Q. Intensification of liquid-liquid two-phase mass transfer by oscillating bubbles in ultrasonic microreactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018;186:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2018.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohl S.-W., Tandiono T., Klaseboer E., Ow D., Choo A., Li F., Ohl C.-D. Surfactant-free emulsification in microfluidics using strongly oscillating bubbles. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014 doi: 10.1121/1.4900279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanda T. Production of nanoemulsion using a microchannel device oscillated by piezoelectric transducer, 16th Int. Conf. Nanotechnol. - IEEE NANO. 2016;2016:718–719. doi: 10.1109/NANO.2016.7751382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanda T., Kiyama Y., Suzumori K. A nano emulsion generator using a microchannel and a bolt blamped type transducer. IEEE Int. Ultrason. Symp. IUS. 2013:194–196. doi: 10.1109/ULTSYM.2013.0050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freitas S., Hielscher G., Merkle H.P., Gander B. Continuous contact- and contamination-free ultrasonic emulsification - A useful tool for pharmaceutical development and production. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2006;13:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manickam S., Sivakumar K., Pang C.H. Investigations on the generation of oil-in-water (O/W) nanoemulsions through the combination of ultrasound and microchannel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;69 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Zwieten R., Verhaagen B., Schroën K., Fernández Rivas D. Emulsification in novel ultrasonic cavitation intensifying bag reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;36:446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.A. Ochoa, F. Trejo, L.F. Olguín, Droplet-Based Microfluidics Methods for Detecting Enzyme Inhibitors, in: N.E. Labrou (Ed.), Target. Enzym. Pharm. Dev. Methods Protoc., Humana, New York, NY, 2020: pp. 209–233. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0163-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Dangla R., Gallaire F., Baroud C.N. Microchannel deformations due to solvent-induced PDMS swelling. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2972–2978. doi: 10.1039/c003504a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komaiko J., McClements D.J. Optimization of isothermal low-energy nanoemulsion formation: Hydrocarbon oil, non-ionic surfactant, and water systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;425:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nazarzadeh E., Sajjadi S. Thermal effects in nanoemulsification by ultrasound. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013;52:9683–9689. doi: 10.1021/ie4003014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasband W.S. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 2018. ImageJ. https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canselier J.P., Delmas H., Wilhelm A.M., Abismaïl B. Ultrasound emulsification - An overview. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2002;23:333–349. doi: 10.1080/01932690208984209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calligaris S., Plazzotta S., Bot F., Grasselli S., Malchiodi A., Anese M. Nanoemulsion preparation by combining high pressure homogenization and high power ultrasound at low energy densities. Food Res. Int. 2016;83:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jadhav A.J., Holkar C.R., Karekar S.E., Pinjari D.V., Pandit A.B. Ultrasound assisted manufacturing of paraffin wax nanoemulsions: Process optimization. Elsevier B.V. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sivakumar M., Tang S.Y., Tan K.W. Cavitation technology - A greener processing technique for the generation of pharmaceutical nanoemulsions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:2069–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Behrend O., Schubert H. Influence of hydrostatic pressure and gas content on continuous ultrasound emulsification. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001;8:271–276. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(01)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leighton T.G. An introduction to acoustic cavitation. In: Duck F.A., Baker A., Starrit H.C., editors. Ultrasound Med. Institute of Physics Publishing; London: 1998. pp. 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bolaños-Jiménez R., Rossi M., Rivas D.F., Kähler C.J., Marin A. Streaming flow by oscillating bubbles: Quantitative diagnostics via particle tracking velocimetry. J. Fluid Mech. 2017;820:529–548. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2017.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidts T., Schlupp P., Gross A., Dobler D., Runkel F. Required HLB Determination of Some Pharmaceutical Oils in Submicron Emulsions. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2012;33:816–820. doi: 10.1080/01932691.2011.584800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qadir A., Faiyazuddin M.D., Talib Hussain M.D., Alshammari T.M., Shakeel F. Critical steps and energetics involved in a successful development of a stable nanoemulsion. J. Mol. Liq. 214 2016:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.11.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lefebvre G., Riou J., Bastiat G., Roger E., Frombach K., Gimel J.C., Saulnier P., Calvignac B. Spontaneous nano-emulsification: Process optimization and modeling for the prediction of the nanoemulsion’s size and polydispersity. Int. J. Pharm. 2017;534:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunieda H., Aramaki K., Izawa T., Kabir M.H., Sakamoto K., Watanabe K. Dye Method to Identify the Types of Cubic Phases. J. Oleo Sci. 2003;52:429–432. doi: 10.5650/jos.52.429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ricaurte L., Hernández-Carrión M., Moyano-Molano M., Clavijo-Romero A., Quintanilla-Carvajal M.X. Physical, thermal and thermodynamical study of high oleic palm oil nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2018;256:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malvern-Ltd., A basic guide to particle characterization 2015.

- 59.Zhao S., Yao C., Zhang Q., Chen G., Yuan Q. Acoustic cavitation and ultrasound-assisted nitration process in ultrasonic microreactors: The effects of channel dimension, solvent properties and temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;374:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.05.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tuziuti T. Influence of degree of gas saturation on sonochemiluminescence intensity resulting from microfluidic reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2013;117:10598–10603. doi: 10.1021/jp407068n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chemat F., Grondin I., Sing A.S.C., Smadja J. Deterioration of edible oils during food processing by ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2004;11:13–15. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(03)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nourbehesht N., Shekarchizadeh H., Soltanizadeh N. Investigation of stability, consistency, and oil oxidation of emulsion filled gel prepared by inulin and rice bran oil using ultrasonic radiation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carrillo-Lopez L.M., Garcia-Galicia I.A., Tirado-Gallegos J.M., Sanchez-Vega R., Huerta-Jimenez M., Ashokkumar M., Alarcon-Rojo A.D. Recent advances in the application of ultrasound in dairy products: Effect on functional, physical, chemical, microbiological and sensory properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silva M., Zisu B., Chandrapala J. Stability of oil–water primary emulsions stabilised with varying levels of casein and whey proteins affected by high-intensity ultrasound. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;56:897–908. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yadavali S., Jeong H.H., Lee D., Issadore D. Silicon and glass very large scale microfluidic droplet integration for terascale generation of polymer microparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong Z., Yao C., Zhang X., Xu J., Chen G., Zhao Y., Yuan Q. A high-power ultrasonic microreactor and its application in gas-liquid mass transfer intensification. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1145–1152. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01431f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.