Abstract

Next generation sequencing (NGS) technology has revealed the heterogeneity of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) from a mutation perspective. Accordingly, the conventional cell of origin-based classification of DLBCL has changed to a mutation-based classification. Mutation analysis delineates that B-cell receptor pathway activation, EZH2 mutation, and NOTCH mutations are distinctive drivers of DLBCL. Moreover, the combination of RNA expression data and DNA mutation results suggests similarity between DLBCL subtypes and other non-Hodgkin lymphomas. NGS-based dissection of DLBCL would be the cornerstone for precision treatment in this heterogeneous disease in the near future.

Keywords: DLBCL, NGS, RNA, Clustering, Classification, Genomics

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a heterogeneous disease. Attempts to classify DLBCL dates back to the early 2000s, and the cell-of-origin (COO) approach was attempted based on RNA expression data [1]. This is closely related to the pathogenesis of DLBCL, because it is an attempt to distinguish the time point of lymphoma development based on the germinal center reaction.

Since 2010, with the development of the next generation sequencing (NGS) technique, information on many mutations has accumulated at the DNA level, and studies on this mutation have also been published in the DLBCL field. Since the research on the level of DNA in cancer is closely related to the development of targeted therapeutics, these studies are expected to be used as a meaningful starting point for the development of novel therapeutics for DLBCL. In this paper, we review recent studies at the DNA level of a typical DLBCL and discuss future perspectives.

Recent anecdotal studies

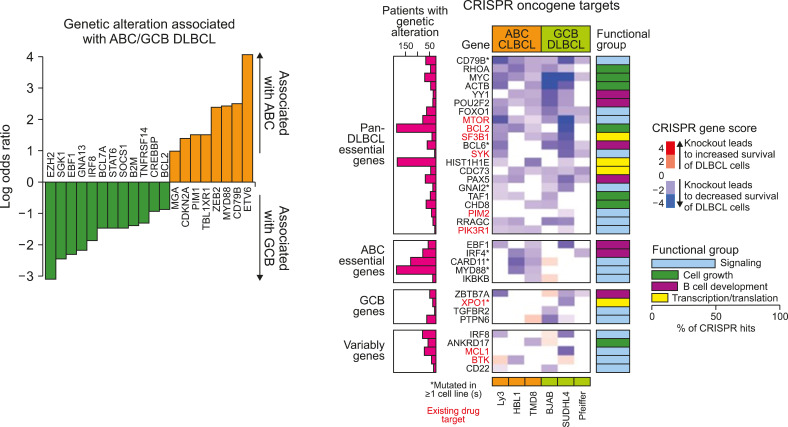

(1) Reddy et al.’s research was published in the Cell magazine in 2017 [2]. The results of whole-exome sequencing-based studies of 1,001 patients were combined with cell line experiments using the CRISPR technique. Important mutations in the activated B cell-like (ABC) and germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL were also listed. Based on these results, MYD88 was selected as an essential mutation in the ABC, whereas XPO1 was selected as an essential mutation in GCB DLBCL. However, this study did not explain DNA mutation-based disease clustering, but only explained the existing RNA-based or translocation-based classification with DNA mutations. Rather, they focused on the prognostic significance of the mutations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Essential gene mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Reddy et al. 2017).

(2) Chapuy et al.’s study was published in the journal Nature Medicine in 2018 [3], and this study had a great significance in the sense that DNA-based classification of DLBCL was successfully performed. Whole exome sequencing was performed on 304 patients, and DLBCL was classified into C1-C5 subtypes. It should be noted that this classification was characterized by not only DNA mutation information but also relatively various information, such as fusion and chromosomal abnormality.

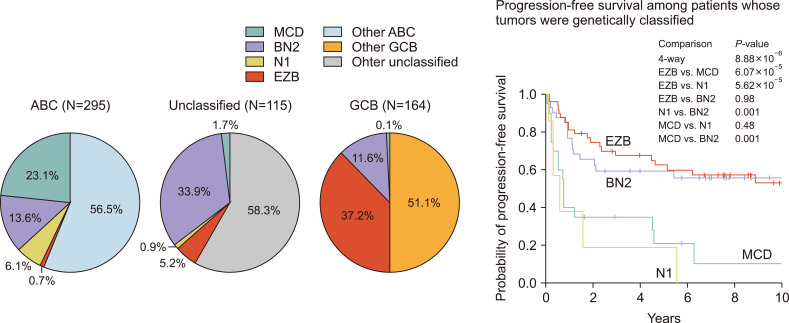

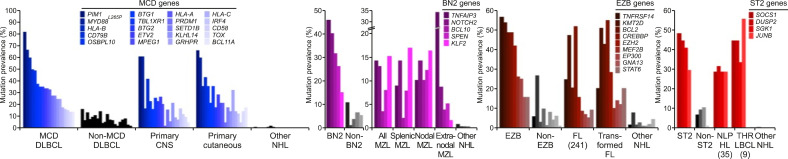

(3) Schmitz et al.’s study was introduced in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 2018 [4], and this study classified DLBCL into four categories based on DNA mutations and major fusions. Whole exome sequencing was performed with a sample of 574 patients, and they were classified into the multi-centric Castleman’s disease (MCD), BN2, N1, and EZB groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mutation based on the new classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Schmitz et al. 2018).

There are many common denominators in the studies caried out by Chapuy and Schmitz; for example, MCD is almost the same as C5, and EZB is almost the same as C3. However, there are some discrepancies, which are thought to originate from the different input data and the differences in the study population.

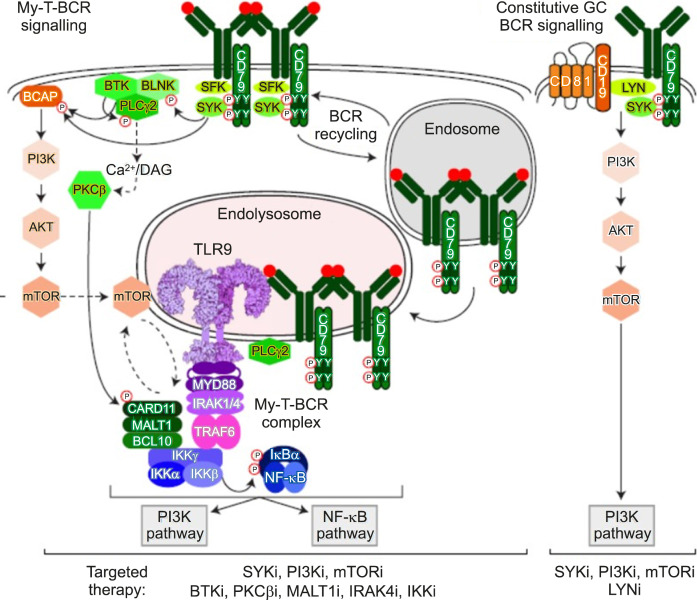

(4) Lastly, although not at the DNA level, I introduce an important study based on protein-protein interaction [5]. Phelan et al. [5] demonstrated that MYD88, TLR9, and B Cell Receptor (BCR) combine to form a supercomplex using CRISPR screening and protein-ligation assay (PLA), which is an important biomarker for predicting the response to Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. However, because PLA is not a technique widely applicable in clinical practice, the technical barrier to measure the appropriate protein-protein interaction must be overcome if this supercomplex is to be utilized in clinical practice (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

My-T-BCR supercomplex in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Phelan et al. 2018).

New trends

Statistical clustering of DLBCL: Rather than making novel discoveries for pathogenesis based on previous studies, attempts to elaborate the classification of DLBCL are ongoing. Research using big-data-based clustering techniques is in full swing. Such a clustering approach has already been introduced for acute myeloid leukemia [6], where cancer genomic research has been initiated. Similar attempts have been made for DLBCL. The following are some recent studies:

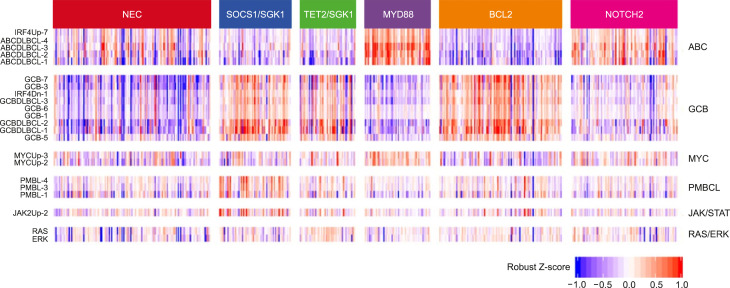

- Lacy et al. [7] performed 293-gene targeted panel sequencing in a cohort of 928 patients. Although MYD88, BCL2, and NOTCH were the same as in previous studies, it was suggested that a new category of TET2/SGK1 and SOCS1/SGK1 mutation-driven DLBCL may exist. The characteristic of this study is that gene expression profiling was performed simultaneously in 519 patients, and mutations were analyzed once based on expression data (Fig. 4).

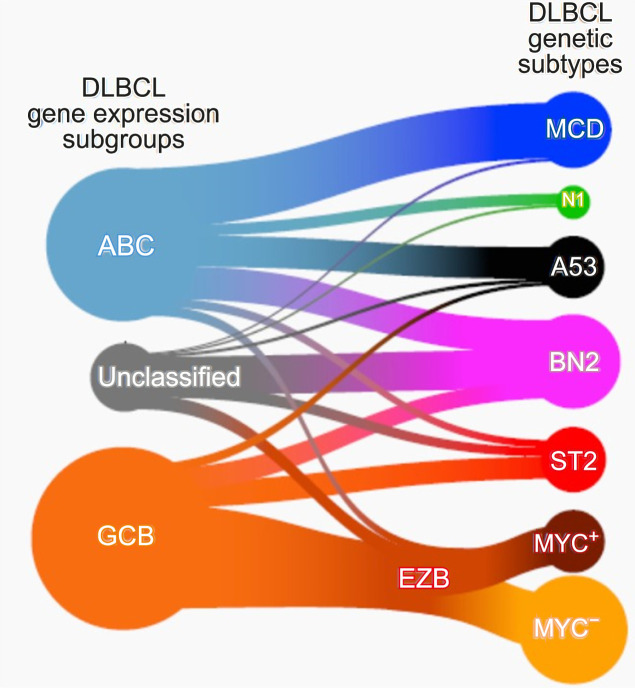

- Wright et al. [8] again attempted a reclassification based on mutation and translocation in various cohorts based on the research conducted by Schmitz, and conducted the most complete research so far. They succeeded in adding a new category called ST2 (SGK1/TET2 mutation-driven). They found that the MYC rearrangement status was important only in the EZB subtype (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and expression data (Lacy et al. 2020).

Fig. 5.

Classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on genetics (Wright et al. 2020).

Returning to the cell of origin with genomic profiling: In the other direction, studies are ongoing to trace the cell of origin based on these mutation approaches. On the solid cancer side, mutation studies on metastasis of unknown primary/origin have been conducted to identify the cell of origin based on molecular characterization [9]. This molecular testing-based COO finding would be useful in lymphoma areas where biopsy is not always feasible. In particular, it will be a tool that can properly utilize effective treatments, such as bendamustine and ibrutinib for specific types of lymphomas for DLBCL.

According to Wright et al. [8], MCD DLBCL was very similar to primary central nervous system lymphoma, and the BN2 subtype was very similar to the marginal zone B cell lymphoma. On the contrary, it was confirmed that the EZB type was similar to the follicular lymphoma. Interestingly, the newly discovered ST2 type was similar to the T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma or nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Therefore, it may be possible to appropriately treat one of the various DLBCL salvage regimens according to this molecular classification (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Genomics and lymphoma subtypes (Wright et al. 2020).

New drug discovery with genomics: Finally, an attempt is being made to develop a new drug based on molecular testing. The discovery of the My-T-BCR supercomplex and the development of new drugs based on the CBM complex are expected to open the era of truly customized treatment for DLBCL.

Korean perspective

In Korea, the NGS panel for DLBCL is also reimbursed, but DLBCL has a distinct mutation profile from other cancers; thus, a custom design is required. Considering the domestic lab-developed test type service behavior, it is thought that the consensus of domestic pathologists and laboratory medicine physicians is necessary for the nationwide expansion of appropriate lymphoma panel services. Only when appropriate panel services are performed in domestic hospitals can domestic real-world data-based DLBCL research be properly conducted in the future.

CONCLUSION

Recently revealed DNA based new genomic classification would be more frequently utilized for precision treatment of DLBCL.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barton S, Hawkes EA, Wotherspoon A, Cunningham D. Are we ready to stratify treatment for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using molecular hallmarks? Oncologist. 2012;17:1562–73. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy A, Zhang J, Davis NS, et al. Genetic and functional drivers of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cell. 2017;171:481–94.:e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapuy B, Stewart C, Dunford AJ, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat Med. 2018;24:679–90. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitz R, Wright GW, Huang DW, et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1396–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelan JD, Young RM, Webster DE, et al. A multiprotein supercomplex controlling oncogenic signalling in lymphoma. Nature. 2018;560:387–91. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacy SE, Barrans SL, Beer PA, et al. Targeted sequencing in DLBCL, molecular subtypes, and outcomes: a haematological malignancy research network report. Blood. 2020;135:1759–71. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright GW, Huang DW, Phelan JD, et al. A probabilistic classification tool for genetic subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma with therapeutic implications. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:551–68.:e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varghese AM, Arora A, Capanu M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with cancer of unknown primary in the modern era. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:3015–21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]