This cohort study compares patterns of childbirth among physicians vs nonphysicians.

Key Points

Question

Are women physicians more likely to delay childbearing or less likely to have children compared with nonphysicians?

Findings

In this population-based retrospective cohort study of 5238 reproductive-aged physicians matched 1:5 to nonphysician counterparts, physicians significantly postponed the initiation of childbearing. Despite this delay, physicians ultimately achieved a similar probability of childbirth as nonphysicians, owing to higher rates of pregnancy at advanced maternal ages; this phenomenon was most pronounced for specialists.

Meaning

Physicians appear to delay childbearing and may be at increased risk of age-related adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Women physicians may delay childbearing and experience childlessness more often than nonphysicians, but existing knowledge is based largely on self-reported survey data.

Objective

To compare patterns of childbirth between physicians and nonphysicians.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population-based retrospective cohort study of reproductive-aged women (15-50 years) in Ontario, Canada, accrued from January 1, 1995, to November 28, 2018, and observed to March 31, 2019. Outcomes of 5238 licensed physicians of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario were compared with those of 26 640 nonphysicians (sampled in a 1:5 ratio). Physicians and nonphysicians were observed from age 15 years onward.

Exposures

Physicians vs nonphysicians.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was childbirth at gestational age of 20 weeks or greater. Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the association between physician status and childbirth, overall and across career stage (postgraduate training vs independent practice) and specialty (family physicians vs specialists).

Results

All physicians (n = 5238) and nonphysicians (n = 26 640) were aged 15 years at baseline, and 28 486 (89.1%) were Canadian-born. Median follow-up was 15.2 (interquartile range, 12.2-18.2) years after age 15 years. Physicians were less likely to experience childbirth at younger ages (hazard ratio [HR] for childbirth at 15-28 years, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.14-0.18; P < .001) and initiated childbearing significantly later than nonphysicians; the cumulative incidence of childbirth was 5% at 28.6 years in physicians and 19.4 years in nonphysicians. However, physicians were more likely to experience childbirth at older ages (HR for 29-36 years, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.28-1.43; P < .001; HR for ≥37 years, 2.62; 95% CI, 2.00-3.43; P < .001), and ultimately achieved a similar cumulative probability of childbirth as nonphysicians overall. Median age at first childbirth was 32 years in physicians and 27 years in nonphysicians (P < .001). After stratifying by specialty, the cumulative incidence of childbirth was higher in family physicians than in both surgical and nonsurgical specialists at all observed ages.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest that women physicians appear to delay childbearing compared with nonphysicians, and this phenomenon is most pronounced among specialists. Physicians ultimately appear to catch up to nonphysicians by initiating reproduction at older ages and may be at increased risk of resulting adverse reproductive outcomes. System-level interventions should be considered to support women physicians who wish to have children at all career stages.

Introduction

Despite increasing gender parity in the physician workforce, a career in medicine is still frequently viewed as a barrier to motherhood.1,2,3,4 Women physicians who wish to have children face demanding work hours, limited options for parental leave and child support, and potential stigmatization by peers and superiors.3,4,5 Women physicians may therefore remain childless or delay childbearing relative to the general population; 50% to 60% report postponing pregnancy to independent practice,6,7 and 25% who attempt conception report infertility.8,9 These factors may place women physicians at risk of age-related adverse reproductive outcomes.10,11

Existing studies examining pregnancy and childbirth in women physicians are almost exclusively self-reported surveys prone to sampling and information bias. To our knowledge, only 1 observational study has described reproductive patterns in women physicians12; the authors found that maternal age at delivery was higher for physicians relative to nonphysicians, but the study did not explore time to childbirth or whether parity, specialty, or training status influenced the trends observed.

Large epidemiologic studies using validated data sources are needed to accurately characterize patterns of childbirth among women physicians. These data would contextualize pregnancy outcomes in this population and directly inform reproductive planning and care. We therefore examined patterns of childbirth in physicians compared to nonphysicians using population-based health administrative data.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We performed a population-based retrospective cohort study of reproductive-aged women in Ontario, Canada, where 14.6 million citizens reside and 40% of Canadian childbirths occur.13 All Ontario residents are eligible for universal health insurance coverage for hospital and physician services. The study protocol was published14 and approved by the Research Ethics Board at St Michael’s Hospital (Toronto, Ontario, No. 18-248) (Supplement 1).

To practice medicine in Ontario, physicians must obtain a medical license from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO), which is the sole regulatory body that grants medical licenses in Ontario. Physicians are first granted a postgraduate education license at completion of medical school and initiation of residency training, and subsequently granted an independent practice license after examination and certification by either the College of Family Physicians of Canada or the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

To complete this study, we obtained a data set of Ontario physicians licensed by the CPSO and linked this data set to population-based databases held at ICES, a nonprofit research institute and prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which authorizes ICES to collect personal health information on all Ontario residents, without consent, for the purpose of health system evaluation and improvement (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The unique linkage of CPSO data to ICES data enabled identification of physicians and nonphysicians, physician characteristics (eg, specialty, date of licensing to train or practice independently), covariates, and outcomes.14 Data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population and Exposure Assessment

Selection of Physicians

Women were classified as physicians if they had a record of being licensed to practice medicine with the CPSO, either as a postgraduate trainee or independent practitioner. We included all women physicians (aged 15-50 years) who (1) were first licensed between January 1, 1995, and November 26, 2018; (2) were Ontario residents on the date that they were granted their CPSO license; and (3) had been eligible for provincial health insurance since the age of 15 years. These strict criteria enabled selection of women in which all childbirths over the reproductive life span could be accurately detected in ICES databases.

Selection of Nonphysicians

Nonphysician women (aged 15-50 years) were drawn from the ICES Registered Persons Database and randomly assigned a simulated medical licensing date according to the distribution of all licensing dates in physicians. Nonphysicians were included if they (1) were alive on their simulated licensing date; (2) were Ontario residents on that date; and (3) had been eligible for provincial health insurance since the age of 15 years. This approach mirrored the selection of physicians, who by definition were alive on the date of licensing.

We aimed to determine whether patterns of childbirth differed for physicians and nonphysicians over the reproductive life span. To do so, we observed physicians and nonphysicians from the date of their 15th birthday. For each physician, we sampled 5 eligible nonphysicians born in the same year to ensure that groups were balanced on age and era of cohort entry. It should be recognized that a period of immortal time was introduced in this process; however, its extent was similar in physicians and nonphysicians, as neither could die prior to their actual or simulated licensing date, respectively, and it was unlikely to bias results because the cumulative probability of death after licensing was also very low (<0.2%).

Outcome Assessment

The primary outcome was time to childbirth, defined as the time in years from individuals’ 15th birthday to their first subsequent singleton or multiple live birth or stillbirth at gestational age of 20 weeks or greater. This outcome was selected as the best available reflection of an intention to continue pregnancy to term. Childbirths were identified from the ICES-derived MOMBABY database, which links the inpatient admission records of all mothers and newborns in Ontario (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Because 97% of Ontario births occur in hospitals, use of MOMBABY ensured accurate outcome ascertainment. Data on childbirths were available to March 31, 2019.13

Cohort Description and Covariates

Demographic characteristics were ascertained for physicians and nonphysicians at age 15 years and included residential income quintile, era of cohort entry (1995-2006, 2007-2018), immigration status (immigrant, Canadian-born),15 comorbidities (0, 1-5, 6-9, ≥10), and previous live births (0, 1, ≥2). Residential income quintile is an area-level measure of socioeconomic status derived from Canadian census data on the median reported income for the neighborhood where individuals live.16,17 Comorbidities were categorized into Aggregated Diagnosis Groups on the basis of clinical similarity, chronicity, disability, and likelihood of requiring specialty care, using the Johns Hopkins ACG System, version 10 (Johns Hopkins Healthcare Solutions) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).18

Physician characteristics were determined at the date of licensing and included career stage (postgraduate trainee, independent practitioner) and specialty (family medicine, other specialists, or specialty not yet determined). Career stage was treated as a time-varying covariate; because only independent practitioners can submit billing claims for health services, we used the first claim submitted to the Ontario Health Insurance Plan as an indicator of the transition from postgraduate trainee to independent practitioner (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).14 Specialty was assigned based on information in the CPSO data set or other ICES databases (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). If physicians had no documented specialty in any available data source and were recent medical graduates (≥2013), indicating ongoing postgraduate training,1 then their specialty of practice was categorized as not yet determined.14

Statistical Analysis

Timing of Childbirth

Baseline characteristics (at age 15 years) were compared between groups using standardized differences.19 Standardized differences reflect differences between group means and proportions relative to the pooled SD and are appropriate for comparison of frequency-matched or individually matched samples.19

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess whether physician status was associated with time to childbirth. Individuals were observed from age 15 years and censored at death, loss to follow-up (ie, loss of eligibility for provincial health insurance), or end of follow-up (ie, March 31, 2019, as per MOMBABY). We also plotted the cumulative probability of childbirth for physicians and nonphysicians using maternal age as the time scale, both overall and stratified by specialty (family physicians vs other specialists).

The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated with an interaction between physician status and time, and by plotting log[−log(survival)] vs log (time). Both methods demonstrated violation of the proportional hazards assumption (interaction P < .001; eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). We addressed this by fitting a piecewise Cox proportional hazards model at 3 time intervals: (1) age 15 to 28 years; (2) age 29 to 36 years; and (2) age 37 years and older. Overall and piecewise models are presented with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. Because hazards were nonproportional, the HRs presented reflect the average relative rate between physicians and nonphysicians over respective time periods.

We performed several sensitivity analyses to confirm that the findings were robust. To account for socioeconomic status as a potential confounder, we restricted the nonphysician comparator group to those in the highest income quintile only. To determine whether patterns of childbirth varied over time and over specific specialty type, we additionally stratified analyses for physicians born from 1976 to 1984 and 1985 to 1994, and for physicians in surgical and nonsurgical specialties.

Supplemental Analysis

To account for the fact that most physicians remained nulliparous until their licensing date, and to ensure that groups were as comparable as possible, we performed a supplemental analysis in which nulliparous physicians were matched to a separate group of nonphysicians who also remained nulliparous until their simulated licensing date. In this analysis: (1) each physician was individually matched to 5 eligible nonphysicians on age and year of licensing; (2) physicians and nonphysicians were observed from their actual or simulated date of licensing, respectively; and (3) physician status was modeled as 3-level time-varying exposure (nonphysician, postgraduate trainee, independent practitioner) to address the previously noted nonproportional hazards and enable an assessment of patterns of childbirth by career stage. A Cox proportional hazards model, with a robust variance estimator to account for correlation within individually matched sets, was used to assess whether physician status was associated with time to childbirth; we repeated these analyses with a stratified Cox proportional hazards model as an alternative approach to account for individual matching.20 Analyses were run overall and stratified by specialty (family physicians vs other specialists).

All statistical tests were 2-sided, with P less than .05 and standardized differences 0.1 and greater considered significant.19 Complete case analyses were performed, as data were rarely missing (residential income quintile, <0.5%; physician specialty, 2.0%). Emigration from Ontario was 5% for nonphysicians and 4% for physicians and was the only reason for loss to follow-up. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Population

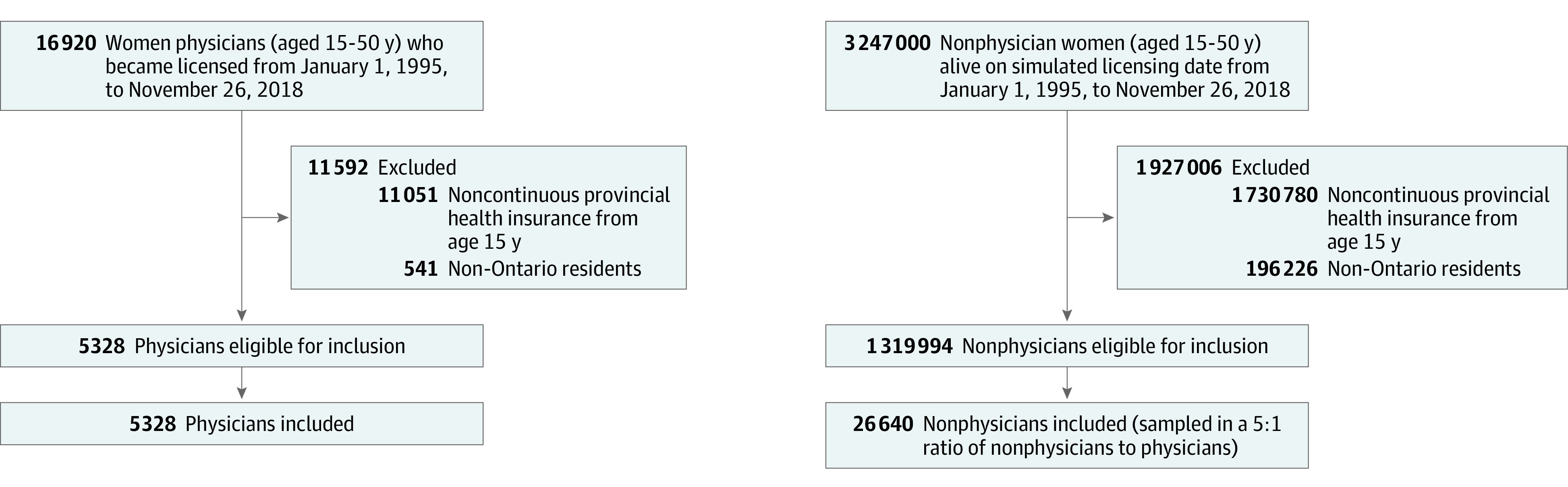

We identified 16 920 physicians of reproductive age who registered with the CPSO between January 1, 1995, and November 26, 2018. After excluding those who had not resided in Ontario since age 15 years, our cohort included 5328 physicians who could be observed over their reproductive life span; 2442 (45.8%) were training or practicing in family medicine, 1878 (35.2%) were training or practicing in other specialties, 900 (16.9%) had not completed training at any point during follow-up and were categorized as specialty not yet determined, and 108 (2.0%) were missing data on specialty. Physicians were successfully frequency matched to 26 640 nonphysicians at age 15 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Included Patients.

Timing of Childbirth

At baseline (age 15 years), women who were ultimately licensed as physicians were more likely to live in high-income urban areas (2092 of 5328 [39.3%] vs 4653 of 26 640 [17.5%]; P < .001), less likely to live in rural areas (390 of 5328 [7.3%] vs 4141 of 26 640 [15.5%]; P < .001), and more likely to be immigrants (881 of 5328 [15.2%] vs 2671 of 26 640 [10.0%]; P < .001) than women who were nonphysicians (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Physicians and Nonphysicians at Age 15 Years.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Standardized difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (n = 5328) | Nonphysicians (n = 26 640) | ||

| Age at index date, median (IQR), y | 15 (15-15) | 15 (15-15) | 0 |

| Era of cohort entry | |||

| 1995-2006 | 2750 (51.6) | 13 750 (51.6) | 0 |

| 2007-2018 | 2578 (48.4) | 12 890 (48.4) | |

| Residential income urban quintile | |||

| 1 (Lowest) | 445 (8.4) | 4231 (15.9) | 0.23 |

| 2 | 548 (10.3) | 4256 (16.0) | 0.17 |

| 3 | 733 (13.8) | 4533 (17.0) | 0.09 |

| 4 | 1094 (20.5) | 4709 (17.7) | 0.07 |

| 5 (Highest) | 2092 (39.3) | 4653 (17.5) | 0.50 |

| Rural residence | 390 (7.3) | 4141 (15.5) | 0.26 |

| Missing | 26 (0.5) | 117 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| Immigration status | |||

| Canadian-born | 4517 (84.8) | 23 969 (90.0) | 0.16 |

| Immigrant | 881 (15.2) | 2671 (10.0) | |

| Comorbidities (Johns Hopkins ADGs) | |||

| 0 | 757 (14.2) | 3750 (14.1) | 0 |

| 1-5 | 3707 (69.9) | 18 121 (68.0) | 0.03 |

| 6-9 | 797 (15.0) | 4157 (15.6) | 0.02 |

| ≥10 | 67 (1.3) | 612 (2.3) | 0.08 |

| Previous live births | |||

| 0 | 5328 (100.0) | 26 612 (99.9) | 0.04 |

| 1 | 0 | 28 (0.1) | 0.04 |

| ≥2 | 0 | ||

Abbreviations: ADG, Aggregated Diagnosis Group; IQR, interquartile range.

Median (interquartile range [IQR]) follow-up was 16.7 (14.7-19.1) years in physicians and 14.8 (11.6-17.9) years in nonphysicians (Table 2). Over the reproductive life span, physicians on average had a decreased rate of childbirth compared with nonphysicians (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.59-0.65; P < .001). In piecewise models, physicians had a markedly decreased rate of childbirth from age 15 to 28 years (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.14-0.18; P < .001), slightly increased rate of childbirth from age 29 to 36 years (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.28-1.43; P < .001), and markedly increased rate of childbirth after age 37 years (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 2.00-3.43), compared with nonphysicians (Table 3).

Table 2. Rate of First Childbirth, Age at First Childbirth, and Cumulative Probability of First Childbirth Among Physicians and Nonphysicians Observed From Age 15 Years.

| Outcome | Nonphysicians (n = 26 640) | Physicians | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 5328) | Family physicians (n = 2442) | Specialists (n = 1878) | ||

| Follow-up, median (IQR), y | 14.8 (11.6-17.9) | 16.7 (14.7-19.1) | 16.5 (14.6-18.8) | 17.9 (16.1-20.3) |

| Rate of childbirth per 100 person-years | 3.40 | 2.31 | 2.83 | 2.42 |

| Time to childbirth, median (95% CI), y | 32.7 (32.5-32.9) | 34.7 (34.5-35.0) | 33.6 (33.4-33.9) | 35.6 (35.2-36.0) |

| Age at first childbirth, median (IQR),a y | 27.0 (22.6-30.2) | 31.6 (29.8-33.6) | 31.4 (29.6-33.3) | 32.1 (30.4-34.2) |

| Cumulative probability of childbirth, % | ||||

| At 20 y | 6.2 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| At 25 y | 18.6 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| At 30 y | 37.7 | 12.3 | 16.1 | 9.4 |

| At 35 y | 57.8 | 52.0 | 61.3 | 46.2 |

| At 40 y | 65.2 | 70.1 | 76.7 | 67.8 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Age at first childbirth among women who experienced a first childbirth during observed follow-up.

Table 3. Relative Rate of First Childbirth Among Physicians and Nonphysicians Observed From Age 15 Years.

| Exposure group | Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Reproductive period | ||

| Nonphysician | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Physician | 0.62 (0.59-0.65)b | <.001 |

| 15-28 y | ||

| Nonphysician | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Physician | 0.15 (0.14-0.18) | <.001 |

| 29-36 y | ||

| Nonphysician | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Physician | 1.35 (1.28-1.43) | <.001 |

| ≥37 y | ||

| Nonphysician | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Physician | 2.62 (2.00-3.43) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Analyses were performed over the entire reproductive period, and in 3 separate intervals: 15-28 years, 29-36 years, and ≥37 years. Because hazards were nonproportional, the hazard ratios presented reflect the average relative rate between physicians and nonphysicians over respective time periods.

Findings were similar after restricting nonphysicians to the highest income quintile: hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.83; P < .001.

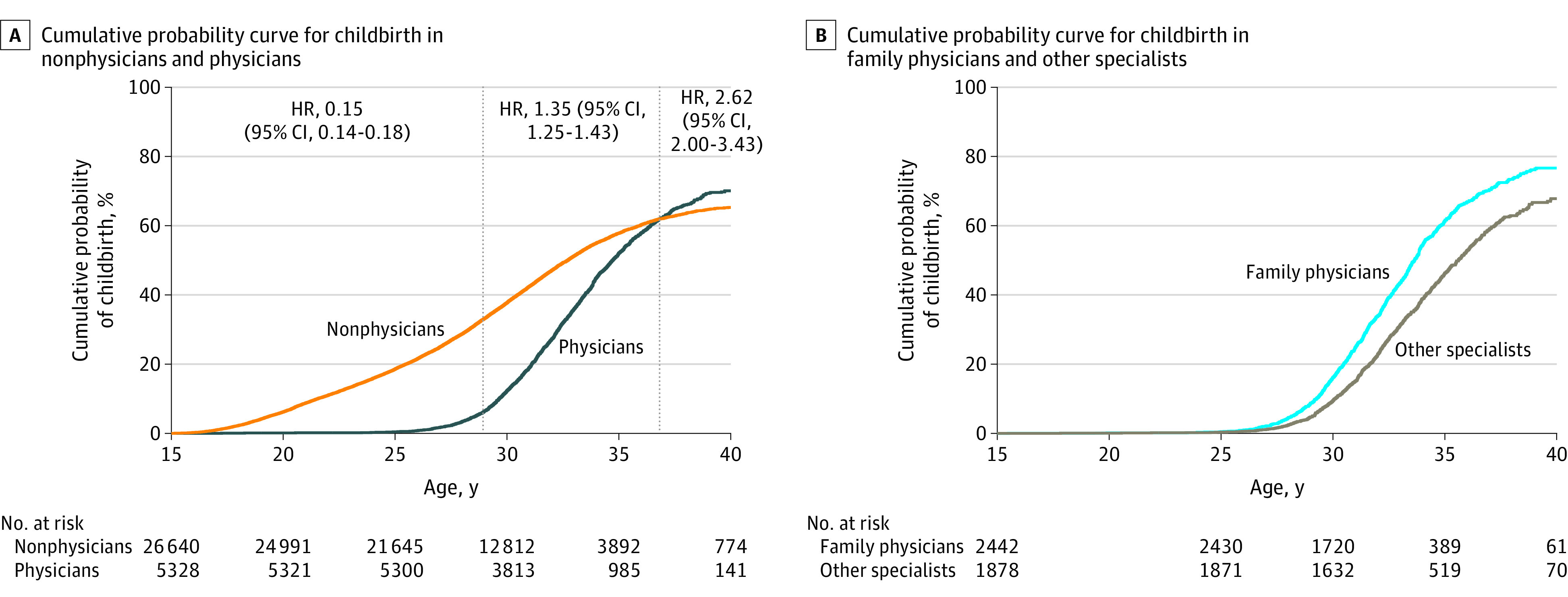

Age at initiation of childbearing was later for physicians than nonphysicians: the cumulative probability of childbirth was 5% at age 19.4 years in nonphysicians and 28.6 years in physicians (Figure 2A). However, by age 37 years, the cumulative incidence of childbirth was similar in both groups (62.7% in physicians, 62.1% in nonphysicians; Figure 2A). Median (IQR) age at first childbirth was 27.0 (22.6-30.2) years for nonphysicians and 31.6 (29.8-33.6) years for physicians (P < .001) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Cumulative Probability Curves for Childbirth .

A, Probability among nonphysicians (n = 26 640) and physicians (n = 5328). B, Probability among family physicians (n = 2442) and other specialists (n = 1878). Age in years serves as the time scale; HR indicates hazard ratio of physicians having children within the indicated age range, with nonphysicians serving as reference [1].

After stratifying by specialty, unadjusted rates of childbirth were higher in family physicians (2.83 per 100 person-years) than in specialists (2.42 per 100 person-years). The cumulative incidence of childbirth was also higher in family physicians than in specialists at all observed ages (Table 2; Figure 2B).

After restricting to nonphysicians in the highest income quintile only, physicians still appeared to delay childbirth relative to nonphysicians to a similar degree (eFigure 2A in Supplement 2). After stratifying by era of birth, physicians born recently (1985-1994) had a lower cumulative incidence of childbirth than physicians of the same age but born earlier (1976-1984; log-rank P < .001; eFigure 2B in Supplement 2). After further stratifying by specialty, patterns of childbirth did not differ substantially for surgical and nonsurgical specialists, but both had a lower cumulative incidence of childbirth relative to family physicians at all ages (log-rank P < .001; eFigure 2C in Supplement 2).

Supplemental Analysis

Approximately 98% of physicians (n = 5227) were nulliparous at the time of licensing (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). In supplemental analyses comparing these physicians with nulliparous nonphysicians, physicians had a decreased rate of childbirth (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.74-0.85; P < .001) compared with nonphysicians while in postgraduate training, but an increased rate (HR, 2.23; 95% CI, 2.10-2.36; P < .001) while in independent practice (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). Results were similar whether a marginal or conditional approach was used to account for matching.

After stratifying by specialty, specialists had a decreased rate of childbirth compared with nonphysicians while in postgraduate training (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.64-0.70; P < .001) but an increased rate while in independent practice (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.92-2.36; P < .001). In contrast, family physicians had a rate of childbirth comparable to nonphysicians while in postgraduate training (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.03; P = .17) but an increased rate while in independent practice (HR, 2.18; 95% CI, 2.03-2.35; P < .001) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

This population-based retrospective cohort study of more than 5300 physicians suggests that women pursuing a career in medicine delay childbearing relative to the general population. Physicians almost universally remained nulliparous prior to age 28 years but had high rates of childbirth thereafter, particularly on entering independent practice. As a result, physicians were often pregnant at advanced maternal ages, when the risks of infertility and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes are more pronounced.10,11

The present study demonstrates that delay of childbirth in physicians begins early and is directly associated with career stage and specialty. Only 2% of physicians had children before completing medical school; while family physicians went on to have rates of childbirth that were comparable to nonphysicians during residency, specialists continued to have decreased rates of childbirth until they began independent practice. This complements the observations of previous surveys, which have found that mean physician age at first childbirth ranges from 30 to 33 years8,21 and that only 14% to 40% of physicians experience a pregnancy during postgraduate training.6,7,22 To our knowledge, only 1 other observational study has compared reproductive patterns between physicians and nonphysicians. Using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database, Wang et al12 showed that the median maternal age at admission for childbirth ranged from 31 to 33 years for physicians and 27 to 31 years for nonphysicians from 1996 to 2013; however, this study did not account for parity or assess outcomes by specialty or career stage. The present work not only confirms that physicians delay childbearing, but also identifies the time period when this delay occurs and suggests that the duration of delay may be lengthening over time rather than shortening.

The present study is the first to map the trajectory of childbirth in women physicians using epidemiologic data and directly model rates of childbirth for both postgraduate trainees and independent practitioners in differing specialties. In contrast to previous surveys, we studied a large population-based cohort of physicians licensed to practice in an entire province. By using validated administrative data, we observed individuals over prolonged follow-up and identified childbirths with little risk of misclassification. This work also provides the context required to understand the factors that contribute to adverse reproductive outcomes among physicians. We show that physicians experience childbirth at an advanced maternal age, which is associated with infertility and pregnancy complications.10,11 By identifying when and in whom pregnancy delay is most likely to occur, the findings can inform the development of strategies to support pregnancy and ensure equity in career advancement opportunities for trainees with children.

Limitations

Several limitations merit consideration. First, to model the reproductive life span, we initiated observation at age 15 years, after exposure status had already been determined. It is possible that early childbirth could have prevented some women from becoming physicians, thus reducing the incidence of childbirth in those who ultimately did complete licensure. To address this, we conducted a supplemental analysis in which we initiated observation at the date of licensing; this confirmed delay of pregnancy in specialists and illustrated when most physicians initiate childbearing. Second, the study cohort does not include women who moved to Ontario after age 15 years. While it is possible that the results may not reflect the experiences of international medical graduates or mobile physicians, we would not anticipate these groups to be any less likely to delay childbirth. Third, we lacked data on relationship status, race/ethnicity, use of assisted reproductive technology, pregnancy intent, and occupation for nonphysicians. Delay of childbirth may also occur in other professions that require prolonged training, such as basic science, law, and engineering. These factors should be studied further; however, the consistency noted even after restricting to high-income nonphysicians and the dramatic shift in rates of childbirth after the completion of postgraduate training suggest that voluntary childlessness or a preference for delay is unlikely to explain the findings. Whether delay of pregnancy is due to career-related concerns,23,24 demanding academic schedules and limited support,4,25,26,27,28,29 or simply personal choice, women physicians in our current system must complete training during their primary reproductive years. Strategies that could be considered to ensure that women physicians can pursue pregnancy if and when they desire include adequate parental leave, remuneration for physicians during parental leave, options for childcare that extend beyond the traditional workday, increased flexibility in both undergraduate and postgraduate training schedules, and a culture of leadership that supports physician mothers and promotes the importance of shared parenting and domestic tasks.4,30

Conclusions

Women physicians appear to postpone childbearing compared with nonphysician counterparts, and this phenomenon is more pronounced in specialists. Although physicians ultimately achieve a similar cumulative probability of pregnancy as nonphysicians, they do so by initiating reproduction at older ages and may be at increased risk of adverse reproductive outcomes. System-level interventions are required to support women physicians who wish to have children at all career stages.

Study protocol

eTable 1. Datasets from CPSO and ICES used in the present study

eTable 2. List of Johns Hopkins Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs), with examples of common included diagnoses

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of physicians and nonphysicians at the date of licensing

eTable 4. Childbirth in nulliparous physicians and nonphysicians after their actual or simulated licensing date respectively

eFigure 1. Plot of log[-log(survival)] versus log (time) for assessment of the proportional hazards assumption

eFigure 2. Sensitivity analyses comparing the cumulative probability of childbirth

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Physicians in Canada. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cihi.ca/en/physicians-in-canada

- 2.Giantini Larsen AM, Pories S, Parangi S, Robertson FC. Barriers to pursuing a career in surgery: an institutional survey of Harvard Medical School students. Ann Surg. Published online October 9, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halley MC, Rustagi AS, Torres JS, et al. Physician mothers’ experience of workplace discrimination: a qualitative analysis. BMJ. 2018;363:k4926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangel EL, Smink DS, Castillo-Angeles M, et al. Pregnancy and motherhood during surgical training. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(7):644-652. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E; Physician Moms Group Study Group . Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033-1036. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):474-479. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troppmann KM, Palis BE, Goodnight JE Jr, Ho HS, Troppmann C. Women surgeons in the new millennium. Arch Surg. 2009;144(7):635-642. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, Jones RD, Jagsi R. Fertility and childbearing among american female physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(10):1059-1065. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aghajanova L, Hoffman J, Mok-Lin E, Herndon CN. Obstetrics and gynecology residency and fertility needs. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(3):428-434. doi: 10.1177/1933719116657193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lean SC, Derricott H, Jones RL, Heazell AEP. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederiksen LE, Ernst A, Brix N, et al. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes at advanced maternal age. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):457-463. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YJ, Chiang SC, Chen TJ, Chou LF, Hwang SJ, Liu JY. Birth trends among female physicians in Taiwan: a nationwide survey from 1996 to 2013. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(7):E746. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics Canada . Live births and fetal deaths (stillbirths), by place of birth (hospital or non-hospital). Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310042901

- 14.Cusimano MCBN, Baxter NN, Sutradhar R, et al. Reproductive patterns, pregnancy outcomes and parental leave practices of women physicians in Ontario, Canada: the Dr Mom Cohort Study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e041281. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Health Indicators 2013: Definitions, Data Sources, and Rationale. Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkins R. Neighbourhood income quintiles derived from Canadian postal codes are apt to be misclassified in rural but not urban areas. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301488517_Neighbourhood_income_quintiles_derived_from_Canadian_postal_codes_are_apt_to_be_misclassified_in_rural_but_not_urban_areas

- 18.Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Health Services Research & Development Center . The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Version 10.0 Release Notes. The Johns Hopkins University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083-3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutradhar R, Baxter NN, Austin PC. Terminating observation within matched pairs of subjects in a matched cohort analysis: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Stat Med. 2016;35(2):294-304. doi: 10.1002/sim.6621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerner LB, Stolzmann KL, Gulla VD. Birth trends and pregnancy complications among women urologists. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):293-297. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabbe SG, Morgan MA, Power ML, Schulkin J, Williams SB. Duty hours and pregnancy outcome among residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 1):948-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85(4):640-646. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kin C, Yang R, Desai P, Mueller C, Girod S. Female trainees believe that having children will negatively impact their careers: results of a quantitative survey of trainees at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1373-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rangel EL, Castillo-Angeles M, Changala M, Haider AH, Doherty GM, Smink DS. Perspectives of pregnancy and motherhood among general surgery residents: a qualitative analysis. Am J Surg. 2018;216(4):754-759. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphries LS, Lyon S, Garza R, Butz DR, Lemelman B, Park JE. Parental leave policies in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):634-639. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips SP, Richardson B, Lent B. Medical faculty’s views and experiences of parental leave: a collaborative study by the Gender Issues Committee, Council of Ontario Faculties of Medicine. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 2000;55(1):23-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacVane CZ, Fix ML, Strout TD, Zimmerman KD, Bloch RB, Hein CL. Congratulations, you’re pregnant! now about your shifts…: the state of maternity leave attitudes and culture in EM. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):800-810. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.6.33843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson AM, Anderson NS III, Gochnour GL, Stewart C. Pregnancy and childbirth during family medicine residency training. Fam Med. 2011;43(3):160-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juengst SB, Royston A, Huang I, Wright B. Family leave and return-to-work experiences of physician mothers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913054. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study protocol

eTable 1. Datasets from CPSO and ICES used in the present study

eTable 2. List of Johns Hopkins Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs), with examples of common included diagnoses

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of physicians and nonphysicians at the date of licensing

eTable 4. Childbirth in nulliparous physicians and nonphysicians after their actual or simulated licensing date respectively

eFigure 1. Plot of log[-log(survival)] versus log (time) for assessment of the proportional hazards assumption

eFigure 2. Sensitivity analyses comparing the cumulative probability of childbirth