Abstract

Background

Virtual reality (VR) computer technology creates a simulated environment, perceived as comparable to the real world, with which users can actively interact. The effectiveness of VR distraction on acute pain intensity in children is uncertain.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of virtual reality (VR) distraction interventions for children (0 to 18 years) with acute pain in any healthcare setting.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and four trial registries to October 2019. We also searched reference lists of eligible studies, handsearched relevant journals and contacted study authors.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cross‐over and cluster‐RCTs, comparing VR distraction to no distraction, non‐VR distraction or other VR distraction.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodological processes. Two reviewers assessed risk of bias and extracted data independently. The primary outcome was acute pain intensity (during procedure, and up to one hour post‐procedure). Secondary outcomes were adverse effects, child satisfaction with VR, pain‐related distress, parent anxiety, rescue analgesia and cost. We used GRADE and created 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

We included 17 RCTs (1008 participants aged four to 18 years) undergoing various procedures in healthcare settings. We did not pool data because the heterogeneity in population (i.e. diverse ages and developmental stages of children and their different perceptions and reactions to pain) and variations in procedural conditions (e.g. phlebotomy, burn wound dressings, physical therapy sessions), and consequent level of pain experienced, made statistical pooling of data impossible. We narratively describe results.

We judged most studies to be at unclear risk of selection bias, high risk of performance and detection bias, and high risk of bias for small sample sizes. Across all comparisons and outcomes, we downgraded the certainty of evidence to low or very low due to serious study limitations and serious or very serious indirectness. We also downgraded some of the evidence for very serious imprecision.

1: VR distraction versus no distraction

Acute pain intensity: during procedure

Self‐report: one study (42 participants) found no beneficial effect of non‐immersive VR (very low‐certainty evidence).

Observer‐report: no data.

Behavioural measurements (observer‐report): two studies, 62 participants; low‐certainty evidence. One study (n = 42) found no beneficial effect of non‐immersive VR. One study (n = 20) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR.

Acute pain intensity: post‐procedure

Self‐report: 10 studies, 461 participants; very low‐certainty evidence. Four studies (n = 95) found no beneficial effect of immersive and semi‐immersive or non‐immersive VR. Five studies (n = 357) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR. Another study (n = 9) reported less pain in the VR group.

Observer‐report: two studies (216 participants; low‐certainty evidence) found a beneficial effect of immersive VR, as reported by primary caregiver/parents or nurses. One study (n = 80) found a beneficial effect of immersive VR, as reported by researchers.

Behavioural measurements (observer‐report): one study (42 participants) found no beneficial effect of non‐immersive VR (very low‐certainty evidence).

Adverse effects: five studies, 154 participants; very low‐certainty evidence. Three studies (n = 53) reported no adverse effects. Two studies (n = 101) reported mild adverse effects (e.g. nausea) in the VR group.

2: VR distraction versus other non‐VR distraction

Acute pain intensity:during procedure

Self‐report, observer‐report and behavioural measurements (observer‐report): two studies, 106 participants:

Self‐report: one study (n = 65) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and one (n = 41) found no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores (very low‐certainty evidence).

Observer‐report: one study (n = 65) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and one (n = 41) found no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores (low‐certainty evidence).

Behavioural measurements (observer‐report): one study (n = 65) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and one (n = 41) reported a difference in mean pain change scores with fewer pain behaviours in VR group (low‐certainty evidence).

Acute pain intensity: post‐procedure

Self‐report: eight studies, 575 participants; very low‐certainty evidence. Two studies (n = 146) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR. Two studies (n = 252) reported a between‐group difference favouring immersive VR. One study (n = 59) found no beneficial effect of immersive VR versus television and Child Life non‐VR distraction. One study (n = 18) found no beneficial effect of semi‐immersive VR. Two studies (n = 100) reported no between‐group difference.

Observer‐report: three studies, 187 participants; low‐certainty evidence. One study (n = 81) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR for parent, nurse and researcher reports. One study (n = 65) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR for caregiver reports. Another study (n = 41) reported no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores.

Behavioural measurements (observer‐report): two studies, 106 participants; low‐certainty evidence. One study (n = 65) found a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR. Another study (n = 41) reported no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores.

Adverse effects: six studies, 429 participants; very low‐certainty evidence. Three studies (n = 229) found no evidence of a difference between groups. Two studies (n = 141) reported no adverse effects in VR group. One study (n = 59) reported no beneficial effect in reducing estimated cyber‐sickness before and after VR immersion.

3: VR distraction versus other VR distraction

We did not identify any studies for this comparison.

Authors' conclusions

We found low‐certainty and very low‐certainty evidence of the effectiveness of VR distraction compared to no distraction or other non‐VR distraction in reducing acute pain intensity in children in any healthcare setting. This level of uncertainty makes it difficult to interpret the benefits or lack of benefits of VR distraction for acute pain in children. Most of the review primary outcomes were assessed by only two or three small studies. We found limited data for adverse effects and other secondary outcomes. Future well‐designed, large, high‐quality trials may have an important impact on our confidence in the results.

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of using virtual reality in a healthcare setting to distract children from pain?

Why is this question important?

Medical procedures, such as health examinations or injections, can cause children to experience pain. In these situations, it is common practice to distract children using toys or play, in order to minimise distress and fear of pain.

One form of distraction that can be used is virtual reality. Virtual reality is an artificial environment with scenes and objects that appear to be real (for example a frozen world, or a wildlife park). Virtual reality can be:

‐ Fully‐immersive: users typically wear a headset with headphones and a screen, and interact with the virtual environment as if they were really in it.

‐ Semi‐immersive: users interact with a partially virtual environment (for example, a flight simulator where the controls are real, but the windows display virtual images).

‐ Non‐immersive: the user is connected to the virtual world by a separate monitor (for example, a computer) but can still experience the real world.

To find out whether virtual reality can distract children from pain, and whether it is associated with any adverse (unwanted) effects, we reviewed the research evidence.

How did we identify and evaluate the evidence?

We searched the medical literature for randomised controlled studies (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups), because these provide the most robust evidence about the effects of a treatment. We compared and summarized their results. Finally, we rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes, and the consistency of findings across studies.

What did we find?

We found 17 studies that involved a total of 1008 children aged from four to 18 years. Medical procedures included injections, taking blood, changing wound dressings, and physical exercise. Studies compared virtual reality against no distraction, or against non‐virtual distraction. No studies compared different types of virtual reality.

During a medical procedure

We cannot tell whether virtual reality reduces self‐reported pain during a medical procedure because we have too little confidence in the evidence available (three studies).

Only two studies investigated changes in pain assessed by an observer (for example, using a rating scale that ranges from 0 (no pain) to 10 (great pain)). These reported conflicting findings: in one study fully‐immersive virtual reality was beneficial compared to non‐virtual distraction, but not in the other.

Fully‐immersive virtual reality may reduce pain assessed by an observer based on children's behaviour (for example, crying, or rubbing a body part in a way that indicates pain) more effectively than non‐virtual distraction (two studies) or no distraction (one study).

Non‐immersive virtual reality was not beneficial for pain assessed by an observer based on children's behaviour compared to no distraction (one study).

After a medical procedure

We cannot tell whether virtual reality can reduce self‐reported pain after a medical procedure, as we have too little confidence in the evidence available (16 studies).

Five studies investigated changes in pain assessed by an observer. Virtual reality was beneficial compared to no distraction in two studies, and also when compared to non‐virtual distraction in another two studies. However, it was no better than non‐virtual distraction in one study.

Two studies investigating pain assessed by an observer based on children's behaviour reported conflicting findings: immersive virtual reality was beneficial compared to non‐virtual distraction in one study, but not in the other.

We cannot tell whether there is a difference between virtual reality and no distraction for pain assessed by an observer based on children's behaviour, as we have too little confidence in the available evidence (one study).

Adverse effects

We cannot tell if virtual reality is associated with adverse effects because we have too little confidence in the evidence available (11 studies).

What does this mean?

We have little to very little confidence in the evidence we identified. It is unclear from our review whether virtual reality distraction makes a difference to pain in children. There is a need for large, well‐designed studies in this area.

How up‐to date is this review?

The evidence in this Cochrane Review is current to October 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Virtual reality distraction compared to no distraction.

| Virtual reality distraction compared to no distraction | ||||||

| Patient or population: children (0 to 18 years) Setting: inpatient and outpatient paediatric healthcare setting Intervention: virtual reality distraction Comparison: no distraction | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comment | |

| Risk with no distraction | Risk with virtual reality distraction | |||||

| Acute pain intensity: self‐report (during procedure) | 42 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b | One study found no evidence of beneficial effect of non‐immersive VR compared to no distraction. | |||

| Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (during procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (during procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 62 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | One study found no evidence of beneficial effect of non‐immersive VR and another study found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR compared to no distraction. | |

| Acute pain intensity: self‐report (post‐procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 461 (10 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,d | Four studies found no evidence of a beneficial effect of immersive, semi‐immersive or non‐immersive VR. Five other studies found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR compared to no distraction. Another study reported less pain in the VR group. |

|

| Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (post‐procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 216 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,e | Two studies found evidence of a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR compared to no distraction for primary caregiver/parent and nurse observer‐reports. One of the studies also found evidence of a beneficial effect favouring immersive VR compared to no distraction for researcher observer‐reports. | |

| Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (post‐procedure) | 42 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b | One study found no evidence of beneficial effect of non‐immersive VR compared to no distraction. | |||

| Adverse effects (related to engagement with VR) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 154 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,d | Three studies reported no adverse effects. Two studies reported mild adverse effects in the VR group. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; VR: virtual reality | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aUnclear risk of selection bias; high risk of performance and detection bias. Downgraded one level for serious study limitations.

bSmall sample size with a wide 95% CI. Downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision.

cDifferent populations in terms of age, conditions and settings. Downgraded one level for serious indirectness.

dDifferent populations in terms of age, conditions and settings; differences in how the intervention was delivered; and differences in way outcomes measured. Downgraded two levels for very serious indirectness.

eDifferent populations in terms of conditions and settings. Downgraded one level for serious indirectness.

Summary of findings 2. Virtual reality distraction compared to non‐VR distraction.

| Virtual reality distraction compared to non‐VR distraction | ||||||

| Patient or population: children (0 to 18 years) Setting: inpatient and outpatient paediatric healthcare setting Intervention: virtual reality distraction Comparison: other non‐VR distraction | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comment | |

| Risk with other non‐VR distraction | Risk with virtual reality distraction | |||||

| Acute pain intensity: self‐report (during procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 106 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b | One study found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and another study found no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores between immersive VR and non‐VR distraction. | |

| Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (during procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 106 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | One study found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and another study found no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores between immersive VR and non‐VR distraction. | |

| Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (during procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 106 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | One study found beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and another study reported evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores between immersive VR and non‐VR distraction with less pain behaviours observed for the VR group. | |

| Acute pain intensity: self‐report (post‐procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 575 (8 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b | Two studies found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and another two studies reported a between group difference favouring immersive VR. Two studies found no evidence of beneficial effect for immersive and semi‐immersive VR and another two studies reported no evidence of a difference in mean pain changes scores between immersive VR and non‐VR. | |

| Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (post‐procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 187 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | One study found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR for parent, nurse and researcher reports and another study also found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR for caregiver observed report. Another study reported no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores between immersive VR and non‐VR distraction. | |

| Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (post‐procedure) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 106 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW a,c | One study found evidence of beneficial effect favouring immersive VR and another study found no evidence of a difference in mean pain change scores between immersive VR and non‐VR distraction. | |

| Adverse effects (related to engagement with VR) | Data not pooled due to high heterogeneity in interventions, comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes. | ‐ | 429 (6 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a,b | Three studies found no evidence of a difference between immersive VR and non‐VR distraction for adverse effects. Another two studies reported no adverse effects in the VR group. One study reported that the change in estimated cybersickness before and after VR immersion was not significant. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; VR: virtual reality | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aUnclear risk of selection bias; high risk of performance and detection bias. Downgraded one level for serious study limitations.

bDifferent population in terms of age, conditions and settings; differences in non‐VR distraction comparisons; and differences in way outcomes measured. Downgraded two levels for very serious indirectness.

cDifferent population in terms of age, conditions and settings; and differences in non‐VR distraction comparisons. Downgraded one level for serious indirectness.

Summary of findings 3. Virtual reality distraction compared to other VR distraction.

| Virtual reality distraction compared to other VR distraction | |||||

| Patient or population: children (0‐18 years) Setting: inpatient and outpatient paediatric healthcare setting Intervention: virtual reality distraction Comparison: other VR distraction | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with other VR distraction | Risk with Virtual reality distraction | ||||

| Acute pain intensity: self‐report (during procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (during procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (during procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Acute pain intensity: self‐report (post‐procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (post‐procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (post‐procedure) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Adverse effects (related to engagement with VR) | No study of this comparison reported this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

Background

Description of the condition

Healthcare examinations, treatments, procedures and interventions are typical extreme stressors that can lead to pain for children (Clift 2007; Fox 2016; Horstman 2002; Melnyk 2000; Racine 2016; Rassin 2004; Wollin 2004). A recent definition describes pain as "a distressing experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage with sensory, emotional, cognitive, and social components” (Williams 2016). Similar to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) original definition of pain (IASP 2011), this definition highlights that pain has both distressing sensory (i.e. pain intensity) and emotional (i.e. any negative affect secondary to pain such as distress; including anxiety, fear and/or stress) features, associated with actual or potential tissue damage. The sensory and emotional correlates of pain are ‘subjective psychological states’ (Aydede 2017) and can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between (Brown 2012; Curtis 2012; Goodenough 1999; McGrath 2008). This may be especially the case for children under eight years of age, who by virtue of their developmental abilities may be unable to differentiate pain meaningfully from other unpleasant emotions such as fear and anxiety (Blount 2006; Goodenough 1999). These two dimensions of pain (i.e. pain intensity and pain‐related distress) are important to consider in ensuring pain management strategies reduce not only pain intensity but also the distress, anxiety and/or fear associated with medical treatment‐related pain (Goodenough 1999).

Pain impacts on child and parent satisfaction with healthcare delivery and services. In an investigation of the views and experiences of children in Council of Europe member states, Kilkelly 2011 found that 60.1% of child participants rated ‘not being in pain’ as an important element of health care. Yet evidence suggests that acute pain management in children is not always optimal (Cummings 1996; Groenewald 2012; Taylor 2008). Figures estimate that 27% of children experience moderate to severe pain in hospital, with teenagers and infants experiencing higher prevalence rates of 38% and 32% respectively (Groenewald 2012). This can impact on children’s physiological, psychological and emotional well‐being, in both the short and long term.

It is inevitable that children admitted to healthcare settings will likely be exposed to potentially painful procedures on a daily basis. For instance, Stevens 2011 reported that more than three‐quarters (78.2%) of child participants (n = 3822) in their study had undergone at least one painful procedure in a 24‐hour period preceding data collection. While each child was exposed to an average of 6.3 (range 1 to 50) procedures, only a small portion (28.3%) of children had interventions specifically linked to the painful procedure. While acknowledging that certain procedures are essential for routine medical and surgical care, these procedures/treatments can cause pain for the child. Children can feel "threatened by the monster of medical care" where they fear being hurt, forced and violated by the adults delivering that care (Forsner 2009). Pain results in anxiety and stress, which, in turn, negatively impacts not only on a child’s ability to cope with the treatment/intervention but also on their recovery (Li 2009). Inadequate relief of pain during childhood treatments may have long‐term negative effects on future pain tolerance and pain responses (Young 2005).

Non‐pharmacological techniques (e.g. imagery, hypnosis, story‐telling, play, music) have long been promoted as useful adjuncts to pharmacological analgesics (Butler 2005; Klassen 2008; Landier 2010). Yet, aside from distraction and hypnosis, and more recently combined cognitive behavioural therapy and breathing, there is limited evidence to support the efficacy of many of these conventional psychological interventions (e.g. relaxation, guided imagery, music) for reducing procedure‐related pain in children (Birnie 2018; Stinson 2008). In addition, it has been documented that children may benefit more from interactive (e.g. playing a video game) as opposed to passive (e.g. watching a video game) distraction strategies (Wohlheiter 2013). One such recent ‘active’ adjunctive analgesic technique gaining momentum is virtual reality (VR) (Hoffman 2011).

With the use of technology becoming increasingly prevalent in children’s daily lives, alongside the drive towards e‐health and the empowered patient, it seems reasonable to propose that interactive technologies, if proven effective, should be considered as vital intervention vehicles for enhancing health outcomes for children. The use of VR during healthcare procedures/treatments can create a child‐friendly and developmentally sensitive environment, thereby contributing to the European campaign for a child‐friendly approach to health care (Council of Europe 2011).

Description of the intervention

VR, also referred to as virtuality, is defined as a computer technology that creates a simulated environment/world that users perceive as comparable to real world objects/events (Aguinis 2001; Chan 2007; Hoffman 2004a; Weiss 2003). The user’s attention is drawn away from real world visual, auditory and tactile stimuli, and into the virtual world by the multi‐sensory (i.e. sight, sound, touch) nature of the virtual environment (Gold 2006). VR interventions can vary considerably in terms of three core aspects: types of equipment used; content and nature of the virtual world; and levels of engagement users might have. VR draws the user’s attention to a virtual world/environment using real‐time computer graphics and various inputs (e.g. position trackers, mouse and data glove) and output (e.g. shutter glasses, head‐mounted displays, haptic and audio‐visual) devices that make the person an active participant within a computer‐generated three dimensional world. Active interaction, navigation and immersion are key characteristics of VR systems (Aguinis 2001).

The content of some VR interventions has been developed specifically for certain types of procedures (e.g. Snow World and Ice Cream Factory, devised for burn wound dressings) (Chan 2007; Hoffman 2004a), whereas other VR interventions (e.g. Virtual Gorilla) are selected for convenience to engage children at the time of invasive medical procedures (Gershon 2003; Wolitzky 2005). All VR systems are categorised according to how immersive or non‐immersive they are. With non‐immersive systems, the user is connected to the virtual world (by an external monitor) but can still communicate with the real world (e.g. the healthcare environment; Nilsson 2009). With full immersion, the user’s visual and auditory perception and haptics of stimuli in the outside world is blocked as they become fully enveloped in the computer‐generated virtual environment through the use of a head‐mounted display and a tracker position sensor (e.g. a helmet and headphones which exclude visual and auditory inputs from the healthcare environment; Gold 2006; Weiss 2003). It is this sense of presence and immersive attention (i.e. the ability to give users the sense they are somewhere else) that sets VR apart from other technological interventions such as watching television or video movies, or playing simulated or interactive video games (Chan 2007; Gorini 2011; Hoffman 2004a; Nilsson 2009; Steele 2003; Weiss 2003).

How the intervention might work

VR has been used in many contexts (e.g. treating phobias and post‐traumatic stress disorders; training military and medical personnel). For the purposes of this review, the focus is on the use of VR in the reduction of acute pain intensity and pain‐related distress associated with medical treatments/interventions in any healthcare setting. The theory of how VR works in such instances is as a form of distraction; where distraction is referred to as purposefully directing attention away from undesirable sensations (Mobily 1993). Distraction is a common coping mechanism used by school aged children and adolescents for enduring unpleasant situations (Schneider 2000). Distraction interventions function by diverting the child’s attention away from the stimulus producing the pain and refocusing the child’s attention towards a more pleasant and positive stimulus (i.e. the virtual environment; McCaul 1984; Schneider 2000). VR interventions are thought to manifest analgesic effects by altering pain perception through distracting user attention away from the painful procedure, in addition to changing the way a person interprets incoming pain signals, consequently reducing the amount of pain‐related brain activity (as seen on MRI imagery) (Morris 2009). VR exposure can target cognitive and affective pain pathways, thereby decreasing pain intensity, distress, and anxiety by altering how pain signals are processed in the central nervous system. This is achieved by a number of mechanisms including attentional distraction, conditioning of VR imagery and reduced pain.

VR distraction has been used, for example, to minimise children’s anxiety associated with chemotherapy (Ahmadi 2001; Schneider 1999), to reduce children’s pain during burn wound care (Hoffman 2000; Hoffman 2001; Hoffman 2004a), to access intravenous ports in paediatric oncology patients (Wolitzky 2005), to alleviate pain/anxiety for invasive medical procedures such as venipuncture, lumbar puncture, and bone marrow aspirates (Gershon 2003; Gold 2006; Nilsson 2009; Wint 2002), to help adolescents with cerebral palsy as they endure physiotherapy (Steele 2003), and to reduce children’s preoperative anxiety using handheld video games or films (Low 2008; Patel 2006). Together with pharmacological interventions, distraction is thought to be an effective pain management strategy by cognitively redirecting attention away from pain to a more pleasant stimulus, thereby assisting children to cope with the distress of medical treatments. Long‐term benefits include advantages for later adult life, as pain experienced during medical treatments in childhood is predictive of pain during subsequent medical procedures and avoidance of medical care during young adulthood (Blount 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

VR is a recent technological advancement with the potential to modulate children’s pain when they are undergoing healthcare treatments (e.g. intravenous cannulation, lumbar puncture, wound dressings, chemotherapy, bone marrow aspirates). For instance, Gold 2006 reported that children who underwent intravenous cannulae placement without distraction reported a fourfold increase in affective pain when compared to children immersed in a VR intervention. Additionally, children who received a VR intervention were twice as satisfied with their pain management as compared to children not exposed to a VR intervention. Schneider 2000 found 82% of children indicated that their chemotherapy treatment was better with VR as compared to previous chemotherapy treatment without VR. Parents were also satisfied with the use of VR interventions and believed such interventions did reduce children’s pain and enhance children’s cooperation during medical treatments (Gold 2006). In a review, Hoffman 2011 reported a 35% to 50% reduction in procedural pain in burn patients when in a distracting immersive VR.

Despite these positive evaluations and reports of pain reduction, there remains uncertainty over the effectiveness of VR interventions (Dahlquist 2010; Garrett 2014; Kenney 2016; Malloy 2010; Morris 2009). In addition, in comparison to other simpler forms of non‐pharmacological distraction interventions (e.g. imaginary, breathing, positive thinking), there have been some common criticisms levelled at VR such as high costs, bulky equipment, the need for specialist technological skills and the potential for cyber‐sickness, all of which may threaten the widespread implementation of VR for therapeutic healthcare interventions (Bohil 2011). It is important to conduct this systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of VR as a pain distractor during healthcare treatments. As few psychological interventions incorporate, or evaluate the effectiveness of, modern and novel interactive technologies such as VR, this review complements other Cochrane Reviews (e.g. Birnie 2018) that evaluate the effectiveness of non‐pharmacological distraction‐based interventions for minimising pain in children when undergoing medical treatments.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of VR distraction interventions for children (0 to 18 years) with acute pain in any healthcare setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cross‐over and cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

We included children aged from birth up to and including 18 years, with acute pain in any healthcare setting.

Types of interventions

Any technology aimed at creating a virtual environment/world, including immersive and/or non‐immersive VR of any intensity or duration, with the purpose of reducing acute pain intensity. These interventions may be used with or without pharmacological support. We included interventions that used any combination of input and output devices (e.g. mouse and shutter glasses; position tracker and head‐mounted display). For the intervention to be VR the participant must be actively interacting with the virtual environment which responds to their actions. We excluded interventions where the user was a passive observer, such as watching a virtually‐simulated movie as opposed to actively engaging in a virtual environment through physical movement.

Interventions of interest were:

VR distraction compared to no distraction;

VR distraction compared to non‐VR distraction;

VR distraction compared to other VR distraction (grouped by level of immersion which takes account of type of technical device, VR environment and level of user interaction).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Acute pain intensity:

-

1. during the procedure, measured using:

self‐report;

observer‐report;

behavioural measurements (observer‐report).

-

2. post‐procedure (up to one hour), measured using:

self‐report;

observer‐report;

behavioural measurements (observer‐report).

Secondary outcomes

Adverse effects related to engagement with VR. These may include motion sickness, ocular problems (e.g. eye strain, blurred vision), balance disturbances, headaches, fatigue and repetitive strain injuries.

Child satisfaction with VR.

Child pain‐related distress, for example, self‐report, observer‐report or behavioural measurements of child distress, anxiety, fear and/or stress.

Parent anxiety using parent self‐reported anxiety scales or inventories.

Administration of rescue analgesia (i.e. administration of additional analgesic medications to treat acute pain not controlled by child’s scheduled analgesic regimen).

Cost, which may include cost of the VR intervention or duration of child’s treatment (measured in original currency).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

With assistance from the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care (PaPaS) Review Group, we searched the following electronic databases up to October 2019.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via CRSO searched on 17/10/2019

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1989 to 17 October 2019)

Embase (OvidSP) (1989 to 17 October 2019)

CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (1989 to 17 October 2019)

PsycINFO (Proquest) (1989 to 17 October 2019)

We used a combination of controlled vocabulary under the existing databases' organisational systems (e.g. MeSH and EMTREE) and free text terms. We did not apply language restrictions. Search dates start at 1989 as the intervention did not exist before this time. Please see the appendices for the search strategies and terms used for each of the databases: CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), Embase (Appendix 3), CINAHL (Appendix 4), and PsycINFO (Appendix 5).

Searching other resources

We searched for grey literature and ongoing trials using the following methods.

Proceedings from conferences

ProQuest Digital Dissertations and Theses

Index to Theses (Ireland and UK)

TrialsCentralTM (www.trialscentral.org)

Clinical trials register (Clinicaltrials.gov)

WHO Clinical Trial Search Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch)

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com)

We searched reference lists from retrieved eligible studies for other studies potentially eligible for inclusion. We handsearched relevant journals including Virtual Reality (from inception in 1995 to October 2019) and The International Journal of Virtual Reality (from inception in 1998 to October 2019). We contacted experts in the field and authors of included studies about other potentially relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (VL, AM) independently assessed each title and abstract retrieved from the electronic searches for relevance using Covidence 2018. We resolved any discrepancies through discussion with a third review author (PB, PH or DD) acting as arbiter as required. We sourced and assessed the full paper if no abstract was available. We obtained and read full texts of the studies that potentially met our inclusion criteria. Two review authors (VL, AM) independently assessed these full texts against the inclusion criteria before a final decision regarding inclusion/exclusion was confirmed. We resolved any discrepancies by consensus or discussion with a third review author (PB, PH or DD) acting as arbiter where necessary. We listed all potentially relevant papers excluded from the review at full‐text stage in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, noting reasons for exclusion. We listed publications in abstract form only in excluded studies. We collated and reported multiple details of the same study/duplicate publications, to ensure that each study (rather than each report) was the unit of interest in the review. We used an adapted PRISMA flow chart to report the screening and selection process.

Data extraction and management

We designed, piloted and amended as necessary a data extraction form based on the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group template. Two review authors (VL, AM) independently extracted and managed data from each included RCT using the tailored data extraction form. Data extracted from included studies comprised of the following items.

Methods: aim of study, study design, method of participant recruitment, funding source, declaration of interests for primary investigators, statistical methods and consumer involvement.

Risk of bias: as specified under Assessment of risk of bias in included studies.

Participants: description, participant inclusion and exclusion criteria, geographical location, setting, number, age, gender, ethnicity, principal and stage of diagnosis, type of procedure/treatment receiving.

Intervention: details of intervention (including aim, content, format, source, setting) and control/usual care, delivery of intervention (including timing, frequency, duration), providers of the intervention and intervention fidelity/integrity.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcome measures (as detailed under Types of outcome measures), timing of assessment and methods of assessing outcome measures, follow up for non‐respondents and adverse events.

We resolved any discrepancies in data extraction between the two review authors through discussion or if required, consultation with a third review author (PB, PH or DD). The first review author (VL) entered the data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014), with the second review author (AM) checking the accuracy of data entry. We attempted to obtain any missing, unclear or incomplete data by contacting the study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (VL, AM) independently assessed risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion and consensus with a third review author (DD) acting as arbiter as required. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study using the 'Risk of bias' tool in Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014). We assessed the following for each study.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence for each included study as having:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement).

For cross‐over studies we also assessed for period effects (i.e. systematic differences between responses in the second period compared to the first period not due to different interventions) as having:

low risk of bias (1:1 allocation ratio where any general trends in outcomes over time will cancel; period effects included in analysis);

high risk of bias (unequal proportions of participants randomised to the different intervention sequences where a general trend in outcomes over time may lead to bias; no period effects included in analysis); or

unclear risk of bias (insufficient or no information available to permit judgement on period effects).

For random sequence generation, studies assessed as high risk of bias were excluded.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

The method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of assignmet, during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the allocation concealment methods for each included study as having:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (e.g. open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes; alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk of bias (method of concealment not clearly described or not described in sufficient detail to allow for a definite judgement).

For allocation concealment, we excluded studies assessed as having high risk of bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed methods as having:

low risk of bias (blinding of participants and study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken);

high risk of bias (no blinding, incomplete or attempted blinding of participants and study personnel, and possible that non‐blinding of others likely to introduce bias; or attempted blinding could have been broken; or reported as not blinded due to nature of the intervention); or

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information on blinding of participants and study personnel to permit a judgement).

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as having:

low risk of bias (clear statement that outcome assessors were unaware of treatment allocation, and describes how this was achieved);

high risk of bias (outcome assessment not blinded or or reported as not blinded due to nature of the intervention); or

unclear risk of bias (states outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation but lacks a clear statement on how it was achieved).

For cross‐over studies we also assessed for carry‐over effects (i.e. effects of an intervention given in one period continue into a subsequent period, thereby interfering with the effects of the second intervention) as:

low risk of bias (sufficient time for carry‐over effects to disappear before outcome assessment in second period);

high risk of bias (insufficient time for carry‐over effects to disappear before outcome assessment in second period); or

unclear risk of bias (insufficient or no information available to permit judgement on carry‐over effects).

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We assessed the methods used to deal with incomplete data as having:

low risk of bias (no missing outcome data, less than 10% missing data, missing data balanced in numbers across intervention groups with similar reasons for missing data across groups);

high risk of bias (used 'completer' analysis, more than 10% missing data); or

unclear risk of bias (no or insufficient information provided to permit judgement).

Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We assessed whether primary and secondary outcome measures were pre‐specified and whether these were consistent with those reported. We assessed the methods as having:

low risk of bias (e.g. all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (e.g. not all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported and outcomes of interest are reported incompletely, and so cannot be used); or

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information available to permit judgement).

For cross‐over studies we also assessed for first period data on a basis of a test for carry‐over as having:

low risk of bias (results from both periods reported);

high risk of bias (results from first period only reported); or

unclear risk of bias (insufficient or no information available to permit judgement on reporting bias).

Size of study (checking for possible biases confounded by small size based on number of participants in each study arm)

We evaluated risk of bias for each included study according to the Cochrane PaPaS Review Group guidance on sample size based on the number of participants included in each study arm. We assessed studies to be at:

low risk of bias (≥ 200 participants per treatment arm);

high risk of bias (< 50 participants per treatment arm); or

unclear risk of bias (50 to 199 participants per treatment arm).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed whether each trial was free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias as having:

low risk of bias (appears to be free of other sources of bias);

high risk of bias (has at least one important risk of bias e.g. potential source of bias related to the specific study design used, extreme baseline imbalance etc.); or

unclear risk of bias (there may be risk of bias but there is insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists, or insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias).

We had planned to also extend the risk of bias to include specific questions for cluster trials (e.g. selective recruitment of cluster participants; baseline reporting of comparability of clusters) (Higgins 2011; Ryan 2011), but this was not necessary as we did not identify any cluster‐RCTs for inclusion in the review. We will address this in future updates if applicable.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to analyze the data using RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2014). For dichotomous outcomes, we planned to report risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous outcomes, we planned to report mean differences (MD) (if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials) and 95% CI. For trials that used different methods to measure the same outcome, we planned to use standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% CI. We planned to undertake a meta‐analysis if studies were sufficiently similar in design, population, interventions and outcomes, but this was not possible. We will undertake a meta‐analysis in future updates, should more data become available.

Unit of analysis issues

We acknowledged that issues could arise from the inclusion of cross‐over designs and cluster‐RCTs. We did not identify any eligible cluster‐RCTs. In future updates of this review, if we identify any cluster‐RCTs, we will use effect size estimates and standard errors, adjusted in the analysis for clustering, and combine the studies using the generic inverse‐variance method (Higgins 2011). We will adjust sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC.

We identified one within‐subject (cross‐over) study as eligible for inclusion in the review. We analysed the data according to recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011) for cross‐over trials. We used the effect estimate and standard deviation based on a paired t‐test. If we identify additional cross‐over studies in future updates, we will combine the studies using the generic inverse‐variance method (Higgins 2011, section 16.4) and seek statistical advice for this part of the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors for missing data. We noted levels of attrition in the included studies. We were unable to perform any meta‐analysis in this review due to clinical heterogeneity in population and procedural conditions. In future updates of this review, we will conduct analysis of outcomes on an intention‐to‐treat basis (i.e. by including all randomised participants in the group to which they were randomised regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention). Where this is not possible (i.e. data were not provided by study authors), we will conduct an analysis based on the number of participants for whom outcome data are known. As part of our 'Risk of bias' assessment, we reported the number of participants lost to follow‐up and the levels of, and reasons for, attrition in each trial. We had intended to investigate the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis; however, there were not enough data included in the review to conduct this analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether studies were sufficiently similar (based on consideration of populations, interventions, settings or methodological features) to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis and we assessed the degree of statistical heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by examining the Tau² (tau‐squared), I², and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if:

-

the I² value was 50% or higher; and either

there was inconsistency between trials in direction or magnitude of effects (judged visually), or a low (P < 0.10) P value in the Chi² test for heterogeneity; or

the estimate of between‐study heterogeneity (Tau²) was above zero.

We had intended to investigate the presence of substantial heterogeneity using subgroup and sensitivity analyses however there were insufficient data included in the review to conduct these analyses. We did consider whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it had been, we would have used a random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We detected substantial clinical heterogeneity across included studies and therefore do not report pooled results from meta‐analysis but instead provide a narrative description of data.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not identify sufficient trials (at least 10) to evaluate reporting biases graphically using funnel plots. In future updates of this review, if 10 or more studies are included, we will conduct formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry; for continuous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Harbord 2006. We will perform exploratory analyses if asymmetry is detected in any of these tests or is suggested by a visual assessment to investigate it. Where we suspect reporting bias we will attempt to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this is not possible, and the missing data are thought to introduce serious bias, we will explore the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We planned to use a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis to produce a summary of effect based on the anticipated variability in the populations and interventions of included studies. However, we did not conduct meta‐analysis due to a lack of suitable studies. We judged that the heterogeneity in interventions and comparisons, participants, settings, and outcomes in our included studies would not contribute to meaningful conclusions from a statistically‐pooled result. Therefore, we present the data in additional tables (Table 4 and Table 5), and narratively describe the results. Where possible we calculated effect estimates for each study using Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan 2014). In future updates of this review, if we identify enough studies suitable to be combined and undergo quantitative analysis, we will conduct meta‐analysis.

1. Comparison 1: Virtual reality distraction compared to no distraction.

| Study | Measurement Tool | Data VR Intervention | Data No Distraction | P value |

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: self‐report (during the procedure) | ||||

| Nilsson 2009 | Colour Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; 0 = no pain, 10 = most pain) |

Mean (SD) During procedure (retrospective recorded after procedure) 2.20 (2.78); N = 21 |

Mean (SD) During procedure (retrospective recorded after procedure) 1.64 (2.17); N = 21 |

|

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (during the procedure) | ||||

| Nilsson 2009 | Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale (total score out of maximum 10; higher score indicates pain) |

Mean (SD) During procedure (retrospective recording after procedure) 1.10 (2.00); N = 21 |

Mean (SD) During procedure (retrospective recording after procedure) 1.67 (1.59); N = 21 |

|

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: self‐report (post‐procedure up to one hour) | ||||

| Jeffs 2014 | Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (scale range 0 to 100; no pain to worst pain) |

Between group difference Difference: 9.7 mm, 95% CI: ‐9.5 to 28.9 VR group reported non‐statistical significant less procedural pain compared to no distraction group |

P = 0.32 | |

| Mean (SD) 58.20 (31.7); N = 8 |

Mean (SD) 37 (31.80); N = 10 |

|||

| Nilsson 2009 | Colour Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; 0 = no pain, 10 = most pain) |

Mean (SD) 1.05 (1.74); N = 21 |

Mean (SD) 0.51 (0.99); N = 21 |

|

| Schmitt 2011 | Graphic Rating Scale (scale range 0 to 100; no pain to worst pain) |

Mean (SD) After treatment condition 40.15 (30.87); N = 52 |

Mean (SD) After treatment condition 54.48 (26.68); N = 52 |

|

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) (post‐procedure up to one hour) | ||||

| Nilsson 2009 | Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale (total score out of maximum 10; higher score indicates pain) |

Mean (SD) 0.29 (0.56); N = 21 |

Mean (SD) 0.19 (0.51); N = 21 |

|

| Outcome: Child pain related distress (incl. anxiety, fear and distress) | ||||

| Nilsson 2009 | Facial Affective Scale (scale range 0 to 1; from least to most distressed) |

Median During procedure (retrospective recording after procedure) 0.47 (N = 21) |

Median During procedure (retrospective recording after procedure) 0.47 (N = 21) |

NS |

| Mean (SD) During procedure (retrospective recording after procedure) 0.41 (0.29) |

Mean (SD) During procedure (retrospective recording after procedure) 0.47 (0.21) |

|||

| Wolitzky 2005 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 100; none to maximum pain or anxiety) |

Composite score (mean of VAS anxiety and pain scores) During procedure (retrospective recorded after procedure) 12.00 (16.36) |

Composite score (mean of VAS anxiety and pain scores) During procedure (retrospective recorded after procedure) 34.45 (41.80) |

|

SD: standard deviation N: number

2. Comparison 2: Virtual reality distraction compared to non‐VR distraction.

| Study | Measurement Tool | Data VR Intervention | Data Non‐VR Distraction | P Value |

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: self‐report (during the procedure) | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; from no pain to pain as bad as it could possibly be) |

Mean change scores After dressing removal (taken as during procedure) 2.9 (2.3); N = 20 |

Mean change scores After Dressing removal (taken as during procedure) 4.2 (3.2); N = 21 |

P = 0.16 |

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (during the procedure) | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; from no pain to worst pain) |

Mean change scores After dressing removal (during procedure) 3.5 (2.5); N = 20 |

Mean change scores After dressing removal (during procedure) 3.8 (3.2); N = 21 |

P = 0.71 |

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurements (observer‐report) (during the procedure) | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale (total score out of maximum 10; higher score indicates pain) |

Mean change scores After dressing removal (during procedure) 2.9 (2.4); N = 20 |

Mean change scores After dressing removal (during procedure) 4.7 (2.5); N = 21 |

P = 0.02 |

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: self‐report (post‐procedure up to one hour) | ||||

|

Chan 2019 Emergency department |

Faces Pain Scale‐Revised (scale range 0 to 10; no pain to very much pain) |

Between group difference: ‐1.78; 95% CI, ‐3.24 to ‐0.32 | P = 0.018 | |

| Change in FPS‐R from baseline ‐1.39; 95% CI ‐2.42 to ‐0.36; N = 64 |

Change in FPS‐R from baseline 0.39; 95%CI ‐1.45 to 0.67; N = 59 |

VR intervention P = 0.009 Non‐VR distraction P = 0.47 |

||

|

Chan 2019 Outpatient pathology |

Faces Pain Scale‐Revised (scale range 0 to 10; no pain to very much pain) |

Between group difference: ‐1.39; 95% CI, ‐2.68 to ‐0.11 | P = 0.034 | |

| Change in FPS‐R from baseline 1.37; 95% CI, 0.50 to 2.23; N = 63 |

Change in FPS‐R from baseline 2.76; 95% CI, 1.79 to 3.72; N = 66 |

VR intervention P = 0.003 Non‐VR distraction P < 0.001 |

||

| Kipping 2012 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; no pain to pain as bad as it could possibly be) |

Mean change scores After dressing application (post‐procedure) 2.33 (3.4); N = 20 |

Mean change scores Dressing application (post‐procedure) 3.8 (3.6); N = 21 |

P = 0.40 |

| Jeffs 2014 | Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (scale range 0 to 100; higher score indicates more pain) |

Between group difference Difference: 23.7 mm, 95% CI: 2.4 to 45.0 VR group reported significant less procedural pain than PD group |

P = 0.029 | |

| Means (SD) After procedure 58.2 (31.7); N = 8 |

Means (SD) After procedure 30.2 (29.2); N = 10 |

|||

| Walther‐Larsen 2019 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 100; higher scores indicates more pain) |

Mean Difference 5; 95% CI, ‐3 to 13 | P = 0.23 | |

| Median (IQR) 27 (8 to 33) |

Median (IQR) 15 (5 to 30) |

|||

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: observer‐report (post‐procedure up to one hour) | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) |

Mean change scores After dressing application (post‐procedure) 2.6 (3.5); N = 20 |

Mean change scores After dressing application (post‐procedure) 2.2 (4.0); N = 21 |

P = 0.75 |

| Outcome: Acute pain intensity: behavioural measurements (observer‐report) (post‐procedure up to one hour) | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale (total score out of maximum 10; higher score indicates pain) |

Mean change scores After dressing application (post‐procedure) 1.9 (2.8); N = 20 |

Mean change scores After dressing application (post‐procedure) 3.0 (2.8); N = 21 |

P = 0.23 |

| Outcome: Adverse effects related to engagement with VR | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Visual Analogue Scale (scale range 0 to 10; 0 = no sick tummy (i.e., nausea), 10 = sick tummy as bad as it could possibly be) |

Mean change scores Nausea dressing removal (during procedure) ‐0.7 (1.1); N = 20 Nausea dressing application (after procedure) ‐0.3 (1.0); N = 20 |

Mean change scores Nausea dressing removal (during procedure) ‐0.3 (1.5); N = 21 Nausea dressing application (after procedure) ‐0.5 (1.3); N = 21 |

P = 0.27 P = 0.65 |

| Outcome: Administration of rescue analgesia | ||||

| Kipping 2012 | Frequency of rescue does of Entonox prescribed after commencement of procedure | Number (%) 3 (15%); N = 20 |

Number (%) 9 (43%); N = 21 |

P = 0.05 |

N: number SD: standard deviation

Certainty of the evidence

Two review authors (VL and AM) independently rated the certainty of evidence for each outcome. We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to rank the certainty of the evidence using the GRADEprofiler Guideline Development Tool software (GRADEpro GDT 2015), and the guidelines provided in Chapter 12.2 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011).

The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

high: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of effect;

moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect;

very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty but we downgraded the evidence by one (‐1) or two (‐2) where we identified:

serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) limitation to study quality (risk of bias);

serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) inconsistency across studies;

some (‐1) or major (‐ 2) uncertainty about directness of evidence;

serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) imprecise data; and

high probability of the presence of publication bias (‐1).

We reported our judgement on the certainty of the evidence in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

'Summary of findings' table

We included three ‘Summary of findings' tables:

VR distraction compared to no distraction;

VR distraction compared to non‐VR distraction;

VR distraction compared to other VR distraction.

We used the methods described in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook (Schunemann 2011) to prepare the ‘Summary of findings’ tables. For each table, we presented the results for the primary outcomes of acute pain intensity self‐report, observer‐report and behavioural measurements (observer‐report) measured during procedure and up to one hour post‐procedure and the secondary outcome adverse effects, as outlined in the section on Types of outcome measures. As meta‐analysis was not possible in this review, we presented results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table format. We used the GRADE system to judge the certainty of the evidence using GRADEprofiler software (GRADEpro GDT 2015).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to conduct the following subgroup analyses for the primary outcome:

(i) younger (0 to 9 years) versus older (10 to 18 years) aged children;

(ii) immersive versus non‐immersive VR interventions.

However, we did not do so because of a limited number of heterogeneous small trials for each intervention type and the fact that data were not reported separately for different ages. In future updates of this review, if sufficient data, we will conduct our planned subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We had planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis based on trial quality but did not do so as we did not pool data statistically. In future updates of this review, if sufficient data are available, we will perform sensitivity analysis by separating high from low quality. We define ‘high quality’ as a trial having low risk of bias for sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment and low risk of bias for loss to follow up, classified as less than 10% for primary outcome data.

We will perform a sensitivity analysis for plausible variations in estimated intra‐cluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) if unit‐of‐analysis errors arise in future included cluster‐randomised trials and the ICCs had been estimated for those studies. We will limit sensitivity analyses to primary outcomes. We will conduct a sensitivity analysis to determine the influence of validated versus non‐validated scales on the effects of intervention on outcome.

Consumer participation

The editorial process of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group included feedback on the review from one consumer referee in addition to health professionals. The first author of the review continues to engage in research in the field of children’s health care and services with particular emphasis on the voice and visibility of children themselves. These child perspectives were drawn upon in the review, alongside children’s perspectives of VR use in health care. We also obtained feedback from the consumer representative organisation Children in Hospital Ireland who recommended that for future trials it would be worth considering how children and young people are involved in the planning and design stage of the research as well as participants. Additionally, for future research it would be worth examining whether capacity/ability to understand/communicate or other aspects of a specific disability or condition would have an important influence on the effectiveness of the distraction stimulus.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

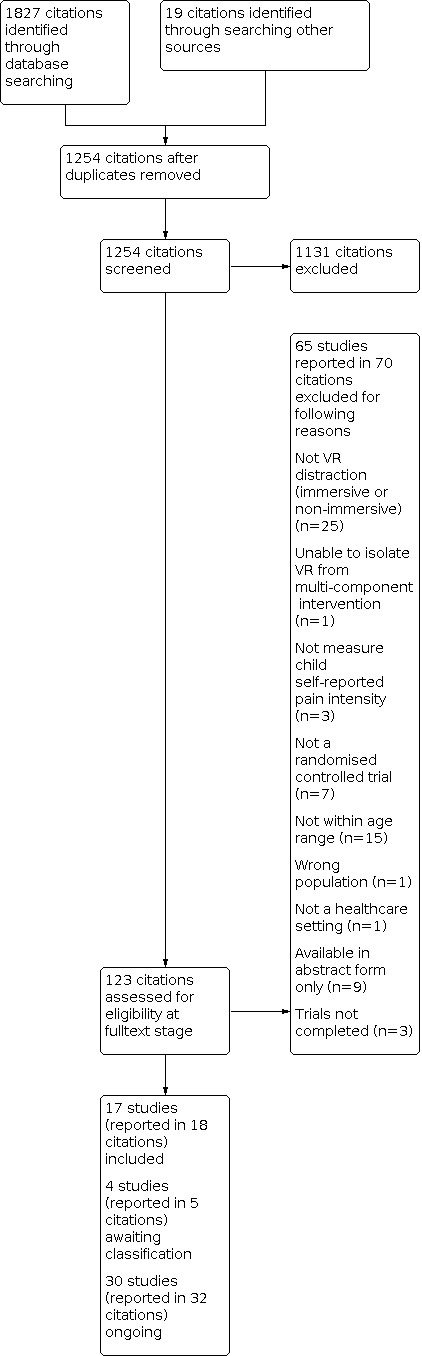

We identified 1827 citations in the database search and a further 19 citations through searching other resources. There were 1254 citations for screening after removal of duplicates. We excluded 1131 citations not meeting the review inclusion criteria on initial screening of titles and abstracts. We assessed 123 citations for eligibility at full‐text screening and excluded 70 citations (representing 65 studies) that did not meet the review selection criteria. Seventeen studies (reported in 18 citations) met the inclusion criteria and four studies (reported in five citations) are awaiting classification. Thirty studies (reported in 32 citations) are ongoing. See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

We identified 17 RCTs (reported in 18 citations). Thirteen of these used a parallel design (Chan 2019; reporting two RCTs); Chen 2019; Dumoulin 2019; Gerceker 2018; Gold 2006; Hua 2015; Jeffs 2014; Kipping 2012; Koushali 2017; Nilsson 2009; Walther‐Larsen 2019; Wolitzky 2005). Of these 13 studies, 10 had two groups (Chan 2019; reporting two RCTs); Chen 2019; Gold 2006; Hua 2015; Kipping 2012; Koushali 2017; Nilsson 2009; Walther‐Larsen 2019; Wolitzky 2005) and three had three groups (Dumoulin 2019; Gerceker 2018; Jeffs 2014). Four studies used a cross‐over (within‐subjects) design (Atzori 2018; Das 2005; Hoffman 2019; Schmitt 2011).

We contacted the authors of seven studies to obtain non‐reported mean and standard deviation data (Gold 2006; Jeffs 2014; Kipping 2012; Nilsson 2009; Schmitt 2011; Walther‐Larsen 2019; Wolitzky 2005). Three (Jeffs 2014; Nilsson 2009;Schmitt 2011) responded with data (recorded in Table 4 and Table 5), and one responded stating they no longer had access to the data (Wolitzky 2005).

Study population

The 17 included studies (see Table 6 for PICOs of included studies) had a total of 1008 participants undergoing needle‐related procedures for venepuncture, port access, intravenous placement or intravenous injection (Atzori 2018; Chan 2019; Chen 2019; Dumoulin 2019; Gerceker 2018; Gold 2006; Nilsson 2009; Walther‐Larsen 2019; Wolitzky 2005); wound dressing procedures for chronic wounds and burns (Das 2005; Hoffman 2019; Hua 2015; Jeffs 2014; Kipping 2012; Koushali 2017); and active‐assisted range‐of‐motion physical therapy sessions post burn injuries (Schmitt 2011). Individual study sample sizes ranged from nine (Das 2005) to 136 (Chen 2019) participants.

3. PICOs of included studies.

| STUDY | POPULATION | INTERVENTION | COMPARISON | OUTCOME | STUDY DESIGN |

|

Comparison 1: Virtual reality distraction compared to no distraction Primary Outcome: acute pain intensity |

|||||

| During the procedure: self‐report | |||||

| Nilsson 2009 | 5 to 18 years Cancer Venous puncture or venous port device access procedure |

Non‐immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Colour Analogue Scale (0 to 10; no pain to most pain) |

Parallel group design |

| During the procedure: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) | |||||

| Nilsson 2009 | 5 to 18 years Cancer Venous puncture or subcutaneous venous port device access procedure |

Non‐immersive VR distraction | No distraction | FLACC (nurse‐reported) (total score maximum of 10; higher score indicates more pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Wolitzky 2005 | 7 to 14 years Cancer Port access procedure |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | CHEOPS (researcher‐reported) (minimun score 4 = no pain and maximun score 13 = worst pain) | Parallel group design |

| Post‐procedure: self‐report | |||||

| Atzori 2018 | 7 to 17 years Onco‐haematological disease Venipuncture for IV placement during chemotherapy, transfusions, MRI or blood analysis |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Visual Analogue Scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) |

Within‐subject design |

| Chen 2019 | 7 to 12 years Intravenous injections |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Wong Baker faces rating scale (0 to 10; 0 no pain, 10 excruciating pain |

Parallel group design |

| Das 2005 | 5 to 16 years Acute burn injuries Wound dressing change |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Modified self‐report Faces pain (scale 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) | Within‐subject design |

| Gerceker 2018 | 7 to 12 years Phlebotomy |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Wong Baker Faces pain scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Gold 2006 | 8 to 12 years IV placement for MRI/CT scan |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Faces Pain Scale‐Revised (scale 0 to 10; no pain to very much pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Hoffman 2019 | 6 to 17 years Burn injuries Hydrotank |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Graphic Rating Scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) |

Within‐subject design |

| Jeffs 2014 | 10 to 17 years Burn injuries Wound dressing changes |

Semi‐immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (scale range 0 to 100; no pain to worst pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Koushali 2017 | 7 to 12 years Burn injuries Wound dressing changes |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Wong Baker Faces pain scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Nilsson 2009 | 5 to 18 years Cancer Venous punctures or subcutaneous venous port device access |

Non‐immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Colour Analogue Scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to most pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Schmitt 2011 | 6 to 18 years Post burn injuries Active‐assistive range‐of‐motion physical therapy |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Graphic Rating Scale (scale 0 to 100; no pain to worst pain) |

Within‐subject design |

| Post‐procedure: observer‐report | |||||

| Chen 2019 | 7 to 12 years Intravenous injections |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Wong Baker faces rating scale (scale 0 to 10; 0 no pain, 10 excruciating pain) | Parallel group design |

| Gerceker 2018 | 7 to 12 years Phlebotomy |

Immersive VR distraction | No distraction | Visual Analogue Scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to worst pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Post‐procedure: behavioural measurement (observer‐report) | |||||

| Nilsson 2009 | 5 to 18 years Cancer Venous punctures or subcutaneous venous port device access |

Non‐immersive VR distraction | No distraction | FLACC (nurse‐reported) (total score maximum of 10; higher score indicates more pain) |

Parallel group design |

|

Comparison 2: Virtual reality distraction compared to non‐VR distraction Primary Outcome: acute pain intensity |

|||||

| During the procedure: self‐report | |||||

| Hua 2015 | 4 to 16 years Chronic lower limb wounds Wound dressing changes |

Immersive VR distraction | Non‐VR distraction Toys, television, books, parental comforting |

Wong‐Baker faces pain scale (scale 0 to 5; no pain to worst pain) |

Parallel group design |

| Kipping 2012 | 11 to 17 years Burn injuries Wound dressing changes |

Immersive VR distraction | Non‐VR distraction Television, stories, music or caregivers and child preference for no distraction |

Visual Analogue Scale (scale 0 to 10; no pain to as painful as it could possibly be) |

Parallel group design |

| During the procedure: observer‐report | |||||

| Hua 2015 | 4 to 16 years Chronic lower limb wounds Wound dressing changes |