Abstract

Background

Work disability such as sickness absence is common in people with depression.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing work disability in employees with depressive disorders.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO until April 4th 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs of work‐directed and clinical interventions for depressed people that included sickness absence days or being off work as an outcome. We also analysed the effects on depression and work functioning.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted the data and rated the certainty of the evidence using GRADE. We used standardised mean differences (SMDs) or risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to pool study results in studies we judged to be sufficiently similar.

Main results

In this update, we added 23 new studies. In total, we included 45 studies with 88 study arms, involving 12,109 participants with either a major depressive disorder or a high level of depressive symptoms.

Risk of bias

The most common types of bias risk were detection bias (27 studies) and attrition bias (22 studies), both for the outcome of sickness absence.

Work‐directed interventions

Work‐directed interventionscombined with clinical interventions

A combination of a work‐directed intervention and a clinical intervention probably reduces sickness absence days within the first year of follow‐up (SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.12; 9 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence). This translates back to 0.5 fewer (95% CI ‐0.7 to ‐0.2) sick leave days in the past two weeks or 25 fewer days during one year (95% CI ‐37.5 to ‐11.8). The intervention does not lead to fewer persons being off work beyond one year follow‐up (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.83; 2 studies, high‐certainty evidence). The intervention may reduce depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.49 to ‐0.01; 8 studies, low‐certainty evidence) and probably has a small effect on work functioning (SMD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.42 to 0.06; 5 studies, moderate‐certainty evidence) within the first year of follow‐up.

Stand alone work‐directed interventions

A specific work‐directed intervention alone may increase the number of sickness absence days compared with work‐directed care as usual (SMD 0.39, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.74; 2 studies, low‐certainty evidence) but probably does not lead to more people being off work within the first year of follow‐up (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.11; 1 study, moderate‐certainty evidence) or beyond (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.22; 2 studies, moderate‐certainty evidence). There is probably no effect on depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.10, 95% ‐0.30 CI to 0.10; 4 studies, moderate‐certainty evidence) within the first year of follow‐up and there may be no effect on depressive symptoms beyond that time (SMD 0.18, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.49; 1 study, low‐certainty evidence). The intervention may also not lead to better work functioning (SMD ‐0.32, 95% CI ‐0.90 to 0.26; 1 study, low‐certainty evidence) within the first year of follow‐up.

Psychological interventions

A psychological intervention, either face‐to‐face, or an E‐mental health intervention, with or without professional guidance, may reduce the number of sickness absence days, compared with care as usual (SMD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.28 to ‐0.03; 9 studies, low‐certainty evidence). It may also reduce depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.45 to ‐0.15, 8 studies, low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain whether these psychological interventions improve work ability (SMD ‐0.15 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.57; 1 study; very low‐certainty evidence).

Psychological interventioncombined with antidepressant medication

Two studies compared the effect of a psychological intervention combined with antidepressants to antidepressants alone. One study combined psychodynamic therapy with tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) medication and another combined telephone‐administered cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). We are uncertain if this intervention reduces the number of sickness absence days (SMD ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 0.24; 2 studies, very low‐certainty evidence) but found that there may be no effect on depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐0.50 to 0.12; 2 studies, low‐certainty evidence).

Antidepressant medication only

Three studies compared the effectiveness of SSRI to selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) medication on reducing sickness absence and yielded highly inconsistent results.

Improved care

Overall, interventions to improve care did not lead to fewer sickness absence days, compared to care as usual (SMD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.06; 7 studies, moderate‐certainty evidence). However, in studies with a low risk of bias, the intervention probably leads to fewer sickness absence days in the first year of follow‐up (SMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.35 to ‐0.05; 2 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence). Improved care probably leads to fewer depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.35 to ‐0.07; 7 studies, moderate‐certainty evidence) but may possibly lead to a decrease in work‐functioning (SMD 0.5, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.66; 1 study; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Exercise

Supervised strength exercise may reduce sickness absence, compared to relaxation (SMD ‐1.11; 95% CI ‐1.68 to ‐0.54; one study, low‐certainty evidence). However, aerobic exercise probably is not more effective than relaxation or stretching (SMD ‐0.06; 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.24; 2 studies, moderate‐certainty evidence). Both studies found no differences between the two conditions in depressive symptoms.

Authors' conclusions

A combination of a work‐directed intervention and a clinical intervention probably reduces the number of sickness absence days, but at the end of one year or longer follow‐up, this does not lead to more people in the intervention group being at work. The intervention may also reduce depressive symptoms and probably increases work functioning more than care as usual. Specific work‐directed interventions may not be more effective than usual work‐directed care alone. Psychological interventions may reduce the number of sickness absence days, compared with care as usual. Interventions to improve clinical care probably lead to lower sickness absence and lower levels of depression, compared with care as usual. There was no evidence of a difference in effect on sickness absence of one antidepressant medication compared to another. Further research is needed to assess which combination of work‐directed and clinical interventions works best.

Plain language summary

What are the best ways to help people with depression go back to work?

What is depression?

Depression is a common mental health problem that can cause a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest in people, activities, and things that were once enjoyable. A person with depression may feel tearful, irritable, or tired most of the time, and may have problems with sleep, concentration, and memory.

Depression may affect people's ability to work. People with depression may be absent from work (off sick), or feel less able to cope with working.

Going back to work

Reducing depressive symptoms may help people with depression to go back to work. Treatments include medications and psychological (talking) therapies, or a combination of both. Changes at the workplace could also help, such as:

changing a person's tasks or working hours;

supporting them in a gradual return to work; or

helping them to cope better with certain work situations.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

Work can improve a person's physical and mental well‑being; it helps build confidence and self‐esteem, allows people to socialise, and provides money. We wanted to find out if workplace changes and clinical programmes could help people with depression to return to work.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at whether workplace changes and clinical programmes affected the amount of sick leave taken by people with depression. Clinical programmes included: medicines (anti‐depressants); psychological therapies; improved healthcare by doctors; and other programmes such as exercise and diet.

Search date: we included evidence published up to 4 April 2020.

What we found

We found 45 studies in 12,109 people with depression. The studies took place in Europe (34 studies), the USA (8), Australia (2) and Canada (1).

The effects of 'care as usual' were compared with those of workplace changes and clinical programmes to find out:

how many days people with depression were on sick leave

how many people with depression were off work;

people's symptoms of depression; and

how well people with depression could cope with their work.

What are the results of our review?

Our main findings within the first year of follow‐up, for workplace changes or treatments compared with usual care, are listed below.

Workplace changes combined with a clinical programme:

probably reduce the number of days on sick leave (on average, by 25 days for each person over one year; 9 studies; 1292 participants);

do not reduce the number of people off work (2 studies; 1025 participants);

may reduce symptoms of depression (8 studies; 1091 participants); and

may improve ability to cope with work (5 studies; 926 participants).

Workplace changes alone:

may increase the number of days on sick leave (2 studies, 130 participants);

probably do not lead to more people off work (1 study; 226 participants);

probably do not affect symptoms of depression (4 studies; 390 participants); and

may not improve ability to cope with work (1 study; 48 participants).

Improved healthcare alone:

probably reduces the number of days on sick leave, by 20 days (in two, well‐conducted studies in 692 participants, although not in all 7 studies, in 1912 participants);

probably reduces symptoms of depression (7 studies; 1808 participants); and

may reduce ability to cope with work (1 study; 604 participants).

Psychological therapies alone:

may reduce the number of days off work, by 15 days (9 studies; 1649 participants); and

may reduce symptoms of depression (8 studies; 1255 participants).

We are uncertain if psychological therapies alone affect people's ability to cope with work (1 study; 58 participants).

How reliable are these results?

Our confidence in these results is mostly moderate to low. Some findings are based on small numbers of studies, in small numbers of participants. We also found limitations in the ways some studies were designed, conducted and reported.

Key messages

Combining workplace changes with a clinical programme probably helps people with depression to return to work more quickly and to take fewer days off sick. We need more evidence to assess which combination of workplace changes and clinical programmes works best.

Improved healthcare probably also helps people with depression to take fewer days off sick.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is a major public health problem, with 298 million cases of major depressive disorders at any time point in 2010 (Ferrari 2013). The worldwide point prevalence of depressive disorder was 4.4% in both 2005 and 2010 (Ferrari 2013). Symptoms of depressive disorder include the presence of one or two core symptoms of low mood and loss of interest, coupled with other symptoms such as feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness, sleep disturbance, weight change, fatigue, impaired concentration, agitation or slowing down of movement and thought, and suicidal ideation (APA 2013). Depressive disorders can be classified along a continuum by the levels of symptom severity, number of mental or physical symptoms, and duration. Corresponding diagnostic categories range from persistent depression (dysthymia) and subclinical states (minor depressive disorder) to major depressive disorder (APA 1994; APA 2013).

Besides the serious consequences in terms of individual suffering, depression has a large impact on social functioning and the ability of patients to work (Evans‐Lacko 2016; Hirschfeld 2000; Lerner 2008). In a population of US workers, the 12‐month prevalence of major depressive disorder was found to be 6% and was associated with 27.2 lost workdays per ill worker per year (Kessler 2006). The economic burden of depressed individuals in the US was US dollars (USD) 210.5 billion in 2010, of which 50% were attributable to workplace costs (Greenberg 2015). The high prevalence of depressive disorders, combined with the impact on work disability, has extensive societal consequences. In 1990, major depressive disorders were the 15th leading contributor to the global burden of disease in terms of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs), which is the sum of years of productive life lost due to premature mortality and the years of productive life lost due to disability. Data from the Global Burden of Disease study showed that depressive disorders were ranked the 11th leading contributor (Murray 2012).

While working is important from a societal point of view, work is also an important aspect of the quality of life of individuals (Bowling 1995). Work provides income, structure, and social interactions. One salient consequence of depression is absenteeism, but depression can also affect the at‐work productivity for workers (Lerner 2008). Depressed workers experience specific limitations in their ability to function at work. These limitations include performing mental and interpersonal tasks (Adler 2006; Burton 2004). The quality of work performance can also be affected, as was shown in studies focusing on errors and safety issues (Haslam 2005; Suzuki 2004). Depressed workers may need to make an extra effort to be productive during their work (Dewa 2000), which may lead to spill‐over effects of fatigue after work.

Description of the intervention

Work disability of depressed workers can be targeted by interventions. First of all, work‐directed interventions aim to ameliorate the consequences of the depressive disorder on the ability to work. These types of interventions either target the work itself, by modifying the job task, or (temporarily) reduce the working hours. Work‐directed interventions can also support the worker in dealing with the consequences of their depression at the workplace.

Second, clinical interventions aimed at reducing depression symptoms may improve work ability (Hees 2013b). Current clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of major depressive disorder recommend pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or a combination of both (APA 2010; NICE 2010). Pharmacologic treatment for major depressive disorder includes antidepressant medication such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAO inhibitors), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). With regard to psychotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy in particular are considered effective treatment options (NICE 2010). Exercise has been increasingly used as an alternative to pharmacological or psychotherapeutic interventions (Cooney 2013).

How the intervention might work

Work‐directed interventions are deemed to reduce work disability by creating a work environment better suited for a depressed worker, such as modifying work tasks or working hours. Moreover, the worker can be supported in dealing with the depression at work by a gradual return to work program or by enhancing skills to cope with work situations (Lagerveld 2012). Clinical interventions may reduce work disability by reducing depressive symptoms, thereby eliminating the obstacles to working.

Why it is important to do this review

Considering the impact of depressive disorders on the occupational health of many affected workers, it is vital to know what types of interventions are effective in improving occupational health. In the first version of this review, in 2008, we concluded that there was an urgent need to evaluate interventions that address work issues in future research. Since then, several such studies have been published underpinning the need for an update of the review.

Objectives

The goal of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing sickness absence in employees with depressive disorders.

We considered the effectiveness of two types of interventions:

work‐directed interventions, i.e. addressing the work or the work‐worker interface as part of the clinical treatment or as a stand‐alone intervention; and

clinical interventions, i.e. treatment of depressive disorder without a focus on work.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs, in this review. We did not use any language restrictions.

Types of participants

Patient characteristics and setting

The population was limited to adult (i.e. more than 17 years old) workers (employees or self‐employed). We included participants from occupational health settings, primary care, or outpatient care settings. We based the selection of the studies on the primary outcome only. We still included studies if less than 50% of the participants were not employed.

Diagnosis

We defined depressive disorder as a main diagnosis fulfilling the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM‐IV) (APA 1994; APA 2013), the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Spitzer 1979), or the International Classification of Disease (ICD‐10) (WHO 1992) for one of the following disorders: dysthymic disorder, minor depressive disorder, or major depressive disorder. We also included studies that defined depressive disorder as a level of depressive symptoms assessed by validated self‐report instruments published in peer‐reviewed journals. An example is the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1987); or clinician‐rated instruments such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton 1967) or the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979).

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies involving workers with a primary diagnosis of a common mental disorder other than a depressive disorder. We did not exclude workers with a co‐morbidity from other common mental disorders (such as anxiety disorders), but we did exclude workers with bipolar disorders or depressive disorders with psychotic features.

Types of interventions

We included all interventions aimed at reducing work disability. Naming and classifying interventions that aim to improve return to work is difficult. Health‐care interventions aiming to enhance return to work are mainly based on two mechanisms. One is improving conditions related to work, such as helping workers with depressive symptoms to overcome barriers that prevent them from working such as reducing work hours, changing tasks, light duty, graded work exposure addressing causes of depression at work such as a conflict, or supporting the worker in coping with the consequences of their depression in the workplace. We called these types of interventions ‘work‐directed interventions’ and we did not use any subcategories of these interventions. The other mechanism is through improvement of depressive symptoms as is usual in treatment situations, assuming that the symptoms are the main barrier for not being at work. We called these interventions ‘clinical interventions.' For clinical interventions we made distinctions among the following treatment modalities: psychological or psychiatric treatment, antidepressants, a combination of these two, and other interventions such as improved care, exercise and diet.

We compared work‐directed interventions, clinical interventions, and a combination of both types against any other intervention, no intervention or care as usual.

Types of outcome measures

In this review, we operationalised reduction in work disability as a reduction in sickness absence and as enhancement in work functioning.

Primary outcomes

The main outcome measure in this review was sickness absence, either measured as sickness absence days during the follow‐up period or employment status after a period of time, categorised as being 'off work' or 'at work.' Sickness absence data could be extracted from the employee attendance records, the files of a compensation board, or it could be self‐reported.

Secondary outcomes

When available, we included the following secondary outcomes from the included studies.

Depression (either dichotomously or continuously measured).

Work functioning (Nieuwenhuijsen 2010). Examples of work functioning measures are the Endicott Work Productivity Scale (EWPS) (Endicott 1997), the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Sheehan 1996) and the Work Role Functioning Questionnaire (WRFQ) (Abma 2012). We only included instruments that separately measured work functioning (instead of work and other activities combined). The outcome 'work ability' (Ilmarinen 2005) was also considered as a work functioning outcome.

We did not include other outcomes such as employee satisfaction, general social functioning (not work‐specific), or quality of life scales.

We considered the effects measured with all the above instruments on the following time‐scales:

short‐term, up to two months;

medium‐term, over two months to one year; and

long‐term, over one year.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted the original search strategy for the first version of this review in 2006, using no limits on publication date (Appendix 1). We updated the search for the 2014 update and used this search strategy again for the 2020 update (Appendix 2). For this update, we searched the following electronic databases: CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and CINAHL up to the 4 April 2020. We used three types of terms: depression‐related words combined with work‐related words and database‐specific methodological filter terms. We adapted the search terms for PsycINFO, Embase, and CINAHL from the MEDLINE search to fit the specific requirements of those databases. For CENTRAL, we replaced the methodological filter by a filter to identify trials.

We based the selected work‐related search terms on previous studies. Work* and occupation* are sensitive single terms used to locate occupational health studies, as advocated by Verbeek (Verbeek 2005). Furthermore, we selected database‐specific terms relevant to our objective from a study testing which work‐related search terms are best suited for literature searching on chronic disease (rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, hearing problems, and depression) and work (Haafkens 2006).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all articles that we retrieved as full papers and of all retrieved systematic and narrative reviews in order to identify further potentially eligible studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of review authors decided if a study did not fulfil the criteria for selection, and we excluded the study at that point. We excluded studies in this phase only if the study did not include participants with depressive disorders or it was not a controlled intervention study. When it was not clear whether sickness absence was measured, we retrieved the full article before deciding upon exclusion. We then examined the full text publications of the remaining studies in order to decide which studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria. We documented the reasons for exclusion at that stage. The two review authors discussed any disagreement about the inclusion of studies until they reached consensus. If they could not resolve their difference of opinion, they consulted a third review author (JV). All articles published in languages other than English were translated or assessed for inclusion by a native speaker.

Data extraction and management

We constructed a data extraction form that enabled the review authors to extract the data from the included studies. For each study, one review author filled out the forms; this form was checked by a second review author (AN, AV, BF, CF, HH, KN, and UB participated in data extraction). Review authors solved differences of opinion by discussion. When only a proportion of the study population was workers, we extracted the data for that subgroup from the article. When these data were not reported, we asked the original study authors to provide the data for this subgroup. We used the same procedure for studies where only a proportion of the study population was depressed.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Pairs of review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. We used the following items to assess risk of bias in the included studies: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias). We evaluated risk associated with incomplete outcome data or with blinding of outcome assessments separately for sickness absence, depressive symptoms and where applicable also for work functioning. As the latter outcome was not often used, we did not report the risk of bias for work functioning separately in the risk of bias tables. We assessed the risk of bias in RCTs and cluster‐RCTs by using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011).

With regard to the risk of attrition bias, we calculated the percentage lost to follow up taking the number randomised as the starting point and the number analyzed at the latest follow‐up measurement as the endpoint. We assigned a high risk of attrition bias to studies with a percentage of participants lost to follow up of more than 20%, and a low risk for studies with less than 10% lost to follow. The risk of attrition bias for studies with 10% to 20% lost to follow up depended on whether the analyses of results accounted for attrition sufficiently.

We rated each potential source of bias as ‘high risk’ of bias, ‘low risk’ of bias, or ‘unclear risk’ of bias in the ‘Risk of bias’ table. Next, we constructed a ‘Risk of bias' summary figure together with an overview ‘Risk of bias' graph as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a researcher, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Measures of treatment effect

We plotted the results of each trial as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes. For each timescale (short‐term, medium‐term, and long‐term), we selected the last available observation within this period for the meta‐analysis. For the primary outcome measure, that is sickness absence days, we transformed the number of days or hours worked during the follow up into days of sickness absence. To do so, we extracted the hours or days worked from the mean number of hours a full‐time employee would work in that specific country. When transforming the data from days worked to days not worked, the SDs did not need to be transformed. When transforming the data from hours to days, we divided both the means and SDs by eight. Studies used different time spans during which they measured the number of sickness absence days. Therefore, for sickness absence days we used the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) between the intervention and control groups as the summary effect measure. In order to aid interpretability of these SMDs, we also present the translation of the SMD in terms of the two most commonly used outcome measures; sickness absence days over a two‐week period and over a one‐year period. To this end, we multiplied the SMD by the median of the SDs of the intervention groups using these outcomes.

For the secondary outcome measures, we also used SMDs because it is likely that these outcomes were measured with different instruments. We chose to treat ordinal variables using a scale of more than five categories as continuous variables (it should be noted that this choice was based on arbitrary criteria). We dichotomised scales with fewer than five categories. For dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs.

For depression data, where studies presented both dichotomous and continuous data, we preferred the continuous outcome measures since the majority of the studies presented these.

Unit of analysis issues

For studies that employed a cluster‐randomised design and did not consider the design effect in the analyses, we planned to calculate the design effect by following the methods presented in Donner 2002 based on a fairly large assumed intra‐cluster correlation of 0.10. However, the cluster‐RCTs included in the review reported negligible intra‐cluster correlations. Therefore, we did not adjust the measures of effect presented by the authors.

Dealing with missing data

If the SDs (continuous data) or numbers of outcomes for each group (dichotomous data) were not presented in the publication, we contacted the authors with a request to provide these data. Whenever authors were unable or unwilling to provide this information, we calculated SDs from P values and CIs following the instructions of the Handbook (Higgins 2011).

We sought additional information regarding study details, statistical data, or both, from the authors of 20 studies. We received information from 15 authors. Ten of the authors provided statistical data that had not been published in their articles, which enabled us to include nine of these studies in the meta‐analyses. In the case of two studies the correspondence led to the exclusion of the study because essential information on the primary outcome measure could not be provided (Simon 2000; Stant 2009). Whenever essential information concerning the risk of bias could not be obtained within four weeks of contacting the authors, we listed the corresponding details as 'unclear.'

Assessment of heterogeneity

For clinical heterogeneity, we had the following considerations for similarity or heterogeneity between studies.

We considered interventions to have a similar mechanism and effect in all types of participants.

We considered the effects and mechanisms for all work‐directed interventions as similar.

The three subcategories of clinical interventions, anti‐depressants, psychological interventions or exercise were considered as having different effects and mechanisms.

All various sickness absence outcomes and all various depression outcomes were considered similar.

Follow‐up times of up to two month (short‐term), from over two months to one year (medium‐term) and over one year (long‐term) were considered different.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in the meta‐analyses with the I² statistic. If we observed considerable heterogeneity (I² > 75%), we refrained from statistical pooling of the studies within that comparison. Substantial inconsistency (I² statistic) also led to downgrading of the certainty of the evidence (see Data synthesis for details).

Assessment of reporting biases

We produced funnel plots for visual inspection of possible publication bias.

Data synthesis

For each predefined comparison, we analyzed data for each outcome measure separately. Whenever interventions belonged to the same category in the comparison but two review authors (KN and JV, or KN and BF) judged them dissimilar, we defined subcategories for these types of intervention. We conducted meta‐analysis if two review authors (KN and BF) judged a group of trials sufficiently homogeneous in terms of participants, interventions, and outcomes to provide a meaningful summary. In such cases, we calculated pooled SMDs for the predefined outcome measures using the Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014) with a random‐effects model. We chose a random‐effects model as we expected statistical heterogeneity to occur as a result of the clinical and methodological heterogeneity in research on sickness absence. For three‐armed trials contributing evidence to two different comparisons, we divided the number of participants of the arm used in both comparisons by two.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered that there could be difference in the way psychological treatment was administered and we compared studies with a personal therapist or in‐person therapy with web‐based or telephone‐based studies without personal guidance of a therapist. In addition, we planned to analyze if studies with mostly women (> 80%) had different effects from studies with mostly men (> 80%). However, we did not include a sufficient number of studies with such an uneven gender‐distribution to allow for this analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses by excluding:

studies with a high risk of bias (defined as at least three of the 'Risk of bias' items were judged to present a low risk of bias: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants/personnel; blinding of outcome assessment;

studies with skewed data; and

studies in which workers were a small subgroup of the study population.

However, the small numbers of studies in each comparison only allowed for the sensitivity analyses of risk of bias and then only in the comparisons with the highest number of studies.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of a body of evidence regarding the primary outcome category of the comparisons addressed in the review. At the start of the GRADE assessment process, we assumed high certainty for all studies and we downgraded the certainty of the evidence for each comparison by one to three levels depending on the seriousness of the violations in each domain.

To assess the risk of bias for a comparison, we considered the 'Risk of bias' tables for each study in that comparison. We saw items related to selection bias, detection bias, and attrition bias as prerequisites for high certainty. We only considered studies with low risks on these items to have a low risk of bias. For each comparison we considered the risk of bias serious (‐1) if a majority of the evidence in the studies included in the meta‐analysis (in terms of weights) were of low quality. We applied a ‐2 downgrade in cases where the majority of the studies did not have adequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment. For consistency, we considered an I2 value of 50% to 75% to indicate substantial inconsistency, which lead us to downgrade (‐1). If the I2 value exceeded 75%, we refrained from pooling the results and we analyzed the results for each study separately. Indirectness of the evidence was not an issue in our review as all comparisons in the included studies directly addressed the comparison. For imprecision of results, we judged serious imprecision leading to downgrading (‐1) if a comparison either included a number of fewer than 400 participants or a wide CI around the effect estimate. For a non‐significant effect, we considered a CI to be wide if it included an SMD of both 0 and a moderate effect size (SMD > 0.5 or < ‐0.5). For I a significant effect, we considered a CI to be wide if it included both a small and large effect size (SMD small = ‐0.2 or 0.2; SMD large = 0.8 or ‐0.8). If in addition to a wide CI, the comparison included one study only, we downgraded with two levels (‐2).

The resulting interpretation of the certainty of the level of evidence per comparison was as follows.

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect

Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different

Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect

Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect

We created ‘Summary of Findings’ (SOF) tables with GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2008) for the main comparisons.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

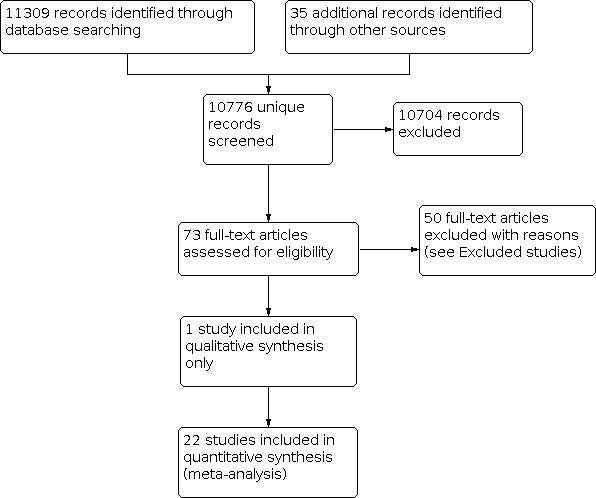

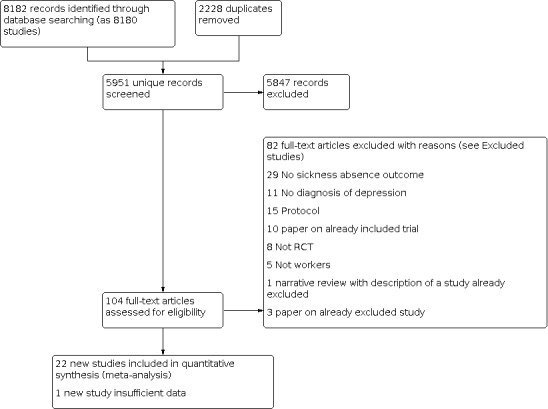

Figure 1 displays a PRISMA study flow chart of the inclusion process up to 2014. Figure 2 displays the flow chart of the 2020 update. The electronic searches between 2014 and 2020 resulted in 5951 new hits. We assessed the titles and abstracts for eligibility. This resulted in the full text assessment of 104 publications. We excluded 82 studies after further scrutiny (see Characteristics of excluded studies). This resulted in the inclusion of 22 new studies additional to the 23 studies already in the review. In addition, we identified five ongoing studies in the first and none in the 2020 update (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

1.

PRISMA Study flow diagram of the study selection process until 2014.

2.

PRISMA Study flow diagram of the study selection process 2014‐2020.

Included studies

We included 45 studies in the review (see Characteristics of included studies). Four of these studies included three study arms (Kaldo 2018; Kendrick 2005; Knekt 2013; Krogh 2009) and one had four study arms (Finnes 2017). In our analyses we combined two interventions groups of the Kendrick 2005 and two of the Knekt 2013 study. Therefore, in the end we analyzed a total of 93 study arms in this review.

Designs

Of the included studies, 40 were RCTs and five were cluster‐RCTs (Noordik 2013; Rost 2004; Schoenbaum 2001; Björkelund 2018; Volker 2015). Intra‐class correlations for four of these studies were reported to be negligible and therefore we did not adjust the data. However the Björkelund 2018 study did not report the ICC and we therefore adjusted undertook an unplanned sensitivity analysis (see effects of interventions).

Sample sizes

The total number of participants in the included studies was 13,669. The number of participants included in the analysis was lower (12,109) as we reported on the subgroup of 'employed and depressed participants only' in cases where studies included other subgroups as well. The number of participants in the smallest study (sub)group was lower than 50 in 20 study arms, between 50 and 99 in 22 study arms, between 100 and 199 in 23 study arms, and 200 or more in 18 study arms.

Time period, setting and participants

Three studies were published before 2000, 15 between 2000 and 2010, and 27 after 2010. Eight studies were conducted in the US, 34 were conducted in Europe, one in Canada and two in Australia. Participants were recruited in primary care settings (13 studies), outpatient settings (15 studies), workplace settings (five studies), occupational health care (five studies), through health insurance companies (two), a managed care setting (one study), an unemployment centre (one study), a community mental health centre (one study), a hospital (one study), and through an academic institution (one study). In 32 studies, all participants had a depressive disorder. In 13 studies (Bee 2010; Finnes 2017; Hellstrom 2017; Kendrick 2005; Knapstad 2020; Knekt 2013; McCrone 2004; Meuldijk 2015; Noordik 2013; Reme 2015; Reme 2019; Volker 2015; Wormgoor 2020) depressed patients constituted a subgroup of the study participants.

Interventions

Work‐directed interventions, or work‐directed interventions combined with a clinical intervention

We identified 17 work‐directed interventions in 14 studies. Thirteen interventions, reported in 11 studies, were a combination of a work‐directed and a clinical intervention (Finnes 2017; Geraedts 2014; Hees 2013; Kaldo 2018; Lerner 2012; Lerner 2015; Lerner 2020; Reme 2015; Schene 2006; Vlasveld 2013; Volker 2015). Four interventions were work‐directed only (Finnes 2017; Hellstrom 2017; Noordik 2013; Reme 2019).

All four work‐directed interventions included multiple meetings with intervention providers, three specified meetings in the Finnes 2017 study and multiple meetings in the other three. In Noordik 2013, the number depended on the time it took to return to work and the Hellstrom 2017 and Reme 2019 studies provided unlimited support, depending on the individual need of the participants.

The work‐directed interventions in Finnes 2017, Hellstrom 2017 and Noordik 2013 all included contact of the intervention provider with the supervisor of the worker. In the Finnes 2017 study, however, this was most structured as it included a stepwise method with separate worker and supervisor interviews and one convergence meeting with both.

The Noordik 2013 study compared an exposure‐based return to work intervention (RTW‐E) conducted by occupational physicians (OPs), gradually exposing the participants to more demanding work situations, with regular support by the OP. The RTW‐E program provided workers with several homework assignments aimed at preparing, executing, and evaluating an exposure‐based RTW plan. In the Finnes 2017 study, the work‐directed Intervention aimed to facilitate dialogue between the participant and the workplace through a series of steps involving the participant and the nearest supervisor, resulting in a return‐to‐work plan. Providers were either clinical or behavioural psychologists, or psychiatric nurses. In the Hellstrom 2017 study, the intervention followed the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model. Workers could be out of a job for a longer time (up to three years) and return to work in those workers included return to a new job. The intervention included career counselling and contact with employers to help participants obtain jobs and keep them. Providers were mentors (nurses, social workers or occupational therapists) and career counsellors. In the Reme 2019 study, the intervention also followed the IPS model and included personalised benefits counselling, rapid job search (starting within one month), systematic job development, and time unlimited and individualized support. Providers were employment specialists.

Three of the work‐directed interventions compared that intervention with other work‐directed interventions; in the Hellstrom 2017 study, this included services as offered by the job centres in Denmark, for instance, courses, company internship programmes, wage subsidy jobs, skill development and guidance, mentor support or gradual return to employment. The work‐directed 'care as usual' by OPs in the Noordik 2013 study was based on a national guideline. Care as usual included both work modification and support. In the Reme 2019 study, the work‐directed 'care as usual' involved a referral to either work with assistance by a personal facilitator, and included finding suitable work, negotiating wage and employment conditions, modified duties, and follow‐up at the work place or to a traineeship in a sheltered business. The work‐directed intervention in the Finnes 2017 study was compared to care as usual from a medical doctor.

Of the 13 interventions that combined a work‐directed intervention with a clinical intervention, the main mode of intervention delivery was face‐to‐face meetings in five studies with seven interventions (Finnes 2017; Hees 2013; Reme 2015; Schene 2006; Vlasveld 2013); online in three studies (Geraedts 2014; Kaldo 2018; Volker 2015); and by telephone in three studies (Lerner 2012; Lerner 2015; Lerner 2020). The number of meetings in interventions that included face‐to‐face or telephone meetings ranged from four (Lerner 2012); six to 12 (Vlasveld 2013); eight (Lerner 2015; Lerner 2020); 37 (Hees 2013) to 44 meetings in the Schene 2006 study.

The combined work‐directed and clinical interventions most often based the clinical interventions on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles (Kaldo 2018; Lerner 2012; Lerner 2015; Lerner 2020; Reme 2015), on the principles of problem‐solving therapy (PST) (Vlasveld 2013) or a combination of CBT and PST (Geraedts 2014; Volker 2015). The clinical part of the Hees 2013 and Schene 2006 studies included psychiatric clinical management according to American Psychiatric Association guidance, which also included antidepressants. The Vlasveld 2013 study also included antidepressant treatment with PST. Finnes 2017 was the only study that used acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) as the basis for their clinical intervention. The work‐directed interventions ranged from an elaborated and highly structured program provided by occupational therapists in the Hees 2013 and Schene 2006 studies, through facilitating dialogue between the participant and the workplace in three meetings in the Finnes 2017 study, and work‐directed care modelled after Individual Placement and Support (IPS) in the Reme 2015 study.

Providers of the clinical part of the interventions were psychiatric residents in the Hees 2013 and Schene 2006 studies, clinical psychologists in the Finnes 2017 and Reme 2015 studies, counsellors in the Lerner 2012 and Lerner 2015 studies, occupational physicians in the Vlasveld 2013 study, The web‐based clinical interventions included support from a psychology student in the Geraedts 2014 study, support from an occupational physician in the Volker 2015 study, and support from clinical psychologists or supervised psychology students in the Kaldo 2018 study.

The work‐directed part of the intervention was delivered by the same providers in the Geraedts 2014, Kaldo 2018, Lerner 2012, Lerner 2015, Vlasveld 2013, and Volker 2015 studies. The work‐directed part of the intervention was delivered by another provider in the Finnes 2017 study (clinical psychologist, behavioural therapist, or psychiatric nurse), the Hees 2013 and Schene 2006 studies (occupational therapist), the Lerner 2020 study (doctoral‐level psychologist) and the Reme 2015 study (employment specialist).

Two studies combining a work‐directed intervention with a clinical intervention employed multiple comparisons. In the Finnes 2017 study, comparisons were 1) the work‐directed component only, 2) the clinical component only, and 3) care as usual provided by access to a medical doctor, psychologist, social worker, physical therapist, or nurse). Kaldo 2018 used both exercise (aerobic) and care as usual (primary care standard treatment for depression determined by the patient’s general practitioner) as comparisons.

The Hees 2013 and Schene 2006 studies compared the work‐directed intervention combined with a clinical intervention with the clinical intervention alone, whereas the Reme 2015, Vlasveld 2013, and Volker 2015 studies used the work‐directed intervention alone as the comparison.

Three studies compared the work‐directed intervention combined with a clinical intervention to care as usual which could include various providers, but these were not specified (Lerner 2012; Lerner 2015; Geraedts 2014) or included a team of various providers (Lerner 2020; psychologists, nurses and social workers).

Clinical interventions

We included 31 studies reporting the effects of clinical interventions for depressed workers.

Psychological interventions

Twelve studies assessed the effect of a psychological intervention (Bee 2010; Beiwinkel 2017; Birney 2016; Eriksson 2017; Finnes 2017; Hollinghurst 2010; Kendrick 2005; Knekt 2013; Mackenzie 2014; McCrone 2004; Phillips 2014; Wormgoor 2020). Four of these studies looked at an intervention that was delivered face‐to‐face (Finnes 2017; Kendrick 2005; Knekt 2013; Wormgoor 2020). One intervention was delivered by telephone only (Bee 2010); one offered telephone guidance alongside an online intervention (Eriksson 2017); and three studied an online intervention and provided guidance through text messages with a provider (Beiwinkel 2017; Hollinghurst 2010; Mackenzie 2014). A further three were online programmes delivered without guidance (Birney 2016; McCrone 2004; Phillips 2014). The intensity of these interventions varied from five or six sessions (Finnes 2017; Mackenzie 2014; Phillips 2014), eight (Kendrick 2005; McCrone 2004), ten (Hollinghurst 2010) and 12 sessions (Bee 2010; Beiwinkel 2017) to 20 sessions or more (Knekt 2013; Wormgoor 2020). In two studies, the number of sessions was not specified (Birney 2016; Eriksson 2017).

Eight of the 12 interventions were based on the principles of CBT. One was based on ACT (Finnes 2017); one was based on PST (Kendrick 2005); one was based oThank n psychodynamic therapy (Knekt 2013), and one focused on normalisation and coping (Wormgoor 2020).

Intervention providers were clinical psychologists in the ACT arm of the Finnes 2017 study. Beiwinkel 2017 and Eriksson 2017 used both psychologists and psychotherapists to provide guidance alongside the online CBT, while the psychotherapy intervention in Knekt 2013 study, and the coping‐focussed therapy in Wormgoor 2020 were delivered by psychotherapists alone. The telephone CBT was provided by mental health workers in Bee 2010 and mental health specialists provided the email guidance alongside the online CBT in the Mackenzie 2014 study. In Kendrick 2005, the intervention was delivered by community mental health nurses.

Six studies (Bee 2010; Eriksson 2017; Finnes 2017; Hollinghurst 2010; Kendrick 2005; McCrone 2004) compared their intervention with care as usual in general practice.

Three studies compared their online interventions to directing workers with text based information on depression (Beiwinkel 2017; Birney 2016; Phillips 2014). The Knekt 2013 study compared psychodynamic psychotherapy with PST and Wormgoor 2020 compared their coping focused therapy to brief psychotherapy. The online CBT in the Mackenzie 2014 study was compared with a waiting list condition.

Psychological interventions plus antidepressant medication

Two studies included interventions with a combination of psychological interventions and antidepressant medication. One study (Burnand 2002) compared the effect of psychodynamic therapy combined with TCA medication with TCA medication alone. The intervention included face‐to‐face individual sessions by a nurse combined with clomipramine for a duration of 10 weeks. The frequency of the psychotherapy sessions was not fixed. This was compared with a group receiving the same medication and who received supportive care (an individual session with empathic listening, guidance, and support). One study (Sarfati 2016) compared a combination of SSRI medication and a telephone‐administered CBT programme with medication and adherence enhancing phone calls. The CBT programme included eight 30‐minutes sessions provided by PhD‐ or Master’s degree‐level experienced therapists. In the control condition, a research coordinator provided a 10‐minute structured telephone call weekly for eight weeks, with enquiry about progress and reminders to take medication properly

Antidepressant medication

Six studies examined the effectiveness of antidepressant medication, of which one compared the antidepressant medication with a placebo condition (Agosti 1991) and the other five with another antidepressant medication (Fantino 2007; Fernandez 2005; Miller 1998; Romeo 2004; Wade 2008). Three studies compared a SSRI with SNRI medication (Fernandez 2005; Romeo 2004; Wade 2008), one study compared a SSRI with TCA (Miller 1998), one study compared two different SSRIs (Fantino 2007), and one study compared TCA or MAO inhibitors with placebo (Agosti 1991).

Improved care

Eight studies (Björkelund 2018; Knapstad 2020; Meuldijk 2015; Rost 2004; Schoenbaum 2001; Simon 1998; Wang 2007; Wikberg 2017) looked at the effects of improving care management for depressed workers rather than evaluating one specific clinical intervention.

Five studies (Björkelund 2018; Rost 2004; Schoenbaum 2001; Simon 1998; Wikberg 2017) compared enhanced primary care with primary care as usual. In these types of interventions general practitioners were enrolled in a quality improvement program and were expected to provide enhanced care including antidepressant medication and psychological interventions, according to primary care guidelines. In the Björkelund 2018 study, this included a nurse acting as a care manager to assist the general practitioner in providing care. The care manager would have one face‐to‐face meeting and five to seven follow‐up meetings by telephone. In the Wikberg 2017 study, general practitioners were taught how to use the MADRS‐S to monitor changes in depressive symptoms. Workers made four visits to the general practitioner before which the worker completed the MADRS‐S.

One study (Wang 2007) compared a structured telephone outreach and care management program with usual managed care. Workers were enrolled after screening offered to various work organisations that took part in a managed behavioural health care program. The telephone outreach systematically assessed needs for treatment, facilitated entry into in‐person treatment (both psychotherapy and antidepressant medication), monitored and supported treatment adherence, and (for those declining in‐person treatment) provided a structured psychotherapy intervention by telephone. Intervention participants declining in‐person treatment and experiencing significant depressive symptoms after two months were offered a structured eight‐session cognitive behavioural psychotherapy program.

In the Meuldijk 2015 study, concise and protocolised psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy care were provided within seven weeks and compared with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy that was provided without limitations to the number of sessions. In the Knapstad 2020 study, Prompt Mental HealthCare (PMHC) was provided as part of primary care. This meant that clients could directly contact PMHC and have access to mental health treatment (within 48 hrs).

Exercise

Three exercise interventions were included; strength training (Krogh 2009), aerobic training (Krogh 2009; Krogh 2012) or a program including either light, moderate or vigorous exercise (Kaldo 2018).

The exercise interventions were compared with relaxation (Krogh 2009; Krogh 2012) or standard treatment for depression determined by the patient’s general practitioner (Kaldo 2018).

Art

In the Blomdahl 2018 study, a protocolised art therapy was compared with care as usual, which could include acupuncture, cognitive–behavioural therapy, electroconvulsive therapy, interpersonal therapy, occupational therapy, pharmacological therapy, physiotherapy, psychodynamic therapy,and supportive therapy.

Diet

The Chatterton 2018 study assessed the effect of a dietary intervention comprising of personalised dietary advice and nutritional counselling support, including motivational interviewing, goal setting and mindful eating, from a clinical dietician in order to support optimal adherence to the recommended diet. The dietary intervention was compared with a social support control group in which trained personnel befriended participants by discussing neutral topics of interest to the participant, such as sport, news or music.

Outcomes

Studies were only selected if they reported on sickness absence. Of the 45 included studies, seven studies (Agosti 1991; Bee 2010; Krogh 2012; Miller 1998; Schene 2006; Wang 2007; Lerner 2020) reported days or hours worked instead of days of sickness absence. These measures were transformed into sickness absence days as described in the 'Methods' section (see Measures of treatment effect).

We were able to collect data on depression for all but five of the included studies (Agosti 1991; Kaldo 2018; Mackenzie 2014; Meuldijk 2015; Volker 2015). Of all studies reporting on depression, one study (Schoenbaum 2001) presented only dichotomous depression data while all others presented continuous data.

Nine studies (Agosti 1991; Burnand 2002; Hees 2013; Lerner 2012; Lerner 2020; Miller 1998; Rost 2004; Wade 2008; Wang 2007) reported on work functioning using a (sub)scale that separately measured work instead of work and other activities combined. The SD's around the mean scores for work functioning could not be retrieved in the Rost 2004 study, therefore this outcome was not included in the meta‐analysis.

Two studies reported on work ability (Finnes 2017; Kaldo 2018) another study reported on both work functioning and work ability (Sarfati 2016).

Ten studies (Geraedts 2014; Hellstrom 2017; Kaldo 2018; Knapstad 2020; Krogh 2012; Reme 2015; Reme 2019; Schoenbaum 2001; Wade 2008; Wormgoor 2020) reported on 'not working' or 'working' or sickness absence status at the end of follow up. We recalculated all outcomes so that they represent the proportion of workers off work at follow‐up. The Schoenbaum 2001 study presented only % of those employed at baseline, and these baseline numbers for the total group. The actual numbers of participants at work was calculated bases on the assumption of an equal distribution of baseline employment between study arms. The Blomdahl 2018 reported on a % of workers with sickness absence during follow‐up.

Follow up

(a) Short‐term

Four of the included studies had the last outcome measurement within one month Agosti 1991; Birney 2016; Fantino 2007; Fernandez 2005).

(b) Medium‐term

In 32 studies, the last follow‐up measurement was between one month and a year after inclusion. Five studies had the last follow‐up measurement later than one year but provided data on earlier time points as well (Hees 2013; Hellstrom 2017; Knekt 2013; Rost 2004; Schene 2006). We included these outcomes in the medium‐term analysis. We used the last available observation within the first year for this purpose.

(c) Long‐term

In nine studies, the last follow‐up measurement was later than one year after inclusion, of which three reported on a follow‐up period of 18 months (Hees 2013; Reme 2015; Reme 2019), four on 24 months (Hellstrom 2017; Rost 2004; Schoenbaum 2001; Wormgoor 2020), one on 42 months (Schene 2006), and one on five years (Knekt 2013). However, only depression data and not sickness absence days were reported at two years in the Schoenbaum 2001 study. We therefore refrained from using the depression data at this time point, leaving six studies with long‐term outcome data.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 82 studies from the review. Reasons for excluding studies were:

sickness absence not measured as an outcome (Aasvik 2017; Ahola 2012; Amore 2001; Barbui 2009; Bejerholm 2017; Boyer 1998; Brandes 2011; Carlin 2010; Castillo‐Pérez 2010; Dalgaard 2014; Danielsson 2019; Dean 2017; Dunlop 2011; Endicott 2014; Erkkilä 2011; Finley 2003; Fournier 2015; Han 2015; Hirani 2010; Hobart 2019; Hollon 2016; Johansson 2019; Kennedy 2016; Kennedy 2019; Knekt 2016; Kojima 2010; Kroenke 2001; Kuhs 1996; Lam 2012; Löbner 2018; Martinez 2011; Meyer 2009; Mundt 2001; Oakes 2012; Salminen 2008; Saloheimo 2016; Sandahl 2011; Shawyer 2016; Simon 2000; Sir 2005; Soares 2019; Stant 2009; Zwerenz 2017);

participants had a mild depressive disorder or were not diagnosed with a depressive disorder (Aasdahl 2017; Aasdahl 2018; Aelfers 2013; Arends 2014; Bakker 2007; Becker 1998; Bejerholm 2015; Blonk 2007; Brouwers 2007; Dalgaard 2017; Dalgaard 2017a; Ebert 2014; Furukawa 2012; Hackett 1987; Jansson 2015; Lagerveld 2012; Lexis 2011; Mino 2006; Morgan 2011; Reavley 2018; Salomonsson 2017; Warmerdam 2007; Zeeuw 2010; Zwerenz 2017a);

not a RCT design (Bech 2000; Eklund 2012; Evans 2016; Knekt 2011; Schmitt 2008; Wisenthal 2018; Zambori 2002);

no worker population (Alexopoulos 2011; Folke 2012; Forman 2012; Gunnarson 2018; Twamley 2019);

study took place in an inpatient care setting (Dick 1985; Hordern 1964);

not able to define a subgroup of depressed patients (Beurden 2013; Gournay 1995);

a double publication (deVries 2015; Maljanen 2016; Schoenbaum 2002; Wells 2000; Winter 2015);

publication was a study protocol (Dean 2014; Ebert 2014a; Eisendrath 2014; Kooistra 2014; Zwerenz 2015);

study was prematurely terminated because of massive reorganizations and reimbursement changes in mental health care in the Netherlands during the study period (Heer 2013).

Studies awaiting assessment

There are four ongoing studies that have not reported yet: Deady 2018; Imamura 2018; Kouvonen 2019; Poulsen 2017

Risk of bias in included studies

In Figure 3 and Figure 4 an overview of the risk of bias per study is presented. For details see the 'Risk of bias' tables that form part of the Characteristics of included studies.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The method for generating random numbers posed a low risk of bias in 36 studies and was unclear in nine.

In three cluster‐RCTs (Noordik 2013; Rost 2004; Schoenbaum 2001) allocation concealment was not adequate, which was probably indicative of the non‐feasibility of allocation concealment in this type of design. In seven further studies (Agosti 1991; Björkelund 2018; Burnand 2002; Lerner 2015; Mackenzie 2014; Miller 1998; Wikberg 2017) information on allocation concealment could not be retrieved, leading to a judgment of unclear risk of bias. In 35 studies, the allocation concealment was adequate and therefore posed a low risk of bias.

Blinding

Risk of performance bias was low in studies using a double‐blind design (blinding of participant and care provider). This design was feasible in studies comparing the occupational health effects of antidepressant medications. This type of study has a low risk of performance bias (Agosti 1991; Fantino 2007; Fernandez 2005; Miller 1998; Romeo 2004; Wade 2008). In other clinical interventions, such as psychological or exercise interventions and in work‐directed interventions, blinding of the participant or care provider was not feasible. However, we considered the risk of performance bias high only in those studies where the control intervention could be considered less desirable by participants or care provider (Bee 2010; Beiwinkel 2017;Chatterton 2018;Hollinghurst 2010; Kendrick 2005; Knapstad 2020; Krogh 2009; Mackenzie 2014; McCrone 2004; Reme 2019; Sarfati 2016).

Our primary outcome measure (sickness absence days) could be measured either by self‐report or retrieval from attendance records and national registries. In the case of self‐report, the outcome could be biased by unblinded participants’ knowledge of the intervention. In 27 studies we considered the risk of detection bias to be high. With regard to the secondary outcome depression, 31 studies had a high risk of bias, and for two studies the risk was unclear. Our secondary outcome work functioning was measured in 11studies only. For reasons of clarity of the risk of bias table, the findings for this outcome were reported in Table 5.

1. Work functioning outcome: Risk of bias.

| Study | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data: attrition bias |

| Agosti 1991 | Low risk (blinded clinician) | High risk |

| Burnand 2002 | High risk (self‐report) | High risk |

| Finnes 2017 | High risk (self‐report) | Low risk |

| Hees 2013 | High risk (self‐report) | Low risk |

| Kaldo 2018 | High risk (self‐report) | High risk |

| Knekt 2013 | High risk (self‐report) | Low risk |

| Lerner 2012 | High risk (self‐report) | Low risk |

| Miller 1998 | High risk (self‐report) | Unclear risk |

| Sarfati 2016 | High risk (self‐report) | High risk |

| Wang 2007 | High risk (self‐report) | Low risk |

| Lerner 2020 | High risk (self‐report) | Low risk |

Incomplete outcome data

We found nine of the 45 studies to have a low risk of attrition bias for both sickness absence and depressive symptoms, and 15 studies with a high risk of attrition bias for both outcomes, the other 21 studies showed different levels of risk of bias for sickness absence and depressive symptoms or had an unclear risk of attrition bias for either or both outcomes. Studies with attrition between 10% and 20% could still be classified as having low risk of attrition bias if adequate analyses were conducted to take selective attrition into account. Examples of such analyses are multiple imputation methods or sensitivity analyses. Our secondary outcome work functioning was measured in only 11 studies in a way that the findings could be included in the meta‐analyses. To maintain clarity in the 'Risk of bias' table, we reported the findings for this outcome in Table 5.

Selective reporting

For 23 studies, no design paper or trial registration could be identified in order to assess the risk of selective reporting. In 15 studies we considered the risk to be low (Beiwinkel 2017; Chatterton 2018; Eriksson 2017; Geraedts 2014; Hees 2013; Hellstrom 2017; Kendrick 2005; Knapstad 2020; Lerner 2015; Lerner 2020; Meuldijk 2015; Phillips 2014; Reme 2015; Reme 2019; Vlasveld 2013). In seven studies, the risk of reporting bias was deemed high, in the Björkelund 2018 study the trial was retrospectively registered. In Mackenzie 2014 and Kaldo 2018, the trial protocol was retrospectively registered and work participation was not mentioned as an outcome. In Krogh 2009, no report was made regarding the third treatment group (relaxation) in the study protocol. In the protocol of the Sarfati 2016 study, an assessment at 6 months is announced, but this is not reported. In the Noordik 2013 study, an outcome measure that was presented in the study design was not reported as an outcome. In Volker 2015, the inclusion criteria reported in the protocol changed from depressive disorders to common mental disorders as a result of a new sponsor after years of inclusion. Also, more outcomes were added.

Other potential sources of bias

We identified other sources of bias in four studies. In Birney 2016, we identified a potential conflict of interest, as the study’s principal investigator may have had financial benefit from sales of the intervention. In Kaldo 2018, an unplanned subgroup analysis was conducted and in Mackenzie 2014 the work outcomes were unplanned. In Volker 2015, one occupational physician from the control condition was replaced by another occupational health physician, who then was allocated to the intervention condition.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings 1. Work‐directed plus clinical intervention compared to care as usual in depressed people, medium‐term follow‐up.

| Work‐directed plus clinical intervention compared to care as usual (medium‐term) in depressed people | ||||||

| Patients: Depressed persons Setting: Various: workplaces, outpatient and occupational healthcare Intervention: Work‐directed plus clinical Control: Care as usual (medium‐term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with care as usual | Risk with work‐directed intervention plus clinical intervention | |||||

| Sickness absence days | ‐ | SMD 0.25 SD lower (0.38 lower to 0.12 lower) | ‐ | 1292 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | The SMD translates back to ‐0.5 days per 2 weeks (CI ‐0.7 to ‐0.2) or ‐24.7 days in 12 months (‐37.5 to ‐11.8). |

| On sick leave | 417 per 1.000 | 451 per 1.000 (267 to 764) | RR 1.08 (0.64 to 1.83) | 1025 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Depressive symptoms‐ | ‐ | SMD 0.25 SD lower (0.49 lower to 0.01 lower) | ‐ | 1091 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | |

| Work functioning | ‐ | SMD 0.19 SD lower (0.43 lower to 0.06 higher) | ‐ | 926 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 5 | |

| The risk in the intervention group (and the 95% CI) is based on the risk in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention (and the 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SMD: Standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1A majority of the studies in the meta‐analysis (in terms of weights) showed high or unclear risk on the randomisation items (sequence and concealment), blinded outcome assessment or attrition. We therefore rated down one level due to a high risk of bias.

2Depression is self‐reported and participants were not blinded. We rated down one level due to a high risk of bias.

3Study effects varied with some clearly indicating beneficial results and some not. We rated down one level due to imprecision.

4Rated down one level due to inconsistency (I2 61%).

5Pooled effect size includes small harmful effec. Rated down one level due to wide CI (imprecision)

Summary of findings 2. Work‐directed intervention compared to care as usual in depressed people, medium‐term follow‐up.

| Work‐directed intervention compared to care as usual in depressed people | ||||||

| Patient or population: Depressed persons Setting: Workplace and occupational healthcare Intervention: Work‐directed Comparison: Care as usual (medium‐term) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with care as usual | Risk with work‐directed intervention | |||||

| Sickness absence days, medium‐term follow‐up | ‐ | SMD 0.39 higher (0.04 higher to 0.74 higher) | ‐ | 130 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | The SMD translates back to + 0.7 days in two weeks (95% CI 0.1 to 1.3) or + 38 days in 12 months (95% CI 3.9 to 73). |

| Off work, medium‐term follow‐up | 708 per 1.000 | 658 per 1.000 (545 to 786) | RR 0.93 (0.77 to 1.11) | 226 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | |

| Depressive symptoms, medium‐term follow‐up | ‐ | SMD 0.1 lower (0.3 lower to 0.1 higher) | ‐ | 390 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | |

| Work functioning, medium‐term follow‐up | ‐ | SMD 0.32 lower (0.9 lower to 0.26 higher) | ‐ | 48 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SMD: Standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1One study with unclear risk and one with serious risk of bias. Rated down one level due to high risk of bias.

2Two studies with 130 participants. CI includes harms and benefits. Rated down one level due to imprecision.

3Based on one study with small number of participants, rated down one level due to to imprecision.

4Includes studies with high risk of bias. Rated down one level due to high risk of bias.

5One study with unclear risk of bias. Rated down with one level due to high risk of bias.

Summary of findings 3. Psychological intervention compared to care as usual in depressed people, medium‐term follow‐up.

| Psychological intervention compared to care as usual in depressed people | ||||

| Patient or population: Depressed persons Setting: Various: workplaces, primary care, insurance institute and academic hospital Intervention: Psychological intervention Comparison: Care as usual | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Risk with psychological intervention | ||||

| Sickness absence days, medium‐term follow‐up | SMD 0.15 lower (0.28 lower to 0.03 lower) | 1649 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | The SMD translates back to ‐0.3 days per 2 weeks (95% CI ‐0.5 to ‐0.1) or ‐14.7 days in 12 months (95% CI ‐27.6 to ‐3.0). |

| Depressive symptoms, medium‐term follow‐up | SMD 0.3 lower (0.45 lower to 0.15 lower) | 1255 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | |

| Work ability, medium‐term follow‐up | SMD 0.05 higher (0.46 lower to 0.57 higher) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 4 5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; SMD: Standardised mean difference. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

1In most studies, the outcome was self‐reported, leading to risk of bias in outcome assessment. There was also large attrition. Rated down one level due to high risk of bias.

2Funnel plot shows missing small studies with no effect or harmful effect. Rated down one level due to risk of publication bias.

3Outcomes self‐reported in unblinded studies. Rated down one level due to high risk of bias

4CI includes appreciable harms and benefits. Sole study. Rated down two levels due to imprecision.

5One study with unclear risk of bias. Rated down one level due to high risk of bias.

Summary of findings 4. Improved care compared to care as usual in depressed people, medium‐term follow‐up.

| Improved care compared to care as usual in depressed persons | ||||||

| Patient or population: Depressed persons Setting: Primary Care and community mental health Intervention: Improved Care Comparison: Care as usual | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with care as usual | Risk with improved care | |||||

| Sickness absence days, medium‐term follow‐up | ‐ | SMD 0.06 lower (0.15 lower to 0.04 higher)1 | ‐ | 1912 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | The SMD translates back to ‐0.1 days per 2 weeks (95% CI ‐0.3 to 0.1) or ‐5.9 days in 12 months (95% CI ‐14.8 to 3.9). The SMD of the sensitivity analysis1 translates back to ‐0.4 days per 2 weeks (95% CI ‐0.6 to ‐0.1) or ‐19.7 days in 12 months (95% CI ‐34.5 to ‐4.9). |

| Off work, medium‐term follow up | 496 per 1.000 | 516 per 1.000 (402 to 655) | RR 0.97 (0.77 to 1.22) | 362 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3,4 | |

| Depressive symptoms, medium‐term follow‐up | ‐ | SMD 0.21 SD lower (0.35 lower to 0.07 lower) | ‐ | 1808 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | |

| Work functioning, medium‐term follow‐up | ‐ | SMD 0.5 higher (0.34 higher to 0.66 higher) | ‐ | 604 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SMD: Standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 A sensitivity analysis revealed that two RCTs with a lower risk of bias found a SMD of 0.20 lower (0.35 lower to 0.05 lower); moderate‐certainty evidence).

2 Majority of studies at high risk; downgraded with one level due to high risk of bias.

3 One study at high risk of bias, downgraded with one level due to high risk of bias.

4 One study with less than 400 participants, downgraded with one level due to imprecision

5 Study with unblinded outcome assessment, rated down one level due to high risk of bias.

Below we present the results for our primary outcome, sickness absence, for each of the comparisons. We present our secondary outcomes, depressive symptoms and work functioning, for each of the work‐directed interventions as well.

1. Work‐directed interventions

1.1 Work‐directed plus clinical intervention compared to care as usual (medium‐term follow‐up)