Abstract

Background

Antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) is associated with poor mental health, criminality, substance use and relationship difficulties. This review updates Gibbon 2010 (previous version of the review).

Objectives

To evaluate the potential benefits and adverse effects of psychological interventions for adults with AsPD.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 13 other databases and two trials registers up to 5 September 2019. We also searched reference lists and contacted study authors to identify studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of adults, where participants with an AsPD or dissocial personality disorder diagnosis comprised at least 75% of the sample randomly allocated to receive a psychological intervention, treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), waiting list or no treatment. The primary outcomes were aggression, reconviction, global state/functioning, social functioning and adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

This review includes 19 studies (eight new to this update), comparing a psychological intervention against TAU (also called 'standard Maintenance'(SM) in some studies). Eight of the 18 psychological interventions reported data on our primary outcomes.

Four studies focussed exclusively on participants with AsPD, and 15 on subgroups of participants with AsPD. Data were available from only 10 studies involving 605 participants.

Eight studies were conducted in the UK and North America, and one each in Iran, Denmark and the Netherlands. Study duration ranged from 4 to 156 weeks (median = 26 weeks). Most participants (75%) were male; the mean age was 35.5 years. Eleven studies (58%) were funded by research councils. Risk of bias was high for 13% of criteria, unclear for 54% and low for 33%.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) + TAUversus TAU

One study (52 participants) found no evidence of a difference between CBT + TAU and TAU for physical aggression (odds ratio (OR) 0.92, 95% CI 0.28 to 3.07; low‐certainty evidence) for outpatients at 12 months post‐intervention.

One study (39 participants) found no evidence of a difference between CBT + TAU and TAU for social functioning (mean difference (MD) −1.60 points, 95% CI −5.21 to 2.01; very low‐certainty evidence), measured by the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ; range = 0‐24), for outpatients at 12 months post‐intervention.

Impulsive lifestyle counselling (ILC) + TAU versus TAU

One study (118 participants) found no evidence of a difference between ILC + TAU and TAU for trait aggression (assessed with Buss‐Perry Aggression Questionnaire‐Short Form) for outpatients at nine months (MD 0.07, CI −0.35 to 0.49; very low‐certainty evidence).

One study (142 participants) found no evidence of a difference between ILC + TAU and TAU alone for the adverse event of death (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.04 to 4.54; very low‐certainty evidence) or incarceration (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.86; very low‐certainty evidence) for outpatients between three and nine months follow‐up.

Contingency management (CM) + SM versus SM

One study (83 participants) found evidence that, compared to SM alone, CM + SM may improve social functioning measured by family/social scores on the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; range = 0 (no problems) to 1 (severe problems); MD −0.08, 95% CI −0.14 to −0.02; low‐certainty evidence) for outpatients at six months.

‘Driving whilst intoxicated' programme (DWI) + incarcerationversus incarceration

One study (52 participants) found no evidence of a difference between DWI + incarceration and incarceration alone on reconviction rates (hazard ratio 0.56, CI −0.19 to 1.31; very low‐certainty evidence) for prisoner participants at 24 months.

Schema therapy (ST) versus TAU

One study (30 participants in a secure psychiatric hospital, 87% had AsPD diagnosis) found no evidence of a difference between ST and TAU for the number of participants who were reconvicted (OR 2.81, 95% CI 0.11 to 74.56, P = 0.54) at three years. The same study found that ST may be more likely to improve social functioning (assessed by the mean number of days until patients gain unsupervised leave (MD −137.33, 95% CI −271.31 to −3.35) compared to TAU, and no evidence of a difference between the groups for overall adverse events, classified as the number of people experiencing a global negative outcome over a three‐year period (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.19). The certainty of the evidence for all outcomes was very low.

Social problem‐solving (SPS) + psychoeducation (PE) versus TAU

One study (17 participants) found no evidence of a difference between SPS + PE and TAU for participants’ level of social functioning (MD −1.60 points, 95% CI −5.43 to 2.23; very low‐certainty evidence) assessed with the SFQ at six months post‐intervention.

Dialectical behaviour therapy versus TAU

One study (skewed data, 14 participants) provided very low‐certainty, narrative evidence that DBT may reduce the number of self‐harm days for outpatients at two months post‐intervention compared to TAU.

Psychosocial risk management (PSRM; 'Resettle') versus TAU

One study (skewed data, 35 participants) found no evidence of a difference between PSRM and TAU for a number of officially recorded offences at one year after release from prison. It also found no evidence of difference between the PSRM and TAU for the adverse event of death during the study period (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.05 to 14.83, P = 0.94, 72 participants (90% had AsPD), 1 study, very low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

There is very limited evidence available on psychological interventions for adults with AsPD. Few interventions addressed the primary outcomes of this review and, of the eight that did, only three (CM + SM, ST and DBT) showed evidence that the intervention may be more effective than the control condition. No intervention reported compelling evidence of change in antisocial behaviour. Overall, the certainty of the evidence was low or very low, meaning that we have little confidence in the effect estimates reported.

The conclusions of this update have not changed from those of the original review, despite the addition of eight new studies. This highlights the ongoing need for further methodologically rigorous studies to yield further data to guide the development and application of psychological interventions for AsPD and may suggest that a new approach is required.

Plain language summary

Psychological treatments for people with antisocial personality disorder

Background

People with antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) may behave in a way that is harmful to themselves or others and is against the law. They can be dishonest and act aggressively without thinking. Many also misuse drugs and alcohol. Certain types of psychological treatment, such as talking or thinking therapies, may help people with AsPD. Such treatments aim to change the person’s behaviour, to change the person’s thinking, or to help the person manage feelings of anger, self‐harm, drug and alcohol abuse or negative behaviour.

This review updates one published in 2010.

Review question

What are the effects of talking or thinking therapies for adults (aged 18 years and older) with AsPD, compared to treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), waiting list or no treatment?

Study characteristics

We searched for relevant studies up to 5 September 2019. We found 19 relevant studies for 18 different psychological interventions. Data were reported for 10 studies involving 605 adults (aged 18 years and older) with a diagnosis of AsPD, living in the community, hospital or prison. Eight interventions reported on the main outcomes of the review (aggression, reconviction, general/social functioning and adverse events), but few had data for participants with AsPD. The studies compared a psychological intervention against TAU, which is sometimes referred to as 'standard maintenance' (SM).

Most studies were conducted in the UK or North America and were financed by grants from major research councils. They included more male (75%) participants than females (25%), the average age of which was 35.5 years. The length of the studies ranged from 4 weeks to 156 weeks. Most of the studies (10 of the 19) used methods that were flawed, which means we cannot be certain of their findings and, as a result, are unable to draw any firm conclusions.

Main results

Below, we report the findings for each comparison, where data were available for a primary outcome.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) + TAUversus TAU. There was no difference between CBT + TAU and TAU for physical aggression or social functioning but the evidence is uncertain.

Impulsive lifestyle counselling (ILC) + TAU versus TAU. There was no difference between ILC + TAU and TAU for aggression or the adverse events of death or incarceration but the evidence is very uncertain.

Contingency management (CM) + SM versus SM. CM + SM, compared to SM, may improve social functioning slightly.

‘Driving whilst intoxicated' programme (DWI) + incarcerationversus incarceration. There was no difference between DWI + incarceration and incarceration on reconviction (re‐arrest) rates but the evidence is very uncertain.

Schema therapy (ST) versus TAU. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ST compared to TAU on reconviction. There is some evidence that, compared to TAU, ST may improve one aspect of social functioning: time to unescorted leave. There was no difference between ST and TAU for overall adverse events classified globally as negative outcomes but the evidence is very uncertain.

Social problem‐solving therapy (SPS) + psychoeducation (PE) versus TAU. There was no difference between SPS + PE and TAU for participants’ level of social functioning but the evidence is very uncertain.

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) versus TAU. There was a suggestion that, compared to TAU, DBT may reduce for the number of self‐harm days but the evidence is very uncertain.

Psychosocial risk management (PSRM 'Resettle' programme) versus TAU. There was no difference between PSRM and TAU for the number of offences reported one year after release from prison, or for the risk of dying during the study, although the evidence is very uncertain.

Conclusions

The review shows that there is not enough good quality evidence to recommend or reject any psychological treatment for people with a diagnosis of AsPD.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Cognitive behaviour therapy + treatment‐as‐usual versus treatment‐as‐usual alone for antisocial personality disorder.

| Cognitive behaviour therapy + treatment‐as‐usual versus treatment‐as‐usual alone for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: outpatient Intervention: cognitive behaviour therapy + treatment‐as‐usual Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment‐as‐usual alone | Risk with cognitive behaviour therapy + treatment‐as‐usual | |||||

|

Aggression (any act of physical aggression) Assessed by: number reporting any act of physical aggression measured with the MacArthur Community Violence Screening Instrument (MCVSI) (9 behavioural items, rated yes/no; higher score = greater number of violent behaviour reported) Timing of assessment: 12 months |

Study population | OR 0.92 (0.28 to 3.07) | 52 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | ‐ | |

| 296 per 1000 | 279 per 1000 (17 fewer per 1000; from 191 fewer to 268 more) | |||||

| Reconviction | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Social functioning Assessed by: Social Functioning Questionnaire (range of possible scores = 0‐24; higher score = poorer outcome) Timing of assessment: 12 months |

The mean social functioning score in the control group was 11.6 points | The mean social functioning score in the intervention group was 1.6 points lower (5.21 lower to 2.01 higher) | ‐ | 39 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | ‐ |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded two levels overall. We downgraded one level due to limitations in the design/implementation suggested possible risk of bias ('blinding of participants' bias and possible risk of 'blinding of personnel' bias), and one level for imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not being met. bEvidence downgraded three levels overall. We downgraded one level due to limitations in the design/implementation suggested possible risk of bias ('blinding of participants' bias and possible risk of 'blinding of personnel' bias), one level for imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not being met, and one level for indirectness as the outcome was measured by a questionnaire.

Summary of findings 2. Impulsive lifestyle counselling + treatment‐as‐usual versus treatment‐as‐usual alone for antisocial personality disorder.

| Impulsive lifestyle counselling + treatment‐as‐usual versus treatment‐as‐usual alone for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: outpatient Intervention: Impulsive lifestyle counselling + treatment‐as‐usual Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment‐as‐usual alone | Risk with impulsive lifestyle counselling + treatment‐as‐usual | |||||

|

Aggression: trait Assessed by: Buss‐Perry Aggression Questionnaire ‐ Short Form (12 items rated on 5‐point Likert scale ranging from extremely uncharacteristic (1) to extremely characteristic (5); range = 12‐60; high score = poor outcome) Timing of assessment: 9 months |

The mean trait aggression score in the control group was 3.52 points | The mean trait aggression score in the intervention group was 0.07 points higher (0.35 lower to 0.49 higher) | ‐ | 118 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

| Reconviction | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Social functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Adverse events: death Assessed by: number of participant deaths between a 3‐ and 9‐month follow‐up period Timing of assessment: between 3 and 9 months |

Study population | OR 0.40 (0.04 to 4.54) | 142 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ | |

| 31 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (19 fewer per 1000; from 30 fewer to 96 more) | |||||

|

Adverse events:incarceration Assessed by: incarceration between a 3‐ and 9‐month follow‐up period Timing of assessment: 9 months |

Study population | OR 0.70 (0.27 to 1.86) | 142 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ | |

| 156 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 (41 fewer per 1000; from 109 fewer to 100 more) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded three levels overall. We downgraded two levels for limitations in the design/implementation suggested high risk of bias (‘incomplete outcome data/attrition’ bias; possible risk of ‘allocation concealment’ bias, ‘blinding of participants’ bias, ‘blinding of personnel’ bias, ‘blinding of outcome assessors’ bias, ‘selective reporting’ bias and ‘other’ bias), and one level for imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not being met .

Summary of findings 3. Contingency management + standard maintenance versus standard maintenance alone for antisocial personality disorder.

| Contingency management + standard maintenance versus standard maintenance alone for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: outpatient Intervention: contingency management + standard maintenance Comparison: standard maintenance alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard maintenance alone | Risk with contingency management + standard maintenance | |||||

| Aggression | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Reconviction | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Social functioning Assessed by: adjusted composite scores on the Family/Social domain of the Addiction Severity Index (composite scores range from no problems (0) to severe problems (1); higher score = worse outcome) Timing of assessment: 6 months |

The mean social functioning score in the control group was 0.16 points | The mean social functioning score in the intervention group was 0.08 points lower (0.14 lower to 0.02 lower) | ‐ | 83 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Analysis based on summary data of completers supplied by the trial investigators and derived from a mixed regression model that included time‐specific random effects and an interaction term (see Table 4). |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded two levels overall. We downgraded one level due to possible risk of bias ('blinding of participants' bias, possible risk of 'blinding of personnel' and possible risk of 'incomplete outcome data/attrition' bias), and one level due to likely imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not met.

13. Comparison 3. Contingency management (CM) + standard maintenance (SM) versus SM: Addiction Severity Index scores.

| Study | Outcome | Experimental group: CM + SM | Control group: SM | Difference of least square means over months 1 to 6 | df | P value | Comments | ||

| Adjusted mean | SE | Adjusted mean | SE | ||||||

| Neufeld 2008 | Family/social domain scores | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 81 | 0.005 | Favours experimental group: CM + SM |

| Neufeld 2008 | Employment domain scores | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.006 | 81 | 0.91 | Favours neither group |

| Neufeld 2008 | Alcohol domain scores | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 81 | 0.17 | Favours neither group |

| Neufeld 2008 | Drug domain scores | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 81 | 0.09 | Favours neither group |

| CM: contingency management; df: degrees of freedom SE: standard error; SM: standard maintenance. | |||||||||

Summary data supplied by the trial investigators. Adjusted means obtained from mixed regression model, which included time‐specific random effects and an interaction term.

Summary of findings 4. 'Driving whilst intoxicated' programme + incarceration versus incarceration alone for antisocial personality disorder.

| 'Driving whilst intoxicated programme' + incarceration versus incarceration alone for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: prison Intervention: 'driving whilst intoxicated' programme + incarceration Comparison: incarceration alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with incarceration alone | Risk with 'driving whilst intoxicated' programme + incarceration | |||||

| Aggression | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Reconviction (for drink‐driving) Assessed by: Cox regression of re‐arrest rates over 24 months Timing of assessment: 24 months |

‐ | ‐ | HR 0.56 (−0.19 to 1.31) | 52 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Social functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded three levels overall. We downgraded two levels for limitations in the design/implementation suggested possible risk of bias (‘random sequence generation’ bias, ‘allocation concealment’ bias, ‘blinding of participants’ bias, ‘blinding of personnel’ bias, ‘blinding of outcome assessors’ bias, ‘incomplete outcome data/attrition’ bias and ‘other’ bias), and one level for likely imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not being met.

Summary of findings 5. Schema therapy versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder.

| Schema therapy versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: forensic psychiatric clinic Intervention: schema therapy Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment‐as‐usual | Risk with schema therapy | |||||

| Aggression | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available | |

|

Reconviction Assessed by: number of participants documented to have recidivated (documented as a global negative outcome) Timing of assessment: over the 3 years |

Study population | OR 2.81 (0.11 to 74.56) | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ | |

| 0 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 (0 fewer to 0 more) | |||||

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available | |

|

Social functioning Assessed by: mean number of days until unsupervised leave grantedb Timing of assessment: over the 3 years |

The mean number of days to unsupervised leave in the control group was817.13 days | The mean number of days to unsupervised leave in the intervention group was137.33 fewerdays (271.31 fewer to 3.35 fewer) | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

|

Adverse events Assessed by: number of participants with a global negative outcome (e.g. dropping out of therapy, recidivism or being transferred to another facility due to poor treatment response) overall Timing of assessment: over the 3 years |

Study population | ‐ | ||||

| 357 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (168 fewer per 1000; 315 fewer to 192 more) | OR 0.42 (0.08 to 2.19) | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AsPD: antisocial personality disorder; CI: confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom OR: odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence was downgraded three levels overall. We downgraded one level due to limitations in the design/implementation suggested high risk of bias (‘selective reporting’ bias; possible risk of ‘blinding of participants’ bias, ‘blinding of personnel’ bias, ‘blinding of outcome assessors’ bias and ‘other’ bias), one level for indirectness (only 87% of the population had a diagnosis of AsPD and subgroup data for AsPD only were not available), and one level for imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not being met. bWe chose to report 'days to unescorted leave' (rather than 'days to escorted leave'), as the measure of social functioning, as this reflects the person gaining a higher level of independence and progress. The results for 'days to escorted leave' (at both two and three years) are reported in the Effects of interventions section.

Summary of findings 6. Social problem‐solving therapy + psychoeducation versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder.

| Social problem‐solving therapy + psychoeducation versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: outpatient Intervention: social problem‐solving therapy + psychoeducation Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment‐as‐usual | Risk with social problem‐solving therapy + psychoeducation | |||||

| Aggression | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Reconviction | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Social functioning

Assessed by: Social Functioning Questionnaire (8 items rated on 4‐point scale; anchors vary across items; high score = poor outcome) Timing of assessment: 6 months |

The mean social functioning score in the control group was 11.78 points | The mean social functioning score in the intervention group was 1.60 points lower (5.43 lower to 2.23 higher) | ‐ | 17 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded three levels overall. We downgraded one level for limitations in the design/implementation suggested possible risk of bias, one level for indirectness (the outcome was measured by questionnaire), and one level for imprecision due to optimal information size criterion not being met.

Summary of findings 7. Dialectical behaviour therapy versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder.

| Dialectical behaviour therapy versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Setting: outpatient Intervention: dialectical behaviour therapy Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment‐as‐usual | Risk with dialectical behaviour therapy | |||||

| Aggression | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Reconviction | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Social functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Adverse events (self‐harm) Assessed by: mean number of self‐harm days in past 2 months Timing of assessment: 2 months |

The mean number of self‐harm days for participants in the DBT group was 3.6 (SD = 6.95, range = 0 to 160), compared to 12.22 (SD = 19.58, range = 0 to 57) for participants in the TAU group | ‐ | 14 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | Narrative data only (skewed data; see Table 9) | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DBT: dialectical behaviour therapy; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; TAU: treatment‐as‐usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Schünemann 2013) High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded three levels overall, due to possible risk of bias (‘blinding of participants’ bias, ‘blinding of personnel’ bias, ‘blinding of outcome assessors’ bias, ‘incomplete outcome data/attrition’ bias and ‘selective reporting’ bias; downgraded one level), and likely imprecision (downgraded two levels) due to optimal information size criterion not being met as well as skewed data.

20. Comparison 7. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) versus treatment‐as‐usual (TAU): number of self‐harm days (skewed data).

| Study | Outcome | Experimental group: DBT | Control group: TAU | Statistic | Comments | ||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| Priebe 2012 | Adverse events: number of self‐harm days in past 2 months (averaged), at baseline | 5 | 17.27 | 25.34 | 9 | 10.7 | 6.31 | None reporteda | DBT range = 0.83 to 60.83; TAU range = 1.0 to 18.67 |

| Priebe 2012 | Adverse events: number of self‐harm days in past 2 months (averaged), at 2 months | 5 | 3.6 | 6.95 | 9 | 12.22 | 19.58 | None reporteda | DBT range = 0 to 16; TAU range = 0 to 57 |

| AsPD: antisocial personality disorder; DBT: Dialectical Behavior Therapy; n: numbers of participants; SD: standard deviation; TAU: treatment as usual. | |||||||||

aSummary data for AsPD subgroup (n = 14) provided by K Barnicot on 2 March 2017; no statistics provided.

Summary of findings 8. Psychosocial risk management ('Resettle' programme) versus treatment‐as‐usual for antisocial personality disorder.

| Psychosocial risk management ('Resettle' programme) compared with treatment‐as‐usual (standard probation supervision) for antisocial personality disorder | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with antisocial personality disorder Settings: prison and community Intervention: psychosocial risk management (PSRM 'Resettle' programme) Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual (standard probation supervision) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment‐as‐usual alone | Risk with psychosocial risk management 'Resettle' | |||||

| Aggression | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Reconviction: total number of official offences recorded (higher number = worse outcome) Timing of the assessment: 1 year after release from prison |

The mean number of official offences recorded for 16 participants in the PSRM group one year after release from prison was 4.13 (SD = 5.78, range = 0 to 22), compared to 5.21 (SD = 3.28, range = 0 to 11) for 19 participants in the TAU group | ‐ | 35 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | Narrative data only (skewed data), see Table 11 | |

| Global state/functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

| Social functioning | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available |

|

Adverse events: death during the study period Timing of assessment: 2 years after release from prison |

29 per 1000 |

26 per 1000 3 fewer per 1000 (28 fewer to 281 more) |

OR 0.89 (0.05 to 14.83) | 35 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; PSRM: Psychosocial risk management; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; SD: Standard deviation; TAU: Treatment‐as‐usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aEvidence downgraded three levels overall due to high risk of bias (‘blinding of personnel’ bias, ‘blinding of outcome assessors’ bias, ‘incomplete outcome data/attrition’ bias, ‘selective reporting’ bias and 'other' bias; downgraded two levels), and likely imprecision (downgraded one level) due to optimal information size criterion not being met as well as skewed data.

23. Comparison 11 Psychosocial Risk Management 'Resettle' programme (PSRM) versus treatment‐as‐usual (probation supervision): recidivism (skewed data).

| Study | Outcome | Experimental group: PSRM | Control group: TAU | Statistic | Commentsa | ||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||||

| Nathan 2019 | Recidivism: total number of official criminal offences recorded in year 1 (higher = worse outcome) | 16 | 4.13 | 5.78 | 19 | 5.21 | 3.28 | None reported | Experimental group median = 2, range = 0 to 22; control group median = 4, range = 0 to 11 |

| Nathan 2019 | Recidivism: total number of official criminal offences recorded in year 2 (higher = worse outcome) | 8 | 3.63 | 4.10 | 8 | 3.25 | 3.77 | None reported | Experimental group median = 2, range = 0 to 11; control group median = 1.5, range = 0 to 9 |

| Nathan 2019 | Recidivism: total number of self‐report antisocial acts as reported by SRD in year 1 (higher = worse outcome) | 16 | 9.69 | 19.34 | 19 | 7.37 | 5.17 | None reported | Experimental group median = 4, range = 0 to 78; control group median = 7, range = 0 to 17 |

| Nathan 2019 | Recidivism: total number of self‐report antisocial acts as reported by SRD in year 2 (non‐cumulative) (higher = worse outcome) | 8 | 8.75 | 14.05 | 9 | 7.33 | 9.51 | None reported | Experimental group median = 2, range = 0 to 38 ; control group median = 4, range = 0 to 27 |

| AsPD: antisocial personality disorder; PSRM: Psychosocial risk management 'resettle' programme n: numbers of participants; SD: standard deviation; SRD: Self‐Report Delinquency scale; TAU: treatment as usual. | |||||||||

aRaw data provided by study authors; all descriptive statistics extracted by review authors for participants with a definite or probable diagnosis of AsPD.

Background

Description of the condition

Antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) is one of the 10 specific personality disorder categories in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5). The DSM‐5 defines personality disorder as "an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual's culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment" (p 645). The general criteria for personality disorder according to DSM‐5 are given in Table 12.

1. DSM‐5 general criteria for personality disorder.

| Criteria | Description (DSM‐5, p 646‐7) |

| A. | An enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture. This pattern is manifested in two (or more) of the following areas.

|

| B. | The enduring pattern is inflexible and pervasive across a broad range of personal and social situations. |

| C. | The enduring pattern leads to clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. |

| D. | The pattern is stable and of long duration, and its onset can be traced back at least to adolescence or early adulthood. |

| E. | The enduring pattern is not better explained as a manifestation or consequence of another mental disorder. |

| F. | The enduring pattern is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of abuse, a medication) or a another medical condition (e.g. head trauma). |

DSM‐5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐Fifth Edition

AsPD is described in the DSM‐5 as “a pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others” (p 645). In order to be diagnosed with AsPD (301.7) according to the DSM‐5, a person must fulfil both the general criteria for personality disorder outlined above and also the specific criteria for AsPD (criteria A, B, C and D, as shown in Table 13). DSM‐5 also states, in reference to the traits of AsPD, that “this pattern has also been referred to as psychopathy, sociopathy or dyssocial personality disorder” (p 659). There continues, however, to be debate about the status of psychopathy compared to AsPD (for example, see Ogloff 2006), how it is measured and the degree to which it is subject to change, which is beyond the scope of this review.

2. DSM‐5 diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder (301.7).

| Criteria | Description (DSM‐5, p 659) |

| A. | A pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, occurring since age 15 years, as indicated by three (or more) of the following.

|

| B. | The individual is at least 18 years. |

| C. | There is evidence of conduct disorder with onset before age of 15 years. |

| D. | The occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. |

DSM‐5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐Fifth Edition

The focus of this review is AsPD, although this condition is often classified as dissocial personality disorder (F60.2) also, using the International Classification of Diseases ‐ 10 Edition (ICD‐10). AsPD and dissocial personality disorder are often used interchangeably by clinicians and they describe a very similar presentation. While there is considerable overlap between these two diagnostic systems, they differ in two respects. First, the DSM‐5 requires that those meeting the diagnostic criteria also show evidence of conduct disorder with onset before the age of 15 years, whereas there is no such requirement when making the diagnosis of dissocial personality disorder using ICD‐10 criteria. However, a study comparing participants meeting the full criteria for AsPD (which the DSM‐5 has retained) with those who otherwise fulfilled criteria for AsPD but who did not demonstrate evidence of childhood conduct disorder, did not find any clinically important differences (Perdikouri 2007). Second, dissocial personality disorder focuses more on interpersonal deficits (for example, incapacity to experience guilt, a very low tolerance of frustration, proneness to blame others) and less on antisocial behaviour. Table 14 shows the ICD‐10 diagnostic criteria to diagnose dissocial personality disorder (F60.2).

3. ICD‐10 diagnostic criteria for dissocial personality disorder (F60.2).

| Description (ICD‐10) |

Personality disorder, usually coming to attention because of gross disparity between behaviour and the prevailing social norms, and characterised by:

There may also be persistent irritability as an associated feature. Conduct disorder during childhood and adolescents, though not invariably present, may further support the diagnosis. |

ICD‐10: International Classification of Diseases‐Tenth Revision

It is acknowledged that the classification and diagnosis of personality disorder is an area of controversy and complexity with ongoing debate about the usefulness of multiple categories of personality disorder versus a dimensional approach (Tyrer 2015; Skodol 2018), and others who feel the very label of personality disorder to be pejorative and unhelpful (Johnstone 2018, p 221). Indeed, a major paradigm shift in the conceptualisation of personality disorder is being suggested in the latest iteration of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐11). The proposed ICD‐11 model takes a dimensional approach and is made up of three components; a general severity rating; five maladaptive personality trait domains; and a borderline pattern qualifier (Oltmanns 2019). The proposed classification changes to personality disorder, however, are outside the scope of this review, which is focussed on interventions for AsPD, as defined in the current, predominant classification systems of DSM‐5 and ICD‐10.

Most studies report the prevalence of AsPD to be between 2% and 3% in the general population (Moran 1999; Coid 2006; NICE 2015). A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries found a prevalence rate for AsPD of 3% (Volkert 2018). Prevalence rates are considerably higher in men compared with women (Dolan 2009; NICE 2015) and a 3:1 ratio of men to women has been described (Compton 2005). It has also been suggested that there are sex differences in how this condition may present, with women with AsPD being less likely than men with AsPD to present with violent antisocial behaviour (Alegria 2013). AsPD (and other personality disorder diagnoses) may be less likely to be diagnosed in non‐white populations (McGilloway 2010).

As would be expected, AsPD is especially common in prison settings. In the UK prison population, the prevalence of people with AsPD has been identified as 63% in male remand prisoners, 49% in male sentenced prisoners and 31% in female prisoners (Singleton 1998). A systematic review of mental disorders in prisoners examined 62 studies from 12 countries and reported the prevalence of AsPD in male prisoners to be 47%, with prisoners approximately 10 times more likely to have AsPD than the general population (Fazel 2002).

The condition is associated with a wide range of disturbance, including greatly increased rates of criminality, substance use, unemployment, homelessness and relationship difficulties (Martens 2000), as well as negative long‐term outcomes. Many adults with AsPD are imprisoned at some point in their life. Although follow‐up studies have demonstrated some improvement over the longer term, particularly in rates of re‐offending (Weissman 1993; Grilo 1998; Martens 2000), men with AsPD who reduce their offending behaviour over time may nonetheless continue to have major problems in their interpersonal relationships (Paris 2003). Black 1996 found that men with AsPD who were younger than 40 years of age had a strikingly high rate of premature death, and obtained a value of 33 for the standardised mortality rate (the age‐adjusted ratio of observed deaths to expected deaths), meaning that they were 33 times more likely to die than males of the same age without this condition. This increased mortality was linked not only to an increased rate of suicide but also to reckless behaviours such as drug misuse and aggression. A 27‐year follow‐up study also found AsPD to be a strong predictor of all‐cause mortality (Krasnova 2019). Black 2015 noted that earlier age of onset has been linked to poorer long‐term outcomes, although marriage, employment, early incarceration and degree of socialisation may act as moderating factors. Follow‐up studies in forensic psychiatric settings suggest a similarly concerning picture. For example, Davies 2007 reported that 20 years after discharge from a medium‐secure unit almost half of the patients were reconvicted, with reconviction rates higher in those with personality disorder compared to those with mental illness (such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder). Similarly, Coid 2015 examined reconviction after discharge from seven medium‐secure units in England and Wales and found that patients with personality disorder were more than two and a half times more likely than those with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder to violently offend after discharge.

Significant comorbidity exists between AsPD and many mental health conditions; mood and anxiety disorders are common (Goodwin 2003; Black 2010; Galbraith 2014). The presence of personality disorder co‐occurring with another mental health condition may have a negative impact on the outcome of the latter (Skodol 2005; Newton‐Howes 2006). There is a particularly strong association between AsPD and substance use disorders (Robins 1998). Compared to those without AsPD, those with AsPD are 15 times more likely to meet the criteria for drug dependence and seven times more likely to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence (Trull 2010). Guy 2018 reported that 77% of people with AsPD met the lifetime criteria for alcohol use disorder.

Description of the intervention

Psychological interventions have traditionally been the mainstay of treatment for AsPD, but the evidence upon which this is based is weak (Duggan 2007; Gibbon 2010; NICE 2010). Psychological therapies encompass a wide range of interventions (Bateman 2004a), and those that may be used in AsPD are drawn from all the main areas of psychological treatment. These interventions may be delivered on an individual basis, in a group, or in a mixture of group and individual sessions. By their nature, such interventions tend to be delivered over many weeks and typically last between three months and 12 months. Due to the heterogeneity of possible psychological interventions, it is beyond the scope of this review to summarise them in detail.

Table 15 gives a summary of examples of psychological interventions that may be used for this condition. Those wishing to learn more about the theoretical basis and delivery of specific therapies are directed to the references provided in Table 15.

4. Examples of types of psychological interventions and how they might work.

| Psychological intervention | How the intervention may work |

| Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) | CBT‐based treatments place emphasis on encouraging the patient to challenge their core beliefs and thoughts in order to gain insight into how these influence their feelings and behaviour (Bateman 2004a; Henwood 2015). |

| Cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) | CAT utilises ideas from psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive therapy (Denman 2001). CAT encourages patients to identify and change learned attitudes and beliefs about themselves and how these impact on their patterns of relating to others. |

| Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) | DBT is a complex psychological intervention developed using some of the principles of CBT (Linehan 1993). DBT provides individuals with skills training in four modules (i.e. mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness). |

| Psychoanalytic therapy or dynamic psychotherapy |

The British Psychoanalytic Council defines psychoanalytic therapies as "a range of therapeutic treatments derived from psychoanalytic ideas and methods and a critical appreciation of the effect of childhood experiences on adult personality development" (British Psychoanalytical Council 2018; quote, p 2). (see also Piper 1993, Winston 1994, Bateman 2001 and Leichsenring 2003). |

| Mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT) | MBT has developed from attachment theory and aims to help patients identify and reflect on what they, and others are feeling and why, in order to better regulate their behaviour and emotions (Bateman 2004b). |

| Schema therapy (ST) | In ST, the therapist helps the patient identify long‐standing, self‐defeating patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving (‘schemas’) and develop healthier alternatives to replace them (Young 2003). |

| Nidotherapy | Nidotherapy is a formalised, planned method for achieving environmental change to minimise the effect of the participant’s difficulties upon themselves and others. Unlike most other therapies, it aims to fit the immediate environment to the patient, rather than change the patient to cope in the existing environment (Tyrer 2007). In order to achieve this, a detailed psychological formulation is developed for the individual participant (Tyrer 2005a). |

| Therapeutic community (TC) treatment | TC treatments involve participants engaging in group psychotherapy whilst being involved in a shared, therapeutic environment. This provides them with an opportunity to “explore intrapsychic and interpersonal problems and find more constructive ways of dealing with distress” (Campling 2001, quote, p 365). (see also Lees 1999). |

| Contingency management | Contingency management is based on the psychological principles of behaviour modification and aims to incentivise and reinforce changes in behaviour through the use of financial (or other rewards) that are of value to the patient. (Petry 2011). |

CAT = Cognitive analytic therapy CBT = Cognitive behaviour therapy DBT = Dialectical behavioural therapy MBT = Mentalisation‐based therapy ST = Schema therapy TC = Therapeutic community

It is important to note that this review considers all relevant studies without restriction on the type of psychological therapy, and also considers psychological interventions where drugs are given as an adjunctive intervention.

How the intervention might work

The exact mechanism of action of psychological interventions is unclear and different psychological treatments place different emphasis upon particular putative mechanisms of action. For example, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)‐based techniques place emphasis on changing thinking patterns and behaviours, whilst more psychoanalytic‐based approaches place greater emphasis on aiding the person to develop a better understanding of their current self and how this relates to their past experiences, and how unconscious processes and conflict influence interpersonal relationships. Common aspects of psychological therapies are the use of direct (usually verbal) communication between the therapist and the person, to develop a shared understanding of difficulties, and linking this to changes in thinking and behaviour (Muran 2018). These therapies may also involve changing behaviours and the environment as a way to change thinking and encourage more positive actions.

When treating AsPD, it is hoped that psychological interventions will allow the person to develop a better understanding of themselves, others and their difficulties, and that from this they will develop new skills in order to better manage themselves and life difficulties, leading to a decrease in impulsivity, anger, self‐harm, rule‐breaking, substance abuse and negative behaviour.

Those wishing to learn more about the theoretical basis of specific therapies are directed to the additional references provided in Table 15.

Why it is important to do this review

AsPD is an important condition that has a considerable impact on individuals, families and society. Even by the most conservative estimate, AsPD appears to have the same prevalence in men as schizophrenia, the condition that receives the greatest attention from mental health professionals. Furthermore, AsPD is associated with significant costs (Sampson 2013), arising from emotional and physical damage to people, damage to property, use of police time and involvement of the criminal justice system and prison services. Related costs include increased use of healthcare facilities, lost employment opportunities, family disruption, gambling and problems related to alcohol and substance misuse (Myers 1998; Kershaw 1999). In one study, Scott 2001, the lifetime public services costs for a group of adults with a history of conduct disorder (of which 50% will go on to develop adult AsPD) were found to be 10 times those for a similar group without the disorder.

AsPD is closely associated with criminal offending and any intervention that seeks to improve the outcome of AsPD is also likely to impact upon this offending. Aos 1999 reported that for some crimes (especially those involving violence), the cost benefits in favour of intervention are often considerable, as the costs of these types of crimes are often very high.

Despite this, there is currently a dearth of evidence on how best to treat people diagnosed with AsPD, and to date, the few reviews that have been carried out have been inconclusive and hampered by poor methodology. These issues were highlighted in Dolan and Coid’s extensive review of the treatment of psychopathy and AsPD (Dolan 1993). In our previous review of psychological interventions for this condition, Gibbon 2010, we found a lack of high‐quality evidence. The current NICE clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of AsPD rely heavily upon expert opinion and comment that "(a)lthough the evidence base is expanding, there are a number of major gaps..." (NICE 2010, p 9)

It had been hoped that since the last publication of this review, good‐quality studies had been conducted that addressed the methodological issues highlighted in Gibbon 2010, to address this important topic.

Objectives

To evaluate the potential benefits and adverse effects of psychological interventions for people with AsPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which participants were randomly allocated to an experimental group and a control group, where the control condition was either treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), waiting list or no treatment. We included all relevant RCTs, with or without blinding of the assessors, that were published in any language.

Types of participants

We included studies involving adult (18 years or over) men or women with a diagnosis of AsPD or dissocial personality disorder defined by the DSM (DSM‐IV; DSM‐IV‐TR; DSM‐5) and ICD‐10 diagnostic classification systems. We excluded studies of people with major functional mental illnesses (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder), organic brain disease, and intellectual disability. The decision to exclude persons with these conditions is based on the rationale that the presence of such disorders (and the possible confounding effects of any associated management or treatment) might obscure whatever other psychopathology (including personality disorder) might be present. However, we included studies of people diagnosed with AsPD who also had other comorbid personality disorders or other mental health problems. We placed no restrictions on setting and included studies with participants living in the community as well as those incarcerated in prison or detained in hospital settings. We included studies with subsamples of patients with AsPD provided that the data for this group were available separately. We also included studies where participants with a AsPD diagnosis comprised at least 75% of the sample. Lastly, we required studies where participants with antisocial or dissocial personality disorder formed a small subgroup to have randomised at least five people with AsPD.

Types of interventions

We included studies of psychological interventions, both group and individual‐based. This included, but was not limited to, interventions such as:

behaviour therapy;

cognitive analytic therapy (CAT);

cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT);

dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT);

psychodynamic psychotherapy;

transference‐focussed psychotherapy;

group psychotherapy;

mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT);

nidotherapy;

schema therapy;

social problem‐solving therapy;

therapeutic community (TC) treatment; and

contingency management.

We included studies of psychological interventions where medication was given as an adjunctive intervention to all groups but reported separately any studies where the comparison was directly between a psychological and a pharmacological intervention.

We only included studies where an intervention was compared to TAU, waiting list or no treatment. We did not include head‐to‐head trials that compared two or more psychological interventions directly with one another without an adequate control condition.

Types of outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcomes are listed below in terms of single constructs. Given the relatively stable nature of traits of AsPD (by definition), we chose outcomes that could be subject to change and that were potentially measurable by a variety of means (including self‐report and observation). Some traits, such as risk‐taking, are difficult to measure directly. Given the large negative impact of aggression and reconviction, we thought these particularly important; such outcomes could represent a final common pathway encompassing a variety of traits, including failure to confirm to social norms, deceitfulness, impulsivity, recklessness, irresponsibility and lack of remorse. These outcomes are also measurable by self‐report, psychometrics, observed behaviour, informant information and official records. We were also mindful of the issues described in DSM‐5 (p 659): “Because deceit and manipulation are central features of antisocial personality disorder, it may be especially helpful to integrate information acquired from systematic clinical assessments with information collected from collateral sources”. We anticipated that the studies included in this review would have used a range of outcome measures (for example, aggression could have been measured by a self‐report instrument or by an external observer). We provide examples of potential measures of each outcome; however, we also accepted other, similar ways of recording each outcome.

Primary outcomes

Aggression (trait aggression or state/dynamic/current aggression; reduction in aggressive behaviour or aggressive feelings; continuous or dichotomous outcome dependent upon how this was reported), measured through changes in scores on the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss 1992) for trait aggression, the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS; Malone 1994) for state aggression, or a similar, validated instrument; or as number of observed incidents.

Reconviction (continuous, dichotomous, or time‐to‐event outcome dependent upon how these data were reported), measured as reconviction in terms of the overall reconviction rate or numbers reconvicted for the sample (continuous), recidivism yes/no (dichotomous), or time to reconviction/reoffending (time‐to‐event data).

Global state/functioning (continuous outcome), measured through improvement on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) numeric scale (DSM‐IV‐TR).

Social functioning (continuous or dichotomous outcome dependent upon how this was reported), measured through improvement in scores on the Social Adjustment Scale‐Self‐Report (SAS‐SR; Weissman 1976), the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ; Tyrer 2005b), a similar, validated instrument, or a proxy measure of social functioning (e.g. decreased level of support required/time taken to achieve leave from hospital).

Adverse events (the incidence of overall adverse events and of the three most common adverse events; dichotomous outcome), measured as numbers reported.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life (self‐reported improvement in overall quality of life; continuous outcome), measured through improvement in scores on the European Quality of Life (EuroQol) instrument (EuroQoL Group 1990), or a similar, validated instrument.

Engagement with services (health‐seeking engagement with services; continuous outcome), measured though improvement in scores on the Service Engagement Scale (SES; Tait 2002), or a similar, validated instrument.

Satisfaction with treatment (continuous outcome), measured through improvement in scores on the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire‐8 (CSQ‐8; Attkisson 1982), or a similar, validated instrument.

Leaving the study early (dichotomous outcome), measured as proportion of participants discontinuing treatment.

Substance misuse (dichotomous outcome), measured as an improvement on the Substance Use Rating Scale Patient version (SURSp; Duke 1994), or a similar, validated instrument; or biological measurements of substance use (such as urine illicit drug testing). Where possible, we differentiated between drug misuse outcomes and alcohol misuse outcomes.

Employment status (continuous outcome), measured as number of days in employment over the assessment period or similar.

Housing/accommodation status (continuous outcome), measured as number of days living in independent housing/accommodation over the assessment period.

Economic outcomes (any economic outcome such as cost‐effectiveness; continuous outcome), measured using cost‐benefit ratios or incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

Impulsivity (state or trait impulsivity, self‐reported improvement in impulsivity; continuous outcome), measured through reduction in scores on the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS; Patton 1995), or a similar, validated instrument.

Anger (self‐reported improvement in anger expression and control; continuous outcome), measured through reduction in scores on the State‐Trait Anger Expression Inventory‐2 (STAXI‐II; Spielberger 1999), or a similar, validated instrument.

Mental state (continuous outcome): general mental state, such as ratings of general mental health symptoms, measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall 1962) or the Symptom Check List‐90 (SCL‐90; Derogatis 1973); or specific symptoms, such as dissociative experiences measured by the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES; Carlson 1993), mood/anxiety measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983), or the Beck Anxiety and Depression Scale (BADS; Beck 1988); or global mental health, measured by the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE‐OM; Barkham 2001).

Prison and service outcomes (for example, retention in community or prison programmes or use of resources such as hospital admission; continuous outcome), measured by trial authors.

Other outcomes measured in the included studies that did not fall into one of the above categories (continuous or dichotomous outcomes dependent upon how the outcomes were reported).

Whilst acknowledging that the nature of the disorder can lead to difficulty in long‐term follow‐up of individuals with AsPD, we reported relevant outcomes with no restriction on period of follow‐up. We divided outcomes into immediate (within six months), short‐term (> six months to 24 months), medium term (> 24 months to five years) and long‐term (> five years) follow‐up, where there were sufficient studies to warrant this.

Search methods for identification of studies

The searches for the previous version of this review were designed to find studies for a suite of reviews on a range of personality disorders. For this update, we revised the population section of the strategy by including only the search terms relevant to antisocial personality disorder. We also made changes to the databases we searched (see Differences between protocol and review).

Electronic searches

We ran searches in the following electronic databases and trial registers in September 2016, followed by top‐up searches in October 2017, October 2018 and September 2019.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 9) in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 5 September 2019).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to August Week 5 2019).

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations Ovid (searched 5 September 2019).

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print Ovid (searched 5 September 2019).

Embase OVID (1974 to 4 September 2019).

CINAHL Plus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 5 September 2019).

PsycINFO OVID (1967 to September Week 1 2019).

Science Citation Index Web of Science (1970 to 5 September 2019).

Social Sciences Citation Index Web of Science (1970 to 5 September 2019).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science Web of Science (1990 to 5 September 2019).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science & Humanities Web of Science (1990 to 5 September 2019).

Sociological Abstracts Proquest (1952 to 5 September 2019).

Criminal Justice Abstracts EBSCOhost (1910 to 5 September 2019).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2019, Issue 9), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 5 September 2019).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015, Issue 2. Final Issue), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 5 September 2019).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 5 September 2019).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx; searched 5 September 2019).

WorldCat (limited to theses; www.worldcat.org; searched 5 September 2019).

Detailed search strategies for each of these sources are provided in Appendix 1. The searches were designed to find records for two separate reviews of interventions for AsPD or dissocial personality disorder; a) psychological interventions and b) pharmacological interventions (Khalifa 2010). For this review, we selected only those studies that were relevant to psychological interventions.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of included and excluded studies for additional trials. We also examined bibliographies of systematic reviews identified in the search to identify relevant studies. We contacted the authors of relevant studies to enquire about other sources of information, and the first author or corresponding author of each included study for information regarding unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

In the following sections, we report only the methods that we were able to use in this review. We direct the reader to our protocol, Gibbon 2009, and Table 16, for information on additional methods that we intend to use in future updates of this review, should data permit.

5. Additional methods for future updates.

| Issue | Method |

| Types of interventions | We will consider widening the range of interventions examined in future reviews to include concepts such as 'Motivation to Change'. |

| Measures of treatment effect |

Continuous data We will summarise change‐from‐baseline ('change score') data alongside endpoint data where these are available. Change‐from‐baseline data may be preferred to endpoint data if their distribution is less skewed, but both types may be included together in meta‐analysis when using the MD (Higgins 2011a, p 270). Where the data are insufficient for meta‐analysis, we will report the results of the trial investigators' own statistical analyses comparing treatment and control conditions, using change scores. |

| Unit of analysis issues |

Cluster‐randomised trials Where trials use clustered randomisation, study investigators may present their results after appropriately controlling for clustering effects (robust standard errors or hierarchical linear models). If, however, it is unclear whether a cluster‐randomised trial has used appropriate controls for clustering, we will contact the study investigators for further information. If appropriate controls were not used, we will request individual participant data and re‐analyse these using multilevel models that control for clustering. Following this, we will conduct a meta‐analysis of effect sizes and standard errors in RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014), using the generic inverse method (Higgins 2011a). If appropriate controls were not used and individual participant data are not available, we will seek statistical guidance from the Cochrane Methods Group and external experts as to which method to apply to the published results in attempt to control for clustering. If there is insufficient information to control for clustering, we will enter the outcome data into RevMan5 (Review Manager 2014), using the individual as the unit of analysis, and then conduct a sensitivity analysis to assess the potential biasing effects of inadequately controlled clustered trials (Donner 2001). |

| Dealing with missing data | The standard deviations of the outcome measures should be reported for each group in each trial. If these are not given, we will calculate these, where possible, from standard errors, confidence intervals, t‐values, F values or P values using the method described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 7.7.3.3 (Higgins 2011a). If these data are not available, we will impute standard deviations using relevant data (for example, standard deviations or correlation coefficients) from other, similar studies (Follman 1992), but only if, after seeking statistical advice, to do so is deemed practical and appropriate. Assessment will be made of the extent to which the results of the review could be altered by the missing data by, for example, a sensitivity analysis based on consideration of 'best‐case' and 'worst‐case' scenarios (Gamble 2005). Here, the 'best‐case' scenario is where all participants with missing outcomes in the experimental condition had good outcomes, and all those with missing outcomes in the control condition had poor outcomes; the 'worst‐case' scenario is the converse (Higgins 2011a, section 16.2.2). We will report data separately from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow‐up. Where meta‐analysis is undertaken, we will assess the impact of including studies with attrition rates greater than 50% through a sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this group results in a substantive change in the estimate of effect of the primary outcomes, we will not add the data from these studies to trials with less attrition and will present them separately. Any imputation of data will be informed, where possible, by the reasons for attrition where these are available. We will interpret the results of any analysis based in part on imputed data with recognition that the effects of that imputation (and the assumptions on which it is based) can have considerable influence when samples are small. |

| Assessment of reporting biases | We will draw funnel plots (effect size versus standard error) to assess small study effects, when there are greater than 10 studies. Asymmetry of the plots may indicate publication bias, although they may also represent a true relationship between trial size and effect size. If such a relationship is identified, we will further examine the clinical diversity of the studies as a possible explanation (Egger 1997; Jakobsen 2014; Lieb 2016). |

| Data synthesis | For homogeneous interventions, we will group outcome measures by length of follow‐up, and use the weighted average of the results of all the available studies to provide an estimate of the effect of specific psychological interventions for people with antisocial personality disorder. We will use regression techniques to investigate the effects of differences in study characteristics on the estimate of the treatment effects. We will seek statistical advice before attempting meta‐regression. If meta‐regression is performed, it will be executed using a random‐effects model as per protocol. Where studies provide both endpoint or change data, or both, for continuous outcomes, we will perform meta‐analysis that combines both data types using the methods described by Da Costa 2013. We will consider pooling outcomes reported at different time points where this does not obscure the clinical significance of the outcome being assessed. To address the issue of multiplicity, future reviews should consider the following:

|

| Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity | We will undertake subgroup analysis to examine the effect on primary outcomes of:

|

| Sensitivity analysis | We will undertake sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the overall findings in relation to certain study characteristics. A priori sensitivity analyses are planned for:

|

MD= Mean difference

Selection of studies

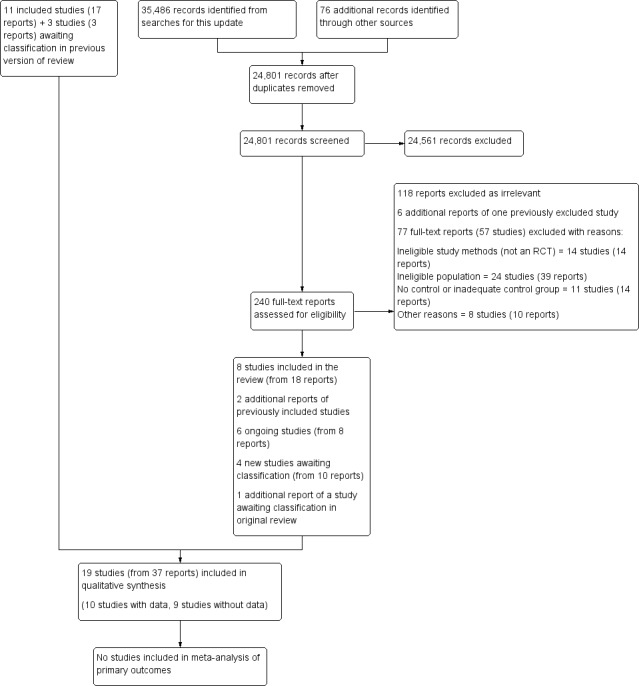

Working independently, two review authors read the titles and abstracts generated by the searches and discarded those that were clearly irrelevant. They next obtained the full‐text reports of those deemed potentially relevant or for which more information was need to determine relevance, and assessed them against the inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). The reviewers resolved uncertainties concerning the appropriateness of studies for inclusion in the review through consultation with a third review author who had not been involved in the initial screening. We recorded the selection process in a PRISMA diagram (Moher 2009).

For studies reported in a language other than English, we initially examined the English version of the title and abstract, before obtaining a translation of the full paper in order to reach a decision on its eligibility.

Data extraction and management

Four review authors extracted data independently for all studies using a data extraction form (which had previously been piloted) (see Appendix 2). Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted the study authors and asked them to supply the missing information. Two review authors entered the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014), which one review author checked for accuracy. Disagreements were resolved by consultation with a third review author; less than 5% of papers required such discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, two review authors independently completed Cochrane’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011b), resolving any disagreements through consultation with a third review author (from the same subgroup). We assessed the papers against the following domains: