Abstract

Background

Perineal pain is a common but poorly studied adverse outcome following childbirth. Pain may result from perineal trauma due to bruising, spontaneous tears, surgical incisions (episiotomies), or in association with operative vaginal births (ventouse or forceps‐assisted births). This is an update of a review last published in 2013.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy of a single administration of paracetamol (acetaminophen) used in the relief of acute postpartum perineal pain.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (9 December 2019), and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs, comparing paracetamol to placebo. We excluded quasi‐RCTs and cross‐over trials. Data from abstracts would be included only if authors had confirmed in writing that the data to be included in the review had come from the final analysis and would not change.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed each study for inclusion and extracted data. One review author reviewed the decisions and confirmed calculations for pain relief scores. We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

This update identified no new trials so the results remain unchanged. However, by applying the GRADE assessment of the evidence, the interpretation of main results differed from previous version of this review.

We identified 10 studies involving 2044 women, but all these studies involved either three or four groups, looking at differing drugs or doses. We have only included the 1301 women who were in the paracetamol versus placebo arms of the studies. Of these, five studies (482 women) assessed 500 mg to 650 mg and six studies (797 women) assessed 1000 mg of paracetamol. One study assessed 650 mg and 1000 mg compared with placebo and contributed to both comparisons. We used a random‐effects meta‐analysis because of the clinical variability among studies. Studies were from the 1970s to the early 1990s, and there was insufficient information to assess the risk of bias adequately, hence the findings need to be interpreted within this context. The certainty of the evidence for the two primary outcomes on which data were available was assessed as low, downgraded for overall unclear risk of bias and for heterogeneity (I² statistic 60% or greater).

More women may experience pain relief with paracetamol compared with placebo (average risk ratio (RR) 2.14, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.59 to 2.89; 10 trials, 1279 women), and fewer women may need additional pain relief with paracetamol compared with placebo (average RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.55; 8 trials, 1132 women). However, the certainty of the evidence was low, downgraded for unclear overall risk of bias and substantial heterogeneity.

One study used the higher dose of paracetamol (1000 mg) and reported maternal drug adverse effects. There may be little or no difference in the incidence of nausea (average RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.01 to 3.66; 1 trial, 232 women; low‐certainty evidence), or sleepiness (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.18 to 4.30; 1 trial, 232 women; low‐certainty evidence). No other maternal adverse events were reported.

None of the studies assessed neonatal drug adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

A single dose of paracetamol may improve perineal pain relief following vaginal birth, and may reduce the need for additional pain relief. Potential adverse effects for both women and neonates were not appropriately assessed. Any further trials should also address the gaps in evidence concerning maternal outcomes such as satisfaction with postnatal care, maternal functioning/well‐being (emotional attachment, self‐efficacy, competence, autonomy, confidence, self‐care, coping skills) and neonatal drug adverse effects.

Plain language summary

Paracetamol for relief of perineal pain after birth

What is the issue?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out if a single dose of paracetamol (acetaminophen) reduces the incidence of perineal pain for women after giving birth vaginally. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question (search date December 2019).

Why is this important?

The birth of a baby should be a very special time for women and families. Perineal pain can sometimes interfere with women's well‐being and cause them problems in looking after their babies.

The perineum is a diamond‐shaped area between the vagina and the anus that can bruise or tear as the baby is born. Some women are given a cut to the perineum (an episiotomy) for the baby to be born. Episiotomies and natural tears require stitches (sutures). Forceps or suction (ventouse) may also need to be used to help the baby to be born. Any such intervention can cause perineal discomfort and pain. Reducing the chance of perineal trauma and often intense perineal pain is clearly important as it can reduce a woman's ability to move around, breastfeed, and care for her baby. It can also cause urinary or fecal incontinence and painful sex. The pain can persist for weeks, months, or sometimes more. Adequate pain control is therefore important.

This review on paracetamol is part of a series of reviews looking at medicines to help relieve perineal pain in the first few hours after giving birth.

What evidence did we find?

We found no new studies in this update, so the review still includes 10 studies involving 1301 women. The studies were quite old, ranging from the 1970s to the early 1990s. All the studies looked at perineal pain relief associated with trauma, and no studies where the pain was associated with intact perineum were found. Overall, the evidence was of low quality due to the unclear methodology reported and the variation of findings.

Paracetamol may reduce the number of women experiencing pain at four hours after birth (10 trials, 1279 women), and fewer women may need additional pain relief with paracetamol (eight trials, 1132 women).

Only one study reported the number of women experiencing nausea (feeling sick) or sleepiness with no clear differences identified. There were no other side effects and none of the studies looked at effects on the babies.

What does this mean?

Paracetamol is generally effective as painkiller and causes few side effects. This review showed there may be some benefit specifically with a single dose of paracetamol for perineal pain after vaginal birth. Lactating women should be advised about the little information available on the effects of paracetamol in breastfed babies.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) compared to placebo for perineal pain in the early postpartum period.

| Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) compared to placebo for perineal pain in the early postpartum period | |||||||

| Patient or population: women with perineal pain following childbirth Setting: hospitals (mostly high‐income countries) Intervention: paracetamol (single administration, any dose) Comparison: placebo | |||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without paracetamol (single administration, any dose) | With paracetamol (single administration, any dose) | Difference | |||||

| Adequate pain relief as reported by women | RR 2.14 (1.59 to 2.89) | 1279 (10 RCTs) |

Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | ||

| 27.1% | 58.0% (43.1 to 78.4) | 30.9% more (16 more to 51.2 more) | |||||

| Additional pain relief | RR 0.34 (0.21 to 0.55) | 1132 (8 RCTs) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | — | ||

| 30.5% | 10.4% (6.4 to 16.8) | 20.1% fewer (24.1 fewer to 13.7 fewer) | |||||

| Maternal drug adverse effects (nausea) | RR 0.18 (0.01 to 3.66) | 232 (1 RCT) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | — | ||

| 1.8% | 0.3% (0 to 6.7) | 1.5% fewer (1.8 fewer to 4.9 more) | |||||

| Maternal drug adverse effects (sleepiness) | RR 0.89 (0.18 to 4.30) | 232 (1 RCT) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | — | ||

| 2.8% | 2.4% (0.5 to 11.8) | 0.3% fewer (2.3 fewer to 9.1 more) | |||||

| Neonatal drug adverse effects | — | — | — | — | Outcome not assessed | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias: none of the studies were low risk for selection bias, and only one out of 10 studies were low risk for either sequence generation or allocation concealment; the remainder were unclear. bDowngraded one level for inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity (I² statistic 60% or greater). cDowngraded one level for risk of bias: none of the studies were low risk for selection bias, and only two out of eight studies were low risk for either sequence generation or allocation concealment; the remainder were unclear. dDowngraded by two levels for imprecision: due to very wide confidence interval consistent with the possibility for benefit and the possibility for harm, and low number of events and/or participants.

Background

Description of the condition

The birth of a baby should be a joyous occasion for a woman and her family, but perineal pain after giving birth can sometimes interfere with this special time in women's lives. The perineum is a diamond‐shaped area between the vagina and the anus. Perineal pain is a common but poorly studied adverse outcome following childbirth. Pain may result from perineal trauma due to bruising, spontaneous tears, surgical incisions (episiotomies), or in association with operative births (ventouse or forceps‐assisted births).

Perineal trauma and the resultant perineal pain typically present in the immediate postpartum period. There are varying degrees of perineal trauma, with varying degrees of impact on women. Spontaneous trauma is classified as first‐degree tears (which may involve the skin and subcutaneous tissue or the vaginal mucosa, or both); second‐degree tears (which may involve superficial perineal muscles, the perineal body, and the deep perineal muscle); third‐degree tears (which involve the superficial or deep (or both) perineal muscles and the anal sphincter); and fourth‐degree tears (which involve the same structures as third‐degree tears but also included disruption of the external anal sphincter or internal anal sphincter (or both) and ano‐rectal epithelium) (Kettle 2004). Episiotomy is a surgical incision of the perineum to increase the diameter of the vaginal opening; these can be classified as mediolateral or posterolateral or midline (Kettle 2004).

Perineal pain on the first postpartum day has been reported in 97% of women with episiotomies, 95% of women with first‐ and second‐degree tears, and 75% of women who gave birth over an intact perineum in one study in Canada (Macarthur 2004). At one week, this reduced to 71% of women with episiotomies, 60% of women with first‐ and second‐degree tears, and 38% of women who gave birth over an intact perineum. At six weeks, the figures were 13% of women with episiotomies, 4% of women with first‐ and second‐degree tears, and 0% of women who gave birth over an intact perineum, and, in addition, the pain was reported as more severe where there was increased perineal trauma (Macarthur 2004). This pain, in the early days after giving birth, can be really intense and a deep unpleasantness may persist for weeks or months in some women (Greenshields 1993). It can interfere with the woman's ability to care for her baby and can also interfere with establishing breastfeeding as it is difficult for the woman to get comfortable to breastfeed.

In addition to the discomfort of perineal pain, the associated factors of prolonged decreased mobility, urinary or fecal incontinence, and dyspareunia may result in difficulty with childcare, integration in the family unit, and strain marital relationships (Andrews 2008). Chronic perineal pain is reported to be experienced by 32% of women who had an episiotomy or laceration at one year after giving birth (Williams 2007), and persists in 10% of women at 18 months (Carroli 1999). The aetiology, assessment, and management of chronic perineal pain should be differentiated from the acute pain that presents in the immediate postpartum period (up to six weeks after birth). This series of reviews focus on drugs to help with perineal pain in the immediate postpartum period, covering the first six weeks after birth.

Reducing the incidence of perineal trauma can be accomplished by certain changes in childbirth practices (i.e. episiotomies only when needed or avoiding the use of forceps), but these techniques continue to have a place in modern obstetrical care. Other interventions such as antenatal perineal massage have also been shown to decrease the likelihood of perineal trauma (mainly episiotomies) and the reporting of ongoing perineal pain (Beckmann 2006). There is continued debate as to whether women's positions during labour, how they push during birth, and immersion in water during labour may impact on perineal trauma and hence pain (Aasheim 2007; Cluett 2002; Gupta 2004; Lawrence 2009). Spontaneous lacerations and oedema resulting from childbirth will continue to occur and the need for adequate pain control will remain, although not all women with perineal pain will want to use drugs to relieve that pain as some will be concerned about the potential effect of such drugs on their baby via the breast milk. These women may look for other ways of helping to cope with the pain, such as cooling the perineum (East 2007), breastfeeding lying down, using a special cushion, etc. The type of suture material used and method of suturing chosen can also affect the amount of pain women experience, with absorbable synthetic materials associated with less pain than catgut (Kettle 1999), and continuous suturing technique associated with less pain than the interrupted method (Kettle 2007).

Description of the intervention

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is the major metabolite of two antipyretic drugs, acetanilide and phenacetin. Although it was first used as an analgesic and antipyretic in the 1880s, it was quickly discarded in favour of phenacetin and aspirin (introduced into medicine by Heinrich Dreser in 1899). Paracetamol was rediscovered at the end of the 1940s when the haematological adverse events first attributed to the drug were not demonstrated in purified preparations. By the mid‐1950s, it was marketed in the US and UK as preferable to aspirin since it was considered safe for children and people with ulcers to take. In 1963, paracetamol was added to the British Pharmacopoeia and has gained popularity since then as an analgesic agent with few adverse effects and little interaction with other pharmaceutical agents. It is an effective analgesic and antipyretic, even though its anti‐inflammatory effects are weaker than other medications. The dosage of paracetamol generally recommended for adults is 500 mg to 1000 mg every four to six hours as necessary, with a maximum of 4000 mg per 24‐hour period.

How the intervention might work

Perineal pain is transmitted primarily through the pudendal nerve, a somatic sensory and motor nerve that innervates the external genitalia, as well as sphincters for the bladder and the rectum (Cunningham 2005). While a detailed review of the mechanism of action and pharmacology of paracetamol is beyond the scope of this review, basic concepts are outlined below.

Debate exists about the primary site of action by which paracetamol induces analgesia (Smith 2009). Paracetamol does not have significant anti‐inflammatory properties, thus distinguishing it from the non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Burke 2008). It has been proposed that paracetamol had multiple interactions in the central nervous system within the eicosanoid, opioidergic, serotonergic, and cannabinoid systems (Smith 2009; Toms 2008).

Given orally, paracetamol has excellent bioavailability and its onset to action is 30 to 60 minutes. Paracetamol is primarily metabolised by the liver. It is generally well‐tolerated in therapeutic doses, but acute overdose (greater than 10 g) may result in liver toxicity and is potentially fatal.

Why it is important to do this review

Adequate pain control and its relationship to resumption of daily activities, improved rates of breastfeeding, ability to perform childcare duties, and a woman's general overall sense of well‐being have been inadequately studied. Perineal pain following childbirth is unique in that it is often a combination of pain from the incision and inflammatory pain, and there is a lack of research and clinical attention while remaining a major focus for mothers and their families. For breastfeeding mothers, it is also important to consider the neonatal safety profile of systemic medications. The adverse effects may include nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, and these may also affect the baby. The passage of these drugs through breast milk is of concern to lactating mothers.

Therapeutic ultrasound, rectal analgesia, topical anaesthetics, and cooling therapies are the subject of other Cochrane Reviews on interventions for reducing postpartum perineal pain (East 2007; Hay‐Smith 1998; Hedayati 2003; Hedayati 2005).

This review is one of a series of reviews on drugs for perineal pain in the early postpartum period, all based on the same generic protocol (Chou 2009). This protocol will be retained permanently on the Cochrane Library to describe the methods that shaped the production all the reviews on drugs for perineal pain, and is available for any new reviews to be undertaken on future drugs that may be introduced.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy of a single administration of paracetamol (acetaminophen) used in the relief of acute postpartum perineal pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs, comparing paracetamol to placebo. We excluded quasi‐RCTs and cross‐over trials. Data from abstracts would be included only if authors had confirmed in writing that the data to be included in the review had come from the final analysis and would not change.

Types of participants

Women with acute perineal pain in the early postpartum period after childbirth, that is the first four weeks after giving birth or as defined by the authors of the studies.

Types of interventions

All randomised comparisons of a single administration of paracetamol given for relieving perineal pain due to spontaneous lacerations, episiotomy, or vaginal birth over an intact perineum in the early postpartum period.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman (as determined by more than 50% relief of pain stated by the woman or calculated using a formula; see Data collection and analysis for details).

Additional pain relief.

Maternal drug adverse effects, composite of any of the following: nausea, vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, sleepiness, psychological impact.

Neonatal drug adverse effects, composite of any of the following: vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, sleepiness.

We obtained information regarding compatibility with breastfeeding from independent sources (Briggs 2008; Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) 2006; Kearney 2020), as the included studies did not assess adverse effects on babies.

Secondary outcomes

Prolonged hospitalisation due to pain.

Rehospitalisation due to perineal pain.

Fully breastfeeding at discharge.

Mixed feeding at discharge.

Fully breastfeeding at six weeks.

Mixed feeding at six weeks.

Perineal pain at six weeks.

Maternal views (using a validated questionnaire).

Maternal postpartum depression.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section was based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. We applied no language or date restrictions.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (9 December 2019).

The Register is a database containing over 25,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate the Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL; the list of hand searched journals and conference proceedings; and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, see pregnancy.cochrane.org/pregnancy-and-childbirth-groups-trials-register.

Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Two people screen the search results and review the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics) and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for unpublished, planned, and ongoing trial reports (9 December 2019) using the search methods detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

Data collection and analysis

Assessment of pain

The derived pain relief outcomes used were TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) over four to six hours or sufficient data provided to allow their calculation. The pain measures used for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were the five‐point pain relief (PR) scale with standard or comparable wording (none, slight, moderate, good, complete) or the four‐point pain intensity (PI) scale (none, mild, moderate, severe) or a visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain relief or pain intensity (Moore 1996).

We also accepted global evaluations of pain relief over four to six hours if measured on a five‐point scale by the participant and not the investigator. We extracted the data as dichotomous information (number of participants reporting good or excellent pain relief).

We used the number of participants who remedicated in the period of four to eight hours.

Data collection and analysis

From each study, we extracted: the number of women treated, the number of women who reported adequate pain relief, the mean TOTPAR or mean SPID, study duration, the dose of paracetamol, and information on adverse effects.

We calculated maximum pain relief as described by Cooper (Cooper 1991). For example, if the pain relief was evaluated six hours after administration and the scale used to assess pain was from 0 (no relief) to 4 (complete pain relief), the maxTOTPAR would be 6 × 4, or 24. We converted mean TOTPAR and mean SPID values to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991).

We used the following equations to estimate the proportion of participants achieving at least 50% maxTOTPAR:

proportion with greater than 50% maxTOTPAR = 1.33 × mean %maxTOTPAR – 11.5 (Moore 1997a);

proportion with greater than 50% maxTOTPAR = 1.36 × mean %maxSPID – 2.3 (Moore 1997b).

We converted the proportions to the number of participants achieving at least 50% maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. We used the number of participants with at least 50% maxTOTPAR to calculate relative benefit.

Selection of studies

In previous version of this review, two review authors (of EA, DC, and GG) independently assessed all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or by consulting a third person when required. The search identified no new trials for this update.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (DC and GG) extracted the data using the agreed data extraction form. We resolved discrepancies and confirmed calculations with the third review author (EA). GG entered data into Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014), and DC checked for accuracy.

Where studies reported pain relief using scales of pain intensity difference (SPID) or total pain relief (TOTPAR), we converted the continuous data to dichotomous data as described by Moore (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). See Table 2 and Table 3. We arbitrarily created a hierarchy (SPID, TOTPAR, investigators assessment).

1. Calculating 50% pain relief via SPID scores as described by Moore.

| Step 1 | Calculation of maximum % SPID | SPID%max = mean SPID × 100/(max score × no. of hours) |

| Step 2 | Moore formula | Proportion of participants with 50% pain = (1.36 × SPID%max) – 2.3 |

| Step 3 | Number with 50% pain | No = prop of participants with 50% pain × no of participants in group/100 |

max: maximum; SPID: sum of pain intensity difference.

Step 1 – reference Cooper 1991.

Step 2 – reference Moore 1997b.

2. Calculating 50% pain relief via TOTPAR scores as described by Moore.

| Step 1 | Calculation of maximum % TOTPAR | %maximum TOTPAR = mean TOTPAR × 100/(maximum score × number of hours) |

| Step 2 | Moore formula | Proportion of participants with 50% pain = (1.33 × mean %maximumTOTPAR) – 11.5 |

| Step 3 | Number with 50% pain | Number = proportion of participants with 50% pain × number of participants in group/100 |

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this update, two review authors (EA and YS) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion or by involving a third review author (GG).

1. Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

2. Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

3.1. Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

3.2. Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

4. Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion were reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to include missing data in the analyses undertaken.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; 'as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

5. Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all the study's pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study's pre‐specified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

6. Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by 1. to 5. above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

7. Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to 1. to 6. above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. For the overall risk of bias, we used guidance from the updated Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses – see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we presented the results as mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs when pooling data across studies if the outcomes were measured in the same way between studies. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine studies that measured the same outcome but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐RCTs for inclusion in this review. In future updates, if we identify any cluster‐RCTs we will include them in our analyses along with individually randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (16.3.3. in Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial, or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually randomised trials, we will synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a Sensitivity analysis to investigate its effects.

Cross‐over trials

Given the nature of the intervention and condition, we excluded cross‐over trials.

Multiple‐armed trials

We identified and included one trial with three relevant treatment and control arms (Hopkinson 1974). We divided the results of the control group to compare against each treatment group in two single pair‐wise comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

We noted the levels of attrition for included studies. In future updates, if we identify any studies with high levels of missing data, we will conduct a Sensitivity analysis to assess this on overall treatment effect.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

For all outcomes, we aimed to analyse the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis (i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses). The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing ('available‐case' analysis).

We analysed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. If participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there was sufficient information in the original trial report, we would have attempted to restore them to the correct group.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I², and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if Tau² was greater than zero and the I² statistic was:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity;

or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Where we used a random‐effects model and there was heterogeneity, we reported the mean RR, or mean MD or mean standard MD.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were 10 or more studies in a meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. In future updates, we will use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes, we will use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes, we will use the tests proposed by Harbord 2006.

Where we suspected reporting bias (see Selective reporting (reporting bias)), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we would have explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results using a Sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We used random‐effects model given the clinical variability detected, particularly in relation to the different therapeutic schemes and ways of assessing pain relief. In addition, we decided to present the results as the average treatment effect and its 95% CI or 95% prediction intervals(Higgins 2009) which account for both the uncertainty in estimating the population mean plus the random variation of the individual values.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it by performing subgroup analyses (Deeks 2001).

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

primiparous versus multiparous women;

women with perineal trauma versus women who gave birth over intact perineum;

dose of paracetamol: less than 1000 mg single dose, 1000 mg single dose, or more than 1000 mg single dose.

However, there were insufficient data to undertake proposed subgroup analyses for parity or type of trauma.

In future updates, we will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within Review Manager 2014 and report the results of planned subgroup analysis along with the Chi² statistic and P value as well as the I² statistic.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of risk of bias for important outcomes in the review. Where there was risk of bias associated with a particular risk of bias domain (e.g. inadequate allocation concealment), this would have been explored by a Sensitivity analysis. All the included studies had an overall unclear risk of bias so this was not possible.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Assessment of the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update, we assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the certainty of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes (maximum of seven) for the main comparisons (gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html).

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman.

Additional pain relief.

Maternal drug adverse effects, composite of any of the following: nausea, vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, sleepiness, psychological impact.

Neonatal drug adverse effects, composite of any of the following: vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, sleepiness.

We used GRADEpro GDT (www.guidelinedevelopment.org/) to import data from Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) in order to create a 'Summary of findings' table. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of certainty for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence from RCTs can be downgraded from high quality by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

For more information see Characteristics of included studies table

Results of the search

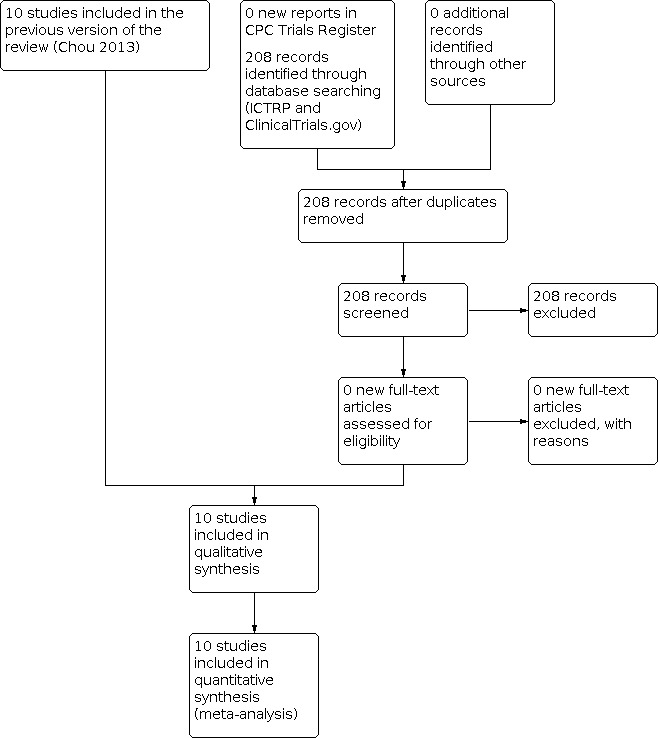

See: Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

The search for the first version of the review was based on the generic protocol (Chou 2009), thus studies identified were for all drugs for perineal pain (which explains the large number of reports identified). The search resulted in 135 reports and included 10 studies with data for the review (from 11 reports). The updated searches in November 2012 and December 2019 were for studies relevant to the scope of this review and retrieved no new studies.

Included studies

We included 10 studies (from 11 reports) that provided data for this review (Behotas 1992; Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Levin 1974; Melzack 1983; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Smith 1975; Sunshine 1989a).

Sample sizes

Included trials involved 2044 women in total, of whom 1301 were allocated to either paracetamol or placebo. We included details for each trial in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Setting

Nine of the 10 studies were conducted in high‐income countries, seven studies were in the USA (Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Levin 1974; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Smith 1975), and one in each of France (Behotas 1992) and Canada (Melzack 1983). The only study from a low‐ or middle‐income country was conducted in Venezuela and recruited 125 women in the paracetamol and placebo arms (Sunshine 1989a). Nine study reports were published in English, and Behotas 1992 was published in French. All included trials were small; the largest study recruited 250 women in the paracetamol and placebo arms.

Trial dates

Five trials were published in the 1970s, four in the 1980s, and the most recent in 1992. However, none of the studies reported the dates that the trials were conducted.

Participants

All trials evaluated treatment for perineal pain following childbirth. There was no distinction between episiotomy and spontaneous lacerations made when presenting results. We found no trials evaluating perineal pain relief after vaginal birth with intact perineum. None of the trials described the women who met the study eligibility criteria, but were not randomised.

Interventions and comparisons

All studies reported outcomes following a single administration of paracetamol and some were multi‐arm trials which compared paracetamol to other analgesics alone or in combination, and to placebo. For this review, we extracted only data from the paracetamol versus placebo arms. Assessment of effectiveness compared with other drugs or combinations of drugs is considered in other reviews based on and listed in the generic protocol (Chou 2009).

The studies included two different doses of paracetamol: five studies (361 women) assessed paracetamol 500 mg to 650 mg (Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Levin 1974; Melzack 1983; Sunshine 1989a); and six studies (814 women) assessed paracetamol 1000 mg (Behotas 1992; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Smith 1975). One study had three arms and compared two different doses of paracetamol with placebo; paracetamol 650 mg (88 women), paracetamol 1000 mg (87 women), and placebo (88 women) (Hopkinson 1974).

Outcomes

Seven studies assessed pain‐related outcomes up to four hours after medication administration (Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Levin 1974; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Smith 1975). Two studies assessed outcomes up to six hours (Behotas 1992; Sunshine 1989a), and one study assessed outcomes up to 12 hours (Melzack 1983). The variety of ways of assessing pain relief suggested we should be using a random‐effects model for pooling the data. Therefore, we reported the mean effect across studies and not a best estimate of effect.

Sources of trial funding

Eight studies did not report sources of trial funding (Behotas 1992;Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976;Levin 1974; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Smith 1975). Merck Frosst Canada Inc. supported Melzack 1983 with a grant, and Richardson‐Vicks, Inc. Shelton Connecticut (pharmaceuticals section) partially supported Sunshine 1989a with a grant.

Trial authors' declarations of interest

None of the studies reported trial authors' declarations of interest.

Was informed consent obtained from the trial participants?

Five trials reported participant‐informed written consent (Behotas 1992; Melzack 1983; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Sunshine 1989a). Three trials reported having obtained ethical approval for the trial (Behotas 1992; Schachtel 1989; Sunshine 1989a). The other seven trials did not mention Review Board ethical approvals.

Excluded studies

We excluded 112 studies (from 121 reports), mostly because they assessed another drug for relief of perineal pain or they were not RCTs. We wrote to authors to request information about six studies (Beaver 1980; Bloomfield 1985; Lasagna 1967; Laska 1983; Noveck 1983; Visanto 1980). We received responses from Bloomfield 1985 and Laska 1983. We excluded three of these studies because the aetiology of postpartum pain was not clearly defined (Lasagna 1967), or studies included women with pain other than from the perineum (Beaver 1980; Laska 1983). We excluded three studies because of our inclusion criterion that we would only include data from conference abstracts if "…authors have confirmed in writing that the data to be included in the review have come from the final analysis and will not change" was not fulfilled (Bloomfield 1985; Noveck 1983; Visanto 1980). For details see Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Most of the included studies did not clearly document complete details of their methodology. Hence, we judged many of 'Risk of bias' assessments as unclear (Figure 2). Therefore, our findings should be interpreted in this context.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

With the exception of one study that demonstrated adequate sequence generation (Schachtel 1989), there was no detail on how the randomisation sequence was generated or how women were allocated to groups in the other studies. For allocation concealment, Hopkinson 1973 reported that stock medication bottles were coded for each treatment group, and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. Rubin 1984 reported that treatments were provided in a two‐caplet dose dispensed from precoded vials whose content were unknown to both the woman and the observer. The remainder of the included studies were unclear with respect to allocation concealment. Overall, there were some concerns over selection bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

Although all the included trials were described as double‐blind, two studies did not describe how blinding was achieved (Levin 1974; Schachtel 1989). Behotas 1992 placed treatments in identical white containers, but provided no information about the characteristics and appearance of the drugs. Six trials reported that medications were prepared in identical‐appearing capsules (Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Rubin 1984; Smith 1975; Sunshine 1989a). Melzack 1983 described that capsules were identical in appearance, and were capsule‐shaped, odourless, peach‐coloured, and film‐coated. Overall, there were some concerns over performance bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

All included trials were described as double‐blind. Two studies were judged at low risk of detection bias (Hopkinson 1973; Rubin 1984). This was unclear for the remainder of the studies. Overall, there were some concerns over detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged four studies at low risk for providing incomplete outcome data (Hopkinson 1973; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Sunshine 1989a), and three studies at high risk due to the high and disproportionate withdrawal rates among groups (Behotas 1992; Melzack 1983; Smith 1975). For the remainder of the studies, attrition bias was unclear. Overall, we believe there was high risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

We judged all studies as unclear with respect to reporting bias as trial protocols were not available and so we were unable to assess this domain adequately. Of note, all outcomes mentioned in the method sections were reported. Overall, there were some concerns over reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

There was insufficient information to assess other potential biases in the included studies. Overall, we had some concerns over other biases.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Studies covered paracetamol in doses of 600 mg (Levin 1974), 650 mg (Hopkinson 1973; Hopkinson 1974; Melzack 1983; Sunshine 1989a), and 1000 mg (Behotas 1992; Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Rubin 1984; Schachtel 1989; Smith 1975).

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

More women may experience adequate pain relief four or six hours after giving birth in the paracetamol group compared with women in the placebo group (average RR 2.14, 95% CI 1.59 to 2.89; 110 trials, 279 women; low‐certainty evidence, Table 1). Pooled results showed statistical heterogeneity at four hours (Tau² = 0.16; Chi² P = 0.0001, I² = 72%; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 1: Adequate pain relief as reported by women

Additional pain relief

Fewer women may have need of additional pain relief during the study period in the paracetamol group compared to the placebo group (average RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.55; 8 trials, 1132 women; low‐certainty evidence, Table 1). Pooled results showed statistical heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.32, Chi² P = 0.001, I²= 69%; Analysis 1.2). We also calculated the 95% prediction intervals for the underlying effect (95% prediction interval was 0.08 to 1.54); this indicates that a new observation in any future studies will fall within this range and the underlying RR may be greater than 1 in an individual study due to the between‐study heterogeneity.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 2: Additional pain relief

Subgroup analysis based on paracetamol doses (paracetamol 500 mg to 650 mg versus paracetamol 1000 mg) indicated that both doses were effective. However, women who received paracetamol 1000 mg (see Analysis 1.1) were as likely to request additional doses of analgesia as women who received paracetamol 500 mg to 650 mg (see Analysis 1.2).

Maternal drug adverse effects

Only one study using the higher dose of paracetamol 1000 mg reported maternal adverse effects. There may be little or no difference in the occurrence of nausea (average RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.01 to 3.66; 1 trial, 232 women; low‐certainty evidence; Table 1; Analysis 1.3) or sleepiness (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.18 to 4.30; 1 trial, 232 women; low‐certainty evidence; Table 1; Analysis 1.4). The study did not report vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, or psychological impact.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 3: Maternal drug adverse effects (nausea)

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 4: Maternal drug adverse effects (sleepiness)

Neonatal drug adverse effects

None of the studies reported neonatal adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes

None of the studies reported our pre‐specified secondary outcomes (prolonged hospitalisation due to pain, rehospitalisation due to perineal pain, fully breastfeeding at discharge, mixed feeding at discharge, fully breastfeeding at six weeks, mixed feeding at six weeks, perineal pain at six weeks maternal views (using a validated questionnaire), or maternal postpartum depression).

Study outcomes not prespecified in the review

Compared with placebo, it is uncertain whether paracetamol makes a difference in bowel movements (average RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.86; 1 trial, 263 women; Analysis 1.6) or gastric discomfort (average RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.47; 1 trial, 150 women; Analysis 1.7) because of single, small studies at moderate risk of bias contributing to the analyses.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 6: Maternal bowel movements (not prespecified)

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 7: Maternal gastric discomfort (not prespecified)

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review includes women in the immediate postpartum period who were treated with a single dose of paracetamol 500 mg to 650 mg, and with a single dose of paracetamol 1000 mg. Most of these women were experiencing pain due to an episiotomy.

The evidence suggests that paracetamol may be more effective than placebo for the relief of postpartum perineal pain and the need for additional analgesia in women randomised to placebo, but the certainty of the evidence was low, downgraded for unclear risk of bias and inconsistency. Hence, probably the degree of effectiveness remains uncertain. There was little information regarding adverse effects reported by women who received paracetamol for perineal pain. None of the trials reported adverse effects of paracetamol for the baby.

There was insufficient evidence to assess the safety or compatibility of paracetamol with breastfeeding. We reviewed the following information from other sources (Briggs 2008; Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) 2006; Kearney 2020). Although a single case of a rash on the upper trunk of a breastfeeding baby has been described, the American Academy of Pediatrics considers paracetamol compatible with breastfeeding. No other adverse effects of paracetamol exposure through breast milk have been reported in babies born at term. Following the mother's treatment with paracetamol 1000 mg, it has been estimated that the maximum dose her baby is exposed to is less than 2% of the maternal dose (Briggs 2008).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A single dose of paracetamol for perineal pain in the postpartum period may be effective although the certainty of the evidence was low, and the amount of data was limited. Furthermore, the included trials did not assess many of the pre‐specified outcomes. There are no empirical data to evaluate the effect of paracetamol versus placebo on outcomes that might affect a mother's ability to care for her baby (maternal sedation, psychological impact, prolonged hospitalisation, breastfeeding, postpartum depression) or neonatal outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

The overall certainty of the trials included in this review was generally unclear. This can be attributed to these studies being performed before the requirement to report sufficient information that would allow assessment of the rigour of the study (Begg 1996). Two studies were at low risk of bias (Hopkinson 1973; Rubin 1984), three were moderate (Hopkinson 1974; Hopkinson 1976; Schachtel 1989), and five were high (Behotas 1992; Levin 1974; Melzack 1983; Smith 1975; Sunshine 1989a) (Figure 2).

The certainty of the evidence for primary outcomes was low due to overall unclear risk of bias and substantial heterogeneity (I² statistic 60% or greater).

Potential biases in the review process

The evidence in this review was derived from studies identified in a detailed search process. However, it is possible that additional trials comparing the use of paracetamol versus placebo have been performed but not published, as shown in the asymmetric funnel plot for additional pain relief outcome (Figure 3).

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Additional pain relief.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of a Cochrane Review on single‐dose paracetamol for postoperative pain in adults experiencing pain due to episiotomy, caesarean section, and minor gynaecological/orthopaedic/general surgery procedures (51 studies, 5762 participants) indicated that paracetamol was effective for about half of the participants and the incidence of adverse effects was low (Toms 2008).

One study in our review (Hopkinson 1974) was included in one meta‐analysis of direct comparisons of different doses of pain relievers in analgesic studies (McQuay 2007). In that analysis, pooled comparison of paracetamol 1000 mg was superior to paracetamol 500 mg for the relief of pain (relative benefit 1.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.4; 7 studies, 933 participants).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

A single dose of paracetamol (either 650 mg or 1000 mg) may be effective for reducing the incidence of perineal pain after childbirth, although the evidence from this review on adequate pain relief and need for additional pain relief is of low certainty, probably indicating uncertainty on the magnitude of effect. Paracetamol has already been shown to be an effective analgesic in general (Toms 2008).

Although data on adverse effects on mothers are sparse, and no evidence is reported on adverse effects on babies, there does not appear to be any significant increase in side effects when used as directed. Additionally, the available evidence from other sources suggests that the quantity of the drug that passes into milk in full‐term healthy breastfed infant is small, and it also has a relatively short elimination half‐life.

Information of the effectiveness of paracetamol compared with other drugs for perineal pain relief is addressed in other reviews (Chou 2009). No studies evaluated the use of paracetamol in women with intact perineum.

Women who use paracetamol should take care not to use other medications that contain paracetamol at the same time, as that may inadvertently lead to overdose and toxicity. The studies included in our review reported no significant adverse events. However, excessive doses of paracetamol are associated with liver toxicity. Both dosages of paracetamol used in this review were therapeutic and did not approach 'toxic doses'. However, reports of accidental paracetamol overdose have been reported when individuals used several medications containing paracetamol concurrently (e.g. 'cold remedies'), many of which are available without prescription.

Implications for research.

Future studies may be conducted to determine the efficacy of multiple doses of paracetamol compared with placebo, and additional trials of good methodological quality comparing other therapeutic schemes are desirable. To date, trials focused on pain relief, but they should also address the gaps in evidence concerning maternal outcomes such as satisfaction with postnatal care, maternal functioning/well‐being (emotional attachment, self‐efficacy, competence, autonomy, confidence, self‐care, coping skills), and importantly, neonatal adverse effects.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 December 2019 | New search has been performed | Search updated and no new trials identified. |

| 9 December 2019 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | No new trials have been added for this update. We updated the overall presentation of the review as per current Cochrane standards (Higgins 2011), including the risk of bias for all studies. By applying the assessment of the certainty of the evidence for each important outcome, interpretation of results differed from the previous version of this review, and conclusions changed. We added the study flow diagram (Figure 1), the funnel plots for two primary outcomes (Figure 11 and Figure 3), and the GRADE 'Summary of findings' table (Table 1). |

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Adequate pain relief as reported by women.

History

Review first published: Issue 3, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 November 2012 | New search has been performed | Search updated. |

| 6 November 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new trial reports identified by the updated search. |

Notes

Other reviews on this topic based on the generic protocol (Chou 2009):

aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid, ASA);

non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAID);

opiates (oral and parenteral);

anaesthetics;

homoeopathic medications;

drug combinations.

An overview will be written when the results of the other six reviews are available.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Drs Bloomfield and Laska who responded to our requests for additional information.

We wish to thank for following for translating papers: Alison Ledward (for Behotas 1992), Rachel Forman (for Moggian 1972 and Pitton 1982), Anne‐Marie Grant (for Petho 1981), Lianne Kennedy (for Azpiroz 1971), and Gillian Kenyon and Andreas Schwab (for Szabados 1986).

We wish to thank Monica Chamillard, Julia Pasquale, and Virginia Díaz for their help in creating the 'Summary of findings' table.

As part of the prepublication editorial process, this review has been commented on by five peers (an editor and four referees who are external to the editorial team), and the Group's Statistical Adviser. The authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Farida Elshafeey; Luke Grzeskowiak, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia; Dr Eleanor Jones, Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, UK; and another peer reviewer who wishes to remain anonymous.

We wish to thank Doris Chou and Metin Gülmezoglu for their contributions as authors on earlier versions of this review.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Evidence Synthesis Programme funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Evidence Synthesis Programme, the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS) or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods for ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov

ICTRP

(searched with synonyms and each line was searched separately)

perine* AND pain AND postpartum

perine* AND pain AND postnatal

pain AND episiotomy

ClinicalTrials.gov

Advanced search

Interventional Studies | episiotomy pain

Interventional Studies | perineal pain

pain | Interventional Studies | perineum

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Adequate pain relief as reported by women | 10 | 1279 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.59, 2.89] |

| 1.1.1 Paracetamol 500 ‐ 650 mg | 5 | 482 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [1.20, 2.87] |

| 1.1.2 Paracetamol 1000 mg | 6 | 797 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.42 [1.53, 3.81] |

| 1.2 Additional pain relief | 8 | 1132 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.21, 0.55] |

| 1.2.1 Paracetamol 500 ‐ 650 mg | 3 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.17, 0.53] |

| 1.2.2 Paracetamol 1000 mg | 6 | 815 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.19, 0.67] |

| 1.3 Maternal drug adverse effects (nausea) | 1 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.01, 3.66] |

| 1.3.1 Paracetamol 500 ‐ 650 mg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.3.2 Paracetamol 1000 mg | 1 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.01, 3.66] |

| 1.4 Maternal drug adverse effects (sleepiness) | 1 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.18, 4.30] |

| 1.4.1 Paracetamol 500 ‐ 650 mg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.4.2 Paracetamol 1000 mg | 1 | 232 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.18, 4.30] |

| 1.5 Neonatal drug adverse effects | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.6 Maternal bowel movements (not prespecified) | 1 | 263 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.54, 1.86] |

| 1.6.1 Paracetamol 500 ‐ 650 mg | 1 | 132 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.44, 2.66] |

| 1.6.2 Paracetamol 1000 mg | 1 | 131 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.40, 2.18] |

| 1.6.3 Paracetamol 1500 mg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.7 Maternal gastric discomfort (not prespecified) | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.57, 2.47] |

| 1.7.1 Paracetamol 500 ‐ 650 mg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.7.2 Paracetamol 1000 mg | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.57, 2.47] |

| 1.7.3 Paracetamol 1500 mg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Paracetamol (single administration, any dose) versus placebo, Outcome 5: Neonatal drug adverse effects

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Behotas 1992.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT 3 groups (ibuprofen; paracetamol; placebo) |

|

| Participants | 90 women with episiotomy pain needing analgesia | |

| Interventions | Intervention: paracetamol 1000 mg (n = 28) Comparison: placebo (n = 31) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 hours. For the review, we reported 4‐hour assessment. Study translated by Alison Ledward. Dates of study: not reported Setting: Sainte‐Antoine Hospital, Paris Funding sources: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported Participant's written consent: yes Review board approval: yes |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomise…" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomise…" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "…double blind…" "all 3 treatments were placed in identical white container." No further details. Insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjective evaluation of pain relief. Adverse events were noted." Insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Exclusion of participants after randomisation:

'Withdrawal' in the context of this study was taken to mean that the women requested alternative pain relief. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on baseline data comparisons. No other information. |

Hopkinson 1973.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT 4 groups (paracetamol; propoxylene hydrochloride; paracetamol + propoxylene hydrochloride; placebo) |

|

| Participants | 200 women with moderate‐to‐severe episiotomy pain | |

| Interventions | Intervention: paracetamol 650 mg (n = 50) Comparison: placebo (n = 50) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours. For the review, we reported 4‐hour assessment. Dates of study: not reported Setting: in hospital. Authors from Obstetrical and Gynecological Services, Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, Pennsylvania, USA Funding sources: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported Participant's written consent: not reported Review board approval: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomly assigned…" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "…Stock medication bottles which were coded for each treatment group…" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The study was conducted under double‐blind conditions. Neither investigator, the patient, nor the nursing staff knew which medication was being administered. All medications were prepared in identical‐appearing capsules." Comment: blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Subjective evaluation of pain relief. Neither investigator, the patient, nor the nursing staff knew which medication was being administered. The investigator rated the overall success of the medication…" Comment: blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No exclusions reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on baseline data comparisons. No other information. |

Hopkinson 1974.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT 3 groups (paracetamol 1000 mg; paracetamol 650 mg; placebo) |

|

| Participants | 263 women with moderate‐to‐severe episiotomy pain | |

| Interventions | Intervention 1: paracetamol 1000 mg (n = 87) Intervention 2: paracetamol 650 mg (n = 88) Comparison: placebo (n = 88) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours. For the review, we reported 4‐hour assessment. Dates of study: not reported Setting: authors from Obstetrical and Gynecological Services, Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, Pennsylvania, USA Funding sources: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported Participant's written consent: not reported Review board approval: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomly assigned…" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomly assigned…" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "…double blind…" "The patients were randomly assigned to three medication groups, each group receiving a single dose of two identical‐appearing capsules containing 500 mg of acetaminophen, 325 mg of acetaminophen, or placebo…" Comment: no further details. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Subjective evaluation of pain relief. Quote: "The patients' estimate of pain intensity and relief from pain were elicited by interview. Additionally, a global evaluation reflecting the investigator's clinical impression of the overall therapeutic response was recorded." Comment: insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Women who required additional medication were considered treatment failures. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on baseline data comparisons. No other information. |

Hopkinson 1976.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT 3 groups (paracetamol; paracetamol + propoxylene; placebo) |

|

| Participants | 224 women with moderate‐to‐very severe episiotomy pain | |

| Interventions | Intervention: paracetamol 1000 mg (n = 75) Comparison: placebo (n = 75) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours. For the review, we reported 4‐hour assessment. Dates of study: not reported Setting: authors from Obstetrical and Gynecological Services, Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, PA, USA Funding sources: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported Participant's written consent: not reported Review board approval: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…assigned randomly…" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…assigned randomly…" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "…double blind…The patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group. Drugs were administered in identical‐appearing capsules." No further details. Insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Subjective evaluation of pain relief. Quote: "A post‐treatment global evaluation of the patients' response to study drug was made at the end of 4 hours by the investigators." Comment: insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Reported as similar baseline data for age and weight, but no other parameters. |

Levin 1974.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT; 2 centres 4 groups (paracetamol; codeine; paracetamol + codeine; placebo) |

|

| Participants | 137 women with moderate‐to‐severe episiotomy pain | |

| Interventions | Intervention: paracetamol 600 mg (n = 34) Comparison: placebo (n = 35) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours. For the review, we reported 4‐hour assessment. Dates of study: not reported Setting: authors from Obstetrics and Gynecology Departments in 2 hospitals in USA; Methodist Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, USA and Washington Center, Washington, DC, USA Funding sources: not reported Declarations of interest: not reported Participant's written consent: not reported Review board approval: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomly assigned…" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…randomly assigned…" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "…double blind…" "Patients were randomly assigned to one of four treatments groups (capsules containing codeine phosphate, codeine phosphate plus acetaminophen, acetaminophen, or placebo." No further details. Insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Subjective evaluation of pain relief and drug‐related adverse effects. Quote: "Each patient was interviewed about the response to medication…" No further details. Insufficient information to permit a judgement. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | We did not assess the trial protocols. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

Melzack 1983.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT 3 groups (diflunisal; paracetamol; placebo) |

|

| Participants | 90 women with moderate‐to‐severe episiotomy pain | |

| Interventions | Intervention: paracetamol 650 mg (n = 30) Comparison: placebo (n = 30) |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Outcomes assessed at 0, 30, 60, 90 minutes then hourly from 2 to 12 hours. For the review, we reported 4‐hour assessment. Dates of study: not reported Setting: authors from Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Canada Funding sources: supported by a grant from Merck Frosst Canada Inc. Declarations of interest: not reported Participant's written consent: yes Review board approval: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…an allocation of random numbers…" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "…an allocation of random numbers…" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "The procedure was a…double‐blind, parallel, single‐dose comparison of three treatment groups." "The patients were assigned randomly to three study groups to receive a single dose of four capsules identical in appearance, and were capsule‐shaped, odourless, peach‐coloured, and film‐coated." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjective evaluation of pain relief and adverse effects noted by experimenters. In addition to the evaluation listed above, each patient was administered a pain questionnaire." No further details. Insufficient information to permit a judgement. |