Abstract

Evidence in mouse models for Down syndrome (DS) and human fetuses with DS clearly shows severe neurogenesis impairment in various telencephalic regions, suggesting that this defect may underlie the cognitive abnormalities of DS. As cerebellar hypotrophy and motor disturbances are part of the clinical features of DS, the goal of our study was to establish whether these defects may be related to neurogenesis impairment during cerebellar development. We found that in fetuses with DS (17–21 weeks of gestation) the cerebellum had an immature pattern, a reduced volume and notably fewer cells (−25%/−50%) in all cerebellar layers. Immunohistochemistry for Ki‐67, a marker of cycling cells, showed impaired proliferation (−17%/−50%) of precursors from both cerebellar neurogenic regions (external granular layer and ventricular zone). No differences in apoptotic cell death were found in DS vs. control fetuses. The current study provides novel evidence that in the cerebellum of DS fetuses there is a generalized hypocellularity and that this defect is due to proliferation impairment, rather than to an increased cell death. The reduced proliferation potency found in the DS fetal cerebellum, in conjunction with previous evidence, strengthens the idea that the trisomic brain is characterized by widespread neurogenesis disruption.

Keywords: cerebellum, mental retardation, neurogenesis, trisomy 21

INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome (DS) is a high‐incidence genetic disease caused by the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21 (28). It is characterized by numerous somatic abnormalities such as heart and gastrointestinal defects, immunological and pulmonary diseases, dermatological problems, epilepsy, ophthalmological and hearing problems, and obesity. Though these defects may be inconsistent in their occurrence, mental retardation is the invariable and most severe problem affecting individuals with DS 25, 28, 31. Numerous reports have shown that the brains of individuals with DS are smaller in size compared with those of normal individuals, which strongly suggests a causal link between intellectual disability and brain hypotrophy 2, 3, 13, 23, 26, 37, 40, 47, 49, 54, 55.

The fact that brain hypotrophy is already present in fetuses and children with DS and is associated with hypocellularity and cortical dysplasia 15, 36, 55 suggests that neurogenesis alterations during the earliest and most critical stages of brain development may underlie brain hypotrophy of individuals with DS. This hypothesis has been validated by recent data in mouse models for DS 5, 8, 19, 24, 32, 33, 38, clearly showing that neurogenesis is notably reduced in the ventricular and subventricular zone, two neurogenic regions that give origin to neuronal and glial cells destined to the cortical mantle (6), the cerebellum and hippocampus. Because of the obvious obstacle inherent in using human material, there are very few studies that have examined neurogenesis in fetuses with DS. In a comparative study in the Ts65Dn mouse and in human fetuses with DS, we have shown that in fetuses with DS there is a strong neurogenesis reduction in the dentate gyrus, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus and ventricular germinal matrix 10, 16. This validates data obtained in mouse models and provides compelling evidence that neurogenesis alterations represent a crucial developmental problem in DS.

It has been recognized for many years that cerebellar abnormalities are frequently observed in association with DS; infants, children and adults with DS are characterized by smaller cerebellar size 17, 22, 26, 37, 51, 54. The fact that neurogenesis is severely impaired in various brain regions of mouse models for DS as well as in human fetuses with DS and the demonstration that growth disturbance of the cerebellum is already present in second‐trimester fetuses with DS (37) strongly suggests that the cerebellar hypoplasia of subjects with DS is underpinned, similarly to that of other brain regions, by impairment of neurogenesis during cerebellar development. As there is a lack of direct demonstration that this is the case, the goal of our study was to establish whether the cerebellum of human fetuses with DS is characterized by neurogenesis defects and hypocellularity. There are no therapies to correct brain alterations in DS. Demonstration that the leading factor of microencephaly in DS is a widespread neurogenesis reduction during fetal life rather than late‐occurring neurodegeneration would provide the basis on which to focus subsequent investigations on the cellular mechanisms underlying neurogenesis alterations. The identification of these mechanisms may provide a rational starting point for attempting to ameliorate neurogenesis using pharmacological approaches.

METHODS

Subjects

For this study we used fetuses between 17 and 21 gestational weeks (GW). Brains were obtained after prior informed consent from the parents and according to procedures approved by the Ethical Committee of the St. Orsola‐Malpighi Hospital, Bologna, Italy. Regulations of the Italian Ministry of Health and the policy of Declaration of Helsinki were followed. All fetuses derived from legal abortion and were collected with an average post‐mortem delay of approximately 2 h. Six control fetuses with no obvious developmental or neuropathological abnormalities and seven fetuses with DS were used (Table 1). Trisomy was caryotypically proved from the results of genetic amniocentesis procedures. All cases were classical trisomy 21 (free trisomy: triplication of chromosome 21). Autopsies were performed at the Institute of Pathology of the St. Orsola‐Malpighi Hospital. The gestational age of each fetus was estimated by menstrual history and crown‐rump length.

Table 1.

Cases of the present study. Abbreviations: CRL = crown‐rump length; BW = body weight; N.A. = not available.

| Case | Age (weeks) | Sex | CRL (cm) | BW (gm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control fetuses | ||||

| A92_07 | 18 | F | 13.5 | 235 |

| A58_07 | 19 | F | 15 | 290 |

| A01_09 | 19 | F | N.A. | N.A. |

| A33_07 | 20 | M | 17 | 300 |

| A139_08 | 20 | M | 16.5 | 388 |

| A88_07 | 21 | M | 21.6 | 350 |

| Down syndrome fetuses | ||||

| A97_08 | 17 | F | 12 | 118 |

| A127_08 | 18 | M | 14.5 | 240 |

| A85_07 | 19 | M | 14 | 250 |

| A85_06 | 20 | F | 16 | 240 |

| A06_07 | 20 | M | 16.5 | 320 |

| A138_06 | 20 | M | N.A. | N.A. |

| A61_07 | 21 | F | 22 | 310 |

List of the cases used in the present study. Age refers to gestational age in weeks.

Histological procedures

Whole brains were fixed by subdural perfusion with Metacarnoy fixative (methyl alcohol : chloroform : acetic acid 6:1:1) injected through the anterior and posterior fontanelles. After 24 h–48 h the brains were removed, the cerebellum was dissected out and cut along the midsagittal plane. The cerebellar hemispheres were post‐fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde for 5–7 days and embedded in paraffin, according to standard procedures. Sections 16 µm‐thick and 4 µm‐thick were made from the right and left hemisphere, respectively. One hemisphere of the fetal cerebellum was represented in approximately 350–450 16 µm‐thick sections. One out of 10 sections from the right hemisphere was mounted on a glass slide. The total number of mounted sections was 35–45 per subject. Sections were deparaffinized in xylenes, hydrated in graded ethanol to water, stained with Toluidin Blue, according to the Nissl method, differentiated in graded ethanols to xylene and cover‐slipped. These sections were used for evaluation of cerebellar volume, length of cerebellar fissures, number of lobuli and layer thickness. Forty consecutive sections from the left hemisphere, taken starting from the midline, were mounted on glass slides. Series of three or four sections positioned 32 µm apart were (i) Nissl‐stained and used for evaluation of cell number, cell size and number of pyknotic cells; (ii) processed for Ki‐67 immunohistochemistry, for evaluation of cell proliferation; (iii) processed for vimentin immunohistochemistry, for evaluation of radial glia processes; and (iv) processed for cleaved caspase‐3 immunohistochemistry, for evaluation of apoptotic cells.

Ki‐67 immunohistochemistry

Sections from the left hemisphere were stained using a monoclonal anti‐Ki‐67 antibody (dilution 1:500; clone MM1), from Novocastra Laboratories (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), according to the procedures previously described (9). Sections were retrieved with citrate buffer pH 6.0 at 98°C for 40 minutes before incubation with the antibody and were processed as previously described (9). All sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

Vimentin immunohistochemistry

Sections from the left hemisphere were deparaffinized in xylenes, hydrated in graded ethanol and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100® (Fluka‐Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for 30 minutes and blocked for 1 h in 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in 0.1% Triton X‐100 and PBS. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti‐vimentin antibody (Sigma, Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), diluted 1:200 in 0.1% Triton X‐100 in PBS, washed in 0.1% Triton X‐100 in PBS for 40 minutes, and incubated for 2 h with a Cy3‐conjugated anti‐mouse IgG (1:200; Sigma).

Cleaved caspase‐3 immunohistochemistry

Sections from the left hemisphere were immunostained for cleaved caspase‐3 using a polyclonal rabbit antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) (diluted 1:800), as previously described (9). Sections were Hoechst‐stained for evaluation of total cell number.

Measurements

Image acquisition and analysis

Bright field images were taken with a Leitz Diaplan microscope, equipped with a motorized stage, and a Coolsnap‐Pro colour digital camera (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Measurements were carried out with the software Image Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics). Fluorescent images were taken with an Eclipse TE 2000‐S microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with an AxioCam MRm digital camera (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Cerebellar volume

Overall cerebellar volume was evaluated based on Cavalieri's principle 18, 53, by tracing the outer border of the cerebellum in a series of 9–11 640 µm apart Nissl‐stained sections, encompassing the whole medio‐lateral extent of the right hemisphere. Volume was estimated by multiplying the sum of the areas by the distance (T = 640 µm) between sections. Total volume of the cerebellum was estimated by multiplying the volume of the right hemisphere by 2.

Length of the major cerebellar fissures

The length of the four major fissures was measured in three sections from the right hemisphere, 160 µm apart, starting from the midline. This location was chosen because at this level the major fissures are more clearly recognizable and deeper than at more lateral locations (see Figure 1A–D).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the anatomy of the cerebellum in Down syndrome (DS) and control fetuses. A–D. Nissl‐stained parasagittal sections across the cerebellum of a control (A, C) and a DS (B, D) fetus at gestational week (GW) 20. Sections in (A) and (B) and sections in (C) and (D) were taken close to the midline and approximately 2 mm from the midline, respectively. The white arrows in (A) and (B) indicate the major cerebellar fissures and the black arrow indicates a deep germinative region, called here the ventricular pocket (VP; see Results) near the roof of the fourth ventricle. The white dots in (A–D) indicate the cerebellar lobuli. E–G. Depth of the cerebellar fissures (E), number of lubuli (F) and total cerebellar volume (G) in control and DS fetuses. Values are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 (two tailed t‐test). Calibration bar in D = 2000 µm refers to A–D. Abbreviations: c = caudal; Ch Pl = choroid plexus; d = dorsal; IV = fourth ventricle; l, = lateral; L1‐L5 = cerebellar lobes; m = medial; MB = midbrain; pc = preculminate fissure; pl = posterolateral fissure; pr = primary fissure; r = rostral; sec = secondary fissure; v = ventral.

Foliation

The number of cerebellar lobuli (see Figure 1A–D) was counted in the same series of sections used for volume evaluation. Their mean number was then obtained by averaging the number of lobuli counted in individual sections.

Thickness of cerebellar layers

The thickness of individual layers was measured in three sections from the right hemisphere, 800 µm apart. The first section was close to the midline. Measurements were taken at 10–16 random locations along cerebellar lobes 1–3. These lobes were chosen because individual layers were more clearly recognizable than in lobes 4 and 5 (see Figure 2). Measurements were taken in the different lobuli forming lobes 1–3, avoiding the depths of the foldings, where layers exhibit a greater thickness.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the thickness of the cerebellar layers in Down syndrome (DS) and control fetuses. A–E. Nissl‐stained sagittal section close to the cerebellar midline of a control fetus [gestation week (GW) 18], showing the cytoarchitectonics of the cerebellar cortical layers in different lobes. Images in (A) and (C) correspond to the regions enclosed by a black square in (B). Images in (D) and (E) correspond to the regions enclosed by a white rectangle in (A) and (C), respectively. F–I. Thickness of the external granular layer (F), molecular layer (G), Purkinje cell layer (H) and internal granular layer (I) in control and DS fetuses. Values are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed t‐test). Calibration bars: B = 2000 µm; A,C = 500 µm; D,E = 50 µm. Abbreviations: c = caudal; d = dorsal; EGL = external granular layer; IGL = internal granular layer; l = lateral; LD = lamina dissecans; L1‐L5 = cerebellar lobes; m = medial; MOL = molecular layer; PURK = Purkinje cell layer; r = rostral; v = ventral, WM = white matter.

Cell density

In Nissl‐stained sections from the left hemisphere, cell density was evaluated in the external granular layer (EGL), molecular layer (MOL), Purkinje cell layer (PURK), inner granular layer (IGL), perspective white matter and ventricular pocket (VP) (see below). Cells were counted within randomly traced areas (1500–2000 µm2, for the EGL; 4000–5000 µm2, for the MOL; 1500–2000 µm2, for the PURK; 6000–7000 µm2, for the IGL, white matter and VP). Because of the small section thickness, cell nuclei could be seen in a single plane of focus and cells were counted in single images, taken at the best plane of focus. The density of cells in each layer was obtained by dividing the number of counted cells by the area of the sampled region and was expressed as cell number per 1 mm2. Cell density in the EGL and MOL was measured in each cerebellar lobulus of all cerebellar lobes. Cell density in the PURK and IGL was measured in each lobulus of lobes 1–3, where a lamina dissecans was clearly recognizable. Cell density in the white matter was measured in the core of each of the cardinal cerebellar lobes. To standardize measurements, a line was drawn from the top to the base of each lobe. A second perpendicular line was drawn midway to the first one. Cell density was measured in the area that surrounded the intercept between these two lines.

Labeling index (LI) of Ki‐67‐positive cells

Proliferating cells were identified with immunostaining for Ki‐67 35, 44. Ki‐67‐positive cells were counted in the EGL and IGL of all cerebellar lobules and lobes, and in a region overlying the roof of the fourth ventricle at the level of the fifth lobe that was formed by a mass of actively dividing cells. This region will be called here the VP (1, 5). Ki‐67‐positive cells and cells that were not Ki‐67‐positive cells were counted within randomly traced areas in the EGL (1500–2000 µm2), IGL and VP (6000–7000 µm2). Counts were expressed as LI calculated by dividing Ki‐67‐positive cells by all cells (Ki‐67‐positive plus Ki‐67‐negative cells) present in the sampled area.

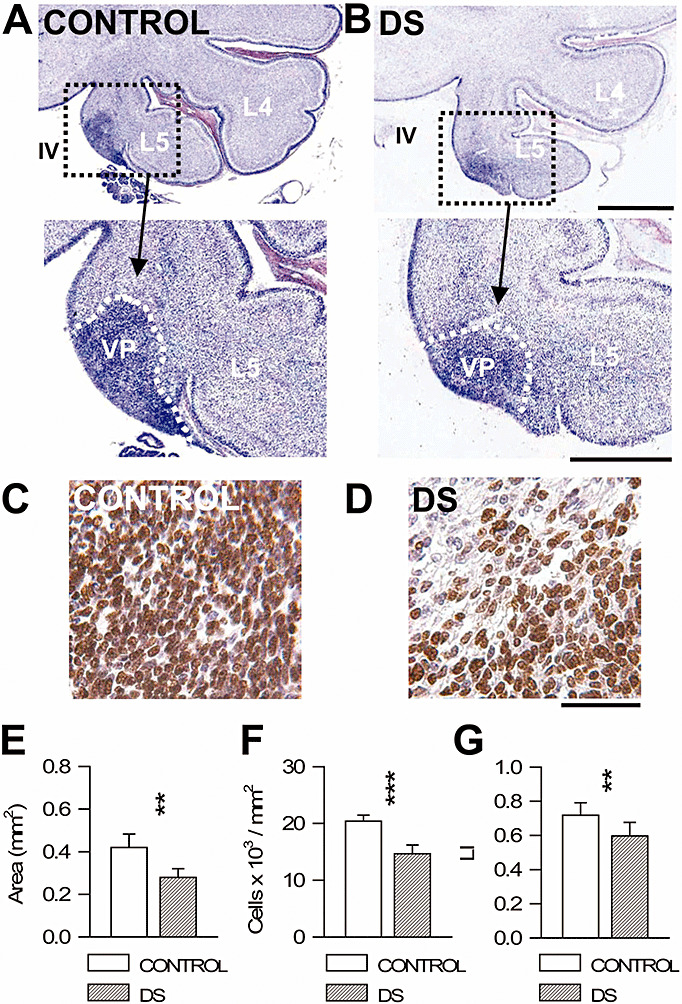

Figure 5.

Cell proliferation in the VP of Down syndrome (DS) and control fetuses. A, B. Nissl‐stained sagittal sections across the cerebellum of a control (A) and a DS (B) fetus [gestation week (GW) 20]. Images at the bottom are higher magnifications of the region enclosed by squares. Note a mass of darker cells (enclosed by the stippled white line) in the region of the fifth lobe overlying the roof of the fourth ventricle. This region is called the VP here. C, D. Examples of sections across the VP of a control (A) and a DS (B) fetus (GW 20) immunostained for Ki‐67 and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Cells immunostained for Ki‐67 appear labeled in brown. E–G. Mean surface area (E), cell density, expressed as number of cells/mm2 (F) and number of Ki‐67‐positive cells, expressed as number of cells over total cell number (labeling index: LI) (G) in the VP of control and DS fetuses. Values are mean ± SD. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (two‐tailed t‐test). Calibration bars in (A,B): low magnification images = 1000 µm; higher magnification images = 500 µm. Calibration bars in (C,D) = 50 µm; Abbreviations: IV = fourth ventricle; L4 and L5 = cerebellar lobes; VP = ventricular pocket.

Number of apoptotic cells

In Nissl‐stained sections from the left hemisphere, apoptotic cells were detected in the EGL, IGL and VP based on the pyknotic appearance of their condensed nucleus. Counts were carried out in the same areas used for the evaluation of cell density (see above). In sections immunostained for cleaved caspase‐3, apoptotic cells were counted in the EGL, IGL and VP in randomly traced areas. The number of either pyknotic or cleaved caspase‐3‐positive cells was divided by the total number of cells present in the sampled areas (apoptotic index).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SD. The subject means were statistically analyzed with the two‐tailed Student's t‐test. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Gross anatomy of the cerebellum in fetuses with DS

Development of the human cerebellum extends from 4 weeks of gestational age to the first postnatal year 1, 30, 50. At the 12th week of development, the infolding of the initially smooth cerebellar surface gives origin to the four major fissures that separate the five major cerebellar lobes. At further stages of development there is a progressive increase in the infoldings of the cerebellar fissures, and minor infoldings give origin to cerebellar lobuli.

In the cerebellum of both normal and DS fetuses the five cardinal lobes, separated by the four major fissures, were clearly recognizable (Figure 1A,B) at all ages examined here. The five cardinal lobes were clearly recognizable in sections close to the midline (cerebellar vermis), whereas the fissures became progressively less pronounced toward a lateral direction and the lobes were no longer recognizable (Figure 1C,D). Individual lobes presented various lobuli (see the lobuli marked by filled dots in Figure 1A–D), the number of which progressively decreased going in a lateral direction (Figure 1A–D).

As evident from observation of Figure 1A,B, fetuses with DS had shallower cerebellar fissures than those of controls. Measurement of the mean length of the four fissures in the vermis region showed that in fetuses with DS it was significantly smaller (−15%) than in controls (Figure 1E). After observing sections taken at both medial (Figure 1A,B) and lateral (Figure 1C,D) levels of the cerebellum, it was evident that fetuses with DS had a patently reduced number of lobuli. Evaluation of the number of lobuli in the series of sampled sections across the whole mediolateral extent of the cerebellum showed that in fetuses with DS the mean number of lobuli was 29% lower than that observed in controls (Figure 1F). Estimation of the total volume of the cerebellum based on Cavalieri's principle (see Methods) showed that fetuses with DS had a cerebellar volume smaller (−21%) than that found in controls (Figure 1G).

Thickness of the cellular layers in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

Cerebellar neurons are generated from two distinct progenitor zones: the cerebellar ventricular zone (VZ) and the more dorsally located rhombic lip (RL) 30, 50. Purkinje cells are specified within the VZ and, between GW 5–6, post‐mitotic Purkinje cells leave the VZ and migrate radially to reach the future PURK. Around GW 12, a wave of migration starts from the RL and proceeds tangentially over the subpial surface of the developing cerebellum where it forms a secondary neuroepithelium, the EGL. At GW 16, cells from this intensely proliferating germinal layer migrate inward, cross the MOL and the PURK and form the underlying IGL. Granule cell precursors (GCPs) in the EGL continue to proliferate up to the fifth postnatal month and the EGL completely disappears by the 11th postnatal month (1).

At the examined gestational ages the cerebellar cortex was formed by five laminae in lobes 1–3 and four laminae in lobes 4 and 5 (Figure 2). The EGL appeared as a densely populated layer, overlying the MOL, which was populated by loosely arranged cells. Below the MOL was the PURK, which, in lobes 1–3, was separated from the IGL by a cell‐poor layer, the lamina dissecans (Figure 2D). This is a transient layer that disappears by the 30th week of gestation, when it becomes filled with migrating granule cells 1, 50. In lobes 4 and 5 a lamina dissecans was lacking (Figure 2E) because in these lobes its appearance and evolution are delayed (30). To establish possible differences between DS and control fetuses in cerebellar histology, we measured the thickness of the EGL, MOL, PURK and IGL in lobes 1–3, where the borders of the individual layers were more delineated. We found no differences between control and DS fetuses in the thickness of the MOL and PURK (Figure 2G,H). In contrast, in fetuses with DS, the thickness of the EGL and IGL was significantly smaller (−10% and −16%, respectively) than in controls (Figure 2F,I).

Cell density in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

At the examined ages, the EGL and MOL were populated by GCPs. Basket cells and star cells make their appearance in the MOL at the 16th week of development (30). As these interneurons are not recognizable in Nissl‐stained material, we will call all cells in the MOL “GCPs”, although some of them may be basket cells and star cells. The PURK was populated by migrating GCPs directed to the IGL and by various rows of larger cells (Figure 3C–F), most of which were very large in size. The IGL, in addition to granule cells (cerebellar granule cells; CGCs), contained larger‐sized cells, most of which had an elongated oval body that could give rise to cytoplasmic processes (Figure 3C,D,J,H).

Figure 3.

Comparison of cell density in the cerebellum of Down syndrome (DS) and control fetuses. A–H. Examples of Nissl‐stained sagittal sections from the vermis region of the cerebellum of a control (A, C, E, G) and a DS (B, D, F, H) fetus [gestation week (GW) 20]. Images in (E,F) show that the PURK is populated by migrating granule cell precursors (empty arrow) and large cells (white arrow). Images in (G,H) show that the IGL is populated by cerebellar granule cells (empty arrow) and larger ovoid cells (white arrow). I–M: Cell density, expressed as number of cells/mm2 in the EGL (I), MOL (J), PURK (K), IGL (L) and perspective white matter (M). Values are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (two‐tailed t‐test). Calibration bars = 20 µm. Calibration in (D) refers to (A–D) and calibration in (H) refers to (E–H). Abbreviations: CGCs = cerebellar granule cells; EGL = external granular layer; GCPs = granule cell precursors; IGL = internal granular layer; LD = lamina dissecans; MOL = molecular layer; OCs = other cells; PURK = Purkinje cell layer; TOT = total cell number; WM = white matter.

We were interested in establishing whether the trisomic condition affects cell density in the different layers of the fetal cerebellum and whether this effect involves different cell populations. To this purpose, we evaluated cell density in the EGL, MOL, PURK and IGL. In the PURK and IGL we discriminated between granule cells and all other cells present in these layers. Based on the size of GCPs in the EGL of control fetuses, we considered the cells present in the PURK and IGL that had a surface area ≤35 µm2 (a value that corresponds to the maximum size of the GCPs in the EGL) as GCPs and CGCs, respectively. Cells that had a surface area >35 µm2 were considered as “other cells” (OCs).

We measured the surface areas of GCPs, CGCs and OCs (Table 2), to establish possible differences between DS and control fetuses in cell size. We found that in fetuses with DS the size of the GCPs in the EGL was significantly smaller (−9%) than controls. The size of the GCPs in the MOL and PURK and the size of the CGCs in the IGL were also smaller in DS vs. control fetuses, though this difference was not statistically significant. Whereas in fetuses with DS the size of the OCs in the IGL was similar to that found in controls, the size of the OCs in the PURK was significantly smaller (−11%) (Table 2). These size differences suggest that in DS fetuses cell maturation is delayed compared with that of controls.

Table 2.

Size of cerebella cells. Abbreviations: CGCs = cerebellar granule cells; EGL = external granular layer; GCPs = granule cell precursors; IGL = internal granular layer; MOL = molecular layer; OCs = other cells; PURK = Purkinje cell layer; N.S. = not significant (two‐tailed t‐test).

| CONTROL | DS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | P | ||

| EGL | GCPs | 23.37 ± 1.30 | 21.19 ± 0.75 | * |

| MOL | GCPs | 24.51 ± 0.20 | 23.19 ± 3.39 | N.S. |

| PURK | GCPs | 24.51 ± 2.26 | 23.22 ± 1.92 | N.S. |

| OCs | 48.55 ± 3.55 | 43.21 ± 2.54 | * | |

| IGL | CGCs | 24.72 ± 1.95 | 23.62 ± 1.86 | N.S. |

| OCs | 45.16 ± 1.96 | 45.18 ± 1.76 | N.S. | |

Surface area (µm2) of the different cell types in the cerebellar cortex of control fetuses and fetuses with DS. *P < 0.01.

Observation of the images in 3, 4 clearly shows a notable hypocellularity in all layers of the cerebellar cortex of fetuses with DS. Quantitative analysis showed that fetuses with DS had a significantly reduced cell density compared with controls in all layers (Figure 3I–L), with differences that ranged from −25% to −50%, according to cell type and layer. In fetuses with DS the density of GCPs was −25% in the EGL (Figure 3I) and MOL (Figure 3J), and the density of all cells populating the PURK (Figure 3K) and IGL (Figure 3L) was −39%. The separate analysis of GCPs and OCs in the PURK showed that in fetuses with DS the density of the GCPs was −30% and that of the OCs −50% (Figure 3K). The separate analysis of CGCs and OCs in the IGL (Figure 3L) showed a reduced density in fetuses with DS for both CGCs (−39%) and OCs (−38%). Since at early developmental stages the perspective cerebellar white matter is characterized by a diffuse cellularity (Figure 2D), we also evaluated cell density in this region, at the level of the core of each lobe (see Methods). We found that in fetuses with DS the white matter had a cell density smaller (−27%) than that of controls (Figure 3M).

Figure 4.

Cell proliferation in the cerebellar cortex of Down syndrome (DS) and control fetuses. A, B. Sagittal sections across the cerebellum of a control (A) and a DS (B) fetus [gestation week (GW) 19] immunostained for Ki‐67 and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Images on the left in (A) and on the right in (B) are higher magnifications of the regions enclosed by boxes. Cells immunostained for Ki‐67 appear labeled in brown. Proliferating cells were present in the EGL (see, for instance, the cells indicated by the white arrow in the EGL) and in the IGL (see, for instance, the cells indicated by the red arrow in the IGL). C, D. Density of Ki‐67‐positive cells, expressed as number of cells over total cell number (labeling index: LI) in the EGL (C) and IGL (D) of control and DS fetuses. Values are mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 (two‐tailed t‐test). Calibration bars: low magnification images = 50 µm; higher magnification images = 10 µm. Abbreviations: EGL = external granular layer; IGL = internal granular layer; MOL = molecular layer; PURK = Purkinje cell layer.

Cell proliferation in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

Proliferating cells in formaldehyde‐fixed specimens can be identified with immunostaining for Ki‐67, an antibody that reacts with an antigen appearing in cell nuclei through G1 + S + G2 + M phases of the cell cycle 35, 44. We previously found that fetuses with DS had a remarkably lower number of proliferating cells in the dentate gyrus, VZ of the hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus and ventricular germinal matrix 10, 16. We have examined here proliferation in the cerebellum, to establish whether this structure shares the same proliferation defects present in other regions of the DS brain.

At the examined ages there were densely packed Ki‐67‐positive cells in the EGL and less numerous dividing cells in the IGL (Figure 4A,B). Most of the Ki‐67‐positive cells in the IGL had a large ovoid nucleus (Figure 4A,B) and fewer cells had a round nucleus with a smaller size. Ki‐67‐positive cells were only occasionally found in the MOL and PURK. Scattered proliferating cells were present throughout the whole cerebellar white matter. In Nissl‐stained sections, a mass of darkly‐stained cells was clearly recognizable close to the roof of the fourth ventricle, at the inferior level of the fifth lobe (see VP in 1, 5). Ki‐67 immunohistochemistry showed that this region was populated by densely packed Ki‐67‐positive cells (Figure 5C,D). In view of its location we have called this segregated mass of proliferating cells the VP.

Observation of cerebellar sections from control and DS fetuses showed patent differences in the number of Ki‐67‐positive cells in the EGL, IGL (Figure 4A,B) and VP (Figure 5C,D). To quantify these differences, we expressed the number of proliferating cells as the LI (see Methods). We found that in the EGL of control fetuses the LI was ∼0.8% (Figure 4C), indicating that most (80%) of the cells present in this zone were actively dividing. In fetuses with DS, the LI had a value of only ∼0.6 (Figure 4C), indicating that the number of proliferating cells was considerably reduced (−25%) compared with controls. In agreement with previous evidence regarding the developing fetal cerebellum (1), the LI decreased from the youngest to the oldest examined gestational ages, going from 0.88 to 0.74 in control fetuses and from 0.72 to 0.59 in fetuses with DS. These values indicate that the proliferation rate decreased in a proportionally similar manner in control and DS fetuses, which, in turn, implies that the reduced proliferation rate of fetuses with DS does not improve with time. The LI in the IGL of control fetuses was ∼0.2 (Figure 4D), indicating a certain degree of proliferation also in this layer, though at a notably lower level than in the EGL. The LI in the IGL of DS fetuses was ∼0.1 (Figure 4D), indicating that they also had fewer proliferating cells (−50%) than controls in this layer. Measurement of the mean area of the VP showed that in DS it was smaller (−33%) than controls (Figure 5E). Similarly to the cerebellar cortex, the VP had a lower (−29%) cell density in DS vs control fetuses (Figure 5F). The LI in the VP of control fetuses was ∼0.7 (Figure 5G), indicating that most of the cells present in this zone were actively dividing cells. In fetuses with DS, the LI had a value of ∼0.5 (Figure 5G), which corresponds to a reduction of −17%.

Apoptotic cell death in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

Apoptotic cell death accompanies cell proliferation during brain development and contributes to the regulation of the final number of neurons. We evaluated apoptotic cell death in the EGL, IGL and VP, the cerebellar regions showing active proliferation, by counting the number of pyknotic cells in Nissl‐stained material and the number of cells that expressed cleaved caspase‐3, a protein that is one of the hallmarks of apoptotic death, in sections immunostained for cleaved caspase‐3. The number of apoptotic cells was expressed as the number of either pyknotic cells or cleaved caspase‐3‐positive cells over the total number of cells in each sampled region. In agreement with previous evidence in the cerebellum of 24‐week‐old fetuses (1), we found very few pyknotic cells in the EGL and IGL of control fetuses. Similarly to the EGL and IGL, there were also very few pyknotic cells in the VP (Table 3). In sections immunostained for cleaved caspase‐3 the number of apoptotic cells was approximately similar to that of the pyknotic cells in Nissl‐stained material. Comparison of the number of pyknotic cells and cleaved caspase‐3 positive cells in control and DS fetuses showed no differences between groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of apoptotic cells in the cerebellum of control (C) and Down syndrome (DS) fetuses. Abbreviations: EGL = external granular layer; IGL = internal granular layer; VP = ventricular pocket; N.S. = not significant (two‐tailed t‐test).

| EGL | IGL | VP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Pyknotic cells | |||

| C | 0.0037 ± 0.0004 | 0.0017 ± 0.0013 | 0.0011 ± 0.0008 |

| DS | 0.0075 ± 0.0049 | 0.0014 ± 0.0013 | 0.0008 ± 0.0006 |

| P | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

| Cleaved caspase‐3‐positive cells | |||

| C | 0.0034 ± 0.0044 | 0.0045 ± 0.0062 | 0.0028 ± 0.0022 |

| DS | 0.0025 ± 0.0049 | 0.0058 ± 0.0092 | 0.0022 ± 0.0011 |

| P | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. |

The number of apoptotic cells is expressed as the number of either pyknotic cells or cleaved caspase‐3‐positive cells over the total number of cells.

Vimentin immunoreactivity in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

In the developing brain, radial glia processes provide a scaffold along which the new neurons migrate to reach their final destination (29). To compare the architecture of glial processes in the cerebellum of DS vs. control fetuses, cerebellar sections were processed for vimentin immunohistochemistry, a protein expressed by radial glia, including cerebellar Bergmann glia (27). We found that glial processes were present throughout the thickness of the cerebellar cortex both in control and DS fetuses (Figure 6A,B). In the latter, however, the number of processes was remarkably lower than in controls, in all layers (Figure 6A,B). Bergmann glia fibers play a crucial role in cerebellar development because they provide a route along which GCPs leaving the EGL migrate across the MOL to reach the IGL. Observation of the relationship between radial glia fibers and migrating GCPs in the MOL showed that whereas in normal fetuses numerous glia processes provided a dense scaffold along which numerous migrating GCPs appeared to be conveyed to the IGL (Figure 6D), in the MOL of DS fetuses there were remarkably fewer processes and fewer GCPs that followed this route (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Vimentin immunoreactivity in the cerebellum of fetuses with Down syndrome (DS). A, B. Examples of sections processed for immunofluorescence with an anti‐vimentin antibody from a control (A) and a DS (B) fetus [gestation week (GW) 20]. Radial glia processes radiate across all cerebellar layers. C, D. Examples of sections processed for immunofluorescence with an anti‐vimentin antibody (red) from a control (C) and a DS (D) fetus. Cell nuclei were stained by Hoechst dye (blue). The white arrows in (A–D) indicate processes of radial glia cells. Calibration bars = 25 µm. Abbreviations: EGL = external granular layer; IGL = internal granular layer; MOL = molecular layer; PURK = Purkinje cell layer.

DISCUSSION

The current study provides novel evidence that in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS there is a generalized hypocellularity and that this defect is due to a severe proliferation impairment, rather than to an increased cell death.

Immature cerebellar pattern and reduced cerebellar volume in fetuses with DS

Though fetuses with DS had a normal number of principal lobes, the depth of the major fissures and the number of lobules were smaller than in controls. The surface of the cerebellar anlage is initially smooth. The formation of folds (folia) arises through a series of cell movements and structural changes and consists of two stages: the first stage is the formation of the cardinal lobes and the second one is the formation of lobules 45, 46. There is evidence that massive GCP proliferation and migration are required for development of cerebellar folds, and mutant mice with CGC defects have a reduction or loss of folds (43). The morphogenetic factor Sonic hedgehog (Shh), expressed by the Purkinje cells, is one of the master players in cerebellar patterning because it is critical for GCP proliferation. Recent evidence shows that the extent of cerebellar foliation is regulated by the level of Shh signaling. While an increased level increases granule cell proliferation and produces a more complex foliation pattern, a reduction results in a reduced GCP proliferation and a simpler foliation pattern (11). Anchor points in the PURK are essential for the folding of the smooth surface of the cerebellum and Bergman glia cells play an important role in the function of the anchoring centers by directing migration of GCPs to the base of the fissure 45, 46. Fetuses with DS had notably fewer granule cells, Purkinje cells and Bergmann glia and fewer Bergmann glia processes (see below). In view of the crucial role played by granule cells, Purkinje cells and Bergmann glia in fissure formation, all these defects fully account for the abnormal foliation pattern found in the DS fetal cerebellum.

We found that in fetuses with DS the cerebellum had a reduced volume, which is in line with neuroimaging studies and post‐mortem cerebellar examination 17, 22, 26, 37, 51, 54. From a study on human fetuses (17) it appears that control and DS fetuses of 17–21 weeks of age have a mean brain weight of about 50 g and 43 g, respectively, indicating that the brain weight of fetuses with DS is 87% of that of controls. Our study shows that in fetuses with DS the cerebellar volume is 79% of that of control fetuses, suggesting that the cerebellar hypotrophy is comparatively more pronounced than overall brain hypotrophy. This finding is in agreement with evidence obtained from the postnatal DS brain, showing that cerebellar volume is disproportionally reduced (26). Though it has long been recognized that the cerebellum of individuals with DS is hypotrophic, the causes of this defect have not been elucidated so far. We show here that the cerebellum of fetuses with DS is characterized by a severe hypocellularity in all layers (see below) and reduced thickness of the layers that harbor GCPs (EGL) and CGCs (IGL). This indicates that impaired histogenesis and cytogenesis during early developmental stages are major determinants of the cerebellar hypotrophy of individuals with DS.

Widespread hypocellularity in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

DS fetuses had a reduced cell density in all cerebellar layers, the difference vs. controls ranging from −25% to −50%, according to layer and cell type. If the density reduction were counterbalanced by an increase in layer thickness, the outcome might be a lack of change in net cell number. However, in fetuses with DS the thickness of the EGL and IGL was smaller than in controls and that of the MOL and PURK was similar to controls, which means that fetuses with DS had a reduced number of cells in all these layers. The fact that in the EGL and IGL cell density was notably reduced (−25% and −39%, respectively) and that this effect was accompanied by a reduced layer thickness (−10% and −16%, respectively) implies that fetuses with DS had a very large reduction in the net number of GCPs and CGCs.

In the PURK and IGL we evaluated, in addition to the density of GCPs and CGCs, respectively, also that of the “other cells” (OCs) harbored in these layers. At the examined developmental stages, the PURK contains, in addition to migrating CGPs, the somas of Purkinje cells and sparser Golgi II neurons (30). While at later stages the somas of Bergmann glia cells are also located in the PURK, at the examined ages the somas of Bergmann glia are below this layer (7). Most of the OCs in the PURK had the shape and size of Purkinje cells, strongly suggesting that the density reduction of the OCs in the PURK of fetuses with DS reflected a reduction in the number of Purkinje cells. At stages corresponding to those examined here, the IGL contains, in addition to CGCs, astrocytes that send their processes to the external part of the cerebellum (30). The reduced density of the OCs in the IGL of DS fetuses suggests that they had fewer astrocytes than controls. Consistently with this, in DS fetuses there were fewer astrocytic processes across the whole cerebellar cortex. As radial glia processes in the MOL belong to Bergmann glia, their reduced density in this layer implies a reduction in the number of Bergmann glia cells and impairment of GCP migration due to a deficiency of migratory routes. According to recent evidence in mouse models for DS, neural precursors from trisomic animals exhibit defective migration from the site of origin to their final destination 21, 34 and genes involved in cell migration appear to be dysregulated in the developing trisomic cerebellum (12). Given that the same holds for the human cerebellum, migration abnormalities of cerebellar precursor cells may contribute to explaining the patent dysplasia of all cerebellar layers in DS fetuses.

Very few studies have examined the histology of the cerebellum in individuals with DS and no study has examined cerebellar histology and cytogenesis during fetal development. We provide here evidence that the cell density reduction documented in the IGL of children and adults with DS (4) is a defect that can be traced back to very early stages of cerebellar development and additionally demonstrate that the DS fetal cerebellum is characterized by a widespread and severe hypocellularity that involves all layers and all major cell types.

Proliferation impairment in the cerebellum of fetuses with DS

Purkinje cells, inhibitory interneurons (Golgi cells, basket cells and star cells) and glial cells arise from the VZ. Post‐mitotic Purkinje cells leave the VZ between GW 5–6. Progenitors that delaminate from the VZ and continue to divide within the future white matter give origin to inhibitory interneurons and glial cells. In mice, these cells exhibit a prolonged capacity to proliferate that lasts up to the first postnatal week (52). Granule cells are generated from the secondary neuroepithelium, the EGL, derived from the RL.

By using Ki‐67 immunohistochemistry we found numerous proliferating cells in the EGL at GW 17–21, which is consistent with the time course of GCP proliferation (1). There were very few proliferating cells in the MOL and PURK, which is in agreement with the fact that the major cell types of these layers, GCPs and Purkinje cells, respectively, are post‐mitotic cells. A sizable population of proliferating cells was present in the IGL and Ki‐67‐positive cells were also observed throughout the white matter. The Ki‐67‐positive cells in the MOL, PURK, IGL and white matter are most likely precursors of glial cells and/or cerebellar interneurons, as these cells retain proliferative capacity during migration from the VZ to the cerebellar cortex (52). Ki‐67‐positive cells were also observed in a restricted region (the VP) of the fifth lobe. This is in agreement with evidence that cell proliferation in the VZ ceases at the 13th GW in all regions of the cerebellum except for the flocculonodular region where cell multiplication continues after birth (30).

Fetuses with DS had a reduced LI in the EGL, IGL and VP. As the LI represents the relative number of proliferating cells over total cell number, it provides information on the proliferation potency of the examined cell population, irrespective to its size. As the EGL, IGL and VP of fetuses with DS were populated by fewer cells than controls, a reduction in the number of Ki‐67‐positive cells is also expected. The smaller LI in fetuses with DS, however, means that they had proportionally fewer Ki‐67‐positive cells and, consequently, a reduced proliferation potency. This reduction may be due to (i) cell cycle elongation; (ii) precocious exit from the cells cycle; and (iii) increased cell death. Evaluation of apoptotic cell death in the EGL, IGL and VP showed that in fetuses with DS the number of apoptotic cells was similar to that found in controls. We previously found that in the hippocampal region of fetuses with DS there were more apoptotic cells than in controls (16). There is evidence both in favor and against increased apoptosis in the fetal DS brain 14, 20, 42. These discrepancies may be attributable to differences in cell death across brain regions and/or ages. However, in view of the very low number of apoptotic cells in the fetal cerebellum, the possibility also exists that actual differences between control and DS fetuses are undetectable because of the interindividual variance in the number of apoptotic cells within groups. Yet, given that this is actually the case, considering the very low number of apoptotic cells, the large reduction in the number of proliferating cells found in DS fetuses is unlikely to be due to an increased cell death. As Ki‐67 is not expressed during the early G1 phase of the cell cycle and by post‐mitotic cells (41), the reduced LI in fetuses with DS may be due to an elongation of early G1 and/or a precocious exit from the cell cycle. The first possibility is in agreement with evidence that GCPs in the Ts65Dn mouse model have a reduced proliferation potency due to cell cycle elongation and that this defect is due to elongation of the G1 and G2 phases 9, 10.

The reduced LI in the EGL of fetuses with DS fully accounts for the reduced number of granule cells populating the IGL. The reduced LI in the VP of fetuses with DS indicates proliferation impairment in a region that is the remnant of the VZ (30), which is the source of Purkinje cells, inhibitory interneurons and glial cells. In agreement with this, fetuses with DS had a reduced number of Purkinje cells in the PURK and astrocytes in the IGL (possibly also of inhibitory interneurons) and a reduced number of cells in the perspective white matter. The presence of proliferating cells in the IGL indicates that cells derived from the VZ retain the capacity to divide after having reached the cerebellar cortex. Judging from the shape of their nuclei (Figure 4A,B), most of these cells may be precursors of glial cells, including Bergmann glia, which are known to proliferate throughout cerebellar development (1).

Purkinje cells express the mitogen Shh, which is critical for GCP proliferation (45). The reduced number of Purkinje cells in fetuses with DS suggests that a reduced production of Shh may be involved in the proliferation impairment of GCPs. Recent evidence shows that in trisomic mice, GCPs are less responsive to Shh (32), suggesting that alterations of the Shh pathway may be a critical determinant of the reduced proliferation potency that characterizes trisomic GCPs. It remains to be established whether alterations of the Shh pathway also underlie the impaired proliferation of precursors in the IGL and VZ.

Current evidence for a reduced GCP proliferation and a reduced number of CGCs and Purkinje cells in fetuses with DS is in line with similar evidence in the postnatal cerebellum of the Ts65Dn mouse 4, 32, which further validates the use of this mouse model to obtain insight into the mechanisms that underlie neurogenesis alteration in the DS brain. The generalized proliferation potency reduction found in the DS fetal cerebellum, in conjunction with previous evidence for reduced proliferation potency in numerous telencephalic regions of DS fetuses and mouse models for DS 5, 8, 10, 19, 24, 38, strengthens the idea that the trisomic brain is characterized by a widespread proliferation impairment and that this defect may be the major cause of the severe behavioral alterations that characterize DS.

CONCLUSIONS

It is well established that, in view of its connections, the cerebellum plays a key role in the regulation of proprioceptive‐motor control and motor learning. Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that it may also be involved in higher order functions such as emotion and cognition 39, 48, because cerebellar lesions can lead to the development of a behavioral pattern which is characterized by reduced cognitive efficiency associated with executive and visuospatial disorders, expressive language disorders and affective disorders. Current evidence that the cerebellum of fetuses with DS is characterized by a dramatic reduction in the number of its major cell types provides the structural correlate for the postural/motor dysfunctions and some of the cognitive disturbances of individuals with DS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the CARISBO Foundation, Bologna, Italy to R.B.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abraham H, Tornoczky T, Kosztolanyi G, Seress L (2001) Cell formation in the cortical layers of the developing human cerebellum. Int J Dev Neurosci 19:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aylward EH, Habbak R, Warren AC, Pulsifer MB, Barta PE, Jerram M, Pearlson GD (1997) Cerebellar volume in adults with Down syndrome. Arch Neurol 54:209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aylward EH, Li Q, Honeycutt NA, Warren AC, Pulsifer MB, Barta PE et al (1999) MRI volumes of the hippocampus and amygdala in adults with Down's syndrome with and without dementia. Am J Psychiatry 156:564–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baxter LL, Moran TH, Richtsmeier JT, Troncoso J, Reeves RH (2000) Discovery and genetic localization of Down syndrome cerebellar phenotypes using the Ts65Dn mouse. Hum Mol Genet 9:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bianchi P, Ciani E, Contestabile A, Guidi S, Bartesaghi R (2010) Lithium restores neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of the Ts65Dn mouse, a model for Down syndrome. Brain Pathol 20:106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brazel CY, Romanko MJ, Rothstein RP, Levison SW (2003) Roles of the mammalian subventricular zone in brain development. Prog Neurobiol 69:49–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi BH, Lapham LW (1980) Evolution of Bergmann glia in developing human fetal cerebellum: a Golgi, electron microscopic and immunofluorescent study. Brain Res 190:369–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clark S, Schwalbe J, Stasko MR, Yarowsky PJ, Costa AC (2006) Fluoxetine rescues deficient neurogenesis in hippocampus of the Ts65Dn mouse model for Down syndrome. Exp Neurol 200:256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Contestabile A, Fila T, Ceccarelli C, Bonasoni P, Bonapace L, Santini D et al (2007) Cell cycle alteration and decreased cell proliferation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus and in the neocortical germinal matrix of fetuses with Down syndrome and in Ts65Dn mice. Hippocampus 17:665–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Contestabile A, Fila T, Bartesaghi R, Ciani E (2009) Cell cycle elongation impairs proliferation of cerebellar granule cell precursors in the Ts65Dn mouse, an animal model for Down syndrome. Brain Pathol 19:224–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corrales JD, Blaess S, Mahoney EM, Joyner AL (2006) The level of sonic hedgehog signaling regulates the complexity of cerebellar foliation. Development 133:1811–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dauphinot L, Lyle R, Rivals I, Dang MT, Moldrich RX, Golfier G et al (2005) The cerebellar transcriptome during postnatal development of the Ts1Cje mouse, a segmental trisomy model for Down syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 14:373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de la Monte SM, Hedley‐Whyte ET (1990) Small cerebral hemispheres in adults with Down's syndrome: contributions of developmental arrest and lesions of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 49:509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engidawork E, Balic N, Juranville JF, Fountoulakis M, Dierssen M, Lubec G (2001) Unaltered expression of Fas (CD95/APO‐1), caspase‐3, Bcl‐2 and annexins in brains of fetal Down syndrome: evidence against increased apoptosis. J Neural Transm Suppl 61: 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Golden JA, Hyman BT (1994) Development of the superior temporal neocortex is anomalous in trisomy 21. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 53:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guidi S, Bonasoni P, Ceccarelli C, Santini D, Gualtieri F, Ciani E, Bartesaghi R (2008) Neurogenesis impairment and increased cell death reduce total neuron number in the hippocampal region of fetuses with Down syndrome. Brain Pathol 18:180–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guihard‐Costa AM, Khung S, Delbecque K, Menez F, Delezoide AL (2005) Biometry of face and brain in fetuses with trisomy 21. Pediatr Res 59:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gundersen H, Jensen E (1987) The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microsc 147:229–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haydar TF, Nowakowski RS, Yarowsky PJ, Krueger BK (2000) Role of founder cell deficit and delayed neuronogenesis in microencephaly of the trisomy 16 mouse. J Neurosci 20:4156–4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Helguera P, Pelsman A, Pigino G, Wolvetang E, Head E, Busciglio J (2005) ets‐2 Promotes the activation of a mitochondrial death pathway in Down's syndrome neurons. J Neurosci 25:2295–2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hewitt CA, Ling KH, Merson TD, Simpson KM, Ritchie ME, King SL et al (2010) Gene network disruptions and neurogenesis defects in the adult Ts1Cje mouse model of Down syndrome. PLoS One 5:e11561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ieshima A, Kisa T, Yoshino K, Takashima S, Takeshita K (1984) A morphometric CT study of Down's syndrome showing small posterior fossa and calcification of basal ganglia. Neuroradiology 26:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jernigan TL, Bellugi U, Sowell E, Doherty S, Hesselink JR (1993) Cerebral morphologic distinctions between Williams and Down syndromes. Arch Neurol 50:186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lorenzi HA, Reeves RH (2006) Hippocampal hypocellularity in the Ts65Dn mouse originates early in development. Brain Res 1104:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noble J (1998) Natural history of Down's syndrome: a brief review for those involved in antenatal screening. J Med Screen 5:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pinter JD, Eliez S, Schmitt JE, Capone GT, Reiss AL (2001) Neuroanatomy of Down's syndrome: a high‐resolution MRI study. Am J Psychiatry 158:1659–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pixley S, de Vellis J (1984) Transition between immature radial glia and mature astrocytes studied with a monoclonal antibody to vimentin. Brain Res 317:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rachidi M, Lopes C (2008) Mental retardation and associated neurological dysfunctions in Down syndrome: a consequence of dysregulation in critical chromosome 21 genes and associated molecular pathways. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 12:168–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rakic P (2003) Developmental and evolutionary adaptations of cortical radial glia. Cereb Cortex 13:541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rakic P, Sidman RL (1970) Histogenesis of cortical layers in human cerebellum, particularly the lamina dissecans. J Comp Neurol 139:473–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roizen NJ, Patterson D (2003) Down's syndrome. Lancet 361:1281–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roper RJ, Baxter LL, Saran NG, Klinedinst DK, Beachy PA, Reeves RH (2006) Defective cerebellar response to mitogenic Hedgehog signaling in Down [corrected] syndrome mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:1452–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roper RJ, St John HK, Philip J, Lawler A, Reeves RH (2006) Perinatal loss of TS65DN “Down Syndrome” mice. Genetics 172:437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roper RJ, VanHorn JF, Cain CC, Reeves RH (2009) A neural crest deficit in Down syndrome mice is associated with deficient mitotic response to Sonic hedgehog. Mech Dev 126:212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rose DS, Maddox PH, Brown DC (1994) Which proliferation markers for routine immunohistology? A comparison of five antibodies. J Clin Pathol 47:1010–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ross MH, Galaburda AM, Kemper TL (1984) Down's syndrome: is there a decreased population of neurons? Neurology 34:909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rotmensch S, Goldstein I, Liberati M, Shalev J, Ben‐Rafael Z, Copel JA (1997) Fetal transcerebellar diameter in Down syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 89:534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rueda N, Mostany R, Pazos A, Florez J, Martinez‐Cue C (2005) Cell proliferation is reduced in the dentate gyrus of aged but not young Ts65Dn mice, a model of Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett 380:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmahmann JD (2004) Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 16:367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmidt‐Sidor B, Wisniewski KE, Shepard TH, Sersen EA (1990) Brain growth in Down syndrome subjects 15 to 22 weeks of gestational age and birth to 60 months. Clin Neuropathol 9:181–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scholzen T, Gerdes J (2000) The Ki‐67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol 182:311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seidl R, Bidmon B, Bajo M, Yoo PC, Cairns N, LaCasse EC, Lubec G (2001) Evidence for apoptosis in the fetal Down syndrome brain. J Child Neurol 16:438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sekiguchi M, Shimai K, Guo H, Nowakowski RS (1992) Cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in hippocampal formation and cerebellum of dreher mutant mouse. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 67:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seress L, Abraham H, Tornoczky T, Kosztolanyi G (2001) Cell formation in the human hippocampal formation from mid‐gestation to the late postnatal period. Neuroscience 105:831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sillitoe RV, Joyner AL (2007) Morphology, molecular codes, and circuitry produce the three‐dimensional complexity of the cerebellum. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23:549–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sudarov A, Joyner AL (2007) Cerebellum morphogenesis: the foliation pattern is orchestrated by multi‐cellular anchoring centers. Neural Dev 2:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sylvester PE (1983) The hippocampus in Down's syndrome. J Ment Defic Res 27:227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tavano A, Grasso R, Gagliardi C, Triulzi F, Bresolin N, Fabbro F, Borgatti R (2007) Disorders of cognitive and affective development in cerebellar malformations. Brain 130:2646–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Teipel SJ, Schapiro MB, Alexander GE, Krasuski JS, Horwitz B, Hoehne C et al (2003) Relation of corpus callosum and hippocampal size to age in nondemented adults with Down's syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 160:1870–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. ten Donkelaar HJ, Lammens M, Wesseling P, Thijssen HO, Renier WO (2003) Development and developmental disorders of the human cerebellum. J Neurol 250:1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weis S, Weber G, Neuhold A, Rett A (1991) Down syndrome: MR quantification of brain structures and comparison with normal control subjects. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 12:1207–1211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weisheit G, Gliem M, Endl E, Pfeffer PL, Busslinger M, Schilling K (2006) Postnatal development of the murine cerebellar cortex: formation and early dispersal of basket, stellate and Golgi neurons. Eur J Neurosci 24:466–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. West MJ, Gundersen HJ (1990) Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol 296:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Winter TC, Ostrovsky AA, Komarniski CA, Uhrich SB (2000) Cerebellar and frontal lobe hypoplasia in fetuses with trisomy 21: usefulness as combined US markers. Radiology 214:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wisniewski KE (1990) Down syndrome children often have brain with maturation delay, retardation of growth, and cortical dysgenesis. Am J Med Genet Suppl 7:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]