Abstract

Rationale: Ivacaftor’s clinical effects in the residual function mutations 3849 + 10kb C→T and D1152H warrant further characterization.

Objectives: To evaluate ivacaftor’s effect in people with cystic fibrosis aged ≥6 years with 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H residual function mutations and to explore the correlation between ivacaftor-induced organoid-based cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function measurements and clinical response to ivacaftor.

Methods: Participants were randomized (1:1) in this placebo-controlled crossover study; each treatment sequence included two 8-week treatments with an 8-week washout period. The primary endpoint was absolute change in lung clearance index2.5 from baseline through Week 8. Additional endpoints included lung function, patient-reported outcomes, and in vitro intestinal organoid–based measurements of ivacaftor-induced cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function.

Results: Of 38 participants, 37 completed the study. The primary endpoint was met; the Bayesian posterior probability of improvement in lung clearance index2.5 with ivacaftor versus placebo was >99%. Additional endpoints improved with ivacaftor. Safety findings were consistent with ivacaftor’s known safety profile. Dose-dependent swelling was observed in 23 of 25 viable organoid cultures with ivacaftor treatment. Correlations between ivacaftor-induced organoid swelling and clinical endpoints were negligible to low.

Conclusions: In people with cystic fibrosis aged ≥6 years with a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H mutation, ivacaftor treatment improved clinical endpoints compared with placebo; however, there was no correlation between organoid swelling and change in clinical endpoints. The organoid assay may assist in identification of ivacaftor-responsive mutations but in this study did not predict magnitude of clinical benefit for individual people with cystic fibrosis with these two mutations.

Clinical trial registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03068312).

Keywords: residual function mutations, crossover studies, rectal organoids

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare, progressive, and lethal autosomal recessive disease with high morbidity and premature mortality (1, 2). Mutations in both alleles of the CFTR (CF transmembrane conductance regulator) gene lead to reduced quantity and/or function of the CFTR protein, resulting in reduced ion transport (1). Ivacaftor is a CFTR potentiator that enhances chloride transport in multiple mutant CFTR forms in vitro, including the G551D mutation, other gating mutations, and certain mutations associated with residual CFTR function (3–5). Residual CFTR function can result from a variety of molecular defects, including reduced and/or variable synthesis of CFTR channels, moderate defects in processing and trafficking, impaired channel gating, and altered channel conductance. These mutations result in sufficient CFTR protein quantity and/or function to allow some ion transport (3, 6, 7). Ivacaftor is indicated for the treatment of people with CF ≥4 months of age who have at least one mutation in the CFTR gene that is responsive to ivacaftor potentiation based on clinical and/or in vitro assay data in select regions (5), with geographic variation in the approved genotypes and ages indicated (8–10).

Residual function mutations are often associated with pancreatic sufficiency, and symptom onset generally occurs at a later age in people with these mutations than in people homozygous for the F508del mutation; however, the rate of disease progression in adulthood is similar regardless of CFTR genotype (11–13). People with CF who have residual function mutations are frequently (53–94%) pancreatic sufficient but often have impaired lung function on spirometry and elevated sweat chloride concentrations on sweat testing (11, 14, 15).

Residual function mutations are rare (16), and performing clinical trials in participants carrying a residual function mutation is challenging. Two of the most common residual function mutations, 3849 + 10kb C→T and D1152H (16), are associated with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry and are more common in Israel, with allelic frequency for 3849 + 10kb C→T and D1152H being ∼5% each (17). The 3849 + 10kb C→T mutation is characterized by a partially active splice site in intron 19 that leads to the insertion of a new 84–base pair exon that contains an in-frame stop codon between exons 19 and 20, resulting in both aberrant and normal CFTR transcripts (18, 19). In an in vitro model system using a panel of Fisher rat thyroid (FRT) cells, ivacaftor increased wild-type CFTR chloride transport in mutation forms associated with defects in protein processing (3, 4). Therefore, ivacaftor was expected to increase the function of the normal CFTR proteins derived from correctly spliced transcripts available at the cell surface in people with CF carrying the 3849 + 10kb C→T mutation. D1152H is a missense mutation that results in a normal or increased quantity of protein at the cell surface but reduced CFTR-mediated chloride transport. In vitro, ivacaftor is also known to increase chloride transport in D1152H-expressing FRT cells by 80.8% (3, 20).

In addition to the in vitro studies that suggest potential treatment benefits with ivacaftor, two clinical studies including participants with residual function mutations showed improved lung function and other efficacy outcomes with ivacaftor. The first was a phase 2 study in which participants with CF ≥12 years of age could have had a residual function mutation on the first allele and one on the second allele as well (21). The second was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 crossover trial in participants with CF ≥12 years of age with the F508del mutation on one allele and a CFTR mutation associated with residual CFTR function on the other allele (22). Although both of these previous studies evaluated several residual function mutations, and 3849 + 10kb C→T and D1152H were among the mutations eligible for inclusion, the results were grouped together, and data were not reported for individual mutations (21, 22). The current study aimed to further characterize the clinical response to ivacaftor in people with CF with either a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H mutation and with a variety of mutations in the second allele.

In studies of lung function in people with residual function mutations, sensitive methods are needed to capture airway disease because of the frequently milder disease phenotype at initial presentation. Therefore, the current study used multiple breath washout (MBW). MBW is able to detect early airway disease in people with CF more readily than spirometry—as has been demonstrated in children with CF (23). MBW can detect small airway abnormalities, whereas spirometry is rather insensitive to changes in the smaller airways.

There is growing interest in assays that may be used to evaluate new therapies and advance precision medicine initiatives (5, 24, 25). In vitro cell lines, including human bronchial epithelial cells and FRT cells, can provide crucial information on the impact of CFTR modulation on proteins expressed by several types of CFTR mutations (26–28). These cell lines have played a vital role in drug development, as well as drug approval, in select regions (5, 29). Assays are particularly needed to identify response in cases of rare mutations or mutations that cannot be characterized by other traditional methods, such as the splicing mutation 3849 + 10kb C→T (30, 31).

Intestinal organoids derived from rectal biopsies can be used as a tool to study the effect of CFTR mutations on mRNA splicing, protein processing and trafficking, and chloride channel function (31, 32). In an organoid model, forskolin-induced swelling (FIS) was reported to reflect the responsiveness of a mutation to a CFTR modulator (33). Ultimately, only clinical data can demonstrate a participant’s true response to therapy; this study aimed to explore the relationship between the result of the intestinal-derived organoid assay and clinical data and thus provide insight into the potential clinical utility of the organoid assay for predicting the extent of clinical benefits.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical effect of ivacaftor in people with CF ≥6 years of age with 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H residual function mutations and explore the correlation between ivacaftor-induced, organoid-based CFTR function measurements and clinical response to ivacaftor.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

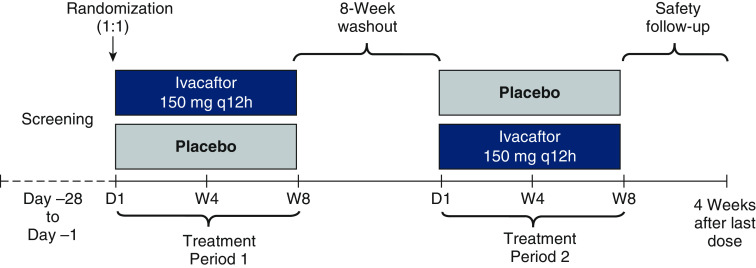

This was a phase 3b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center crossover study in people with CF ≥6 years of age with a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H CFTR gene mutation and percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (ppFEV1) of ≥40% and ≤105% at screening (NCT03068312). Participants were randomized (1:1) to one of two sequences (ivacaftor→placebo or placebo→ivacaftor) that included two 8-week treatment periods with ivacaftor (150 mg every 12 h) or matching placebo, separated by an 8-week washout period (Figure 1). Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in the online data supplement. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the independent ethics committee for the study center; all participants, parents, or guardians (as appropriate) provided written informed consent before participation.

Figure 1.

Study design. D = day; q12h = every 12 hours; W = week.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was absolute change in lung clearance index (LCI) at 2.5% of tracer gas concentration (LCI2.5) from baseline through Week 8 of ivacaftor or placebo. Secondary efficacy endpoints included absolute change in LCI at 5.0% of tracer gas concentration (LCI5.0), sweat chloride concentration, and ppFEV1 from baseline through 8 weeks of ivacaftor or placebo, and change in CF Questionnaire–Revised (CFQ-R) respiratory domain score from baseline at Week 8 of ivacaftor or placebo. The correlation between in vitro organoid-based swelling measurements and clinical response to ivacaftor was an additional prespecified, exploratory endpoint. Safety evaluations included incidence of adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory parameters, vital signs, and physical examinations. An AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence that developed or worsened during the study.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size calculation was based on achieving sufficient precision to estimate the average treatment difference through Week 8 in LCI2.5 between ivacaftor and placebo. Assuming a true SD of the paired differences of 1.00 in LCI2.5, a sample size of 50 participants would produce a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean treatment difference with a precision (margin of error) of 0.28 points. Similarly, the margin of error using a two-sided 80% CI would be 0.18 points. The study ultimately enrolled 38 participants.

Analyses of primary efficacy and additional efficacy endpoints were performed on the full analysis set, which was defined as all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study drug. The primary efficacy endpoint analysis was performed using the Bayesian posterior probability that the average treatment difference through Week 8 favored ivacaftor compared with placebo based on a prespecified minimum probability threshold of 80%. In Bayesian inference, the probability of a hypothesis before a study (prior probability) is updated after data are observed in the study (posterior probability); this approach provides a comprehensive posterior probability distribution of the average treatment difference that indicates the most likely values, probabilistically, of the average treatment difference, in contrast with the CI approach that provides only the range of plausible, equally likely values. A supportive analysis of the primary efficacy variable was performed using the frequentist CI based on a mixed-effects model for repeated measures. Subgroup analyses based on baseline ppFEV1 and CFTR gene mutation were also performed. Additional details are provided in the online supplement. For additional efficacy endpoints, the analyses were based on a mixed-effects model for repeated measures, and those details are also provided in the online supplement.

Safety analyses were performed on the safety set, which was defined as all participants who received at least one dose of study drug, using descriptive statistics.

Organoid-based Measurements (FIS Assay)

Rectal biopsies were collected from participants during screening at Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center and shipped to Hubrecht Organoid Technology, where the technology was developed and where organoid cultures were established as previously described (34). Briefly, organoid cultures were established using intestinal stem cells isolated and expanded from rectal biopsies of participants. Organoid swelling was measured with an FIS assay using approximately 30 experimental conditions (see online supplement). For each CFTR genotype group, a prespecified Pearson correlation analysis was performed as an exploratory endpoint on background-corrected area under the curve (AUC) of organoid swelling (for each experimental forskolin/VX-770 [ivacaftor] concentration) versus placebo-corrected change from baseline at Week 8 with ivacaftor treatment for specified clinical endpoints (LCI2.5, ppFEV1, and sweat chloride). Nominal P values were reported for testing the significance of the correlations.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Of 38 participants randomized, 19 were randomized to treatment sequence 1 (ivacaftor→placebo) and 19 were randomized to treatment sequence 2 (placebo→ivacaftor). All participants received at least one dose of the study medication (Table E1 in the online supplement). One participant prematurely discontinued the study drug in treatment period 2 because of pregnancy but completed the study. Thirty-seven participants completed the full assigned duration of dosing. Baseline demographics and characteristics are summarized in Table 1. At screening, most participants were ≥12 years of age and had a ppFEV1 of ≥60 percentage points.

Table 1.

Baseline participant demographics and characteristics

| Ivacaftor→Placebo (n = 19) | Placebo→Ivacaftor (n = 19) | Overall (N = 38) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, M, n (%) | 9 (47.4) | 9 (47.4) | 18 (47.4) |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD), yr | 32.6 (15.3) | 32.1 (15.6) | 32.3 (15.2) |

| <12 yr at screening, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 4 (10.5) |

| CFTR mutation, n (%) | |||

| 3849 + 10kb C→T | 11 (57.9) | 11 (57.9) | 22 (57.9) |

| D1152H | 8 (42.1) | 8 (42.1) | 16 (42.1) |

| ppFEV1 <60% at screening, n (%) | 4 (21.1) | 4 (21.1) | 8 (21.1) |

| LCI2.5, mean (SD) | 12.74 (4.04) | 13.19 (5.45) | 12.96 (4.74) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 24.3 (3.7) | 23.5 (3.4) | 23.9 (3.5) |

| ppFEV1, mean (SD), percentage points | 74.8 (17.6) | 73.1 (16.5) | 74.0 (16.9) |

| Sweat chloride concentration, mean (SD), mmol/L | 50.6 (23.9) | 47.6 (24.7) | 49.1 (24.0) |

| CFQ-R respiratory domain score, mean (SD), points | 61.1 (20.3) | 63.5 (20.6) | 62.3 (20.3) |

| LCI5.0, mean (SD) | 7.76 (2.03) | 7.71 (2.32) | 7.73 (2.15) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CFQ-R = Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised; CFTR = cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; LCI2.5 = lung clearance index at 2.5% of tracer gas concentration; LCI5.0 = lung clearance index at 5.0% of tracer gas concentration; ppFEV1 = percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second; SD = standard deviation.

Efficacy Results

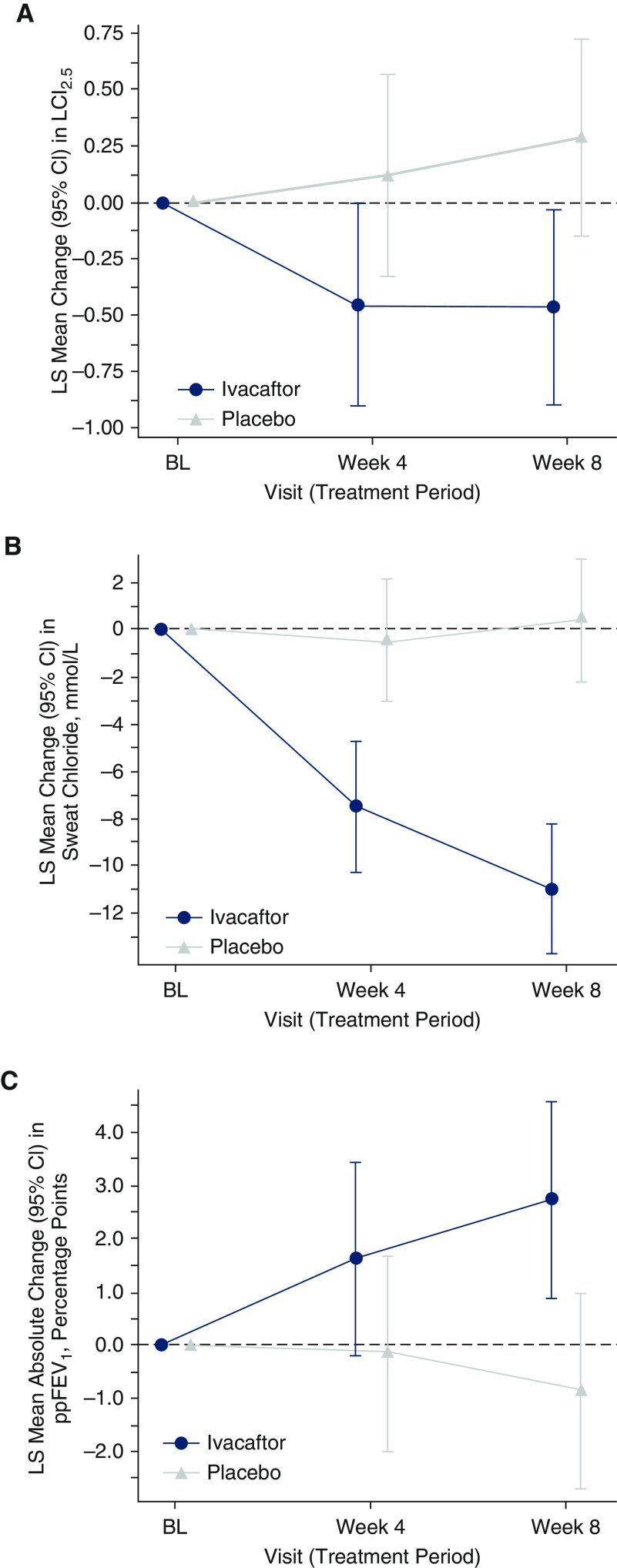

The primary endpoint of absolute change in LCI2.5 from baseline through Week 8 demonstrated improvement with ivacaftor versus placebo; the Bayesian analysis showed a >99% posterior probability for the average treatment difference between ivacaftor and placebo to be <0 (a probability >80% was defined as the criterion for improvement), with a posterior mean (SD) difference between ivacaftor and placebo of −0.68 (0.23) (Table 2). The median (25th percentile to 75th percentile) of the posterior probability distribution of the average treatment difference was −0.68 (−0.83 to −0.53); the range of values between the percentiles provides the most credible values of the average treatment difference. In a supportive analysis, the least squares mean of the average treatment difference in the change in LCI2.5 from baseline through Week 8 of treatment with ivacaftor versus placebo was −0.66 (95% CI, −1.10 to −0.21) (Figure 2A). Prespecified exploratory subgroup analyses of the primary endpoint showed a similar trend that favored ivacaftor treatment regardless of baseline ppFEV1 (<60% vs. ≥60%) and CFTR genotype (3849 + 10kb C→T versus D1152H). The least squares mean (95% CI) of the average treatment difference in the change in LCI2.5 from baseline through Week 8 was −1.19 (−2.42 to 0.04) versus −0.57 (−1.07 to −0.06) for ppFEV1 <60% versus ≥60%, respectively, and −0.56 (−1.21 to 0.10) versus −0.93 (−1.51 to −0.34) for CFTR genotype 3849 + 10kb C→T versus D1152H, respectively (Table E2).

Table 2.

Primary and supportive analyses of change in LCI2.5 from baseline through Week 8 of treatment with ivacaftor or placebo

| LCI2.5 | Placebo (n = 38) | Ivacaftor (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 13.0 (4.7) |

|

| Bayesian analysis | ||

| Posterior probability that the average treatment difference (ivacaftor vs. placebo) from baseline through Week 8 is <0 | 0.9976 |

|

| Posterior mean of average treatment difference (SD) | −0.68 (0.23) |

|

| Posterior median of average treatment difference (25th percentile to 75th percentile) | −0.68 (−0.83 to −0.53) |

|

| Change from baseline through Week 8, LS mean (95% CI) | n = 37 | n = 37 |

| 0.20 (−0.17 to 0.57) | −0.46 (−0.83 to −0.09) | |

| Treatment difference, LS mean (95% CI) | −0.66 (−1.10 to −0.21) | |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; LCI2.5 = lung clearance index at 2.5% of tracer gas concentration; LS = least squares; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Least squares mean change from baseline by visit through Week 8 in (A) lung clearance index at 2.5% of initial tracer gas concentration, (B) sweat chloride concentration, and (C) percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second. BL = baseline; CI = confidence interval; LCI2.5 = lung clearance index at 2.5% of initial tracer gas concentration; LS = least squares; ppFEV1 = percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Additional endpoints also demonstrated improvements in the change from baseline through Week 8 with ivacaftor treatment versus placebo (Table 3 and Figures 2B and 2C). The least squares mean (95% CI) of the average treatment difference between ivacaftor and placebo was −9.2 mmol/L (−12.4 to −5.9 mmol/L) for the change in sweat chloride concentration, −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1) for the change in LCI5.0, and 2.7 percentage points (0.6 to −4.7) for the change in ppFEV1. Substantial improvement in the CFQ-R respiratory domain score was observed in participants receiving ivacaftor compared with those receiving placebo, with a least squares mean (95% CI) difference in change from baseline at Week 8 in CFQ-R respiratory domain score of 18.7 (12.5 to −25.0).

Table 3.

MMRM analysis of absolute change from baseline in additional efficacy endpoints through/at Week 8

| Change from Baseline*† | Placebo (N = 38) | Ivacaftor (N = 38) | Difference, Ivacaftor vs. Placebo |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCI5.0 through Week 8, LS mean (95% CI) | n = 37 | n = 37 | |

| 0.13 (−0.06 to 0.32) | −0.16 (−0.34 to 0.03) | −0.28 (−0.48 to −0.08) | |

| Sweat chloride concentration through Week 8, LS mean (95% CI), mmol/L | n = 38 | n = 36 | |

| −0.1 (−2.4 to 2.3) | −9.3 (−11.7 to −6.8) | −9.2 (−12.4 to −5.9) | |

| ppFEV1 through Week 8, LS mean (95% CI), percentage points | n = 36 | n = 38 | |

| −0.5 (−2.1 to 1.2) | 2.2 (0.6 to 3.8) | 2.7 (0.6 to 4.7) | |

| CFQ-R respiratory domain score at Week 8, LS mean (95% CI), points | n = 38 | n = 37 | |

| −1.7 (−6.3 to 3.0) | 17.1 (12.4 to 21.8) | 18.7 (12.5 to 25.0) |

Definition of abbreviations: CFQ-R = Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised; CI = confidence interval; LCI5.0 = lung clearance index at 5.0% of tracer gas concentration; LS = least squares; MMRM = mixed-effects model for repeated measures; ppFEV1 = percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

CFQ-R respiratory domain score was evaluated at Week 8; other efficacy endpoints were evaluated through Week 8.

Baseline was defined as the most recent nonmissing measurement before the first dose of study medication in treatment period 1. Change from baseline through Week 8 was assessed using the MMRM, with treatment, visit (period), treatment*visit (period), and period as fixed effects and baseline outcome as a covariate.

Safety Results

Overall, AEs were reported in 22 participants (57.9%) treated with ivacaftor and 22 (57.9%) treated with placebo (Table E3). There were no deaths in this study. AEs leading to study drug interruption occurred in one participant receiving ivacaftor and one participant receiving placebo. No participant had an AE resulting in study drug discontinuation. Most AEs were consistent with manifestations of CF and ivacaftor treatment and were mild or moderate in severity. Serious AEs occurred in three participants (7.9%) overall, one of whom was receiving ivacaftor (spontaneous abortion) and two of whom were receiving placebo (one infective pulmonary exacerbation of CF; one pancreatitis).

Organoid Measurements (Exploratory Analysis)

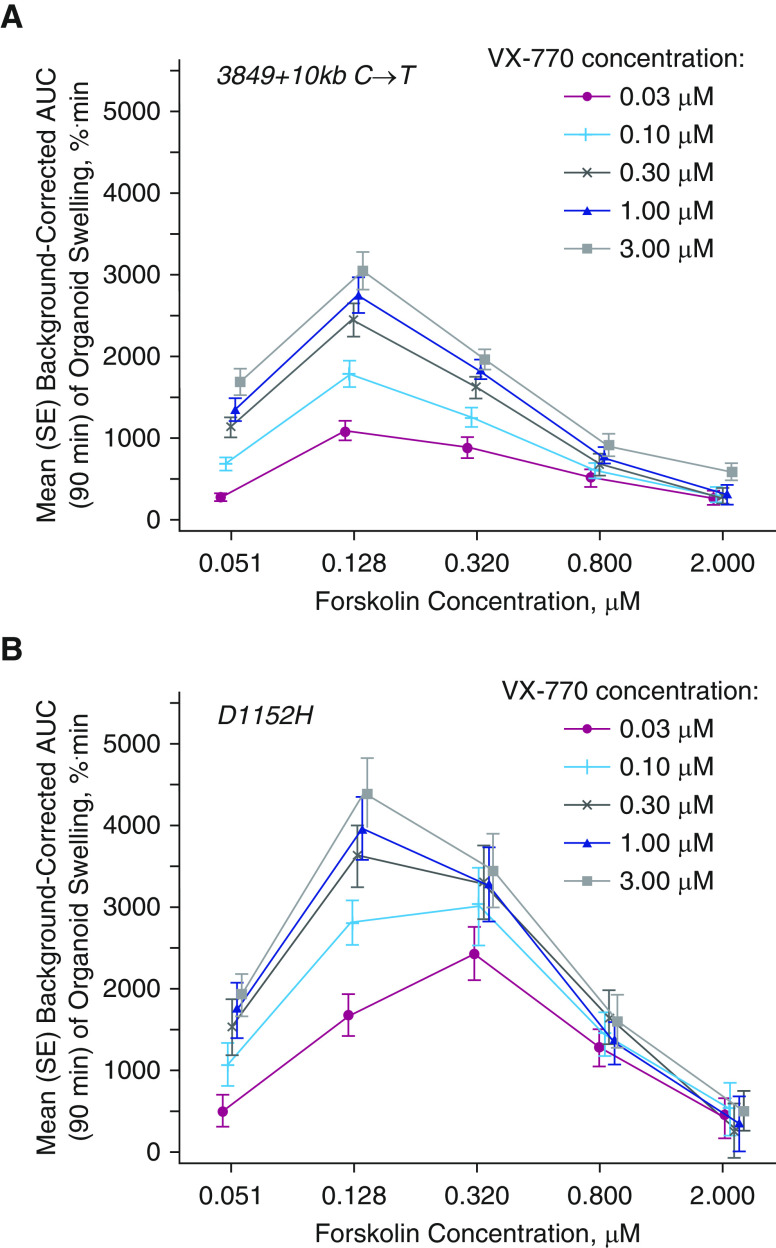

Twenty-nine organoid cultures were successfully established from 33 biopsies (Figure E1). Four of these did not meet quality control standards, resulting in 25 viable organoid cultures for the planned assays. These 25 viable organoid cultures with a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H mutation had highly reproducible FIS assay results. At baseline, organoids generally exhibited dose-dependent swelling with increasing concentrations of forskolin, which activates the CFTR channel, consistent with the fact that these mutations have residual CFTR function (Figure E2). These forskolin-only data were used for background correction of the swelling response to treatment with VX-770. Organoids from participants in this crossover study generally demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in background-corrected AUC of swelling with VX-770 treatment (Figure 3). As expected, most organoid cultures showed a high degree of AUC swelling response to VX-770, but some individual organoid cultures were variable, with two organoid cultures carrying the 3849 + 10kb C→T mutation showing limited response (data not shown). A Pearson correlation analysis showed no evidence of correlation between the degree of background-corrected AUC of organoid swelling and that of placebo-corrected change from baseline response in clinical endpoints (Table 4). More specifically, the extent of swelling of organoids derived from participants with either a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H mutation, as measured by the FIS assay, did not correlate with the magnitude of any of the individual clinical responses for LCI2.5, sweat chloride, or ppFEV1 in participants who received ivacaftor for 8 weeks.

Figure 3.

Dose–response curve of mean background-corrected area under the curve of organoid swelling versus forskolin concentration by VX-770 dose for (A) 3849 + 10kb C→T (n = 16) and (B) D1152H mutations (n = 9). Each point represents the average background-corrected area under the curve of organoid swelling at corresponding forskolin and VX-770 concentrations. AUC = area under the curve; SE = standard error.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation between background-corrected AUC of organoid swelling and placebo-corrected change from baseline in clinical endpoint at Week 8 of VX-770 treatment by genotype and experimental condition

| Clinical Endpoint | Statistic | Genotype |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3849 + 10kb C→T (n = 16) | D1152H (n = 9) | |||

| LCI2.5 | n | 13 |

8 | |

| Pearson correlation* | −0.44 |

0.53 | ||

| P value | 0.13 |

0.18 | ||

| Sweat chloride concentration | n | 14 |

8 | |

| Pearson correlation* | −0.33 |

0.21 | ||

| P value | 0.24 |

0.62 | ||

| ppFEV1 | n | 14 |

7 | |

| Pearson correlation* | −0.07 |

−0.23 | ||

| P value | 0.81 | 0.63 | ||

Definition of abbreviations: AUC = area under the curve; LCI2.5 = lung clearance index at 2.5% of tracer gas concentration; ppFEV1 = percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Pearson correlations are presented for a single experimental condition (forskolin, 0.128 μM; VX-770, 3.0 μM). This experimental condition demonstrated the largest average swelling for both mutations (Figure E2).

Discussion

Clinical Data

The data presented here further characterize the clinical response to ivacaftor in people with CF who are ≥6 years of age with either a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H mutation. Ivacaftor led to improvements in all primary and additional secondary endpoints versus placebo through (or at) 8 weeks of treatment. The primary efficacy endpoint analysis for LCI2.5, based on a Bayesian approach, yielded a >99% posterior probability that the average treatment difference between ivacaftor and placebo was <0 (and −0.83 to −0.53 as the range of the most credible values of the average treatment difference). The subgroup analyses indicated that compared with participants with a 3849 + 10kb C→T mutation, those with a D1152H mutation had a larger least squares mean improvement in LCI2.5. This may be attributed to differences in CFTR potentiation by ivacaftor for the two mutations. In people with the 3849 + 10kb C→T mutation, ivacaftor increases ion transport by wild-type CFTR protein—the concentration of which is likely to be relatively low. However, in people with the D1152H mutation, ivacaftor increases ion transport by the mutated CFTR protein—the concentration of which is likely to be relatively high. The safety profile in this study was consistent with the known safety profile of ivacaftor.

Residual function mutations are often associated with higher ppFEV1 compared with other types of CFTR mutations (11, 12); because many participants had normal or near-normal ppFEV1, we used the LCI measure of pulmonary function that has demonstrated treatment differences in previous studies in people with CF with ppFEV1 of >70% (35–37). Previous clinical trials of CFTR modulators in people with CF have reported treatment differences for LCI2.5 with least squares means in a range similar to that in the current study, as follows: −0.2 at 2 weeks (21), −2.2 average at 2–4 weeks (35), −1.1 through 24 weeks (36), and −1.1 mean change at Week 4 and −0.9 mean change at Week 24 (38). Note that 21% of participants enrolled in this study had baseline ppFEV1 of <60%. Improvements in LCI2.5 in these participants were directionally consistent with the mean improvement demonstrated in all participants in this study and greater than that in participants with ppFEV1 of ≥60% (Table E2). These data suggest that LCI may be a useful tool for measuring the impact of CFTR modulation in people with CF with low baseline ppFEV1, a population in which LCI has been less frequently used; this has been based both on lack of need (i.e., ppFEV1 being more sensitive in this group than in those with milder disease) and practicality (washouts take longer in more severe disease) (39).

Sweat chloride concentrations were reduced, on average, by 8 weeks of ivacaftor treatment. This is notable considering that some participants had near-normal sweat chloride concentrations at baseline and sweat chloride concentrations might not be expected to decrease in such participants.

In addition to the improvement in lung function, ivacaftor demonstrated substantial and clinically meaningful improvement in a patient-reported outcome. Participants treated with ivacaftor had a 17.1-point mean improvement in their CFQ-R respiratory domain score, a substantial increase that was well above the 4.0-point minimal clinically important difference (40).

Organoid Assays

When assessed as an overall population, the organoids from participants with the mutations studied demonstrated a swelling response, supporting the utility of organoids to identify responsive mutations at the population level, similar to other assay systems commonly used in CF (e.g., human bronchial epithelial and FRT cell lines) (3). However, the data in this study also demonstrated that individual organoid swelling was not useful for identifying individual people with CF who will respond to targeted therapies based on individual magnitudes of response. A previous study demonstrated that organoid swelling in the presence of VX-770 was positively correlated with clinical change in ppFEV1 when pooled participant outcomes from different populations were compared with preclinical in vitro results from different participants (31). An additional aim of this data collection was to determine whether organoid swelling is predictive of outcome on an individual level (e.g., whether a participant with a greater degree of FIS in the organoid assay also has a greater clinical response). To this end, Berkers and colleagues (33) recently published an analysis correlating ex vivo organoid swelling response to in vivo sweat chloride and ppFEV1 responses to CFTR modulation, in which the results suggested that the organoid outcome is predictive of clinical outcome in individuals. No swelling threshold was defined to determine response (33). In contrast, the results from the current study did not show a correlation at the individual participant level between organoid swelling response to ivacaftor and clinical response to ivacaftor treatment as measured by sweat chloride, ppFEV1, or LCI2.5. For the forskolin-only organoid swelling used for background correction, the individual biological variation at baseline precludes meaningful comparisons of background swelling between groups of participants with different baseline characteristics. A previous analysis of changes in sweat chloride concentrations and ppFEV1 in people with CF treated with ivacaftor found that in individuals, reductions in sweat chloride concentrations did not predict improvements in ppFEV1 but that there was a significant correlation between those outcomes at a population level (41).

Study Limitations

Participants were evaluated at a single center, and the sample size was comparatively small (38 participants), which may limit extrapolation of the findings to the overall population with CF. However, because of the low prevalence of these mutations (16), enrolling more participants would have been challenging. Despite these limitations, the overall clinical data are consistent with previous reports of improvements in lung function and other clinical outcomes with ivacaftor therapy in people with CF and a residual function mutation (21, 22).

The crossover design of the study enabled within-subject comparison of the effects of ivacaftor treatment on multiple endpoints. Use of the crossover design increased the power of the study to detect an improvement in efficacy endpoints in this rare participant population.

Viable organoid cultures were obtained from 25 of the 38 studied participants, which may further limit the generalizability of the findings. This sample size, however, is consistent with the sample size of other organoid studies (31, 33). Limitations inherent to in vitro assays, including true biological variability such as the variability in the quantity of correctly spliced 3849 + 10kb C→T by biopsy tissue organ type (42), may have affected the interpretability of the correlation results. Given that organoids were derived from rectal tissue, it is plausible that these organoids were not predictive of clinical response to ivacaftor (as measured by LCI2.5 and ppFEV1) because of potential variability in splicing between rectal and lung tissues. RNA concentrations in organoids derived from gastrointestinal tissue will not necessarily represent the RNA concentration in the respiratory system (42). Therefore, CFTR function in the intestine may not provide an accurate prediction of the response in lung function induced by CFTR modulator therapy.

Conclusions

This study further characterized the clinical response to ivacaftor in people with CF with a 3849 + 10kb C→T or D1152H mutation. In this 8-week study, improvements in lung function measured by LCI2.5 were seen in participants. Ivacaftor treatment resulted in improvements over placebo in other outcomes, such as LCI5.0, sweat chloride concentrations, ppFEV1, and CFQ-R respiratory domain score. These findings were consistent with a previous phase 3 study demonstrating the clinical benefit of ivacaftor in people with CF with residual function mutations and F508del on the other allele (22). Overall safety findings were consistent with underlying CF disease and the known safety profile of ivacaftor.

Organoids may serve as a complementary tool to the FRT assay and other current in vitro assessment methods and present an opportunity for testing mutations that are not available in current in vitro assays (e.g., splice mutations or large insertions or deletions). In this study, the organoid assay findings demonstrated responsiveness of these mutations to ivacaftor, which translated into clinical benefit; however, there was no evidence of correlation between the degree of organoid swelling and magnitude of change in clinical endpoints in individual participants. Together, these results suggest that the organoid assay may assist in identification of ivacaftor-responsive variants but may not be able to predict the magnitude of clinical benefit for the individual person with CF. Further work is required to fully understand the role of organoid assays given the remaining goal of providing effective therapies for people with CF with mutations not currently indicated for existing modulator therapy.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the people with cystic fibrosis and their families for their contributions to the trial. They also thank the physicians from all Israeli cystic fibrosis centers, especially Professor Lea Bentur, Professor Hannah Blau, Dr. Huda Mussaffi, Dr. Michal Shteinberg, Dr. Galit Livnat, Professor Ori Efrati, and Professor Micha Aviram for referring their patients to the study. Hanna Leah Cohen-Knafou, Dinah Barros, and Hava Berros of the Hadassah Cystic Fibrosis Center were responsible for carrying out all study-related procedures. The authors thank Sylvia Boj, Ph.D., Jasper Mullenders, Ph.D., and the other members of Hubrecht Organoid Technology for their assistance with the organoid technology. Editorial coordination and support were provided by Tejendra R. Patel, Pharm.D., of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by JoAnna Anderson, Ph.D., and Amos Race, Ph.D., of ArticulateScience LLC, which received funding from Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Footnotes

Supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc., which also participated in the design, statistical analysis, and interpretation of the data, and provided editorial and writing assistance.

Author Contributions: E.K. and the study sponsor collaborated on the conception and design of the study. E.K., M.C.-C., R.T., M.W., J.R., D.S., A.G.-H., and T.P. performed data collection. E.K., J.C.D., C. Short., and C. Saunders conducted the training/certification of staff for lung clearance index measures and provided data overreading. All authors had access to the data, were involved in the interpretation of the data, contributed to the development of the draft, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement: Vertex is committed to advancing medical science and improving the health of people with cystic fibrosis. This includes the responsible sharing of clinical trial data with qualified researchers. Proposals for the use of these data will be reviewed by a scientific board. Approvals are at the discretion of Vertex and will be dependent on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, and the intended use of the data. Please contact CTDS@vrtx.com if you would like to submit a proposal or need more information.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Ratjen F, Bell SC, Rowe SM, Goss CH, Quittner AL, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15010. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKenzie T, Gifford AH, Sabadosa KA, Quinton HB, Knapp EA, Goss CH, et al. Longevity of patients with cystic fibrosis in 2000 to 2010 and beyond: survival analysis of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:233–241. doi: 10.7326/M13-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Goor F, Yu H, Burton B, Hoffman BJ. Effect of ivacaftor on CFTR forms with missense mutations associated with defects in protein processing or function. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu H, Burton B, Huang CJ, Worley J, Cao D, Johnson JP, Jr, et al. Ivacaftor potentiation of multiple CFTR channels with gating mutations. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. Boston, MA: Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2020. Kalydeco (ivacaftor) [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clancy JP. Rapid therapeutic advances in CFTR modulator science. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53:S4–S11. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellani C, Cuppens H, Macek M, Jr, Cassiman JJ, Kerem E, Durie P, et al. Consensus on the use and interpretation of cystic fibrosis mutation analysis in clinical practice. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7:179–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vertex Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Dublin, Ireland: Vertex Pharmaceuticals (Ireland) Ltd.; 2020. Kalydeco (ivacaftor) [summary of product characteristics] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vertex Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Tel Aviv, Israel: Vertex Pharmaceuticals (UK) Ltd.; 2020. Kalydeco (ivacaftor) [physician prescribing information] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. Toronto, Canada: Vertex Pharmaceuticals (Canada) Inc; 2019. Kalydeco (ivacaftor) [product monograph] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duguépéroux I, De Braekeleer M. The CFTR 3849+10kbC->T and 2789+5G->A alleles are associated with a mild CF phenotype. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:468–473. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.10100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKone EF, Emerson SS, Edwards KL, Aitken ML. Effect of genotype on phenotype and mortality in cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361:1671–1676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagener JS, Millar SJ, Mayer-Hamblett N, Sawicki GS, McKone EF, Goss CH, et al. Lung function decline is delayed but not decreased in patients with cystic fibrosis and the R117H gene mutation. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgel PR, Fajac I, Hubert D, Grenet D, Stremler N, Roussey M, et al. Non-classic cystic fibrosis associated with D1152H CFTR mutation. Clin Genet. 2010;77:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terlizzi V, Carnovale V, Castaldo G, Castellani C, Cirilli N, Colombo C, et al. Clinical expression of patients with the D1152H CFTR mutation. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Johns Hopkins University. The Clinical and Functional TRanslation of CFTR (CFTR2) 2020 [accessed 2020 Jun 6]. Available from: https://www.cftr2.org.

- 17.Orgad S, Neumann S, Loewenthal R, Netanelov-Shapira I, Gazit E. Prevalence of cystic fibrosis mutations in Israeli Jews. Genet Test. 2001;5:47–52. doi: 10.1089/109065701750168725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Highsmith WE, Burch LH, Zhou Z, Olsen JC, Boat TE, Spock A, et al. A novel mutation in the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with pulmonary disease but normal sweat chloride concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:974–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410133311503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiba-Falek O, Kerem E, Shoshani T, Aviram M, Augarten A, Bentur L, et al. The molecular basis of disease variability among cystic fibrosis patients carrying the 3849+10 kb C-->T mutation. Genomics. 1998;53:276–283. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; CFTR mutation classes. 2017 [accessed 2020 Jun 6] Available from: https://www.cff.org/Care/Clinician-Resources/Network-News/August-2017/Know-Your-CFTR-Mutations.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nick JA, St Clair C, Jones MC, Lan L, Higgins M VX12-770-113 Study Team. Ivacaftor in cystic fibrosis with residual function: lung function results from an N-of-1 study. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe SM, Daines C, Ringshausen FC, Kerem E, Wilson J, Tullis E, et al. Tezacaftor-ivacaftor in residual-function heterozygotes with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2024–2035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aurora P, Bush A, Gustafsson P, Oliver C, Wallis C, Price J, et al. London Cystic Fibrosis Collaboration. Multiple-breath washout as a marker of lung disease in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:249–256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-895OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. Boston, MA: Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2018. Symdeko (tezacaftor/ivacaftor and ivacaftor) [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amaral MD, de Boeck K ECFS Strategic Planning Task Force on ‘Speeding up access to new drugs for CF’. Theranostics by testing CFTR modulators in patient-derived materials: the current status and a proposal for subjects with rare CFTR mutations. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, et al. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18825–18830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904709106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, González J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, et al. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1117–L1130. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue X, Mutyam V, Tang L, Biswas S, Du M, Jackson LA, et al. Synthetic aminoglycosides efficiently suppress cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator nonsense mutations and are enhanced by ivacaftor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50:805–816. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0282OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durmowicz AG, Lim R, Rogers H, Rosebraugh CJ, Chowdhury BA. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s experience with ivacaftor in cystic fibrosis: establishing efficacy using in vitro data in lieu of a clinical trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:1–2. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201708-668PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amato F, Scudieri P, Musante I, Tomati V, Caci E, Comegna M, et al. Two CFTR mutations within codon 970 differently impact on the chloride channel functionality. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:742–748. doi: 10.1002/humu.23741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dekkers JF, Berkers G, Kruisselbrink E, Vonk A, de Jonge HR, Janssens HM, et al. Characterizing responses to CFTR-modulating drugs using rectal organoids derived from subjects with cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:344ra84. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad8278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fidler MC, Sullivan JC, Boj SF, Vries R, Munck A, Higgins M, et al. Evaluation of the contributions of splicing and gating defects to dysfunction of G970R-CFTR. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16:S31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkers G, van Mourik P, Vonk AM, Kruisselbrink E, Dekkers JF, de Winter-de Groot KM, et al. Rectal organoids enable personalized treatment of cystic fibrosis. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1701–1708, e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dekkers JF, Wiegerinck CL, de Jonge HR, Bronsveld I, Janssens HM, de Winter-de Groot KM, et al. A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nat Med. 2013;19:939–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies J, Sheridan H, Bell N, Cunningham S, Davis SD, Elborn JS, et al. Assessment of clinical response to ivacaftor with lung clearance index in cystic fibrosis patients with a G551D-CFTR mutation and preserved spirometry: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:630–638. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratjen F, Hug C, Marigowda G, Tian S, Huang X, Stanojevic S, et al. VX14-809-109 investigator group. Efficacy and safety of lumacaftor and ivacaftor in patients aged 6-11 years with cystic fibrosis homozygous for F508del-CFTR: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:557–567. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chilvers M, Tian S, Marigowda G, Bsharat M, Hug C, Solomon M, et al. An open-label extension (EXT) study of lumacaftor/ivacaftor (LUM/IVA) therapy in patients (pts) aged 6–11 years (yrs) with cystic fibrosis (CF) homozygous for F508del-CFTR. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16:52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milla CE, Ratjen F, Marigowda G, Liu F, Waltz D, Rosenfeld M VX13-809-011 Part B Investigator Group. Lumacaftor/ivacaftor in patients aged 6–11 years with cystic fibrosis and homozygous for F508del-CFTR. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:912–920. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuchs SI, Gappa M, Eder J, Unsinn KM, Steinkamp G, Ellemunter H. Tracking Lung Clearance Index and chest CT in mild cystic fibrosis lung disease over a period of three years. Respir Med. 2014;108:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quittner AL, Modi AC, Wainwright C, Otto K, Kirihara J, Montgomery AB. Determination of the minimal clinically important difference scores for the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised respiratory symptom scale in two populations of patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection. Chest. 2009;135:1610–1618. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fidler MC, Beusmans J, Panorchan P, Van Goor F. Correlation of sweat chloride and percent predicted FEV1 in cystic fibrosis patients treated with ivacaftor. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16:41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiba-Falek O, Parad RB, Kerem E, Kerem B. Variable levels of normal RNA in different fetal organs carrying a cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator splicing mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1998–2002. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9808012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]