Abstract

Background

Quality of maternal and newborn care is integral to positive clinical, social and psychological outcomes. Respectful care is an important component of this but is suboptimum in many low-income settings. A renewed energy among health professionals and academics is driving an international agenda to eradicate disrespectful health facility care around the globe. However, few studies have explored respectful care from different vantage points.

Methods

We used Strauss and Corbin’s grounded theory methodology to explore intrapartum experiences in Tanzania and Zambia. In-depth interviews were conducted with 98 participants (48 women, 18 partners, 21 health-providers and 11 key stakeholders), resulting in data saturation. Analysis involved constant comparison, comprising three stages of coding: open, axial and selective. The process involved application of memos, reflexivity and positionality.

Results

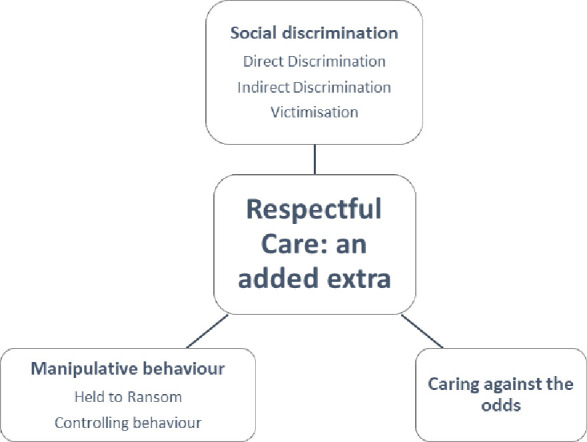

Findings demonstrated that direct and indirect social discrimination led to inequity of care. Health-providers were believed to display manipulative behaviours to orchestrate situations for their own or the woman’s benefit, and were often caring against the odds, in challenging environments. Emergent categories were related to the core category: respectful care, an added extra, which reflects the notion that women did not always expect or receive respectful care, and tolerated poor experiences to obtain services believed to benefit them or their babies. Respectful care was not seen as a component of good quality care, but a luxury that only some receive.

Conclusion

Both quality of care and respectful care were valued but were not viewed as mutually inclusive. Good quality treatment (transactional care) was often juxtaposed with disrespectful care; with relational care having a lower status among women and healthcare providers. To readdress the balance, respectful care should be a predominant theme in training programmes, policies and audits. Women’s and health-provider voices are pivotal to the development of such interventions.

Keywords: maternal health, obstetrics, qualitative study

Key questions.

What is already known?

The WHO’s Quality of Care Framework for Maternal and Newborn Health specifically highlights respectful care as a core component.

Existing evidence suggests that disrespectful maternity care remains an issue in facilities in many low-income settings.

What are the new findings?

Respectful care is marginalised by women and health-providers who give greater priority to the ‘delivery’ of care, as opposed to the ‘experience’ of care.

Social discrimination underpins the perpetuation of disrespectful care, through conscious and unconscious health-provider bias.

Understanding health-provider influences for providing suboptimal care is integral to altering behaviour.

What do the new findings imply?

These findings provide a better understanding of the inherent challenges of eradicating disrespectful health facility care in low-income settings; with emphasis on the need to understand women’s and health-provider motivations simultaneously.

There is a need to elevate the status of respectful care, which is currently hidden within quality of care frameworks.

Future programmes should consider mandatory conscious and unconscious bias training for all health-providers, underpinned by women’s narratives.

Background

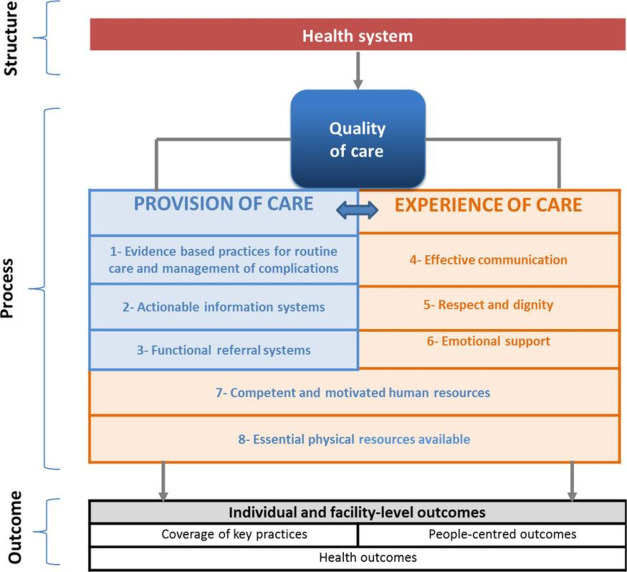

The WHO developed a framework for maternal and newborn wellbeing1 (figure 1) to conceptualise quality of care.

Figure 1.

Quality of care framework.

The framework gives equal precedence to ‘provider’ and ‘experience’ domains. Respect and dignity are included in the ‘experience’ domain, alongside effective communication and emotional support. This framework acts as a foundation for the more recent WHO intrapartum care guidelines,2 and signifies an important paradigm shift, representing international acknowledgement of ‘positive childbirth experience’ as an important outcome. These guidelines also reflect the ethos that respectful care is a fundamental human right for women and their babies.3

Despite advocacy for better childbirth care and universal desire among women regardless of geographical location,4 5 experiences remain variable across the globe. A systematic qualitative review4 of 35 papers across 19 countries concluded that a positive experience which met or exceeded expectations was a priority to women; they wished to give birth in a safe and supportive environment which resulted in a healthy baby. A further systematic review6 of 54 papers found that, in low-income countries, women’s satisfaction was influenced by maternity structures (environment and resources), processes (care, relationships and emotional support) and outcomes (mothers’ and babies’ health status). The process of care was the main determinant of satisfaction, with much of the available evidence relating to health-provider behaviour; a core element of which is disrespectful care. Findings of a recent study of 4358 women7 in Mozambique concur with the review findings; isolation, disrespect, humiliation and physical abuse during care being identified as important predictors of dissatisfaction.

Substantial evidence shows that disrespect and abuse remain prevalent in low-income countries.8 A review of 65 studies, across 34 countries found that mistreatment presented as physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional care standards, poor woman-provider rapport and health system dysfunctions and constraints.8 Although disrespectful care has been condemned for decades,9 a qualitative review10 identified sub-Saharan Africa as one of the main areas where disrespectful childbirth care continues.

Disrespectful care negatively impacts on childbirth experiences10 and actively deters women from attending health facilities,11 compromising care when services are available. Timely access to care is important in low-income countries as delays are a major factor in poor outcomes, with near-miss events being high in these countries.12

Although much is written on women’s intrapartum experiences in high-income 13 14 and low-income15 16 settings, most studies have either concentrated on specific populations, for example, women experiencing HIV17 18 or on enablers and barriers to providing high-quality care.16 A recent qualitative review of facility-based care in sub-Saharan Africa19 highlighted the lack of ‘broader, interdisciplinary perspectives’ on provision of respectful care as a critical gap in the current literature. Our research addresses this gap by exploring care through multiple lenses enabling a more comprehensive understanding of relational contributors to experiences. Thus, our study aimed to explore the intrapartum experiences of women, partners, different health-providersand key stakeholders.

Methods

Study design

This study adopted a qualitative grounded-theory approach; informed by Symbolic Interactionism.20 This methodology enabled understanding of the impact of verbal and non-verbal social interactions on the experiences and views of participants. Although much has been written on intrapartum care, published literature has tended to focus on individual sample groups, for example, midwives19 or women.4 The grounded-theory approach enabled the emergence of new understandings of the interactive processes of the different actors, and their contributions to the emergent theory. The Straussian approach21 supported an iterative and inductive process to systematically generate theory to explore and explain the phenomenon of intrapartum care in two low-income countries. Importantly, for our study, this approach21 adopts a subjectivisty epistemology acknowledging the influence of the researchers (all health professionals), but utilises constant comparison between what is known through the literature and personal experiences alongside the data, codes, categories and memos to continually check the grounding of emerging insights.

Ethics

Approval was obtained from The University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee 3 (reference 2018-4446-6653), UK; CUHAS/BMC Joint Ethical and Review Committee, Tanzania (reference CREC/287/2018) and ERES Converge IRB, Zambia (reference 2018/June 029). All participants provided written (or thumb print) informed consent.

Study setting

The study took place in Tanzania (Lake Zone) and Zambia (Luapula Province); low-income settings with high burdens of disease.22 Participants were recruited from primary, secondary and tertiary facilities, in each country, that is, six facilities; the majority were living in rural or semirural locations. During data collection, the national stillbirth rates for Tanzania and Zambia were 21/1000 and 22/1000 births,23 with neonatal deaths at 21/1000 and 23.5/1000, respectively.24

Sample

An initial purposive sample of three participants per country, in each of the following groups were recruited.

Pregnant women with no known complications in the second or third gestational period.

Postnatal women (2–12 weeks post-birth) with a live baby, a stillborn baby or following a near-miss mortality.12

Male partners of postnatal women (their female partner may or may not have been interviewed).

Health-providers (midwives, nurses, doctors Traditional Birth Attendants (TBA)) actively working in the study settings supporting maternal and newborn care.

Key stakeholders (village elders, religious leaders, community members, policy-makers), all of whom reside in the geographical location of the study settings and contribute to local maternal and newborn health decision-making.

After the initial purposive sample, data retrieval was directed by theoretical sampling. Simultaneous data collection and analysis enabled the initial findings to inform the targeting of subsequent participants and to widen the scope of the existing interview questions. Analysis of early responses indicated the need for broader perspective on respectful and relational care, leading to the inclusion of additional women and health-providers and partners of women who had birthed a stillborn baby. The total sample included can be seen in table 1. The interview questions were expanded to include prompts regarding relationships, as respectful care was emerging as an important category. Interviews continued until data saturation was reached, that is, when the research team agreed that no new codes were emerging from the data and participants were failing to provide any new perspectives.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Tanzania | Zambia | |||||

| Women | Partner | Health worker | Women | Partner | Heath worker | |

| n=21 | n=7 | n=9 | n=27 | n=9 | n=12 | |

| Age, median (range) | 21 (18–41) | 32 (26–50) | 38 (25–53) | 24 (18–45) | 31 (25–56) | 49 (33–65) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 21 | 7 | 8 | 24 | 9 | 10 |

| Single | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | ||||||

| Primary | 5 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| Secondary | 15 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 0 |

| College | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Diploma | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Degree | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Christian | 21 | 7 | 9 | 27 | 8 | 12 |

| Muslim | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sampling group | ||||||

| Live birth | 7 | 2 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Stillbirth | 10 | 4 | 13 | 3 | ||

| Near miss | 4 | 1 | 8 | 3 | ||

| Employment | ||||||

| None | 8 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Farmer | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Shop worker | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| Tailor | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Clerical | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Business | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Nurse/midwife | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| TBA/SMAG | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ambulance driver | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

SMAG, Safe Motherhood Action Group; TBA, Traditional Birth Attendant.

Recruitment

Women and partners (≥18 years) were recruited within facilities. The initial approach was made face-to-face by the clinical team to establish their willingness to receive study information. After receiving written and verbal information from the study team, potential participants chose whether to opt into the study. Health-providers who were practising in the same facilities that the women were attending, and key stakeholders were recruited through snowball sampling, using known contacts.

Data collection

Individual, semistructured interviews were conducted, in local language or English, by trained research assistants (DK, FK, KL, HS, KT) from the Lugina Africa Midwives Research Network (LAMRN)25 from February 2019 to September 2019. All research assistants were practising midwives; four were female and one was male. Research assistants did not have a prior relationship with the majority of participants prior to the interviews; some research assistants from Tanzania knew the health-providers interviewed. Interviewers disclosed their professional background to participants. Participants chose the interview location. Questions related to participant characteristics were incorporated into a topic guide to enable contextualisation of findings. The topic guide was informed by local Community Engagement and Involvement (CEI) groups and was purposively designed to enable participants to express their own areas of importance related to intrapartum care. Quality of care and respectful care were not a priori areas of investigation, but they did dominate the responses. The topic guide was piloted prior to use. In keeping with grounded theory,21 minimal questions were included, and participants were supported to provide narratives in their own way, without the influence of others. CEI members advised on the wording and ordering of questions at the outset, and as the questions evolved. Interviews commenced with an opening question, such as: ‘What are your thoughts about your birth?’ (for women) or ‘how do you think women experience childbirth in your facility’ (health-provider). Additionally, individualised questions were introduced to explore unique participant accounts. New insights were followed up in subsequent interviews, with different participants, for confirmability. Contemporaneous field notes captured nuances and documented non-verbal communications, such as body language, enabling understandings to be contextually grounded.

Data analysis

Strauss and Corbin’s21 Grounded Theory approach informed data analysis and involved open, axial and selective coding. Analysis was conducted by three authors (TL, RL, CTK) and confirmed by the remaining authors. Interviews conducted in local language were translated into English and independently back-translated for confirmability. Open coding involved familiarisation, by reading transcripts in their entirety. Manual line-by-line coding followed, whereby dimensions were explored by systematically, examining the whole narratives and their parts. Axial coding involved constant comparison, whereby relationships between transcripts were identified. Codes were then grouped into subcategories, according to commonalities, and constantly reorganised to gain understanding of their meaning and relationship to each other. Deviant cases were sought during analysis, but not found. The final stage, selective coding, involved identification of a core category, which related to categories identified during axial coding. In addition to the grounded-theory analysis, we interrogated the data, in relation to the WHO Quality of Care Framework,1 to provide an additional layer of understanding.

Rigour

Researchers remained reflexive throughout;26 as health professionals, they were aware of the potential impact of their role on participants, as well as the lens through which data were interpreted. Maintaining open dialogue with all members of the research team and encouraging self-reflection aided the process. To reduce the risks of coding bias, memos were made as an audit-trail of decision-making. Member-checking took place by providing participants with a verbal summary of responses at the end of each interview and seeking confirmation of the accuracy of the interpretation; this was captured on the audio-recording.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

A CEI (or PPI) group in each country was formed at study outset, prior to protocol completion. Members contributed to the study design, consent and recruitment processes, and topic guide development. The CEI/PPI Leads also contributed to interpretation of the findings and construction of the recommendations.

Results

The majority of interviews with women and partners took place in the home or local community (eg, in open communal areas). Health-providers and stakeholders were mainly interviewed at their workplace. Interviews lasted between 20 and 120 min. Table 1 presents participant characteristics. Additionally, 11 influential stakeholders were interviewed: all six stakeholders in Tanzania were male; in Zambia two were female and three were male. Stakeholders comprised religious leaders, village chiefs and policy makers.

The core category, ‘respectful care: an added extra’, was supported by three inter-related subcategories: ‘social discrimination’, ‘manipulative behaviour’ and ‘caring against the odds’ (figure 2). At the crux of these categories was the fact that quality of care and respectful care were viewed independently, and women would forgo respectful care if it meant them, and their baby would be protected. Discriminative behaviour prevented some women from receiving respectful care, which was perceived to be only for the privileged. However, women would accept disrespectful care, if it meant they received the treatment needed for a positive outcome. While some women felt manipulated into keeping quiet about mistreatment and/or offering financial incentives for care, they conformed for fear of retribution. While participants acknowledged the need for respectful care to be available for all, there was recognition that health-providers needed support to do this, while working in a challenging environment (caring against the odds). Categories were largely consistent across the two countries; differential findings have been highlighted in the results.

Figure 2.

Core category, major categories and sub-categories.

Social discrimination

Social discrimination presented as direct and indirect discrimination, and victimisation. The degree to which women received respectful care appeared heavily influenced by the presence of discriminative behaviour.

Direct discrimination

Direct discrimination was the most dominant form observed. Women were overtly judged because of certain characteristics, including their level of education, tribal affiliation and social-standing. Health-providers acknowledged the importance of treating all women the same:

We need to be welcoming, respectful and kind as health-providers, we should treat everyone the same regardless of their race, creed, tribe, or colour. (Health-provider, Zambia)

However, the narratives suggested that this was not borne out in practice. Women who had birthed larger than average numbers of babies were particularly ridiculed, and even punished, as shown below:

A nurse said ‘how can someone have all these children? How many times will I preach about family planning? Are you deaf” (touching her ears). You will be the last to be seen. Then she kept on referring to me as ‘the one with 13 pregnancies’… I was humiliated. (Pregnant woman, Zambia)

The number of children was often related to the tribe that the woman belonged to, as suggested by one woman:

They (Midwives) would ask to know your tribe and when you give your answer, their comments would be, ‘you people love giving birth’…. This is not good at all. (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

Women from rural areas were conscious of the impact their appearance had on how they were received and treated by health-providers. One TBA from Zambia suggested that ‘women who do not have maternity dresses will not go to the hospital for fear of being scolded at.’ Similarly, a stakeholder from Tanzania described how ‘nurses look at a woman’s shoes and whether she arrived at the hospital in a private car to determine how to treat her’. Such overt discrimination led to substandard levels of care provision, summed up by one partner:

A villager can go to the hospital with torn, dirty clothes and the nurses will hardly look at you. Therefore, those who dress better and apply scented ointment get priority and this discrimination is discouraging. When others have been served, they now ask questions, ‘what were you doing all day here?’…. (Partner following stillbirth, Tanzania)

Women also suggested that health-providers would actively court and provide more favourable care to women who they believed could offer them financial incentives:

I was not treated equally because other patients were given smiles, greeted, and I was not. They will befriend you if you have something to give them but not when you are a poor woman like me with dirty clothes, a bad phone as you heard it ringing. If someone comes with her husband who has money, she will get a good service…. They will get service when the nurse is happy. And they will be happy too. Take an example, you have 3 kids and you love the two, how would the other child feel?…this is how I feel when I go to the hospital. (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

Women also observed ‘favouritism’, for women who had an existing relationship with a health-provider; this resulted in some women receiving better treatment than others:

Nurses treat their friends better and give them priority because they know each other. They can be given some items that you will be asked to go get by yourself……One day I went to test and was asked to buy toilet paper but the one after me did not buy yet we did the same test. I think it is favouritism. (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

Indirect discrimination

Indirect discrimination describes a situation whereby a woman receives worse care than others because of practices or policies which are meant for everybody. One example of this related to the availability of services. Although policy dictated that all women could access the same services, women from rural areas believed that the most highly qualified health-providers were assigned to work in central facilities:

I hear the nurses at our facility are not midwives. We also need trained personnel here in the village. They take all qualified personnel to big hospitals and give us people who are not very competent to handle pregnant women, it is not fair. (Pregnant woman, Zambia)

Furthermore, women in the rural areas were less able to access specialist care due to the lack of personal finances and transport, thus limiting their choice of health facility. One partner illustrated how lack of local services resulted in a tragedy:

A mother gave birth by the roadside. Men ran away until other women tried to help…Both mother and child died by the roadside. It was sad……people went to the local Government office to complain. They then said they want to educate us. Why educate us yet the hospital was further away? It was either we get transport, or another clinic was built here. (Partner, Tanzania)

Mandatory partner attendance at the first antenatal visit was a particular concern for women in rural areas, either because they did not have a partner and did not want to request a letter from the village headman confirming this, or their partner could not afford to lose pay to attend. One health-provider described how a potentially beneficial rule might have unintended consequences:

It meant well…This was not meant to be mandatory to all pregnant women. What happens to those without partner? Like the single, divorced, or widowed… (raising shoulders) …. our role should be to encourage women to come with their partners and not force partners to escort our women. Those who cannot come with partners, lets attend to them. Let’s not make them pay a fine. What if they cannot afford to pay a fine?…. (raising hands) when they are in labour, they come with complications which were supposed to be handled during antenatal. (Health-provider, Zambia)

Women with low-literacy described their inability to obtain information about their own progress, stating that, ‘they (midwives) were writing with the language that I don’t know’ (postnatal woman following stillbirth, Tanzania). These women also felt unable to communicate effectively. Similarly, some participants believed that their lack of education meant that they were not listened to. One partner described his challenge in seeking approval to transfer his wife to a referral facility, due to prolonged labour. His wife was only transferred when a more educated relative intervened:

Our rights to be heard were not respected. She only listened to my wife’s cousin because he is educated. Is this how things are supposed to be? Us who are not educated cannot be listened to? What if we did not have that educated cousin? My wife would have ended up with a big complication and my child would be dead by now…. (Partner, Zambia)

Following a positive outcome for his wife and baby he concluded by saying ‘I must say I’m very grateful’. Women and partners from both countries frequently narrated their appreciation for the treatment that they received, even if they had indicated aspects of disrespectful care. Some women also suggested that they feared health-providers because of educational differences:

We village people are scared of the educated people. They see us as troublemakers, they also don’t respect us. So we get scared of each other. (Woman following stillbirth, Tanzania)

Victimisation

Victimisation describes someone who is treated badly, but feels unable to complain, for fear of retribution, or is unfairly treated because they have complained. We observed the former. Several women’s narratives described tolerating disrespectful care as a means of accessing services that they believed would benefit their baby without being victimised.

When they wanted to see your private parts, they would do it with the other nurses looking at you…. they would continue serving you with the curtains open. If you tell them to keep the curtains properly, they would ask you in a harsh tone, ‘are you reminding me of my duties?’ I feared that it would trigger their anger and mistreat me more. (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

A woman, from Zambia, told of how she kept quiet for fear of retribution while in labour:

…labour pains worsened…the nurse examined. When I asked about (vaginal examination) she told me to mind my business…‘your business is the labour pain. Mine is to monitor you. Even if I tell you, will you know what it means?’ I was so scared of asking anything. I delivered a female stillbirth. (Woman, Zambia)

Women also explained how they feared asking questions. One woman, from Zambia, recounted needing dry linen when her waters broke during labour as the chitenge material she had used was wet. She stated that she ‘was afraid to be shouted at if I asked’.

Health-providers interpreted women’s lack of feedback on care as meaning that they were satisfied. However, they also acknowledged the difficulty women may experience in verbalising their dissatisfaction with health-providers:

Aaah! To my opinion they have not complained openly so probably they are satisfied!……Not many women can express their dissatisfaction in front of a health worker in our setting, I see they are satisfied. (Health-provider, Zambia)

Manipulative behaviour

Health professionals used controlling or coercive behaviours to orchestrate a situation which they believed would benefit either themselves or the woman. Two subcategories describe the manipulative behaviour: ‘held to ransom’ and ‘controlling behaviour’.

Held to ransom

This subcategory, which describes how some health-providers demanded money for services which women were entitled to receive free of charge, was unique to Tanzania. Women were frequently asked for informal payments in exchange for care. Although women knew that this was wrong, they felt powerless to object:

‘You don’t pay (for services) but the nurses ask for money for a soda after giving birth. They won’t give you your child until you give them money…. You get discharged but they will scold at you that you have a bad heart…They will tell you ‘how can you come to the hospital without money?’ (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

Vulnerable women were sometimes confronted with demands during labour or emergency situations and believed their health was at risk if they failed to pay, as demonstrated by one woman who, despite having a stillbirth, was being bribed for money in exchange for a surgical evacuation:

…I saw pus coming out through the birth canal, it was the head of macerated baby…the baby was dead and starting to rot in the womb. They asked if I had money to give them so they can evacuate me. I didn’t have any money. They continued waiting for me to give them money until the other nurse came and attended me. (Postnatal woman, stillbirth, Tanzania)

Controlling behaviour

To maintain control and power in relationships, health-providers used various tactics to encourage women to comply with their wishes. Sometimes health-providers would purposefully ridicule women to stop them from complaining:

Whenever you called and spoke in monotones to keep your problem secret, they would in return reply by speaking what was said and laugh a bit about it then attend to you. Your situation will no longer be private. Everyone in the ward will know your problem…. (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

Women often felt isolated and ignored, finding it difficult to attract the attention of attending nurses when they had concerns:

Whenever I called the response was that she was attending to the other patients …. Whenever I felt that I wanted to push the baby, she wasn’t around. Sometimes I could hear she was talking on phone, sometimes chatting with fellow nurse or even with the other patients…Sometimes they just come and start shouting at you. Sometimes they just come and say, you are so stubborn, what is your problem? (Postnatal woman, Tanzania)

However, some health-providers justified using ‘harsh language’ sometimes as necessary to ‘encourage women to push’ and prevent delays minimising the risk of harm during birth to the baby. One woman narrates her observations:

When I was delivering the 14th child, the nurse beat a primigravida next to me for not having the energy to push. ‘you had the energy to make a baby, now you are claiming you have no energy to push? If you think these are jokes, you will go without a baby.’…she said. (Pregnant woman, Zambia)

Health-providers would also use avoidance tactics to prevent having a difficult conversation with a woman. This would sometimes result in the woman being lied to:

I came back from theatre…I did not see my baby…. (long pause). The nurse came to check my vitals, when I enquired about my baby, I was told my baby was in the neonatal ICU, my mother also came and I asked her where my baby was, she also told me the same….everyone was not telling me the truth. I asked a cleaner who was mopping the floor if she also cleans neonatal ICU, she said yes, so asked her if she could check if my baby is there, but unfortunately, she refused…My mother broke news to me after 2 days.… (Woman stillbirth, Zambia)

It appeared that avoiding the truth was not a deliberate attempt to deceive the woman, but was a way of protecting the health-provider who felt inadequate to provide news of a dead baby and to allow time for the family to be present, in accordance with cultural norms:

We haven’t been trained in counselling so just leave this to another person or wait until the family can break the news (Health-provider, Tanzania)

Caring against the odds

While the data clearly demonstrated disrespectful care, many narratives highlighted provision of good quality care. Participants acknowledged the difficult circumstances in which health-providers were working and the impact that this had on the care they received. ‘Staff shortages’, ‘busy labour wards’ and a ‘lack of resources’ were frequently described, by all participating groups, as contributing reasons for the poor care. Although some participants were aware of stories about health-providers mistreating women, several of them did not observe this during their own care:

I can encourage them to continue with the good works. They should have empathy for pregnant women and be mild tempered. I have never had a bad experience with the nurses but most people say nurses say bad things, they shout at patients too. (Partner, Zambia)

Most stakeholders sympathised with health-providers, who they believed were working in environments unconducive to delivering good quality care:

You find there is only one nurse at the labour ward, and 7 people who want to push at the same time. What can she do?….I request the president to work on this. More health workers are needed. (Stakeholder, Tanzania)

Some stakeholders suggested that the poor behaviour, demonstrated by some health-providers, was also a result of lack of professionalism:

We need workers who use work ethics and good working culture as they deliver their duties. Most health workers…they shout at patients and our mothers and use inappropriate language. Most of the health workers are there to earn a living. Nursing is not a calling anymore. Our women are not respected. (Stakeholder, Zambia)

Health-providers, in Tanzania, suggested that hospitals were in a transitional period, whereby Government policies and the threat of being penalised have prompted midwives to provide better care:

We have changed unlike the previous days. The nurses are motivated and the current Government does not tolerate laziness at work. So the nurses are very keen. (Health-provider, Tanzania)

Other health-providers suggested that staff shortages and heavy workloads contributed to poor communication between women and providers and urged the Government to increase the number of health-providers:

…increasing the number of workers will make us have better approaches when communicating to women…for example talking in a polite language, try as much as possible not to be rude to women even if they provoke us. (Health-provider, Zambia)

When asked about their role, no health-provider stated that they were experiencing high job satisfaction. Instead, they discussed the ‘challenges’ of their role and the frustration of not being able to ‘give women the care they deserve’. One midwife stated:

I get challenges because my clients fail to get some of the services for example, they might fail to get medicines or certain devices. Therefore, I as provider won’t feel good in providing the service. (Health-provider, Tanzania)

Women, partners and stakeholders offered words of appreciation for health-providers, acknowledging that it is ‘challenging being a nurse’.

I really appreciate the way you people -I mean the nurses and doctors help people.—On the two days of delivery period I have seen your work despite being sick I noticed that each person was struggling for my life. (Woman, near-miss mortality, Tanzania)

Discussion

Multiple perspectives on intrapartum care were explored, providing insight into experiences and views of facility-based care in settings in Tanzania and Zambia. Although participants were not asked directly about quality of care or respectful care, this dominated their narratives. Several disrespectful care domains;27 particularly communication, verbal abuse, bribery and discrimination, which resonated with the White Ribbon Alliance global survey findings, which included 1.3 million women.5 However, despite evidence of disrespectful care, women were able to separate this from any treatment that themselves or their baby required. Thus, quality of care and respectful care were not viewed as mutually inclusive; instead, respectful care was seen as an ‘added extra’ that was not universally provided. This deviates from the WHO Framework1 which displays ‘experience of care’ as one dimension of quality of care (figure 1). In our study, transactional care28 was evident throughout the narratives with healthcare-providers identifying problems and ‘providing’ care according to protocols but demonstrating little empathy towards women. For some health-providers, this exchange of care provision was dependant on informal payments requested from the woman, a factor noted by others,29 while some were motivated by receiving approval from senior colleagues and peers. Notably, women would tolerate disrespectful care if they believed it would benefit them clinically. Women appeared powerless to challenge acknowledged unacceptable behaviours by health-providers, for fear of retribution. However, what women (and partners) wanted was relational (or compassionate) care,28 including positive, empathic communications with an opportunity to ask questions, and receive respect and dignity from staff. These factors resonate with WHO recommendations2 but are less dominant on the quality Framework.1

Among the WHO Framework1 ‘competent, motivated human resources’ and availability of ‘essential physical resources’ are highlighted as important domains. We found both of these elements lacking in our study. Like others.19 30 we found that staffing and resources were believed to be insufficient; and participants explicitly linked these deficits as influencers to the delivery of disrespectful care. Specifically, data captured in the category ‘caring against the odds’ resonate with others,19 31 who suggest an association between the working environment and ability to provide relational care.

Direct and indirect social discrimination presented itself throughout the narratives, with conscious and unconscious bias appearing prevalent and impacting negatively on care. Although a level of cultural humility was demonstrated among some health-providers; the poorer and less educated women remained the most vulnerable, with discrimination identified across country settings. Two interrelated types of unconscious bias were evident, and collectively led to unacceptable behaviours: affinity (similarity),32 and conformity (peer pressure) bias.33 Affinity bias32 was evident, as health-providers tended to build relationships with those similar to themselves, for example, those from the same tribe or of similar social stature. Women were also stereotyped according to the clothes they wore and the number of children they had birthed and treated with less respect. This led to inequities in care provision and feelings of inferiority among women and their partners, mainly those from the outlying villages. Health-provider behaviours also appeared to be influenced by conformity bias,33 whereby their desire to belong resulted in peer-comradery with negative impacts, such as sharing jokes at women’s expense. Belonging is an inherent need within any working environment and a known core contributor to job satisfaction in healthcare,34 but as demonstrated in our study, can also lead to unacceptable behaviour.

Women’s apparent ability to separate medical care from emotional support meant that they were able to respect health-providers for their clinical skills and demonstrated sympathy for them being overworked and underpaid. However, reciprocal respect was not always evident. As one partner stated, ‘they will get (good) service, when the nurse is happy’, supporting the notion that health-providers who feel respected are more likely to respect others.35

Implications

These findings provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges of eradicating disrespectful health facility care in two low-income settings, with potential for transferability across other similar settings. The fact that respectful care was viewed by participants as an additional bonus to treatment is disturbing, and reflects a culture of disempowerment19 that needs to be challenged. While it is easy to blame health-providers, this is unlikely to change behaviour; indeed, this approach has failed to reduce disrespectful care over the last half a century.9 Instead, health-providers should be supported to provide optimum care, which in turn is also likely to increase job-satisfaction.

We demonstrate the need for multilayered interventions which motivate health-providers to provide the relational care women deserve. These interventions should reflect understanding that most health-providers enter the profession to provide good quality respectful care and are often prevented from doing so by external factors, such as inadequate working environments, as demonstrated in this study. There is a need to challenge entrenched views which have normalised disrespectful care,36 breakdown hierarchies that disempower healthcare providers19 and optimise facility resources (human and material). The latter is the most difficult to address, but there are several interventions with the potential to modify individual behaviours, and facility positive cultural environments. These include developing strategies for ensuring workplace diversity; providing mandatory training in self-awareness and conscious/unconscious bias, underpinned by women’s narratives; including respectful care within preservice training and assessments; introducing hospital bench-marking with non-monetary incentives (eg, mother-friendly awards); incorporating positive role models/champions to challenge disrespectful care; valuing health-providers through employer awards; promoting affirmative dialogue between health-providers and initiating open, inclusive, non-judgemental staff forums. Proposed intervention packages require testing in rigorous controlled trials.

There is a need to elevate the status of respectful care within quality-of-care frameworks, ensuring relational care is explicitly stated. Such frameworks should also acknowledge health-providers, not just as providers of care, but as individuals who have fundamental needs and adopt roles within the wider health-system context. Routine audits should evaluate respectful care, with measurement tools capable of differentiating between the nuances of transactional and relational care.

Strengths and limitations

This was a large qualitative study which accessed multiple perspectives in two countries, and across urban, rural and semirural settings. Our sample had a large proportion of women who had birthed a stillborn baby. We purposively sampled these women, being among the most vulnerable women attending the health facilities. Similarities were found with the women who birthed a live baby. While interviews were the obvious means of data collection, no attempt was made to validate the narratives, for example, through observations. Trained midwives conducted the interviews, which one could argue may influence participants’ responses. Nevertheless, we did not find any evidence of this. Given the qualitative approach used, generalisability was not sought. However, when presenting these findings to health-providers and women from other low-income settings, transferability was confirmed.

Conclusion

Although both were valued, quality of care and respectful care were not viewed as mutually inclusive. Good quality treatment (transactional care) was often juxtaposed with disrespectful care; with relational care having a lower status among women and health-providers. To readdress the balance, respectful care requires a dominant place in training programmes, policies and audits. Women’s and health-provider voices are pivotal to the development of such interventions and should reflect both sets of needs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all women, family members and health-providers participated in this study. We would also like to thank the Ministries of Health, Healthcare Managers, Community Leaders and health care institutions for supporting this study.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @DameTina1

Contributors: TL and CB conceived and designed the study with input from all authors. RL, SW and CTK coordinated the fieldwork. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation. TL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding: This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (16/137/53) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request. Qualitative data is available upon request to corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from The University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee 3 (reference 2018-4446-6653), UK; CUHAS/BMC Joint Ethical and Review Committee, Tanzania (reference CREC/287/2018), and ERES Converge IRB, Zambia (reference 2018/June 029). All participants provided written (or thumb print) informed consent.

References

- 1.Tunçalp Ӧ, Were WM, MacLennan C, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns-the who vision. BJOG 2015;122:1045–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Who recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience, 2018. Available: https://extranet.who.int/rhl/guidelines/who-recommendations-intrapartum-care-positive-childbirth-experience [Accessed 10 Dec 2020]. [PubMed]

- 3.Khosla R, Zampas C, Vogel JP, et al. International human rights and the mistreatment of women during childbirth. Health Hum Rights 2016;18:131–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downe S, Finlayson K, Oladapo OT, et al. Correction: what matters to women during childbirth: a systematic qualitative review. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197791. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White Ribbon Alliance . What women want, 2019. Available: https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/What-Women-Want_Global-Results.pdf [Accessed 30 Nov /2020].

- 6.Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, et al. Determinants of women's satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:97. 10.1186/s12884-015-0525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mocumbi S, Högberg U, Lampa E, et al. Mothers' satisfaction with care during facility-based childbirth: a cross-sectional survey in southern Mozambique. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:303. 10.1186/s12884-019-2449-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001847. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diniz SG, de Oliveira Salgado H, de Aguiar Andrezzo HF. Abuse and disrespect in childbirth care as a public health issue in Brazil. Journal of Human Growth and Development 2015;25:377–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, et al. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health 2014;11. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlayson K, Downe S. Why do women not use antenatal services in low- and middle-income countries? A Meta-Synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001373. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenberg RL, Saleem S, Ali S, et al. Maternal near miss in low-resource areas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;138:347–55. 10.1002/ijgo.12219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiegers TA. The quality of maternity care services as experienced by women in the Netherlands. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenwick J, Butt J, Dhaliwal S, et al. Western Australian women’s perceptions of the style and quality of midwifery postnatal care in hospital and at home. Women and Birth 2010;23:10–21. 10.1016/j.wombi.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bender DE, Santander A, Patiño W, et al. Perceptions of quality of reproductive care services in Bolivia: use of photo prompts and surveys as an Impetus for change. Health Care Women Int 2008;29:484–506. 10.1080/07399330801949582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stal KB, Pallangyo P, van Elteren M, et al. Women's perceptions of the quality of emergency obstetric care in a referral hospital in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:934–40. 10.1111/tmi.12496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobin C, Murphy-Lawless J, Beck CT. Childbirth in exile: asylum seeking women's experience of childbirth in Ireland. Midwifery 2014;30:831–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turan JM, Miller S, Bukusi EA, et al. Hiv/Aids and maternity care in Kenya: how fears of stigma and discrimination affect uptake and provision of labor and delivery services. AIDS Care 2008;20:938–45. 10.1080/09540120701767224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley S, McCourt C, Rayment J, et al. Midwives' perspectives on (dis)respectful intrapartum care during facility-based delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Reprod Health 2019;16:116. 10.1186/s12978-019-0773-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and technique. 2nd ed. Newbury Park: Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations Population Fund and the World Bank Group . Maternal mortality: levels and trends, 2000 to 2017, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal-mortality-2017/en/

- 23.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P. For the Lancet ending preventable stillbirths series Study Group with the Lancet stillbirth epidemiology investigator group. stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016;387:587–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The healthy newborn network. Available: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/database-global-and-national-newborn-health-data-and-indicators/ [Accessed 12 Mar 2021].

- 25.Lugina Africa midwives research network. Available: www.LAMRN.org [Accessed 30 Nov 2020].

- 26.Glaser B. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley: Sociology Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shakibazadeh E, Namadian M, Bohren MA, et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2018;125:932–42. 10.1111/1471-0528.15015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iles V, Sweeney K, Vaughan Smith J. What makes good doctors practise bad medicine? 2009. Available: http://www.reallylearning.com/Current_Projects/Learning_Sets/What_makes_good_Doctors_practise_bad_medicine2_3_09.pdf [Accessed 30 Nov 2020].

- 29.Schaaf M, Topp SM. A critical interpretive synthesis of informal payments in maternal health care. Health Policy Plan 2019;34:216–29. 10.1093/heapol/czz003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mselle LT, Kohi TW, Dol J. Humanizing birth in Tanzania: a qualitative study on the (mis) treatment of women during childbirth from the perspective of mothers and fathers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:231. 10.1186/s12884-019-2385-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hulsbergen M, van der Kwaak A. The influence of quality and respectful care on the uptake of skilled birth attendance in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:681. 10.1186/s12884-020-03278-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nalty K. Strategies for confronting unconscious bias. The Colorado Lawyer 2016;45:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasak J, Royal K. How to encourage differing opinions, not conformity, 2019. Available: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/249290/encourage-differing-opinions-not-conformity.aspx [Accessed 09 Mar 2021].

- 34.Puchalski Ritchie LM, Khan S, Moore JE, et al. Low- and middle-income countries face many common barriers to implementation of maternal health evidence products. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;76:229–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Josling M. Belongingness, work engagement, stress and job satisfaction in a healthcare setting, 2015. Available: https://esource.dbs.ie/bitstream/handle/10788/2809/ba_josling_megan_2015.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 02 Dec 2020].

- 36.Smith J, Banay R, Zimmerman E, et al. Barriers to provision of respectful maternity care in Zambia: results from a qualitative study through the lens of behavioral science. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:26. 10.1186/s12884-019-2579-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request. Qualitative data is available upon request to corresponding author.