Abstract

Background

People with dementia living in the community, that is in their own homes, are often not engaged in meaningful activities. Activities tailored to their individual interests and preferences might be one approach to improve quality of life and reduce challenging behaviour.

Objectives

To assess the effects of personally tailored activities on psychosocial outcomes for people with dementia living in the community and their caregivers.

To describe the components of the interventions.

To describe conditions which enhance the effectiveness of personally tailored activities in this setting.

Search methods

We searched ALOIS: the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialized Register on 11 September 2019 using the terms: activity OR activities OR occupation* OR “psychosocial intervention" OR "non‐pharmacological intervention" OR "personally‐tailored" OR "individually‐tailored" OR individual OR meaning OR involvement OR engagement OR occupational OR personhood OR "person‐centred" OR identity OR Montessori OR community OR ambulatory OR "home care" OR "geriatric day hospital" OR "day care" OR "behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia" OR "BPSD" OR "neuropsychiatric symptoms" OR "challenging behaviour" OR "quality of life" OR depression. ALOIS contains records of clinical trials identified from monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases, numerous trial registries and grey literature sources.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials and quasi‐experimental trials including a control group offering personally tailored activities. All interventions comprised an assessment of the participant’s present or past interests in, or preferences for, particular activities for all participants as a basis for an individual activity plan. We did not include interventions offering a single activity (e.g. music or reminiscence) or activities that were not tailored to the individual's interests or preferences. Control groups received usual care or an active control intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently checked the articles for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed the methodological quality of all included studies. We assessed the risk of selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, and detection bias. In case of missing information, we contacted the study authors.

Main results

We included five randomised controlled trials (four parallel‐group studies and one cross‐over study), in which a total of 262 participants completed the studies. The number of participants ranged from 30 to 160. The mean age of the participants ranged from 71 to 83 years, and mean Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores ranged from 11 to 24. One study enrolled predominantly male veterans; in the other studies the proportion of female participants ranged from 40% to 60%. Informal caregivers were mainly spouses.

In four studies family caregivers were trained to deliver personally tailored activities based on an individual assessment of interests and preferences of the people with dementia, and in one study such activities were offered directly to the participants. The selection of activities was performed with different methods. Two studies compared personally tailored activities with an attention control group, and three studies with usual care. Duration of follow‐up ranged from two weeks to four months.

We found low‐certainty evidence indicating that personally tailored activities may reduce challenging behaviour (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.77 to −0.10; I2 = 44%; 4 studies; 305 participants) and may slightly improve quality of life (based on the rating of family caregivers). For the secondary outcomes depression (two studies), affect (one study), passivity (one study), and engagement (two studies), we found low‐certainty evidence that personally tailored activities may have little or no effect. We found low‐certainty evidence that personally tailored activities may slightly improve caregiver distress (two studies) and may have little or no effect on caregiver burden (MD −0.62, 95% CI −3.08 to 1.83; I2 = 0%; 3 studies; 246 participants), caregivers' quality of life, and caregiver depression. None of the studies assessed adverse effects, and no information about adverse effects was reported in any study.

Authors' conclusions

Offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia living in the community may be one approach for reducing challenging behaviour and may also slightly improve the quality of life of people with dementia. Given the low certainty of the evidence, these results should be interpreted with caution. For depression and affect of people with dementia, as well as caregivers' quality of life and burden, we found no clear benefits of personally tailored activities.

Plain language summary

Personally tailored activities for people with dementia living in their own homes

Background

People with dementia living in their own homes often have too little to do. If a person with dementia has the chance to take part in activities which match his or her personal interests and preferences, this may lead to a better quality of life, reduce challenging behaviour such as restlessness or aggression, and have other positive effects.

Purpose of this review

We investigated the effects of offering people with dementia who were living in their own homes activities tailored to their personal interests.

Studies included in the review

In September 2019 we searched for trials in which people with dementia living in their own homes were offered activities based on their individual interests, or family caregivers were offered such activities (an intervention group) compared with other people with dementia living in their own homes who were not offered these activities or whose family caregivers were not trained in delivering such activities (a control group).

We found five studies including 262 people with dementia living in their own homes. The mean age of the study participants ranged from 71 to 83 years. All studies were randomised controlled trials, that is participants were assigned at random to either the intervention or control group. In one study the participants in the study groups switched after a specific time to the other group (i.e. the activity programme was offered to the participants in the control group, and the participants of the intervention group did not receive the activity programme any more). The participants had mild to moderate dementia, and the studies lasted from two weeks to four months.

In four studies, the family caregivers were trained to deliver the activities based on an individual care plan, and in one study the activities were offered directly to the participants. The activities offered in the studies did not vary a lot. In two studies, the control group received some information about dementia care via telephone or in personal meetings with an expert, and in three studies the control group received only the usual care delivered in their homes. The quality of the trials and how well they were reported varied, which affected our confidence in the results.

Key findings

Offering personally tailored activities may improve challenging behaviour and slightly improve quality of life of people with dementia living in their own homes, but may have little or no effect on depression, affect, passivity, and engagement (being involved in what is happening around them) of people with dementia. Personally tailored activities may slightly improve caregivers' distress, but may have little or no effect on caregiver burden, quality of life, and depression. No study looked for harmful effects and no study described that any harmful effects occurred.

Conclusions

We concluded that offering activity sessions to people with mild to moderate dementia living in their own homes may help to manage challenging behaviour and may slightly improve their quality of life.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Personally tailored activities compared to control for people with dementia living in the community.

| Personally tailored activities compared to control for people with dementia living in the community | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with dementia Setting: community Intervention: personally tailored activities Comparison: usual care and attention control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with personally tailored activities | |||||

| Challenging behaviour (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate more challenging behaviour), follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 4 months | ‐ | SMD 0.44 SD lower (0.77 lower to 0.1 lower) | ‐ | 305 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Proxy‐rating by family caregivers |

| Quality of life of people with dementia (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate better quality of life), follow‐up: 4 months | ‐ | One study found a slight increase of quality of life in the intervention group and a slight decrease in the control group with usual care and one study found little or no difference in quality of life compared with usual care | ‐ | 86 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | Proxy‐rating by family caregivers |

| Depression (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms), follow‐up: range 2 weeks to 4 months | ‐ | Two studies found little or no difference of personally tailored activities compared with usual care or an attention control group on depression | ‐ | 96 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Affect (assessed with 6 quality of life items, higher scores indicate greater frequency of positive emotion), follow‐up: 4 months | Mean affect was 17.5 (3.8) | MD 0.47 lower (1.37 lower to 0.43 higher) | ‐ | 160 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Caregiver depression (assessed with different scales, higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms), follow‐up: range 3 months to 4 months | ‐ | Three studies found little or no difference of personally tailored activities compared with usual care or an attention control group on caregiver's depression | ‐ | 256 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 | |

| Caregiver burden (assessed with the Zarit Burden Scale (original and Brazilian version), higher scores indicate greater burden), follow‐up: range 3 months to 4 months | ‐ | MD 0.62 lower (3.08 lower to 1.83 higher) | ‐ | 246 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Caregiver's quality of life (assessed with QOL‐AD scale (Brazilian version), higher scores indicating better quality of life), follow‐up: 4 months | Mean quality of life was 35.73 (4.08) | One study found little or no difference of personally tailored activities compared with usual care or an attention control group on caregiver's quality of life | ‐ | 30 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; QOL‐AD: Quality of Life ‐ Alzheimer's Disease; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level for risk of bias: outcome assessors not blinded to group allocation. 2Downgraded one level due to imprecision (wide confidence interval, including both a small and a large effect (SMD)). 3Downgraded one level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals). 4Downgraded one level for inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity between the effects of the different studies).

Background

Description of the condition

About six million people in Europe are affected by dementia (Prince 2013). In the community, the point prevalence is 40.19 (95% confidence interval 29.06 to 55.59) per 1000 in people aged 60+ years (Fiest 2016). The majority of people with dementia live in their own homes, either alone or with others (Alzheimer’s Disease International 2015; Hoffmann 2014a). Living in their own familiar environment may enable people with dementia to maintain their social networks and enjoy a better quality of life (Luppa 2008). People with dementia experience progressive cognitive and functional decline, limiting their ability to perform activities and to communicate. Furthermore, more than 80% of people with dementia living in the community may display at least one behaviour which is challenging for the caregivers, such as apathy, delusions, or aggressiveness (Cheng 2009; Shaji 2009), and up to 50% may experience depressive symptoms (Lyketsos 2004).

One unmet need of people with dementia living in the community is to be engaged in meaningful activities (Johnston 2011; Miranda‐Castillo 2013; van der Roest 2009). People with impaired cognitive function living in the community have fewer social interactions and participate less in activities (Holtzman 2004; Krueger 2009). This lack of participation in structured or social activities may increase the risk of challenging behaviours related to dementia (Cohen‐Mansfield 2011). However, people with dementia have expressed their wish to be involved in activities that are perceived as meaningful and meet their interests (Phinney 2007). Activities are judged as personally meaningful by people with dementia if the activities are connected with self (which represents the personal interests and the individual motivation to take part in a specific activity), with others, and with the environment (Han 2016).

People with dementia living in the community often have mild or moderate cognitive impairment, and a wider range of activities might be suitable for them compared to people with severe cognitive impairment. Engaging people with dementia in personally tailored activities may not only address their unmet needs, but may also have positive effects on challenging behaviour and quality of life (Gitlin 2018). Such benefits might also positively influence caregiver burden and well‐being.

Description of the intervention

Interventions offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia in community settings are considered to be complex. Different types of activities are offered based on different models or frameworks, and how the intervention is delivered varies (Craig 2008).

For this review, we use the same definition for the interventions of interest as used in the Cochrane Review addressing people with dementia living in long‐term care settings (Möhler 2018): interventions aimed at improving psychosocial outcomes like challenging behaviours or quality of life in people with dementia living in the community rather than interventions aimed exclusively at improving particular skills (e.g. basic activities of daily living, or cognitive function). Activities should be personally tailored, which means they should be chosen after assessing the individual preferences or interests of the participants, and could also be adapted to their cognitive and functional status. Interventions could be based on specific models or concepts, such as the principles of Montessori or the concept of person‐centred care. We expected a wide range of activities to be offered, including instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. housework, preparing a meal), arts and crafts (e.g. painting, singing), work‐related tasks (e.g. gardening), and recreational activities (e.g. games). Interventions could be delivered at the participant’s home or in community‐based services (e.g. day centres), in groups or individually. Duration and frequency of the sessions could differ, and expected providers of the interventions include various professionals or a multidisciplinary team. An informal caregiver could also provide the intervention if he or she has been trained to do it.

How the intervention might work

The involvement in personally tailored activities may increase positive emotions such as interest and feelings of engagement, and decrease challenging behaviours (Harmer 2008; Phinney 2007). Positive emotions can be a resource for the management of stress and regulate a range of negative emotions such as feelings of boredom, loneliness, non‐meaningfulness, frustration, or distress (Fredrickson 2000; Steeman 2006). Benefits might also arise because personally tailored activities could facilitate the evocation of autobiographical events, preserve the identity of people with dementia, fulfil individual occupational needs not covered due to the debilitating effects of dementia, and enhance the use of remaining abilities (Harmer 2008; Kitwood 1992).

Personally tailored activities may also reduce challenging behaviour and improve quality of life of people with dementia (Burgener 2002; de Boer 2007; Ryu 2011). Other positive effects could be improvement or maintenance of functional or cognitive abilities, and reduction of the prescription of psychotropic medication. Expected benefits for caregivers are a decrease in their burden of care, which is associated with challenging behaviours of the person with dementia (Rocca 2010), and improvement of the caregiver's psychological well‐being. Caregivers might also experience an increased sense of competence by participating in the planning or administration of personally tailored activities for the person with dementia.

Why it is important to do this review

There is an increasing need for effective non‐pharmacological interventions to improve psychosocial outcomes in people with dementia in clinical practice (Ballard 2013), and several guidelines about the management of dementia recommended non‐pharmacological interventions as the primary approach for the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPSD) (Ngo 2015; Vasse 2012). Since most people with dementia live in their own homes, information on effective interventions to increase the engagement of these people is needed. So far, no systematic review has evaluated the effects of interventions offering personally tailored activities for people with dementia in community settings. Due to the expected variation and complexity of the included interventions, we described not only their effects but also their characteristics (e.g. components, intensity, and performance). Information on the implementation fidelity was incorporated, for example exposure, quality of delivery, participants’ responsiveness and adherence (Shepperd 2009). The results of this review can provide valuable information for decision making about the implementation of available activity programmes and for developing new complex interventions aiming to improve psychosocial outcomes for people with dementia living in community settings.

Objectives

To assess the effects of personally tailored activities on psychosocial outcomes for people with dementia living in the community and their caregivers.

To describe the components of the interventions.

To describe conditions which enhance the effectiveness of personally tailored activities in this setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included individual or cluster‐randomised controlled trials, and quasi‐experimental trials including a control group (i.e. controlled clinical trials, controlled before‐after studies).

Types of participants

We included all people with dementia or cognitive impairment living in the community. This included people living in their own homes, irrespective of whether they attend daytime facilities such as day‐care centres. We excluded people living in institutional care (e.g. care homes), but there is another Cochrane Review addressing this population (Möhler 2018). There were no restrictions regarding the stage of dementia or cognitive impairment.

Types of interventions

We included all interventions aimed at improving psychosocial outcomes by offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia in the community. The aims of the interventions did not necessarily include the improvement of a particular skill. The underlying understanding of a personally tailored activity is the same as in a corresponding Cochrane Review including people living in long‐term care facilities (Möhler 2018).

All interventions had to comprise the following two elements.

Assessment of the participant's present or past preferences for particular activities or interests. We included both unstructured assessment (e.g. asking for the participant's interests) and validated tools (e.g. the Pleasant Event Schedule) (Logsdon 1997). This assessment had to be performed primarily with the person with dementia; however, in later stages of dementia, next‐of‐kin or health professionals could also be used as informants.

An activity plan tailored to the individual participant's present or past preferences, which can also be adapted to the participant's cognitive and functional status. Different types of activities were acceptable: instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. housework, preparing a meal), arts and crafts (e.g. painting, singing), work‐related tasks (e.g. gardening), and recreational activities (e.g. games). The intervention could be delivered by different professionals, such as nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, or psychologists. The intervention could be delivered either to a group or to individual participants and may be offered directly to people with dementia or to their caregivers, who should subsequently impart the intervention. The intervention could take place either in the participant’s home or in community‐based services (e.g. day‐care centres).

We excluded interventions offering :

only one specific type of activity (e.g. music or reminiscence);

specific care approaches (e.g. person‐centred care) which included the delivery of activities;

multicomponent interventions comprising drug treatment and the delivery of activities; and

interventions exclusively aimed at improving cognitive function or other particular skills (e.g. communication, basic activities of daily living).

Comparison: other types of psychosocial interventions, placebo interventions (e.g. non‐specific personal attention), usual or optimised usual care.

Types of outcome measures

All included studies should report psychosocial outcomes in people with dementia, preferably evaluated by validated and reliable assessments.

Primary outcomes

Challenging behaviour, assessed by e.g. the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI).

Quality of life, assessed by e.g. Dementia Care Mapping, EuroQol (EQ‐5D).

Secondary outcomes

People with dementia:

Mood, assessed by e.g. Dementia Mood Picture Test.

Affect (i.e. expression of emotion), assessed by e.g. Observed Emotion Rating Scale.

Level of engagement, assessed by e.g. Observational Measurement of Engagement Assessment, Index of Social Engagement.

Other dementia‐related symptoms such as sleep disturbances, hallucinations, or delusions, assessed by e.g. Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).

Use of psychotropic medication.

Adverse events of the interventions employed (e.g. injuries).

Costs.

Caregivers:

Depression or anxiety, assessed by e.g. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12).

Burden, e.g. assessed by Zarit Burden Scale.

Quality of life and health status, assessed by e.g. EQ‐5D.

Distress, assessed by e.g. Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale (NPI‐D).

Sense of competence, assessed by e.g. Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SCQ).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) ‐ the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialized Register on 11 September 2019. The search terms used were: activity OR activities OR occupation* OR “psychosocial intervention" OR "non‐pharmacological intervention" OR "personally‐tailored" OR "individually‐tailored" OR individual OR meaning OR involvement OR engagement OR occupational OR personhood OR "person‐centred" OR identity OR Montessori OR community OR ambulatory OR "home care" OR "geriatric day hospital" OR "day care" OR "behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia" OR "BPSD" OR "neuropsychiatric symptoms" OR "challenging behaviour" OR "quality of life" OR depression.

ALOIS is maintained by the Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment, and cognitive enhancement in healthy people. The studies are identified from:

monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsycINFO, and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database);

monthly searches of a number of trial registers: ISRCTN, UMIN (Japan's Trial Register), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (which covers the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, the Chinese Clinical Trials Register, the German Clinical Trials Register, the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others);

quarterly search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library);

six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources: ISI Web of Knowledge Conference Proceedings, Index to Theses, Australasian Digital Theses.

To view a list of all sources searched for ALOIS, see About ALOIS on the ALOIS website.

Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, CENTRAL, and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group. We also performed additional searches in many of the sources listed above to ensure that the search for the review was as up‐to‐date and comprehensive as possible. The search strategies used can be seen in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists and forward citations of all potentially relevant publications for additional trials and for additional data needed (e.g. interventions development, process‐related data).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AR, RM) independently assessed all titles and abstracts obtained from the search for inclusion according to the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author (GM) if necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AR or HR, and RM) independently extracted data from all the included studies using a standardised form. RM checked the results for accuracy, and in case of disagreement a third review author (GM) was consulted to reach consensus.

We extracted the following data for each study: information about a study registration or published study protocol (or both), study design, characteristics of participants, baseline data, length of follow‐up, outcome measures, study results, and adverse effects.

We extracted the following information for each intervention: theoretical basis of the intervention, information about a pilot test, method of assessing the individual preferences, types of activities offered, characteristics of the intervention's components (e.g. duration and frequency), information about the implementation fidelity.

We contacted the study authors to obtain missing information where required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We followed the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). We assessed risk of bias for each study for the following criteria: selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias, and other bias. We assessed the certainty of evidence using the criteria proposed by the GRADE Working Group (Guyatt 2011).

Two review authors (AR or HR, and RM) independently assessed the methodological quality of all included studies in order to identify any potential sources of systematic bias. In case of unclear or missing information, we contacted the corresponding author of the included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous data, we calculated the mean difference (MD), if possible. One study calculated the MD for all outcomes using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (Gitlin 2018), and we used these results in the meta‐analyses and narrative analyses comparing MDs according to the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). If it was not feasible to calculate the MD, such as in the case of substantial baseline imbalances, we presented the study results in narrative form, that is as means with standard deviations. For the outcome challenging behaviour, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD), which is the absolute mean difference divided by the standard deviation (SD), since the included studies used different rating scales.

None of the included trials reported dichotomous data of interest to this review.

We used Review Manager 5 for all analysis (Review Manager 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

We assessed unit of analysis issues for each study (e.g. whether individuals or groups of individuals were randomised). We did not include any cluster‐randomised trials.

For cross‐over trials, we checked the risk of a carry‐over effect. In the included cross‐over study (Fitzsimmons 2002), no wash‐out period was included, but no information about a carry‐over effect was reported. Since no data were available for the first treatment period, we used data from the complete study period for both conditions in our analysis; however, this may have led to a unit of analysis bias.

Dealing with missing data

We described the numbers of and reasons for missing data related to participants’ dropping out in the Characteristics of included studies table. Where information was missing, we contacted the study authors and asked for the additional information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In order to describe clinical heterogeneity, we analysed all studies in terms of participants, interventions, and outcomes. We combined data in meta‐analyses only if we considered the studies to be sufficiently clinically homogeneous. To test for statistical heterogeneity, we used the Chi² and I² statistics.

Assessment of reporting biases

To identify all available studies and minimise the risk of publication bias, we performed comprehensive searches covering several databases and other resources (e.g. study registries). Due to the small number of included studies, we did not investigate the likelihood of publication bias with a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analyses for the outcomes challenging behaviour and caregiver burden using a random‐effects model, as planned in the protocol. For the other outcomes of interest, we did not perform meta‐analyses due to the small number of studies per outcome and some methodological limitations (e.g. pronounced baseline differences between study groups). We presented the results of these studies in narrative form, that is using the MD or the raw data (if it was not feasible to calculate the MD) (see Measures of treatment effect).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the pre‐planned subgroup analysis (challenging behaviour) for studies with and without an active control group. We did not conduct subgroup analyses for different stages of dementia due to the small number of included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct the pre‐planned sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias due to the methodological limitations of all studies.

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE method to assess the certainty of evidence for the most important outcomes by judging study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (Guyatt 2011). We rated certainty of evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low (Guyatt 2011). We prepared a ’Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro GDT for the following outcomes: challenging behaviour, quality of life, depression, affect, caregiver burden, caregiver quality of life, and caregiver depression (GRADEpro GDT).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

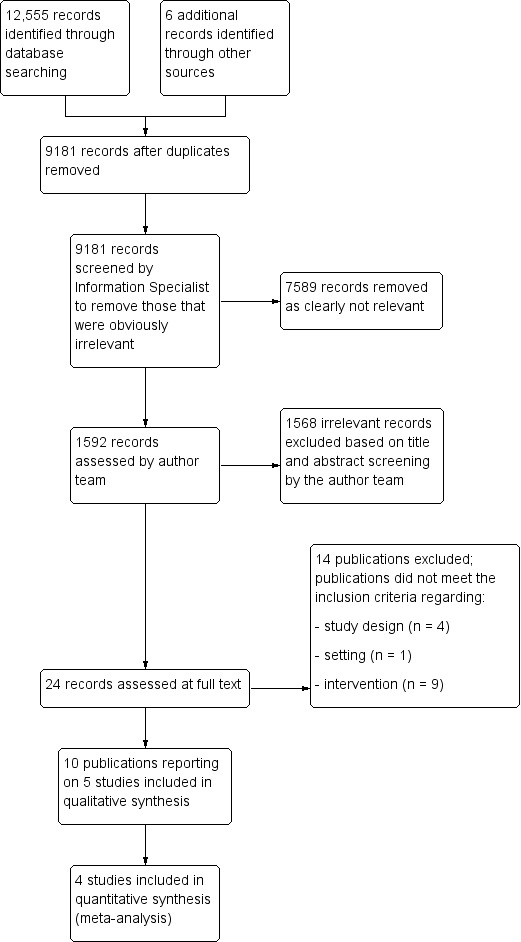

The search retrieved a total of 12,555 citations (Figure 1). After a first assessment by the Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of 1592 records for potential eligibility. We screened 24 full‐text publications, and 10 publications reporting on five studies met the inclusion criteria (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Lu 2016; Novelli 2018). We also identified three ongoing studies (Gitlin 2016; O'Connor 2014; Pimouguet 2019).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

All of the included studies were randomised controlled trials: Gitlin 2008, Gitlin 2018, Lu 2016, and Novelli 2018 used a parallel‐group design, and Fitzsimmons 2002 used a cross‐over design. Follow‐up periods ranged from two weeks, Fitzsimmons 2002, to four months (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018; the study by Gitlin 2018 had an eight‐month follow‐up, but the primary outcome was assessed after four months).

Setting and participants

Four studies were conducted in the USA, and one in Brazil (Novelli 2018). The participants were people with dementia living in their own homes. The number of participants in the studies ranged from 30, Fitzsimmons 2002, to 160, Gitlin 2018. A total of 323 participants were randomised, and 262 participants completed the studies. The mean age of participants was approximately 80 years in four studies (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018), and 71 years in the study by Lu 2016. The proportion of female participants ranged from 3% in the study by Gitlin 2018 (this study recruited veterans) to 65.5% in the study by Fitzsimmons 2002.

The cognitive status of study participants varied. In one study, participants had a mean Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of 19.0 (intervention group) and 23.82 (control group) (Novelli 2018). In the study by Gitlin 2018 the mean MMSE score was 16.8, and in the studies by Fitzsimmons 2002 and Gitlin 2008, the mean MMSE scores were 11.6 and 12.93, respectively. In the study by Lu 2016, 40% of the participants were in an early stage of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 60% in a late MCI stage. Three studies reported information on the ability to perform activities of daily living (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018), and the level of dependency was low to moderate.

In all studies the majority of caregivers were spouses, but the rates varied from about 53%, Novelli 2018, to 90%, Fitzsimmons 2002. Caregiver mean age ranged from 65.4 years, Gitlin 2008, to 74.6 years, Fitzsimmons 2002. The proportion of female caregivers ranged from 55%, Fitzsimmons 2002, to 97.5%, Gitlin 2018. For further information about the included studies, see Characteristics of included studies.

Description of the interventions

We described the included interventions using categories relevant for complex interventions (Hoffmann 2014b; Möhler 2015).

Theoretical basis of the intervention

The studies used different theoretical models guiding the selection of activities for the study participants.

Three studies investigated different versions of the Tailored Activity Program (TAP). The original version, Gitlin 2008, was adapted for use in veterans, Gitlin 2018, and for a Brazilian population, Novelli 2018. The different versions of TAP are based on the reduced stress‐threshold model (Hall 1987), which postulates that people with dementia become increasingly vulnerable to their environment and experience lower thresholds for tolerating stimuli with the progression of the disease. The interventions addressed this vulnerability by selecting activities matched to the performance capabilities of the participants and by decreasing environmental demands. An Australian version of the TAP is currently under investigation (O'Connor 2014).

Fitzsimmons 2002 based their therapeutic individualised recreation intervention (TRI) on the Need‐Driven Dementia‐Compromised Behavior (NDB) model (Algase 1996). This model defines behavioural symptoms as an indicator of unmet needs in people with dementia. Two aspects are described as potential reasons for behavioural symptoms: background factors (neuropathology, cognitive deficits, physical function, and premorbid personality) and proximal factors (qualities of the physical and social environment, and physiological and psychological need states). The intervention aimed to meet the needs of the people with dementia and reduce challenging behaviour by offering involvement in meaningful activities based on functional level, past interests, and current skills.

The Daily Engagement of Meaningful Activities (DEMA) intervention, Lu 2016, is based on a gerontological theory (Lawton 1990), the model of human occupation (Kielhofner 2002), components of the problem‐solving therapy, and the experiences of people with MCI and their caregivers (Lu 2013). The focus of the DEMA framework is to improve awareness of functional abilities, increase autonomy, and the ability to reach achievable goals (Lu 2016).

Feasibility/pilot test

Gitlin 2008 was designed as a pilot study for the TAP intervention, and Novelli 2018 was designed as a pilot study for the Tailored Activity Program in Brazil (TAP‐BR) intervention. Gitlin 2018 based their study hypothesis on the study by Gitlin 2008. The intervention evaluated by Lu 2016 is based on a feasibility study and a single‐group pilot study (Lu 2011; Lu 2013). No information about a feasibility test or pilot study was reported by Fitzsimmons 2002.

Components of the intervention

Assessment of interests/preferences and selection of activities

In all versions of TAP (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018), occupational therapists assessed the preferences/interests and capabilities of the participants (e.g. executive and physical functioning, fall risk, daily routines) and caregivers (routines, employment, readiness) as well as environmental factors (e.g. lighting, seating, clutter, noise) in a semi‐structured interview. Different instruments were used (e.g. the Pleasant Event Schedule (Logsdon 1997), the Dementia Rating Scale (Jurica 2001), and Allen’s observational craft‐based assessments (Allen 1993; Blue 1993; Earhart 2003)). The types of activities offered included: multistep activities (e.g. making salad or simple woodworking), one‐to‐two‐step activities (e.g. sorting beads, bean toss game), and sensory‐oriented activities (e.g. viewing videos or listening to music).

Fitzsimmons 2002 used the Global Deterioration Scale (Reisberg 1982, to assess the functioning level) and the Farrington Leisure Assessment (Buettner 1995, for leisure interests) to tailor the activities to the study participants. No information was available about who completed this assessment. The principal investigator prescribed the therapeutic activities for each participant (tailored to functional level, interests, and needs). Seventy‐three different activities could be offered, included therapeutic cooking, art/craft therapy, animal assisted therapy, wheelchair biking, relaxation or exercise, cognitive games, flower arranging, home decorating, massage, nurturing dolls, painting, memory tea, etc.

For Daily Engagement of Meaningful Activities (DEMA) (Lu 2016), information about the participants and their caregivers was assessed, such as level of awareness of functional abilities, types and frequencies of meaningful activities and perceived barriers to engaging in these activities. No examples of the activities offered were provided in this study.

Components and delivery of the intervention

Caregivers were trained to deliver the selected activities to the participants with dementia in four studies (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Lu 2016; Novelli 2018). In the study by Fitzsimmons 2002, the personally tailored activities were offered directly to the participants. Training or activities were delivered by trained recreational or occupational therapists in all studies, but no information about the formal level of education or experience was provided in any study.

The TAP intervention comprised six 90‐minute home visits and two 15‐minute telephone contacts (Gitlin 2008). Tailored Activity Program – Veterans Administration (TAP‐VA), Gitlin 2013; Gitlin 2018, and TAP‐BR, Novelli 2018, comprised eight sessions (duration not reported) and no telephone contacts, but the first two sessions were used for the assessment of preferences and interests. In both interventions, trained occupational therapists developed an activity plan for each participant (including several activities and corresponding goals) and provided knowledge and skills (e.g. communication and task simplification skills) to the caregivers for delivering the activities to the participants with dementia. Caregivers were also trained to simplify activities for further decline and other strategies to care challenges.

In the study by Fitzsimmons 2002, a trained recreation therapist offered three to four activity sessions per week (each one to two hours) to the study participants for two weeks.

The DEMA intervention was delivered in six sessions (every two weeks), two face‐to‐face sessions in a private room in a clinic and four telephone contacts, over three months by a trained nurse (Lu 2016). In the first session, the assessment of interests and preferences was performed, and in the next five sessions the following topics were addressed: identification of activities and daily activity goals, discussions of potential barriers, needs prioritisation, re‐evaluation of decisions about priority activities, self‐evaluation of success and failure, as well as discussion about MCI (symptoms, treatment, understanding and managing negative emotional responses, strategies for living with MCI, available local and national resources).

Characteristics of the control conditions

The control groups in three studies did not receive a specific intervention (usual care) (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Novelli 2018); in the studies by Gitlin 2008 and Novelli 2018 the control group received the intervention after the follow‐up period (waiting‐group design). No further information about the characteristics of usual care was provided (e.g. the amount and type of activities offered as part of usual care).

Two studies used an active control group. Gitlin 2018 used an attention control aimed at controlling for the one‐on‐one attention to caregivers in the intervention group to rule out potential effects of professional contact and keeping the caregivers connected to the trial. Caregivers received eight telephone sessions with a team member (master‐level) experienced in educating caregivers. Information about dementia and strategies for managing the disease at home were provided, but no information or discussion of activities or behavioural symptoms (Gitlin 2013; Gitlin 2018). Lu 2016 also offered an attention control group, including two face‐to‐face meetings providing an overview of study content and an Alzheimer’s Association MCI educational brochure, followed by four bi‐weekly social conversation phone calls and the opportunity to ask questions related to the educational brochure.

Implementation fidelity

Three studies assessed implementation fidelity (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Lu 2016).

In the study by Gitlin 2008 the intervention was almost implemented as intended. The mean time of the therapist's home visit was one hour, and 15 minutes for the telephone contacts. Most of the six home visits involved both, the participant and the caregiver (mean 5.13 ± 1.36), and an average of 2.4 ± 1.1 activities were introduced.

Gitlin 2018 assessed implementation fidelity for 10% of randomly selected case presentations at supervisory meetings in both groups. Completed intervention documentation was also reviewed to assess adherence to the protocol. From the eight pre‐planned sessions, an average of 7.02 ± 1.72 sessions were completed with a duration of 75.5 ± 26.6 minutes per session (range 15 to 180 minutes). In the intervention group, 58.5% of the caregivers completed all eight sessions, 24.6% seven sessions, 0.7% six sessions, 3.1% five sessions, 7.7% four sessions, and 4.6% three or fewer sessions. In the active control group, the mean time per telephone contact was 18.2 ± 7.0 minutes (range 8 to 57), and the caregivers completed an average of 7.05 ± 1.98 sessions; 92.9% of the caregivers completed four or more sessions.

Lu 2016 used several procedures to enhance, maintain, and assess implementation fidelity: a standardised training of the staff implementing the intervention (including methods to tailor the intervention), recording of the intervention and evaluation sessions, and an assessment of the dose received by the participants (dyads were asked "about the perceived benefits and barriers or challenges to meeting planned weekly activity goals and adherence to the self‐management tool kit, time and frequency of engagement in planned activities, and use of resources provided"). Treatment fidelity for both the intervention and the active control were "evaluated within 10 days after each session using a quality assurance checklist while listening to the audio tapes" (Lu 2016).

Outcomes and methods of data collection

Primary outcomes

Four studies assessed challenging behaviour (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018).

Fitzsimmons 2002 used the Cohen‐Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI, Cohen‐Mansfield 1989), a proxy‐rating instrument comprising four subscales (physically non‐aggressive behaviours, physically aggressive behaviours, verbally non‐aggressive behaviours, and verbally aggressive behaviours; range 0 to 29). The assessment was performed by the caregivers. Higher scores indicate higher frequencies of challenging behaviour.

Gitlin 2008 assessed the mean frequency of 24 behaviours and the number of different behaviours (all 16 behaviours from the Agitated Behaviours in Dementia Scale (Logsdon 1999), two behaviours (repetitive questioning, hiding or hoarding) from the Revised Memory and Behaviour Problem Checklist (Teri 1992), four behaviours (wandering, incontinent incidents, shadowing, boredom) from previous research showing these behaviours as common and distressful, and two ("others") identified by families that could not be coded elsewhere). For each behaviour, the family caregivers rated the occurrence (yes or no) and frequency in the past month. Higher scores indicate a higher frequency of occurrence.

Gitlin 2018 assessed challenging behaviour using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory‐Clinician (NPI‐C) (de Medeiros 2010): the presence of behaviours from 14 domains in the past month was assessed, and a score for the total number of behaviours (range 0 to 14) was calculated. For each behaviour, caregivers reported frequency (0 = never to 4 = very frequently (≥ 1/d)), and severity (0 = none to 3 = major source of behavioural abnormality). A total score was calculated by multiplying frequency by severity scores for each item and then summing across 142 items from 14 domains (alpha 0.82, range 0 to 1704); higher scores indicate greater frequency and severity. Gitlin 2018 performed data imputation for missing data using predicted values from a regression model of significant baseline characteristics. For NPI‐C total scores at four months, predictors included activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) dependence, caregiver number of medicines, and baseline frequency by severity behaviour score. For the number of behavioural symptoms at four months, ADL dependence, caregiver strategy use score, and baseline number of behavioural symptoms were used.

Novelli 2018 used the Brazilian version of the NPI (Camozzato 2008). The NPI assesses 12 neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, dysphoria, anxiety, agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability/lability, apathy, aberrant motor activity, nighttime behaviour disturbances, appetite and eating abnormalities) and consists of three subscales for each symptom (frequency (4‐point scale), intensity (3‐point scale), and caregiver distress (5‐point scale)). The total NPI score (frequency multiplied by intensity) was calculated as the sum of the scores for each symptom. High scores indicate greater frequency and severity.

Quality of life of people with dementia was measured in the studies by Gitlin 2008 and Novelli 2018. Gitlin 2008 used the Quality of Life in Alzheimer's Disease (QOL‐AD) scale (Logsdon 2002), with 12 items rated on a 4‐point scale (1 = poor, 4 = excellent) to assess caregivers' perception of participants' life quality. In the study by Novelli 2018, both the participants (self‐rating) and the caregivers (proxy‐rating) rated quality of life using the Brazilian version of the QOL‐AD scale with 13 items, each rated on a 4‐point scale (1 = poor, 4 = excellent; total score ranges from 13 to 52), with higher scores indicating better quality of life (Novelli 2010).

Secondary outcomes

People with dementia

Two studies assessed depression (Gitlin 2008; Lu 2016). Gitlin 2008 used the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (Alexopoulos 1988); the family caregivers and the people with dementia completed the scale independently, and a combined score was created as the sum of both ratings. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. Lu 2016 used a self‐rating of the people with MCI using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) (Kroenke 2001), where higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.

Affect was assessed in the study by Gitlin 2018. The family caregivers assessed affect using six quality of life items (rated on a 5‐point scale: 1 = never, 5 = several times per day); a sum‐score was calculated across all items (range 6 to 30), with higher scores indicating greater frequency of positive emotion.

Passivity was assessed by Fitzsimmons 2002. The family caregivers used the Passivity in Dementia Scale (PDS, Colling 2000), a proxy‐rating instrument with 53 items (range 16 to 40, a higher score indicates less passivity).

Two studies assessed engagement in activities. Gitlin 2008 used a self‐developed proxy‐rated index (completed by the family caregivers) to assess engagement; the scores represented mean ratings across five items, with higher scores indicating greater engagement. Lu 2016 assessed meaningful activity performance and satisfaction with two subscales from the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Kielhofner 2002), including two items with a 10‐point response scale (higher scores indicate greater meaningful daily activities performance and satisfaction).

Caregiver

Three studies assessed caregiver burden (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018). Gitlin 2008 and Gitlin 2018 used the Zarit Burden Scale (Bédard 2001; range 0 to 48, higher scores indicate greater burden), and Novelli 2018 used the Brazil version of the Zarit Burden Scale (Taub 2004; 22 items rated on a 4‐point scale (0 = never, 4 = nearly always; range 0 to 88). In both instruments higher scores indicate greater burden.

In the studies by Gitlin 2008 and Gitlin 2018, the family caregivers also assessed the level of care as the number of hours providing ADL and IADL assistance, hours on duty, and hours doing things for the person with dementia per day.

Caregiver depression was assessed in the studies by Gitlin 2008 and Gitlin 2018 with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES‐D) scale (higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms) (Radloff 1977), and in the study by Lu 2016 with the PHQ‐9 (self‐rated, higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms).

Gitlin 2018 and Novelli 2018 assessed caregiver distress. Gitlin 2018 used the NPI‐C rating for each behaviour with a 6‐point scale (0 = not distressing, 5 = extremely distressing) (de Medeiros 2010); the distress score was calculated as the mean of subscale averages for 14 behavioural domains. Novelli 2018 used the Brazilian version of the NPI, rating the distress for each behaviour on a 5‐point scale (0 = no distress, 5 = extreme distress); higher scores indicate more distress (Camozzato 2008).

In the study by Novelli 2018, caregivers rated their own quality of life using the Brazilian version of the QOL‐AD scale (Novelli 2010), with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Gitlin 2008 assessed skill mastery (5‐item scale, 1 = never, 5 = always; Lawton 1989) and the confidence using activities during the past month (self‐developed scale, higher rates indicate greater confidence).

Excluded studies

We excluded studies mainly because the intervention or the study design did not meet our inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

We contacted the first authors of all studies to ask for additional information on study characteristics that were not completely reported. All authors responded to our request.

The methodological quality of included studies varied, but we judged all studies to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

The randomisation sequence was adequately generated in all studies (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Lu 2016; Novelli 2018).

Allocation was adequately concealed in four studies (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Lu 2016; Novelli 2018), and unclear in one study (Fitzsimmons 2002).

Blinding

Personnel delivering the intervention were blinded to group allocation in only one study (Lu 2016); this study offered an active control intervention and blinding was possible. In four studies (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018), blinding was not possible due to the nature of the intervention (control intervention was usual care, or delivery of the active control differed from the intervention, like telephone‐based support). The three studies that investigated the TAP intervention offered training to the therapists to ensure that delivery of the intervention adhered to the protocol (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018). In four studies there was insufficient information to judge risk of bias as high or low.

Caregivers rated most of the study outcomes (challenging behaviour, quality of life, depression, affect, passivity) and were not blinded to group allocation in any of the studies. We judged the risk of bias to be high for these outcomes. In two studies (Lu 2016; Novelli 2018), the participants self‐rated some outcomes, such as qualify of life, Novelli 2018, and depressive symptoms, Lu 2016, and were not blinded to group allocation. We also judged the risk of bias to be high for these outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies reported information about incomplete outcome data. In four studies, the number of participants lost to follow‐up was low, or none of the participants were lost to follow‐up, and the attrition rates between groups were similar (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Lu 2016; Novelli 2018). We rated the attrition bias as unclear in one study because attrition rates were high in both groups (between 30% and 33% respectively), and there were differences in the baseline characteristics between completing and non‐completing participants (Gitlin 2018).

Selective reporting

Only one study was prospectively registered and reported all pre‐planned outcomes (Gitlin 2018). Gitlin 2008 reported all outcomes that were described in the study register, but the study was retrospectively registered. Three studies were not registered and no study protocol was available (Fitzsimmons 2002; Lu 2016; Novelli 2018).

Other potential sources of bias

We rated the risk of other bias as unclear in one study (Novelli 2018), due to pronounced baseline differences between the study groups for several outcomes. These differences might have occurred due to selection bias or by chance because of the small sample size.

We rated the risk of other bias as high in the study by Fitzsimmons 2002 because of the cross‐over design, with a risk of unit of analysis bias since no paired data were available. There was also no wash‐out period, but it remains unclear whether this led to bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Challenging behaviour

We performed a meta‐analysis for challenging behaviour including four studies. We calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) since the studies used different instruments to assess challenging behaviour. Three studies compared personally tailored activities with usual care (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Novelli 2018), and one study with an attention control group (Gitlin 2018).

We found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities may reduce challenging behaviour compared with usual care or an attention control group (SMD −0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.77 to −0.10; I² = 44%; 4 studies; 305 participants; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). The subgroup analysis including only studies with a usual care control group showed that personally tailored activities may reduce challenging behaviour (SMD −0.55, 95% CI −1.08 to −0.03; I² = 57%; 3 studies; 145 participants). Compared with an attention control group, personally tailored activities may slightly reduce challenging behaviour (SMD −0.29, 95% CI −0.61 to 0.02; 1 study; 160 participants). There was no statistically significant difference between the results of the subgroups offering an attention control or a usual care control group (test for subgroup differences P = 0.41, I² = 0%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Challenging behaviour, Outcome 1: Personally tailored activities vs control

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Challenging behaviour, outcome: 1.1 Personally tailored activities versus control.

Quality of life

Two studies investigated the effects of personally tailored activities on quality of life (Gitlin 2008; Novelli 2018). In the study by Novelli 2018, quality of life was rated by the participants themselves and also proxy‐rated by the family caregivers. We did not perform a meta‐analysis due to pronounced baseline differences in one study (Novelli 2018).

In the study by Novelli 2018, the self‐rated quality of life of the participants was nearly unchanged in the intervention group (baseline 38.47 ± 2.53, follow‐up 38.8 ± 4.44; 15 participants) and slightly decreased in the usual care control group (baseline 34.87 ± 6.07, follow‐up 32.47 ± 7.56; 15 participants).

For quality of life rated by the family caregivers, Novelli 2018 found a slight increase in the intervention group (baseline 32.20 ± 5.37, follow‐up 35.00 ± 4.54; 15 participants) and a slight decrease in the usual care control group (baseline 29.80 ± 5.68, follow‐up 28.40 ± 5.97; 15 participants). Gitlin 2008 found little or no effect on quality of life compared with usual care (intervention group: baseline 2.2 ± 0.3, follow‐up 2.4 ± 0.4; control group: baseline 2.0 ± 0.4, follow‐up 2.1 ± 0.5; 56 participants).

There is low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) indicating that personally tailored activities may slightly improve quality of life (rated by family caregivers) and low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) of little or no effect of personally tailored interventions on quality of life (rated by participants) compared with usual care.

Secondary outcomes

With the exception of caregiver burden, we did not perform meta‐analyses for the secondary outcomes because of the small number of studies and baseline differences between groups in some of the studies.

Outcomes of the people with dementia

No studies investigated mood of people with dementia, but two studies assessed depression. We found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect on depression compared with an attention control group (mean difference (MD) −0.23, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.08; 40 participants; Analysis 2.1; Lu 2016) and usual care (intervention group: baseline 9.2 ± 5.1, follow‐up 9.0 ± 4.6; control group: baseline 8.1 ± 4.5, follow‐up 8.7 ± 4.7; 56 participants; Gitlin 2008).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Depression, Outcome 1: Personally tailored activities vs control

For affect, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect compared with the attention control group (MD −0.47, 95% CI −1.37 to 0.43; 160 participants) (Gitlin 2018).

For passivity, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect compared with usual care (MD 0.78, 95% CI −2.44 to 4.00; 59 participants; Analysis 3.1; Fitzsimmons 2002).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Passitity, Outcome 1: Personally tailored activities vs control

For engagement in activities, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and inconsistency) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect compared with usual care (MD 0.30, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.48; 56 participants; Analysis 4.1; Gitlin 2008) or an attention control group (Lu 2016 found a slight decrease in meaningful activity performance in the intervention group (baseline 8.46 ± 0.27, follow‐up 8.04 ± 0.27; 20 participants) and an increase in the control group (baseline 7.43 ± 0.47, follow‐up 8.49 ± 0.24; 20 participants)).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Engagement, Outcome 1: Personally tailored activities vs usual care

Adverse effects were not assessed in the included studies, and no information about adverse effects was reported. Other dementia‐related symptoms, the use of psychotropic medications and costs were also not assessed in any included study.

Caregiver outcomes

For caregiver depression, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and inconsistency) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect compared with an attention control group (MD −0.59, 95% CI −1.74 to 0.56; 160 participants; Gitlin 2018; and MD 0.04, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.20; 40 participants; Lu 2016) and compared with usual care (in the study by Gitlin 2008, caregiver depression decreased slightly in the intervention group (baseline 14.6 ± 11.0, follow‐up 13.1 ± 9.4; 27 participants) and increased slightly in the control group (baseline 13.2 ± 9.6, follow‐up 14.3 ± 10.2; 29 participants)).

We also found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect on caregiver burden (MD −0.62, 95% CI −3.08 to 1.83; I² = 0%; 3 studies; 246 participants; Analysis 5.1; Figure 5). There is no statistically significant difference between the results of the subgroups offering an attention control or a usual care control (test for subgroup differences P = 0.77, I² = 0%).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Caregiver burden, Outcome 1: Personally tailored activities vs control

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Caregiver burden, outcome: 4.1 Personally tailored activities versus control.

For caregivers' quality of life, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) that personally tailored activities have little or no effect compared with usual care (in the study by Novelli 2018, caregivers' quality of life increased slightly in the intervention group (baseline 38.67 ± 5.64, follow‐up 41.47 ± 4.07) and was nearly unchanged in the usual care control group (baseline 36.53 ± 3.64, follow‐up 35.73 ± 4.08).

For caregiver distress, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and inconsistency) that personally tailored activities may slightly reduce caregiver distress. In the study by Gitlin 2018, personally tailored activities had little or no effect on caregiver distress compared with the attention control group (MD −0.07, 95% CI −0.14 to −0.01; 160 participants). In the study by Novelli 2018, caregiver distress was reduced in the intervention group (baseline 13.63 ± 9.65 and follow‐up 6.87 ± 5.15; 15 participants) and nearly unchanged in the usual care control group (baseline 20.20 ± 15.22, follow‐up 20.20 ± 13.77; 15 participants).

Sense of competence was not assessed in the included studies, but one study assessed the caregivers' confidence in using activities and skill mastery (Gitlin 2008). For confidence in using activities, we found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) from one study that personally tailored activities may slightly improve confidence in using activities compared with usual care (MD 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 2.94; 56 participants; Gitlin 2008). We also found low‐certainty evidence (downgraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision) from one study that personally tailored activities have little or no effect on skill mastery (MD 0.0, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.31; 56 participants; Analysis 6.1; Gitlin 2008).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Skill mastery, Outcome 1: Personally tailored activities vs usual care

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included five trials in this systematic review evaluating the effects of personally tailored activities, that is activities tailored to the individual participant's present or past preferences, for people with dementia living in the community. In all studies therapists assessed the personal interests and functional and cognitive abilities of the participants and created an activity plan. In four studies, therapists trained informal caregivers to deliver activities based on the individualised plan, and in one study the therapists offered the activities directly to the study participants. Three studies tested a version of the same intervention adapted to different populations (Gitlin 2008; Gitlin 2018; Novelli 2018). The methods for assessing the personal interests of the participants and creating the activity plans varied, but the selected activities seem to be comparable across four studies (one study, Lu 2016, did not provide examples of the activities offered). The intervention was tested against usual care in three studies (Fitzsimmons 2002; Gitlin 2008; Novelli 2018), and against an attention control group in two studies (Gitlin 2018; Lu 2016).

Offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia in the community may reduce challenging behaviour and may slightly improve quality of life, but may have little or no effect on depression, affect, passivity, and engagement of people with dementia. For the caregiver‐related outcomes, personally tailored activities may slightly improve caregiver distress and confidence in using activities, but may have little or no effect on caregiver burden, quality of life, and depression. None of the included studies assessed adverse effects. There were no clear differences in the effects of personally tailored activities in comparison to either usual care or an attention control group. The Cochrane Review on personally tailored activities for people with dementia in long‐term care found a trend towards a greater effect of personally tailored activities compared with usual care, and smaller or even no effects of personally tailored activities compared with active control groups (Möhler 2018). Given the small number of included studies for each outcome comparing the intervention with either active control group or usual care, as well as the methodological limitations of some of the studies (e.g. small sample size and lack of blinding), these results should be interpreted with caution.

One reason for the heterogeneity of results across studies might be variation in the level of cognitive impairment of the study participants. The mean MMSE score of participants in one study was 19 and 24 in the intervention and control group, respectively (Novelli 2018), and four studies included participants with mean MMSE scores ranging from 11 to approximately 16. The degree of ADL dependency (assessed in three studies) was low to moderate. People in the early stages of dementia might be able to perform personally tailored activities on their own choice or ask for the assistance of family members, and this can lead to smaller intervention effects. However, based on the small number of studies, a sensitivity analysis for different levels of cognitive impairment was not feasible.

Personally tailored activities represent a combination of different activities rather than a single type of activity. The effects of the interventions are influenced by the selection of the activities and whether they are suitable and perceived as meaningful by an individual participant. However, investigating the effects of personally tailored activities for people with dementia presents several methodological challenges. The theoretical basis of the included interventions differed. The TAP interventions were based on the reduced stress‐threshold model (Hall 1987), which postulates that people with dementia become increasingly vulnerable to their environment and experience lower thresholds for tolerating stimuli with the progression of the disease. Fitzsimmons 2002 used the Need‐Driven Dementia‐Compromised Behavior (NDB) model (Algase 1996), which defines challenging behaviour as an indicator of unmet needs, and the study by Lu 2016 based the intervention on three broader theories. The methods to assess the participants' present or past interests in or preferences for particular activities also differed between the studies as well as the methods used for choosing the activities for the individualised activity plans; however, the activities offered in the different studies seem to be comparable. However, it remains unclear whether the selection of the activities really met the personal interests of the study participants.

All included studies showed methodological limitations to some extent. Most study outcomes were subjective and assessed by caregivers not blinded to group allocation; four out of five trials recruited small samples; and one study showed some pronounced differences between groups. We therefore have little confidence in the results of this review.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The study participants had mild to moderate dementia, and their caregivers were mainly spouses. This seems to be comparable with the general population of people with dementia in the community (Thyrian 2016). One study recruited (predominantly male) participants (Gitlin 2018), although the majority of people with dementia are females, and one study was conducted in Brazil (Novelli 2018). The numbers of studies contributing to the different outcomes of interest in this review were small. One ongoing study was recently completed, but no study results are currently available.

The included studies used different instruments to assess challenging behaviour, and these instruments varied with regard to the behaviours included (van der Linde 2014). However, the instruments used showed a good reliability (van der Linde 2014).

Quality of the evidence

We judged the certainty of evidence to be predominantly low using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2011). The number of participants was small in four studies, and three studies were designed as pilot studies and were not sufficiently powered. There was a high risk of detection bias for the subjective outcomes in all studies since blinding of the people with dementia and their caregivers was not possible. The results of the included studies were heterogenous with wide confidence intervals or inconsistent results between studies. Quality of life of people with dementia was assessed by the family caregivers. There is evidence that proxy‐rating of quality of life is less valid than self‐rating, since there might be a stronger influence of personal factors of the proxy‐raters, such as personal attitudes (Arons 2013; Gomez‐Gallego 2015; Moyle 2012). However, Novelli 2018 assessed quality of life of people with dementia both with self‐rating and proxy rating by family caregivers, and there were no strong differences between the different ratings.

We have no information on the characteristics of usual care in the included studies, and the amount of activities available to the participants in the control group may have varied substantially between studies.

Potential biases in the review process

We have made several efforts in the review process to reduce the risk of bias. We conducted an intensive literature search, covering database search (including electronic databases and trial registers, guided by the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group) as well as snowballing techniques for all included studies. However, due to the small number of studies, we were not able to investigate the risk for publication bias using a funnel plot or formal statistical methods. Two review authors independently conducted study selection, quality appraisal, and data extraction, and we contacted study authors for missing information.

We included a cross‐over trial (Fitzsimmons 2002), and we used the data of the complete study period despite the lack of a wash‐out period, because no data for the first treatment period were available. We judged the risk of other bias as high for this study, but we do not expect that this introduced bias in our review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two systematic reviews included studies offering personally tailored activities (Bennett 2019; Schneider 2019). Bennett 2019 investigated the effects of occupational therapy for people with dementia in the community, and Schneider 2019 investigated non‐pharmacological intervention to reduce behavioural psychological symptoms of dementia in community‐dwelling people with dementia. In line with our review, both reviews found positive effects of occupational therapy on challenging behaviour. Although in most studies included in our review occupational therapists delivered the intervention or caregiver education, occupational therapy in general might differ from personally tailored activities in terms of the degree of person‐centredness and the focus of the activities.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Offering personally tailored activities to people with dementia living in the community may reduce challenging behaviour and may slightly improve quality of life, but does not seem beneficial in improving depression, affect, passivity, and engagement of people with dementia or most caregiver‐related outcomes (e.g. burden, quality of life, or depression). No adverse effects were reported. From an ethical perspective, engagement in meaningful activities of people with dementia in the community is important, and caregivers are an important resource to support this. However, based on the current evidence, structured approaches offering training to caregivers seem to be less beneficial than expected.

Implications for research.

Our certainty in the results of this review is limited. We included several pilot studies or studies with small sample sizes. There is a need for more sufficiently powered randomised controlled trials that are planned and conducted according to current methodological standards (e.g. randomised and concealed allocation, and adequate blinding of participants and family caregivers (which can be made possible by offering an active control group) and outcome assessors). Such studies should also adhere to the methodological recommendations for complex interventions (Craig 2008), for example by performing a process evaluation alongside the clinical trial to assess the degree and fidelity of implementation as well as barriers and facilitators (Moore 2015). To improve the reporting quality, available reporting guidelines for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, Möhler 2015, or for a better reporting of interventions, Hoffmann 2014b, can be used in addition to design specific guidelines (e.g. CONSORT) (Schulz 2010).

In order to enrich theoretical understanding, further studies are needed to explore the potential benefits of personally tailored activities for people with dementia living in the community. The concept of ’meaningfulness’ of activities needs further investigation, that is how meaningfulness can be assessed and how activities can be selected based on the results of the assessment. The perspective of people in different stages of dementia can add valuable information in this field, and the perspective of both people with dementia and their family members can be beneficial to improve the feasibility and acceptability of programmes offering personally tailored activities.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 5, 2013 Review first published: Issue 8, 2020

Acknowledgements