Abstract

Background

Many people with dementia are cared for at home by unpaid informal caregivers, usually family members. Caregivers may experience a range of physical, emotional, financial and social harms, which are often described collectively as caregiver burden. The degree of burden experienced is associated with characteristics of the caregiver, such as gender, and characteristics of the person with dementia, such as dementia stage, and the presence of behavioural problems or neuropsychiatric disturbances. It is a strong predictor of admission to residential care for people with dementia.

Psychoeducational interventions might prevent or reduce caregiver burden. Overall, they are intended to improve caregivers' knowledge about the disease and its care; to increase caregivers' sense of competence and their ability to cope with difficult situations; to relieve feelings of isolation and allow caregivers to attend to their own emotional and physical needs. These interventions are heterogeneous, varying in their theoretical framework, components, and delivery formats. Interventions that are delivered remotely, using printed materials, telephone or video technologies, may be particularly suitable for caregivers who have difficulty accessing face‐to‐face services because of their own health problems, poor access to transport, or absence of substitute care. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, containment measures in many countries required people to be isolated in their homes, including people with dementia and their family carers. In such circumstances, there is no alternative to remote delivery of interventions.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and acceptability of remotely delivered interventions aiming to reduce burden and improve mood and quality of life of informal caregivers of people with dementia.

Search methods

We searched the Specialised Register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, MEDLINE, Embase and four other databases, as well as two international trials registries, on 10 April 2020. We also examined the bibliographies of relevant review papers and published trials.

Selection criteria

We included only randomised controlled trials that assessed the remote delivery of structured interventions for informal caregivers who were providing care for people with dementia living at home. Caregivers had to be unpaid adults (relatives or members of the person's community). The interventions could be delivered using printed materials, the telephone, the Internet or a mixture of these, but could not involve any face‐to‐face contact with professionals. We categorised intervention components as information, training or support. Information interventions included two key elements: (i) they provided standardised information, and (ii) the caregiver played a passive role. Support interventions promoted interaction with other people (professionals or peers). Training interventions trained caregivers in practical skills to manage care. We excluded interventions that were primarily individual psychotherapy.

Our primary outcomes were caregiver burden, mood, health‐related quality of life and dropout for any reason. Secondary outcomes were caregiver knowledge and skills, use of health and social care resources, admission of the person with dementia to institutional care, and quality of life of the person with dementia.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection, data extraction and assessment of the risk of bias in included studies were done independently by two review authors. We used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) to describe the interventions. We conducted meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model to derive estimates of effect size. We used GRADE methods to describe our degree of certainty about effect estimates.

Main results

We included 26 studies in this review (2367 participants). We compared (1) interventions involving training, support or both, with or without information (experimental interventions) with usual treatment, waiting list or attention control (12 studies, 944 participants); and (2) the same experimental interventions with provision of information alone (14 studies, 1423 participants).

We downgraded evidence for study limitations and, for some outcomes, for inconsistency between studies. There was a frequent risk of bias from self‐rating of subjective outcomes by participants who were not blind to the intervention. Randomisation methods were not always well‐reported and there was potential for attrition bias in some studies. Therefore, all evidence was of moderate or low certainty.

In the comparison of experimental interventions with usual treatment, waiting list or attention control, we found that the experimental interventions probably have little or no effect on caregiver burden (nine studies, 597 participants; standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.35 to 0.23); depressive symptoms (eight studies, 638 participants; SMD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.12); or health‐related quality of life (two studies, 311 participants; SMD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.32). The experimental interventions probably result in little or no difference in dropout for any reason (eight studies, 661 participants; risk ratio (RR) 1.15, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.53).

In the comparison of experimental interventions with a control condition of information alone, we found that experimental interventions may result in a slight reduction in caregiver burden (nine studies, 650 participants; SMD ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐0.51 to 0.04); probably result in a slight improvement in depressive symptoms (11 studies, 1100 participants; SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.43 to ‐0.06); may result in little or no difference in caregiver health‐related quality of life (two studies, 257 participants; SMD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.21); and probably result in an increase in dropouts for any reason (12 studies, 1266 participants; RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.20).

Authors' conclusions

Remotely delivered interventions including support, training or both, with or without information, may slightly reduce caregiver burden and improve caregiver depressive symptoms when compared with provision of information alone, but not when compared with usual treatment, waiting list or attention control. They seem to make little or no difference to health‐related quality of life. Caregivers receiving training or support were more likely than those receiving information alone to drop out of the studies, which might limit applicability. The efficacy of these interventions may depend on the nature and availability of usual services in the study settings.

Plain language summary

Remotely delivered information, training and support for informal caregivers of people with dementia

Review questions

We were interested in remotely delivered interventions involving information, training and support for family caregivers of people with dementia. By remotely delivered, we meant that they were provided over the telephone or on a computer or mobile electronic device. We asked whether these kinds of intervention helped caregivers more than doing nothing, and also whether interventions that included elements of training and support worked better than simple provision of information about dementia.

Background

Caring for a family member or friend with dementia can offer positive experiences, but often also has negative consequences for the caregiver. These negative consequences may be emotional, physical, social and financial, and are sometimes described as caregiver 'burden.' Many interventions have been developed to try to help caregivers in their caring role. Often, these interventions involve several components. In this review we divided the intervention components into information (increasing caregivers' knowledge about dementia), training (helping them to practice important skills for successful caring) and support (providing an opportunity to share experiences and feelings with other people). We chose to review only interventions delivered remotely, in part because we were writing during the COVID‐19 pandemic, when many countries required people to remain in their homes. However, remotely delivered interventions may also be useful in many other kinds of situations when it is difficult for caregivers to access services in person.

Study characteristics

We searched up to April 2020 for randomised controlled trials that addressed our review questions. We found 12 studies with 944 participants that compared groups of caregivers receiving usual care, or some non‐specific contact with researchers, with other groups receiving remotely delivered interventions that involved information with training, support or both. We found another 14 studies with 1423 participants that compared simple information provision with more complex interventions that involved training or support. The interventions lasted an average of 16 weeks. Three studies took place in China; all the others were from North America or Europe. About half used the telephone and about half used the Internet to deliver the interventions.

What are the main results of our review?

Compared with the usual services provided for caregivers where the studies took place, or with non‐specific contact with the researchers, we found that the information, training and support interventions probably had no important effect on caregivers' overall burden, depressive symptoms, or quality of life. Caregivers in both groups may have been equally likely to drop out of the studies for any reason. Compared to information only, interventions which included training and support may result in a slight reduction of caregiver burden, probably reduce depressive symptoms, may have little or no effect on quality of life, and probably make it more likely that caregivers drop out of the studies. We did not find any obvious effects of different intervention components, but we were not able to draw any firm conclusions about this. There was no evidence on whether the interventions improved the quality of life of the people with dementia who were being cared for. We did not find any studies that reported harmful effects of the interventions or the additional burden they might add to the caregiver's life. We do not know how the interventions would perform in countries where few health and social care services are available for people with dementia and their families, or in situations where caregivers are unable to access usual services.

How reliable are these results?

We found that most studies were well‐conducted, but because most outcomes were subjective, there was a risk that the expectations of the caregivers and researchers could have influenced results. For some outcomes, there were inconsistent results among studies. Overall, our confidence in our findings was moderate or low so the results could be affected by further research.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

It is estimated that worldwide, about 50 million people have dementia, and there are nearly 10 million new cases every year (WHO 2020). Many people with dementia are being cared for at home by an unpaid informal caregiver, who is usually a female family member, often a spouse or daughter. It is estimated that family caregivers spend five to 20 hours per day and an average of 60 hours per week caring for the person living with dementia (Marziali 2006).

As a consequence of their role as caregiver of a person with a progressive and irreversible disease, the informal caregiver may experience a range of physical, emotional, financial and social harms (Collins 2011). This situation has been widely described in the literature and is known as caregiver burden (Dillehay 1990; George 1986). Caregiver burden is associated with characteristics of the caregiver, such as gender, and characteristics of the person with dementia, such as behavioural problems, stage of dementia and the presence of neuropsychiatric disturbances (Haley 2004). It is a strong predictor of a move from home care to residential care for people with dementia (Eska 2013).

Description of the intervention

A variety of psychosocial interventions have been suggested to prevent or to reduce the negative consequences of dementia care on informal caregivers (Cooke 2001; Etters 2008; Pusey 2001; Selwood 2007). The interventions are generally heterogeneous regarding (i) their theoretical framework, (ii) the focus and the type of interventions reported (e.g. behavioural intervention, stress management, education about the disease), and (iii) the administration format (group or individual, generic or tailored to specific needs, telephone‐ or Internet‐based).

Interventions that are delivered remotely using written materials, the telephone or Internet may be particularly suitable for caregivers of people with dementia who can struggle to access face‐to‐face services because of their own health problems, poor access to transport, or difficulties finding substitute care. At the time of writing, measures used by many countries to contain the COVID‐19 pandemic require that most people, including people with dementia and their family carers, are confined to their homes, isolating themselves from direct contact with others. In such circumstances, there is no alternative to remote delivery of interventions.

There are also, however, significant barriers to remote delivery of interventions, particularly for older caregivers. They may have sensory impairments or other disabilities that make use of the necessary technologies difficult. They may also lack confidence with the technologies involved and may particularly value direct contact with others, being less familiar than many younger people with the experience of finding support in online communities.

This review assesses the efficacy and acceptability of remotely delivered interventions that aim to offer information, training and support, or a mixture of these, to informal carers of people with dementia.

Information

We considered information interventions to have two key elements: (i) they involve the provision of standardised information whose contents are determined by the professional; and (ii) the participant has a passive role (i.e. there is no interaction with the professional or active practice of skills). The intervention can address various aspects: issues related to the person with dementia (e.g. signs and symptoms, natural history, treatments and care alternatives), their care (e.g. activities of daily living, nutrition, communication with the person with dementia), the difficulties derived from their care (behavioural problems, role incompatibility, use of drugs, sleep disturbances), or resources available in the community (Gallagher‐Thompson 2010). The format of implementation can vary: leaflets, manuals, lectures or audio‐visual presentations. The nature of these interventions makes them relatively easy to deliver remotely.

Training

The key element of training interventions is to provide caregivers with the practical skills to manage the burden of care. Caregivers will play an active role in the program (e.g. through supervised practice, or role playing). The training may relate to the care of the person with dementia (e.g. recognising behavioural triggers, communicating more effectively, tailoring tasks to patients' capabilities) or to management of the caregiver's psychological stress. Training can be classified into the following categories: (i) meeting patients' basic care needs, (ii) managing behavioural problems, and (iii) managing and coping with caregiver stress (Losada Baltar 2004; Martin‐Carrasco 2014). Delivery of these elements remotely is likely to be more challenging than the simple provision of information.

Support

The key element of support interventions is the participants' active role in discussing and sharing feelings, problems or issues related to care with other caregivers and professionals (Winter 2006). This category could include two types of support: (i) peer support (e.g. participation in a caregivers' group that is not professionally facilitated), and (ii) professional support (e.g. receiving counselling from a health professional) (Mittelman 2004). Peer support groups, in particular, are usually face‐to‐face, but as technologies develop, it is increasingly possible for these to take place online.

How the intervention might work

Interventions for caregivers of people with dementia may work in a variety of ways depending on the content. Broadly speaking, they are intended to improve caregivers' knowledge about the disease and its care (Ducharme 2011; Liddle 2012); to increase their sense of competence (Laakkonen 2012) and their ability to cope with difficult situations (e.g. behavioural disturbances, communication problems) (Cheng 2012); and to relieve feelings of isolation, as well as to allow caregivers to attend to their own emotional and physical needs (Roth 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

Throughout the world, the majority of care for people with dementia is provided by family members. Anything that can be done to ease the burden of this care will be good for the caregivers and for the people they care for. It may also ease the burden on health and social care systems, for example by improving caregivers' health and by delaying institutional care for the person with dementia. All health and care systems are struggling with the magnitude of the problem presented by dementia. Remote delivery of interventions to support caregivers, if acceptable and effective, offers the opportunity to reach more people than conventional services, potentially at lower cost.

Development of remotely delivered interventions acquired a new urgency in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. The strain on family caregivers who are isolated with a person with dementia is hugely magnified. Not only are they cut off from their usual community and professional supports, but so is the person with dementia, whose behaviour may be more challenging as a result. Because of their age and vulnerability, these groups may experience more prolonged periods of isolation than other members of the community. Identification of effective interventions for caregivers that can be delivered remotely is needed more than ever.

This review aims to collate the best evidence about the efficacy and acceptability of these interventions to facilitate decision‐making by those designing, delivering and receiving services.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and acceptability of remotely delivered interventions aiming to reduce the burden and improve the mood and quality of life (QoL) of informal caregivers of people with dementia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which caregivers were randomly assigned to remotely delivered psychoeducational interventions that included information with support or training, or to a control condition. The control condition could be simple provision of information or waiting list, usual care or a non‐specific intervention serving as an attention control.

We excluded all non‐randomised studies and also RCTs with a cross‐over design, due to the high risk of carryover effects.

Types of participants

Eligible trials included informal caregivers of people with dementia receiving care at home. The dementia of the cared‐for person could be of any type. We accepted clinical diagnoses or diagnoses reached using formal diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the National Institute on Aging ‐ Alzheimer's Association (NIA‐AA) or the Alzheimer's criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS‐ADRDA). Caregivers had to be unpaid adults (relatives, or members of the person's community; 18 years of age or older), of either sex, and of any ethnic or geographical origin. Studies that included caregivers of people with mixed diagnoses were included only if data on caregivers of people with dementia could be extracted separately.

Types of interventions

We included trials that assessed remote delivery of structured interventions involving training, support, information provision, or combinations of these elements, and that only targeted informal caregivers. We considered an intervention to be structured if there was a clear description of a standard set of components and how they were implemented. They could be delivered using paper, the telephone, the Internet or a mixture of these, but did not involve any face‐to‐face contact with professionals or other caregivers. These interventions had to be compared with a control condition, which could be provision of information alone or a waiting list, usual care or any non‐specific intervention serving as an attention control. Participants in waiting list groups were offered the experimental interventions once the study finished. Participants in attention control groups received a similar amount of contact with professionals to those in the experimental group, but the content of the contact involved no specific information, training or support related to dementia.

The following interventions were excluded:

interventions aimed at healthcare professionals;

interventions aimed at the people with dementia;

respite care interventions;

interventions for caregivers that are individually tailored and whose components are not well defined; and

interventions for caregivers that are predominantly psychotherapy, including interventions based entirely on the cognitive behavioural model (CBT). However, interventions that included elements of CBT as part of a larger, multimodal intervention were eligible for inclusion.

We used the following criteria to identify information, support and training. Information interventions include two key elements: (i) they provide standardised information, and (ii) the caregiver plays a passive role. Support interventions promote caregiver interaction with other people (professionals or peers). Training interventions are structured interventions intended to train caregivers in practical skills in order to prevent or alleviate the negative consequences of care giving.

We used the following operational criteria to categorise the interventions:

| Intervention | Definition | Key elements |

| Information |

Structured programmes with standardised information about issues related to care of people with dementia and caregiver burden. The contents of the intervention can include issues related to:

|

The intervention involves the provision of standardised information whose contents are determined by a professional in charge of the dementia. The participant has a passive role, and there is no interaction with the professional or active learning and practice of appropriate skills. |

| Support |

Programmes that allow the caregiver to talk, discuss or share information about their caregiver issues. There are two types of support:

|

The participant has an interactive role talking, discussing or sharing their feelings, problems or contents related to the care provided with other caregivers or professionals. |

| Training |

Structured interventions intended to empower caregivers with practical skills to manage the issues related to care. The skills to be acquired may relate to the care of the person with dementia, or to the management of the caregiver's psychological stress, according to the following categories:

|

Caregivers play an active role (e.g. through supervised practice, role playing, etc.) in the intervention provided. |

We compared (1) all interventions involving training, support or both, with or without information provision, with usual treatment, waiting list or attention control and (2) all interventions involving training, support or both, with or without information provision, with provision of information alone. We used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist to describe the interventions tested in each included trial, to obtain a detailed account of the assessed interventions, and to improve comparability among studies (Hoffmann 2014).

Types of outcome measures

We focused on outcomes that have been identified as relevant to evaluate effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in dementia care (Moniz‐Cook 2008).

Primary outcomes

Caregiver burden, measured by validated questionnaires such as the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) or the Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SCQ 27).

Caregiver mood or psychosocial well‐being, measured by validated questionnaires such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), or the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ).

Caregiver health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), measured by the EuroQoL Group's instrument (EUROQOL), the 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) or the World Health Organization (WHO) Quality of Life assessment tool (WHOQOL).

Acceptability of the intervention: we used dropouts for any reason as a surrogate for the acceptability of interventions.

Secondary outcomes

Caregiver knowledge and skills.

Use of health or social resources.

Admission of the person with dementia to institutional care.

QoL of the person with dementia, measured by validated questionnaires such as the specific Quality of life in Alzheimer's disease (QOL‐AD) instrument, the Dementia Quality of Life (DQOL) instrument, or the generic EQ‐5D instrument.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS, the Specialised Register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) on 10 April 2020. We used the following terms: (caregiv* or carer*) and (support* or information* or program* or training* or psychoeducation* or psycho‐education* or skill* or education* or tele* or video* or computer* or internet* or online or stress*). In addition, when trials are added to the ALOIS database, they are assigned a 'study aim.' One of the possible study aims is "caregiver focussed." We searched the whole database using this aim filter.

ALOIS is maintained by the Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG), and contains studies that fall within the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and management, and cognitive enhancement in healthy elderly populations. The studies are identified through:

Monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo and LILACS;

Monthly searches of a number of trial registers: ISRCTN; UMIN (Japan's Trial Register); the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; the Chinese Clinical Trials Register; the German Clinical Trials Register; the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others);

Quarterly search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

Six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature source: ISI Web of Science Core Collection.

To view a list of all sources searched for ALOIS, see About ALOIS on the ALOIS website (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois).

We also ran additional searches in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and CENTRAL. We searched two international trials registries, ClinicalTrials.gov at the US National Institutes of Health, and the WHO ICTRP, to ensure that the search was as comprehensive and as up‐to‐date as possible. We have presented the search strategies used and the number of results retrieved in Appendix 1.

The most recent search for this review was done on 10 April 2020. Before that date, we had run searches in December 2015, July 2016, May 2017, May 2018 and May 2019.

Searching other resources

We complemented this search with manual searches of the bibliographies of relevant review papers and published trials to locate additional relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of review authors (two of EGF, JRR, JB) independently examined the titles and abstracts of citations obtained by the searches to identify studies that may meet the inclusion criteria. We retrieved the full‐texts of all potentially eligible articles and examined these against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, again independently and in duplicate. Studies excluded and reasons for exclusion are reported in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors (two of EGF, JRR, BS, JB) independently extracted data using a standardised data collection form. In case of disagreement, another review author (IS) was consulted and consensus sought. For each study, extracted data included: trial registry identification, funding and potential conflicts of interest, main methodological characteristics, results. We described the key characteristics of each trial in tables, paying special attention to the characteristics of the interventions assessed. We described the interventions according to the TiDieR checklist (Hoffmann 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in included studies by following the guidance of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Pairs of review authors (two of EGF, JRR, JB) extracted the appropriate information and independently rated the risk of bias for each study and outcome. In case of disagreement, another review author (IS) was consulted and consensus sought. We assessed the following sources of bias: selection bias (including random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessments); attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); and reporting bias (selective reporting).

Using 'Risk of bias' tables, we rated the risk of bias in each domain as either "low risk," "unclear risk" or "high risk" and provided an explanation for each rating. We considered trials with inadequate randomisation and lack of blinding (for outcome assessment) as being at overall "high risk of bias."

Measures of treatment effect

We used the risk ratio (RR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) as the measure of treatment effect for dichotomous data and the mean difference (MD) with its 95% CI as the measure of treatment effect for continuous data. We used the SMD with its 95% CI for continuous outcomes only if similar outcome constructs were measured by different rating scales.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual allocated to a treatment group. We did not identify any eligible cluster‐randomised trials. If a trial reported outcomes at more than one time point (e.g. weekly or monthly outcome measures; end‐of‐trial and follow‐up outcome measures), we extracted the measure closest in time to the end of treatment and used this as a measure of the acute effect of the intervention. If a trial included more than one control or experimental group, we followed the guidance of the updated Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020). When managing several eligible experimental interventions versus a unique control, we split the control sample to avoid over‐counting participants. Where there was more than one control group, we combined these if it was conceptually reasonable to do so.

Dealing with missing data

We used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data where this was reported. If an included study imputed missing data, we reported the data imputation method.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered heterogeneity in study characteristics to decide if combining the results would be clinically meaningful. If we judged the studies to be too heterogeneous, then we did not conduct meta‐analyses, but reported individual results. We assessed between‐studies heterogeneity in meta‐analyses using the I2 statistic, complemented with the examination of overlapping 95% CI.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed small study bias using funnel plots where there were 10 or more studies in a comparison.

In the bibliographic searches, if we found any RCT included in any clinical trial register that we considered could have been completed, but for which we had not been able to locate any results, we contacted the authors to request information about the status of the trial, and the trial results, if it had been completed.

Data synthesis

If we considered trials to be sufficiently similar that it was appropriate to pool data, we conducted meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model for two main comparisons:

a comparison of all interventions involving information, training or support versus usual treatment, waiting list or attention control;

a comparison of all interventions involving training or support (with or without information) versus information alone.

Where there were sufficient data, we stratified the analyses by type of intervention.

We conducted all analyses in Review Manager version 5.3 (Review Manager 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Depending on availability of data, we intended to conduct subgroup analyses according to:

the intensity/length of the intervention provided;

the mode of delivery of the intervention: telephone‐only versus Internet with or without telephone;

the characteristics of participants; and

the outcome scales used to score each construct of interest.

Sensitivity analysis

If feasible, we intended to perform sensitivity analyses to assess the influence of studies at higher risk of bias, and the impact of attrition on the robustness of the pooled results. However, the small number of included studies by group comparison precluded reliable sensitivity analyses. Another form of sensitivity analysis, the leave‐one‐study method, did not identify any specific study as highly influential on the combined results.

'Summary of findings' tables

We summarised the review findings in a 'Summary of findings' table using the online GRADEpro GDT application (GRADEpro GDT). In the table, we reported the estimated treatment effects for the review's primary outcomes and for resources use and institutionalisation. For each effect estimate, we used the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2013) to rate our confidence that the estimate is correct (high, moderate, low or very low certainty). GRADE ratings take account of study limitations, imprecision of effect estimates, inconsistency among studies, indirectness of evidence and publication bias. When assessing imprecision, we considered that an absolute value of SMD 0.50 probably represented an important between‐group difference. We considered inconsistency to be substantial enough to downgrade our confidence in the effect estimate if we found I2 to be greater than 60%.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

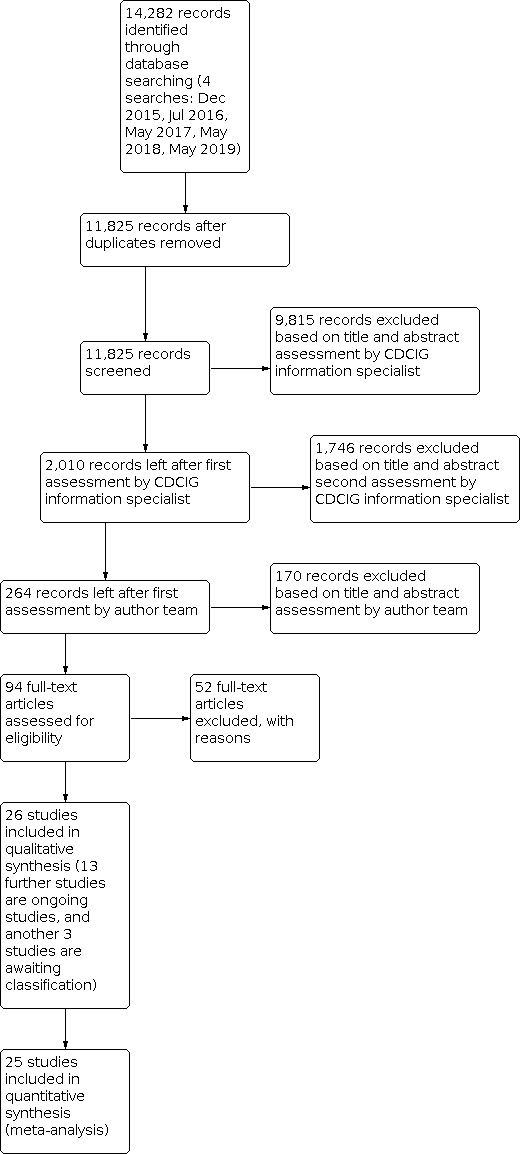

After a first assessment by the CDCIG information specialist, we assessed the remaining 2,010 potentially relevant records. Of these, 264 records remained after first assessment by the author team, and after more detailed screening of titles and abstracts, we retrieved 94 full‐text articles for assessment. We excluded 52 articles, recording the reasons for exclusion. We included 26 studies (39 references) in the qualitative synthesis and 25 studies in the quantitative synthesis. Three studies are awaiting classification because they may be eligible, but there is not enough information in their registry protocols to make an eligibility decision (see Studies awaiting classification). Another 13 studies are ongoing studies that have not yet reported results (see Ongoing studies). Figure 1 presents the flow diagram of the study selection process.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We identified 26 studies with 2367 participants for inclusion in the review (see Characteristics of included studies).

Setting and participants

Included studies were conducted or published over 25 years (from 1995 to 2020). Most studies were from the US (15 studies, 58%). China and the Netherlands contributed three studies each, France two studies, and Canada, Spain and the UK one study each. Studies had a median sample size of 67 participants (interquartile range (IQR) 49 to 110) and a median duration of 16 weeks (IQR 12 to 24). Only six studies (23%) provided data for a continuation follow‐up after the end of the intervention (median of 24 weeks).

Most caregivers were female (72%) with a median age of 63 years (range 51 to 72 years) . Care recipients were mainly diagnosed with dementia due to Alzheimer's disease (83%), had a median age of 78 years (range 62 to 81 years) and had been treated for dementia for a median of 38.5 months (range 30 to 53 months).

Interventions

We examined the descriptions of the experimental interventions in the included studies to look for elements meeting our definitions of information, training and support. Almost all of the experimental interventions specified provision of information to caregivers as a component of a more complex intervention. We considered this element was not present in only three studies: Davis 2004 and Dowling 2014, which we considered to be relatively pure training interventions, and Winter 2007, which we considered to be a relatively pure support intervention. However, even in these cases, it was possible that some provision of information did occur during the course of delivery of the other elements. Therefore, we constructed three subgroups of experimental intervention based on the predominant components: training with or without information, support with or without information, and interventions including both support and training elements. We considered these groups to be exploratory, recognising that all the interventions were complex in nature and that there is inevitably some overlap among the categories.

We classified the experimental intervention in 12 studies as training or training with information (Au 2015; Au 2019; Blom 2015; Czaja 2013; Davis 2004; Dowling 2014; Gant 2007; Kajiyama 2013; Martindale‐Adams 2013; Metcalfe 2019; NCT00056316; NCT03417219), in eight studies as support or support with information (Brennan 1995; Hattink 2015; Hayden 2012; Kwok 2013; Mahoney 2003; Nunez‐Naveira 2016; Torkamani 2014; Winter 2007), and in six studies as involving both training and support with information (Cristancho‐Lacroix 2015; Duggleby 2018; Gustafson 2019; Huis in het Veld 2020; Tremont 2008; Tremont 2015). Fourteen studies delivered the remote intervention by telephone and 12 using the Internet.

Eight studies included usual treatment (Brennan 1995; Cristancho‐Lacroix 2015; Mahoney 2003; Nunez‐Naveira 2016; Torkamani 2014; Tremont 2008) or waiting list (Hattink 2015; Metcalfe 2019) as the control condition. Four studies provided some form of attention control during the treatment period, with or without socially supportive telephone calls (Davis 2004; Dowling 2014; Hayden 2012; Tremont 2015). Eight studies provided specific information on dementia and related problems (Blom 2015; Duggleby 2018; Gustafson 2019; Kajiyama 2013; Kwok 2013; Martindale‐Adams 2013; NCT03417219; Winter 2007) in the control condition. Six further studies provided both information and some form of control attention (Au 2015; Au 2019; Czaja 2013; Gant 2007; Huis in het Veld 2020; NCT00056316).

The TIDieR checklist for included studies is reported in Additional tables (Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13; Table 14; Table 15; Table 16; Table 17; Table 18; Table 19; Table 20; Table 21; Table 22; Table 23; Table 24; Table 25; Table 26; Table 27; Table 28 ).

1. TIDieR ‐ Au 2015.

| Study | Au 2015 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Psychoeducation with behavioral activation (PsyED‐BA). | Psychoeducation only (PsyED). |

| WHY | Based on the Gallagher‐Thompson’s program Coping with Cargiving. The aim is to enhance the use of coping skills via behavioral activation (BA), since it would be more acceptable and helpful than change dysfunctional thoughts, overcome barriers to treatment access and train paraprofessionals to deliver some modules of the program. | General discussion about the psychoeducation program and information packet. |

| WHAT materials | Caregivers were given a printed copy of the psychoeducation program (adapted from the Chinese version of the Coping with Caregiving manual) together with an information packet with fact sheets concerning local organizations, community resources, and social and mental issues related to dementia. 1.‐ Patient‐Change Workshop, Procedures Manual, Progress Notes, Problem Behavior Tracking forms, written cueing systems for repetitive verbal behavior, audio/videotape or tactile diversion program for repetitive vocal and physical behaviours, and verbal and physical prompting procedures for continence and self‐feeding problems, Caregiver Self‐Change Recording Form. 2.‐ Self‐change Workshop, Problem Behavior Tracking forms, Caregiver‐self change recording form. |

Caregivers were given a printed copy of the psychoeducation program (adapted from the Chinese version of the Coping with Caregiving manual) together with an information packet with fact sheets concerning local organizations, community resources, and social and mental issues related to dementia. |

| PROCEDURES | Participants were contacted by telephone within the same week of the baseline assessment to start the psychoeducation program. There were a total of four weekly intervention telephone calls, each lasting about 30 minutes. ‐ In the first week, all participants were taught about the symptoms and associated behavioral changes of dementia and the possible effects on the caregivers. Participants were also invited to share their caregiving experiences. ‐ In the second week, participants learned about the physical, social, and psychological consequences of stress and being aware of their own stress. They were invited to talk about their own stress. ‐ In the third week, they learned about the principles of identifying and scheduling pleasant events for themselves. ‐ In the fourth week, participants learned about communication: communicating their own needs to seek support from their family members. They also learned about the characteristics of various different types of communications: passive, aggressive, and assertive. Participants had eight biweekly telephone sessions over the following 4 months. Each session consisted of a telephone call lasting 15 to 20 minutes. The first four sessions focused on pleasant event scheduling and the other four sessions on effective communication. The tasks involved in each of the four sessions were as follows: 1. Activity monitoring: how is the participant spending time/ communicating now? 2. Activity scheduling: schedule pleasant event/effective communications 3. Reinforcing or modifying the pleasant event and communication based on feedback or self‐evaluation 4. Activity rescheduling/revision based on changes after modification. Finally, social work services were available upon requests in outpatient departments in which the care recipients received their regular follow‐up. |

Participants were contacted by telephone within the same week of the baseline assessment to start the psychoeducation program. There were a total of four weekly intervention telephone calls, each lasting about 30 minutes. Participants had eight biweekly telephone sessions over the following 4 months. Each session consisted of a telephone call lasting 15 to 20 minutes: ‐ Participants were asked to go through the materials of the psychoeducation program and the information package. For each of the telephone session, the participants were asked to select their own topics for general discussion. If the caregiver selected pleasant event scheduling or communications, general discussion would be carried out without any BA procedures. Finally, social work services were available upon requests in outpatient departments in which the care recipients received their regular follow‐up. |

| WHO provided | Five paraprofessionals recruited trained to administer BA procedures. They were between 55 and 60 years old and had previously completed post‐secondary school training in areas related to human services (i.e., nursing or management). They had subsequently completed a 42‐hour course on Introduction to Psychology and had then received 20 hours of group training led by a social worker and a clinical psychologist (the principal investigator of the study) on BA in the context of the Copy with Caregiving program. Each paraprofessional worker was tested on a mock case before delivering the program to actual caregivers. Ongoing weekly supervision was provided by the clinical psychologist and social worker. | |

| HOW delivered | Individually over the telephone. | |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | Twelve sessions: sessions 1 to 4 were delivered weekly, sessions 5 to 12 were delivered biweekly. Each session consisted of a telephone call lasting 15 to 20 minutes. | |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | No described. | |

| HOW WELL actual | No described. | |

2. TIDier ‐ Au 2019.

| Study | Au 2019 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Psychoeducation with behavioral activation (TBA). | General Monitoring (TMG). |

| WHY | Behavioral activation (BA) focuses on constructing reinforcement contingencies that increase functional behavior and self‐efficacy. Self‐efficacy refers to the person’s beliefs about the abilities to exercise control on the events affecting their lives. The intervention was adapted from the Chinese Version of the Coping with Caregiving. | General discussion about the psychoeducation program and information packet. |

| WHAT materials | Written information, including the forms for pleasant event scheduling, was mailed to participants before the program started. | Information packet. |

| PROCEDURES | Four weekly sessions of psychoeducation and eight sessions of behavioral activation. Themes of the psychoeducation component were as follows. Session 1 (week 1): · Symptoms and associated behavioral changes in dementia · Stages in dementia · Caregiving roles and demands · Effects on caregivers Session 2 (week 2): · Physical, social and psychological consequence of stress · Identifying stress reactions · Awareness of stress · Stress and well‐being Session 3 (week 3): · The effect of life events on mood · Tracking daily/ weekly events · Identifying pleasant events · Scheduling pleasant events Session 4 (week 4): · Communication needs to family members · Types of communications: passive, aggressive and assertive · Resources available in the community · Planning in the future Themes of the behavioral activation component were: · Session 1 – Review the present use of time. Using the monitoring form · Session 2 – Brain‐storm pleasant events. Scheduling pleasant activities · Session 3 – Review scheduling of events. Discuss how to improve · Session 4 – Review modifications. Consolidate gains on scheduling · Session 5 – Review present social support. Explore new sources of support · Session 6 – Examine communication skills. Explore new options · Session 7 – Review new communications. Discuss how to improve · Session 8 – Review modification. Consolidate gains on support |

All TGM participants received four weekly psycho‐education sessions over the phone with the same contents as in the TBA group. These caregivers were then assigned to eight bi‐weekly sessions of general monitoring with no BA intervention. Each of these sessions started with checking in with the caregiver through inviting them to update their caregiving situation. Caregivers were then guided to discuss one of the following topics at each session in this order: 1. caregiver’s health 2. care‐recipient’s needs 3. caregiver’s routines 4. social support. As there were a total of eight sessions, the last four sessions repeated the order of the first four. While some caregivers might report on attempts they made on their own initiative to improve their scheduling and communication, no specific attempt was made to ask them to review these attempts. |

| WHO provided | An interventionist with a degree in social work delivered all the four sessions of psycho‐education. Six paraprofessional coaches, between 50 and 60 years old and with an undergraduate degree in helping or service professions, delivered the BA or MG interventions, or carried out monitoring. A social worker and a clinical psychologist provided the training and facilitated weekly supervision separately for TBA and TGM coaches. | |

| HOW delivered | Individually over the telephone. | |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | Twelve sessions: sessions 1 to 4 were delivered weekly and sessions 5 to 12 were delivered biweekly. Each session lasted about 20 minutes. | |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | The program fidelity was assessed by a rating system built into recording form. At the end of each session, all interventionists, including the paraprofessionals, were asked to rate to what extent they were able to follow the protocol for each of the four PE sessions (3 = fully; 2 = adequately with at least 60% of the material covered; 1 = slightly; 0 = not at all). A similar procedure was adopted for each of the 8 sessions for both TBA and TGM. In addition, 10 cases from TBA and 10 cases from TGM were audiotaped. Interventionists’ adherence to the intervention protocol was assessed by two graduate students who had received eight hours of training on the coding scheme. The sessions were coded with reference to four core TBA strategies (activity planning, review to improve on scheduling, develop new help‐seeking communication skills and review to improve on communications) and four core TGM strategies (updating on caregiving situation, health and needs of the caregiver and the care‐recipient, daily routines and family communications). | |

| HOW WELL actual | As planned. Minimal deviations to the main components of the intervention. | |

3. TIDieR ‐ Blom 2015.

| Study | Blom 2015 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Mastery of dementia (MoD). | Minimal Intervention (e‐bulletins). |

| WHY | A guided self‐help Internet course ‘Mastery over Dementia’ (MoD) designed to reduce caregivers’ symptoms of depression and anxiety. MoD included a combination of psycho‐education with active participation of the caregiver, management of behavioral problems, teaching coping strategies, components of cognitive behavioral therapy (cognitive reframing: changing non‐helpful into helpful thoughts), and increasing social support. | No applicable. |

| WHAT materials | Internet contents. | E‐bulletins (digital newsletters). |

| PROCEDURES | The Internet course consists of 8 lessons and a booster session with the guidance of a coach monitoring the progress of participants and evaluating the homework. Each lesson has the same structure and consists of information (text material and videos), exercises, and homework, with an evaluation at the start and end of each session. The elements of the course were presented in the following order: · coping with behavioral problems (problem solving) · relaxation · arranging help from others · changing non‐helping thoughts into helping thoughts (cognitive restructuring) · communication with others (assertiveness training). The booster session was provided a month after participants finished the eight lessons, and provided a summary of what was learned. After every lesson, participants sent their homework to a coach via a secure application. The coach sent electronic feedback to caregivers on their homework within three working days. The feedback had to be opened before the next lesson could be started. Participants were automatically reminded to start with a new lesson or to send in their homework if they were not active for a fixed period of time. All participants in this study received feedback from the same coach, a psychologist employed by a health care agency with additional training in cognitive behavioral therapy and experience in the field of dementia. |

Caregivers received a minimal intervention consisting of e‐bulletins (digital newsletters) with practical information on providing care for someone with dementia. The bulletins were sent by email according to a fixed schedule (every 3 weeks) over nearly 6 months. The topics of the bulletin, which did not overlap with the content of MoD, were: · driving · holiday breaks · medication · legal affairs · activities throughout the day · help with daily routines · grieving · safety measures in the home · possibilities for peer support. There was no contact with a coach over the length of the study. |

| WHO provided | Internet intervention. A coach monitored the progression of the participants. | No applicable. |

| HOW delivered | Online. | |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | Eight lessons plus a booster session. | The bulletins were sent by email according to a fixed schedule (every 3 weeks) over nearly 6 months. |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | No described. | |

| HOW WELL actual | No described. | |

4. TIDieR ‐ Brennan 1995.

| Study | Brennan 1995 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | ComputerLink. | None beyond general information to identify local resources. |

| WHY | The intervention aimed to help caregivers develop problem‐solving skills, manage their own emotions, and increase their knowledge of dementia and caregiver‐support strategies. | No applicable. |

| WHAT materials | Caregivers received a Wyse 30 terminal and a Everex modem system. | No applicable. |

| PROCEDURES | ComputerLink provided three functions: · information · decision support · communication The electronic Encyclopedia provided extensive factual information to enhance self‐care and understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and promote health management of the care recipient. The program uses a system to help caregivers to resolve problems basing in the multiattribute utility theory of von Winterfeldt & Edwards. ComputerLink permitted several options for communication among caregivers, including private mail, access to a public bulletin board, and a section of questions and answers. A nurse moderator entered the system daily and read and responded to messages. The nurse served as a moderator and facilitator. |

None beyond general information to identify local resources. |

| WHO provided | Study nurses who had completed an intervention training programme. | No applicable. |

| HOW delivered | Online. | No applicable. |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | No applicable. |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | Participants had access to the system 24 hours a day during 12 months. | No applicable. |

| TAILORING | Intervention was comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | No applicable. |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | No applicable. |

| HOW WELL planned | Indicators for logging in the system. | No applicable. |

| HOW WELL actual | Caregivers logged into the system 3,875 times, They accessed it a mean of 83 times over 12 months. A typical encounter lasted 13 minutes. | No applicable. |

5. TIDieR ‐ Cristancho‐Lacroix 2015.

| Study | Cristancho‐Lacroix 2015 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Diapason. | Treatment as usual. |

| WHY | The program’s content on the web was based on cognitive theories of stress. | No applicable. |

| WHAT materials | Web materials. | No applicable. |

| PROCEDURES | · Session 1: Caregiver stress – this session presents a definition of stress, its causes and consequences on caregivers, risk factors for chronic stress, and mechanisms and effects of relaxation (includes a link to the relaxation training in the Diapason website), as well as strategies for managing stress underlining the importance of looking for respite. · Session 2: Understanding the disease – in this session, the Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis procedure, the symptoms, the progression of the illness, and the consequences on daily life activities for persons with Alzheimer’s disease (PWAD) are explained. · Session 3: Maintaining the loved ones’ autonomy – this session presents the reasons and strategies to involve loved ones in the process of care in order to stimulate the preserved functions and compensate for the lost ones. The session underlines the importance of maintaining the self‐esteem of PWAD. · Session 4: Understanding their reactions – in this session, the most frequent behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and their characteristics are succinctly described and illustrated by examples from daily life. The contextual and intrinsic factors that might be associated with them are also described. · Session 5: Coping with behavioral and emotional troubles – this session presents practical advice on how to cope vis‐à‐vis the BPSD described in the previous session. · Session 6: Communicating with loved ones – this session includes the description of the most frequent language troubles and the strategies to modulate and adapt communication to the preserved skills of PWAD. · Session 7: Improving their daily lives – this session presents strategies to facilitate the performance of activities that become difficult or impossible to execute due to apraxia, illustrating them with examples adapted to daily life. · Session 8: Avoiding falls – the session includes practical advice for maintaining and stimulating the relative’s balance and actions to adopt in the event of a fall. In addition, various actions are described to adapt the relative’s home. · Session 9: Pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions – this session includes a brief presentation of different interventions available for caregivers in France with pharmacological treatment as well as cognitive and psychological support. · Session 10: Social and financial support – this session presents the different stakeholders and services that may help caregivers in their daily life. The financial and social support provided by the French government is also revised. · Session 11: About the future – this session provides caregivers with information about the role of disease progression anticipation, inviting them to try and foresee solutions keeping a prospective vision, encouraging them to look for further sources of information, and social support to reduce the uncertainty of caregiving situations. · Session 12: In a nutshell – the last session encompasses a summary of the Diapason program, emphasizing the acceptance of support and help and the importance of obtaining more information to anticipate and avoid stressful circumstances. Additionally the website contains other sections that can be consulted at any time: · Relaxation training: guidelines for learning relaxation as well as 2 videos for the modelling of Schultz’s Autogenic Training and Jacobson’s method. · Life Stories: stories about 4 couples, based on testimonials of caregivers, in which difficult situations are illustrated and possible solutions to manage them are discussed (i.e., apathy of patient, caregivers’ isolation). · Glossary: a glossary for technical words (i.e., neuropsychological assessment, aphasia). · Stimulation: practical activities to stimulate autonomy and share pleasant activities with the relatives in daily life. · Forum: a private and anonymous forum to interact with peers, to express their concerns, discuss solutions to daily problems, and share their feelings and experiences. The participants use nicknames to protect their privacy. A clinical psychologist participates in the discussions if necessary (i.e., avoiding aggressive or inappropriate comments). |

No applicable. |

| WHO provided | No web‐moderate self‐provided intervention except when using the forum resource. | No applicable. |

| HOW delivered | Online. | No applicable. |

| WHERE occurred | Home. | No applicable. |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | The length of the intervention was 3 months, with each weekly session lasting 15 to 30 minutes on average, but there was no time limit and the participants could access different website sections (i.e., relaxation training, forum) for as long as they wished at any time. | No applicable. |

| TAILORING | Intervention was comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | No applicable. |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | No applicable. |

| HOW WELL planned | Indicators for login in the system. | No applicable. |

| HOW WELL actual | On average, participants used the website 19.7 times (SD 12.9) and for 262.2 minutes (SD 270.7) during the first 3 months. | No applicable. |

6. TIDieR ‐ Czaja 2013.

| Study | Czaja 2013 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Named "intervention condition". | Two control conditions which were combined: attention control and information |

| WHY | The intervention condition was modelled after the REACH II intervention. | No described. |

| WHAT materials | A videophone (CISCO IP 7900) was installed in the caregivers’ homes and connected to a Digital Subscriber Line and to a secure server at the host site. Participants in this condition also received a caregiver notebook with basic information about caregiving and community resources. | Caregivers in the attention condition were provided with a notebook with information related to nutrition. The information condition group received educational materials with basic information about dementia, safety, and community resources. |

| PROCEDURES | The intervention included education and skills training. It was designed to address five caregiver risk areas (safety, social support, problem behaviours, depression, and caregiver health). The intervention was standardized with respect to the treatment domains and strategies used within the treatment domains but individualized with respect to the amount of emphasis within a treatment domain based on a risk assessment administered at baseline. Certified interventionists taught problem solving strategies to deal with the care recipients’ problem behaviours and training on stress management, healthy behavior strategies, community resources, and communication strategies. The intervention included six 1‐hour monthly sessions. The four educational seminars were brief video lectures from experts on topics relevant to caregiving (i.e., update on Alzheimer disease, caregiver depression) and were presented serially; a new video appeared monthly beginning in month 2 of the intervention.The intervention also included five videophone support group sessions, which were interspersed throughout the intervention period. The support groups were structured and included up to six caregivers and a certified group leader. During the support group sessions caregivers received topical information (related to the material covered in the individual intervention sessions) and shared experiences and concerns. | Attention condition: participants received two 1‐hour in‐home sessions and four videophone sessions. They also participated in five telephone support group sessions, which were interspersed with the individual intervention sessions. The support groups followed the same format as those for the intervention group. The content for the attention control condition was structured around nutrition and healthy eating. Information condition: participants were mailed a packet of educational materials and received a brief (<15 minute) telephone “check‐in call” at 3 months post randomisation. |

| WHO provided | Interventionists. All assessors and interventionists received training and were certified before entering the field. | |

| HOW delivered | Online plus telephone. | Face to face plus telephone. |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | 6 sessions (1 hour each). | · 6 sessions (1 hour each). · 15 minutes “check‐in‐call”. |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | Interventionists submitted taped treatment sessions for review and feedback as part of the certification. Treatment implementation was monitored and maintained by weekly supervision meetings. Both interventionists and assessors followed a detailed manual of operations and a delivery assessment form was completed after each contact. | |

| HOW WELL actual | No described. | |

7. TIDieR ‐ Davis 2994.

| Study | Davis 2004 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Telephone training or in‐home training (this review only includes evidence from telephone training). | Friendly, socially supportive, telephone calls. |

| WHY | The study was grounded in the stress, appraisal and coping theory of Lazarus. The premise for the caregivers skill training intervention was that improvements in caregiver's outcomes could be addressed by expanding caregiver's repertoire of effective appraisal and coping strategies through telephone training strategies | No applicable. |

| WHAT materials | Caregivers received a standardized, loose‐leaf notebook with suggestions for managing frequently encountered Alzheimer’s disease situations. They had to fill out a weekly log on problems they had managed over the past week. | Socially supportive friendly telephone calls. |

| PROCEDURES | Caregivers participated in training sessions focused on: · general problem solving · caragiver appraisal of behavior problems · written behavioral programs for managing specific problems · strategies for handling effective responses to difficult caregiving situations. They received an initial home visit of 45 minutes to introduce the trained interventionist and to familiarize with the uses of the notebook and log sheets. At each weekly contact, the interventionist reviewed the past week of caregiving problems with the caregiver, discussed the log entries and used selected notebook sections to help the caregiver manage the situation. |

Friendly callers made an initial home visit of approximately 45 minutes to introduce themselves. At the time of each contact, callers required about the caregiver's past week as well as any changes in their general health and medication regimen. |

| WHO provided | Interventionists. | |

| HOW delivered | Telephone. | |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | 12 weekly telephone contacts. | |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | No described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | Telephone contacts were tape recorded and reviewed to assess continued adherence. | |

| HOW WELL actual | Telephone contacts averaged 37 minutes (SD=18) | Friendly telephone calls averaged 16 minutes (SD=12). |

8. TIDieR ‐ Dowling 2014.

| Study | Dowling 2014 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | LEAF (Life Enhancing Activities for Family Caregivers). | Attention control group. |

| WHY | The positive affect intervention teaches participants a series of behavioral and cognitive “skills” for increasing positive affect coping with health‐related and other life stresses. The skills include noticing and capitalizing on positive events, gratitude, mindfulness, positive reappraisal, focusing on personal strengths, attainable goals, and acts of kindness. | No described. |

| WHAT materials | No described. | |

| PROCEDURES | Skill‐building Intervention Sessions · Session 1: Positive Events and Gratitude – Identify a positive or meaningful event in the last week and what it means to note, favour, and capitalize on positive events. Homework: write down 3 things that went well each day and why they went well. Begin a gratitude journal (writing one thing each day you are grateful for) that continued throughout the rest of the intervention. · Session 2: Mindfulness – Teach concepts of mindful attention and non‐judgment. Homework: (a) practice awareness of breathing and meditation for 10 minutes daily and (b) once a day take the time to enjoy something that you usually hurry through, do one thing at a time, and pay attention to it. Participants were encouraged to continue the breathing exercise through the remaining weeks of the intervention and to continue the gratitude journal. · Session 3: Positive Reappraisal – Discuss the meaning of positive reappraisal and how to apply it to everyday occurrences. Homework: each day think of one negative or stressful thing that happened. Practice positive reappraisal – why it may not be as bad as initially thought or something good that might come of it. Participants were encouraged to write about their experience reappraising at the end of each day and to continue their gratitude journal and mindful breathing exercises. · Session 4: Personal Strengths and Attainable Goal – Generate a list of personal strengths that can be used in everyday life. Define attainable goals and practice setting one related to self‐care. Homework: achieve attainable goal. Participants were encouraged to write about their goals at end of day and to continue their gratitude journal and mindful breathing exercises. · Session 5: Altruistic Behaviors/Acts of Kindness – Doing for Others – Discuss the positive impact of doing for others. Homework: do something nice for someone else each day. Participants were encouraged to write about their acts of kindness at end of day and to continue their gratitude journal and mindful breathing exercises. |

Participants randomised to the control group engaged in 5 one‐on‐one sessions with a facilitator. The sessions were comparable in length to the intervention sessions (approximately 1 hour) but consisted of an interview and did not have any didactic portion or skills practice. Each session began with the completion of the modified Differential Emotions Scale (DES). In addition to these affect questions, each session had qualitative and quantitative questions and activities cantered on a theme (i.e., life history, health history, diet and exercise, social networks, and meaning and spirituality), to keep the sessions different and interesting for participants. Home practice for the control group consisted of the brief daily affect reports. At the start of sessions 2 through 6, the facilitator reviewed the previous week’s affect diary with the participant. |

| WHO provided | Facilitators for the intervention sessions were trained for content and delivery. Two were clinical nurse specialists in fronto‐temporal dementia and 1 was a psychologist. | The facilitator for the control group sessions was a research associate, familiar with the content of the intervention sessions so as to not engage in the intervention content during control sessions with participants. |

| HOW delivered | Mainly by video‐conference (only 1 subject participated in‐person, all others participated remotely). | |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | 6 sessions of 1 hour each. | |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | All sessions were audio‐recorded digitally for both quality assurance and intervention evaluation. | |

| HOW WELL actual | No described. | |

9. TIDieR ‐ Duggleby 2018.

| Study | Duggleby 2018 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | My Tools 4 Care (MT4C). | Information. |

| WHY | The aim of the intervention, based on transition theory, was to support carers through transitions and increase their self‐efficacy, hope, and health related quality of life. The intervention had multiple components and included choice, as the carers could choose which sections they would like use, and when. User‐generated content is encouraged throughout the intervention as participants may write in sections, add stories, pictures, music etc. Sections include: · About Me · Common Changes to Expect · Frequently Asked Questions and Resources · Important Health Information (about person they are caring for). |

No applicable. |

| WHAT materials | An online version of the Toolkit entitled My Tools 4 Care (MT4C) (https://www.mytools4care.ca/). | A copy of the Alzheimer Society’s booklet The Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease, sent by email. |

| PROCEDURES | Participants received information for the MT4C website, (i.e., the website address, a unique username and password to access the site for 3 months), and an electronic copy of a Toolkit Checklist in which the participant will be asked to document their use of MT4C (i.e., time spent and content accessed over the 3 months). Participants also received an electronic copy of the Alzheimer Society’s educational booklet, The Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. | The electronic document consists of a five‐part series that describes the stages of Alzheimer’s disease. It is written for the person with Alzheimer disease, their family and carers and is freely accessible via the Alzheimer Society of Canada website. |

| WHO provided | Whole intervention was over the Internet. | No applicable. |

| HOW delivered | Online | Emailed booklet. |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | Intervention was accessible for 3 months. | No applicable. |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | No applicable. |

| HOW WELL planned | Webpage recorded the time and duration of access. | No applicable. |

| HOW WELL actual | 73% of caregivers used MT4C at least once over the 3‐month period. By 3 months, participants spent most of their time on Section 2 – Common changes to expect (median 15 minutes) and Section 4 – Resources (median 10 minutes). | No applicable. |

10. TIDieR ‐ Gant 2007.

| Study | Gant 2007 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | Video/workbook/telephone coaching condition. | Education/check‐in‐call condition. |

| WHY | No described. | |

| WHAT materials | Caregivers in the video condition received a 10‐session video series, a workbook from the Dementia Caregiving Skills Program, and weekly telephone calls from a trained coach. | Participants received by mail a 37‐page booklet, Basic Dementia Care Guide and phone calls. |

| PROCEDURES | The intervention used primarily behavioural strategies: behavioural activation, behavioural management, and stress reduction through relaxation training. The workbook provided didactic and experimental materials to reinforce information presented in each video session. Participants received 12 weekly phone calls by trained research staff who served as coaches. The first 10 calls reinforced each of the video sessions, the last 2 calls served as follow‐up for further application of concepts. Coaches followed a coach manual that provided a script for reviewing didactic materials and assignments with caregivers, and for assisting them in the application of intervention concepts to their problems. During the coaching calls caregivers reported the specific behavioural strategies that they devised, written down, used, and evaluated, based on the behaviour management module that they learned to apply to their situations. | Intervention included information on dementia and suggestions for dealing with a variety of caregiving challenges. In a cover letter, procedures for maximizing the benefits of this educational booklet were provided. Caregivers then received approximately 7 biweekly telephone calls by a trained staff member. In these calls, the staff member checked on the safety of the caregiver and family member, discussed the caregiver’s use of the suggestions from the guide, and responded to questions by referring the caregiver to appropriate sections in the guide. A standardized script was used for calls to participants in this comparison condition. |

| WHO provided | Coaches following a coach manual. | |

| HOW delivered | By telephone. | |

| WHERE occurred | At home. | |

| WHEN and HOW MUCH | 12 weekly telephone calls. | 7 bi‐weekly telephone calls. |

| TAILORING | Interventions were comprehensively designed, not tailored to cover individual or unmeet needs. | |

| MODIFICATIONS | None described. | |

| HOW WELL planned | No described. | |

| HOW WELL actual | No described. | |

11. TIDieR ‐ Gustafson 2019.

| Study | Gustafson 2019 | |

| TIDieR item | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| BRIEF NAME | D‐CHESS (Dementia–Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System). | Caregiving booklet. |

| WHY | D‐CHESS was designed to help with motivation, decision making, stress reduction, and access to services by allowing caregivers to obtain information and support without concern for location, distance, time, confidentiality, or education. | No described. |