Abstract

Background

Extracranial carotid artery stenosis is the major cause of stroke, which can lead to disability and mortality. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) with carotid patch angioplasty is the most popular technique for reducing the risk of stroke. Patch material may be made from an autologous vein, bovine pericardium, or synthetic material including polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Dacron, polyurethane, and polyester. This is an update of a review that was first published in 1996 and was last updated in 2010.

Objectives

To assess the safety and efficacy of different types of patch materials used in carotid patch angioplasty. The primary hypothesis was that a synthetic material was associated with lower risk of patch rupture versus venous patches, but that venous patches were associated with lower risk of perioperative stroke and early or late infection, or both.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register (last searched 25 May 2020); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 4), in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (1966 to 25 May 2020); Embase (1980 to 25 May 2020); the Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings (1980 to 2019); the Web of Science Core Collection; ClinicalTrials.gov; and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) portal. We handsearched relevant journals and conference proceedings, checked reference lists, and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials (RCTs) comparing one type of carotid patch with another for CEA.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed eligibility, risk of bias, and trial quality; extracted data; and determined the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach. Outcomes, for example, perioperative ipsilateral stroke and long‐term ipsilateral stroke (at least one year), were collected and analysed.

Main results

We included 14 trials involving a total of 2278 CEAs with patch closure operations: seven trials compared vein closure with PTFE closure, five compared Dacron grafts with other synthetic materials, and two compared bovine pericardium with other synthetic materials. In most trials, a patient could be randomised twice and could have each carotid artery randomised to different treatment groups.

Synthetic patch compared with vein patch angioplasty Vein patch may have little to no difference in effect on perioperative ipsilateral stroke between synthetic versus vein materials, but the evidence is very uncertain (odds ratio (OR) 2.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 6.38; 5 studies, 797 participants; very low‐quality evidence). Vein patch may have little to no difference in effect on long‐term ipsilateral stroke between synthetic versus vein materials, but the evidence is very uncertain (OR 1.45, 95% CI 0.69 to 3.07; P = 0.33; 4 studies, 776 participants; very low‐quality evidence). Vein patch may increase pseudoaneurysm formation when compared with synthetic patch, but the evidence is very uncertain (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.49; 4 studies, 776 participants; very low‐quality evidence). However, the numbers involved were small.

Dacron patch compared with other synthetic patch angioplasty Dacron versus PTFE patch materials

PTFE patch may reduce the risk of perioperative ipsilateral stroke (OR 3.35, 95% CI 0.19 to 59.06; 2 studies, 400 participants; very low‐quality evidence). PTFE patch may reduce the risk of long‐term ipsilateral stroke (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.25 to 9.27; 1 study, 200 participants; very low‐quality evidence). Dacron may result in an increase in perioperative combined stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) (OR 4.41 95% CI 1.20 to 16.14; 1 study, 200 participants; low‐quality evidence) when compared with PTFE. Early arterial re‐stenosis or occlusion (within 30 days) was also higher for Dacron patches. During follow‐up for longer than one year, more 'any strokes' (OR 10.58, 95% CI 1.34 to 83.43; 2 studies, 304 participants; low‐quality evidence) and stroke/death (OR 6.06, 95% CI 1.31 to 28.07; 1 study, 200 participants; low‐quality evidence) were reported with Dacron patch closure, although numbers of outcome events were small. Dacron patch may increase the risk of re‐stenosis when compared with other synthetic materials (especially with PTFE), but the evidence is very uncertain (OR 3.73, 95% CI 0.71 to 19.65; 3 studies, 490 participants; low‐quality evidence).

Bovine pericardium patch compared with other synthetic patch angioplasty Bovine pericardium versus PTFE patch materials

Evidence suggests that bovine pericardium patch results in a reduction in long‐term ipsilateral stroke (OR 4.17, 95% CI 0.46 to 38.02; 1 study, 195 participants; low‐quality evidence). Bovine pericardial patch may reduce the risk of perioperative fatal stroke, death, and infection compared to synthetic material (OR 5.16, 95% CI 0.24 to 108.83; 2 studies, 290 participants; low‐quality evidence for PTFE, and low‐quality evidence for Dacron; OR 4.39, 95% CI 0.48 to 39.95; 2 studies, 290 participants; low‐quality evidence for PTFE, and low‐quality evidence for Dacron; OR 7.30, 95% CI 0.37 to 143.16; 1 study, 195 participants; low‐quality evidence, respectively), but the numbers of outcomes were small. The evidence is very uncertain about effects of the patch on infection outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

The number of outcome events is too small to allow conclusions, and more trial data are required to establish whether any differences do exist. Nevertheless, there is little to no difference in effect on perioperative and long‐term ipsilateral stroke between vein and any synthetic patch material. Some evidence indicates that other synthetic patches (e.g. PTFE) may be superior to Dacron grafts in terms of perioperative stroke and TIA rates, and both early and late arterial re‐stenosis and occlusion. Pseudoaneurysm formation may be more common after use of a vein patch than after use of a synthetic patch. Bovine pericardial patch, which is an acellular xenograft material, may reduce the risk of perioperative fatal stroke, death, and infection compared to other synthetic patches. Further large RCTs are required before definitive conclusions can be reached.

Keywords: Humans; Aneurysm, False; Aneurysm, False/epidemiology; Angioplasty; Angioplasty/methods; Bias; Bioprosthesis; Blood Vessel Prosthesis; Blood Vessel Prosthesis/adverse effects; Carotid Stenosis; Endarterectomy, Carotid; Endarterectomy, Carotid/classification; Endarterectomy, Carotid/methods; Endarterectomy, Carotid/mortality; Polyethylene Terephthalates; Polyethylene Terephthalates/adverse effects; Polytetrafluoroethylene; Polytetrafluoroethylene/adverse effects; Postoperative Complications; Postoperative Complications/epidemiology; Postoperative Complications/etiology; Postoperative Complications/mortality; Postoperative Complications/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Saphenous Vein; Stroke; Stroke/epidemiology; Stroke/etiology; Stroke/mortality; Stroke/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Patches of different types for carotid patch angioplasty

Question

What are the best types of patch materials for patients who undergo carotid patch angioplasty?

Background Carotid endarterectomy is an operation done to remove some diseased artery lining that has caused a stroke. Usually patients who need this operation are at risk of a stroke because of recent stroke symptoms or severe disease of the carotid artery. Inserting a patch at the end of the carotid operation appears to reduce the risk of further stroke and artery disease. These patches are made of synthetic material, the patient’s own vein, or other natural materials such as bovine pericardium. Vein patching is often used and is resistant to infection. However, abnormal swelling of the patch or patch rupture has been a matter of concern. Synthetic patch materials including Dacron and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) have high strength and may involve lower risk of patch rupture. However, synthetic materials may confer greater risk of infection. Bovine pericardium may carry lower risk for both infection and other complications. However the best choice of material for carotid patch angioplasty procedures is still uncertain. This review aims to assess whether one type of patch is better than another for clinical outcomes (such as stroke and death) and complications (such as patch rupture or infection).

Search date We searched for studies up to 25 May 2020. Study characteristics This review identified 14 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving 2278 carotid endarterectomies, which compared different patch materials: seven trials compared vein closure with PTFE closure, five compared Dacron grafts with other synthetic materials, and two compared bovine pericardium with other synthetic materials. Primary endpoints were postoperative and long‐term (during at least one year) stroke on the operated side. Secondary endpoints were any stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), death, artery narrowing or blockage, and other complications including artery rupture, cranial nerve palsy, wound infection or bleeding, and reoperation or abnormal swelling (pseudoaneurysm).

Key results The results of using different types of patch materials after carotid endarterectomy were as follows. • Vein patch versus synthetic material: there were no differences in the risk of stroke postoperatively or over the long term. The main concerns were that vein patches appeared to result in more abnormal swelling (pseudoaneurysm). Information on other complications was limited.

• Dacron versus other synthetic material: Dacron patches were associated with higher risk of combined perioperative stroke and TIA, early arterial re‐stenosis or occlusion, and any strokes at longer‐term follow‐up, although numbers of outcome events were small.

• Bovine pericardium patch versus other synthetic materials: there were no differences in any clinical outcomes or complications, although the numbers of outcome events were small. Information on other complications was limited.

Quality of the evidence Most evidence was of low or very low quality due to research methods and small numbers. No RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention, and most trials did not report their funding source. Most outcomes were downgraded for imprecision due to wide confidence intervals and low event rates.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Main comparison of synthetic patch versus vein patch angioplasty.

| Synthetic patch versus vein patch angioplasty for carotid endarterectomy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy, whether initial indication for endarterectomy was symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid disease Settings: in hospitals with carotid centres Intervention: synthetic patch angioplasty Comparison: vein patch angioplasty | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Vein patch | Synthetic patch | |||||

| Perioperative ipsilateral stroke (< 30 days) | PTFE | OR 1.82 (0.49 to 6.78) | 590 (4 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention All studies did not report funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 7 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 2.86 (0.29 to 27.92) | 207 (1 study) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,e | |||

| 10 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 2.05 (0.66 to 6.38) | 797 (5 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d,e | |||

| 8 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 | |||||

| Perioperative combined stroke and TIA (< 30 days) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Perioperative death from all causes (< 30 days) | PTFE | OR 0.62 (0.16 to 2.41) | 609 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention Most studies did not report funding sources except 1 study, which had high risk of bias due to funding sources from the manufacturer (Hayes 2001) Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 13 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 0.45 (0.10 to 2.03) | 673 (3 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,e,f,g | |||

| 15 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 | |||||

| Polyester | OR 0.35 (0.01 to 8.81) | 87 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,b | |||

| 22 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 0.52 (0.20 to 1.34) | 1369 (8 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d,e,f | |||

| 15 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term ipsilateral stroke | PTFE | OR 1.36 (0.47 to 3.88) | 500 (3 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention Most studies did not report funding sources except 1 study, which had high risk of bias due to funding sources from the manufacturer (Hayes 2001) Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 24 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 1.56 (0.54 to 4.50) | 276 (1 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,g | |||

| 43 per 1000 | 66 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 1.45 (0.69 to 3.07) | 776 (4 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d,g | |||

| 31 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term any stroke | PTFE | OR 1.62 (0.63 to 4.18) | 609 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ verylowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention Most studies did not report funding sources except 1 study, which had high risk of bias due to funding sources from the manufacturer (Hayes 2001) Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 23 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 1.31 (0.60 to 2.87) | 471 (2 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,f,g | |||

| 50 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 | |||||

| Polyester | OR 0.4 (0.07 to 2.18) | 87 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,b | |||

| 111 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 1.22 (0.70, 2.13) | 1167 (7 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d,f,g | |||

| 41 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term stroke or death | PTFE | OR 1.02 (0.57 to 1.82) | 449 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention Most studies did not report funding sources except 1 study, which had high risk of bias due to funding sources from the manufacturer (Hayes 2001) Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 121 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 1.07 (0.62 to 1.87) | 471 (2 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,f,g | |||

| 120 per 1000 | 130 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 1.05 (0.70, 1.56) | 920 (5 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,dc,f,g | |||

| 121 per 1000 | 125 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term pseudoaneurysm formation | PTFE | OR 0.09 (0.02 to 0.49) | 500 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention Most studies did not report funding sources except 1 study, which had high risk of bias due to funding sources from the manufacturer (Hayes 2001) |

|

| 56 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | Not estimable | 276 (1 study) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,g | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | 776 (4 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d,g | ||||

| 36 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not available; OR: odds ratio; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene; RCT: randomised controlled trial; TIA: transient ischaemic attack. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

| Long‐term: outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (≥ 1 year) including events during the first 30 days. | ||||||

aRisk of bias due torandomised trials did not blind surgeons and patients, and most studies did not report funding sources.

bImprecision was due to wide confidence intervals (low event rates).

cOne study had unclear risk for random sequence generation (AbuRahma 1996), and 2 studies did not report the method of allocation concealment (AbuRahma 1996; Gonzalez 1994).

dOne study did not report blinding of outcome assessment (Ricco 1996).

eOne study did not report blinding of outcome assessment with unclear risk for selection bias (Katz 1996).

fTwo studies did not report blinding of outcome assessment (Hayes 2001O'Hara 2002)

gOne study had high risk of bias due to funding sources from the manufacturer and did not report blinding of outcome assessment (Hayes 2001).

Summary of findings 2. Main comparison of Dacron patch versus other synthetic patch angioplasty.

| Dacron patch versus other synthetic patch angioplasty for carotid endarterectomy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy, whether the initial indication for endarterectomy was symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid disease Settings: in hospitals with carotid centres Intervention: Dacron patch angioplasty Comparison: other synthetic patch angioplasty | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Other synthetic material | Dacron patch | |||||

| Perioperative ipsilateral stroke (< 30 days) | PTFE | RR 3.35 (0.19 to 59.06) | 400 (2 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources and the number of patients lost to follow‐up |

|

| 10 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 | |||||

| Perioperative combined stroke and TIA (< 30 days) | PTFE | OR 4.41 (1.20 to 16.14) | 200 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,c | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources and the number of patients lost to follow‐up |

|

| 30 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 | |||||

| Perioperative death from all causes (< 30 days) | PTFE | OR 1.51 (0.25 to 9.07) | 400 (2 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 5 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 | |||||

| Bovine pericardium | OR 3.55 (0.14 to 89.42) | 95 (1 study) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,e | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 | |||||

| Polyurethane | OR 0.19 (0.01 to 4.11) | 104 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,b | |||

| 38 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 1.03 (0.30 to 3.57) | 599 (4 studies) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d,e | |||

| 10 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term ipsilateral stroke | PTFE | OR 1.52(0.25 to 9.27) | 200 (1 study) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 20 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term any stroke | PTFE | OR 16.12 (0.91 to 286.22) | 200 (1 study) | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 0 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 | |||||

| Polyurethane | OR 5.20 (0.24 to 110.95) | 104 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,b | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 10.58 (1.34 to 83.43) | 304 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,c | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term stroke or death | PTFE | OR 6.06 (1.31 to 28.07) | 200 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ lowa,c | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources and the number of patients lost to follow‐up |

|

| 20 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term pseudoaneurysm formation | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not available; OR: odds ratio; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; TIA: transient ischaemic attack. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

| Long‐term: outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (≥ 1 year) including events during the first 30 days. | ||||||

aRisk of bias due to randomised trials did not blind surgeons and patients, and most studies did not report funding sources.

bImprecision was due to wide confidence intervals (low event rates).

cOne study did not report the number of patients lost to follow‐up (AbuRahma 2002).

dOne study did not report the number of patients lost to follow‐up (AbuRahma 2007).

eOne study was at high risk of bias due to no random sequence generation and unclear allocation concealment, and did not report on blinding of outcome assessment (Marien 2002).

Summary of findings 3. Main comparison of bovine pericardium patch versus other synthetic patch angioplasty.

| Bovine pericardium patch versus other synthetic patch angioplasty for carotid endarterectomy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy, whether the initial indication for endarterectomy was symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid disease Settings: in hospitals with carotid centres Intervention: bovine pericardium patch angioplasty Comparison: other synthetic patch angioplasty | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Other synthetic material | Bovine pericardium patch | |||||

| Perioperative ipsilateral stroke (< 30 days) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Perioperative combined stroke and TIA (< 30 days) | PTFE | OR 4.17 (0.46 to 38.02) | 195 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ lowa,b,c | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 41 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 0.22 (0.01 to 4.76) | 95 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 1.18 (0.07 to 20.39) | 290 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | |||

| 28 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 | |||||

| Perioperative death from all causes (< 30 days) | PTFE | OR 5.16 (0.24 to 108.83) | 195 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ lowa,b,c | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 21 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Dacron | OR 3.55 (0.14 to 89.42) | 95 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | |||

| 23 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Total | OR 4.39 (0.48 to 39.95) | 290 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | |||

| 21 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term ipsilateral stroke | PTFE | OR 4.17 (0.46 to 38.02) | 195 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ lowa,b,c | None of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or patients due to the nature of the intervention None of these RCTs reported funding sources Most studies were downgraded due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals and low event rates) |

|

| 93 per 1000 | 31 per 1000 | |||||

| Long‐term any stroke | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Long‐term stroke or death | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Long‐term pseudoaneurysm formation | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not applicable; OR: odds ratio; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene; RCT: randomised controlled trial; TIA: transient ischaemic attack. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

| Long‐term; outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (≥ 1 year) including events during the first 30 days. | ||||||

aRisk of bias due to randomized trials did not blind surgeons and patients, and most studies did not report funding sources.

bImprecision due to wide confidence intervals (low event rates).

cOne study did not report blinding of outcome assessment (Stone 2014).

dOne study was at high risk of bias due to no random sequence generation and unclear allocation concealment, and did not report on blinding of outcome assessment (Marien 2002).

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke is one of the leading causes of mortality in the world. In the European population (GBD 2019), 1.4 million strokes occur each year (Truelsen 2006). In the UK, 150,000 first‐ever strokes occurred during the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project from 1981 to 1986 (Bamford 1988). Stroke is the second leading cause of death (Nichols 2012). Eighty‐five per cent of strokes are ischaemic (Bamford 1988). The most common cause of ischaemic stroke is stenosis or occlusion of the atherosclerotic internal carotid artery and/or middle cerebral artery. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) has been shown in large, well‐conducted randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with recently symptomatic, severe stenosis (> 70%) of the extracranial internal carotid artery (ECST 1991; ECST 1998; NASCET 1991; NASCET 1998). Some evidence suggests that CEA may be beneficial for some categories of asymptomatic patients (ACAS 1995; ACST‐1 2010). A multi‐centre RCT has shown that immediate CEA confers a 4.6% absolute risk reduction compared with medical therapy in asymptomatic patients (ACST‐1 2010).

Description of the intervention

Carotid endarterectomy is a surgical procedure undertaken to correct internal carotid stenosis from inside the carotid artery wall. In a standard endarterectomy, the most popular technique, carotid plaque is removed by a longitudinal arteriotomy. What is less clear at present is whether different surgical techniques affect the outcome, although increasing evidence suggests that carotid patch angioplasty is superior to primary closure in reducing the risk of re‐stenosis and improving both short‐ and long‐term clinical outcomes (Counsell 1998; Rerkasem 2010). Consequently, many vascular surgeons use carotid patching either routinely or selectively. However, considerable debate over the choice of patch material is ongoing.

How the intervention might work

Vein patching (with vein usually harvested from the saphenous vein and sometimes from the jugular vein) is favoured by some on the basis that a non‐randomised comparison suggested it was better for preventing stroke or death (Fode 1986). Vein patching also offers the advantages of being easily available and easy to handle, with possibly greater resistance to infection. Synthetic material such as Dacron or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is favoured by others, who feel that it offers lower risk of patch rupture ‐ Murie 1994 ‐ and aneurysmal dilatation ‐ Gonzalez 1994 ‐ and that it spares the morbidity associated with saphenous vein harvesting and leaves the vein intact, which may be required for coronary bypass grafting at a later date. It is also possible that one type of synthetic material is better than another. For example, AbuRahma 2002 found that PTFE resulted in fewer perioperative carotid thromboses and strokes than Dacron. Finally, biomaterials such as bovine pericardium are now in common use, and some evidence suggests that bovine pericardium provides faster haemostasis time than PTFE without differences in perioperative or late neurological events or re‐stenosis (Kim 2001; Stone 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Multiple RCTs have compared outcomes between different materials for carotid patch after endarterectomy. The most reliable evidence on the best material to use comes from these trials, and it is important to synthesise the results so we can identify the best patch material.

Objectives

To assess the safety and efficacy of different types of patch materials used in carotid patch angioplasty. The primary hypothesis was that a synthetic material was associated with lower risk of patch rupture versus venous patches, but that venous patches were associated with lower risk of perioperative stroke and early or late infection, or both.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought to identify all unconfounded randomised trials in which one type of carotid patch was compared to another. We also included quasi‐randomised trials in which allocation to different treatment regimens was not adequately concealed (e.g. allocation by alternation, date of birth, hospital number, day of the week, or by using an open random number list).

Types of participants

We considered trials that included any type of patient undergoing carotid endarterectomy as eligible, whether the initial indication for endarterectomy was symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid disease.

Types of interventions

We sought to identify all trials comparing one type of patch material with another in CEA. Currently available materials include saphenous vein (harvested from either the ankle or the groin), Dacron, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) polyester or polyurethane, and bovine pericardium.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Perioperative ipsilateral stroke (< 30 days)

Long‐term ipsilateral stroke (outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (at least one year) including events during the first 30 days)

Ipsilateral stroke describes insufficient blood flow to the cerebral hemisphere secondary to same side occlusion or severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery.

Secondary outcomes

Perioperative clinical outcome including any stroke, combined stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA), death from all causes, fatal stroke, stroke, or death (< 30 days)

Perioperative complications (< 30 days) including arterial rupture, cranial nerve palsy, wound infection, wound haemorrhage, early re‐stenosis or arterial occlusion, complication requiring further operation

Long‐term clinical outcome including any stroke, combined stroke and TIA, death from all causes, fatal stroke, stroke, or death (outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (at least one year) including events during the first 30 days)

Long‐term complications including infection of the endarterectomy site, arterial occlusion/re‐stenosis > 50%, pseudoaneurysm formation (outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (at least one year) including events during the first 30 days)

Search methods for identification of studies

See the methods for the Cochrane Stroke Group Specialised register. We did not use any language restrictions in the searches; we arranged translation of all possibly relevant publications when necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group's Trials Register, which was last searched by the Cochrane Stroke Group's Information Specialist on 25 May 2020. We also updated electronic searches and handsearched additional issues of relevant journals as follows.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 5), in the Cochrane Library (searched 25 May 2020); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 25 May 2020); Embase Ovid (1980 to 25 May 2020); the Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings (1980 to 25 May 2020; searched using the terms "carotid" and ("trial* or random*")); and the Web of Science Core Collection (last searched 25 May 2020).

Searching other resources

We searched the following ongoing trials in the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 25 May 2020) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 25 May 2020) (Higgins 2016).

We handsearched the following journals including conference supplements.

Annals of Surgery (1981 to 25 May 2020).

Annals of Vascular Surgery (1994 to 25 May 2020).

Cardiovascular Surgery (now Vascular) (1994 to 25 May 2020).

European Journal of Vascular Surgery (now European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery) (1987 to 25 May 2020).

Journal of Vascular Surgery (1994 to 25 May 2020).

Stroke (1994 to 25 25 May 2020).

We reviewed the reference lists of all relevant studies. We contacted experts in the field to identify further published and unpublished studies.

For the previous version of the review, we handsearched the following journals including conference supplements.

American Journal of Surgery (1994 to 25 May 2020).

British Journal of Surgery (1985 to 25 May 2020).

World Journal of Surgery (1978 to 25 May 2020).

We handsearched abstracts of the following meetings for the years 1995 to 25 May 2020.

AGM of the Vascular Surgical Society (UK).

AGM of the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland.

American Heart Association Stroke Conference.

Annual Meeting of the Society for Vascular Surgery (USA).

The European Stroke Conference.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (SO, TB, and KR) independently read the titles and abstracts of records obtained from the searches, excluded obviously irrelevant studies, and selected those trials that met the inclusion criteria. We obtained the full‐text articles of potentially relevant studies. All three review authors (SO, TB, and KR) screened all documents and independently extracted data, including details of methods, participants, setting, context, interventions, outcomes, results, publications, and investigators. We resolved all disagreements through discussion and performed meta‐analysis using RevMan 5.4 (RevMan 2020).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently reviewed and assessed all trials (so each trial received two assessments) and double‐checked all data extracted. We recorded the following details: randomisation method, blinding of clinical and Doppler assessments, whether outcomes were reported for all participants originally randomised to each group irrespective of whether they received the operation they were allocated to or whether the participant was excluded after randomisation, and the number of participants lost to follow‐up. We sought data on the number of outcome events for all participants originally randomised to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis. For the 14 included trials, we also extracted details about participants included in the trials, inclusion and exclusion criteria, individual patient data and participant characteristics (age, gender, indication for surgery), type of carotid patching, comparability of treatment and control groups for important prognostic factors, type of patch, type of anaesthetic, use of shunts, and use of antiplatelet therapy during follow‐up. We merged data into a single composite database and gave detailed consideration to the definition for each variable used in the original trials. Much of the above data were not available from the publications, and so we sought further information from triallists in all cases; however, we did not always receive a response. We resolved all disagreements through discussion with other review authors (BS, DPH).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SO, BS) independently assessed risk of bias (high risk, low risk, unclear risk) using the Cochrane ’Risk of bias’ tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and reported details in the ’Risk of bias’ tables (Higgins 2011). We resolved all disagreements through discussion. Risks of bias included random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), and incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Measures of treatment effect

We used RevMan 5.4 to carry out statistical analyses to determine the estimates of effect and to describe the magnitude of the intervention effect in terms of how different outcome data were between the two groups (RevMan 2020). Types of intervention effects include ratio effect measures that compare the odds of an event between two groups (odd ratios (ORs)); every estimate is expressed with a measure of that uncertainty, including a confidence interval (CI).

For dichotomous variables, we calculated proportional risk reductions based on weighted estimate of the OR using the Peto method (APT 1994). We calculated absolute risk reductions from the crude risks of each outcome in all trials combined with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

All trials randomised the artery rather than the participant, and all included participants who had bilateral carotid endarterectomies. Therefore, it was possible for a single participant to have both types of patch material. For these participants, it would be difficult to relate death or stroke to one particular procedure. In the previous version of this review (Rerkasem 2010), for trials in which it was possible for a patient to have both procedures, death and any stroke were analysed only in those who had unilateral procedures or the same procedure to both arteries. When we could not obtain data from the authors of relevant trials, we excluded the whole trial from the analysis (Lord 1989). Of the six studies published since 1995, two ensured that participants undergoing more than one operation were assigned the same closure method (Hayes 2001; O'Hara 2002), whereas four did not (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; Katz 1996; Stone 2014). However, most participants who undergo more than one operation will have a period of at least 30 days between procedures; therefore, short‐term results are likely to be reliable regardless of how data are analysed. Only one of the later studies reported long‐term follow‐up (AbuRahma 1996), but the number of bilateral operations was small compared with the total number of operations carried out, and this was unlikely to bias the results significantly. Therefore, we included this trial, but this should be borne in mind when results are interpreted.

A separate analysis of only strokes ipsilateral to the operated artery was also performed for each artery. However, the total number of strokes was very similar to the number of ipsilateral strokes because in the majority of studies, all strokes were ipsilateral. Arterial complications, such as occlusion, haemorrhage from the endarterectomy site, re‐stenosis, infection at the operation site, or pseudoaneurysm formation, were analysed for all arteries rather than for participants. Analyses based on arteries assumed that for participants who had bilateral endarterectomies, outcome events in each carotid artery were independent.

Dealing with missing data

When data were missing, we contacted the corresponding author or co‐author through the address given in the publication. If this information was not available, we searched for the study group via the Internet and contacted group members for missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between study results using the I² statistic (Higgins 2020). This examined the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. Thresholds for interpretation of the I² statistic can be misleading, in that the importance of inconsistency depends on several factors. A rough guide to interpretation in the context of meta‐analyses of randomised trials is as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We performed an extensive literature search, and we are confident that we have identified all major relevant trials. We also contacted experts in this field. We searched for trials published in all languages, and we arranged translation of all possibly relevant publications when required. In addition, we searched all relevant ongoing clinical trials from ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) portal, and we handsearched relevant journals and reference lists. We had planned to compare study protocols with final study reports to evaluate selective reporting of outcomes. We used funnel plots to assess publication bias because more than 10 studies were included (Sterne 2011). However, none of the trials reported limits outside the 95% CI.

Data synthesis

We included in the combined analysis all participants included in the final analysis of results of the original trials, using the Mantel Haenszel method. We used the fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis in the absence of clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity. If the I² statistic was high, we also applied a random‐effects model to see whether the conclusions differed, and we noted any differences (Higgins 2003). We performed all analyses of the effects of surgery on an intention‐to‐treat basis according to randomised treatment allocation. We assessed the significance of differences between treatment groups by the log‐rank test stratified by study. We tested the significance of differences in baseline data between trials and treatment groups using the Chi² test or Student’s t‐test, as appropriate. We used Cochrane RevMan 5.4 software (RevMan 2020), as well as SPSS for Windows version 26.0, for all analyses (SPSS 2019 [Computer program]). If pooling was not possible or appropriate, we had planned to present a narrative summary (Deeks 2011).

Pooling of individual patient data

We obtained original individual patient data for the 14 included trials. We merged data on presenting events, baseline clinical data, operative details, surgical and anaesthetic techniques, perioperative events, and long‐term follow‐up into a single composite database. We gave detailed consideration to the definition for each variable used in the original trials. When definitions were identical, we merged comparable data. When possible, we resolved differences in definitions of variables between studies by reconstructing definitions to achieve comparability.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to explore heterogeneity by conducting subgroup analyses. We specified the following subgroup analyses.

Age (younger than 65 years old versus 65 to 74 years old versus 75+ years old).

Gender (men versus women).

Diabetes versus no diabetes.

Hypertension versus no hypertension.

Previous myocardial infarction or angina versus no coronary artery disease.

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) versus no PAD.

Current smoker versus non‐smoker.

Asymptomatic disease versus symptomatic disease of carotid stenosis.

Contralateral carotid stenosis versus unilateral carotid stenosis.

Contralateral carotid occlusion versus no occlusion.

Preoperative antiplatelet therapy versus no antiplatelet therapy.

Intraoperative shunt versus no shunt.

Irregular or ulcerated symptomatic carotid plaque versus smooth plaque on the pre‐randomisation angiogram.

We planned to use an established method for subgroup analyses (Deeks 2001). In the future, we will fulfil planned subgroup analyses when more studies are included in a single analysis, all with sufficient information to reveal the subgroups.

Analyses were stratified by patch type. Tests for overall effect and subgroup differences by patch type included synthetic material versus vein, Dacron versus other synthetic material, and bovine pericardium versus synthetic material. Each subgroup was analysed for perioperative events (< 30 days) and events during long‐term follow‐up (at least one year), including events during the first 30 days. So, a total of six groups of data and analyses were examined. All outcomes from 12 RCTs were collected directly from two‐arm comparisons (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht-Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014). Only two included RCTs have multiple arms. Multiple‐arm analysis compared different types of patches and primary closure of the endarterectomy site (AbuRahma 1996; Lord 1989). One RCT used three primary comparisons between non‐patch, PTFE, and saphenous vein (AbuRahma 1996). However, individual comparison probabilities were set at P = 0.0167 on the basis of the Bonferroni method for correction for multiple comparisons. Thus, outcomes of these studies were not extracted from the subgroup analysis. We did not investigate potential effect modifiers via subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake the following sensitivity analyses to explore effects of methodological features when decisions for the process undertaken in this systematic review were somewhat arbitrary or unclear.

Allocation concealment: we planned to repeat analysis and to exclude high risk of selection bias trials.

Blinding of outcome assessment: we planned to repeat data analysis and to exclude high risk of detection bias trials.

Incomplete outcome data: we planned to repeat data analysis, to identify the method of dealing with missing outcome data, and to exclude high risk of attrition bias trials.

Selective reporting: we planned to repeat data analysis, to find evidence of published findings on all study outcomes, and to exclude high risk of reporting bias trials.

Other bias: publication type: we planned to exclude trials with the absence of peer‐review.

Given that foreknowledge of treatment allocation might lead to biased treatment allocation and exaggerated treatment effects (Schulz 1995), we performed in the first version of this review separate sensitivity analyses of those trials in which allocation concealment was secure and those in which it was less secure. However, we found no significant differences between trials with different allocation techniques, and no studies in this later review were quasi‐randomised; therefore, we did not carry out sensitivity analyses for this version of the review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created three Summary of findings tables for the main comparisons with GRADE Profiler 3.6 (GRADEpro 2015), which imports data from RevMan 5 (RevMan 2020). This table presents the results and the quality of the evidence of the main outcomes, using the GRADE system, which classifies the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low, and very low (Schünemann 2011). We included seven important outcomes including major outcome: 1) perioperative combined stroke and TIA (< 30 days); 2) perioperative death from all causes (< 30 days); 3) perioperative fatal stroke (< 30 days); 4) longterm any stroke; 5) longterm stroke or death, complications; 6) perioperative wound infection (< 30 days); and 7) longterm pseudoaneurysm formation.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

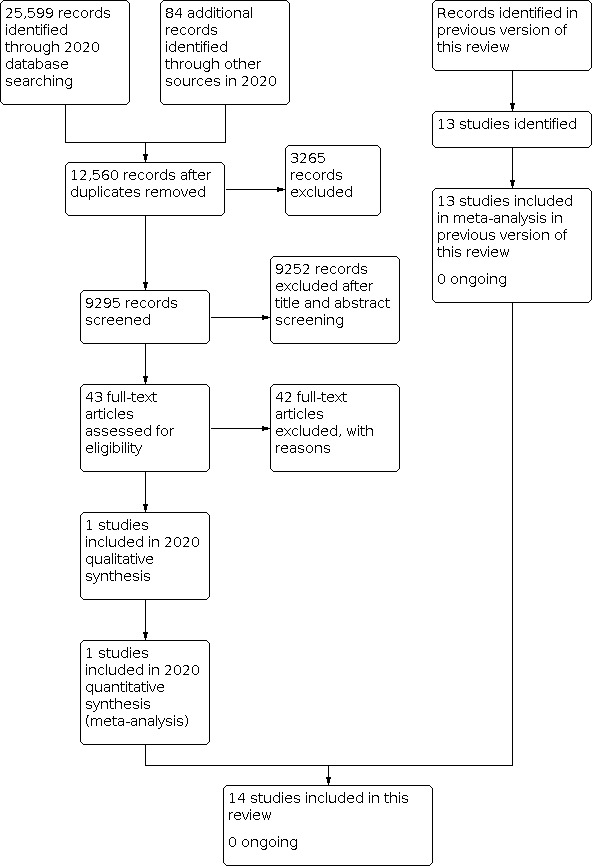

We identified 25,599 records through database searching and 84 additional records from other sources in 2020. These searches yielded a total of 12,560 records after de‐duplication; only 43 full‐text articles remained after title and abstract screening. Finally, upon screening the full text, we excluded all 42 full‐text articles because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. We included one new study in this update of the review (Stone 2014). The review now includes 14 RCTs of different types of patches for carotid patch angioplasty; we found no ongoing studies. See Figure 1. It is important to note that the number of studies identified in the search process was consistently smaller than the number in the previous (2010) version. This might be due to the application of new search methods (i.e. highly sensitive search strategies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The previous version of this review included 13 trials involving a total of 2083 operations available for analysis (Rerkasem 2010). Since that time, many prospective and retrospective studies have examined different patch types. However, only one additional RCT of sufficient standard had been performed, and this has been included in the current review. See Characteristics of included studies.

The addition of the new trial comparing synthetic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) with bovine pericardium patching increased the total number of trials to 14, with 2278 operations available for analysis (Figure 1) (Stone 2014). Seven trials compared vein closure with PTFE closure, five compared Dacron grafts with other synthetic materials, and two compared bovine pericardium with other synthetic materials. Two trials compared vein to PTFE and polyester patch (Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008), one compared Dacron to PTFE patching (AbuRahma 2007), and the rest compared Dacron with other synthetic materials, namely, polyurethane patch ‐ Albrecht‐Fruh 1998 ‐ and bovine pericardium ‐ Marien 2002. One pre‐1995 and one post‐1995 trial had three arms: saphenous vein patching, PTFE patching, and primary closure (AbuRahma 1996; Lord 1989). Only results from the vein patching and PTFE patching groups are included in this review. Four trials compared saphenous vein harvested from the groin with synthetic patches (Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Ricco 1996). Two trials used saphenous vein from the ankle (Gonzalez 1994; Meerwaldt 2008), one trial alternately used vein from the jugular vein and from the saphenous vein at the ankle (AbuRahma 1996), and one trial used vein from the external jugular vein (Grego 2003). One trial did not specify a site (O'Hara 2002). In all trials, operations were performed under general anaesthetic, and most were also performed with shunting. All patients received antiplatelet therapy perioperatively. One study used heparin reversal at completion of surgery in 30% of synthetic closure patients but not in vein closure patients (Katz 1996). One used heparin reversal in all patients (Gonzalez 1994), five used reversal in none (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Ricco 1996), and data were unavailable for six cases (Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Hayes 2001; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002).

Early (within 30 days) postoperative arterial occlusion or carotid thrombosis was assessed by duplex sonography or angiography in 11 trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014), and assessment was based on symptoms in only two trials (Katz 1996; Lord 1989). During long‐term follow‐up, re‐stenosis of the arteries was assessed by Duplex ultrasound in 11 trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014), and assessment was done by Doppler ultrasound and intravenous digital subtraction angiography in another (Gonzalez 1994). Two trials provided only data on ipsilateral strokes, and it is unclear whether any other strokes occurred during follow‐up (Lord 1989; Ricco 1996).

In the pre‐2002 review, the average age of patients involved in the trials was about 67.5 years, 60% to 80% were men, and less than 36% of operations were performed for asymptomatic carotid disease. In the studies conducted since 2002, the average age of patients was 67.65 years, 50% to 80% were men, and 47% of the operations were performed for asymptomatic carotid disease (excluding one study that intended to operate only on symptomatic patients (Meerwaldt 2008)). One trial included only patients with narrow internal carotid arteries (< 5 mm external diameter) and excluded patients with recurrent carotid stenosis (Ricco 1996), whereas two trials excluded patients with internal carotid diameters smaller than 4 mm (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002). All but two trials excluded patients undergoing either recurrent carotid endarterectomy or combined coronary and carotid surgery at the same time (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996), one excluded no patients at all (Gonzalez 1994), and one did not provide information on exclusions (Lord 1989). In all but four trials, treatment groups were comparable for important prognostic factors. Two trials included more men in the synthetic group than in the vein patch group (Grego 2003; O'Hara 2002). Another two trials reported different stroke rates between the two groups (Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Three RCTs of carotid endarterectomy did not meet our inclusion criteria. Our outcomes, which were decided at the time of setting up the review, were clinical outcomes that do not include non‐relevant outcomes such as microemboli, number of oxidized cellulose packets, etc. So, our review addressed the potential for carotid patch angioplasty with different types of patch materials to prevent a particular clinical outcome (Mckenzie 2020). The first trial exclusion was based on lack of clinical data involving 74 patients randomised between Dacron, PTFE, and venous patch by an open random number list. The main outcomes were number of packets of oxidized cellulose used and elapsed time between removal of carotid‐occluding clamps and completion of the procedure (Carney 1987). The second trial outcome looked at microemboli perioperatively, which was not related to a clinical outcome nor to the efficacy of carotid patch material angioplasty (Chyatte 1996). The last excluded trial recorded bleeding time and microemboli perioperatively (Ruckert 2000).

Risk of bias in included studies

Included trials had several significant flaws (Figure 2; Figure 3). However, trials published after 2002 were generally of better quality than those published before that time. Up to 2002, 6 out of 10 studies reported a method of randomisation (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; Hayes 2001; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996); after 2002, all 3 trials reported a method of randomisation (AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008). Adequately concealed allocation was performed in 7 of the 10 pre‐2002 trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; Gonzalez 1994; Hayes 2001; Lord 1989; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996), and after 2002, all four trials had adequately concealed allocation (AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008; Stone 2014). Eight trials attempted to perform blinded follow‐up (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996). One trial did not blind outcome assessments and followed patients only until hospital discharge (Lord 1989). As mentioned previously, one of the main flaws in all trials was that a patient undergoing bilateral carotid endarterectomy could be randomised twice and have each carotid artery randomised to different treatment groups. In these trials, it is unclear from published reports how many patients in each group underwent bilateral procedures that were different in each artery, and whether any deaths or strokes occurred in these patients. True intention‐to‐treat analyses were possible in seven trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Gonzalez 1994; Hayes 2001; Lord 1989; O'Hara 2002).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Eight included studies were RCTs with adequate generation of a randomised sequence, and we assessed them to be at low risk of bias (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014). Five RCTs did not report the random sequence generation method, and we assessed them to be at unclear risk of bias (AbuRahma 1996; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Meerwaldt 2008). One included study was at high risk of bias due to sequence generation that was based on the last number of the patient's medical record (Marien 2002). Allocation concealment was adequate in eight trials, which we assessed to be at low risk of bias (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014). In six trials, it is not clear whether allocation to groups was adequately concealed; we assessed these trials to be at unclear risk of bias (AbuRahma 1996; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002).

Blinding

Because of the nature of the intervention, none of these RCTs could be blinded for surgeons or participants (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014). Five studies made use of an independent external review process for all outcomes (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008), but the clinical data presented for review were derived from the unblinded assessment discussed above and may, in theory, have been subject to bias. We assessed performance bias to be at high risk of bias in all 14 RCTs (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014), and we assessed detection bias to be at unclear risk in nine RCTs, which did not address blinding of outcome assessment (AbuRahma 1996; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014).

Incomplete outcome data

Few participants were lost to follow‐up in any of these studies. The design features of the 14 RCTs are summarised in Characteristics of included studies. Only two included trials did not report follow‐up patient data and cross‐over data between different types of arm patches (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007). We assessed attrition bias to be at unclear risk of bias for both these trials (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007), and we assessed it to be at low risk of bias for the other trials (AbuRahma 1996; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014).

Selective reporting

Study authors published findings on all study outcomes. This was entirely appropriate and is very unlikely to have introduced any bias into the results. We assessed selective reporting to be at low risk of bias in all included RCTs (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014). Data for analysis in this review were based on all study outcomes, and all results are included in the analysis. These data were not a subset of the original variables recorded.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged other potential sources of bias to be of low risk in all RCTs (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996; Stone 2014).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

We included in this review data from 14 trials involving 2278 operations. The results presented may differ from those in the published reports when we have obtained additional information from study authors. There was no statistical heterogeneity in any of the analyses except outcome of perioperative ipsilateral stroke, any stroke, and long‐term death; arterial occlusion between Dacron and other synthetic patch (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.5), and outcome of perioperative combined stroke and TIA, complication requiring further operation, and wound haemorrhage between bovine and other synthetic patch (Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.6; Analysis 3.8).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 1: Ipsilateral stroke

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 2: Any stroke

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Events during long‐term follow‐up (≥ 1 year) including events during first 30 days: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 3: Death

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Events during long‐term follow‐up (≥ 1 year) including events during first 30 days: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 5: Arterial occlusion/re‐stenosis > 50%

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 3: Combined stroke and TIA

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 6: Complication requiring further operation

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 8: Wound haemorrhage

Operative details

Duration of operation

The duration of the operation was not analysed statistically because evidence shows that durations were not normally distributed. Synthetic patching was associated with significantly longer operation times than vein patching in one trial: 128.0 ± 4.1 minutes versus 112.8 ± 3.5 minutes (P < 0.05) (Gonzalez 1994). However, synthetic patching was observed to have longer operation times versus vein patching with no statistically significant differences in two trials: 100 ± 21 minutes versus 93 ± 25 minutes (P = 0.1) (Meerwaldt 2008), and 105 minutes versus 89 minutes (P > 0.05) (Ricco 1996). In contrast, two other trials found vein patching was observed to have longer operation times versus either PTFE or Dacron patching, but there was no statistically significant difference in the two trials: mean times 126 ± 27 minutes versus 123 ± 28 minutes (P > 0.05) (AbuRahma 1996), and median times 105 minutes (95% confidence interval (CI) 102 to 115) versus 103 minutes (95% CI 102 to 114) (P = 0.71) (Hayes 2001).

In the first two cases, this difference was due to longer haemostasis times with PTFE. However, the difference in the second pair of trials was explained by the longer time required to harvest vein from the groin or neck. The trial that was excluded because of lack of clinical data reported that time from release of the clamps to completion of the operation was longer with PTFE patches (53 minutes) compared with both vein patching (41 minutes) and Dacron patching (45 minutes) because of excessive bleeding (Carney 1987). The trials comparing PTFE with Dacron patching found no significant differences in operation time except in two trials: mean times 119 ± 26 minutes versus 113 ± 22 minutes (P = 0.81) (AbuRahma 2002), and mean times 97.4 ± 3.7 minutes versus 95.9 ± 18.7 minutes (P = 0.61) (AbuRahma 2007). For haemostasis time, PTFE patching was associated with significantly longer haemostasis time than Dacron patching in two trials: mean times 14.4 ± 4.5 minutes versus 3.4 ± 3.8 minutes (P < 0.001) (AbuRahma 2002), and mean times 5.17 ± 5.2 minutes versus 3.73 ± 2.7 minutes (P = 0.01) (AbuRahma 2007). One new trial comparing bovine pericardium patch with PTFE found a non‐significantly longer operation time but significantly shorter haemostasis time (P < 0.0273) in patients patched with bovine pericardium than in those patched with PTFE (Stone 2014). In addition, suture line bleeding was significantly less (P < 0.001) among patients patched with bovine pericardium than among those patched with Dacron (Marien 2002). Five trials did not provide adequate data on operation time (Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002).

1. Perioperative outcomes (outcomes within 30 days of operation)

1.1. Clinical outcomes

1.1.1. Ipsilateral stroke

Vein versus synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for rates of ipsilateral stroke between different patch types (odds ratio (OR) 2.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 6.38; P = 0.21) (Analysis 1.1). The absolute risks of perioperative stroke (1.8%, 25/1122) were very low. The functional outcome of stroke, such as severity of neurological impairment and disability, was not assessed in any trials. The small number of events makes it unlikely that any differences in effect on outcomes between PTFE patching and vein patching would have been detected even if present.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 1: Ipsilateral stroke

Dacron versus other synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for rates of ipsilateral stroke between different patch types (OR 3.35, 95% CI 0.19 to 59.06; P = 0.91) (Analysis 2.1).

Bovine pericardial versus other synthetic material

No trial data were provided for this comparison.

1.1.2. Any stroke

Vein versus synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for rates of any stroke between different patch types (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.39; P = 0.7) (Analysis 1.2). All strokes were ipsilateral, but in two trials, other types of stroke were not recorded. The functional outcome of stroke, such as severity of neurological impairment and disability, was not assessed in any trials.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 2: Any stroke

Dacron versus other synthetic material

Seven strokes occurred in the Dacron group compared with one in the other synthetic material group (OR 2.65, 95% CI 0.06 to 111.53; P = 0.61). There was little effect on any stroke between different patch types, but the evidence is very uncertain (Analysis 2.2).

Bovine pericardial versus other synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for risk of ipsilateral stroke (OR 1.50, 95% CI 0.29 to 7.79; P = 0.63) with bovine pericardium compared with the other synthetic material (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 1: Any stroke

1.1.3. Death from all causes

Vein versus synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for rates of death between different patch types (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.34; P = 0.18) (Analysis 1.3). All absolute risks of death (1.0%, 14/1122) were very low. The small number of events makes it unlikely that any differences between PTFE patching and vein patching would have been detected even if present.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 3: Death from all causes

Dacron versus other synthetic material

Three deaths were reported in the Dacron‐patched group and three in the other synthetic material group (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.30 to 3.57; P = 0.96) (Analysis 2.4). There was no effect on death from all causes between different patch types, but the evidence is very uncertain.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 4: Death from all causes

Bovine pericardial versus other synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for risk of death (OR 4.39, 95% CI 0.48 to 39.95; P = 0.19) when bovine pericardium was compared with the other synthetic material (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 4: Death from all causes

1.1.4. Fatal stroke

Vein versus synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for rates of fatal stroke between different patch types (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.66; P = 0.16) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 4: Fatal stroke

Dacron versus other synthetic material

No trial data were reported for this comparison.

Bovine pericardial versus other synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for risk of fatal stroke (OR 5.16, 95% CI 0.24 to 108.83; P = 0.29) when bovine pericardium was compared with the other synthetic material (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 2: Fatal stroke

1.1.5. Combined stroke and death

Vein versus synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for rates of combined stroke and death between different patch types (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.66; P = 0.57) (Analysis 1.5). All absolute risks of combined stroke and death (2.4%, 27/1122) were very low. The small number of events makes it unlikely that any differences between PTFE patching and vein patching would have been detected even if present.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 5: Stroke or death

Dacron versus other synthetic material

No trial data were provided for this comparison.

Bovine pericardial versus other synthetic material

No trial data were provided for this comparison.

1.1.6. Combined stroke and TIA

Vein versus synthetic material

No trial data were provided for this comparison.

Dacron versus other synthetic material

Dacron may result in an increase in perioperative combined strokes and transient ischaemic attacks (OR 4.41, 95% CI 1.20 to 16.14; P = 0.03) when compared with PTFE (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 3: Combined stroke and TIA

Bovine pericardial versus other synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for perioperative combined stroke and transient ischaemic attacks (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.07 to 20.39; P = 0.91) when bovine pericardium was compared with another synthetic material (Analysis 3.3).

1.2. Perioperative complications

1.2.1. Cranial nerve palsy

Vein versus synthetic material

Cranial nerve palsy occurred in 3% of cases (19/630). The evidence is very uncertain in that it was more common in neither group and confidence intervals were wide (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.71; P = 0.67) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 7: Cranial nerve palsy

Dacron versus PTFE

No cranial nerve palsies were reported.

Bovine pericardium versus other synthetic material

No cranial nerve palsies were reported.

1.2.2. Wound infection

Vein versus synthetic material

Wound infection was observed to be more common in the vein group compared to the synthetic patch group, but the evidence is very uncertain (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.23; P = 0.11) (Analysis 1.8). This was due to increased risk of groin wound infection, for which patients undergoing synthetic patching would not be at risk. However, no patch infections during the perioperative period were reported.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 8: Wound infection

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

No wound infections were reported.

Bovine pericardium versus other synthetic material

Wound infection was reported in 3% of cases (3/97) in the synthetic material group. No wound infections were reported in the bovine pericardium patch group. Wound infection was observed to be more common in the other synthetic material group compared to the bovine pericardium patch group (OR 7.30, 95% CI 0.37 to 143.16; P = 0.19) (Analysis 3.5). Bovine pericardial patch is an acellular xenograft material that may reduce the risk of infection compared to synthetic material.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Perioperative events: bovine versus other synthetic (< 30 days), Outcome 5: Wound infection

1.2.3. Complications requiring further reoperation

Vein versus synthetic material

Complications requiring further reoperation for any reason occurred in 2.6% (33/1263) of cases, and there was no effect on complications requiring further reoperation for any reason in the vein and synthetic patch groups, but the evidence is very uncertain (OR 1.72, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.47; P = 0.13) (Analysis 1.9). Complications requiring further reoperation were for patch rupture (one in the PTFE group, and two in the vein group) or wound haemorrhage (2.44%, 33/1350). One of the vein ruptures involved saphenous vein harvested from the groin and another from the ankle (Analysis 1.11). Two of the three patch ruptures were fatal, one in each group. The evidence is very uncertain for differences in wound haematoma between vein and synthetic patch groups (OR 1.63, 95% CI 0.81 to 3.28; P = 0.2).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 9: Complication requiring further operation

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 11: Wound haemorrhage

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

The evidence is very uncertain for complications requiring further reoperation between Dacron and other synthetic patches (OR 5.43, 95% CI 0.92 to 31.90; P = 0.06). Eight patients required reoperation: seven in the Dacron group, and one in the other synthetic patch (PTFE) group. All re‐explorations were for suspected or proven carotid thrombosis/occlusion in seven cases, and one case was due to wound haematoma (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 5: Complication requiring further operation

Bovine pericardium versus other synthetic material

The evidence is very uncertain for the reoperation rate (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.08 to 6.38; P = 0.75). Complications requiring further reoperation were observed in 2.1% (3/141) of cases in the synthetic material group and in 4% (6/149) of cases in the bovine pericardium patch group. Re‐explorations were performed for wound haematoma in eight cases, and for proven carotid thrombosis/occlusion in one case (Analysis 3.6). Longer haemostasis time was reported for PTFE patching (4.9 minutes) versus bovine pericardial patching (3.09 minutes) (P = 0.027) (Stone 2014), and intraoperative suture line bleeding was less in the bovine pericardium group compared to the Dacron group (P < 0.001). In addition, total intraoperative suture line bleeding (Net (± standard error of the mean (SEM)) sponge weight) was 6.25 g and 16.34 g in the bovine pericardium group versus the Dacron group, respectively (P < 0.001) (Marien 2002).

1.2.4. Arterial occlusion

Vein versus synthetic material

The absolute risk of arterial occlusion was 0.7% (8/1155). Vein patch has little effect on arterial occlusion, but evidence of differences between vein and synthetic material is very uncertain (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.60 to 7.78; P = 0.24) (Analysis 1.10). Five of seven studies reporting rates of arterial occlusion did so based upon perioperative duplex ultrasound, whereas two reported only symptomatic occlusions.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 10: Arterial occlusion

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

Data show little effect on risk of arterial occlusion, but evidence of differences between Dacron and PTFE groups (OR 11.58, 95% CI 0.63 to 212.19; P = 0.1) is very uncertain (Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.