Abstract

Introduction

Free flap lower extremity repair is associated with a high complication rate (>31%); higher rates are observed in more severe patients. In cases requiring prior systemic/local stabilization, delayed repair increases complication rate (+10% at 7 days): Negative-pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) decreases complications but only when applied for less than 7 days. Recent limited evidence suggests that augmentation of NPWT with instillation for wound irrigation (NPWTi) might safely extend such window. This study hypothesizes that, through the combined cleansing effect of NPWT and instillation, NPWTi allows safe (low complication rate) delayed free flap repair in severe patients with Gustilo IIIb injuries (GIIIb).

Methods

A prospective case series was designed (inclusion criteria: GIIIb requiring microsurgical repair, severe patient/injury condition preventing immediate/early repair; exclusion criteria: allergy to NPWTi dressing). Patients received NPWTi (suction: 125 mmHg continuous; irrigation: NaCl 0.9%) until considered clinically ready for repair. Preoperative/postoperative complications (dehiscence, wound infection, bone non-union, osteomyelitis, flap failure) were monitored with clinical signs, imaging, and serum markers (CRP, WBC).

Results

Four patients (male: N = 4, female N = 1; Age: 59 [44–75] years-old) were treated. NPWTi was applied for 15.2 [9–28] days. No complication (0%) was observed preoperatively or postoperatively. Delayed repair occurred by latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap (N = 3), and anterolateral thigh flap (N = 2). All patients walked weight-bearing 12 [6–20] weeks after injury.

Conclusions

NPWTi seems to allow safe delayed free flap repair in patients with severe lower extremity injuries unable to undergo immediate/early repair.

Keywords: Free flap, Microsurgery, Lower extremity, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy, NPWTi

Abbreviations: NPWT, Negative-pressure Wound Therapy; NPWTi, Negative-pressure Wound Therapy with instillation for wound irrigation; GIIIb, Gustilo IIIb injuries

Highlights

-

•

NPWTi allows safe delayed free flap repair in severe patients with Gustilo IIIb injuries.

-

•

NPWTi achieved microsurgical repair with no preoperative/postoperative complications.

-

•

This study leverages preliminary evidence on NPWTi in lower extremity injuries.

1. Introduction

Over 340,000 traumatic injuries to the lower extremity occur yearly in the United States alone [1], with Gustilo IIIb injuries (GIIIb) have particularly high complication rates (deep infections 12%, bone non-unions 17–64%, amputations 6%) [2].

Immediately/early (<7 days) microsurgical repair significantly decreases complications, although overall rates remain high [3]. Veith et al. reported a complication rate of 32% after microsurgical repair [4], with a significantly higher rate observed in severe patients confirming that patient/injury stabilization is a critical prerequisite to microsurgical repair. Yet, delaying repair (>7 days) also determines a higher complication rate (~2-fold vs. <7 days) [3,5,6].

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) can be used for open wound management to mitigate the impact of delayed repair [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. Still, NPWT has shown to effectively reduce complications only when bridging to early microsurgical repair (<7 days) [6,[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Consistently, in most studies prolonged NPWT (>7 days) is associated with a higher complication rate [7,14,[17], [18], [19], [20]]. Only a handful of studies reported no benefit with the use of NPWT, regardless of timing of microsurgical repair [5,21,22].

Recently, investigators have sought to assess whether augmentation of NPWT with instillation (NPWTi) for wound irrigation could extend the “safe window” for delayed repair [[23], [24], [25], [26], [27]]. Evidence in orthopedic trauma care and other surgical fields suggests NPWTi further limits complications compared to NPWT [24,[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]]. NPWTi is conceptually consistent with open fracture wound irrigation [36]. Diehm et al. managed 30 patients with infected wounds (N = 11 for lower extremity trauma) with NPWTi (average: 13 days), describing a 77% reduction in wound colonization (details on repair technique not provided) [24]. Rikimaru et al. successfully managed 35 patients with Gustilo IIIb/c injuries (5% superficial infection rate) with a NPWTi-like system (repair by dermal matrix/skin grafting) [26]. Brem et al. successfully treated a pediatric case of infected GIIIb with prolonged NPWTi and skin graft repair [23]. Hasegawa et al. managed a case of GIIIb with 21 uneventful days of NPWTi before repair by an anterolateral thigh free flap [25]: this is the only reported case of GIIIb managed with NPWTi and delayed microsurgical repair.

This study leverages preliminary evidence on NPWTi in lower extremity injuries to validate its efficacy. Specifically, it hypothesizes that, through the combined cleansing of NPWT and instillation, NPWTi allows safe (low complication rate) delayed (>7 days) free flap repair in severe patients with GIIIb.

2. Methods

This is a single-center prospective case series, conducted from 01/2018 to 12/2020.

A staged orthoplastic management of injuries was adopted in patients with open fracture of the lower extremities. On the day of the injury, care included external fixation and surgical debridement. Postoperatively, NPWTi (V.A.C. VeraFlo Therapy, KCI, San Antonio, TX) was used for wound management, with NaCl 0.9% as cleanser. For instillation volumes, we used the minimum to soak the dressing (confirmed visually) [37]. A soak time of 10 min was used [38], with soaking at 3 h intervals [39], and a suction of 125 mmHg [30,40]. The dressing was changed once weekly and NPWTi was continued until the patient was able to undergo microsurgical repair (no tissue necrosis/infection, stable systemic conditions). Patients received i.v. antibiotics (Cefazolin, 3g/day) for 7 days. Repair was obtained by a microsurgical flap; choice of the flap was determined in accordance with literature [41,42].

Postoperative weight-bearing walking started after wound closure and stable bone callus formation (confirmed by imaging). After discharge, patients were re-evaluated at least monthly, with the longest follow up being at 6 months.

3. Results

3.1. Patients' and injuries’ characteristics

The study included 5 patients (Male:4; Female:1). Mean age was 59 years (range:44–75). All patients had normal weight (BMI:18.5–24.9). Comorbidities included asthma and atopic dermatitis (N = 1), hypertension rheumatisms and osteoporosis (N = 1), carotid stenosis (n = 1) and smoking habit (N = 1). ASA class was 2 (N = 4) and 1 (N = 1). Injuries were located to the thigh (N = 1; right femur fracture), the crus (N = 3; right tibia and fibula fractures, left tibia and fibula fractures), and the heel (N = 1; right calcaneus fracture). Mean wound area was 239 cm2 (range:51–706). One patient had a polytrauma (pelvic fracture) and required ICU stay[Table 1]. Average duration of NPWTi was 15.2 days (range:9–28), and mean soak volume was 35.6 mL (range:8–80)[Table 1]. Repair was achieved by free latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap (N = 3) or free anterolateral thigh flap (N = 2)[Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient and injury characteristics, and study data.

| Case # |

Age (years) | Gender | Comorbidities [ASA class] (Injury severity) |

Injury location | NPWTi duration (days) | Soak volume (mL) | Wound size (cm2) | Reconstructive procedure | Preoperative/postoperative complications [CRP; WBC on flap day] |

Weight-bearing walking (PIW) | Hospitalization (days) | Cost of care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | F | Hypertension, rheumatism, osteoporosis [ASA: 2] (/) |

Left tibia and fibula | 9 | 40 | 706 | Free LD flap (25 × 10cm; 20 × 10cm) |

None [0.17 mg/L; 3,870uL] |

12 | 83 | $51,826 |

| 2 | 43 | M | Asthma, atopic dermatitis [ASA: 2] (/) |

Right femur | 15 | 20 | 147 | Free LD flap (17 × 5cm; 17 × 6cm) |

None [0.2 mg/L; 6,320uL] |

11 | 35 | $28,301 |

| 3 | 51 | M | Smoking habit [ASA: 1] (/) |

Right calcaneus | 14 | 30 | 104 | Free ALT flap (17 × 7cm) |

None [0.03 mg/L; 7,470uL] |

9 | 86 | $36,957 |

| 4 | 53 | M | / [ASA: 2] (pelvic fracture, ICU) |

Right tibia and fibula | 28 | 80 | 188 | Free LD flap (30 × 8cm) |

None [0.17 mg/L; 7,600uL] |

20 | 77 | $68,444 |

| 5 | 75 | M | Carotid stenosis [ASA: 2] (/) |

Right tibia and fibula | 10 | 8 | 51 | Free ALT flap (17 × 6cm) |

None [0.04 mg/L; 6460uL] |

6 | 66 | $44,713 |

F: female; M: male; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiology; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NPWTi: negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time; LD flap: latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap; ALT flap: anterolateral thigh flap; CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: White blood cells count; PIW: post-injury week.

3.2. NPWTi allowed safe and effective delayed microsurgical repair with no complications

No complications (N = 0; 0%) were observed preoperatively or postoperatively at clinical/radiological evaluation[Table 1]. Bone union was achieved on average by post-injury month (PIM) 6 (range:5–10) and no additional treatment was required[Table 1]. Swabs at the end of NPWTi were negative for wound colonization; CRP and WBC on the day of microsurgical repair were within normal values (<1 mg/L; 6,300/uL)[Table 1]. All patients started weight-bearing walking on average by post-injury week (PIW) 12 (range:6–20)[Table 1].

Hospitalization was on average 69 days (range:35–86); cost of care was on average $46,048 (range:28,301–68,443)[Table 1].

4. Case presentation

4.1. Case #1

A 72-year-old woman sustained an open fracture of the left tibia in an accident when her left leg was squeezed between a brick wall and a passenger car because the driver pushed the accelerator, instead of the brake pedal while parking (Fig. 1A and B). On the day of injury, external fixation and surgical debridement for necrotic skin were performed at our orthopedics department (Fig. 1C), and NPWTi-d (suction pressure, −125 mmHg; soak volume, 40 mL) was started after surgery (Fig. 1D). After confirming the favorable condition of the open wound with skin and soft tissue defects, split thickness skin grafting was performed mainly in the sural area on post-injury day (PID) 9, and delayed reconstruction using free flap transplantation was performed 4 weeks later. The external fixation devices were removed and plate fixation was applied in the orthopedics department. The plate was placed between the tibia and the anterior tibial muscle, and the part of the plate was exposed at the body surface (Fig. 2A). Next, reconstruction of the defect (32 cm × 15 cm) was performed using a free divided latissimus dorsi flap in our department. Two islands (25 cm × 10 cm and 20 cm × 10 cm) were designed at the donor site (the right back) and elevated (Fig. 2B). Favorable blood flow of the flap was confirmed by separating the thoracodorsal blood vessels, and then two islands were separated by making an incision through to the fascia before dissecting the vascular pedicles and reconnected by suturing to make an large flap (32 cm × 15 cm) (Fig. 2C). The flap was transplanted to the defects in the left leg. End-to-side anastomosis was performed to connect the right thoracodorsal artery and left posterior tibial artery, and end-to-end anastomosis was performed to connect the right thoracodorsal vein and the left posterior tibial vein (Fig. 2D). The donor site was treated by a simple closure technique. No postoperative complications occurred, such as osteomyelitis and skin ulcers. Walking exercise with weightbearing was started from PIW 12. The patient could walk without supportive devices when she visited the outpatient department at PIM 6 (Fig. 3A and B), and bone union was achieved by PIM 10.

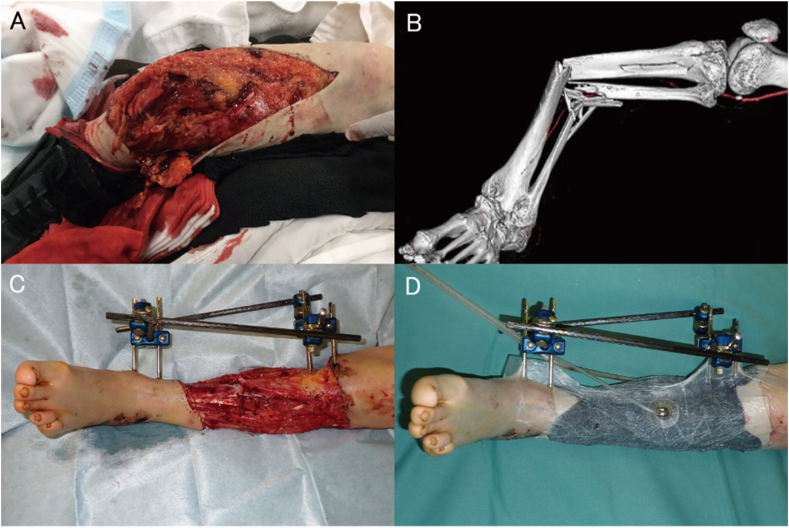

Fig. 1.

Case#1: open fracture of the left tibia in a 72-year-old female. A. Wound on the day of injury, showing significant tissue necrosis and bone exposure. B. 3D-CT imaging showing a complex fracture of the tibial and fibula shafts. C. Injury after emergency debridement and management of the fracture by external fixation. D. NPWTi applied to the injury after debridement and bone fixation.

Fig. 2.

Case#1: open fracture of the left tibia in a 72-year-old female. A. Status of the wound after 9 days of NPWTi and a split-thickness skin graft: no signs of soft tissue infection or residual necrosis are observed, partial bone coverage is noted. B. Surgical design for a divided latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap. C. The two skin islands of the divided latissimus dorsi flap are sutured together to allow maximal coverage. D. Microsurgical repair with the free latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap.

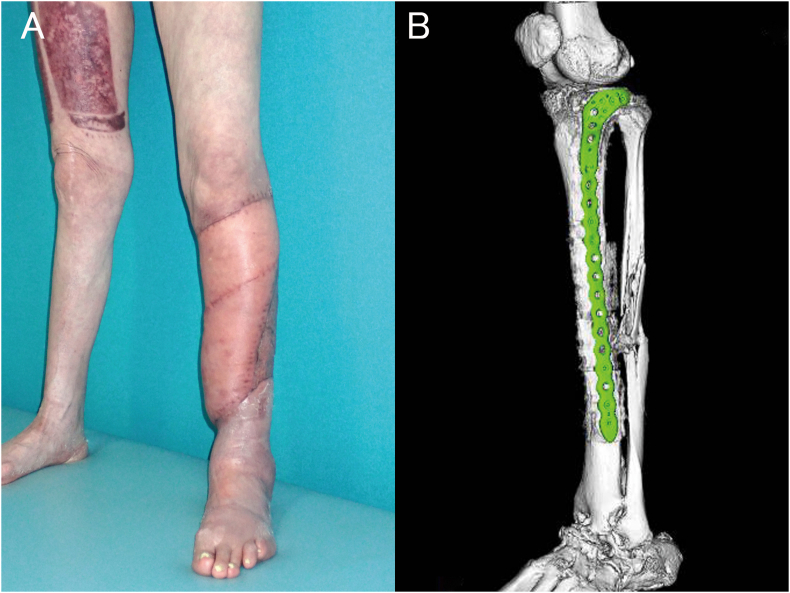

Fig. 3.

Case#1: open fracture of the left tibia in a 72-year-old female. A. Six-month clinical follow-up showing complete healing of soft tissue injuries. B. Six-month 3D CT imaging follow-up showing complete healing of tibial bone injuries with full bone union and no sign of osteomyelitis.

5. Discussion

In this series of severe patients with GIIIb unable to receive immediate/early repair, prolonged NPWTi (average:15.2 days [range:9–28]) was associated with no preoperative/postoperative complications, and successful delayed microsurgical repair with complete healing in all cases. The low complication rate/high success rate are comparable to those achievable with immediate/early microsurgical repair of GIIIb [16,43].

These outcomes expand previous reports on the use of NPWTi in GIIIb by Rikimaru et al. (35 patients; NPWTi: 33.8 days [range:15–59]; repair: dermal matrix/skin graft) reporting a 5% (2/35) complication rate (superficial wound infections) [26], Brem et al. (pediatric case; NPWTi: 6 days; repair: skin graft) reporting an eventful successful outcome [23], and Hasegawa et al. (adult case; NPWTi: 21 days; repair: free anterolateral thigh flap) observing no preoperative/postoperative complications [25]. More broadly, this study confirms positive findings on the use of NPWTi in complex lower extremity injuries [44], contaminated wounds [24], and other applications [[45], [46], [47], [48], [49]].

These findings contrast previous reports showing prolonged (>7 days) NPWT increases complications. Bhattacharyya et al. observed a 45% increase in infections in patients receiving prolonged (>7 days) NPWT [6]. Others have confirmed those observations [15,16], although some reported prolonged NPWT in GIIIb did not increase complications [17,19,20]. Overall, our data suggest NPWTi might “augment” the effectiveness of NPWT and extend the window for its safe use.

This study did not formally investigate the biological/physiological mechanisms of action of NPWTi. It is logical to speculate that NPWTi “augments” NPWT by adding the known benefits of wound irrigation [45,[50], [51], [52], [53]].

Our protocol involves irrigation with NaCl 0.9% to limit the risk of allergic reactions. No consensus exists on ideal solutions for NPWTi: investigators have used both NaCl 0.9% [24,26] and disinfectants-detergents [23,28]. A randomized study on NPWTi showed no difference between NaCl 0.9% and antiseptics in the management of infected wounds [30]. Similar findings have been reported when comparing open fracture irrigation with NaCl 0.9% or with antiseptics [36,50].

Finally, although we did not formally investigate cost-effectiveness, overall costs for patient care were limited (<$50,000). NPWTi can costs ~2-times more than NPWT [54]. Yet, when considering the cost of complications and their high incidence in GIIIb (especially in delayed reconstructions), cost of NPWTi seems reasonable: Olesen et al. report that in severe open tibial fractures repaired with free flaps infection increased direct costs by 60% (+$37,000) and doubled hospitalization [55].

This study has limitations: few cases, no controls, no formal statistical analysis, no comparison of NPWTi to NPWT or to standard wound care with/without irrigation, and no evaluation of different solutions or instillation protocols. Future research will need to validate these early findings in randomized controlled studies, also comparing NPWTi to NPWT and standard wound care with/without irrigation.

6. Conclusion

In an uncontrolled series of severe patients with GIIIb unable to receive immediate/early repair NPWTi allowed delayed microsurgical repair with no complications. Validation of these findings in controlled studies might help provide an additional tool for the management of lower extremity traumatic injuries.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

References

- 1.National trauma data bank annual report. 2016. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/trauma/ntdb/ntdb-annual-report-2016.ashx [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papakostidis C., Kanakaris N.K., Pretel J., Faour O., Morell D.J., Giannoudis P.V. Prevalence of complications of open tibial shaft fractures stratified as per the Gustilo–Anderson classification. Injury. 2011;42:1408–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudry U., Moran S., Karacor Z. Soft-tissue coverage and outcome of Gustilo grade IIIB midshaft tibia fractures: a 15-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:479–485. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817d60e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veith J., Donato D., Holoyda K., Simpson A., Agarwal J. Variables associated with 30-day postoperative complications in lower extremity free flap reconstruction identified in the ACS-NSQIP database. Microsurgery. 2019;39:621–628. doi: 10.1002/micr.30502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dedmond B.T., Kortesis B., Punger K., Simpson J., Argenta J., Kulp B. The use of negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the temporary treatment of soft-tissue injuries associated with high-energy open tibial shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(1):11–17. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31802cbc54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya T., Mehta P., Smith M., Pomahac B. Routine use of wound vacuum-assisted closure does not allow coverage delay for open tibia fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(4):1263–1266. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000305536.09242.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang K.T., Kim S.W., Sung I.H., Kim J.T., Kim Y.H. Is delayed reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi free flap a worthy option in the management of open IIIB tibial fractures? Microsurgery. 2016;36:453–459. doi: 10.1002/micr.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stannard J.P., Volgas D.A., Stewart R., McGwin G., Jr., Alonso J.E. Negative pressure wound therapy after severe open fractures: a prospective randomized study. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:552–557. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181a2e2b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum M.L., Esser M., Richardson M., Paul E., Rosenfeldt F.L. Negative pressure wound therapy reduces deep infection rate in open tibial fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:499–505. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31824133e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J.-H., Lee D.-H. Negative pressure wound therapy vs. conventional management in open tibia fractures: systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2019;50:1764–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X., Zhang H., Cen S., Huang F. Negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional wound dressings in treatment of open fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;53:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant-Freemantle M.C., Ryan É.J., Flynn S.O., Moloney D.P., Kelly M.A., Coveney E.I. The effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional dressing in the treatment of open fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34:223–230. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joethy J., Sebastin S.J., Chong A.K., Peng Y.P., Puhaindran M.E. Effect of negative-pressure wound therapy on open fractures of the lower limb. Singapore Med J. 2013;54:620–623. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezzadeh K.S., Nojan M., Buck A., Li A., Vardanian A., Crisera C. The use of negative pressure wound therapy in severe open lower extremity fractures: identifying the association between length of therapy and surgical outcomes. J Surg Res. 2015;199:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Z., Irgit K., Strohecker K.A., Matzko M.E., Wingert N.C., DeSantis J.G. Delayed flap reconstruction with vacuum-assisted closure management of the open IIIB tibial fracture. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2011;71:1705–1708. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31822e2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu D.S.H., Sofiadellis F., Ashton M., MacGill K., Webb A. Early soft tissue coverage and negative pressure wound therapy optimises patient outcomes in lower limb trauma. Injury. 2012;43:772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei S.-j., Cai X.-h., Wang H.-s., Qi B.-w., Yu A.-x. A comparison of primary and delayed wound closure in severe open tibial fractures initially treated with internal fixation and vacuum-assisted wound coverage: a case-controlled study. Int J Surg. 2014;12:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park C.H., Shon O.J., Kim G.B. Negative pressure wound therapy for Gustilo Anderson grade IIIb open tibial fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2016;50:536–542. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.189604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiert A.E., Gohritz A., Schreiber T.C., Krettek C., Vogt P.M. Delayed flap coverage of open extremity fractures after previous vacuum-assisted closure (VAC®) therapy–worse or worth? J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2009;62:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angelis S., Apostolopoulos A.P., Kosmas L., Balfousias T., Papanikolaou A. The use of vacuum closure-assisted device in the management of compound lower limb fractures with massive soft tissue damage. Cureus. 2019;11 doi: 10.7759/cureus.5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tahir M., Chaudhry E.A., Zimri F.K., Ahmed N., Shaikh S.A., Khan S. Negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional dressing for open fractures in lower extremity trauma: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J. 2020;102:912–917. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B7.BJJ-2019-1462.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng H.-T., Hsu Y.-C., Wu C.-I. Risk of infection with delayed wound coverage by using negative-pressure wound therapy in Gustilo Grade IIIB/IIIC open tibial fracture: an evidence-based review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2013;66:876–878. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brem M.H., Blanke M., Olk A., Schmidt J., Mueller O., Hening F.F. The vacuum-assisted closure (V.A.C.) and instillation dressing: limb salvage after 3 degrees open fracture with massive bone and soft tissue defect and superinfection. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111:122–125. doi: 10.1007/s00113-007-1360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diehm Y.F., Loew J., Will P.A., Fischer S., Hundeshagen G., Ziegler B. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) with V. A. C. VeraFlo in traumatic, surgical, and chronic wounds-A helpful tool for decontamination and to prepare successful reconstruction. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1740–1749. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasegawa I.G., Murray P.C. Circumferential negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell prior to delayed flap coverage for a type IIIB open tibia fracture. Cureus. 2019;11:e451. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rikimaru H., Rikimaru-Nishi Y., Yamauchi D., Ino K., Kiyokawa K. New alternative therapeutic strategy for Gustilo type IIIB open fractures, using an intra-wound continuous negative pressure irrigation treatment system. Kurume Med J. 2020;65:177–183. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.MS654009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eldenburg E., Pfaffenberger M., Gabriel A. Closure of a complex lower extremity wound with the use of multiple negative pressure therapy modalities. Cureus. 2020;12:e9247. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livingstone J.P., Hasegawa I.G., Murray P. Utilizing negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time for extensive necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:e3483. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dettmers R., Brekelmans W., Leijnen M., van der Burg B., Ritchie E. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time used to treat infected orthopedic implants: a 4-patient case series. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2016;62:30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim P.J., Attinger C.E., Oliver N., Garwood C., Evans K.K., Steinberg J.S. Comparison of outcomes for normal saline and an antiseptic solution for negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5) doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001709. 657e-64e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim P.J., Silverman R., Attinger C.E., Griffin L. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy with and without instillation of saline in the management of infected wounds. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.9047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omar M., Gathen M., Liodakis E., Suero E.M., Krettek C., Zeckey C. A comparative study of negative pressure wound therapy with and without instillation of saline on wound healing. J Wound Care. 2016;25:475–478. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.8.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uoya Y., Ishii N., Kishi K. Comparing the therapeutic value of negative pressure wound therapy and negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time in bilateral leg ulcers: a case report. Wounds. 2019;31:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanapathy M., Mantelakis A., Khan N., Younis I., Mosahebi A. Clinical application and efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1948–1959. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim P.J., Lavery L.A., Galiano R.D., Salgado C.J., Orgill D.P., Kovach S.J. The impact of negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation on wounds requiring operative debridement: pilot randomised, controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020;17:1194–1208. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhandari M., Jeray K.J., Petrisor B.A. A trial of wound irrigation in the initial management of open fracture wounds. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2629–2641. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lessing C., Slack P., Hong K.Z., Kilpadi D., McNulty A. Negative pressure wound therapy with controlled saline instillation (NPWTi): dressing properties and granulation response in vivo. Wounds. 2011;23(10):309–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giovinco N.A., Bui T.D., Fisher T., Mills J.L., Armstrong D.G. Wound chemotherapy by the use of negative pressure wound therapy and infusion. Eplasty. 2010;10:e9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim P.J., Attinger C.E., Steinberg J.S., Evans K.K., Lehner B., Willy C. Negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation: international consensus guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1569–1579. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a80586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birke-Sorensen H., Malmsjo M., Rome P., Hudson D., Krug E., Berg L. International Expert Panel on Negative Pressure Wound Therapy [NPWT-EP], Martin R, Smith J. Evidence-based recommendations for negative pressure wound therapy: treatment variables (pressure levels, wound filler and contact layer)--steps towards an international consensus. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(Suppl):S1–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pu L.L. Soft-tissue reconstruction of an open tibial wound in the distal third of the leg: a new treatment algorithm. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:78–83. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000250744.62655.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burns J.C., DeCoster R.C., Dugan A.J., Davenport D.L., Vasconez H.C. Trends in the surgical management of lower extremity Gustilo type IIIB/IIIC injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:183–189. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacKenzie E.J., Bosse M.J., Kellam J.F., Burgess A.R., Webb L.X., Swiontkowski M.F. Factors influencing the decision to amputate or reconstruct after high-energy lower extremity trauma. J Trauma. 2002;52(4):641–649. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gabriel A., Pfaffenberger M., Eldenburg E. Successful salvage of a lower extremity local flap using multiple negative pressure modalities. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8 doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goss S.G., Schwartz J.A., Facchin F., Avdagic E., Gendics C., Lantis J.C. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation (NPWTi) better reduces post-debridement bioburden in chronically infected lower extremity wounds than NPWT alone. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2012;4:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jccw.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee P. Treating fasciotomy wounds with negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) Cureus. 2016;8:e852. doi: 10.7759/cureus.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernández L., Ellman C., Jackson P. Use of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation in the management of complex wounds in critically ill patients. Wounds. 2019;31:E1–e4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cole W. Early-stage management of complex lower extremity wounds using negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and a reticulated open cell foam with through holes. Wounds. 2020;32:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmers M.S., Graafland N., Bernards A.T., Nelissen R.G., van Dissel J.T., Jukema G.N. Negative pressure wound treatment with polyvinyl alcohol foam and polyhexanide antiseptic solution instillation in posttraumatic osteomyelitis. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:278–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rupp M., Popp D., Alt V. Prevention of infection in open fractures: where are the pendulums now? Injury. 2020;51(Suppl 2):S57–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halawi M.J., Morwood M.P. Acute management of open fractures: an evidence-based review. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e1025–1033. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20151020-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gardezi M., Roque D., Barber D., Spake C.S., Glasser J., Berns E. Wound irrigation in orthopedic open fractures: a review. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2020 doi: 10.1089/sur.2020.075. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ludolph I., Fried F.W., Kneppe K., Arkudas A., Schmitz M., Horch R.E. Negative pressure wound treatment with computer-controlled irrigation/instillation decreases bacterial load in contaminated wounds and facilitates wound closure. Int Wound J. 2018;15:978–984. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabriel A., Kahn K., Karmy-Jones R. Use of negative pressure wound therapy with automated, volumetric instillation for the treatment of extremity and trunk wounds: clinical outcomes and potential cost-effectiveness. Eplasty. 2014;14:e41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olesen U.K., Pedersen N.J., Eckardt H., Lykke-Meyer L., Bonde C.T., Singh U.M. The cost of infection in severe open tibial fractures treated with a free flap. Int Orthop. 2017;41:1049–1055. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]