Abstract

Background

Depression is one of the most common morbidities of the postnatal period. It has been associated with adverse outcomes for women, children, the wider family and society as a whole. Treatment is with psychosocial interventions or antidepressant medication, or both. The aim of this review is to evaluate the effectiveness of different antidepressants and to compare their effectiveness with placebo, treatment as usual or other forms of treatment. This is an update of a review last published in 2014.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of antidepressant drugs in comparison with any other treatment (psychological, psychosocial, or pharmacological), placebo, or treatment as usual for postnatal depression.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Common Mental Disorders's Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO in May 2020. We also searched international trials registries and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of women with depression during the first 12 months postpartum that compared antidepressant treatment (alone or in combination with another treatment) with any other treatment, placebo or treatment as usual.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from the study reports. We requested missing information from study authors wherever possible. We sought data to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Where we identified sufficient comparable studies we pooled data and conducted random‐effects meta‐analyses.

Main results

We identified 11 RCTs (1016 women), the majority of which were from English‐speaking, high‐income countries; two were from middle‐income countries. Women were recruited from a mix of community‐based, primary care, maternity and outpatient settings. Most studies used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with treatment duration ranging from 4 to 12 weeks.

Meta‐analysis showed that there may be a benefit of SSRIs over placebo in response (55% versus 43%; pooled risk ratio (RR) 1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97 to 1.66); remission (42% versus 27%; RR 1.54, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.41); and reduced depressive symptoms (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.30, 95% CI −0.55 to −0.05; 4 studies, 251 women), at 5 to 12 weeks' follow‐up. We were unable to conduct meta‐analysis for adverse events due to variation in the reporting of this between studies. There was no evidence of a difference between acceptability of SSRI and placebo (27% versus 27%; RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.64; 4 studies; 233 women). The certainty of all the evidence for SSRIs was low or very low due to the small number of included studies and a number of potential sources of bias, including high rates of attrition.

There was insufficient evidence to assess the efficacy of SSRIs compared with other classes of antidepressants and of antidepressants compared with other pharmacological interventions, complementary medicines, psychological and psychosocial interventions or treatment as usual. A substantial proportion of women experienced adverse effects but there was no evidence of differences in the number of adverse effects between treatment groups in any of the studies. Data on effects on children, including breastfed infants, parenting, and the wider family were limited, although no adverse effects were noted.

Authors' conclusions

There remains limited evidence regarding the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants in the management of postnatal depression, particularly for those with more severe depression. We found low‐certainty evidence that SSRI antidepressants may be more effective in treating postnatal depression than placebo as measured by response and remission rates. However, the low certainty of the evidence suggests that further research is very likely to have an important impact on our effect estimate. There is a continued imperative to better understand whether, and for whom, antidepressants or other treatments are more effective for postnatal depression, and whether some antidepressants are more effective or better tolerated than others.

In clinical practice, the findings of this review need to be contextualised by the extensive broader literature on antidepressants in the general population and perinatal clinical guidance, to inform an individualised risk‐benefit clinical decision. Future RCTs should focus on larger samples, longer follow‐up, comparisons with alternative treatment modalities and inclusion of child and parenting outcomes.

Plain language summary

Antidepressant treatment for postnatal depression

Review question

In this Cochrane Review, we wanted to find out how well antidepressants work for treating women with postnatal depression.

Why this is important

Postnatal depression is depression that starts within 12 months of a woman having a baby. Many women are affected. Postnatal depression can have serious short‐ and long‐term effects on the mother, the baby, and the family as a whole.

There are several ways to treat postnatal depression. These include antidepressant medication, psychological therapy, support or counselling. The type of treatment offered depends on how severe the depression is, other illnesses and the woman's choice. In general, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding are often anxious about the potential unwanted effects of antidepressant medicines on their baby.

It is important to know whether antidepressants could be an effective and acceptable treatment for women with postnatal depression.

What we did

In May 2020, we searched for studies of antidepressants for women with postnatal depression. We looked for randomised controlled trials, in which treatments were given to study participants at random. These studies give the most reliable evidence.

We included 11 studies involving 1016 women. The studies compared antidepressants with placebo (dummy pill), treatment as usual (watch and wait, regular visits with a care co‐ordinator), psychological interventions (therapy), psychosocial interventions (peer support or counselling), any other other medicines or another type of antidepressant; and complementary medicine (food supplements).

Eight of the studies were conducted in English‐speaking, high‐income countries. The length of treatment ranged from four to 24 weeks.

The outcomes we focused on were how well the treatments worked (effectiveness). This was measured by the number of people who responded well to treatment (response) or no longer met criteria for depression at the end of treatment (remission). We also looked at whether women and/or their babies experienced adverse effects with the treatment.

What did we find?

We found that women treated with antidepressants may respond slightly better and have less severe postnatal depression than women given a placebo. The number of unwanted effects experienced by women was similar between groups. There were not enough studies comparing antidepressants with other types of treatment. The most commonly studied antidepressants were from the 'SSRI' (serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor) group.

Conclusions

This review found only a few relevant studies. There is some evidence that antidepressants may work better than a dummy pill for women with postnatal depression. There is not enough evidence comparing antidepressants to other treatments for postnatal depression. Clinicians need to consider study evidence from the general population and current clinical guidelines, along with the woman's illness history and current symptoms, to make an individualised risk‐benefit treatment decision with the woman.

Certainty of the evidence

Our certainty (confidence) in the evidence is low. Some findings are based on only a few studies, with a small number of women in each treatment group. Therefore, we are not sure how reliable the results are. Our conclusions may change if more studies are conducted. Our finding that antidepressants may work better than a dummy pill is similar to findings from a larger number of studies in the general population.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Postnatal depression, which is depression that occurs after a woman has given birth, is an important and common disorder that can have short‐ and long‐term adverse impacts on the mother, her child, and the family as a whole (Howard 2014a; Stein 2014). Perinatal suicide, which is closely linked to postnatal depression, is an important contributor to maternal mortality (Grigoriadis 2017; Khalifeh 2016; Knight 2019). Postnatal depression is associated with impaired maternal‐infant attachment, and with internalising and externalising problems in children of mothers who have postnatal depression, particularly where the depression is severe and persistent and there are familial co‐morbidities (Stein 2014). Postnatal depression has a similar epidemiology and clinical presentation to depression in the general population (Howard 2014a; Stewart 2019). It is characterised by persistent low mood and loss of pleasure or interests, occurring with associated symptoms such as changes in appetite and energy levels, disturbed sleep, and low self‐confidence (Howard 2014a; WHO 2018). The 11th revision of the International Classification for Diseases (ICD‐11; WHO 2018), and the 5th revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5; APA 2013), recommend the use of generic (non‐perinatal) mood disorder diagnostic categories for depression occurring in the postnatal period, in recognition of the absence of clear evidence for a distinct postnatal depressive clinical syndrome (O'Hara 2013). However, they allow for the use of a secondary perinatal diagnostic category (in ICD‐11) or specifier (in DSM‐5) for depression occurring in pregnancy or within four to six weeks after childbirth.

In the UK and internationally, research and clinical practice have most commonly defined postnatal depression as that occurring within a year of childbirth (Howard 2014a; NICE 2014; Stewart 2016; Stewart 2019), and this is the definition used in this review. However, there is no clear consensus on a definitive timeframe, and past research, practice guidelines, and diagnostic classifications have variably defined postnatal depression as depression occurring within four weeks to 12 months of delivery (O'Hara 2013; Stewart 2019). In the absence of a consensus, it has been helpfully proposed that the relevant timeframe is likely to vary according to study aim, with shorter time frames being most relevant for biological studies and longer time frames for prevention or treatment studies (O'Hara 2013).

A recent systematic review of prevalence and incidence of perinatal (i.e. antenatal and postnatal) depression estimated a pooled prevalence for postnatal depression of 9.5% (95% CI 8.9 to 10.1) in high‐income settings and 18.7% (95% CI 17.8 to 19.7) in low‐ and middle‐income settings, with no significant difference between studies using diagnostic tools (for example, a standardised structured diagnostic interview based on DSM criteria) versus those using symptom scales (such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS); Woody 2017). There are few incidence studies (Woody 2017), and contradictory evidence on whether depression is more likely to occur in the postnatal period than at other times in a woman’s life (Munk‐Olsen 2006; Silverman 2019; Stewart 2019); with some evidence that the risk is elevated specifically for more severe illness requiring admission (Munk‐Olsen 2009; Munk‐Olsen 2016). Recent evidence suggests that of women who experience postnatal depression, around a third also had depression in pregnancy, and a third had pre‐pregnancy depression (Wisner 2013).

Most women with postnatal depression recover within a few months but about 30% of episodes last beyond the first postnatal year (Goodman 2004). Women who have had postnatal depression in previous pregnancies also have a high risk (about 40%) of both non‐postnatal relapse and postnatal relapse in subsequent pregnancies (Cooper 1995; Wisner 2004).

It is important to distinguish postnatal depression from less severe, short‐lived conditions, such as the 'baby blues', which occur in around 50% of women and resolve spontaneously within a few days (Howard 2014a; Stewart 2019). On the other end of the severity spectrum, it is important to recognise the severe psychiatric emergency of postpartum psychosis, a rare condition affecting one to two women per 1000 in the general population, where admission is recommended to mitigate risks to mother and baby (Jones 2014). Clinically, postnatal depression is often co‐morbid with other conditions, particularly anxiety disorders (Stewart 2019).

Description of the intervention

UK national perinatal guidance recommends treatment for postnatal depression within a stepped‐care model, with antidepressant treatment being recommended for women with more severe depression, with or without combined treatment with psychological therapy (McAllister‐Williams 2017; NICE 2014). The guidance emphasises the higher threshold for antidepressant use in the perinatal period (given the uncertain risks of medication use during pregnancy and whilst breastfeeding, see below), and the importance of taking into account the woman’s preferences, illness severity, past response to treatment, and relative benefits and risks of different treatment options for mother and baby (Howard 2014b).

Antidepressant drugs are commonly divided into the classes of specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), with some additional antidepressants that fall outside these classes (e.g. venlafaxine, which is a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), and mirtazapine, which is a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA)). Antidepressants across different classes have a similar efficacy, so choice of antidepressant is generally guided by past response, side effect and safety profile. Additionally, in the perinatal period, choice is guided by the extent of safety data available for mothers and babies. In the general population, SSRIs are considered the first‐line antidepressant choice because they are relatively well‐tolerated and less dangerous in overdose than TCAs. In the past decade, SSRIs have been the most commonly prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy and the postnatal period, and have a relatively favourable reproductive safety profile (McAllister‐Williams 2017).

The safety of antidepressants whilst breastfeeding is an important consideration in postnatal depression treatment. Antidepressants ‐ and often their metabolites ‐ are lipid soluble and are transferred in breast milk. However, exposure to antidepressants in breastfed infants is considerably lower (5‐ to 10‐fold) than exposure in utero (Berle 2011). In general, passage of antidepressants into breast milk is low and most antidepressants are not contraindicated whilst breastfeeding (McAllister‐Williams 2017; Stewart 2019). Breastfeeding of premature or ill infants requires care and warrants discussion with paediatricians. There is some evidence from case reports that the less commonly used doxepin and bupropion may be associated with short‐term adverse effects on breastfed infants (McAllister‐Williams 2017; Stewart 2019). For all antidepressants, there is little evidence on long‐term outcomes for exposed infants (Orsolini 2015).

Due to the limitations and scarcity of the existing evidence, most manufacturers' data sheets carry warnings that antidepressants should be avoided in breastfeeding mothers. Some physicians, including general practitioners (GPs), general psychiatrists, or obstetricians, may advise women not to breastfeed when taking an antidepressant, prescribe reduced and potentially ineffective doses, or delay pharmacotherapy until after breastfeeding. However, postnatal depression has potential adverse effects for mother and baby (Howard 2014a; Stein 2014), and these need to be weighed against the uncertain but most likely small risks of medication exposure via breast milk. The choice of medication is usually guided not only by safety data but also past treatment response. Recent guidance recommends that if a mother was successfully treated for depression during her pregnancy, the same medication should be used in the postnatal period while breastfeeding, as discontinuing or switching an antidepressant treatment could lead to relapse (McAllister‐Williams 2017).

In terms of active comparators, evidence‐based psychological interventions for postnatal depression include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT), whilst psychosocial interventions include peer support and non‐directive counselling (Dennis 2007). These interventions were found to be effective when compared to usual care (Dennis 2007).

How the intervention might work

There is substantial evidence showing the effectiveness of antidepressants for depression in the general population, particularly as severity of depression increases (Cipriani 2018). The previous version of this review, published in 2014, concluded that antidepressants were more effective than placebo, but highlighted the very limited evidence base on this, with high risk of bias (Molyneaux 2014). In the general population, the exact mechanism by which antidepressants have their effect is unclear. Antidepressants enhance the functional availability of monoamine transmitters (serotonin, adrenaline and dopamine) through a variety of mechanisms, including inhibition of serotonin reuptake, deactivation of monoamine oxidase and antagonism at some serotonin receptors. However, their therapeutic action is delayed relative to these pharmacological effects, and research suggests that antidepressants may act through effects on synaptic plasticity, and through functional and structural changes in brain circuits related to emotional processing (Harmer 2017; Ma 2015). Postnatal depression is likely to comprise heterogeneous disorders, and it is hypothesised that most women with postnatal depression have depression that is aetiologically similar to depression outside the perinatal period, whereas a small subgroup have depression related to specific vulnerability to postnatal risk factors, such as altered sensitivity to reproductive hormonal changes (Stewart 2019). Therefore, antidepressants are expected largely to work in a similar way for postnatal depression as for non‐perinatal depression. Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed a new pharmacological treatment specifically developed for postnatal depression (the neuromodulator, brexanolone) and this is the focus of a separate Cochrane Review (Wilson (in press)).

Why it is important to do this review

This review updates the 2014 Cochrane Review of antidepressants for the treatment of postnatal depression (Molyneaux 2014). Postnatal depression is a common problem that can have adverse short‐ and long‐term effects on the mother, her child, and the wider family; including maternal suffering, problems with mother‐infant attachment, emotional and behavioural problems in children and, rarely, maternal suicide (Howard 2014a; Khalifeh 2016; Stein 2014). In general, women who are pregnant or postnatal have a preference for psychological therapy over medication, and are often anxious about the potential adverse effects of antidepressant use on the unborn or breastfeeding baby (O'Mahen 2008). Antidepressants are recommended for the treatment of severe postnatal depression, the treatment of moderate postnatal depression that has not responded to psychological therapy, and for preventing relapse among women with a history of severe depressive illness (NICE 2014). However, there is only limited evidence on antidepressant efficacy and safety for postnatal depression (Molyneaux 2014). The 2014 Cochrane Review identified six RCTs comparing antidepressants for postnatal depression to placebo or other treatment, with high risk of bias (particularly due to dropout), very limited data comparing antidepressants to psychological therapy, and lack of safety data on child outcomes among breastfeeding mothers (Molyneaux 2014). Since Molyneaux 2014, there has been a considerable growth in perinatal mental health research and services in the UK and internationally, with the UK government investing heavily in the development of community and inpatient perinatal mental health services. There is an urgent need for updated, high‐quality evidence to inform treatment for the growing number of women accessing help for postnatal mood disorders.

We have made minor changes to the Methods of the 2014 review, which are highlighted below. They reflect either changes between the previous protocol (Hoffbrand 2001), and the 2014 review (Molyneaux 2014), or a change in understanding of the clinical context in the scientific literature. The key objectives remain unchanged to Molyneaux 2014.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of antidepressant drugs in comparison with any other treatment (psychological, psychosocial, or pharmacological), placebo, or treatment as usual for postnatal depression.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all published and unpublished RCTs and cluster‐RCTs. We included studies employing a cross‐over design but excluded all other study designs, including quasi‐randomised trials and non‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Women of any age with postnatal depression, who were enrolled into a study and were not taking any antidepressant medication at the start of the study. Following a discussion of the recent scientific literature, we extended the eligible period of treatment onset from delivery to 12 months after giving birth, as opposed to six months after giving birth as used in Molyneaux 2014.

We only included those studies in which treatment was started after the birth. Trials in which treatment started antenatally (regardless of gestation) were excluded. If studies included both women who started treatment before the birth and those who started after, we included the study only if we could extract data on the women who started treatment postnatally.

Diagnosis

We used a broad definition of postnatal depression to include all women who were depressed during the first 12 months postpartum, regardless of time of onset of depression (i.e. including women whose depression started during or before pregnancy). We included studies in which women met criteria for depression by any of the following: use of a validated screening measure, for example, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox 1987), use of standard observer‐rated depression diagnostic instrument, by a recognised diagnostic scheme (e.g. DSM‐5; APA 2013), or the ICD‐11 (WHO 2018), or by other standardised criteria, for example, the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC; Spitzer 1978). The threshold scores used for the respective scales were those used by the study authors.

Co‐morbidities

We included studies that enrolled participants with co‐morbid physical conditions or other psychological disorders (e.g. anxiety) provided the co‐morbidity was not the focus of the study.

Setting

We did not assign any restrictions to the type of study setting.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Antidepressant medication alone or in combination with another antidepressant or treatment, initiated in at least one study arm.

We organised antidepressants into classes for the purposes of this review, for example:

SSRIs: citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline;

TCAs: amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, dothiepin, doxepin, imipramine, lofepramine, nortriptyline, protriptyline, trimipramine;

MAOIs; irreversible (isocarboxazid, phenelzine, tranylcipromine); reversible (brofaromine, moclobemide, tyrima);

SNRIs: duloxetine, milnacipran, venlafaxine;

other antidepressants.

Our primary analyses focused on SSRIs, as these are the most commonly used antidepressants for treatment of perinatal depression in recent routine clinical practice (McAllister‐Williams 2017; Yonkers 2014), and are the recommended first‐line antidepressant treatment in recent clinical guidance (McAllister‐Williams 2017; NICE 2014).

Comparator intervention

Placebo, any other treatment, or treatment as usual. Treatment as usual includes, but is not limited to, ‘watch and wait’, regular visits with a care co‐ordinator, or interventions aimed at addressing social risk factors). 'Any other treatment' includes, but is not limited to, psychological interventions (e.g. CBT or IPT), psychosocial interventions (e.g. peer support or non‐directive counselling) and other pharmacological interventions (e.g. another antidepressant). Complementary medicines are eligible as a comparator treatment within this group.

Brexanolone (a GABA‐A neuromodulator) was not included as a comparator intervention, as this novel treatment for postnatal depression was only recently approved by the FDA (in March 2019); and is currently only available in a small number of inpatient settings that can meet the FDA's risk mitigation measures (including medical supervision in an inpatient facility throughout the duration of its intravenous administration). We plan on conducting a separate Cochrane Review to assess its effectiveness and safety in the treatment of postnatal depression.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that met the above inclusion criteria regardless of whether they reported the following outcomes. We describe narratively any studies that report outcomes not included here.

Primary outcomes

Response or remission of depression, using dichotomous response or remission measures as reported in the individual studies and defined by the study authors. Response is typically measured by the number of women with a reduction of at least 50% on the total score of a standardised depression scale. Remission is typically measured by the number of women whose scores fall below a predefined threshold on a standardised depression scale. We report the study authors’ definitions in this review.

-

Adverse events (or side effects) experienced by:

mother;

nursing baby.

We extracted all adverse events and data from side‐effect scales recorded in the study reports and summarise them narratively. We also report overall proportions of participants experiencing adverse effects by study arm where possible.

Secondary outcomes

Severity of depression based on rating scales (continuous data; either self‐reported, such as the EPDS (Cox 1987), or clinician‐rated, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS; Hamilton 1967)

Acceptability of treatment both as assessed directly by questioning study participants and indirectly by the dropout rates

-

Child‐related outcomes:

neurodevelopment of the infant/child (e.g. cognitive development measured using age‐appropriate observer‐rated or parent‐reported standardised rating scales);

neglect or abuse of the baby (e.g. using the Parent‐Report Multidimensional Neglectful Behavior Scale (Kantor 2004)).

-

Parenting‐related outcomes:

maternal relationship with the baby (e.g. improved mother‐infant interactions measured using the CARE‐Index (Crittenden 1988));

overall maternal satisfaction and confidence;

the establishment or continuation of breastfeeding.

Quality of life (e.g. measured using the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36; Ware 1992))

Timing of outcome assessment

Early phase: under five weeks

Acute phase: 5 to 12 weeks

Continuation phase: more than 12 weeks

The primary outcome of interest is the acute phase treatment response (between 5 and 12 weeks). Where this was reported, we used any additional reported early and continuation phase responses as secondary outcomes.

See Appendix 1 for descriptions of the most commonly used scales for depression.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified all studies that described RCTs of antidepressants for postnatal depression from the specialised registers of Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) and the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. We supplemented these with further searches of the key biomedical databases.

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR)

The CCMD Group maintains an archived specialised register of RCTs: the CCMD Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR). This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm, and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially trials‐based register with more than 50% of reference records tagged to around 12,500 individually PICO‐coded study records. Reports of studies for inclusion in the register were collated from (weekly) generic searches of key bibliographic databases to June 2016, which included: MEDLINE (1950 onwards), Embase (1974 onwards), PsycINFO (1967 onwards), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of studies were also sourced from international trials registries, drug companies, handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) are on the Group's website, with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 2.

The CCMDCTR is hosted and maintained on the new Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS). The CCMDCTR fell out of date in June 2016 when the CCMD editorial group moved from the University of Bristol to the University of York.

(Note: the CCMD Group was previously called the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis (CCDAN) review group. The Group changed its name in 2015 and the re‐naming of the specialised register from CCDANCTR to CCMDCTR reflects this change).

Electronic searches

The CCMD Information Specialist searched the following biomedical databases using relevant keywords, subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource (Appendix 3). Searches for the previous version of this review were conducted in April 2014. Search updates for this version were conducted in April 2019 and May 2020. The date of the latest search was 1 May 2020.

CCMDCTR (all years to June 2016)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 5) via the Cochrane Library (searched 1 May 2020)

OVID MEDLINE (2014 to May 2020)

OVID Embase (2014 to May 2020)

OVID PsycINFO (2014 to May 2020)

We applied no restrictions on date, language, or publication status to the searches.

We searched the international trials registers (US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov searched 1 May 2020); and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 1 May 2020); using terms for postnatal/postpartum depression.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We performed forward and backward citation tracking of all included studies to identify additional studies missed from the original electronic searches (for example, unpublished or in‐press citations). We did not identify any additional studies.

Personal communication

We requested information on additional ongoing or completed studies from the following sources.

Any pharmaceutical company involved in any of the included studies (as funder, sponsor, or involvement in the research)

Manufacturers of the antidepressant(s) used in any of the included studies

Authors of included studies published within the last five years

The International Marcé Society for Perinatal Mental Health

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Child Birth's Controlled Trials Register (CPC) in April 2014. The search did not retrieve any additional, unique studies and we searched it via CENTRAL in the Cochrane Library after this date.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We managed records retrieved by the literature search in Covidence. Two of three review authors (JB and KA or CW) independently inspected abstracts retrieved from the search. We obtained full‐text articles for any potentially relevant publications. Two of three review authors (JB and KA or CW) independently assessed the full articles for inclusion based on the defined inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or by recourse to another review author (HK).

We recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We collated multiple reports that related to the same study, so that each study rather than each report forms the unit of interest in this review.

Data extraction and management

Using Covidence, we extracted the following data from the included studies.

Methods: date of study, study design, study setting, details of blinding/allocation concealment, total duration of study, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and location, and withdrawals

Participants: total number and number of each group, inclusion and exclusion criteria, mean age, age range, severity and duration of condition, diagnostic criteria, physical and mental health comorbidities

Interventions: number of intervention groups, type of interventions and comparisons, duration of intervention and key details (e.g. dosage, adherence, quality of delivery), concomitant medications, and excluded medications

Outcomes: details of measures used to assess outcomes (e.g. details of validation), primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, time points reported, and adverse events.

Analysis: statistical techniques used, unit of analysis for each outcome, subgroup analyses, number of participants followed up from each condition

Notes: publication type, funding for study, and notable conflicts of interest of study authors

Two of four review authors (JB, ES, CW, LR) independently extracted data from included studies. We resolved any disagreements in discussion or by recourse to another review author (HK).

We imported data into RevMan 5.4 for analysis (Review Manager 2020).

Main comparisons

We included the following main comparisons.

Antidepressants versus placebo

Antidepressants versus treatment as usual

Antidepressants versus psychological intervention

Antidepressants versus psychosocial intervention

Antidepressants versus other pharmacological intervention

Antidepressants versus complementary medicine

We present findings per antidepressant class (SSRIs, TCAs, SNRIs, MAOIs, other). We did not pool findings across studies of different antidepressant classes, since the different classes are not sufficiently homogeneous and are likely to have distinct adverse effects.

For our main analyses we focused on SSRI studies (i.e. studies that compare SSRIs versus each of the five comparison groups above).

We present findings separately for any studies reporting results on a mixture of antidepressant classes where data on individual classes are unavailable.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two of three review authors (JB, ES, or CW) independently assessed risk of bias (as high, low or unclear) for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We resolved any disagreements in discussion or by recourse to another review author (HK).

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other bias (adherence to medication), funding source, conflicts of interest

We used RevMan 5.4 to produce 'Risk of bias' figures based on our assessment of each domain as low, high, or unclear risk (Review Manager 2020). We tried to minimise the use of the unclear category by contacting study authors for further information as needed.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for primary outcome dichotomous data (Bland 2000).

If possible (e.g. where individual participant‐level data were available), we planned to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data using cut‐off points on rating scales to identify those who did and did not fulfil the criteria for depression.

Continuous data

Where meta‐analysis could be conducted for continuous data, we analysed these by calculating the mean difference (MD) between groups if studies used the same outcome measure for comparison. If studies used different outcome measures to assess the same outcome, we calculated standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CIs.

When study authors presented 95% CIs instead of standard deviations (SD), we converted the former to SDs. If study authors did not report SDs and we could not calculate these values from available data, we asked study authors to supply the data. In the absence of data from study authors, we used the mean SD from other studies.

Where study arm‐level data were unavailable, we used mean differences and their standard error (SE) in meta‐analyses using the generic inverse variance method.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

If any cluster‐RCTs had met the inclusion criteria for this review, we planned to extract the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) for each study; where no such data were reported, we planned to request the information from study authors. If this information was unavailable, in line with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019), we would have used estimates from similar studies in order to 'correct' data for clustering where this had not been done. We would have used generic inverse variance methods to meta‐analyse results from cluster‐RCTs (Higgins 2019).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Trials that have more than two arms (e.g. pharmacological intervention (A); psychological intervention (B); and control (C)) can cause issues with regards to pair‐wise meta‐analysis. In line with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019), for any studies with two or more active treatment arms, we took the following approach, dependent on whether the outcome was dichotomous or continuous. For a dichotomous outcome: we combined active treatment groups into a single arm for comparison against the control group (in relation to the number of people with events and sample sizes), or the control group was split equally. For a continuous outcome: we pooled means, SDs, and the number of participants for each active treatment group across treatment arms as a function of the number of participants in each arm to be compared against the control group.

Dealing with missing data

At some degree of loss to follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). The protocol for the review published in 2014 determined that studies with more than 50% loss to follow‐up would be excluded (Molyneaux 2014). However, owing to the small evidence base, the review authors decided to include studies with greater than 50% dropout. In the interest of consistency, we have taken the same approach for this review update. We have assessed the impact of data lost to follow‐up in sensitivity analyses.

In the case where included studies presented binary outcome data for women who were lost to follow‐up, we report the data. We present data on a 'once‐randomised always‐analyse' basis, assuming an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. We assumed that women lost to follow‐up had a negative outcome, with the exception of the outcome of death. For example, for the outcome of remission of depression, we assumed that this had not occurred for any of the women lost to follow‐up.

We used ITT analysis when available. We anticipated that some studies would have used a variety of imputation methods including last observation carried forward (LOCF), multiple imputation, and mixed‐effect models. All imputation methods require assumptions, which introduce uncertainty about the reliability of the results. Therefore, we indicate where studies have used imputation (and which methods) in this review.

We present ITT analysis for all primary outcomes. Where ITT analyses are unavailable for secondary outcomes, we report this in the relevant section of the results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where there were sufficient data for a meta‐analysis, we assessed statistical heterogeneity visually by studying the degree of overlap of the CIs for individual studies in a forest plot. We also carried out more formal assessments using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). The I2 statistic only provides an approximate estimate of the variability due to heterogeneity so the following overlapping bands have been used to guide our interpretation of the I2 statistic, as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2020):

0% to 40% might not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there had been more than 10 studies included in any meta‐analysis, we planned to generate funnel plots and inspect them visually for asymmetry. Asymmetry in the plot might be attributable to publication bias; however, there are other causes of funnel plot asymmetry (heterogeneity unrelated to publication bias) that we also planned to take into consideration.

Data synthesis

We conducted a random‐effects meta‐analysis to synthesise data from studies with comparable methods (using the same class of antidepressants and the same comparison group, e.g. placebo, listening visits) if we identified three or more studies for each comparison. We used RevMan 5.4 for meta‐analysis (Review Manager 2020).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in the following groups.

Women with mild to moderate depressive disorder (as defined by diagnostic interview or a validated scale) versus women with severe depressive disorder (as defined by diagnostic interview or a validated scale)

Women with chronic depression (onset pre‐pregnancy) versus women with onset in pregnancy versus new‐onset postnatal depression

Interventions lasting eight weeks or less versus interventions lasting more than eight weeks

We planned to compare subgroups using the formal Test for Subgroup Differences in RevMan 5.4 (Review Manager 2020).

We planned to explore and comment on any observed clinical heterogeneity, for example due to different definitions of postnatal depression or use of different diagnostic tools, in the 'Discussion' section of the review.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a priori sensitivity analyses (where we identified sufficient data) to explore the robustness of pooled estimates to decisions made in the systematic review. Where data were available, we assessed the effect of excluding studies with the following characteristics.

Study quality: excluding studies that had a high risk of bias in any domain

Blinding: excluding antidepressant versus placebo studies that were unblinded

-

Attrition:

excluding studies with more than 20% attrition; and

excluding studies with more than 50% attrition

Validation: excluding outcomes based on non‐validated scales from the analyses

For outcomes with both skewed data and non‐skewed data, we planned to investigate the effect of combining all data and if there was no substantive difference we left the potentially skewed data in the analyses.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created 'Summary of findings' tables, where we summarise findings of studies comparing SSRIs with each of the six comparison groups (i.e. placebo; treatment as usual; psychological interventions; psychosocial interventions, other pharmacological interventions and any other intervention). We have presented a separate 'Summary of Findings' table for each comparison group. We included the following outcomes: depression response, depression remission, adverse events (mother), adverse events (baby), depression severity, acceptability of treatment, and child‐related outcomes (where possible we planned to present data for 'child cognitive development'). Where possible, we have presented data for the acute phase treatment response (between five and 12 weeks) in this 'Summary of findings' table.

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies that contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in Chapter 14 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2020), using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We justify all decisions to downgrade the certainty of the evidence using footnotes, and make comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Two review authors (JB, LR) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence, and resolved disagreements through discussion or by consulting a third review author (HK). Judgements were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome.

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of included studies for this review. We avoid making recommendations for practice, and our implications for research suggest priorities for future research and outline what are the remaining uncertainties in the research area.

Results

Description of studies

This is an update of the review published in 2014 with the same title (Molyneaux 2014). We have kept the 2014 study selection criteria for this update with the exception of increasing the eligibility period to 12 months postpartum and removing the exclusion criterion based on attrition rates. These changes to the study selection methods are described in Criteria for considering studies for this review above.

Results of the search

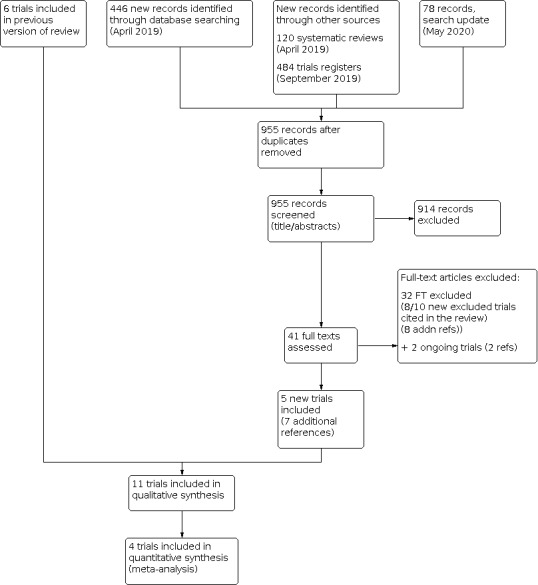

For this version of the review, we searched all databases in April 2019 and updated in May 2020. The searches retrieved 955 records. This included a search of the international trials registers (US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch)), which we conducted in September 2019 for ongoing studies using search terms for condition (only). We conducted the update search of the trials registers via CENTRAL in the Cochrane Library in May 2020.

A separate search for systematic reviews conducted in this area returned 120 records. We did not identify any new unique studies.

The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

1.

Flow diagram illustrating the study selection process

Included studies

The 2014 review (Molyneaux 2014), included six studies (Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Hantsoo 2013; Sharp 2010; Wisner 2006; Yonkers 2008), as well as two studies awaiting classification (Milgrom 2015; Wisner 2015), and one ongoing study (O'Hara 2019).

The 2020 review includes a total of 11 studies (33 references). This includes six included studies from the 2014 review and three studies previously identified as awaiting classification (Milgrom 2015; Wisner 2015) and ongoing (O'Hara 2019). Our update searches in 2019/2020 identified two additional studies eligible for inclusion (Chibanda 2014; Kashani 2017).

Two further studies Andriotti 2017 and IRCT20130418013058N11 are included as new, ongoing studies in this update (Characteristics of ongoing studies). We contacted the authors of both studies to confirm that they were still ongoing. Andriotti 2017 confirmed that, as of January 2020, recruitment for the study had not started. The authors of the IRCT20130418013058N11 study informed us that the study was complete but they did not respond to a request for the full results.

The 11 RCTs included in this review update provided data on 1016 women. Sample sizes ranged from 36 (Hantsoo 2013), to 254 (Sharp 2010), with the three largest studies (O'Hara 2019; Sharp 2010; Wisner 2006), contributing nearly half of the total number of included women (525/1016). All but three studies (Appleby 1997; Wisner 2006; Yonkers 2008), were published within the past 10 years. The majority of studies were conducted in English‐speaking, high‐income countries (Australia: Milgrom 2015; UK: Appleby 1997; Sharp 2010; USA: Hantsoo 2013; O'Hara 2019; Wisner 2006; Wisner 2015; Yonkers 2008). One study was conducted in Israel (high‐income country; Bloch 2012), one in Iran (upper‐middle‐income country; Kashani 2017), and one in Zimbabwe (lower‐middle‐income country; Chibanda 2014).

Participants

Four studies recruited women from community‐based or primary care settings (Appleby 1997; Chibanda 2014; Milgrom 2015; Sharp 2010), one from outpatient clinics (Kashani 2017), one from maternity wards (Bloch 2012), and three studies recruited from a range of settings that included all the above (Hantsoo 2013; O'Hara 2019; Yonkers 2008). Two studies did not report the setting (Wisner 2006; Wisner 2015). All but one study (Appleby 1997) reported a minimum age eligibility criterion. In eight studies, women had to be 18 years or older to be eligible to take part; Wisner 2006 included women aged 15 and over, Yonkers 2008 women aged 16 and over. Bloch 2012 and Wisner 2006 did not report the mean age of the participating women. In all other studies, women were in their mid 20s to early 30s.

All studies specified onset of depression within six months of delivery, with the majority recruiting women within the first three postnatal months.

Eight studies (Bloch 2012; Chibanda 2014; Hantsoo 2013; Kashani 2017; Milgrom 2015; O'Hara 2019; Wisner 2015; Yonkers 2008), used DSM‐IV criteria to establish a diagnosis of depression in eligible women. Appleby 1997 and Sharp 2010 used ICD‐10 criteria while Wisner 2006 used the HAM‐D. Additional diagnostic requirements and the use of screening tools are described in Characteristics of included studies.

All included studies specified a range of appropriate exclusion criteria. On the whole, women with current or recent severe mental illness (e.g. psychotic illness or bipolar disorder), suicidal ideation, acute physical illness, and/or substance abuse were ineligible to take part in the included studies. Some studies also excluded women with 'severe depression', for example, those requiring close monitoring or with high symptom scores (Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Chibanda 2014; Hantsoo 2013; Kashani 2017). Of the seven studies that provided data that could be used to characterise baseline depression severity, the mean score was consistent with 'mild depression' in three studies (Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Kashani 2017), and with 'moderate depression' in four studies (Chibanda 2014; Hantsoo 2013; O'Hara 2019; Yonkers 2008). Appleby 1997, Kashani 2017 and O'Hara 2019 excluded breastfeeding women (NB: O'Hara 2019 modified their eligibility criteria seven months into the study. Breastfeeding women were eligible from this point.) Hantsoo 2013; Milgrom 2015; O'Hara 2019; and Yonkers 2008 specifically excluded those women who were or were planning to become pregnant at the time of enrolment. Hantsoo 2013 and Yonkers 2008 further excluded women who had an onset of depression during pregnancy. Further details of exclusion criteria used in the individual studies can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

Interventions

With the exception of Sharp 2010, all studies used one pre‐specified antidepressant. Chibanda 2014 used the TCA amitriptyline; all other studies used SSRIs: fluoxetine (Appleby 1997; Kashani 2017); sertraline (Bloch 2012; Hantsoo 2013; Milgrom 2015; O'Hara 2019; Wisner 2006; Wisner 2015); and paroxetine (Yonkers 2008). Sharp 2010 used a pragmatic approach of comparing "antidepressant treatment" to a "wait and see" strategy and listening visits. Sharp 2010 recommended SSRIs as first‐line treatment, which the majority of women in the antidepressant group received.

Where reported, treatment duration ranged from four to 12 weeks. In the majority of studies, interventions were delivered for between four and six weeks. Details on the dosage schedules used in the included studies are reported in Characteristics of included studies.

Comparators

Six studies (Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Hantsoo 2013; O'Hara 2019; Wisner 2015; Yonkers 2008), used a placebo control group. Of these six studies, three (Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; O'Hara 2019), included an additional intervention in both the antidepressant and placebo groups (see Comparison 1 for details).

Three studies included a psychological intervention comparator (Chibanda 2014: group problem‐solving therapy; Milgrom 2015: group‐CBT; O'Hara 2019: IPT). Milgrom 2015 additionally included a combined group.

Two studies included a pharmacological intervention comparator; one comparing two antidepressants (Wisner 2006), and the other comparing an antidepressant to transdermal estradiol (Wisner 2015).

We identified only one study for each of the remaining comparison groups: treatment as usual (Sharp 2010: wait and see), psychosocial interventions (Sharp 2010: listening visits), and complementary medicine (Kashani 2017: saffron).

Eight studies contributed data to one of our comparison groups, whilst three studies (O'Hara 2019; Sharp 2010; Wisner 2015), each contributed data to two of our comparison groups.

See Characteristics of included studies for further details on comparator treatment schedules.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

We excluded a total of 10 studies (11 references). Two of these were also excluded in the previous version of this review. In seven studies, antidepressants were started during pregnancy rather than postpartum (Bais 2016; Khazaie 2013; Lambregtse‐Van Den Berg; Molenaar 2016; NCT02185547; NCT02188459; Tahmasian 2013). In two studies, the same antidepressant was given in both arms (Misri 2004; Zhao 2006). Yu 2015 did not report the age of babies and therefore it was not possible to establish that the study met inclusion criteria.

Risk of bias in included studies

As prespecified in our protocol, we only included RCTs in this review update (as was the case in the previously published versions). RCTs are generally considered to offer the most robust evaluation of the effectiveness of an intervention. However, methodological shortcomings can give rise to important biases that might unduly influence the study results. We assessed the risk of such biases in the included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. We present a summary below and in Figure 2. Details for each study can also be found in Figure 3 and the 'Risk of bias' tables (Characteristics of included studies).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study

Allocation

All but one study (Hantsoo 2013), described adequately produced randomisation sequences. This usually involved the use of computer software; several studies used permuted block randomisation. The risk of selection bias due to inadequate sequence generation was low across the included studies. However, only four studies (Kashani 2017; Milgrom 2015; Sharp 2010; Wisner 2015), described appropriate means of allocation concealment. The other studies did not report sufficient detail to allow us to judge whether or not the person carrying out the randomisation was able to anticipate the next group allocation as per the randomisation sequence. Consequently, across the included studies, the risk of selection bias due to weaknesses in allocation concealment is unclear.

Blinding

Where possible, we assessed the level of blinding separately for participants (performance bias), personnel (performance bias), and outcome assessors (detection bias).

Performance bias

For an evaluation of the risk of performance bias in the included studies it is important to bear in mind the nature of treatment and control interventions used. Three studies (Chibanda 2014; Milgrom 2015; Sharp 2010), compared antidepressants with group problem‐solving therapy, group‐CBT (and a combined group) and treatment as usual/listening visits, respectively. Due to the nature of the control interventions, blinding was not possible in these cases. The same is true for those participants in O'Hara 2019 who were part of the IPT arm. Despite blinding not being feasible or possible in these cases, the fact that personnel and participants were unblinded to treatment allocation means that there was a high risk of performance bias in these cases.

Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Hantsoo 2013; Kashani 2017; Wisner 2006; Wisner 2015; and Yonkers 2008 (all comparing antidepressants with placebo) reported adequate blinding of participants and personnel. Wisner 2015 used a three‐arm design (antidepressant, placebo, transdermal estradiol); appropriate strategies to blind participants and study personnel were reported for all three arms (placebo was available as both patches (to mimic estradiol) and pills so that participants did not know if they were in one of the two active treatment groups or the placebo group). O'Hara 2019 reported adequate blinding of participants and personnel for comparison between antidepressant treatment and placebo. In these instances, the risk of performance bias was low.

Detection bias

The majority of studies (Appleby 1997; Hantsoo 2013; Kashani 2017; O'Hara 2019; Wisner 2006; Wisner 2015; Yonkers 2008), reported adequate blinding of outcome assessors and were consequently at a low risk of detection bias. Three studies (Bloch 2012; Chibanda 2014; Milgrom 2015), reported insufficient detail to allow an assessment of detection bias (unclear risk of bias). Sharp 2010 explicitly stated that outcome assessors were not blinded (high risk of bias).

Incomplete outcome data

With the exception of Bloch 2012, all studies were at either high (Kashani 2017; Wisner 2006; Yonkers 2008), or unclear (Appleby 1997; Chibanda 2014; Hantsoo 2013; Milgrom 2015; O'Hara 2019; Sharp 2010; Wisner 2015), risk of attrition bias. This was mostly due to unclear or incomplete reporting of participants dropping out/lost to follow‐up and how this was addressed in analyses. Those studies judged to be at high risk of attrition bias reported imbalances in attrition between groups (Wisner 2006), a high dropout rate with reasons not reported (Yonkers 2008), or did not perform an ITT analysis (Kashani 2017).

Selective reporting

The assessment of reporting bias relies mostly on an inspection of the study protocol or registration record to assess if all pre‐specified outcomes were collected, reported, and analysed as planned. Trial protocols are not always published and trial registry entries are often poorly maintained. As such, for six out of the 11 included studies we were unable to assess the risk of reporting bias (unclear risk: Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Chibanda 2014; Hantsoo 2013; Wisner 2006; Wisner 2015). We judged the five remaining studies to be at high risk of reporting bias: Kashani 2017 (remission and response not defined in protocol, reported follow‐up schedule different from protocol); Milgrom 2015 (remission not defined in protocol); O'Hara 2019 (primary/secondary outcomes different between study publication and protocol); Sharp 2010 (paper does not report all outcomes specified in protocol); and Yonkers 2008 (scales reported in Methods section of paper not reported in Results).

Other potential sources of bias

Similarly, the assessment of other potential sources of bias is often hampered by incomplete reporting. Risk of bias for this domain was unclear for eight of the 11 included studies (Appleby 1997; Bloch 2012; Chibanda 2014; Hantsoo 2013; Kashani 2017; O'Hara 2019; Wisner 2015; Yonkers 2008). Two studies were at high risk of bias from group differences in attrition from the study (Sharp 2010), and low adherence (Milgrom 2015). We judged Wisner 2006 to be at low risk of bias from other sources.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Summary of findings 1. Antidepressants versus placebo for postnatal depression.

| Antidepressants versus placebo for postnatal depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women of any age, with PND up to 12 months Settings: any Intervention: antidepressant (SSRI) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with antidepressant | |||||

|

Depression response (acute, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

427 per 1000 | 543 per 1000 (414 to 719) |

RR 1.27 (0.97 to 1.66) |

205 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝a,b,c Low |

Three studies defined response as ≥ 50% reduction in EPDS or HAM‐D score from baseline. One study defined response as CGI‐I score of 1 or 2. |

|

Depression remission (acute, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

272 per 1000 | 419 per 1000 (269 to 655) |

RR 1.54 (0.99 to 2.41) |

205 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝a,b,c Low |

All studies defined remission as a score of ≤ 7 or ≤ 8 on EPDS or HAM‐D scales |

| Adverse events | Yonkers 2008 reported that some side effects appeared more common in the antidepressant group, no significant differences were found. Hantsoo 2013 reported side effects in 3/17 women from the sertraline group and 1/19 in the placebo group. No women dropped out due to side effects. Bloch 2012 showed no significant difference between treatment groups at week 8 (P = 0.46) or at week 12 (P = 0.94) in UKU Side Effect Rating scores, although the overall proportion of women experiencing side effects in each group was not given, neither were the details of types of side effects experienced. Appleby 1997 reported that 1 woman dropped out of the fluoxetine group and 3 women dropped out of the placebo group due to side effects, but the nature of these side effects was not reported. Side effects were only reported among women who dropped out of the study. Wisner 2015 used the Asberg rating scale for side effects. Comparing items rating moderate intensity, the only significant difference was for headaches, which were more common in the placebo (75%) group than the sertraline (43%) group (P = 0.03). For items rated 3 (severe), no significant differences between treatment groups were observed. 5 women (4/30 from sertraline group and 1/29 from placebo group) were withdrawn from the study as 4 developed hypomania (3 sertraline, 1 placebo) and 1 developed psychosis (sertraline). OHara 2019 reported that serious adverse events occurred in 10 women treated with sertraline and 7 women treated with placebo. |

⊕⊕⊝⊝d Low |

||||

|

Depression severity ‐ overall (acute, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

The mean depression severity score was between 7 and 13 | SMD 0.30lower (0.55 lower to 0.05 lower) |

‐ | 251 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝a,c Low |

Measured with HAM‐D or EPDS. Lower mean score = less severe depression. SMD 0.30 represents a small effect in favour of SSRI. This reflects a reduction of 1.68 on the EPDS scale or a reduction of 2.08 on the HAMD scale. |

|

Depression severity ‐ EPDS (acute, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

The mean EPDS score (acute phase) was between 8 and 14 | MD 3.51 lower (6.24 lower to 0.78 lower) | ‐ | 122 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝c,e Low |

Lower mean score = less severe depression |

| Treatment acceptability ‐ dropouts | 271 per 1000 |

298 per 1000 (201 to 445) |

RR 1.10 (0.74 to 1.64) |

233 (4 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝a,b,c Low |

|

| Child‐related outcomes | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI: Clinical Global Impressions; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; HAM‐D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MD: mean difference; PND: postnatal depression; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for high risk of attrition and reporting bias in one study, unclear risk of selection, detection, reporting and other bias in three other studies. bDowngraded one level for imprecision as the confidence interval includes no effect and appreciable harm. cDowngraded one level for imprecision as the number of participants is less than 400. dDowngraded two levels for high risk of attrition bias in one study and unclear risk of attrition bias in the remaining three studies, high risk of reporting bias in one study and unclear risk of reporting bias in the remaining three studies, unclear risk of selection bias in three studies, unclear risk of performance bias in one study and unclear risk of other bias in all four studies. eDowngraded one level for unclear risk of selection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other bias in two studies.

Summary of findings 2. Antidepressants versus treatment as usual for postnatal depression.

| Antidepressants compared with treatment as usual for postnatal depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women of any age, with PND up to 12 months Settings: any Intervention: antidepressant (based on GP or participant choice) Comparison: treatment as usual (including, but not limited to, ‘watch and wait’, regular visits with a care co‐ordinator, or interventions aimed at addressing social risk factors) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with treatment as usual | Risk with antidepressant | |||||

|

Depression response or remission (acute, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies reported this outcome at this time point | |

| Adverse events | No adverse events occurred | ‐ | 254 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b Very low |

||

|

Depression remission (early phase, < 5 weeks) |

196 per 1000 | 454 per 1000 (295to 695) | RR 2.31 (1.50 to 3.54) | 218 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b Very low |

Depression remission defined as EPDS score < 13 |

|

Depression severity ‐ mean EPDS score (early phase, < 5 weeks) |

The mean EPDS score was 16 | MD 2.50 lower (3.85 lower to 1.15 lower) | ‐ | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b Very low |

Lower mean score = less severe depression |

|

Treatment acceptability ‐ dropouts (early phase, < 5 weeks) |

104 per 1000 |

178 per 1000 (95 to 336) |

RR 1.71 (0.91 to 3.23) | 254 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b,c Very low |

From the reported data, it was not possible to determine whether this difference in withdrawal was due to a lack of acceptability of treatment with antidepressants or to other factors. |

| Child‐related outcomes | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; MD: mean difference; PND: postnatal depression; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to high risk of performance, detection, reporting and other biases. bDowngraded one level for imprecision as the number of participants is less than 400. cDowngraded one level for imprecision as the confidence interval includes no effect and appreciable harm.

Summary of findings 3. Antidepressants versus psychological interventions for postnatal depression.

| Antidepressants compared with psychological interventions for postnatal depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women of any age, with PND up to 12 months Settings: any Intervention: antidepressants (SSRI or TCA) Comparison: psychological interventions (group problem solving therapy, group CBT, IPT) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with psychological interventions | Risk with antidepressants | |||||

|

Depression response or remission (acute phase, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | One 3‐armed study reported no significant difference in response, defined as ≥ 50% reduction in HAM‐D‐symptoms from baseline (P = 0.05) or remission, defined as HAMD‐17 score ≤ 7 (P = 0.37), but the between‐group mean differences were not presented. | |

| Adverse events | Chibanda 2014 reported that 3 (11%) women in the amitriptyline arm discontinued due to adverse events. There were no adverse events in the women receiving group problem solving therapy. OHara 2019 reported serious adverse events in 10/56 women treated with sertraline and 8/53 women treated with IPT. Although authors state the number of instances of serious suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and worsening neurovegetative symptoms (N = 5), infant hospitalisations (N = 11) and participant hospitalisations (N = 9), it is not possible to determine how many occurred in which arm, or indeed if any occurred in the placebo arm of this 3‐armed study. Milgrom 2015 reported no adverse events. |

⊕⊕⊝⊝a Low |

||||

|

Depression severity ‐ mean EPDS score (acute phase, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

The mean EPDS score was 8 | MD 2.48 higher (0.71 higher to 4.25 higher) | ‐ | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝b,c Low |

Lower mean score = less severe depression |

| Treatment acceptability ‐ dropouts | 100 per 1000 |

107 per 1000 (24 to 488) |

RR 1.07 (0.24 to 4.88) | 58 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝b,c,d Very low |

|

| Child‐related outcomes | see comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies reported this outcome | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; HAM‐D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IPT: interpersonal therapy; PND: postnatal depression; RR: risk ratio; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for high risk of performance, reporting and other biases. bDowngraded one level for imprecision as the number of participants is less than 400. cDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias. dDowngraded one level for imprecision as the confidence interval includes no effect and appreciable harm.

Summary of findings 4. Antidepressants versus psychosocial interventions for postnatal depression.

| Antidepressants compared with psychosocial interventions for postnatal depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women of any age, with PND up to 12 months Settings: any Intervention: antidepressant (based on GP or participant choice) Comparison: psychosocial intervention (listening visits) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with psychosocial intervention | Risk with antidepressant | |||||

|

Depression response or remission (acute phase, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome at this time point | |

| Adverse events | No adverse events occurred | ‐ | 254 (1 RCT) |

‐ | ||

| Depression severity (acute phase, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| Treatment acceptability ‐ dropouts | 128 per 1000 |

248 per 1000 (143 to 429) |

RR 1.94 (1.12 to 3.35) | 254 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b Very low |

From the reported data, it was not possible to determine whether this difference in withdrawal was due to a lack of acceptability of treatment with antidepressants or to other factors. |

| Child‐related outcomes | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GP: general practitioner; PND: postnatal depression; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for high risk of performance, detection, reporting and other biases. bDowngraded one level for imprecision as the number of participants is less than 400.

Summary of findings 5. Antidepressants versus any other pharmacological intervention for postnatal depression.

| Antidepressants compared with any other pharmacological intervention for postnatal depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women of any age, with PND up to 12 months Settings: any Intervention: antidepressant (sertraline) Comparison: any other pharmacological intervention (nortriptyline or estradiol) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with any other pharmacological intervention | Risk with antidepressant | |||||

|

Depression response (acute phase, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

600 per 1000 | 588 per 1000 (456 to 762) | RR 0.98 (0.76 to 1.27) | 165 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b,c Very low |

Both studies defined response as ≥ 50% reduction in HAM‐D from baseline. |

|

Depression remission (acute phase, 5 ≤ 12 weeks) |

413 per 1000 see comment | 404 per 1000 (281 to 582) | RR 0.98 (0.68 to 1.41) | 165 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝a,b,c Very low |

Both studies defined remission as a score ≤ 7 or 8 on the HAM‐D scale. |

| Adverse events | Both studies reported no difference between groups in the overall number of moderate or severe side effects reported using the Asberg Side Effects Rating Scale. However, in one study, some side effects were more common among women who took nortriptyline than women taking sertraline: moderate to severe thirst (P = 0.02), dry mouth (P = 0.001) and constipation (P = 0.05). Other side effects were more common in the sertraline than nortriptyline group: constant or severe headaches (P = 0.05), increased perspiration (P = 0.04) and hot flushes interrupting sleep (P = 0.04) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

|