Abstract

Background

Self‐harm (SH; intentional self‐poisoning or self‐injury regardless of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation) is a growing problem in most countries, often repeated, and associated with suicide. Evidence assessing the effectiveness of pharmacological agents and/or natural products in the treatment of SH is lacking, especially when compared with the evidence for psychosocial interventions. This review therefore updates a previous Cochrane Review (last published in 2015) on the role of pharmacological interventions for SH in adults.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological agents or natural products for SH compared to comparison types of treatment (e.g. placebo or alternative pharmacological treatment) for adults (aged 18 years or older) who engage in SH.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Specialised Register, the Cochrane Library (Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL] and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [CDSR]), together with MEDLINE. Ovid Embase and PsycINFO (to 4 July 2020).

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing pharmacological agents or natural products with placebo/alternative pharmacological treatment in individuals with a recent (within six months of trial entry) episode of SH resulting in presentation to hospital or clinical services. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a repeated episode of SH over a maximum follow‐up period of two years. Secondary outcomes included treatment acceptability, treatment adherence, depression, hopelessness, general functioning, social functioning, suicidal ideation, and suicide.

Data collection and analysis

We independently selected trials, extracted data, and appraised trial quality. For binary outcomes, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence internals (CIs). For continuous outcomes we calculated the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. The overall certainty of evidence for the primary outcome (i.e. repetition of SH at post‐intervention) was appraised for each intervention using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included data from seven trials with a total of 574 participants. Participants in these trials were predominately female (63.5%) with a mean age of 35.3 years (standard deviation (SD) 3.1 years). It is uncertain if newer generation antidepressants reduce repetition of SH compared to placebo (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.19; N = 129; k = 2; very low‐certainty evidence). There may be a lower rate of SH repetition for antipsychotics (21%) as compared to placebo (75%) (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.50; N = 30; k = 1; low‐certainty evidence). However, there was no evidence of a difference between antipsychotics compared to another comparator drug/dose for repetition of SH (OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.50 to 4.58; N = 53; k = 1; low‐certainty evidence). There was also no evidence of a difference for mood stabilisers compared to placebo for repetition of SH (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.95; N = 167; k = 1; very low‐certainty evidence), or for natural products compared to placebo for repetition of SH (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.38 to 4.62; N = 49; k = 1; lo‐ certainty) evidence.

Authors' conclusions

Given the low or very low quality of the available evidence, and the small number of trials identified, there is only uncertain evidence regarding pharmacological interventions in patients who engage in SH. More and larger trials of pharmacotherapy are required, preferably using newer agents. These might include evaluation of newer atypical antipsychotics. Further work should also include evaluation of adverse effects of pharmacological agents. Other research could include evaluation of combined pharmacotherapy and psychological treatment.

Plain language summary

Drugs and natural products for self‐harm in adults

We have reviewed the international literature regarding pharmacological (drug) and natural product (dietary supplementation) treatment trials in the field. A total of seven trials meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. There is little evidence of beneficial effects of either pharmacological or natural product treatments. However, few trials have been conducted and those that have are small, meaning that possible beneficial effects of some therapies cannot be ruled out.

Why is this review important?

Self‐harm (SH), which includes intentional self‐poisoning/overdose and self‐injury, is a major problem in many countries and is strongly linked with suicide. It is therefore important that effective treatments for SH patients are developed. Whilst there has been an increase in the use of psychosocial interventions for SH in adults (which is the focus of a separate review), drug treatments are frequently used in clinical practice. It is therefore important to assess the evidence for their effectiveness.

Who will be interested in this review?

Hospital administrators (e.g. service providers), health policy officers and third party payers (e.g. health insurers), clinicians working with patients who engage in SH, patients themselves, and their relatives.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane Review from 2015 which found little evidence of beneficial effects of drug treatments on repetition of SH. This updated aims to further evaluate the evidence for effectiveness of drugs and natural products for patients who engage in SH with a broader range of outcomes.

Which studies were included in the review?

To be included in the review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials of drug treatments for adults who had recently engaged in SH.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

There is currently no clear evidence for the effectiveness of antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, or natural products in preventing repetition of SH.

What should happen next?

We recommend further trials of drugs for SH patients, possibly in combination with psychological treatment.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Self‐harm (SH), which includes all intentional acts of self‐poisoning (such as intentional drug overdoses) or self‐injury (such as self‐cutting), regardless of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation (Hawton 2003), has been a growing problem in most countries. In Australia, for example, it is estimated that there are now more than 26,000 general hospitalisations for SH each year, or a rate of 116.7 per 100,000 persons (Harrison 2014), similar to rates observed in a number of other comparable countries (Canner 2018; Griffin 2014; Morthorst 2016; Ting 2012; Wilkinson 2002). However, it is notable that rates of emergency department presentations for SH are often higher than hospitalisations (Bergen 2010; Corcoran 2015). In the UK, for example, higher rates of emergency department presentations for SH in both females (442 per 100,000) and males (362 per 100,000) have been reported (Geulayov 2016). There are also many more episodes of SH occurring in the community that do not come to the attention of clinical services. Worldwide, for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the rate of SH may be as high as 400 per 100,000, according to self‐report data (WHO 2014a).

In contrast to suicide rates, rates of hospital‐presenting SH are higher in females than in males in most countries (Canner 2018; Griffin 2014; Masiran 2017; Morthorst 2016; Ting 2012; Wilkinson 2002), with rates peaking in younger adults up to 24 years of age (Perry 2012). However, this difference decreases over the life cycle (Hawton 2008). SH is less common in older people, but tends to be associated with higher suicidal intent (Hawton 2008), with consequent greater risk of suicide (Murphy 2012).

For those who present to hospital, the most common method of SH is self‐poisoning. Overdoses of analgesics and psychotropics, especially paracetamol or acetaminophen, are common in some countries; particularly high‐income countries. Self‐cutting is the next most frequent method used by those who present to hospital. However, in the community, self‐cutting and other forms of self‐injury are far more frequent than self‐poisoning (Müller 2016).

SH is often repeated. Up to one‐quarter of those who present to hospital following SH return to the same hospital within a year (Carroll 2014; Owens 2002); although some individuals may present to another hospital. Others may not present to hospital at all given that studies identifying SH repetition via self‐report suggest that as many as one in five report further SH episodes following a hospital presentation (Carroll 2014). Repetition is more common in individuals who have a history of previous episodes of SH, personality disorder, psychiatric treatment, and alcohol or drug misuse (Larkin 2014). Risks of repeat SH may also be associated with method. Rates of repetition are higher among those who present to hospital following self‐injury alone (Carroll 2014; Lilley 2008), or combined self‐injury and self‐poisoning (Perry 2012), compared to those who present for self‐poisoning alone.

SH is associated with suicide. The risk of death by suicide within one year among people who present to hospital with SH varies across studies from nearly 1% to over 3% (Carroll 2014; Owens 2002). This variation reflects the characteristics of the population, and the background national suicide rate. In the UK, for example, during the first year after an episode of SH, the risk of suicide is around 50 times that of the general population, with a particularly high risk in men (Carroll 2014; Geulayov 2019). One quarter of these deaths are estimated to occur within one month after discharge, and almost 50% by three months (Forte 2019), although the risk of suicide appears to remain elevated for a number of years (Geulayov 2019). A history of SH is the strongest risk factor for suicide across a range of psychiatric disorders. Repetition of SH further increases the risk of suicide (Zahl 2004).

SH and suicide are the result of a complex interplay between genetic, biological, psychiatric, psychological, social, cultural, and other factors. Psychiatric disorders, particularly mood and anxiety disorders, are associated with the largest contribution to the risk of both SH (Hawton 2013), and suicide in adults (Ferrari 2014). Personality disorders, including borderline personality disorder, are also associated with SH, particularly frequent repetition. Alcohol use may also play an important role (Ferrari 2014). Both psychological and biological factors appear to further increase vulnerability to SH. Psychological factors may include difficulties in problem‐solving, low self‐esteem, impulsivity, vulnerability to having pessimistic thoughts about the future (i.e. hopelessness), and a sense of entrapment. Biological factors include disturbances in the serotonergic and stress response systems (van Heeringen 2014).

Description of the intervention

Given the high prevalence of depression in people who engage in SH, pharmacological interventions may include antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilisers (including anticonvulsants and lithium). SH also arises in the context of anxiety and general distress and thus anxiolytics (including both benzodiazepines and non‐benzodiazepine anxiolytics) may be trialled. Other pharmacological agents may also be trialled.

How the intervention might work

Antidepressants

In relation to the prevention of SH and suicidal behaviour, the primary mechanism would be the effect of antidepressants on depression. However, there might also be other relevant specific effects, such as with drugs acting on the serotonin system, it having been suggested that serotonin levels are relevant to impulsivity, which is a feature sometimes associated with suicidal behaviour (van Heeringen 2014).

While different classifications of antidepressants have been suggested, a currently accepted classification is non‐selective monoamine inhibitors (e.g., amitriptyline, imipramine, dosulepin), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram), monoamine oxidase inhibitors, sub‐grouped as non‐selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (e.g., phenelzine) and monoamine oxidase A inhibitors (e.g., moclobemide), and other antidepressants (e.g,. venlafaxine, mirtazapine, trazadone) (WHO 2014b).

An earlier approach was to group antidepressants as tricyclics, newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) (while recognising that many specific drugs in this category were introduced many years ago), and other antidepressants. This approach was used in the previous version of this review (Hawton 2015). For pragmatic reasons, we have therefore continued to use this categorisation in this update.

Antidepressants are often prescribed in the same dose range used to treat major depression. However, owing to the increased risk of overdose in this population, including the likelihood that people who engage in self‐poisoning may use their own medication (Gjelsvik 2014), antidepressants associated with lower case fatality indices are generally preferred (Hawton 2010), especially in people thought to be at risk of suicide.

Antipsychotics

In people with a history of repeat SH, treatment with antipsychotics may be used to reduce heightened levels of arousal often experienced by them, especially in relation to stressful life events. By reducing this arousal, the urge to engage in SH may be reduced, although there is little evidence for their efficacy in reducing suicidal behaviour in adults (Stoffers 2010). Lower doses may be prescribed to obtain this effect than is generally used in the treatment of psychotic disorders.

Anxiolytics, including both benzodiazepines and non‐benzodiazepine anxiolytics

Given this population experiences a high prevalence of anxiety disorders (Hawton 2013) anxiolytics, including benzodiazepines and non‐benzodiazepine anxiolytics, may be used to reduce suicidal behaviour (Tyrer 2012). However, because of their GABAminergic effects, benzodiazepines may increase aggression and disinhibition (Albrecht 2014). Current evidence is that benzodiazepines are associated with increased risk of suicidal behaviour (Dodds 2017). Therefore, it is usually recommended that benzodiazepines are used very cautiously, if at all, in people at risk of SH.

Mood stabilisers (including antiepileptics)

Mood stabilisers may have a role for people diagnosed with bipolar disorder or unipolar depression, especially to prevent the recurrence of episodes of mood disorder (Cipriani 2013b). Therefore, these drugs might reduce the risk of SH. However, to date, this effect has only been found for lithium (Cipriani 2013a; Smith 2017). Lithium may reduce the risk of SH via a serotonin‐mediated reduction in impulsivity and aggression. It is also possible that the long‐term clinical monitoring, which all persons prescribed lithium must undergo might contribute to a reduction in SH (Cipriani 2013a).

Other pharmacological agents

Other pharmacological agents, particularly the N‐Methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor antagonist, ketamine, may also be trialled. Ketamine has been shown to have an antisuicidal effect, independent of its antidepressant effects (Sanacora 2017). As a result, the FDA has recently granted approval for the use of both ketamine and esketamine, as adjunctive treatments to antidepressant therapy (FDA 2019). Ketamine has been associated with reduced suicidal ideation severity in the short term in adults with treatment‐resistant mood disorders (Wilkinson 2018; Witt 2020a). However, few trials have investigated the effect of ketamine over longer time periods. The effectiveness of ketamine on SH, and potential adverse effects of ketamine administration, such as dissociation, emergence psychosis, and rebound suicidal ideation, or behaviour, or both, remain under‐studied (Witt 2020a).

Natural products

There is some interest in the use of natural products, for example dietary supplementation of omega‐3 fatty acids (fish oils; Tanskanen 2001). Omega‐3 fatty acids have been implicated in the neural network, which is shown to correlate with the lethality of recent SH (Mann 2013). Blood plasma polyunsaturated fatty acid levels have also been implicated in the serotonin‐mediated link between low cholesterol and SH, suggesting that low omega‐3 fatty acid levels may have a negative impact on serotonin function (Sublette 2006). For those in whom SH is impulsive, omega‐3 supplementation may stimulate serotonin activity, thereby reducing the likelihood of engaging in SH (Brunner 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

SH is a major social and healthcare problem. It represents significant morbidity, is often repeated, and is linked with suicide. Many countries now have suicide prevention strategies, all of which include a focus on improved management of people presenting with SH (WHO 2014a). SH is also associated with substantial healthcare costs (Sinclair 2011). In the UK, the overall median cost per episode of SH has been estimated to be £809, although costs are significantly higher for cases of combined self‐injury and self‐poisoning, compared to either self‐injury or self‐poisoning alone. These costs are mainly attributable to health‐service level contact (i.e. inpatient stay or admission to intensive care; Tsiachristas 2017).

In the UK, the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) produced the first guideline on the treatment of SH behaviours in 2004 (NCCMH 2004). This guideline focused on the short‐term physical and psychological management of SH. This guidance was updated in 2011, using interim data from a previous version of this review as the evidence‐base, and focused on the longer‐term psychological management of SH (NICE 2011). Subsequently, similar guidelines have been published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (Carter 2016), and German Professional Associations and Societies (Plener 2016), amongst others (Courtney 2019).

In 2021, the guidance contained in the 2011 NICE guidelines for the longer‐term management of SH will be due for updating. Therefore, we are updating our review (Hawton 2015), in order to provide contemporary evidence to guide clinical policy and practice.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological agents or natural products for self‐harm (SH) compared to comparison types of treatment (e.g. placebo or alternative pharmacological treatment) for adults (aged 18 years or older) who engage in SH.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of specific pharmacological agents or natural products versus placebo, or any other pharmacological comparisons in the treatment of adults with a recent (within six months of trial entry) presentation for self‐harm (SH). All RCTs (including cluster‐RCTs and cross‐over trials) were eligible for inclusion regardless of publication type or language; however, we excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

While exact eligibility criteria often differ both within and between regions and countries (Witt 2020b), we included participants of both sexes and all ethnicities, who were 18 years and older, with a recent (i.e. within six months of trial entry) presentation to hospital or clinical services for SH.

We defined SH as all intentional acts of self‐poisoning (such as intentional drug overdoses) or self‐injury (such as self‐cutting), regardless of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation (Hawton 2003). This definition includes acts intended to result in death ('attempted suicide'), those without suicidal intent (e.g. to communicate distress, to temporarily reduce unpleasant feelings, sometimes termed 'non‐suicidal self‐injury'), and those with mixed motivation. We did not distinguish between attempted suicide and non‐suicidal self‐injury in this review, because there is a high level of co‐occurrence between them, and the two cannot be distinguished in any reliable way, including on levels of suicidal intent (Klonsky 2011). Lastly, the motivations for SH are complex and can change, even within a single episode (De Beurs 2018).

We excluded trials in which participants were hospitalised for suicidal ideation only (i.e. without evidence of SH).

Types of interventions

Interventions

These included the following.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, e.g. amitriptyline).

Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs), such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs, e.g. fluoxetine), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, e.g. venlafaxine), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs, e.g. reboxetine), norepinephrine‐dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs, e.g., bupropion), tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g. maprotiline), noradrenergic specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs, e.g. mirtazapine), serotonin antagonist or reuptake inhibitors (SARIs, e.g. trazodone), or reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase type A (RIMAs, e.g. moclobemide).

Other antidepressants, such as irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs, e.g. phenelzine).

Antipsychotics (e.g. quetiapine).

Anxiolytics, including both benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam), and non‐benzodiazepine anxiolytics (e.g. buspirone).

Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics (e.g. sodium valporate) and lithium.

Other pharmacological agents (e.g. ketamine).

Natural products (e.g. omega‐3 essential fatty acid supplementation).

Comparators

In pharmacological trials, where a comparison with the specific effects of a drug is being made, the comparator is typically placebo, which consists of any pharmacologically inactive treatment, such as sugar pills or injections with saline. We also included trials in which another pharmacological intervention (such as another standard pharmacological agent, reduced dose of the intervention agent, or active comparator) was used.

Combination interventions

We also planned to include combination interventions, where any pharmacological agent of any class, as outlined above, is combined with psychological therapy. However, as the focus of this review is the effectiveness of pharmacological agents for people who self harm, we only included such trials if both the intervention and control groups received the same psychological therapy, to ensure that any potential effect of the psychosocial therapy was balanced across both groups. The effectiveness of psychosocial therapy alone for adults who engage in SH behaviours is the subject of a separate review (Hawton 2016).

Types of outcome measures

For all outcomes, we were primarily interested in quantifying the effect of treatment assignment to the intervention at baseline, regardless of whether the intervention was received as intended (i.e. the intention‐to‐treat effect).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure in this review was the occurrence of repeated SH over a maximum follow‐up period of two years. Repetition of SH was identified through self‐report, collateral report, clinical records, or research monitoring systems. As we wished to incorporate the maximum data from each trial, we included both self‐reported and hospital records of SH, where available. Preference was given to clinical records over self‐report where a study reported both measures. We also reported proportions of participants repeating SH, frequency of repeat episodes, and time to SH repetition (where available).

Secondary outcomes

Given increasing interest in the measurement of outcomes of importance to those who engage in SH (Owens 2020), we planned to analyse data for the following secondary outcomes (where available) over a maximum follow‐up period of two years.

Treatment acceptability

This was measured by differences in discontinuation rates for any reason.

Treatment adherence

This was assessed using a range of measures of adherence, including: pill counts, changes in blood measures, and the proportion of participants that both started and completed treatment.

Depression

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of depression symptoms, for example total scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961), or scores on the depression sub‐scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants who meet defined diagnostic criteria for depression.

Hopelessness

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of hopelessness, for example, total scores on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck 1974), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reporting hopelessness.

General functioning

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of general functioning, for example, total scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; APA 2000), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reporting improved general functioning.

Social functioning

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of social functioning, for example, total scores on the Social Adjustment Scale (SAS; Weissman 1999), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reporting improved social functioning.

Suicidal ideation

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of suicidal ideation, for example, total scores on the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS; Beck 1988), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reaching a defined cut‐off for ideation.

Suicide

This included register‐recorded deaths, or reports from collateral informants, such as family members or neighbours.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

An information specialist searched the following databases (to 4 July 2020), using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax as appropriate for each resource: Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Specialised Register (Appendix 1), Cochrane Library (Central Register of Controlled Trials; CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, and PsycINFO Ovid (Appendix 2).

A date restriction was applied as the search was to update an earlier version of this review (Hawton 2015). However, we did not apply any further restrictions on language or publication status to the searches.

We searched for retraction statements and errata once the included studies were selected.

We also searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov to identify ongoing trials.

Searching other resources

Conference abstracts

In addition to conference abstracts retrieved via the main electronic search, we also screened the proceedings of recent (last five years) conferences organised by the largest scientific committees in the field:

International Association for Suicide Prevention (both global congresses and regional conferences), and;

Joint International Academy of Suicide Research and American Foundation for Suicide Prevention International Summits on Suicide Research.

Reference lists

We also checked the reference lists of all relevant RCTs, and the reference lists of major reviews that included a focus on pharmacological interventions for SH in adults (Hawton 2015).

Correspondence

We consulted the corresponding authors of trials, and other experts in the field to find out if they are aware of any ongoing or unpublished RCTs on the pharmacological treatment of adults who engage in SH that were not identified by the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors KW, KH, and one of either SH, GR, TTS, ET, or PH, independently assessed the titles of reports identified by the electronic search for eligibility. We distinguished between:

eligible or potentially eligible trials for retrieval, in which any psychosocial intervention was compared with a comparator (e.g., placebo or alternative pharmacological treatment);

ineligible general treatment trials, not for retrieval (i.e. where there was no control treatment.

All trials identified as potentially eligible for inclusion then underwent a second screening. Pairs of review authors, working independently from one another, screened the full text of eligible or potentially eligible trials to identify whether the trial met our inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements in consultation with the senior review author (KH). Where disagreements could not be resolved from the information reported in the trial, or where it was unclear whether the trial satisfied our inclusion criteria, we contacted corresponding trial authors for additional clarification.

We identified and excluded duplicate records, and collated multiple reports of the same trial, so that each trial, rather than each report, represented the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Liberati 2009), and completed a 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Review author KW and one of either SH, or GR independently extracted data from the included trials, using a standardised extraction form. Where there were any disagreements, they were resolved in consensus discussions with KH.

Data extracted from each eligible trial included the following.

Participant information: number randomised, number lost to follow‐up or withdrawn, number analysed, mean or median age, sex composition, diagnoses, diagnostic criteria, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria.

Methods: trial design, total duration of the trial, details of any 'run in' period (if applicable), number of trial centres and their location, setting, and date.

Intervention(s): details of the intervention, including dose, duration, route of administration, whether concomitant medications were permitted and details of these medications, and any excluded medications.

Comparator(s): details of the comparator, including dose, duration, route of administration, whether concomitant medications were permitted and details of these medications, and any excluded medications.

Outcomes: raw data for each eligible outcome (see Types of outcome measures), details of other outcomes specified and reported, and time points at which outcomes were reported.

Notes: source of trial funding, and any notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

We extracted both dichotomous and continuous outcomes data from eligible trials. As the use of non‐validated psychometric scales is associated with bias, we extracted continuous data only if the psychometric scale used to measure the outcome of interest had been previously published in a peer‐reviewed journal, and was not subjected to item, scoring, or other modification by the trial authors (Marshall 2000).

We planned the following main comparisons.

Tricyclic antidepressants versus placebo.

Tricyclic antidepressants versus another comparator drug or dose.

Newer generation antidepressants versus placebo.

Newer generation antidepressants versus another comparator drug or dose.

Any other antidepressants versus placebo.

Any other antidepressants versus another comparator drug or dose.

Antipsychotics versus placebo.

Antipsychotics versus another comparator drug or dose.

Anxiolytics, including benzodiazepines and non‐benzodiazepine anxiolytics, versus placebo.

Anxiolytics, including benzodiazepines and non‐benzodiazepine anxiolytics, versus another comparator drug or dose.

Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium, versus placebo.

Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium, versus another comparator drug or dose.

Other pharmacological agents versus placebo.

Other pharmacological agents versus another comparator drug or dose.

Natural products versus placebo.

Natural products versus another comparator drug or dose.

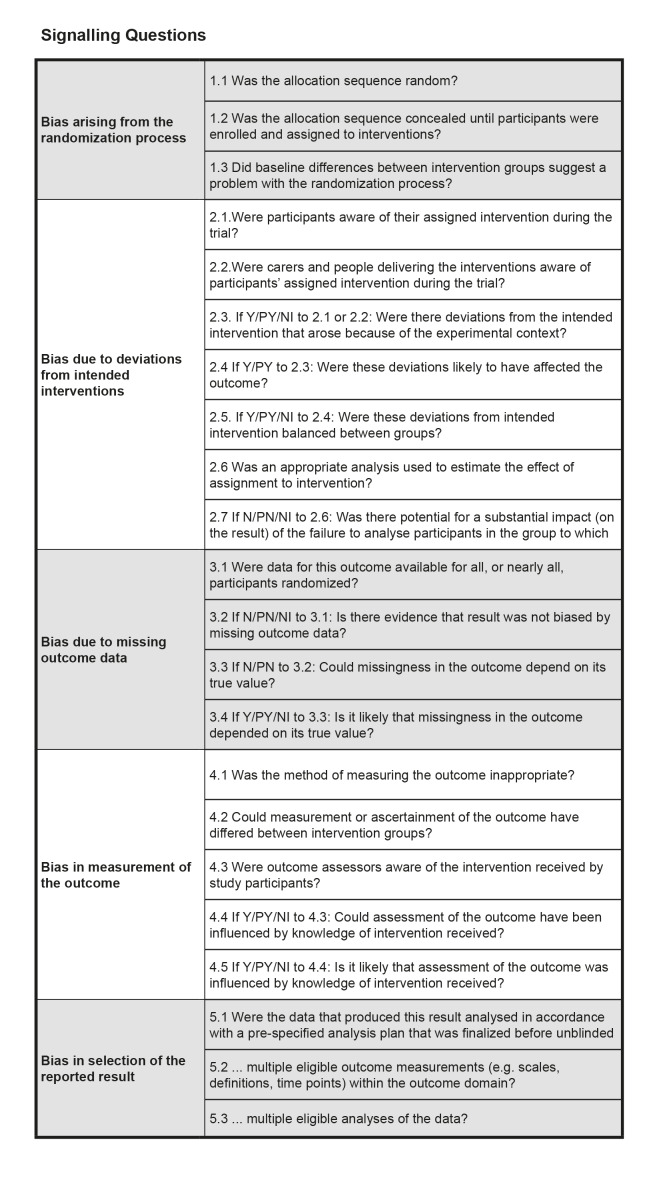

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Highly biased studies are more likely to overestimate treatment effectiveness (Moher 1998). Review author KW and one of either SH, or GR independently evaluated the risk of bias for the primary outcome (i.e. repetition of SH post‐intervention) by using version 2 of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, RoB 2 (Sterne 2019). This tool encourages consideration of the following domains:

Bias in the randomisation process.

Deviations from the intended intervention (assignment to intervention).

Missing outcome data.

Bias in the measurement of the outcome.

Bias in the selection of the reported result.

For cluster‐RCTs, we also evaluated the following.

Bias arising from the timing of identification and recruitment of participants.

Signalling questions in the RoB 2 tool provided the basis for the tool’s domain‐level judgements about the risk of bias. Two review authors independently judged each source of potential bias low risk, high risk, or some concerns. An overall 'Risk of bias' judgement was then made for each study by combining ratings across these domains. Specifically, if any of the above domains were rated at high risk, the overall 'Risk of bias' judgement was rated at high risk. We reported this overall judgement, which can also be low risk, high risk, or some concerns, in the text of the review, and in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Where inadequate details were provided in the original report, we contacted corresponding trial authors to provide clarification. We resolved disagreements through discussions with KH.

We entered and organised our RoB 2 assessments on an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel RoB2 Macro), and made them available as electronic supplements.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes

We summarised dichotomous outcomes, such as the number of participants engaging in a repeat SH episode, or number of deaths by suicide, using the summary odds ratio (OR) and the accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI), as the OR is the most appropriate effect size statistic for summarising associations between two dichotomous groups (Fleiss 1994).

Continuous outcomes

For outcomes measured on a continuous scale, we used mean differences (MDs) and accompanying 95% CI where the same outcome measure was used. Where different outcome measures were used, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) and its accompanying 95% CI.

We aggregated trials in a meta‐analysis only where treatments were sufficiently similar. For trials that could not be included in a meta‐analysis, we provided narrative descriptions of the results.

Hierarchy of outcomes

Where a trial measured the same outcome, for example depression, in two or more ways, we planned to use the most common measure across trials in any meta‐analysis. We also planned to report scores from other measures in a supplementary table.

Timing of outcome assessment

The primary end point for this review was post‐intervention (i.e, at the conclusion of the treatment period). We also reported outcomes for the following secondary end points (where data were available).

Between zero and six months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between six and 12 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between 12 and 24 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Where there was more than one outcome assessment within a time period, we used data from the last assessment in the time period, unless different outcomes are assessed at different time points. For treatment adherence, we also planned to use within‐treatment results.

Unit of analysis issues

Zelen design trials

Trials in this area are increasingly using Zelen's method, in which consent is obtained subsequent to randomisation and treatment allocation (Witt 2020b). This design may lead to bias if, for example, participants allocated to one particular arm of the trial disproportionally refuse to provide consent for participation or, alternatively, if participants only provide consent if they are allowed to cross over to the other treatment arm (Torgerson 2004).

Although no trial included in this review used Zelen's design, should we identify a trial using Zelen's method in future updates of this review, we plan to extract data for all randomised participants as this is consistent with Zelen's original intention (Zelen 1979), and preserves randomisation. This will typically be possible for our primary outcome, repetition of SH, as this will generally be ascertained from clinical, hospital, and/or medical records. However, for certain self‐reported outcome measures, data may only be reported on the basis of those who consented to participation. We therefore also plan to conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate what impact, if any, the inclusion of these trials may have on the pooled estimate of treatment effectiveness.

Cluster‐randomised trials

Cluster randomisation, for example by clinician or general practice, can lead to overestimation of the significance of a treatment effect, resulting in an inflation of the nominal type I error rate, unless appropriate adjustment is made for the effects of clustering (Donner 2002; Kerry 1998).

Although no trial included in this review used cluster randomisation, should we identify a trial using cluster randomisation in future updates of this review, we will follow the guidance outlined in Higgins 2019a. Specifically, where possible, we will analyse data using measures that statistically accounted for the cluster design. Where this is not possible, we will analyse data using the effective sample size.

Cross‐over trials

A primary concern with cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect, in which the effect of the intervention treatment (e.g. pharmacological, physiological, psychological) influences the participant's response to the subsequent control condition (Elbourne 2002). As a consequence, on entry to the second phase of the trial, participants may differ systematically from their initial state, despite a wash‐out phase. In turn, this may result in a concomitant underestimation of the effectiveness of the treatment intervention (Curtin 2002a; Curtin 2002b).

No trial included in this review used cross‐over methodology. However, should we identify any cross‐over trials in future updates of this trial, we will only extract data from the first phase of the trial, prior to cross‐over, to protect against the carry‐over effect.

Studies with multiple treatment arms

One trial in the current review included multiple treatment arms (Hirsch 1982). As both intervention arms in this trial investigated the effectiveness of newer generation antidepressants (i.e. mianserin or nomifensine), we combined dichotomous data from these two arms. For continuous outcomes, we combined data using the formula reported in Higgins 2011.

Studies with adjusted effect sizes

Where trials reported both unadjusted and adjusted effect sizes, we included only observed, unadjusted effect sizes.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing data, as we considered that the bias that would be introduced by doing this would outweigh any benefit of increased statistical power that may have been gained by including imputed data. However, where authors omitted standard deviations (SD) for continuous measures, we contacted corresponding authors to request missing data. Where missing data could not be provided, we calculated missing SDs using other data from the trial, such as CIs, based on methods outlined in Higgins 2019b.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Between‐study heterogeneity can be assessed using either the Chi² or I² statistics. However, in this review, we only used the I² statistic to quantify inconsistency, as this is considered to be more reliable (Deeks 2019). The I² statistic indicates the percentage of between‐study variation due to chance, and can take any value from 0% to 100% (Deeks 2019).

We used the following values to denote relative importance of heterogeneity, as per Deeks 2019:

unimportant: 0% to 40%;

moderate: 30% to 60%;

substantial: 50% to 90%;

considerable: 75% to 100%.

We also took the magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity into account (e.g. the CI for I²).

Where substantial levels of heterogeneity were found, we explored reasons for this heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity for details).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias occurs when the decision to publish a particular trial is influenced by the direction and significance of the results (Egger 1997). Research suggests, for example, that trials with statistically significant findings are more likely to be submitted for publication, and subsequently, be accepted for publication, leading to possible overestimation of the true treatment effect (Hopewell 2009).

To assess whether trials included in any meta‐analysis were affected by reporting bias, we planned to enter data into a funnel plot when a meta‐analysis includes results of at least 10 trials. Should evidence of any small study effects be identified, we planned to explore reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, including the presence of possible publication bias (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

For the purposes of this review, we calculated the pooled odds ratio (OR) and accompanying 95% CI using the random‐effects model, as this is the most appropriate model for incorporating heterogeneity between studies (Deeks 2019). We used the Mantel‐Haenszel method for dichotomous data, and the inverse variance method for continuous data. We conducted all analyses in Review Manager 5.4 (Review Manager 2020).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses

We planned to undertake the following subgroup analyses where there were sufficient data to do so:

sex (males versus females);

repeater status (first SH episode versus repeat SH episode).

Formal tests for subgroup differences were undertaken in Review Manager 5.4 (Review Manager 2020). However, it is only possible to undertake these subgroup analyses if randomisation was stratified by these factors, otherwise, there is the risk that doing so could lead to confounding. Given that randomisation was not stratified by these factors in the included studies, we found there were insufficient data to undertake these subgroup analyses in the current update.

Investigation of heterogeneity

Although no meta‐analysis was associated with substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity (i.e., I² ≥ 75%), in future updates, should any meta‐analysis be associated with substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity two review authors will firstly independently triple‐check data to ensure these were correctly entered. Assuming data were entered correctly, we will investigate the source of this heterogeneity using a formal statistical approach as outlined in Viechtbauer 2020.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake the following sensitivity analyses, where appropriate, to test whether key methodological factors or decisions may have influenced the main result.

Where a trial made use of Zelen's method of randomisation (see Unit of analysis issues).

Where a trial contributed to substantial between‐study heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

However, as no included trial made use of Zelen's method of randomisation, and furthermore, no meta‐analysis was associated with substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity, we were unable to undertake these sensitivity analyses.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

For each comparison we planned to construct a 'Summary of findings' table for our primary outcome measure, repetition of SH post‐intervention, following the recommendations outlined in Schünemann 2019. These tables provide information concerning the overall certainty of the evidence from all included trials that measured the outcome. We assessed the quality of evidence across the following domains.

'Risk of bias' assessment.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of effect estimates.

Potential publication bias.

For each of these domains, we downgraded the evidence from high certainty by one level (for serious) or by two levels (for very serious). For risk of bias, we downgraded this domain by one level when we rate any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for any of the studies included in the pooled estimate, or by two levels when we rate multiple studies at high risk for any of these sources. For indirectness of evidence, we considered the extent to which trials included in any meta‐analysis use proxy measures to ascertain repetition of SH; we downgraded this domain by one level if one study used proxy measures, and by two levels if multiple studies used proxy measures. For unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, we downgraded this domain by one level where the I² value indicated substantial levels of heterogeneity, or by two levels where the I² value indicated considerable levels of heterogeneity. For imprecision, we downgraded this domain by one level where the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value. Finally, for the potential publication bias domain, we considered any evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (if available), as well as other evidence such as suspected selective availability of data, and downgraded by one or more levels where publication bias was suspected.

We then used these domains to rate the overall certainty of evidence for the primary outcome according to the following.

High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate.

Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate.

Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2015).

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of the studies included in this review. Our recommendations for practice and research suggest priorities for future research, and outline the remaining uncertainties in the area.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

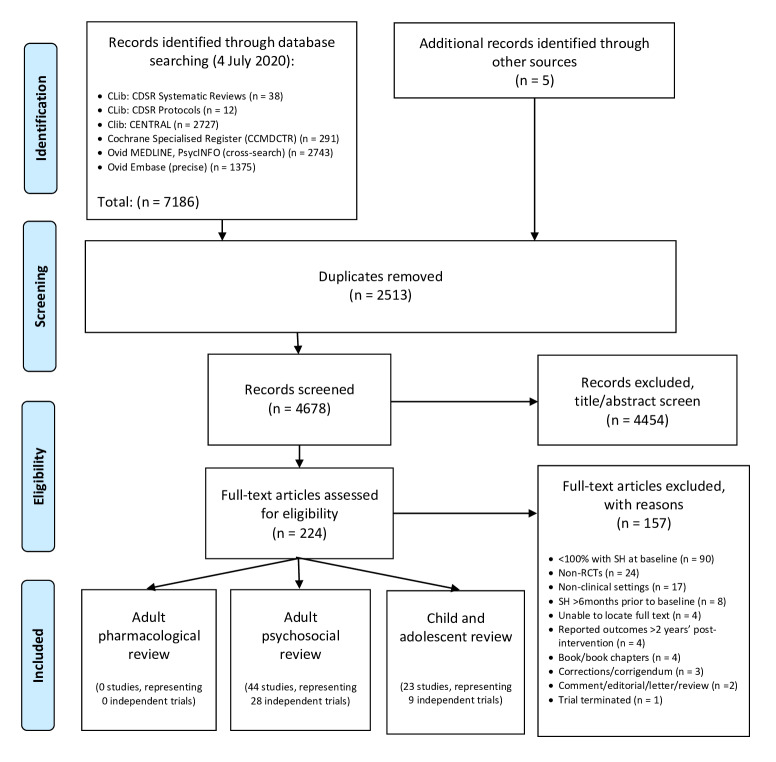

For this update, a total of 7186 records were found using the search strategy as outlined in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. Five further records were identified following correspondence and discussion with researchers in the field. After deduplication, the initial number was reduced to 4678. Of these, 4454 were excluded following title/abstract screening, whilst a further 157 were excluded after reviewing the full texts (Figure 1).

1.

Study Flow Diagram

Included studies

In the previous version of this review (Hawton 2015), seven trials of pharmacological interventions for self‐harm (SH) in adults were included. The present update did not locate any additional trials of pharmacological interventions or natural products for SH in adults. The present review therefore includes seven non‐overlapping trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). No further reports provided any additional data on these trials.

Two of these trials have not been published (Montgomery 1979; Hirsch 1982). Unpublished data were obtained from study authors for three of these trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998) (see the Characteristics of included studies tables for further information on these trials).

Design

Of these seven trials, five were placebo‐controlled RCTs (Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). The remaining two trials compared the effectiveness of the intervention agent to an active comparator drug/dose (Battaglia 1999; Montgomery 1979). All seven trials employed a simple randomisation procedure based on individual allocation to the intervention and comparator arms.

Setting

Of the seven independent RCTs included in this review, three were from the UK (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983), and one was from each of the USA (Battaglia 1999), Germany (Lauterbach 2008), the Netherlands (Verkes 1998), and the Republic of Ireland (Hallahan 2007).

Although all participants were identified following a hospital admission for SH, five trials did not clearly specify if treatment was delivered on an inpatient or outpatient basis. For the remaining two trials (Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998), participants were treated in outpatient settings.

Participants and participant characteristics

The included trials comprised a total of 574 participants. All had engaged in at least one episode of SH prior to trial entry. A history of SH prior to the index episode (i.e. a history of multiple episodes of SH) was a requirement for participation in five trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983).

Information on the methods of SH for the index episode was not reported in the majority of trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). In one trial, only those who had engaged in self‐poisoning (i.e, not illicit substances or poison) were eligible to participate (Hirsch 1982), whilst in the remaining trial (Lauterbach 2008), a variety of different methods were used, including: self‐poisoning (73.2%), self‐injury (14.4%), jumping from a height (2.5%), and attempted hanging, attempted shooting, or attempted drowning (5.0%). The methods used by the remaining 4.9% of participants in this trial were not reported. Whilst the predominance of participants engaging in self‐poisoning in these two trials is reflective of the typical pattern observed in those who present to hospital, in the community, SH more often involves self‐cutting and other forms of self‐injury (Müller 2016).

All trials included both male and female participants. Of the six trials that reported information on sex, the majority of participants were female (63.5%), reflecting the typical pattern for SH (Hawton 2008). Of the five trials that reported information on age, the weighted mean age of participants at trial entry was 35.3 years (standard (SD): 3.1 years). Two trials included a small number of adolescent participants (i.e. those under 18 years of age), but the precise number was not reported in either (Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982).

In the five trials that reported information on psychiatric diagnoses (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998), participants were most commonly diagnosed with major depression (34.5%), followed by any personality disorder (29.3%), and substance use disorder (24.8%). Around one‐in‐five (22.0%) were diagnosed with borderline personality disorder specifically. Information on comorbid diagnoses were reported in one trial (Lauterbach 2008). For this trial, the most common comorbidity was for any personality disorder (33.%), followed by substance use disorder (8.4%), and any anxiety disorder (7.2%). In a second trial (Verkes 1998), one‐quarter (25.3%) of the sample were diagnosed with more than one psychiatric disorder from the following: any anxiety disorder, any depressive disorder, dysthymia, any dissociative disorder, any adjustment disorder, and alcohol use disorder. However, the proportion diagnosed with each comorbid condition was not reported.

Interventions

The trials included in this review investigated the effectiveness of various pharmacological agents.

Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) versus placebo (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998).

Antipsychotics versus placebo (Montgomery 1979).

Antipsychotics versus another comparator drug/dose (Battaglia 1999).

Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics, versus placebo (Lauterbach 2008).

Natural products (omega‐3 essential fatty acid; n‐3EFA) versus placebo (Hallahan 2007).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

All trials reported data on the primary outcome of this review, repetition of SH. In two trials this was based on self‐reported information (Battaglia 1999; Lauterbach 2008), and in two further trials on re‐presentation to hospital (Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982). For the remaining three trials the source of information for this outcome was unclear (Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Hirsch 1982).

Secondary outcomes

Treatment acceptability

Treatment acceptability was measured as the proportion of participants that discontinued treatment for any reason in six trials (Battaglia 1999; Hirsch 1982; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998). For the remaining trial, only data on the proportion of participants that discontinued treatment due to the development of adverse effects was reported (Hallahan 2007).

Treatment adherence

Treatment adherence was assessed using pill counts in the two trials that reported data on this outcome (Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998).

Depression

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998) or the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS; Hamilton 1960) (Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008).

Hopelessness

Hopelessness was assessed using the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998).

General functioning

No trial reported data on general functioning.

Social functioning

No trial reported data on social functioning.

Suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation was assessed using the sub‐scale of the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS; Sorgi 1991) in one trial (Hallahan 2007), and the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) in one further trial (Lauterbach 2008).

Suicide

It was unclear how suicide was ascertained in any of the trials that reported data on this outcome.

Excluded studies

A total of 157 studies were excluded from this update. The most common reason for exclusion was that not all trial participants had engaged in SH within six months of trial entry (90 studies). Reasons for exclusion for the remaining studies are reported in Figure 1.

Details on the reasons for exclusion for those trials related to pharmacological interventions for SH in adults identified by this update are reported in the Characteristics of excluded studies section.

Ongoing studies

Of the two ongoing trials identified in the previous version of this review (Hawton 2015), one of oral lithium was subsequently terminated (NCT01928446), whilst the second, of oral ketamine, upon publication, did not meet inclusion criteria (Domany 2019). Two ongoing studies were identified in this update (see Characteristics of ongoing studies section for further information on these trials).

Studies awaiting classification

We identified one trial that is awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification section for further information on this trial).

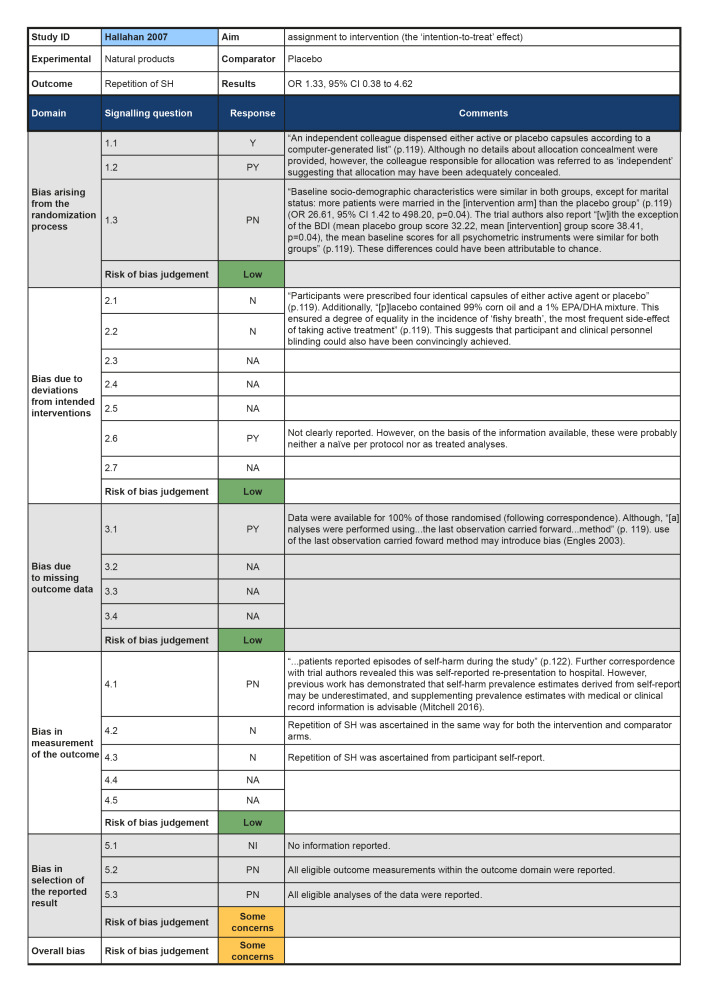

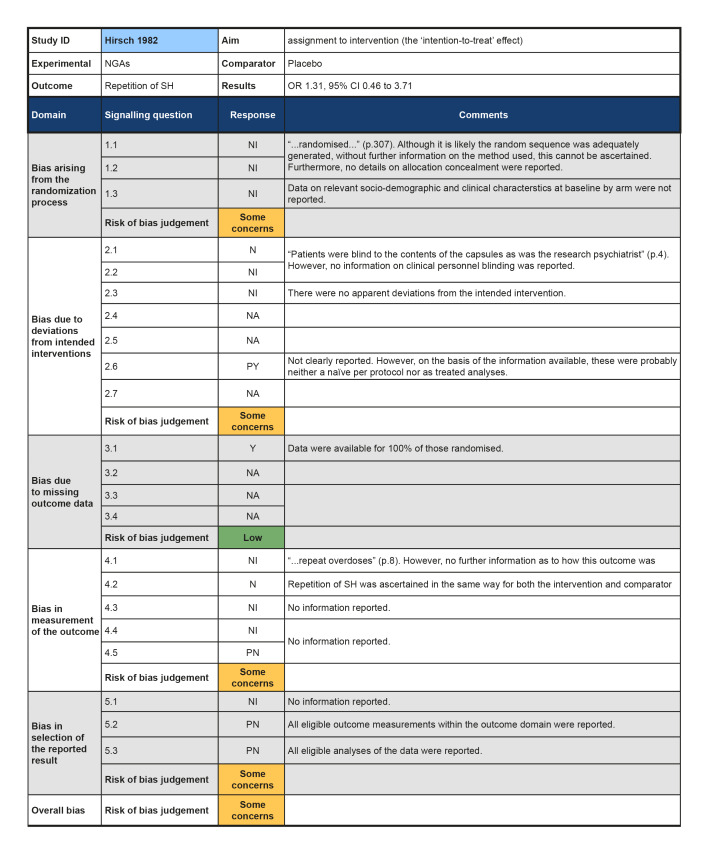

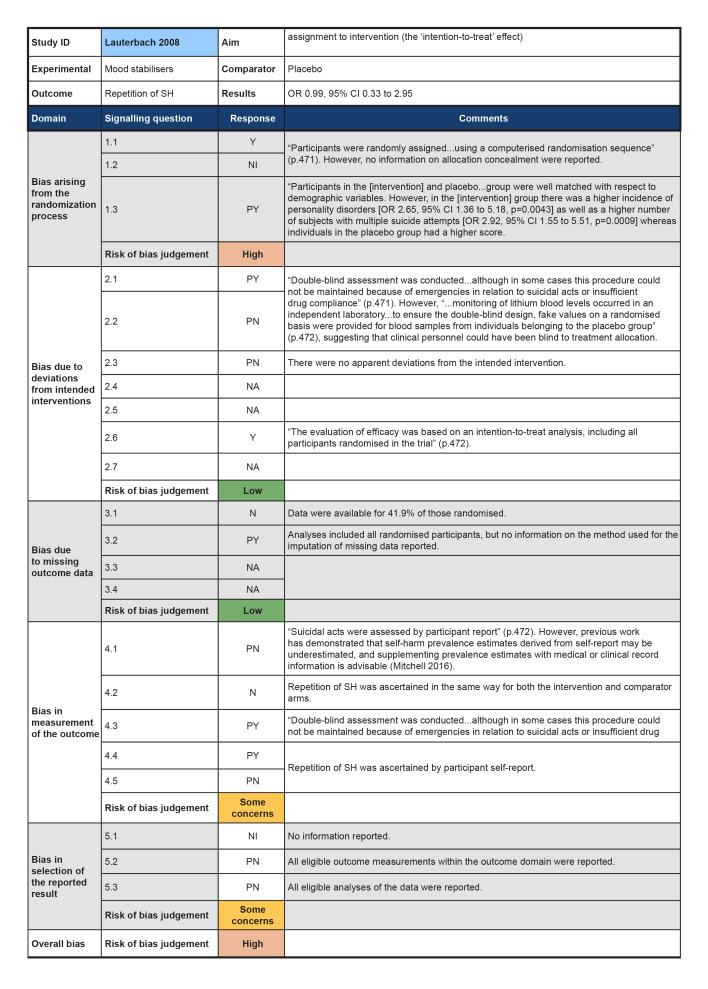

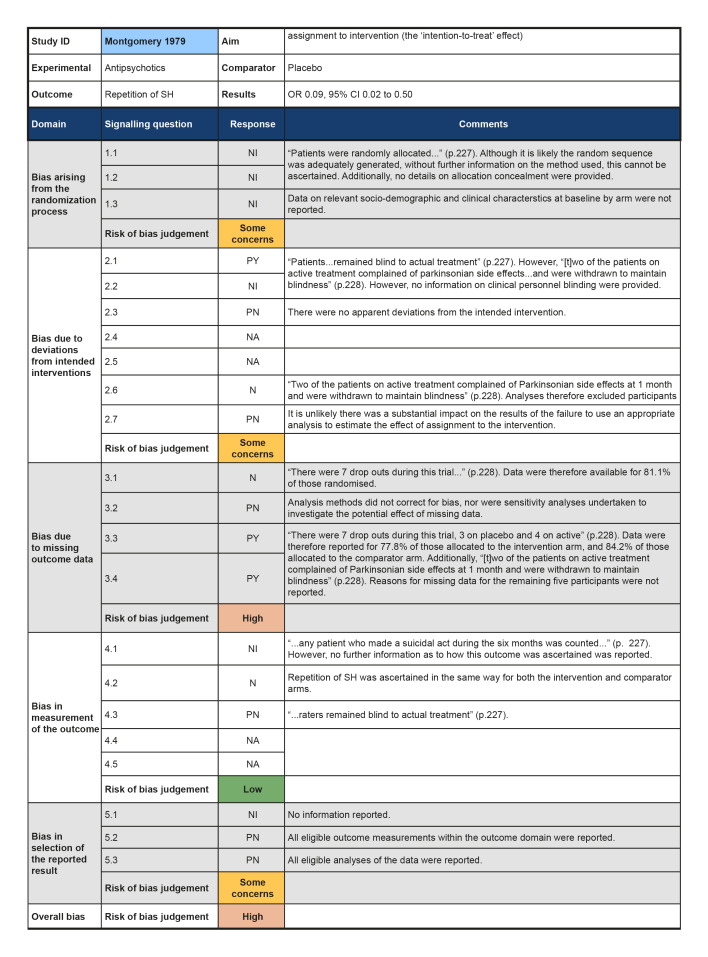

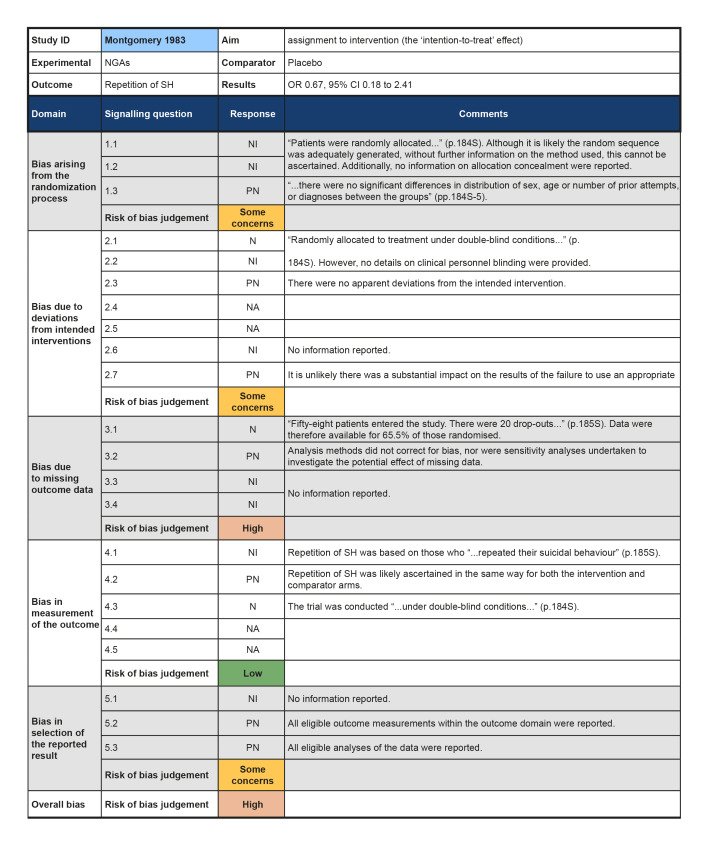

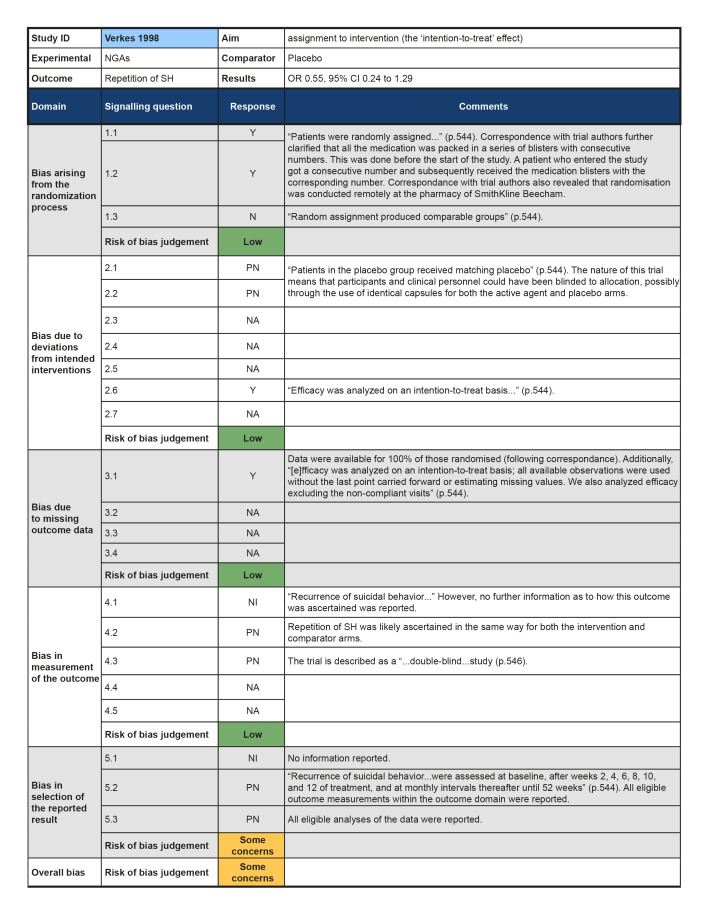

Risk of bias in included studies

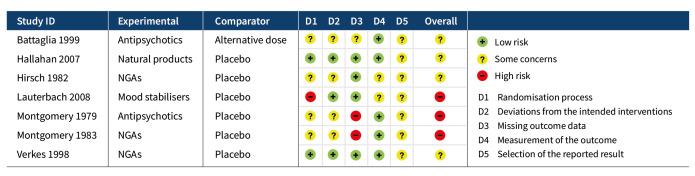

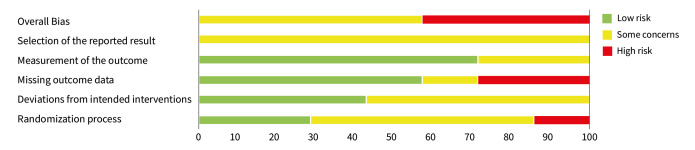

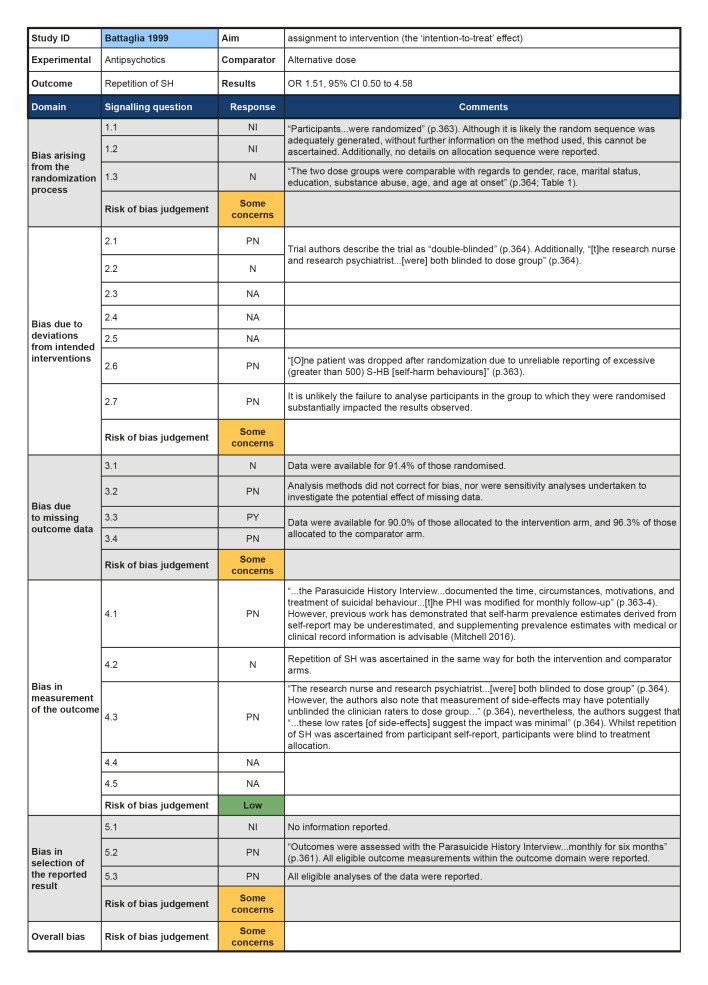

Risk of bias was evaluated for the primary outcome repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The results of the 'Risk of bias' assessments can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Full 'Risk of bias' assessments, including the evidence we used to justify our ratings, are available in Appendix 3.

2.

Results of 'Risk of bias' assessments for each study

3.

Summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments

Bias arising from randomisation process

Although all trials used random allocation to assign participants to the intervention and comparator arms, only two trials were rated as low risk of bias for this domain (Hallahan 2007; Verkes 1998). There were some concerns regarding bias arising from the randomisation process for over half (57.1%) of the trials included in this review. For some older trials, insufficient information on the method used to generate the randomisation sequence was reported. Additionally, no information on allocation concealment was reported in a number of these trials (Battaglia 1999; Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983). One trial was rated as high risk of bias for this domain (Lauterbach 2008). For this trial, a very significantly greater proportion of those assigned to the intervention arm were diagnosed with a personality disorder and had a history of multiple suicide attempts, whilst those assigned to the comparator arm had higher scores on the Suicide Intent Scale at baseline. Given these differences, there may have been a problem with the randomisation process.

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions

Three trials were rated as low risk of bias for this domain as participants and clinical personnel were blind to allocation, no deviations from the intended intervention were apparent, and analyses were conducted on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis (Hallahan 2007; Lauterbach 2008; Verkes 1998). For the remaining trials, either no specific information on participant and clinical personnel were reported (Hirsch 1982; Montgomery 1983), or analyses excluded eligible trial participants post‐intervention (Battaglia 1999; Montgomery 1979). These four trials (57.1%) were therefore rated as at some concerns for this domain.

Bias due to missing outcome data

Over half (57.1%) of the trials included in this review were at low risk of bias for those domain. One trial (14.3%) was rated as some concerns for this domain as greater than 5% of the data were missing at the post‐intervention assessment, there was some evidence of a larger proportion of missing data for the intervention arm as compared to the comparator arm, and further, sensitivity analyses were not undertaken to understand the impact missing data may have had on the estimate of treatment effectiveness (Battaglia 1999). Two trials (28.6%) were rated as high risk of bias for this domain as greater than 5% of the data were missing at the post‐intervention assessment and either no information on causes of missingness were reported, or alternatively, missingness may have been related to the development of side‐effects (Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983).

The majority of trials included in this review were rated as at low risk of bias for this outcome (71.4%). However, two trials were rated as some concerns for this domain; this was typically either because insufficient information was reported on how repetition of SH was ascertained (Hirsch 1982), or because repetition of SH was ascertained from self‐reported information and participant blinding was incomplete due to safety considerations (Lauterbach 2008).Bias in measurement of the outcome

Bias in selection of the reported result

All trials included in this review were rated as at some concerns for this domain as these trials had been published prior to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors' (ICMJE) requirement in 2015 that all trials be pre‐registered in a publicly available clinical trials registry. It was therefore difficult to determine whether data had been analysed according to a pre‐specified plan, although there were no apparent departures from the analyses outlined in the methods section of these trials (Battaglia 1999; Hallahan 2007; Hirsch 1982; Lauterbach 2008; Montgomery 1979; Montgomery 1983; Verkes 1998).

Overall bias

As a consequence, just under half of the trials (42.9%) included in this review were rated as at high risk of bias overall, whilst the remainder (57.1%) were rated as at some risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings 1. Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults.

| Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Self‐harm in adults Intervention: Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) | With Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) | Difference | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention (NGA class) № of participants: 129 (2 RCTs) | OR 0.59 (0.29 to 1.19) | Study population | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention. | ||

| 50.0% | 37.1% (22.5 to 54.3) | 12.9% fewer (27.5 fewer to 4.3 more) | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention (NGA class) ‐ Mianserin vs. Placebo № of participants: 38 (1 RCT) | OR 0.67 (0.18 to 2.41) | Study population | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention by NGA class (i.e., mianserin vs. placebo). | ||

| 57.1% | 47.2% (19.4 to 76.3) | 10.0% fewer (37.8 fewer to 19.1 more) | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention (NGA class) ‐ Paroxetine vs. Placebo № of participants: 91 (1 RCT) | OR 0.55 (0.24 to 1.29) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of the effect of newer generation antidepressants (NGAs) on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention by NGA class (paroxetine vs. placebo), and may change the estimate. | ||

| 46.7% | 32.5% (17.4 to 53) | 14.2% fewer (29.3 fewer to 6.4 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the trials included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain as these were relatively older agents and, in one trial, no information on how SH was ascertained was reported.

3 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 2. Antipsychotics compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults.

| Antipsychotics compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Self‐harm in adults Intervention: Antipsychotics Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without Antipsychotics | With Antipsychotics | Difference | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention № of participants: 30 (1 RCT) | OR 0.09 (0.02 to 0.50) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of the effect of antipsychotics as compared to placebo on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention, and may change the estimate. | ||

| 75.0% | 21.3% (5.7 to 60) | 53.7% fewer (69.3 fewer to 15 fewer) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the trials included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain as this was a relatively older agent and, for one trial, no information on how SH was ascertained was reported.

Summary of findings 3. Antipsychotics compared to another comparator drug or dose for self‐harm in adults.

| Antipsychotics compared to another comparator drug or dose for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Self‐harm in adults Intervention: Antipsychotics Comparison: Another comparator drug/dose | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without Antipsychotics | With Antipsychotics | Difference | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention № of participants: 53 (1 RCT) | OR 1.51 (0.50 to 4.58) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of the effect of antipsychotics as compared to another comparator drug or dose on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention, and may change the estimate. | ||

| 34.6% | 44.4% (20.9 to 70.8) | 9.8% more (13.7 fewer to 36.2 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain as this was a relatively older agent.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 4. Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults.

| Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Self‐harm in adults Intervention: Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium | With Mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium | Difference | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention № of participants: 167 (1 RCT) | OR 0.99 (0.33 to 2.95) | Study population | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of mood stabilisers, including antiepileptics and lithium, on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention. | ||

| 8.4% | 8.4% (2.9 to 21.4) | 0.1% fewer (5.5 fewer to 12.9 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the trials included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain as previous work has demonstrated that self‐harm prevalence estimates derived from self‐report may be underestimated, and supplementing prevalence estimates with medical or clinical record information is advisable (Mitchell 2016).

3 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 5. Natural products compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults.

| Natural products compared to placebo for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Self‐harm in adults Intervention: Natural products Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | ||

| Without Natural products | With Natural products | Difference | ||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention № of participants: 49 (1 RCT) | OR 1.33 (0.38 to 4.62) | Study population | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of the effect of natural products as compared to placebo on repetition of self‐harm by post‐intervention, and may change the estimate. | ||

| 25.9% | 31.8% (11.7 to 61.8) | 5.8% more (14.2 fewer to 35.9 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain as previous work has demonstrated that self‐harm prevalence estimates derived from self‐report may be underestimated, and supplementing prevalence estimates with medical or clinical record information is advisable (Mitchell 2016).

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Comparison 1: Tricyclic antidepressants versus placebo

There were no eligible trials in which tricyclic antidepressants were compared with placebo identified by this review.

Comparison 2: Tricyclic antidepressants versus another comparator drug or dose

There were no eligible trials in which tricyclic antidepressants were compared with another comparator drug or dose identified by this review.

Comparison 3: Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs)versus placebo

Three trials evaluated the effectiveness of different NGAs in adults (weighted mean age: 35.6 ± 6.8 years; 51.2% female) admitted to general hospitals following SH. The first compared 30 mg to 60mg mianserin or 75 mg to 150mg nomifensine against placebo (Hirsch 1982, N = 114), the second compared 30mg mianserin against placebo (Montgomery 1983, N = 58), and the third compared 40 mg paroxetine per day plus weekly/fortnightly supportive psychotherapy to placebo plus supportive psychotherapy (Verkes 1998, N = 91). We acknowledge that these antidepressants are from different drug classes (i.e. tetracyclic, atypical, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), respectively); however, we have combined results for these agents into one comparison in order to address the question of whether antidepressant treatment using NGAs might be of general benefit in this patient population. We have also subgrouped the individual agents in a post hoc analysis.

Primary outcome

3.1 Repetition of SH

While data from two trials did not show that NGAs may reduce risk of repetition of SH (23/63 versus 33/66; odds ratio (OR) 0.59, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.19; N = 129; k = 2; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.1), the direction of effect favoured NGAs over placebo but the pooled estimate was imprecise. However, the overall risk of bias was high for one trial (Montgomery 1979) and there were some concerns for the other trial (Verkes 1998). According to GRADE criteria, we judged the evidence to be of very low certainty.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs), Outcome 1: Repetition of SH by post‐intervention (NGA class)

There was also no evidence of an effect for mianserin or nomifensine at 12 weeks in a single trial (15/76 versus 6/38; OR 1.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.46 to 3.71; N = 114; k = 1; I² = not applicable).

A post‐hoc analysis was conducted combining data from all three of these trials at the final follow‐up assessment (i.e. 12 weeks for Hirsch 1982, six months for Montgomery 1983, and 12 months for Verkes 1998) in order to investigate whether there is any evidence of a difference by agent. To assess the efficacy of each agent, the intervention arms in Hirsch 1982 were separated into nomifensine versus placebo (n = 76) and mianserin versus placebo (n = 76) using the approach outlined in Higgins 2011. However, there was no evidence of a difference between agents (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 1.25, df = 2, P = 0.53, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs), Outcome 2: Repetition of SH at final follow‐up (by NGA class)

Secondary outcomes

3.2 Treatment acceptability

There was no evidence of an effect for NGAs on treatment acceptability in two trials (Analysis 1.3). In the third trial, just over one‐third (34.5%) of participants discontinued treatment; however, results were not disaggregated by trial arm (Montgomery 1983).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Newer generation antidepressants (NGAs), Outcome 3: Treatment acceptability

3.3 Treatment adherence

Data on treatment adherence was reported in one trial (Verkes 1998); however, no numerical data were provided. However, the trial authors report that "...analysis of capsule counts at each visit revealed no statistically significant differences between treatments" (p.545).

3.4 Depression

Two trials reported outcome data for depression (Hirsch 1982; Verkes 1998). Although mean scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale(HDRS) were reported in Hirsch 1982, insufficient information was provided to enable calculation of accompanying SDs via imputation. In Verkes 1998, no numerical data were provided. However, the trial authors report there was "...no significant treatment effect" for this outcome by the post‐intervention assessment (p.545).

3.5 Hopelessness

Information on hopelessness was reported in one trial (Verkes 1998). Once again, however, no numerical data were provided. However, the trial authors state there was also "...no significant treatment effect" for this outcome by the post‐intervention assessment (p.545).

3.6 General functioning

No data available.

3.7 Social functioning

No data available.

3.8 Suicidal ideation

No data available.

3.9 Suicide

Numbers of suicides were reported for two trials (Hirsch 1982; Verkes 1998). In the first, one suicide occurred in the placebo group by the post‐intervention period (Verkes 1998); however, there was no evidence of an effect for NGAs on suicide in this trial (0/46 versus 1/45; OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.04; N = 91; k = 1; I² = not applicable). In the second, no participant died by suicide by the six month follow‐up period (Hirsch 1982).

Subgroup analyses

No included trial stratified randomisation by sex or repeater status.

Sensitivity analyses

Not applicable.

Comparison 4: Newer generation antidepressants versus another comparator drug or dose

There were no eligible trials in which NGAs were compared with another comparator drug or dose identified by this review.