Abstract

Background

Perineal trauma is common during childbirth and may be painful. Contemporary maternity practice includes offering women numerous forms of pain relief, including the local application of cooling treatments. This Cochrane Review is an update of a review last updated in 2012.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of localised cooling treatments compared with no treatment, placebo, or other cooling treatments applied to the perineum for pain relief following perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (7 October 2019) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Published and unpublished randomised and quasi‐randomised trials (RCTs) that compared a localised cooling treatment applied to the perineum with no treatment, placebo, or another cooling treatment applied to relieve pain related to perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed study eligibility, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. Data were double checked for accuracy. The certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 10 RCTs that enrolled 1233 women randomised to the use of one cooling treatment (ice, cold gel pad, cooling plus compression, cooling plus compression plus (being) horizontal) compared with another cooling treatment, no treatment, or placebo (water pack, compression). The included trials were at low or uncertain risk of bias overall, with the exception that the inability to blind participants and personnel to group allocation meant that we rated all trials at unclear or high risk for this domain.

We undertook a number of comparisons to evaluate the different treatments.

Cooling treatment (ice pack or cold gel pad) versus no treatment

There was limited very low‐certainty evidence that cooling treatment may reduce women's self‐reported perineal pain within four to six hours (mean difference (MD) −4.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) −5.07 to −3.85 on a 10‐point scale; 1 study, 100 participants) or between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth (risk ratio (RR) 0.73, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.94; 1 study, 316 participants). The evidence is very uncertain about the various measures of wound healing, for example, wound edges gaping when inspected five days after giving birth (RR 2.56, 95% CI 0.58 to 11.33; 1 study, 315 participants). Women generally rated their satisfaction with perineal care similarly following cooling or no treatment. The potential exception was that there may be a trivially lower mean difference of −0.1 on a five‐point scale of psychospiritual comfort with cooling treatment, that is unlikely to be of clinical importance.

Cooling treatment (cold gel pad) + compression versus placebo (gel pad + compression)

There was limited low‐certainty evidence that there may be a trivial MD of −0.43 in pain on a 10‐point scale at 24 to 48 hours after giving birth (95% CI −0.73 to −0.13; 1 study, 250 participants) when a cooling treatment plus compression from a well‐secured perineal pad was compared with the placebo. Levels of perineal oedema may be similar for the two groups (low‐certainty evidence) and perineal bruising was not observed. There was low‐certainty evidence that women may rate their satisfaction as being slightly higher with perineal care in the cold gel pad and compression group (MD 0.88, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.38; 1 trial, 250 participants).

Cooling treatment (ice pack) versus placebo (water pack)

One study reported that no women reported pain after using an ice pack or a water pack when asked within 24 hours of giving birth. There was low‐certainty evidence that oedema may be similar for the two groups when assessed at four to six hours (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.86; 1 study, 63 participants) or within 24 hours of giving birth (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.59). No women were observed to have perineal bruising at these times. The trialists reported that no women in either group experienced any adverse effects on wound healing. There was very low‐certainty evidence that women may rate their views and experiences with the treatments similarly (for example, satisfied with treatment: RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.08; 63 participants).

Cooling treatment (ice pack) versus cooling treatment (cold gel pad)

The evidence is very uncertain about the effects of using ice packs or cold gel pads on women’s self‐rated perineal pain, on perineal bruising, or on perineal oedema at four to six hours or within 24 hours of giving birth. Perineal oedema may persist 24 to 48 hours after giving birth in women using the ice packs (RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.7; 2 trials, 264 participants; very low‐certainty). The risk of gaping wound edges five days after giving birth may be decreased in women who had used ice packs (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.01; 215 participants; very low‐certainty). However, this did not appear to persist to day 10 (RR 3.06, 95% CI 0.63 to 14.81; 214 participants). Women may rate their opinion of treatment less favourably following the use of ice packs five days after giving birth (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.68; 1 study, 49 participants) and when assessed on day 10 (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.92; 1 study, 208 participants), both very low‐certainty.

Authors' conclusions

There is limited very low‐certainty evidence that may support the use of cooling treatments, in the form or ice packs or cold gel pads, for the relief of perineal pain in the first two days following childbirth. It is likely that concurrent use of several treatments is required to adequately address this issue, including prescription and non‐prescription analgesia. Studies included in this review involved the use of cooling treatments for 10 to 20 minutes, and although no adverse effects were noted, these findings came from studies of relatively small numbers of women, or were not reported at all. The continued lack of high‐certainty evidence of the benefits of cooling treatments should be viewed with caution, and further well‐designed trials should be conducted.

Plain language summary

Local cooling for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth

We looked for evidence from randomised controlled trials on how effective localised cooling treatments are for reducing pain from damage to the area between the vagina and the anus, that is, 'perineal trauma', when giving birth.

What is the issue?

Perineal tears are common during childbirth. In addition, sometimes the person attending the birth cuts the perineum to give extra room for the baby to be born (an episiotomy).

These tears and cuts often cause pain and the mother may have difficulty walking or sitting comfortably, or to feed and care for her baby,

Why is this important?

The pain from perineal tears or cuts can decrease women’s ability to move around and causes discomfort when passing urine or faeces. This can affect her emotional well‐being. Persisting perineal pain can have longer‐term effects, such as pain during sex and problems with bowel movements and urination. Women are encouraged to use different ways to relieve the pain, including the use of cooling treatments such as ice packs or cold gel pads. It is important to know if cooling works and whether it can slow healing of the cut or tear.

This is an update of a review that was first published in 2007 and updated in 2012.

What evidence did we find?

We updated the search for evidence in October 2019. We have now found 10 randomised controlled trials to include. Nine of these studies had information from 998 women that we could use in the review.

Ice packs or cold gel pads were placed on the perineum for 10 to 20 minutes at a time in the first two days following childbirth. They were compared to no treatment (5 studies, 612 women) or placebo treatment of a gel pad (1 study) or a water bag (1 study), both at room temperature. Ice packs were compared with cold gel pads in three studies (338 women).

The trials were largely of very low quality due to concerns about how valid the findings were, with small numbers of women for each comparison, wide variations in treatment effects, and women knowing which treatment (or if no treatment) they had used. Few trials looked at the same comparisons or trials used different assessment tools or outcomes. Most of the findings come from single studies.

Women's self‐rated perineal pain following the use of the cold pad within six hours of giving birth may be less than for women who had no treatment (1 study, 100 women). There were no clear differences in self‐reported pain within 24 hours or up to 48 hours after giving birth (1 study, 316 women) or in perineal healing.

A cold gel pad with compression in comparison to a placebo may result in a very small reduction in pain 24 to 48 hours after giving birth (1 study, 250 women). Perineal wound healing may not be adversely affected by cooling. None of the women with an ice pack or a water pack at room temperature reported pain in the first 24 hours after giving birth (1 study, 63 women). No adverse effects on wound healing were reported.

Comparing ice packs with cold gel pads, there may be no difference in self‐rated perineal pain at any of the measurement times (3 studies, 338 women). One trial reported that fewer women using ice packs had gaping wound edges at day five but not at day 10 (215 women). In single studies, women rated their opinion of treatment less favourably with ice packs than with cold gel pads five days after giving birth (49 women) and when assessed on day 10 (208 women).

What does this mean?

There is only a small amount of low or very low‐quality evidence from small trials suggesting that cooling treatments may help relieve perineal pain after having a baby. Further research is needed to see if cooling affects how well the tears or cuts heal. Ice is readily available in high‐income countries but this may not be the case in low‐middle income countries. Gel pads that need to be placed in a freezer for cooling may also not be readily available in low‐middle income areas.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Cooling treatment (ice pack or cold gel pad) compared to no treatment for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

| Cooling treatment (ice pack or cold gel pad) compared to no treatment for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women with perineal trauma (tear or episiotomy, or both) sustained during childbirth Setting: Brazil, Iran, Turkey, United Kingdom Intervention: cooling treatment (ice pack or cold gel pad) Comparison: no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no treatment | Risk with cooling treatment (ice pack or cold gel pad) | |||||

| Perineal pain within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal pain within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth was 6.42 | MD 4.46 lower (5.07 lower to 3.85 lower) | ‐ | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,c | Scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth ‐ Moderate + severe pain | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.82 to 1.29) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | ‐ | |

| 515 per 1000 | 530 per 1000 (422 to 664) | |||||

| Perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth was 4.05 | MD 0.41 lower (1.78 lower to 0.95 higher) | ‐ | 166 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,e,f,g | Scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal pain between 24 ‐ 48 after giving birth ‐ Moderate + severe pain | Study population | RR 0.73 (0.57 to 0.94) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | ‐ | |

| 535 per 1000 | 390 per 1000 (305 to 503) | |||||

| Perineal pain 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth | The mean perineal pain between 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth was 4.36 | MD 0.53 lower (1.45 lower to 0.39 higher) | ‐ | 71 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,f,g | Scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal oedema within 24 hours of giving birth | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.87 to 1.16) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d,g | ‐ | |

| 723 per 1000 | 723 per 1000 (629 to 838) | |||||

| Perineal bruising within 24 hours of giving birth | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.81 to 1.19) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d,g | ‐ | |

| 604 per 1000 | 592 per 1000 (489 to 719) | |||||

| Perineal bruising 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth | Study population | RR 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32) | 316 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d,g | ‐ | |

| 673 per 1000 | 761 per 1000 (653 to 889) | |||||

| Perineal redness, oedema, bruising, discharge, wound gaping 24 ‐ 48 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal redness, oedema, bruising, discharge, wound gaping between 24‐48 hours of giving birth was 2.89 | MD 1.19 lower (2.07 lower to 0.31 lower) | ‐ | 71 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,e,h,i | The REEDA scale provides a rating of Redness, Edema, Ecchymosis (bruising), Discharge & Approximation (of skin edges): range 0 to 15, with higher scores representing increased tissue trauma |

| Adverse effects on perineal wound healing: Day 5 ‐ Wound not healing | Study population | RR 1.24 (0.34 to 4.58) | 315 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | ‐ | |

| 30 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (10 to 137) | |||||

| Adverse effects on perineal wound healing: Day 5 ‐ Wound edges gaping | Study population | RR 2.56 (0.58 to 11.33) | 315 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | ‐ | |

| 20 per 1000 | 51 per 1000 (12 to 227) | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences of treatment ‐ Satisfaction with overall perineal care (good + very good + excellent) Day 10 | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.97 to 1.18) | 308 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d | ‐ | |

| 840 per 1000 | 899 per 1000 (815 to 991) | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences of treatment ‐ Psychospiritual comfort within 6 hours of giving birth | The mean maternal views and experiences of treatment ‐ Psychospiritual comfort within 6 hours of giving birth was 1.97 | MD 0.1 lower (0.2 lower to 0.0) | ‐ | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,j | Scale of 1 (low comfort) to 5 (high comfort) |

| Maternal views and experiences of treatment ‐ Sociocultural comfort | The mean maternal views and experiences of treatment ‐ Sociocultural comfort was 2.94 | MD 0.01 higher (0.09 lower to 0.11 higher) | ‐ | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,j | Scale of 1 (low comfort) to 5 (high comfort) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for unblinding of outcome assessors. bDowngraded one level due to uncertainty about selection bias. cDowngraded one level for imprecision: unequal variance intervention vs no intervention. dDowngraded two levels for very serious limitations due to incomplete outcome data. eDowngraded one level for risk of selection bias. fDowngraded one level for risk of selective reporting. gDowngraded one level due for imprecision: confidence intervals crossing line of no effect. hDowngraded one level for possible unblinding of outcome assessors. iDowngraded one level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals). jDowngraded one level for imprecision: trivial difference (less than one point on a 5‐point scale).

Summary of findings 2. Cooling treatment (cold gel pad)+compression compared to placebo (gel pad+compression) for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

| Cooling treatment (cold gel pad)+compression compared to placebo (gel pad+compression) for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women with perineal trauma (tear or episiotomy, or both) sustained during childbirth Setting: Thailand Intervention: cooling treatment (cold gel pad)+compression Comparison: placebo (gel pad+compression) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo (gel pad+compression) | Risk with cooling treatment (cold gel pad)+compression | |||||

| Perineal pain within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal pain within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth was 3.15 | MD 0.32 lower (0.78 lower to 0.14 higher) | ‐ | 250 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | A scale of zero (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal pain within 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth | The mean perineal pain within 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth was 2.48 | MD 0.43 lower (0.73 lower to 0.13 lower) | ‐ | 250 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWc | A scale of zero (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal oedema 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth | The mean perineal oedema 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth was 0.176 | MD 0.15 lower (0.28 lower to 0.03 lower) | ‐ | 250 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,d | Scale zero: none ‐ 3: > 2 cm |

| Perineal bruising 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth | ‐ | 250 (1 RCT) | ‐ | No women were observed to have perineal bruising | ||

| Adverse effects | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No trials reported on adverse effects | ||

| Satisfaction with perineal care | The mean satisfaction with perineal care was 6.87 | MD 0.88 higher (0.38 higher to 1.38 higher) | ‐ | 250 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,c | Scale of zero (not satisfied) to 10 (most satisfied) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for unblinding of outcome assessors. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision: wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. cDowngraded one level for imprecision: trivial difference on a 10‐point scale. dDowngraded one level for imprecision: trivial difference on a 3‐point scale.

Summary of findings 3. Cooling treatment (ice pack) compared to placebo (water pack) for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

| Cooling treatment (ice pack) compared to placebo (water pack) for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women with perineal trauma (tear or episiotomy, or both) sustained during childbirth Setting: Brazil Intervention: cooling treatment (ice pack) Comparison: placebo (water pack) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo (water pack) | Risk with cooling treatment (ice pack) | |||||

| Perineal pain within 24 hours after giving birth | Study population | ‐ | 63 (1 RCT) | ‐ | No participants reported perineal pain within this time frame | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Perineal oedema within 4 ‐ 6 hours after giving birth | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.50 to 1.86) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ | |

| 371 per 1000 | 357 per 1000 (186 to 691) | |||||

| Perineal oedema within 24 hours after giving birth | Study population | RR 0.36 (0.08 to 1.59) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ | |

| 200 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (16 to 318) | |||||

| Adverse effects on perineal healing | Study population | ‐ | 63 (1 RCT) | ‐ | No adverse events were reported by participants or observed by outcome assessors | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences with treatment ‐ Satisfied with treatment | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWb,c,d | ‐ | |

| 943 per 1000 | 858 per 1000 (726 to 1000) | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences with treatment ‐ Would repeat treatment in future childbirth | Study population | RR 0.88 (0.75 to 1.04) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWb,c,d | ‐ | |

| 971 per 1000 | 855 per 1000 (729 to 1000) | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences with treatment ‐ Would recommend treatment | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.77 to 1.03) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWb,c,d | ‐ | |

| 1000 per 1000 | 890 per 1000 (770 to 1000) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision: wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. bDowngraded one level for small sample size. cDowngraded one level due to unblinding of outcome assessor. dDowngraded one level for imprecision: confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect.

Summary of findings 4. Cooling treatment (ice pack) compared to cooling treatment (cold gel pad) for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

| Cooling treatment (ice pack) compared to cooling treatment (cold gel pad) for relieving pain from perineal trauma sustained during childbirth | ||||||

| Patient or population: Women with perineal trauma (tear or episiotomy, or both) sustained during childbirth Setting: Iran, United Kingdom Intervention: cooling treatment (ice pack) Comparison: cooling treatment (cold gel pad) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with cooling treatment (cold gel pad) | Risk with cooling treatment (ice pack) | |||||

| Perineal pain within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth ‐ Moderate + severe pain | Study population | RR 0.57 (0.26 to 1.24) | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,c,d | ‐ | |

| 481 per 1000 | 274 per 1000 (125 to 597) | |||||

| Perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth ‐ Moderate + severe pain | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.78 to 1.22) | 264 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,e | ‐ | |

| 541 per 1000 | 530 per 1000 (422 to 660) | |||||

| Perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth was 3.84 | MD 0.58 higher (0.44 lower to 1.6 higher) | ‐ | 74 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d,f,g | Scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal pain 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth ‐ Moderate + severe pain | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.89 to 1.65) | 263 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,c | ‐ | |

| 343 per 1000 | 415 per 1000 (306 to 566) | |||||

| Perineal pain 24 ‐ 48 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal pain between 24‐48 hours of giving birth was 2.97 | MD 0.86 higher (0.1 lower to 1.82 higher) | ‐ | 74 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,c,d,f | Scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) |

| Perineal oedema within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth | Study population | RR 1.39 (0.93 to 2.09) | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,c,d | ‐ | |

| 556 per 1000 | 772 per 1000 (517 to 1000) | |||||

| Perineal oedema within 24 hours of giving birth | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.84 to 1.13) | 264 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,e | ‐ | |

| 733 per 1000 | 711 per 1000 (616 to 829) | |||||

| Perineal oedema 24 ‐ 48 hours after giving birth | Study population | RR 1.69 (1.03 to 2.77) | 264 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,h | ‐ | |

| 393 per 1000 | 663 per 1000 (404 to 1000) | |||||

| Perineal bruising within 4 ‐ 6 hours of giving birth | Study population | RR 1.23 (0.51 to 2.97) | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,d,h | ‐ | |

| 259 per 1000 | 319 per 1000 (132 to 770) | |||||

| Perineal bruising within 24 hours of giving birth | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.79 to 1.14) | 264 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 5 | ‐ | |

| 644 per 1000 | 612 per 1000 (509 to 735) | |||||

| Perineal redness, oedema, bruising, discharge, wound gaping within 24 hours of giving birth | The mean perineal redness, oedema, bruising, discharge, wound gaping within 24 hours of giving birth was 2.3 | MD 0.13 lower (0.85 lower to 0.59 higher) | ‐ | 74 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,d,e | The REEDA scale assesses 5 aspects of wound healing: redness, (o)edema, ecchymosis (bruising), discharge and (wound edge) approximation on a scale of 0 (best) to 3 (worst) for each component for a maximum score of 15 |

| Adverse effects on perineal wound healing: Day 5 ‐ Wound not healing | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.26 to 3.93) | 215 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,c | ‐ | |

| 37 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (10 to 146) | |||||

| Adverse effects on perineal wound healing: Day 5 ‐ Wound edges gaping | Study population | RR 0.22 (0.05 to 1.01) | 215 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,h | ‐ | |

| 83 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (4 to 84) | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences with treatment ‐ Opinion on treatment effects (good + very good + excellent) Day 5 | Study population | RR 0.33 (0.17 to 0.68) | 49 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b,d | ‐ | |

| 815 per 1000 | 269 per 1000 (139 to 554) | |||||

| Maternal views and experiences with treatment ‐ Satisfaction with overall perineal care (good + very good + excellent) Day 10 | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.73 to 0.92) | 208 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ‐ | |

| 934 per 1000 | 766 per 1000 (682 to 859) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for unblinding of outcome assessors. bDowngraded two levels for very serious limitations due to incomplete outcome data. cDowngraded one level due to imprecision: wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect. dDowngraded one level for small sample size. eDowngraded one level due for imprecision: confidence intervals crossing line of no effect. fDowngraded one level for risk of selective reporting. gDowngraded one level for imprecision: trivial difference on a 10‐point scale. hDowngraded one level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals).

Background

Description of the condition

Perineal trauma: effects and prevention

Perineal trauma, whether by episiotomy (cutting of the perineum to enlarge the vaginal orifice during the end of the second stage of birthing) or from naturally‐occurring tears, is common during childbirth. In Australia in 2018, 55% of women sustained tears and 23% had an episiotomy (AIHW 2020). In the United Kingdom, 22% of women having a vaginal birth undergo episiotomy and 3.5% sustain third‐ or fourth‐degree tears (NMPA 2019), while average pooled estimated episiotomy rates in low‐middle income countries are 46% (95% confidence interval 35% to 55%), ranging from 10% in Cameroon to 98% in Pakistan (Aguiar 2019). The combination of spontaneous tears and episiotomy therefore encompasses a large proportion of women who sustain perineal trauma with a vaginal birth (Abedzadeh‐Kalahroudi 2019). Further sources of trauma include vaginal lacerations and trauma to the external genitalia (labia, clitoris, periurethra) (Wen 2018).

In the hours, days and months following childbirth, this trauma may be painful (East 2011; Francisco 2011; Manresa 2019) and can be increased in women with deeper trauma (> 2 cm) (Lawrence 2017). This pain can result in decreased mobility and increased discomfort with passing urine or faeces (Subki 2019), may negatively impact on the woman's ability to care for her new baby (East 2011) and affect emotional well‐being (Shoorab 2019). Perineal pain that persists beyond the immediate postpartum period may warrant further evaluation and may have longer‐term effects, such as sexual and pelvic dysfunction (Doğan 2017; Manresa 2019). A number of risk factors for severe perineal trauma have been identified, with some debate remaining. These generally include primiparity, ethnicity, with women from Southern Asia and Africa being at greater risk than others, instrumental birth, and prolonged length of second stage (for example, over two hours) (Davies‐Tuck 2015; Gibson‐Helm 2015).

A number of techniques may be applied for the prevention or minimisation of perineal trauma (Aasheim 2017), which may subsequently reduce the perineal pain associated with childbirth. Possible preventive or minimisation measures include perineal massage during pregnancy, application of warm packs to the perineum during second stage, mediolateral versus midline episiotomy, and birthing attendants' hands on the perineum during the birth of the baby's head, to name a few (Aasheim 2017). Selective use of episiotomy, for example, in situations where severe perineal trauma would otherwise occur, or for fetal indications, results in less severe perineal trauma (Jiang 2017). It remains unclear whether or not women's self‐reported perineal pain is influenced by the routine or selected use of episiotomy (Jiang 2017).

Analgesia for perineal trauma

When perineal trauma does occur, regardless of the underlying contributing factors or interventions, pain, where present, requires attention. Contemporary maternity practice includes offering the woman numerous forms of pain relief, often used in combination. Several Cochrane Reviews have considered the evidence of the effectiveness of treatments used in recent decades. These include: methods and materials used for suturing perineal tears or episiotomies (Kettle 2010; Kettle 2012); topically‐applied anaesthetics (for example, lignocaine) and a topical preparation of pramoxine/hydrocortisone (Hedayati 2005); orally or rectally administered non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) (Hedayati 2003; Wuytack 2016); ultrasound (Hay‐Smith 1998); and other oral medications such as aspirin (Molakatalla 2017) or paracetamol/acetaminophen (Chou 2013). While these treatments demonstrate varying levels of success in relieving pain from perineal trauma, they may also involve a degree of cost to the consumer, the health service, or both. Paracetamol and NSAIDS are considered safe in breastfeeding (Bisson 2019), while potentially harmful side effects of these and other medications also need to be considered. Women's satisfaction is also an important consideration of any treatment used for reducing perineal pain, although this is poorly studied (Molakatalla 2017; Wuytack 2016).

A safe, effective, low‐cost alternative, available in primary healthcare settings as well as in hospitals, and that is acceptable to childbearing women, would be attractive. The use of cryotherapy (cooling treatment) in the form of ice packs or cold gel pads, may be one such alternative.

Description of the intervention

Cooling therapy for pain relief

Cooling to reduce inflammation and provide short‐term relief of pain from localised tissue trauma has been used for over four decades (Ernst 1994; McMasters 1977), particularly for the treatment of delayed‐onset muscle soreness (DOMS), sports trauma and following surgery (Adie 2010; Martimbianco 2014; Nogueira 2019; Oakley 2013; Torres 2012; Van den Bekerom 2012). Such cryotherapy may be in the form of local application of crushed ice or frozen gel, through to whole‐body cryotherapy (WBC) or cold‐water immersion (CWI) (Bleakley 2010). A common approach, attributed to Mirkin 1978, is to incorporate cooling within a ‘bundle’ of care, typically referred to as “RICE”, involving Rest, local application of Ice, along with Compression and Elevation of the region.

Cooling treatments for perineal pain relief following childbirth have traditionally been applied intermittently in a number of ways, including: (i) solid or crushed ice applied directly to the perineum or between layers of a pad (Grant 1989; Leventhal 2010); (ii) a cold gel pack applied to the perineum (Leventhal 2010; Steen 1999); or (iii) bathing in iced water (Grant 1989).

How the intervention might work

The potential effects of cooling on wound healing

Bonica’s theory (Bonica 1990) explains the physiology of local tissue injury and the potential effect of cold therapy. The accumulation of fluid (swelling/oedema) in an inflamed, injured area occurs due to increased permeability of the dilated peripheral blood vessels. When cold is applied, the skin blood supply is reduced. In turn, reduced tissue swelling and bleeding may also reduce bruising and localised pain. The effectiveness of this theory is supported by a systematic review showing that cryotherapy substantially reduces oedema following acute trauma (Collins 2008).

Pain signalling, inflammation and vascular changes are influenced by several biochemical mediators. These include serotonin, histamine and kinins. Serotonin dilates capillaries, increases vascular permeability and contracts non‐vascular smooth muscle. Actions of histamine include increased capillary permeability, arteriolar dilation and contraction of non‐vascular smooth muscle, while kinins increase vascular permeability and vasodilation. Any mechanism that reduces these vascular responses will also reduce the effect of the mediator(s) (Dray 1995). Reducing soft tissue temperature by 10 to 15 degrees Celsius decreases local cell metabolism, reduces the oxygen requirement of the tissue and causes constriction of the peripheral blood vessels (Mac Auley 2001). Heat‐activated receptors are thought to play a significant role in inflammation‐related pain (Kettle 2012; Reid 2005). White 2013 concluded that metabolic rate and blood flow is reliably affected by tissue cooling. The use of a cooling treatment for between five and 15 minutes lowers the skin temperature and reduces swelling, thus providing analgesia (Bleakley 2012; Kuo 2013; Leventhal 2010; Machado 2016; Malanga 2015; White 2013).

White 2013 also states that although metabolic rate and blood flow seem to be reliably affected by cold, further studies are needed to investigate a dose‐dependence.

Can cooling delay wound healing or pose safety concerns?

Concern about the safety and potential harm of ice has long been considered. This debate has arisen again, triggered in part by Mirkin 2015 using his online blog to debunk his original design of the clinical tool of RICE, published in his seminal textbook (Mirkin 1978). Dubois 2020 recently created a new approach for the management of soft tissue injury which suggests avoiding the use of ice therapy and anti‐inflammatory medication due to the disruption in the inflammatory process and the potential negative effect on soft tissue repair. Inflammation and muscle regeneration are closely interconnected through complex interactions which in acute conditions are beneficial to muscle healing (Dushesne 2017). The theory may or may not translate to actual harms. An experimental randomised controlled trial showed that although cryotherapy effectively reduced inflammation mechanisms it did not negatively alter regeneration markers or collagen deposition (Ramos 2016), while in humans, icing was found to disrupt inflammation and some aspects of revascularisation in acutely‐injured skeletal muscle but showed no substantial negative effect on muscle growth (Singh 2017). There appears to be no reported ‘harm’ from cooling to muscle function, but it was shown that it does not accelerate muscle recovery following exercise‐induced muscle damage (Engelhard 2019).

Other potential risks of ice therapies include nerve palsies and ice burns. Beyond the desired localised/short‐term numbing effect, true nerve palsies are more likely to occur at bony joints where there are exposed nerve areas (knee/elbow) or after prolonged, extreme temperature cooling as seen with WBC and CWI (Lubkowska 2012; Swenson 1996). Dosage recommendations for local ice therapy were originally described, limiting exposure to 10‐minute sessions intermittently, to avoid skin damage (Mac Auley 2001). This along with other application care relevant to the injured area will further eliminate the risk of ice burns.

Why it is important to do this review

Cooling to relieve pain following childbirth‐related perineal trauma, although lacking in supporting evidence, has been and continues to be commonly used in clinical practice for over 30 years (NICE 2006; Queensland Clinical Guidelines 2018; Sleep 1988). The ongoing conflicting evidence on the efficacy of cooling treatments is complicated further by the emerging debate on potential harm such therapies may cause when used to treat sports injuries or surgical wounds, and needs to be considered for the perineal region as related to childbirth. The acceptability to women of any cooling therapy needs to be evaluated. This systematic review will provide childbearing women and their caregivers with updated evidence to inform clinical practice. This Cochrane Review is a further update of a review first published in 2007 and updated in 2012.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of localised cooling treatments compared with no treatment, placebo, or other cooling treatments applied to the perineum for pain relief following perineal trauma sustained during childbirth.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised and quasi‐randomised trials that compared localised cooling treatment(s) applied to the perineum with no treatment, placebo treatment, or another cooling treatment applied to the perineum to relieve pain related to perineal trauma sustained during childbirth. We excluded cross‐over studies. We were able to confirm that all of the reports that were available in abstract form were also linked with later‐published full trial reports. If we identify any other abstracts in future updates, we will include them if they contain sufficient information to assess study eligibility and risk of bias, and if the authors confirm in writing that they reported final results that would not change in subsequent publications.

Types of participants

Women with perineal trauma (tear or episiotomy, or both) sustained during childbirth.

Types of interventions

Application of localised cooling treatment to the perineum, versus no treatment, placebo treatment or another form of cooling treatment.

Types of outcome measures

We are aware of two publications: (i) a generic protocol for the systematic review of drugs used to relieve perineal pain in the early postpartum period (Chou 2009); and (ii) the WHO postnatal care guideline summary (personal communication, L Jones 11 December 2019), that have highlighted the outcomes to be considered when consolidating guidance for safe and effective interventions during the postnatal care of mothers and babies. We have revised the outcomes in this update to align with those in these two publications where possible (see Differences between protocol and review).

Primary outcomes

(1) Perineal pain, as measured by the trial authors, for example, using a visual analogue scale, at the following time periods (or as close to the time period as possible):

within four to six hours of giving birth;

within 24 hours of giving birth;

between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth.

Secondary outcomes

(2) Perineal pain, as measured by the trial authors, for example, using a visual analogue scale, associated with activities of daily living (for example, sitting, walking, urinating, caring for baby) at the following time periods (or as close to the time period as possible):

within four to six hours of giving birth;

within 24 hours of giving birth;

between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth.

(3) Perineal oedema, as measured by the study authors, at the following time periods (or as close to the time period as possible):

within four to six hours of giving birth;

within 24 hours of giving birth;

between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth.

(4) Perineal bruising, as measured by the study authors, at the following time periods (or as close to the time period as possible):

within four to six hours of giving birth;

within 24 hours of giving birth;

between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth.

(5) Additional analgesia for relief of perineal pain:

within 24 hours of giving birth;

between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth.

(6) Adverse effects on perineal healing, such as infection or wound breakdown, as measured by the study authors.

(7) Maternal exhaustion, as measured by the study authors, at the following time periods (or as close to the time period as possible):

within four to six hours of giving birth;

within 24 hours of giving birth;

between 24 and 48 hours of giving birth.

(8) Maternal views and experiences with treatment, using a validated instrument or as otherwise measured by the study authors.

(9) Women providing any breast milk to the baby 24 to 48 hours after giving birth (via the breast or as expressed breast milk).

(10) Cost of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (7 October 2019).

The Register is a database containing over 25,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification;.

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (7 October 2019), using the search methods detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We sought ongoing and unpublished trials by contacting experts in the field.

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see East 2012.

For this update, we used the following methods for assessing the reports that we identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Original review and 2012 update: two review authors (Christine East (CE), Naomi Henshall (NH), or Karen Wallace (KW)) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We planned to resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we would consult a third person (NH, KW, Lisa Begg or Paul Marchant).

2020 update: CE, Jiajia (Jessie) Liu (JL) and Emma Dorward (ED) assessed the previously‐included studies for the updated criteria and the newly‐identified studies for inclusion. We planned to resolve any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we would consult a third person (Rhiannon Whale (RW)).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, at least two review authors (2007 and 2012: CE, NH, KW, LB, PM, or JL; 2020: CE, JL, ED) extracted the data using the agreed form. We planned to resolve discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we would consult a third person from within the authorship. We double‐checked a sub‐sample of these data against the Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014).

When information on any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (2007 and 2012: CE, NH, KW, LB, PM, or JL; 2020: CE, JL, ED) independently assessed risks of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020a). We planned to resolve any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor from within the authorship.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random‐number table; computer random‐number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assess the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively‐numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes; alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

We planned to consider excluding studies with over 20% missing data unless there were good reasons to include them, based on other assessments of their risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020a). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as a summary risk ratio with a 95% confidence interval.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different scales.

We analysed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. If in the original reports participants were not analysed in the group to which they were randomised, and there was sufficient information in the trial report, we planned to attempt to restore them to the group to which they had been randomised.

The trials reported assessments of pain, oedema and bruising at different time periods and by different criteria, necessitating the use of judgement by the review authors when selecting which assessment would most closely represent our stated outcome measures. We selected the assessment closest to the upper end of the timeframe specified in our outcomes. Where pain was reported as "any" or by degrees, we selected a total of the ratings, for example, moderate, severe and unbearable.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. If we identify suitable trials in future updates, we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020b) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Other unit‐of‐analysis issues

For this updated review, we adopted the approach recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020b) to overcome a unit‐of‐analysis error for studies that could contribute multiple, correlated comparisons. Where data were reported in three groups (intervention one, intervention two, no treatment) we combined data for the intervention groups (cold gel pads and ice packs) where this was possible with the available data (Steen 2000; Steen 2002) for the comparison with no treatment. The continuous data reported by Navvabi 2009 did not allow for this: given that in previous versions of this review, we had not identified evidence of differences in outcomes when comparing one or other of these treatments (East 2012), we elected to report only the cold gel pad data and compared this with no treatment.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were to be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau2, I2 and Chi2 statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I2 was greater than 30% and either Tau2 was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi2 test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are 10 or more studies in a future meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it. Such analyses may include inflated measures of effect related to poor methodological quality or small sample size (Higgins 2020a).

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). We used a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials examined the same intervention, and we judged the trials’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials.

Where we used random‐effects analyses, we present the results as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau2 and I2.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it. We considered whether there was clinical heterogeneity and if so, how this aligned with the PICO characteristics.

For fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analyses, we planned to assess differences between subgroups by interaction tests. For random‐effects and fixed‐effect meta‐analyses using methods other than inverse variance, we assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses on the primary outcome for the one trial for which these data were available (Steen 2002):

parity (primiparity, multiparity);

mode of birth (spontaneous vaginal birth, assisted vaginal birth (forceps, vacuum))

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis to explore the potential effect of risks of bias for the very few outcomes that had more than one study contributing data, as had been undertaken in earlier versions of this review. In line with contemporary methodology, we will only undertake sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes if trials that report these are included in a future update and require such analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

For this update we assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE handbook, in order to assess the certainty of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparisons of:

Cooling treatment (ice pack or cold gel pad) versus no treatment;

Cooling treatment (cold gel pad) + compression versus placebo (gel pad + compression);

Cooling treatment (ice pack) versus placebo (water pack);

Cooling treatment (ice pack) versus cooling treatment (cold gel pad).

for the following outcomes:

Perineal pain within four to six hours of giving birth;

Perineal pain within 24 hours of giving birth;

Perineal pain between 24 to 48 hours after giving birth;

Perineal oedema within 24 hours of giving birth;

Perineal bruising within 24 hours of giving birth;

Adverse effects on perineal healing;

Maternal views and experiences with treatment.

We did not generate 'Summary of findings' tables for the subgroups, given that only one trial contributed to these.

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of certainty for each of the above outcomes, using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high certainty' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

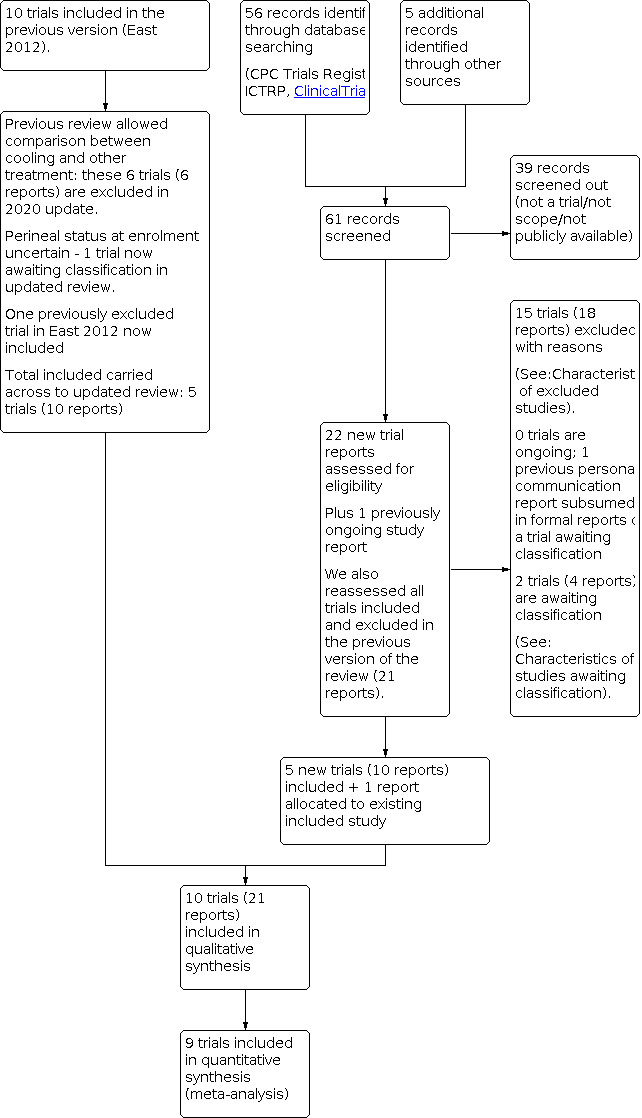

See: Figure 1.

1.

ReStudy flow diagram.

The searches for this update yielded 63 records. After screening out 41 records, there were 22 new reports. We also reassessed the 22 trial reports from the previous version of the review to meet eligibility for the fewer objectives in this update; recognition that a previously‐included study enrolled women without perineal trauma; and that a study previously excluded on the grounds of quality concerns was eligible for inclusion.

We included 10 trials (21 reports) and excluded 15 trials (18 reports). There are two trials awaiting classification (four reports), as the authors have not been able to provide detail to allow for analysis of only those women with perineal trauma (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). The one ongoing study in the previous version of the review was a personal communication about the trial that is now awaiting classification. We did not identify any new ongoing studies.

Included studies

We included 10 studies (Barclay 1983; Beleza 2017; East 2007; Francisco 2018; Morais 2016; Navvabi 2009; Senol 2017; Steen 2000; Steen 2002; Yusamran 2007) that enrolled 1233 women randomised to the use of one cooling treatment (ice, cold gel pad, cooling plus compression, cooling plus compression plus (being) horizontal) compared with another cooling treatment, with no treatment, or with placebo (water pack, compression). The report by Barclay 1983 did not present any outcome data in a format that could be included in the review, while others had substantial rates of attrition (see below), giving a total of 998 women contributing data to the primary outcome of perineal pain and to various of the secondary outcomes. Few trials used the same comparisons, assessment tools or outcomes. We therefore conducted five comparisons, each with between one and three trials contributing data to the continuous or dichotomous outcomes (see below). We used descriptive categories within the analyses to provide adequate detail for the reader. See Characteristics of included studies.

Design

The included studies were all randomised controlled trials.

Sample sizes

One study was a pilot to test feasibility for a larger planned trial and enrolled 16 women (East 2007). The remaining studies enrolled between 20 and 50 per treatment group (Barclay 1983; Beleza 2017; Francisco 2018; Morais 2016; Navvabi 2009; Senol 2017; Steen 2000), while two studies enrolled 125 or 150 women to each group (Steen 2002; Yusamran 2007 respectively). Of note, two studies (Steen 2000; Steen 2002) suffered considerable attrition with non‐return of completed paperwork by the clinicians (see Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Setting

Studies were conducted in the birthing centres, or birthing suites or postnatal wards of hospitals, and continued to community care in Australia (Barclay 1983; East 2007), Brazil (Beleza 2017; Francisco 2018; Morais 2016), Iran (Navvabi 2009), Thailand (Yusamran 2007), Turkey (Senol 2017) and the United Kingdom (Steen 2000; Steen 2002).

Participants

Healthy primiparous or multiparous women of childbearing age with a singleton pregnancy and cephalic presentation who gave birth vaginally around term gestation were invited to participate. Some studies only included women with a normal vaginal birth (Morais 2016; Navvabi 2009), enrolled women who had an instrumental birth (Steen 2000), included both normal and assisted (vacuum or forceps) vaginal births (Beleza 2017; East 2007; Steen 2002) or did not specify mode of vaginal birth (Barclay 1983; Senol 2017; Yusamran 2007). For some studies, a minimum level of perineal trauma (second degree tear, Steen 2002) or an episiotomy were criteria for study entry (Barclay 1983; Beleza 2017; Navvabi 2009; Steen 2000; Steen 2002; Yusamran 2007), while for three studies, lesser levels of perineal trauma or even an intact perineum could qualify a woman for study entry: given that our prespecified inclusion criteria did not allow for an intact perineum, we contacted study authors to obtain data for women with some trauma; relevant data were made available by East 2007, Francisco 2018 and Morais 2016.

The authors of Senol 2017 confirmed the numbers of primiparous and multiparous women in each group and had reported data by parity: although the published report indicated that all the primiparous women had an episiotomy, detail later provided from the authors indicated that one primipara in each group had an intact perineum. We elected to retain the data in this review rather than remove them and suffer the delays in obtaining data for only the 98 women, given the potentially unlikely impact that only omitting outcomes from 2% of participants would have on the findings. Data for the 79% of multiparous women who had perineal trauma (tear or episiotomy) were not available separately from the full sample for inclusion in this version of the review.

No studies enrolled women with severe perineal trauma, i.e. third‐ or fourth‐degree laceration, as this requires more specialised treatment.

Interventions and comparisons

Cooling treatments

Ice packs were commonly used. These could be in the form of a plastic bag or a latex medical glove filled with crushed ice or filled with water then frozen, or commercially‐available packs that would be soaked in water and frozen (Beleza 2017; East 2007; Francisco 2018; Morais 2016; Navvabi 2009; Steen 2000; Steen 2002). Cold gel pads that could be placed in a freezer came in a variety of forms, from those designed specifically for the studies (Steen 2000; Steen 2002), which were commercialised and incorporated into the trial by Navvabi 2009 or the use of a commercially‐available heat/cold pack (Senol 2017; Yusamran 2007). In one study cooling was provided in the form of a "cold sitz bath" whereby ice and salt were added to a bowl of water (Barclay 1983). The addition of compression (East 2007; Sheikhan 2011) and lying horizontally for a short time (East 2007) meant that the cooling treatment was part of a bundle of care, akin to the RICE principles. An overview of the cooling treatments is provided in Table 5. Four trials compared outcomes when one cooling therapy was compared with another therapy or regimen. For example, Navvabi 2009; Steen 2000 and Steen 2002 compared the use of ice packs and cold gel pads; East 2007 compared regular application of ice packs along with compression and being horizontal, compared with ad hoc ice pack usage.

1. Summary of cooling methods and results.

| Study | Form of cooling | Additional technique | 1st application post‐birth | Length of application | Frequency | Perineal temperature | Assessment of perineal pain | Adverse effects on perineal healing |

| Iced sitz bath | ||||||||

| Barclay 1983 | 30 g salt added to 1 ‐ 2 litres cold tap water (~ 7 °C) + ice | immersion | Day 1 | 10 minutes | 3 ‐ 4 a day | not assessed | post‐treatment ‐ days 1 ‐ 5 |

not assessed |

| Ice packs | ||||||||

| Beleza 2017 | 15 cm bag filled with 150 g crushed ice | wrapped in thin cotton tissue |

within 24 hours: average of 15 hours |

20 minutes | single application | pre‐ application: 34.5 °C post‐application ‐ 10 minutes: 20.5 °C ‐ 20 minutes: 23.4 °C ‐ 1 hour: 33.8 °C |

pre‐application post‐application ‐20 minutes ‐60 minutes |

not reported |

| East 2007 | commercial product (Medichill, USA) soaked in water then frozen | within perineal pad | birth suite | 20 minutes | 2 ‐ 3 hourly for 2 ‐ 3 days |

not assessed | post‐application ‐ within 24 hours ‐ 24 ‐ 48 hours |

no women had adverse effects |

| Francisco 2018 | plastic pack filled with 250 mL water and placed in freezer – removed in the form of ice | wrapped in thin cotton gauze applied to the perineum – participant lying down |

meant of 12.7 hours after birthing; rooming‐in unit, birth centre | 10 minutes | single application | pre‐application of ice (intact and perineal trauma): mean 33.8 °C post‐application ‐ immediately after: mean 15.6 °C ‐ 2 hours later: mean 34.1 °C |

pre‐application ‐ immediately after intervention ‐ 2 hours later |

adverse effects not recorded |

| Morais 2016 | latex glove, crushed ice | wrapped in sterile wet gauze |

2 hours | 20 minutes | 6 applications at 6‐hourly intervals | reduction by 10‐15 °C at 10 ‐ 20 minutes of application |

pre‐application post application ‐ immediately ‐ 24 hours |

no women had adverse effects |

| Navvabi 2009 | “ice pack” | no detail | within 4 hours after episiotomy repair | no detail | single application | not assessed | post‐application ‐ 4 hours ‐ days 1 ‐ 2 ‐ day 5 ‐ day 10 |

wound approximation is part of REEDA scale – not able to access separate result but no between‐group differences in overall scale with other groups. |

| Steen 2000 | saline sachets frozen, for 2 hours |

in sterile gauze cover | within 4 hours after suturing |

Unpublished information from the authors noted that gel pad groups took 20 minutes to warm to perineal temperature, compared with ice packs, which melted more quickly. | as per women’s preferences for 48 hours (mean number of applications 10.4, SD 4.3) |

‐ | post‐application ‐ 0 ‐ 4 hours ‐ day 1 ‐ day 2 |

wound healing and closure of wound edges assessed days 5 and 10: findings not reported |

| Steen 2002 | saline sachets frozen, for 2 hours |

in sterile gauze cover | within 4 hours after suturing |

not described | as per women’s preferences for 4 days. Day/Median/Range 1 5 0 ‐ 8 2 26 0 ‐ 8 3 4 0 ‐ 10 4 2 0 ‐ 14 |

not assessed | pre‐application post‐application ‐ days 1‐5 ‐ day 10 ‐ day 14 |

wound healing and closure of wound edges assessed days 5, 10 and 14: low prevalence and wide confidence intervals |

| Gel pads | ||||||||

| Navvabi 2009 | gel pad (Femepad, Florri‐Femé Pharmaceuticals Ltd, UK) with “antifreeze” gel | freeze for 2 hours prior to app |

within 4 hours of episiotomy repair |

not assessed | Initial application then as per women’s preferences for 10 days | not assessed | post‐application ‐ 4 hours ‐ days 1‐2 ‐ day 5 ‐ day 10 |

wound approximation is part of REEDA scale – not able to access separate result, however, no evidence of between‐group differences in overall scale. |

| Senol 2017 | ThermoGEL, freezer 1 hour: −10 °C once in form of ice | wrapped sterile “pad” |

2 hours post‐birth | 20 minutes | at 2 hours and 6 hours | post‐1st application 24.4 (SD 0.72) °C post‐2nd application 25.5 (SD 0.61) °C |

2 hours after each application | no women had adverse effects |

| Steen 2000 | gel pad, propylene glycol (anti‐freeze), frozen for 2 hours | sterile gauze covers | within 4 hours after suturing | Unpublished information from the authors noted that gel pad groups took 20 minutes to warm to perineal temperature, compared with ice packs, which melted more quickly | as per women’s preferences for 48 hours (mean 84, SD 5.0 applications) |

not assessed | post‐application ‐ 0 ‐ 4 hours ‐ day 1 ‐ day 2 |

wound healing and closure of wound edges assessed days 5 and 10: findings not reported |

| Steen 2002 | gel pad, propylene glycol (anti‐freeze), frozen for 2 hours | sterile gauze covers | within 4 hours after suturing | not described | as per women’s preferences for 4 days. Day/Median/Range 1 20 0 ‐ 12 2 36 0 ‐ 14 3 5 0 ‐ 13 4 2 0 ‐ 14 |

not assessed | pre‐application post‐application ‐ days 1 ‐ 5 ‐ day 10 ‐ day 14 |

wound healing and closure of wound edges assessed days 5, 10 and 14: low prevalence and wide confidence intervals |

| Yusamran 2007 | adapted commercially‐available gel pack (3M Thailand Ltd) to suit perineum (11 x 9 cm), placed in 4 °C fridge‐freezer | designed cotton pack to insert gel pad and support sanitary pad – attached loops to suspend it | ‐ | 15 minutes to maintain pad temperate of 4 ‐ 12.8 °C 2 hours |

replaced every 15 minutes for 2 hours | not assessed | pre‐ and post each application in the 2 hours, then at 48 hours | wound approximation included in the overall REEDA score |

°C – degrees Celsius; cm – centimetres; hr – hour(s); REEDA score – redness, (o)edema, ecchymosis, discharge, (wound edge) approximation; SD – standard deviation

Control/no treatment or placebo groups

Control or no‐treatment groups involved 'routine' care, described by some as involving regular hygiene, use of a sanitary pad or analgesia or both on request (Barclay 1983; Beleza 2017; Senol 2017, Steen 2002). Placebo care was included in the form of a latex glove filled with water at 20 °C to 25 °C (Morais 2016) or a gel pad and compression (Yusamran 2007). Cooling treatments were therefore compared with no treatment or with the placebo.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

All included studies reported women's self‐rated perineal pain at one or more of the prespecified times of between four and six hours after giving birth, within the first 24 hours of giving birth or between 24 to 48 hours after giving birth. A scale of zero (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) was used by Beleza 2017; Francisco 2018; Navvabi 2009; Senol 2017 and Yusamran 2007, or 1 (no pain) to 5 (severe pain, Barclay 1983). The remaining trialists reported data as none, mild, moderate, or severe (East 2007; Morais 2016 (converted from a numeric scale: 0 to 5 none/mild or 6 to 10 moderate/severe); Steen 2000; Steen 2002). Results of pain ratings in Barclay 1983 were only available in graphical form; as the authors were unable to be provide numeric data, this study did not contribute data for this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

No studies reported on all the prespecified secondary outcomes. Perineal pain that interfered with activities of daily living was reported for some or all of sitting, walking, urinating and caring for the baby by East 2007; Senol 2017 and Steen 2002; perineal oedema and bruising were reported by Navvabi 2009; Senol 2017; Steen 2002 and Yusamran 2007. The use of additional analgesia was evaluated by East 2007; Morais 2016 and Steen 2002; while Morais 2016 and Steen 2002 reported on women providing any breast milk to their babies. Few trials reported on adverse effects of cooling, no treatment or placebo on perineal healing (Morais 2016; Senol 2017). Maternal exhaustion was reported in the form of maternal energy level in one study (East 2007) and women's views of their experience with perineal care was provided by Morais 2016; Senol 2017; Steen 2002 and Yusamran 2007. No studies conducted an economic analysis.

Timeframes

The studies were conducted across more than three decades, from the 1980s (implied for Barclay 1983), 1993 to 1994 and 1998 to 1999 for Steen 2000; Steen 2002 respectively, from 2005 to 2006 (Navvabi 2009; Yusamran 2007), 2007 to 2008 (Beleza 2017), 2008 to 2009 (East 2007) and between 2012 and 2013 (Francisco 2018; Morais 2016; Senol 2017).

Sources of funding

Funding sources were detailed in six reports (Beleza 2017; Francisco 2018; Morais 2016; Navvabi 2009; Steen 2000; Steen 2002). Lack of funding meant that the full study proposed by East 2007 did not proceed.

Declarations of interest