Abstract

Myofibrillar myopathies (MFMs) are a group of heterogeneous muscle disorders morphologically defined by the presence of foci of dissolution of the myofibrils, accumulation of the products of myofibrillar degradation and ectopic expression of multiple proteins. MFMs represent the paradigm of conformational protein diseases of skeletal and cardiac muscles. Protein aggregation in MFMs is now considered to be the result of a failure of the extralysosomal proteolytic degradation system. Several factors including mutant proteins, aggresome formation and oxidative stress may compromise the ubiquitin–proteasome system, promoting the accumulation of potentially toxic protein aggregates within muscle cells.

Keywords: myofibrillar myopathies, proteasome system, protein aggregates, ubiquitin, neuron‐restrictive silencer factors

INTRODUCTION

Proper protein folding is an essential post‐translation process for correct protein function. Newly synthesized proteins must fold into their correct three‐dimensional structure and maintain these native states throughout their life. Several factors, including gene mutations, post‐translational modifications, oxidative stress, among others, may induce an abnormal change in protein conformation. Protein quality control systems are therefore necessary to help cells to cope with these conformationally abnormal proteins. Molecular chaperones represent the first line of defense against protein misfolding and aggregation, and allow protein repair or refolding. When chaperones fail to repair, they send the altered protein to be degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS), or by the hsp 70 chaperone‐mediated autophagy. If the activity of these two systems is impaired, macroautophagy is the only system that is able to remove those toxic protein complexes. When even autophagy is not able to remove the altered proteins, these aggregates often entrap other still‐functional proteins inside the cell 16, 23, 32, 36, 77.

Intracellular accumulation of altered or misfolded proteins is the basis of many neurodegenerative disorders generically known as protein conformational disorders 8, 15, 16, 55, 67, and is now also considered to play an important pathogenetic role in an expanding group of muscle disorders collectively called protein aggregate myopathies (PAMs) 28, 29. Myofibrillar myopathies (MFMs), representing the largest group of PAMs, are a group of heterogeneous muscle diseases having as a common feature the presence of focal dissolution of the myofibrils, accumulation of the products of myofibrillar degradation and ectopic expression of multiple proteins 14, 44, 64. MFMs have been associated with mutations in several protein components of the Z‐disk including desmin 30, 31, 43, αB‐crystallin (73), myotilin 45, 62, ZASP (63), filamin C (74) and BAG3 (65). Protein aggregates in MFMs are composed of a wide variety of proteins 14, 17, 44, 64. Some of them are normal constituents of the myofibrils; however, many nonspecific muscle proteins are aberrantly expressed in muscle fibers as well. Protein aggregation in MFMs is now considered to be the result of a failure of proteolytic degradation systems of cells and not of increased synthesis 17, 18, 28, 29. Several factors, including mutant proteins, oxidative stress and aggresome formation, among others, are thought to compromise the UPS, and maybe autophagy as well, facilitating the accumulation of large potentially toxic protein aggregates that ultimately result in muscle fiber degeneration. In this review, we summarize the mechanisms contributing to defective extralysosomal protein degradation in MFMs.

Protein composition of aggregates in MFMs

As stated earlier, intracytoplasmic accumulation of insoluble protein aggregates in muscle cells constitutes a major morphological hallmark of MFMs. Besides the respective mutant protein in each subgroup of MFMs (ie, desmin in desminopathies, αB‐crystallin in αB‐crystallinopathies, myotilin in myotilinopathies), protein aggregates in MFM are enriched with a wide variety of proteins. These include ubiquitin, phosphorylated neurofilaments, tau, β‐amyloid, plectin, gelsolin, syncoilin, synemin, caveolin, dysferlin, heat shock proteins, α1‐antichymotrypsin and many others, suggesting that mutant proteins facilitate the entrapment of other proteins within the muscle cells (14, 44, 64 reviewed in 17) (1, 2).

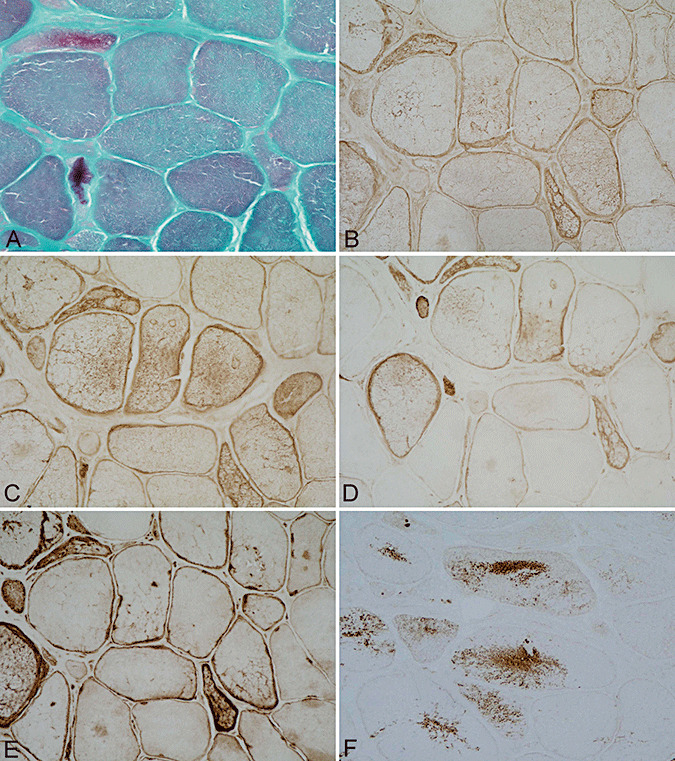

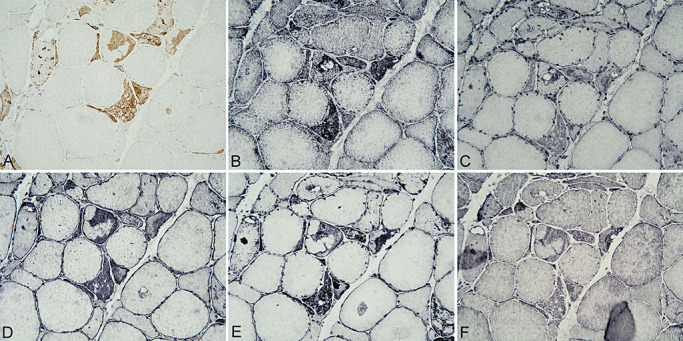

Figure 1.

Muscle biopsy from a patient carrying a Pro419Ser desmin mutation. Increased variation in muscle fiber diameters and mild endomysial fibrosis, modified Gomori's trichrome stain (A). Abnormal fiber areas show accumulation of desmin (B), αB‐crystallin (C), phosphorylated neurofilaments as revealed with BF‐10 (D) and SMI‐31 (E) antibodies. Nonserial section showing aberrant synaptophysin expression (F). A–F ×200.

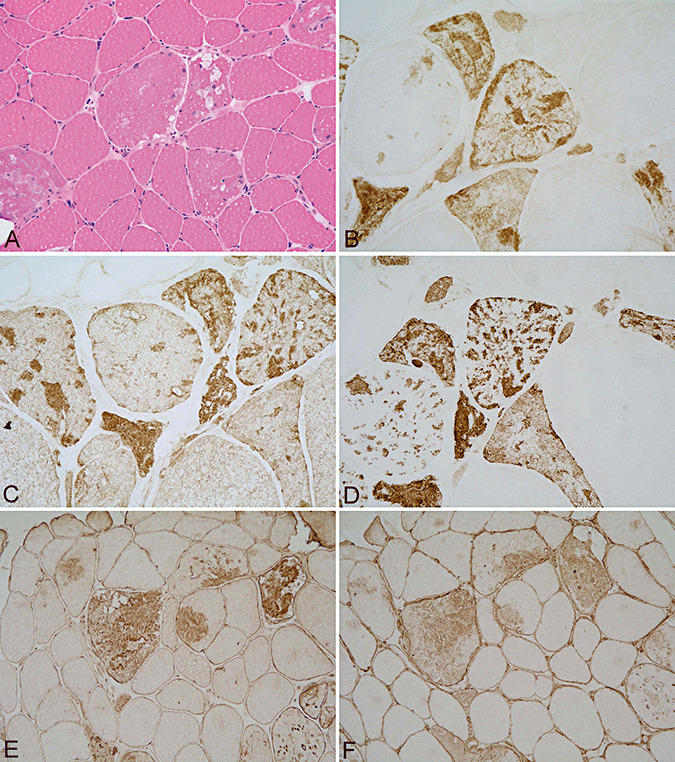

Figure 2.

Muscle biopsy with increased variation in muscle fiber diameters and vacuoles within few muscle fibers, hematoxylin–eosin (A), from a patient with a Ser55Phe myotilin mutation showing prominent protein aggregates containing myotilin (B), filamin C (C), phosphorylated neurofilaments (D), UCHL‐1 (E) and α‐internexin (F). A, E and F ×200; B–D ×400.

Genes coding for most of the proteins found accumulated in myofibers in MFMs are not up‐regulated compared to controls 47, 52, thus suggesting that protein aggregates are not the result of increased protein synthesis. Rather, they are the result of post‐translational modifications of proteins that render them resistant to the protein degradation systems of muscle cells.

The role of the UPS

The UPS is responsible for the selective degradation or recycling of short‐lived intracellular and nuclear proteins 23, 27, 37. Misfolded proteins or unassembled subunits of larger protein complexes and retro‐translocated proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum are also subject to proteasomal degradation. Targeted proteins must become conjugated to a polyubiquitin chain to be recognized by the proteasome. Ubiquitin conjugation is a highly ordered process. In the first step, a ubiquitin activation enzyme E1 activates and transfers ubiquitin to one substrate‐dependent ubiquitin‐conjugating enzyme, E2. Ubiquitin is then transferred to a member of the ubiquitin ligase family, E3. This is followed by poly‐ubiquitination of the substrate, produced via a series of isopeptide linkages between a lysine residue of the attached ubiquitin and the carboxyl‐terminal glycine of the next ubiquitin molecule 23, 27, 37, 70. In addition to ubiquitylating enzymes, additional factors including deubiquitylating enzymes, shuttling factors and chaperones are involved in presenting substrates to the proteasome for degradation (70).

The 20S proteasome is organized into a structure resembling a hollow cylinder composed of four stacked rings, each composed of seven subunits. The catalytic β‐subunits are located in the inner two rings, while the gated α‐subunits are located in the outer two rings. The 20S proteasome can associate, in the presence of ATP, with two caps or 19S complexes that bind to the outer rings of the 20S complex, thus forming the 26S proteasome complex. The 20S proteasome has three main peptidase activities: chymotrypsin‐like, trypsin‐like and peptidylglutamyl peptide hydrolyzing activities 27, 70.

The 20S proteasome can also bind to the PA28α/β activator to form the PA28‐proteasome complex, which appears to increase antigen processing. In the presence of certain stimuli, the β‐subunits of the 20S proteasome are replaced by homologous proteins, called LMP2, LMP7 and MECL1, forming the immunoproteasome. Hybrid proteasomes formed by 19S, 20S and PA28 are involved in the immune response 27, 32.

Protein aggregates in MFM are often ubiquitinated, suggesting involvement of the UPS. Yet, several proteasome subunits are abnormally expressed in muscle fibers in MFM as revealed by immunohistochemistry and Western blotting (18). Subunits of the 20S, 19S and PA28 colocalize with ubiquitin and other proteins, including desmin, αB‐crystallin, gelsolin and phospho‐tau, in abnormal protein aggregates in myotilinopathies (Figure 3). Moreover, fibers with protein aggregates express LMP2, LMP7 and MECL1(18). This is accompanied by preserved or even increased proteolytic activity in vitro in myotilinopathies (18).

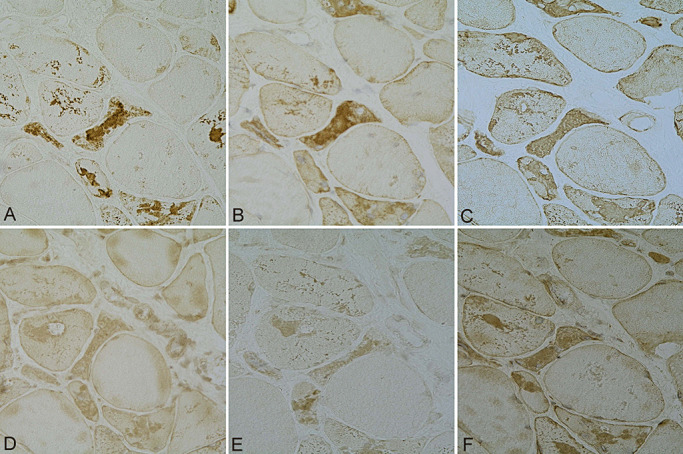

Figure 3.

Colocalization of ubiquitin (A), αB‐crystallin (B), desmin (C) and 20S (D), 19S (E) and PA28 (F) components of the proteasome in muscle fibers in myotilinopathy. A–F ×200.

Studies in heart muscle from a transgenic mouse model of desminopathy have also demonstrated over‐expression of the 20S subunit and down‐regulation of the 19S subunit of the proteasome together with increased peptidase activity 39, 40.

These observations strongly suggest that abnormalities of the UPS in MFMs are not the result of defective peptidase activity per se, but rather respond to a failure in the entry of large ubiquitinated protein inclusions into the narrow barrel of the proteasome's proteolytic core.

Abnormal proteasomal expression and activity do not fully explain why several proteins cluster and aggregate into abnormal protein deposits in MFM. Studies in transgenic mice and transfected cell lines have demostrated that mutation of target proteins facilitates protein aggregation 3, 4, 5, 24, 25, 42, 43, 68, 73, 75, 76. Yet, additional complementary proteins may be involved in this process.

UCHL1 and other neural proteins in aggregates: role of neuron‐restrictive silencer factor

Ubiquitin carboxy‐terminal hydrolases (UCHLs) are enzymes involved in the hydrolysis of polyubiquitin chains to increase the availability of free monomeric ubiquitin molecules facilitating protein degradation (41). UCHL1 is highly expressed in brain and testis, but not in muscle. UCHL1 is present in inclusions associated with several neurodegenerative diseases, and it is considered to play a role in inclusion formation in Parkinson's disease 1, 41, 66. It has been recently demonstrated that mRNA and protein levels of UCHL1 are increased in myotilinopathies (6). The reasons for this phenomenon are unknown, but recent studies have shown that abnormal expression of certain transcription factors may be causative. NRSF/REST is a neuronal gene repressor in non‐neuronal cells 11, 58. Several studies have shown that synaptophysin and SNAP25 are NRSF/REST target genes (7). UCHL1 and α‐internexin are also regulated by REST (6). Interestingly, mRNA and protein NRSF/REST levels are reduced in myotilinopathy muscles when compared with control muscles. This is accompanied by increased aberrant expression levels not only of UCHL1, but also of other neuronal proteins such as SNAP25, synaptophysin and α‐internexin in skeletal muscles in myotilinopathies (6) (Figure 2E,F).

Mutant ubiquitin: a marker of proteasomal dysfunction

Mutant ubiquitin (UBB+1) is an aberrant, potentially toxic form of ubiquitin generated by a non‐DNA‐encoded dinucleotide deletion occurring within UBB mRNA (72). The resulting protein has a modified C‐terminus, and is unable to ubiquitinate other protein substrates. UBB+1 is ubiquitinated itself, and while at low expression levels it can be degraded by the proteasome, at high levels, it can inhibit the proteasome pathway 15, 38. Yet, the accumulation of UBB+1 is considered a specific marker of proteasomal dysfunction in certain neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Down syndrome and other tauopathies 20, 72. Furthermore, UBB+1 is expressed in muscle fibers in inclusion body myositis (21).

Aberrant expression of mutant ubiquitin UBB+1 has been observed in myotilinopathies and desminopathies (46). UBB+1 colocalizes with myotilin and desmin in both disorders as revealed in double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy studies. These observations suggest that the presence of UBB+1 in muscle fibers in myotilinopathies and desminopathies is an additional factor contributing to dysfunction of the UPS in MFM.

p62

Sequestosome 1/p62 is a 62 kDa protein encoded by an immediate early response gene activated by a variety of extracellular signals (26). p62 participates actively in the formation of protein aggregates by recruiting poly‐ubiquitinated proteins through its UBA domain 60, 61. It has been proposed that p62 may promote aggregation and sequestration of abnormal proteins as inert but reversible inclusion bodies (48). Moreover, p62 binds specifically to protein aggregates, or to misfolded and ubiquitinated proteins in several human diseases, including neuronal and glial ubiquitinated inclusions in Alzheimer's disease, Pick's disease, Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy (78). It has recently been shown that p62 is also involved in the delivery of polyubiquitylated proteins for autophagy degradation (49).

p62 has been found colocalizing with myotilin in muscle fibers in myotilinopathies, and to a much lesser extent in desminopathies, as revealed in sections double stained for p62 and myotilin (46). The differing amounts of p62 in myotilinopathies and desminopathies may be related to the different degrees of compaction of myofibrillary inclusions in the two disorders, as well as to the less common formation of inclusion bodies in desminopathies.

Clusterin and the aggresome in MFM

Aggresomes are microtubule‐based inclusion bodies composed of aggregates of misfolded proteins near the centrosome. They are formed in response to cellular overload of abnormally folded proteins after the unfolded protein response and the UPS become overwhelmed and before autophagy is engaged. Aggregated proteins translocate to the aggresome by active transport (36). γ‐tubulin is thought to mediate the link between microtubules and the centrosome, and to function as a regulator of the microtubule‐organizing center.

Protein inclusions in MFM share features with aggresome structures as indicated by double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. γ‐tubulin, which is considered a marker for aggresomes, colocalizes with clusterin, αB‐crystallin and myotilin in individual muscle fibers in MFMs (19) (Figure 4). Moreover, γ‐tubulin protein expression levels, as revealed by Western blotting, are increased in MFMs (19). Furthermore, the Arg120Gly mutation in the αB‐crystallin gene, which causes cardiomyopathy, forms aggresomes in vitro (9) and it is accompanied by aggresome‐related dense bodies containing desmin and αB‐crystallin in transgenic mice (56).

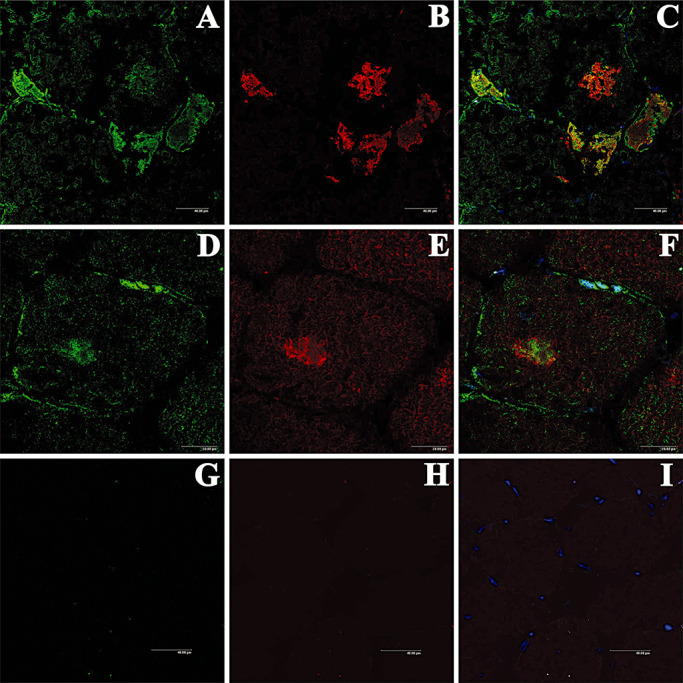

Figure 4.

Double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy to γ‐tubulin (green, A, D) and myotilin (red, B, E) in myotilinopathy. γ‐tubulin partially colocalizes with myotilin (merge, C, F). One section of the same case stained only with the secondary antibodies is used as a negative control (G, H). Nuclei are visualized with TO‐PRO‐3‐iodide (blue).

Another component of myofibrillary inclusions in MFMs is clusterin (apolipoprotein J, SP40), a sialoglycoprotein with a nearly ubiquitous tissue distribution (35). Clusterin shares functional homology with the small heat shock proteins. Clusterin participates in multiple physiological processes and has been associated in several pathological conditions, including conformational protein disorders affecting the central nervous system such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and prion diseases 10, 22, 54, 57. It has been proposed that clusterin gene expression is increased in response to altered protein homeostasis and oxidative stress injury (71).

Clusterin immunoreactivity is present in association with abnormal protein deposits in MFMs, as revealed by single‐ and double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy to clusterin and myotilin, αB‐crystallin and ubiquitin, thus indicating clusterin association with abnormal protein aggregates. Furthermore, Western blots have shown several clusterin‐immunoreactive bands between 34 and 80 kDa, probably corresponding to heterodimers and aggregates with other proteins in control and MFM cases (19).

Oxidative and nitrosative stress in MFMs

It is well known that oxidative and nitrosative damage promotes protein misfolding and aggregation. Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species and the level of antioxidant responses. Skeletal muscles are particularly prone to accumulating oxidative damage to DNA, lipids and proteins over time 2, 50, 69. Oxidized proteins are degraded by the UPS 12, 13, 51. However, proteasome activity drastically declines in cells containing large amounts of aggregated or oxidized proteins, and thereby facilitates the accumulation of abnormal proteins through covalent cross‐linking reactions and increased surface hydrophobicity 12, 13.

Recent studies have demonstrated increased levels of the glycoxidation markers AGE, CML and CEL, as well as of the lipoxidation markers MDAL and HNE, in muscle samples in myotilinopathies and desminopathies as revealed by Western blotting, immunohistochemistry and double‐labeling immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy (34). Furthermore, increased levels of nitrotyrosine occur in myotilinopathies and desminopathies when compared with controls (34). By means of immunohistochemistry, glycoxidation markers, particularly AGE and AGE receptor (RAGE), are seen to be aberrantly expressed in muscle fibers containing protein aggregates in myotilinopathies, and to a lesser extent in desminopathies. Interestingly, AGE colocalizes with myotilin, as well as with ubiquitin and p62, in abnormal fibers, thus providing a link between oxidative damage and abnormal protein aggregation in MFMs (Figure 5). In addition, neuronal, inducible and endothelial nitric oxide synthases (nNOS, iNOS and eNOS), as well as SOD2 are over‐expressed in abnormal muscle fibers in myotilinopathies and desminopathies. Detection of oxidized and nitrated proteins has been performed by means of bidimensional gel electrophoresis, in‐gel digestion and mass spectrometry in MFMs (33). As a result, desmin has been identified as a major target of oxidation and nitration in desminopathies and myotilinopathies. Additionaly, oxidized and nitrated mutant desmin has been identified in samples from desminopathies, whereas oxidized pyruvate kinase muscle splice from M1 has been found in myotilinopathies (33). Together, these observations strongly suggest that oxidative and nitrosative damage plays an important role in the pathogenesis of MFMs.

Figure 5.

Myofibrillary inclusions in myotilinopathy (Ser60Cys) showing p62 (A) colocalizing with MDAL (B), RAGE (C), nNOS (D), eNOS (E) and iNOS (F). A–F ×200.

The causes of oxidative stress leading to oxidative damage in MFMs are not fully known, but several concomitant factors may contribute to the progression of oxidative and nitrosative injuries in MFMs. Increased numbers of mitochondria in the vicinity of abnormal protein aggregates and isolated changes in individual mitochondria morphology are commonly seen in muscle biopsies from patients suffering from MFM. Low mitochondria respiratory chain complex I activity has also been reported in desminopathy 53, 59. Redox proteomic studies have shown that, in addition to desmin, the oxidation of mitochondrial enzyme pyruvate kinase is a putative component of impaired mitochondrial function, at least in some cases of myotilinopathy (33).

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Proteinaceous inclusions in muscle cells constitute the morphological hallmark of MFMs. Identification of a number of proteins within the protein aggregates has led to the identification of causative genes, and has helped to better understand the mechanisms governing aggregation of these proteins. Mutant proteins, aggresome formation, p62, UBB1+, oxidative and nitrosative damage, among other factors, may block the UPS resulting in aggregate formation. Whether other proteolytic pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of MFM deserves future investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors' work is funded by a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III PI05/1213. I wish to thank Dr. I. Ferrer for suggestions and comments, and T. Yohannan for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ardley HC, Scott GB, Rose SA, Tan NG, Robinson PA (2004) UCH‐l1 aggresome formation in response to proteasome impairment indicates a role in inclusion formation in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 90:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arthur PG, Grounds MD, Shavlakadze T (2008) Oxidative stress as a therapeutic target during muscle wasting: considering the complex interactions. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 11:408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bär H, Strelkov SV, Sjöberg G, Aebi U, Herrmann H (2004) The biology of desmin filaments: how do mutations affect their structure, assembly and organisation. J Struct Biol 148:137–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bär H, Fischer D, Goudeau B, Kley RA, Clemen CS, Vicart P et al (2005) Pathogenic effects of a novel heterozygous R350P desmin mutation on the assembly of desmin intermediate filaments in vivo and in vitro . Hum Mol Genet 14:1251–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bär H, Mücke N, Ringler P, Müller SA, Kreplak L, Katus HA et al (2006) Impact of disease mutations on the desmin filament assembly process. J Mol Biol 360:1031–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barrachina M, Moreno J, Juvés S, Moreno D, Olivé M, Ferrer I (2007) Target genes of neuron‐restrictive silencer factor are abnormally up‐regulated in human myotilinopathy. Am J Pathol 171:1312–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruce AW, Donaldson IJ, Wood IC, Yerbury SA, Sadowski MI, Chapman M et al (2004) Genome‐wide analysis of repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor/neuron‐restrictive silencing factor (REST/NRSF) target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:10458–10463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carrell RW, Lomas DA (1997) Conformational disease. Lancet 350:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chávez Zobel AT, Loranger A, Marceau N, Thériault JR, Lambert H, Landry J (2003) Distinct chaperone mechanisms can delay the formation of aggresomes by the myopathy‐causing R120G alpha‐B‐crystallin mutant. Hum Mol Genet 12:1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choi‐Miura NH, Oda T (1996) Relationship between multifunctional protein “clusterin” and Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 17:717–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chong JA, Tapia‐Ramírez J, Kim S, Toledo‐Aral JJ, Zheng Y, Boutros MC et al (1995) REST: a mammalian silencer protein that restricts sodium channel gene expression to neurons. Cell 80:949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davies KJA (2001) Degradation of oxidized proteins by the 20S proteasome. Biochimie 83:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davies KJA, Shringarepure R (2006) Preferential degradation of oxidized proteins by the 20S proteasome may be inhibited in aging and inflammatory neuromuscular diseases. Neurology 66(Suppl. 1):s93–s96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Bleecker JL, Engel AG, Ertl B (1996) Myofibrillar myopathy with foci of desmin positivity. II. Immunocytochemical analysis reveals accumulation of multiple other proteins. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 55:563–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Pril R, Fischer DF, Van Leeuwen FW (2006) Conformational diseases: an umbrella for various neurological disorders with an impaired ubiquitin–proteasome system. Neurobiol Aging 27:515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellis RJ, Pinheiro TJT (2002) Danger‐misfolded proteins. Nature 416:483–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferrer I, Olivé M (2008) Molecular pathology of myofibrillar myopathies. Expert Rev Mol Med 10:e25. doi:10.1017/S1462399408000793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrer I, Matín B, Castaño JG, Lucas JJ, Moreno D, Olivé M (2004) Proteasomal expression, induction of immunoproteasome subunits, and local MHC class I presentation in myofibrillar myopathy and inclusion body myositis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63:484–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrer I, Carmona M, Blanco R, Moreno D, Torrejón‐Escribano B, Olivé M (2005) Involvement of clusterin and the aggresome in abnormal protein deposits in myofibrillar myopathies and inclusion body myositis. Brain Pathol 15:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fischer DF, De Vos RA, Van Dijk R, De Vrij FM, Proper EA, Sonnemans MA et al (2003) Disease‐specific accumulation of mutant ubiquitin as a marker for proteasomal dysfunction in the brain. FASEB J 17:2014–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fratta P, Engel WK, Van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM, Vattemi G, Askanas V (2004) Mutant ubiquitin UBB+1 is accumulated in sporadic inclusion‐body myositis muscle fibers. Neurology 63:1114–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Freixes M, Puig B, Rodríguez A, Torrejón‐Escribano B, Blanco R, Ferrer I (2004) Clusterin solubility and aggregation in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Acta Neuropathol 108:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gao X, Hu H (2008) Quality control of the proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 40:612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garvey SM, Miller SE, Claflin DR, Faulkner JA, Hauser MA (2006) Transgenic mice expressing the myotilin T57I mutation unite the pathology associated with LGMD1A and MFM. Hum Mol Genet 15:2348–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garvey SM, Liu Y, Miller SE, Hauser MA (2008) Myotilin overexpression enhances myopathology in the LGMD1A mouse model. Muscle Nerve 37:663–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Geetha T, Wooten MW (2005) Structure and functional properties of the ubiquitin binding protein p62. FEBS Lett 512:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glickman MH, Ciechanover A (2002) The ubiquitin–proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev 82:373–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goebel HH, Muller HD (2006) Protein aggregate myopathies. Semin Pediatr Neurol 13:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goebel HH, Fardeau M, Olivé M, Schröder R (2008) 156th ENMC International Workshop: desmin and protein aggregate myopathies, 9–11 November 2007, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord 18:583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldfarb LG, Park KY, Cervenáková L, Gorokhova S, Lee HS, Vasconcelos O et al (1998) Missense mutations in desmin associated with familial cardiac and skeletal myopathy. Nat Genet 19: 402–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldfarb LG, Vicart P, Goebel HH, Dalakas MC (2004) Desmin myopathy. Brain 127:723–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grune T, Jung T, Merker K, Davies KJ (2004) Decreased proteolysis caused by protein aggregates, inclusion body, plaques, lipofuscin, ceroid, and aggresomes during oxidative stress, aging, and disease. J Biol Chem 36:2519–2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Janué A, Odena MA, Oliveira E, Olivé M, Ferrer I (2007) Desmin is oxidized and nitrated in affected muscles in myotilinopathies and desminopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 66:711–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Janué A, Olive M, Ferrer I (2007) Oxidative stress in desminopathies and myotilinopathies: a link between oxidative damage and abnormal protein aggregation. Brain Pathol 17:377–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones SE, Jomary C (2002) Clusterin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 34:427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kopito RR (2000) Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol 10:524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kostova Z, Wolf DH (2003) For whom the bell tolls: protein quality control of the endoplasmic reticulum and the ubiquitin–proteasome connection. EMBO J 22:2309–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindsten K, De Vrij FM, Verhoef LG, Fischer DF, Van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM et al (2002) Mutant ubiquitin found in neurodegenerative disorders is a ubiquitin fusion degradation substrate that blocks proteasomal degradation. J Cell Biol 157:417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu J, Chen Q, Huang W, Horak KM, Zheng H, Mestril R, Wang X (2006) Impairment of the ubiquitin–proteasome system in desminopathy mouse hearts. FASEB J 20:362–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu J, Tang M, Mestril R, Wang X (2006) Aberrant protein aggregation is essential for a mutant desmin to impair the proteolytic function of the ubiquitin–proteasome system in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40:451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu Y, Fallon L, Lashuel HA, Liu Z, Lansbury PT Jr (2002) The UCH‐L1 gene encodes two opposing enzymatic activities that affect alpha‐synuclein degradation and Parkinson's disease susceptibility. Cell 111:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Löwe T, Kley RA, Van Der Ven PF, Himmel M, Huebner A, Vorgerd M, Fürst DO (2007) The pathomechanism of filaminopathy: altered biochemical properties explain the cellular phenotype of a protein aggregation myopathy. Hum Mol Genet 16:1351–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muñoz‐Mármol AM, Strasser G, Isamat M, Coulombe PA, Yang Y, Roca X et al (1998) A dysfunctional desmin mutation in a patient with severe generalised myopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:11312–11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nakano S, Engel AG, Waclawik AJ, Emslie‐Smith AM, Busis NA (1996) Myofibrillar myopathy with abnormal foci of desmin positivity. I. Light and electron miscroscopy analysis of 10 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 55:549–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Olivé M, Goldfarb LG, Shatunov A, Fischer D, Ferrer I (2005) Myotilinopathy: refining the clinical and myopathological phenotype. Brain 128:2315–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Olivé M, Van Leeuwen FW, Janué A, Moreno D, Torrejón‐Escribano B, Ferrer I (2008) Expression of mutant ubiquitin (UBB+1) and p62 in myotilinopathies and desminopathies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 34:76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Olivé M, Janué A, Moreno D, Gámez J, Torrejón‐Escribano B, Ferrer I (2009) TAR DNA‐binding protein 43 accumulation in protein aggregate myopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68:262–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Paine MG, Babu JR, Seibenhener ML, Wooten MW (2005) Evidence for p62 aggregate formation: role in cell survival. FEBS Lett 579:5029–5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H et al (2007) p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem 282:24131–24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Piec I, Listrat A, Alliot J, Chambon C, Taylor RG, Bechet D (2005) Differential proteome analysis of aging in rat skeletal muscle. FASEB J 19:1143–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Poppek D, Grune T (2006) Proteasomal defense of oxidative protein modifications. Antioxid Redox Signal 8:173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Raju R, Dalakas MC (2007) Absence of upregulated genes associated with protein accumulations in desmin myopathy. Muscle Nerve 35:386–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reimann J, Kunz WS, Vielhaber S, Kappes‐Horn K, Schröder R (2003) Mitochondrial dysfunction in myofibrillar myopathy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 29:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rosenberg ME, Silkensen J (1995) Clusterin: physiological and pathological considerations. Int Biochem Cell Biol 27:633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rubinsztein DC (2006) The roles of intracellular protein‐degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature 443:780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sanbe A, Osinska H, Saffitz JE, Glabe CG, Kayed R, Maloyan A, Robbins J (2004) Desmin‐related cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice: a cardiac amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:10132–10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sasaki K, Doh‐ura K, Wakisaka Y, Iwaki T (2002) Clusterin/Apolipoprotein J is associated with cortical Lewy bodies: immunohistochemical study in cases with alpha‐synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol 104:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schoenherr CJ, Anderson DJ (1995) The neuron‐restrictive silencer factor (NRSF): a coordinate repressor of multiple neuron‐specific genes. Science 267:1360–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schröder R, Goudeau B, Simon MC, Fischer D, Eggermann T, Clemen CS et al (2003) On noxious desmin: functional effects of a novel heterozygous desmin insertion mutation on the extrasarcomeric desmin cytoskeleton and mitochondria. Hum Mol Genet 12:657–669. Erratum in: Hum Mol Genet (2007) 16:2989–2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Seibenhener ML, Babu JR, Geetha T, Wong HC, Krishna NR, Wooten MW (2004) Sequestosome 1/p62 is a polyubiquitin chain binding protein involved in ubiquitin proteasome degradation. Mol Cell Biol 24:8055–8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seibenhener ML, Geetha T, Wooten MW (2007) Sequestrosome 1/p62—more than just a scaffold. FEBS Lett 581:175–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Selcen D, Engel AG (2004) Mutations in myotilin cause myofibrillar myopathy. Neurology 62:1363–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Selcen D, Engel AG (2005) Mutations in ZASP define a novel form of muscular dystrophy in humans. Ann Neurol 57:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Selcen D, Ohno K, Engel AG (2004) Myofibrillar myopathy: clinical, morphological and genetic studies in 63 patients. Brain 127:439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Selcen D, Muntoni F, Burton BK, Pegoraro E, Sewry C, Bite AV, Engel AG (2008) Mutation in BAG3 causes severe dominant childhood muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 65:83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Setsuie R, Wada K (2007) The functions of UCH‐L1 and its relation to neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Int 5:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sherman MY, Al G (2001) Cellular defenses against unfolded proteins: a cell biologist thinks about neurodegenerative disease. Neuron 29:15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sjöberg G, Saavedra‐Matiz CA, Rosen DR, Wijsman EM, Borg K, Horowitz SH, Sejersen T (1999) Missense mutation in the desmin rod domain is associated with autosomal dominant distal myopathy and exerts a dominant negative effect on filament formation. Hum Mol Genet 8:2191–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stagsted J, Bendixen E, Andersen HJ (2004) Identification of specific oxidatively modified proteins in chicken muscles using a combined immunologic and proteomic approach. J Agric Food Chem 52:3967–3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tai HC, Schuman EM (2008) Ubiquitin, the proteasome and protein degradation in neuronal function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 826–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Trougakos IP, Gonos ES (2006) Regulation of clusterin/ apolipoprotein J, a functional homologue to the small heat shock proteins, by oxidative stress in ageing and age‐related diseases. Free Radic Res 40:1324–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Van Leeuwen FW, De Kleijn DP, Van Den Hurk HH, Neubauer A, Sonnemans MA, Sluijs JA et al (1998) Frameshift mutants of beta amyloid precursor protein and ubiquitin‐B in Alzheimer's and Down patients. Science 279:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vicart P, Caron A, Guicheney P, Li Z, Prévost MC, Faure A et al (1998) A missense mutation in the αB‐crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin‐related myopathy. Nat Genet 20:92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vorgerd M, Van Der Ven PF, Bruchertseifer V, Löwe T, Kley RA, Schröder R et al (2005) A mutation in the dimerization domain of filamin causes a novel type of autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy. Am J Hum Genet 77:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang X, Osinska H, Dorn GW, Nieman M, Lorenz JN, Gerdes AM et al (2001) Mouse model of desmin‐related cardiomyopathy. Circulation 103:2402–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wang X, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Gerdes AM, Nieman M, Lorenz J et al (2001) Expression of R120G‐αB‐crystallin causes aberrant desmin and αB‐crystallin aggregation and cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res 89:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Winslow AR, Rubinsztein DC (2008) Autophagy in neurodegeneration and development. Biochim Biophys Acta 1782:723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zatloukal K, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, Heid H, Schnoelzer M, Kenner L et al (2002) p62 Is a common component of cytoplasmic inclusions in protein aggregation diseases. Am J Pathol 160: 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]