Abstract

Background

Transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN) is caused by delayed clearance of lung fluid at birth. TTN typically appears within the first two hours of life in term and late preterm neonates and is characterized by tachypnea and signs of respiratory distress. Although it is usually a self‐limited condition, admission to a neonatal unit is frequently required for monitoring and providing respiratory support. Restricting intake of fluids administered to these infants in the first days of life might improve clearance of lung liquid, thus reducing the effort required to breathe, improving respiratory distress, and potentially reducing the duration of tachypnea.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of restricted fluid therapy as compared to standard fluid therapy in decreasing the duration of oxygen administration and the need for noninvasive or invasive ventilation among neonates with TTN.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 12), in the Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE and electronic ahead of print publications, in‐process & other non‐indexed citations, Daily and Versions(R); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), on December 6, 2019. We also searched clinical trial databases and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomized controlled trials and quasi‐randomized trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, and cluster trials on fluid restriction in term and preterm neonates with the diagnosis of TTN or delayed adaptation during the first week after birth.

Data collection and analysis

For each of the included trials, two review authors independently extracted data (e.g. number of participants, birth weight, gestational age, duration of oxygen therapy, need for continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP], need for mechanical ventilation, duration of mechanical ventilation) and assessed the risk of bias (e.g. adequacy of randomization, blinding, completeness of follow‐up). The primary outcome considered in this review was the duration of supplemental oxygen therapy in hours or days. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence.

Main results

Four trials enrolling 317 infants met the inclusion criteria. Three trials enrolled late preterm and term infants with TTN, and the fourth trial enrolled only term infants with TTN. Infants were on various methods of respiratory support at the time of enrollment including room air, oxygen, or nasal CPAP. Infants in the fluid‐restricted group received 15 to 20 mL/kg/d less fluid than those in the control group for varying durations after enrollment. Two studies had high risk of selection bias, and three out of four had high risk of performance bias. Only one study had low risk of detection bias, with two at high risk and one at unclear risk.

The certainty of evidence for all outcomes was very low due to imprecision of estimates and unclear risk of bias. Two trials reported the primary duration of supplemental oxygen therapy. We are uncertain whether fluid restriction decreases or increases the duration of supplemental oxygen therapy (mean difference [MD] ‐12.95 hours, 95% confidence interval [CI] ‐32.82 to 6.92; I² = 98%; 172 infants). Similarly, there is uncertainty for various secondary outcomes including incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L, risk ratio [RR] 4.0, 95% CI 0.46 to 34.54; test of heterogeneity not applicable; 1 trial, 100 infants), hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 40 mg/dL, RR 1.0, 95% CI 0.15 to 6.82; test of heterogeneity not applicable; 2 trials, 164 infants), endotracheal ventilation (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.24 to 2.23; I² = 0%; 3 trials, 242 infants), need for noninvasive ventilation (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.17; test of heterogeneity not applicable; 2 trials, 150 infants), length of hospital stay (MD ‐0.92 days, 95% CI ‐1.53 to ‐0.31; test of heterogeneity not applicable; 1 trial, 80 infants), and cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age (%) (MD 0.24, 95% CI ‐1.60 to 2.08; I² = 89%; 2 trials, 156 infants). We did not identify any ongoing trials; however, one trial is awaiting classification.

Authors' conclusions

We found limited evidence to establish the benefits and harms of fluid restriction in the management of TTN. Given the very low certainty of available evidence, it is impossible to determine whether fluid restriction is safe or effective for management of TTN. However, given the simplicity of the intervention, a well‐designed trial is justified.

Plain language summary

Giving less oral or intravenous fluid to newborn infants with breathing difficulty (transient tachypnea of the newborn)

Review question

Does fluid restriction (i.e. giving a lesser quantity of fluids by mouth to the stomach or through the veins) in babies with rapid breathing at birth due to delayed clearance of normal fetal lung fluid (a condition called "transient tachypnea of the newborn") reduce the duration of treatment with oxygen?

Background

Transient tachypnea (abnormally rapid breathing) of the newborn (TTN) is characterized by a high respiratory rate (more than 60 breaths per minute) and signs of respiratory distress (difficulty breathing). It typically appears within the first two hours of life in babies born at, or after, 34 weeks' gestational age. Although transient tachypnea of the newborn usually improves without treatment, it might be associated with wheezing in late childhood. The idea behind using fluid restriction for transient tachypnea of the newborn consists of reducing fluid in small cavities within the lungs called the alveoli and improving breathing difficulties. In the first days after birth, these babies may receive fluids directly into the mouth (colostrum or milk), to the stomach (milk or solutions containing dextrose solution), or through the veins (solutions containing dextrose solution). This review reports and critically analyzes available evidence on the benefits and harms of fluid restriction in the management of transient tachypnea of the newborn.

Study characteristics

We identified and included four studies (317 babies in total) comparing the use of restricted versus standard fluid administration. We found no ongoing studies; however, one trial is awaiting classification. Evidence is current to December 6, 2019.

Key results

The very limited available evidence cannot answer our review question. Only two small studies (172 babies) reported the duration of treatment with oxygen ‐ the primary outcome of this review ‐ and we are uncertain whether fluid restriction decreases or increases treatment duration. Three studies reported the incidence of the need for a breathing machine, and we are uncertain about any differences between restricted and standard fluid administration. The length of hospital stay was shorter by 22 hours for infants with fluid restriction; however, this was reported in only one trial (80 babies) of low methodological quality, and we are uncertain about this finding.

Certainty of evidence

The certainty of evidence was very low for all analyses because only a small number of studies have looked at this intervention, few babies were included in these studies, and all studies could have been better designed. Thus, we are uncertain whether fluid restriction improves the outcomes of babies with TTN.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Restricted compared to standard fluid management in the management of transient tachypnea of the newborn.

| Restricted compared to standard fluid management in the management of transient tachypnea of the newborn | |||||

| Patient or population: late preterm and full‐term infants with transient tachypnea of the newborn Setting: neonatal units in Iran (2 studies), India (1 study), and USA (1 study) Intervention: restricted fluid administration in the very first days of life Comparison: standard fluid administration in the very first days of life | |||||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) follow‐up | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk difference with standard fluid management | Risk difference with restricted fluid management | ||||

| Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy (hours) | 172 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa | ‐ | Mean duration of supplemental oxygen therapy ranged from 6 to 53 hours | MD 12.95 lower (32.82 lower to 6.92 higher) |

| Incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L) at end of intervention period (proportions) | 100 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWb | RR 4.00 (0.46 to 34.54) | Study population | |

| 20 per 1000 | 60 more per 1000 (11 fewer to 671 more) | ||||

| Incidence of hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 40 mg/dL) at end of intervention period (proportions) | 164 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWc | RR 1.00 (0.15 to 6.82) | Study population | |

| 24 per 1000 | 0 fewer per 1000 (21 fewer to 142 more) | ||||

| Incidence of endotracheal ventilation (proportions) during hospital stay (for infants on no support or noninvasive support at the time of study entry) | 242 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd | RR 0.73 (0.24 to 2.23) | Study population | |

| 57 per 1000 | 15 fewer per 1000 (44 fewer to 71 more) | ||||

| Incidence of noninvasive (nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation) respiratory support during hospital stay | 150 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWe | RR 0.40 (0.14 to 1.17) | Study population | |

| 250 per 1000 | 150 fewer per 1000 (215 fewer to 42 more) | ||||

| Length of hospital stay (in days) | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWf | ‐ | Mean length of hospital stay was 5 days | MD 0.92 lower (1.53 lower to 0.31 lower) |

| Cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age (%) | 156 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWg | ‐ | Mean total cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age ranged from 4% to 5% | MD 0.24 higher (1.60 lower to 2.08 higher) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to high risk of bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (two small trials). Moreover, serious inconsistency due to high heterogeneity (I²> 75%).

bDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to high risk of bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (one small trial).

cDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to high risk of bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (two small trials).

dDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to high risk of bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (three small trials).

eDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to high risk of bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (two small trials).

fDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to unclear selection and detection bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (one small trial).

gDowngraded one level for serious study limitations (due to high risk of bias), and downgraded two levels for very serious imprecision (two small trials). Moreover, serious inconsistency due to high heterogeneity (I²> 75%).

Background

Description of the condition

Transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN), also known as wet lung, or respiratory distress syndrome type 2, is one of the most common causes of respiratory distress in the newborn period (Hibbard 2010; Jefferies 2013; Kumar 1996). TTN is estimated to affect 0.5% to 2.8% of all live births (Clark 2005; Rubaltelli 1998; Tutdibi 2010), primarily in late preterm and term newborn infants who present with features of respiratory distress in the form of tachypnea, grunting, and chest retractions. TTN symptoms typically start in the first few hours after birth and usually are self‐limiting.

TTN is the result of delayed clearance of fetal lung fluid (Gowen 1988). Fetal lung fluid is secreted in utero by alveolar cells and contributes to normal lung development. This fluid must be absorbed at the time of birth for the normal transition to air breathing. Increased levels of mediators during labor, such as epinephrine and glucocorticoids, activate sodium channels that absorb sodium and water from the alveolar space into the interstitium (Barker 2002; Greenough 1992; Irestedt 1982; Jain 2006). Persistence of fluid in alveoli after birth interferes with normal gas exchange, resulting in respiratory distress. In addition, retained fluid accumulates in the peribronchiolar lymphatics, causing compression of bronchioles and resulting in air trapping and hyperinflation. Risk factors associated with the development of TTN include prematurity, delivery by cesarean section (particularly without preceding labor), and male sex (Rawlings 1984; Riskin 2005).

The diagnosis of TTN is usually a diagnosis of exclusion, as no specific diagnostic test is available. Treatment is mainly supportive and consists primarily of providing oxygen therapy, withholding enteral feeds, and initiating intravenous fluids. Rarely, assisted ventilation is required. Although newborn infants with TTN recover fully in two to three days, they may need to be admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit while more serious causes of respiratory distress are ruled out. This frequently delays the start of enteral feeds and prolongs hospital stay (Riskin 2005). Therefore, therapy that is effective early in the course of the disease could reduce both treatment burden and resource utilization.

Various therapies targeting acceleration of lung fluid clearance to ameliorate the severity and shorten the course of TTN have been tried unsuccessfully (Kao 2008; Karabayir 2006; Wiswell 1985). Furosemide is a potent diuretic known to stimulate lung fluid resorption that has been investigated for the management of TTN in two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Bland 1978; Demling 1978; Kao 1983; Karabayir 2006; Wiswell 1985). A Cochrane systematic review including these two studies could not find any significant difference in the severity of symptoms or the duration of hospital stay (Kasab 2015). An RCT examining the role of inhaled epinephrine in TTN did not detect any difference in the rate of resolution of tachypnea (Kao 2008).

Description of the intervention

The transition from fetal to newborn life is associated with major changes in fluid balance and body weight during the first week of life. An abrupt decrease in total body water occurs as a result of physiological diuresis (Shaffer 1987a). This physiological diuresis results in weight loss of 5% to 10% in healthy term neonates. Thereafter, healthy term neonates establish a pattern of steady weight gain. However, preterm neonates lose an average of 15% of their birth weight due to increases in total body water and extracellular volume (Shaffer 1987b). Depending on the degree of prematurity and associated morbidities, neonates start to regain their birth weight by 10 to 20 days of life. This physiological weight loss after birth is essential and may be beneficial, as lack of appropriate weight loss and higher fluid intake in the first few days of life are associated with higher risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia and symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus in preterm neonates (Bell 2014; Oh 2005).

The daily fluid requirement in neonates is calculated by taking into account the estimates for obligatory water loss through kidneys and insensible water loss through skin and airways. Several factors including the infant's gestational age, postnatal age, postnatal weight change, and urine output, along with environmental factors (e.g. ventilation, phototherapy, environmental temperature, ambient humidity), are taken into consideration when the daily fluid requirement is calculated. Depending upon the degree of immaturity, the fluid requirement on the first day of life is approximately 60 to 80 mL/kg/d in term neonates and 80 to 160 mL/kg/d in preterm neonates. Subsequent increments vary from 10 to 40 mL/kg/d depending on clinical and laboratory parameters to reach a maximum fluid intake of 150 mL/kg/d in term neonates and 150 to 200 mL/kg/d in preterm neonates by the seventh to tenth day of life (Lorenz 1995; Lorenz 2002).

Healthy neonates on exclusive breastfeeding receive lower fluid volume compared to neonates with respiratory distress or other morbidities who are prescribed intravenous fluids. This occurs because only a small amount of breast milk is secreted during the first 24 to 48 hours after birth. It is reasonable to hypothesize that restricting fluids for the first three to five days in neonates with TTN will mimic the physiological intake of their normal unaffected counterparts and may hasten the resolution of symptoms.

A Cochrane systematic review compared restricted versus liberal water intake in preterm neonates who were predominantly receiving parenteral fluids for the first three days of life. Restricted water intake in studies was achieved by decreasing daily fluid intake in the restricted group by 20 to 40 mL/kg/d or by targeting a greater daily (3% to 5% versus 1% to 3%) or cumulative (15% versus 10%) postnatal weight loss. Restricted fluid therapy significantly reduced the risks of patent ductus arteriosus and necrotizing enterocolitis. However, it significantly increased postnatal weight loss (Bell 2014).

How the intervention might work

Increased water content in the lung interstitium can result from elevated pulmonary venous pressure (e.g. right‐sided heart failure) or increased pulmonary blood flow (e.g. patent ductus arteriosus). Restriction of fluid intake is commonly practiced in these conditions. Similarly, in TTN, water content in the lung interstitium is increased as alveolar fluid is absorbed through the lymphatic system. Therefore, restriction of fluid intake for the first 48 to 72 hours of life may hasten drainage of fluid absorbed into the vascular system, resulting in faster resolution of symptoms and decreasing the duration of oxygen therapy and the length of hospitalization.

Why it is important to do this review

Although TTN is a mild disease with a self‐limiting course, it results in a large number of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions (Jefferies 2013). Neonates are separated from their parents, which delays parent‐child bonding and initiation of breastfeeding, resulting in not only a social but also a financial burden, depending on the duration of hospitalization. These medical, psychosocial, and financial consequences have assumed greater importance with increasing rates of late preterm birth and birth by elective cesarean section (Martin 2010; Ramachandrappa 2008).

The only available treatment for TTN is supportive care, which primarily involves oxygen therapy. Any intervention that hastens the clearance of retained fetal lung fluid will reduce the severity and duration of symptoms, which in turn will decrease the need for and duration of oxygen therapy and the length of hospitalization.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of restricted fluid therapy as compared to standard fluid therapy in decreasing the duration of oxygen administration and the need for noninvasive or invasive ventilation among neonates with TTN.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs and cluster‐randomized trials in this review. We considered trials reported in abstract form as eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

We included term and preterm (less than 37 completed weeks) neonates with a diagnosis of TTN or delayed adaptation during the first week of life. We included all neonates with TTN irrespective of the method of respiratory support provided (supplemental oxygen, noninvasive ventilation, or invasive ventilation) at the time of randomization.

We defined TTN or delayed adaptation as the presence of respiratory distress starting within six hours after birth, with X‐ray findings suggestive of fluid retention (linear streaking at hila and/or interlobar fluid and/or hyperinflation) or a normal chest X‐ray with no other apparent reason for respiratory distress.

We defined respiratory distress as the presence of at least two of the following criteria.

Respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths per minute.

Subcostal/intercostal retractions.

Expiratory grunt/groaning.

Types of interventions

We included studies comparing restricted and standard fluid therapies provided by intravenous or oral route, or both. We defined restricted fluid therapy as total fluid intake by all routes that is 90% or less of the standard amount of fluid intake per day. This restriction should be continued for at least 24 hours during the first week of life.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes considered were both continuous and categorical outcomes and include the following.

Primary outcomes

Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy in hours or days

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L) during and at the end of the intervention period (proportions)

Incidence of azotemia (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL) during and at the end of the intervention period (proportions)

Incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment by phototherapy during and at the end of the intervention period (proportions)

Incidence of hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 40 mg/dL) during and at the end of the intervention period (proportions)

Incidence of endotracheal ventilation (proportions) (for infants receiving no support or noninvasive support at the time of study entry)

Incidence of noninvasive (nasal continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] or nasal ventilation) respiratory support (proportions) (for infants receiving no support at the time of study entry)

Length of hospital stay (in days)

Age (in hours/days) of starting first enteral feed

Age (in hours/days) of attainment of full enteral feeds (i.e. complete stoppage of intravenous fluids)

Cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age (%)

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal.

Electronic searches

We conducted a comprehensive search including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 12), in the Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) (1946 to December 6, 2019); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1981 to December 6, 2019). We have included the search strategies for each database in Appendix 1. We did not apply language restrictions. We searched clinical trial registries for ongoing and recently completed trials. We searched the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/), as well as the US National Library of Medicine’s ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), via Cochrane CENTRAL. Additionally, we searched the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) Registry for any unique trials not found through the Cochrane CENTRAL search.

Searching other resources

We also searched the following.

Reference lists from identified clinical trials and review articles.

Personal communication with primary authors of identified clinical trials to retrieve unpublished data related to the published article.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal.

Selection of studies

We used Reference Manager software to remove duplicates from search results sent by the Information Specialist. Two review authors (NG, MB) independently assessed study eligibility for inclusion in this review according to pre‐specified selection criteria. When appropriate, we corresponded with investigators to clarify study eligibility. We listed excluded studies along with reason(s) for exclusion. We resolved any disagreements by discussion with the third author (DC) of the review.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (NG, MB) independently extracted data from full‐text articles using a specially designed spreadsheet/customized form to manage information. We used these forms to extract data from eligible trials. We entered and cross‐checked the data for any differences. We resolved disagreements by discussion with the third author (DC) of the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NG, MB) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool for the following domains (Higgins 2011).

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Any other bias.

We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by consultation with a third assessor. See Appendix 2 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated for categorical data relative risk, risk difference, and, if the risk difference was statistically significant, the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome with 95% confidence intervals. We analyzed continuous data using the mean difference (MD).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of randomization was the intended unit of analysis (individual neonate). We did not include cross‐over trials, as such trial designs are unlikely for the intervention studied in this review. If we should have found any cluster‐randomized controlled trials, we would have adjusted them for the designed effect using the method stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019).

Dealing with missing data

We planned to conduct the meta‐analysis based on the intention‐to‐treat analysis reported in the included studies. However, two studies excluded participants after randomization and have not reported study outcomes for the excluded participants (Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). We requested authors of all trials to provide information regarding missing data for participants or important outcomes. However, we received clarification from only one of them (Sardar 2020). This information pertained to the incidence of hypernatremia and azotemia among all infants who were randomized including those who were excluded post randomization due to development of dehydration. Therefore, the meta‐analysis was performed based on numbers as reported in the included studies. We calculated and reported the percentage lost to follow‐up if there was a discrepancy between numbers randomized and numbers analyzed in each treatment group.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the following methods to detect heterogeneity.

We assessed heterogeneity between trials by first examining the forest plot to check for overlapping confidence intervals. We then used the Chi² test to assess whether observed variability in effect sizes between studies is greater than would be expected by chance. Given that this test has low power when the number of studies included in the meta‐analysis is small, we planned to set the alpha probability at the 10% level of significance.

We used the I² statistic to ensure that pooling of data was valid. To report on results of the I² statistic, we used the following categories: less than 25% no heterogeneity, 25% to 49% low heterogeneity, 50% to 74% moderate heterogeneity, and greater than 75% high heterogeneity. If we found substantial heterogeneity, we explored reasons by performing subgroup analysis (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess publication bias by examining the degree of asymmetry of a funnel plot in RevMan 5 (RevMan 2020), and by using the statistical test proposed by Egger (Egger 1997). However, publication bias could not be assessed due to a limited number of studies. We intend to use these approaches in future updates, provided a sufficient number of studies (10 or more) are available.

Data synthesis

We conducted the analysis using RevMan 5 (RevMan 2020). We used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis in the first instance to combine data. We used a random‐effects meta‐analysis if we found important statistical heterogeneity among studies. When we judged meta‐analysis to be inappropriate, we planned to analyze and interpret individual trials separately. For estimates of typical relative risk and mean difference, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method and the inverse variance method, respectively. We planned to pool cluster‐RCTs along with parallel RCTs using the generic inverse variance method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We pre‐specified the following subgroup analyses.

Gestational age at birth (term versus preterm).

Time of the start of treatment (≤ 24 hours versus > 24 hours after birth).

Presence or absence of any respiratory support (supplemental oxygen or noninvasive/invasive ventilation) at the time of study entry.

Degree of fluid restriction (10% to 20% versus > 20% restriction of total fluids per day).

We planned to investigate statistical heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses to determine possible reason(s).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of decisions if we found a sufficient number of trials. We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to determine if findings were affected by including only studies using adequate methods, defined as adequate randomization and allocation concealment, blinding of intervention and measurement, and less than 10% loss to follow‐up.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the certainty of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes.

Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy (hours).

Incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L) during and at the end of the intervention period (proportions).

Incidence of hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 40 mg/dL) during and at the end of the intervention period (proportions).

Incidence of endotracheal ventilation (proportions) (for infants receiving no support or noninvasive support at the time of study entry).

Incidence of noninvasive (nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation) respiratory support.

Length of hospital stay (in days).

Cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age (%).

Two review authors (MB, NG) independently assessed the certainty of evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create Table 1 to report the certainty of evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence as one of four grades.

High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Results

Description of studies

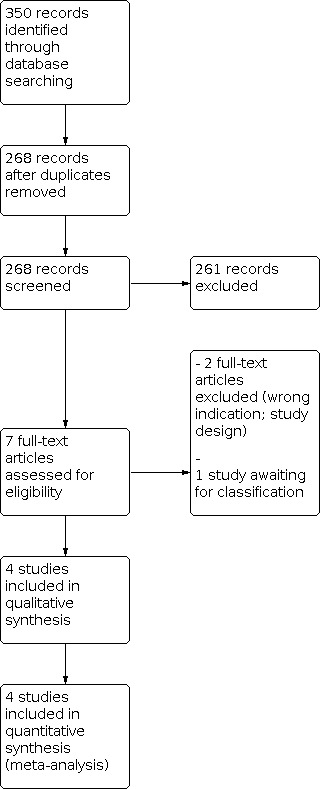

We have provided results of the search for this review in the study flow diagram (Figure 1). See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

The literature search run in December 2019 identified 350 references (Figure 1). After screening, we included in the review four RCTs enrolling 317 infants (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). We excluded two studies (CTRI/2019/04/018661; Dehdashtian 2014), and one study is awaiting classification because the abstract and the full text were not available (Stroustrup 2010). We identified no ongoing trials.

Included studies

The four studies included in the review are described below (see also Table 2 and Characteristics of included studies).

1. Overview of the four included trials.

|

Study ID (no. of infants randomized) |

Country |

Population at study entry |

GA in the fluid restriction group | GA in the control group |

Fluid restriction group |

Control group |

Infants lost to follow‐up/dropouts | Number of infants analyzed | Fluid increased |

|

Akbarian Rad 2018 (70) |

Iran | 34+0 to 41+6; tachypnea for at least 6 hours |

29% and 71% of infants born preterm and term, respectively | 55% and 45% of infants born preterm and term, respectively | DOL 1: 50 and 65 mL/kg/d for term and preterm infants, respectively |

DOL 1: 65 and 80 mL/kg/d for term and preterm infants, respectively | n = 5 (I = 3; C = 2) |

n = 65 (I = 31; C = 34) |

|

|

Eghbalian 2018 (80) |

Iran | 37+0 to 41+6; tachypnea for at least 12 hours |

75% of infants born at 37 to 38 weeks' GA | 75% of infants born at 37 to 38 weeks' GA | 40, 60, and 80 mL/kg/d of dextrose 10% on DOL 1, 2, and 3, respectively | 60, 80, and 100 mL/kg/d of dextrose 10% on DOL 1, 2, and 3, respectively | n = 0 | n = 80 (I = 40; C = 40) |

|

|

Sardar 2020 (100) |

India | 34+0 to 41+6; < 6 hours old (1) |

Mean 36.6 (SD 2.0) | Mean 36.9 (SD 1.9) | 40, 60, and 80 mL/kg/d of dextrose 10% on DOL 1, 2, and 3, respectively | 60, 80, and 100 mL/kg/d of dextrose 10% on DOL 1, 2, and 3, respectively | n = 8 (I = 4; C = 4) |

n = 92 (I = 46; C = 46) |

|

|

Stroustrup 2012 (67) |

USA | 34+0 to 41+6; < 12 hours old (2) |

Mean 35.8 (SD 1.6) | Mean 36.4 (SD 1.5) | DOL 1: 40 and 60 mL/kg/d for term and preterm infants, respectively | DOL 1: 60 and 80 mL/kg/d for term and preterm infants, respectively | n = 3 (I = 2; C = 1) |

n = 64 (I = 32; C = 32) |

|

C: control group; DOL: day of life; GA: gestational age; I: intervention group; SD: standard deviation.

Notes:

- In Sardar 2020, 5 minutes Apgar ≥ 8: 98% and 85% in fluid restriction and control groups, respectively (P = 0.026).

- In Stroustrup 2012, exposure to antenatal steroids: 22% and 3% in fluid restriction and control groups, respectively (P = 0.023).

- Post‐randomization exclusion occurred in 3 out of 4 studies. In Akbarian Rad 2018, all 5 infants had urine output < 1 mL/kg/hr causing post‐randomization exclusion. In Sardar 2020, 2 infants in each group had hypoglycemia, 2 in intervention group and 1 in control group developed dehydration, and 1 infant in control group developed air leak, thus causing 8 infants to be excluded post randomization. In Stroustrup 2012, 3 infants were excluded post randomization due to non‐TTN respiratory diagnosis.

Akbarian Rad 2018 enrolled late preterm, term, and post‐term neonates with TTN. The diagnosis of TTN was based on the presence of tachypnea (respiratory rate > 60 per minute) and at least one radiological sign suggestive of the diagnosis. If chest X‐ray was normal, the diagnosis of TTN was made if the Silverman Anderson score for respiratory distress was 4 or greater and the neonate was hospitalized within six hours of birth (Silverman 1956). The level of respiratory support provided by oxygen hood at admission did not differ significantly between the two groups (P = 0.147); however, the number of infants on oxygen hood in each group is not provided in the article.

Neonates in the restricted fluid group received 50 mL/kg if born at term or post‐term gestation, and 65 mL/kg if born at late preterm gestation. Neonates in the standard fluid group received 65 mL/kg if born at term or post‐term gestation, and 80 mL/kg if born at late preterm gestation. Fluid intake was increased by 20 mL/kg every subsequent day to reach a maximum of 150 mL/kg in term and post‐term neonates, and 180 mL/kg in late preterm neonates. An additional 10% of fluid was given if the baby was under a radiant warmer or was receiving phototherapy. Enteral feeds were added when the baby was "stable," and intravenous fluid intake was adjusted to target the planned total fluid intake. Mode of delivery, gestation category, and gender distributions were comparable in the two study groups. No information is provided about other baseline characteristics nor actual fluid intake in the two study groups. No information is provided about criteria for starting or stopping respiratory support. In this study, the primary outcome has not been defined or used for the sample size calculation. Outcomes reported include respiratory rate and distress score at 24 hours, duration of hospitalization (in days), duration of respiratory support (in hours), and level of respiratory support needed based on the need for the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO₂).

Eghbalian 2018 enrolled neonates born at 37 to 41 weeks' gestation who were hospitalized with TTN within three days of birth. The diagnosis of TTN was based on the following criteria: tachypnea (respiratory rate > 60 per minute) continuing for at least 12 hours, prominent central pulmonary vessels, thickening of the interlobar fissure on chest X‐ray, and respiratory alkalosis in arterial blood gas analysis. Neonates with congenital malformations, other causes of respiratory distress, polycythemia, electrolyte imbalance suggestive of dehydration, or acute kidney injury were excluded. No information on the presence or absence of any respiratory support at the time of study entry is available.

Neonates assigned to the restricted fluid group received 40, 60, and 80 mL/kg of intravenous fluid on the first, second, and third days of birth, respectively. Neonates assigned to the standard fluid group received 60, 80, and 100 mL/kg of intravenous fluid on the first, second, and third days of birth, respectively. The intravenous fluid used in both groups was 10% dextrose to which 3 mEq/kg/d of sodium and 2 mEq/kg/d of potassium had been added from the second day of birth. An additional 20 mL/kg/d was given if the baby was under a radiant warmer. Gestation category and birth weight were comparable in the two study groups. Study authors indicate that the proportion of male infants was significantly higher in the restricted fluid group. However, the numbers for gender distribution in the baseline characteristics table do not sum to the total neonates enrolled in the study, indicating missing information or typographical error. No information about other baseline characteristics and actual fluid intake in the two study groups is provided. No information about criteria for starting or stopping respiratory support is provided. The primary outcome of the study was duration of hospitalization. Other outcomes included duration of oxygen therapy and need for and duration of different types of respiratory support.

Sardar 2020 enrolled neonates born at 34 to 41 weeks' gestation who weighed more than 1500 grams, had TTN, and needed CPAP as respiratory support within six hours of birth. The diagnosis was made if respiratory distress started within six hours of birth, with the chest‐X ray suggestive of at least one radiological sign of TTN. Neonates with congenital malformations, air leaks, hemodynamic instability, and alternative causes of respiratory distress were excluded. Infants with TTN for whom oxygen therapy has failed who were on nasal CPAP support within six hours of birth were enrolled; however, baseline distribution of the level of CPAP in both groups is missing from the article.

Neonates assigned to the restricted fluid group received 40, 60, and 80 mL/kg of intravenous fluid on the first, second, and third days of birth, respectively. Neonates assigned to the standard fluid group received 60, 80, and 100 mL/kg of intravenous fluid on the first, second, and third days of birth, respectively. The intravenous fluid used in both groups was 10% dextrose to which electrolytes were added from 48 hours of birth. Fluid status of enrolled neonates was monitored by daily measurement of serum sodium, body weight, urine output, and urine specific gravity. The planned daily increment in fluid intake was made only if these measurements indicated no dehydration or fluid overload. Neonates were excluded (four from each study group) from the study after enrollment and were not included in the analysis if they exhibited dehydration, fluid overload, or hypoglycemia. All important baseline variables were comparable in the two groups. However, neonates in the restricted fluid group were significantly less likely to have a low (≤ 7) Apgar score at five minutes of age. No information is provided about actual fluid intake in the two study groups. Information about criteria for starting or stopping respiratory support is provided. The primary outcome of the study was the duration of CPAP support. Other outcomes included incidence of CPAP failure, duration of the oxygen requirement, and incidence of common neonatal morbidities.

Stroustrup 2012 enrolled neonates born at 34 to 41 weeks' gestation who developed TTN within 12 hours of birth. The diagnosis of TTN was made in the presence of respiratory distress (flaring, grunting, and accessory muscle use with or without hypoxia) and chest X‐ray findings consistent with the diagnosis. Neonates with major congenital malformations or alternate respiratory diagnosis and those undergoing workup for sepsis and with air leaks were excluded. Infants whose oxygen saturation was ≤ 95% and/or who had hypercapnia were started on respiratory support (nasal CPAP, high‐flow nasal cannula therapy, or nasal cannula) before or at the time of enrollment, but the exact number of infants and their respective distribution of respiratory support are not known.

Neonates in the restricted fluid group received 40 mL/kg if born at term gestation and 60 mL/kg if born at preterm gestation. Neonates in the standard fluid group received 60 mL/kg if born at term gestation and 80 mL/kg if born at preterm gestation. Total fluid intake was calculated as a combination of intravenous and enteral fluid intake. Fluid intake was increased by 20 mL/kg every subsequent day to reach a maximum of 150 mL/kg or ad libitum feeding. Important baseline characteristics were comparable in the two study groups. However, a significantly higher proportion of neonates in the standard fluid intake group received antenatal steroids. In the subgroup of neonates with severe TTN (defined as the need for respiratory support for longer than 48 hours), mean gestation was significantly lower. No information is provided about the type of fluid administered in the two study groups. However, information about actual fluid intake in the two study groups during the first 72 hours of birth is provided. Criteria for starting respiratory support are provided. The mode of respiratory support and decisions about weaning and discontinuation of respiratory support were determined by the treating team. The primary outcome of the study was duration of respiratory support. Other study outcomes included time from birth to first enteral feed, duration of NICU stay, total cost of hospitalization, and component costs including physician, direct, and indirect costs.

Excluded studies

We excluded two studies: one because of the wrong indication (CTRI/2019/04/018661), and the other because of before‐after study design (Dehdashtian 2014).

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias is discussed below and is summarized in Included studies, Figure 2, and Figure 3.

2.

Figure 2. Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Figure 3. Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Two of the four studies included in the review had high risk of selection bias (Akbarian Rad 2018; Stroustrup 2012). Neonates were alternately assigned to receive restricted or standard fluid therapy in both these studies (Akbarian Rad 2018; Stroustrup 2012). The third study used a computer‐generated random number sequence for treatment assignment and serially numbered sealed opaque envelopes for allocation concealment (Sardar 2020). The remaining study used a table with block randomization for generating random number sequence (Eghbalian 2018); however, the method used to ensure allocation concealment is not reported.

Blinding

Two of the four studies included in the review had high risk of performance and detection bias (Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). In both these studies, the healthcare teams providing clinical care and assessing the outcome were not blinded. In Akbarian Rad 2018, the healthcare team that provided clinical care and made decisions about starting, weaning, or stopping respiratory support was not blinded; therefore we judged this study to have high risk of performance bias. However, the nurses who recorded outcomes were blinded to the treatment assignment, hence the study was judged as having low risk of bias. In Eghbalian 2018, the decision to initiate or terminate respiratory support was made by healthcare workers who were blinded to the treatment assignment. Therefore, this study was judged to have low risk of performance bias. No information about the way the outcome was assessed is available; therefore we judged this study as having unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies did not provide information about the flow of trial participants (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018). From information available in the manuscript, it can be deduced that all enrolled participants had been included in the analysis. Therefore, these two studies were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias. In Sardar 2020 and Stroustrup 2012, participants were excluded after enrollment and randomization. Sardar 2020 excluded three and four participants from intervention and control groups, respectively, post randomization and did not include them in the analysis. Reasons for exclusion included development of complications (e.g. dehydration, hypoglycemia) in both groups, which may be related to the study intervention. However, reasons for exclusion are quite explicit, almost equal in both groups, and attrition is less than 10% among total enrolled participants; therefore this study is assessed to be at low risk of attrition bias. Stroustrup 2012 excluded participants from the analysis if an alternative cause of respiratory distress was found after enrollment and randomization. A total of two participants from the control group and one from the intervention group were excluded. Although this study practiced neither allocation concealment nor blinding of investigators, the decision of post‐randomization exclusion may be influenced by knowledge of the treatment assignment for both the participant excluded and the next participant in the randomization sequence. However, the reasons for exclusion are quite explicit, and attrition is less than 10% among total enrolled participants; therefore this study is assessed to be at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All four studies included in this review report outcomes related to the initiation and duration of various modes of respiratory support (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). Three of the included studies were registered at one of the available clinical trial registers (Akbarian Rad 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). We were able to access the registered protocol for these three registered studies (Akbarian Rad 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). All four studies have been judged to be at low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We have not identified any other potential source of bias in any of the four studies included in the review (Akbarian Rad 2018Eghbalian 2018Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). No external funding has been declared by study authors in the three studies (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018; Sardar 2020). Stroustrup 2012 was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, in the USA.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We identified four trials that enrolled a total of 317 neonates with TTN to compare restricted and standard fluid therapies (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012).

See Table 1.

Primary outcome

Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy

Three trials reported this outcome (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018; Sardar 2020).

Akbarian Rad 2018 reported only a measure of central tendency (no information whether mean or median) and not of dispersion (i.e. standard deviation) for the duration of oxygen therapy (21.35 hours versus 31 hours; P = 0.048). Therefore, the data from this study could not be used to calculate the pooled effect size. Pooled data from the other two studies ‐ Eghbalian 2018 and Sardar 2020 ‐ show no significant difference in duration of oxygen therapy between the two groups (mean difference [MD] ‐12.95 hours, 95% confidence interval [CI] ‐32.82 to 6.92 hours) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to risks of selection and detection bias. We downgraded the evidence due to inconsistent results (heterogeneity: Chi² = 43.34, df = 1 [P = 0.20]; I² = 98%, random‐effects model) and imprecision due to suboptimal information size, as only two small trials contributed to the pooled effect size. This high heterogeneity (I² = 98%) is the result of grossly different mean values for the duration of supplemental oxygen therapy in the two studies (three to six hours in Eghbalian 2018 versus 29.5 to 40 hours in Sardar 2020). Moreover, for Eghbalian 2018, we have converted units of the duration of oxygen therapy from days to hours, so as to make data uniform for the meta‐analysis.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 1: Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy

4.

Figure 4. Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 1.1: Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of hypernatremia

Only one trial reported the incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L) during or at the end of the intervention (Sardar 2020). The risk of hypernatremia was not different in the two groups (risk ratio [RR] 4.00, 95% CI 0.46 to 34.54; risk difference [RD] 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.14) (Analysis 1.2). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to risk of detection bias and upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI for the pooled risk ratio reaching points of clinically significant reduction or increase in the outcome.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 2: Incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L) during and at end of intervention period

Incidence of azotemia

Only one trial reported the incidence of azotemia (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL) during or at the end of the intervention (Sardar 2020). Three neonates developed this outcome in the study, and all these neonates belonged to the restricted fluid group. The risk of azotemia was not different in the two groups (RR 7.00, 95% CI 0.37 to 132.10; RD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.13) (Analysis 1.3). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to the risk of detection bias and upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI of the pooled risk ratio reaching points of clinically significant reduction or increase in the outcome.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 3: Incidence of azotemia (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL) during and at end of intervention period

Incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment by phototherapy

Two studies reported this outcome (Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). The pooled incidence of hyperbilirubinemia was comparable in the two groups (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.48; RD 0.04; 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.18) (Analysis 1.4). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to high risk of selection bias in one study (Stroustrup 2012), high risk of detection bias in both studies, and upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI of the pooled risk ratio reaching points of clinically significant reduction or increase in the outcome.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 4: Incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment by phototherapy

Incidence of hypoglycemia

Two studies reported this outcome (Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). The pooled incidence of hypoglycemia was comparable in the two groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.15 to 6.82; RD 0.00; 95% CI: ‐0.05 to 0.05) (Analysis 1.5). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to high risk of selection bias in one study (Stroustrup 2012), high risk of detection bias in both studies, and upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI of the pooled risk ratio reaching points of clinically significant reduction or increase in the outcome.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 5: Incidence of hypoglycemia

Need for invasive ventilation

Three trials reported this outcome (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018; Sardar 2020). The pooled incidence was comparable in two groups (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.24 to 2.23; RD ‐0.02; 95% CI: ‐0.07 to 0.04) (Analysis 1.6; Figure 5). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to risk of detection bias and upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI of the pooled risk ratio reaching points of clinically significant reduction or increase in the outcome.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 6: Need for invasive ventilation

5.

Figure 5. Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 1.6: Need for invasive ventilation

Need for noninvasive (nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation) respiratory support

Nasal CPAP was administered as part of the treatment algorithm in all four included studies. However, in Stroustrup 2012, the number of neonates who needed nasal CPAP is not reported. The need for CPAP was one of the inclusion criteria in Sardar 2020. The remaining two trials reported this outcome (Akbarian Rad 2018; Eghbalian 2018). The pooled incidence of the need for noninvasive respiratory support was not different in the two groups (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.14 to 1.17; RD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.01) (Analysis 1.7). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to risks of selection and detection bias and upper and lower bounds of the 95% CI of the pooled risk ratio reaching points of clinically significant reduction or increase in the outcome.

Length of hospital stay

Akbarian Rad 2018 and Eghbalian 2018 reported this outcome. Akbarian Rad 2018 reported only a measure of central tendency (no information whether mean or median) and not of dispersion (i.e. standard deviation) for length of hospital stay (5.65 days versus 6.78 days; P = 0.02). Therefore, the data from this study could not be used to calculate the pooled effect size. The data from Eghbalian 2018 show a significantly lower duration of hospitalization in the restricted fluids group (MD ‐0.92 days, 95% CI ‐1.53 to ‐0.31 days) (Analysis 1.8). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to risks of selection and detection bias and imprecision due to small sample size, as only one trial has contributed to the pooled effect size.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 8: Length of hospital stay

Cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age

Two studies reported this outcome (Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). Cumulative weight loss was comparable in the two groups (MD 0.24, 95% CI ‐1.60 to 2.08) (Analysis 1.9). We judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be very low due to high risk of selection bias in one study (Stroustrup 2012), as well as high risk of detection bias in both studies. We downgraded the evidence due to inconsistent results (heterogeneity: Chi² = 8.98, df = 1 [P = 0.80]; I² = 89%; random‐effects model) and imprecision due to low information size, as only two trials contributed to the pooled effect size.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 9: Cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age (%)

Only Stroustrup 2012 reported on age (in hours) at the start of the first enteral feed. The median (interquartile range) age was 35 (23; 44) and 31 (21; 51) hours in restricted and standard fluid therapy groups, respectively, with the difference being statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.67). However, no data were reported in any studies for the following outcome: age (in hours/days) of attainment of full enteral feeds.

Subgroup analysis

We were unable to conduct any of the planned subgroup analyses as the review included only four trials with limited information.

Three out of four studies included both term and late preterm infants (Akbarian Rad 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). However, except for one study (Sardar 2020), others have not separately reported data on late preterm infants. Therefore, the subgroup analysis based on gestational age could not be performed.

All infants were randomized and started treatment within 12 hours after birth. Therefore, the subgroup analysis based on time of the start of treatment (≤ 24 hours versus > 24 hours) could not be done.

Infants were receiving different types of respiratory support at the time of enrollment and its exact distribution is not reported. Sardar 2020 enrolled only those infants for whom oxygen therapy had failed who were on nasal CPAP support. Thus, the subgroup analysis based on type of respiratory support was not possible.

Infants in the fluid‐restricted group received 15 to 20 mL/kg/d less fluid than the control group for varying durations across all four studies. This restriction varied from ~ 9% (15 mL/kg/d/ 70 mL/kg/d) to 33% (20 mL/kg/d/60 mL/kg/d) on different days of life, depending on the absolute volume of total fluid required. Hence, no subgroup analysis based on the degree of fluid restriction (≤ 20% versus > 20%) could be performed.

Sensitivity analysis

We could not perform sensitivity analysis due to the limited number of included trials. None of the included trials was free of bias to be included in the sensitivity analysis under the category "adequate methodology" as defined in the review protocol.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We evaluated the efficacy of fluid restriction in the management of transient tachypnea of the newborn in term and preterm (< 37 completed weeks) infants during the first week after birth. Four trials for 317 infants met the inclusion criteria of this review; one trial included only term infants (Eghbalian 2018), whereas three studies included both term and late preterm infants (Akbarian Rad 2018; Sardar 2020; Stroustrup 2012). In all trials, 40 to 50 and 60 to 65 mL/kg/d were administered to fluid restriction and control groups, respectively, followed by an increase of 20 mL/kg/d for all infants (Table 2). Two trials reported the primary outcome of this review (i.e. duration of supplemental oxygen therapy), which was comparable between the two groups. Among the secondary outcomes of this review, two trials reported length of hospital stay, which was shorter by nearly one day among infants with fluid restriction; 12 events of endotracheal ventilation were reported in three trials, without differences between the two groups.

Two studies were excluded: one because of the wrong indication (CTRI/2019/04/018661), and the other because of before‐after study design (Dehdashtian 2014). We identified no ongoing trials.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Available evidence was insufficient to show whether fluid restriction is effective in the management of transient tachypnea of the newborn. Available data were insufficient to assess the primary outcome of this review and other important outcomes such as length of hospital stay and need for endotracheal ventilation. We could not perform a priori subgroup analysis (gestational age, time of the start of treatment, presence of any respiratory support, degree of fluid restriction) to detect differential effects because of the paucity of included trials.

Quality of the evidence

The overall certainty of evidence was very low. The main limitation of the certainty of evidence was linked to imprecision of the estimate due to the paucity of included trials and small sample sizes (see Table 1). Trials insufficiently reported most items for risk of bias. In addition, the primary outcome and the outcome cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age were affected by high heterogeneity.

Potential biases in the review process

It is unlikely that the literature search applied to this review may have missed relevant trials, thus we are confident that this systematic review summarizes all presently available evidence from randomized trials on fluid restriction for transient tachypnea of the newborn. One study was classified as awaiting classification due to lack of information (Stroustrup 2010). We excluded two trials: one because of the wrong indication (CTRI/2019/04/018661), and the other because of a before‐after study design (Dehdashtian 2014). The methods of the review were designed to minimize the introduction of additional bias. Two review authors independently completed data screening, data extraction, and "risk of bias" rating. We obtained additional information on the outcomes included in Analysis 1.2 and Analysis 1.3 from one of the study author's (Sardar 2020). We did not explore possible publication bias through generation of funnel plots because fewer than 10 trials met the inclusion criteria of this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of other reviews that address the same clinical question. We described the characteristics of clinical trials that have been published.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found limited evidence to establish the benefits and harms of fluid restriction in the management of transient tachypnea of the newborn. Given the very low certainty of available evidence, it is impossible to determine whether fluid restriction is safe or effective for treatment of transient tachypnea of the newborn.

Implications for research.

Although the certainty of evidence is very low, given the simplicity of intervention with possible benefits, a well‐designed, adequately powered trial is justified. It is also worth investigating the effects of fluid restriction in the subgroup of neonates with transient tachypnea who had not received antenatal steroids. Efforts should be made to standardize respiratory support management, as it may not be possible to blind the clinical care team about fluid therapy. Given the uncertainty of evidence on possible adverse events including hypernatremia, hypoglycemia, polycythemia, and hyperbilirubinemia, it would be of interest to explore whether fluid restriction increases their risk; in this regard, observational studies would be quite useful in generating safety data for this intervention.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2015 Review first published: Issue 2, 2021

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for guidance from the Protocol Development Workshop for a Cochrane Systematic Review organized by the South Asian Cochrane Network & Centre, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India, from February 3, 2014, to February 7, 2014.

We would like to thank Cochrane Neonatal, including Colleen Ovelman, Managing Editor; Jane Cracknell, Assistant Managing Editor; Roger Soll, Co‐coordinating Editor; and Bill McGuire, Co‐coordinating Editor, who provided editorial and administrative support. Carol Friesen, Information Specialist, designed and ran the literature searches.

Sarah Hodgkinson and Jeffrey Horbar peer‐reviewed and offered feedback on this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods

The RCT filters have been created using Cochrane's highly sensitive search strategies for identifying randomized trials (Higgins 2019). The neonatal filters were created and tested by the Cochrane Neonatal Information Specialist.

CENTRAL via CRS Web

Date searched: December 6, 2019 Terms: 1"transient tachypnea" AND CENTRAL:TARGET 2"transient tachypnoea" AND CENTRAL:TARGET 3"wet lung" AND CENTRAL:TARGET 4(TTN):TI AND CENTRAL:TARGET 5(TTN):AB AND CENTRAL:TARGET 6#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 7MESH DESCRIPTOR Infant, Newborn EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET 8infant or infants or infant's or "infant s" or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birth weight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW or ELBW or NICU AND CENTRAL:TARGET 9#8 OR #7 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 10#9 AND #6

MEDLINE via Ovid

Date ranges: 1946 to December 6, 2019 Terms: 1. "transient tachypnea".mp. 2. "transient tachypnoea".mp. 3. "wet lung".mp. 4. TTN.ti,ab. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. exp infant, newborn/ 7. (newborn* or new born or new borns or newly born or baby* or babies or premature or prematurity or preterm or pre term or low birth weight or low birthweight or VLBW or LBW or infant or infants or 'infant s' or infant's or infantile or infancy or neonat*).ti,ab. 8. 6 or 7 9. randomized controlled trial.pt. 10. controlled clinical trial.pt. 11. randomized.ab. 12. placebo.ab. 13. drug therapy.fs. 14. randomly.ab. 15. trial.ab. 16. groups.ab. 17. or/9‐16 18. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 19. 17 not 18 20. 8 and 19 21. randomi?ed.ti,ab. 22. randomly.ti,ab. 23. trial.ti,ab. 24. groups.ti,ab. 25. ((single or doubl* or tripl* or treb*) and (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab. 26. placebo*.ti,ab. 27. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 28. 7 and 27 29. limit 28 to yr="2018 ‐Current" 30. 20 or 29 31. 5 and 30

CINAHL via EBSCOhost

Date ranges: 1981 to December 6, 2019 Terms: ("transient tachypnea" OR "transient tachypnoea" OR "wet lung" OR TTN) AND (infant or infants or infant’s or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birth weight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW) AND (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR randomised OR placebo OR clinical trials as topic OR randomly OR trial OR PT clinical trial)

ISRCTN

Date searched: December 6, 2019 Terms: Condition: Transient tachypnea AND Participant age range: Neonate Condition: transient tachypnoea AND Participant age range: Neonate Condition: Wet lung AND Participant age range: Neonate

Appendix 2. "Risk of bias" tool

1. Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

For each included study, we categorized the method used to generate the allocation sequence as:

low risk (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk.

2. Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). Was allocation adequately concealed?

For each included study, we categorized the method used to conceal the allocation sequence as:

low risk (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk.

3. Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?

For each included study, we categorized the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We categorized the methods as:

low risk, high risk, or unclear risk for participants; and

low risk, high risk, or unclear risk for personnel.

4. Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented at the time of outcome assessment?

For each included study, we categorized the methods used to blind outcome assessment. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We categorized the methods as:

low risk for outcome assessors;

high risk for outcome assessors; or

unclear risk for outcome assessors.

5. Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations). Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

For each included study and for each outcome, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion when reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. When sufficient information was reported or supplied by trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses. We categorized the methods as:

low risk (< 20% missing data);

high risk (≥ 20% missing data); or

unclear risk.

6. Selective reporting bias. Are reports of the study free of the suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. For studies in which study protocols were published in advance, we compared pre‐specified outcomes versus outcomes eventually reported in the published results. If the study protocol was not published in advance, we contacted study authors to gain access to the study protocol. We assessed the methods as:

low risk (when it is clear that all of the study's pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk (when not all of the study's pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified outcomes of interest and are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); or

unclear risk.

7. Other sources of bias. Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias?

For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias (e.g. whether a potential source of bias was related to the specific study design, whether the trial was stopped early due to some data‐dependent process). We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as:

low risk;

high risk; or

unclear risk.

If needed, we explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Restricted versus standard fluid management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Duration of supplemental oxygen therapy | 2 | 172 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐12.95 [‐32.82, 6.92] |

| 1.2 Incidence of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mEq/L) during and at end of intervention period | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.00 [0.46, 34.54] |

| 1.3 Incidence of azotemia (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL) during and at end of intervention period | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.00 [0.37, 132.10] |

| 1.4 Incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment by phototherapy | 2 | 156 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.79, 1.48] |

| 1.5 Incidence of hypoglycemia | 2 | 164 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.15, 6.82] |

| 1.6 Need for invasive ventilation | 3 | 242 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.24, 2.23] |

| 1.7 Incidence of noninvasive (nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation) respiratory support | 2 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.14, 1.17] |

| 1.8 Length of hospital stay | 1 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.92 [‐1.53, ‐0.31] |

| 1.9 Cumulative weight loss at 72 hours of age (%) | 2 | 156 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [‐1.60, 2.08] |

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Restricted versus standard fluid management, Outcome 7: Incidence of noninvasive (nasal CPAP or nasal ventilation) respiratory support

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Akbarian Rad 2018.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Quasi‐randomized controlled trial, in 2 NICUs in Iran | |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions |

Experimental group

Control group

Then increase of 20 mL fluids per day until overall intake of fluids reached 150 mL per kg for term and post‐term neonates and 170 mL per kg of body weight for late preterm neonates, or the same amount was taken orally For neonates under a radiant warmer or receiving phototherapy, 10% of total fluid was added for insensible water loss |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Not a randomized trial. A total of 70 infants were randomized (intervention group 34; control group 36); however, 3 infants in the intervention group and 2 infants in the control group were excluded post randomization due to urine output < 1 mL/kg/hr. Finally a total of 65 infants were analyzed: 31 in the intervention group and 34 in the control group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: "the cases in each treatment center were placed by the order of every other case in experimental and control groups" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: "the cases in each treatment center were placed by the order of every other case in experimental and control groups" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All Outcomes | High risk | Quote: "a checklist for demographic information and study variables included the level of daily respiratory distress score, respiratory rate instantly after hospitalization and 24 hours later, and respiratory support was completed by a trained nurse. During the study, the trained nurse had no information of the control and experimental group” It indirectly seems that apart from nurses who collected the data, no other personnel were blinded to the intervention |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All Outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "a checklist for demographic information and study variables included the level of daily respiratory distress score, respiratory rate instantly after hospitalization and 24 hours later,and respiratory support was completed by a trained nurse. During the study, the trained nurse had no information of the control and experimental group" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All Outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "however, in the present study three subjects from the experimental group and two cases from the control group suffered from this condition and were excluded from the investigation" This condition means urine volume decreased to less than 1 mL/kg/hr |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported in the protocol are presented in the article too |

| Other bias | Low risk | None |

Eghbalian 2018.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial; neonatal intensive care unit of Besat and Fatemieh Hospitals, Iran, 2016 to 2017 | |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions |

In both groups: sodium chloride 3 mEq/kg/d and potassium chloride 2 mEq/kg/d was prescribed for patients from the second day of life; 20 mL/kg/d of dextrose 10% was added to solution if patients were under a radiant warmer |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|