Abstract

Background

Self‐harm (SH; intentional self‐poisoning or self‐injury regardless of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation) is a growing problem in most counties, often repeated, and associated with suicide. There has been a substantial increase in both the number of trials and therapeutic approaches of psychosocial interventions for SH in adults. This review therefore updates a previous Cochrane Review (last published in 2016) on the role of psychosocial interventions in the treatment of SH in adults.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychosocial interventions for self‐harm (SH) compared to comparison types of care (e.g. treatment‐as‐usual, routine psychiatric care, enhanced usual care, active comparator) for adults (aged 18 years or older) who engage in SH.

Search methods

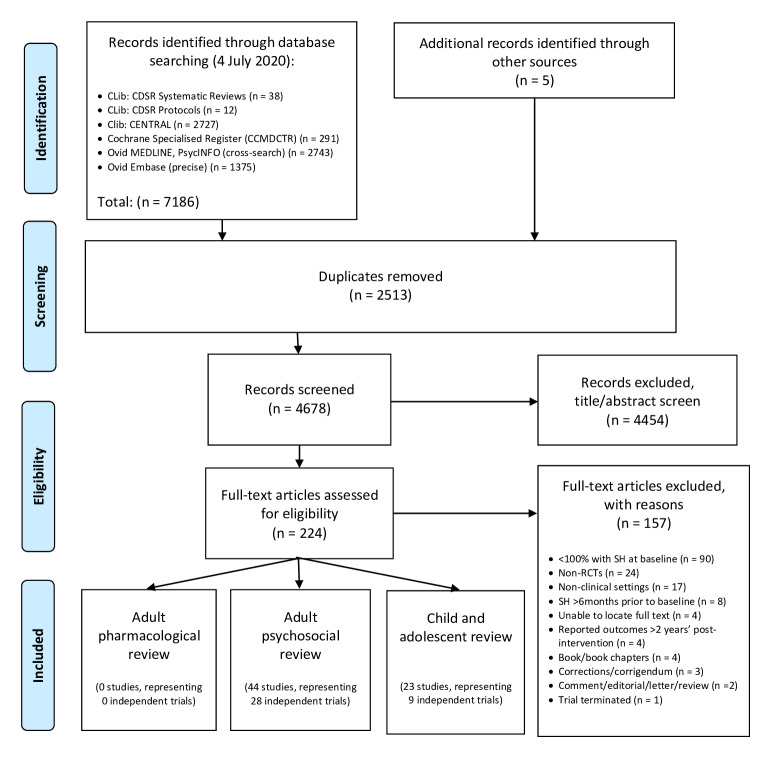

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Specialised Register, the Cochrane Library (Central Register of Controlled Trials [CENTRAL] and Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews [CDSR]), together with MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and PsycINFO (to 4 July 2020).

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing interventions of specific psychosocial treatments versus treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), routine psychiatric care, enhanced usual care (EUC), active comparator, or a combination of these, in the treatment of adults with a recent (within six months of trial entry) episode of SH resulting in presentation to hospital or clinical services. The primary outcome was the occurrence of a repeated episode of SH over a maximum follow‐up period of two years. Secondary outcomes included treatment adherence, depression, hopelessness, general functioning, social functioning, suicidal ideation, and suicide.

Data collection and analysis

We independently selected trials, extracted data, and appraised trial quality. For binary outcomes, we calculated odds ratio (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes, we calculated mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs) and 95% CIs. The overall quality of evidence for the primary outcome (i.e. repetition of SH at post‐intervention) was appraised for each intervention using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included data from 76 trials with a total of 21,414 participants. Participants in these trials were predominately female (61.9%) with a mean age of 31.8 years (standard deviation [SD] 11.7 years). On the basis of data from four trials, individual cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)‐based psychotherapy may reduce repetition of SH as compared to TAU or another comparator by the end of the intervention (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.02; N = 238; k = 4; GRADE: low certainty evidence), although there was imprecision in the effect estimate. At longer follow‐up time points (e.g., 6‐ and 12‐months) there was some evidence that individual CBT‐based psychotherapy may reduce SH repetition. Whilst there may be a slightly lower rate of SH repetition for dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) (66.0%) as compared to TAU or alternative psychotherapy (68.2%), the evidence remains uncertain as to whether DBT reduces absolute repetition of SH by the post‐intervention assessment. On the basis of data from a single trial, mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT) reduces repetition of SH and frequency of SH by the post‐intervention assessment (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.73; N = 134; k = 1; GRADE: high‐certainty evidence). A group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy may also reduce repetition of SH by the post‐intervention assessment based on evidence from two trials by the same author group (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.88; N = 83; k = 2; moderate‐certainty evidence). There is probably little to no effect for different variants of DBT on absolute repetition of SH, including DBT group‐based skills training, DBT individual skills training, or an experimental form of DBT in which participants were given significantly longer cognitive exposure to stressful events. The evidence remains uncertain as to whether provision of information and support, based on the Suicide Trends in At‐Risk Territories (START) and the SUicide‐PREvention Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal behaviors (SUPRE‐MISS) models, have any effect on repetition of SH by the post‐intervention assessment. There was no evidence of a difference for psychodynamic psychotherapy, case management, general practitioner (GP) management, remote contact interventions, and other multimodal interventions, or a variety of brief emergency department‐based interventions.

Authors' conclusions

Overall, there were significant methodological limitations across the trials included in this review. Given the moderate or very low quality of the available evidence, there is only uncertain evidence regarding a number of psychosocial interventions for adults who engage in SH. Psychosocial therapy based on CBT approaches may result in fewer individuals repeating SH at longer follow‐up time points, although no such effect was found at the post‐intervention assessment and the quality of evidence, according to the GRADE criteria, was low. Given findings in single trials, or trials by the same author group, both MBT and group‐based emotion regulation therapy should be further developed and evaluated in adults. DBT may also lead to a reduction in frequency of SH. Other interventions were mostly evaluated in single trials of moderate to very low quality such that the evidence relating to the use of these interventions is inconclusive at present.

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Male; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Confidence Intervals; Depression; Depression/therapy; Dialectical Behavior Therapy; Mentalization; Problem Solving; Psychosocial Intervention; Psychosocial Intervention/methods; Psychotherapy, Psychodynamic; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Recurrence; Secondary Prevention; Secondary Prevention/methods; Self-Injurious Behavior; Self-Injurious Behavior/psychology; Self-Injurious Behavior/therapy; Suicide Prevention

Plain language summary

Psychosocial interventions for adults who self‐harm

We have reviewed the interventional literature regarding psychosocial intervention treatment trials in the field. A total of 76 trials meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. There may be beneficial effects for psychological therapy based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches at longer follow‐up time points, and for mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT), and emotion‐regulation psychotherapy at the post‐intervention assessment. There may also be some evidence of effectiveness of standard dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) on frequency of SH repetition. There was no clear evidence of effect for case management, information and support, remote contact interventions (e.g. emergency cards, postcards, telephone‐based psychotherapy), provision of information and support, and other multimodal interventions.

Why is this review important?

Self‐harm (SH), which includes intentional self‐poisoning/overdose and self‐injury, is a major problem in many countries and is strongly linked with suicide. It is therefore important that effective treatments are developed for people who engage in SH. There has been an increase in both the number of trials and the diversity of therapeutic approaches for SH in adults in recent years. It is therefore important to assess the evidence for their effectiveness.

Who will be interested in this review?

Hospital administrators (e.g. service providers), health policy officers and third party payers (e.g. health insurers), clinicians working with people who engage in SH, the people themselves, and their relatives.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review from 2016 which found that CBT‐based psychological therapy can result in fewer individuals repeating SH whilst DBT may lead to a reduction in frequency of repeated SH. This updated review aims to further evaluate the evidence for effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for people engaging in SH with a broader range of outcomes.

Which studies were included in the review?

To be included in the review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials of psychosocial interventions for adults who had recently engaged in SH.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

Overall, there were a number of methodological limitations across the trials included in this review. We found positive effects for psychological therapy based on CBT approaches at longer follow‐up assessments, and for mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT), and emotion‐regulation psychotherapy on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. There may also be some evidence of effects for standard dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) on frequency of SH repetition. However, remote contact interventions, case management, information and support, and other multimodal interventions do not appear to have benefits in terms of reducing repetition of SH.

What should happen next?

The promising results for CBT‐based psychotherapy at longer follow‐up time points, and for MBT, group‐based emotion regulation, and DBT warrant further investigation to understand which people benefit from these types of interventions. Greater use of head‐to‐head trials (where treatments are directly compared with each other) may also assist in identifying which component(s) from these often complex interventions may be most effective.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Comparison 1.1: Individual‐based CBT‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 1.1: Individual‐based CBT‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: CBT‐based psychotherapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with CBT‐based psychotherapy | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.35 (0.12 to 1.02) | 238 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of case management on repetition of SH at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 200 per 1000 | 80 per 1000 (29 to 203) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; OR: Odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 2. Comparison 1.2: Group‐based CBT‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 1.2: Group‐based CBT‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: CBT‐based psychotherapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with CBT‐based psychotherapy | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.66 (0.36 to 1.21) | 313 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of group‐based CBT‐based psychotherapy on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 190 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (78 to 221) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CI: Confidence interval; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; OR: Odds ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 3. Comparison 2.1: DBT compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 2.1: DBT compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: DBT Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with DBT | |||||

| Repetition of SH by post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.71 (0.32 to 1.55) | 502 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate of DBT on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |

| 682 per 1000 | 604 per 1000 (407 to 769) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; DBT: Dialectical behaviour therapy; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by two levels as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for two or more of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the I2 value indicated substantial levels of heterogeneity.

3 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 4. Comparison 2.2: DBT group‐based skills training compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 2.2: DBT group‐based skills training compared to TAU or alternative psychotherapy for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: DBT group‐based skills training Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with DBT group‐based skills training | |||||

| Repetition of attempted suicide at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.66 (0.23 to 1.86) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of DBT group‐based skills training on repetition of attempted suicide at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 364 per 1000 | 274 per 1000 (116 to 515) | |||||

| Repetition of NSSI at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.88 (0.33 to 2.34) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of DBT group‐based skills training on repetition of NSSI at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 576 per 1000 | 544 per 1000 (309 to 761) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; DBT: Dialectical behaviour therapy; NSSI: Non‐suicidal self‐injury; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 5. Comparison 2.3: DBT individual therapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 2.3: DBT individual therapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: DBT individual therapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with DBT individual therapy | |||||

| Repetition of attempted suicide at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 1.46 (0.54 to 3.91) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of DBT individual therapy on repetition of attempted suicide at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 364 per 1000 | 455 per 1000 (236 to 691) | |||||

| Repetition of NSSI at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 1.29 (0.48 to 3.47) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of DBT individual therapy on repetition of NSSI at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 576 per 1000 | 636 per 1000 (394 to 825) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; DBT: Dialectical behaviour therapy; NSSI: Non‐suicidal self‐injury; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 6. Comparison 2.4: DBT prolonged exposure protocol compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 2.4: DBT prolonged exposure protocol compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: DBT prolonged exposure protocol Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with DBT prolonged exposure protocol | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.67 (0.08 to 5.68) | 18 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of DBT prolonged exposure protocol on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 333 per 1000 | 251 per 1000 (38 to 740) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; DBT: Dialectical behaviour therapy; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 7. Comparison 3: MBT compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 3: MBT compared TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: MBT Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with MBT | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.35 (0.17 to 0.73) | 134 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | We are very confident that the true effect for MBT on repetition of SH at post‐intervention lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. | |

| 492 per 1000 | 253 per 1000 (141 to 414) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MBT: Mentalisation‐based therapy; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

Summary of findings 8. Comparison 4: Emotion‐regulation psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 4: Emotion‐regulation psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.34 (0.13 to 0.88) | 83 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 | We are moderately confident that the true effect of group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy on repetition of SH at post‐intervention lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. | |

| 775 per 1000 | 539 per 1000 (309 to 752) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgradedthis domain by one level as one study was suggestive of benefit, whilst the second trial of this intervention was not.

Summary of findings 9. Comparison 5: Psychodynamic psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Psychodynamic psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Psychodynamic psychotherapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Psychodynamic psychotherapy | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.45 (0.13 to 1.56) | 170 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of psychodynamic psychotherapy on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 133 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (20 to 194) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 10. Comparison 6: Case management compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Case management compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Case management Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Case management | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.78 (0.47 to 1.30) | 1608 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of case management on repetition of SH at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 114 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (57 to 143) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the I2 value indicated substantial levels of heterogeneity.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 11. Comparison 7: Structured GP follow‐up compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Structured general practitioner (GP) follow‐up compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Structured general practitioner (GP) follow‐up Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Structured general practitioner (GP) follow‐up | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention (hospital records) | Study population | OR 1.01 (0.38 to 2.68) | 143 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of structured general practitioner (GP) follow‐up on repetition of SH (according to hospital records) at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 133 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (55 to 291) | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention (emergency records) | Study population | OR 2.56 (0.80 to 8.15) | 123 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of structured general practitioner (GP) follow‐up on repetition of SH (according to emergency records) at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 72 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 (59 to 389) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 12. Comparison 9.1: Emergency cards compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 9.1: Emergency cards compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Emergency cards Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Remote contact interventions: Emergency cards | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.82 (0.31 to 2.14) | 1039 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of emergency cards on repetition of SH at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 171 per 1000 | 145 per 1000 (60 to 306) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the I2 value indicated substantial levels of heterogeneity.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 13. Comparison 9.2: Coping cards compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 9.2: Coping cards compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Coping cards Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Coping cards | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.08 (0.00 to 1.45) | 64 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of coping cards on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 156 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (0 to 212) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 14. Comparison 9.4: Postcards compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 9.4: Postcards compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Postcards Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Remote contact interventions: Postcards | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.87 (0.62 to 1.23) | 3277 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate for postcards on repetition of SH. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |

| 132 per 1000 | 117 per 1000 (86 to 157) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the I2 value indicated substantial levels of heterogeneity.

3 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 15. Comparison 9.5: Telephone contact compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 9.5: Telephone contact compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Telephone contact Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Telephone contact | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.43 (0.04 to 5.02) | 55 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of telephone contact on repetition of SH at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 77 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (3 to 295) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 16. Comparison 9.6: Telephone contact, emergency cards, and letters compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 9.6: Telephone contact, emergency cards, and letters compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Telephone contact, emergency cards, and letters Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Remote contact interventions: Telephone contact, emergency cards, and letters | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 1.05 (0.55 to 2.00) | 303 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of telephone contact, emergency cards, and letters on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 139 per 1000 | 145 per 1000 (82 to 244) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 17. Comparison 9.7: Telephone‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 9.7: Telephone‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU or alternative psychotherapy for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Telephone‐based psychotherapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Remote contact interventions: Telephone‐based psychotherapy | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.36 (0.01 to 8.94) | 185 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of telephone‐based psychotherapy on repetition of SH at post‐intervention is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 11 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (0 to 87) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 18. Comparison 10: Provision of information and support compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 10: Provision of information and support compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Provision of information and support Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Provision of information and support | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 1.09 (0.79 to 1.50) | 1853 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate for information and support on repetition of SH by the post‐intervention assessment. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |

| 90 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (72 to 129) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Publication bias is suspected as data from some centres have not been published.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

3 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 19. Comparison 11: Other multimodal interventions compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 11: Other multimodal interventions compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Other multimodal interventions Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Other multimodal interventions | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 0.61 (0.37 to 1.30) | 1937 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate for other multimodal interventions on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |

| 252 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (111 to 305) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by two levels as the I2 value indicated considerable levels of heterogeneity.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 20. Comparison 12.5: General hospital management compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 12.5: General hospital management compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: General hospital management Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with General hospital management | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 1.03 (0.14 to 7.69) | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate of general hospital management on repetition of SH at post‐intervention. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |

| 51 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (8 to 294) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Summary of findings 21. Comparison 12.8: Long‐term therapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults.

| Comparison 12.8: Long‐term therapy compared to TAU or another comparator for self‐harm in adults | ||||||

|

Patient or population: self‐harm in adults Intervention: Long term therapy Comparison: TAU or another comparator | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with comparator | Risk with Long term therapy | |||||

| Repetition of SH at post‐intervention | Study population | OR 1.00 (0.35 to 2.86) | 80 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Our confidence in the effect estimate of long‐term therapy on repetition of SH at post‐intervention is limited.The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |

| 225 per 1000 | 225 per 1000 (92 to 454) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio; SH: Self‐harm; TAU: Treatment as usual. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 We downgraded this domain by one level as we rated any of the sources of risk of bias (as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) at high risk for one of the studies included in the pooled estimate.

2 We downgraded this domain by one level as the 95% CI for the pooled effect included the null value.

Background

Description of the condition

Self‐harm (SH), which includes all intentional acts of self‐poisoning (such as intentional drug overdoses) or self‐injury (such as self‐cutting), regardless of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation (Hawton 2003), has been a growing problem in most countries. In Australia, for example, it is estimated that there are now more than 26,000 general hospitalisations for SH each year, or a rate of 116.7 per 100,000 persons (Harrison 2014), similar to rates observed in a number of other comparable countries (Canner 2018; Griffin 2014; Morthorst 2016; Ting 2012; Wilkinson 2002). However, it is notable that rates of emergency department presentations for SH are often higher than hospitalisations (Bergen 2010; Corcoran 2015). In the UK, for example, higher rates of emergency department presentations for SH in both females (442 per 100,000) and males (362 per 100,000) have been reported (Geulayov 2016). There are also many more episodes of SH occurring in the community that do not come to the attention of clinical services. Worldwide, for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the rate of SH may be as high as 400 per 100,000, according to self‐report data (WHO 2014).

In contrast to suicide rates, rates of hospital‐presenting SH are higher in females than in males in most countries (Canner 2018; Griffin 2014; Masiran 2017; Morthorst 2016; Ting 2012; Wilkinson 2002), with rates peaking in younger adults up to 24 years of age (Perry 2012). However, this difference decreases across the life cycle (Hawton 2008). SH is less common in older people, but tends to be associated with higher suicidal intent (Hawton 2008), with consequent greater risk of suicide (Murphy 2012).

For those who present to hospital, the most common method of SH is self‐poisoning. Overdoses of analgesics and psychotropics, especially paracetamol or acetaminophen, are common in some countries, particularly high‐income countries. Self‐cutting is the next most frequent method used by those who present to hospital. However, in the community, self‐cutting and other forms of self‐injury are far more frequent than self‐poisoning (Müller 2016).

SH is often repeated. Up to one‐quarter of those who present to hospital with SH return to the same hospital within a year (Carroll 2014; Owens 2002), although some individuals may present to another hospital. Others may not present to hospital at all given that studies identifying SH repetition via self‐report suggest as many as one in five report further SH episodes following a hospital presentation (Carroll 2014). Repetition is more common in individuals who have a history of previous episodes of SH, personality disorder, psychiatric treatment, and alcohol or drug misuse (Larkin 2014). Risks of repeat SH may also be associated with method. Rates of repetition are higher among those who present to hospital following self‐injury alone (Carroll 2014; Lilley 2008), or combined self‐injury and self‐poisoning (Perry 2012), compared to those who present for self‐poisoning alone.

SH is associated with suicide. The risk of death by suicide within one year among people who present to hospital following SH varies across studies from nearly 1% to over 3% (Liu 2020; Carroll 2014; Owens 2002). This variation reflects the characteristics of the population, and the background national suicide rate. In the UK, for example, during the first year after an episode of SH, the risk of suicide is around 50 times that of the general population, with a particularly high risk in men (Carroll 2014; Geulayov 2019). One quarter of these deaths are estimated to occur within one month after discharge, and almost 50% by three months (Forte 2019), although the risk of suicide appears to remain elevated for a number of years (Geulayov 2019). A history of SH is the strongest risk factor for suicide across a range of psychiatric disorders. Repetition of SH further increases the risk of suicide (Zahl 2004).

SH and suicide are the result of a complex interplay between genetic, biological, psychiatric, psychosocial, social, cultural, and other factors. Psychiatric disorders, particularly mood and anxiety disorders, are associated with the largest contribution to the risk of both SH (Hawton 2013), and suicide in adults (Ferrari 2014). Personality disorders, including borderline personality disorder, are also associated with SH, particularly frequent repetition. Alcohol use may also play an important role (Ferrari 2014). Both psychological and biological factors appear to further increase vulnerability to SH. Psychological factors may include difficulties in problem‐solving, low self‐esteem, impulsivity, vulnerability to having pessimistic thoughts about the future (i.e. hopelessness), and a sense of entrapment. Biological factors include disturbances in the serotonergic and stress response systems (Van Heeringen 2014).

Description of the intervention

Psychological approaches used to treat adults who engage in SH typically involve brief individual‐ or group‐based psychological therapy. Treatment may vary in terms of initial management, location of treatment, continuity, intensity, and frequency of contact with therapists. There is also considerable variation among countries in the availability of services to provide such interventions. Consequently, there is no standard psychosocial treatment of SH in adults. However, in high‐income countries, treatment generally consists of a combination of assessment, support, and individual psychological therapies. In lower and middle‐income countries, aftercare more usually involves various forms of support, both face‐to‐face and via digital means.

How the intervention might work

Psychosocial interventions may address some of the underlying psychological risk factors associated with SH. The mechanisms of action of these interventions might help people improve their coping skills and tackle specific problems, manage psychiatric disorders, improve self‐esteem, increase a sense of social connectedness, and reduce impulsivity and harmful reactions to distressing situations. What follows is a description of the psychosocial interventions that are typically available for adults who engage in SH behaviours.

Cognitive behavioural therapy‐based psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)‐based psychotherapy helps people identify and critically evaluate the ways in which they interpret and evaluate disturbing emotional experiences and events, and aims to help them change the ways in which they deal with problems (Westbrook 2008). This is achieved in three steps: first, people are helped to change the ways in which they interpret and evaluate distressing emotions; second, they learn strategies to help them change the way in which they think about the meanings and consequences of these emotions; finally, with the benefit of modified interpretation of emotions and events, they are helped to change their behaviour and develop positive functional behaviour (Jones 2012).

Problem‐solving therapy (PST) is an integral part of CBT, although it can be delivered as a therapy in and of itself. PST assumes that ineffective and maladaptive coping behaviours that drive SH might be overcome by helping the person to learn skills to actively, constructively, and effectively solve the problems he or she faces in their daily lives (Nezu 2010). PST typically involves identification of the problem, generation of a range of solutions, implementation of chosen solutions based on appraisal, and the evaluation of these solutions (D'Zurilla 2010). Treatment goals include helping people to develop a positive problem‐solving orientation, use rational problem‐solving strategies, reduce the tendency to avoid problem‐solving, and reduce the use of impulsive problem‐solving strategies.

Dialectical behaviour therapy

In contrast to CBT and PST, which focus on changing behaviour and cognitive patterns, the focus of dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) is to provide people with the skills to develop an awareness and acceptance of thoughts and emotions, including painful or distressing internal experiences, without judgement or attempts to alter, suppress, avoid, or otherwise change these experiences (Lynch 2006). The primary treatment goals of DBT are three‐fold: to reduce SH, reduce behaviours that interfere with the success of treatment, such as treatment non‐adherence, and reduce any other factors that may adversely affect the person's quality of life (e.g. frequency or duration of psychiatric hospitalisations) (Linehan 1993).

Mentalisation‐based therapy

Mentalisation refers to the ability to understand the behaviour of both one's self and others in terms of motivational and emotional states (Allen 2008). Maladaptive and impulsive coping behaviours, including SH, are presumed to arise from a disrupted ability to engage in these processes. In mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT), the goal is to help people understand their emotions and behaviours, and develop strategies to regulate them to minimise the risk that they will engage in SH during times of distress.

Emotion‐regulation psychotherapy

Emotion‐regulation psychotherapy is based on DBT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and emotion‐focused therapy. It includes psychoeducation, identification of emotions, distress tolerance, emotional acceptance, behavioural activation, developing alternative coping strategies, impulse control, and identifying and clarifying valued directions.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy

Psychodynamic approaches focus on affective experiences, exploring and understanding the unconscious meaning and function of SH, and exploring and resolving difficulties in interpersonal relationships, and resulting emotional difficulties, within a therapeutic relational framework (Yakeley 2018).

Case management

"In its simplest form...case management is a means of coordinating services. Each...person is assigned a 'case manager' who is expected to assess that person's needs, develop a care plan, arrange for suitable care to be provided, monitor the quality of the care provided, and maintain contact with the person" (Marshall 2000a). Case management might have a significant role in the aftercare of people who engage in SH because many of them demonstrate poor treatment adherence, and because of the varied nature of the problems these individuals are often facing (Lizardi 2010).

Remote contact interventions

Remote contact interventions, which may include letters, brief text messages delivered by telephone, telephone calls, and postcards, are low‐resource and non‐intrusive interventions that seek to maintain long‐term contact with people. These interventions provide a sense of ongoing concern, and may mitigate the sense of social isolation reported by many people who engage in SH. They may also help to improve their knowledge about triggers and warning signs for SH, provide them with information on alternative coping behaviours to SH, and where they can access help (Milner 2016).

These interventions may also be combined with emergency card interventions, which encourage people to seek help when they feel distressed, and offer on‐demand emergency contact with psychiatric services or inpatient care. The aim is to reduce the risk of SH by facilitating rapid access to care.

Other multimodal interventions

Any of the above active psychosocial interventions may also be combined into a multimodal approach (Högberg 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

SH is a major social and healthcare problem. It represents significant morbidity, is often repeated, and is linked with suicide. Many countries now have suicide prevention strategies, all of which include a focus on improved management of people presenting with SH (WHO 2014). SH also leads to substantial healthcare costs (Sinclair 2011). In the UK, the overall median cost per episode of SH has been estimated to be £809, although costs are significantly higher for cases of combined self‐injury and self‐poisoning, compared to either self‐injury of self‐poisoning alone. These costs are mainly attributable to health‐service level contact (i.e. inpatient stay or admission to intensive care; Tsiachristas 2017).

In the UK, the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) produced the first guideline on the treatment of SH behaviours in 2004 (NCCMH 2004). This guideline focused on the short‐term physical and psychological management of SH. This guidance was updated in 2011, using interim data from a previous version of this review as the evidence base, and focused on the longer‐term psychological management of SH (NICE 2011). Subsequently, similar guidelines have been published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (Carter 2016), and German Professional Associations and Societies (Plener 2016), amongst others (Courtney 2019).

In 2021, the guidance contained in the 2011 NICE guidelines for the longer‐term management of SH will be due for updating. Therefore, we are updating our review (Hawton 2016), in order to provide contemporary evidence to guide clinical policy and practice.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychosocial interventions for self‐harm (SH) compared to comparison types of care (e.g. treatment as usual, routine psychiatric care, enhanced usual care, active comparator) for adults (aged 18 years or older) who engage in SH.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of specific psychosocial interventions versus treatment as usual, routine psychiatric care, enhanced usual care, active comparator, or a combination of these, in the treatment of adults with a recent (within six months of trial entry) presentation for self‐harm (SH). All RCTs (including cluster‐RCTs [cRCTs] and cross‐over trials) were eligible for inclusion regardless of publication type or language; however, we excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

While exact eligibility criteria often differ both within and between regions and countries (Witt 2020a), we included participants of both sexes and all ethnicities, who were 18 years and older, with a recent (i.e. within six months of trial entry) presentation to hospital or clinical services for SH.

We defined SH as all intentional acts of self‐poisoning (such as intentional drug overdoses) or self‐injury (such as self‐cutting), regardless of the degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation (Hawton 2003). This definition includes acts intended to result in death ('attempted suicide'), those without suicidal intent (e.g. to communicate distress, to temporarily reduce unpleasant feelings; sometimes termed 'non‐suicidal self‐injury'), and those with mixed motivation. We did not distinguish between attempted suicide and non‐suicidal self‐injury in this review, because there is a high level of co‐occurrence between them, and the two cannot be distinguished in any reliable way, including on levels of suicidal intent (Klonsky 2011). Lastly, the motivations for SH are complex and can change, even within a single episode (De Beurs 2018).

We excluded trials in which participants presented to clinical services for suicidal ideation only (i.e. without evidence of SH).

Types of interventions

Categorisation of the interventions in this review was informed by the trials themselves, and based on consensus discussions among members of the review team, who have considerable experience in both research and clinical practice related to SH. However, based on the previous version of this review (Hawton 2016), we anticipated the following groupings:

Interventions

These included the following:

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)‐based psychotherapy (e.g. CBT, problem‐solving therapy [PST]) versus TAU or another comparator;

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) versus TAU or another comparator;

Mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT) versus TAU or another comparator;

Emotion‐regulation psychotherapy versus TAU or another comparator;

Psychodynamic psychotherapy versus TAU or another comparator;

Case management versus TAU or another comparator;

Structured general practitioner (GP) follow‐up versus TAU or another comparator;

Brief emergency department‐based interventions versus TAU or another comparator;

Remote contact interventions versus TAU or another comparator;

Provision of information and support versus TAU or another comparator;

Other multimodal interventions versus TAU or another comparator;

Other mixed interventions versus TAU or another comparator.

Comparators

Treatment‐as‐usual (TAU) is likely to vary widely between settings and between studies conducted over different time periods (Witt 2018). Following previous work, we defined TAU as routine clinical care that the person would receive had they not been included in the study (i.e. routine care or 'standard disposition'; Hunt 2013). Other comparators could include no specific treatment, or enhanced usual care, which refers to TAU that has, in some way, been supplemented, such as by providing psychoeducation, assertive outreach, or more regular contact with case managers, and standard assessment approaches.

Types of outcome measures

For all outcomes, we were primarily interested in quantifying the effect of treatment assignment to the intervention at baseline, regardless of whether the intervention was received as intended (i.e. the intention‐to‐treat effect).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure in this review was the occurrence of repeated SH over a maximum follow‐up period of two years. Repetition of SH may be identified through self‐report, collateral report, clinical records, or research monitoring systems. As we wished to incorporate the maximum data from each trial, we included both self‐reported and hospital records of SH, where available. Preference was given to clinical records over self‐report where a trial reported both measures. We also reported proportions of participants repeating SH, frequency of repeat episodes, and time to SH repetition (where available).

Secondary outcomes

Given increasing interest in the measurement of outcomes of importance to those who engage in SH (Owens 2020b), we planned to analyse data for the following secondary outcomes (where available) over a maximum follow‐up period of two years:

Treatment adherence

This was assessed using a range of measures of adherence, including: pill counts, changes in blood measures, and the proportion of participants that both started and completed treatment.

Depression

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of depression symptoms, for example, total scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961), or scores on the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants who met defined diagnostic criteria for depression.

Hopelessness

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of hopelessness, for example, total scores on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck 1974), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reporting hopelessness.

General functioning

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of general functioning, for example, total scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; APA 2000), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reporting improved general functioning.

Social functioning

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of social functioning, for example, total scores on the Social Adjustment Scale (SAS; Weissman 1999), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reporting improved social functioning.

Suicidal ideation

This was assessed as either continuous data, by scores on psychometric measures of suicidal ideation, for example, total scores on the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI; Beck 1988), or as dichotomous data as the proportion of participants reaching a defined cut‐off for ideation.

Suicide

This included register‐recorded deaths, or reports from collateral informants, such as family members or neighbours.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches