Abstract

The classification of brain tumors has undergone numerous changes over the past half century. The World Health Organization has played a key role in the effort. Four versions of its Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System have been published. The present work chronicles their progress, placing emphasis on the historical context of the earliest effort.

Keywords: brain tumors, classification, historical development, World Health Organization

INTRODUCTION

Four editions of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System have been formulated 6, 10, 13, 18. Three were published over the past 15 years alone 6, 9, 13. Each brought with it revisions reflecting changes of concept, some fundamental, as well as minor or subtle alterations. In aggregate, they represent very substantial changes. These largely resulted from an appreciation of histologic variants and from the application of novel technologies (electron microscopy and its variants, immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization and molecular genetic methods), but were also a reflection of balance between differing philosophies. Those charged with the task of developing these classifications represented different nations, schools of thought, and, of course, attitudes toward debate and argument. Thus, it is of no surprise that not all changes have met with the unanimous approval of working group participants. Nonetheless, each edition of what came to be known as the “blue book” represented an improvement over prior efforts. Understandably, major shifts in nosology took place in earlier editions, those more recent being less fundamental, albeit necessary alterations. The evolution of concepts inherent in the process and a chronology of changes from one edition to the other are the substance of this work.

HISTORY

Early attempts to establish an internationally accepted, systematic approach to brain tumor nomenclature, such as the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) (3), Atlas of the Histology of Brain Tumors (16) and the Atlas of Gross Neurosurgical Pathology (17), were unsuccessful. Even the groundbreaking 1952 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) Fascicle—Tumors of the Central Nervous System by James W. Kernohan and George P. Sayre (5), met with limited international recognition. In 1952, a subcommittee of the WHO Expert Committee on Health Statistics published its conclusions regarding general principles underlying a statistically useful classification of human tumors of various organs (2). To assure ease and flexibility of coding, three elements of such a classification were deemed necessary, including consideration of anatomic site, histologic tumor type and degree or “grade” of malignancy.

It is noteworthy that the efforts of the WHO were both antedated and strongly influenced by the impressive achievement of the AFIP, Washington, DC. Full 27 years prior to the appearance of the first WHO “blue book”Histological Typing of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (5), the AFIP had undertaken the publication of the earliest of the large, first series of AFIP Fascicles under the auspices of the National Research Council, National Academy of Science, Subcommittee of Oncology. These were mainly the inspiration of Drs Arthur Purdy Stout of Memorial Sloan‐Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY and Lauren V. Ackerman of Barnes Hospital, St. Louis, MO. As atlases, they were lavishly illustrated to show diagnostic criteria and were accompanied by a concise and informative text. Through four series, the “fascicles” continue to be a diagnostic standard worldwide. As an aside, Dr Ackerman also contributed to the Illustrated Tumor Nomenclature published in English, French, German, Latin, Russian and Spanish by the UICC (3).

In 1956, the WHO executive board passed a resolution requesting the Director‐General to consider establishing centers worldwide charged with the development of histologic definitions and facilitating the adoption of a uniform nomenclature for tumors of various organs. In 1957, the 10th World Health Assembly endorsed the plan. That same year, the Study Group on Histological Classification of Cancer Types met in Oslo, Norway, to advise the WHO. The plan was to assemble experts, up to 10 pathologists for each center, to develop a publication replete with numerous photomicrographs of the selected tumors. To achieve the latter, the centers were charged with the production of sets of up to 100 microscopic slides illustrating these entities. By 1979, 23 centers manned by approximately 300 pathologists from 50 countries had been established.

With respect to tumors of the central nervous system (CNS), Dr Klaus J. Zülch, director of the Max‐Planck Institute for Brain Research in Cologne, Germany, was designated head of the WHO Collaborating Center for the Histologic Classification of Tumors of the CNS (19) (Figure 1). Among the 10 participants he chose to formulate a classification were three Anglo‐American neuropathologists (Figure 2), including Dr Lucien J. Rubinstein, Department of Pathology (Neuropathology), Stanford University, Stanford, CA and Dr Robert O. Barnard, Maida Vale Hospital for Nervous Disease, London, England, both London‐trained, the former under the renowned Dr Dorothy S. Russell. The three also included Dr Kenneth M. Earle of the AFIP, Washington, DC (Figure 2). In keeping with the directives of the WHO, the participants subsequently recruited 10 case reviewers including Drs John J. Kepes, University of Kansas, Kansas City, KS, David M Robertson, Queens University School of Medicine, Kingston, Ontario, Canada and J. Hume Adams, Institute of Neurological Sciences, Glasgow, Scotland (Figure 3). Dr Leslie H. Sobin of the WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, was the series editor. Exactly 100 microsections illustrative of the proposed entities were distributed to the reviewers. Largely originating in Cologne, these slides were distributed as “unknowns.” Reviewers met on two occasions (1974 and 1976), reviewed the slides, arrived at diagnoses and appended annotations. In all, the effort spanned nearly a decade. It began in 1970 when Drs Zülch, Rubinstein and Sobin met in Geneva to create a list of the tumors to be included, essentially a tentative classification. Thereafter, on two occasions (1971, 1976) the participants met in Cologne to “hammer out” details (Figure 4). At the first session, Dr Zülch acted as chairman and Dr Earle as rapporteur. Given the contentious nature of this first meeting (1971), the second (1976) session was chaired by Dr Earle whose amiable, conciliatory nature somewhat calmed the waters (Figure 5). Nonetheless, the sessions can best be described as “stormy,” there being occasional threats of withdrawal from the body.

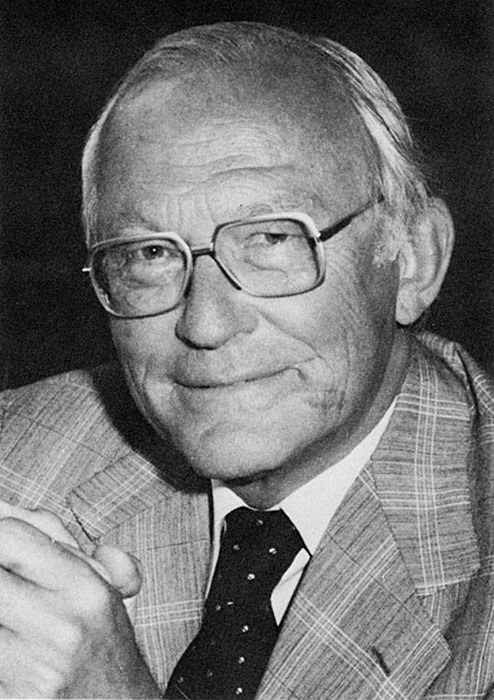

Figure 1.

Dr Karl Joachim Zülch (1910–1988), organizer of the first World Health Organization Working Group meeting and author of the first “blue book,” Histologic Typing of Tumours of the Central Nervous System.

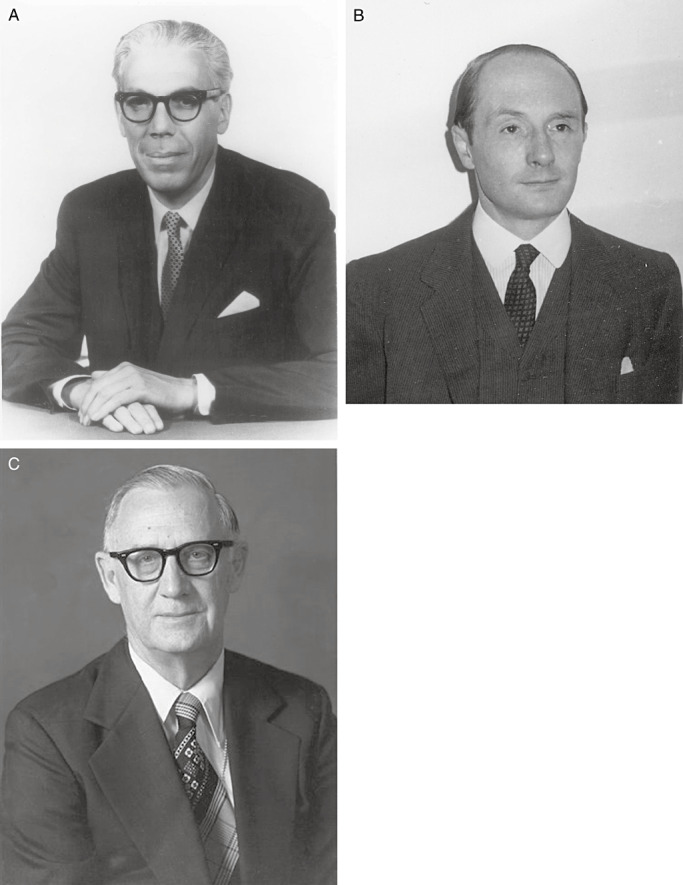

Figure 2.

(A) Drs Lucien J. Rubinstein (1924–1990), (B) Robin O. Barnard (1932–2005) and (C) Kenneth Earle (1919–1996) were among the participants who formulated the first World Health Organization classification of central nervous system tumors.

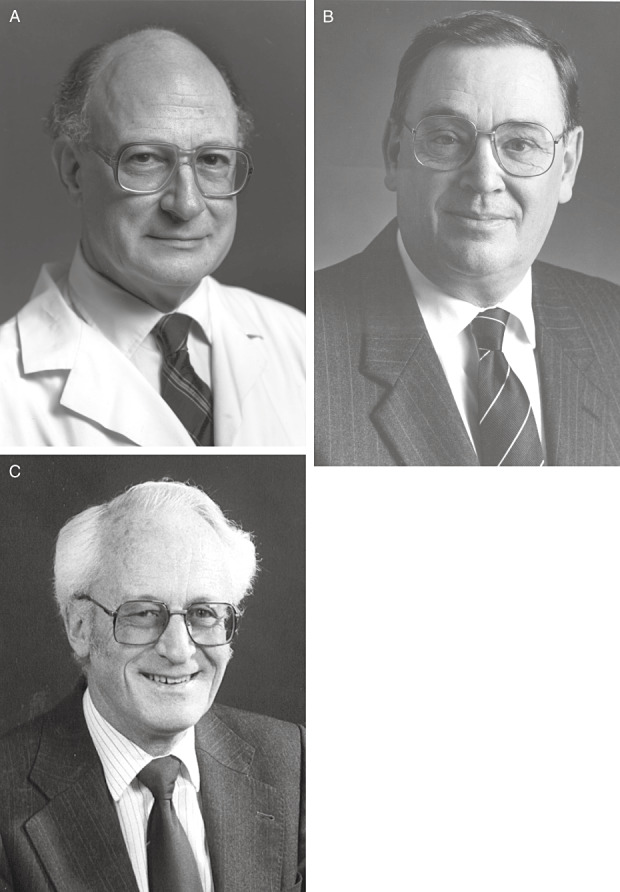

Figure 3.

(A) Drs John J. Kepes, (B) David Robertson and (C) J. Hume Adams were among the 10 100‐case reviewers who correlated their diagnoses with the proposed World Health Organization classification.

Figure 4.

The first World Health Organization Working Group including invited guests in Cologne, Germany, 1976. In the front row (left to right) are Drs K. J. Zülch (Federal Republic of Germany), K. M. Earle (USA), L. H. Sobin (USA) and A. P. Avtsyn (USSR). In the back row (left to right) are Drs B. Horton (guest; USA), R. Fankhauser (Switzerland), H.‐D. Mennel (guest; Federal Republic of Germany), E. Wildi (guest; Switzerland), J.‐M. Brucher (Belgium), L. J. Rubinstein (USA), Y. Ishida (Japan), A. Kunicki (Poland), J. E. Olvera Raviela (Mexico), T. Rabinowicz (Switzerland), R. O. Barnard (England) and J. Szymas (guest; Poland).

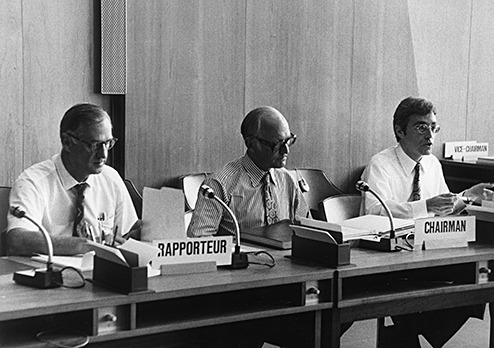

Figure 5.

The co‐chair, Dr Kenneth M. Earle (left), chairman, Dr Klaus J. Zülch (center) and secretariat Dr Leslie H. Sobin (right) at the first 1974 World Health Organization Working Group Meeting in Cologne, Germany.

Representing the German‐speaking and Anglo‐American schools were the two principle players, Drs Zülch and Rubinstein. Always gracious, they reveled in controversy, apparently without hostility. Although their opinions often diverged, it largely fell to them to formulate lesion definitions. The very approaches of the two men differed, in part because of their professional emphasis. Although both were neuropathologists and excellent, critical observers, Dr Zülch was also a practicing neuro‐oncologist deeply interested in grading, therapeutic implications and prognosis. Dr Rubinstein's focus was purely upon pathology, particularly mechanisms underlying cellular differentiation. As a result of these differences, a number of contentious issues surfaced. These centered upon both the nature of a number of lesions and upon the issue of tumor grading (see below). Of the former, a few deserve mention. One involved the so‐called “monstrocellular sarcoma,” (Figure 6A) a lesion considered mesenchymal and of blood vessel origin by Dr Zülch. In contrast, Dr Rubinstein considered it a giant cell variant of glioblastoma, a view subsequently confirmed by immunohistochemistry that demonstrated glial fibrillary acidic protein reactivity. The unhappy compromise consisted of double inclusion of the lesion, both in section V under “Tumours of Blood Vessel Origin,” and under “Glioblastoma” in section I, subsection F, entitled “Poorly Differentiated and Embryonal Tumours.” The placement of Glioblastoma in the scheme was also a contentious issue. Dr Zülch felt it belonged among “Poorly Differentiated and Embryonal Tumours,” whereas Dr Rubinstein considered it glial, although not exclusively astrocytic in nature. All said and done, it was placed into the former category. Another point of departure was the so‐called “circumscribed cerebellar sarcoma,” a lesion considered mesenchymal by Dr Zülch and a form of medulloblastoma by Dr Rubinstein (Figure 6B). Coupled with a historical footnote, it found its place under “Medulloblastoma” as the desmoplastic variant. Yet another point of departure centered upon the so‐called “pinealoma,” (Figure 6C) one variant of which Dr Zülch considered a lesion sui generis. In contrast Dr Rubinstein considered it a germ cell tumor (germinoma), as had his mentor Dr Russell. The issue was resolved in favor of its inclusion under “Germ Cell Tumours.” All these issues aside, the final result of their efforts was said to have left key participants “reasonably unhappy.” A classification replete with precise definitions and nomenclature did emerge, having been ratified by the group. The product was the first international “blue book,” the 21st in the series of WHO publications (Figure 7). It was not intended as a textbook, but as a concise, illustrated, nosologic standard. An overview of the work, in addition to some commentary regarding variations in concept among working group members, is summarized in a 1980 article by Dr Zülch, the sole editor of the first edition (19). Overview commentaries also followed 7, 11 and occasionally preceded (4) the publication of subsequent, much expanded editions.

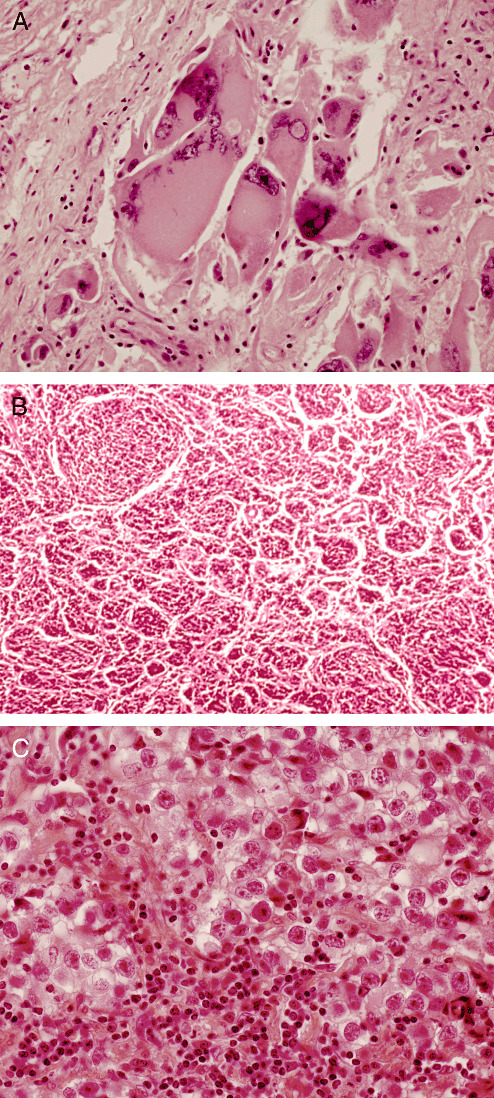

Figure 6.

Three lesions at the center of controversy at the meetings of the first World Health Organization Working Group included the (A) giant cell glioblastoma (“monstrocellular” sarcoma), (B) desmoplastic medulloblastoma (“circumscribed cerebellar sarcoma”) and (C) germinoma (“pinealoma”). Illustrations are from originally circulated cases examined by the reviewers (courtesy of Dr David Robertson, Kingston, Ontario, Canada and Dr Glen Sanberg, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC).

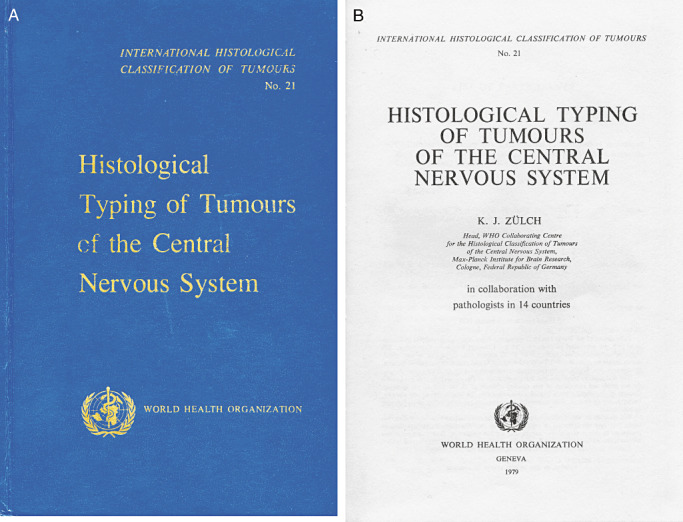

Figure 7.

The first edition (1979) of the World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. The distinctive color of this series (A) lent the designation “blue books” to the entire series, a term still loosely applied to subsequent editions. (B) Title page.

THE ISSUE OF GRADING

Aside from the difficulties inherent in formulating a classification and general definitions, arriving at prognostically meaningful “grades” also proved to be a challenge. In the end, both clinical and histologic malignancy was taken into consideration.

Here again, the two principal players differed in philosophy. Dr Zülch considered grading to be essential for therapeutic and prognostic purposes. On the other hand, Dr Rubinstein, fully aware of the relative aggressiveness of the various tumors within a given histologic category, saw numerical grading with its inherent inaccuracies as an imprecise activity and thus of limited utility. Indeed, grading of gliomas in particular is markedly affected by tissue sampling and the frustrating tendency of tumors to undergo progressive anaplasia over time. Dr Rubinstein acquiesced at the strong urging of Dr Earle. Viewed retrospectively, the issue may have been a “tempest in a teapot.” Verbal, if not numeric designations, were already in place. Their use was de facto grading.

The drive toward histologic grading was very much prompted by the concept of “clinical malignancy.” The incongruities between clinical and histologic grading schemes had already been addressed. As early as 1962, Dr Zülch had published his Proposed Five‐Grade Scale of Malignancy of Intracranial Tumors According to Intrinsic Growth Properties. Summarized in Table 1, the scheme grouped tumors of similar prognosis regardless of histology or cytologic considerations (15). A clinical malignancy score could be ascribed to any growing intracranial mass. Among lesions of grade 0 were extra‐parenchymal tumors growing purely by expansion and amenable to permanent surgical cure. Tumors of grade I were benign in nature but less reliably cured. Those of grades II through IV ranged from semi‐benign to highly malignant and were typically lethal, albeit associated with different survival times, they being 3–5 years, 1–3 years and 6 months to 1 year, respectively. Thus, this loose definition accommodated histologically benign and malignant tumors as well as lesions resulting in localized pressure upon vital centers, cerebrospinal fluid obstruction with secondary hydrocephalus, brain herniation and infiltrative growth with or without metastasis. Although these mechanisms of death were not closely correlated with histologic grade, the concept of clinical malignancy continues to affect our notions of WHO grade.

Table 1.

The Proposed Five‐Grade Scale of Malignancy of Intracranial Tumors According to Intrinsic Growth Properties[printed with permission from Zülch (15)].

| 0. Neurinomas, meningiomas, craniopharyngiomas, hypophyseal adenomas, epidermoids, dermoids, teratomas and lipomas. |

| I. Spongioblastomas, ependymomas of the ventricle, angioblastomas, plexus papillomas and temporobasal gangliocytomas. |

| II. Oligodendrogliomas, astrocytomas, other gangliocytomas and ependymomas of the cerebral hemispheres. |

| III. Pinealomas, malignant oligodendrogliomas, malignant astrocytomas, malignant gangliocytomas and malignant meningiomas. |

| IV. Medulloblastomas (including retinoblastomas), glioblastomas and primary sarcomas. |

This dual clinical/histologic malignancy approach continued to be incorporated into subsequent editions of the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. A three‐ or four‐tier numerical (WHO grades I–IV) scheme of histologic malignancy often paralleled verbal designations. This was most apparent in gliomas, particularly the spectrum of astrocytic, oligodendroglial and ependymal tumors, but was also applied to other tumor categories, such as meningiomas in which clear morphologic criteria of atypia (grade II) and malignancy (grade III) (12) eventually came to be formulated, albeit not without lively discussion. Prognosis, including recurrence and survival data, were thus played off against histology and its time‐proven parameters, including cellularity, atypia, mitoses, vascular proliferation and necrosis. Tumor staging according to the tumor–nodes–metastasis (TNM) approach was initially formulated by the UICC but was later abandoned because of its lack of relevance to CNS neoplasms. Tumor coding, as articulated in the Manual of Tumor Nomenclature and Coding by the American Cancer Society (1), subsequently became the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD‐O) published by the WHO (14).

SUBSEQUENT “BLUE BOOKS”

Understandably, given the popularity and international acceptance of the first WHO Classification, subsequent editions followed and were enthusiastically received. These were all under the auspices of the WHO (6) and some under the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as well 10, 13. In association with the International Society of Neuropathology a similar work was produced in 1997, one which, although not strictly a “blue book,” functioned as a template for later editions (8). Organization of all but the 2007 meeting fell to Dr Paul Kleihues (Figure 8). A student of Dr Zülch, he faithfully served the WHO and the IARC, all the while retaining his affiliation as Professor of Neuropathology, University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland. Coediting the 2000 edition and in part responsible for its first time inclusion of molecular genetics was Dr Webster K. Cavenee of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, University of California, San Diego, CA. The latest WHO was edited by Drs David N. Louis of the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Hiroko Ohgaki of the IARC in Lyon, Otmar D. Wiestler of the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg and Webster K. Cavenee (13). Compared with the 11 participants from the nine countries at the 1979 meeting, participants in subsequent 2‐ to 4‐day working meetings were far more numerous. The increase reflects expansion of the scope of the book, now no longer simply definitions and illustrations but a comprehensive text. Contributors to the blue book also increased in number, including 39 from 14 countries in 1993, 109 from 21 countries in 2000 and 74 from 19 countries in 2007. American representation was considerable, ranging from 35 to 46%. Also significantly represented were Germany, France, Finland, Switzerland, Japan and the United Kingdom. As in previous years, these well‐organized meetings witnessed energetic debate and the exchange of often strong opinions. Nonetheless, in each instance the product was a reflection of majority opinion. Compared with the original blue book, they differed in format (Figure 9), featuring comprehensive, highly organized text emphasizing the state of the art.

Figure 8.

Dr Paul Kleihues, organizer and coeditor of the second and third editions of the World Health Organization blue book.

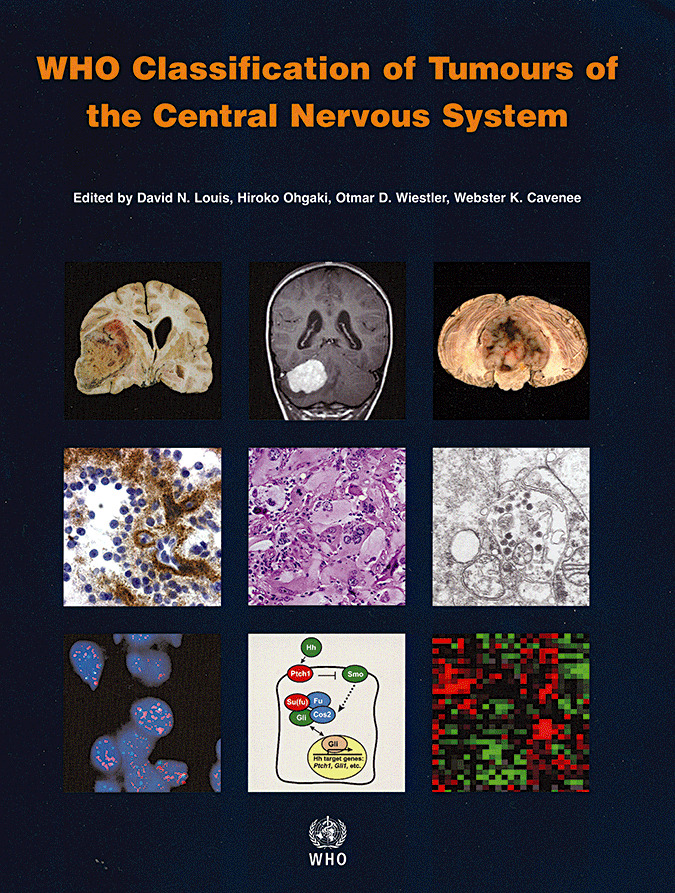

Figure 9.

The 2007 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. A highly illustrated, state‐of‐the‐art text replete with in‐depth treatment of molecular and genetic aspects of the lesions.

Table 2 summarizes the present 2007 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, replete with the accompanying ICD‐O and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine designations, italicized numbers representing provisional codes proposed for the 4th edition ICD‐0. Figure 10 lists the grade designations assigned to the complete tumor spectrum. The essential alterations in the WHO classification that took place over nearly 40 years are listed in Table 3. Much work remains in order to formulate an ideal classification. Only a continued emphasis upon clinicopathologic correlation supplemented by zealous research will result in further advances.

Table 2.

The 2007 WHO Classification of the Tumours of the Central Nervous System: a summary.

| Tumors of neuroepithelial tissue |

| Astrocytic tumors |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma 9421/11 |

| Pilomyxoid astrocytoma 9425/3* |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma 9384/1 |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma 9424/3 |

| Diffuse astrocytoma 9400/3 |

| Fibrillary astrocytoma 9420/3 |

| Gemistocytic astrocytoma 9411/3 |

| Protoplasmic astrocytoma 9410/3 |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma 9401/3 |

| Glioblastoma 9440/3 |

| Giant cell glioblastoma 9441/3 |

| Gliosarcoma 9442/3 |

| Gliomatosis cerebri 9381/3 |

| Oligodendroglial tumors |

| Oligodendroglioma 9450/3 |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma 9451/3 |

| Oligoastrocytic tumors |

| Oligoastrocytoma 9382/3 |

| Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma 9382/3 |

| Ependymal tumors |

| Subependymoma 9383/1 |

| Myxopapillary ependymoma 9394/1 |

| Ependymoma 9391/3 |

| Cellular 9391/3 |

| Papillary 9393/3 |

| Clear cell 9391/3 |

| Tanycytic 9391/3 |

| Anaplastic ependymoma 9392/3 |

| Choroid plexus tumors |

| Choroid plexus papilloma 9390/0 |

| Atypical choroid plexus papilloma 9390/1* |

| Choroid plexus carcinoma 9390/3 |

| Other neuroepithelial tumors |

| Astroblastoma 9430/3 |

| Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle 9444/1 |

| Angiocentric glioma 9431/1* |

| Neuronal and mixed neuronal‐glial tumors |

| Dysplastic gangliocytoma of cerebellum (Lhermitte–Duclos) 9493/0 |

| Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma 9412/1 |

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor 9413/0 |

| Gangliocytoma 9492/0 |

| Ganglioglioma 9505/1 |

| Anaplastic ganglioglioma 9505/3 |

| Central neurocytoma 9506/1 |

| Extraventricular neurocytoma 9506/1* |

| Cerebellar liponeurocytoma 9506/1* |

| Papillary glioneuronal tumor 9509/1* |

| Rosette‐forming glioneuronal tumor of the fourth ventricle 9509/1* |

| Paraganglioma 8680/1 |

| Tumors of the pineal region |

| Pineocytoma 9361/1 |

| Pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation 9362/3 |

| Pineoblastoma 9362/3 |

| Papillary tumor of the pineal region 9395/3* |

| Embryonal tumors |

| Medulloblastoma 9470/3 |

| Desmoplastic/nodular medulloblastoma 9471/3 |

| Medulloblastoma with extensive nodularity 9471/3* |

| Anaplastic medulloblastoma 9474/3* |

| Large cell medulloblastoma 9474/3 |

| Central nervous system (CNS) primitive neuroectodermal tumor 9473/3 |

| CNS Neuroblastoma 9500/3 |

| CNS Ganglioneuroblastoma 9490/3 |

| Medulloepithelioma 9501/3 |

| Ependymoblastoma 9392/3 |

| Atypical teratoid / rhabdoid tumor 9508/3 |

| Tumors of cranial and paraspinal nerves |

| Schwannoma (neurilemoma, neurinoma) 9560/0 |

| Cellular 9560/0 |

| Plexiform 9560/0 |

| Melanotic 9560/0 |

| Neurofibroma 9540/0 |

| Plexiform 9550/0 |

| Perineurioma |

| Perineurioma, NOS 9571/0 |

| Malignant perineurioma 9571/3 |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) |

| Epithelioid MPNST 9540/3 |

| MPNST with mesenchymal differentiation 9540/3 |

| Melanotic MPNST 9540/3 |

| MPNST with glandular differentiation 9540/3 |

| Tumors of the meninges |

| Tumors of meningothelial cells |

| Meningioma 9530/0 |

| Meningothelial 9531/0 |

| Fibrous (fibroblastic) 9532/0 |

| Transitional (mixed) 9537/0 |

| Psammomatous 9533/0 |

| Angiomatous 9534/0 |

| Microcystic 9530/0 |

| Secretory 9530/0 |

| Lymphoplasmacyte‐rich 9530/0 |

| Metaplastic 9530/0 |

| Chordoid 9538/1 |

| Clear cell 9538/1 |

| Atypical 9539/1 |

| Papillary 9538/3 |

| Rhabdoid 9538/3 |

| Anaplastic (malignant) 9530/3 |

| Mesenchymal tumors |

| Lipoma 8850/0 |

| Angiolipoma 8861/0 |

| Hibernoma 8880/0 |

| Liposarcoma 8850/3 |

| Solitary fibrous tumor 8815/0 |

| Fibrosarcoma 8810/3 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma 8830/3 |

| Leiomyoma 8890/0 |

| Leiomyosarcoma 8890/3 |

| Rhabdomyoma 8900/0 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma 8900/3 |

| Chondroma 9220/0 |

| Chondrosarcoma 9220/3 |

| Osteoma 9180/0 |

| Osteosarcoma 9180/3 |

| Osteochondroma 9210/0 |

| Haemangioma 9120/0 |

| Epithelioid haemangioendothelioma 9133/1 |

| Haemangiopericytoma 9150/1 |

| Anaplastic haemangiopericytoma 9150/3 |

| Angiosarcoma 9120/3 |

| Kaposi sarcoma 9140/3 |

| Ewing sarcoma ‐ PNET 9364/3 |

| Primary melanocytic lesions |

| Diffuse melanocytosis 8728/0 |

| Melanocytoma 8728/1 |

| Malignant melanoma 8720/3 |

| Meningeal melanomatosis 8728/3 |

| Other neoplasms related to the meninges |

| Haemangioblastoma 9161/1 |

| Lymphomas and haematopoietic neoplasms |

| Malignant lymphomas 9590/3 |

| Plasmacytoma 9731/3 |

| Granulocytic sarcoma 9930/3 |

| Germ cell tumors |

| Germinoma 9064/3 |

| Embryonal carcinoma 9070/3 |

| Yolk sac tumor 9071/3 |

| Choriocarcinoma 9100/3 |

| Teratoma 9080/1 |

| Mature 9080/0 |

| Immature 9080/3 |

| Teratoma with malignant transformation 9084/3 |

| Mixed germ cell tumor 9085/3 |

| Tumors of the sellar region |

| Craniopharyngioma 9350/1 |

| Adamantinomatous 9351/1 |

| Papillary 9352/1 |

| Granular cell tumor 9582/0 |

| Pituicytoma 9432/1* |

| Spindle cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis 8291/0* |

| Metastatic tumors |

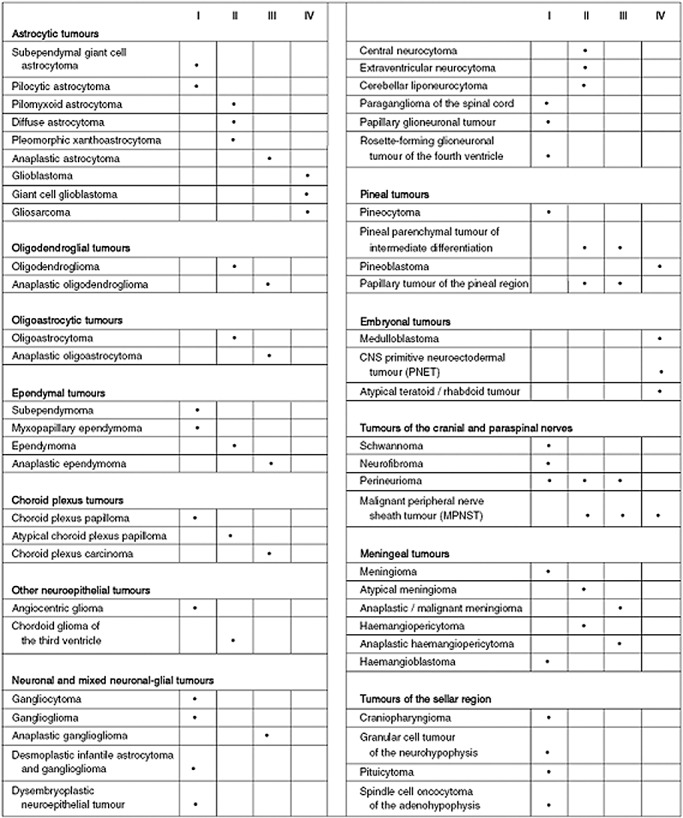

Figure 10.

The World Health Organization grades of central nervous system tumors according to the 2007 Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System.

Table 3.

A summary of changes from the 1979 baseline through the 1993, 2000 and 2007 editions.

| Astrocytic tumors |

| 1979 |

| • The category includes astrocytoma and anaplastic astrocytoma (but not glioblastoma), astroblastoma, pilocytic astrocytoma and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. |

| Note—Glioblastoma is defined as “An anaplastic, highly cellular tumor consisting of fusiform cells, small, poorly differentiated round cells or pleomorphic cells alone or in varying combinations. Necrosis, pseudopalisading, fistulous vessels and vascular endothelial proliferation, hemorrhage and invasive growth and usually prominent features.” |

| “Some typical glioblastomas show no evidence of a more differentiated tumor, whereas others are predominantly glioblastomas with focal areas of recognizable astrocytoma, less commonly oligodendroglioma, or exceptionally, ependymoma. Any of these gliomas may, in fact, terminate as a glioblastoma.” |

| • Giant cell glioblastoma was considered both a glioblastoma variant and an entity among Tumours of Blood Vessel Origin (“monstrocellular sarcoma”). |

| 1993 |

| • Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma added. |

| • Glioblastoma removed from “Poorly Differentiated and Embryonal Tumours” and included in the spectrum of “Astrocytic Tumours.” |

| • Astroblastoma moved to “Tumours of Uncertain Histogenesis.” |

| • The four parameters of the Ste. Anne Mayo method of classifying infiltrative astrocytic tumors into grades II‐IV are adopted by the World Health Organization; these include nuclear abnormalities, mitotic activity, endothelial proliferation and necrosis not limited to the pseudopalisading variety. |

| 2000 |

| • No substantial changes. |

| 2007 |

| • Pilomyxoid astrocytoma added as a subset of pilocytic astrocytoma. |

| • Glioneuronal tumor with neuropil‐like islands included in anaplastic astrocytoma category. |

| Oligoastrocytomas and mixed gliomas |

| 1979 |

| • Variants include oligodendroglioma and mixed oligo‐astrocytoma, as well as anaplastic oligodendroglioma. |

| 1993 |

| • Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma recognized. |

| 2000 |

| • No substantial change. |

| 2007 |

| • High‐grade oligo‐astrocytic tumors with necrosis are included under the pattern designation “glioblastoma with oligodendroglial component.” |

| Ependymomas |

| 1979 |

| • Variants include myxopapillary and papillary ependymoma as well as subependymoma. |

| 1993 |

| • Clear cell variant added. |

| 2000 |

| • Tanycytic variant added. |

| 2007 |

| • No substantial change. |

| Pineal tumors |

| 1979 |

| • Variants include pineocytoma and pineoblastoma. |

| 1993 |

| • Mixed/transitional pineal tumors added. |

| 2000 |

| • Mixed/transitional category deleted. |

| • Pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation added. |

| 2007 |

| • Consideration given to splitting pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation into low (grade II) and high (grade III) forms. |

| • Papillary tumor of the pineal region added. |

| Choroid plexus tumors |

| 1979 |

| • Variants include choroid plexus papilloma and anaplastic choroid plexus papilloma. |

| 1993 |

| • No substantial change. |

| 2000 |

| • No substantial change. |

| 2007 |

| • Atypical choroid plexus papilloma added. |

| Neuroepithelial tumors of uncertain origin (glial tumors of uncertain origin) |

| 1993 |

| • Polar spongioblastoma and gliomatosis cerebri moved to this category from “Poorly Differentiated and Embryonal Tumours category.” |

| • Astroblastoma moved to this category from “Astrocytic Tumours.” |

| 2000 |

| • Chordoid glioma added. |

| • Polar spongioblastoma deleted. |

| 2007 |

| • Angiocentric glioma added. |

| Neuronal (mixed neuronal‐glial) tumors |

| 1979 |

| • Variants include gangliocytoma and ganglioglioma, anaplastic gangliocytoma and ganglioglioma, neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma. |

| 1993 |

| • Dysplastic gangliocytoma of cerebellum (Lhermitte–Duclos disease) added. |

| • Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma added. |

| • Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor added. |

| • Central neurocytoma added. |

| • Paraganglioma of filum terminale added. |

| • Olfactory neuroblastoma added. |

| • Neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma deleted and moved to “Embryonal Tumours” category. |

| 2000 |

| • Cerebellar liponeurocytoma added. |

| • Olfactory neuroblastoma and neuroblastoma of adrenal/sympathetic nervous system moved to new category “Neuroblastic Tumours.” |

| 2007 |

| • Extraventricular neurocytoma added. |

| • Papillary glioneuronal tumor added. |

| • Rosette‐forming glioneuronal tumor added. |

| Poorly differentiated and embryonal tumors (embryonal tumors) |

| 1979 |

| • Category includes glioblastoma, gliosarcoma, giant cell glioblastoma (considered synonymous with “monstrocellular sarcoma”) and gliomatosis. Category also includes medulloblastoma and its desmoplastic and medullomyoblastic variants, as well as medulloepithelioma and primitive polar spongioblastoma. |

| 1993 |

| • Central nervous system neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma added. |

| Note—Olfactory neuroblastoma as well as neuroblastic tumors of the adrenal gland and sympathetic nervous system entered into the classification under a new category of “Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumours.” |

| • Ependymoblastoma added. |

| • Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) added as a category for medulloblastoma‐like tumors outside the cerebellum. |

| • Melanotic medulloblastoma added as a medulloblastoma variant. |

| 2000 |

| • Desmoplastic and large cell medulloblastoma variants added. |

| • Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor added. |

| 2007 |

| • Extensively nodular and anaplastic variants added to “Medulloblastoma” category. |

| • PNET category expanded to include not only small cell‐containing tumors including ependymoblastoma, but medulloepithelioma, a patently epithelial phenotype, as well. |

| Meningiomas |

| 1979 |

| • Category includes meningotheliomatous, fibrous, transitional, psammomatous, angiomatous, hemangioblastic, hemangiopericytic, papillary and anaplastic meningioma. |

| 1993 |

| • Microcystic, secretory, clear cell, chordoid, lymphoplasmacytic and metaplastic meningioma added. |

| • Atypical meningioma introduced as a category, but not clearly defined. |

| • Hemangioblastic category deleted. |

| • Hemangiopericytoma moved to “Mesenchymal, Non‐Meningothelial Tumours” category. |

| 2000 |

| • Rhabdoid meningioma added. |

| • Atypical and anaplastic meningioma categories clearly defined in terms of histologic criteria. |

| 2007 |

| • No substantial change. |

| Tumors of nerve sheath cells (tumors of cranial and spinal nerves) |

| 1979 |

| • Category included schwannoma, anaplastic schwannoma, neurofibroma and anaplastic neurofibroma. |

| 1993 |

| • Cellular schwannoma added. |

| • Plexiform schwannoma added. |

| • Melanotic schwannoma added. |

| • Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST)with divergent differentiation added. |

| • Melanotic MPNST added. |

| 2000 |

| • Intraneural and soft tissue perineurioma added. |

| • Malignant melanotic schwannoma and its psammomatous variant added. |

| 2007 |

| • No substantial change. |

| Primary melanocytic tumors |

| 1979 |

| • Category included melanoma and meningeal melanomatosis. |

| 1993 |

| • Diffuse melanosis added. |

| • Melanocytoma added. |

| 2000 |

| • No substantial change. |

| 2007 |

| • No substantial change. |

| Tumors of the anterior pituitary (tumors of the sellar region) |

| 1979 |

| • Category included pituitary adenoma and pituitary adenocarcinoma. |

| 1993 |

| • Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma added. |

| • Papillary craniopharyngioma added. |

| 2000 |

| • Granular cell tumor added. |

| 2007 |

| • Pituicytoma added. |

| • Spindle cell oncocytoma added. |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank Dr Leslie H. Sobin of the AFIP, Washington, DC; Dr Paul Kleihues, University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland; Dr Hans‐Dieter Mennel, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany; Dr John J. Kepes, Emeritus, University of Kansas, Kansas City, KS; Dr Christos D. Katsetos of St. Christopher's Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, PA; Dr Bruce Horton, Genzyme Genetics, New York, NY; and Dr Mary M. Herman, Section of Neuropathology, NIMH/NIH, The Intramural Research Program, Bethesda, MD, for their reminisces and critical suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Cancer Society (1968) Mannual Tumor Nomenclature and Coding. American Cancer Society: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anonymous (1952) Expert Committee on Health Statistics. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 53:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Union Against Cancer (UICC). Committee on Tumor Nomenclature (1965) Illustrated Tumor Nomenclature, p. 229. Springer: Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kepes JJ (1991) Review of the World Health Organization's newly proposed classification of brain tumors. Proc of the XIth International Congress of Neuropathology, Kyoto. Neuropathology 4:87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kernohan JW, Sayre GP (1952) Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW (1993) Histological Typing of Tumours of the Central Nevous System, 2nd edn. Springer‐Verlag: Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW (1993) The new WHO classification of brain tumours. Brain Pathol 3:255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (1997) Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous System. Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (eds), p. 255. IARC Press: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (2000) Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of the Nervous System. IARC Press: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (2000) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours—Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of the Nervous System. IARC Press: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kleihues P, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, Rorke LB, Reifenberger G, Burger PC, Cavenee WK (2002) The WHO classification of tumors of the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61(3):215–225, discussion 26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, Budka H, Von Deimling A, Kepes JJ (2000) Meningiomas. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Pathology and Genetics Tumours of the Nervous System. Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (eds), pp. 176–184. IARC Press: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (2007) WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Percy C, Fritz A, Jack A, Shanmugarathan S, Sobin L, Parkin DM, Whelan S (2000) International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD‐O), 3rd edn. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zulch KJ (1965) Brain Tumors: Their Biology and Pathology, 2nd edn. Springer Publishing Co. Inc.: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zulch KJ (1971) Atlas of the Histology of Brain Tumors. Springer: Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zulch KJ (1975) Atlas of Gross Neurosurgical Pathology. Springer: Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zulch KJ (1979) Histological Typing of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zulch KJ (1980) Principles of the new World Health Organization (WHO) classification of brain tumors. Neuroradiology 19(2):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]