Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by pathological lesions, in particular senile plaques (SPs), cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), predominantly consisting of self‐aggregated proteins amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau, respectively. Transglutaminases (TGs) are inducible enzymes, capable of modifying conformational and/or structural properties of proteins by inducing molecular covalent cross‐links. Both Aβ and tau are substrates for TG cross‐linking activity, which links TGs to the aggregation process of both proteins in AD brain. The aim of this study was to investigate the association of transglutaminase 1 (TG1), transglutaminase 2 (TG2) and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links with the pathological lesions of AD using immunohistochemistry. We observed immunoreactivity for TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in NFTs. In addition, both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links colocalized with Aβ in SPs. Furthermore, both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links were associated with CAA. We conclude that these TGs demonstrate cross‐linking activity in AD lesions, which suggests that both TG1 and TG2 are likely involved in the protein aggregation processes underlying the formation of SPs, CAA and/or NFTs in AD brain.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, transglutaminase, cross‐links, senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by pathological lesions such as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), senile plaques (SPs) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) (39). NFTs largely consist of aggregated hyperphosphorylated tau protein (28), whereas the major component of SPs and CAA is aggregated amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide (18). Conformational changes of both Aβ (47) and tau (17) may lead to their aggregation. In addition, both tau and Aβ are particularly neurotoxic when they are in such an aggregated state (12, 40, 41).

The transglutaminase (TG) protein family consists of nine members, among which are transglutaminase 1 (TG1), also known as keratinocyte transglutaminase, and transglutaminase 2 (TG2), or tissue transglutaminase. TG1 is essential for keratinocyte differentiation in the epidermis (13), whereas TG2 plays an important role during development, cell differentiation and apoptosis (15). TGs are calcium‐dependent enzymes that catalyze several reactions, such as the formation of (γ‐glutamyl)polyamine bonds (19), the deamidation of protein substrates (31, 48) and the formation of molecular cross‐links. TGs induce such cross‐links by catalyzing an acyl transfer reaction between the γ‐carboxamide group of a polypeptide‐bound glutamine and the ε‐amino group of a polypeptide‐bound lysine residue to form a covalent ε‐(γ‐glutamyl)lysine isopeptide bond. TG‐catalyzed cross‐links can be induced between either a lysine donor residue of one molecule with an acceptor glutamine residue of another molecule (intermolecular bridge), or a lysine donor and a glutamine acceptor present within a single molecule (intramolecular bridge) (30).

Although the aggregation cascades of the self‐aggregating proteins in AD have been studied intensively, it is largely unknown what initiates these processes. Somehow, the self‐interacting capacity of these proteins needs to be triggered to initiate the cascade, eventually leading to neurotoxic aggregates. Metal ions are known to initiate the aggregation cascade and induce Aβ (3, 23) aggregation in vitro. In addition, various proteins that interact with Aβ are also able to initiate and facilitate the aggregation process, such as apolipoprotein E (43, 44, 51), heat‐shock proteins (16, 32, 52, 53, 55) and complement factors (49, 50), whereas tau fibrillization can be triggered by, for instance, glycosaminoglycans (22). In addition to these factors, TG‐catalyzed cross‐linking of proteins, such as Aβ and tau, might play a role in the initiation of the aggregation process through the induction of protein polymers or via conformational and/or structural changes in these proteins. So far, only TG2 is known to affect the aggregation of both Aβ and tau in vitro via cross‐linking (10, 11). Aβ was found to be good a substrate for TG2 cross‐linking, leading to the formation of Aβ oligomers (11). In addition, both phosphorylated tau, which accumulates in NFTs, as well as nonphosphorylated tau have been shown to be excellent substrates for TG2 cross‐linking (10, 11). Presently, however, no information is available about the association of either tau or Aβ with other types of TGs, including TG1.

In the healthy human brain, both TG1 and TG2 are observed in neurons of several brain areas such as the amygdala, corpus callosum, cerebellum and frontal cortex (26). In the cortex of AD brains, both TG1 and TG2 levels, as well as TG cross‐linking activity, are elevated, compared with control patients (24). Although in a single study TG2 immunoreactivity has been observed in amyloid plaque cores in AD (58), so far no evidence for TG‐catalyzed cross‐linking activity has been demonstrated in these lesions. In contrast to SPs, both TG2 (42) and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links are observed in NFTs in AD brain (9). However, the association of TG2 with CAA and of TG1 with AD lesions in general remains to be elucidated. Therefore, to obtain additional information about the possible involvement of TGs and TG‐catalyzed cross‐linking in AD pathology, we investigated the presence of TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in both control brain and in the classic pathological lesions of AD brain using a panel of well‐characterized antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Brain tissue

Temporal neocortex tissue samples from 10 AD patients (age 71.3 ± 9.2 yearss; post‐mortem delay 6.1 ± 1.8 h), five AD patients with CAA and five control subjects without neurological disease (age 71 ± 21 yearss; post‐mortem delay 6.6 ± 0.5 h), was obtained after rapid autopsy and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen (The Netherlands Brain Bank, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The diagnosis of AD was based on a combination of neuropathological and clinical criteria (35). Table 1 provides an overview of the diagnosis, Braak & Braak score, CAA grading, age, post‐mortem interval and gender of the patients used in this study. CAA grading was established by quantification of the number of Aβ‐positive vessels in one microscopic field (magnification 2.5×), as described in a previous report (54). At least 4 microscopic fields of temporal neocortex were analyzed and categorized as follows: 0 (–, no CAA), 0–10 (+, sparse CAA), 10–20 (++, moderate CAA) and >20 (+++, severe CAA) vessels affected by Aβ deposition.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics. Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; F = female; M = male; PMI = post‐mortem interval (h = hours); ND = not determined.

| Patient number | Diagnosis | Gender | Age | PMI(h) | Grade (Braak, NFT) | Grade (Braak, Aβ) | Grade CAA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | M | 90 | 6 | 1 | B/C | − |

| 2 | Control | F | 61 | 7 | 0 | O | − |

| 3 | Control | M | 96 | 7 | 1 | O | − |

| 4 | Control | M | 50 | 7 | ND | ND | − |

| 5 | Control | M | 57 | 6 | 1 | O | − |

| 6 | AD | F | 66 | ND | 6 | C | − |

| 7 | AD | F | 68 | 4 | 6 | C | − |

| 8 | AD | M | 87 | 6 | 5 | C | − |

| 9 | AD | F | 84 | 7 | 5 | C | − |

| 10 | AD | M | 82 | 10 | 4 | C | − |

| 11 | AD/CAA | F | 75 | 6 | 5 | C | +++ |

| 12 | AD/CAA | F | 91 | 7 | 5 | C | ++ |

| 13 | AD/CAA | M | 75 | 5 | 4 | C | ++ |

| 14 | AD/CAA | F | 70 | 4 | 6 | C | +++ |

| 15 | AD/CAA | M | 65 | 6 | 6 | B | ++ |

Grading of AD (Braak) and of CAA was performed as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial coronal sections (6 µm) of temporal neocortex were fixed with acetone (100%) or methanol (100%) for 10 minutes and pre‐incubated with 20% animal serum, the type of which was determined by the specific secondary antibody used. Primary antibody was diluted in PBS‐Tween (0.05%) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Rabbit anti‐Aβ (Ab10148, 1:400 dilution) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Mouse anti‐guinea pig liver purified TG2 (Ab‐2, 1:500 dilution) was purchased from Lab Vision (Los Angeles, CA, USA), and the mouse anti‐human TG2 (4G3, 1:50 dilution), directed against the fibronectin‐binding domain of TG2 (1‐165), was a generous gift from Professor A. Belkin (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA) (2). Ab‐2 was used to determine the presence of TG2 in human brain vessels, since it intensely stained TG2 in endothelial cells. Goat anti‐human TG1 (Sc‐18129, 1:100 dilution), C‐terminal part, was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse anti‐H‐Glu(H‐Lys‐OH)‐OH (81D4, 1:1000 dilution) was obtained from Covalab (Villeurbanne, France). Mouse anti‐human hyperphorphorylated tau (AT8, 1:1000 dilution) was purchased from Thermoscientific (Rockford, IL, USA). Mouse anti‐human CD68 (KP1, 1:1000) and rabbit anti‐human GFAP (1:500 dilution) were purchased from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark). Secondary antibodies were all purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch; biotin‐labeled donkey anti‐goat (1:200), biotin‐labeled goat anti‐mouse (1:200) and biotin‐labeled goat anti‐rabbit (1:200). Immunohistochemistry was performed according to the avidin‐biotin‐peroxidase method. Reaction products were visualized with the Vectastain Elite Avidin Biotin kit according to manufacturer's protocol (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), using nickel‐enhanced 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation of the sections in 0.3% H2O2 with 0.1% sodium azide prior to immunolabeling. For each antibody, various concentrations were tested to determine the optimal immunoreactivity (ie, the highest intensity of specific labeling without significant background staining). Negative controls consisted of representative sections processed without the primary antibody. The specificity of the antibodies directed against TG1 and TG2 in human brains was demonstrated by preadsorption of anti‐TG1 antibody with recombinant human TG1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti‐TG2 antibody with recombinant human TG2 (Zedira Biotech, Darmstad, Germany). The specificity of the anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was demonstrated by preadsorption with H‐Glu(H‐Lys‐OH)‐OH (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) (20, 25). Congo red staining was performed as described in a previous report (54).

Double immunofluorescence

For double immunostaining, sections were treated as described above. Sections were incubated with serum of the specific second antibody used to reduce a specific fluorescence. Sections were simultaneously incubated with the primary antibodies of interest. Secondary antibodies used were biotin‐labeled donkey anti‐goat antibody coupled to Alexa594 (1:400, Molecular Probes, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and biotin‐labeled donkey anti‐rabbit antibody coupled to Alexa488 (1:400, Molecular Probes). Fluorescence was analyzed using a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Rijswijk, The Netherlands). To exclude false positive fluorescence signals for each channel, a series of images was obtained separately in both channels through a 63× glycerin lens (zoom factor 4×, Z‐increment 0.12 µm, approximately 100 images of 1024 × 1024 pixels).

Quantification of immunohistochemical stainings

Staining for the different anti‐TG or anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibodies was evaluated by an assessment of the staining of amyloid‐laden cortical vessels, diffuse and classic SPs, and NFTs in the temporal neocortex. For each AD patient, the number of TG1/TG2 or TG‐catalyzed cross‐link‐positive AD lesions in 8–13 microscopical fields (magnification 100×) per serial section were analyzed. The average percentage of TG1/TG2 or TG‐catalyzed cross‐link‐positive AD lesions was determined for all patients. Amyloid‐laden vessels and diffuse SPs were identified by anti‐Aβ staining, classic SPs by both anti‐Aβ and Congo red staining, and NFTs by tau staining.

RESULTS

Distribution of TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in neocortex of control brains

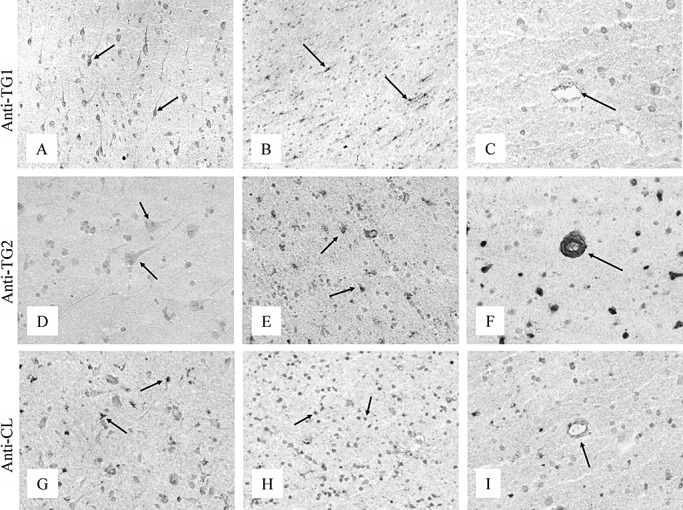

In control brain, TG1 staining was observed in the cytoplasm of neurons in the gray matter (Figure 1A), and in astrocytes and microglial cells in the white matter (Figure 1B) of the neocortex. No immunoreactivity of the anti‐TG1 antibody was observed in brain vessels (Figure 1C). TG2 staining was observed in the cytoplasm and nucleus of neurons in the neocortex (Figure 1D). TG2 was also observed in astrocytes in the white matter (Figure 1E), and in capillaries and other parenchymal vessels (Figure 1F). Staining of the anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was observed in astrocytes in both gray and white matter (Figure 1G). In addition, the anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was also observed in the nucleus of both glial cells and neurons (Figure 1H). The anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was weakly immunoreactive in vessels of the neocortex (Figure 1I). Presence of anti‐TG1, anti‐TG2 and anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody in astrocytes and microglia was confirmed by colocalization with a specific marker (GFAP and KP1, respectively; not shown). Spot blot analysis demonstrated no cross‐reaction of the anti‐TG1 antibody with either recombinant TG2 or H‐Glu(H‐Lys‐OH)‐OH. Similar results were obtained for the anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody with either recombinant TG1 or TG2, and for the anti‐TG2 antibody with either recombinant TG1 or H‐Glu(H‐Lys‐OH)‐OH (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of the neocortex of control brain for TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links. The anti‐TG1 antibody stained both neurons in the gray matter (A, arrow) and glial cells in the white matter (B, arrow). TG1 immunoreactivity was absent in vessels of the neocortex (C, arrow). TG2 was present in neurons in the gray matter (D, arrow) and in glial cells in the white matter (E, arrow). TG2 staining was observed in both capillaries and parenchymal vessels (F, arrow). The anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody (anti‐CL) was immunoreactive in astrocytes of both the white and the gray matter (G, arrow) and in the nucleus of glial cells and neurons of the neocortex (H, arrow). Weak immunoreactivity of the anti‐CL antibody was observed in parenchymal vessels (I, arrow). Original magnification: A, C, D, F, G, I×200; B, E, H×150. Abbreviations: TG = transglutaminase; TG1 = transglutaminase 1; TG2 = transglutaminase 2.

Colocalization of TG1 with the pathological lesions in AD brains

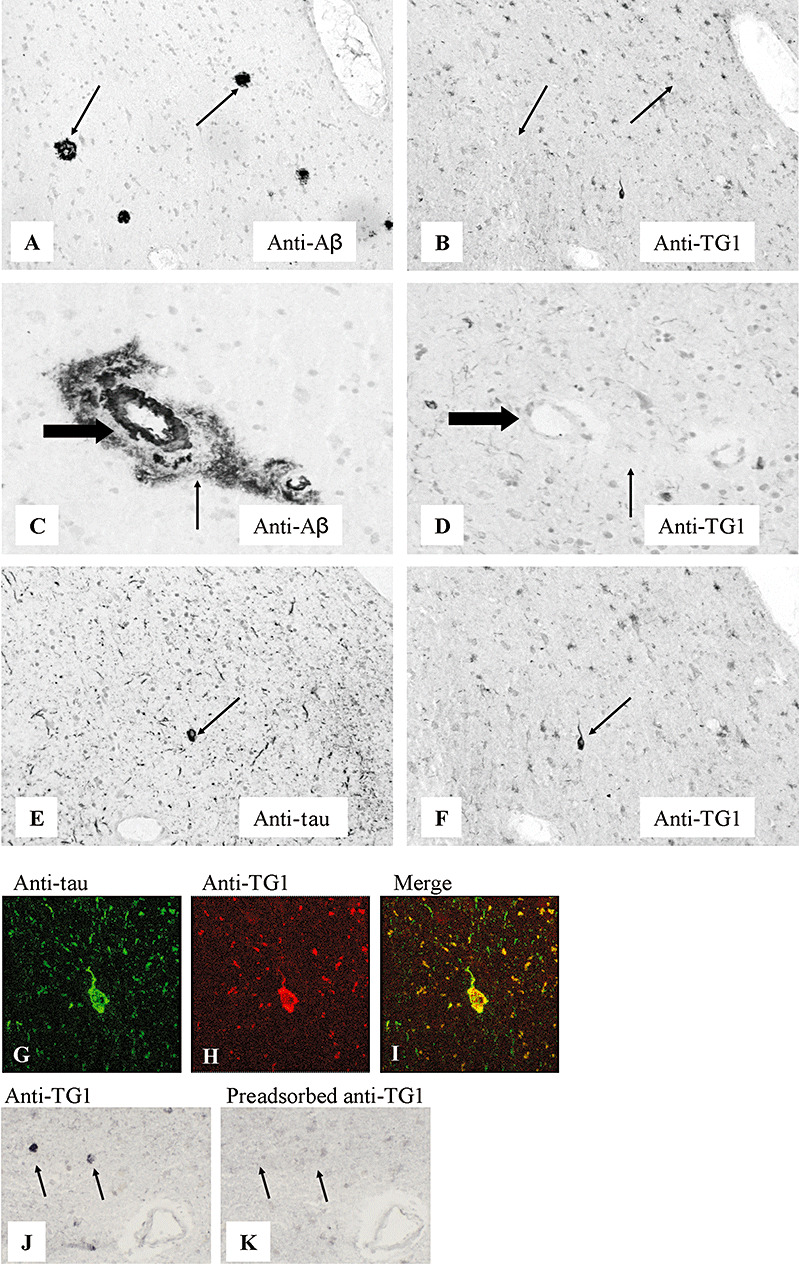

In AD brains, the general staining pattern of TG1 was similar to control brain. Although the anti‐TG1 antibody demonstrated no immunoreactivity in either classic (Figure 2A,B) or diffuse (Figure 2C,D) SPs, as well as in CAA (Figure 2C,D), strong TG1 staining was observed in all NFTs present (Figure 2E,F). Colocalization of TG1 staining with hyperphosphorylated tau in NFTs was demonstrated using double immunofluorescence (Figure 2G–I). Immunoreactivity of the anti‐TG1 antibody was also observed in the tau‐positive neuritic changes associated with SPs, although it was absent in pre‐tangles (not shown). Specificity of the anti‐TG1 immunoreactivity in human brains (Figure 2J) was demonstrated by the lack of anti‐TG1 immunoreactivity of NFTs following preadsorption of the antibody with human recombinant TG1 (Figure 2K).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining for TG1 of SPs, CAA and NFTs in the neocortex of Alzheimer's disease brain. Serial sections: A–B, C–D, E–F, J–K. The anti‐Aβ antibody stained both classic (A, arrow) and diffuse SPs (C, arrow), and CAA (C, large arrow). The anti‐TG1 antibody was absent in both classic (B, arrow) and diffuse (D, arrow) SPs, and in CAA (D, large arrow). The anti‐tau antibody‐stained NFTs (E, arrow). Anti‐TG1 immunoreactivity was demonstrated in NFTs (F, arrow). Double immunofluorescence staining demonstrated colocalization of TG1 with hyperphosphorylated tau in NFTs (G–I). Specificity of the anti‐TG1 antibody was demonstrated by preadsorption of the antibody with human recombinant TG1 (J,K). Staining of NFTs with anti‐TG1 (J) is absent after preadsorption (K). Original magnification: A–F, J, K×200; G–I×400. Abbreviations: TG1 = transglutaminase 1; SPs = senile plaques; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; NFTs = neurofibrillary tangles; Aβ = amyloid‐β.

Colocalization of TG2 with the pathological lesions in AD brains

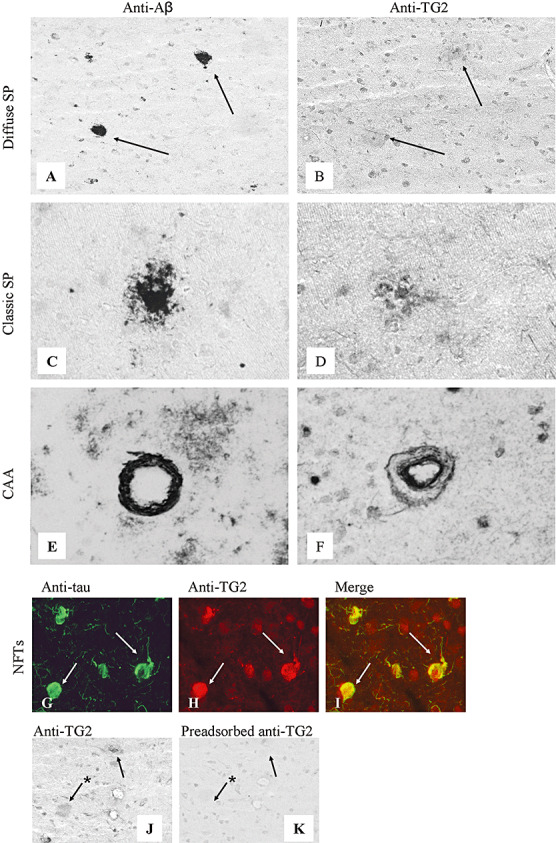

In general, the TG2 staining pattern in AD brain was similar to control brain. Additionally, weak TG2 staining was observed in approximately 92% (Table 2) of the diffuse SPs (Figure 3A,B), whereas immunoreactivity of the TG2 antibody was prominent in 93 ± 4% of the classic SPs (Figure 3C,D), as confirmed by Congo red staining (data not shown). In addition, TG2 staining was observed in approximately 97% (Table 2) of CAA‐affected vessels (Figure 3E,F). Interestingly, TG2 staining did not spatially colocalize with the deposited Aβ in CAA, but was observed in endothelial cells of CAA‐affected vessels and at the abluminal side of these vessels, suggestive of expression by perivascular cells (Figure 3E,F). Colocalization of TG2 staining with hyperphosphorylated tau in NFTs and tau‐positive neuritic changes associated with SPs was demonstrated using double immunofluorescence (Figure 3G–I), although it was absent in pre‐tangles. Approximately 94% of the observed NFTs demonstrated TG2 staining (Table 2). Specificity of anti‐TG2 immunoreactivity in human brains (Figure 3J) was demonstrated by the reduction of immunoreactivity after preadsorption with human recombinant TG2 (Figure 3K).

Table 2.

Summary of the percentage [mean (SD)] of NFTs, diffuse SPs, classic SPs or Aβ‐affected vessels that were stained for TG1, TG2 or TG‐catalyzed cross‐links. Abbreviations: NFTs = neurofibrillary tangles; SPs = senile plaques; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; SD = standard deviation; TG = transglutaminase; TG1 = transglutaminase 1; TG2 = transglutaminase 2.

| NFTs | Diffuse SPs | Classic SPs | CAA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG1 | 100 | — | — | — |

| TG2 | 93 (5) | 91 (8) | 93 (4) | 94 (4) |

| TG‐catalyzed cross‐links | 95 (4) | 96 (2) | 100 | 97 (3) |

The results are mean percentages of 8–13 microscopical fields per serial section of 10 Alzheimer's disease patients.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of SPs, CAA and NFTs in the neocortex of Alzheimer's disease brain for TG2. Serial sections: A–B, C–D, E–F, J–K. The anti‐Aβ antibody stained both diffuse (A, arrow) and classic SPs (C), and CAA (E). TG2 staining was present in both diffuse (B) and classic (D) SPs. TG2 was present in endothelial cells in CAA vessels and as a halo surrounding the deposited Aβ in CAA (F). Double immunofluorescence staining demonstrated colocalization of TG2 with hyperphosphorylated tau in NFTs (arrows, G–I). Specificity of the TG2 staining was demonstrated by preadsorption of the antibody with recombinant human TG2 (J,K). Staining of both classic (arrow) and diffuse (arrow with asterisk) SPs with anti‐TG2 (J) was strongly reduced after preadsorption (K). Original magnification: A, B, J, K×200; C–F×250; G–I×400. Abbreviations: TG2 = transglutaminase 2; SPs = senile plaques; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; NFTs = neurofibrillary tangles; Aβ = amyloid‐β.

Colocalization of TG‐catalyzed cross‐links with the pathological lesions in AD brains

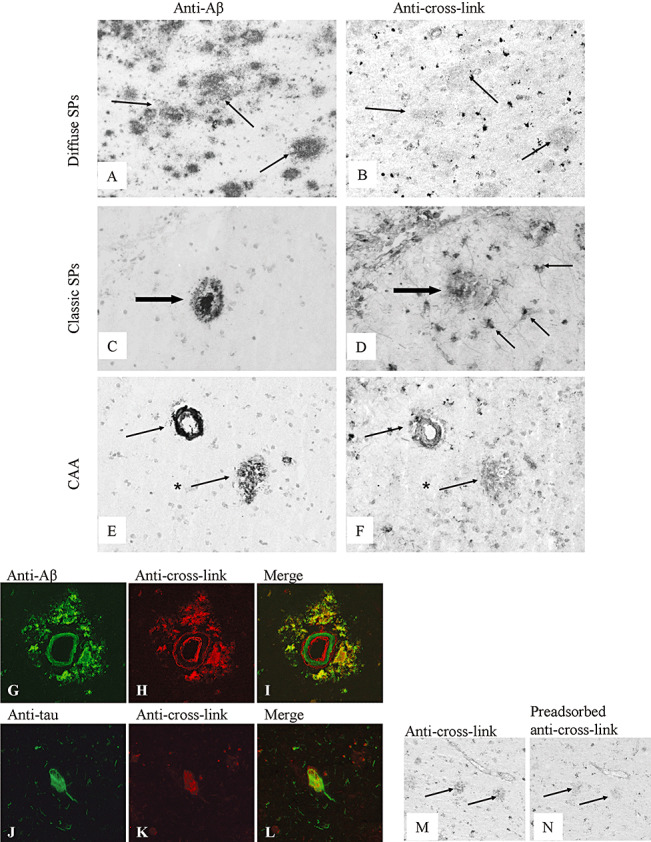

In general, the TG‐catalyzed cross‐link staining pattern in AD neocortex was similar to control brains. In addition, in approximately 96% of the diffuse (Figure 4A,B) and all classic (Figure 4C,D) SPs, TG‐catalyzed cross‐link staining was observed (Table 2). Moreover, immunoreactivity for TG‐catalyzed cross‐links was observed in reactive astrocytes associated with SPs (Figure 4D), confirmed by double immunofluorescence of TG‐catalyzed cross‐link immunoreactivity with GFAP (data not shown). In CAA, no colocalization of the TG‐catalyzed cross‐link staining with accumulated Aβ in the vessel wall was detected. However, double immunofluorescence analysis of CAA vessels demonstrated TG‐catalyzed cross‐link staining in endothelial cells, in contrast to control vessels (Figure 1I). Similar to TG2 staining in CAA‐affected vessels, an abluminal staining of the TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was also observed, suggestive for increased cross‐linking in perivascular cells (Figure 4G–I). TG‐catalyzed cross‐link staining colocalized with hyperphosporylated tau protein in NFTs (Figure 4J–L) and tau‐positive neuritic changes associated with SPs, although they were not observed in pre‐tangles. Approximately 95% of the observed NFTs demonstrated TG‐catalyzed cross‐link staining (Table 2). Specificity of the anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link reactivity in human brains was demonstrated by strongly reduced staining of anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody (Figure 4M) after preadsorption with H‐Glu(H‐Lys‐OH)‐OH (Figure 4N).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of SPs, CAA and NFTs in the neocortex of Alzheimer's disease brain for TG‐catalyzed cross‐links. The anti‐Aβ antibody stained both diffuse (A, arrow, and E, arrow with asterisk) and classic (C, arrow) SPs, and CAA (E, arrow). The anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was demonstrated in both diffuse (B, arrow, and F, arrow with asterisk) and classic (D, large arrow) SPs. In addition, TG‐catalyzed cross‐links were also observed in reactive astrocytes associated with classic SPs (D, arrow). The anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was demonstrated in CAA (F, arrow). Double immunofluorescence demonstrated TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in endothelial and possible perivascular cells in CAA and in deposited Aβ surrounding Aβ‐affected vessels (G–I). Double immunofluorescence also demonstrated TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in NFTs (J–L). Specificity of the anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibody was demonstrated by preadsorption of the antibody with H‐Glu(H‐Lys‐OH)‐OH (M,N). Staining of SPs with anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link (M) was strongly reduced after preadsorption (N). Original magnification: A–F, M–N×200; G–I×250; J–L×400. Abbreviations: TG = transglutaminase; SPs = senile plaques; CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; NFTs = neurofibrillary tangles; Aβ = amyloid‐β.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe for the first time a differential association of TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links with SPs, CAA and NFTs in AD brain and their expression in various cell types in control brain. In line with an earlier report, we observed expression of both TG1 and TG2 in neurons in human brain (26). Moreover, we also demonstrated the presence of TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in these neurons, and TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐link immunoreactivity in glial cells, in particular microglial cells and astrocytes. In AD brain, we demonstrated the colocalization of both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links with tau in NFTs, a phenomenon observed previously by others (9, 42). Additionally, we did not only observe TG2 in both classic and diffuse SPs, but also TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in these lesions, linking both presence and cross‐linking activity of TGs with classic AD. We also observed the association of both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links with CAA. Furthermore, apart from the presence of TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in NFTs, we showed specific colocalization of TG1 with tau in NFTs.

In our study, in AD brain, we did not only observe colocalization of TG2 with aggregated Aβ in SPs and tau in NFTs, but also the presence of TG‐catalyzed cross‐link immunoreactivity in these lesions. Together, these data suggest that TG2 is not only present in AD lesions but, because of its cross‐linking capability, might also play a role in the initiation and/or accumulation of proteins in these lesions. This assumption is strengthened by other reports demonstrating that both Aβ and tau are substrates for TG2‐catalyzed cross‐linking (10, 11), and that TG‐catalyzed cross‐linking of both Aβ and tau induces aggregate formation of both proteins in vitro (10, 11, 38). We observed strong immunoreactivity of both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibodies in classic SPs, and in particular in the amyloid core, as observed by Zhang et al (58). Moreover, we extend these findings by demonstrating the presence of these antibodies in diffuse SPs, although immunoreactivity of the anti‐TG2 and anti‐TG‐catalyzed cross‐link antibodies was less abundant compared with that in the amyloid core in classic SPs. As TG2 induces the aggregate formation of Aβ, and the amyloid core of classic SPs is characterized by mature Aβ fibrils (39), the abundant presence of both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in these cores might reflect the involvement of TG2 cross‐linking activity in the aggregate formation of Aβ in these lesions. Thus, these findings are in line with the assumption that the TG2 cross‐linking activity of Aβ induces aggregate formation. However, a recent study demonstrated that TG2 cross‐linking of self‐aggregating protein might also prevent the formation of protein aggregation (27), which suggests that higher levels of TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in the amyloid core might be the result of a failed attempt to prevent protein aggregation and accumulation.

Elevated mRNA levels of both TG1 and TG2 were observed previously in AD brain, although the cellular source of this elevation is unclear (24). Our data suggest that the elevation in TG1 and TG2 levels may be a result of the increasing numbers of activated microglial cells and reactive astrocytes in AD brains. However, it cannot be ruled out that this increase in TG1 and TG2 in AD, as reported before (24), might also be related to the presence of NFTs. Like Aβ, tau is also an excellent substrate for TG2‐catalyzed cross‐linking (34). Both phosphorylated tau, which accumulates in NFTs, as well as nonphosphorylated tau are substrates for TG2 (10). In fact, TG2‐mediated cross‐linking induces high‐molecular‐weight tau aggregates, and can even transform tau into straight and paired helical filaments (38). Furthermore, TG2 is able to polyaminate the tau protein, resulting in an increased resistance of tau to proteolytic degradation by proteases resulting in higher levels of nondegradable tau within neurons (45). In line with these in vitro data by others, we observed the presence of TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in NFTs, suggesting that TG2 cross‐links tau in vivo. Interestingly, we also observed the presence of TG1 in NFTs. TG1, or keratinocyte transglutaminase, contributes to maintain the toughened skin epidermis through cross‐linking activity (19). As the known primary function of TG1 is the cross‐linking of proteins (13), our data suggest that TG1, in addition to TG2, cross‐links tau in NFTs. However, as yet, it is unknown if tau is indeed a substrate for TG1. Staining of TG1, TG2 and their cross‐links were absent in pre‐tangles, which suggest that TGs have a higher affinity for more aggregated forms of tau. Taken together, these data indicate that increased levels of TG1 and TG2 in AD might be related to the presence of NFTs, or the increase in activated glial cells in AD. Furthermore, considering their mechanism of action, both TG1 and TG2 might have a regulatory function in the development of NFTs in AD.

Although both TG1 and TG2 have a similar general distribution pattern in the human brain, both are present in neurons and glial cells, their expression pattern in AD lesions seems to differ. TG1 is predominantly observed in intracellular protein aggregates, that is, NFTs. In contrast, TG2 is present not only intracellularly in NFTs, but also extracellularly in SPs. Our observations are in line with previous reports that describe TG1 as an intracellular membrane‐anchored protein (7), whereas TG2, besides the cytoplasm and cell membrane (8), is found extracellularly, associated with cell adhesion processes and spreading (1, 21). Moreover, both TG2 protein levels (5) and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links (37) are detectable in cerebrospinal fluid, and both are increased in AD. Therefore, it is most likely that the TG‐catalyzed cross‐links found in SPs are a result of extracellular TG2, instead of TG1. However, we cannot exclude TG‐catalyzed cross‐linking via TG1 in the extracellular space, as TG1 expression and action has been observed at cell–cell borders (4). In addition, although we found immunoreactivity for TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in reactive astrocytes associated with SPs, it is unclear if these astrocytes also secrete TG2. Thus, the cellular source of this extracellular TG2 in AD brain remains to be elucidated.

Surprisingly, in contrast to SPs, both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links did not colocalize with the deposited Aβ in CAA. Nevertheless, both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links were present in endothelial cells in CAA‐affected vessels and observed as a halo surrounding the deposited Aβ at the abluminal side, probably in perivascular cells (56). Although anti‐TG2 antibody immunoreactivity was also observed in control vessels without Aβ, increased immunoreactivity was found in the endothelial cells and perivascular cells, probably smooth muscle cells and/or brain pericytes, in CAA vessels. Different from SPs, which predominantly consist of the more amyloidogenic Aβ1–42, CAA mainly consists of Aβ1–40 (33). Our data therefore suggest that TG2 is more associated with Aβ1–42, compared with Aβ1–40. This would be in line with an earlier report demonstrating a higher affinity of TG2 for more amyloidogenic forms of Aβ (11), and explains the colocalization of TG2 with Aβ in SPs and its absence in CAA. Apart from differences in Aβ species that accumulate in SPs and CAA, both lesions also differ in accumulating proteins other than Aβ, and in inflammation reactions. SPs are characterized by inflammatory reactions, mediated by the presence of reactive astrocytes and microglia, and the activation of the complement system (57). In CAA, this reaction is restricted to activation of the complement system (46). Inflammatory proteins, such as α1‐antichymotrypsin, α2‐macroglobulin and intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 that are associated with SPs, are absent in CAA (46). In addition, other proteins, such as heparan sulphate proteoglycans and small heat‐shock proteins are differentially observed in SPs and CAA (55). Thus, apart from the difference in Aβ species, the lack of a full inflammatory reaction in CAA, or the nonappearance of certain proteins, might be responsible for the absence in colocalization of TGs and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links with the deposited Aβ in CAA. However, the presence of Aβ in CAA‐affected vessels seems to trigger the expression of TG2 in endothelial and perivascular cells and increases TG2 cross‐linking activity in these cells. Yet, at present, it is unclear if and how this increased presence of both TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐link in these cells contributes to the pathogenesis of CAA.

In this study, we observed association of TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed with the classical AD lesions, yet we cannot exclude the possibility that the presence of TGs and/or TG‐catalyzed cross‐links in the classic AD lesions, in general, is not a result of both Aβ and tau, but of the presence of other TG substrates, such as heat‐shock proteins, C1‐inhibitor or receptor‐associated protein (14), also present in these lesions (55). If this is the case, the absence of the described TG substrates in a small percentage of the classic AD lesions might explain why TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links were not found in all AD lesions analyzed (Table 2). Yet, we cannot exclude that other differences in these AD lesions, in particular the specific development stage, might lead to the absence of TG1/TG2 and TG‐catalyzed staining. For instance, no staining of TG1, TG2 and TG‐catalyzed cross‐links were observed in pre‐tangles, whereas they were present in NFTs. Although the exact implications of our data in the disease process requires further elucidation, the results of the present study demonstrate a clear association of the presence and enzymatic activity of two major transglutaminases, that is, TG1 and TG2, with the classical pathological lesions of AD. Considering their important role in extracellular matrix stabilization, cell‐matrix interaction, cellular differentiation, cell death and their implications in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases, these multifunctional enzymes may therefore provide a novel therapeutic target (6, 29, 36, 57) to counteract the pathological hallmarks underlying neurodegeneration in AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank The Netherlands Brain Bank for supplying the human brain tissue, and Dr. W. Kamphorst for the neuropathological diagnosis of control and AD tissue. This work was supported by a grant from the “Hersenstichting Nederland” (number 2008(1).36, to MMMW).

REFERENCES

- 1. Aeschlimann D, Thomazy V (2000) Protein crosslinking in assembly and remodelling of extracellular matrices: the role of transglutaminases. Connect Tissue Res 41:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akimov SS, Belkin AM (2001) Cell surface tissue transglutaminase is involved in adhesion and migration of monocytic cells on fibronectin. Blood 98:1567–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atwood CS, Moir RD, Huang X, Scarpa RC, Bacarra NM, Romano DM et al (1998) Dramatic aggregation of Alzheimer abeta by Cu(II) is induced by conditions representing physiological acidosis. J Biol Chem 273:12817–12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baumgartner W, Weth A (2007) Transglutaminase 1 stabilizes beta‐actin in endothelial cells correlating with a stabilization of intercellular junctions. J Vasc Res 3:234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonelli RM, Aschoff A, Niederwieser G, Heuberger C, Jirikowski G (2002) Cerebrospinal fluid tissue transglutaminase as a biochemical marker for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis 11:106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breve JJ, Drukarch B, Van Strien M, Van Dam AM (2008) Validated sandwich ELISA for the quantification of tissue transglutaminase in tissue homogenates and cell lysates of multiple species. J Immunol Methods 332:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chakravarty R, Rong XH, Rice RH (1990) Phorbol ester‐stimulated phosphorylation of keratinocyte transglutaminase in the membrane anchorage region. Biochem J 271:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen JS, Mehta K (1999) Tissue transglutaminase: an enzyme with a split personality. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 31:817–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Citron BA, Suo Z, SantaCruz K, Davies PJ, Qin F, Festoff BW (2002) Protein crosslinking, tissue transglutaminase, alternative splicing and neurodegeneration. Neurochem Int 40:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dudek SM, Johnson GV (1993) Transglutaminase catalyzes the formation of sodium dodecyl sulfate‐insoluble, Alz‐50‐reactive polymers of tau. J Neurochem 61:1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dudek SM, Johnson GV (1994) Transglutaminase facilitates the formation of polymers of the beta‐amyloid peptide. Brain Res 651:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duff K, Planel E (2005) Untangling memory deficits. Nat Med 11:826–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eckert RL, Sturniolo MT, Broome AM, Ruse M, Rorke EA (2005) Transglutaminase function in epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 124:481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esposito C, Caputo I (2005) Mammalian transglutaminases: identification of substrates as a key to physiological function and physiopathological relevance. FEBS J 272:615–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fesus L (1993) Biochemical events in naturally occurring forms of cell death. FEBS Lett 328:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fonte V, Kapulkin V, Taft A, Fluet A, Friedman D, Link CD (2002) Interaction of intracellular beta amyloid peptide with chaperone proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:9439–9444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gamblin TC, Berry RW, Binder LI (2003) Modeling tau polymerization in vitro: a review and synthesis. Biochemistry 42:15009–15017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glenner GG, Wong CW (1984) Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 120:885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greenberg CS, Birckbichler PJ, Rice RH (1991) Transglutaminases: multifunctional cross‐linking enzymes that stabilize tissues. FASEB J 5:3071–3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halverson RA, Lewis J, Frausto S, Hutton M, Muma NA (2005) Tau protein is cross‐linked by transglutaminase in P301L tau transgenic mice. J Neurosci 25:1226–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haroon ZA, Hettasch JM, Lai TS, Dewhirst MW, Greenberg CS (1999) Tissue transglutaminase is expressed, active, and directly involved in rat dermal wound healing and angiogenesis. FASEB J 13:1787–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hasegawa M, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Goedert M (1997) Alzheimer‐like changes in microtubule‐associated protein Tau induced by sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Inhibition of microtubule binding, stimulation of phosphorylation, and filament assembly depend on the degree of sulfation. J Biol Chem 272:33118–33124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang X, Atwood CS, Moir RD, Hartshorn MA, Vonsattel JP, Tanzi RE, Bush AI (1997) Zinc‐induced Alzheimer's Abeta1‐40 aggregation is mediated by conformational factors. J Biol Chem 272:26464–26470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson GV, Cox TM, Lockhart JP, Zinnerman MD, Miller ML, Powers RE (1997) Transglutaminase activity is increased in Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain Res 751:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson TS, El‐Koraie AF, Skill NJ, Baddour NM, El Nahas AM, Njloma M et al (2003) Tissue transglutaminase and the progression of human renal scarring. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:2052–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim SY, Grant P, Lee JH, Pant HC, Steinert PM (1999) Differential expression of multiple transglutaminases in human brain. Increased expression and cross‐linking by transglutaminases 1 and 2 in Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem 274:30715–30721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Konno T, Morii T, Hirata A, Sato S, Oiki S, Ikura K (2005) Covalent blocking of fibril formation and aggregation of intracellular amyloidgenic proteins by transglutaminase‐catalyzed intramolecular cross‐linking. Biochemistry 44:2072–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee VM, Balin BJ, Otvos L Jr, Trojanowski JQ (1991) A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal Tau. Science 251:675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lesort M, Tucholski J, Miller ML, Johnson GV (2000) Tissue transglutaminase: a possible role in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Neurobiol 61:439–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lorand L, Conrad SM (1984) Transglutaminases. Mol Cell Biochem 58:9–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lorand L, Graham RM (2003) Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:140–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Magrane J, Smith RC, Walsh K, Querfurth HW (2004) Heat shock protein 70 participates in the neuroprotective response to intracellularly expressed beta‐amyloid in neurons. J Neurosci 24:1700–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCarron MO, Nicoll JA, Stewart J, Cole GM, Yang F, Ironside JW et al (2000) Amyloid beta‐protein length and cerebral amyloid angiopathy‐related haemorrhage. Neuroreport 11:937–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miller ML, Johnson GV (1995) Transglutaminase cross‐linking of the tau protein. J Neurochem 65:1760–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM et al (1991) The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 41:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muma NA (2007) Transglutaminase is linked to neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 66:258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nemes Z, Fesus L, Egerhazi A, Keszthelyi A, Degrell IM (2001) N(epsilon)(gamma‐glutamyl)lysine in cerebrospinal fluid marks Alzheimer type and vascular dementia. Neurobiol Aging 22: 403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Norlund MA, Lee JM, Zainelli GM, Muma NA (1999) Elevated transglutaminase‐induced bonds in PHF tau in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 851:154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Selkoe DJ (1991) The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 6:487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Selkoe DJ (1997) Alzheimer's disease: genotypes, phenotypes, and treatments. Science 275:630–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Selkoe DJ (2000) The origins of Alzheimer disease: a is for amyloid. JAMA 283:1615–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singer SM, Zainelli GM, Norlund MA, Lee JM, Muma NA (2002) Transglutaminase bonds in neurofibrillary tangles and paired helical filament tau early in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Int 40:17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak‐Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD (1993) Apolipoprotein E: high‐avidity binding to beta‐amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late‐onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:1977–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Strittmatter WJ, Weisgraber KH, Huang DY, Dong LM, Salvesen GS, Pericak‐Vance M et al (1993) Binding of human apolipoprotein E to synthetic amyloid beta peptide: isoform‐specific effects and implications for late‐onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:8098–8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tucholski J, Kuret J, Johnson GV (1999) Tau is modified by tissue transglutaminase in situ: possible functional and metabolic effects of polyamination. J Neurochem 73:1871–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Verbeek MM, Eikelenboom P, De Waal RM (1997) Differences between the pathogenesis of senile plaques and congophilic angiopathy in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:751–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Walsh DM, Hartley DM, Kusumoto Y, Fezoui Y, Condron MM, Lomakin A et al (1999) Amyloid beta‐protein fibrillogenesis. Structure and biological activity of protofibrillar intermediates. J Biol Chem 274:25945–25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Walther DJ, Peter JU, Winter S, Holtje M, Paulmann N, Grohmann M et al (2003) Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet alpha‐granule release. Cell 115:851–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Webster S, Bonnell B, Rogers J (1997) Charge‐based binding of complement component C1q to the Alzheimer amyloid beta‐peptide. Am J Pathol 150:1531–1536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Webster S, Bradt B, Rogers J, Cooper N (1997) Aggregation state‐dependent activation of the classical complement pathway by the amyloid beta peptide. J Neurochem 69:388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilhelmus MM, Otte‐Holler I, Davis J, Van Nostrand WE, De Waal RM, Verbeek MM (2005) Apolipoprotein E genotype regulates amyloid‐beta cytotoxicity. J Neurosci 25:3621–3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wilhelmus MM, Boelens WC, Otte‐Holler I, Kamps B, De Waal RM, Verbeek MM (2006) Small heat shock proteins inhibit amyloid‐beta protein aggregation and cerebrovascular amyloid‐beta protein toxicity. Brain Res 1089:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wilhelmus MM, Boelens WC, Otte‐Holler I, Kamps B, Kusters B, Maat‐Schieman ML et al (2006) Small heat shock protein HspB8: its distribution in Alzheimer's disease brains and its inhibition of amyloid‐beta protein aggregation and cerebrovascular amyloid‐beta toxicity. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 111:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wilhelmus MM, Otte‐Holler I, Wesseling P, De Waal RM, Boelens WC, Verbeek MM (2006) Specific association of small heat shock proteins with the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease brains. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 32:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilhelmus MM, De Waal RM, Verbeek MM (2007) Heat shock proteins and amateur chaperones in amyloid‐Beta accumulation and clearance in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol 35:203–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wilhelmus MM, Otte‐Holler I, Van Triel JJ, Veerhuis R, Maat‐Schieman ML, Bu G et al (2007) Lipoprotein receptor‐related protein‐1 mediates amyloid‐beta‐mediated cell death of cerebrovascular cells. Am J Pathol 171:1989–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wilhelmus MM, Van Dam AM, Drukarch B (2008) Tissue transglutaminase: a novel pharmacological target in preventing toxic protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. Eur J Pharmacol 585:464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang W, Johnson BR, Suri DE, Martinez J, Bjornsson TD (1998) Immunohistochemical demonstration of tissue transglutaminase in amyloid plaques. Acta Neuropathol 96:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]