Abstract

Background

Antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) is associated with rule‐breaking, criminality, substance use, unemployment, relationship difficulties, and premature death. Certain types of medication (drugs) may help people with AsPD. This review updates a previous Cochrane review, published in 2010.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and adverse effects of pharmacological interventions for adults with AsPD.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 13 other databases and two trials registers up to 5 September 2019. We also checked reference lists and contacted study authors to identify studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in which adults (age 18 years and over) with a diagnosis of AsPD or dissocial personality disorder were allocated to a pharmacological intervention or placebo control condition.

Data collection and analysis

Four authors independently selected studies and extracted data. We assessed risk of bias and created 'Summary of findings tables' and assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE framework. The primary outcomes were: aggression; reconviction; global state/global functioning; social functioning; and adverse events.

Main results

We included 11 studies (three new to this update), involving 416 participants with AsPD. Most studies (10/11) were conducted in North America. Seven studies were conducted exclusively in an outpatient setting, one in an inpatient setting, and one in prison; two studies used multiple settings. The average age of participants ranged from 28.6 years to 45.1 years (overall mean age 39.6 years). Participants were predominantly (90%) male. Study duration ranged from 6 to 24 weeks, with no follow‐up period. Data were available from only four studies involving 274 participants with AsPD. All the available data came from unreplicated, single reports, and did not allow independent statistical analysis to be conducted. Many review findings were limited to descriptive summaries based on analyses carried out and reported by the trial investigators.

No study set out to recruit participants on the basis of having AsPD; many participants presented primarily with substance abuse problems. The studies reported on four primary outcomes and six secondary outcomes. Primary outcomes were aggression (six studies) global/state functioning (three studies), social functioning (one study), and adverse events (seven studies). Secondary outcomes were leaving the study early (eight studies), substance misuse (five studies), employment status (one study), impulsivity (one study), anger (three studies), and mental state (three studies). No study reported data on the primary outcome of reconviction or the secondary outcomes of quality of life, engagement with services, satisfaction with treatment, housing/accommodation status, economic outcomes or prison/service outcomes.

Eleven different drugs were compared with placebo, but data for AsPD participants were only available for five comparisons. Three classes of drug were represented: antiepileptic; antidepressant; and dopamine agonist (anti‐Parkinsonian) drugs. We considered selection bias to be unclear in 8/11 studies, attrition bias to be high in 7/11 studies, and performance bias to be low in 7/11 studies. Using GRADE, we rated the certainty of evidence for each outcome in this review as very low, meaning that we have very little confidence in the effect estimates reported.

Phenytoin (antiepileptic) versus placebo

One study (60 participants) reported very low‐certainty evidence that phenytoin (300 mg/day), compared to placebo, may reduce the mean frequency of aggressive acts per week (phenytoin mean = 0.33, no standard deviation (SD) reported; placebo mean = 0.51, no SD reported) in male prisoners with aggression (skewed data) at endpoint (six weeks). The same study (60 participants) reported no evidence of difference between phenytoin and placebo in the number of participants reporting the adverse event of nausea during week one (odds ratio (OR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 16.76; very low‐certainty evidence). The study authors also reported that no important side effects were detectable via blood cell counts or liver enzyme tests (very low‐certainty evidence).

The study did not measure reconviction, global/state functioning or social functioning.

Desipramine (antidepressant) versus placebo

One study (29 participants) reported no evidence of a difference between desipramine (250 to 300 mg/day) and placebo on mean social functioning scores (desipramine = 0.19; placebo = 0.21), assessed with the family‐social domain of the Addiction Severity Index (scores range from zero to one, with higher values indicating worse social functioning), at endpoint (12 weeks) (very low‐certainty evidence).

Neither of the studies included in this comparison measured the other primary outcomes: aggression; reconviction; global/state functioning; or adverse events.

Nortriptyline (antidepressant) versus placebo

One study (20 participants) reported no evidence of a difference between nortriptyline (25 to 75 mg/day) and placebo on mean global state/functioning scores (nortriptyline = 0.3; placebo = 0.7), assessed with the Symptom Check List‐90 (SCL‐90) Global Severity Index (GSI; mean of subscale scores, ranging from zero to four, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms), at endpoint (six months) in men with alcohol dependency (very low‐certainty evidence).

The study measured side effects but did not report data on adverse events for the AsPD subgroup.

The study did not measure aggression, reconviction or social functioning.

Bromocriptine (dopamine agonist) versus placebo

One study (18 participants) reported no evidence of difference between bromocriptine (15 mg/day) and placebo on mean global state/functioning scores (bromocriptine = 0.4; placebo = 0.7), measured with the GSI of the SCL‐90 at endpoint (six months) (very low‐certainty evidence).

The study did not provide data on adverse effects, but reported that 12 patients randomised to the bromocriptine group experienced severe side effects, five of whom dropped out of the study in the first two days due to nausea and severe flu‐like symptoms (very low‐certainty evidence).

The study did not measure aggression, reconviction and social functioning.

Amantadine (dopamine agonist) versus placebo

The study in this comparison did not measure any of the primary outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence summarised in this review is insufficient to draw any conclusion about the use of pharmacological interventions in the treatment of antisocial personality disorder. The evidence comes from single, unreplicated studies of mostly older medications. The studies also have methodological issues that severely limit the confidence we can draw from their results. Future studies should recruit participants on the basis of having AsPD, and use relevant outcome measures, including reconviction.

Plain language summary

The use of medication to treat people with antisocial personality disorder

Background

People with antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) may behave in a way that is harmful to themselves or others, and is against the law. They can be dishonest and act aggressively without thinking. Many misuse drugs and alcohol. Certain types of medication (drugs) may help people with AsPD. This review updates one published in 2010.

Review question

What are the beneficial and harmful effects of medication on aggression, reconviction (reoffending), and people's ability to function in society?

Study characteristics

We searched for relevant studies up to 5 September 2019 and found 11 randomised controlled trials (RCT); a type of study in which people were allocated at random (by chance alone) to have either a medication (drug) or a placebo (dummy tablet).

The studies included 416 AsPD participants, mostly male (90%), with an average age of 39.6 years. Most studies (10/11) were carried out in North America in outpatient clinics (seven studies). Two studies were conducted in mixed settings and one apiece in an inpatient hospital or prison. Studies lasted between six and 24 weeks, and had no follow‐up period. Data were only available from four of the 11 included studies for 274 participants with AsPD.

Some studies reported on important outcomes in AsPD: aggression (six studies), global state/functioning (three studies), social functioning (one study) and adverse effects (seven studies). Some reported on other outcomes: leaving the study early (eight studies), substance misuse (five studies), employment status (one study), impulsivity (one study), anger (three studies), and mental state (three studies). No study reported data on reconviction, quality of life, engagement with services, satisfaction with treatment, housing/accommodation status, economic or prison/service outcomes.

No study set out to recruit participants on the basis of having AsPD. Many participants presented primarily with substance abuse problems. The studies used methods that increased the risk of data being biased or untrue (e.g. not reporting all of their outcomes) and that did not allow independent statistics to be calculated for this review.

The studies assessed 11 medications but comparison data for AsPD participants were available for only three different types of medication and placebo: antiepileptics (drugs to treat epilepsy); antidepressants (drugs to treat depression); and dopamine agonists (drugs to treat Parkinson's disease).

Main results

Phenytoin (antiepileptic) versus placebo

One study (60 participants) found very low‐certainty evidence that, compared to placebo, phenytoin may reduce the average frequency of aggressive acts per week in aggressive male prisoners with AsPD at six weeks. The number of participants reporting sickness during week one did not differ across groups, and no side effects were detectable by blood tests. We are very uncertain about these findings.

Desipramine (antidepressant) versus placebo

One study (29 participants) found no evidence of a difference in social functioning scores at 12 weeks, between a drug used to treat depression (desipramine) and placebo. We are very uncertain about these findings.

Nortriptyline (antidepressant) versus placebo

One study (20 participants) found no evidence of a difference in global state/functioning scores in men with alcohol dependency at six months, between a different antidepressant (nortriptyline) and placebo. We are very uncertain about these findings.

Bromocriptine (dopamine agonist) versus placebo

One study (18 participants) found no evidence of a difference in global state/functioning scores at six months, between a drug used to treat Parkinson's disease (bromocriptine) and placebo. Twelve participants randomised to the bromocriptine group experienced side effects, five of whom dropped out due to sickness and flu‐like symptoms in the first two days. We are very uncertain about these findings.

Amantadine (dopamine agonist) versus placebo

None of the included studies assessed the effectiveness of another treatment for Parkinson's disease (amantadine) for any of the primary outcomes.

Conclusions

The certainty of the evidence is very low, meaning that we are not confident in the findings. There is not enough evidence to determine whether or not medication is a helpful treatment for people with AsPD.

Further research is required to clarify which medications, if any, are effective for treating the main features of AsPD. Future studies should recruit participants on the basis of having AsPD, and include reconviction as an outcome measure.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) is one of the 10 specific personality disorder categories in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐5). The DSM‐5 defines personality disorder as "an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual's culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment" (p 645). The general criteria for personality disorder according to DSM‐5 are given in Table 7.

1. DSM‐5 general criteria for personality disorder.

| Criteria | Description (taken from DSM‐5, p 646‐7) |

| A. | An enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture. This pattern is manifested in two (or more) of the following areas:

|

| B. | The enduring pattern is inflexible and pervasive across a broad range of personal and social situations. |

| C. | The enduring pattern leads to clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. |

| D. | The pattern is stable and of long duration, and its onset can be traced back at least to adolescence or early adulthood. |

| E. | The enduring pattern is not better explained as a manifestation or consequence of another mental disorder. |

| F. | The enduring pattern is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of abuse, a medication) or a another medical condition (e.g. head trauma). |

AsPD is described in the DSM‐5 as “a pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others” (p 645). According to the DSM‐5, in order to be diagnosed with AsPD (301.7), a person must fulfil both the general criteria for personality disorder outlined above and also the specific criteria for AsPD (criteria A, B, C and D, as shown in Table 8). DSM‐5 also states, in reference to the traits of AsPD, that “this pattern has also been referred to as psychopathy, sociopathy or dyssocial personality disorder” (p 659). There continues, however, to be debate about the status of psychopathy compared to AsPD (for example, see Ogloff 2006), how it is measured and the degree to which it is subject to change, which is beyond the scope of this review.

2. DSM‐5 diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder ‐ (301.7).

| Criteria | Description (taken from DSM‐5, p 659) |

| A. | A pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, occurring since age 15 years, as indicated by three (or more) of the following: 1. Failure to conform to social norms with respect to lawful behaviors, as indicated by repeatedly performing acts that are grounds for arrest. 2. Deceitfulness, as indicated by repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for personal profit or pleasure. 3. Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead. 4. Irritability and aggressiveness, as indicated by repeated physical fights or assaults. 5. Reckless disregard for safety of self or others. 6. Consistent irresponsibility, as indicated by repeated failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor financial obligations. 7. Lack of remorse, as indicated by being indifferent to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from another. |

| B. | The individual is at least 18 years. |

| C. | There is evidence of conduct disorder with onset before age of 15 years. |

| D. | The occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. |

The International Classification of Diseases ‐ 10th Edition (ICD‐10) classifies this condition as dissocial personality disorder (F60.2). AsPD and dissocial personality disorder are often used interchangeably by clinicians and they describe a very similar presentation. While there is considerable overlap between these two diagnostic systems, they differ in two respects. First, the DSM‐5 requires that those meeting the diagnostic criteria also show evidence of conduct disorder with onset before the age of 15 years, whereas there is no such requirement using ICD‐10 criteria when making the diagnosis of dissocial personality disorder. However, a study comparing participants meeting the full criteria for AsPD (which the DSM‐5 has retained) with those who otherwise fulfilled criteria for AsPD, but who did not demonstrate evidence of childhood conduct disorder, did not find any clinically important differences (Perdikouri 2007). Second, dissocial personality disorder focuses more on interpersonal deficits (for example, incapacity to experience guilt, a very low tolerance of frustration, proneness to blame others) and less on antisocial behaviour. Table 9 shows the ICD‐10 diagnostic criteria to diagnose dissocial personality disorder (F60.2).

3. ICD‐10 diagnostic criteria for dissocial personality disorder ‐ (F60.2).

| Description (taken fromICD‐10) |

| Personality disorder, usually coming to attention because of gross disparity between behaviour and the prevailing social norms, and characterized by: a. callous unconcern for the feelings of others; b. gross and persistent attitude of irresponsibility and disregard for social norms, rules and obligations; c. incapacity to maintain enduring relationships, though having no difficulty in establishing them; d. very low tolerance to frustration and a low threshold for discharge of aggression, including violence; e. incapacity to experience guilt or to profit from experience, particularly punishment; and f. marked proneness to blame others, or to offer plausible rationalizations for the behaviour that has brought the patient into conflict with society. There may also be persistent irritability as an associated feature. Conduct disorder during childhood and adolescents, though not invariably present, may further support the diagnosis. |

It is acknowledged that the classification and diagnosis of personality disorder is an area of controversy and complexity with ongoing debate about the usefulness of multiple categories of personality disorder versus a dimensional approach (Tyrer 2015, Skodol 2018). Others feel the very label of personality disorder to be pejorative and unhelpful (Johnstone 2018). Indeed, a major paradigm shift in the conceptualisation of personality disorder has been suggested in the latest iteration of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐11). The proposed ICD‐11 model takes a dimensional approach and is made up of three components: a general severity rating, five maladaptive personality trait domains, and a borderline pattern qualifier (Oltmanns 2019). The proposed classification changes to personality disorder, however, are outside the scope of this review, which is focused on interventions for AsPD, as defined in the current, predominant classification systems of DSM‐5 and ICD‐10.

Most studies report the prevalence of AsPD to be between 2% and 3% in the general population (Moran 1999; Coid 2006; NICE 2010). A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries found a prevalence rate for AsPD of 3% (Volkert 2018). Prevalence rates are considerably higher in men compared with women (Dolan 2009; NICE 2015) and a 3:1 ratio of men to women has been described (Compton 2005). It has also been suggested that there are sex differences in how this condition may present, with women with AsPD being less likely than men with AsPD to present with violent antisocial behaviour (Alegria 2013). AsPD (and other personality disorder diagnoses) may be less likely to be diagnosed in non‐white populations (McGilloway 2010).

As would be expected, AsPD is especially common in prison settings. In the UK prison population, the prevalence of people with AsPD has been identified as 63% in male remand prisoners, 49% in male sentenced prisoners and 31% in female prisoners (Singleton 1998). A systematic review of mental disorders in prisoners examined 62 studies from 12 countries and reported the prevalence of AsPD in male prisoners to be 47%, with prisoners approximately 10 times more likely to have AsPD than the general population (Fazel 2002).

The condition is associated with a wide range of disturbance, including greatly increased rates of criminality, substance use, unemployment, homelessness and relationship difficulties (Martens 2000), as well as negative long‐term outcome. Many adults with AsPD are imprisoned at some point in their life. Although follow‐up studies have demonstrated some improvement over the longer term, particularly in rates of re‐offending (Weissman 1993; Grilo 1998; Martens 2000), men with AsPD who reduce their offending behaviour over time may nonetheless continue to have major problems in their interpersonal relationships (Paris 2003). Black 1996 found that men with AsPD who were younger than 40 years of age had a strikingly high rate of premature death, and obtained a value of 33 for the standardized mortality rate (the age‐adjusted ratio of observed deaths to expected deaths), meaning that they were 33 times more likely to die than males of the same age without this condition. This increased mortality was linked not only to an increased rate of suicide but also to reckless behaviours such as drug misuse and aggression. A 27‐year follow‐up study also found AsPD to be a strong predictor of all cause mortality (Krasnova 2019). Black 2015 noted that earlier age of onset has been linked to poorer long‐term outcomes, although marriage, employment, early incarceration and degree of socialization may act as moderating factors. Follow‐up studies in forensic psychiatric settings suggest a similarly concerning picture. For example, Davies 2007 reported that 20 years after discharge from a medium‐secure unit almost half of the patients were reconvicted, with reconviction rates higher in those with personality disorder compared to those with mental illness (such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder). Similarly, Coid 2015 examined reconviction after discharge from seven medium‐secure units in England and Wales and found that patients with personality disorder were more than two and a half times more likely than those with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder to violently offend after discharge.

Significant comorbidity exists between AsPD and many other mental health conditions; mood and anxiety disorders are common (Goodwin 2003; Black 2010; Galbraith 2014). The presence of personality disorder co‐occurring with another mental health condition may have a negative impact on the outcome of the latter (Newton‐Howes 2006; Skodol 2005). There is a particularly strong association between AsPD and substance use disorders (Robins 1998). Compared to those without AsPD, those with AsPD are 15 times more likely to meet the criteria for drug dependence, and seven times more likely to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence (Trull 2010). Guy 2018 reported that 77% of people with AsPD met the lifetime criteria for alcohol use disorder.

Description of the intervention

It has been argued that adults with personality disorders may respond to pharmacological interventions that target both their state (temporary/transient) and trait (stable/enduring) symptoms, highlighting the need to evaluate drug treatments that target the cognitive‐perceptual, affective, impulsive‐behavioural and anxious‐fearful domains of personality disorder (Soloff 1998). Several authors have reviewed the evidence relating to treatment of personality disorders with antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, psychostimulants, antipsychotics and mood stabilisers (Stein 1992; Dolan 1993; Warren 2001; Duggan 2008; Lieb 2010).

Stein 1992 concluded that small doses of neuroleptics may afford some benefits for people with well‐defined borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Dolan 1993 argued that carbamazepine had been shown to improve overactivity, aggression and impulse control in psychopathic and antisocial personality disorders. They also concluded that lithium maintenance treatment may be of benefit to explosive and impulsive individuals, holding some hope for those with AsPD. Warren 2001 concluded that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants may improve personality disorder symptoms and anger. They noted, however, that the evidence for pharmacological intervention was very poor, since the studies included in their review suffered serious methodological limitations, including small sample sizes, highly selected participants, high dropout rates, short duration or lack of long‐term follow‐up. Similar limitations were noted by Duggan 2008, although their review favoured the use of anticonvulsants to reduce aggression, and anti‐psychotics to reduce cognitive perceptual and mental state disturbance.

Overall, these reviews found the evidence base for pharmacological interventions for AsPD to be weak, or lacking, since the bulk of the studies reviewed had been restricted to individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Therefore, it is important to consider all relevant studies, without restriction on the pharmaceutical agents, and to consider pharmacological interventions where drugs are given not only as monotherapy but also as an adjunctive intervention.

How the intervention might work

Several arguments have been put forward to justify pharmacological treatment for personality disorders (Tyrer 2004), and there is a growing body of evidence that personality disorders are associated with neurochemical abnormalities, whether inherited or arising out of physical or psychological trauma (Coccaro 1998; Skodol 2002). One justification for the use of pharmacotherapy is that it has the potential to modulate neurotransmitter function and so may be able to correct imbalances in the central nervous system of people with personality disorder to a more normal neurochemical state (Markovitz 2004).

The main neurotransmitter system which may be implicated in AsPD is the serotonergic system (Coccaro 1996; Deakin 2003). For example, impulsive and aggressive features of the disorder have been linked to serotonergic system deficits (Sugden 2006). The serotonergic system has been found to be less responsive to pharmacological challenges (i.e. a study where drugs are given to increase serotonin levels) in people with AsPD than those in healthy individuals (Moss 1990). Brain activations following such challenges are reduced in AsPD participants, as demonstrated in functional imaging studies (Völlm 2010). The biological factors contributing to both antisocial behaviour and criminality may also include the under‐arousal of the autonomic system (Dinn 2000; Raine 2000). Raised testosterone levels have been implicated in a range of antisocial behaviours, psychosocial problems, psychoactive substance misuse and violence (Mazur 1998), but no argument has been put forward to justify the use of antiandrogens in AsPD.

In an alternative approach, Soloff 1998 suggests that the likely impact of drugs on the primary symptoms in personality disorder can broadly be predicted from drug effects when used in other disorders such as anxiety, depression or psychosis. On this basis, medication is matched to the primary symptom group, so that antipsychotic medication would be the preferred drug treatment for cognitive‐perceptual symptoms, and mood stabilisers and SSRIs would be indicated for impulsive‐behavioural dyscontrol.

In practice, there are reports of behavioural dyscontrol improving in response to lithium (Links 1990) and anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine (Cowdry 1988), sodium valproate (Stein 1995) and divalproex sodium (Wilcox 1995) in non‐AsPD samples. There are also a number of reports on the use of SSRIs to reduce aggressive and impulsive behaviour (Bond 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

AsPD is an important condition that has a considerable impact on individuals, families and society more widely (Black 1999; NICE 2010). Even by the most conservative estimate, AsPD appears to have the same prevalence in men as schizophrenia, the condition that receives the greatest attention from mental health professionals. Furthermore, AsPD is associated with significant costs (Sampson 2013), arising from emotional and physical damage to victims and damage to property, as well as service utilisation (for instance, in terms of health services, use of police time, and involvement from the criminal justice system and prison services). Related costs include increased use of healthcare facilities, lost employment opportunities, family disruption, gambling, and problems related to alcohol and substance misuse (Myers 1998; Home Office 1999). In one study, lifetime public costs for a group of adults with a history of conduct disorder were found to be 10 times those for a similar group without the disorder (Scott 2001). Around 50% of adolescents with conduct disorder will go onto develop adult AsPD (Scott 2001).

Despite this, there is currently a dearth of evidence on how best to treat people diagnosed with AsPD, and the few reviews that have been carried out to date have been inconclusive. Dolan 1993 reviewed the use of numerous drug groups amongst people with AsPD and psychopathic disorder, but identified only a small number of studies, and noted that these were limited by poor methodology and lack of long‐term follow‐up. They found the evidence base for pharmacological treatments for AsPD to be poor, a conclusion endorsed by the Reed Committee (Reed 1994). They recommended that the UK Department of Health and the Home Office should encourage further research into this area, with added attention to female and ethnic minority groups (Reed 1994). A further review failed to uncover a more credible evidence base (Warren 2001). Increased interest in developing and evaluating pharmacological treatments for personality disorders in recent years has provided the impetus to conduct the first Cochrane Review, which systematically reviewed the literature on the use of pharmacological interventions for AsPD up to 2010 (Khalifa 2010). New evidence has emerged since then, suggesting that an updated systematic review is now timely.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and adverse effects of pharmacological interventions for adults with AsPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), in which participants have been randomly allocated to an experimental group and a placebo control group. We included all relevant RCTs, including cross‐over trials, with or without blinding, published in any language.

Types of participants

We included studies involving adult (18 years or over) men or women with a diagnosis of AsPD or dissocial personality disorder defined by the DSM (DSM‐IV; DSM‐IV‐TR; DSM‐5) and ICD‐10 diagnostic classification systems. We excluded studies of people with major functional mental illnesses (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder), organic brain disease, and intellectual disability. The decision to exclude persons with these conditions is based on the rationale that the presence of such disorders (and the possible confounding effects of any associated management or treatment) might obscure whatever other psychopathology (including personality disorder) might be present. However, we included studies of people diagnosed AspD who also had other comorbid personality disorders or other mental health problems. We placed no restrictions on setting and included studies with participants living in the community as well as those incarcerated in prison or detained in hospital settings. We included studies with subsamples of patients with AsPD provided that the data for this group were available separately. We also included studies where participants with a AsPD diagnosis comprised at least 75% of the sample. Lastly, we required studies where participants with antisocial or dissocial personality disorder formed a small subgroup to have randomised at least five people with AsPD.

Types of interventions

People with personality disorders may respond to pharmacological interventions that target both their state and trait symptoms. Although it has been argued that drug treatments that target the cognitive‐perceptual, affective, impulsive‐behavioural and anxious‐fearful domains of personality disorder need to be evaluated (Soloff 1998), we carried out the review without any a priori assumptions about the effectiveness of certain drugs in a specific domain.

We included studies of any drug(s) with psychotropic properties, including those falling within the following classes of pharmacological interventions (as defined by the British National Formulary 2018):

hypnotics, anxiolytics and barbiturates;

antipsychotic drugs (including depot injections);

antidepressant drugs; tricyclic and related, monoamine‐oxidase inhibitors, SSRIs and related, and other antidepressant drugs;

central nervous system stimulants;

antiepileptics, mood stabilising agents/antimanic drugs;

drugs used in essential tremor, chorea, tics and related disorders;

drugs used in substance dependence;

dopaminergic drugs used in Parkinsonism; and

others.

We included studies evaluating a combination of drug interventions. We included studies in which the drug being evaluated was given as an adjunct to another drug, but only where the comparison was between the adjunct and a placebo adjunct. Studies in which the comparison was between one drug and another drug or between a pharmacological and a psychological intervention are reported separately. We considered cross‐over trials for inclusion in the review only where the trial was evaluating interventions with a temporary effect in the treatment of stable conditions, and where long‐term follow‐up was not required (Higgins 2011a). A summary of the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the review is provided in Table 10.

4. Summary of the review inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | ||||

| Studies | Participants | Interventions | Primary outcomesa | Secondary outcomesa |

|

|

|

|

|

| Exclusion criteria | ||||

| Studies | Participants | Interventions | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes |

| ‐ |

|

|

‐ | ‐ |

aStudies reporting on at least one primary or secondary outcome were considered for inclusion. bThese studies are reported separately.

We included studies where the active drug treatment was compared to an inert 'placebo' (dummy pill/capsule/liquid) containing an inactive substance such as starch, sugar or saline.

Types of outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcomes are listed below in terms of single constructs. Given the relatively stable nature of traits of AsPD (by definition) we chose outcomes that could be subject to change and that were potentially measurable by a variety of means (including self‐report and observation).

Some traits, such as risk‐taking, are difficult to measure directly. Given the large negative impact of aggression and reconviction, we thought these particularly important. Such outcomes could represent a final common pathway encompassing a variety of traits, including failure to confirm to social norms, deceitfulness, impulsivity, recklessness, irresponsibility and lack of remorse. These outcomes are also measurable by self‐report, psychometrics, observed behaviour, informant information and official records. We were also mindful of the issues described in DSM‐5 (p 659): “Because deceit and manipulation are central features of antisocial personality disorder, it may be especially helpful to integrate information acquired from systematic clinical assessments with information collected from collateral sources." We anticipated that the studies included in this review would have used a range of outcome measures (for example, aggression could have been measured by a self‐report instrument or by an external observer). We provide examples of potential measures of each outcome. However, we also accepted other, similar ways of recording each outcome.

Whilst acknowledging that the nature of the disorder can lead to difficulty in long‐term follow‐up of individuals with AsPD, we reported relevant outcomes without restriction on period of follow‐up. We aimed to divide outcomes into immediate (within six months), short‐term (> 6 months to 24 months), medium‐term (> 24 months to five years) and long‐term (beyond five years) follow‐up, if there were sufficient studies to warrant this.

Primary outcomes

Aggression (trait aggression or state/dynamic/current aggression; reduction in aggressive behaviour or aggressive feelings; continuous or dichotomous outcome), measured through improvement in scores on the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss 1992), the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (Malone 1994), or a similar, validated instrument; or as number of observed incidents.

Recidivism (continuous, dichotomous or time‐to‐event outcome depending on how these data were reported), measured as reconviction in terms of the overall reconviction rate or numbers reconvicted for the sample (continuous data), time to reconviction/reoffending (time‐to‐event data), recidivism yes or no (dichotomous). Non‐convicted offences identified by self‐report or incident reporting, etc. and reported in the same way.

Global state/functioning (continuous outcome), measured through improvement on the Global Assessment of Functioning numeric scale (DSM‐IV‐TR).

Social functioning (continuous or dichotomous outcome), measured through improvement in scores on the Social Adjustment Scale (Weissman 1976), the Social Functioning Questionnaire (Tyrer 2005), or a similar, validated instrument; or a proxy measure of social functioning (e.g. decreased level of support required/time taken to achieve leave from hospital).

Adverse events (dichotomous outcome), measured as incidence of overall adverse events and of the three most common adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life (self‐reported improvement in overall quality of life; continuous outcome), measured through improvement in scores on the European Quality Of Life instrument (EuroQoL Group 1990), or a similar, validated instrument.

Engagement with services (health‐seeking engagement with services; continuous outcome), measured though improvement in scores on the Service Engagement Scale (Tait 2002), or a similar, validated instrument.

Satisfaction with treatment (continuous outcome), measured through improvement in scores on the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (Attkisson 1982), or a similar, validated instrument.

Leaving the study early (continuous or dichotomous outcome), measured as proportion of participants discontinuing treatment.

Substance misuse (continuous or dichotomous outcome), measured as improvement on the Substance Use Rating Scale, patient version (Duke 1994), or a similar, validated instrument.

Employment status (continuous outcome), measured as number of days in employment over the assessment period.

Housing/accommodation status (continuous outcome), measured as number of days living in independent housing/accommodation over the assessment period.

Economic outcomes (any economic outcome such as cost‐effectiveness; continuous outcome), measured using cost‐benefit ratios or incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

Impulsivity (state or trait; self‐reported improvement in impulsivity; continuous outcome), measured through reduction in scores on the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (Patton 1995), or a similar, validated instrument.

Anger (self‐reported improvement in anger expression and control; continuous outcome), measured through reduction in scores on the State‐Trait Anger Expression Inventory‐2 (Spielberger 1999), or a similar, validated instrument.

Mental state (continuous outcome): general mental state, such as ratings of general mental health symptoms, measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall 1962) or Symptom‐Check List‐90 (SCL‐90; Derogatis 1973); or specific symptoms, such as dissociative experiences measured by Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES; Carlson 1993), mood/anxiety measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983) or the Beck Anxiety and Depression Scale (BADS; Beck 1988); or global mental health, measured by Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE‐OM; Barkham 2001).

Prison/service outcomes (continuous outcome) recording: treatment of people in the community; duration of treatment programme; or changes in services provided by through care/probation teams.

Other outcomes measured in the included studies that did not fall into one of the above categories (continuous or dichotomous outcomes dependent upon how the outcomes were reported).

Search methods for identification of studies

The searches for the previous version of this review were designed to find studies for a suite of reviews on a range of personality disorders. For this update, we revised the population section of the strategy by including only the search terms relevant to antisocial personality disorder. We also made changes to the databases we searched (see Differences between protocol and review).

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases and trial registers (to update the search conducted for Khalifa 2010) on 3 October 2016, 31 October 2017, 3 and 4 October 2018 and 5 September 2019.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 9), in the Cochrane Library (searched 5 September 2019), which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register.

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to August Week 5 2019).

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations Ovid (searched 5 September 2019).

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print Ovid (searched 5 September 2019).

Embase OVID (1974 to 2019 Week 37).

CINAHL Plus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 5 September 2019).

PsycINFO OVID (1967 to September Week 1 2019).

Science Citation Index Web of Science (1970 to 5 September 2019).

Social Sciences Citation Index Web of Science (1970 to 5 September 2019).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science Web of Science (1990 to 5 September 2019).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science & Humanities Web of Science (1990 to 5 September 2019).

Sociological Abstracts Proquest (1952 to 5 September 2019).

Criminal Justice Abstracts EBSCOhost (1910 to 5 September 2019).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2019, Issue 9), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 5 September 2019).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (2015, Issue 2. Final Issue), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 5 September 2019).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home; searched 5 September 2019).

WHO (World Health Organization) ICTRP (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx; searched 5 September 2019).

WorldCat (limited to theses; www.worldcat.org; searched 5 September 2019).

Detailed search strategies for this update are reported in Appendix 1. The searches were designed to find records for two separate reviews of interventions for AsPD or dissocial personality disorder: a) psychological interventions and b) pharmacological interventions. For this review, we selected only those studies that were relevant to pharmacological interventions. Search strategies used up to September 2009 for the previous version of the review are reported in Khalifa 2010.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of included and excluded studies for additional trials. We also examined bibliographies of systematic reviews identified in the search to identify relevant studies. We contacted the authors of relevant studies to enquire about other sources of information, and contacted the first author or corresponding author of each included study for information regarding unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

In the following sections, we report only the methods that we were able to use in this review. We direct the reader to our protocol, Khalifa 2009, and Table 11, for information on additional methods that we intend to use in future updates of this review, should data permit.

5. Additional methods for future updates.

| Issue | Method |

| Types of outcome measures | We may reconsider the primary and secondary outcomes in future reviews, to include pre‐clinical markers such as 'facial emotional recognition' or additional features of AsPD as listed in DSM‐5, ICD‐10, or future iterations of these guidelines e.g. ICD‐11. |

| Unit of analysis issues |

Cluster‐randomised trials Where trials use clustered randomisation, study investigators may present their results after appropriately adjusting for clustering effects (robust standard errors or hierarchical linear models). Where it is unclear whether this was done, we will contact the study investigators for further information. If appropriate adjustments were not used, we will request individual participant data and re‐analyse using multilevel models which control for clustering. Following this, we will carry out meta‐analysis in Review Manager 5 (RevMan5; Review Manager 2014), using the generic inverse method (Higgins 2011a). If appropriate adjustments were not used, we will follow the method described by Donner 2001, imputing an intra‐cluster correlation coefficient and adjusting for sample size. If there is insufficient information to adjust for clustering, we will enter outcome data into RevMan5 using the individual as the unit of analysis, and then use sensitivity analysis used to assess the potential biasing effects of inadequately adjusted clustered trials. |

|

Cross‐over trials Should we be able to conduct a meta‐analysis combining the results of cross‐over trials, we will use the inverse variance methods recommended by Elbourne (Elbourne 2002), data permitting. When conducting a meta‐analysis combining the results of cross‐over trials. | |

| Dealing with missing data |

Missing dichotomous data We will report missing data and dropouts for each included study and report the number of participants who are included in the final analysis as a proportion of all participants in each study. We will provide reasons for the missing data in the narrative summary where these are available. |

|

Missing standard deviations The standard deviations of the outcome measures should be reported for each group in each trial. If these are not given, we will calculate these, where possible, from standard errors, confidence intervals, t‐values, F values or P values using the method described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 7.7.3.3 (Higgins 2011a). If these data are not available, we will impute standard deviations using relevant data (for example, standard deviations or correlation coefficients) from other, similar studies (Follman 1992) but only if, after seeking statistical advice, to do so is deemed practical and appropriate. Given that trials in this area are often conducted with small samples, any imputations (and the assumptions behind them) are likely to have an important impact. We will therefore follow, where possible, the method suggested by Higgins 2008 for weighting studies with imputed data. | |

|

Loss to follow up We will report separately all data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow‐up, and will exclude these from any meta‐analyses. The impact of including studies with high attrition rates (25 to 50%) will be subjected to sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this group results in a substantive change in the estimate of effect of the primary outcomes, we will not add data from these studies to trials with less attrition, but will present them separately. We will assess the extent to which the results of the review could be altered by the missing data by conducting a sensitivity analysis based on consideration of 'best‐case' and 'worst‐case' scenarios (Gamble 2005). Here, the 'best‐case' scenario is that where all participants with missing outcomes in the experimental condition had good outcomes, and all those with missing outcomes in the control condition had poor outcomes; the 'worst‐case' scenario is the converse (Higgins 2011a, section 16.2.2).For example, in studies with less than 50% dropout rate, we will consider people leaving early to have had the negative outcome, except for adverse effects such as death. | |

| Assessment of heterogeneity | We will assess the extent of between‐trial differences and the consistency of results of any meta‐analysis in three ways: first, by visual inspection of the forest plots; second, by performing the Chi2 test of heterogeneity (where a significance level less than 0.10 will be interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity); and third, by examining the I2statistic (Higgins 2011a; section 9.5.2). The I2statistic describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. We will consider I2values less than 30% as indicating low heterogeneity, values in the range 31% to 69% as indicating moderate heterogeneity, and values greater than 70% as indicating high heterogeneity. We will attempt to identify any significant determinants of heterogeneity categorised at moderate or high. |

| Assessment of reporting biases | We will draw funnel plots (effect size versus standard error) to assess publication bias, if we find sufficient studies. Asymmetry of the plots may indicate publication bias, although they may also represent a true relationship between trial size and effect size. If such a relationship is identified, we will further examine the clinical diversity of the studies as a possible explanation (Egger 1997; Jakobsen 2014; Lieb 2016). If insufficient data is available to employ statistical techniques, we will look at descriptive methods (such as time elapsed between the study and publication) to assess potential reporting bias. |

| Data synthesis | We will conduct meta‐analyses to combine comparable outcome measures across studies. In carrying out meta‐analysis, the weight to be given to each study is the inverse of the variance, so that the more precise estimates (from larger studies with more events) are given more weight. Where studies provide both endpoint and change data for continuous outcomes, we will perform a meta‐analysis that combines both types of data using the methods described by Da Costa 2013. We will undertake a quantitative synthesis of the data using both fixed and random effects models. Random‐effects models will be used because studies may include somewhat different treatments or populations. Outcome measures will be grouped by length of follow‐up. In addition, the weighted average of the results of all the available studies will be used to provide an estimate of the effect of antiepileptic drugs for aggression and impulsiveness. Where appropriate and if a sufficient number of studies are found, we will use regression techniques to investigate the effects of differences in the study characteristics on the estimate of the treatment effects. Statistical advice will be sought before attempting meta‐regression. If meta‐regression is performed, this will be executed using a random effects model. We will consider pooling outcomes reported at different time points where this does not obscure the clinical significance of the outcome being assessed. To address the issue of multiplicity, future reviews should consider the following:

|

| Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity | We will undertake a subgroup analysis to examine the effect on primary outcomes of:

|

| Sensitivity analysis | We will undertake sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the overall findings in relation to certain study characteristics. A priori sensitivity analyses are planned, data permitting, for:

|

Selection of studies

Working independently, two review authors read the titles and abstracts generated by the searches and discarded those that were clearly irrelevant. . They next obtained the full‐text reports of those deemed potentially relevant or which more information was needed to determine relevance, and assessed them against the inclusion criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). The reviewers resolved uncertainties concerning the appropriateness of studies for inclusion in the review through consultation with a third review author who had not been involved in the initial screening.

For studies reported in a language other than English, we initially examined the English version of the title and abstract, where provided, to decide whether or not the study met the inclusion criteria. We obtained a translation of any non‐English language abstract or full paper where this was necessary for a decision to be made; two of the review authors undertook translations for three records.

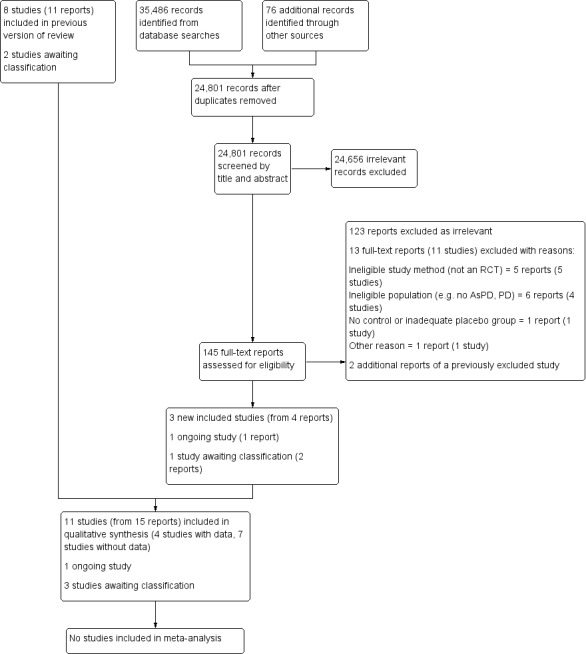

We present our selection process in a PRISMA diagram (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

Four review authors extracted data independently for all studies using a data extraction form which had previously been piloted (see Appendix 2). Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted the study authors and asked them to supply the missing information. Two review authors entered the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014); a third review author checked the data entry into RevMan for accuracy. Study data was finalised through comparison and consensus of two independent extractions with any disagreements resolved by consultation with a third author; less than 5% of papers required such discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, two reviewers independently completed Cochrane’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b), resolving any disagreements through consultation with a third reviewer. We assessed the papers against the following areas of possible bias:

random sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants (performance bias);

blinding of personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective outcome reporting; and

other bias, including allegiance bias and treatment adherence.

For each domain, we assigned ratings of 'high,' 'low' or 'unclear' risk of bias, where we considered the risk of bias to be high, low or uncertain/unknown, respectively.

Overall risk of bias

We assessed the overall risk of bias within studies using the method recommended by Higgins 2011b. We assessed a study at low risk of bias overall if we rated it at low risk of bias on all key domains; at unclear risk of bias overall where we assessed the study at unclear risk of bias on one or more key domains; and at high risk of bias overall where we rated the study at high risk of bias on one or more key domains. If a single domain was rated at high risk but other domains were unclear, we rated the study at high risk of bias overall. We used the results of this assessment to inform our GRADE judgements (see section on 'Summary of findings' below).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous (binary) data, we used the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), to summarise results within each study. We chose the OR because it has statistical advantages relating to its sampling distribution and its suitability for modelling, and because it is a relative measure and therefore can be used to combine studies.

Continuous data

For continuous data, such as the measurement of impulsiveness and aggression on a scale, we compared the mean score for each outcome as determined by a standardized tool between the two groups to give a mean difference (MD), and presented these with 95% CI. We used the mean difference (MD) where more than one study reported the same outcome measures. We used the standardized mean difference (SMD) where studies reported different outcome measures of the same construct.

We reported continuous data that were skewed in a separate table, and did not calculate treatment effect sizes in order to minimise the risk of applying parametric statistics to data that depart significantly from a normal distribution. However, if the trial investigators provided results of their own statistical analysis on such data, we reported their results descriptively within the section on Effects of interventions. We define skewness as occurring when, for a scale or measure with positive values and a minimum value of zero, the mean was less than twice the standard deviation (Altman 1996).

Time‐to‐event data

For time‐to‐event data, we used the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI. Reconviction (dichotomous or time‐to‐event outcome dependent upon how the outcome was reported), was measured as the overall reconviction rate for the sample or as an analysis of time to reconviction (please see Differences between protocol and review).

Other

Where possible, we made comparisons at specific, clinically relevant follow‐up periods: immediate (within six months), short‐term (> 6 months to 24 months), medium‐term (> 24 months to five years) and long‐term (beyond five years) follow‐up (please see Differences between protocol and review).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials. For information on how we will handle these issues should they arise in future updates of this review, please see our protocol, Khalifa 2009, and Table 11.

Cross‐over trials

We identified two cross‐over trials but only one provided cross‐over data for one comparison. Where data presented from a cross‐over trial were restricted (and more information was not available from the original investigators), we presented data within the first phase only, up to the point of cross‐over.

Multi‐arm trials

We identified three multi‐arm trials. We included all eligible outcome measures for all trial arms in this review. We used pair‐wise comparisons of individual trial arms against placebo to avoid a potential unit‐of‐analysis error from this approach.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the original investigators to request any missing or incomplete outcome data and information on whether or not the data could be assumed to be ‘missing at random.' If these data were made available to us, we included the data in the review. If data were not forthcoming, we attempted to contact at least one of the co‐investigators. We permitted a reasonable length of time (at least 12 weeks) for the investigator(s) to supply the missing data before we proceeded with the analysis. We considered 12 weeks to be sufficient, as most contacts provided a response within a few days.

We used intention‐to‐treat analysis for studies with data missing from participants who dropped out of trials before completion. We assumed missing data were random if no explanation was received from study authors, and reported missing data information in the 'incomplete outcome data' section of the 'Risk of Bias' tables. See Table 11 for information about future updates of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the clinical heterogeneity of trials in relation to the medication type, clinical setting, and the population from which AsPD participants were drawn. We assessed the methodological heterogeneity in relation to the trial design (e.g. parallel/cross‐over). Please see Table 11 for information about assessment of heterogeneity in future updates of this review where pooling may be required.

Assessment of reporting biases

Due to insufficient data we were unable to conduct our preplanned funnel plots (Khalifa 2009; Table 11) to assess reporting bias. Please see Table 11 for information about future updates of this review.

Data synthesis

Due to insufficient data we were unable to conduct meta‐analyses, and therefore provide a narrative summary of the data. Although we considered multiplicity (the concern that performing multiple comparisons increases the risk of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis) this was not an issue in this review as the available data did not allow the making of multiple comparisons. We have outlined how we will address multiplicity and other issues in future reviews in Table 11.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Due to insufficient data we were unable to conduct any of our preplanned subgroup analyses (see Khalifa 2009). See Table 11 for information about future updates of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

Due to insufficient data we were unable to conduct any of our preplanned sensitivity analyses (see Khalifa 2009). See Table 11 for information about future updates of this review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Following the guidelines set out in Schünemann 2013, we used GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT) to prepare a 'Summary of findings' table for the following comparisons.

Phenytoin (antiepileptic) versus placebo

Desipramine (antidepressant) versus placebo

Nortriptyline (antidepressant) versus placebo

Bromocriptine (dopamine agonist) versus placebo

Amantadine (dopamine agonist) versus placebo

We included all primary outcomes (aggression, reconviction, global/state functioning, social functioning and adverse events), for immediate, short, medium and long‐term time points, in the 'Summary of findings' tables, presenting pooled data where possible, and single study data narratively.

Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of evidence for all primary outcomes with available data using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2013), which takes into account the risk of bias, level of inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. We rated the certainty of the evidence for each outcome as being high, moderate, low or very low, and where relevant, provided reasons for downgrading the certainty of the evidence in the footnotes of the tables. We resolved any disagreements by discussion, or in consultation with a third review author. Less than 5% of studies required this discussion.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For the original version of this review (Khalifa 2010), we searched from the inception of each database to September 2009. These searches identified in excess of 16,398 records, 26 of which appeared to merit closer inspection. From these, we identified eight studies (from 11 reports) that met the eligibility criteria.

We ran the searches for this update from September 2009 to September 2019. and found a total of 35,562 records. Once duplicate records were removed, we were left with 24,801 unique records, which we screened by title and abstract. We excluded 24,656 irrelevant records, and retrieved the full texts of the remaining 145 records for closer inspection. From these, we identified three new studies (from four reports) that fully met the inclusion criteria. We calculated the inter‐rater agreement for the selection of studies by the review authors, and obtained a kappa of 0.69; the strength of this agreement is classified as good by Altman 1996 (< 0.20 = poor; 0.21 to 0.40 = fair, 0.41 to 0.60 = moderate; 0.61 to 0.80 = good, and 0.81 to 1.00 = very good).

In total, this review now has 11 included studies (from 15 reports) and 29 excluded studies (from 33 reports). Three studies are awaiting classification, and one study is ongoing. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies for this updated review, as recommended by Stovold 2014.

1.

Study flow diagram showing the results of the updated literature search (5 September 2019)

Included studies

We identified 11 studies (416 AsPD participants) that fully met the inclusion criteria (Arndt 1994; Leal 1994; Powell 1995; Barratt 1997; Stanford 2001; Hollander 2003; Stanford 2005; Ralevski 2007; Coccaro 2009; Gowin 2012; Konstenius 2014). All participants with AsPD in the included studies were diagnosed under DSM criteria. Data from those participants with AsPD were available for only four of the 11 studies (Arndt 1994; Leal 1994; Powell 1995; Barratt 1997). The data from the remaining seven studies were not available for the following reasons. The AsPD data reported by Ralevski 2007 were not split by allocation condition, and no data on the AsPD subgroup were available for Stanford 2001, Hollander 2003, Stanford 2005, Coccaro 2009, Gowin 2012 and Konstenius 2014 at the time this review was prepared. We made four requests for further information and received one response from the authors of the Coccaro 2009 study (see 'Notes' section in Characteristics of included studies for details). The 11 included studies involved a total of 15 comparisons of a drug versus placebo. There were some important differences between the studies. We summarise these differences and the main study characteristics below. Further details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Design

Nine of the 11 included studies were parallel RCTs (Arndt 1994; Leal 1994; Powell 1995; Hollander 2003; Stanford 2005; Ralevski 2007; Coccaro 2009; Gowin 2012; Konstenius 2014) and two were cross‐over designs (Barratt 1997; Stanford 2001). Of the nine parallel RCTs, five were two‐condition comparisons of a drug against a placebo (Arndt 1994; Hollander 2003; Coccaro 2009; Gowin 2012; Konstenius 2014), two were three‐condition comparisons of two drugs against a placebo (Leal 1994; Powell 1995), one was a four‐condition comparison involving three drugs against a placebo (Stanford 2005), and one was a four‐condition comparison of two drugs against placebo, both separately and in combination with each other (Ralevski 2007). Both studies with cross‐over designs were of a single drug against a placebo (Barratt 1997; Stanford 2001) and both recruited participants with recurrent aggression.

Sample sizes

There was some variation in sample size among studies. Ten studies unambiguously reported the number of randomised participants with AsPD (387 AsPD participants randomised); the sample size for these studies ranged from 6 (Gowin 2012) to 150 (Barratt 1997) (mean = 38.7, median = 18.0). The number with AsPD randomised in the eleventh study was not reported, although 29 AsPD participants completed to the study endpoint (Arndt 1994).

However, sample size data were available to us for only four trials (which include Arndt 1994). In these four studies, 274 participants with AsPD were randomised, with the sample size ranging from 19 (Leal 1994) to 150 (Barratt 1997) (mean = 68.5, median = 52.5; calculation based on an assumption that 50% of the Arndt 1994 sample was AsPD). The proportion of participants completing was reported unambiguously in only three of the four studies: 84% for Barratt 1997 in a prison sample; 57.9% for Leal 1994 in an inpatient sample; and 44.6% for Powell 1995 where participants were in an outpatient setting at the study endpoint.

It is important to note that none of the 11 studies set out to recruit participants on the basis of having a diagnosis of AsPD. In 10 studies, participants with AsPD formed a subgroup that accounted for between 4% and 59% of the trial's sample. However, in one study (Barratt 1997), participants were recruited on the basis of recurrent aggression and subsequent assessment revealed that 100% met the criteria for AsPD.

Setting

All but one of the studies were carried out in North America; Konstenius 2014 was conducted in Sweden. Six were single‐centre trials (Arndt 1994; Leal 1994; Stanford 2001; Stanford 2005; Coccaro 2009; Gowin 2012). Four were multi‐centre trials: Powell 1995 with two sites; Ralevski 2007 and Konstenius 2014 with three sites; Hollander 2003 with 19 sites. One study, Barratt 1997, did not report the number of sites. The trials took place in a number of very different settings. Seven studies were conducted exclusively in an outpatient setting (Arndt 1994; Stanford 2001; Hollander 2003; Stanford 2005; Ralevski 2007; Coccaro 2009; Gowin 2012) and one in an inpatient setting (Leal 1994). One study involved participants who were inpatients at baseline but moved to outpatient status during the course of treatment (Powell 1995). One study was set in prison (Barratt 1997), and one had participants who were prisoners at baseline but moved to outpatient status during the course of treatment (Konstenius 2014).

The duration of the trials ranged between six (Gowin 2012) and 24 weeks (Konstenius 2014; Powell 1995) (mean = 14.2 weeks, median = 13.0 weeks).

Participants

Participants were restricted to males in six studies (Arndt 1994; Powell 1995; Barratt 1997; Stanford 2001; Stanford 2005; Konstenius 2014). The remaining studies had a mix of male and female participants. All studies randomised more men than women. The overall mix was 90% men compared to 10% women. All 11 studies involved adult participants with the mean age per study ranging between 28.6 (Gowin 2012) and 45.1 years (Stanford 2001) (mean = 39.6 years). Five studies focused on participants with substance misuse difficulties. For these, inclusion criteria included cocaine dependency (Arndt 1994), cocaine and opioid dependency (Leal 1994), alcohol dependency (Powell 1995; Ralevski 2007) and amphetamine dependence (Konstenius 2014). The remaining six studies recruited participants on the basis of having displayed recurrent aggression, which was defined as impulsive aggression in four studies (Stanford 2001; Hollander 2003; Stanford 2005; Gowin 2012), as impulsive or premeditated aggression in one study (Barratt 1997), and as intermittent explosive disorder in one study (Coccaro 2009).

The precise definition of AsPD and the method by which it was assessed varied between the studies. Seven studies used DSM‐IV criteria: Hollander 2003; Ralevski 2007; Coccaro 2009; Gowin 2012; and Konstenius 2014 made assessments using the Structured Clinical Interview‐II (SCID‐II), while Stanford 2001 and Stanford 2005 stated "assessed by a licensed clinical psychologist" (further details not reported). Three studies used DSM‐III‐R criteria: Barratt 1997 and Powell 1995 made assessments using the Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview‐Revised (PDI‐R); and Leal 1994 made assessments using the SCID‐II. One study, Arndt 1994, used DSM‐III criteria and made assessments using the NIMH (National Institutes of Mental Health) Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS).

Ethnicity of participants was not always reported. For the six studies where it was, 56.7% of randomised participants were described as either "white" or "Caucasian" (Leal 1994; Powell 1995; Barratt 1997; Hollander 2003; Ralevski 2007; Coccaro 2009).

Interventions

Eleven drugs were compared to placebo in the 11 included studies. These were categorised as follows.

Antiepileptics: carbamazepine (one study: Stanford 2005); phenytoin (three studies: Barratt 1997; Stanford 2001; Stanford 2005); tiagabine (one study: Gowin 2012); valproate (one study: Stanford 2005), and divalproex (one study: Hollander 2003)

Antidepressants: desipramine (two studies: Arndt 1994; Leal 1994); fluoxetine (one study: Coccaro 2009); and nortriptyline (one study: Powell 1995)

Central nervous system (CNS) stimulant: methylphenidate (one study: Konstenius 2014)

Dopamine agonists: amantadine (one study: Leal 1994); and bromocriptine (one study: Powell 1995)

Opioid antagonists: naltrexone (one study: Ralevski 2007)

In each case, the route of administration was oral (by tablets, capsules or liquid). Studies varied in the way they reported the dose administered to the treatment group: a fixed daily dose (mg/day), or an adjusted dose in an attempt to achieve a target blood serum concentration (ng/ml or mg/ml). Details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies tables but can be summarised as follows.

Antiepileptics

One study involved carbamazepine (Stanford 2005: 450 mg/day for men with aggression, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup)

Three studies involved phenytoin (Barratt 1997: 300 mg/day for prisoners with aggression; and Stanford 2001 and Stanford 2005: 300 mg/day for outpatient men with aggression, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup that made up 43% and 59% of the total sample respectively)

One study involved tiagabine (Gowin 2012: 4 to 12 mg/day for community‐living adults on probation or parole, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup that made up 50% of the total sample)

Two studies involved either valproate, full name sodium valproate (Stanford 2005: 750 mg/day for men with aggression, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup that made up 59% of the sample) or divalproex, full name divalproex sodium (Hollander 2003: maximum 30 mg/kg/day for outpatients with aggression, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup that made up 9% of the total population). Divalproex sodium is an equimolar compound of sodium valproate and valproic acid; because these two drugs are regarded as equivalent in efficacy and have similar side effect profiles, we consider them together in this review.

Antidepressants

Two studies involved desipramine (Arndt 1994: 250 to 300 mg/day for men with cocaine dependency; Leal 1994: 150 mg/day for adults with opioid and cocaine dependency)

One study involved fluoxetine (Coccaro 2009: 20 to 60 mg/day for adults with intermittent explosive disorder, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup that made up 12% of the total sample)

One study involved nortriptyline (Powell 1995: 25 to 75 mg/day for men with alcohol dependency)

Central nervous system stimulant

One study involved methylphenidate (Konstenius 2014: 18 to 180 mg/day for male prisoners with co‐diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and amphetamine dependence, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup that made up 52% of the total sample)

Dopamine agnostics

One study involved amantadine (Leal 1994: 300 mg/day for adults with opioid and cocaine dependency)

One study involved bromocriptine (Powell 1995: 15 mg/day for men with alcohol dependency)

Opioid antagonists

One study involved naltrexone (Ralevski 2007: 50 mg/day for adults with alcohol dependency)

The duration of the interventions ranged between six (Gowin 2012) and 24 weeks (Konstenius 2014; Powell 1995) (mean = 12.2 weeks, median = 12.0 weeks). None of the 11 studies followed up participants beyond the end of the intervention period.

All studies had measures in place that would allow for assessment of compliance with the medication regime. Blood tests were used by 10/11 studies (Arndt 1994; Leal 1994; Powell 1995; Barratt 1997; Stanford 2001; Hollander 2003; Stanford 2005; Ralevski 2007; Coccaro 2009; Konstenius 2014) and one study, Gowin 2012, used the timing of opening of the medication bottle and looked at breath alcohol and urine analysis.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Studies varied in terms of choice of primary outcomes considered in this review.

Aggression

Six studies assessed aggression as an outcome: Barratt 1997 using a modification to the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS; a weighted behavioural assessment of aggressive behaviour categories (verbal aggression, physical aggression against objects/self/others; higher scores = more severe aggression)); Hollander 2003 and Coccaro 2009 using the OAS‐Modified (OAS‐M; a weighted clinician‐rated semi‐structured interview; scores range from zero to 100 where higher scores = more severe aggression), but with no data available for the subgroup with AsPD; Stanford 2001 and Stanford 2005 using the OAS, but neither with any data available for the subgroup with AsPD; Gowin 2012 using the Point Subtraction Aggression Paradigm (PSAP; a behavioural measure of aggression in response to provocation), Buss‐Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; 29 items rated on five‐point Likert scale ranging from one (extremely uncharacteristic) to five (extremely characteristic)), Lifetime History of Aggression Questionnaire (LHA; 11‐item, semi‐structured interview assessing three components of aggression history (aggression, social consequences or antisocial behaviour, and self‐directed aggression; total score = sum of total number of occurrences since 13 years old on five‐point scale (zero = no events, two = one, two or three events, three = four to nine events, four = 10 or more events), and Retrospective Overt Aggression Scale (ROAS; a weighted clinician‐rated semi‐structured interview, with scores ranging from zero to 100; higher scores = more severe aggression), but with no data available for the subgroup with AsPD.

Reconviction

No studies reported on reconviction.

Global/state functioning

Four studies assessed global state/functioning as an outcome: Powell 1995 using the Global Assessment Scale (GAS; a clinician‐rated assessment with a range of zero to 100; higher scores indicate better functioning) and the General Severity Index subscale (GSI; average score of all 90 items of the Symptom Check List‐90 (SCL‐90; 90 items rated on five‐point scale of distress ranging from zero (none) to four (extreme)); and Hollander 2003, Coccaro 2009 and Konstenius 2014 using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (three items, across three domains; two domains (severity of illness, global improvement) rated by clinicians on seven‐point scale ranging from one (normal, not at all ill) to seven (among the most extremely ill patients); third domain (efficacy index) also rated by clinicians and ranges from zero (marked improvement and no side‐effects) to four (unchanged or worse and side‐effects outweigh the therapeutic effects)), but had no data available for the subgroup with AsPD.

Social functioning

Only one study, Arndt 1994, considered the outcome of social functioning using the family‐social domain of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; 10‐point interview assessment of lifetime and current problem severity, from zero to one (no real problem, treatment not indicated) to eight to nine (extreme problem, treatment absolutely necessary)) in seven problem areas affected by substance use disorder; ASI also provides composite scores (range from zero = no problems, to one = severe problems) for each domain based on client responses to items measuring behaviour in the 30 days prior to interview).