Abstract

Background

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) affects 4% to 12% of women of reproductive age. The main intervention for acute PID is broad‐spectrum antibiotics administered intravenously, intramuscularly or orally. We assessed the optimal treatment regimen for PID.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of antibiotic regimens to treat PID.

Search methods

In January 2020, we searched the Cochrane Sexually Transmitted Infections Review Group's Specialized Register, which included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from 1944 to 2020, located through hand and electronic searching; CENTRAL; MEDLINE; Embase; four other databases; and abstracts in selected publications.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs comparing antibiotics with placebo or other antibiotics for the treatment of PID in women of reproductive age, either as inpatient or outpatient treatment. We limited our review to a comparison of drugs in current use that are recommended by the 2015 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for treatment of PID.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Two authors independently extracted data, assessed risk of bias and conducted GRADE assessments of the quality of evidence.

Main results

We included 39 RCTs (6894 women) in this review, adding two new RCTs at this update. The quality of the evidence ranged from very low to high, the main limitations being serious risk of bias (due to poor reporting of study methods and lack of blinding), serious inconsistency, and serious imprecision.

None of the studies reported quinolones and cephalosporins, or the outcomes laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion or fertility outcomes. Length of stay results were insufficiently reported for analysis.

Regimens containing azithromycin versus regimens containing doxycycline

We are uncertain whether there was a clinically relevant difference between azithromycin and doxycycline in rates of cure for mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.55; 2 RCTs, 243 women; I2 = 72%; very low‐quality evidence). The analyses may result in little or no difference between azithromycin and doxycycline in rates of severe PID (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05; 1 RCT, 309 women; low‐quality evidence), or adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.34; 3 RCTs, 552 women; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence). In a sensitivity analysis limited to a single study at low risk of bias, azithromycin probably improves the rates of cure in mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.67; 133 women; moderate‐quality evidence), compared to doxycycline.

Regimens containing quinolone versus regimens containing cephalosporin

The analysis shows there may be little or no clinically relevant difference between quinolones and cephalosporins in rates of cure for mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.14; 4 RCTs, 772 women; I2 = 15%; low‐quality evidence), or severe PID (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.23; 2 RCTs, 313 women; I2 = 7%; low‐quality evidence). We are uncertain whether there was a difference between quinolones and cephalosporins in adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment (RR 2.24, 95% CI 0.52 to 9.72; 6 RCTs, 1085 women; I2 = 0%; very low‐quality evidence).

Regimens with nitroimidazole versus regimens without nitroimidazole

There was probably little or no difference between regimens with or without nitroimidazoles (metronidazole) in rates of cure for mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.09; 6 RCTs, 2660 women; I2 = 50%; moderate‐quality evidence), or severe PID (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.01; 11 RCTs, 1383 women; I2 = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence). The evidence suggests that there was little to no difference in in adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.61; 17 studies, 4021 women; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence). . In a sensitivity analysis limited to studies at low risk of bias, there was little or no difference for rates of cure in mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.12; 3 RCTs, 1434 women; I2 = 0%; high‐quality evidence).

Regimens containing clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus quinolone

We are uncertain whether quinolone have little to no effect in rates of cure for mild‐moderate PID compared to clindamycin plus aminoglycoside (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.13; 1 RCT, 25 women; very low‐quality evidence). The analysis may result in little or no difference between quinolone vs. clindamycin plus aminoglycoside in severe PID (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.19; 2 studies, 151 women; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence). We are uncertain whether quinolone reduces adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.72; 3 RCTs, 163 women; I2 = 0%; very low‐quality evidence).

Regimens containing clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus regimens containing cephalosporin

We are uncertain whether clindamycin plus aminoglycoside improves the rates of cure for mild‐moderate PID compared to cephalosporin (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.09; 2 RCTs, 150 women; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence). There was probably little or no difference in rates of cure in severe PID with clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.06; 10 RCTs, 959 women; I2= 21%; moderate‐quality evidence). We are uncertain whether clindamycin plus aminoglycoside reduces adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment compared to cephalosporin (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.18 to 3.42; 10 RCTs, 1172 women; I2 = 0%; very low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We are uncertain whether one treatment was safer or more effective than any other for the cure of mild‐moderate or severe PID

Based on a single study at a low risk of bias, a macrolide (azithromycin) probably improves the rates of cure of mild‐moderate PID, compared to tetracycline (doxycycline).

Plain language summary

Treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease

Review question

We assessed the effectiveness and safety of different treatments for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) that are recommended by current clinical guidelines for treatment of PID (the 2015 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for treatment of PID).

Background

PID is an infection of the upper part of the woman's reproductive system (the womb, the tubes that connect the womb and ovaries, where the egg travels along), the ovaries (which make eggs), and inside the pelvis). It is a common condition affecting women of childbearing age. Symptoms of PID range from none to severe. If effective treatment is not started promptly, the consequences can be infertility (unable to have children), pregnancies outside the womb, and chronic pelvic pain (pain in the lower tummy). There is a wide range of treatment options. The choice is based on severity of symptoms, experience of the doctor, national/international guidelines, and rate of side effects. We wanted to learn if there is a preferable antibiotic (used to treat bacterial infections) therapy with high rates of cure and few side effects to treat PID.

Studies characteristics

We searched the available literature up to 10 January 2020 and included 39 studies with 6894 women with an average of 14 days of treatment and follow‐up (monitoring after treatment). These trials included women of childbearing age with mild to severe PID. Trials mostly used a single or a combination of antibiotics with different administration routes: intravenous (into a blood vessel), intramuscular (into the muscle), and oral (as a tablet). In mild‐moderate cases, intramuscular and oral treatments were prescribed, and in moderate‐severe cases, treatments were usually started in hospital and were completed at home.

Key results

We are uncertain whether one treatment was safer or more effective than any other for the cure of PID. From a single study, at low risk of bias, the use of a macrolide probably improves the rates of cure in mild‐moderate PID.

Apart from one high quality result in one comparison, the quality of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate, the main problems being serious risk of bias (poor reporting of study methods; doctors and women may have known which medicine was given), and results differed across studies.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in women describes inflammation of the upper genital tract and surrounding structures as a result of ascending infection from the lower genital tract – bacteria spread directly from the cervix to the endometrium and on to the upper genital tract (Soper 2010). The signs and symptoms of PID are not specific and may range from asymptomatic to serious illness. PID can produce endometritis, parametritis (infection of the structures near the uterus), salpingitis (infection of the fallopian tubes), oophoritis (infection of the ovary), and tubo‐ovarian abscess (Workowski 2015). Peritonitis (infection inside the peritoneum, the thin layer of tissue lining the abdomen) and perihepatitis (infection around the liver) can also occur. Peritonitis, tubo‐ovarian abscess, and severe systemic illness (e.g. fever and malaise) are considered severe forms of PID; the other forms of presentation are considered mild or moderate according to the subjective opinion of the examining doctor or nurse (Soper 2010).

The most common complaint of PID is lower abdominal pain, with or without vaginal discharge. Specific grading of the clinical presentation using symptom scores has been described (e.g. McCormack 1977; Hager 1989), but has not been validated, and use of these scores is inconsistent. PID does not have a diagnostic gold standard. The most commonly used diagnostic criteria are based on those from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Workowski 2015), namely sexually active young women and other women at risk for sexually transmitted disease (STD) who are experiencing recent pelvic or lower abdominal pain where no cause other than PID can be identified, and one or more of the following minimum criteria are present on pelvic examination: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness. The requirement for all three minimum criteria to be present increases the specificity of the diagnosis but reduces sensitivity.

Two sexually transmitted infections (Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae) have been strongly implicated in the aetiology of PID (Newman 2015); however, based on the pattern of organisms isolated from the upper genital tract, the infection may often be polymicrobial (caused by more than one type of bacteria) (Eschenbach 1975; Arredondo 1997; Baveja 2001; Haggerty 2006). This suggests that initial damage produced by C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae may permit the opportunistic entry of other bacteria, including anaerobes (bacteria that do not need oxygen to grow) (Ross 2014a). However, in many cases, no infection is found in the lower genital tract (Goller 2016).

The public health importance of PID can be estimated from the frequency of chlamydial and gonococcal infections. In 2012, among women aged 15 to 49 years, the estimated global prevalence of chlamydia was 3.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.5% to 4.5%), gonorrhoea was 2% (95% CI 1.4% to 2.8%), and trichomoniasis was 4.0% (95% CI 2.7% to 5.8%) (Rowley 2019). In one prospective study of 1170 women with elevated risk for having chlamydial cervicitis, 8.6% developed PID within three years; among women with chlamydia, the risk ratio (RR) for developing PID was 2.5 (95% CI 1.5 to 4.0) (Ness 2006). In the UK, the prevalence of PID is about 2% among women between 16 and 46 years old (Simms 1999; Datta 2012; Ross 2014a). However, in some other countries, the rates of chlamydia infection are lower, for example, in Jordan it is 0.6% in symptomatic women and 0.5% in asymptomatic women (Mahafzah 2008). Among women with PID, 10% to 20% may become infertile, 40% will develop chronic pelvic pain, and 10% of those who conceive will have an ectopic pregnancy (Blanchard 1998; Ness 2002; Ness 2005; Mahafzah 2008).

The morbidity associated with PID relates to the acute inflammatory process, which can cause abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), and abnormal menstrual bleeding. In addition, long‐term complications secondary to tubal damage occur and include chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility (Workowski 2015). PID has a prevalence of between 2% and 12%, and it cannot be diagnosed reliably from clinical symptoms and signs, which have a positive predictive value for salpingitis of only 65% to 90% compared with laparoscopy (Workowski 2015; CDC 2018). Direct visualization of the fallopian tubes via laparoscopy has a higher sensitivity, but there is considerable inter‐ and intra‐observer reproducibility (Molander 2003). Endometrial biopsy may have some utility (Ross 2004), but is not performed routinely and is of uncertain diagnostic and prognostic value, since endometritis (infection of the inner mucosal lining of the uterus) can persist despite the resolution of clinical symptoms (Ness 2002; Savaris 2007).

The financial cost of pelvic infection has been estimated to exceed USD 2.4 billion in the USA, and the mean total cost per episode is around USD 5000 (Trent 2011). In the UK, the mean cost of a non‐complicated episode of PID is GBP 163 (Aghaizu 2011).

Description of the intervention

The main intervention for acute PID is the use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics which cover C trachomatis, N gonorrhoeae, and anaerobic bacteria. There are three effective routes of administration (intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), or oral (PO)) (Ness 2002; Walker 2007). In refractory cases, surgery to drain an abscess or hydrosalpinx may be necessary. When parenteral treatment is used, it is usually discontinued 24 hours after a woman improves clinically (Workowski 2015).

The optimal treatment strategy is unclear. A variety of antibiotic regimens have been used, with marked geographical variation. Current practice generally involves the use of multiple agents to cover C trachomatis, N gonorrhoeae, and anaerobic bacteria, but the best combination of agents is unknown. The background prevalence and antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacterial pathogens in different regions may influence the choice of empirical therapy.

Guidelines have been produced in the USA (Workowski 2015), and Europe (Judlin 2010a; Ross 2014b), to guide therapy, but these have not been based on a formal systematic review. In addition, to choose an antibiotic for PID treatment, it is necessary to consider its spectrum, cost, adverse effects, and posology (i.e. dosage, interval) to achieve the best balance between compliance and efficacy. There are no current systematic reviews on this topic.

The different antibiotic regimens proposed to treat PID vary in cost, efficacy, and adverse effects. Potential adverse effects include allergic reactions and gastrointestinal symptoms, which can lead to discontinuation of therapy. Lack of evidence is revealed in the current CDC and British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) guidelines, where the authors state that there is limited evidence for the need to eradicate anaerobes and for the use of alternative regimens, such as azithromycin (Workowski 2015), and the comparison between clindamycin plus aminoglycoside and fluoroquinolones (Ross 2014b). Likewise, if the prevalence of N gonorrhoeae is low, the use of fluoroquinolones can be considered if allergy to cephalosporin is an issue (Workowski 2015).

How the intervention might work

It is likely that the intervention works by eradicating bacterial pathogens and reducing the associated inflammation which leads to scarring. Necrotic tissue and pus present in an abscess may prevent antibiotics reaching the infected area. Mechanical drainage of the abscess through open surgery, laparoscopy, or aspiration through a large‐bore needle is likely to work by removing infected material which antibiotics are unable to treat (Workowski 2015). Clinical cure without surgery in women with a tubo‐ovarian abscess is around 75% (DeWitt 2010). The rationale for using broad‐spectrum antibiotics is to cover the wide variety of pathogens found in PID, which include gram‐positive (e.g. Streptococcus), gram‐negative (e.g. Chlamydia, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, Neisseria), and anaerobic bacteria (gram positive or negative: Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides).

Why it is important to do this review

PID is a common disease; for women aged 35 to 44 years in England, it is estimated that 33.6% have experienced at least one episode of PID, diagnosed or not (Price 2017). PID is accompanied by high rates of morbidity in young women (Ness 2002; Morris 2014). It requires effective treatment to reduce the incidence of chronic pelvic pain, infertility, and transmitted STDs. A variety of antibiotic regimens have been proposed to treat PID, which vary in cost, efficacy, and adverse effects, but the optimal treatment strategy is unclear.

Currently there are no systematic reviews of this subject and the optimal treatment strategy is unclear. This review will address clinical questions raised by current guidelines on the treatment of PID (Ross 2014b; Workowski 2015), regarding the effectiveness and safety of nitroimidazole, the relative benefits of azithromycin versus doxycycline, the use of quinolones, and the relative benefits of cephalosporins compared to the most‐used regimen of clindamycin plus aminoglycoside, to inform future guideline development and clinical practice.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of antibiotic regimens to treat PID.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including those which did not describe their method of randomization (i.e. where the authors stated that treatment was randomized without providing further details). We chose randomized trials as they provide the strongest evidence for evaluating the efficacy of therapy (Higgins 2011). We included studies irrespective of publication status or language.

We excluded quasi‐randomized trials because they produce effect estimates indicating more extreme benefits when compared with RCTs (Higgins 2011). We also excluded cross‐over and cluster trials.

Types of participants

Women of reproductive age (14 years or older) diagnosed as having acute PID (symptoms for less than six weeks) based on clinical findings, laparoscopy, endometrial biopsy, or detectable gonorrhoea or chlamydia in the upper genital tract.

We divided women into two groups: mild‐moderate (e.g. absence of tubo‐ovarian abscess) and severe (e.g. systemically unwell, presence of tubo‐ovarian abscess).

Types of interventions

We limited our review to comparison of drugs in current use that are recommended for consideration by the 2015 US CDC guidelines for treatment of PID (Workowski 2015).

We included trials that contained, at least, the following treatments for PID:

azithromycin versus doxycycline;

quinolone versus cephalosporin;

nitroimidazole versus no nitroimidazole;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus quinolone;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside versus cephalosporin.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were measured.

Primary outcomes

Effectiveness: clinical cure according to the criteria defined by the treating physician (e.g. resolution or improvement of signs and symptoms related to PID).

Adverse events: any antibiotic‐related adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy.

Secondary outcomes

Microbiological clearance of C trachomatis (chlamydia) from either the upper or lower genital tract, according to the method provided by the authors.

Microbiological clearance of N gonorrhoeae (gonorrhoea) from either the upper or lower genital tract, according to the method provided by the authors.

Laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion.

Length of stay (for inpatient care).

Fertility outcome based on at least one participant‐reported live birth following PID treatment in women not using effective contraception.

Where studies included women with various types of pelvic infection, we considered only women with endometritis, salpingitis, parametritis, or oophoritis (not related to labour, delivery, cancer, or surgery).

Where studies reported multiple time points, we considered the period between 14 and 28 days after initiation of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified relevant RCTs of 'antibiotic therapy' for 'PID', irrespective of their language of publication, publication date, and publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress). We used both electronic searching in bibliographic databases and handsearching, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Electronic searches

We contacted the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Sexually Transmitted Infections Review Group to implement a comprehensive search strategy capturing as many relevant RCTs as possible in electronic databases. We used a combination of controlled vocabulary (MeSH, Emtree, DeCS, including exploded terms) and free‐text terms (considering spelling variants, synonyms, acronyms, and truncation) for 'pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)' and 'antibiotic therapy', with field labels, proximity operators, and Boolean operators. We presented the search strategies in Appendix 1. Specifically, we searched the following electronic databases.

The Cochrane Sexually Transmitted Infections Review Group's Specialized Register, which includes RCTs from 1944 to 2020 located through electronic searching and handsearching. The electronic databases searched for the register are the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, and Embase.

CENTRAL, Ovid platform (1991 to 10 January 2020).

MEDLINE, Ovid platform (1946 to 10 January 2020).

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid platform (1946 to 10 January 2020).

MEDLINE Daily Update, Ovid platform (1946 to 10 January 2020).

Embase (1947 to 10 January 2020).

LILACS, iAHx interface (1982 to 10 January 2020).

Web of Science (2001 to 10 January 2020).

In MEDLINE, we used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying RCTs: sensitivity and precision maximizing version (2008 revision), Ovid format (Higgins 2011). The LILACS search strategy combined RCTs filter of iAHx interface.

Searching other resources

We searched the following trials registers:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/).

We searched for grey literature in OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu/) (from 1993 to 2014). We contacted authors of all RCTs identified by other methods as well as pharmaceutical companies producing 'antibiotic therapy' for 'pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).'

We handsearched conference proceeding abstracts in the following publications: Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (2008 to January 2020), Sexually Transmitted Diseases (1974 to January 2020), Sexually Transmitted Infections (1996 to January 2020), Journal of Sexual Medicine (2004 to January 2020), Sexual and Relationship Therapy (2000 to January 2020), and the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality's Sexual Science Newsletter (2000 to January 2020).

We handsearched previous systematic reviews on similar topics identified from:

the Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com/);

Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org/).

We handsearched the reference lists of all identified RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In this updated version, two review authors (DGF and JM) performed an initial screen of titles and abstracts retrieved by the updated search, and we retrieved the full text of all potentially eligible studies. Two review authors (DGF and JM) independently examined these studies for compliance with the inclusion criteria and selected studies that met these criteria. We resolved disagreements regarding eligibility by discussion or by consulting a third review author (RFS). We documented the selection process in a PRISMA flow chart. We excluded pelvic infection related to obstetric surgical procedures or in animals. Where a study contained both 'eligible' and 'ineligible' participants, we included a subset of data relating to the 'eligible' participants if sufficient details were provided for analysis.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (DGF, JM) independently extracted the data from each study using a data extraction form that the review authors designed and pilot tested. We collected data from the included studies in sufficient detail to complete the Characteristics of included studies table. We also extracted detailed numerical outcome data in duplicate to allow calculation of Mantel‐Haenszel RRs for each comparison. We examined data for errata, retraction, fraud, and inconsistencies. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by consulting a fourth review author (JR or RFS).

If a study had more than two intervention arms, we included or combined only those that met the predefined inclusion criteria. For instance, if the study compared azithromycin (group A) versus azithromycin plus metronidazole (group B) versus metronidazole plus cefoxitin or doxycycline (group C), and the analysis was between the use or not of metronidazole, we combined groups B and C versus group A. The treatment effect was expressed as rate of cure (%) and its magnitude and direction checked in forest plots to ensure consistency with the original study. Where studies had multiple publications, we used the main trial report as the reference and derived additional details from secondary papers. We corresponded with study investigators for further data as required.

Data collected with the data extraction form included:

-

Study factors:

author, date of publication, journal;

date of study;

study design;

location;

setting;

quality of randomization, treatment allocation, and blinding;

method of PID diagnosis;

sample size.

-

Participant factors:

age, ethnicity;

pregnancy;

presence of intrauterine device (IUD);

duration of symptoms;

presence of abscess (pyosalpinx, tubo‐ovarian abscess).

-

Outcome measured:

method of assessment of pelvic pain and score;

timing of assessment;

adverse events;

additional assessments of outcome: laparoscopy, microbiology, fertility.

-

Intervention factors:

antibiotic given: dose, route, length of therapy;

comparator regimen: dose, route, length of therapy;

additional treatment given.

-

Additional data:

whether contact tracing was performed.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (DGF, JM) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). We resolved disagreements between two review authors by consensus or by involving a third review author (RFS). We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool provided in RevMan Web (RevMan Web 2019). We provided justification for risk of bias (high, low, unclear) in the 'Risk of bias' table by direct reference to the relevant report. We requested missing information from the study investigators using open‐ended questions.

1. Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we verified the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (no randomization);

unclear risk of bias (e.g. authors stated that women were randomized to one of the treatments, without further explanation).

2. Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we verified the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment, and we assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes; alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk of bias (allocation was mentioned without further details).

3.1. Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study, we verified the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered studies to be at:

low risk of bias if participants and personnel were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results (e.g. culture for N gonorrhoeae);

high risk if participants and personnel were not blinded;

unclear risk of bias if no further details were provided.

3.2. Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study, we verified the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low risk of bias if assessors were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results (e.g. culture for N gonorrhoeae);

high risk if assessors were not blinded;

unclear risk of bias if no further details were provided.

4. Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we verified the completeness of data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; 'as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization); or

unclear risk of bias: no further details were provided.

We used a cutoff point of 20% missing data in determining if a study was at low or high risk of bias (Fewtrell 2008).

5. Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all the study's prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study's prespecified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study did not include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); or

unclear risk of bias: no further details were provided.

6. Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by 1. to 5. above)

For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of bias;

high risk of bias; or

unclear whether there was risk of bias.

7. Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). With reference to 1. to 6. above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered that it was likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we used number of events (cure) in the control and intervention groups to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel risk ratios (RR). We presented 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all outcomes. For number need to treat for an additional beneficial (NNTB) or harmful (NNTH) outcome, we followed the recommendation given by Altman (Altman 1998). When we observed a treatment effect (cure), we reported the NNTB with 95% CIs.

When possible, we performed analysis based on intention to treat (ITT). When information for an ITT analysis was not available, we used the results provided by the authors.

We performed meta‐analysis separately for mild‐moderate PID and severe PID. We defined severe PID as the presence of tubo‐ovarian abscess, being systemically unwell, or the presence of peritonitis; mild‐moderate PID as no presence of tubo‐ovarian abscess. We further analyzed cases in these two groups across different classes of antibiotics.

Unit of analysis issues

The primary unit of analysis was an event per woman randomized, which was used to calculate the percentage response rate (e.g. clinical cure).

Dealing with missing data

We analyzed the data on an ITT basis to the greatest degree possible and made attempts to obtain missing data from the original trials. Where we were unable to obtain these data, we considered cases that were lost to follow‐up as treatment failure (worst‐case scenario) in the primary analysis. For other outcomes, we analyzed the available data. We did not analyze data from other reported outcomes (e.g. pooled rates of cure of different diseases, including PID).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic as follows: low (l2 value below 40%), moderate (l2 value 40% to 75%), or high (l2 value above 75%) (Sutton 2008; Higgins 2011). We also assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the t2 and Chi2 statistics.

We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I2 statistic was greater than 40% and either t2 was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. If we detected substantial heterogeneity, we explored possible explanations for it in subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). We took statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, especially if there was any variation in the direction of effect. If so, we used a random‐effects analysis, instead of fixed‐effect analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. Some types of reporting bias (e.g. publication bias, multiple publication bias, language bias, etc.) reduce the likelihood that all studies eligible for a review are retrieved (Higgins 2011). If all eligible studies are not retrieved, the review would be biased. In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimize their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we used a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small‐study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies). There are five possible causes for the asymmetric funnel plot: reporting bias, poor methodological quality, true heterogeneity, artefactual, and chance (Egger 1997). Only through formal statistical analysis or using a 'contour‐enhanced' funnel plot is an explication for these asymmetrical funnel plots possible, which was not performed herein.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager Web (RevMan Web 2019). We used a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that trials were estimating the same underlying treatment effect (i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials' populations and methods were sufficiently similar). We conducted separate analyses for mild‐moderate and severe PID.

If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 40% or greater), we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if a mean treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. We treated the random‐effects summary as the mean range of possible treatment effects, and discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials.

If the mean treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. Where we used random‐effects analyses, we presented the results as the mean treatment effect with 95% CIs, and the estimates of the t2 and I2 statistics.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data were available, we performed the following prespecified subgroup analyses:

route of antibiotic administration (PO, IM, or IV);

length of therapy (less or more than seven continuous days of receiving antibiotics);

detection of chlamydia;

detection of gonorrhoea;

site of initiation of treatment (inpatient or outpatient).

We avoided selective reporting of a particular subgroup by not performing multiple subgroup analyses. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 40% or greater), we used a random‐effects analysis as the primary statistical analysis.

Where there was substantial heterogeneity, we explored possible reasons for this finding by stratifying results according to the characteristics of the study population (e.g. method of PID diagnosis), the intervention (e.g. class of antibiotic used, dose of antibiotic, route of administration), or methodological characteristics (e.g. length of time to outcome measurement).

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook the following sensitivity analysis to investigate whether our conclusions were robust to methodological decisions made by review authors:

risk of bias (restricting analysis to blinded studies at low risk of selection bias).

Summary of findings and assessment of the quality of the evidence

We used GRADEpro software to produce 'Summary of findings' tables (GRADEpro GDT). The GRADE approach considers the following criteria: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness of evidence, imprecision, and publication bias, and specifies four levels of quality: high, moderate, low, and very low, starting from high for RCTs. If there was a flaw in the RCT, we downgraded the quality of the evidence by one or two levels.

Two review authors independently applied GRADE in the 'Summary of findings' tables. We resolved any disagreements by consensus. We downgraded for risk of bias due to crucial risk of bias for two or more criteria. The evidence was downgraded further if there was inconsistency. Inconsistency was based on statistical test for heterogeneity and how much variation there was in the findings of the studies that contributed to the outcome. We also considered imprecision, and downgraded if the CIs were compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups. In each domain, we downgraded one level for serious risk of bias and two levels for very serious risk of bias.

'Summary of findings' tables considering clinical cure in PID according to its severity (mild‐moderate, severe) and the number of adverse events leading to discontinuation of therapy were presented for the following comparisons of PID treatment with regimens containing:

macrolides (azithromycin) compared to tetracycline (doxycycline);

quinolone compared to cephalosporins;

nitroimidazole compared to no nitroimidazole;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to quinolone;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADEpro software ( GRADEpro GDT) to produce 'Summary of findings' tables. The GRADE approach considers the following criteria: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness of evidence, imprecision, and publication bias, and specifies four levels of quality: high, moderate, low, and very low, starting from high for RCTs. If there was a flaw in the RCT, we downgraded the quality of the evidence by one or two levels.

Two review authors independently applied a consistent grading for GRADE in the 'Summary of findings' tables. We resolved any disagreements by consensus. We downgraded for risk of bias due to crucial risk of bias for two or more criteria. The evidence was downgraded further if there was inconsistency. Inconsistency was based on statistical test for heterogeneity and how much variation there was in the findings of the studies that contributed to the outcome. We also considered imprecision, and downgraded if the CIs were compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups. In each domain, we downgraded one level for serious risk of bias and two levels for very serious risk of bias.

Summary of Findings (SoF) tables considering clinical cure in PID according to its severity (mild‐moderate, severe) and the number of adverse events leading to discontinuation of therapy were presented for the following comparisons of PID treatment with regimens containing

macrolides (azithromycin) compared to tetracycline (doxycycline);

quinolone compared to cephalosporins;

nitroimidazole compared to no nitroimidazole;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to quinolone;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin

Results

Description of studies

We included 39 RCTs (two new studies) with a wide range of sample sizes and the quality of evidence ranged from very low to high by some limitations with potentially serious risk of bias.

Results of the search

In the 2017 version, we retrieved 2133 references and screened 2094 records after removing duplicated references. We discarded 1955 records as clearly irrelevant and considered 139 full‐text articles.

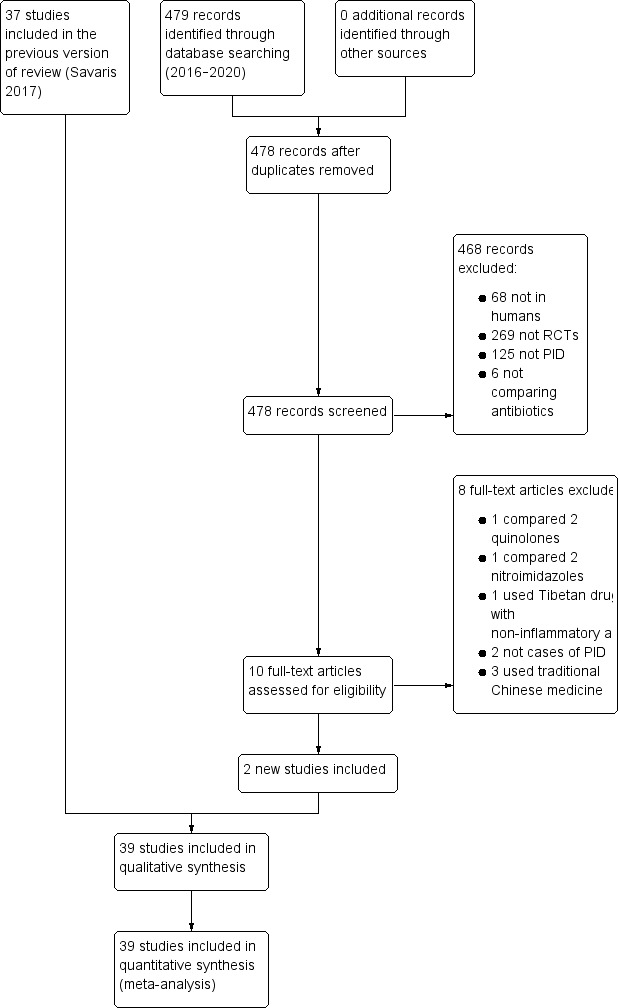

For this updated version, we retrieved 479 references and screened 478 records after removing duplicate references. We discarded 68 records for not dealing with humans, 269 records for not being RCTs, 125 for not being related to PID, and six for not comparing antibiotics. We considered 10 full‐text articles. After full‐text analysis, two new studies met our inclusion criteria and they were included (Figure 1). The reasons for exclusion of the eight full‐text studies are explained in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We extracted data from the full‐text article for each study.

1.

Study flow diagram. PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Included studies

The 39 included trials had 6894 women, with a sample size ranging from 25 (Apuzzio 1989) to 1156 (Aşicioğlu 2013). Retrieved studies came from a wide range of inpatient and outpatient settings from different continents (Americas, Europe, Asia, Oceania, and Africa) and were written in English, German, French, Japanese, and Italian.

For this update, two studies, one from the UK (Dean 2016), and the other from the USA (Wiesenfeld 2017), were added. Dean 2016 compared the rate of cure between ofloxacin 400 mg twice daily plus metronidazole 400 mg twice daily for 14 days versus five days of azithromycin plus metronidazole for 14 days plus ceftriaxone IM. Wiesenfeld 2017 compared ceftriaxone 250 mg IM single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 14 days plus placebo PO twice daily for 14 days versus ceftriaxone 250 mg IM single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 14 days plus metronidazole 500 mg PO twice daily for 14 days.

Population

The included trials recruited girls and women aged 14 years and over with a diagnosis of PID according to CDC criteria (pelvic or lower abdominal pain and one or more of the following clinical criteria: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness) (Workowski 2015). Studies varied in degree of disease severity of participants, treatment location (i.e. inpatient or outpatient), and countries and continents. PID was considered severe in the presence of systemically unwell women, peritonitis, or pelvic abscess.

Interventions

The 39 RCTs yielded 6894 women and made the following comparisons.

For mild‐moderate PID:

macrolides (azithromycin) compared to tetracycline (doxycycline) (Malhotra 2003; Savaris 2007);

quinolone compared to cephalosporins (Wendel 1991; Martens 1993; Arredondo 1997; Dean 2016);

nitroimidazole compared to no use of nitroimidazole (Burchell 1987; Tison 1988; Hoyme 1993; Ross 2006; Judlin 2010b; Aşicioğlu 2013; Wiesenfeld 2017);

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to quinolone (Apuzzio 1989);

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin (Walters 1990).

For severe PID:

macrolides (azithromycin) compared to tetracycline (doxycycline) (Bevan 2003);

quinolone compared to cephalosporins (Okada 1988; Martens 1993; Fischbach 1994);

nitroimidazole compared to no use of nitroimidazole (Ciraru‐Vigneron 1986; Crombleholme 1986; Crombleholme 1987; Leboeuf 1987; Buisson 1989; Ciraru‐Vigneron 1989; Giraud 1989; Heinonen 1989; Fischbach 1994; Sirayapiwat 2002; Heystek 2009);

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to quinolone (Crombleholme 1989; Thadepalli 1991);

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin (Roy 1985; Sweet 1985; Soper 1988; Martens 1990; Roy 1990; Walters 1990; Landers 1991; Maria 1992; Hemsell 1994; Balbi 1996).

Outcomes

The main outcome was clinical cure, and 5475 women were reported as clinically cured. We defined clinical cure according to the authors' definitions, which ranged from absence of symptoms for 24 hours (Apuzzio 1989), to a 60% or greater reduction in total pain score at day 21 combined with an absence of pelvic discomfort/tenderness, temperature less than 37.8 °C, and white blood cell count less than 10,000/mm3 on day 21 (Aşicioğlu 2013). Most trials used clinical parameters for cure, that is, reduction of fever, and reduction or absence of pain at different time points after treatment. We identified adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment as those related to the suspension of therapeutic regimen.

Excluded studies

We excluded 106 studies. The most common reason for exclusion was that the study did not report a comparison of interest to this review (63 studies). Other common reasons for exclusion were that PID cases were not distinguished from other pelvic infectious conditions (26 studies), the studies were not randomized (15 studies), or were suspected of fraud (two studies) (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

In the updated 2020 version, we analyzed and excluded eight full‐text articles (Figure 1). Two articles were not related to PID (Brittain 2016; Baery 2018); one compared two nitroimidazoles (morinidazole and ornidazole) for treating PID (Cao 2017); one used a Tibetan drug with non‐inflammatory activity (Honghua Ruyi Wan) with moxifloxacin compared to moxifloxacin plus placebo (Zhang 2017); one compared two quinolones (levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin) (Zou 2019), which it is not a comparison we wanted; and three used traditional Chinese medicine (Kangfu, an anti‐inflammatory drug (NCT04035785), gynaecological Qianjin with levofloxacin and metronidazole versus levofloxacin and metronidazole (NCT04031664), and Fuyanshu capsules (Feng 2019)). We extracted data from the full‐text article for each study (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

Risk of bias in included studies

We performed a full risk of bias assessment on all included studies. We classified those studies where authors stated that women were randomized to one of two treatments, without further details, as at unclear risk of selection bias. Twenty‐seven studies occurred before 1996, and predated the introduction of CONSORT guidelines, so many studies had unclear risk of bias.

We summarized the risk of bias in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Additional details of the included trials are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Fourteen trials adequately reported a truly random process of sequence generation, for example, random number table or computer random number generator, making selection bias at entry unlikely (Sweet 1985; Soper 1988; Martens 1990; Walters 1990; Thadepalli 1991; Martens 1993; Sirayapiwat 2002; Malhotra 2003; Ross 2006; Savaris 2007; Judlin 2010b; Aşicioğlu 2013; Dean 2016; Wiesenfeld 2017). The remaining included trials did not report the random sequence generation methods, making the risk of selection bias at entry unclear.

For allocation concealment, four trials implemented sequentially numbered drug containers as a concealment allocation method, making selection bias at entry unlikely (Ross 2006; Savaris 2007; Judlin 2010b; Aşicioğlu 2013). The remaining included trials did not report the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment, making the risk of selection bias at entry unclear.

Blinding

Seven trials used placebo with an identical appearance for the control group to blind trial participants and personnel, making performance and detection bias unlikely (Figure 2) (Okada 1988; Arredondo 1997; Ross 2006; Savaris 2007; Heystek 2009; Judlin 2010b; Wiesenfeld 2017). Twelve studies did not blind investigators and participants to the allocation, making them at high risk of bias (Crombleholme 1986; Crombleholme 1989; Walters 1990; Landers 1991; Wendel 1991; Maria 1992; Hemsell 1994; Bevan 2003; Malhotra 2003; Aşicioğlu 2013; Dean 2016; Tison 1988). The remaining included trials did not specify how the participants and the personnel were blinded from knowledge of which intervention a participant received, making the risk of performance and detection bias unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Completeness of data was adequate (i.e. less than 20% of data missing) for 32 of the studies (Figure 2) (Roy 1985; Sweet 1985; Crombleholme 1986; Crombleholme 1987; Leboeuf 1987; Okada 1988; Soper 1988; Apuzzio 1989; Buisson 1989; Ciraru‐Vigneron 1989; Crombleholme 1989; Giraud 1989; Heinonen 1989; Martens 1990; Roy 1990; Walters 1990; Landers 1991; Thadepalli 1991; Hoyme 1993; Martens 1993; Fischbach 1994; Hemsell 1994; Balbi 1996; Sirayapiwat 2002; Bevan 2003; Malhotra 2003; Ross 2006; Savaris 2007; Heystek 2009; Judlin 2010b; Aşicioğlu 2013; Wiesenfeld 2017).

Four studies were unclear about the risk of attrition bias (Ciraru‐Vigneron 1986; Burchell 1987; Tison 1988; Arredondo 1997)

The remaining studies had more than 20% of data missing, with an associated high risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

The trial protocol was available for five studies, and it was clear that the published reports included all the expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified, making reporting bias unlikely (Ross 2006; Savaris 2007; Aşicioğlu 2013; Dean 2016; Wiesenfeld 2017). For the remaining studies, trial protocol was unavailable, and it was unclear whether the published reports included all the expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified. The reports had insufficient information to permit judgment of 'yes' or 'no' and were, therefore, at unclear risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

One study had imbalances in baseline characteristics and was at high risk of potential bias (Soper 1988). Out of 39 trials, 13 had some form of funding by pharmaceutical companies (Crombleholme 1989; Roy 1990; Walters 1990; Landers 1991; Thadepalli 1991; Wendel 1991; Martens 1993; Hemsell 1994; Arredondo 1997; Ross 2006; Savaris 2007; Heystek 2009; Judlin 2010b); however, there is no clear evidence that trial methods are more likely to be flawed if a trial is industry‐funded (Sterne 2013), therefore these trials were at unclear risk. The remaining trials provided insufficient information to permit a judgement of 'yes' or 'no' and were, therefore, at unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings 1. Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) compared to regimens containing tetracycline (doxycycline) for pelvic inflammatory disease.

| Azithromycin compared to doxycycline for PID | |||||||

|

Population: women with PID Setting: hospital ward or outpatient clinic Intervention: regimens containing azithromycin Comparison: regimens containing doxycycline | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Risk with doxycycline | Risk with azithromycin | ||||||

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: median 14 days |

689 per 1000 | 818 per 1000 (740 to 876) |

RR 1.18 (0.89 to 1.55) |

243 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | NNTB 13 NNTH 3 |

|

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study author Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: median 14 days Sensitivity analysis restricted to study at low risk of bias |

627 per 1000 | 848 per 1000 (743 to 921) |

RR 1.35 (1.10 to 1.67) |

133 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderated | NNTB 5 (3 to 14) | |

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Severe PID Follow‐up: range 13–18 days |

969 per 1000 | 971 per 1000 (940 to 987) |

RR 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) |

309 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | NNTB 16 NNTH 29 |

|

|

Adverse events: any antibiotic‐related adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy Follow‐up: range 13–18 days |

78 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (30 to 76) |

RR 0.71 (0.38 to 1.34) |

552 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | NNTB 13 NNTH 101 |

|

| Microbiological clearance | C trachomatis | 980 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (900 to 1000) |

RR 1.02 (0.98 to 1.06) |

243 (2 RCTs) | — | NNTB 10 NNTH 8 |

| N gonorrhoeae | 1000 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (741 to 1000) |

RR 1.0 (0.76 to 1.31) |

309 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,e | Just 1 RCT found cases of N gonorrhoeae | |

| Laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion | No studies reported. | ||||||

| Length of stay (for inpatient care) | Reported results are not sufficient for analysis. | ||||||

| Fertility outcome | No studies reported. | ||||||

| * The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias (poor reporting of methods and high risk of performance and detection bias in one or more studies). bDowngraded one level for serious inconsistency (I2 = 72%). cDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups. dDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: single study with only 98 events. eDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: single unblinded study with poor reporting of methods.

Summary of findings 2. Regimens containing quinolone compared to regimens containing cephalosporins for pelvic inflammatory disease.

| Quinolone compared to cephalosporins for PID | |||||||

|

Population: women with PID Setting: hospital ward or outpatient clinic Intervention: quinolone Comparison: cephalosporins | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Risk with cephalosporins | Risk with quinolone | ||||||

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: range 14–28 days |

691 per 1000 | 719 per 1000 (677 to 760) |

RR 1.05 (0.98 to 1.14) |

772 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | NNTB 9 NNTH 64 |

|

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Severe PID Follow‐up: range 14–28 days |

643 per 1000 | 700 per 1000 (622 to 766) |

RR 1.06 (0.91 to 1.23) |

313 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | NNTB 7 NNTH 15 |

|

|

Adverse events: any antibiotic‐related adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy Follow‐up: mean 14 days |

5 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (5 to 29) |

RR 2.24 (0.52 to 9.72) |

1085 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | 2/6 RCTs (502 women) did not contribute to this analysis because the authors reported 0 events. NNTB 40 NNTH 129 |

|

| Microbiological clearance | C trachomatis | 1000 per 1000 | 952 per 1000 (773 to 992) | RR 0.95 (0.84 to 1.08) | 270 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c |

NNTB 4 NNTH 11 |

| N gonorrhoeae | 952 per 1000 | 900 per 1000 (744 to 965) | RR 1.13 (0.89 to 1.42) | 270 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c |

NNTB 23 NNTH 9 |

|

| Laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion | No studies reported. | ||||||

| Length of stay (for inpatient care) | Reported results are not sufficient for analysis. | ||||||

| Fertility outcome | No studies reported. | ||||||

| * The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias (poor reporting of methods and high or unclear risk of performance and detection bias in one or more studies). bDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups. cDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups, only seven events overall.

Summary of findings 3. Regimens containing nitroimidazole compared to no nitroimidazole for pelvic inflammatory disease.

| Nitroimidazole compared to regimens without use of nitroimidazole for PID | |||||||

|

Population: women with PID Setting: hospital ward or outpatient clinic Intervention: regimens containing nitroimidazole Comparison: regimens containing no nitroimidazole | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Risk with no nitroimidazole | Risk with nitroimidazole | ||||||

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: range 14–28 days |

766 per 1000 | 781 per 1000 (727 to 834) |

RR 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) |

2660 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,b | NNTB 19 NNTH 91 |

|

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: range 14–28 days Sensitivity analysis restricted to studies at low risk of bias |

755 per 1000 | 800 per 1000 (740 to 868) |

RR 1.05 (1.00 to 1.12) |

1434 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

NNTB 19 NNTH 91 |

|

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by study authors Severe PID Follow‐up: range 14–28 days |

832 per 1000 | 804 per 1000 (772 to 831) |

RR 0.96 (0.92 to 1.01) |

1383 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | NNTB 15 NNTH 76 |

|

|

Adverse events: any antibiotic‐related adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy Follow‐up: mean 14 days |

20 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (13 to 32) |

RR 1.05 (0.69 to 1.61) |

4021 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | 10/17 studies (1088 women) did not contribute data to the analysis because the authors reported no events. NNTB 108 NNTH 121 |

|

| Microbiological clearance | C trachomatis | Not applicable, nitroimidazoles have no activity against chlamydia. | |||||

| N gonorrhoeae | Not applicable, nitroimidazoles have no activity against gonorrhoea. | ||||||

| Laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion | No studies reported. | ||||||

| Length of stay (for inpatient care) | Reported results were insufficient for analysis. | ||||||

| Fertility outcome | No studies reported any fertility outcomes. | ||||||

| * The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias (poor reporting of methods and high or unclear risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting bias in one or more studies). bSubstantial inconsistency (I2 = 50%). Not downgraded because of all inconsistency related to a single small study (30 women) which barely influenced the overall estimate. cDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups, only 79 events overall.

Summary of findings 4. Regimens containing clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to regimens containing quinolone for pelvic inflammatory disease.

| Clindamycin + aminoglycoside compared to quinolone for PID | |||||||

|

Population: women with PID Setting: hospital ward or outpatient clinic Intervention: regimens containing clindamycin + aminoglycoside Comparison: regimens containing quinolone | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Risk with quinolone | Risk with clindamycin + aminoglycoside | ||||||

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by authors Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: median 14 days |

1000 per 1000 | 867 per 1000 (621 to 962) |

RR 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) |

25 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | NNTB 3 NNTH 6 |

|

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by authors Severe PID Follow‐up: median 14 days |

800 per 1000 | 816 per 1000 (714 to 887) |

RR 1.02 (0.87 to 1.19) |

151 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | NNTB 7 NNTH 9 |

|

|

Adverse events: any antibiotic‐related adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy Follow‐up: mean 14 days |

50 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 44) |

RR 0.21 (0.02 to 1.72) |

163 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | 1/3 RCTs (25 women) did not contribute data to the analysis because the authors reported 0 events. NNTB 8 NNTH 273 |

|

| Microbiological clearance | C trachomatis | 800 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (722 to 1000) | RR 1.08 (0.85 to 1.36) | 176 (3 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b |

NNTB 3 NNTH 5 |

| N gonorrhoeae | 1000 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (920 to 1000) | RR 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 176 (3 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b |

— | |

| Laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion | No data available. | ||||||

| Length of stay (for inpatient care) | Reported results are not sufficient for analysis. | ||||||

| Fertility outcome | No data available. | ||||||

| * The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded two levels for very serious risk of bias: single unblinded study with poor reporting of methods. bDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision (though further downgrading not possible): confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups, very few events overall. cDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias (poor reporting of methods and high or unclear risk of performance and detection bias in both studies). dDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups.

Summary of findings 5. Regimens containing clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to regimens containing cephalosporin for pelvic inflammatory disease.

| Clindamycin + aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin for PID | |||||||

|

Population: women with PID Setting: hospital ward or outpatient clinic Intervention: regimens containing clindamycin + aminoglycoside Comparison: regimens containing cephalosporin | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of women (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Risk with cephalosporin | Risk with clindamycin + aminoglycoside | ||||||

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by authors Mild‐moderate PID Follow‐up: median 14 days |

958 per 1000 | 974 per 1000 (911 to 993) |

RR 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) |

150 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | NNTB 11 NNTH 19 |

|

|

Clinical cure according to criteria established by authors Severe PID Follow‐up: median 14 days |

840 per 1000 | 838 per 1000 (801 to 870) |

RR 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) |

959 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | NNTB 21 NNTH 22 |

|

|

Adverse events: any antibiotic‐related adverse event leading to discontinuation of therapy Follow‐up: mean 14 days |

4 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (2 to 17) | RR 0.78 (0.18 to 3.42) | 1172 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | 7/10 RCTs (617 women) did not contribute data to the analysis reported because the authors reported no events. NNTB 75 NNTH 126 |

|

| Microbiological clearance | C trachomatis | 946 per 1000 | 962 per 1000 (893 to 987) | RR 1.02 (0.94 to 1.1) | 327 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | NNTB 9 NNTH 16 |

| N gonorrhoeae | 983 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (962 to 1000) | RR 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 327 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c |

NNTB 17 NNTH 43 |

|

| Laparoscopic evidence of resolution of PID based on physician opinion | No data available. | ||||||

| Length of stay (for inpatient care) | Reported results are not sufficient for analysis. | ||||||

| Fertility outcome | No data available. | ||||||

| * The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the mean risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95 CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias (poor reporting of methods and high or unclear risk of performance and detection bias in one or more studies). bDowngraded one level for serious imprecision, small overall sample size. cDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision (though further downgrading not possible): confidence intervals compatible with benefit in one or both groups, or with no difference between the groups, only six events overall.

We analyzed the effectiveness of clinical cure and adverse effects leading to discontinuation of treatment in five scenarios based on drug class:

macrolides (azithromycin) compared to tetracycline (doxycycline);

quinolone compared to cephalosporins;

nitroimidazole compared to no nitroimidazole;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to quinolone;

clindamycin plus aminoglycoside compared to cephalosporin.

We analyzed the efficacy of therapy in these five comparisons in women with mild‐moderate PID and women with severe PID. We also compared adverse events leading to discontinuation of the therapy. Lack of further analysis is discussed in the Differences between protocol and review section.

1. Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) compared to regimens containing tetracycline (doxycycline)

Three studies compared azithromycin versus doxycycline in mild‐moderate (Malhotra 2003; Savaris 2007) or severe (Bevan 2003) PID.

Primary outcomes

1.1. Effectiveness

1.1a. Clinical cure in mild‐moderate pelvic inflammatory disease

We included two trials in the analysis of clinical cure in mild‐moderate PID (Malhotra 2003; Savaris 2007). We are uncertain whether there was a clinically relevant difference between azithromycin and doxycycline in rates of cure for mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.55; 2 studies, 243 women; I2 = 72%; very low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), Outcome 1: Effectiveness of cure in mild‐moderate PID

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), outcome: 1.1 Effectiveness of cure in mild‐moderate PID.

This suggests that if the rate of clinical cure in women with mild‐moderate PID using regimens including doxycycline was 69%, the rate using regimens including azithromycin would be 74% to 88%.

In a sensitivity analysis limited to the study at low risk of bias, azithromycin probably improves the rates of cure in mild‐moderate PID (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.67; 1 study, 133 women; moderate‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 5).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis by risk of bias: effectiveness of cure in mild‐moderate PID

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), outcome: 1.2 Sensitivity analysis by risk of bias: effectiveness of cure in mild‐moderate PID.

The evidence derived from this sensitivity analysis suggests that in mild‐moderate PID, if the rate of clinical cure in women using regimens including doxycycline was 63%, the rate using regimens including azithromycin would be 74% to 92%.

1.1b. Clinical cure in severe pelvic inflammatory disease

One trial reported clinical cure in severe PID (Bevan 2003). The analysis may result in little or no difference between azithromycin and doxycycline in rates of severe PID (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05; 1 study, 309 women; low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 6).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), Outcome 3: Effectiveness of cure in severe PID

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), outcome: 1.3 Effectiveness of cure in severe PID.

This suggests that if clinical cure in severe PID in women using regimens including doxycycline was 97%, the rate using regimens including azithromycin would be 94% to 99%.

1.2. Adverse events

1.2.1. Antibiotic‐related adverse effects leading to discontinuation of therapy

We included three trials in the analysis of antibiotic‐related adverse effects leading to discontinuation of therapy (Bevan 2003; Malhotra 2003; Savaris 2007). We are uncertain of a clinically relevant difference between azithromycin and doxycycline in rates of discontinuation between the groups (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.34; 3 studies, 552 women; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Regimens containing macrolides (azithromycin) versus tetracycline (doxycycline), Outcome 4: Any antibiotic‐related adverse effect leading to discontinuation use of macrolide versus tetracycline

This suggests that if the rate of adverse events in women using regimens including doxycycline was 8%, the rate using regimens including azithromycin would be 3% to 8%.

Data are depicted in Table 1.

Secondary outcomes

1.3. Microbiological clearance of chlamydia

Two studies reported chlamydia clearance (Bevan 2003; Savaris 2007). Cure was obtained in 49/50 women in the azithromycin group (98%, 95% CI 89% to 100%) and 33/33 women in the doxycycline group (100%, 95% CI 90% to 100%).

This suggests that if the rate of microbiological clearance of C trachomatis in women using regimens including doxycycline was 98%, the rate using regimens including azithromycin would be 90% to 100%.

1.4. Microbiological clearance of gonorrhoea