Arthritogenic alphaviruses, including Ross River virus (RRV), are human pathogens that cause debilitating acute and chronic musculoskeletal disease and are a significant public health burden. Using an attenuated RRV with enhanced susceptibility to host innate immune responses has revealed key cellular and molecular mechanisms that can mediate control of attenuated RRV infection and that are evaded by more virulent RRV strains.

KEYWORDS: MAVS, alphavirus, interferon, pDCs

ABSTRACT

Ross River virus (RRV) is a mosquito-borne alphavirus that causes epidemics of debilitating musculoskeletal disease. To define the innate immune mechanisms that mediate control of RRV infection, we studied a RRV strain encoding 6 nonsynonymous mutations in nsP1 (RRV-T48-nsP16M) that is attenuated in wild-type (WT) mice and Rag1−/− mice, which are unable to mount adaptive immune responses, but not in mice that lack the capacity to respond to type I interferon (IFN) (Ifnar1−/− mice). Utilizing this attenuated strain, our prior studies revealed that mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS)-dependent production of type I IFN by Ly6Chi monocytes is critical for control of acute RRV infection. Here, we infected Mavs−/− mice with either WT RRV or RRV-T48-nsP16M to elucidate MAVS-independent protective mechanisms. Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV developed severe disease and succumbed to infection, whereas those infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M exhibited minimal disease signs. Mavs−/− mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M had higher levels of systemic type I IFN than Mavs−/− mice infected with WT virus, and treatment of Mavs−/− mice infected with the attenuated nsP1 mutant virus with an IFNAR1-blocking antibody resulted in a lethal infection. In vitro, type I IFN expression was induced in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) cocultured with RRV-infected cells in a MAVS-independent manner, and depletion of pDCs in Mavs−/− mice resulted in increased viral burdens in joint and muscle tissues, suggesting that pDCs are a source of the protective IFN in Mavs−/− mice. These data suggest that pDC production of type I IFN through a MAVS-independent pathway contributes to control of RRV infection.

IMPORTANCE Arthritogenic alphaviruses, including Ross River virus (RRV), are human pathogens that cause debilitating acute and chronic musculoskeletal disease and are a significant public health burden. Using an attenuated RRV with enhanced susceptibility to host innate immune responses has revealed key cellular and molecular mechanisms that can mediate control of attenuated RRV infection and that are evaded by more virulent RRV strains. In this study, we found that pDCs contribute to the protective type I interferon response during RRV infection through a mechanism that is independent of the mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) adaptor protein. These findings highlight a key innate immune mechanism that contributes to control of alphavirus infections.

INTRODUCTION

The type I interferon (IFN) response is essential for control of alphavirus infection, and mice deficient in the transcription factors required for production of type I IFN (e.g., Irf3−/− Irf7−/− double-knockout mice) or those deficient in the type I IFN receptor (Ifnar1−/− mice) succumb rapidly to infection with these viruses (1–6). In response to RNA virus infections, there are two canonical pathways by which type I IFN is produced in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs): Toll-like receptor (TLR) and RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) signaling. Typically, specific features of the viral RNAs produced during infection are recognized by these pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). TLR3 and TLR7, which recognize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), respectively, are localized within endosomal compartments and recognize RNA ligands to drive type I IFN and proinflammatory gene expression through the adaptor proteins TRIF (TLR3) and MyD88 (TLR7) (7, 8). Downstream of TLR3 and TRIF, IRF3 (and IRF7 once upregulated and expressed) becomes phosphorylated, allowing it to translocate into the nucleus, where it promotes transcription of type I IFN genes (7, 8). Although induction of type I IFN gene transcription does not typically occur downstream of MyD88, MyD88-dependent signaling through TLR7 or TLR9 in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) can lead to phosphorylation of IRF7 and induction of type I IFN gene expression (7, 8). The RLRs, which include RIG-I and MDA5, recognize specific motifs within viral RNAs, including uncapped 5′ triphosphate RNA and long dsRNA, respectively, although it is likely that these PRRs also respond to other RNA motifs (8, 9). The RLRs drive type I IFN induction through the mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) adaptor protein (9). Similar to signaling downstream of TLR3 and TRIF, signaling downstream of RIG-I or MDA5 and MAVS leads to phosphorylation of IRF3 (and later IRF7), allowing induction of type I IFN gene expression (8).

TLR and RLR signaling contributes to protective responses during arthritogenic alphavirus infection. In mice, TLR7 and MyD88 signaling was found to be protective during both Ross River virus (RRV) (10) and chikungunya virus (CHIKV) (4) infection. In addition, TLR3 and TRIF are important for control of CHIKV infection in mice (4, 11). While some studies suggest that TLRs mediate enhanced control of alphavirus infection via a type I IFN-dependent mechanism (4), others have demonstrated a role for TLR signaling in the development of a potent neutralizing-antibody response, which may or may not be dependent on type I IFN production downstream of TLRs (10, 11).

RLRs also contribute to the immune response to arthritogenic alphavirus infection. MAVS has been demonstrated to play an essential role for controlling disease severity during CHIKV infection (1, 3, 4, 12). Infection of MAVS-deficient mice revealed that a MAVS-dependent signaling pathway is the primary source of serum type I IFN in CHIKV-infected mice (4) and that deficiency in MAVS results in more severe disease, including increased joint swelling and viremia (4) and mortality in neonatal mice (3). In vitro, infection in both mouse (1) and human (12) fibroblasts revealed that nonhematopoietic cells respond to CHIKV infection by production of type I IFN in a MAVS-dependent manner. Both RIG-I and MDA5 appear to be able to recognize alphavirus infection (13), as knockdown of both receptors, but not either receptor alone, completely abrogated IFN-β production from alphavirus-infected fibroblasts in vitro, suggesting they may both contribute to MAVS-dependent production of type I IFN during these infections. Some studies also have suggested cooperative redundancy between RLR and TLR signaling pathways during alphavirus infections (4), highlighting the difficulty in defining distinct functions for these pathways due to overlap and the ability to compensate when one pathway is disrupted.

In previous studies, we found that Ly6Chi monocytes produced type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells via a MAVS-dependent mechanism (14). We also found, using bone marrow chimeras in Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice, that monocytes are important type I IFN producers that contribute to the rescue of Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice from lethal RRV infection (14), suggesting an important role for MAVS-mediated type I IFN production by Ly6Chi monocytes for control of acute alphavirus infection. However, these experiments suggested that IFN production by other hematopoietic cells also contributes to control of alphavirus infection, as RRV infection was less severe in Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice reconstituted with wild-type (WT) bone marrow and depleted of monocytes than in Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice reconstituted with Irf3−/− Irf7−/− bone marrow (14). As such, we hypothesized that a MAVS-independent pathway functions in other hematopoietic cell types to drive type I IFN production that contributes to the rescue of Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice from lethal RRV infection.

To investigate this idea, we assessed viral burden and disease severity in Mavs−/− mice infected with either WT RRV or a previously characterized nsP1 mutant virus (RRV-T48-nsP16M) that has enhanced sensitivity to type I IFN (6, 14, 15). Consistent with our previous studies (14), Mavs−/− mice infected with either WT RRV or the nsP1 mutant virus had similar viral burdens in a variety of tissues until 5 days postinfection. Beyond 5 days postinfection, however, the two infections diverged, with Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV developing more severe disease signs and ultimately succumbing to infection, whereas those infected with the nsP1 mutant virus exhibited minimal disease signs and improved virus control. The improved control of the nsP1 mutant virus was not altered in T cell-depleted Mavs−/− mice or associated with differences in neutralizing antibody levels. In addition, depletion of monocytes in Mavs−/− mice infected with the nsP1 mutant virus also had no impact on disease severity, consistent with a MAVS-dependent role for monocytes in protection against RRV infection (14). Instead, Mavs−/− mice infected with the nsP1 mutant virus had higher levels of type I IFN than Mavs−/− mice infected with the WT virus, and treatment of Mavs−/− mice infected with the attenuated nsP1 mutant virus with an IFNAR1 blocking antibody resulted in a lethal infection. To identify the cells that protect against RRV infection by a MAVS-independent mechanism, we assessed whether pDCs induce type I IFN expression in response to RRV-infected cells. Using an in vitro coculture system in which pDCs were cultured in the presence of RRV-infected cells revealed that type I IFN expression is induced in pDCs in a MAVS-independent manner. Moreover, depletion of pDCs in Mavs−/− mice infected with the nsP1 mutant virus resulted in increased viral burden in joint and muscle tissues, suggesting that pDCs are a source of the protective IFN in Mavs−/− mice. Together, these data suggest that pDC production of type I IFN through a MAVS-independent pathway can contribute to control of RRV infection and that determinants in nsP1 counteract MAVS-dependent and MAVS-independent type I IFN responses.

RESULTS

MAVS-deficient mice succumb to WT RRV infection but not infection with an attenuated nsP1 mutant virus.

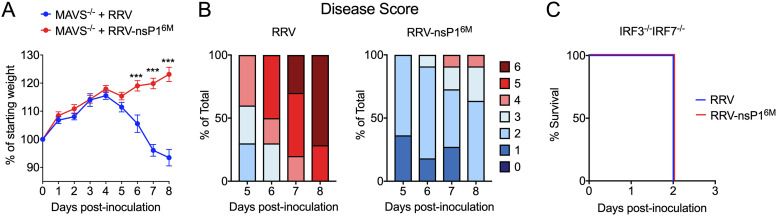

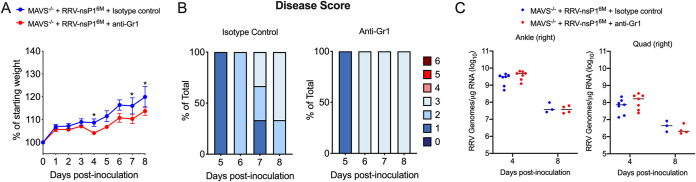

In previous studies, we found that viral burdens of WT RRV and an attenuated nsP1 mutant virus (RRV-T48-nsP16M) were equivalent in the muscle tissue of Mavs−/− mice at 5 days postinfection (dpi) (14). To investigate whether viral burdens remained equivalent at later time points, we infected Mavs−/− mice with WT RRV or RRV-T48-nsP16M and monitored the mice beyond 5 dpi. From 5 to 8 dpi, Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV lost weight (Fig. 1A) and exhibited more severe disease signs (Fig. 1B), while mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M continued to gain weight and displayed mild disease signs (Fig. 1A and B). Due to the development of severe disease signs, Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV were humanely euthanized by 8 dpi (Fig. 1B). In contrast, Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice infected with either virus succumbed rapidly to the infection (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that, in addition to the MAVS-dependent monocyte-mediated control of RRV-nsP16M (14), there also is a MAVS-independent, IRF3/IRF7-dependent antiviral mechanism that is subverted by determinants in nsP1.

FIG 1.

Disease severity in RRV-infected MAVS-deficient mice. (A and B) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (10 or 11/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48 or RRV-T48-nsP16M. Mice were monitored daily for weight changes (A) and disease signs (B). (C) Irf3−/− Irf7−/− C57BL/6 mice (9/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48 or RRV-T48-nsP16M. Mice were monitored for survival. Data are from 2 or 3 independent experiments. P values were determined by an unpaired t test. ***, P < 0.001.

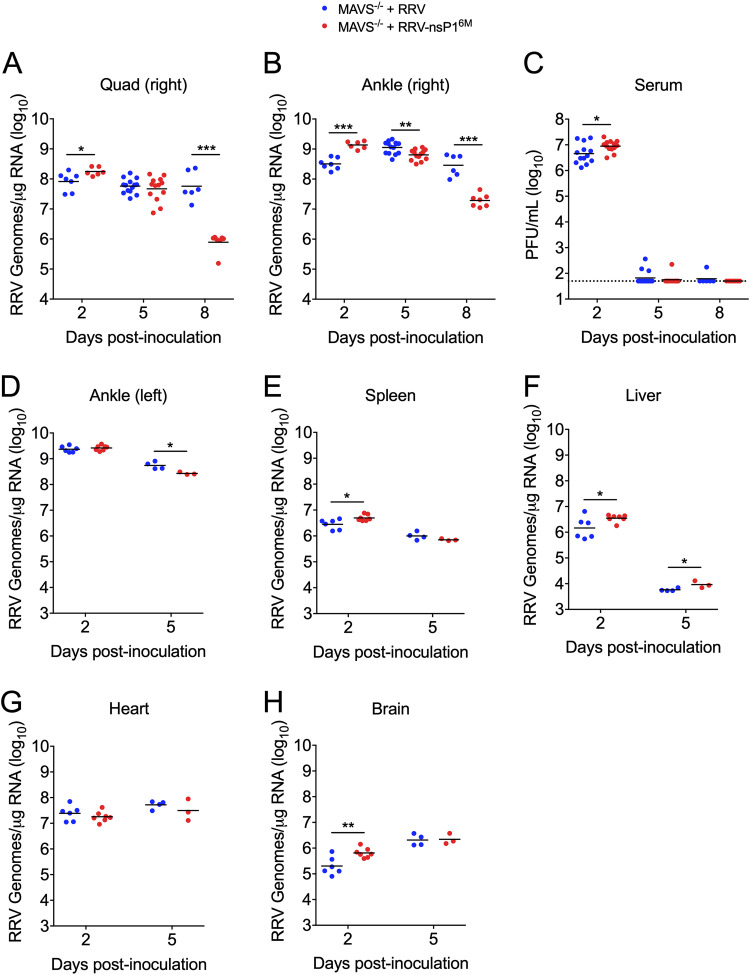

We next infected Mavs−/− mice with WT RRV and RRV-T48-nsP16M and assessed viral burden by RT-qPCR or plaque assay in various tissues at days 2, 5, and 8 p.i. Viral burdens in muscle and joint tissue, as well as serum, at 2 and 5 dpi were largely equivalent, with RRV-T48-nsP16M achieving a slightly higher burden than WT RRV at 2 dpi (Fig. 2A to C). This was also true for other tissues evaluated, including the left ankle, spleen, brain, heart, and liver (Fig. 2D to H). While there was little difference in tissue viral burden at these early time points, by 8 dpi, the time by which MAVS-deficient mice infected with WT RRV succumbed to infection (Fig. 1B), viral burdens were higher in the muscle (74-fold; P < 0.001) and right ankle (15-fold; P < 0.001) tissue of mice infected with WT RRV (Fig. 2A and B). Furthermore, this difference appeared to be due to enhanced control of RRV-T48-nsP16M infection, as viral burdens in these tissues were largely equivalent at 5 and 8 dpi in mice infected with WT RRV, whereas viral burdens were decreased in these tissues at 8 dpi in mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M (Fig. 2A and B). This failure to control WT RRV, however, did not impact resolution of viremia, as both viruses were mostly undetectable in the serum by 5 dpi (Fig. 2C). Together, these data further support the idea that a MAVS-independent mechanism can control RRV-T48-nsP16M infection and that WT RRV is less susceptible to this antiviral mechanism.

FIG 2.

WT RRV is not efficiently controlled in MAVS-deficient mice. (A to C) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (6 to 14/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48 or RRV-T48-nsP16M. Tissues and serum were collected at 2, 5, and 8 dpi, and viral burdens were determined by RT-qPCR (A and B) or plaque assay (C). Data are from 2 to 4 independent experiments per time point. P values were determined by an unpaired t test. (D to H) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (3 to 6/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48 or RRV-T48-nsP16M. Tissues were collected at 2 and 5 dpi, and viral RNA in the tissue was quantified by RT-qPCR. Data are from 1 independent experiment per time point. P values were determined by an unpaired t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Enhanced control of RRV-nsP16M in MAVS-deficient mice is not due to adaptive immunity.

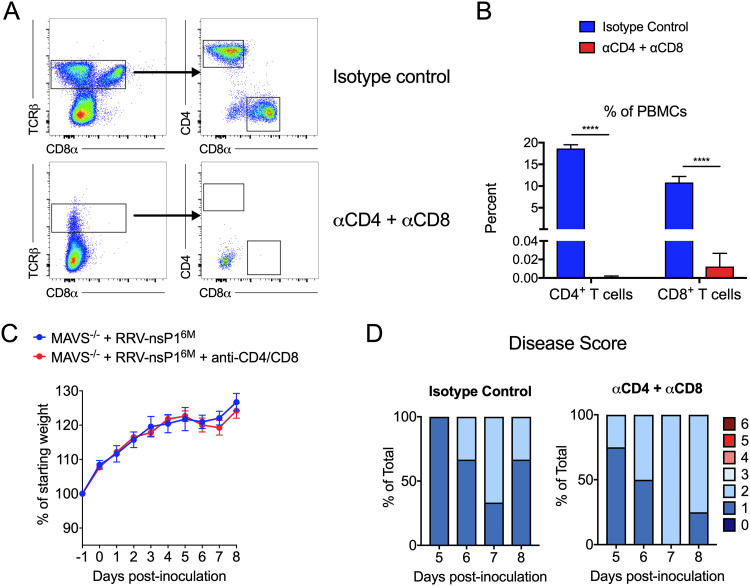

Given the timing of the divergence in disease severity between WT RRV and RRV-T48-nsP16M infection in Mavs−/− mice (Fig. 1A), we hypothesized that adaptive immune responses are impaired in Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV. As an initial test of this idea, we infected Mavs−/− mice with RRV-nsP16M and treated mice with a combination of anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies or equivalent amounts of an isotype control antibody on day −1 and day 3 postinfection (p.i.). Mice were then monitored for weight gain and disease signs for 8 days. While depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was effective (Fig. 3A and B), depletion of T cells did not affect either weight gain (Fig. 3C) or the development of disease signs (Fig. 3D), suggesting that T cells are not the primary mediator of protection against RRV-T48-nsP16M infection in the absence of MAVS.

FIG 3.

T cell depletion does not result in increased disease severity in RRV-nsP16M-infected MAVS-deficient mice. (A to D) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (3 or 4/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48-nsP16M. Mice were treated at day −1 and day +3 p.i. with either anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies or isotype control antibody. Blood was collected at day 8 to assess depletion by flow cytometry (A and B). Mice were monitored daily for weight changes (C) and disease signs (D). Data are from 1 independent experiment. P values were determined by an unpaired t test. ****, P < 0.0001.

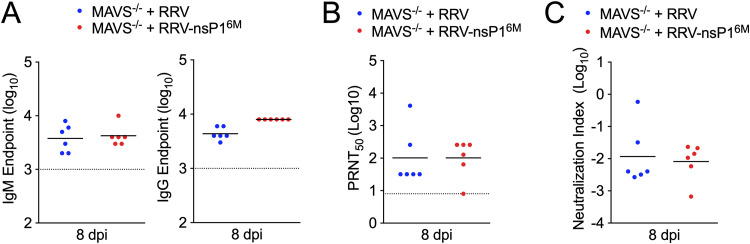

We next sought to determine whether the neutralizing capacity of RRV-specific antibodies was reduced in Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV relative to those infected with RRV-nsP16M, as studies have previously shown neutralizing antibody responses were diminished in these mice during West Nile virus infection despite more robust antibody production (16). We collected serum from Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV and RRV-T48-nsP16M at 8 dpi and measured total RRV-specific IgM and IgG by a virion-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 4A). In addition, the neutralization capacity of the antibodies in serum at this time point was assessed by plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT), and PRNT50 values (the reciprocal of the last dilution at which the percent infectivity was <50%) were determined (Fig. 4B). PRNT50 values and IgM and IgG endpoints were then used to calculate a neutralization index for each serum sample (16, 17). We found no significant differences in the neutralization index of serum samples from mice infected with either WT RRV or RRV-T48-nsP16M (Fig. 4C), suggesting that dysregulated neutralizing-antibody responses are not responsible for the altered outcomes of infection in Mavs−/− mice between these two viruses. Together, these results suggest that the MAVS-independent control of RRV-T48-nsP16M infection is not due to adaptive immune responses and, rather, is likely due to an aspect of the innate immune response.

FIG 4.

Neutralizing antibody responses are equivalent in MAVS-deficient mice. (A to C) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (6/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48 or RRV-T48-nsP16M. Serum was collected at 8 dpi, and total RRV-specific IgM and IgG were measured by ELISA (A). Serum neutralization capacity was measured by PRNT, and PRNT50 values were determined (B). PRNT50 values and IgM and IgG endpoints were used to calculate the neutralization index (C). Data are from 2 independent experiments. P values were determined by unpaired t test. P > 0.05.

Enhanced control of RRV-nsP16M in MAVS-deficient mice is not due to a MAVS-independent compensatory mechanism in monocytes.

As our previous studies identified an important MAVS-dependent antiviral role for monocytes (14), we next determined whether this MAVS-independent mechanism might also be monocyte-mediated. To address this question, we treated Mavs−/− mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M with either anti-Gr1 or an isotype control antibody on day −1 and day 3 p.i., following our well-established protocols for monocyte depletion (14, 18). Mice were weighed and monitored for disease signs daily, and tissues were collected at 4 and 8 dpi for assessing tissue viral burden by RT-qPCR. While mice treated with the anti-Gr1 antibody showed modestly diminished weight gain relative to control antibody-treated mice (Fig. 5A), anti-Gr1 antibody-treated mice exhibited no evidence of severe morbidity or mortality (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, anti-Gr-1 antibody treatment did not alter viral loads in either muscle or ankle tissue (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that Gr1+ cells (e.g., monocytes and neutrophils) are not responsible for the MAVS-independent mechanism that controls RRV-nsP16M infection.

FIG 5.

Treatment with anti-Gr1 antibody does not result in increased disease severity in RRV-nsP16M-infected MAVS-deficient mice. (A to C) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (3 to 7/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48-nsP16M. Mice were treated at day −1 and day +3 p.i. with either anti-Gr1 or isotype control antibody. Weight (A) and disease score (B) were monitored daily. Viral RNA was quantified in tissue by RT-qPCR at 4 and 8 dpi (C). Data are from 2 independent experiments (4 dpi) or 1 experiment (8 dpi). P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction (A) or unpaired t test (B). *, P < 0.05.

RRV-nsP16M infection induced higher serum IFN-α levels in MAVS-deficient mice, and type I IFN signaling in MAVS-deficient mice is required for protection from severe infection.

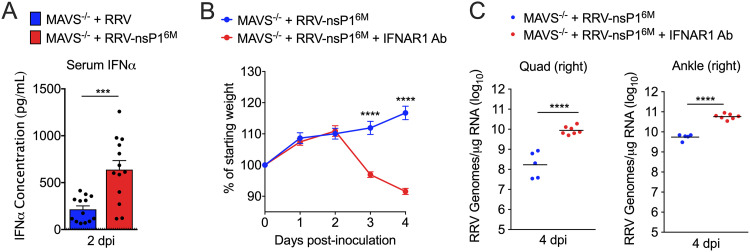

Next, we sought to determine whether the distinct outcomes following infection of Mavs−/− mice with WT RRV or the nsP1 mutant were due to differences in type I IFN production, specifically type I IFN produced downstream of an alternative pathway to MAVS, such as TLR signaling. At 2 dpi, the time point of peak type I IFN levels in the serum of RRV-infected mice (6), we measured IFN-α levels in the serum of RRV-infected Mavs−/− mice by multiplex assay. Mavs−/− mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M exhibited 5-fold-higher levels of serum IFN-α at this time point (Fig. 6A). Based on this result, we hypothesized that RRV-T48-nsP16M infection drives type I IFN production by a pathway typically evaded by WT RRV and/or that the modestly increased viral loads in mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M at this time point (Fig. 2A) promote increased type I IFN production. Either of these effects, combined with our findings demonstrating that RRV-nsP16M is more sensitive to type I IFN (6), led us to further hypothesize that this increase in type I IFN drives the disparate outcomes of infection between these two viruses in MAVS-deficient mice.

FIG 6.

Blockade of type I IFN signaling results in increased disease severity in RRV-nsP16M-infected MAVS-deficient mice. (A) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (13/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48 or RRV-T48-nsP16M. Serum was collected at 2 dpi and analyzed for IFN-α expression by LEGENDPlex. Data are from 3 independent experiments. P values were determined by an unpaired t test. (B and C) Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice (5 to 7/group) were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48-nsP16M. Mice were treated at day +1 p.i. with either anti-IFNAR1 or isotype control antibody. Weight was monitored daily (B), and viral RNA was quantified in tissue by RT-qPCR at 4 dpi (C). Data are from 2 independent experiments. P values were determined by multiple t tests with Holm-Šidák corrections (B) or an unpaired t test (C). ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

To evaluate the extent to which type I IFN is the primary driver of improved control of RRV-T48-nsP16M infection in Mavs−/− mice, we tested whether blocking type I IFN signaling in Mavs−/− mice would increase disease severity following RRV-T48-nsP16M infection. Mavs−/− mice were infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M and then treated with either an anti-IFNAR1 antibody or isotype control antibody at day 1 p.i. Mice treated with the anti-IFNAR1 antibody exhibited more severe disease signs, including weight loss (Fig. 6B), and succumbed to infection by 4 dpi, suggesting that type I IFN protects Mavs−/− mice from severe RRV-T48-nsP16M infection. Mice treated with the anti-IFNAR1 antibody also had elevated viral burdens in muscle (51-fold; P, <0.0001) and ankle joint (10.5-fold; P, <0.0001) compared with control mice (Fig. 6C). These findings demonstrate that type I IFN is produced in response to RRV-T48-nsP16M through a MAVS-independent pathway and that this IFN protects Mavs−/− mice from succumbing to RRV-T48-nsP16M infection.

pDCs produce type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells by a MAVS-independent pathway.

We next sought to identify the cell type responsible for the MAVS-independent type I IFN production in response to RRV-T48-nsP16M. pDCs are known to produce large amounts of type I IFN in response to viral infection (19, 20). While pDCs express RIG-I and MDA5, pDCs are relatively resistant to viral infection, and these cytosolic sensors are unlikely to encounter viral RNA and signal through MAVS. Instead, pDC production of type I IFN in response to viral infection is largely driven by the endosomal sensors TLR7 and TLR9, which respond to ssRNA and dsDNA, respectively (19, 20). pDCs can sense viruses through physical contact with infected cells, creating an interferogenic synapse that allows efficient transfer of viral PAMPs such as RNA to pDCs (21).

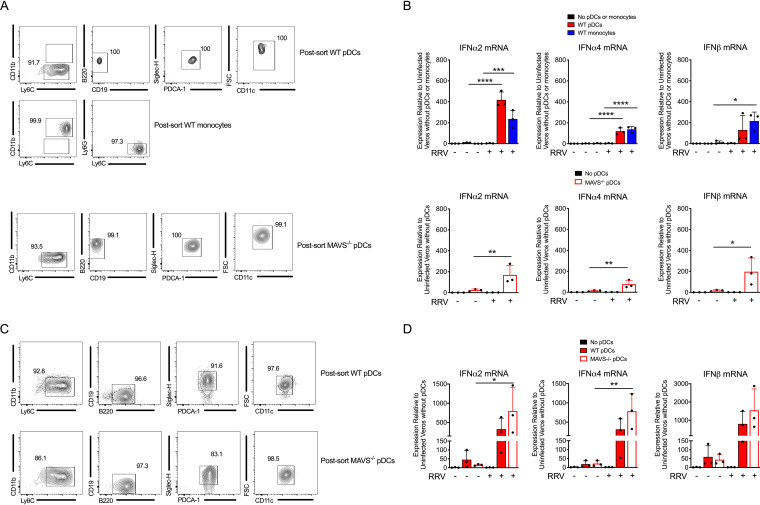

To investigate whether pDCs induce type I IFN expression in response to RRV-infected cells, we established a coculture system using RRV-infected Vero cells, which lack type I IFN genes, and pDCs or monocytes sorted from the bone marrow and spleens of WT or Mavs−/− mice. Sorted monocytes were included as a positive control for type I IFN induction based on our previous studies using this coculture system (14). Postsorting purity of monocytes and pDCs was determined using the gating strategy shown in Fig. 7A. Little or no type I IFN upregulation was detected in the absence of RRV infection or in infected Vero cells alone (Fig. 7B). However, when RRV-infected Vero cells were cocultured with sorted WT pDCs or monocytes, type I IFN transcript was readily detected in the cell lysates (Fig. 7B), demonstrating that pDCs can produce type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells. To evaluate whether pDC type I IFN production was dependent on MAVS, pDCs sorted from Mavs−/− mice were cocultured with RRV-infected Vero cells. The level of type I IFN produced by Mavs−/− pDCs was similar to that observed from WT pDCs (Fig. 7B), demonstrating that pDCs produce type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells through a MAVS-independent pathway. We confirmed these results using pDCs that had been differentiated in vitro from bone marrow cells cultured with Flt3L and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 7C). Again, both WT and Mavs−/− in vitro differentiated pDCs expressed similar levels of type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells (Fig. 7D), further demonstrating that induction of type I IFN in pDCs in response to RRV occurs independently of MAVS.

FIG 7.

pDCs produce type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells by a MAVS-independent pathway. (A) pDCs or monocytes were sorted from pooled WT splenocytes and bone marrow cells (top), and pDCs were sorted from pooled Mavs−/− splenocytes and bone marrow cells (bottom) using a FACSAria sorter. Monocytes were defined as Ly6C+ CD11b+ Ly6G− cells. pDCs were defined as Ly6C+ CD11b− B220+ CD19− PDCA-1+ Siglec-H+ CD11c+. The post-sorting fraction of cells is displayed. (B) pDCs or monocytes were FACS sorted as described for panel A and cocultured with uninfected Vero cells (−) or RRV-infected Vero cells (+) for 18 h. Expression of IFN-α2, IFN-α4, and IFN-β was evaluated by RT-qPCR. (C) WT and Mavs−/− bone marrow cells were cultured in vitro with Flt3L for 9 days. Differentiated pDCs were sorted using a FACSAria sorter as described for panel A. The post-sorting fraction of cells is displayed. (D) WT and Mavs−/− bone marrow cells were cultured in vitro with Flt3 for 9 days. Differentiated pDCs were FACS sorted, cocultured with Vero cells, and evaluated as in panel B. Data are from 1 independent experiment. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

pDCs protect Mavs−/− mice from RRV infection.

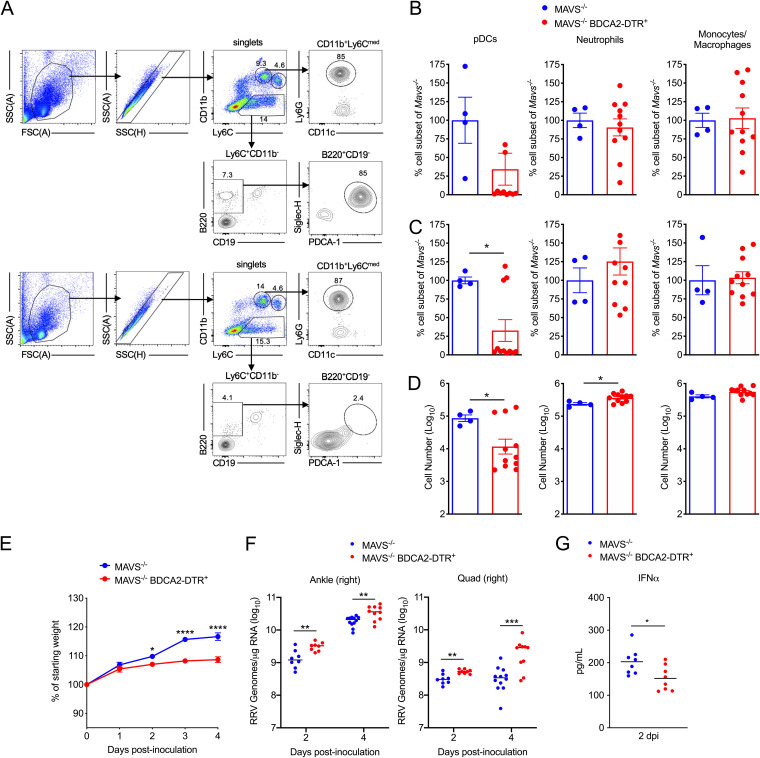

Given that pDCs respond to RRV-infected cells through a MAVS-independent pathway, we hypothesized that pDCs were protective against RRV-T48-nsP16M infection in Mavs−/− mice. To test this idea, we crossed Mavs−/− mice with BDCA2-DTR+ mice, which express the diphtheria toxin receptor under the control of BDCA2, a highly specific pDC gene promoter (22). Administration of diphtheria toxin (DT) to BDCA2-DTR+ mice resulted in selective depletion of pDCs by 24 h after DT treatment (Fig. 8A to D), and prior studies indicate that depletion persists for at least 48 h (22). Thus, Mavs−/− (control) or Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice were treated with DT 24 h prior to infection with RRV-T48-nsP16M and 1 day after infection to maintain pDC depletion. Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice infected with RRV-T48-nsP16M had a modest decrease in weight gain compared with Mavs−/− mice (Fig. 8E). In addition, significantly elevated viral tissue burdens were observed in Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice as early as 2 days postinfection in the contralateral right ankle (2.1-fold; P, <0.01) and right quadriceps (1.6-fold; P, <0.01), and this elevation persisted at 4 days postinfection (right ankle, 1.8-fold [P, <0.01]; right quadriceps, 5.5-fold [P, <0.001]) (Fig. 8F). Despite the increased viral burdens, Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice had significantly lower IFN-α in the serum at 2 days postinfection than Mavs−/− mice (Fig. 8G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that in the absence of MAVS, type I IFN production by pDCs contributes to control of RRV-T48-nsP16M infection.

FIG 8.

Depletion of pDCs causes more severe disease and increased viral burdens in RRV-nsP16M-infected MAVS-deficient mice. (A to C) Mavs−/− or Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ C57BL/6 mice (4 to 11 per group) were treated with DT, and 24 h after treatment, the percentages of pDCs, neutrophils, and monocytes were analyzed in the blood and spleen by flow cytometry. (A) Representative flow plots from blood of Mavs−/− (top) or Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ (bottom) are shown (the same gating strategy was used for spleens). The frequency of pDCs, neutrophils, and monocytes in Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice as a percentage of the respective cell subset in Mavs−/− mice was determined for the blood (B) and spleen (C). In addition, the number of cells in each cell subset was determined for the spleen (D). (E to G) Mavs−/− or Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ C57BL/6 mice (8 to 12 mice/group) were treated with DT on days −1 and +1 to deplete pDCs and inoculated on day 0 in the left rear footpad with 1,000 PFU of RRV-T48-nsP16M. Weight was monitored daily (E), and viral RNA was quantified in tissue by RT-qPCR at 2 and 4 dpi (F). IFN-α levels in the serum at 2 dpi were quantified using an MSD U-PLEX ELISA (G). Data are from 2 independent experiments. P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s corrections (E) or an unpaired t test (B, C, D, F, and G). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P 001; ****, P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, we found that mutations in the nsP1 gene render RRV more sensitive to monocyte-mediated control through a type I IFN-dependent mechanism (14). We also found that type I IFN production in monocytes in response to RRV is dependent on MAVS in vitro and that MAVS is required for the decreased viral loads in tissues of RRV-T48-nsP16M-infected WT mice at 5 dpi (14). In this study, we describe a MAVS-independent mechanism that can control RRV-T48-nsP16M infection. We found that this mechanism is independent of adaptive immune responses, as it does not require T cells and is not associated with better neutralizing antibody responses to RRV-T48-nsP16M in Mavs−/− mice.

Instead, we found that MAVS-independent control of RRV-T48-nsP16M is dependent on type I IFN, as Mavs−/− mice treated with an anti-IFNAR1 antibody succumbed to RRV-nsP16M infection. The fact that these mice succumbed more rapidly than Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV is likely due to the fact that Mavs−/− mice infected with WT RRV still produce some type I IFN. We also found that RRV-T48-nsP16M infection elicits increased type I IFN production relative to WT RRV in the absence of MAVS. This could be due to the modest increase in early viral burdens in tissues that we detected in RRV-T48-nsP16M-infected Mavs−/− mice and/or the activation of distinct pathways by RRV-T48-nsP16M infection that are either not activated or more efficiently evaded by WT RRV. Regardless, these findings reveal that there is a MAVS-independent source of type I IFN that is activated in mice during RRV infection.

Plasmacytoid DCs are potent producers of type I IFN through TLR7- and TLR9-mediated signaling in the context of many different infections (19, 20). Our in vitro coculture experiments demonstrated that pDCs produce type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells through a MAVS-independent pathway. These data are consistent with published findings indicating that pDCs produce type I IFN in response to CHIKV-infected cells in a TLR7-dependent, MAVS-independent manner (23). Moreover, we found that depletion of pDCs in Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice resulted in elevated burdens of RRV-T48-nsP16M in joint and muscle tissue. Despite elevated viral burdens, Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice had lower type I IFN in the serum, consistent with pDCs being a source of protective type I IFN in response to RRV-T48-nsP16M infection. In contrast to treatment of Mavs−/− mice with the anti-IFNAR1 antibody, depletion of pDCs in Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice did not result in severe weight loss following RRV-T48-nsP16M infection. This may be due to incomplete depletion of pDCs in Mavs−/− BDCA2-DTR+ mice (Fig. 8C and D) or additional cellular sources of type I IFN. In addition, pDCs may function in a more localized manner to control RRV-nsP16M, while administration of IFNAR1 blocking antibody would act broadly and have more systemic effects.

Bone marrow reconstitution experiments and experiments in mice lacking IFNAR1 on hematopoietic cells demonstrated that nonhematopoietic cells, such as fibroblasts, need to respond to type I IFN to prevent severe disease during arthritogenic alphavirus infection (1, 24). However, the important cellular sources of type I IFN during infection with these viruses are less clear. In prior studies, we found that Ly6Chi monocytes produce type I IFN in response to RRV-infected cells in a Mavs−/−-dependent manner (14). Moreover, bone marrow reconstitution experiments in Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice revealed that monocytes are important type I IFN producers that contribute to the rescue of Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice from lethal RRV infection (14). These data implicated Ly6Chi monocytes as one important cellular source of type I IFN. In this study, we identified a MAVS-independent protective role for pDC-mediated type I IFN production during RRV infection. These findings are consistent with other recent studies demonstrating that pDCs are an important cellular source of type I IFN during CHIKV and Mayaro virus (MAYV) infection. In one study, lethal CHIKV infection of Irf3−/− Irf7−/− mice was reversed with genetically enforced expression of IRF7 in pDCs, and this effect was dependent on IFNAR1 signaling (23). More recently, perturbation of the intestinal microbiome revealed that TLR7-MyD88-dependent production of type I IFN by pDCs limits CHIKV and MAYV viremia and dissemination (25). Collectively, these studies suggest that MAVS-dependent and TLR7/MyD88-dependent type I IFN production by hematopoietic cells, including Ly6Chi monocytes and pDCs, respectively, is critical to limit viral replication and disease caused by arthritogenic alphaviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

The T48 strain of RRV (GenBank accession no. GQ433359) was isolated from Aedes vigilax mosquitoes in Queensland, Australia (26). Prior to cDNA cloning, the virus was passaged 10 times in suckling mice, followed by two passages on Vero cells (27, 28). RRV strain DC5692 (GenBank accession no. HM234643), from which the attenuating mutations in nsP1 were derived (6, 15), was isolated in 1995 from Aedes camptorhynchus mosquitoes at Dawesville Cut in the Peel region of Western Australia (29). The virus was passaged once in C6/36 cells, once in Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81), and once in BHK-21 [C-13] (ATCC CCL-10) cells prior to cDNA cloning (15). RRV-T48-nsP16M contains the six nonsynonymous DC5692 nucleotides in the nsP1 gene (6). Plasmids encoding infectious cDNA clones of RRV have been described (6, 15, 27, 30). Virus stocks were prepared from cDNA clones as previously described (30, 31). Briefly, plasmids were linearized and used as a template for in vitro transcription with SP6 DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Ambion). RNA transcripts were electroporated into BHK-21 cells, and at 24 h postelectroporation, cell culture supernatant was collected and clarified by centrifugation at 1,721 × g. Clarified supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Viral titers were determined by plaque assay using BHK-21 as described elsewhere (30, 32).

Mouse experiments, disease scoring, and depletion strategies.

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (33) and the American Veterinary Medical Association’s AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (34). All animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado School of Medicine (assurance number A3269-01) under protocols 00026 and 00215. Experimental animals were humanely euthanized at defined endpoints by exposure to isoflurane vapors followed by bilateral thoracotomy. Mice were bred in specific-pathogen-free facilities at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. All mouse studies were performed in an animal biosafety level 2 laboratory. WT and BDCA2-DTR+ (22) C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Mavs−/− C57BL/6 mice, originally generated at the University of Washington (35), were provided by Kenneth Tyler (University of Colorado School of Medicine). Irf3−/− Irf7−/− C57BL/6 mice were provided by Michael S. Diamond (Washington University). Three- to four-week-old mice were used for all studies unless otherwise specified.

Mice were inoculated in the left rear footpad with 103 PFU of virus in diluent (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum [FBS]). Mock-infected animals received diluent alone. Disease scores of RRV-infected mice were determined by assessing grip strength, hind limb weakness, and altered gait, as previously described (31). Briefly, grip strength and hind limb weakness were assessed by testing the ability of each mouse to grip a rounded surface. Mice were scored as follows: 0, no disease signs; 1, extremely mild defect in injected hind paw gripping ability; 2, very mild defect in bilateral hind paw gripping ability; 3, bilateral loss of gripping ability and mild bilateral hind limb paresis; 4, bilateral loss of gripping ability, moderate bilateral hind limb paresis, observable altered gait, and difficulty or failure to right self; 5, bilateral loss of gripping ability, severe bilateral hind limb paresis, altered gait with hind paw dragging, and failure to right self; 6, bilateral loss of gripping ability, very severe hind limb paresis with dragging of limbs, and failure to right self. On the day of experiment termination, mice were sedated with isoflurane and euthanized by bilateral thoracotomy, blood was collected, and mice were perfused by intracardiac injection of 1× PBS. PBS-perfused tissues were removed by dissection and homogenized in TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies) for RNA isolation using a MagNA Lyser (Roche).

For IFNAR1 blockade, mice were injected with 500 μg/mouse of anti-IFNAR1 (clone MAR1-5A3; BioXcell) or isotype control antibody. For T cell depletion experiments, mice were injected with 200 μg/mouse of anti-CD4 (clone YTS 191; BioXcell) and 200 μg/mouse of anti-CD8 (clone YTS 169.4; BioXcell) or 400 μg/mouse of isotype control antibody on days −1 and +3 postinfection. For monocyte depletion experiments, mice were treated with 300 μg/mouse of anti-Gr1 (clone RB6-8C5; BioXcell) or isotype control antibody on day −1 and +3 postinfection. For BDCA2-DTR+ experiments, mice were treated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 100 ng of diphtheria toxin (DT) 24 h prior to virus inoculation and again 24 h after virus inoculation.

Quantification of viral RNA.

RNA was isolated from TRIzol-homogenized tissues using a PureLink RNA minikit (Life Technologies). Absolute quantification of RRV RNA was performed using 500 ng to 1 μg RNA as previously described (36). A sequence-tagged (in lowercase letters) RRV-specific RT primer (RRV nucleotide 4415, 5′-ggcagtatcgtgaattcgatgcAACACTCCCGTCGACAACAGA-3′) was used for reverse transcription. A tag sequence-specific reverse primer (5′-GGCAGTATCGTGAATTCGATGC-3′) was used with a RRV sequence-specific forward primer (RRV nucleotide 4346, 5′-CCGTGGCGGGTATTATCAAT-3′) and an internal TaqMan probe (RRV nucleotide 4375, 5′-ATTAAGAGTGTAGCCATCC-3′) during qPCR to enhance specificity. To create standard curves, 10-fold dilutions, from 108 to 102 copies, of RRV genomic RNAs synthesized in vitro were spiked into RNA from BHK-21 cells, and reverse transcription and qPCR were performed in an identical manner. The limit of detection was 100 genome copies.

Plaque assays.

Virus-containing samples were serially diluted 10-fold, and dilutions were adsorbed onto BHK-21 monolayers for 1 h at 37°C. Monolayers were then overlaid with medium containing 0.5% immunodiffusion agarose and incubated at 37°C for 36 to 40 h. Plaques were visualized using neutral red staining and enumerated to determine the virus concentration (PFU per milliliter) in each sample.

Flow cytometry.

Peripheral blood was collected in 100 mM EDTA, and red blood cells were lysed using BD PharmLyse buffer (BD Biosciences). Spleens were dissected from mice and passed through a 100-μm cell strainer. Following red blood cell lysis, cells were washed in 1× PBS and passed through a 70-μm strainer, and total viable cells were determined by trypan blue exclusion. Isolated leukocytes from all samples were incubated with anti-mouse FcγRII/III (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) for 20 min on ice to block nonspecific antibody binding and then stained in FACS buffer (1× PBS, 2% FBS) with the following antibodies (Abs) (BioLegend): anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-F4/80 (BM8), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-CD43 (1B11), anti-CD64 (X54-5/7.1), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-NK1.1 (PK136), anti-CD45 (30-F11), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8α (53-6.7), and anti-T cell receptor β (TCR-β) (H57-597). For evaluation of pDC depletion, the following antibodies were used: anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD317 (PDCA-1) (927), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), anti-Siglec H (551), anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-CD11c (N418), and anti-CD19 (6D5). Cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer using FACSDiva software (Becton Dickinson). Further analysis was done using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Monocyte and pDC isolation and coculture.

Vero cells were plated in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well the day prior to infection (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1 PFU/cell). Monocytes and pDCs were sorted by FACS from pooled splenocytes and bone marrow cells. Tissues were processed as described above. Prior to sorting, a presorting removal of B cells, T cells, and NK cells was performed by staining with anti-TCR-β conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) (H57-597), anti-CD19–PE (6D5), and anti-NK1.1–PE (PK136) and using anti-PE selection beads (Miltenyi) to selectively deplete antibody-bound cells. Isolated leukocytes were incubated with anti-mouse FcγRII/III (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) for 20 min on ice to block nonspecific antibody binding and then stained in FACS buffer (1× PBS, 2% FBS) with the following antibodies (BioLegend): anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-CD19 (6D5), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CD317 (PDCA-1) (927), anti-Siglec-H (551), and anti-CD11c (N418). SYTOX orange dead cell stain (Invitrogen) was added immediately prior to sorting according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells were then analyzed and sorted on a FACSAria sorter using FACSDiva software (Becton Dickinson). Monocytes were sorted based on expression of Ly6C and CD11b and the absence of Ly6G. pDCs were defined as Ly6C+ CD11b− B220+ CD19− PDCA-1+ Siglec-H+ CD11c+. Postsorting purity was assessed by flow cytometry on an LSRFortessa instrument using FACSDiva software (Becton Dickinson). In a subset of experiments, in vitro-differentiated pDCs were sorted from bone marrow cells and cultured with 200 ng/ml Flt3L for 9 days. After differentiation, cells were collected, stained as described above, and sorted using a FACSAria instrument. Enriched monocytes and pDCs were plated with Vero cells at a density of 5 × 104 to 1 × 105 cells per well immediately postsorting. Cocultures were harvested 18 h after plating of the monocytes and/or pDCs for analysis. Cells were harvested either in TRIzol reagent for RNA isolation and RT-qPCR analysis or collected for staining and flow cytometry analysis.

Host gene RT-qPCR.

RNA was isolated from cells collected in TRIzol reagent using the PureLink RNA minikit (Life Technologies). Random primers (Life Technologies) were used to generate random-primed cDNA, which was then subjected to qPCR analysis using TaqMan primer/probe sets specific for 18S rRNA, murine IFN-α2, IFN-β, IFN-α4, or Irf7 (Applied Biosystems). IFN-α2, IFN-β, IFN-α4, or Irf7 expression was normalized to 18S values to control for input amounts of cDNA. The relative fold induction of amplified mRNA was determined using the cycle threshold (CT) method (37).

Plaque reduction neutralization test.

Serum neutralization activity was assessed by plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). Serum samples were heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min, then serially diluted, and incubated with 50 PFU of virus for 1 h at 37°C. Following incubation, remaining nonneutralized virus was measured by plaque assay on Vero cells. PRNT50 values were defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution at which the percent infectivity was <50%. These PRNT50 values were then used with IgM and IgG endpoints, as measured by ELISA (described below), to determine the neutralization index. The neutralization index is defined as the PRNT50 value divided by the sum of the reciprocal of the IgM and IgG endpoints (17).

RRV-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

RRV-specific total IgM and total IgG in serum was measured using a virion-based ELISA (17). Serum samples were serially diluted and added to a 96-well Immulon 4HBX plate (Thermo Scientific) with adsorbed concentrated RRV particles. Bound antibody was detected using biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM or IgG antibodies (Southern Biotech), followed by streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Southern Biotech), and a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) liquid substrate (Sigma). Endpoint titers were defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution to have an absorbance two times greater than background. Blank wells receiving no serum were used to quantify background signal. IgM and IgG endpoints were then used to calculate the neutralization index, as described above.

Quantification of serum IFN-α.

IFN-α levels in the serum of mice were measured by the LEGENDPlex multiplex cytokine assay (BioLegend) (Fig. 5) or by the U-PLEX Interferon Combo 1 (ms) assay (Mesoscale Discovery) (Fig. 8). Both assays were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Concentrations of IFN-α, in picograms per milliliter, were determined using the supplied standard for the assay.

Statistical analysis.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Data were evaluated for statistically significant differences using a two-tailed unpaired t test, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, or a two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni multiple-comparison test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All differences not specifically indicated to be significant were not significant (P > 0.05).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Public Health Service grants R01 AI108725 and R01 AI141436 (T.E.M.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. K.C.H. was supported by Public Health Service grants T32 AI052066 and F31 AI122517 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. K.S.C. was supported by Public Health Service grants T32 AI007405 and F32 AI140567 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schilte C, Couderc T, Chretien F, Sourisseau M, Gangneux N, Guivel-Benhassine F, Kraxner A, Tschopp J, Higgs S, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Colonna M, Peduto L, Schwartz O, Lecuit M, Albert ML. 2010. Type I IFN controls chikungunya virus via its action on nonhematopoietic cells. J Exp Med 207:429–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner CL, Burke CW, Higgs ST, Klimstra WB, Ryman KD. 2012. Interferon-alpha/beta deficiency greatly exacerbates arthritogenic disease in mice infected with wild-type chikungunya virus but not with the cell culture-adapted live-attenuated 181/25 vaccine candidate. Virology 425:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schilte C, Buckwalter MR, Laird ME, Diamond MS, Schwartz O, Albert ML. 2012. Cutting edge: independent roles for IRF-3 and IRF-7 in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells during host response to chikungunya infection. J Immunol 188:2967–2971. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd PA, Wilson J, Gardner J, Larcher T, Babarit C, Le TT, Anraku I, Kumagai Y, Loo YM, Gale M, Akira S, Khromykh AA, Suhrbier A. 2012. Interferon response factors 3 and 7 protect against chikungunya virus hemorrhagic fever and shock. J Virol 86:9888–9898. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00956-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couderc T, Chretien F, Schilte C, Disson O, Brigitte M, Guivel-Benhassine F, Touret Y, Barau G, Cayet N, Schuffenecker I, Desprès P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Michault A, Albert ML, Lecuit M. 2008. A mouse model for Chikungunya: young age and inefficient type-I interferon signaling are risk factors for severe disease. PLoS Pathog 4:e29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoermer Burrack KA, Hawman DW, Jupille HJ, Oko L, Minor M, Shives KD, Gunn BM, Long KM, Morrison TE. 2014. Attenuating mutations in nsP1 reveal tissue-specific mechanisms for control of Ross River virus infection. J Virol 88:3719–3732. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02609-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, Akira S. 2010. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol 11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen S, Thomsen AR. 2012. Sensing of RNA viruses: a review of innate immune receptors involved in recognizing RNA virus invasion. J Virol 86:2900–2910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05738-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loo Y-M, Gale M. 2011. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity 34:680–692. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neighbours LM, Long K, Whitmore AC, Heise MT. 2012. Myd88-dependent Toll-like receptor 7 signaling mediates protection from severe Ross River virus-induced disease in mice. J Virol 86:10675–10685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00601-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Her Z, Teng T-S, Tan JJ, Teo T-H, Kam Y-W, Lum F-M, Lee WW, Gabriel C, Melchiotti R, Andiappan AK, Lulla V, Lulla A, Win MK, Chow A, Biswas SK, Leo Y-S, Lecuit M, Merits A, Rénia L, Ng LF. 2015. Loss of TLR3 aggravates CHIKV replication and pathology due to an altered virus-specific neutralizing antibody response. EMBO Mol Med 7:24–41. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White LK, Sali T, Alvarado D, Gatti E, Pierre P, Streblow D, Defilippis VR. 2011. Chikungunya virus induces IPS-1-dependent innate immune activation and protein kinase R-independent translational shutoff. J Virol 85:606–620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00767-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhrymuk I, Frolov I, Frolova EI. 2016. Both RIG-I and MDA5 detect alphavirus replication in concentration-dependent mode. Virology 487:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haist KC, Burrack KS, Davenport BJ, Morrison TE. 2017. Inflammatory monocytes mediate control of acute alphavirus infection in mice. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006748. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jupille HJ, Oko L, Stoermer KA, Heise MT, Mahalingam S, Gunn BM, Morrison TE. 2011. Mutations in nsP1 and PE2 are critical determinants of Ross River virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease in a mouse model. Virology 410:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suthar MS, Ma DY, Thomas S, Lund JM, Zhang N, Daffis S, Rudensky AY, Bevan MJ, Clark EA, Kaja MK, Diamond MS, Gale M. 2010. IPS-1 is essential for the control of west nile virus infection and immunity. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000757. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawman DW, Fox JM, Ashbrook AW, Dermody TS, Diamond MS, May NA, Schroeder KMS, Torres RM, Crowe JE, Morrison TE. 2016. Pathogenic chikungunya virus evades B cell responses to establish persistence. Cell Rep 16:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy MK, Reynoso GV, Winkler ES, Mack M, Diamond MS, Hickman HD, Morrison TE. 2020. MyD88-dependent influx of monocytes and neutrophils impairs lymph node B cell responses to chikungunya virus infection via Irf5, Nos2 and Nox2. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008292. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swiecki M, Colonna M. 2015. The multifaceted biology of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol 15:471–485. doi: 10.1038/nri3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swiecki M, Colonna M. 2010. Unraveling the functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells during viral infections, autoimmunity, and tolerance. Immunol Rev 234:142–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assil S, Coléon S, Dong C, Décembre E, Sherry L, Allatif O, Webster B, Dreux M. 2019. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and infected cells form an interferogenic synapse required for antiviral responses. Cell Host Microbe 25:730–745.E6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swiecki M, Gilfillan S, Vermi W, Wang Y, Colonna M. 2010. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell ablation impacts early interferon responses and antiviral NK and CD8(+) T cell accrual. Immunity 33:955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster B, Werneke SW, Zafirova B, This S, Coléon S, Décembre E, Paidassi H, Bouvier I, Joubert P-E, Duffy D, Walzer T, Albert ML, Dreux M. 2018. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control dengue and Chikungunya virus infections via IRF7-regulated interferon responses. Elife 7:e34273. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook LE, Locke MC, Young AR, Monte K, Hedberg ML, Shimak RM, Sheehan KCF, Veis DJ, Diamond MS, Lenschow DJ. 2019. Distinct roles of interferon alpha and beta in controlling chikungunya virus replication and modulating neutrophil-mediated inflammation. J Virol 94:1–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00841-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkler ES, Shrihari S, Hykes BL, Handley SA, Andhey PS, Huang Y-JS, Swain A, Droit L, Chebrolu KK, Mack M, Vanlandingham DL, Thackray LB, Cella M, Colonna M, Artyomov MN, Stappenbeck TS, Diamond MS. 2020. The intestinal microbiome restricts alphavirus infection and dissemination through a bile acid-type I IFN signaling axis. Cell 182:901–918.E18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doherty R, Whitehead R, Gorman B, O’Gower A. 1963. The isolation of a third group A arbovirus in Australia, with preliminary observations on its relationship to epidemic polyarthritis. Aust J Sci 26:183–184. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuhn RJ, Niesters HGM, Hong Z, Strauss JH. 1991. Infectious RNA transcripts from Ross River virus cDNA clones and the construction and characterization of defined chimeras with sindbis virus. Virology 182:430–441. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90584-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalgarno L, Rice CM, Strauss JH. 1983. Ross river virus 26 S RNA: complete nucleotide sequence and deduced sequence of the encoded structural proteins. Virology 129:170–187. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsay M, Oliveira N, Jasinska E, Johansen CA, Harrington S, Wright A, Smith DW. 1996. An outbreak of Ross River virus disease in southwestern Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 2:117–120. doi: 10.3201/eid0202.960206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison TE, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Whitmore AC, Lotstein AR, Gunn BM, Elmore SA, Heise MT. 2011. A mouse model of chikungunya virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease: evidence of arthritis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and persistence. Am J Pathol 178:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison TE, Whitmore AC, Shabman RS, Lidbury BA, Mahalingam S, Heise MT. 2006. Characterization of Ross River virus tropism and virus-induced inflammation in a mouse model of viral arthritis and myositis. J Virol 80:737–749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.737-749.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jupille HJ, Medina-Rivera M, Hawman DW, Oko L, Morrison TE. 2013. A tyrosine-to-histidine switch at position 18 of the Ross River virus E2 glycoprotein is a determinant of virus fitness in disparate hosts. J Virol 87:5970–5984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03326-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Veterinary Medical Association. 2020. AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals, 2020 ed. American Veterinary Medical Assocation, Schaumberg, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suthar MS, Ramos HJ, Brassil MM, Netland J, Chappell CP, Blahnik G, McMillan A, Diamond MS, Clark EA, Bevan MJ, Gale M. 2012. The RIG-I-like receptor LGP2 controls CD8+ T cell survival and fitness. Immunity 37:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoermer KA, Burrack A, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Borst LB, Gill RG, Morrison TE. 2012. Genetic ablation of arginase 1 in macrophages and neutrophils enhances clearance of an arthritogenic alphavirus. J Immunol 189:4047–4059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]