Abstract

Background

Changes to the method of payment for healthcare providers, including pay‐for‐performance schemes, are increasingly being used by governments, health insurers, and employers to help align financial incentives with health system goals. In this review we focused on changes to the method and level of payment for all types of healthcare providers in outpatient healthcare settings. Outpatient healthcare settings, broadly defined as 'out of hospital' care including primary care, are important for health systems in reducing the use of more expensive hospital services.

Objectives

To assess the impact of different payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings on the quantity and quality of health service provision, patient outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes, cost of service provision, and adverse effects.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase (searched 5 March 2019), and several other databases. In addition, we searched clinical trials platforms, grey literature, screened reference lists of included studies, did a cited reference search for included studies, and contacted study authors to identify additional studies. We screened records from an updated search in August 2020, with any potentially relevant studies categorised as awaiting classification.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time series, and repeated measures studies that compared different payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient care settings.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We conducted a structured synthesis. We first categorised the payment methods comparisons and outcomes, and then described the effects of different types of payment methods on different outcome categories. Where feasible, we used meta‐analysis to synthesise the effects of payment interventions under the same category. Where it was not possible to perform meta‐analysis, we have reported means/medians and full ranges of the available point estimates. We have reported the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and the relative difference (as per cent change or mean difference (MD)) for continuous outcomes.

Main results

We included 27 studies in the review: 12 randomised trials, 13 controlled before‐and‐after studies, one interrupted time series, and one repeated measure study. Most healthcare providers were primary care physicians. Most of the payment methods were implemented by health insurance schemes in high‐income countries, with only one study from a low‐ or middle‐income country. The included studies were categorised into four groups based on comparisons of different payment methods.

(1) Pay for performance (P4P) plus existing payment methods comparedwith existing payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings

P4P incentives probably improve child immunisation status (RR 1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19 to 1.36; 3760 patients; moderate‐certainty evidence) and may slightly increase the number of patients who are asked more detailed questions on their disease by their pharmacist (MD 1.24, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.54; 454 patients; low‐certainty evidence). P4P may slightly improve primary care physicians' prescribing of guideline‐recommended antihypertensive medicines compared with an existing payment method (RR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.12; 362 patients; low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain about the effects of extra P4P incentives on mean blood pressure reduction for patients and costs for providing services compared with an existing payment method (very low‐certainty evidence). Outcomes related to workload or other health professional outcomes were not reported in the included studies. One randomised trial found that compared to the control group, the performance of incentivised professionals was not sustained after the P4P intervention had ended.

(2) Fee for service (FFS) comparedwith existing payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings

We are uncertain about the effect of FFS on the quantity of health services delivered (outpatient visits and hospitalisations), patient health outcomes, and total drugs cost compared to an existing payment method due to very low‐certainty evidence. The quality of service provision and health professional outcomes were not reported in the included studies. One randomised trial reported that physicians paid via FFS may see more well patients than salaried physicians (low‐certainty evidence), possibly implying that more unnecessary services were delivered through FFS.

(3) FFS mixed with existing payment methods compared with existing payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings

FFS mixed payment method may increase the quantity of health services provided compared with an existing payment method (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.76; low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain about the effect of FFS mixed payment on quality of services provided, patient health outcomes, and health professional outcomes compared with an existing payment method due to very low‐certainty evidence. Cost outcomes and adverse effects were not reported in the included studies.

(4) Enhanced FFS compared with FFS for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings

Enhanced FFS (higher FFS payment) probably increases child immunisation rates (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.48; moderate‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain whether higher FFS payment results in more primary care visits and about the effect of enhanced FFS on the net expenditure per year on covered children with regular FFS (very low‐certainty evidence). Quality of service provision, patient outcomes, health professional outcomes, and adverse effects were not reported in the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

For healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings, P4P or an increase in FFS payment level probably increases the quantity of health service provision (moderate‐certainty evidence), and P4P may slightly improve the quality of service provision for targeted conditions (low‐certainty evidence). The effects of changes in payment methods on health outcomes is uncertain due to very low‐certainty evidence. Information to explore the influence of specific payment method design features, such as the size of incentives and type of performance measures, was insufficient. Furthermore, due to limited and very low‐certainty evidence, it is uncertain if changing payment models without including additional funding for professionals would have similar effects.

There is a need for further well‐conducted research on payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings in low‐ and middle‐income countries; more studies comparing the impacts of different designs of the same payment method; and studies that consider the unintended consequences of payment interventions.

Plain language summary

Payment methods for healthcare providers in outpatient healthcare settings

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to assess the effect of different payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings. The review authors collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found 27 studies.

Key messages

This review suggests that different payment methods can affect healthcare provider behaviour in both positive and negative ways. For instance, whilst healthcare providers may be encouraged to provide more of specific services, they may also be encouraged to provide unnecessary services. Considerable gaps remain in the understanding of how payment of healthcare providers affects healthcare services, healthcare providers’ work morale and workload, and patient health.

What was studied in the review?

Healthcare providers may be paid in different ways. Different payment methods can encourage healthcare providers to give patients the treatment they need in the best and most cost‐efficient way, but they can also encourage healthcare providers to offer poor‐quality, expensive, and unnecessary care, and to avoid certain treatments or certain types of patients. Different payment methods can also influence healthcare providers’ work morale and workload. And they can cost more or less for the healthcare system.

The review authors searched for studies on the effects of different payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient care. Outpatient care is where patients get health care from healthcare providers outside of hospitals and where there is no need for a bed. Healthcare centres, family planning centres, and dental clinics are all examples of outpatient facilities.

The payment methods the review authors were interested in were as follows.

‐ Pay‐for‐performance: healthcare providers are paid for carrying out certain tasks or reaching certain targets.

‐ Fee‐for‐service: healthcare providers are paid for each service they provide to the patient.

‐ Salary: healthcare providers are paid based on the time they spend at work.

‐ Capitation: healthcare providers are paid according to how many patients they have.

‐ A mix of these different approaches.

What are the main results of the review?

The review authors found 27 relevant studies. Most of the studies looked at primary healthcare doctors in high‐income countries.

When pay‐for‐performance plus other payment methods (including capitation, salary, and fee‐for‐service) is compared to other payment methods: healthcare providers probably provide more of certain services, including immunisations. They may also provide better‐quality care, including how some medicines are used, but these improvements may be reduced when the pay‐for‐performance payments end. Effects on patient health may be mixed. We are uncertain about the effect on healthcare providers’ work morale or workload, or on cost, because the evidence is missing or of very low certainty.

When fee‐for‐service methods are compared to other payment methods (such as capitation or salary): healthcare providers paid by fee‐for‐service may provide more unnecessary services than those paid by salary. We are uncertain about the effect on the quality or quantity of care, patient health, healthcare providers’ work morale or workload, or cost because the evidence is missing or of very low certainty.

When fee‐for‐service mixed with other payment methods (including fee‐for‐service plus capitation and fee‐for‐service plus salary) are compared to other payment methods: healthcare providers may provide more of specific services. We are uncertain about the effect on the quality of care, patient health, healthcare providers’ work morale or workload, cost, or unintended effects because the evidence is missing or of very low certainty.

When fee‐for‐service methods using a higher fee are compared to fee‐for‐service methods using a lower fee: healthcare providers probably provide more of certain services, including immunisations. We are uncertain if the higher fee has an impact on cost because the evidence is of very low certainty. We are uncertain about the effect on the quality of care, patient health, healthcare providers’ work morale or workload, or unintended effects because the evidence is missing.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to 5 March 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Pay for performance (P4P) plus existing payment methods compared with existing payment methods for outpatient healthcare providers.

| P4P plus existing payment methods compared with existing payment methods for outpatient healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Patient or population: healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings Settings: Australia, Canada, India, Taiwan, the USA Intervention: P4P plus existing payment methods Comparison: existing payment methods (including capitation, FFS, and salary) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Results in words | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with existing payment methods | Risk with P4P plus existing payment methods | |||||

| Quantity of service provision (dichotomous) ‐ child immunisation status up‐to‐date | 433 up‐to‐date per 1000 children | 550 up‐to‐date per 1000 children (515 to 588 children) | RR 1.27 (1.19 to 1.36) | P4P added to existing payment methods probably increases the number of children with up‐to‐date immunisation status, compared with an existing payment method. | 3760 children (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 |

| Quantity of service provision (continuous) ‐ immunisation rates for patients aged 65 years or older | The mean immunisation rate with P4P plus existing payment methods was 0.34 per cent points higher (0.2 per cent points lower to 0.87 points higher) compared to existing payment methods. | MD 0.34 (−0.20 to 0.87) | We are uncertain of the effect of P4P added to existing payment methods on immunisation rates for the elderly. | 54 primary care practices (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 | |

| Quantity of service provision (continuous) ‐ number of detailed disease‐related consultation services per 100 prescriptions | The mean number of consultation services with P4P plus existing payment methods was 1.24 per cent higher per 100 prescriptions (0.93 per cent points higher to 1.54 points higher) compared to existing payment methods. | MD 1.24 (0.93 to 1.54) | P4P added to existing payment methods may slightly increase the number of patients who are asked more detailed questions on their disease by their pharmacist, compared with an existing payment method. | 200 community pharmacies (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3 | |

| Quality of service provision ‐ physician prescribing practices | Insufficient data to calculate | RR 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) | P4P added to existing payment methods may slightly improve providers' prescribing of guideline‐recommended antihypertensive medicines compared with an existing payment method. | 362 people (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW4 | |

| Patient outcomes ‐ reduction in blood pressure | The mean blood pressure reduction with P4P plus existing payment methods was 0.07 mmHG greater (2.22 less to 2.37 greater) compared to existing payment methods. | MD 0.07 (ranged from −2.22 to 2.37) | We are uncertain of the effect of P4P added to existing payment methods on mean blood pressure reduction compared with an existing payment method. | 181 people (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW5 |

|

| Quality of service provision and patient outcomes ‐ blood pressure management | Insufficient data to calculate | RR 1.13 (1.04 to 1.23) | P4P added to existing payment methods may improve blood pressure control or appropriate responses to patients with uncontrolled blood pressure, compared with an existing payment method. | 362 people (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW6 | |

| Healthcare provider outcomes (such as work morale or workload) | None of the included studies reported on healthcare provider outcomes. | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Costs | We are uncertain of the costs of adding P4P to existing payment methods on expenditures for diabetes‐related services due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 1 CBA | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW7 |

|||

| Unintended or adverse effects | Insufficient data to calculate | RR 0.77 (0.71 to 0.82) | When the P4P intervention ended, there was an important reduction in performance (blood pressure control or appropriate responses to uncontrolled blood pressure) in the intervention group compared with the existing payment method. | 362 people (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW8 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CBA: controlled before‐after study; FFS: fee‐for‐service; MD: mean difference; P4P: pay for performance; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is low.

Moderate certainty: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is moderate.

Low certainty: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different** is high.

Very low certainty: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is very high. ** Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision | ||||||

1We rated two RCTs as unclear risk of bias (Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level because of limitation in study design.

2We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Kouides 1998), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design, one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physicians in the USA), and one level for imprecision (limited number of participants, and 95% CI overlaps no effect).

3We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Christensen 2000), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting community pharmacies in the USA).

4We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Petersen 2013), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physicians in the USA).

5We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Houle 2016), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design, one level for indirectness (only one study targeting pharmacists in pharmacy practice in Canada), and one level for imprecision (study ended prior to enrolment of the full sample size of participants, and 95% CI overlaps no effect).

6We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Petersen 2013), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physicians in the USA).

7We rated one CBA as high risk of bias (Lee 2010). Initial rating of low certainty assigned due to non‐randomised study design and downgraded one level for further limitations in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting pharmacists in community clinics physicians in Taiwan).

8We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Petersen 2013), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physicians in the USA).

Summary of findings 2. Fee‐for‐service (FFS) compared with existing payment methods for outpatient healthcare providers.

| FFS compared with existing payment methods for outpatient healthcare providers | ||||

|

Patient or population: healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings Settings: the USA Intervention: FFS Comparison: existing payment method (input‐based payment ‐ capitation or salary) | ||||

| Outcomes | Impact | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Relative effect (range) | Results in words | |||

| Quantity of service provision ‐ number of outpatients visits, specialist visits, or hospitalisations | Median change = 10.44% (range: −460% to +175.65%) | We are uncertain of the effect of FFS payments on the number of patient visits to health facilities, compared with input‐based payment methods, due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 3 RCTs | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1 |

| Quality of service provision | None of the included studies reported on the quality of services provided. | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Patient outcomes ‐ people with mental illness | Median change = −9.84% (range: −492% to +350%) | We are uncertain of the effect of FFS on patient outcomes for people with mental illness, compared with an input‐based payment method, due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 1 RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

| Healthcare provider outcomes (such as work morale or workload) | None of the included studies reported on healthcare provider outcomes. | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Costs | We are uncertain of the effect of FFS on costs compared with an input‐based payment method (capitation) due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 2 CBAs | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3 |

|

| Unintended or adverse effects | Physicians who receive FFS payments may see more well patients (potentially an indicator of unnecessary service provision) compared with physicians paid by salary. | 1 RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW4 | |

| CBA: controlled before‐after study; FFS: fee‐for‐service; RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is low. Moderate certainty: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is moderate. Low certainty: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different** is high. Very low certainty: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is very high. ** Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision | ||||

1We rated two RCTs as unclear risk of bias, Hickson 1987; Lurie 1992, and one RCT as high risk of bias (Davidson 1992), downgrading the certainty of the evidence two levels for limitation in study design and one level for imprecision.

2We rated one RCT as high risk of bias (Lurie 1992), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design, one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physician for mental health care in the USA), and one level for imprecision.

3We rated two CBAs as unclear risk of bias (Yesalis 1980; Yesalis 1984. Initial rating of low certainty assigned due to non‐randomised study design and downgraded one level for further limitations in study design.

4We rated one RCT as unclear risk of bias (Hickson 1987), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting paediatric residents in the USA).

Summary of findings 3. Fee‐for‐service (FFS) mixed with existing payment methods compared with existing payment method for outpatient healthcare providers.

| FFS mixed with existing payment methods compared with existing payment method for outpatient healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Patient or population: healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings Settings: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the UK Intervention: FFS mixed with other payment methods Comparison: existing payment method (single payment method, including salary, capitation, and FFS) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Impact | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | ||

| Risk with existing payment | Risk with FFS mixed with other payment methods | Relative effect (95% CI) | Results in words | |||

| Quantity of service provision ‐ proportion of women/children receiving treatment | Insufficient data to calculate | RR 1.37 (1.07 to 1.76) | FFS mixed with other payment methods may increase the quantity of health services provided, compared with an existing payment method. | 2 RCTs | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1 | |

| Quality of service provision | We are uncertain of the effect of FFS mixed with other payment methods on the quality of service provided compared with an existing payment method due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 1 CBA | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

|||

| Patient outcomes ‐ satisfaction with care | We are uncertain of the effect of FFS mixed with other payment methods on patient outcomes compared with an existing payment method due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 1 RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3 |

|||

| Healthcare provider outcomes ‐ working hours and income | We are uncertain of the effect of FFS mixed with other payment methods on healthcare provider outcomes compared with an existing payment method due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 2 CBAs | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW4 |

|||

| Costs | None of the included studies reported on costs. | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Unintended or adverse effects | None of the included studies reported on adverse effects. | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CBA: controlled before‐after study; FFS: fee‐for‐service; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is low. Moderate certainty: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is moderate. Low certainty: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different** is high. Very low certainty: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is very high. ** Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision | ||||||

1We rated two RCTs as unclear risk of bias (Bilardi 2010; Clarkson 2008), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitations in study design and one level for imprecision due to very small numbers of participants in both studies.

2We rated one CBA as high risk of bias (Gosden 2003). Initial rating of low certainty assigned due to non‐randomised study design and downgraded one level for further limitations in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting general practitioners in England).

3We rated one RCT as high risk of bias (Twardella 2007), downgrading the certainty of the evidence two levels for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting general practitioners in Germany).

4We rated two CBAs as high risk of bias (Gosden 2003; Gray 2015. Initial rating of low certainty assigned due to non‐randomised study design and downgraded one level for further limitations in study design.

Summary of findings 4. Enhanced fee‐for‐service (FFS) compared with FFS for outpatient healthcare providers.

| Enhanced FFS compared with FFS for outpatient healthcare providers | ||||||

|

Patient or population: healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings Settings: Germany, the USA Intervention: enhanced FFS with higher unit payment levels Comparison: FFS with normal unit payment levels | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Results in words | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with FFS | Risk with Enhanced FFS | |||||

| Quantity of service provision ‐ child immunisation status up‐to‐date | 433 up‐to‐date per 1000 children | 541 up‐to‐date per 1000 children (459 to 640 children) | RR 1.25 (1.06 to 1.48) | Paying higher fees to healthcare providers for immunisations delivered probably increases the proportion of children aged 3 to 35 months whose immunisation is up‐to‐date, compared with the normal level of fees. | 2 RCTs | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE1 |

| Quantity of service provision ‐ primary healthcare visits by children | We are uncertain of the effect of paying higher fees for service on the number of primary care visits by children compared with the normal level of fees due to very low‐certainty evidence. | 1 RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

|||

| Quality of service provision | None of the included studies reported on quality of service provision. | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Patient outcomes | None of the included studies reported on patient outcomes. | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Healthcare provider outcomes (such as work morale or workload) | None of the included studies reported on healthcare provider outcomes. | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Costs | We are uncertain if paying higher fees to healthcare providers for immunisations delivered influences the net expenditure per year on eligible children compared with the normal level of fees because the certainty of the evidence is very low. | 1 RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3 |

|||

| Unintended or adverse effects | None of the included studies reported on adverse effects. | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). FFS: fee‐for‐service; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is low. Moderate certainty: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is moderate. Low certainty: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different** is high. Very low certainty: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different** is very high. ** Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision | ||||||

1We rated two RCTs as unclear risk of bias (Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001), downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for limitation in study design.

2We rated one RCT as high risk of bias (Davidson 1992), downgrading the certainty of the evidence two levels for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physicians in Suffolk County, New York).

3We rated one RCT as high risk of bias (Davidson 1992), downgrading the certainty of the evidence two levels for limitation in study design and one level for indirectness (only one study targeting primary care physicians in Suffolk County, New York).

Background

Description of the condition

Health care is a labour‐intensive service industry, so healthcare provision is directly influenced by healthcare providers' behaviours in delivering services. Examining optimal payment methods for healthcare providers is a key issue in ensuring care is delivered in a cost‐effective way to patients. Previous Cochrane Reviews have focused largely on physician payment methods (Flodgren 2011; Giuffrida 1999; Gosden 2000; Scott 2011). This review focused on payment methods for all healthcare providers in stand‐alone outpatient healthcare settings. Outpatient healthcare settings can vary considerably across countries, and are defined in this review as settings outside of inpatient hospitals for care where a bed is not required. They could include the private or public offices or clinics of primary care physicians and other specialists and healthcare providers. These may be stand‐alone buildings or could be adjacent to hospitals. Examples are care provided in stand‐alone community healthcare centres, clinics, urgent care centres, family planning centres, dental clinics, and allied health care (e.g. physiotherapy), but would exclude surgical day‐only procedures and emergency departments. The defining characteristics of outpatient care are the inclusion of services that involve a consultation with patients by healthcare providers, where they provide advice, prescriptions, immunisations, simple diagnostic tests, and some simple minor procedures and treatments that can be given in an office setting. Outpatient care may be the first point of contact for patients, or patients may be referred by other healthcare providers to outpatient care for more specialised care. Outpatient can play an important role in gatekeeping and rationing access to more expensive hospital care, and so can help reduce health expenditures.

Description of the intervention

Individual healthcare providers' behaviours directly influence the type, quantity, quality, and access to health services provided to patients. Several studies have summarised the determinants of healthcare providers' behaviours in health services delivery (Rowe 2005; WHO 2006). The method by which healthcare providers are remunerated (the payment method) has been frequently used by governments, health insurers, and employers to influence the behaviours of healthcare providers to meet specific objectives (Fairbrother 1999; Langenbrunner 2004). Payment methods refer to the way in which funds are received by a healthcare provider and used a personal income. The focus is on payment methods that influence health professional's personal income, rather than funding models aimed at healthcare organisations, although the two may interact. The most commonly used payment systems to remunerate healthcare providers are salary, capitation, fee‐for‐service, pay for performance, and mixed or blended systems of payment.

Salary: healthcare providers are paid based on the time spent at work. Salaried healthcare providers are usually employees of healthcare organisations, with these organisations paid using other methods such as global budget, FFS, and capitation.

Capitation: healthcare providers are paid a prospective fixed payment per period of time for each individual enrolled with the health professional.

Fee for service (FFS): healthcare providers are reimbursed based on each specific service, procedure, or visit provided, such as consultations, x‐ray tests, or surgical operations.

Pay for performance (P4P): the payment is directly linked to the achievement of specific behaviours defined in terms of the performance of healthcare providers. P4P can be used to pay individuals, groups of people, or organisations by government or insurers. Pay‐for‐performance schemes vary widely in terms of the types of performance that are targeted, how performance is measured, when payments for performance are paid, and the proportion of total reimbursements that is paid for performance (Witter 2012).

Blended or mixed payment: more than one of the above payment methods may be used at the same time, with a proportion of the health professional's income coming from each type of method.

How the intervention might work

The mechanism through which payment methods influence behaviour is through their effect on the income of healthcare providers. Earning income is a key driver of individual's consumption and leisure activities, and economic theory assumes that individuals are motivated only by monetary extrinsic rewards. Generally and in practice, extensions of this theory recognise that payment methods may have less of an impact if there are other sources of motivation from working, such as improving the health of patients. Payment to healthcare providers happens when funds are transferred from employers, patients, or insurers to individual healthcare providers in exchange for the provision of healthcare services. Each payment method may be part of a formal contract or agreement between the payor and payee, which may also specify working conditions, other in‐kind benefits, and detail about what is required in providing the services. Under each payment method, the expected total income must first be sufficient to encourage the health professional to work and enter into a contract. Payment methods in these contracts can be changed, or healthcare providers can move to a different job (contract) with a different payment method, raising the issue of selection bias when examining the effects of changes to payment methods.

Assuming income is sufficiently important to healthcare providers, the payment method will influence behaviour depending on the change to the unit of payment or a change to the level of payment for each unit. The unit of payment for those on salaries and who receive an hourly wage is hours worked, and income can be increased only by working more hours. The unit of payment in capitation payment is the number of enrolled patients, and so income can only be increased by increasing the number of enrolled patients. For those on FFS, income can rise only by increasing the number of services provided to existing or new patients. For those paid by P4P, income can only be increased by improvements in performance. In blended payment, a number of different units of payment are used, and so a range of behaviours can increase income.

Moving from one payment method to another, or changing the mix of payment methods in blended payment, will depend on the change to the unit of payment. With four different payment methods, moving from one to another defines many different combinations of comparators and interventions, each of which may have different effects on behaviour depending on the comparator and intervention units of payment. Under a new unit of payment, healthcare providers are assumed to adjust their work behaviours in ways that maximise their utility (including utility from the consumption of goods and services derived from their income, and utility from non‐work activities). A new payment method will provide the health professional with a different way to increase their income (and utility) depending on the unit of payment. healthcare providers may also reduce the costs of providing care to maximise their income, such as changes in skill mix, how they use their time (e.g. changes to consultation length), changes in effort, and changes to other practice costs (e.g. use of administrative staff). A change in payment methods could also lead healthcare providers to change jobs, which can influence patient access to care. The main hypotheses regarding the expected changes in behaviour from each payment method are outlined below, although the precise hypotheses will also depend on the existing (comparator) payment method, as well as the new payment method.

Salaried payment

Salaried payment focuses on the amount of time at work, usually in terms of hours. For a given number of hours worked, salaries are fixed in the short run, and do not provide any financial incentives for increased effort or increased quality of care or performance. In the longer run, financial incentives can encourage effort beyond some minimum to avoid being sacked and can also provide financial incentives to meet some level of performance to keep the job if on fixed‐term contract. In the longer run, salaried payment is also accompanied by different levels of salary (wages) for different levels of seniority (salary increments and promotion). Financial incentives for increased performance can be built into the salary scale (increments and promotion), driven by additional income from advancement up the salary scale. Progression up the salary scale may be automatic depending only on years of service, for example, or it may be based on a subjective measure of performance assessed in an annual performance review. This provides 'career' financial incentives to improve performance to obtain promotion and advancement.

Capitation

Payments are made per patient, and so capitation is normally accompanied by a system with patients registering/enrolling with a specific provider to receive care. Capitation is a prospective‐based payment system where healthcare providers can predict their income from each enrolled patient in advance. Capitation payment encourages healthcare providers to attract more patients, and so compete with other healthcare providers, such as by improving quality and access to care and those aspects of care that are valued by patients. With a fixed payment for each patient, the difference between the costs of treatment and the fixed payment defines the profit or income going to the health professional. More complex patients lead to higher costs and less profit. Capitation therefore includes an inbuilt incentive to minimise costs by selecting only the healthiest patients to enrol and treat, which can have adverse consequences for access to health care for those with more complex and costly conditions. Capitation may provide incentives to reduce costs by changing skill mix or providing short consultations that could be related to increased prescribing, fewer treatments provided, and more referrals compared to FFS and P4P. Though cost‐consciousness is important, it can also lead to lower quality and poor access if these are not separately monitored and rewarded (e.g. in a blended payment scheme that combines capitation and P4P). Capitation payments are usually 'risk‐adjusted', where higher payments are provided for patients with more complex/costly conditions. This reduces the incentives for patient selection (or 'cream skimming') and cutting costs that might reduce quality. It is also argued that capitation payment may provide incentives for healthcare providers to provide more preventive activities to patients so that they do not return in the future. This reduces future costs and increases provider income in the longer term, as patients make fewer visits.

Fee for service

This is likely to increase the number of services provided by healthcare providers compared to other payment methods, either through providing more services to each patient or by attracting more patients. FFS could lead to increased and less predictable health expenditures compared to other forms of payment depending on how fees are determined, as well as the overprovision of unnecessary services, including overdiagnosis. FFS also provides incentives for healthcare providers to provide treatment themselves rather than refer to others, especially compared with salaried or capitation payment.

Pay for performance

P4P payment is directly linked to performance targets that are often related to the type, mix, and quality of care delivered. P4P designs are complex and vary depending on how performance is measured, the level of the performance target, and many other components. Performance is usually defined in terms of the quality of care provided, which might include whether certain activities were performed or not (e.g. taking blood pressure) or the outcome of that activity (e.g. whether the measure of blood pressure is within accepted clinical guidelines). Payment may be made for each extra activity (e.g. each patient who immunised), or as a lump‐sum bonus for achieving a prespecified target. Financial penalties may also be used if targets are not met. The performance target for payment may be absolute (e.g. 80% of a target population being immunised) or relative to other healthcare providers (e.g. whether the provider is in the top quartile of immunisation rates across all providers), or based on the absolute (or relative) change in performance from one period to the next (Ogundeji 2016; Van Herck 2010). In practice, P4P rarely exists on its own, and is usually part of a blended payment method.

Blended payments

Blended payments reduce the 'extremes' of single payment methods by providing a range of methods through which providers can increase their income, and can combine incentives to be cost‐conscious as well as maintain and improve quality (value‐based payment).

In addition, within each payment method the level of payment for each unit of payment (hours, patients, services, quality) may be decreased or increased. This may encourage more of the rewarded activity if the additional (marginal) income is greater than the additional (marginal) costs of increasing the activity, and also assuming that income is sufficiently important to the health professional compared to other sources of utility. The importance of income (monetary motivation) will likely vary across different types of healthcare providers leading to heterogenous effects of changes to payment methods.

Why it is important to do this review

Payment methods can change the behaviours of healthcare providers through financial incentives, and then influence number, mix, cost, and quality of care provided. The design of appropriate payment systems is a key issue for governments, health insurers, health organisation managers, and all relevant policymakers who expect the efficient use of limited funds in the health system.

This review focused on payment methods for individual healthcare providers. Other Cochrane Reviews examine payment methods for doctors across all types of setting (Flodgren 2011; Giuffrida 1999; Gosden 2000; Scott 2011), whilst this review includes all kinds of healthcare providers only in outpatient healthcare settings. Together with the Cochrane Reviews on payment methods for outpatient facilities (rather than individual healthcare providers) (Yuan 2017) and hospitals (Mathes 2014; Mathes 2019), this review contributes to evidence to encourage healthcare providers to provide high‐quality, efficient, and equitable health care to their patients.

Objectives

To assess the impact of different payment methods for healthcare providers working in outpatient healthcare settings on quantity and quality of health service provision, patient outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes, cost of service provision, and adverse effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials, including cluster‐randomised trials

Non‐randomised trials

-

Interrupted time series (ITS) and repeated measures studies with:

a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred;

at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention.

-

Controlled before‐after (CBA) studies with:

contemporaneous data collection;

a minimum of two intervention and two control sites.

Types of participants

Healthcare providers working in outpatient care facilities. Healthcare providers include, for example, primary care physicians and other non‐surgical specialists, dentists, midwives, nurses, or allied health (WHO 2006). Healthcare providers working in surgical day‐only procedures and emergency departments were excluded.

Types of interventions

The payment method is defined as the mechanism used to remunerate individual healthcare providers. Payment methods for healthcare providers include:

salary;

fee‐for‐service (FFS): healthcare providers are reimbursed based on specific items provided;

capitation: healthcare providers are paid a predetermined fixed rate in advance to provide a defined set of services for each enrolled individual for a fixed period;

pay for performance (P4P): the payment is directly linked to the performance of healthcare providers;

blended payments.

We included studies that evaluated changes from one type of payment method to another, changes to the design of a payment method, or changes to the level of payment. Any of these may change the level of provider income, or create different opportunities for the health professional to increase their income and change the care they provide.

We excluded studies of interventions that were primarily targeted at paying at practice or organisational level; in this review, we focused only on changes to payments made directly to healthcare providers. Another Cochrane Review has evaluated the payment at practice or organisational level (Yuan 2017). For example, the QOF (Quality and Outcomes Framework) applied in the UK is a pay‐for‐performance scheme delivering funding to general practices, not directly to general practitioners, and so studies evaluating the QOF were excluded from this review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The main behavior of healthcare providers is to provide health care to patients, so the primary outcomes included in this review are objective measures of health services provision and other measures which are closely related to the supply of health services in outpatient care facilities, including the following.

Service provision and process outcomes

-

Quantity of health services provided, including those:

measured as risk ratio (RR), e.g. for patients getting an aspirin prescription, for referring smokers to a quit line, for women having any prenatal care;

measured as mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD), e.g. rate of screening service per 100 prescriptions, average length of service time.

-

Quality of health services provided, including those:

measured as RR, e.g. for physicians adhering to clinical guidelines;

measured as MD or SMD, e.g. the quality score for provision of certain health services.

-

-

Patient outcomes (the effect of changes in service provision or process outcomes on measures of length of life, quality of life, or clinical measures closely related to these outcomes)

-

Patients' intermediate and final health outcomes, including those:

measured as RR, e.g. if a smoker has sustained abstinence from smoking, if blood pressure has been controlled;

measured as MD or SMD, e.g. blood pressure level of patients with hypertension, health‐related quality of life, mortality.

-

-

Healthcare provider outcomes (the outcomes related to consequences on individual providers after delivering services), including those:

measured as RR, e.g. if individual professionals are satisfied with work or job turnover;

measured as MD or SMD, e.g. hours worked or the income level of healthcare providers.

-

Costs of delivering services, including those:

measured as MD or SMD, e.g. cost per service, administration costs, total cost for purchasers, changes in skill mix.

-

Unintended or adverse effects, including those:

measured as RR, e.g. patient selection and poorer access to care for disadvantaged populations;

measured as MD or SMD, e.g. the number of unnecessary services (overtreatment and overdiagnosis).

Secondary outcomes

Satisfaction of patients or other stakeholders; job mobility.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, part of the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com/) (searched 5 March 2019)

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, part of the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com/) (searched 15 July 2017)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL2019, Issue 3, part of the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com/) (searched 5 March 2019)

MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to March 04, 2019, Ovid (searched 5 March 2019)

Embase 1974 to 2019 March 04, Ovid (searched 5 March 2019)

Web of Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science, 1990 to present (ISI Web of Knowledge) (searched 5 March 2019)

PubMed, NLM (searched 10 December 2018)

Dissertations and Theses Database, 1861 to present, ProQuest (searched 10 December 2018)

EconLit, 1969 to present, ProQuest (searched 10 December 2018)

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CHKD‐CNKI), 1915 to present (searched 10 December 2018)

Chinese Medicine Premier (Wanfang Data), 1988 to present (searched 10 December 2018)

IDEAS (Research Papers in Economics), 1927 to present (searched 30 December 2017)

POPLINE (Population Information Online), 1970 to present, K4Health (searched 30 December 2017)

The EPOC Information Specialist (TSC) helped develop some of the search strategies in consultation with the review authors.

Search strategies are comprised of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms. We applied no language limits. We searched all databases from database start date to date of search.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We conducted a grey literature search to identify studies not indexed in the databases listed above.

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (www.opengrey.eu/) (searched 10 December 2018)

World Health Organization (WHO) (www.who.int/) (searched 17 November 2018)

World Bank (www.who.int/) /searched 17 November 2018)

Trial registries

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/) (searched 27 June 2019)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform) (searched 27 June 2019)

In addition, we:

searched reference lists of all relevant papers identified;

searched Web of Science Core collection; KCI‐Korean Journal Database; Russian Science Citation Index; SciELO Citation Index, Clarivate Analytics for papers that cited any of the included studies in this review (searched 8 February 2019);

searched PubMed for related citations to any studies to be included in the review;

contacted authors of relevant papers regarding any further published or unpublished work;

We re‐ran the search strategies in August 2020 and screened the identified records. Potentially relevant studies are awaiting classification and will be assessed at the next update.

All search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors scanned the titles and abstracts of all articles obtained from the search and retrieved the full text of articles deemed relevant. Two review authors independently assessed full texts of studies for inclusion. Any disagreements on inclusion were resolved by discussion with a third review author or EPOC editor.

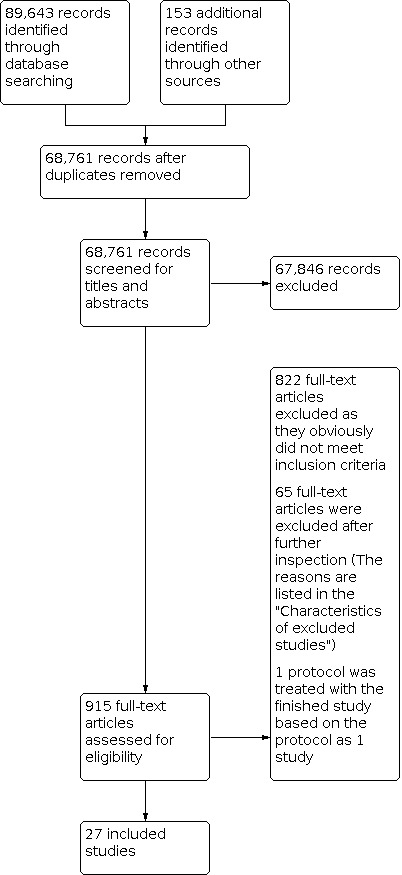

The screening process and results are reported in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). All included studies are described in the Characteristics of included studies table, even those for which useable results for reanalysis or synthesis were not reported. Studies that initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but that were excluded are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently carried out data extraction using a data extraction form adopted from the Cochrane good practice data collection form (EPOC 2013a). We extracted the following information.

General information, including title, reference details, author contact details, and publication type.

Participants and setting.

Study method.

Intervention groups, including payment method description, duration of intervention, if patients can choose providers, how purchasers monitored the implementation of payment.

Outcomes, including outcome measures, time points measured, unit of measurement, and person measuring outcomes.

Results, including result reported by authors, analysis method, unintended effects, if analysis required and possibility.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third review author or the EPOC contact editor. For ITS studies that reported time series data that were not appropriately analysed, we extracted and reanalysed the data as described in the EPOC resources for review authors (EPOC 2013b).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the EPOC suggested 'Risk of bias' criteria to assess the risk of bias for each outcome in all included studies (EPOC 2013c). For each criterion, two review authors independently described what was reported in the study, commented on the description, and judged the risk of bias. Any unresolved disagreements were discussed with a third review author and, if consensus could not be reached, with the EPOC contact editor. We summarised the overall risk of bias across criteria for the outcomes of the included studies. For randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, and controlled before‐after studies, we primarily considered four criteria: baseline outcome measurements; baseline characteristics measurements; incomplete outcome data addressed; and protection against contamination. If these four criteria were all scored 'low risk of bias' for the outcome in a given study, the summary assessment was low risk of bias; if one or more key criteria were scored 'unclear', the summary assessment was unclear risk of bias; and if one or more key criteria were scored 'high risk of bias', the summary assessment was high risk of bias. For ITS studies, we primarily considered the following criteria when summarising the overall risk of bias: intervention independence, intervention affecting data collection, and incomplete outcome data addressed.

Measures of treatment effect

For randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, and controlled before‐after studies, we recorded or calculated risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. If adjusted analysis was done, we reported the effect estimates provided by the study authors, also converting them into RR if possible. For continuous outcomes, we recorded or calculated mean difference (MD) with 95% CI if the studies to be synthesised had the same outcome measures. We calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI if the studies to be synthesised assessed slightly different outcome measures within the same broad outcome category.

Data were insufficient data to permit statistical pooling for most outcomes. In order to facilitate comparison of the effect sizes of the included studies, we did the following: if the baseline levels were available, we reported the point estimates of absolute change adjusted for baseline differences or the relative change adjusted for baseline differences for all included outcome measures. If the baseline levels were not available, we reported the point estimates of absolute change and relative change for all included outcome measures.

The absolute change adjusted for baseline differences is defined as 'baseline‐post difference', and the formula is: (intervention group post level − intervention group baseline level) − (control group post level − control group baseline level). The relative change adjusted for baseline differences is calculated by the following formula: ((intervention group post level − intervention group baseline level) − (control group post level − control group baseline level))/(control group post level − control group baseline level).

For ITS and repeated measures studies, we reported the difference between the predicted value based on the pre‐intervention trend and the estimated value based on the change in level and post‐intervention trend at relevant time points (including immediately after the intervention (change in level), one year, two years, and three years).

Unit of analysis issues

This review analysed the impact on performance on the level of the individual, so the allocation and analysis unit should be aggregated to physicians. We planned to reanalyse studies that allocated clusters (e.g. clinics in one district) but that did not account for clustering if we were able to extract the intracluster coefficient. All included studies reported having accounted for and adjusting for clustering in their analysis.

Dealing with missing data

If any data needed for meta‐analysis or reanalysis (e.g. standard deviations, numbers of events, and subgroup analyses) were missing, we attempted to calculate them based on available data on the same outcome (e.g. calculation of standard deviation from CI). If these data were not available, we contacted the study authors to request the missing data. However, we did not receive responses from the relevant study authors and therefore reported the data that were available. For these studies, we reported the point estimate of the effect measures without CIs. Where data on subgroup analyses were missing, we were not able to include these subgroups in our analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We conducted meta‐analysis to synthesise the effect measures of included studies if they met the following criteria.

Similar intervention payment method and comparison payment, based on the payment method categories described above.

Similar participants, e.g. the targets of the payment method were all primary care physicians.

The outcome measures fell into the same outcome category, e.g. the outcome measures were all health service provision process measures, or patient outcomes measures.

When the included studies were sufficiently similar based on the above criteria, we used the Chi2 test and I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity. When the P value from a Chi2 test was smaller than 0.1, we interpreted this as an indication that the observed difference in results across studies was not compatible with chance alone. We used the I2 statistic to quantify the level of statistical heterogeneity.

As there is considerable heterogeneity in the design of payment methods, we attempted to explore this through the prespecified subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). We used caution in interpreting results from meta‐analyses with high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use a funnel plot to examine asymmetry and assess the potential of any asymmetry being due to publication bias. However, due to the limited number of studies with the same outcomes in each comparison, we decided not to undertake funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We conducted a structured synthesis as described in the EPOC resources for review authors (EPOC 2013d). We first categorised the comparisons and outcomes, and then described the effects of different kinds of payment methods on different categories of outcomes. As mentioned above, there were two kinds of payment change with mechanisms for changing behaviour: additional incentives leading to an increase in total funding, or changes in the payment model without changes to the total funding received. These two mechanisms were assessed in different comparisons.

We synthesised the effects of studies that used the same type of study design. We conducted meta‐analysis for randomised trials, but not for controlled before‐after and interrupted time series studies due to insufficient data. For the meta‐analyses, we initially used a fixed‐effect model to pool data within a study if the study included more than one outcome indicator under the same category of outcome measures. We then used a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis across studies. This was because the payment method designs usually included several components; the payment methods conducted by different purchasers or in different areas were rarely exactly the same; and there were differences in outcome measures falling in the same outcome category. For randomised trials where the available data did not permit meta‐analysis, and for all controlled before‐after and interrupted time series studies, we reported the medians and full ranges of the available point estimates of effect sizes. We analysed these firstly within, and then secondly across, the studies for the same category of outcome measures. It was not possible to report an interquartile range due to the very limited number of data points.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the protocol for this review, we hypothesised a series of factors that might affect the size of effects of payment methods and planned to perform subgroup analysis based on these factors, such as size of fee, duration of follow‐up, targeted population, if there were multiple providers, if there was monitoring of delivery of services, the frequency of monitoring, the frequency of payment, and baseline performance level. However, these subgroup analyses could not be conducted due to the limited number of included studies with similar comparisons and outcomes. Furthermore, the included studies reported limited detail on the characteristics of payment methods. 'Duration of follow‐up' and 'targeted population' were reported more often in the included studies, and these factors are presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

1. Outcome measures of included studies.

| Study | Outcomes | Length of observation |

| Quantity of health services provided | ||

| Bilardi 2010 |

|

12 months |

| Christensen 2000 |

|

20 months |

| Clarkson 2008 |

|

18 months |

| Davidson 1992 |

|

18 months |

| Fairbrother 1999 |

|

12 months |

| Fairbrother 2001 |

|

12 months |

| Flierman 1992 |

|

12 months |

| Gleeson 2017 |

|

12 months |

| Gosden 2003 |

|

18 months |

| Greene 2013 |

|

15 years |

| Hickson 1987 |

|

24 months |

| Kouides 1998 |

|

12 months |

| Krasnik 1990 |

|

9 months |

| Lee 2010 |

|

24 months |

| Li 2013 |

|

120 months |

| Lurie 1992 |

|

24 months |

| Twardella 2007 |

|

12 months |

| Yesalis 1980 |

|

36 months |

| Yesalis 1984 |

|

36 months |

| Young 2007 |

|

‐ |

| Quality of health services provided | ||

| Chung 2010 |

|

24 months |

| Gosden 2003 |

|

18 months |

| Petersen 2013 |

|

12 months |

| Young 2007 |

|

‐ |

| Young 2012 |

|

36 months |

| Patient outcomes | ||

| Gleeson 2017 |

|

‐ |

| Houle 2016 |

|

45 months |

| Jensen 2014 |

|

21 months |

| Lurie 1992 |

|

11 months |

| Petersen 2013 |

|

16 months |

| Singh 2015 |

|

12 months |

| Twardella 2007 |

|

12 months |

| Healthcare provider outcomes | ||

| Gosden 2003 |

|

18 months |

| Gray 2015 |

|

72 months |

| Costs | ||

| Davidson 1992 |

|

18 months |

| Lee 2010 |

|

24 months |

| Yesalis 1980 |

|

36 months |

| Yesalis 1984 |

|

36 months |

| Adverse effects | ||

| Hickson 1987 |

|

24 months |

| Petersen 2013 |

|

12 months |

LDL: low‐density lipoprotein UTD: up‐to‐date WHO: World Health Organization

2. Payment methods for the vulnerable populations.

| Target population | Payment methods | Outcomes |

| The elderly | Not reported in included studies | Not reported in included studies |

| The disabled | Not reported in included studies | Not reported in included studies |

| Minorities | Not reported in included studies | Not reported in included studies |

| People with low levels of education | Not reported in included studies | Not reported in included studies |

| Children | ||

| Clarkson 2008, cluster‐randomised trial | FFS remuneration | Children with 1 or more sealant per dentist |

| Davidson 1992, randomised trial | Capitation, FFS high rate compare with FFS (low rates) | Physician visits, hospitalisations |

| Jensen 2014, controlled before‐after study | Mixed system of capitation and FFS contracts | Birth weight, preterm birth, very preterm birth, fetal growth |

| Singh 2015, controlled before‐after study | Performance bonus | Weight, WHO malnourished status |

| Women | ||

| Bilardi 2010, cluster randomised trial | P4P (a small incentive payment per test) | Women being tested |

| People living in rural or remote areas | ||

| Yesalis 1980; Yesalis 1984, controlled before‐after study | Capitation compare with FFS | Rate of generic substitution per 100 prescriptions Percentage of Medicaid prescriptions classified as multi‐source drug products Numbers of prescriptions involving changes in labeller on refills (0 to 5 days) |

| Low‐income populations 2 | ||

| Christensen 2000, randomised trial, Medicaid recipients | Financial incentive (P4P) | Patients receiving cognitive services |

| Gleeson 2017, controlled before‐after study, Medicaid | P4P plus existing FFS compare with FFS | Adolescent well care, inactivated polio vaccine |

FFS: fee‐for‐service P4P: pay for performance WHO: World Health Organization

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with imputed data and studies with an overall high risk of bias. Due to the limited number of studies included for each comparison, and because there were no studies with an overall high risk of bias included in meta‐analysis, we did not conduct the sensitivity analysis as planned.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created 'Summary of findings' tables for the main intervention comparisons and most important outcomes: quantity and quality of health services provided, provider outcomes, costs, health outcomes, and adverse effects. For the comparisons and outcomes that included randomised trials, results were reported in the 'Summary of findings' table. For the comparisons and outcomes for which randomised trials were not found, we reported the results of controlled before‐after or interrupted time series studies where these were available. Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low using the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, publication bias) (Guyatt 2008). We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions,Higgins 2020, and the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2013e), employing GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT 2020). Any disagreements on certainty ratings were resolved by discussion. We provided justification for decisions to down‐ or upgrade the ratings using footnotes and made comments to aid readers' understanding of the review where necessary. We used plain language statements to report these findings in the review (EPOC 2018).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

Search strategies yielded 89,643 references, which two review authors examined independently. We screened this large number of references because the searches were conducted without the study design filters in MEDLINE and Embase in order to also identify relevant studies for a larger scoping review on payment for health facilities or individual providers. We retrieved 915 full texts of articles regarded as potentially relevant, which two review authors read and evaluated independently. We initially assessed 92 full texts of studies as meeting the inclusion criteria for study designs and evaluating effectiveness of payment methods on healthcare providers working in outpatient health facilities. During data extraction we confirmed the inclusion of 27 studies which evaluated payment methods targeting individual healthcare providers in outpatient health facilities. See Figure 1.

We re‐ran the search strategies in August 2020. We screened the records identified by the search, and have listed two potentially relevant studies under Studies awaiting classification. We will assess these studies at the next update.

Included studies

The 27 included studies are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies.

Study design

We included 27 studies (see Characteristics of included studies): 12 randomised trials (Bilardi 2010; Christensen 2000; Clarkson 2008; Davidson 1992; Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001; Hickson 1987; Houle 2016; Kouides 1998; Lurie 1992; Petersen 2013; Twardella 2007); 13 CBA studies (Chung 2010; Flierman 1992; Gleeson 2017; Gosden 2003; Gray 2015; Greene 2013; Jensen 2014; Krasnik 1990; Lee 2010; Li 2013; Singh 2015; Yesalis 1980; Yesalis 1984); and 2 ITS and repeated measure studies (Young 2012; Young 2007).

Participants and setting

The participants included healthcare providers working in outpatient care facilities. The majority of healthcare providers were primary care physicians (Bilardi 2010; Chung 2010; Davidson 1992; Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001; Flierman 1992; Gleeson 2017; Gosden 2003; Gray 2015; Greene 2013; Hickson 1987; Jensen 2014; Krasnik 1990; Lee 2010; Li 2013; Petersen 2013; Young 2007; Young 2012). Other participants included mental health physicians (Lurie 1992), pharmacists (Christensen 2000; Houle 2016; Yesalis 1980; Yesalis 1984), office staff (Kouides 1998), and health workers based in daycare centres for children (Singh 2015). Nine studies focused on vulnerable populations (Table 6), including children in four studies (Clarkson 2008; Davidson 1992; Jensen 2014; Singh 2015), women in one study (Bilardi 2010), people living in rural or remote areas in two studies (Yesalis 1980; Yesalis 1984), and low‐income populations in two studies (Christensen 2000; Gleeson 2017). Other vulnerable populations, such as people living with disabilities and minority groups, were not mentioned in the included studies.

Outpatient care centres were named differently in different health system settings, including private office‐based practices (Davidson 1992; Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001), medical practices (Twardella 2007), hospital outpatient clinics (Petersen 2013), community health centres (Christensen 2000; Houle 2016; Li 2013), and clinics (Bilardi 2010). Further information on these centres was not provided.

Most of the payment methods were implemented by health insurance schemes in high‐income countries or regions: three studies focused on P4P for general practitioners (GPs) in Australia, Bilardi 2010; Greene 2013, and Taiwan (Lee 2010); three studies evaluated P4P and capitation for family care physicians and GPs in Canada (Gray 2015; Houle 2016; Li 2013); one study evaluated P4P for GPs in Germany (Twardella 2007); three studies focused on changes of payment methods for GPs in Denmark (Flierman 1992; Jensen 2014; Krasnik 1990); and the remaining studies were conducted in the USA. Only one study focused on payment methods changed from fixed wages to performance pay for daycare centre health workers in India (Singh 2015).

Interventions and comparisons

We grouped the interventions and comparisons into four categories (see Table 7).

3. Interventions and comparisons in included studies.

| Comparison 1: P4P plus an existing payment method compared with an existing payment method | ||

| Study | Intervention | Comparison |

| Christensen 2000 | P4P + existing payment method | Capitation |

| Chung 2010 | P4P + existing payment method | Not described |

| Fairbrother 1999 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Fairbrother 2001 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Gleeson 2017 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Greene 2013 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Houle 2016 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Kouides 1998 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Lee 2010 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Li 2013 | P4P + existing payment method | FFS |

| Petersen 2013 | P4P + existing payment method | Not described |

| Singh 2015 | P4P + existing payment method | Salary |

| Young 2007 | P4P + existing payment method | Salary |

| Young 2012 | P4P + existing payment method | Salary |

| Comparison 2: FFS compared with existing payment methods | ||

| Study | Intervention | Comparison |

| Davidson 1992 | FFS | Capitation |

| Lurie 1992 | FFS | Capitation |

| Hickson 1987 | FFS | Salary |

| Yesalis 1984 | FFS | Capitation |

| Yesalis 1980 | FFS | Capitation |

| Comparison 3: FFS mixed with existing payment methods compared with existing payment methods | ||

| Study | Intervention | Comparison |

| Bilardi 2010 | FFS + existing payment method | Not explicitly described |

| Clarkson 2008 | FFS + capitation | Capitation |

| Twardella 2007 | FFS + existing payment method | Not explicitly described |

| Jensen 2014 | FFS + capitation | Capitation |

| Gosden 2003 | FFS + salary | Salary |

| Gray 2015 | FFS + capitation | FFS |

| Flierman 1992 | FFS + capitation | Capitation |

| Krasnik 1990 | FFS + capitation | Capitation |

| Comparison 4: Enhanced FFS compared with FFS | ||

| Study | Intervention | Comparison |

| Davidson 1992 | Increase in FFS per service payment rate | FFS |

| Fairbrother 1999 | Increase in FFS per service payment rate | FFS |

| Fairbrother 2001 | Increase in FFS per service payment rate | FFS |

FFS: fee‐for‐service P4P: pay for performance

1. P4P plus existing payment methods compared with existing payment methods

We included 14 studies that compared P4P added to an existing payment method versus an existing payment method (Christensen 2000; Chung 2010; Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001; Gleeson 2017; Greene 2013; Houle 2016; Kouides 1998; Lee 2010; Li 2013; Petersen 2013; Singh 2015; Young 2007; Young 2012). In this comparison, the purchasers of health services did not change the existing payment to providers, but used extra funds to pay health providers as incentives in order to motivate the provision of certain health services. The existing payment methods included capitation (Christensen 2000), FFS (Fairbrother 1999; Fairbrother 2001; Gleeson 2017; Greene 2013; Houle 2016; Kouides 1998; Lee 2010; Li 2013), and salary (Singh 2015; Young 2007; Young 2012). The authors of two studies did not explicitly describe the existing payment methods (Chung 2010; Petersen 2013).

2. FFS compared with existing payment methods