Abstract

Background

Dental professionals are well placed to help their patients stop using tobacco products. Large proportions of the population visit the dentist regularly. In addition, the adverse effects of tobacco use on oral health provide a context that dental professionals can use to motivate a quit attempt.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness, adverse events and oral health effects of tobacco cessation interventions offered by dental professionals.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register up to February 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised clinical trials assessing tobacco cessation interventions conducted by dental professionals in the dental practice or community setting, with at least six months of follow‐up.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently reviewed abstracts for potential inclusion and extracted data from included trials. We resolved disagreements by consensus. The primary outcome was abstinence from all tobacco use (e.g. cigarettes, smokeless tobacco) at the longest follow‐up, using the strictest definition of abstinence reported. Individual study effects and pooled effects were summarised as risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects models to combine studies where appropriate. We assessed statistical heterogeneity with the I2 statistic. We summarised secondary outcomes narratively.

Main results

Twenty clinical trials involving 14,897 participants met the criteria for inclusion in this review. Sixteen studies assessed the effectiveness of interventions for tobacco‐use cessation in dental clinics and four assessed this in community (school or college) settings. Five studies included only smokeless tobacco users, and the remaining studies included either smoked tobacco users only, or a combination of both smoked and smokeless tobacco users. All studies employed behavioural interventions, with four offering nicotine treatment (nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or e‐cigarettes) as part of the intervention. We judged three studies to be at low risk of bias, one to be at unclear risk of bias, and the remaining 16 studies to be at high risk of bias.

Compared with usual care, brief advice, very brief advice, or less active treatment, we found very low‐certainty evidence of benefit from behavioural support provided by dental professionals, comprising either one session (RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.41; I2 = 66%; four studies, n = 6328), or more than one session (RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.11; I2 = 61%; seven studies, n = 2639), on abstinence from tobacco use at least six months from baseline. We found moderate‐certainty evidence of benefit from behavioural interventions provided by dental professionals combined with the provision of NRT or e‐cigarettes, compared with no intervention, usual care, brief, or very brief advice only (RR 2.76, 95% CI 1.58 to 4.82; I2 = 0%; four studies, n = 1221). We did not detect a benefit from multiple‐session behavioural support provided by dental professionals delivered in a high school or college, instead of a dental setting (RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.65; I2 = 83%; three studies, n = 1020; very low‐certainty evidence). Only one study reported adverse events or oral health outcomes, making it difficult to draw any conclusions.

Authors' conclusions

There is very low‐certainty evidence that quit rates increase when dental professionals offer behavioural support to promote tobacco cessation. There is moderate‐certainty evidence that tobacco abstinence rates increase in cigarette smokers if dental professionals offer behavioural support combined with pharmacotherapy. Further evidence is required to be certain of the size of the benefit and whether adding pharmacological interventions is more effective than behavioural support alone. Future studies should use biochemical validation of abstinence so as to preclude the risk of detection bias. There is insufficient evidence on whether these interventions lead to adverse effects, but no reasons to suspect that these effects would be specific to interventions delivered by dental professionals. There was insufficient evidence that interventions affected oral health.

Keywords: Humans; Bias; Counseling; Dentists; Oral Health; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Schools; Smoking Cessation; Smoking Cessation/methods; Smoking Cessation/psychology; Tobacco Use Cessation; Tobacco Use Cessation/methods; Tobacco Use Cessation/psychology; Tobacco, Smokeless; Tobacco, Smokeless/adverse effects; Universities

Plain language summary

Can dental professionals help people to stop smoking or using tobacco products?

Keeping your mouth healthy

Tobacco can be smoked, chewed or sniffed (as snuff). The best thing that people who use tobacco products can do for their health is to stop using them. This lowers the risk of lung cancer and other diseases, including mouth cancer and gum disease.

Many people visit a dental professional at least once a year; some may visit more often. Dental professionals could motivate people to stop using tobacco by telling them about the health risks of continuing and the health benefits of quitting. Dental professionals include:

· dentists;

· dental hygienists;

· dental therapists; and

· dental nurses (referred to as dental assistants in some countries).

Why we did this Cochrane Review

We wanted to find out if dental professionals could help people to stop using tobacco by offering them advice and support. We also wanted to know if support from dental professionals had any unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that tested whether advice and support from dental professionals helped people to stop smoking, chewing or sniffing tobacco.

We looked for randomised controlled studies, in which the people taking part were assigned to different treatment groups using chance to decide which people received support to stop using tobacco. This type of study usually gives reliable evidence about the effects of a treatment.

Search date: we included evidence published up to February 2020.

What we found

We found 20 studies in 14,897 people who used tobacco products (smoking, chewing or sniffing tobacco). The studies took place in the USA (13 studies), the UK (two studies), Sweden (two studies), Japan (one study), Malaysia (one study) and India (one study). Most studies (16) were in dental clinics and four were conducted in schools or colleges.

All studies used behavioural programmes to help people stop using tobacco; these programmes aimed to boost motivation and offer advice on stopping. Four studies also included offering people nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or e‐cigarettes as well as a behavioural programme.

Nineteen studies were funded by government agencies or universities; one study reported that it received no funding.

For each type of behavioural programme tested, the studies measured how many people stopped smoking or using tobacco products for at least six months.

In all studies, the effect of receiving behavioural support from dental professionals was compared with:

· usual care (the studies did not state what this included);

· no support or advice;

· brief advice to stop smoking to improve health; or

· a less active form of behavioural support.

What are the main results of our review?

Behavioural programmes involving dental professionals and NRT or e‐cigarettes probably help more people to stop smoking. On average, 74 out of 1000 people stopped compared with 27 out of 1000 people who did not receive behavioural support (evidence from four studies in 1221 people).

Several sessions of behavioural programmes involving dental professionals may help people to stop using tobacco. On average,106 out of 1000 people stopped compared with 56 out of 1000 people who did not receive behavioural support (seven studies; 2639 people).

A single session of a behavioural programme may also help people to stop: on average, 45 out of 1000 people stopped compared with 24 out of 1000 who did not receive behavioural support (four studies; 6328 people).

We are uncertain about the effect of advice and support from dental professionals in settings other than a dental practice (such as in a school or college), because the studies that tested this were too small to show a reliable effect (three studies; 1020 people).

We are uncertain if behavioural programmes given by dental professionals had any unwanted effects, because only one study reported this information.

Our confidence in our results

We are moderately confident about the benefit of support from dental professionals plus NRT or e‐cigarettes. We are less confident about the benefits of one, or several, sessions of behavioural support from dental professionals.

We found weaknesses in the evidence. Some studies only asked people if they had stopped using tobacco, and did not use tests – such as testing their breath or saliva – to find out if they had stopped. Some studies did not describe clearly how they were conducted, or how they assigned people to the different groups. In some studies more than half of the people dropped out of the study before it ended.

Our results may change when more, high‐quality evidence becomes available.

Key messages

Advice and support from dental professionals that involves NRT or e‐cigarettes is more likely to help people to stop smoking.

Single or multiple sessions of advice and support may help people to stop smoking or using tobacco products.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Interventions delivered by dental professionals compared with control for tobacco cessation.

| Interventions delivered by dental professionals compared with no contact/intervention, usual care (non‐defined), very brief/brief advice or less treatment active controls for tobacco cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants who used tobacco products Setting: dental clinic, community school, or college Intervention: tobacco cessation interventions delivered by dental professionals Comparison: no contact/intervention, usual care (non‐defined), very brief/brief advice or less treatment active controls | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no contact/intervention, usual care (non‐defined), very brief/brief advice or less treatment active controls | Risk with Interventions delivered by dental professionals | |||||

|

Multi‐session behavioural support versus usual care, brief advice, or very brief advice, or less active treatment Smoking cessation (≥ 6 months follow‐up) |

56 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (65 to 173) | RR 1.90 (1.17 to 3.11) | 2639 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 3 | Intervention may help more people to quit |

|

Single session behavioural support versus usual care, brief advice, or very brief advice Smoking cessation (≥ 6 months follow‐up) |

24 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (25 to 83) |

RR 1.86 (1.01 to 3.41) | 6328 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2, 3, 4 |

Intervention may help more people to quit |

|

Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus no intervention/usual care, brief advice, or very brief advice Smoking cessation (≥ 6 months follow‐up) |

27 per 1000 | 74 per 1000 (42 to 129) |

RR 2.76 (1.58 to 4.82) | 1221 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3, 5 |

Intervention probably helps more people to quit |

|

Behavioural support from dental professional at high school/college versus usual care/no intervention Smoking cessation (≥ 6 months follow‐up) |

260 per 1000 | 392 per 1000 (224 to 689) | RR 1.51 (0.86 to 2.65) | 1020 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 6 | Sensitivity analysis removing Gansky 2005 removes heterogeneity and demonstrates a benefit of intervention. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded two levels because of very serious risk of bias: all studies were at high risk of bias.

2Downgraded one level because of inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity not accounted for by subgroup analysis

3Downgraded by one level because of imprecision: fewer than 300 events reported in analysis

4Downgraded one level because of risk of bias: only one study not at high risk of bias

5Not downgraded for risk of bias: two out of four studies at high risk of bias, but sensitivity analysis removing these studies did not substantially affect the result

6Downgraded two levels because of serious imprecision: fewer than 300 events reported in analysis and confidence intervals encompass both potential benefit and harm

Background

Description of the condition

Tobacco smoking is estimated to have been responsible for 100 million deaths worldwide in the 20th century, and it is predicted that this could reach one billion during the 21st century (WHO 2008). In addition to the well‐known harmful effects of smoking on respiratory and cardiovascular systems, tobacco use is a major risk factor for several oral diseases, including oral cancer and periodontitis (WHO 2017). The worldwide age‐standardised rate of oral cancer was 2.7 per 100,000 people in 2012 (Shield 2017) with the UK having 3700 cases in 2016 (Conway 2018). Smoking has been estimated to be responsible for up to 75% of these (Anantharaman 2011). Smoking cessation has positive effects on oral cancer risks, which reduce to the level of never‐smokers after 20 years (Marron 2010). Periodontitis (gum disease) is highly prevalent, with severe periodontitis being the sixth most prevalent health condition in the world, affecting approximately 11% of adults (Kassebaum 2014). Smoking is one of the biggest risk factors for disease development and progression, with smokers also having poorer responses to periodontal therapy (Chambrone 2013). Hence, smoking cessation has important roles in primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of oral diseases.

Description of the intervention

Dental professionals (including dentists, dental hygienists/therapists and dental nurses/assistants) can provide a range of tobacco use cessation interventions. Where appropriate training is available, interventions can focus on how to quit, advising that combining pharmacotherapy (including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline and bupropion) and behavioural support is best. This approach has evidence of effectiveness in many settings (Stead 2016). Typically, behavioural support in the dental setting involves very brief advice interventions (e.g. the '3As' approach: Ask, Advise, Act); or brief advice interventions (e.g. the '5As' approach: Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange); with several clinical guidelines recommending that dental professionals provide this support before referring people who smoke to another provider for further specialist support and/or pharmacotherapy (NICE 2018; PHE 2014; NCSCT 2012; ADA 2019).

How the intervention might work

Dental professionals are potentially in a unique position to support their tobacco‐using patients to quit. In many countries, large proportions of the population visit a dental professional on a regular basis throughout their life. With some dental diseases, such as periodontitis, regular supportive care can involve visits as frequently as every three months. There can be many 'teachable moments,' which can be powerful in initiating a quit attempt (e.g. tooth staining identification, periodontitis diagnosis or progression, tooth loss, oral cancer/pre‐cancer diagnosis). This regularity and relatively high frequency of interaction, as well as their credibility as a source of health advice, places dental professionals in a good position to deliver smoking cessation interventions.

Why it is important to do this review

Other Cochrane Tobacco Addiction reviews have evaluated behavioural and pharmacological interventions in a range of settings (Cahill 2014; Rigotti 2012; Stead 2013; Stead 2016). However, it is important to ascertain the effectiveness of these interventions in the dental setting or when delivered by dental professionals. The previous version of this review (Carr 2012) concluded that behavioural interventions delivered by dental professionals may increase quit rates in both cigarette and smokeless tobacco users. However, the review authors were unable to make conclusive recommendations about the type of interventions, due to limitations of the data.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness, adverse events and oral health effects of tobacco cessation interventions offered by dental professionals.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials (cluster‐RCTs)

Quasi‐randomised controlled trials (quasi‐RCTs)

Types of participants

Tobacco users (smokers or smokeless tobacco users) of any age willing to enrol in a tobacco cessation trial. Users of electronic cigarettes (e‐cigarettes) were not considered tobacco users. We included studies that randomised dental professionals or practices, as well as those that randomised individual tobacco users, provided that the specific aim of the study was to examine the effect of the intervention on tobacco cessation. We did not include trials that randomised dental professionals or practices to receive an educational intervention. Health professional training interventions are reviewed separately (Carson 2012).

Types of interventions

We included any intervention to promote tobacco use cessation that involved a component delivered by a dentist, dental hygienist or therapist, dental nurse/assistant or dental practice office staff, delivered in either a dental or community setting. Interventions could include brief advice to quit, provision of self‐help materials, counselling, pharmacotherapy or any combination of these, or referral to other sources of support. Interventions directed at smokers, smokeless tobacco users, or both, were all eligible for inclusion.

Comparators

This review included trials that compared tobacco cessation interventions with any of the following comparators.

No intervention.

Wait‐list controls.

Usual care, including brief advice interventions.

Other active interventions (as defined above).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Abstinence from tobacco (tobacco cigarettes, smokeless tobacco or all tobacco) at long‐term follow‐up (dichotomous)

To be eligible, studies had to report abstinence rates at least six months from baseline. We excluded trials that did not investigate tobacco‐use outcomes or did not have sufficiently long follow‐up. In trials with more than one measure of abstinence, we selected the measure with the longest follow‐up and the strictest definition, in line with the Russell Standard (West 2005). Therefore, we preferred biochemically validated over self‐reported abstinence, and prolonged or continuous abstinence over point prevalence abstinence. Abstinence rates were based on intention‐to‐treat analyses with drop‐outs and losses to follow‐up assumed to be continuing or relapsed tobacco users.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events (including serious adverse events), as reported by the authors

Oral health outcome measures, as reported by the authors

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

To identify studies for this update, we searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register on 21st February 2020. At the time of the updated search, the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Issue 1, 2020; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20200130; Embase (via OVID) to week 202005; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20200127; the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) trials registry at ClinicalTrials.gov; and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) to January 2020. See the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group website for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched to populate the Register.

See Appendix 1 for the search strategy used to search the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register for this review.

Searching other resources

We contacted the authors of known unpublished trials. Searches of the clinical trials registers, ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO's ICTRP, are carried out to populate the Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register, and so were incorporated into our search.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (RH and BH) independently checked the titles and abstracts of the studies generated by the search strategy for relevance. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and inclusion of a third review author when required. We obtained full‐text versions of papers of the potentially relevant studies. Two review authors (RH and BH) then independently assessed the full‐text papers for inclusion in the review, with any disputes resolved by discussion with a third review author. We did not limit inclusion by language and planned to seek translations when necessary (this was not required).

Data extraction and management

For each included study, two review authors (RH and BH) independently extracted data, using a standardised electronic data collection form. Review authors then cross‐checked this information between themselves, and resolved disagreements through discussion. If review authors of this Cochrane Review were also authors of an included study, we ensured that the data extraction and risk of bias assessment were done by other review authors or other researchers (see Acknowledgements). We extracted the following information about each study, which is presented in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Methods: study design; study location (i.e. country); study setting (e.g. dental practice); and study recruitment procedure.

Participants: number of participants (N); if this was a specialist population; if participants were selected based on motivation to quit; and participant characteristics (including gender, age, baseline average cigarettes/day, nicotine dependence, baseline motivation to quit and baseline self‐efficacy/confidence in quitting).

Interventions: comparator and intervention details including modality of support; details of provider training; overall contact time; number of sessions and use of pharmacotherapy.

Outcomes: definition of abstinence; longest follow‐up time; use of biochemical validation; oral health outcomes and adverse events.

Study funding sources and any reported author conflicts of interest.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported the risk of bias of included studies, in accordance with the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and specific 'Risk of bias' guidance developed by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. The latter states that performance bias (relating to the blinding of participants and providers) should not be assessed for behavioural interventions, as it is impossible to blind people to these types of interventions. Therefore, we reported on the following individual domains:

random sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); and

other sources of bias.

Two review authors (RH and BH) independently assessed risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion and inclusion of a third review author where required. A summary risk of bias judgement was derived for each study by applying an algorithm suggested in Section 8.7 (Table 8.7a) of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). Specifically, if the judgement in at least one of these domains was 'high risk of bias', we determined the summary risk of bias to be high. If there were no judgements of 'high' risk, but the judgement in at least one domain was 'unclear risk of bias', then we determined the summary risk of bias to be unclear. We only judged the summary risk of bias to be 'low' if our judgements in all domains were 'low risk of bias'.

Measures of treatment effect

For tobacco use abstinence, we calculated a risk ratio (RR) and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) for the cessation outcome in each trial included in the meta‐analyses. We calculated RRs as follows: (number of participants abstinent from tobacco in the intervention group/number of participants in the intervention group)/(number of participants abstinent from tobacco in the control group/number of participants in the control group). The previous version of this review (Carr 2012) used odds ratios (OR), but in line with Cochrane policy, we used RR in this update. We used the same methods to calculate the RR and 95% CI for the numbers of participants experiencing adverse events for each study, distinguishing where possible between adverse events likely attributable to intervention or tobacco use cessation, and those likely attributable to the dental study context. For oral health outcomes, we calculated mean differences (MD) with 95% CI for individual studies, where the relevant data were presented.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual. Where we deemed it possible and appropriate to the structure of the analysis, we combined all relevant experimental intervention groups of a given multiple‐arm study into a single intervention group, and combined all relevant controls of that study into a single control group,

When extracting data from cluster‐RCTs, we considered whether study authors had made allowance for clustering in the data analysis reported, and were available, used data adjusted for clustering effects. Where studies reported analyses that accounted for the clustered study design, we estimated the effect on this basis. Where this was not possible and the information was not available from authors, we carried out an 'approximately correct' analysis, according to current guidelines (Higgins 2011). We imputed estimates of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC), either as reported in the study, using estimates derived from similar studies, or by using general recommendations from empirical research. If we had been unable to do this, we would have given the effect estimate as reported by the study but reported the unit of analysis error (this was not required in our review update).

Dealing with missing data

Where abstinence data were missing, we contacted the study authors for further information or clarifications. We calculated quit rates on an intention‐to‐treat basis, where participants lost to follow‐up were assumed to be smoking, excluding deaths from the denominator.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the characteristics of included studies to identify any clinical or methodological heterogeneity before pooling studies and conducting meta‐analyses. Where we deemed studies homogeneous enough to be meaningfully combined, we conducted a meta‐analysis, and we assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We deemed an I2 of greater than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity.

Where there were enough data included in an analysis to draw meaningful conclusions, we conducted the subgroup and sensitivity analyses described below (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity; Sensitivity analysis) to investigate any potential causes of observed heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we had meta‐analysed comparisons of abstinence rates in at least 10 studies, we planned to assess reporting bias, using funnel plots. Funnel plots illustrate the relationship between the effect estimates from individual studies against their size or precision. The greater the degree of asymmetry, the greater the risk of reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We conducted our analyses in RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014). Where possible, we pooled studies for our tobacco cessation and adverse event outcomes, using Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects models to generate pooled RRs with 95% CIs. Where the event was defined as tobacco cessation, an RR greater than one indicated that more people successfully quit in the treatment group than in the control group. Where the event was defined as the number of participants experiencing adverse events, an RR greater than one indicated that more people experienced adverse events in the treatment group than in the control group. In order to account for the clinical heterogeneity among studies, and to better understand the effect of intervention intensity and setting, we conducted separate analyses pooling studies testing:

multi‐session behavioural support;

single‐session behavioural support;

behavioural support plus pharmacotherapy; and

behavioural support provided by a dental professional outside of a dental context.

For oral health outcome measures, we planned to pool using an inverse variance random effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used subgroup analyses for the primary outcome (within each comparison) to explore the impact of:

type of comparison intervention (no intervention; usual care; less intense intervention);

type of tobacco use by study participants (smoked tobacco; smokeless tobacco; a combination);

different recruitment methods that may indicate different levels of motivation to quit among participants (not selected based on motivation; more likely motivated).

The method of recruitment is likely indicative of study participants' motivation to quit tobacco use, as people who smoke are unlikely to visit their dentist specifically for smoking cessation advice. Therefore, in studies where dental professionals recruited participants visiting their dental practice for a check‐up or oral health reasons, participants would not necessarily be motivated to quit smoking (and so motivation is likely to have varied across the sample). However, studies that recruited participants by advertising for people who used tobacco to join a trial of a tobacco‐use cessation intervention might be more likely to attract participants with a higher baseline motivation to quit.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted the following sensitivity analyses:

removing studies deemed to be at high risk of bias;

removing Holliday 2019 from the analysis investigating behavioural support plus nicotine treatment, as Holliday 2019 provided e‐cigarettes, unlike the other studies that provided more traditional NRT;

removing Hanioka 2010 from the analysis investigating behavioural support plus nicotine treatment, as participants received multiple sessions with a dental professional, compared with the single session of support received in the other studies in this comparison; and

removing Gansky 2005 from the analysis investigating behavioural support delivered by dental professionals outside of a dental setting, as while the intervention comprised multiple sessions like the other studies in the comparison, only one was with a dental professional.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Following standard Cochrane methodology (Schünemann 2017), we used the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, inconsistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for our primary outcome. Depending on our assessment of these considerations in each intervention comparison, we judged the certainty of evidence for this outcome to be 'high', 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low'. To present these judgements, we used GRADEpro GDT to create a GRADE 'Summary of findings' table with the following intervention comparisons: multi‐session behavioural support; single‐session behavioural support; behavioural support plus pharmacotherapy; and behavioural support provided by a dental professional outside of a dental context. We used these judgements to draw conclusions about the certainty of evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies; Table 2; and Table 3, for additional details about studies.

1. Brief descriptions of cessation interventions.

| Study | Brief description of interventiona | Participant‐ or clinician‐centred intervention | Target of intervention‐ users? | Modality of intervention | Pharmacotherapy? |

| Andrews 1999 | Brief advice plus video‐based cessation program with phone follow‐up | Participant | Smokeless tobacco users | Face‐to‐face, telephone | No |

| Binnie 2007 | Counselling using the 5As plus nicotine replacement therapy | Participant | Cigarette users | Face‐to‐face | Yes, nicotine replacement therapy (patches or gum) |

| Cohen 1989 | Counselling with 4 steps and booklet provision plus | Participant | Cigarette users | Face‐to‐face | Yes, nicotine replacement therapy (gum) |

| Ebbert 2007 | Brief advice plus quit line referral | Participant | Cigarette users | Face‐to‐face, telephone | No |

| Gansky 2005 | School‐based intervention | Participant | Smokeless tobacco users | Face‐to‐face, internet | No |

| Gordon 2010a | 5As, discussion about pharmacotherapy and referral as needed | Participant | Intervention tailored to the type of tobacco use (cigarettes or smokeless) | Face‐to‐face | No |

| Gordon 2010b | 5As, nicotine replacement therapy and population‐specific printed material | Participant | Intervention tailored to the type of tobacco use (cigarettes or smokeless) | Face‐to‐face | Yes, nicotine replacement therapy (patches and lozenges) |

| Hanioka 2010 | Counselling at 6 visits and nicotine replacement therapy | Participant | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | Yes, nicotine replacement therapy (patches) |

| Holliday 2019 | 3As, offer of referral and e‐cigarette starter kit | Participant | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | Yes, e‐cigarette starter kit |

| Lando 2007 | Brief advice plus motivational interviewing | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face, telephone | No |

| McClure 2018 | Oral health counselling integrated into quit line calls (4‐5 calls + 16 text messages) | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Telephone, internet, text message | Yes, nicotine replacement therapy starter kit |

| Nohlert 2013 | Counselling sessions (8 x 40 minutes) | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | No but pharmacological advice given |

| Selvamary 2016 | Health education including pamphlet and video plus cognitive behavioural therapy | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | No |

| Severson 1998 | Brief advice plus video‐based cessation program with phone follow‐up | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | No |

| Severson 2009 | Brief advice plus video‐based cessation program with phone follow‐up | Participants | Smokeless tobacco users | Telephone | No |

| Stevens 1995 | Brief advice plus video‐based cessation program with phone follow‐up | Participants | Smokeless tobacco users | Face‐to‐face, telephone | No |

| Virtanen 2015 | Brief advice (5As) plus quit line referral | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | No |

| Walsh 1999 | College‐based intervention | Participants | Smokeless tobacco users | Face‐to‐face, telephone | Yes, nicotine replacement therapy (gum) |

| Walsh 2003 | School‐based intervention | Participants | Smokeless tobacco users | Face‐to‐face, telephone | No |

| Yahya 2018 | Brief advice (5As) plus quit line referral | Participants | Cigarette smokers | Face‐to‐face | No |

aFor further details see Characteristics of included studies table.

2. Results data from included studies.

| Study ID | Intervention | Control | Abstinence definition | Notes |

| Andrews 1999 | 40/391 | 8/238 | 12 months, sustained, all tobacco | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.0009, 75 clusters (dental practices). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 40/394, Control 8/239. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Binnie 2007 | 4/59 | 2/57 | 12 months, prolonged (repeated PP), all tobacco | Biochemically validated |

| Cohen 1989 | 7.7% | 3.1% | 12 months, PP, all tobacco | Not used in meta‐analysis as study arm denominator values not available |

| Ebbert 2007 | 15/61 | 6/22 | 6 months, PP, all tobacco | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.001, 8 clusters (dental practices). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 15/60, Control 6/22. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Gansky 2005 | 84/233 | 106/288 | 12 months, 30 day PP, ST | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.0197. 52 colleges. Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 103/285, Control 130/352. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Gordon 2010a | 37/1175 | 6/402 | 12 months, sustained, all tobacco | Two intervention arms combined. Individual data: 5As (27/817) and 3As (24/793). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 51/1610, Control 8/550. Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.012. 68 clusters (dental practices) Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Gordon 2010b | 28/530 | 8/439 | 7.5 months, prolonged, all tobacco | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.009, 14 clusters (dental clinics). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 74/1394, Control 22/1155. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Hanioka 2010 | 12/33 | 3/23 | 12 months, continuous, all tobacco | |

| Holliday 2019 | 6/40 | 2/40 | 6 months, continuous, smoking | Biochemically validated |

| Lando 2007 | 4/61 | 7/63 | 12 months, PP (30 day), smoking | |

| McClure 2018 | 121/358 | 109/360 | 6 months, 7 day PP, smoking | |

| Nohlert 2013 | 18/150 | 6/150 | 12 months, sustained, smoking | |

| Selvamary 2016 | 14/100 | 1/100 | 6 months, continuous, all tobacco | Biochemically validated |

| Severson 1998 | 68/2624 | 31/1322 | 12 months, sustained, all tobacco | Two intervention arms combined. Individual data: enhanced intervention (35/1374), minimal intervention (34/1305). Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.0004, 75 clusters (dental practices). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 69/2679, Control 32/1350. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Severson 2009 | 53/392 | 22/393 | 6 months, prolonged, ST | |

| Stevens 1995 | 25/245 | 19/273 | ||

| Virtanen 2015 | 10/195 | 7/210 | 6 months, sustained for 3 months, all tobacco | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.01, 27 clusters (dental practices). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 11/225, Control 8/242. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Walsh 1999 | 41/119 | 21/132 | 12 months, PP, ST | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.02, 16 clusters (colleges). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 59/171, Control 30/189. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Walsh 2003 | 26/114 | 17/134 | 24 months, sustained, ST | Cluster‐RCT, ICC 0.04, 44 clusters (schools). Raw unadjusted data: Intervention 32/141, Control 21/166. Adjustments for cluster design:

|

| Yahya 2018 | 29/193 | 8/207 | 6 months, 30 day PP, smoking |

ICC: intracluster correlation coefficient; PP: point prevalence abstinence; RCT: randomised controlled trial; ST: sustained abstinence

Results of the search

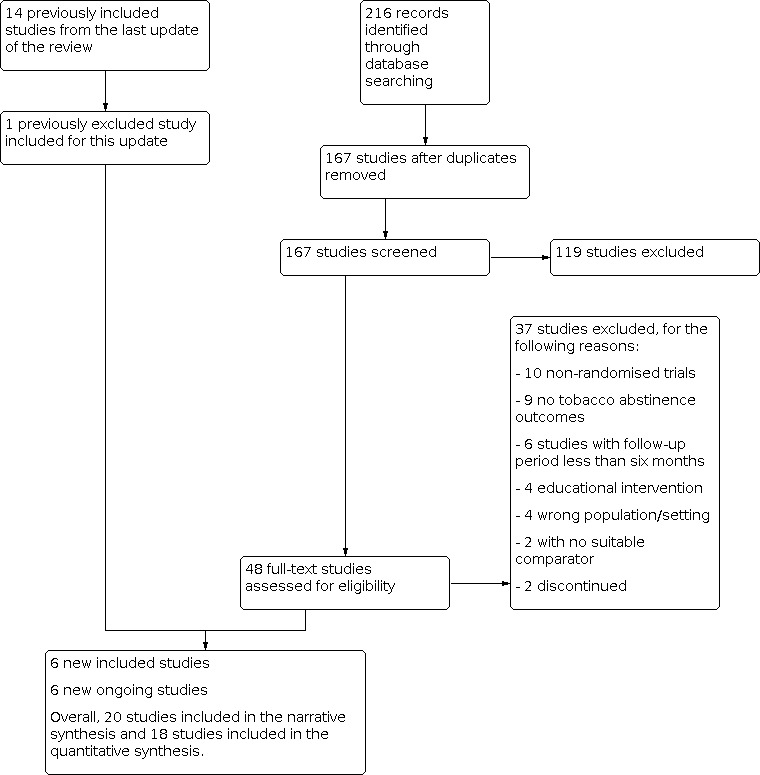

The searches for this update of the review retrieved 216 unique records. After title and abstract screening, we classified 48 studies as potentially eligible for inclusion. After full‐text article screening, we identified five new studies that met inclusion criteria. We also found one new citation providing longer‐term follow‐up data for a previously included study (study ID changed from Nohlert 2009 to Nohlert 2013). Another study was excluded from the previous version of this review because of unavailable study arm denominator values (Cohen 1989). However, we chose to include Cohen 1989 in this update, though we excluded the study's data from meta‐analysis. In summary, we included 20 studies in this review: five new studies, 14 previously included studies (one of which was updated with new data from a more recent publication), and one study that was previously excluded but is now included. The flow of studies through the systematic review process for this update is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram for most recent update.

Included studies

This review includes 20 studies involving 14,897 participants. Details of included studies can be found in Characteristics of included studies. Although Andrews 1999 and Severson 1998 reported findings from the same trial, they are treated here as separate studies since Andrews 1999 focussed on outcomes in smokeless tobacco users and Severson 1998 focussed on outcomes in smokers. We did not include Cohen 1989 in any meta‐analysis because study arm denominator values were unavailable. We did not pool McClure 2018 in meta‐analysis because the study setting was too different from the other studies.

We classified 81 studies (from both the review's previous version and this update) as potentially relevant studies that did not meet all inclusion criteria. We list these studies in Characteristics of excluded studies, along with their reasons for exclusion.

Types of studies

We included ten RCTs in which the individual participant was the unit of randomisation (Binnie 2007; Hanioka 2010; Holliday 2019; Lando 2007; McClure 2018; Nohlert 2013; Selvamary 2016; Severson 2009; Stevens 1995; Yahya 2018). The remaining studies were cluster‐RCTs, using either the dental clinic (Andrews 1999; Cohen 1989; Ebbert 2007; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Severson 1998; Virtanen 2015) or the school/college (Gansky 2005; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003) as the unit of randomisation. All but one of the studies were funded by government or university agencies, with three of these being funded through a 'Tobacco Surtax Fund of the State of California' (Gansky 2005; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003). One study reported receiving no funding (Selvamary 2016).

Types of participants and settings

Sixteen studies were conducted in a range of dental settings: twelve studies were conducted in dental clinic settings (Andrews 1999; Cohen 1989; Ebbert 2007; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Hanioka 2010; Lando 2007Nohlert 2013; Severson 1998; Stevens 1995; Virtanen 2015: Yahya 2018); three were in hospital settings (Binnie 2007; Holliday 2019; Selvamary 2016); and one took place in military dental clinics (Severson 2009). Four studies were conducted in non‐dental settings. Three of these involved dental professionals providing interventions to athletes within high school or college settings (Gansky 2005; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003) as a major part of the intervention. One study involved a 'quit line' (telephone help line) counsellor providing oral health promotion alongside quit line counselling (McClure 2018). Although this study did not involve dental professionals directly, we decided to include it, as dental professionals developed this intervention and trained the quit line counsellors to use it. However, we do report the results of McClure 2018 separately.

Nine studies targeted only cigarette smokers (Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Ebbert 2007; Hanioka 2010; Holliday 2019; Lando 2007; McClure 2018; Nohlert 2013; Yahya 2018). Five studies targeted smokeless tobacco users only (Gansky 2005; Severson 2009; Stevens 1995; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003). Three studies included smokeless tobacco users as well as cigarette smokers and assessed abstinence from all tobacco (Gordon 2010a; Selvamary 2016; Virtanen 2015). One study targeted both cigarette smokers and smokeless tobacco users; the data for the two types of participant were reported separately and are treated in this review as two studies, with Severson 1998 covering smokers and Andrews 1999 covering smokeless tobacco users. Gordon 2010b included sole smokeless tobacco users and dual users of smoked and chewed tobacco, but only included sole smokers in the analysis because the proportion of sole smokeless tobacco users and dual users was low (2.4% and 1% respectively).

The majority of the studies did not select participants based on motivation to quit, except for three (Hanioka 2010 recruited participants willing to stop within one month; Selvamary 2016 recruited participants referred to a tobacco cessation programme; McClure 2018 recruited quit line callers).

Types of interventions

Table 2 provides a brief overview of the nature of cessation interventions used in the included studies. Interventions in the dental setting involved: brief advice plus quit line referral (Ebbert 2007; Virtanen 2015; Yahya 2018); brief advice plus motivational interviewing (Lando 2007); brief advice plus video‐based cessation programme with telephone follow‐up (Andrews 1999; Severson 1998; Severson 2009; Stevens 1995); health education, including pamphlet and video plus cognitive behavioural therapy (Selvamary 2016); counselling using the '5As' ('Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange') plus NRT (Binnie 2007); 5As, NRT and population‐specific printed material (Gordon 2010b); 5As, discussion about pharmacotherapy and referral as needed (Gordon 2010a); counselling with four steps and booklet provision, plus nicotine replacement therapy (Cohen 1989); '3As' ('Ask, Advise, Act'), offer of referral and e‐cigarette starter kit (Holliday 2019); high‐intensity intervention (defined as five or more personal contacts) delivered with some form of NRT (Hanioka 2010); or without NRT, but with pharmacological advice (Nohlert 2013).

The three studies conducted in school/college settings involved a dental professional providing an examination and advice, and supplementing this with a range of components (e.g. follow‐up by the dental professional or athletic trainer, videos, newsletters and peer‐led support) (Gansky 2005; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003). One study involved a quit line counsellor providing oral health promotion alongside quit‐line counselling (McClure 2018).

A range of comparator groups were used. Three studies had no contact or non‐intervention comparators (Gansky 2005; Hanioka 2010; Walsh 1999). Six studies had 'usual care' comparators but did not provide any further details about what this entailed (Andrews 1999; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Severson 1998; Stevens 1995; Walsh 2003). Seven studies provided 'very brief advice' or 'brief advice' interventions as comparators (Binnie 2007; Ebbert 2007; Holliday 2019; Lando 2007; Severson 2009; Virtanen 2015; Yahya 2018). Three studies used less treatment active controls (McClure 2018; Nohlert 2013; Selvamary 2016). No comparator groups received pharmacotherapy.

Types of outcome measures

A wide range of abstinence definitions were used, either point prevalence (single or multiple) or continuous (sustained or prolonged abstinence). Biochemical validation of abstinence was used in six studies (Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Holliday 2019; Hanioka 2010; Selvamary 2016; Yahya 2018) with one study reportedly doing this on an 8% random sample (Walsh 2003). The strictest definition of abstinence was continuous smoking abstinence, with dropouts (or those with missing data) considered to have continued smoking or relapsed; this was used in three studies (Hanioka 2010; Holliday 2019; Selvamary 2016)

Two studies reported on oral health outcomes (Holliday 2019; McClure 2018). One of these studies reported whether or not participants received dental care in the last six months (McClure 2018), and the other study reported periodontal probing pocket depths, bleeding on probing, oral health‐related quality of life and a clinical oral dryness score (Holliday 2019). One study reported on adverse events (Holliday 2019).

In the majority of studies, participants were followed for a maximum of six months (Ebbert 2007; Holliday 2019; McClure 2018; Selvamary 2016; Severson 2009; Virtanen 2015; Yahya 2018) or 12 months (Andrews 1999; Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Gansky 2005; Gordon 2010a; Hanioka 2007; Lando 2007; Severson 1998; Stevens 1995; Walsh 1999). Other follow‐up periods included seven and one‐half months (Gordon 2010b), 24 months (Walsh 2003), and five to eight years (Nohlert 2013).

Excluded studies

We listed 81 studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table with reasons provided. This combines 44 excluded studies from the previous version of this review (Carr 2012) with 37 excluded studies from this update. The most common reasons for exclusion were that the studies did not report appropriate smoking cessation outcomes, they followed participants for less than six months, or they were not RCTs.

Six ongoing studies are listed in the Ongoing studies table (the previous version of this review listed no ongoing studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

As demonstrated in the 'Risk of bias' summary figure (Figure 2), it was often difficult to assess bias using our criteria because there was insufficient information reported in the publications. For summary risk of bias judgements, as described in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies, we were able to judge that these conferred a low summary risk of bias for three studies (Holliday 2019; McClure 2018; Virtanen 2015). We assessed sixteen studies as being at high risk of bias (Andrews 1999; Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Ebbert 2007; Gansky 2005; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Lando 2007; Nohlert 2013; Selvamary 2016; Severson 1998; Severson 2009; Stevens 1995; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003; Yahya 2018), with the remaining study assessed to be at unclear risk of bias (Hanioka 2010).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Rationale for 'Risk of bias' judgements for individual studies can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

Allocation

We assessed selection bias by investigating methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment for each study. We rated nine studies at low risk of selection bias, with details being provided of an adequate sequence generation process and steps to ensure allocation concealment (Binnie 2007; Gansky 2005; Holliday 2019; McClure 2018; Nohlert 2013; Selvamary 2016; Severson 2009; Virtanen 2015; Walsh 1999). We rated two studies at high risk of selection bias (Lando 2007; Stevens 1995): one of these studies had both inadequate sequence generation processes and inadequate allocation concealment (Stevens 1995); the other provided details of adequate sequence generation but not allocation concealment (Lando 2007). The other studies had insufficient details to judge the risk of selection bias and were rated as being at unclear risk of bias (Andrews 1999; Cohen 1989; Ebbert 2007; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Hanioka 2010; Severson 1998; Walsh 2003; Yahya 2018).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed attrition bias by investigating the number of participants not followed up in each study according to the 'Risk of bias' guidance produced by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. We rated twelve studies at low risk of attrition bias (Andrews 1999; Gansky 2005; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Hanioka 2010; Holliday 2019; McClure 2018; Nohlert 2013; Severson 2009; Virtanen 2015; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003) meaning the overall number lost to follow‐up was clearly reported to be no more than 50%, and the difference in loss to follow‐up between groups was no greater than 20%. We rated five studies to be at high risk of bias (Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Selvamary 2016; Stevens 1995; Yahya 2018) because overall loss to follow‐up was more than 50%. Three studies were rated to be at unclear risk of attrition bias (Ebbert 2007; Lando 2007; Severson 1998) because the number lost to follow‐up in each group and/or sensitivity analyses were not reported.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

We assessed detection bias by investigating blinding of the outcome measure, as recommended in the 'Risk of bias' guidance produced by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. Eight studies were rated to be at low risk of detection bias (Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Hanioka 2010; Holliday 2019; McClure 2018; Selvamary 2016; Virtanen 2015; Yahya 2018), because smoking status was measured objectively (i.e. biochemical validation) (Binnie 2007; Cohen 1989; Hanioka 2010; Holliday 2019; Selvamary 2016; Yahya 2018) or because although smoking status was not measured objectively, the study groups received similar amounts of face‐to‐face (or phone/text message) contact (McClure 2018; Virtanen 2015). We rated twelve studies to be at high risk of detection bias (Andrews 1999; Ebbert 2007; Gansky 2005; Gordon 2010a; Gordon 2010b; Lando 2007; Nohlert 2013; Severson 1998; Severson 2009; Stevens 1995; Walsh 1999; Walsh 2003) because smoking status was self‐reported and groups received different levels of contact.

Other potential sources of bias

We identified other potential sources of bias in Gansky 2005, where there was contamination bias from spillover of the cessation intervention to the control group (i.e. contamination of the control group with intervention information).

We planned to assess publication bias using a funnel plot. However, none of our analyses contained ten studies or more, the threshold set in our pre‐specified methods.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Tobacco‐use cessation

Single session behavioural support

We pooled seven studies (n = 6328) testing behavioural interventions comprising a single session with a dental professional compared with usual care, brief advice, very brief advice, or less active treatment control. We found evidence of benefit from behavioural support (RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.34; Analysis 1.1), though there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 66%), which we could not explain through subgroup analysis. We conducted two subgroup analyses, one dividing studies by the intensity of control (usual care control, or brief or very brief advice control) for which we found no evidence of subgroup difference (P = 0.26; I2 = 21%), and one dividing studies by whether they included participants using smoked tobacco, smokeless tobacco, or both, for which we found no evidence of subgroup difference (P = 0.91; I2 = 0%; Analysis 5.1). We were unable to subgroup by level of motivation to quit, as no studies had recruitment methods that selected for motivation. We were unable to conduct our planned sensitivity analysis as all studies were at high risk of bias.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Single‐session behavioural support (1 session) versus control: subgrouped by comparator, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Single‐session behavioural support (1 session) versus control: subgrouped by tobacco‐use type, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

Multi‐session behavioural support

We pooled four studies (n = 2639) testing behavioural interventions comprising more than one session with a dental professional compared with usual care, brief, or very brief advice. We found evidence of benefit from behavioural support (RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.11; Analysis 2.1), though there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 61%), which we could not explain through subgroup analysis. We conducted three subgroup analyses. First, we divided studies by the intensity of control (usual care control, or brief or very brief advice control) and found no evidence of subgroup difference (P = 0.87; I2 = 0%). Second, we divided studies by whether they included participants using smoked tobacco, smokeless tobacco, or both; we found no evidence of subgroup difference (P = 0.09; I2 = 57.6%; Analysis 6.1). Third, we divided studies by likely level of motivation to quit as indicated by the method of recruitment (not selected for motivation; more likely motivated); we found evidence of subgroup difference (P = 0.05; I2 = 74.6%; Analysis 7.1), but only one study fell into the 'more likely motivated' subgroup, and in both cases the subgroup effect estimates favoured the intervention. We were unable to conduct our planned sensitivity analysis as only one study was not at high risk of bias (Virtanen 2015).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Multi‐session behavioural support (> 1 session) versus control: subgrouped by comparator, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Multi‐session behavioural support (> 1 session) versus control: subgrouped by tobacco‐use type, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Multi‐session behavioural support (> 1 session) versus control: subgrouped by motivation, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

Behavioural support plus pharmacotherapy

We pooled four studies (n = 1221) testing behavioural interventions from a dental professional combined with the provision of NRT or e‐cigarettes, compared with no intervention, usual care, brief advice, or very brief advice, provided without NRT or e‐cigarettes. We found evidence of benefit from behavioural support and nicotine treatment (RR 2.76, 95% CI 1.58 to 4.82; Analysis 3.1), with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). As a result, our subgrouping by the intensity of the control group (usual care control, or brief or very brief advice control) found no evidence of a subgroup difference (P = 0.81; I2 = 0%), as did our subgrouping by likely level of motivation to quit (P = 0.98; I2 = 0%; Analysis 8.1). We were unable to subgroup by tobacco‐use type, as all studies were in smoked tobacco users. A sensitivity analysis removing two studies at high risk of bias still detected a benefit of behavioural support plus nicotine treatment (RR 2.86, 95% CI 1.14 to 7.18; I2 = 0%; two studies; n = 133). We also performed sensitivity analyses removing one study (Hanioka 2010) where participants received multiple sessions with a dental professional (RR 2.75, 95% CI 11.45 to 5.20; I2 = 0%; three studies; n = 1165), and removing the one study (Holliday 2019) that provided e‐cigarettes rather than NRT (RR 2.72, 95% CI 1.49 to 4.95; I2 = 0%; three studies; n = 1141). Both analyses still detected a similar benefit.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus control: subgrouped by comparator, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus control: subgrouped by motivation, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

Behavioural support outside of a dental setting

We pooled three studies (n = 1020) testing the effect of multiple‐session behavioural interventions from dental professionals delivered in a high school or college instead of a dental setting. We did not find evidence of a benefit of the intervention (RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.65; Analysis 4.1). However, there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 83%). We were unable to subgroup by tobacco use type, as all studies were in smokeless tobacco users, and we were unable to subgroup by level of motivation to quit because no studies had recruitment methods that selected for motivation. We were unable to conduct our planned sensitivity analysis as all studies were at high risk of bias. We conducted a sensitivity analysis by removing Gansky 2005 because while the intervention comprised multiple sessions, only one was with a dental professional. Removing this study did change the result of the analysis, both detecting a benefit and removing the heterogeneity (RR 2.01, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.87; I2 = 0%; two studies; n = 499).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Behavioural support from dental professional at high school/college versus usual care/no intervention, Outcome 1: Abstinence at 6+ months

We excluded McClure 2018 from this analysis because unlike the other non‐dental practice setting studies, this study was conducted over a smoking quit‐ line. Considered alone, this study did not detect a benefit of the intervention (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.38; n = 718).

Adverse events

One study delivering an e‐cigarette intervention to smokers with periodontitis reported adverse events (Holliday 2019). Forty‐four percent of study participants reported an adverse event over the six months of the study, with 56 adverse events occurring in 35 participants. Most of the adverse events (toothache, dentine hypersensitivity, tooth loss and abscesses) were likely to be associated with the sequelae of severe periodontitis and were comparable across the study groups (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.32; n = 80; Analysis 3.2.1). Five participants experienced adverse events less likely attributable to periodontitis (mouth ulceration or intra‐oral soft tissue soreness), with all of these occurring in the intervention group (RR 11.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 192.56; n = 80; Analysis 3.2.2). The authors discussed that these could have been associated with the e‐cigarette intervention (other forms of orally administered NRT have been associated with mouth soreness and ulceration; Hartmann‐Boyce 2018) or could be the result of the higher quit rate in the intervention group (mouth ulcers are a common result of stopping smoking, affecting two in five quitters; McRobbie 2004). The study reported no serious adverse events.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus control: subgrouped by comparator, Outcome 2: Adverse events

Oral health outcomes

It was not possible to perform a quantitative synthesis of the oral health outcomes since only one study reported them in detail (Holliday 2019), with one other study reporting whether participants had received dental care in the previous six months (McClure 2018). Holliday 2019 reported mean change from baseline to six months for mean probing pocket depths (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.18; n = 58; Analysis 3.3.1), percentage of sites with pocket depths ≥ 5 mm (MD ‐2.20, 95% CI ‐9.07 to 4.67; n = 58; Analysis 3.3.2), percentage bleeding on probing (MD 4.10, 95% CI ‐2.87 to 11.07; n = 58; Analysis 3.3.3), oral dryness measured by the clinical oral dryness score (MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 1.15; n = 58; Analysis 3.3.4), and an oral health quality of life measure (OHQoL‐UK) (MD 1.40, 95% CI ‐5.90 to 8.70; n = 58; Analysis 3.4). In summary, participants showed improvements in all the oral health measures; improvements were similar in both the control and intervention groups. However, the study did not have sufficient power to detect differences between study arms.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus control: subgrouped by comparator, Outcome 3: Oral health outcomes

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus control: subgrouped by comparator, Outcome 4: OHQoL‐UK

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review provides evidence from 20 studies. Over 11,000 participants from 18 studies contributed to the meta‐analyses for the primary outcome of tobacco abstinence at six months or longer. We found evidence of very low to moderate certainty that dental professionals can successfully deliver tobacco cessation interventions to increase the chances of achieving long‐term tobacco‐use abstinence. These interventions included single and multi‐session behavioural support, and behavioural support with the addition of nicotine replacement therapy or e‐cigarettes. We did not find a benefit of multi‐session interventions delivered by dental professionals outside of a dental setting. However, this finding should be treated with caution, as the removal of one of the three studies, where only part of the intervention was delivered by a dental professional, resulted in a substantial change in the interpretation of results.

Where there were sufficient data available, we conducted subgroup analyses to attempt to explain heterogeneity in the results. We subgrouped by the comparator intervention received, whether studies included smoked or smokeless tobacco users, and the likely level of motivation to quit among participants, as indicated by the studies’ methods of participant recruitment. Only once did these analyses detect a subgroup difference; this should be treated with caution, as one of the subgroups only included one study.

Two studies reported on oral health outcomes, and only one of these reported findings in detail, meaning that we were not able to complete a quantitative synthesis of these data. The data from this single study showed that the control and intervention groups had similar improvements in oral health over the course of the study. Only one study reported on adverse events. Most of these adverse events appeared to be related to periodontitis or periodontal therapy. Some of the adverse events, such as mouth ulceration or soreness, could have been related to the nicotine in the intervention or as a common side‐effect of tobacco‐use cessation (McRobbie 2004).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The majority of the studies (13 studies) were undertaken in the USA, with two undertaken in each of the UK and Sweden, and one in each of Japan, Malaysia and India. Given the significant differences in the healthcare systems and socioeconomic status in these different countries, this limits the generalisability of the results.

Although studies often described the practical details of how the interventions were delivered (e.g. telephone versus face‐to‐face, number of sessions, etc.) the details about specific behaviour change techniques used were often lacking. A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis of 142 smoking cessation trials found that reporting of the interventions was variable and incomplete (de Bruin 2020). Future trials should include comprehensive descriptions of the interventions delivered.

Quality of the evidence

We judged most studies (16 studies) to be at high risk of bias for a variety of reasons. The most common was a high risk of detection bias because tobacco‐use status was self‐reported and study groups received different levels of face‐to‐face contact. One study was at unclear risk of bias and three were at low risk of bias. The low risk of bias studies were all published in the last five years, potentially indicating an improvement in study conduct and reporting.

For the primary abstinence outcome, we assessed the certainty of the evidence for each of our analyses, using the GRADE system (Schünemann 2017). We judged the evidence for behavioural interventions comprising more than one session with a dental professional and behavioural interventions comprising a single session with a dental professional to be of very low certainty. In both cases, we downgraded the evidence due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision. We judged the evidence for behavioural interventions from a dental professional combined with the provision of NRT or e‐cigarettes to be of moderate certainty. We downgraded the evidence because of imprecision. We judged the evidence for multiple‐session behavioural interventions from dental professionals delivered in a high school or college instead of a dental setting to be of very low certainty. We downgraded the evidence because of risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision. Given the very low‐certainty evidence, future research is likely to substantially affect the conclusions of this review.

Subgroup analyses explored the impact of the varied comparator interventions on the pooled estimate for tobacco abstinence, but they did not explain the substantial heterogeneity we found in our analyses of single‐session and multi‐session behavioural interventions. However, it is worth noting that imprecise reporting in many studies concerning what treatment is involved in usual care may mean that some studies are misclassified in these subgroup analyses.

Potential biases in the review process

Cochrane methods are designed to minimise reviewer bias where possible. For example, at least two review authors independently conducted study selection, data extraction, and 'Risk of bias' assessments. A key possible limitation of the review is that we may have failed to identify all relevant research for inclusion in the review. However, given the nature of Cochrane methods, we are confident that any failures in identification of studies for inclusion will not be systematic, and therefore should not have a significant impact on the validity of our results.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We chose not to include interventions aimed at the training or provision of an educational intervention of or for dental health professionals. We felt that the inclusion of these studies would not address the objective of the review, which was to assess the effectiveness of the interventions and not the training of providers. The training of health professionals in smoking cessation is the topic of another Cochrane Review (Carson 2012). However, several studies are worthy of brief mention. Houston 2013 targeted dental providers through an internet‐based education system without finding a benefit for quit rates. Ray 2014 evaluated an electronic referral system for an online cessation resource, and while fewer referrals were made in the electronic referral group compared with those receiving paper‐based referrals, nearly four times as many people referred from the intervention group registered with the programme, and subsequent quit rates were four times higher. Ahmadian 2017 compared role play and problem‐based learning for teaching dental students tobacco cessation counselling skills and concluded that while both methods led to improved knowledge, attitude, and skills compared with before training, they could find no difference in quit rates between these methods. Albert 2004 evaluated the feasibility of face‐to‐face educational outreach visits to train dentists in tobacco cessation interventions; they noted significant barriers to implementing this. Walsh 2010 compared high‐ and low‐intensity training with or without reimbursement on dentist's attitudes and behaviours and found that while dentists in all intervention groups showed improvement in Assess, Assist and Arrange behaviours, participants whose dentists had received incentives were more likely to quit.

The findings of this review are in keeping with those of other related reviews. The effect sizes seen in our study are similar to those seen when medical physicians delivered smoking cessation advice (Stead 2013; RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.94) . When dental studies combined a method of behavioural support with nicotine treatment, we saw a larger treatment effect, which is in keeping with the evidence from other reviews (Cahill 2013; Hartmann‐Boyce 2019), although the numbers cannot be compared directly. Stead 2016 reviewed pharmacotherapy combined with behavioural treatment and found an RR of 1.83 (95% CI 1.68 to 1.98), which while being lower than the result seen in this review (RR 2.76, 95% CI 1.58 to 4.82), still agrees that there is a benefit of this kind of intervention.

Only one of the studies included in this review reported on the oral health response to smoking cessation (Holliday 2019). They did not detect a difference between control and intervention groups, but this was a small study and not powered to detect this outcome. Previous reviews on this topic have found that smoking cessation offered additional beneficial effects following non‐surgical periodontal therapy (Chambrone 2013).

Adverse events were reported by one study (Holliday 2019), with intra‐oral soreness and ulceration being associated with an e‐cigarette intervention group. Previous Cochrane Reviews on e‐cigarettes and NRT have reported similar localised irritation at the site of administration (Hartmann‐Boyce 2018; Hartmann‐Boyce 2020).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is very low‐certainty evidence that behavioural tobacco cessation interventions, delivered by dental professionals, can increase quit rates.

There is moderate‐certainty evidence that behavioural interventions combined with nicotine replacement, provided by dental professionals, may increase tobacco abstinence rates in cigarette smokers.

Implications for research.

Further well designed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of smoking cessation interventions in dental settings are indicated. The evidence that pharmacological interventions delivered by dental professionals may be a particularly effective intervention suggests that future studies should explore this further. In particular, future studies should use biochemical validation of abstinence so as to preclude the risk of detection bias. Reporting more detail about specific behaviour change techniques used in study interventions would also help illuminate which components such interventions should contain. There has been very limited attention to cost‐effectiveness to date, and as the evidence regarding effectiveness grows, this will become more important to evaluate.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 February 2021 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Search updated February 2020, with new studies incorporated and methods and text updated to conform to new Cochrane standards |

| 21 February 2020 | New search has been performed | Title updated to reflect that not all studies are in dental settings. Search updated to February 2020. Five new studies included. Text and methodology updated to comply with the new editorial and methodological standards for Cochrane reviews ‐ see Differences between protocol and review for further details. Adverse events and oral health outcomes added and objectives restructured to account for this. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2005 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 April 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Conclusions updated to include interventions among cigarette smokers as well as among smokeless tobacco users. New included studies increase strength of effect. |

| 10 April 2012 | New search has been performed | 8 new included studies added, evaluating interventions among cigarette smokers. |

| 22 February 2012 | New search has been performed | Updated search to November 2011 |

| 29 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 5 September 2006 | New search has been performed | Updated for issue 1 2007. No new studies identified. Two studies reviewed and added to excluded studies list. |

Acknowledgements

Due to competing interests for one included study (Holliday 2019), the data extraction and 'Risk of bias' assessment were completed by BH and Manás Dave, Academic Clinical Fellow in Oral Pathology, Manchester University, UK.

We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, specifically Nicola Lindson, who provided expert guidance during the review process. Our thanks to Dr Thomas James Lamont, University of Dundee, Scotland, and to another reviewer for conducting peer review, and to Sandra Wilcox for consumer review.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via a Clinical Lectureship (RH), Academic Clinical Fellowship (BH) and a Cochrane Infrastructure and Cochrane Programme grant funding to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy: Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register

1. dentist*:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 2. dental*:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 3. hygienist*:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 4. oral health:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 5. #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 6. dentist*:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 7. dental*:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 8. hygienist*:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 9. oral health:MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY,TI,AB 10. #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 11. #5 AND #10 AND INREGISTER

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Single‐session behavioural support (1 session) versus control: subgrouped by comparator.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Abstinence at 6+ months | 4 | 6328 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [1.01, 3.41] |

| 1.1.1 Usual care control (not specified) | 2 | 5523 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.75, 2.49] |

| 1.1.2 Very brief or brief advice control | 2 | 805 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.56 [1.03, 6.33] |

Comparison 2. Multi‐session behavioural support (> 1 session) versus control: subgrouped by comparator.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Abstinence at 6+ months | 7 | 2639 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.90 [1.17, 3.11] |

| 2.1.1 Usual care control (not specified) | 2 | 1147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.03 [0.99, 4.17] |

| 2.1.2 Very brief or brief advice/less active treatment control | 5 | 1492 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [0.88, 3.93] |

Comparison 3. Behavioural intervention + NRT/e‐cigarette versus control: subgrouped by comparator.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Abstinence at 6+ months | 4 | 1221 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.76 [1.58, 4.82] |

| 3.1.1 No intervention/usual care control | 2 | 1025 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.86 [1.51, 5.44] |