Abstract

Background

People with liver cirrhosis who have had one episode of variceal bleeding are at risk for repeated episodes of bleeding. Endoscopic intervention and portosystemic shunts are used to prevent further bleeding, but there is no consensus as to which approach is preferable.

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of shunts (surgical shunts (total shunt (TS), distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS), or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)) versus endoscopic intervention (endoscopic sclerotherapy or banding, or both) with or without medical treatment (non‐selective beta blockers or nitrates, or both) for prevention of variceal rebleeding in people with liver cirrhosis.

Search methods

We searched the CHBG Controlled Trials Register; CENTRAL, in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE Ovid; Embase Ovid; LILACS (Bireme); Science Citation Index ‐ Expanded (Web of Science); and Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (Web of Science); as well as conference proceedings and the references of trials identified until 22 June 2020. We contacted study investigators and industry researchers.

Selection criteria

Randomised clinical trials comparing shunts versus endoscopic interventions with or without medical treatment in people with cirrhosis who had recovered from a variceal haemorrhage.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. When possible, we collected data to allow intention‐to‐treat analysis. For each outcome, we estimated a meta‐analysed estimate of treatment effect across trials (risk ratio for binary outcomes). We used random‐effects model meta‐analysis as our main analysis and as a means of presenting results. We reported differences in means for continuous outcomes without a meta‐analytic estimate due to high variability in their assessment among all trials. We assessed the certainty of evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We identified 27 randomised trials with 1828 participants. Three trials assessed TSs, five assessed DSRSs, and 19 trials assessed TIPSs. The endoscopic intervention was sclerotherapy in 16 trials, band ligation in eight trials, and a combination of band ligation and either sclerotherapy or glue injection in three trials. In eight trials, endoscopy was combined with beta blockers (in one trial plus isosorbide mononitrate). We judged all trials to be at high risk of bias. We assessed the certainty of evidence for all the outcome review results as very low (i.e. the true effects of the results are likely to be substantially different from the results of estimated effects). The very low evidence grading is due to the overall high risk of bias for all trials, and to imprecision and publication bias for some outcomes. Therefore, we are very uncertain whether portosystemic shunts versus endoscopy interventions with or without medical treatment have effects on all‐cause mortality (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.13; 1828 participants; 27 trials), on rebleeding (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.50; 1769 participants; 26 trials), on mortality due to rebleeding (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.76; 1779 participants; 26 trials), and on occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy, both acute (RR 1.60, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.92; 1649 participants; 24 trials) and chronic (RR 2.51, 95% CI 1.38 to 4.55; 956 participants; 13 trials). No data were available regarding health‐related quality of life.

Analysing each modality of portosystemic shunts individually (i.e. TS, DSRS, and TIPS) versus endoscopic interventions with or without medical treatment, we are very uncertain if each type of shunt has effect on all‐cause mortality: TS, RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.13; 164 participants; 3 trials; DSRS, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.33; 352 participants; 4 trials; and TIPS, RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.31; 1312 participants; 19 trial; on rebleeding: TS, RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.56; 127 participants; 2 trials; DSRS, RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.65; 330 participants; 5 trials; and TIPS, RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.55; 1312 participants; 19 trials; on mortality due to rebleeding: TS, RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.96; 164 participants; 3 trials; DSRS, RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.74; 352 participants; 5 trials; and TIPS, RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.04; 1263 participants; 18 trials; on acute hepatic encephalopathy: TS, RR 1.66, 95% CI 0.70 to 3.92; 115 participants; 2 trials; DSRS, RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.94 to 3.08; 287 participants; 4 trials, TIPS, RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.99; 1247 participants; 18 trials; and chronic hepatic encephalopathy: TS, Fisher's exact test P = 0.11; 69 participants; 1 trial; DSRS, RR 4.87, 95% CI 1.46 to 16.23; 170 participants; 2 trials; and TIPS, RR 1.88, 95% CI 0.93 to 3.80; 717 participants; 10 trials.

The proportion of participants with shunt occlusion or dysfunction was overall 37% (95% CI 33% to 40%). It was 3% (95% CI 0.8% to 10%) following TS, 7% (95% CI 3% to 13%) following DSRS, and 47.1% (95% CI 43% to 51%) following TIPS. Shunt dysfunction in trials utilising polytetrafluoroethylene‐covered stents was 17% (95% CI 11% to 24%).

Length of inpatient hospital stay and cost were not comparable across trials.

Funding was unclear in 16 trials; 11 trials were funded by government, local hospitals, or universities.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence on whether portosystemic shunts versus endoscopy interventions with or without medical treatment in people with cirrhosis and previous hypertensive portal bleeding have little or no effect on all‐cause mortality is very uncertain. Evidence on whether portosystemic shunts may reduce bleeding and mortality due to bleeding while increasing hepatic encephalopathy is also very uncertain. We need properly conducted trials to assess effects of these interventions not only on assessed outcomes, but also on quality of life, costs, and length of hospital stay.

Keywords: Humans; Bias; Cause of Death; Endoscopy; Endoscopy/methods; Esophageal and Gastric Varices; Esophageal and Gastric Varices/prevention & control; Esophageal and Gastric Varices/therapy; Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage; Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage/epidemiology; Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage/prevention & control; Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage/therapy; Hepatic Encephalopathy; Hepatic Encephalopathy/epidemiology; Hepatic Encephalopathy/etiology; Intention to Treat Analysis; Liver Cirrhosis; Liver Cirrhosis/complications; Portasystemic Shunt, Surgical; Portasystemic Shunt, Surgical/adverse effects; Portasystemic Shunt, Surgical/methods; Portasystemic Shunt, Transjugular Intrahepatic; Portasystemic Shunt, Transjugular Intrahepatic/adverse effects; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Secondary Prevention; Splenorenal Shunt, Surgical; Splenorenal Shunt, Surgical/adverse effects

Plain language summary

Shunts compared with endoscopic intervention to prevent further episodes of variceal bleeding in people with liver cirrhosis

Background

People with scarring of the liver (cirrhosis) may develop high pressure in the portal vein (the vein that carries blood from the gut to the liver). This high pressure results in abnormally dilated veins (varices) in the gullet (oesophagus), in the stomach, or in the intestine, which may cause life‐threatening bleeding. People who have bled once are at high risk of bleeding in the future, so it is important to prevent further bleeding episodes in these people. Different treatment options are available to prevent further bleeding. One option is endoscopic treatment, which uses a flexible camera to examine the affected area and to seal varices with elastic bands, or to inject the varices with a substance to close the veins. A second option is 'shunting', which diverts blood flow away from the problematic vein, reducing pressure and thereby reducing the chance of bleeding. There are three main types of shunts: total shunt, distal splenorenal shunt, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Total shunt and distal splenorenal shunt were more commonly used in the past and require invasive surgical procedures. TIPS are now much more commonly used, as they do not require invasive surgery.

Review question

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to compare shunts versus endoscopic treatments with or without further medications in people with liver cirrhosis who had previously bled from varices, by collecting and analysing all relevant studies in this topic area and by reviewing the evidence.

Study characteristics

In June 2020, we reviewed the evidence. We found 27 randomised clinical trials (trials where participants are allocated to groups at random) involving 1828 participants. Three trials investigated total shunt (164 participants); five trials investigated distal splenorenal shunt (352 participants); and 19 trials investigated transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (1312 participants). The source of funding was unclear in 16 trials. Eleven trials were funded by the government or received grants from local hospitals or universities.

Results

Evidence suggesting whether shunt treatments compared with endoscopic treatments with or without further medications alter the overall risk of death from any cause (all‐cause mortality), reduce the risk of bleeding from varices, or reduce the risk of dying from bleeding varices (death due to variceal bleeding) was very uncertain.

Evidence that people treated with shunts compared with endoscopic treatments with or without further medications are at increased risk of acute hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction associated with liver disease) or chronic hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction that occurs repeatedly or does not fully improve) was also very uncertain.

We could not conclude with certainty whether people treated with shunt stayed in hospital longer than people treated with endoscopy with or without further medications, or which treatment was more expensive, as we were not confident that combining the results from different studies would produce a meaningful result. No trials reported on the impact of treatments on patient quality of life.

Risk of bias

The results of our analyses must be interpreted with caution due to concerns about the quality of included trials. Weaknesses in the design of these studies could influence results, making them potentially misleading.

Conclusions

We cannot say for sure that portosystemic shunts when compared with endoscopic treatment associated sometimes with medical treatment modify the risk of overall death (all‐cause mortality), reduce the risk of repeated episodes of bleeding, or increase the risk of developing hepatic encephalopathy. We need properly conducted trials assessing important outcomes for people with cirrhosis and health providers.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Portosystemic shunts compared with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis.

| Portosystemic shunts compared with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with cirrhosis and with previous oesophagogastric variceal bleeding Setting: hospital; tertiary referral centres Intervention: shunt intervention (total shunt (TS), distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS), or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)) Comparison: endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment | Corresponding risk with shunts | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 32.9 months (range 11.7 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) | 1828 (27 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa |

||

| 288 per 1000 | 286 per 1000 (248 to 325) | |||||

|

Rebleeding Follow‐up: 33.8 months (range 13.5 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.40 (0.33 to 0.50) | 1769 (26 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | ||

| 432 per 1000 | 173 per 1000 (143 to 216) | |||||

| Health‐related quality of life | No data available | No data | ||||

|

Mortality due to rebleeding Follow‐up: 33.5 months (range 11.7 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.51 (0.34 to 0.76) | 1779 (26 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

||

| 95 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (32 to 72) | |||||

|

Acute hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 33.8 months (range 13.5 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 1.60 (1.33 to 1.92) | 1649 (24 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | ||

| 185 per 1000 | 296 per 1000 (246 to 355) | |||||

|

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 28.5 months (range 13.5 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 2.51 (1.38 to 4.55) | 956 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe | ||

| 27 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (37 to 123) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (risk of the intervention group) (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OIS: optimal information size; RCT: randomised clinical trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); publication bias (‐1 level). bDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); publication bias (‐1 level). cDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: optimal information size (OIS) as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level). dDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level). eDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level).

Summary of findings 2. Total shunt compared with endoscopic intervention for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis.

| Total shunt compared with endoscopic intervention for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with cirrhosis and with previous oesophagogastric variceal bleeding Setting: hospital tertiary care centres Intervention: total shunt Comparison: endoscopic intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment | Corresponding risk with total shunt | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 32.4 months (range 11.7 to 65.1) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.46 (0.19 to 1.13) | 164 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ||

| 198 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (38 to 224) | |||||

|

Rebleeding Follow‐up: 42.8 months (range 20.4 to 65.1) |

Medium risk population | RR 0.28 (0.14 to 0.56) | 127 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | ||

| 435 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (61 to 244) | |||||

| Health‐related quality of life | No data available | No data | ||||

|

Mortality due to rebleeding Follow‐up: 32.4 months (range 11.7 to 65.1) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.25 (0.06 to 0.96) | 164 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

||

| 136 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (8 to 131) | |||||

|

Acute hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 42.8 months (range 20.4 to 65.1) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 1.66 (0.70 to 3.92) | 115 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | ||

| 123 per 1000 | 204 per 1000 (86 to 482) | |||||

|

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 20.4 months |

69 (1 RCT) | There was a single trial with 3/34 events in total shunt group and 0/35 in endoscopy with or without drugs group | ||||

| The corresponding risk (risk of the intervention group) (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised clinical trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: optimal information size (OIS) as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level). bDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level). cDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level). dDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met; there were few events and the CI included appreciable benefit and harm (‐2 levels).

Summary of findings 3. Distal splenorenal shunt compared with endoscopic intervention for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis.

| Distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS) compared with endoscopic intervention for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with cirrhosis and with previous oesophagogastric variceal bleeding Setting: hospital tertiary care centres Intervention: DSRS Comparison: endoscopic intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk with endoscopic intervention | Corresponding risk with distal splenorenal shunt | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 68.6 months (range 27.1 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.93 (0.65 to 1.33) | 352 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ||

| 469 per 1000 | 436 per 1000 (305 to 624) | |||||

|

Rebleeding Follow‐up: 68.6 months (range 27.1 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.26 (0.11 to 0.65) | 330 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | ||

| 458 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (50 to 298) | |||||

| Health‐related quality of life | No data available | |||||

|

Mortality due to rebleeding Follow‐up: 68.6 months (range 27.1 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.31 (0.13 to 0.74) | 352 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | ||

| 126 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (16 to 93) | |||||

|

Acute hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 68.6 months (range 27.1 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 1.70 (0.94 to 3.08) | 287 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | ||

| 139 per 1000 | 236 per 1000 (131 to 428) | |||||

|

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 62.5 months (range 27.1 to 98) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 2.51 (1.38 to 4.55) | 170 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe | ||

| 27 per 1000 | 68 per 1000 (37 to 123) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (risk of the intervention group) (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised clinical trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: optimal information size (OIS) as calculated by GRADE was not met; (‐1 levels); heterogeneity (‐1 level). bDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); heterogeneity (‐1 level). cDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level). dDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level). eDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 levels).

Summary of findings 4. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis.

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) compared with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment for prevention of rebleeding in people with cirrhosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with cirrhosis with previous oesophagogastric variceal bleeding Setting: tertiary care centres Intervention: TIPS Comparison: endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk with endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment | Corresponding risk with TIPS | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 24.5 months (range 13.5 to 46.2) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 1.10 (0.92 to 1.31) | 1312 (19 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ||

| 252 per 1000 | 277 per 1000 (232 to 330) |

|||||

|

Rebleeding Follow‐up: 24.5 months (range 13.5 to 46.2) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.44 (0.36 to 0.55) | 1312 (19 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | ||

| 425 per 1000 | 187 per 1000 (153 to 234) | |||||

| Health‐related quality of life | No data available | |||||

|

Mortality due to rebleeding Follow‐up: 24.9 months (range 13.5 to 46.2) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 0.65 (0.40 to 1.04) | 1263 (18 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | ||

| 82 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (33 to 85) |

|||||

|

Acute hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 24.5 months (range 13.5 to 46.2) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 1.61 (1.29 to 1.99) | 1247 (18 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | ||

| 201 per 1000 | 324 per 1000 (259 to 400) | |||||

|

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy Follow‐up: 22.5 months (range 13.5 to 46.2) |

Medium‐risk population | RR 1.88 (0.93 to 3.80) | 717 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe | ||

| 28 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (26 to 106) | |||||

| The corresponding risk (risk of the intervention group) (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCT: randomised clinical trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty : We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); optimal information size (OIS) as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level). bDowngraded three levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); publication bias (‐1 level). cDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level). dDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level). eDowngraded four levels because of within‐study risk of bias: all trials were at overall high risk of bias (‐2 levels); imprecision: OIS as calculated by GRADE was not met (‐1 level); publication bias (‐1 level).

Background

Description of the condition

Portal hypertension is a common complication of liver cirrhosis, usually defined as an increase in pressure within the portal venous system. Portal hypertension leads to development of portosystemic collateral vessels, and of these, gastro‐oesophageal varices are the most clinically relevant (Garcia‐Tsao 2007; Cordon 2012). At the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis, around 30% of people with cirrhosis have gastro‐oesophageal varices; 90% of people with cirrhosis will develop varices during their lifetime (D'Amico 2004; Cordon 2012). The presence and extent of varices are related to the severity of cirrhosis, and individuals with decompensated liver cirrhosis are at highest risk (Garcia‐Tsao 2007). Varices are at high risk of rupture, often resulting in catastrophic haemorrhage ― a major cause of death in people with cirrhotic liver disease. Other causes of bleeding related to portal hypertension in cirrhosis are hypertensive gastropathy and, less frequently, duodenopathy or colopathy. Improved treatment protocols have improved survival; however, mortality rates remain at around 15% to 20% for a first bleed (Cabonell 2004). Early and vigorous resuscitation and early endoscopy, preferably in specialist units, are essential for these individuals (Grace 1997; Herrera 2014). However, people who survive their first variceal bleed are at high risk of further episodes of bleeding ('rebleeding'). The risk of variceal rebleeding is up to 60% within one year, with mortality around 33% (Garcia‐Tsao 2007; Bari 2012). Risk factors specifically for rebleeding have not been well defined, and factors linked to the risk of initial bleeding include the size of varices, the appearance of varices (i.e. red wale marks), and variceal pressure (Zhao 2014).

Due to high risk of rebleeding, secondary prophylaxis is required for individuals with a history of variceal haemorrhage.

Many tools have been used to reduce the risk of rebleeding, such as surgical shunts to reduce portal hypertension, endoscopic obliteration of varices, and drugs like beta blockers (EASL 2018). Published guidelines recommend non‐selective beta‐blockers (NSBBs) and endoscopic band ligation (EBL) as preferable first‐line treatment for secondary prevention of variceal haemorrhage for cirrhotic portal hypertension (de Franchis 2015; Garcia‐Tsao 2017; EASL 2018) because combination treatment decreases the probability of rebleeding compared to monotherapy or either EBL or drug treatment. Recommendations are based on recent meta‐analyses showing that combining EBL with NSBBs reduces overall rebleeding, variceal rebleeding, and bleeding‐related mortality versus banding alone (Thiele 2012), and that adding NSBBs to EBL improves survival, whereas adding EBL to NSBBs has no effect on mortality (Puente 2014).

Description of the intervention

Portosystemic shunts represent an alternative approach for reducing portal hypertension and thereby the risk of rupture of varices. The role of portosystemic shunts, above all TIPSs in the last two decades, is usually limited to rescue treatment for acute persistent bleeding or rebleeding despite conventional treatment (i.e. endoscopic intervention and/or medical‐vasoactive drugs) and is limited for secondary prevention of bleeding. Current international guidelines suggest TIPSs for prevention of rebleeding in patients intolerant to beta blockers, or with contraindications to their use and/or concomitant refractory ascites (de Franchis 2015; EASL 2018), or in selected individuals due to patient choice (Tripathi 2015). However, shunting following the first episode of variceal bleeding could provide more effective treatment earlier in a person's disease pathway, potentially avoiding repeated admissions with variceal bleeding, and thereby possibly reducing mortality. In addition, portosystemic shunts confer the further advantage of being a 'once‐only treatment', potentially preventing repeated hospital visits.

Therapeutic portosystemic shunts are artificial conduits connecting the portal and systemic circulation; they may be inserted surgically or via interventional radiology. Shunts may be classified according to their haemodynamic consequences: the total surgical shunt (TS) has no prograde hepatopetal flow through the portal vein and, therefore, all portal blood is diverted into the systemic circulation (Collins 1995). In contrast, selective or partial shunts preserve pre‐existing hepatopetal portal vein flow (Collins 1995). The distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS) is a surgically placed selective shunt that has been associated with improved preservation of liver function and hence lower morbidity as compared to TS, although lower mortality has not been conclusively demonstrated (D'Amico 1995). The selectivity of DSRSs can be further improved if the venous collaterals between the splenic vein and the pancreas are disconnected ‐ an additional procedure that is particularly important for alcoholics (Warren 1986). Since the early 1990s, the radiologically placed transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has grown in popularity (LaBerge 1993). It is inserted radiologically by minimal access and can usually be placed more quickly than a surgical shunt (Brown 1997). In essence, it is a side‐to‐side portosystemic shunt. TIPSs can, however, lead to serious acute and chronic complications and small but significant mortality (Casado 1998). Stenosis and occlusion rates have been reported to exceed 75% at two years in randomised trials using TIPSs (Papatheodoridis 1999), although the use of polytetrafluoroethylene‐coated stents in modern practice greatly reduces rates of stent dysfunction (Bureau 2007).

Endoscopic treatments are well established, and various techniques may be practised. Among these interventions, sclerotherapy represents an approach by which varices are obliterated through injection of sclerosants (such as ethanolamine oleate, polidocanol, sodium morrhuate, or other agents) (Cordon 2012). A further alternative is endoscopic glue injection, whereby tissue adhesives (n‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) or isobutyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate (Bucrylate)) are injected into varices (Cordon 2012) ‐ a technique that is of particular use in the management of gastric varices (Garcia‐Tsao 2007). An alternative is variceal band ligation ('variceal banding'): varices are obliterated by application of elastic bands via endoscopy (Cordon 2012; Tripathi 2015). It is important to note that effective endoscopic intervention generally requires multiple treatments; typically, varices are banded with an interval of one to four weeks until eradication of varices has been achieved (Garcia‐Tsao 2007; Tripathi 2015). Endoscopic intervention does carry risk of complications, such as provocation of further bleeding episodes, oesophageal ulcers, or bacteraemia (Terblanche 1983; McIntyre 1996; Cordon 2012). However, endoscopic techniques are well established, are usually well tolerated, and significantly reduce rates of rebleeding compared with controls (Graham 1981). Current consensus suggests that variceal banding is the endoscopic method of choice (Garcia‐Tsao 2007; de Franchis 2010; Tripathi 2015) because it is more effective and has lower complication rates than sclerotherapy (Laine 1995; Dai 2015).

Endoscopic treatments serve to locally obliterate varices. By obliterating varices, variceal rupture and haemorrhage may be prevented. However, endoscopic treatment alone does not combat portal hypertension; therefore, it does not target the underlying pathophysiology of varices formation (Villanueva 2008). As a result, endoscopic treatment is generally combined with pharmacological treatment, typically long‐term treatment with non‐cardioselective beta blockers (NSBBs), such as propranolol (Bernard 1997, Tripathi 2015), with or without nitrates. Beta blockade acts to reduce portal pressure by decreasing cardiac output (blockade of beta1 receptors), promoting splanchnic vasoconstriction (blockade of beta2 receptors), and reducing blood flow through collateral vessels (Garcia‐Tsao 2007; Villanueva 2008), hence reducing the risk of variceal bleeding. Combining pharmacological and endoscopic treatments has a synergistic effect by targeting both localised and decompressing varices (Bernard 1997;Villanueva 2008;Tripathi 2015).

How the intervention might work

Portosystemic shunts directly target portal hypertension. Portosystemic shunts act to divert blood from the portal circulation to the systemic circulation, decompressing varices and hence preventing rebleeding. By diverting blood flow, portosystemic shunts might provide a more effective treatment option than endoscopy.

Historically, surgical creation of a shunt (e.g. distal splenorenal shunt, portacaval shunt) was performed to control bleeding and prevent recurrent haemorrhage if other methods failed. However, placement of TIPSs has become the preferred intervention in this setting because covered stents have favourable long‐term patency and the risks and morbidity associated with major abdominal surgery are avoided.

Why it is important to do this review

This current review represents an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2006 (Khan 2006), based on a protocol originally published in 1997 (Khan 1997).

As stated above, shunts provide a once‐only treatment modality for prevention of variceal rebleeding and could potentially be more effective than endoscopic treatment for preventing repeated episodes of variceal bleeding. However, portosystemic shunting does have potential drawbacks. Portosystemic shunting, particularly with surgical shunts, represents a more invasive option than endoscopic treatment. Also, by diverting blood flow away from the liver, portosystemic shunts carry increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy, and portosystemic shunts pose a risk for shunt failure or dysfunction (Luca 1999; Papatheodoridis 1999;Burroughs 2002; Garcia‐Tsao 2007). Therefore, it is important to ask whether a case can be made for more widespread use of shunting, and also to assess the relative safety and risk of complications of portosystemic shunting compared with endoscopic treatment.

In one meta‐analysis in Spina 1992a, DSRSs significantly reduced the risk of rebleeding compared to endoscopic sclerotherapy without increasing the risk of chronic hepatic encephalopathy. However, DSRSs did not significantly affect overall death risk. In D'Amico 1995, a comparison of TSs and DSRSs is reported without differences between the two treatments. Several published meta‐analyses have assessed TIPSs versus endoscopic intervention (Luca 1999; Papatheodoridis 1999;Burroughs 2002; Zheng 2008), all showing no differences in mortality, reduction in rebleeding, and increased incidence of hepatic encephalopathy. More recently, a multiple‐treatments meta‐analysis compared TIPSs, endoscopic treatment modalities, pharmacotherapies, and combination treatments (Shi 2013), showing that endoscopic band ligation combined with argon plasma coagulation resulted in the best profile of reduction in rebleeding rate and all‐cause mortality, and TIPSs had the greatest impact on reducing mortality rate due to rebleeding. Further, a 2019 meta‐analysis compared portosystemic shunts (including transjugular portosystemic shunt) to endoscopy, but in this review, authors also included trials utilising emergency shunts to treat active bleeding (Zhou 2019).

In the current work, we examined portosystemic shunts in the elective setting for patients with previous episodes of variceal bleeding. To comprehensively address the question, we have conducted a systematic review to compare shunts (TSs, DSRSs, and TIPSs) versus endoscopic interventions (sclerotherapy or banding, or both) with or without medical treatment for long‐term prophylaxis of rebleeding.

The current update, along with updated Cochrane standards, incorporates new trials (Lo 2007; Ferlitsch 2012; Luo 2015; Holster 2016; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020) and results of updated trials (Santambrogio 2006).

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of shunts (surgical shunts (total shunt (TSs), distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS), or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS

)) versus endoscopic interventions (endoscopic sclerotherapy or banding, or both) with or without medical treatement (non‐selective beta blockers or nitrates, or both) for prevention of variceal rebleeding in people with liver cirrhosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We endeavoured to identify all possible randomised clinical trials (published and unpublished) in which shunts were compared with endoscopic interventions with or without medical treatment.

Types of participants

People known to have cirrhosis who had bled from oesophagogastric varices but had subsequently stabilised (before randomisation), either spontaneously or via non‐surgical approaches, including vasoactive drugs or balloon tamponade, or endoscopic measures, or a combination of any two or three together.

Types of interventions

Surgical shunts (total shunt (TS), distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS), or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)) versus endoscopic interventions (endoscopic sclerotherapy or banding, or both) with or without concomitant long‐term medical treatment (e.g. non‐selective beta‐blockers, nitrates, both).

Types of outcome measures

All outcomes were evaluated at the maximum available follow‐up.

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality, defined as death due to any cause

Rebleeding, defined as a clinically significant episode of bleeding (i.e. requiring transfusion) from oesophagogastric varices or portal hypertensive gastropathy. The diagnosis should ideally have been confirmed by endoscopic examination to distinguish variceal bleeding or bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy from other causes of non‐portal hypertensive gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Health‐related quality of life, as measured by trial authors

Secondary outcomes

Mortality due to rebleeding, defined as death resulting from a further episode of bleeding from oesophagogastric varices or portal hypertensive gastropathy following the primary (index) bleeding

Acute hepatic encephalopathy, defined by classical signs detected on physical examination, signs unequivocally described by participants' relatives, psychometric testing, or electroencephalogram (EEG)

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy, defined by recurrent episodes of acute hepatic encephalopathy or inability of the individual to attain previous level of function because of post‐treatment hepatic encephalopathy

Complications, defined by untoward events reported by trial authors (aside from hepatic encephalopathy, which is reported separately)

Hospital stay, defined by total days spent in hospital when treatments are applied

Cost analysis, defined by actual financial costs of treatment complications of cirrhotic portal hypertension or of complications during the follow‐up period

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (maintained and searched internally by the CHBG Information Specialist via the Cochrane Register of Studies Web; 22 June 2020); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 2), in the Cochrane Library (searched 22 June 2020); MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 22 June 2020); Embase Ovid (1974 to 22 June 2020); Latin American Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS; Bireme; 1982 to 22 June 2020), and Science Citation Index ‐ Expanded (Web of Science; 1900 to 22 June 2020), as well as the Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (Web of Science; 1990 to 25 February 2020) (Royle 2003). For the current update, we reviewed all records arising from Conference Proceedings Citation Index and LILACS, as these databases had not been included in the previous permutation of this review. CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and Science Citation Index ‐ Expanded had all been included in the previously published version of the review, and we reviewed all records from September 2006 (inclusive) onwards from these databases for the current update. We performed an all language search, evaluating only human studies. Appendix 1 presents the search strategies with time spans for the searches.

Searching other resources

We investigated the reference lists of identified trials for relevant trials. We searched conference proceedings/abstracts for European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), and British Society of Gastroenterology. When practicable, authors of studies identified to be pertinent were asked to review the list of identified trials and to add any unidentified trials. Manufacturers (TIPSs, pharmacological firms) were contacted. We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify protocols and any ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Searches for the original updated review were conducted by at least two review authors (SK and CTS for the 1st version; and RGS, GP, and HR for the update), who independently applied the inclusion criteria to all identified studies. At least two review authors independently extracted data from publications of interest, and for the update, data were extracted in greater detail and were rechecked by RGS, GP, and HR. We selected studies for inclusion no matter whether they reported on outcomes of interest to our review. Unpublished data were sought by writing to study authors (see notes under Characteristics of included studies). Review authors collected data for intention‐to‐treat analysis. We resolved any discrepancies or differences among us by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data using standardised forms, which captured data related to participant characteristics. Three review authors (RGS, GP, and HR) independently extracted data. We resolved disagreements by discussion. Data extraction encompassed comparability between groups randomised to alternative treatments regarding baseline prognostic variables, including aetiology of cirrhosis; mean age; proportion of males/females; participants with Child‐Pugh stage A, B, or C (Pugh 1973); completeness and length of follow‐up of treatment groups and reasons for withdrawals; presence of, absence of, or unknown for‐profit support; and trial design, exclusions, losses to follow‐up, and cross‐over of patients. Review authors also extracted data of particular interest for shunt intervention, including whether assessments had been made to assess the suitability of shunt intervention, and whether splenopancreatic disconnection was undertaken in people undergoing DSRS. We also extracted data related to the timing and method of assessing shunt patency.

We collected data for all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, health‐related quality of life, death due to rebleeding, development of acute hepatic encephalopathy, development of chronic hepatic encephalopathy, complications, hospital stay, and financial cost. When a trial had more than two groups, we extracted data only from groups that corresponded to the treatments compared in this review.

When possible, we measured outcomes as 'time‐to‐event'. To prevent loss of data, we assessed outcomes as dichotomous variables, using raw incidence over the entire follow‐up period reported by study authors (or the longest time point reported whenever multiple time points were reported).

For the outcomes of health‐related quality of life, complications, in‐hospital stay, and cost, we extracted data directly 'as reported' by study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (RS and GP) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies. In light of changes to Cochrane methods, we updated the risk of bias assessment using an adapted Cochrane risk of bias tool (adapted from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ‐ Higgins 2011; Higgins 2019 ‐ and the Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group Module). Due to changes to the Cochrane risk of bias tool since conduct of the previous review, we reassessed the risk of bias in previously included trials, with any discrepancy resolved by discussion between review authors.

Allocation sequence generation

Low risk of bias: sequence generation was achieved using computer random number generation or a random numbers table. Drawing lots, tossing a coin, shuffling cards, and throwing dice were adequate if performed by an independent person not otherwise involved in the trial

Unclear risk of bias: the method of sequence generation was not specified

High risk of bias: the sequence generation method was not random

Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias: participant allocations could not have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. Allocation was controlled by a central and independent randomisation unit; or the allocation sequence was unknown to the investigators (e.g. the allocation sequence was hidden in sequentially numbered, opaque, and sealed envelopes)

Unclear risk of bias: the method used to conceal the allocation was not described, so that intervention allocations may have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment

High risk of bias: the allocation sequence was likely to be known to investigators who assigned participants

Blinding of participants and treatment providers

Low risk of bias: any of the following ‐ no blinding or incomplete blinding, but review authors judge that the outcome is not influenced by lack of blinding; or blinding of participant and study personnel ensured, and it is unlikely that blinding could have been broken

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'

High risk of bias: no blinding or incomplete blinding, and outcome likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; or, blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that blinding could have been broken, and outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding

Blinding of outcome assessment

Low risk of bias: any of the following: blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that blinding could have been broken; or rarely no blinding or incomplete blinding, but review authors judged that the outcome was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding

Unclear risk of bias: any of the following: insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'; or the trial did not address this outcome

High risk of bias: any of the following: no blinding of outcome assessment, and outcome measurement likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; or blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk of bias: missing data were unlikely to make treatment effects depart from plausible values. The study used sufficient methods, such as multiple imputation, to handle missing data

Unclear risk of bias: information was insufficient to assess whether missing data in combination with the method used to handle missing data were likely to induce bias on the results

High risk of bias: results were likely to be biased due to missing data

Selective reporting

Low risk of bias: if the original trial protocol was available, outcomes should be those called for in that protocol. If the trial protocol was obtained from a trial registry, outcomes sought should have been those enumerated in the original protocol. If no protocol was available, the trial should have reported the following outcomes: all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, mortality due to rebleeding, complications, acute hepatic encephalopathy, and chronic hepatic encephalopathy

Unclear risk of bias: information insufficient to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'

High risk: not all of the study's pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes are reported via measurements, analyses, or subsets that were not pre‐specified; one or more primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; one or more outcomes of interest are reported incompletely; study fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study

Other bias

Low risk of bias: the trial appeared to be free of other factors that could put it at risk of bias

Unclear risk of bias: the trial may or may not have been free of other factors that could put it at risk of bias

High risk of bias: other factors in the trial could put it at risk of bias

Overall risk of bias

We assessed the overall risk of bias in a trial as:

low risk of bias: if all bias domains in a trial, as described in the above paragraphs, are judged at 'low risk of bias'; or

high risk of bias: if one or more of the bias domains in a trial, as described in the above paragraphs, are judged at 'unclear risk of bias' or 'high risk of bias'.

Measures of treatment effect

We assessed all outcomes through a combined analysis of all shunt types together ('shunt therapy pooled'; i.e. TS, DSRS, and TIPS combined) and repeated the analysis for each shunt type individually (TS, DSRS, TIPS). We calculated hazard ratios (HRs) for time‐to‐event outcomes and calculated risk ratios (RRs) for binary outcomes, and we planned to use mean differences (MDs) for continuous outcomes. For the outcomes all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, death due to rebleeding, development of acute hepatic encephalopathy, and development of chronic hepatic encephalopathy, when possible, we carried out analyses to allow reporting of time‐to‐event outcomes. Therefore, for each outcome in each comparison (shunts versus endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment: TS versus endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment; DSRS versus endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment; TIPS versus endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment), we planned to calculate a pooled estimate of treatment effect as an HR. If estimates of log HR and its variance were not quoted directly in trial reports, we used alternative aggregate data (e.g. log rank test P values) to estimate log(HR) and its variance utilising methods proposed by Parmar 1998 and Williamson 2002, and summarised by Tierney 2007. When possible, we planned to calculate variance and observed‐expected (O‐E) rank from reported HRs and confidence intervals (CIs) (Tierney 2007, Section 3 to 6). However, in most cases, we planned to estimate log(HR) and its variance and O‐E using the quoted P value of the log‐rank test (Tudur 2001, Section 2.3; Tierney 2007, Sections 7 to 9). If no P value was quoted for the log‐rank test, we planned to estimate log(HR) and its variance from Kaplan‐Meier survival curves (Tudur 2001, Sections 2.4 and 2.5; Tierney 2007, Section 10). Full details and discussion of the reliability of results are given in Tudur 2001.

We were not able to extract sufficient data to allow time‐to‐event analysis from all reports. Therefore, to prevent loss of data, we also reported the same outcomes (i.e. all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, death due to rebleeding, development of acute hepatic encephalopathy, and development of chronic hepatic encephalopathy) as dichotomous outcomes, using binary data to calculate the RR. We decided to report only the results of analysis of dichotomous data because they were available for all trials, and because we used dichotomous data to grade the evidence (see below) and to perform Trial Sequential Analysis, while avoiding redundant information. We planned to report results of time‐to‐event analysis if discrepancies with the main analysis were found.

For high variability on continuous outcomes (inpatient stay and costs), we did not meta‐analyse the results and reported mean differences for each trial when available.

To ensure consistency across studies identified in the initial review and in the current update, calculations from the initial review were reviewed and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion between review authors.

For this update, we decided to report 'financial cost' and 'length of hospital stay' as the raw data published by trialists in light of considerable inter‐trial variability in the definitions and methods used; therefore, overall, it was judged that reported data were not comparable across all trials.

Unit of analysis issues

Participants as randomised to an intervention group of a clinical trial are the unit of analysis. In trials of two–parallel group design, we compared the experimental intervention group versus the control. In trials with a parallel group design with more than two intervention groups of interest to our review, we planned to compare separately each of the experimental groups with each half of the control group.

To avoid repeated observations on trial participants, we used participant trial data at the longest follow‐up (Higgins 2011; Higgins 2019).

We identified no cluster‐randomised trials.

Dealing with missing data

Whenever possible, we performed all calculations according to intention‐to‐treat principles (i.e. with all randomised trial participants included in the analysis within the group into which they were randomised). In some trials, results were presented on a per‐protocol basis, or the given information was insufficient to assess whether data had truly been presented with use of the 'intention‐to‐treat' principle (GDEAIH 1995; García‐Villarreal 1999). When this was the case, we contacted study authors to retrieve pertinent data. As further information was not given, we used all data that were available to us.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by visual examination of forest plots and overlapping CIs, and through use of the I² statistic. The I² statistic was interpreted as follows: 0% to 40% heterogeneity may not be important; 30% to 60% moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% heterogeneity may be substantial; 75% to 100% heterogeneity may be considerable (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Whenever we had 10 or more trials, we drew funnel plots to assess reporting biases from individual trials by plotting the risk ratio (RR) on a logarithmic scale against its standard error (Egger 1997; Higgins 2011; Higgins 2019). We examined the degree of asymmetry of the funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analyses using the software package Review Manager 5.4 (Review Manager 2014). We used a random‐effects model meta‐analysis approach because we expected that the trials were heterogeneous. When data were available from only one trial, we used Fisher's exact test for dichotomous data (Fisher 1992). We planned to use Student's t‐test for continuous data such as 'health‐related quality of life' (Student 1908).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed all analyses with all shunt types but also with individual shunt types: TS, DSRS, and TIPS.

We planned subgroup analyses according to risk of bias, analysing separately randomised clinical trials at low risk of bias compared to trials at high risk of bias. We did this because trials at high risk of bias can overestimate the benefits and underestimate the harms.

We also analysed trials with for‐profit funding; without for‐profit support; and with unknown for‐profit support to evaluate whether for‐profit funding is associated with greater intervention benefit.

No other subgroup analyses were planned a priori, and none were undertaken due to the small sample size in each group.

Robustness of conclusions was assessed using sensitivity analyses (see below). When there was substantial heterogeneity, we considered and discussed the appropriateness of performing the meta‐analysis. We did not perform a meta‐analysis if viewed as inappropriate. We explored reasons for possible heterogeneity, while examining characteristics of trials.

Sensitivity analysis

We employed sensitivity analyses within each type of portosystemic shunt to test the robustness of our results.

Excluding trials examining participants with previous bleeding from gastric varices, as they were likely more difficult to treat with endoscopy.

Including only trials specifying use of polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE)‐covered TIPSs, as this could reduce the risk of occlusion of the stent.

Including only trials in which the PTFE‐covered TIPSs were not used, or in which the type of TIPS was not specified.

Including only trials combining endoscopic interventions with medical therapies, as these medical interventions could influence the effects of endoscopy.

Excluding trials combining endoscopic interventions with medical therapies to see if there are differences in the intervention effects.

Including only trials using endoscopic banding exclusively (i.e. excluding those using glue injection, sclerotherapy, or combination treatments) as use of the mentioned example interventions could modify effects of endoscopic intervention.

As further sensitivity analyses, we compared evaluation of imprecision with GRADE based on the GRADE Handbook, with GRADE based on our choice of plausible RRR and multiplicity correction, and according to our Trial Sequential Analysis (described below), with a similar choice of a plausible RRR and multiplicity correction, in addition to considering the choice of a meta‐analytic model and diversity (Jakobsen 2014; Castellini 2018; Gartlehner 2019).

Trial Sequential Analysis

Trial Sequential Analysis considers the choice of statistical model (fixed‐effect or random‐effects meta‐analysis) and diversity (Thorlund 2011; TSA 2011). We calculated the diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS, i.e. the number of participants needed in a meta‐analysis to detect or reject a certain intervention effect) (Brok 2008; Wetterslev 2008; Brok 2009; Wetterslev 2009; Thorlund 2010; Wetterslev 2017).

The underlying assumption of Trial Sequential Analysis is that testing for statistical significance may be performed each time a new trial is added to the meta‐analysis. We added trials according to the year of publication, and if more than one trial was published in a year, we added trials alphabetically according to the last name of the first author. On the basis of the DARIS, we constructed the trial sequential monitoring boundaries for benefit, harm, and futility (Wetterslev 2008; Wetterslev 2009; Thorlund 2011; Wetterslev 2017). These boundaries determine the statistical inference one may draw regarding the cumulative meta‐analysis that has not reached the DARIS; if the trial sequential monitoring boundary for benefit or harm is crossed before the DARIS is reached, firm evidence may be established and further trials may be superfluous. However, if the boundaries for benefit or harm are not crossed, it is most probably necessary to continue doing trials to detect or reject a certain intervention effect. However, if the cumulative Z‐curve crosses the trial sequential monitoring boundaries for futility, no additional trials may be needed.

In our Trial Sequential Analysis of the two primary dichotomous outcomes, we based the DARIS on event proportions in the control group assuming a plausible relative risk reduction (RRR) for all‐cause mortality of 10% and for rebleeding of 20%; risk of type I error of 2.5% due to the three primary outcomes (Jakobsen 2014); risk of type II error of 20%; and the diversity of trials included in the meta‐analysis. We repeated the analysis with a plausible RRR of 40% for rebleeding. For the continuous outcome, health‐related quality of life, we planned to estimate the DARIS using a minimal relevant difference of the standard deviation/2; type I error risk of 2.5% due to the three primary outcomes (Jakobsen 2014); risk of type II error of 20%; and diversity as estimated from trials in the meta‐analysis (Wetterslev 2009). We also calculated Trial Sequential Analysis–adjusted confidence intervals (CIs) (Thorlund 2011; Wetterslev 2017).

In our Trial Sequential Analysis of secondary outcomes, we based the DARIS for dichotomous outcomes on the event proportion in the control group; we made an assumption of an RRR of 20% for death due to rebleeding, development of acute hepatic encephalopathy, development of chronic hepatic encephalopathy and complications; type I error risk of 1.4% due to the six secondary outcomes (Jakobsen 2014); risk of type II error of 20%; and the diversity of trials included in the meta‐analysis. We repeated the analysis with a plausible RRR or increase of 40% for mortality due to rebleeding, development of acute hepatic encephalopathy, and development of chronic hepatic encephalopathy. For the continuous outcome, hospital stay and cost, we planned to estimate the DARIS using a minimal relevant difference of the standard deviation/2; type I error risk of 1.4% due to the six secondary outcomes (Jakobsen 2014); beta of 20%; and diversity as estimated from trials in the meta‐analysis (Wetterslev 2009).

We reported results of the comparison of GRADE and Trial Sequential Analysis. We downgraded imprecision in Trial Sequential Analysis by two levels if the accrued number of participants was below 50% of the diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS), and one level if between 50% and 100% of DARIS. We did not downgrade if the cumulative Z curve crossed the monitoring boundaries for benefit, harm, or futility, or if DARIS was reached.

A more detailed description of Trial Sequential Analysis and the software programme can be found at www.ctu.dk/tsa/ (Thorlund 2011).

'Summary of findings' tables and GRADE

We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables for the update of the review. We created 'Summary of findings' tables for the pooled analysis of all shunt interventions ('shunt therapy pooled') versus endoscopic intervention with or without medical treatment (Table 1), and we presented individual tables for TS (Table 2), DSRS (Table 3), and TIPS (Table 4) for the following outcomes: all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, health‐related quality of life, mortality due to rebleeding, acute hepatic encephalopathy, and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. We used dichotomous data to assess absolute effects.

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro software and GRADE Interactive software (www.gradepro.org; GRADEpro GDT), in accordance with Cochrane guidelines and the GRADE Handbook (Grade Handbook). GRADE appraises the certainty of evidence, assessing the degree to which we can be confident that the estimate of effect truly reflects the effect being assessed. The GRADE factors for assessing the evidence are trial risk of bias (methodological quality), indirectness of the evidence (population, intervention, control, outcomes), heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, imprecision of effect estimates (considering width of confidence intervals, optimal information size, and whether confidence intervals exclude important benefit or important harm), and possible publication bias (including use of funnel plots) (Grade Handbook). To calculate the optimal information size (OIS), we used the conservative estimates of a RRR of 25%, beta 20%, and alpha 0.05.

Overall, we graded the level of evidence as 'high', 'moderate', 'low', or 'very low' (Grade Handbook; GRADEpro GDT).

High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

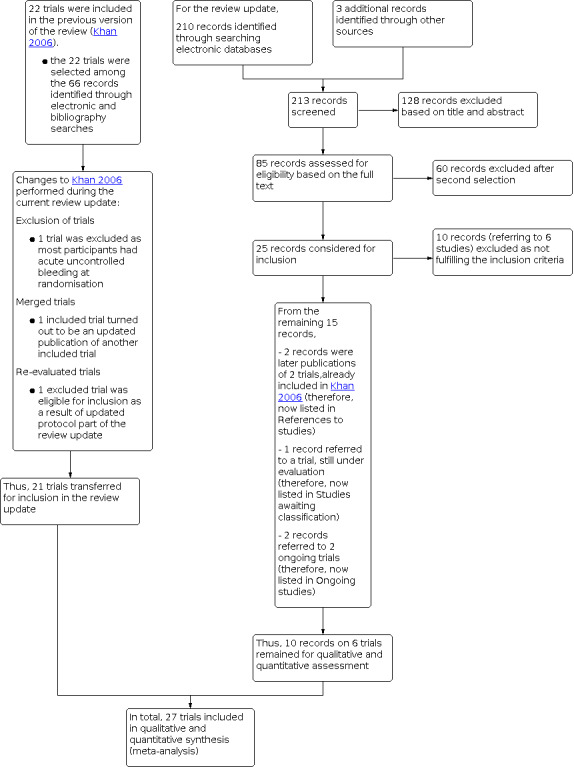

The updated search identified in total 210 records of possible interest for our review (Figure 1). Three additional records were identified through other sources (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram. Searches performed up to June 2020

Of these 213 records, 25 were screened further for inclusion. We excluded ten records reporting six trials based on reading the full‐text publications, as they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria of our review (Orloff 2009; Garcia‐Pagan 2010; Li 2015; Sauerbruch 2015; Orloff 2015; Wang 2015). Two further records were later publications of two other trials already included in the previous review version (Merli 1998: a full report of a previous abstract; Santambrogio 2006: long‐term follow‐up of the Spina 1990 trial). We listed these two references within their trial identifiers in Characteristics of included studies. One record reported a randomised clinical trial (Lv 2019) which is under evaluation (Studies awaiting classification), because it is not clear if participants with active uncontrolled bleeding after randomisation were included. A letter was sent to the study authors to request more information. Two records described the protocols of two ongoing trials for which we did not find related publications at the time of our analysis (NCT02477384; NCT03094234) (Characteristics of ongoing studies). Ten records reported on six new trials, which we have included in the present review update (Lo 2007; Ferlitsch 2012; Luo 2015; Holster 2016; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020).

From the previous review version with 22 included trials, we had to reassess fulfilment of the inclusion criteria of two trial publications (Cello 1987; Sauer 1998). Most participants in the Cello 1987 trial had acute uncontrolled bleeding at randomisation; hence, we excluded the trial from the current review version. The trial publication Sauer 1998 and the trial publication Sauer 2002 seemed to be reports of the same trial, which was confirmed through personal communication with the trial authors (see the notes field of the Characteristics of included studies table). In addition, for the previous version of the review (Khan 2006), 14 trial publications have been excluded. Among these records, two publications (Rossi 1994 and Krieger 1997) were recognised as ancillary studies of trials that were already included, i.e.Sauer 1997 and Merli 1998. We listed these two references within their trial identifiers in Characteristics of included studies. One trial was reclassified and was added to the current version of the review (Urbistondo 1996).

For the current review version, we rechecked or updated extracted data with data found in the most recent multiple publications of five trials (Rikkers 1993; Merli 1998; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Sauer 2002; Santambrogio 2006). Furthermore, we found data on cost‐effectiveness presented in one conference abstract (see Holster 2016); and we extracted data on hepatic encephalopathy from Warren 1986 (see Henderson 1990), as the most recent publication ‐ Henderson 1990 ‐ did not report data on hepatic encephalopathy.

The Characteristics of excluded studies tables provides the reasons for exclusion of identified publications from the previous and current review versions (i.e. 18 trials with 24 references) (Cello 1982; Cello 1987; Escorsell 2002; Garcia‐Pagan 2010; Kitano 1992; Li 2015; Meddi 1999; Orloff 1994; Orloff 2009; Orloff 2015; Paquet 1990; Resnick 1974; Reynolds 1981; Sanyal 1994; Sauerbruch 2015; Terés 1987a; Tripathi 2001; Wang 2015).

As a result, 27 randomised clinical trials (three of which described results in abstract format (Korula 1987; GDEAIH 1995; Ferlitsch 2012) were included in this review update. The results of all trials were available in English.

Included studies

Trial design and setting

All of the 27 included trials were parallel‐group randomised clinical trials. These trials were carried out in 14 countries: the United States (n = 5) (Korula 1987; Henderson 1990; Rikkers 1993; Cello 1997; Sanyal 1997), Germany (n = 4) (Rossle 1997; Sauer 1997; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002), Spain (n = 4) (Terés 1987; Planas 1991; Cabrera 1996; García‐Villarreal 1999), Italy (n = 2) (Merli 1998; Santambrogio 2006), China (n = 2) (Luo 2015; Lv 2018), United Kingdom (n = 2) (Jalan 1997; Dunne 2020), France (n = 1) (GDEAIH 1995), Austria (n = 1) (Ferlitsch 2012), The Netherlands (n = 1) (Holster 2016), Sweden (n = 1) (Isaksson 1995), Canada (n = 1) (Pomier‐Layrargues 2001), Japan (n = 1) (Narahara 2001), Puerto Rico (n=1) (Urbistondo 1996), and Taiwan (n = 1) (Lo 2007).

Interventions

Three trials compared total shunt (TS) versus endoscopic intervention (164 participants) (Korula 1987; Planas 1991; Isaksson 1995), five trials compared distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS) versus endoscopic intervention (352 participants) (Terés 1987; Henderson 1990; Rikkers 1993; Santambrogio 2006; Urbistondo 1996). Ten trials compared transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) versus endoscopic intervention (Cabrera 1996; Cello 1997; Jalan 1997; Sanyal 1997; Merli 1998; García‐Villarreal 1999; Narahara 2001; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002; Lo 2007), and nine trials compared transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) versus endoscopic intervention combined with beta blockers (GDEAIH 1995; Sauer 1997; Rossle 1997; Sauer 2002; Ferlitsch 2012; Luo 2015; Holster 2016; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020). The 19 TIPS trials included 1312 participants.

Comparisons

Eight trials employed banding in the endoscopic intervention group (Jalan 1997; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002; Ferlitsch 2012; Luo 2015; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020). Sixteen trials employed endoscopic sclerotherapy (Korula 1987; Terés 1987; Henderson 1990; Planas 1991; Rikkers 1993; GDEAIH 1995; Isaksson 1995; Cabrera 1996; Urbistondo 1996; Cello 1997; Sanyal 1997; Sauer 1997; Merli 1998; García‐Villarreal 1999; Narahara 2001; Santambrogio 2006). Three trials used combinations of banding and either sclerotherapy or glue injection: one employed either sclerotherapy or band ligation (or combined sclerotherapy and banding) of oesophageal varices, with sclerotherapy of gastric varices (Rossle 1997); one treated oesophageal varices with banding and treated gastric varices with injection of cyanoacrylate/lipiodol (Holster 2016); one utilised glue injection of gastric varices, followed by banding when there were concomitant oesophageal varices (Lo 2007).

In summary, three trials compared TS versus sclerotherapy without drugs (Korula 1987; Planas 1991; Isaksson 1995), and five trials compared DSRSs with sclerotherapy without drugs (Terés 1987; Henderson 1990; Rikkers 1993; Urbistondo 1996; Santambrogio 2006). Among the 19 trials comparing TIPSs versus endoscopy, beta blockers were used in the endoscopic group in nine trials (two sclerotherapy (GDEAIH 1995; Sauer 1997), five band ligation (Sauer 2002; Ferlitsch 2012; Luo 2015; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020), and two band ligation and sclerotherapy (Rossle 1997; Holster 2016)). Ferlitsch 2012 specifically examined trial participants with rebleeding from oesophageal varices under sufficient pharmacological treatment (propranolol and isosorbide mononitrate) and continued medical treatment in the endoscopic banding group. In 10 trials, only endoscopic interventions were used in the control group (in three trials band ligation (Jalan 1997; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002), in six trials sclerotherapy (Cabrera 1996; Cello 1997; Sanyal 1997; Merli 1998; García‐Villarreal 1999; Narahara 2001), and in one trial glue injection into gastric varices and band ligation of oesophageal varices were used (Lo 2007)).

Participants

Full details of the 27 included trials are given in the Characteristics of included studies tables. All trials included 1828 participants with cirrhosis, with a history of variceal bleeding. Twenty‐three publications reported on participant age: mean age in 22 of the trials was 53.5 years, and median age in one trial was 49 years for participants treated with TIPS and 46 years for those treated with endoscopic intervention. The same 23 publications reported on sex, with a predominance of men in all trials (68.9% of participants were male) (Korula 1987; Terés 1987; Planas 1991; Isaksson 1995; Cabrera 1996; Urbistondo 1996; Cello 1997; Jalan 1997; Rossle 1997; Sanyal 1997; Sauer 1997; Merli 1998; García‐Villarreal 1999; Narahara 2001; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002; Santambrogio 2006; Lo 2007; Luo 2015; Holster 2016; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020).

Among trials assessing TSs, one trial included only participants with Child‐Pugh class A (Korula 1987), and two trials excluded participants in class C (Terés 1987; Planas 1991). Ferlitsch 2012 did not provide information on trial participants' Child‐Pugh class. Luo 2015 included participants in Child‐Pugh classes B and C.

All other trials included participants in all Child‐Pugh classes in different proportions. Merli 1998 excluded participants in Child‐Pugh class C with a score > 13. The Child‐Pugh score in the trials in which it was reported ranged from 6.6 in Rikkers 1993 to 9.8 in Pomier‐Layrargues 2001.

Urbistondo 1996 randomised participants in Child's classes A and B to DSRS, sclerotherapy, or propranolol, and participants in Child's C class to sclerotherapy or propranolol.

Eighteen trials specifically either included participants with oesophageal variceal bleeding only or excluded those with isolated gastric varices or gastric variceal bleeding (Henderson 1990; Rikkers 1993; GDEAIH 1995; Isaksson 1995; Cabrera 1996; Urbistondo 1996; Cello 1997; Jalan 1997; Sanyal 1997; Sauer 1997; Merli 1998; García‐Villarreal 1999; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002; Santambrogio 2006; Ferlitsch 2012; Luo 2015; Dunne 2020). One further trial excluded participants with 'large fundal varices' (Pomier‐Layrargues 2001). One trial was unique in focusing on gastric variceal bleeding (Lo 2007), excluding participants with acute oesophageal bleeds. One trial included participants with oesophageal or gastric variceal bleeding (or both) (Holster 2016). In four trial publications, the source of variceal bleeding was not specified (Korula 1987; Rossle 1997; Narahara 2001; Lv 2018), although Rossle 1997 discusses treatment of both oesophageal and gastric varices. Two trials included participants with both oesophageal and gastric variceal bleeding; however, participants with gastric varices were excluded from the endoscopic intervention group after randomisation (Terés 1987; Planas 1991).

Five trials did not provide information on the cause of cirrhosis (Korula 1987; Planas 1991; GDEAIH 1995; Isaksson 1995; Ferlitsch 2012). Of the remaining trials, alcohol was judged to be the specific cause of cirrhosis in 55.9% of trial participants (Terés 1987; Cabrera 1996; Urbistondo 1996; Cello 1997; Jalan 1997; Rossle 1997; Sanyal 1997; Sauer 1997; Merli 1998; García‐Villarreal 1999; Narahara 2001; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002; Santambrogio 2006; Lo 2007; Luo 2015; Holster 2016; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020). The Merli 1998, Lo 2007, and Lv 2018 trials reported that alcohol contributed to liver cirrhosis in only 25.9%, 16.6%, and 2.0%, respectively, of trial participants. Viral aetiology was reported in 13 trials (Cello 1997; Jalan 1997; Rossle 1997; Sanyal 1997; Sauer 1997; Narahara 2001; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002; Luo 2015; Holster 2016; Lv 2018; Dunne 2020), and this ranged from 3% in Dunne 2020 to 90% of participants in Lv 2018.

Portal vein thrombosis was an explicit exclusion criterion in at least 11 trials (Cello 1997; Jalan 1997; Sanyal 1997; Sauer 1997; García‐Villarreal 1999; Pomier‐Layrargues 2001; Gülberg 2002; Sauer 2002; Lo 2007; Holster 2016; Dunne 2020); three further trials excluded individuals with complete portal vein thrombosis or cavernous portal vein thrombosis (Rossle 1997; Merli 1998; Narahara 2001). In contrast, Luo 2015 and Lv 2018 specifically included only individuals with coexistent liver cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.