Abstract

The self-assembly of amyloidogenic peptides on membrane surfaces is associated with the death of neurons and β-cells in Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes, respectively. The early events of self-assembly in vivo are not known, but there is increasing evidence for the importance of the α-helix. To test the hypothesis that electrostatic interactions involving the helix dipole play a key role in membrane-mediated peptide self-assembly, we studied IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] (R11LANFLVHSGNNFGA25-NH2), which under certain conditions self-assembles in hydro to form β-sheet assemblies through an α-helix-containing intermediate. In the presence of small unilamellar vesicles composed solely of zwitterionic lipids, the peptide does not self-assemble presumably because of the absence of stabilizing electrostatic interactions between the membrane surface and the helix dipole. In the presence of vesicles composed solely of anionic lipids, the peptide forms a long-lived α-helix presumably stabilized by dipole–dipole interactions between adjacent helix dipoles. This helix represents a kinetic trap that inhibits β-sheet formation. Intriguingly, when the amount of anionic lipids was decreased to mimic the ratio of zwitterionic and anionic lipids in cells, the α-helix was short-lived and underwent an α-helix to β-sheet conformational transition. Our work suggests that the helix dipole and membrane electrostatics delineate the conformational transitions occurring along the self-assembly pathway to the amyloid.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The self-assembly of peptides or proteins has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), type 2 diabetes (T2D), and Parkinson’s disease (PD). In spite of the large differences in the primary structures of the implicated peptides or proteins, their self-assemblies exhibit common features including the formation of toxic, prefibrillar assemblies in the presence of cell membranes.1-4 Thus, understanding the interaction of amyloidogenic peptides with cell membranes and the mechanism underlying the formation of toxic membrane-bound assemblies are among the key prerequisites for the development of effective preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Structure determination of the membrane-bound structure of α-synuclein, an amyloidogenic protein associated with the formation of Lewy bodies in PD, has been facilitated by the relatively slow rate of α-synuclein self-assembly presumably because of the propensity of a significant part of the protein to form a long-lived, α-helix in the presence of model membranes.5,6 In contrast, the membrane-bound structure of shorter but more amyloidogenic peptides including amyloid-β (Aβ) in AD and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP, aka amylin) in T2D has been more difficult to determine, most likely due to rapid self-assembly. Nonetheless, computational and experimental studies of fragments or variants of Aβ and IAPP in the presence of model membranes have yielded important insights into the membrane biochemistry and biophysics of Aβ and IAPP and the development of therapeutics for AD and T2D.7-12

Here, we investigated a fragment of IAPP that forms an α-helix13-15 in order to explore the role of the helix dipole in the self-assembly of amyloidogenic peptides in the presence of membranes. IAPP is a 37-residue polypeptide (Figure 1) that is cosecreted with insulin from pancreatic β-cells. IAPP has received much attention over the past few decades because it aggregates to form assemblies that are toxic to β-cells.1,16-18 While fibrillar aggregates of IAPP are cytotoxic,19 it is presently thought that oligomeric assemblies are mostly responsible for β-cell death.2,20-22 The interaction of these assemblies with cell membranes is believed to be responsible for toxicity, through membrane poration as well as more dramatic membrane disruption.2,20,21,23-25 The structure of the oligomeric assemblies is poorly defined, but there is mounting evidence supporting a predominantly α-helical structure. In solution, IAPP forms transient α-helices15,26-28 that become long-lived upon interaction with membranes.13,29-32 Knight and co-workers showed that heterogeneously sized IAPP oligomers rich in α-helix are correlated with membrane damage detected by liposome leakage experiments.33 Bram and co-workers used micelles formed by sodium dodecyl sulfate as a model for membranes to produce stable, cytotoxic, α-helix-rich IAPP oligomers that were shown to enter cells.34 Moreover, antibodies which specifically recognized these oligomers were identified in T2D patients and were shown to rescue cells from apoptosis induced by IAPP. Together, these studies suggest that preventing the formation and stabilization of membrane-bound α-helical oligomers of IAPP is an attractive strategy for blocking membrane damage and cytotoxicity induced by the polypeptide. This requires a deeper understanding of the structural basis of membrane-mediated α-helix formation and stabilization.

Figure 1.

Primary structure of human IAPP. The substitution of the serine residue in red with glycine is associated with early onset T2D.

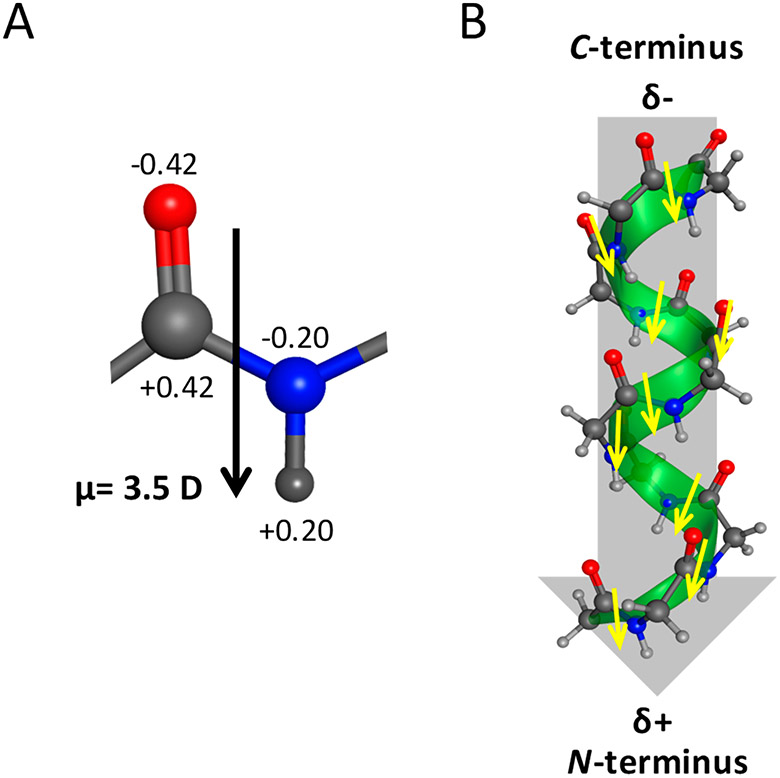

Each peptide group in a protein has a dipole moment associated with its structure (Figure 2A). Using fractional charges of the four atoms in the group and their locations, the magnitude of the vector has been calculated to be approximately 3.5 D (Debye).35 The direction of the vector is approximately parallel to the N─H bond, as shown in Figure 2A. In an α-helix, the dipole moments of the individual peptide groups add up vectorially to form an enhanced dipole (aka macroscopic dipole or helix dipole) that is oriented along the helix axis (Figure 2B).35,36 The positive and negative ends of the helix dipole are at the N- and C-terminus of the helix, respectively. We hypothesize that electrostatic interactions involving the helix dipole and membrane surface underpin the stabilization of α-helical oligomers of IAPP. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the self-assembly of an amyloidogenic peptide derived from IAPP in the presence of small unilamellar vesicles (SUV). This peptide, designated here as IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2], was unstructured, formed an α-helix that did not convert to a β-sheet, or formed a β-sheet through an α-helix-containing intermediate depending on the negative charge density on the membrane surface. These results indicate that both helix dipole and membrane electrostatics delineate the conformational transitions occurring during the self-assembly of amyloidogenic peptides on membrane surfaces.

Figure 2.

Dipoles in an α-helix. (A) The dipole moment of the peptide group can be calculated from the partial charges of the O, C, N, and H atoms, which are shown as multiples of the elementary charge, and from their relative locations. Its magnitude is approximately 3.5 D (Debye) and is more or less parallel to the N─H bond. (B) In an α-helix, the dipole moments of the peptide groups align approximately along the helix axis, and thus these add up vectorially to form a macroscopic dipole or helix dipole. The positive and negative ends of the dipole are at the N- and C-terminus of the helix, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Peptide and Lipids.

IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] (98% pure) was purchased from NeoBioScience (Woburn, MA). DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) (>99% pure) and DOPS (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine) (>99% pure) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL).

Preparation of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] Solutions.

Stock solutions of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] were prepared using the procedure we have used in preparing aggregate-free solutions of IAPP peptides.15 IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] was dissolved in ice-cold 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). To remove undissolved peptide and preformed aggregates, a two-step procedure that included centrifugation at 16 000 × g for 30 s and a careful transfer of the supernatant to unused Eppendorf tubes was performed three times. The final supernatant was used for the ensuing biophysical studies. Peptide concentration was determined by UV absorbance at 214 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 29 230 M−1 cm−1. This was calculated based on the assumption that the molar extinction coefficient of the peptide at 214 nm is defined by the contribution of peptide bonds and amino acids present, as discussed elsewhere.37

Preparation of Small Unilamellar Vesicles.

SUV containing 100% DOPC, 100% DOPS, or DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole ratio) were prepared following the procedure described by de Planque and co-workers.38 The lipids were dissolved in methanol/chloroform (1:1, v/v). After vortexing, the solvents were evaporated by a stream of nitrogen gas, resulting in a lipid film. To remove residual solvents, the film was dried overnight under high vacuum. The film was then hydrated with 1 mL of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The hydrated suspension of liposomes was freeze–thawed (10 times) to increase the size homogeneity of the multilamellar vesicles. Liquid nitrogen and a water bath at 37 °C were used for freezing and thawing, respectively. The samples were then sonicated using a VCX750 Vibra-Cell ultrasonic liquid processor equipped with a tapered microtip (Sonics and Materials, Inc., Newtown, CT) using the following settings: sonication time = 5 min; 25 °C; 25% duty cycle; and 21% tip amplitude. The resulting suspension of unilamellar vesicles was then centrifuged for 15 min at 16 000 × g and 25 °C to pellet titanium particles and residual multilamellar vesicles.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy.

CD test samples containing IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] and SUV were prepared by combining aliquots from the stock solutions that will result in a peptide-to-lipid molar ratio of 1:50. The amount of lipid was calculated from the mass of lipid used and its molar mass (786.1 g mol−1 for DOPC, 810.0 g mol−1 for DOPS). All test samples were incubated in CD cuvettes to minimize agitation induced by pipetting. To facilitate the detection of conformational changes by CD, all samples were stored at 4 °C, a temperature at which peptide self-assembly is slowed down significantly.15,39 Blank samples containing SUV only (100% DOPC, 100% DOPS, or DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole ratio) in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)) were also prepared.

Far-UV CD spectra of the blank and test samples were recorded at 4 °C using a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter. Quartz cuvettes with a path length of 1 mm were used. All spectra presented here are the average of 6 scans, with each scan recorded over a wavelength range of 260–200 nm at a fixed interval of 1 nm. The raw data with units of mdeg were converted to mean-residue ellipticity using eq 1:

| (1) |

where [θ] is the mean-residue ellipticity in deg cm2 dmol−1, θobs is the observed ellipticity in mdeg, M is the molar mass of the peptide (i.e., 1616.8 g mol−1 for IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2]), d is the path length of the cuvette in cm, c is the concentration of the protein in g L−1, and n is the number of residues in the peptide, i.e., 15 for IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2].

Deconvolution of CD spectra has been widely used to determine the distribution of secondary structures in the protein of interest.40 The success of deconvolution, however, depends primarily on the availability of reference databases that include CD spectra of proteins of known structure.41 Because current databases do not include CD spectra of peptide or protein assemblies, deconvolution may not be applicable to the analysis of CD spectra of amyloidogenic peptides and proteins.14,15,41 Nonetheless, if the protein assembly of interest is predominantly α-helical, a suitable alternative to deconvolution is to use eq 2, which has been successfully applied to determine the helix content of α-helical assemblies:42

| (2) |

where [θ]222nm is the mean-residue ellipticity of the peptide at 222 nm and [θ]222nm,100%helix is the calculated mean-residue ellipticity at 222 nm of a peptide with a helix content of 100%. To calculate the latter, we used the following equation derived by Chen et al.:43

| (3) |

where [θ]222nm,infinite helix is the mean-residue ellipticity at 222 nm for an infinite helix determined by Chen et al. to be equal to −37 400 deg cm2 dmol−1,43 k is a wavelength-dependent factor that is equal to 2.5 at 222 nm,43 and nhelix is the number of residues in the helix. Using eq 3, we calculated that [θ]222nm,100% helix for IAPP[11–2S(S20G)-NH2] is −33333 deg cm2 dmol−1.

Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Aliquots from CD samples were spotted on carbon-coated copper grids and stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 2 min. After drying, the grids were stored at 25 °C. Electron microscopy was performed at the Core Electron Microscopy Facility of the University of Massachusetts Medical School using a Phillips CM10 transmission electron microscope.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rationale for the IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] Peptide.

Recently, we showed that the segment comprising residues 11–25 of IAPP is responsible for the initial intermolecular contacts between IAPP monomers.15 A capped peptide (i.e., its N- and C-termini are acetylated and amidated, respectively) containing this segment (acetyl-R11LANFLVHSSNNGFA25-NH2) self-assembled in water to form α-helical assemblies.15 When the S20G mutation (Figure 1) associated with early onset T2D44 and with dramatic enhancement of the self-assembly of full-length IAPP45 was introduced (i.e., acetyl-R11LANFLVHSGNNGFA25-NH2), the peptide aggregated more rapidly to form amyloid fibrils of similar morphology to fibrils formed by full-length IAPP.15 This result indicates that acetyl-R11LANFLVHSGNNGFA25-NH2 models the increased amyloidogenicity of mutated IAPP relative to wild-type IAPP, and thus we have studied the peptide to decipher mechanistic details of conformational transitions associated with protein self-assembly. Intriguingly, the half-blocked analogue of the peptide (i.e., R11LANFLVHSGNNGFA25-NH2, designated here as IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2]), did not self-assemble because of the helix-dipole effect; i.e., electrostatic repulsion between the positive charge on the backbone of Arg11 and the positive end of the helix dipole prevents α-helix formation.14 Here, we hypothesized that the helix dipole and membrane electrostatics regulate the self-assembly of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of model membranes.

Rationale for SUV and for Lipid Composition.

To model cell membranes, we chose SUV. Relative to other model systems including large unilamellar vesicles and giant unilamellar vesicles, SUV possess high membrane curvature, which has been shown by others to enhance the binding of amyloidogenic peptides and proteins to the membrane surface and to facilitate the ensuing conformational transitions.46-48 We investigated the self-assembly of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV composed of (a) 100% DOPC, a zwitterionic lipid (Figure 3); (b) 100% DOPS, a negatively charged lipid (Figure 3); and (c) DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole ratio), which mirrors the ratio of zwitterionic to negatively charged lipids in β-cells.49,50 Characterization of the SUV by TEM showed the expected circular shapes and distribution of diameters (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). We hypothesized that IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] will not self-assemble in the presence of SUV in (a) but will do so in the presence of SUV in (b) and (c) but in different ways. For control, we also studied IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the absence of SUV.

Figure 3.

Structures of zwitterionic and anionic lipids. Both lipids used in this work are phospholipids. They differ in the net charge of their headgroups in that DOPC is zwitterionic (i.e., its headgroup has no net charge) while DOPS is negatively charged (i.e., its headgroup has a net charge of −1).

Structural Transitions in IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] by Circular Dichroism.

To characterize the structural changes that occur as IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] self-assembles in the presence of SUV, we used CD spectroscopy which has been used widely in structural studies of Aβ3,51 and IAPP52,53 in the presence of model membranes. Figure S2 in the Supporting Information and Figure 4 present time-dependent CD spectra of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the absence and presence of SUV, respectively. The peptide in buffer only (pH 7.4) over the 14-day incubation period was unstructured as indicated by dichroic signals near 0 above 210 nm and strong negative dichroic signals below 210 nm in the CD spectra shown in Figure S2. In the presence of SUV composed solely of DOPC, Figure 4A shows that the peptide was also unstructured as indicated by dichroic spectra that were essentially similar to the spectra of the peptide in pure buffer (Figure S2). In the presence of SUV that contain DOPS, however, we observed dramatic changes in the CD spectra of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2]. Figure 4B shows that each of the dichroic spectra of the peptide in the presence of SUV that contain 100% DOPS shows two negative bands centered at 222 and 208 nm, consistent with the presence of an α-helix. Both bands have been assigned to electronic transitions in the amide group, namely an nπ* transition assigned to the band centered at 222 nm and a ππ* transition polarized along the helix axis assigned to the band centered at 208 nm.54 The intensities of the dichroic signals at 222 and 208 nm increased with incubation time (Figure 4B), indicating an increase in the α-helical content of the peptide. To quantify the helix content, we used eq 2. Our calculations show that at day 0, the helix content of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] was 19%. This increased to 50% after 14 days of incubation. Intriguingly, IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV composed of DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole ratio) produced dichroic spectra over the same incubation period consistent with a more dramatic change in the secondary structure (Figure 4C). The dichroic spectra of the peptide recorded at day 0, day 2, and day 4 showed two minima at 222 and 208 nm, indicating the dominant presence of α-helix. The helix content of the peptide increased from 19% at day 0 to 25% at day 4. At day 8–day 14, the peptide yielded dichroic spectra with a single band centered at 216 nm, which has been assigned to the nπ* transition in β-sheets.54 These results indicate that IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV containing both DOPC and DOPS undergoes an α-helix to β-sheet conformational transition.

Figure 4.

Representative time-dependent changes in the dominant secondary structure of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV. Circular dichroic spectra of the peptide in the presence of SUV composed of (A) DOPC only, (B) DOPS only, and (C) DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole ratio). The peptide concentration in all samples was 30 μM.

Detection of Peptide Assemblies by Electron Microscopy.

To detect peptide assemblies and to determine their effects on the morphology of SUV, we used TEM. This technique has been used recently by others to characterize the perturbation of phospholipid vesicles by α-synuclein fibrillogenesis,55 detection of α-synuclein:lipid costructure complexes in mixtures of the protein and SUV,56 modulation of membrane architecture by IAPP to form structures of high curvature,32 binding of α-synuclein and huntingtin exon 1 amyloid fibrils to vesicles composed of brain lipids,57 and attachment of Aβ42 fibrils to SUV.58 Figure S1 in the Supporting Information summarizes our characterization of control SUVs by TEM. The micrographs show the expected circular shapes of the vesicles with diameters ranging from 20 to 100 nm, consistent with reported sizes of SUV.59 Next, we obtained TEM micrographs of the samples that produced the day-14 CD spectra in Figure 4. At one end, grids containing unstructured IAPP[11-25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV composed solely of DOPC produced micrographs that only show vesicles (Figure 5A). No peptide assemblies were detected, consistent with the absence of secondary structure in the peptide (Figure 4A). The shape and distribution of diameters of the SUV were similar to the control (Figure 6A). At the other end, grids containing β-sheet IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] formed in the presence of SUV composed of DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole ratio) produced micrographs showing massive deposition of fibrils of indeterminate lengths (Figure 5C), consistent with the dominant presence of the β-sheet structure in the peptide (Figure 4C). Some fibrils aggregated further to form ropelike assemblies. Isolated fibrils have an average diameter of 12 nm, similar to the reported mean diameter of fibrils formed by full-length IAPP in the presence of model membranes.29 Micrographs obtained at higher magnification show deformed, nonspherical SUVs attached to fibrils (Figure S3 in the Supporting Information), implying coaggregation. Previous work by others has shown that amyloidogenic peptides and proteins including Aβ, IAPP, and α-synuclein in the presence of model membranes coaggregate with lipids, resulting in large perturbations to the membrane structure, similar to those shown in Figure S3 50,60,61

Figure 5.

TEM of circular dichroic samples of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV. Representative micrographs of day-14 CD samples of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of SUV composed of (A) DOPC only, (B) DOPS only, and (C) DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole). Scale bars in (A) and (B) correspond to 0.5 μm. Scale bar in (C) corresponds to 200 nm.

Figure 6.

Differential effects of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] on vesicle size. Histograms of the distributions of SUV diameters composed of (A) DOPC and (B) DOPS in the absence (blue bars) and presence (red bars) of peptide. In (A), the histograms are similar, each showing that over 70% of the vesicles have diameters that range from 26 to 50 nm. In (B), the histogram for SUV diameters in the presence of α-helical peptide is shifted to larger diameters.

Intriguingly, grids containing α-helical IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] formed in the presence of SUV composed solely of DOPS produced micrographs that show the dominant presence of distorted SUV (Figure 5B). We observed two types of distortions. Most of the vesicles that remained spherical have diameters greater than the control (Figure 6B). Some of the vesicles aggregated or clustered together (Figure 5B). Other vesicles have roughened surfaces (Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). Together, these observations indicate that distortions to the morphology of SUV occur before significant β-sheet formation by IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2], supporting studies indicating that toxicity by IAPP is associated with α-helix.2,20,21,23-25

Resulting Mechanism for the Self-Assembly of Amyloidogenic Peptides in the Presence of Membranes.

Our results can be summarized as follows: (1) IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2], a fragment of IAPP that corresponds to the α-helical region of full-length IAPP, is predominantly unstructured, α-helix, and β-sheet in the presence of SUVs composed of 100% zwitterionic lipid, 100% anionic lipid, and a mixture of zwitterionic (70%) and anionic (30%) lipids, respectively. (2) The extent of helix formation by IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] in SUVs composed of 100% anionic lipid increases with incubation time and is long-lived in that the α-helix did not convert to β-sheet (Figure 4B). (3) Decreasing the negative charge density in the SUVs to 70%, which mimics the charge density of membranes in β-cells,50 facilitates an α-helix to β-sheet conformational rearrangement. Figure 7 presents a schematic diagram of the resulting pathway for the self-assembly of IAPP[11–25-(S20G)-NH2] in the presence of model membranes. In SUVs composed of 100% zwitterionic lipid, the peptide does not interact with the membrane surface (Figure 7A). It does not self-assemble presumably because of helix-dipole effects;14 i.e., helix formation is abolished presumably because of electrostatic repulsion between the α-NH3+ group of Arg11 and the positive end of the first peptide dipole. In the presence of membranes with negatively charged lipids, the electrostatic attraction between the α-NH3+ group of Arg11 and the negatively charged headgroup of the anionic lipid leads to the binding of the peptide on the membrane surface. The binding eliminates the helix-dipole effect, resulting in the formation of α-helix. If the density of anionic lipids on the membrane surface is high, electrostatic helix dipole–helix dipole interactions, which have been implicated in early stages of self-assembly by IAPP in membranes,62 favor an antiparallel orientation of adjacent helices (Figure 7B). In this orientation, the two dipoles interact attractively, facilitating the increase in the α-helical content in each peptide (Figure 4B). The lengthening of the α-helix, in turn, inhibits conversion to β-sheet. The longer helix thus represents a kinetic trap. α-Helical kinetic traps have also been postulated to delay β-sheet formation by Aβ and full-length IAPP.13,29,63,64 If the density of anionic lipids is low, the helices are further apart, and the antiparallel orientation is not forced or favored (Figure 7C). The helix content in each peptide does not increase, but conversion to β-sheet takes place (Figure 4C). In the absence of stabilizing interhelical dipolar interactions, the α-helix-containing but predominantly unstructured peptide is a transient intermediate that is then converted to β-sheet.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism for IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] self-assembly on membrane surfaces. (A) In the presence of SUVs composed of 100% zwitterionic DOPC, self-assembly of IAPP[11–25(S20G)-NH2] is inhibited because of helix-dipole effects; i.e., the putative α-helix intermediate does not form because of the repulsion between positive charge α-NH3+ in Arg11 and the positive end of first peptide dipole, and thus the peptide remains in an unstructured, unaggregated form. (B) In the presence of anionic vesicles composed of 100% DOPS, the helix-dipole effect is eliminated by electrostatic attraction between the positively charged α-NH3+ of Arg11 and the negatively charged headgroup of the lipid. The high density of anionic lipids favors the antiparallel orientation of adjacent helix dipoles, which leads to an increase in helix content in each peptide such that β-sheet formation is abolished. (C) In SUVs composed of DOPC/DOPS (7:3, mole:mole), in which the density of anionic lipids is low, the α-helix-containing peptides are farther away from each other, and thus the antiparallel orientation of helices is less likely. The helix content of the peptides does not increase, but further self-assembly to β-sheet occurs.

In summary, this work shows that electrostatics involving the helix dipole and the negative charge in anionic lipids provide specificity for conformational transitions occurring during the self-assembly of amyloidogenic peptides on membrane surfaces. Anionic lipids in cells include phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol, with the former being more abundant than the latter.65 The amount of anionic lipids in cells varies but is generally ≤30%. Its distribution also differs from cell to cell;65 however, we surmise that in some cells, the distribution of anionic lipids becomes aberrant leading to an abnormal clustering of the negatively charged lipids. In normal cells characterized by a wide dispersal of anionic lipids, we expect that α-helical amyloidogenic peptide surfaces will be transient and, presumably, will readily undergo further self-assembly to form the less toxic β-sheet assemblies. In diseased cells characterized by clustering of anionic lipids, the self-assembly of amyloidogenic peptides on the defective membrane surfaces leads to long-lived α-helical assemblies that represent kinetic traps. This work demonstrates that conformational transitions between α-helix and β-sheet assemblies of amyloidogenic peptides that self-assemble through the α-helical intermediate are delineated by the helix dipole and membrane electrostatics. Moreover, this work suggests that the antiparallel alignment of α-helix dipoles, which has been implicated in the stabilization of antiparallel transmembrane helices,66 contributes to the stabilization of α-helical oligomers on membrane surfaces. The elucidation of pathways leading to aberrant combinations of surface charge and helix dipole generated from the interaction of amyloidogenic peptides and proteins with membranes, and high-resolution structural studies of α-helical oligomers on membrane surfaces by cryo-electron microscopy 67,68 for the generation of electrostatic potential maps,69 may provide new insights into the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies for AD, T2D, and PD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Parts of this work were funded by the Lise Ann and Leo E. Beavers II endowment to Clark University and by the National Institutes of Health (R15AG055043 to N.D.L.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c00723.

CD spectra; TEM images (Figures S1-S4) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hebda JA; Miranker AD The Interplay of Catalysis and Toxicity by Amyloid Intermediates on Lipid Bilayers: Insights from Type II Diabetes. Annu. Rev. Biophys 2009, 38, 125–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Brender JR; Salamekh S; Ramamoorthy A Membrane Disruption and Early Events in the Aggregation of the Diabetes Related Peptide IAPP from a Molecular Perspective. Acc. Chem. Res 2012, 45, 454–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Matsuzaki K How Do Membranes Initiate Alzheimer’s Disease? Formation of Toxic Amyloid Fibrils by the Amyloid β-Protein on Ganglioside Clusters. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2397–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Das T; Eliezer D Membrane Interactions of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: The Example of α-Synuclein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2019, 1867, 879–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sung YH; Eliezer D Structure and Dynamics of the Extended-Helix State of α-Synuclein: Intrinsic Lability of the Linker Region. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 1314–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Fusco G; De Simone A; Gopinath T; Vostrikov V; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; Veglia G Direct Observation of the Three Regions in α-Synuclein That Determine Its Membrane-Bound Behaviour. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bera S; Arad E; Schnaider L; Shaham-Niv S; Castelletto V; Peretz Y; Zaguri D; Jelinek R; Gazit E; Hamley IW Unravelling the Role of Amino Acid Sequence Order in the Assembly and Function of the Amyloid-β Core. Chem. Commun (Cambridge, U. K.) 2019, 55, 8595–8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lu Y; Shi XF; Nguyen PH; Sterpone F; Salsbury FR Jr.; Derreumaux P Amyloid-β(29–42) Dimeric Conformations in Membranes Rich in Omega-3 and Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 2687–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Nath A; Miranker AD; Rhoades E A Membrane-Bound Antiparallel Dimer of Rat Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 10859–10862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Martel A; Antony L; Gerelli Y; Porcar L; Fluitt A; Hoffmann K; Kiesel I; Vivaudou M; Fragneto G; de Pablo JJ Membrane Permeation Versus Amyloidogenicity: A Multitechnique Study of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Interaction with Model Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Brender JR; Heyl DL; Samisetti S; Kotler SA; Osborne JM; Pesaru RR; Ramamoorthy A Membrane Disordering Is Not Sufficient for Membrane Permeabilization by Islet Amyloid Polypeptide: Studies of IAPP(20–29) Fragments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2013, 15, 8908–8915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Smith PE; Brender JR; Ramamoorthy A Induction of Negative Curvature as a Mechanism of Cell Toxicity by Amyloidogenic Peptides: The Case of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 4470–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Apostolidou M; Jayasinghe SA; Langen R Structure of α-Helical Membrane-Bound Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide and Its Implications for Membrane-Mediated Misfolding. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 17205–17210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Liu G; Robbins KJ; Sparks S; Selmani V; Bilides KM; Gomes EE; Lazo ND Helix-Dipole Effects in Peptide Self-Assembly to Amyloid. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 4167–4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu G; Prabhakar A; Aucoin D; Simon M; Sparks S; Robbins KJ; Sheen A; Petty SA; Lazo ND Mechanistic Studies of Peptide Self-Assembly: Transient α-Helices to Stable β-Sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 18223–18232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Westermark P; Andersson A; Westermark GT Islet Amyloid Polypeptide, Islet Amyloid, and Diabetes Mellitus. Physiol. Rev 2011, 91, 795–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kiriyama Y; Nochi H Role and Cytotoxicity of Amylin and Protection of Pancreatic Islet β-Cells from Amylin Cytotoxicity. Cells 2018, 7, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Akter R; Cao P; Noor H; Ridgway Z; Tu LH; Wang H; Wong AG; Zhang X; Abedini A; Schmidt AM; Raleigh DP Islet Amyloid Polypeptide: Structure, Function, and Pathophysiology. J. Diabetes Res 2016, 2016, 2798269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lorenzo A; Razzaboni B; Weir GC; Yankner BA Pancreatic Islet Cell Toxicity of Amylin Associated with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nature 1994, 368, 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Last NB; Schlamadinger DE; Miranker AD A Common Landscape for Membrane-Active Peptides. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 870–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mukherjee A; Morales-Scheihing D; Butler PC; Soto C Type 2 Diabetes as a Protein Misfolding Disease. Trends Mol. Med 2015, 21, 439–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zraika S; Hull RL; Verchere CB; Clark A; Potter KJ; Fraser PE; Raleigh DP; Kahn SE Toxic Oligomers and Islet β Cell Death: Guilty by Association or Convicted by Circumstantial Evidence? Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1046–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jayasinghe SA; Langen R Membrane Interaction of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2007, 1768, 2002–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rawat A; Langen R; Varkey J Membranes as Modulators of Amyloid Protein Misfolding and Target of Toxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2018, 1860, 1863–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Birol M; Kumar S; Rhoades E; Miranker AD Conformational Switching within Dynamic Oligomers Underpins Toxic Gain-of-Function by Diabetes-Associated Amyloid. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Williamson JA; Miranker AD Direct Detection of Transient α-Helical States in Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Abedini A; Raleigh DP A Critical Assessment of the Role of Helical Intermediates in Amyloid Formation by Natively Unfolded Proteins and Polypeptides. Protein Eng., Des. Sel 2009, 22, 453–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Abedini A; Plesner A; Cao P; Ridgway Z; Zhang J; Tu LH; Middleton CT; Chao B; Sartori DJ; Meng F; Wang H; Wong AG; Zanni MT; Verchere CB; Raleigh DP; Schmidt AM Time-Resolved Studies Define the Nature of Toxic IAPP Intermediates, Providing Insight for Anti-Amyloidosis Therapeutics. eLife 2016, 5, 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Jayasinghe SA; Langen R Lipid Membranes Modulate the Structure of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 12113–12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Williamson JA; Loria JP; Miranker AD Helix Stabilization Precedes Aqueous and Bilayer-Catalyzed Fiber Formation in Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. J. Mol. Biol 2009, 393, 383–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Nanga RP; Brender JR; Vivekanandan S; Ramamoorthy A Structure and Membrane Orientation of IAPP in Its Natively Amidated Form at Physiological pH in a Membrane Environment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2011, 1808, 2337–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kegulian NC; Sankhagowit S; Apostolidou M; Jayasinghe SA; Malmstadt N; Butler PC; Langen R Membrane Curvature-Sensing and Curvature-Inducing Activity of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide and Its Implications for Membrane Disruption. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 25782–25793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Knight JD; Hebda JA; Miranker AD Conserved and Cooperative Assembly of Membrane-Bound α-Helical States of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 9496–9508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bram Y; Frydman-Marom A; Yanai I; Gilead S; Shaltiel-Karyo R; Amdursky N; Gazit E Apoptosis Induced by Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Soluble Oligomers Is Neutralized by Diabetes-Associated Specific Antibodies. Sci. Rep 2015, 4, 4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wada A The α-Helix as an Electric Macro-Dipole. Adv. Biophys 1976, 1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hol WG; van Duijnen PT; Berendsen HJ The α-Helix Dipole and the Properties of Proteins. Nature 1978, 273, 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kuipers BJ; Gruppen H Prediction of Molar Extinction Coefficients of Proteins and Peptides Using UV Absorption of the Constituent Amino Acids at 214 nm to Enable Quantitative Reverse Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem 2007, 55, 5445–5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).de Planque MR; Raussens V; Contera SA; Rijkers DT; Liskamp RM; Ruysschaert JM; Ryan JF; Separovic F; Watts A β-Sheet Structured β-Amyloid(1–40) Perturbs Phosphatidylcholine Model Membranes. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 368, 982–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Robbins KJ; Liu G; Lin G; Lazo ND Detection of Strongly Bound Thioflavin T Species in Amyloid Fibrils by Ligand-Detected 1H NMR. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2011, 2, 735–740. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Greenfield NJ Using Circular Dichroism Spectra to Estimate Protein Secondary Structure. Nat. Protoc 2006, 1, 2876–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Whitmore L; Wallace BA Protein Secondary Structure Analyses from Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy: Methods and Reference Databases. Biopolymers 2008, 89, 392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lazo ND; Downing DT Circular Dichroism of Model Peptides Emulating the Amphipathic α-Helical Regions of Intermediate Filaments. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 2559–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Chen YH; Yang JT; Chau KH Determination of the Helix and Beta Form of Proteins in Aqueous Solution by Circular Dichroism. Biochemistry 1974, 13, 3350–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Sakagashira S; Sanke T; Hanabusa T; Shimomura H; Ohagi S; Kumagaye KY; Nakajima K; Nanjo K Missense Mutation of Amylin Gene (S20G) in Japanese NIDDM Patients. Diabetes 1996, 45, 1279–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sakagashira S; Hiddinga HJ; Tateishi K; Sanke T; Hanabusa T; Nanjo K; Eberhardt NL S20G Mutant Amylin Exhibits Increased in Vitro Amyloidogenicity and Increased Intracellular Cytotoxicity Compared to Wild-Type Amylin. Am. J. Pathol 2000, 157, 2101–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Sugiura Y; Ikeda K; Nakano M High Membrane Curvature Enhances Binding, Conformational Changes, and Fibrillation of Amyloid-β on Lipid Bilayer Surfaces. Langmuir 2015, 31, 11549–11557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Terakawa MS; Lin Y; Kinoshita M; Kanemura S; Itoh D; Sugiki T; Okumura M; Ramamoorthy A; Lee YH Impact of Membrane Curvature on Amyloid Aggregation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 1741–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Caillon L; Lequin O; Khemtemourian L Evaluation of Membrane Models and Their Composition for Islet Amyloid Polypeptide-Membrane Aggregation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2013, 1828, 2091–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Rustenbeck I; Matthies A; Lenzen S Lipid Composition of Glucose-Stimulated Pancreatic Islets and Insulin-Secreting Tumor Cells. Lipids 1994, 29, 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Engel MF; Khemtemourian L; Kleijer CC; Meeldijk HJ; Jacobs J; Verkleij AJ; de Kruijff B; Killian JA; Hoppener JW Membrane Damage by Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide through Fibril Growth at the Membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 6033–6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Korshavn KJ; Satriano C; Lin Y; Zhang R; Dulchavsky M; Bhunia A; Ivanova MI; Lee YH; La Rosa C; Lim MH; Ramamoorthy A Reduced Lipid Bilayer Thickness Regulates the Aggregation and Cytotoxicity of Amyloid-β. J. Biol. Chem 2017, 292, 4638–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Kumar S; Schlamadinger DE; Brown MA; Dunn JM; Mercado B; Hebda JA; Saraogi I; Rhoades E; Hamilton AD; Miranker AD Islet Amyloid-Induced Cell Death and Bilayer Integrity Loss Share a Molecular Origin Targetable with Oligopyridylamide-Based α-Helical Mimetics. Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Cao P; Abedini A; Wang H; Tu LH; Zhang X; Schmidt AM; Raleigh DP Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Toxicity and Membrane Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 19279–19284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Holzwarth G; Doty P The Ultraviolet Circular Dichroism of Polypeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1965, 87, 218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Comellas G; Lemkau LR; Zhou DH; George JM; Rienstra CM Structural Intermediates During α-Synuclein Fibrillogenesis on Phospholipid Vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 5090–5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Cholak E; Bucciarelli S; Bugge K; Johansen NT; Vestergaard B; Arleth L; Kragelund BB; Langkilde AE Distinct α-Synuclein:Lipid Co-Structure Complexes Affect Amyloid Nucleation through Fibril Mimetic Behavior. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 5052–5065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Monsellier E; Bousset L; Melki R α-Synuclein and Huntingtin Exon 1 Amyloid Fibrils Bind Laterally to the Cellular Membrane. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 19180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Sanguanini M; Baumann KN; Preet S; Chia S; Habchi J; Knowles TPJ; Vendruscolo M Complexity in Lipid Membrane Composition Induces Resilience to Aβ42 Aggregation. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2020, 11, 1347–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Rideau E; Dimova R; Schwille P; Wurm FR; Landfester K Liposomes and Polymersomes: A Comparative Review Towards Cell Mimicking. Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 8572–8610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Vander Zanden CM; Wampler L; Bowers I; Watkins EB; Majewski J; Chi EY Fibrillar and Nonfibrillar Amyloid Beta Structures Drive Two Modes of Membrane-Mediated Toxicity. Langmuir 2019, 35, 16024–16036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Hellstrand E; Nowacka A; Topgaard D; Linse S; Sparr E Membrane Lipid Co-Aggregation with α-Synuclein Fibrils. PLoS One 2013, 8, e77235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Pannuzzo M; Raudino A; Milardi D; La Rosa C; Karttunen M α-Helical Structures Drive Early Stages of Self-Assembly of Amyloidogenic Amyloid Polypeptide Aggregate Formation in Membranes. Sci. Rep 2013, 3, 2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Fezoui Y; Teplow DB Kinetic Studies of Amyloid β-Protein Fibril Assembly - Differential Effects of α-Helix Stabilization. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 36948–36954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Abedini A; Raleigh DP A Role for Helical Intermediates in Amyloid Formation by Natively Unfolded Polypeptides? Phys. Biol 2009, 6, 015005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Bigay J; Antonny B Curvature, Lipid Packing, and Electrostatics of Membrane Organelles: Defining Cellular Territories in Determining Specificity. Dev. Cell 2012, 23, 886–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Sengupta D; Behera RN; Smith JC; Ullmann GM The α Helix Dipole: Screened Out? Structure 2005, 13, 849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Fitzpatrick AWP; Falcon B; He S; Murzin AG; Murshudov G; Garringer HJ; Crowther RA; Ghetti B; Goedert M; Scheres SHW Cryo-EM Structures of Tau Filaments from Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2017, 547, 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Gremer L; Scholzel D; Schenk C; Reinartz E; Labahn J; Ravelli RBG; Tusche M; Lopez-Iglesias C; Hoyer W; Heise H; Willbold D; Schroder GF Fibril Structure of Amyloid-β(1–42) by Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Science 2017, 358, 116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Wang J; Videla PE; Batista VS Effects of Aligned α-Helix Peptide Dipoles on Experimental Electrostatic Potentials. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1692–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.