Abstract

Objectives:

To explore temporal trends and geographic variations in mortality from prescription opioids from 1999 to 2016.

Methods:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research Multiple Cause of Death files were used to calculate age-adjusted rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and create spatial cluster maps.

Results:

From 1999 to 2016, counties in West Virginia experienced the highest overall mortality rates in the United States from prescription opioids. Specifically, from 1999 to 2004, the highest rate in West Virginia of 24.87/100,000 (95% CI 17.84–33.73) was the fourth highest in the United States. From 2005 to 2009, West Virginia experienced the highest rate in the United States, 60.72/100,000 (95% CI 47.33–76.71). From 2010 to 2016, West Virginia also experienced the highest rate in the United States, which was 90.24/100,000 (95% CI 73.11–107.36). As such, overall, West Virginia experienced the highest rates in the United States and the largest increases overall of ~3.6-fold between 1999 and 2004 and 2010 and 2016. From 1999 to 2004, Florida had no “hot spots,” but from 2006 to 2010 they did appear, and from 2011 to 2016, they disappeared.

Conclusions:

These data show markedly divergent temporal trends and geographic variations in mortality rates from prescription opioids, especially in the southern United States. Specifically, although initial rates were high and continued to increase alarmingly in West Virginia, they increased but then decreased in Florida. These descriptive data generate hypotheses requiring testing in analytic epidemiological studies. Understanding the divergent patterns of prescription opioid-related deaths, especially in West Virginia and Florida, may have important clinical and policy implications.

Keywords: geographic variations, mortality, prescription opioids, temporal trends

In the United States, mortality from drug overdoses has become a major contributor to the current highest overall death rates in more than a century. Since 1999, the mortality rates from drug overdoses in the United States have more than tripled.1 Specifically, deaths from prescription opioids have become a major contributor following the adoption of new standards of pain management, including consideration of pain as a fifth vital sign beginning in 2000.2,3 These circumstances have contributed, at least in part, to the rapid expansion of both inpatient and outpatient prescription opioid use. These circumstances also have contributed to the increased occurrence of opioid use disorder (OUD) and alarming increasing mortality rates from prescription opioids.2

In the context of overall opioid prescribing history, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 (Public Law 63–223) outlined laws and taxes intended to regulate opioid distribution.2 In 1961, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs established criteria for countries that included restrictions on the prescription of opioids.4 Healthcare providers rarely prescribed opioids because of concerns about addiction. In 1986, however, on the basis primarily of the desire to humanly manage the pain of patients with cancer, the World Health Organization identified the pain treatment as a universal right and developed cancer pain treatment guidelines.2

With the release of the report from The Joint Commission, pain began to be considered the fifth vital sign. In addition, more aggressive treatment of chronic pain through the expanded prescription of opioids was promoted by opioid manufacturers. For example, in 1996, Purdue Pharma began to market OxyContin, claiming, “Minimal risk for iatrogenic addiction.”5,6 From 1998 to 2000, successful marketing campaigns led to the expanded prescription of opioids throughout the United States. In some states such as Alabama, Kentucky, Maine, Virginia, and West Virginia, opioid prescription levels already were 2.5 to 5 times higher than the national average, and the introduction of OxyContin led to prescription rates that were 5 to 6 times higher. An epidemic of prescription opioid-related mortality followed.6

Between 2010 and 2012, opioid prescriptions were at their highest in the United States.7 Although generally declining since then, the dosage of opioids prescribed in morphine milligram equivalents remains about 3 times higher in 2017 than it was in 1999.7 In addition, from 2002 to 2015, there was a 2.6-fold increase in the number of prescription opioid overdoses and a 5.6-fold increase in synthetic opioid deaths not including methadone.8 Drug overdoses accounted for approximately 70,000 annual premature deaths in 2017, nearly 68% of which involved an opioid.9 Finally, although the opioid epidemic is a national health crisis, some areas of the United States are disproportionately affected. The availability of mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) afforded a unique opportunity to explore temporal trends and geographic variations in mortality from prescription opioids.

Methods

Data Collection

The data for this study are administered by the Office of Analysis and Epidemiology of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the CDC on its Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (more commonly known as WONDER) Web site.10 This site provides crude and age-adjusted US cause of death mortality rates (95% confidence intervals and standard errors) and population estimates according to location (urbanization, counties, and larger geographic units), demographics (age at death, race, sex, and Hispanic ethnicity), time of death (year, month, and day of the week), place of death (medical care facility, home, hospice, nursing facility, or other), and whether an autopsy was performed. Death certificates are issued for decedents who are legal residents of the United States, and the certificates are estimated to capture 99% of all such deaths.11 Residence is considered to be the place where the decedent actually resided (that is, not the “home state,” legal residence, or a temporary location such as may occur on a visit business trip or vacation). Although the location of an acute care hospital is not used as “residence,” group homes, mental institutions, nursing facilities, penitentiaries, or hospitals for chronically ill people may be used. Locations during a military tour or college attendance are considered permanent and are entered for place of residence as appropriate.12 US citizens who live outside the United States may be issued a US death certificate, but their place of residence is specified as “non-US.”13

For these analyses we used the Multiple Cause of Death files, focusing on age-adjusted, county rates. The Multiple Cause files include deaths that were considered either underlying or contributory (1 of up to 20 additional causes of death).10 The use of multiple cause data avoids undercounts that may occur if rates were based on underlying cause alone. Age-adjusted rates in these data are calculated by the National Center for Health Statistics using the direct method and a year-2000 standard population.14 The age groups used for age-adjusted rates were younger than 1 year and 1–4, 5–14, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 74–84, and 85 years and older. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, codes for prescription opioids were those specified by the CDC,15 specifically T40.2 (natural and semisynthetic opioids) and T40.3 (methadone). A list of the 10th edition codes used in these descriptions is available in the Supplemental Digital Content at http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A180. This research was classified as exempt by the institutional review board of the Baylor College of Medicine.

Mapping

We generated maps from the age-adjusted rates using the ArcGIS Pro Advanced software through Esri Optimized Hot Spot Analysis (Esri, Redlands, CA). We generated maps of statistically significant spatial clusters of high values—“hot spots”—using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic.16 This statistic works by taking into account both the value of the feature itself (in this case, the rate of prescription opioid overdose in US counties with sufficient data) and the comparable values of the neighboring features.16 This method of analysis works by considering the features (here, rates by counties) in the context of neighboring features in which a z score and a P value are used to determine statistical significance, and as such, problems with multiple testing and dependency must be accounted for.16 The optimization features implement the appropriate scale of analysis and correct for spatial dependence and multiple testing through false discovery rate correction.16 Maps were generated for the rates of prescription opioid overdoses in 3 major time periods: 1999–2004, 2005–2010, and 2010–2016. Counties were excluded from analysis if the data were unavailable or deemed unreliable (based on <20 deaths) by the National Center for Health Statistics. This research was classified as exempt by the institutional review board.

Results

From 1999 to 2016, counties in West Virginia experienced the highest overall mortality rates in the United States from prescription opioids. Specifically, from 1999 to 2004, the highest rate in West Virginia of 24.87/100,000 (95% confidence interval [CI] 17.84–33.73) was the fourth highest in the United States; from 2005 to 2009, West Virginia experienced the highest rate in the United States of 60.72/100,000 (95% CI 47.33–76.71); and from 2010 to 2016, West Virginia also experienced the highest rate in the United States, which was 90.24/100,000 (95% CI 73.11–107.36). As such, overall, West Virginia experienced the highest rates in the country, as well as most of the largest increases including one of approximately 3.6 fold between the highest county rate of 1999 to 2004 and 2010 to 2016. More generally, from 1999 to 2004, Appalachia, an area defined as being along the Appalachian Mountains and the surrounding area, primarily West Virginia and the Southwest (primarily Utah) had the highest rates. From 2005 to 2010, these high rates increased further in these regions, and new hot spots appeared in Florida and Oklahoma. Between 2011 and 2016, hot spots continued to persist and expand further in Appalachia and the Southwest, but they disappeared in Florida and Oklahoma.

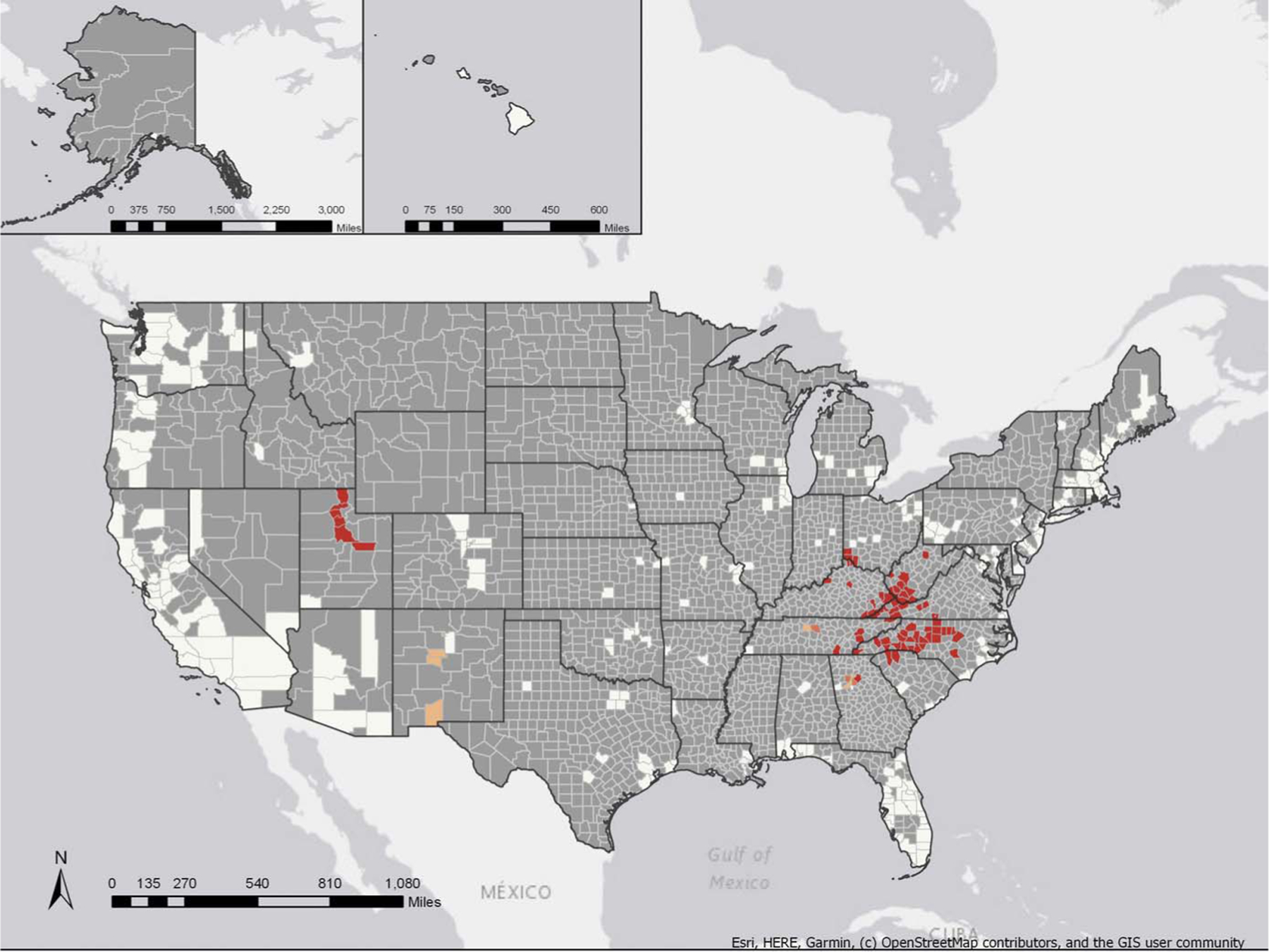

Figure 1 shows that from 1999 to 2004, 337 counties had sufficient data, defined as at least 20 deaths from prescription opioids, for hot spot analysis. Of these, 78 were identified with at least 90% confidence as hot spots. Among the hot spots, the 10 counties with the highest mortality rates were located in Virginia (4), West Virginia (3), Utah (1), Kentucky (1), and North Carolina (1). Other counties with hot spots were apparent in Georgia (4), Kentucky (9), New Mexico (3), North Carolina (25), Ohio (3), South Carolina (2), Tennessee (6), Utah (6), Virginia (10), and West Virginia (10).

Fig. 1.

Hot spot analysis of age-adjusted mortality rates from prescription opioids in US counties, 1999–2004, with reliable rates. White, not significant; light orange, 90% confidence; medium orange, 95% confidence; dark orange, 99% confidence; gray, insufficient data.

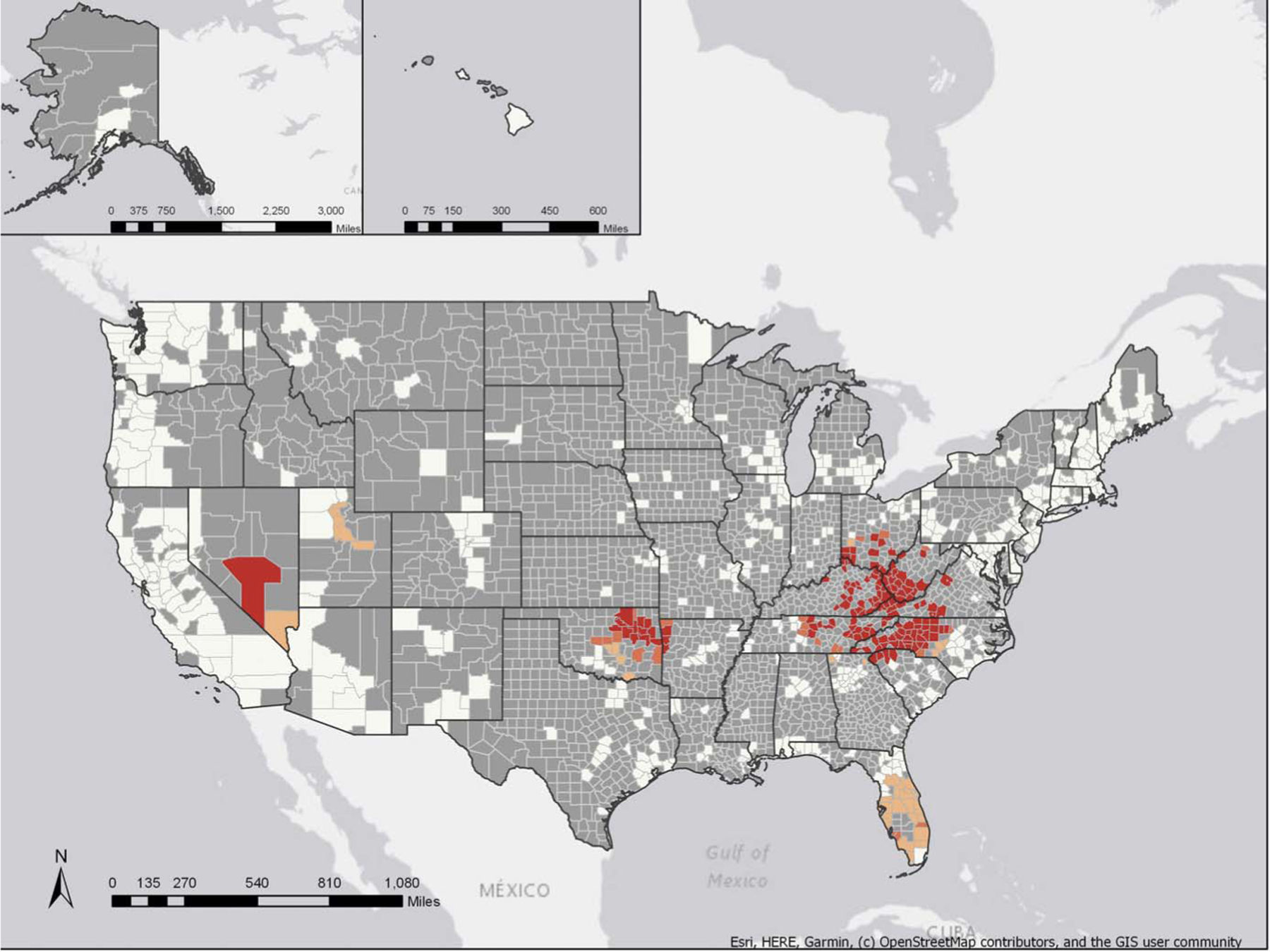

Figure 2 shows that from 2005 to 2010, 698 counties had sufficient data for hot spot analysis. Of these, 200 were identified with at least 90% confidence as hot spots. The 10 counties with the highest mortality rates were in West Virginia (5) and Kentucky (5). From 2005 to 2010, there was a much wider spread of hot spots across the United States, including the counties identified from 1999 to 2005 and new counties in Arkansas (4), Florida (22), Nevada (2), and Oklahoma (20).

Fig. 2.

Hot spot analysis of age-adjusted mortality rates from prescription opioids in US counties, 2005–2010, with reliable rates. White, not significant; light orange, 90% confidence; medium orange, 95% confidence; dark orange, 99% confidence; gray, insufficient data.

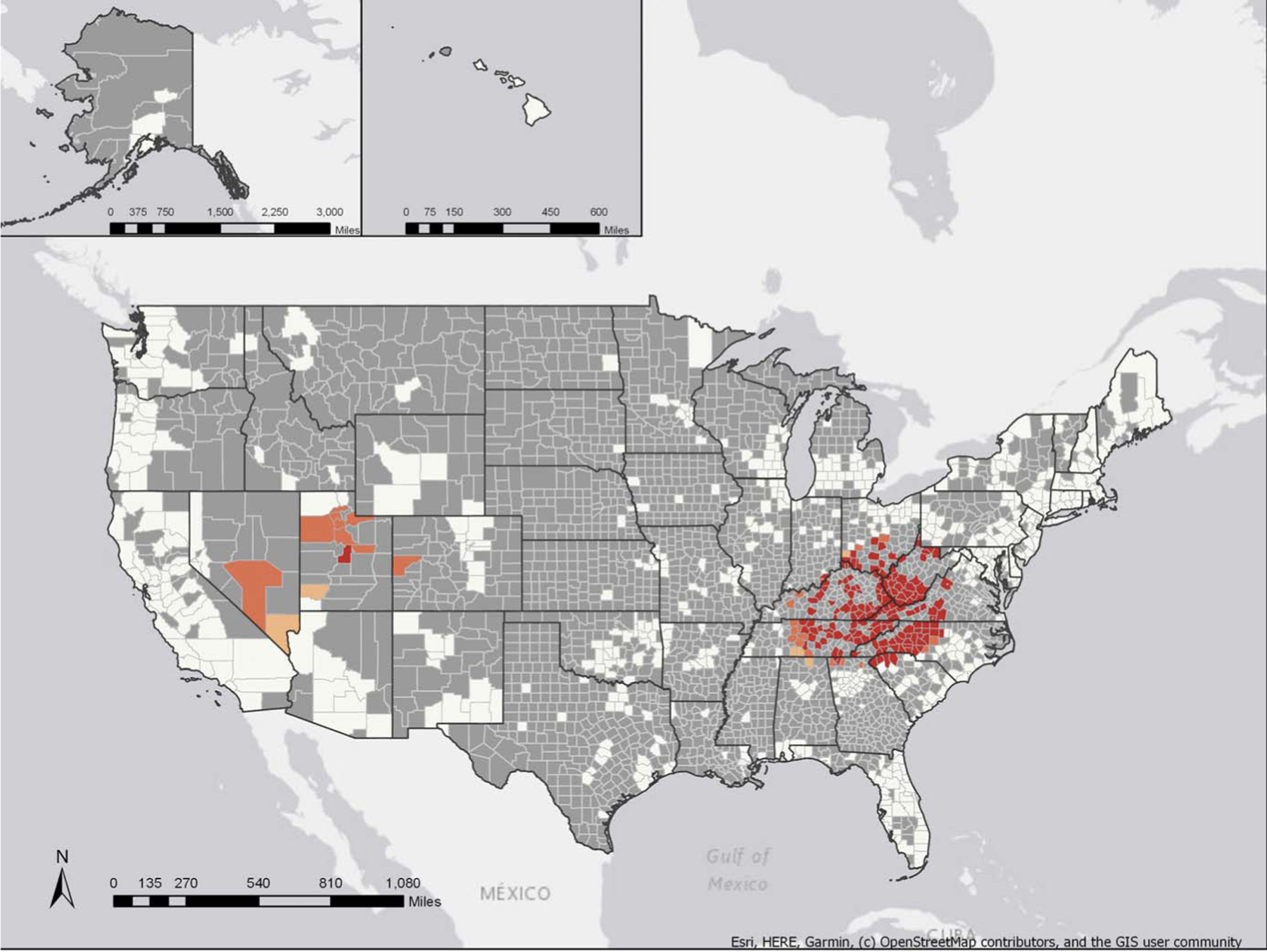

Figure 3 shows that from 2011 to 2016, 819 counties had sufficient data for hot spot analysis. Of these, 188 were identified with at least 90% confidence as hot spots. The 10 counties with the highest mortality rates were in West Virginia (6), Kentucky (3), and Utah (1). The states with hot spot counties included Alabama (1), Colorado (1), Georgia (5), Indiana (2), Kentucky (40), Nevada (2), North Carolina (30), Ohio (14), South Carolina (4), Tennessee (39), Utah (9), Virginia (16), and West Virginia (25). The highest countywide rate was Wyoming County in West Virginia, with 90.24 deaths per 100,000 that showed a steady increase, from 16.78 deaths per 100,000 in the 1999–2004 map to 55.44 deaths per 100,000 in the 2005–2010 map. West Virginia counties had the six highest rates of mortality from prescription opioids, whereas the hot spots disappeared from all of the Florida and Oklahoma counties previously identified as being hot spots.

Fig. 3.

Hot spot analysis of age-adjusted mortality rates from prescription opioids in US counties, 2011–2016, with reliable rates. White, not significant; light orange, 90% confidence; medium orange, 95% confidence; dark orange, 99% confidence; gray, insufficient data.

Discussion

These data show markedly divergent temporal trends and geographic variations in mortality rates from prescription opioids, especially in the southern United States. Specifically, although initial rates were high and continued to increase most markedly in West Virginia, they later increased and then decreased in Florida.

The states of the Appalachian region were consistently identified as hot spots, with increasing rates throughout this 18-year period. Among the potential hypotheses about why this particular region is experiencing such consistently high mortality rates are socioeconomic factors and variations in prescribing practices or insurance practices affecting both the use and misuse of these drugs (the states of Florida and Oklahoma were identified as hot spots only from 2005 to 2010).

In marked contrast to the experience in West Virginia counties, the rates in Florida counties either increased minimally or decreased during the period from 2011 to 2016. These findings are compatible with the hypothesis of a positive change in combating the opioid epidemic in Florida. It is also plausible, however, that these results reflect a secular change in mortality from prescription opioids to mortality from heroin. With respect to the former, Florida has implemented opioid public policy changes that have been examined in a prior study.17 Florida instituted the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program and a pill mill law in 2010.18 Two years later, Florida reported a >50% decrease in oxycodone-related overdoses, which represented one of the first documented substantial declines in prescription opioid-related mortality during the previous 10 years.19 In regard to the latter, the number of deaths resulting from the use of illegal opioids in Florida increased dramatically from 200 overdose deaths in 2013 to 1566 deaths in 2016.20 These results could suggest altered prescription practices, and state policy changes could be effective in curbing prescription opioid-related deaths but also could produce the unintended consequence of increasing heroin/fentanyl-related overdoses as suggested by other recent data.21 Florida is continuing to develop policies to combat the opioid epidemic. These new policies include a law passed in 2017 to improve the collection and availability of overdose data22 and a law passed in 2018 dictating stricter prescribing practices for acute pain treatment in the state.23 It is unknown yet how these new laws will affect both prescription and illicit opioid mortality rates and patients’ access to pain treatment, but the changes theoretically will limit the use of opioids for acute pain treatment, potentially affecting the number of new patients who develop an OUD. As Florida continues to implement new policies to combat the epidemic, especially in regard to prescriptions, the trends observed in these descriptive data may continue, with questions on how to prevent a potential conversion of increased prescription opioid mortality to increased illicit opioid mortality.

Oklahoma was likewise identified as having the highest percentage of nonmedical use of prescription painkillers, with >8% of the population 12 years of age or older misusing in 2010, and it also had one of the highest rates of painkiller sales per capita in the country.24 Between 2011 and 2016, Oklahoma instituted a variety of opioid policies including new doctors’ requirements for methadone prescription in 2010, altered guidelines for prescribing opioids in emergency departments and urgent care clinics in 2013, new guidance on prescribing opioids for healthcare providers in an office setting in 2014, and quantity limits on chronic opioid prescriptions for the state’s Medicaid program in 2014.25 Our descriptive data, along with policy and practice changes, support the possibilities that expanded and enhanced guidance for prescription opioids may have contributed to the reduction of hot spots in Florida and Oklahoma from 2011 to 2016.

These descriptive data contribute to the formulation of many hypotheses. For example, declines in prescription drug deaths may reflect a transition to nonprescription drugs as the availability of prescriptions declined. There are observations to support this hypothesis in Florida (Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/SMJ/A180), in which 20 of 27 counties with available data experienced a statistically significant increase in nonprescription opioid deaths from 2005 to 2010 and 2011 to 2016. Death certificate data do not provide information about whether the decedent had previously used prescription opioids, however. Another plausible hypothesis concerns the type of provider from whom prescriptions were obtained. In this regard, the Health Resources and Services Administration Area Health Resource Files26 identify Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia—all areas with high rates of prescription opioid deaths in the present data—as among those with the highest number of nurse practitioners per 100,000 population in the United States. In addition, in Oregon, patients of nurse practitioners and naturopathic doctors received more high-risk opioid prescriptions than those under the care of medical doctors, doctors of osteopathy, and physician assistants.27 The authors concluded that these differences appear largely because of differences in patient mix between provider types rather than discipline-specific prescribing practices.

There are several limitations to these descriptive data that merit consideration. First, the data are limited to mortality from prescription opioids, which constitute only a part of the growing epidemic. Second, some studies have shown that as the prescription opioid epidemic decreases in some areas with social and public policy changes, the epidemic of the often more lethal illicit opioids grows.21 As such, future considerations about the complexities of the prescription opioid epidemic may require region-specific research strategies and public health policies. Additional limitations include the fact that some counties provided insufficient data, defined as <20 reported deaths. This is a potential source of bias in that counties are included only if they report sufficient data on the subject of prescription opioids. These data also included only circumstances in which opioid overdose was listed on the death certificate; therefore, actual rates may be higher than those indicated in this report, although the use of the Multiple Cause of Death files may have had a mitigating effect on this potential bias. With additional regard to differences in death certificates, there are differences in drug-overdose reporting in states throughout the United States. In addition, there appear to have been improvements in reporting drug-specific overdoses in recent years.

Despite these and other possible limitations, we believe the most plausible interpretation of the data to be that from 1999 to 2016, Appalachia in general and West Virginia in particular had consistently unfavorable experiences with mortality rates from prescription opioids, whereas Florida and Oklahoma showed more favorable experiences that may, at least in theory, have been caused, at least in part, by shifts from legal to illegal sources of these drugs but also implemented public policy changes.

Conclusions

Death is inevitable, but premature death is not; therefore, the increasing epidemic of mortality from prescription opioids is emerging as another major avoidable cause of premature death in the United States. The observed temporal trends and geographic variations in prescription opioid-related mortality may allow for more targeted approaches to combating this crisis. The epidemic of OUD is one of the most recently developed and prominent public health crises, and as a result, many public health policies are still being developed. The knowledge gained from the contrasting experiences, especially in West Virginia and Florida, is likely to have major public health implications in predicting both the benefits and unintended harms of prescription opioid policies designed to curb the opioid crisis. In addition to such policies, there is an urgent need for further basic research to identify vulnerable individuals at risk of developing OUD. If developed, then the prescription of opioids could be accompanied by intensive monitoring and counseling of pain patients or strict avoidance in favor of interventional procedures and nonopioid or nonpharmacological methods for pain management. Genomic and precision medicine strategies have the potential to minimize the risk of developing opioid addiction and markedly reduce the epidemic of high mortality rates from prescription opioids.28

In summary, these descriptive data generate hypotheses requiring testing in analytic epidemiological studies. Understanding the divergent patterns of prescription opioid-related deaths, especially in West Virginia and Florida, may have important clinical and policy implications.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

From 1999 to 2016, “hot spots” in West Virginia showed the highest county mortality rates from prescription opioids.

From 2005 to 2010, hot spots developed in Florida, which disappeared from 2011 to 2016.

Understanding the divergent patterns of prescription opioid-related deaths, especially in West Virginia and Florida, may have important clinical and policy implications.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by investigator-initiated research grants from National Institutes of Health grants R01 DA044015 and 5R01GM114665.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (http://sma.org/smj-home).

References

- 1.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tompkins DA, Hobelmann JG, Compton P. Providing chronic pain management in the “fifth vital sign” era: historical and treatment perspectives on a modern-day medical dilemma. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;173:S11–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker DW. History of The Joint Commission’s pain standards. Lesson’s for today’s prescription opioid epidemic. JAMA 2017;317:1117–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohman D, Schleifer R, Amon JJ. Access to pain treatment as a human right. BMC Med 2010;8:8(2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter J, Jick H. Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. N Engl J Med 1980;302:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Zee A. The promotion and marketing of OxyContin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy. Am J Public Health 2009;99:221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandel DB, Hu M-C, Griesler P, et al. Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;178:501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colon-Berezin C, Nolan ML, Blachman-Forshay J, et al. Overdose deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs—New York City, 2000–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Multiple Cause of Death file: 1999–2017 https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed November 3, 2018.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1989;38: 119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. standard certificate of death https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/DEATH11-03final-acc.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- 13.USAGov. Issues with family outside the U.S https://www.usa.gov/family-outside-us. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- 14.Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. Natl Vital Stat Rep 1998;47:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seth P, Rudd RA, Noonan RK, et al. Quantifying the epidemic of prescription opioid overdose deaths. Am J Public Health 2018;108:500–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esri. Optimized hot spot analysis. ArcMap http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/tools/spatial-statistics-toolbox/optimized-hot-spot-analysis.htm. Accessed December 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Richey M, McGinty EE, et al. Opioid overdose deaths and Florida’s crackdown on pill mills. Am J Public Health 2016; 106:291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutkow L, Chang H-Y, Daubresse M, et al. Effect of Florida’s prescription drug monitoring program and pill mill laws on opioid prescribing and use. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson H, Paulozzi L, Porucznik C, et al. Decline in drug overdose deaths after state policy changes—Florida, 2010–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:569–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Florida: opioid summaries by state https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state/florida-opioid-summary. Revised May 2019. Accessed January 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling health benefits and harms of public policy responses to the US opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health 2018;108:1394–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Florida Senate, Health and Human Services Committee, Health Quality Subcommittee, et al. CS/CS/HB 249: Drug Overdoses; 2017 https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2017/0249. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 23.Florida Senate, Health and Human Services Committee, Health Quality Subcommittee, et al. CS/CS/HB 21: Controlled Substances; 2018 https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2018/21. Accessed March 3, 2019.

- 24.Sykes A, Derby D, Faught G, et al. Compliance and best practice for an act regulating the use of opioid drugs. Oklahoma Senate Bills 1446 & 848 Accessed January 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martz MP, Ruberto I, Ampadu L, et al. 50 state review on opioid related policy https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/prevention/womens-childrens-health/injury-prevention/opioid-prevention/50-state-review-printer-friendly.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed December 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Area Health Resources Files. Nurse practitioners. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf. Accessed October 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink PB, Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, et al. Opioid prescribing patterns and patient outcomes by prescriber type in the Oregon Prescription Drug Monitoring Program. Pain Med 2018;19:2481–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robishaw J, Caceres J, Hennekens CH. Genomics and precision medicine to combat opioid use disorder. Am J Med 2019;132:395–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.