Abstract

The advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeted therapy revolutionized the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients. However, cardiotoxicity associated with these targeted therapies puts the cancer survivors at higher risk. Ponatinib is a third-generation TKI for the treatment of CML patients having gatekeeper mutation T315I, which is resistant to the first and second generation of TKIs, namely, imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib. Multiple unbiased screening from our lab and others have identified ponatinib as most cardiotoxic FDA approved TKI among the entire FDA approved TKI family (total 50+). Indeed, ponatinib is the only treatment option for CML patients with T315I mutation. This review focusses on the cardiovascular risks and mechanism/s associated with CML TKIs with a particular focus on ponatinib cardiotoxicity. We have summarized our recent findings with transgenic zebrafish line harboring BNP luciferase activity to demonstrate the cardiotoxic potential of ponatinib. Additionally, we will review the recent discoveries reported by our and other laboratories that ponatinib primarily exerts its cardiotoxicity via an off-target effect on cardiomyocyte prosurvival signaling pathways, AKT and ERK. Finally, we will shed light on future directions for minimizing the adverse sequelae associated with CML-TKIs.

Keywords: Ponatinib, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Cardiotoxicity, Cardio-oncology

Introduction:

Over the past 30 years, the care of cancer patients has advanced [1, 2]. On the contrary, many agents in anticancer drugs have cardiotoxic manifestations due to which a significant percentage of cancer patients are suffering from adverse effects of cancer therapeutics. Patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disorders are at higher risk of drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Therefore, there is a desperate need for strategies to identify and overcome cardiotoxicity during cancer therapy. This recognition has culminated in the inception of a multidisciplinary field: known as cardio-oncology. The primary goals of the rapidly growing discipline of cardio-oncology are to better understand the pathophysiology of cancer therapy-associated cardiotoxicity and to provide early prediction, detection, management, and treatment of cardiac complications in patients with, or who survive cancer. Importantly, the majority of CML patients have to live with cancer and requires daily medication. Only a few CML patients can approach to stop TKI treatment and maintain a state of “treatment-free remission” (TFR). Only this small fraction of CML patients fall in the category of “cancer survivors.” This need for a lifelong treatment further enhances the probabilities of drug-induced toxicity. An obstruction in the field has been the lack of an appropriate model system to perform preclinical studies for accurate prediction of cardiotoxicity in humans [3]. Extensive efforts have been made to understand the mechanism of chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy, and maximum information was derived from anthracyclines. However, the frequency of molecular targeted therapies-induced cardiotoxicity is largely unknown and potentially underestimated.

Targeted therapies are highly effective in the treatment of cancer and have significantly improved the life expectancy of cancer patients. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) signifies a remarkable success story in the era of targeted therapy. CML affects 1-2 out of every 100, 000 adults. The disease represents 15% of new cases of leukemia in adults. An estimated 60,530 new cases of leukemia will be diagnosed in the US in 2020 [4]. CML is associated with the reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 (t(9;22) or Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome resulting in the breakpoint cluster region-Abelsonl (BCR-ABL1) fusion gene [5, 6]. This oncoprotein is a continuously produced active tyrosine kinase which promotes growth via downstream signaling pathways, for example, RAS, RAF, MYC, and STAT.

The constitutive activity of the oncogenic BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase is the primary cause of CML progression and, thus, serves as an ideal molecule for targeted therapy [7–11]. Numerous TKIs, including imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, and ponatinib, have targeted this kinase.

Undeniably, targeted inhibition of BCR-ABL1 with TKIs has led to an improvement in the survivorship of patients diagnosed with CML. Unfortunately, these TKIs are also lead to unwanted adverse cardiovascular effects (Table 1). Notably, several recent reports have suggested that ponatinib is the most cardiotoxic agent in all FDA approved TKIs ([12, 13]. Since there is no alternative treatment option for CML patients with the T315I mutation, at present, the only hope is to better understand the molecular mechanism of ponatinib-induced cardiotoxicity and develop strategies to prevent/treat adverse effect. Herein, we focused on discussing the ponatinib associated cardiotoxic effects, current understanding of the molecular mechanism.

Table 1:

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and related cardiac adverse events

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Cardiac adverse events | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Imatinib | Edema, pericardial effusion, peripheral edema, pulmonary edema, angina pectoris, hypotension, palpitation, flushing, arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, tachycardia, cardiac tamponade, acute coronary syndromes, HF, left ventricular dysfunction, cardiogenic shock, hypertension, MI, pericarditis, thrombosis |

[16, 29–32] |

| Nilotinib | Peripheral edema, hypertension, arterial stenosis, QTc prolongation, sudden death, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial occlusive disease, ischemic cerebrovascular events, angina pectoris, arrhythmia (AV block, atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, cardiac flutter, extrasystoles, tachycardia), palpitations, flushing, pericardial effusion, aortic valve sclerosis, arteriosclerosis, HF, cardiomegaly, MI, pulmonary edema | [33–38] |

| Dasatinib | QTc prolongation, angina pectoris, pericardial effusion, left ventricular dysfunction, HF, cardiomyopathy, diastolic dysfunctions, fatal MI, pericardial effusion, palpitations, pulmonary arterial hypertension | [32, 38, 39] |

| Bosutinib | Edema, pericardial effusion, angina pectoris, pericarditis, QTc prolongation | [32, 38, 40, 41] |

| Ponatinib | Vascular occlusion events, hypertension, peripheral edema, left ventricular dysfunction, HF (including fatalities), pulmonary edema, cardiogenic shock, ischemia, MI, stroke, arrhythmia, QTc prolongation |

[38, 42, 43] |

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for CML treatment

Imatinib:

In 2003, imatinib became the first FDA approved TKI to manage CML [14]. Imatinib function by binding to the BCR-ABL1 kinase domain, located in an inactive conformation in a pocket reserved for the ATP binding site. The phase III IRIS study reported an unprecedented total cytogenetic response rate of approximately 86% in CML-CP. However, due to drug resistance, some patients relapsed. Imatinib was generally well-tolerated, and it has a long-term safety profile. The imatinib associated adverse cardiac effects are depicted in table 1.

The development of point mutations in tyrosine kinase domain, which prevents efficient imatinib binding to the target, was the primary factor in developing imatinib resistance [15]. Till date, more than 100 mutations have been identified, which promotes genomic instability and contributes to imatinib resistance [7, 16–20]. Shortly after the development of imatinib-resistance, second and third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors were designed to treat CML [21–24]. The first well-known imatinib resistance mutation leads to an exchange of threonine at position 315 to isoleucine (T315I). At present, BCR-ABL-T315I remains the most troublesome mutation associated with CML progression [8, 25, 26].

Dasatinib, Nilotinib, and Bosutinib

Second-generation TKIs include nilotinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib. They have a higher affinity for the binding site on the BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase protein. This allows for more effective inhibition of BCR-ABL1 when compared to imatinib. Dasatinib is a potent multikinase inhibitor targeting BCR-ABL1 and is effective in the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia-chromosome-positive (Ph+) CML in all phases of the disease. Nilotinib was approved in 2007 to treat newly diagnosed adults with CML-CP and patients with CML-CP/AP who are resistant to or intolerant of previous therapy. Bosutinib was initially approved by the FDA in 2012 and prescribed for CML patients in any phase, who are resistant or intolerant of prior TKIs. The Second-generation TKIs associated adverse cardiac effects are summarized in table 1. Although dasatinib (Sprycel, BMS-354825), nilotinib (Tasigna, AMN107), and bosutinib (Bosulif, SKI-606) were effective against imatinib-resistant CML, still patients with T315I mutation (gatekeeper mutation) suffered [27, 28].

Ponatinib

Ponatinib emerged from the need of a TKI, which is effective against the T315I mutation of the BCR-ABL1 alongside native BCR-ABL and more commonly seen mutations of BCR-ABL. The T315I mutation of the BCR-ABL1 changes the topology of the ATP binding region [44]. Residue 315 is known as the “gatekeeper” residue due to its location in front of the hydrophobic pocket. When threonine is mutated to isoleucine, the bulkier isoleucine side chain extends into the enzyme active site. The resulting steric clash blocks the entrance of a TKI into the hydrophobic pocket, but still allows access to ATP. Thus, first- and second-generation TKIs fail to inhibit BCR-ABL T315I mutation [44]. The overall structure of Ponatinib is based on the ATP-mimetic structure used in previous iterations of TKIs. The goal in creating ponatinib was to handle the lack of an active-site hydrogen bond and the new steric hindrance caused by the isoleucine side chain [8, 45]. Ponatinib targets the T315I chain by the construction of van der walls interaction using an ethynyl linkage.

Pre-clinical studies with ponatinib

In 2006, initial preclinical studies of ponatinib were done with in vitro biochemical assays. These studies were performed with K562, a BCR-ABL positive human cell line, and Ba/F3, a pro-B mouse cell line [45]. The primary purpose of these assays was to determine the ponatinib ability to inhibit BCR-ABL kinase activity and cell proliferation. The results from these experiments confirmed that ponatinib does inhibit both wild-type and mutant BCR-ABL kinase with IC50 values of 0.37-2.0 nM. A dose of 40 nM has the ability to entirely suppress the development of BCR-ABL resistant mutants [45, 46]. Due to the success of in vitro results, ponatinib efficacy was further tested on mice models [45]. It was found that the 10 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg have the ability to suppress tumor growth, while the 50 mg/kg dose has the ability to reduce mean tumor volume by approximately 96%. The suggested dose of ponatinib is 45 mg once daily, but the label cautions that an optimal dosage has not been identified, and the majority of patients treated with ponatinib have required dose reductions to 30 or 15 mg.

Ponatinib adverse Vascular effects

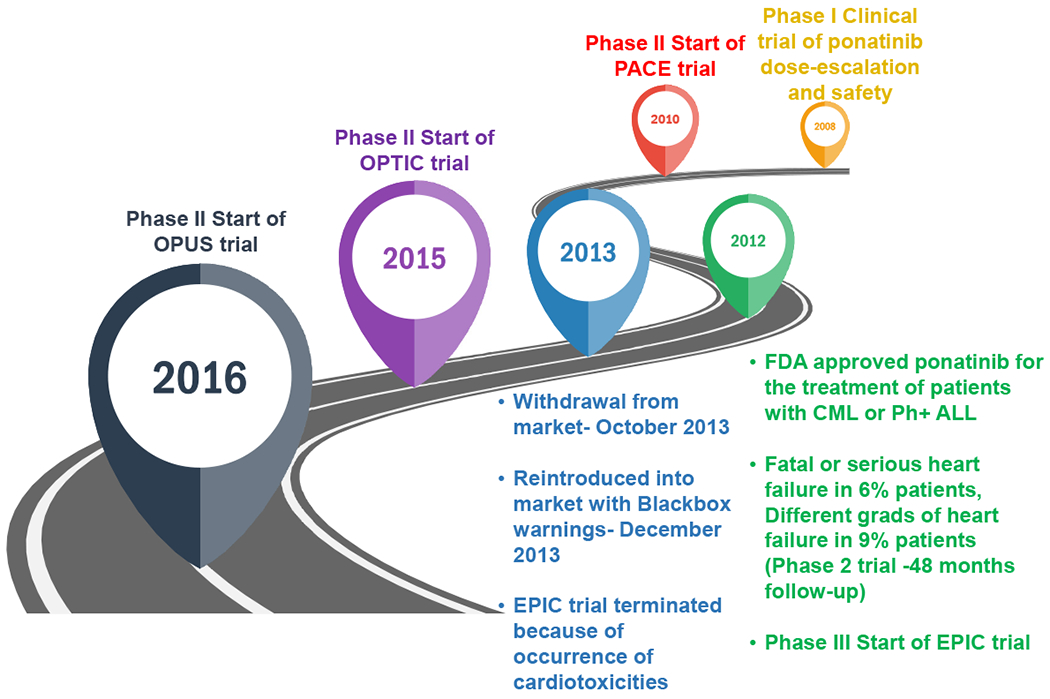

Ponatinib adverse effects on the vascular system and atherosclerotic plaque formation are comparatively more recognized than the direct cardiotoxicity and recently reviewed [47–53], therefore, herein, we will only discuss in brief. In fact, ponatinib’s approval was suspended in October 2013, primarily due to safety concerns arising from the increased incidence of serious vascular occlusive events. However, given that there was no alternative treatment option for CML patients with the T315I mutation, the suspension was short-lived. After a couple of months, ponatinib was reintroduced with added safety measures regarding cardiovascular risk.

The adverse vascular effect of ponatinib was clearly evident in various clinical trials. In the 5-year follow-up of the phase 2 PACE trial with 449 patients, the cumulative incidence of arterial occlusive events (AOEs), including cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular, was 26% [54]. These included cardiac vascular occlusion in 12% of patients (including coronary artery occlusion and myocardial infarction, sometimes preceding or concurrent with heart failure), cerebrovascular occlusion (6%), peripheral arterial occlusive events (8%), and venous thromboembolic events (5%) (Table 1) [55]. Additionally, at least 25% of patients developed hypertension. These severe safety concerns raised by the PACE trial led to the termination of the phase III EPIC trial, which was designed to compare the ponatinib versus imatinib as frontline therapy for newly diagnosed CML patients [56]. In light of the findings from the PACE trial, Ponatinib is no longer a choice of drug for newly diagnosed CML patients. Specifically, it reserved for CML patients carrying T315I mutation or if other TKIs are not responsive. Jain et al. [57] performed a meta-analysis of several clinical trials with CML patients treated with various TKIs and found that ponatinib was associated with the highest incidence of CAEs/AOEs. To identify the recurrence of arterial occlusive events in CML patients treated with 2nd and 3rd generation TKI, Caocci et al. [49] followed a real-life cohort of 57 adult CML patients with a previous history of AOE. Indeed, patients treated with ponatinib showed a 64 % incidence of recurrent AOEs [49]. The same group of investigators demonstrated that AOEs in CML patients treated with ponatinib could be predicted by the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) chart [50]. This study was performed with the real-life cohort of 85 adult CML patients who were treated with ponatinib at 17 Italian centers. Based on sex, age, smoking habits, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol levels, patients were stratified as per the SCORE assessment system. The increased incidence of AOEs in CML patients treated with ponatinib was high to very high SCORE risk. Investigators of this study suggested personalized prevention strategies for CML patients on ponatinib based on CV risk factors [50]. Pouwer et al. [53] reported an increased risk of thrombosis and atherosclerosis in ponatinib treated animals. Pre-treatment of mice with the calcium channel antagonist, diltiazem, prior to ponatinib, reversed the pro-thrombotic phenotype suggesting that the pro-thrombotic effect of ponatinib is partially related to calcium channel activation [58]. Indeed, ponatinib-treated CML patients had increased ex vivo thrombus formation and a pro-inflammatory phenotype compared with healthy controls [53]. Taken together, the accumulating data strongly indicate that ponatinib is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular adverse events. To further evaluate the efficacy and safety of ponatinib, a multicenter, randomized phase 2 trial (OPTIC Study) with three dosages of ponatinib (45 mg, 30 mg, and 15 mg) are currently ongoing, and results are expected later this year (2020). The outcome of this study will be critical in understanding if ponatinib mediated vascular effects are dose-dependent, and dosage reduction can lower the rate of adverse vascular effects with maintained efficacy (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02467270).

The precise mechanism of ponatinib induced adverse vascular effects are not clear. However, the broad kinase inhibition profile of ponatinib is believed to contribute to the increased incidence of adverse vascular events. Indeed, ponatinib leads to endothelial dysfunction through non-specific targeting of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors [59]. Furthermore, ponatinib leading to an increased risk of vascular occlusive events by promoting the expression of proatherogenic surface adhesion receptors [60]. Ponatinib also has direct prothrombotic effects by accelerating platelet activation and adhesion [51]. Recently, Madonna et al. [61] employed human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) to demonstrate that ponatinib-induced vascular toxicity is primarily mediated through the Notch-1 Signaling Pathway. The findings from this study revealed that ponatinib inhibits endothelial survival, reduces angiogenesis, and induces endothelial senescence and apoptosis via the Notch-1 pathway. Indeed, selective blockade of Notch-1 prevented ponatinib-induced vascular toxicity [61]. Thus, it appears that ponatinib mediated adverse vascular effects are primarily due to the off-target impacts on platelet activation and endothelial cells function. In light of all these strong clinical and experimental evidence, FDA has added a black-box warning for the safe use of ponatinib for arterial occlusion and venous thromboembolic events with the other important side effects such as heart failure. Therefore, patients on ponatinib must be informed and closely monitored for vascular AEs including, high blood pressure, thromboembolic events, evidence of arterial occlusion, and decline in cardiac function (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1:

Roadmap of ponatinib development and clinical trials.

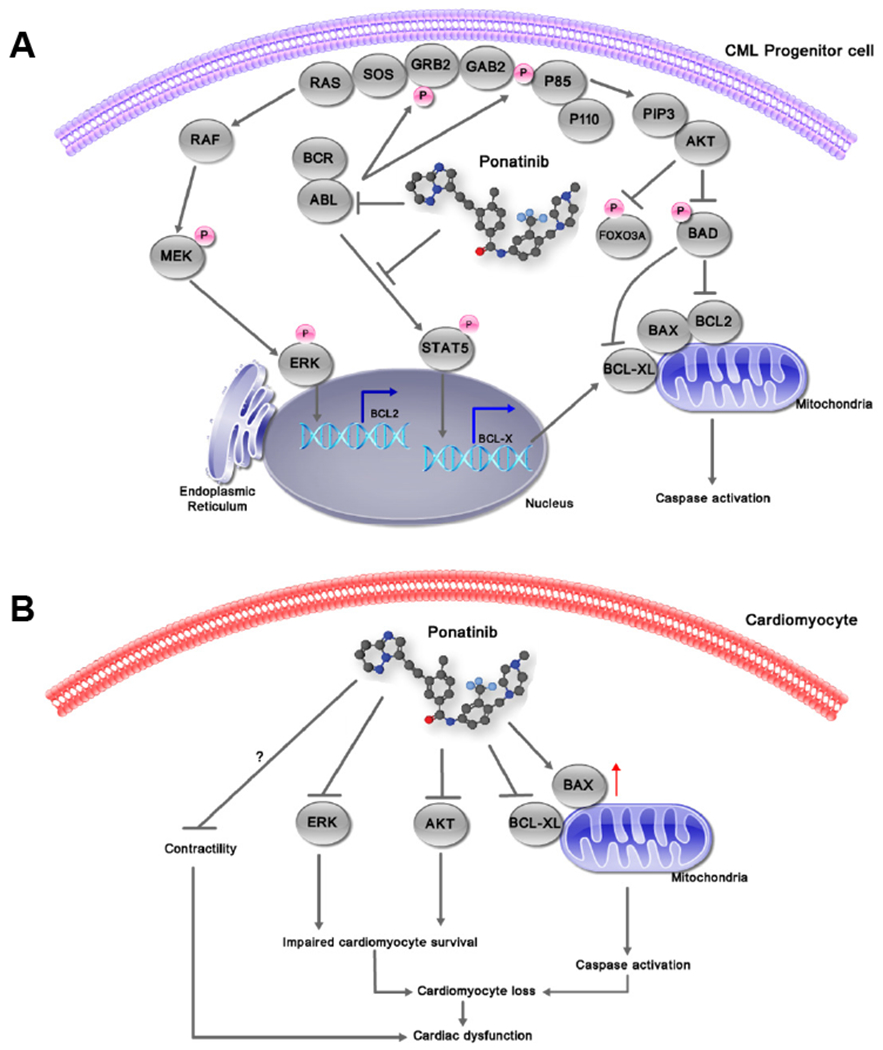

Preclinical studies of ponatinib cardiotoxicity

Pre-clinical screening with animal models has not been able to reliably determine which KIs will have associated cardiotoxicity. This has led to some unfortunate “surprises” once these agents have gotten into the real-world patient population. In the early clinical trials with ponatinib, very few cases of cardiotoxicity were reported [55, 62]. However, additional follow-up from various ponatinib trials has exposed a high occurrence of serious adverse cardiac events. Importantly, typical pre-clinical toxicology studies done with this agent failed to detect significant problems, highlighting the inadequacy of current approaches. We need accurate, rapidly translatable, and high throughput strategies to predict cardiotoxicity and to prevent any more of these otherwise inevitable surprises. Ponatinib is an example shown an unexpected broad spectrum of cardiotoxic complications. This toxicity is primarily due to lack of kinase selectivity, and target pathways common to both cancer and cardiac cells (Figure 2). Indeed, ponatinib is a multi-targeted kinase inhibitor that suppresses more than 60 kinases, including PDGFR, c-KIT, RET, VEGFR, and FGFR activities [45, 46, 63–84]. However, the anticancer mechanisms and the cardiotoxic mechanisms seem to be quite distinct, leading us to hope that studies to reduce the cardiotoxic effects will not diminish the anticancer effect of ponatinib. We have summarized the potential targets of ponatinib in table 2 with their implications on cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2:

Signaling pathway inhibition by ponatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia and cardiomyocytes. (A) Ponatinib inhibits all BCR–ABL-dependent phosphorylation and signaling events, leading to the reversal of pro-survival effects and activation of apoptosis in leukemic cells. (B) In cardiomyocytes, ponatinib rapidly inhibits prosurvival signaling pathways leading to cardiomyocytes apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction. BAX, BCL2 associated X protein; BAD, BCL2-antagonist of cell death; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FOXO3A, forkhead box O3A; GAB2, GRB2-associated binding protein 1; GRB2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; MEK, mitogen-activated ERK kinase; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol trisphosphate; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SOS, son of sevenless; STAT5, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5.

Table 2:

Ponatinib targets and their implication on cardiomyocytes

| S.No. | Ponatinib Target | Disease | Studied cell lines | Implication on cardiomyocytes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | FGFR1 | Myeloproliferative syndrome | Transformed murine BaF3 cells, human KG1 cells, small cell lymphocytic lymphoma cells | Altered cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation | [76, 82] |

| Lung cancer | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines | [46, 77] | |||

| Neuroblastoma | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

[66, 90] | |||

| Small cell carcinoma of the ovary |

BIN67 and SCCOHT-1 cells | [64] | |||

| Malignant rhabdoid tumors | MRT cell lines (A204 and G402) | [70] | |||

| 2. | FGFR2 | Endometrial cancer cells | EC cell lines MFE-296, AN3CA, MFE-280 | Altered cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation, less cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis upon inhibition |

[71, 80] |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | GIST-derived cell lines | [74] | |||

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-231 | [46] | |||

| Neuroblastoma (NB) | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

[66, 90] | |||

| 3. | FGFR3 | Bladder cancer | Bladder cancer cells | Altered cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation | [46] |

| Neuroblastoma (NB) | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

[66, 90] | |||

| 4. | FGFR4 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | HCC cell lines MHCC97L, MHCC97H, HepG2 and SMMC7721 | Less cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis upon inhibition | [68] |

| Neuroblastoma (NB) | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

[66, 90] | |||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | RMS cell lines (RH28, JR, RH18, RD, CTR, BIRCH, TTC-516, TTC-442, RH30, RH4, RH5, RH41, and RH36) | [79] | |||

| 5. | FLT3 | Acute myeloid leukemia | MV4-11, Ba/F3-ITD-676, Ba/F3-ITD-691, and Ba/F3-ITD-697 | Cardiomyocyte death | [83, 84] |

| Neuroblastoma | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

[66, 90] | |||

| 6. | PDGFRα | Small cell carcinoma of the ovary | BIN67 and SCCOHT-1 cells | Less cardiac fibrosis upon inhibition | [64] |

| Malignant rhabdoid tumors | MRT cell lines (A204 and G402) | [70] | |||

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | Merlin-deficient HSC line | [65] | |||

| Chronic eosinophilic leukemia | EOL-1, BaF3 cells | [72, 73] | |||

| 7. | RET | Thyroid cancer | TT thyroid cancer cell lines | Not expressed in cardiomyocytes | [81] |

| Lung cancer | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines | [75] | |||

| Medullary thyroid cancer | Human TT, MZ-CRC-1 and TPC-1 thyroid carcinoma cells | [78] | |||

| 8. | c-KIT | Neuroblastoma | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

Not expressed in adult cardiomyocytes |

[66, 90] |

| Liposarcoma | human liposarcoma cell lines (SW872, LP6, SA-4, LiSa-2, FU-DDLS-1, LPS141, GOT-3, MLS-402, T778 and T1000 | [67] | |||

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | GIST-derived cell lines | [74] | |||

| 9. | PDGFR | Neuroblastoma | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

Altered contractility | [66, 90] |

| 10. | PDGFRβ | Infantile myofibromatosis | Mutant transfected MCF7 and HEK-293T cell lines | Altered contractility | [69] |

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | Merlin-deficient HSC line | [65] | |||

| 11. | c-SRC | Chronic myeloid leukemia | BaF3 cell lines | Altered contractility | [45] |

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | Merlin-deficient HSC line | [65] | |||

| 12. | VEGFR1 | Neuroblastoma | NB cell lines (CHP-134, CHP-212, NGP, LAN-5, SH-EP, SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE and SK-N-SH) |

Altered contractility | [66, 90] |

| 13. | VEGFR2 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | BaF3 cell lines | Altered contractility | [45] |

| Medullary thyroid cancer | Human TT, MZ-CRC-1 and TPC-1 thyroid carcinoma cells | [81] | |||

| 14. | c-Jun | Breast cancer lung metastasis | MDA-MB-231 | Cardiomyocyte apoptosis | [63] |

Unbiased screening experiments from multiple labs have identified ponatinib as most cardiotoxic FDA approved TKI [12, 13, 85]. Toaccurately predict the cardiotoxic potential of ponatinib, Talbert et al. [86] used human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM). They showed that ponatinib rapidly inhibits prosurvival signaling pathways and induces cardiac toxicity. In an elegant study, Sharma et al. [13] have used patient-specific hiPSC-CMs and evaluated the cardiotoxicities of 21 FDA-approved TKIs. Indeed, among them, ponatinib was the most cardiotoxic TKI. Importantly, due to the well-known limitations of the cell-based models, these studies were unable to provide any extra-cardiac or organ-level effects. More recently, Hasselt et al. [85] developed an approach to predict cardiotoxicity of TKIs using clinically-weighted transcriptomic signatures. They analyzed transcriptomic profiles of TKI treated human primary cardiomyocyte cell lines with clinical data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. This analysis derived clinically weighted transcriptomic signatures that may allow ranking prospective KIs for their relative risk of cardiotoxicity. We used a zebrafish transgenic BNP reporter line [12, 87] that expresses luciferase under control of the nppb promoter (nppb: F-Luciferase) to screen cardiotoxic potential of TKIs. Indeed, BNP is a well-established clinical marker of heart failure [88, 89]. Consistent with others, our in vivo screening predicted ponatinib as most cardiotoxic CML-TKIs. This was the first report [12] to demonstrate the ponatinib cardiotoxicity and associated molecular mechanism by employing an in vivo model system. This study also encourages a potential translational use of the zebrafish model for the prediction of cardiotoxicity of anti-cancer drugs.

Mechanism of ponatinib-induced cardiotoxicity

Although we are still far from a clear understanding of TKIs-induced cardiotoxicity, progress has been made to unravel the basic underlying mechanisms of TKIs mediated cardiotoxicity. In an excellent study, Sharma et al. [13] have shown that ponatinib treated patient-specific hiPSC-CMs depicts a compensatory upregulation in cardioprotective insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling. This suggested that ponatinib exerts its cardiotoxicity by inhibition of growth signaling pathways. In the same line, Talbert et al. [86] also showed ponatinib induced perturbation of prosurvival signaling pathways. In our recent study [12], to mimic the real clinical scenario, ponatinib concentration was matched to serum blood concentration in treated patients. We demonstrated that ponatinib downregulates the phosphorylation of AKT and ERK. Indeed, these pathways are known to regulate cardiomyocyte survival and critical to cardiac homeostasis. Inhibition of AKT signaling has been shown to exacerbate the ischemia-reperfusion injury, pressure overload, and oxidative stress-mediated cardiac myocyte death by promoting apoptosis. Similarly, the ERK pathway is critical to myocyte survival, proliferation, and differentiation. For proof of concept, we synergistically augmented AKT and ERK signaling pathways with Neuregulin-1β. Indeed, neuregulin-1β treatment restored phosphorylation of AKT and ERK and cardiomyocyte viability. Taken together, ponatinib cardiotoxicity is primarily driven by an off-target effect on cardiomyocyte survival pathways. With that said, we believe that the true breadth of the cardiotoxic mechanism associated with TKIs including ponatinib requires identification of potential kinome signatures in conjunction with human adverse events databases. This will facilitate the identification of pathway-specific cardiac insult, which will allow us to mitigate the cardiotoxicity of TKIs during their preclinical development.

A cardio-oncologist view: implications for the patients care.

As the ponatinib associated cardiovascular adverse effects are getting increasingly recognized, several guidelines/recommendations/expert opinions regarding the identification, prevention, and management of cardiovascular adverse events in CML patients on ponatinib are published [48, 52, 91–94]. We refer the readers to these guidelines for detailed description; herein, we are only presenting a brief discussion with a particular emphasis on cardiotoxicity.

Before starting the ponatinib treatment, a series of baseline examinations should be performed to establish the patient’s cardiovascular risk score. This should include the assessment of plasma levels of BNP and troponin, as well as detailed ECG and echocardiography [48, 93, 95]. Indeed, due to the low-cost, non-invasive nature, and repeatability, echocardiography is the preferred imaging tool for cardio-oncology patients. A detailed ECG can help to discover the signs of cardiac conduction abnormalities (QTc prolongation, atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia, etc.) [52, 93]. Initial exams should also include parameters for vascular disease risk assessment, including an ankle-brachial index (ABI), detection of atherosclerotic plaques, and intima-media thickness (IMT) by an exploration of supra-aortic and limb vessels [48, 91]). As preexisting cardiovascular comorbidities are crucial to later cardiovascular events, these baseline CVD risk assessment is vital [52, 93]. Once the basal cardiovascular risk category is established, patients should be scheduled for a long-term cardiovascular follow-up accordingly [52]. Patients with preexisting comorbidities/high-risk patients will undoubtedly benefit from the more frequent followup/monitoring. Moreover, for this high-risk patient category, it’s suggested to constitute a clinical care team from the beginning. This should include the oncologists, cardiologists, and hematologists [48, 91, 94].

Patients on ponatinib therapy must be regularly monitored for cardiac function and conduction abnormalities, hypertension, vascular AEs. It is believed that ponatinib mediated CVD adverse effects are dose-dependent; therefore, a prompt dose adjustment and close follow up is critical to ensure a balance between efficacy and safety [93]. As discussed above, the approved dose for ponatinib is 45 mg once a day. It is recommended that this dose should only be prescribed until a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) or major molecular response (MMR) is achieved. After that, a dose reduction should be considered as per patients’ CVD monitoring data [48, 52, 91].

Furthermore, for patients with high CVD risk category, it’s advised to adjust the starting dose to 30–15 mg/day, and consider to increase if the anti-oncogenic response is not satisfactory. In the latter case, CVD risk should be closely monitored and carefully managed [48, 91]. Indeed, the FDA recommends stopping the ponatinib treatment if there are serious ischemic events like Ml or stroke [92]. Additionally, it is suggested not to restart the treatment unless there are no other treatment options available, and the potential benefit surpasses the risk of subsequent ischemia. Of note, the cardiotoxicity is often reversible with drug interruption. For the low-risk category, treatment should be continued on the selected dose with regular monitoring of CVD risk every three months [92, 95]. More frequent monitoring (every 2-3 weeks) should be considered if the patient is developing any sign of cardiotoxicity, e.g., a decline in ejection fraction. If the patient develops symptoms of overt heart failure, it should be treated with standardized therapy as per clinical indication [48, 91]. If the symptoms of congestive heart failure further worsen, the discontinuation of treatment should be considered. Thus, a baseline risk assessment, careful follow-up, dose adjustment, and a multidisciplinary collaborative effort to patient care are essential to ensure an optimal balance of risk and benefit of ponatinib treatment.

Conclusion and future perspectives

The emergence of cardiotoxicity is one of the primary limitations of anticancer therapeutics and has a strong effect on patient quality of life and survival. To diminish the risk of cardiac diseases, cardiologists should be aware of the potential cardiotoxic effects of anticancer drugs. Ponatinib is the only TKI that works effectively against T315I mutation +tive CML patients. Ponatinib granted accelerated approval because of its clinical efficacy. In phase I trial of ponatinib, responses were observed at the lowest dose levels. It was found that daily doses of 15–45 mg would achieve serum drug concentrations predicted to suppress the T315I mutations in preclinical studies. Consequently, the approved daily dose of 45 mg may not have been ideal in terms of efficacy and safety, because further studies and trials showed a clear association between dose intensity and appearance of cardiovascular adverse events. Although clinical trials provide a good baseline reference point for the approval of a cancer drug. But, the real patient population is multifactorial, and the cumulative effect of various co-morbidities or other complications may give rise to synergistic cardiotoxic effects that are underreported in preclinical studies. While there is a growing body of evidence and an increased understanding of the pathogenesis of ponatinib-induced cardiotoxicity, the process of determining how best to manage and prevent major cardiotoxicities remains a significant challenge. Oncologists, in collaboration with multidisciplinary teams, have the delicate responsibility of identifying the proper treatment combination that will maximize tumor response while minimizing adverse outcomes. More intense scrutiny of cardiac complications in preclinical studies are warranted for upcoming TKIs before FDA approval. Additionally, determination of cardiotoxic mechanisms necessitates the identification of the specific target, inhibition of which is responsible for cardiotoxicity. This identification of the critical target accomplishes two things. First, once a tyrosine kinase is recognized as playing a vital function in the heart, all subsequent kinase inhibitors that target that kinase will be suspect. Thus, one should be able to predict cardiotoxic agents, prior to their release. Second, the identification of targets facilitating cardiotoxicity can help guide future drug design by avoiding “bystander” targets. Therefore, approaches could be developed that would block drug-induced activation of the pathway in the heart that is responsible for cardiotoxicity but would leave tumor cell killing intact. The conjunction of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System and clinically-weighted transcriptomic signatures will provide significantly deeper insight to target genes in relation to cardiotoxic mechanisms of TKIs. This will enable better precautions and monitoring of adverse effects associated with these agents during drug development.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

New, growing, but well-established discipline “cardio-oncology” focuses on the monitoring, prevention, and treatment of cardiovascular complications associated with cancer therapeutics.

Radiation and chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity are well established. However, the cardiotoxicity associated with targeted therapies (kinase inhibitors (KIs)) is less recognized.

Multiple labs have identified ponatinib as most cardiotoxic KI among the entire FDA approved KI family.

Of note, Ponatinib is the only treatment option for CML patients with T315I mutation.

This review focusses on the cardiovascular risks and mechanism/s associated with CML KIs with a particular emphasis on ponatinib cardiotoxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by research grants to HL from the NHLBI (R01HL133290, R01HL119234). PU is supported by American Heart Fellowship (AHA) postdoctoral Fellowship (19POST34460025).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have no conflicting interests to disclose in relation to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma A, Wu JC, Wu SM. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for cardiovascular disease modeling and drug screening. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2013;4:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society AC. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shtivelman E, Lifshitz B, Gale RP, Canaani E. Fused transcript of abl and bcr genes in chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nature. 1985;315:550–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Neriah Y, Daley GQ, Mes-Masson AM, Witte ON, Baltimore D. The chronic myelogenous leukemia-specific P210 protein is the product of the bcr/abl hybrid gene. Science. 1986;233:212–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, Hsu N, Paquette R, Rao PN, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293:876–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Hare T, Eide CA, Deininger MW. Bcr-Abl kinase domain mutations, drug resistance, and the road to a cure for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:2242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Adrian FJ, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Li AG, lacob RE, et al. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature. 2010;463:501–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hantschel O, Grebien F, Superti-Furga G. The growing arsenal of ATP-competitive and allosteric inhibitors of BCR-ABL. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4890–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, Gathmann I, Kantarjian H, Gattermann N, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2408–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh AP, Glennon MS, Umbarkar P, Gupte M, Galindo CL, Zhang Q, et al. Ponatinib-induced cardiotoxicity: delineating the signalling mechanisms and potential rescue strategies. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115:966–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma A, Burridge PW, McKeithan WL, Serrano R, Shukla P, Sayed N, et al. High-throughput screening of tyrosine kinase inhibitor cardiotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian HM, Cortes JE. Mechanisms of primary and secondary resistance to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Control. 2009;16:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerkela R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, lliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, et al. Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate. Nature medicine. 2006;12:908–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochhaus A, O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Druker BJ, Branford S, Foroni L, et al. Six-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1054–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castagnetti F, Gugliotta G, Breccia M, Stagno F, lurlo A, Albano F, et al. Long-term outcome of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated frontline with imatinib. Leukemia. 2015;29:1823–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soverini S, Hochhaus A, Nicolini FE, Gruber F, Lange T, Saglio G, et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2011;118:1208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoklosa T, Poplawski T, Koptyra M, Nieborowska-Skorska M, Basak G, Slupianek A, et al. BCR/ABL inhibits mismatch repair to protect from apoptosis and induce point mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2576–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamath AV, Wang J, Lee FY, Marathe PH. Preclinical pharmacokinetics and in vitro metabolism of dasatinib (BMS-354825): a potent oral multi-targeted kinase inhibitor against SRC and BCR-ABL. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller MC, Cortes JE, Kim DW, Druker BJ, Erben P, Pasquini R, et al. Dasatinib treatment of chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: analysis of responses according to preexisting BCR-ABL mutations. Blood. 2009;114:4944–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert GK, Duhme-Klair AK, Morgan T, Ramjee MK. The background, discovery and clinical development of BCR-ABL inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18:992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinwald M, Schleyer E, Kiewe P, Blau IW, Burmeister T, Pursche S, et al. Efficacy and pharmacologic data of second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib in BCR-ABL-positive leukemia patients with central nervous system relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:637059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolini FE, Corm S, Le QH, Sorel N, Hayette S, Bories D, et al. Mutation status and clinical outcome of 89 imatinib mesylate-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia patients: a retrospective analysis from the French intergroup of CML (Fi(phi)-LMC GROUP). Leukemia. 2006;20:1061–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soverini S, Colarossi S, Gnani A, Rosti G, Castagnetti F, Poerio A, et al. Contribution of ABL kinase domain mutations to imatinib resistance in different subsets of Philadelphia-positive patients: by the GIMEMA Working Party on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah NP, Tran C, Lee FY, Chen P, Norris D, Sawyers CL. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science. 2004;305:399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, Bruggen J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Ray A, et al. Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:129–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trent JC, Patel SS, Zhang J, Araujo DM, Plana JC, Lenihan DJ, et al. Rare incidence of congestive heart failure in gastrointestinal stromal tumor and other sarcoma patients receiving imatinib mesylate. Cancer. 2010;116:184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atallah E, Durand JB, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Congestive heart failure is a rare event in patients receiving imatinib therapy. Blood. 2007;110:1233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.FDA US. GLEEVEC (imatinib mesylate) tablets for oral use 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Z, Cang S, Yang T, Liu D. Cardiotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia therapy. Hematology Reviews. 2009;1:e4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tefferi A, Letendre L. Nilotinib treatment-associated peripheral artery disease and sudden death: yet another reason to stick to imatinib as front-line therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:610–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steve-Dumont M, Baldin B, Legros L, Thyss A, Re D, Rocher F, et al. Are nilotinib-associated vascular adverse events an under-estimated problem? Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2015;29:204–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Nilotinib-associated vascular events. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12:337–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aichberger KJ, Herndlhofer S, Schernthaner GH, Schillinger M, Mitterbauer-Hohendanner G, Sillaber C, et al. Progressive peripheral arterial occlusive disease and other vascular events during nilotinib therapy in CML. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FDA US. TASIGNA® (nilotinib) capsules, for oral use. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moslehi JJ, Deininger M. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Associated Cardiovascular Toxicity in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.FDA US. SPRYCEL (dasatinib) tablets, for oral use. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbas R, Chalon S, Leister C, El Gaaloul M, Sonnichsen D. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and safety of bosutinib in patients with chronic hepatic impairment and matched healthy subjects. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.FDA US. BOSULIF® (bosutinib) tablets, for oral use 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonnichsen D, Dorer DJ, Cortes J, Talpaz M, Deininger MW, Shah NP, et al. Analysis of the potential effect of ponatinib on the QTc interval in patients with refractory hematological malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:1599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.FDA US. ICLUSIG® (ponatinib) tablets for oral use 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller GD, Bruno BJ, Lim CS. Resistant mutations in CML and Ph(+)ALL - role of ponatinib. Biologies. 2014;8:243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:401–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gozgit JM, Wong MJ, Moran L, Wardwell S, Mohemmad QK, Narasimhan Nl, et al. Ponatinib (AP24534), a multitargeted pan-FGFR inhibitor with activity in multiple FGFR-amplified or mutated cancer models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:690–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan O, Talati C, Isenalumhe L, Shams S, Nodzon L, Fradley M, et al. Side-effects profile and outcomes of ponatinib in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020;4:530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casavecchia G, Galderisi M, Novo G, Gravina M, Santoro C, Agricola E, et al. Early diagnosis, clinical management, and follow-up of cardiovascular events with ponatinib. Heart Fail Rev. 2020;25:447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caocci G, Mulas O, Bonifacio M, Abruzzese E, Galimberti S, Orlandi EM, et al. Recurrent arterial occlusive events in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with second- and third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors and role of secondary prevention. Int J Cardiol. 2019;288:124–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caocci G, Mulas O, Abruzzese E, Luciano L, lurlo A, Attolico I, et al. Arterial occlusive events in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with ponatinib in the real-life practice are predicted by the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) chart. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37:296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latifi Y, Moccetti F, Wu M, Xie A, Packwood W, Qi Y, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy as a cause of cardiovascular toxicity from the BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor ponatinib. Blood. 2019;133:1597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santoro M, Accurso V, Mancuso S, Contrino AD, Sardo M, Novo G, et al. Management of Ponatinib in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia with Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Chemotherapy. 2019;64:205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pouwer MG, Pieterman EJ, Verschuren L, Caspers MPM, Kluft C, Garcia RA, et al. The BCR-ABL1 Inhibitors Imatinib and Ponatinib Decrease Plasma Cholesterol and Atherosclerosis, and Nilotinib and Ponatinib Activate Coagulation in a Translational Mouse Model. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, le Coutre PD, Paquette R, Chuah C, et al. Ponatinib efficacy and safety in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia: final 5-year results of the phase 2 PACE trial. Blood. 2018;132:393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-lbarz J, le Coutre P, Paquette R, Chuah C, et al. A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1783–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lipton JH, Chuah C, Guerci-Bresler A, Rosti G, Simpson D, Assouline S, et al. Ponatinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukaemia: an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:612–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jain P, Kantarjian H, Boddu PC, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Verstovsek S, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Analysis of cardiovascular and arteriothrombotic adverse events in chronic-phase CML patients after frontline TKIs. Blood Adv. 2019;3:851–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamadi A, Grigg AP, Dobie G, Burbury KL, Schwarer AP, Kwa FA, et al. Ponatinib Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Induces a Thromboinflammatory Response. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119:1112–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gover-Proaktor A, Granot G, Shapira S, Raz O, Pasvolsky O, Nagler A, et al. Ponatinib reduces viability, migration, and functionality of human endothelial cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1455–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valent P, Hadzijusufovic E, Hoermann G, Fureder W, Schernthaner GH, Sperr WR, et al. Risk factors and mechanisms contributing to TKI-induced vascular events in patients with CML. Leukemia research. 2017;59:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Madonna R, Pieragostino D, Cufaro MC, Doria V, Del Boccio P, Deidda M, et al. Ponatinib Induces Vascular Toxicity through the Notch-1 Signaling Pathway. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Bixby D, Mauro MJ, Flinn I, et al. Ponatinib in refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2075–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shao W, Li S, Li L, Lin K, Liu X, Wang H, et al. Chemical genomics reveals inhibition of breast cancer lung metastasis by Ponatinib via c-Jun. Protein Cell. 2019;10:161–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lang JD, Hendricks WPD, Orlando KA, Yin H, Kiefer J, Ramos P, et al. Ponatinib Shows Potent Antitumor Activity in Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary Hypercalcemic Type (SCCOHT) through Multikinase Inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1932–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petrilli AM, Garcia J, Bott M, Klingeman Plati S, Dinh CT, Bracho OR, et al. Ponatinib promotes a G1 cell-cycle arrest of merlin/NF2-deficient human schwann cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31666–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H, Wang Y, Chen Z, Lu J, Pan J, Yu Y, et al. Novel multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitor ponatinib inhibits bFGF-activated signaling in neuroblastoma cells and suppresses neuroblastoma growth in vivo. Oncotarget. 2017;8:5874–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanojia D, Garg M, Martinez J, M TA, Luty SB, Doan NB, et al. Kinase profiling of liposarcomas using RNAi and drug screening assays identified druggable targets. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 68.Gao L, Wang X, Tang Y, Huang S, Hu CA, Teng Y. FGF19/FGFR4 signaling contributes to the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arts FA, Sciot R, Brichard B, Renard M, de Rocca Serra A, Dachy G, et al. PDGFRB gain-of-function mutations in sporadic infantile myofibromatosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:1801–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wong JP, Todd JR, Finetti MA, McCarthy F, Broncel M, Vyse S, et al. Dual Targeting of PDGFRalpha and FGFR1 Displays Synergistic Efficacy in Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim DH, Kwak Y, Kim ND, Sim T. Antitumor effects and molecular mechanisms of ponatinib on endometrial cancer cells harboring activating FGFR2 mutations. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17:65–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sadovnik I, Lierman E, Peter B, Flerrmann H, Suppan V, Stefanzl G, et al. Identification of Ponatinib as a potent inhibitor of growth, migration, and activation of neoplastic eosinophils carrying FIP1L1-PDGFRA. Exp Hematol. 2014;42:282–93 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jin Y, Ding K, Li H, Xue M, Shi X, Wang C, et al. Ponatinib efficiently kills imatinib-resistant chronic eosinophilic leukemia cells harboring gatekeeper mutant T674I FIPIL1-PDGFRalpha: roles of Mcl-1 and beta-catenin. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garner AP, Gozgit JM, Anjum R, Vodala S, Schrock A, Zhou T, et al. Ponatinib inhibits polyclonal drug-resistant KIT oncoproteins and shows therapeutic potential in heavily pretreated gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5745–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dabir S, Babakoohi S, Kluge A, Morrow JJ, Kresak A, Yang M, et al. RET mutation and expression in small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ren M, Qin H, Ren R, Cowell JK. Ponatinib suppresses the development of myeloid and lymphoid malignancies associated with FGFR1 abnormalities. Leukemia. 2013;27:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ren M, Hong M, Liu G, Wang H, Patel V, Biddinger P, et al. Novel FGFR inhibitor ponatinib suppresses the growth of non-small cell lung cancer cells overexpressing FGFR1. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:2181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mologni L, Redaelli S, Morandi A, Plaza-Menacho I, Gambacorti-Passerini C. Ponatinib is a potent inhibitor of wild-type and drug-resistant gatekeeper mutant RET kinase. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;377:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li SQ, Cheuk AT, Shern JF, Song YK, Hurd L, Liao H, et al. Targeting wild-type and mutationally activated FGFR4 in rhabdomyosarcoma with the inhibitor ponatinib (AP24534). PLoS One. 2013;8:e76551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gozgit JM, Squillace RM, Wongchenko MJ, Miller D, Wardwell S, Mohemmad Q, et al. Combined targeting of FGFR2 and mTOR by ponatinib and ridaforolimus results in synergistic antitumor activity in FGFR2 mutant endometrial cancer models. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:1315–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Falco V, Buonocore P, Muthu M, Torregrossa L, Basolo F, Billaud M, et al. Ponatinib (AP24534) is a novel potent inhibitor of oncogenic RET mutants associated with thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E811–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chase A, Bryant C, Score J, Cross NC. Ponatinib as targeted therapy for FGFR1 fusions associated with the 8p11 myeloproliferative syndrome. Haematologica. 2013;98:103–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zirm E, Spies-Weisshart B, Heidel F, Schnetzke U, Bohmer FD, Hochhaus A, et al. Ponatinib may overcome resistance of FLT3-ITD harbouring additional point mutations, notably the previously refractory F691I mutation. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gozgit JM, Wong MJ, Wardwell S, Tyner JW, Loriaux MM, Mohemmad QK, et al. Potent activity of ponatinib (AP24534) in models of FLT3-driven acute myeloid leukemia and other hematologic malignancies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1028–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Hasselt JGC, Hansen J, Xiong Y, Shim J, Pickard A, Jayaraman G, et al. Clinically-weighted transcriptomic signatures for protein kinase inhibitor associated cardiotoxicity. bioRxiv. 2016:075754. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Talbert DR, Doherty KR, Trusk PB, Moran DM, Shell SA, Bacus S. A multi-parameter in vitro screen in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes identifies ponatinib-induced structural and functional cardiac toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2015;143:147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Becker JR, Robinson TY, Sachidanandan C, Kelly AE, Coy S, Peterson RT, et al. In vivo natriuretic peptide reporter assay identifies chemical modifiers of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pufulete M, Maishman R, Dabner L, Higgins JPT, Rogers CA, Dayer M, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide-guided therapy for heart failure (HF): a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data (IPD) and aggregate data. Syst Rev. 2018;7:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nishikimi T, Okamoto H, Nakamura M, Ogawa N, Horii K, Nagata K, et al. Direct immunochemiluminescent assay for proBNP and total BNP in human plasma proBNP and total BNP levels in normal and heart failure. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whittle SB, Patel K, Zhang L, Woodfield SE, Du M, Smith V, et al. The novel kinase inhibitor ponatinib is an effective anti-angiogenic agent against neuroblastoma. Invest New Drugs. 2016;34:685–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saussele S, Haverkamp W, Lang F, Koschmieder S, Kiani A, Jentsch-Ullrich K, et al. Ponatinib in the Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Leukemia: Recommendations of a German Expert Consensus Panel with Focus on Cardiovascular Management. Acta Haematol. 2019:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Molica M, Scalzulli E, Colafigli G, Foa R, Breccia M. Insights into the optimal use of ponatinib in patients with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2019; 10:2040620719826444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Breccia M, Pregno P, Spallarossa P, Arboscello E, Ciceri F, Giorgi M, et al. Identification, prevention and management of cardiovascular risk in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients candidate to ponatinib: an expert opinion. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:549–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Steegmann JL, Baccarani M, Breccia M, Casado LF, Garcia-Gutierrez V, Hochhaus A, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management and avoidance of adverse events of treatment in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:1648–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Munoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2768–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.