Abstract

Close follow-up is mandatory in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, rheumatological care was rapidly reorganized during the first peak from March 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020, and all patients with RA, PsA, and AS being treated with a subcutaneous biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug or oral targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug were followed remotely. A retrospective database analysis of these 431 patients before and after this period is presented herein. A rheumatologist directly contacted all patients by telephone. Patients could also enter data on patient-reported outcomes remotely using the digital platform iAR Plus. General health (GH) and visual analog scale (VAS) pain were the main outcomes along with FACIT and disease-specific questionnaires (RADAI, ROAD, PROCLARA for RA, and BASDAI, BASGI, BASFI for AS). In all, 449 visits were postponed (69.9% of all scheduled visits); telephone evaluation was deemed inadequate in 193 instances, and patients underwent a standard outpatient visit. Comparing patients on telemedicine to those who underwent hospital visits, we found no statistically significant differences in GH (35.3 vs 39.3; p = 0.24), VAS (33.3 vs 37.1; p = 0.29), or other specific outcome measures in patients with RA, PsA, or AS. These results show that telemedicine has undoubted benefits, and in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that many patients with these diseases may prefer it.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00296-021-04863-x.

Keywords: Telemedicine, COVID-19, Inflammatory arthritis, Patient-reported outcomes, Spondyloarthropathies, Rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

The ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has dramatically changed clinical practice worldwide in virtually all medical fields, and rheumatology is no exception [1]. In February 2020, northern Italy was one of the first regions involved in the spread of COVID-19, and placed unprecedented stress on healthcare systems [2, 3]. The subsequent lockdown led to severe travel restrictions, and many hospitals were dedicated almost entirely to treatment of patients with COVID-19. The restructuring of hospitals also dramatically affected outpatient visits, leading to difficulty in providing the routine care to which both patients and clinicians were accustomed. Patients with spondyloarthropathies and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are frequently administered immunomodulators to control their disease, and close follow-up is mandatory to tailor therapy and detect disease flares. In fact, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends that monitoring should be carried out every 1–3 months in patients with RA and active disease [4]. The need for frequent monitoring thus leads to potential compromises in adequate, routine care of rheumatology patients on immunomodulating therapy in emergency epidemiological situations.

To meet these challenges, rheumatological care was rapidly reorganized, including suspension of non-urgent visits and increased use of telemedicine as reported by several groups worldwide [5–7]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telemedicine had already been transforming healthcare, and the transformation has suddenly been accelerated given the stress placed on care systems globally [8, 9]. Telemedicine is broadly considered as the diagnosis and treatment of patients remotely using digital telecommunications technology [10–12]. In the COVID-19 setting, telemedicine has been reported to conserve healthcare resources, with savings in terms of personal protective equipment, while maintaining social distancing to minimize the spread of the virus [11, 12]. In addition, at least for some patients, telemedicine is the preferred modality due to its ease of use and decreased travel time needed [11].

In rheumatology, various reports have broadly documented the use of telemedicine, highlighting both its advantages and potential drawbacks [1]. The British Society for Rheumatology has issued guidance for patients on immunosuppressants during the present period, which includes the advice to remain at home as much as possible [13], and it has been reported that many rheumatology clinics in the UK have temporarily converted large proportions of outpatient activity to telephone clinics [14, 15]. Notwithstanding the obvious advantages of telemedicine, which are amplified during the current pandemic, and the many reports of its use, in reality only very few studies have been published on the impact of telemedicine in care of patients in rheumatology clinics. As mentioned, RA, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are pathologies often treated with immunosuppressive agents and as such may be associated with infections and adverse reactions. Patients thus require close follow-up to provide prompt intervention and monitor for comorbidities and disease flare-ups.

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, given the lockdown and increasingly distressed healthcare situation in northern Italy, from March 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020, all patients with RA, PsA, or AS being treated at our clinic with a subcutaneous biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (bDMARD) or oral targeted synthetic DMARD (tsDMARD) were followed remotely. In this regard, it is also important to point out that for regulatory reasons, in Lombardy, subcutaneous bDMARDs or oral tsDMARDs must be given to patients every 2 months following an office visit. To shed more light on the feasibility and impact of telemedicine in this setting, we present outcomes of these patients before and after this 3-month period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was a retrospective database analysis of all patients diagnosed with RA, PsA, or AS and undergoing treatment with non-intravenous bDMARDs or oral tsDMARDs therapies at the Department of Rheumatology at Niguarda Hospital in Milan. The study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee (#8568). Data were collected on basic demographics, diagnosis, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs). All patients were contacted directly by telephone by a rheumatologist. During the phone call, the patient was queried about the possible onset of signs of disease activity, manifestation of side effects related to therapy, comorbid pathologies, and COVID-19-related symptoms that might require the need for an outpatient rheumatological visit. Patients had the possibility to enter data on PROs remotely or before the visit into iAR Plus, an informatic platform dedicated to rheumatic patients [16], which was also reviewed if deemed necessary during the call. If there were no critical issues, the outpatient visit was postponed for 2 months. bDMARDs and tsDMARDs were delivered directly to the patient's home thanks to an agreement with a delivery service that is specialized in the pharmaceutical field. If, on the other hand, the patient had developed a disease flare, side effect, or telephone management was considered inadequate, an urgent outpatient re-evaluation was scheduled. All the patients gave written informed consent to the anonymous collection of their data at the moment of registration to IARplus.

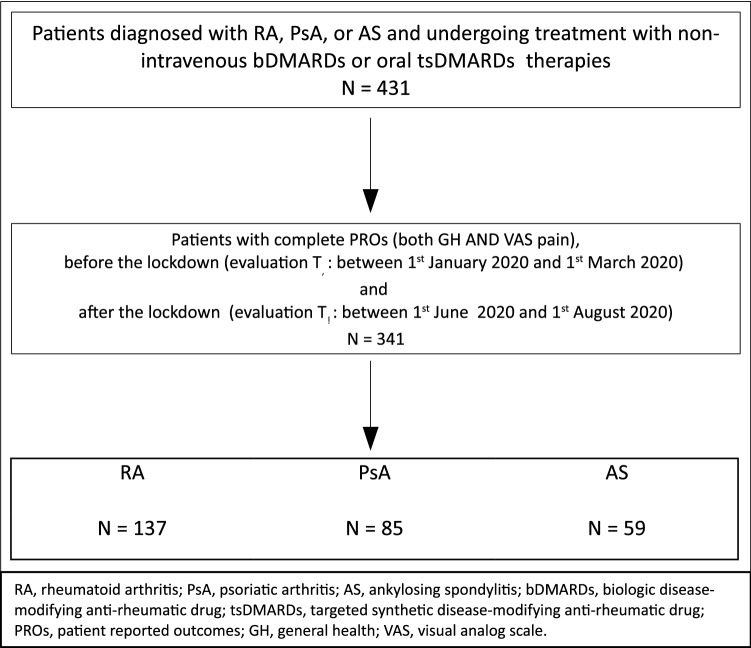

We evaluated the PROs of all patients before the lockdown (evaluation T0: between 1st January 2020 and 1st March 2020) and after the lockdown (evaluation T1: between 1st June 2020 and 1st August 2020) (Fig. 1). The only exclusion criterion was the lack of complete GH or VAS pain in any of these time intervals.

Fig. 1.

Study flow

Outcome measures

The main outcomes were general health (GH) and VAS pain which patients reported by compiling online questionnaires on the iAR Plus digital platform. GH was assessed by asking patients the question, ‘Considering all the ways in which illness and health conditions affect, please indicate how you are doing’ from 0 to 100 with 0 the lowest and 100 as the highest. VAS pain was evaluated on a scale from 0 to 100 with 0 as the least pain and 100 as the most pain. Further general [Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) and disease-specific PRO measures (Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI), Recent-Onset Arthritis Disability (ROAD), PRO-CLinical ARthritis Activity (PRO-CLARA) for RA, and Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath AS Functional Index (BASFI), Bath AS Global Index (BASGI) for AS] were available and explored as secondary outcomes [17–19]. PROs were compiled on the digital platform at home or at the clinic without use of a telephone. During telephone visits, we also evaluated PROs to obtain additional information.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of the main and the secondary outcomes at evaluation T0, after the lockdown at evaluation T1, and their variations (T1–T0) were explored as well as predictors (age, gender, disease, treatment with glucocorticoids, csDMARDs, bDMARDs, or tsDMARDS). The analyses were performed in entire series after assessment of the distribution of the missing data. Comparisons were made by Pearson chi-square tests for non-continuous variables, two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) tests for non-normal continuous data, and ordinary least-squares linear regressions for data which were normally distributed. Univariable and adjusted point estimates and their 95% confidence intervals were reported. Stata Statistical Software Release 15 (StataCorp. 2017, College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) was used for the analyses. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study flow is indicated in Fig. 1. During the lockdown period from March 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020, a total of 431 patients with RA, PsA, or AS underwent clinical evaluation or assessment by telephone interview. Of these, PROs before (Jan 1, 2020 to March 1, 2020) and after (June 1, 2020 to August 1, 2020) the lockdown were available for 341 patients (Table 1). The mean age was 57.6 years and 37.2% were male. The vast majority were receiving a bDMARD, and only 7 patients (2.1%) were receiving a JAK inhibitor. About one-third (32.2%) of patients were also receiving a concomitant csDMARD. The only significant differences between patients with complete data and those with missing data (not included in the present analysis) were for those with at least one visit (complete data 34.9% vs. 51.1% missing data, p < 0.01; Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Features of the study population

| Overall | RA | PsA | AS | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 341 | N = 197 | N = 85 | N = 59 | ||

| Age, years, mean (sd) | 57.6 (13.2) | 61.3 (12.9) | 56.1 (11.3) | 47.7 (11.5) | < 0.01 |

| Male, n (%) | 127 (37.2) | 40 (20.3) | 49 (57.7) | 38 (64.4) | < 0.01 |

| GCs ≥ 7.5 mg per day, n (%) | 17 (5.0) | 16 (8.1) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| csDMARDs, n (%) | 112 (32.8) | ||||

| Methotrexate | 87 (25.5) | 65 (33.0) | 20 (23.5) | 2 (3.4) | < 0.01 |

| Others | 32 (9.4) | 24 (12.2) | 4 (4.7) | 4 (6.8) | 0.124 |

| s | |||||

| TNFi | 232 68.0) | 115 (57.8) | 63 (74.1) | 54 (91.5) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-IL6 | 33 (9.7) | 33 (16.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-IL1 | 4 (1.2) | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-CTLA4 | 38 (11.4) | 38 (19.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| JAKi | 7 (2.1) | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-IL17 | 21 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 16 (18.8) | 5 (8.5) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-PDE4 | 6 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (7.1) | 0 (0) | < 0.01 |

| At least 1 visit performed, n (%) | 119 (34.9) | 76 (38.6) | 28 (32.9) | 15 (25.4) | 0.19 |

GCs glucocorticoids, csDMARDs conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, bDMARDs biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, Anti-IL6 Anti-interleukin 6, Anti-IL1 Anti-interleukin 1, Anti-CTLA4 Anti-Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4, JAKi Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, Anti-IL17 Anti-interleukin 17, Anti-PDE4 Anti-phosphodiesterase-4, RA rheumatoid arthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis, AS ankylosing spondylitis

*Pearson chi-square test

Thanks to the telephone evaluation, compilation of PROs using the iAR Plus digital platform, and the possibility to deliver drugs directly to patients, 449 visits were postponed, representing 69.9% of all scheduled visits. Telephone evaluation was not deemed sufficient in 193 instances, and in these cases, the patient was evaluated with a standard outpatient visit and the drug was given to patients at the hospital. Considering all three pathologies, no significant difference was seen in either GH or VAS pain before or during the lockdown.

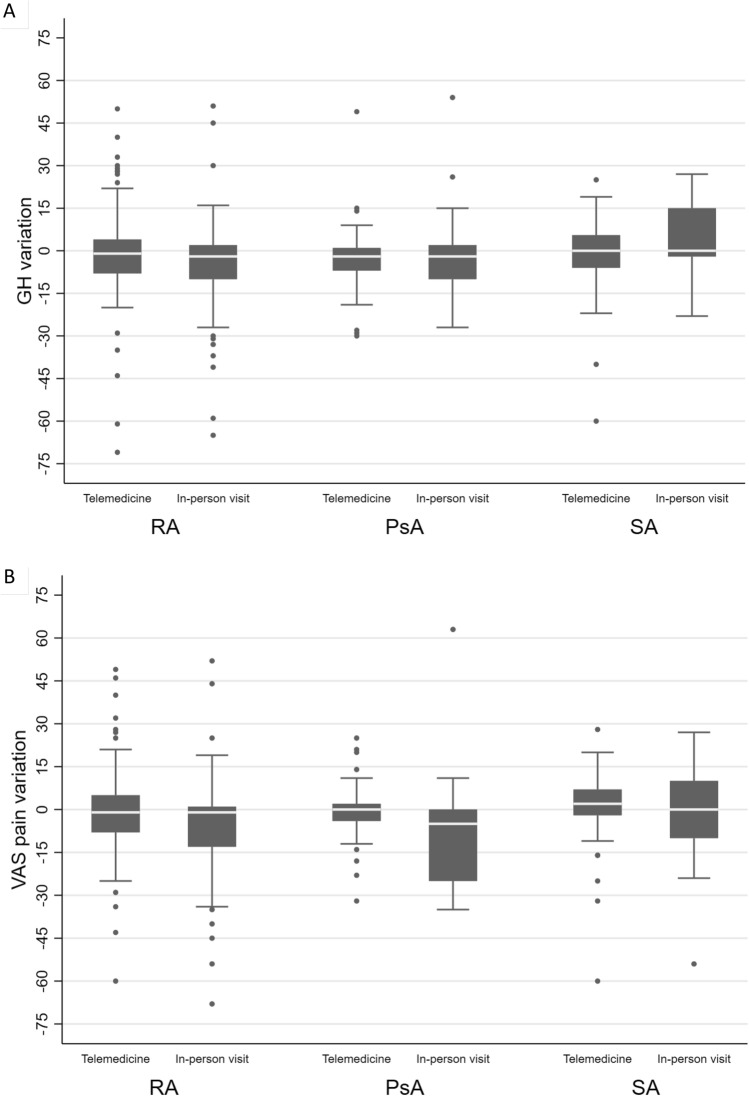

Patients were then divided into those undergoing at least one in-person visit during the 3-month period and those evaluated by telemedicine alone during the same period (Table 2, Fig. 2). Comparisons were made between clinical visits before and after the 3-month lockdown. In the overall group, similar GH scores in those undergoing in-person visits as well as those followed by telemedicine were seen before (T0: 42.5 vs 36.9; p = 0.16) and after (T1: 39.3 vs 35.3; p = 0.24) the lockdown. No significant differences in GH were seen between those undergoing in-person visits with those evaluated by telemedicine in any of the three pathologies considered individually. Likewise, for VAS pain, no significant differences were seen between patients undergoing clinical evaluation and those assessed by telemedicine before (T0: 42.3 vs 34.3; p = 0.24) and after (T1: 37.1 vs 33.3; p = 0.29) the lockdown.

Table 2.

Comparisons of general health (GH) and visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores between patients who were visited at least once (= in-person visit) and those who were assessed by telemedicine only (= telemed)

| Overall | RA | PsA | AS | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 341 | n = 197 | n = 85 | n = 59 | ||

| GH, 0–100 score, the highest the worst, mean (sd) | |||||

| T0 | 38.9 (28.7) | 43.1 (29.3) | 30.4 (23.7) | 35.8 (30.8) | < 0.01 |

| T1 | 36.7 (28.6) | 40.4 (29.0) | 27.8 (25.0) | 36.4 (28.9) | < 0.01 |

| Δ T1–T0 | − 2.3 (15.6) | − 2.7 (16.9) | − 2.6 (13.3) | 0.07 (14.5) | 0.26 |

| VAS pain, 0–100 score, the highest the worst, mean (sd) | |||||

| T0 | 37.2 (28.8) | 40.9 (29.4) | 40.9 (29.4) | 34.6 (30.1) | < 0.01 |

| T1 | 35.0 (27.6) | 37.9 (28.4) | 37.9 (28.4) | 35.3 (28.3) | 0.01 |

| Δ T1–T0 | − 2.4 (15.5) | − 3.0 (16.1) | − 3.0 (16.1) | − 0.2 (15.6) | 0.31 |

| In-person visit n = 119 | Telemed n = 222 | P§ | In-person visit n = 76 | Telemed n = 121 | P§ | In-person visit n = 29 | Telemed n = 56 | P§ | In-person visit n = 15 | Telemed n = 44 | P§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GH, 0–100 score, the highest the worst, mean (sd) | ||||||||||||

| T0 | 42.5 (31.0) | 36.9 (27.2) | 0.16 | 48.1 (32.6) | 40.0 (26.7) | 0.09 | 28.7 (22.3) | 31.3 (24.6) | 0.75 | 40.5 (30.3) | 35.7 (31.3) | 0.49 |

| T1 | 39.3 (29.3) | 35.3 (28.2) | 0.24 | 43.1 (29.0) | 38.7 (28.1) | 0.35 | 28.7 (26.0) | 26.2 (23.2) | 0.68 | 44.7 (28.7) | 34.4 (30.1) | 0.25 |

| VAS pain, 0–100 score, the highest the worst, mean (sd) | ||||||||||||

| T0 | 42.3 (31.5 | 34.3 (26.3) | 0.05 | 45.8 (33.4) | 37.8 (26.4) | 0.15 | 31.2 (24.1) | 28.2 (22.3) | 0.59 | 45.6 (30.4) | 32.3 (29.8) | 0.18 |

| T1 | 37.1 (28.8) | 33.3 (27.3) | 0.29 | 40.4 (29.9) | 36.4 (27.5) | 0.41 | 24.7 (24.8) | 27.6 (24.0) | 0.44 | 43.9 (24.7) | 32.3 (30.1) | 0.08 |

GH general health, VAS visual analog scale, T0 patient-reported outcome evaluation before lockdown: between 1st January 2020 and 1st March 2020), T1 patient-reported outcome evaluation after lockdown: between 1st June 2020 and 1st August 2020), Δ T1–T0 Variation between patient-reported outcomes in T1 and T0,, RA rheumatoid arthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis, AS ankylosing spondylitis

*One-way analysis of variance; §Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of the variations (Δ T1–T0) of general health (GH) and visual analog scale (VAS) pain between patients who were visited at least once (= in-person visit) and those who were assessed by telemedicine only (= telemedicine). a Change in Δ T1–T0 GH; b change in Δ T1–T0 VAS pain

Table 3 shows the comparisons of differences seen in GH and VAS pain between patients visited clinically and those undergoing telemedicine assessment. In univariate analysis, the only significant difference was in the overall group in which patients in the clinical visit group had significant variations in VAS pain compared to those visited by telemedicine, but which did not remain significant after adjustment with confounding variables. In the analysis adjusted for age, sex, therapy with a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), and PROs at baseline, the only significant difference was in patients with AS in which those evaluated by telemedicine had a statistically significant variation compared to those undergoing at least one clinical visit for GH, but not for VAS pain.

Table 3.

Comparison of variations in general health (GH) and visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores between patients who were visited at least once and those who were assessed by telemedicine only

| Overall | Rheumatoid arthritis | Psoriatic arthritis | Ankylosing spondylitis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 341 | N = 197 | N = 85 | N = 59 | |||||

| Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) | Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) | Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) | Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) | |

| GH, score 0–100, Δ T1-T0 | ||||||||

| Age, 1-year unit | 0.04 (− 0.09, 0.17) | − | 0.13 (− 0.05, 0.31) | − | − 0.10 (− 0.36, 0.16) | − | 0.10 (− 0.23, 0.44) | − |

|

Male Female as ref |

− 1.37 (− 4.8, 2.1) | − | − 5.8 (− 11.70, 0.03) | − | 1.29 (− 4.56, 7.15) | − | 0.25 (− 7.70, 8.2) | − |

|

TNFi Other bDMARDs as ref |

3.05 (− 0.53, 6.61) | − | 3.08 (− 1.73, 7.90) | − | 3.81 (− 2.76, 10.37) | − | − 4.95 (− 18.57, 8.67) | − |

| GH at baseline | − 0.15 (− 0.21, − 0.10) | − | − 0.18 (− 0.25, − 0.10) | − | − 0.10 (− 0.22, 0.02) | − | − 0.14 (− 0.26, − 0.02) | − |

| At least 1 visit | − 1.61 (− 5.12, 1.89) | − 0.59 (− 3.97, 2.79) | − 3.70 (− 8.57, 1.17) | − 1.99 (− 6.60, 2.62) | 0.07 (− 6.08, 6.24) | 0.42 (− 5.88, 6.72) | 5.54 (− 3.08, 14.16) | 8.87 (0.57, 17.16) |

| VAS pain, score 0–100, Δ T1–T0 | ||||||||

| Age, 1-year unit | 0.10 (− 0.02, 0.23) | − | 0.20 (0.03, 0.37) | − | − 0.10 (− 0.36, 0.16) | − | 0.35 (− 0.0004, 0.70) | |

|

Male Female as ref |

− 1.03 (− 4.43, 2.37) | − | − 2.87 (− 8.50, 2.75) | − | − 0.98 (− 6.94, 4.98) | − | − 1.34 (− 9.94, 7.25) | |

|

TNFi Other bDMARDs as ref |

0.70 (− 2.83, 4.22) | − | 0.74 (− 3.87, 5.34) | − | 1.63 (− 5.09, 8.35) | − | − 10.48 (− 25.00, 4.04) | |

| GH at baseline | − 0.17 (− 0.22, − 0.11) | − | − 0.18 (− 0.26, − 0.11) | − | − 0.12 (− 0.24, 0.01) | − | − 0.17 (− 0.30, − 0.05) | |

| At least 1 visit | − 4.3 (− 7.70, − 0.85) | − 2.9 (− 6.21, 0.34) | − 3.99 (− 8.62, 0.64) | − 2.28 (− 6.61, 2.06) | − 5.87 (− 12.01, 0.27) | − 5.32 (− 11.60, 0.95) | − 1.80 (− 11.25, 7.64) | 5.54 (− 2.99, 14.07) |

CI confidence interval, GH general health, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, VAS visual analog scale, T0 patient-reported outcome evaluation before lockdown (between 1st January 2020 and 1st March 2020), T1 patient-reported outcome evaluation after lockdown (between 1st June 2020 and 1st August 2020), Δ T1–T0 Variation between patient-reported outcomes in T1 and T0,

*Adjusted for age, gender, anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy, and baseline patient-reported outcomes

Data were also available for PROs using evaluation tools specific for each pathology, and differences before and after the lockdown were compared by univariable and multivariable analysis (Table 4). No significant differences were seen for the group undergoing in-person visits and those receiving telemedicine considering FACIT, or disease-specific questionnaires for RA (RADAI, ROAD, PROCLARA) or AS (BASDAI, BASG, BASFI).

Table 4.

Comparison of variations (T1–T0) in disease-specific patient-reported outcomes between patients who were visited at least once and those who were assessed by telemedicine only

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Psoriatic arthritis | Ankylosing spondylitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least 1 visit | Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) | Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) | Univariate (95% CI) | Multivariate* (95% CI) |

| N = 189 | – | – | ||||

| RADAI | − 0.33 (− 0.71, 0.06) | − 0.21 (− 0.58, 0.16) | – | – | – | – |

| ROAD | − 0.21 (− 0.51, 0.09) | − 0.16 (− 0.45, 0.13) | – | – | – | – |

| N = 185 | − | – | ||||

| PROCLARA | − 0.32 (− 0.67, 0.02) | − 0.24 (− 0.57, 0.08) | – | – | – | – |

| N = 190 | N = 82 | N = 58 | ||||

| FACIT | 1.14 (− 0.50, 2.78) | 0.96 (− 0.64, 2.57) | 0.46 (− 2.35, 3.27) | 0.34 (− 2.29, 2.97) | 2.46 (− 1.64, 6.56) | 0.65 (− 3.32, 4.61) |

| – | – | N = 55 | ||||

| BASDAI | – | – | – | – | 0.33 (− 0.16, 0.83) | 0.38 (− 0.13, 0.90) |

| BASG | – | – | – | – | − 0.02 (− 1.86, 1.82) | 0.46 (− 1.38, 2.31) |

| – | – | N = 54 | ||||

| BASFI | – | – | – | – | − 0.43 (− 1.98, 1.12) | 0.03 (− 1.66, 1.73) |

CI Confidence interval, RADAI Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index, ROAD Recent-Onset Arthritis Disability, PROCLARA Patient Reported Outcomes CLinical ARthritis Activity, FACIT Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASG Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index

*Adjusted for age, gender, anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy, and baseline patient-reported outcomes

Discussion

While there is much promise for the use of telemedicine in rheumatology, to date, there are scarce data on the efficacy of telemedicine approaches in patients with RA, PsA, or AS. Patients on biological therapies require close monitoring, for which telemedicine has the potential to reduce the number of clinical visits. Thus, telemedicine is very valuable to both clinicians and patients during the present pandemic for several reasons. Overall, our study found no clinically significant differences between PROs before and after a 3-month period of using either telemedicine or in-person visits. During telemedicine visits, a rheumatologist queried the patient directly about their disease, side effects related to therapy, comorbidities, and COVID-19-related symptoms that might require a clinical visit. If any critical issues were identified or telephone management was considered inadequate, an urgent outpatient visit was scheduled. In fact, the exclusive use of telemedicine and the impossibility to deliver drugs could increase the risk of relapses of autoimmune diseases [20]. The use of a flexible approach, the possibility to assess PROs using the iAR Plus app, and the ability to deliver drugs directly to patients allowed for a reduction in the number of clinical visits by 69.9%, while maintaining therapeutic continuity. Moreover, despite this reduction, after the lockdown, there was no clinically significant worsening of PROs in patients receiving immunomodulating therapy.

In the present analysis, all telemedicine visits were made via telephone, which was imposed by the need for a rapid solution for an impending problem. However, it is clear that a telemedicine approach could be improved upon by the use of video calls, allowing for the ability to see a patient’s joints, for example. Cavagna et al. recently carried out a survey of 175 patients with a median age of 63 years attending a rheumatology clinic in Northern Italy [5]. Of these, 80% referred that they owned a device that can make video calls, with 86% saying that they would be able to attend a telemedicine visit using video either alone or with the help of a relative. Moreover, 78% of patients considered telemedicine acceptable and 61% even preferred it. This suggests that telemedicine might be considered as a viable approach in rheumatology patients even after the pandemic. In this regard, Ramão et al. recently published a flowchart for possible reorganization of rheumatology clinics during and after the pandemic [21] in which it is suggested that telemedicine can be implemented into daily practice. These authors further note that most patients treated with bDMARDs and tsDMARDs can be monitored using telemedicine. To fully achieve the benefits of telemedicine and save patients unnecessary travel to the clinic, better communication between rheumatologists and the general practitioner will be needed, which should include shared access to patient records and improved coordination of routine care such as blood tests [22]. In addition, patients can be given educational additional resources online along with questionnaires for disease severity and functional status, similar to the PROs used herein. Patients appear to be satisfied with these tools and are willing to use them [23].

For other authors, telemedicine has been proposed as a triage tool during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that its use should depend on the state of diagnosis, disease severity, and treatment administered [24]. In a study of 176 patients seen in a general tele-rheumatology setting, for example, almost 20% of all patients were considered to be inappropriate for such an approach [24]. The best candidates for telemedicine are likely to be those with an established diagnosis and stable disease, and who can undergo a screening visit prior to in-person follow-up. On the other hand, it may not be the most appropriate option for patients with a disease flare, or when the complexity of their disease makes follow-up difficult to carry out remotely [25]. For these reasons, we preferred to adopt a flexible approach, allowing urgent clinical visits whenever, and for whatever reason, a telephone visit was not adequate.

Among the limitations of our study, we report outcomes of patients who were followed for only 3 months via telemedicine, comparing PROs at periods preceding and succeeding that period. Thus, longer term data on the efficacy of a telemedicine approach over time are lacking. In addition, we did not assess clinical outcomes, but only PROs. Notwithstanding, PROs are now considered as an important component to evaluating the impact of the disease and response to therapy [26]. Indeed, PROs are especially important in diseases such as RA and PsA, which can have substantial negative impact on the patient’s quality of life from multiple points of view [26, 27]. PROs are thus important in evaluating the overall success of therapy.

In summary, we found no substantial differences in outcomes when a telemedicine approach was used for a brief period in patients with RA, PsA, or AS. While it is clear that additional data are needed in the long term, and that the approach used can be improved upon, telemedicine has undoubted benefits, especially in light of the present COVID-19 pandemic. It is likely that many patients with these diseases may prefer it, at least for some follow-up visits. Finally, more work is needed to better define the patients for whom telemedicine is most appropriate, such as in those with a definite diagnosis, stable disease, and those living in rural settings. Notwithstanding these challenges, telemedicine appears to have significant benefit for both patients with spondyloarthritis and those treating it.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patrick Moore, who provided editorial assistance on behalf of Health Publishing & Services Srl. This unconditional support was funded by Novartis Farma.

Author contributions

MC, LB: followed clinical course of the patients and wrote paper, and performed telemedicine visits and medical examinations. NU: wrote the paper, analyzed clinical data and provided statistical analysis, and performed telemedicine visits and medical examinations. AA, CC, MDC, DAF, MM, ES, and EV: performed telemedicine visits and medical examinations. CC, CD, AL, EMV, and MGG: assisted patients in PROs completion on iAR Plus BDR; LZ: coordinated nursing staff. OME: designed the study and revised the draft paper. All the authors approved the final version.

Funding

This study was not funded by any society or institute.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.C., upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Consent to participate and for publication

All the patients gave written informed consent to the anonymous collection and publication of their data at the time of subscription to iAR Plus.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bonfa E, Gossec L, Isenberg DA, Li Z, Raychaudhuri S. How COVID-19ischangingrheumatology clinicalpractice. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00527-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzzetta G, Poletti P, Ajelli M, et al. Potential short-term outcome of an uncontrolled COVID-19 epidemic in Lombardy, Italy, February to March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.12.2000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):685–699. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavagna L, Zanframundo G, Codullo V, Pisu MG, Caporali R, Montecucco C. Telemedicine in rheumatology: a reliable approach beyond the pandemic. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masini F, Gjeloshi K, Ferrara R, Pinotti E, Cuomo G. Rheumatic disease management in the Campania region of Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(9):1537–1538. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04648-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos-Moreno P, Chavez-Chavez J, Hernandez-Zambrano SM, et al. Experience of telemedicineuseina big cohort ofpatients withrheumatoid arthritisduring COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeb AE, Rao SS, Ficke JR, Morris CD, Riley LH, 3rd, Levin AS. Departmental experience and lessons learned with accelerated introduction of telemedicine during the COVID-19 crisis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(11):e469–e476. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Krupinski EA, et al. National telemedicine initiatives: essential to healthcare reform. Telemed J E Health. 2009;15(6):600–610. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.9960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, Tran L, Vela J, Brooks M. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016242. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waller M, Stotler C. Telemedicine: a primer. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18(10):54. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.British Society of Rheumatology. COVID-19 guidance. https://www.rheumatology.org.uk/news-policy/details/Covid19-Coronavirusupdate-members. Accessed 9 Nov 2020

- 14.Jethwa H, Abraham S. Should we be using the Covid-19 outbreak to prompt us to transform our rheumatology service delivery in the technology age? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(7):1469–1471. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nune A, Iyengar K, Ahmed A, Sapkota H. Challenges in delivering rheumatology care during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(9):2817–2821. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05312-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epis OM, Casu C, Belloli L, et al. Pixel or paper? validation of a mobile technology for collecting patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(4):e219. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson JK, Zimmerman L, Caplan L, Michaud K. Measures of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: Patient (PtGA) and Provider (PrGA) Global Assessment of Disease Activity, Disease Activity Score (DAS) and Disease Activity Score with 28-Joint Counts (DAS28), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Patient Activity Score (PAS) and Patient Activity Score-II (PASII), Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID), Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI) and Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index-5 (RADAI-5), Chronic Arthritis Systemic Index (CASI), Patient- Based Disease Activity Score With ESR (PDAS1) and Patient-Based Disease Activity Score without ESR (PDAS2), and Mean Overall Index for Rheumatoid Arthritis (MOI-RA) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S14–36. doi: 10.1002/acr.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salaffi F, Ciapetti A, Gasparini S, et al. Comparison of the recent-onset arthritis disability questionnaire with the health assessment questionnaire disability index in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(6):855–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salaffi F, Migliore A, Scarpellini M, et al. Psychometric properties of an index of three patient reported outcome (PRO) measures, termed the CLinical ARthritis Activity (PRO-CLARA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The NEW INDICES study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(2):186–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naveen R, Sundaram TG, Agarwal V, et al. Teleconsultation experience with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a prospective observational cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04737-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romao VC, Cordeiro I, Macieira C, et al. Rheumatology practice amidst theCOVID-19pandemic:apragmaticview. RMD Open. 2020 doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim AY, Tan CS, Low BP, et al. Integrating rheumatology care in the community: can shared care work? Int J Integr Care. 2015;15:e031. doi: 10.5334/ijic.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhao L, Xiao J, Shi Z. Online management of rheumatoidarthritisduring COVID-19pandemic. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulcsar Z, Albert D, Ercolano E, Mecchella JN. Telerheumatology: a technology appropriate for virtually all. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(3):380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figueroa-Parra G, Gamboa-Alonso CM, Galarza-Delgado DA (2020) Challenges and opportunities in telerheumatology in the COVID-19 era. Response to: Online management of rheumatoid arthritis during COVID-19 pandemic' by Zhang et al. Ann Rheum Dis 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217631 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Orbai AM, Ogdie A. Patient-reported outcomes in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016;42(2):265–283. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Tuyl LH, Michaud K. Patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016;42(2):219–237. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.C., upon reasonable request.