Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer death among men in North America.1 There is an approximate one in seven lifetime incidence within U.S. males. Most of these patients present with localized disease, however, approximately 1/3 of these men do progress to metastatic disease at some point within their lives.2,3 This has led to the current, and ongoing, research into novel treatments and regimens for metastatic prostate cancer (mPCa), with emerging evidence advocating for additional second-line androgen blocking agents to be used up front in addition to baseline androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).4–6 Despite continued advancements in the management of mPCa, ADT still plays an important foundational component of treatment regimens. Currently, most cases of mPCa in North America are treated with pharmacological ADT rather than the historical alternative of surgical castration. The increased use of pharmacological ADT has likely contributed to dramatic increase in the cost of mPCa on a population level.7

Surgical castration remains an important treatment modality of mPCa across the world and is recommended as an alternative first-line ADT treatment in multiple practice guidelines.8,9 Additionally, a previous cost analysis by the same authors has identified the potential for significant cost savings through increased use of surgical castration in the treatment of mPCa.10 We have previously shown the average cost of medical ADT drugs alone over five years to be approximately $20 000 per patient. This does not include the cost of providing the injections or required travel for many patients and their family. The cost of a bilateral orchiectomy at our institution with general anesthesia can be performed for less than $5000.

Canadian urologists have a leadership role within our public healthcare system. This requires us to be stewards to the system and use resources efficiently. In fact, this responsibility has been enshrined in the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework published by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.11 Given the equal treatment effect of surgical castration in mPCa and the potential for significant cost savings, it is important to identify barriers preventing wider use of this treatment. Here, we aimed to identify current practice patterns and attitudes of urologists practicing in Canada towards surgical castration in the treatment of PCa.

Methods

To assess the current practice trends and attitudes of Canadian urologists towards the use of surgical castration in the treatment of mPCa, an electronic survey was developed. This survey was available in both French and English and was distributed to approximately 700 urologists across Canada. Inclusion criteria stipulated that respondent must be a FRCSC-certified urologist or fellow-level trainee, who treats prostate cancer, and is currently practicing in Canada. The survey (Appendix; available at cuaj.ca) was constructed using SurveyMonkey (San Mateo, CA, U.S.) and distributed via email. Responses were collected during a two-week window in March 2018. Information collected included practice demographics and current practices in the treatment of mPCa. Responses were then analyzed in a descriptive fashion, with an aim of generating discussion around the use of surgical castration as ADT in prostate cancer. The study and survey received REB approval via the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Results

Demographics

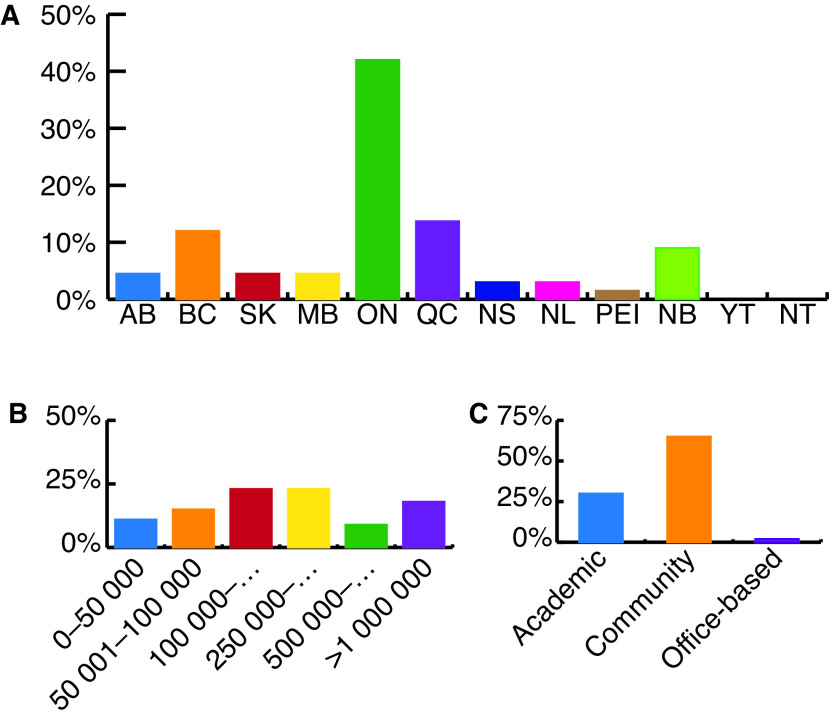

Survey results were carefully analyzed to ensure each respondent met study inclusion criteria. Of all surveys returned, 108 (15%) were eligible for inclusion in the study. Responses were obtained from urologists practicing in all 10 Canadian provinces (Fig. 1A). A variety of large, small, community, academic, and office-based practices were also represented in survey responses (Figs. 1B, 1C).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of practice demographics from responding urologists by: (A) province/territory; (B) community population; (C) practice type.

Practice patterns

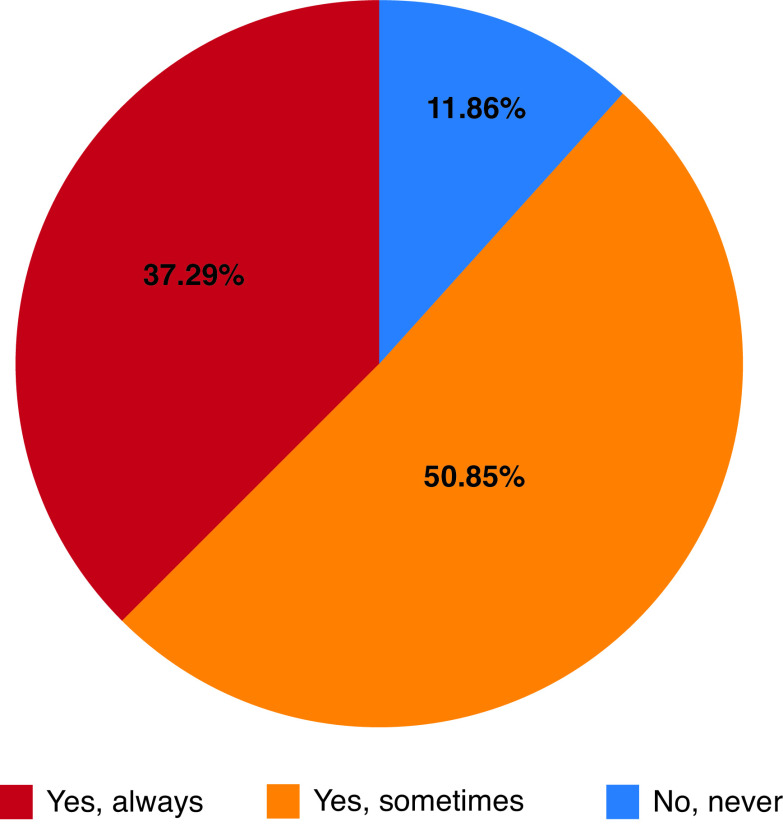

When asked how often survey respondents offered surgical castration to eligible patients, 38% reported never offering surgical castration and 51% indicated they only sometimes offered surgical castration. Only 11% of respondents indicated they routinely offer surgical castration as ADT for eligible patients (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of survey respondents routinely offering surgical castration as a form of androgen deprivation therapy.

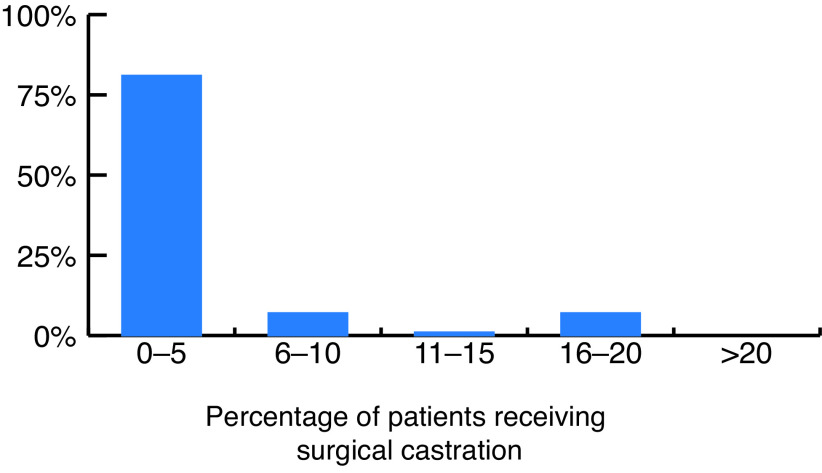

When asked how many of their eligible patients have received surgical castration, 81% of respondents estimated this to be less than 5% (Fig. 3). Common factors identified by survey respondents preventing wider offering and use of surgical castration are summarized in Table 1. The most cited factor preventing survey respondents from routinely offering surgical castration to eligible patients was the respondents’ perceived negative patient attitudes towards surgical castration. Other commonly reported barriers were lack of operating room availability, invasiveness, permanence, and the morbidity of the procedure.

Fig. 3.

Survey-respondent estimation of proportion of their patients receiving surgical castration for androgen deprivation therapy.

Table 1.

Most common respondent-cited reasons for not routinely offering surgical castration as ADT treatment for metastatic prostate cancer

| Factor | % of respondents |

|---|---|

| Perceived patient negative attitudes | 85% |

| Invasiveness | 56% |

| Lack of operating room availability | 41% |

| Permanence | 34% |

| Morbidity of surgery | 25% |

ADT: androgen deprivation therapy.

Attitudes toward surgical castration

When asked about their overall attitudes towards surgical castration, the majority (78%) of survey respondents agreed that surgical castration is as effective as pharmacological ADT in the treatment of mPCa. Seventy-three percent of respondents indicated that they feel surgical castration is an underused treatment modality and 67% of respondents indicated that Canadian urologists should more actively offer surgical castration as an equally efficacious treatment option compared to pharmacological ADT. Seventy-five percent of respondents indicated that they would like to see more data on the cost-effectiveness of surgical castration for the treatment of mPCa in the Canadian healthcare system.

Discussion

This qualitative, survey-based study aims to identify the current practice patterns and attitudes of Canadian urologists regarding the use of surgical castration in the treatment of mPCa. The importance of this question hinges on the concept that surgical castration has equal efficacy and is more cost-effective when compared to pharmacological ADT in the treatment of mPCa. In publicly funded healthcare systems, where physicians largely play the role of gate-keeper to treatments, it is important for physicians to be resource allocators and consider the cost-effectiveness of the treatments they are offering. A strong argument can therefore be made for Canadian urologists to offer and perform surgical castration more frequently.

As mentioned earlier, preliminary cost studies by our group have identified the potential for significant cost savings through increased use of surgical castration in the Canadian healthcare system.11 Similarly, increasing costs of prostate cancer has been associated with increased use of medical castration in the U.S.12–14 In addition to the treatment itself being more cost-effective, surgical castration also obviates the need for recurrent visits to the surgeon/physician office for ADT injections. This is even more advantageous when considering the impact on the population of patients who are dependent on family members or other transportation services to attend these appointments. Additionally, when the need for injection is negated, this allows for increased use of telehealth in followup, which has shown its utility with clinical restrictions during the current COVID-19 pandemic. As indicated in this survey, most respondents would like to see more data on the cost-effectiveness of surgical castration in the Canadian healthcare system.

Prior to the development of pharmacological ADT, surgical castration was the primary treatment for mPCa. Even after surgical castration use has been widely replaced by pharmacological ADT in the western world over the past 30 years, it remains recognized as an alternative first-line ADT method in practice guidelines from the Canadian Urological Association, the American Urological Association, the Society of Urologic Oncology, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Surgical castration remains a robust treatment that quickly achieves and maintains lasting castrate-levels of testosterone. Its equivalence to pharmacological ADT is well-recognized in the literature. This was agreed upon by most survey respondents. Additionally, the procedure can be performed in the outpatient setting under local, regional, or general anesthetic. For these reasons, it remains a first-line ADT therapy for the treatment of mPCa in numerous society guidelines.

Bilateral orchiectomy provides robust and permanent castration. It has been shown that fluctuations in testosterone are associated with worse prostate cancer-specific outcomes.15 Late dosing, interrupted schedules, incomplete castration, and microflares, which can be associated with medical castration regimens, are associated with worse outcomes and are avoided with surgical castration.16 In addition to prostate cancer-specific effects of ADT, there are important implications for other health outcomes, including fracture risk, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism, coronary artery disease, and development of diabetes. Sun et al showed, through a 15-year cohort study, that surgical castration was superior to gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy for treatment of mPCa in all these areas.17 Therefore, surgical castration may actually be more cost-effective and have a superior side-effect profile when compared to pharmacological ADT for treatment of mPCa.

Most respondents in this survey indicated that they agree that surgical castration is an underused treatment modality. Despite this, over half of respondents indicated they only sometimes offer surgical castration and nearly 40% indicated they never offer surgical castration to eligible patients. This poses the question of whether urologists are the main obstacle preventing wider use of surgical castration.

The main barrier identified in this study preventing respondents from routinely offering surgical castration was a respondent (physician)-perceived negative patient attitude towards the treatment. It is important to reinforce that this represents the anticipated patient response to being offered surgical castration and does not represent real patient attitudes towards the treatment. This preconception on the part of the physician may be due to past experience, personal attitude, or dogma, as the exposure to surgical castration within urology residency training programs is unlikely to be more common than reported in this survey overall.

While there is a paucity in the literature comparing psychological outcomes of surgical to medical castration, the available evidence does not support increased adjustment or mood disorders following bilateral orchiectomy for prostate cancer.18,19 Additionally, it has been shown that men with advanced prostate cancer treated with surgical castration report a higher quality of life compared to men receiving medical ADT.20 This is important information for a urologist to have when confronting their own biases and addressing patient concerns. There is no doubt a difficulty in counselling a patient on a permanent and disfiguring treatment, however, the urologist is better equipped to do so with the knowledge of equal efficacy, superior side-effect profile, and superior quality of life experienced by men receiving surgical castration compared to injection-based medical ADT.

Surgical castration is a permanent form of ADT and is therefore not a suitable form of ADT in patients who may be candidates for intermittent ADT in the biochemical recurrence (BCR) setting. However, surgical castration can still play a role, as eventually these patients progress and develop the requirement for lifelong ADT. This serves as an opportunity to re-address surgical castration as a durable form of baseline ADT. It is also important to note that surgical castration does not preclude, and can be used in conjunction with, chemotherapy and/or novel second-generation hormonal agents for control of metastatic disease.21

To increase the use of surgical castration, appropriate counselling on the part of the treating urologist is required. This requires a familiarity with surgical castration, and it is therefore important to ensure exposure to this treatment, and treatment discussion, in the training environment. In general, it has been shown that patients often have a poor understanding of mPCa, including their diagnosis, treatment options, and prognosis.22 Benidir et al have also demonstrated that with appropriate counselling, including cost of treatment, patient treatment goals do change measurably and that patient’s will often choose more cost-effective treatments when they understand the societal cost associated with various therapies.23 This highlights the need for appropriate and informative patient counselling in the clinical setting. Appropriate counselling of the patient should include risks of surgical castration in a patient-specific context, as well as the expected side-effect profile. When explaining the permanence of this procedure, it is important to also emphasize the similarity of anticipated side effects with pharmacological ADT when a patient is expected to be on lifelong therapy.

As stated previously, this study aimed at describing the current attitudes and practice patterns of Canadian urologists regarding surgical castration. Limitations of this study include that it is self-reported and survey-based. Rates of surgical castration reflect self-estimates of practice patterns by responding urologists. Urologists with an interest in treating advanced prostate cancer may be over-represented in the survey responses. For those respondents who sometimes offer surgical castration, specific data was not collected regarding which patients are offered orchiectomy. This study did not include responses from medical or radiation oncologists who also manage mPCa. As non-surgeons, these practitioners would not be expected to offer surgical castration.

Conclusions

This study indicates that surgical castration is likely an underused form of ADT in the treatment of prostate cancer in Canada. Most Canadian urologists surveyed do not routinely offer surgical castration as a form of ADT despite majority agreement in the efficacy. There is a potential for significant cost savings through the increased use of surgical castration and the majority of Canadian urologists would like to see more Canadian data on this.

The choice of treatment modality should ultimately be patient-driven. However, for patients to make an informed choice of treatment, they require appropriate counselling from their treating urologist. The authors feel that urologists have a duty to offer surgical castration to their eligible patients, both as part of informed decision-making and as stewards of the healthcare system. Future directions for this research include assessment of patient attitudes toward surgical castration, development of a patient decision aid, and detailed cost analyses of surgical castration within the Canadian healthcare system.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Appendix available at cuaj.ca

Dr. Anderson reports no competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

Competing interests: Dr. Rowe has been an advisory board member for Acerus, Baxter, and Sanofi.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Schatten H. Brief Overview of Prostate Cancer Statistics, Grading, Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies. In: Schatten H, editor. Cell & Molecular Biology of Prostate Cancer Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1095. Springer; Cham: 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Registry of Norway. Cancer in Norway 2015 Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seal BS, Asche CV, Puto K, et al. Efficacy, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and tolerability of the changing therapeutic landscape in patients with metastatic prostate cancer (MPC): A systematic literature review. Value Health. 2013;16:872–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. LATITUDE Investigators. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:352–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al. ENZAMET Trial Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:121–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, et al. ARCHES: A randomized, phase 3 study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2974–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norum J, Nieder C. Treatment for metastatic prostate cancer: A review of costing evidence. PharmacoEconomics. 2017;35:1223. doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.So AI, Chi KN, Danielson B, et al. Canadian Urological Association-Canadian Urologic Oncology Group guideline on metastatic castration-naive and castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2020;14:17–23. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. JNCCN. 2019;17:479–505. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson PT, Rowe NE. Potential for cost-savings through urologic prescribing habits in Ontario [abstract] University of Ottawa Department of Surgery Collins Day; Ottawa, Canada: May 12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkin EB, Bach PB. Cancer’s next frontier: addressing high and increasing costs. JAMA. 2010;303:1086–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott SP, Jarosek SL, Wilt TJ, et al. Reduction in physician reimbursement and use of hormone therapy in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1826–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krahn MD, Bremner KE, Luo J, et al. Healthcare costs for prostate cancer patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy: Treatment and adverse events. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e457–65. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saad F, Fleshner N, Pickles T, et al. Testosterone breakthrough rates during androgen deprivation therapy for castration-sensitive prostate cancer. J Urol. 2020;204:416–26. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford ED, Twardowski PW, Concepcion RS, et al. The impact of late luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist dosing on testosterone suppression in patients with prostate cancer: An analysis of United States clinical data. J Urol. 2020;203:743–50. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun M, Choueiri TK, Hamnvik OP, et al. Comparison of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and ochiectomy: Effects of androgen deprivation therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:500–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louda M, Valis M, Splichalova J, et al. Psychosocial implications and the duality of life outcomes for patients with prostate carcinoma after bilateral orchiectomy. Neuro Endocrinol Letters. 2012;33:761–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rud O, Peter J, Kheyri R, et al. Subcapsular orchiectomy in the primary therapy of patients with bone metastasis in advanced prostate cancer: an anachronistic intervention? Adv Urol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/190624. 190624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potosky AL, Knopf K, Clegg LX, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes after primary androgen deprivation therapy: Results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3750–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.17.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowrance W, Breau R, Chou R, et al. Advanced prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. J Urol. 2021;205:14–21. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rot I, Ogah I, Wassersug RJ. The language of prostate cancer treatments and implications for informed decision-making by patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21:766–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benidir T, Hersey K, Finelli A, et al. Understanding how prostate cancer patients value the current treatment options for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:240.e13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.