CLINICAL HISTORY AND RADIOLOGY

A female neonate was delivered at 38 weeks’ gestation to an 18‐year‐old, gravida 1, Native American female whose antepartum course was notable for crystal methamphetamine and tobacco use early in pregnancy. Prenatal care has been initiated at 11 weeks of gestation, and an ultrasound performed at approximately 20 weeks revealed findings interpreted as a large posterior fossa cyst with mass effect. The cerebellum has not been well visualized, although the impression was that some cerebellar tissues were present. These features were overall felt to reflect a Dandy–Walker cyst. Additional ultrasonographic impressions included a probable porencephalic cyst on the right side, ventriculomegaly, possible agenesis of the corpus callosum and overall significant absence of brain parenchyma in the right hemisphere. Serial follow‐up ultrasound evaluations were performed at approximate 4‐week intervals, demonstrating essentially the same intracranial ultrasonographic findings. Of note was that other organs showed appropriate growth progression.

At delivery by cesarean section, the posterior aspect of the neonate's scalp was noted to be covered by a thin, tense membrane, which ruptured during the procedure. Apgar scores were 7 and 9 at 1 minute and 5 minutes, respectively, and death occurred within hours of birth.

GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

At autopsy the face was normally formed. There was an absence of the skull, and cranial contents were enclosed by hair‐bearing skin (Figure 1). Within the right occipital region a scalp defect was present, characterized by a thin transparent membrane with focal rupture (Figure 2). The skull base was fully intact.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

The brain weighed 302 g, and after fixation a vague gyral pattern was seen from a superior view (Figure 3). The right hemisphere was predominantly cystic with an incomplete rim of brain parenchyma present. The cerebellum was not grossly identified, and the brainstem region showed partial replacement by a yellow‐tan firm tissue in continuity with a normal‐appearing spinal cord (Figure 4, arrow).

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

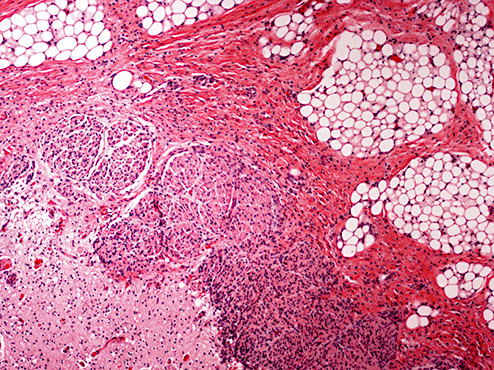

Microscopic examination of the right occipital region in the area of scalp defect revealed a thin membrane covering subjacent gliotic brain parenchyma and fibrovascular structures similar to cerebrovasculosa (Figure 5). The underlying occipital brain tissue showed features consistent with polymicrogyria (Figure 6) with relative preservation of neuronal lamination in focal areas (Figure 7). Sections of the regions corresponding to the brain stem demonstrated replacement of parenchyma by infiltrating mature lipomatous tissue in association with cranial nerves (Figure 8). However, residual brainstem nuclei, cerebellar folia and deep nuclei were microscopically identified.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

The general autopsy examination of the remainder of the body showed essentially all normal findings, with no additional malformations corresponding to a specific syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS AND DISCUSSION

Diagnoses

-

•

Primary acalvaria.

-

•

Polymicrogyria.

-

•

Partial destruction of brain stem and cerebellum.

Discussion

Acalvaria is a rare congenital malformation characterized by an absence of calvarial bones and dura mater, in the presence of a normal skull base, facial bones and scalp. This entity has been observed currently with a multitude of anatomic central nervous system (CNS) findings, including hydrocephalus, holoprosencephaly and polymicrogyria 4, 9. In the present case, by gross examination, the brainstem region appeared to be subtotally replaced by fibroadipose tissue; well‐formed cerebellar tissue was not identified; however, microscopic examination revealed residual brainstem nuclei as well as focal cerebellar tissue. As such, the partial replacement of normal anatomic structures are believed to reflect a destructive process whereby native CNS parenchyma is focally replaced by connective tissue, as opposed to reflecting additional coexisting primary malformative lesions.

Acalvaria has also been observed in association with non‐CNS findings including cardiac anomalies, omphalocele, hypertelorism, cleft lip and palate, renal tubular dysgenesis and concomitantly with the amniotic band syndrome 2, 3, 4, 5. Most cases are fatal, although rare living cases have been described 6, 7.

The precise pathogenesis of acalvaria is currently unknown. One theory postulates that it reflects a postneurulation defect with faulty migration of mesenchyme, but with normal placement of embryonic ectodermal derivatives. Consequently, there is absence of the calvarium, but has an intact layer of skin covering the brain parenchyma, as is demonstrated in this case. Another theory postulates that acalvaria results from primary non‐closure of the neural tube, and that this entity exists within and along a pathogenesis spectrum that includes anencephaly 1, 4, 8.

As a heterogeneous disorder, acalvaria has also been described in settings where periconception teratogenic exposure has not been apparent, where other birth defects were absent and where fetal karyotyping had been normal (2). Prevention by prenatal and perinatal folic acid consumption has not been described; however, high alpha‐fetoprotein levels in conjunction with undetectable unconjugated estriol levels during the fetal period have been observed 6, 8. However, associations with parental consanguinity (6) and with angiotensin‐converting enzyme‐inhibitor administration have been reported (1). Currently, no specific risk of recurrence has been documented in the subsequent pregnancies of women with acalvarial neonates.

This case illustrates an example of acalvaria with findings of polymicrogyria and absence of cerebellar brain tissue, associated with antepartum maternal tobacco and drug use. The maternal history of drug and tobacco use is regarded as an incidental association, and thus no inference into the direct or indirect cause‐effect relationship can be made.

ABSTRACT

A full‐term neonate was born to an 18‐year‐old, G1, Native‐American female whose antepartum course was notable for crystal methamphetamine use and tobacco smoking. Prenatal ultrasounds showed a posterior fossa cyst, ventriculomegaly and absence of brain tissue in the right hemisphere. At delivery, a scalp defect was present in the right occipital region and focally covered by a thin, tense membrane. Autopsy revealed acalvaria with cranial contents enclosed by hair‐bearing skin. The skull base was fully intact. Fixed brain weight was 302 g and a vague gyral pattern was appreciated. The right hemisphere was cystic with an incomplete rim of brain parenchyma. Cerebellum was not grossly identified; the brainstem region appeared replaced by yellow firm tissue in continuity with a normal‐appearing spinal cord. The face was normal, and the remaining organs demonstrated no malformations. Microscopy of the right occipital region revealed a thin membrane covering subjacent gliotic brain parenchyma with cerebrovasculosa features. The underlying occipital lobe showed polymicrogyria. The brainstem was partially replaced by mature lipomatous tissue with cranial nerves present. Cerebellar folia and deep nuclei were microscopically identified. Acalvaria is a rare entity with few reported cases. The precise etiology is unclear. This case demonstrates acalvaria associated with prenatal maternal drug use.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barr M, Cohen MM (1991) ACE inhibitor fetopathy and hypocalvaria: the kidney‐skull connection. Teratology 44:485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bianca S, Ingegnosi C, Auditore S, Reale A, Galasso MG, Bartoloni G et al (2005) Prenatal and postnatal findings of acrania. Arch Gynecol Obstet 271:256–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chandran S, Lim MK, Yu VY (2000) Fetal acalvaria with amniotic band syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 82:F11–F13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris CP, Townsend JJ, Carey JC (1993) Acalvaria: a unique congenital anomaly. Am J Med Genet 46:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hukki J, Balan P, Ceponiene R, Kantola‐Sorsa E, Saarinen P, Wikstrom H (2004) A case study of amnion rupture sequence with acalvaria, blindness, clefting: clinical and psychological profiles. J Craniofac Surg 15:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Nimbalkar AA, Kinnare AS (2004) Acalvaria. Indian Pediatr 41:618–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kurata H, Tamaki N, Sawa H, Oi S, Katayama K, Mochizuki M et al (1996) Acrania: report of the first surviving case. Pediatr Neurosurg 1996; 24:52–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moore K, Kapur RP, Siebert JR, Atkinson W (1999) Acalvaria and hydrocephalus: a case report and discussion of the literature. J Ultrasound Med 18:783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raupp P, Nork M, Kappel I (2003) Antenatal imaging of a near‐term fetus with primary acalvaria. Am J Perinatol 20:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]