CLINICAL HISTORY

A 64‐year‐old diabetic woman presented with progressive cognitive deterioration and gait ataxia. Symptoms appeared 1 month before admission, without hyperthermia. Clinical examination showed temporo‐spatial disorientation, loss in attention, judgment and memory capacities, a gait ataxia with a kinetic cerebellar syndrome and a left side bradykinesia. There was neither pyramidal syndrome nor cranial nerve palsy. General examination was normal. Brain MRI (T1 with and without gadolinium, FLAIR and T2) found a periventricular diffuse leukoencephalopathy (Figure 1A) without gadolinium enhancement (Figure 1B). EEG showed diffused slow waves and epileptic seizures without periodic paroxysmal activity. Hematological and biological serum analyses (including LDH, beta2‐microglobulinemia, fibrinogen, CRP, electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis of the proteins, transaminases, urea, creatinine, lymphocyte immunophenotyping) were normal. All serological investigations (HIV, HSV1 and HSV2, CMV, VZV, EBV, JC virus) remained negative. The CSF presented a normal cell count (2 lymphocytes/mm3) and protein level (0.3 g/L), without abnormal cells or intrathecal protein synthesis except for positivity of the 14.3.3 protein. The neurological state worsened progressively with dementia, epileptic seizures, extrapyramidal and cerebellar syndromes. The patient died 3 months after onset of symptoms, and an autopsy restricted to the brain was performed.

Figure 1.

GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION

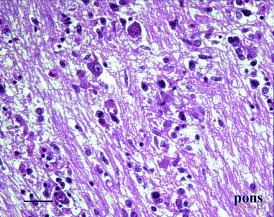

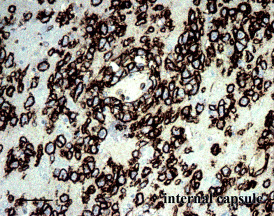

The brain weighed 1330 g. Coronal sections of the cerebral hemispheres, as well as horizontal sections of the cerebellum and brain stem were not informative. Microscopic examination revealed infiltrates of atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 2; bar = 400 µ) in the deep layers of cortex, white matter, basal ganglia, substantia nigra, pons, medulla and cerebellar white matter. These infiltrates were diffuse and present on all sections from the brain hemispheres, brain stem and cerebellum. In most areas, the tumor cells were scattered but atypia and mitoses were evident (Figure 3; bar = 100 µ). A perivascular distribution was noticed in some areas, and no necrosis was observed. There was a strong reactivity of the tumor cells for CD20 (Figure 4; bar = 100µ). A search for EBV by in situ hybridization was negative.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

DIAGNOSIS

Lymphomatosis cerebri.

DISCUSSION

Neither the clinical story of rapidly progressive dementia nor the diffuse leukoencephalopathy without gadolinium enhancement on MRI led to a diagnosis of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) in this patient. Most cases of PCNSL present with symptoms consistent with single or multiple intracranial mass lesions, and these are contrast enhancing on MRI (4). The diagnosis of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease was initially suggested in our case of rapidly progressive dementia with positivity of 14.3.3 protein in the CSF, but was not supported by neuroimaging findings and was immediately refuted by microscopic examination of autopsy specimens. Diffuse encephalitis was also considered as a possible diagnosis, but all clinical investigations in this way remained negative. No lesion was noticed at gross examination of the brain, and only microscopic examination permitted identification of scattered lymphomatous cells with cytologic atypia and mitoses on all sections from brain hemispheres, brain stem and cerebellum. Immunopositivity of these tumor cells for CD20 attested to their B‐cell phenotype.

A condition to discuss here is intravascular lymphomatosis because this systemic disorder may be revealed by neurologic manifestations including dementia resulting from the occlusion of small arteries of the brain with lymphoma cells (2, 3). The diffuse pattern of infiltration outside the lumens of blood vessels was absolutely different in our case.

In fact, Bakshi et al (1) reported two cases of diffusely infiltrating PCNSL involving much of the cerebral neuraxis and presenting as rapidly progressive dementia. By analogy with gliomatosis cerebri, the authors proposed the term “lymphomatosis cerebri” to qualify such an infiltrating PCNSL. No “lymphomatosis cerebri” has been reported since this first description, but the present observation illustrates that this entity should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a rapidly progressive dementia in adults.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bakshi R, Mazziotta JC, Mischel PS, Jahan R, Seligson DB, Vinters HV (1999) Lymphomatosis cerebri presenting as a rapidly progressive dementia: clinical, neuroimaging and pathologic findings. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 10:152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beristain X, Azzarelli B (2002) The neurological masquerade of intravascular lymphomatosis. Arch Neurol 59:439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glass J, Hochberg FH, Miller DC (1993) Intravascular lymphomatosis. A systemic disease with neurologic manifestations. Cancer 71:3156–3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Loiseau H, Cuny E, Vital A, Cohadon F (2000) Central nervous system lymphomas. In: Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery, vol. 26. Cohadon F, Dolenc VV, Lobo Antunes J, Pickard JD, Reulen H‐J, Sindou M, Strong AJ, De Tribolet N, Tulleken CAF, Vapalahti M (eds), pp. 80–124. Springer: Wien, NY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]