Abstract

In Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) metabolic and structural alterations of the central nervous system are described. Here, we investigated in the brain of 10 mdx mice and in five control ones, the expression of hypoxia inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α) and we correlated it with the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2) and of the endothelial tight junction proteins zonula occludens‐1 (ZO‐1) and claudin‐1. Results showed an activation of mRNA HIF‐1α by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) and a strong HIF1‐α labeling of perivascular glial cells and cortical neurons by immunohistochemistry, in mdx mouse. Moreover, overexpression of VEGF and VEGFR‐2, respectively, in neurons and in endothelial cells coupled with changes to endothelial ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 expression in the latter were detected by immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry, in the mdx brain. Furthermore, by immunoprecipitation, an up‐phosphorylation of ZO‐1 was demonstrated in mdx endothelial cells in parallel with the reduction in ZO‐1 protein content. These data suggest that the activation of HIF‐1α in the brain of dystrophic mice coupled with VEGF and VEGFR‐2 up‐regulation and ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 rearrangement might contribute to both blood–brain barrier opening and increased angiogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

In Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X‐linked recessive genetic neuromuscular disorder caused by a mutation in the X‐linked dystrophin gene (7), besides muscle fiber degeneration, alterations to the central nervous system (CNS) have been reported, responsible for mental retardation and metabolic damage (1, 8, 46).

The cerebral vascular compartment is involved in DMD. In fact, alterations of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) have been demonstrated in the mdx mouse, an animal model with a genetic defect in the region homologous with the human DMD gene, involving modifications in zonula occludens‐1 (ZO‐1) and claudin‐1 expression and tight junction (TJ) opening (33, 34) associated with brain oedema (16). Moreover, high vascular density coupled with increased immunoreactivity to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in neurons and to its ligand VEGF receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2) in cerebral endothelial cells, has been described in old mdx mice (32).

Generalized hypoxia has been reported in DMD, with hypoventilation and resting hypercapnia (4), suggesting that the brain abnormalities might be related to a reduction in cerebral oxygenation.

Hypoxia inducible factor‐1 (HIF‐1) is a transcription factor which is selectively stabilized and activated in a hypoxic condition, and which coordinates the adaptive response of tissues to hypoxia (44, 49). Functionally, HIF‐1 exists as an αβ heterodimer, whose activation is dependent upon the stabilization of the oxygen‐sensitive degradation domain of the α‐subunit by the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway (17).

The HIF‐1 target gene encodes proteins involved in angiogenesis and vascular remodeling, such as VEGF (11). For example, up‐regulation of VEGF has been detected in the brain of mice and rats exposed to hypoxia (10, 21) coupled to HIF1‐α expression. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that hypoxia induces ZO‐1 tyrosine phosphorylation and increases vascular permeability (13).

To date, there have been no reports of HIF‐1 expression in DMD or mdx brain, nor its relation with VEGF and its receptor.

To this purpose, we studied HIF‐1α expression in the brain of younger mdx mice (5 months old) and in controls by immunocytochemistry and by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR), and correlated it with VEGF and VEGFR‐2 expression, evaluated by immunocytochemistry, Western blot and RT‐PCR. Moreover, in order to establish a relationship between VEGF and TJ‐associated proteins in mdx mouse, we analyzed ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 content and expression by Western blot and immunofluorescence, as well as the ZO‐1 phosphorylation state. Finally, in order to clarify HIF‐1α cytochemical expression, we studied its co‐localization by dual immunofluorescence in astrocytes marked with the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) protein.

Results demonstrate, for the first time, that HIF‐1α activation occurs in the perivascular astrocytes and neurons of the mdx brain and that it is coupled with an increase in VEGF and VEGFR‐2 expression and with a modification in the pattern of expression of ZO‐1 and claudin‐1. Finally, the mdx ZO‐1 protein showed a reduction content and enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation.

Overall, these data suggest that HIF‐1α activation in the brain of dystrophic mouse might be responsible, in part, both for BBB opening, through a reduction in ZO‐1 and up‐regulation of its phosphorylation, and angiogenesis increase, through an up‐regulation in VEGF and VEGFR‐2 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. Ten female mdx (C57BL10nSCSn mdx; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and five control mice aged 5 months (C57BL10ScSn) were killed by cervical dislocation and their brains were removed. Small pieces of brain cortex were fixed in a modified acetate‐free Bouin fluid or in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for immunohistochemical investigation. In addition, some brains were coated with OCT mounting media and frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen for immunofluorescence.

HIF‐1α, VEGF, VEGFR‐2 immunohistochemistry. 5 µm histological sections collected on poly‐L‐lysine coated slides (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) were deparaffinized and stained with a three‐layer avidin‐biotin‐immunoperoxidase technique. The sections were rehydrated in a xylene‐graded alcohol scale and then rinsed for 10 minutes in 0.1 M phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). The sections were treated with 0.1% trypsin (Sigma) in CaCl2 0.01 M for 30 minutes at room temperature and then exposed to anti‐VEGF‐A, anti‐VEGFR‐2 and anti‐HIF‐1α primary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted 1:100 in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) overnight at 4°C. The sections were then incubated with biotinylated swine anti‐rabbit Ig (Dako, Milan, Italy) diluted 1:300 in RPMI‐1640 supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated FCS for 15 minutes at room temperature, and streptavidin‐peroxidase conjugate (Vector, Burlingame, USA) diluted 1:250 in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature.

Immunodetection was performed in 0.05 M acetate buffer pH 5.1, 0.02% 3‐amino‐9‐ethylcarbazole grade II (Sigma), and 0.05% H2O2 for 20 minutes at room temperature. Afterwards, the sections were washed in the same buffer and counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin number 2 (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA), and mounted in buffered glycerin. A preimmune rabbit serum (Dako) replacing the primary antibody served as a negative control.

Dual GFAP—HIF‐1α and dual vimentin HIF‐1α immunofluorescence. 7 µm thick cryosectioned samples were utilized. The sections were allowed to thaw at room temperature for 30 minutes and then fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes. Following fixation, the sections were placed in PBS for 5 minutes and blocked in 3% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.2% gelatin in PBS for 30 minutes. For GFAP‐HIF‐1α co‐localization, primary antibodies—mouse anti‐GFAP (Santa Cruz) and rabbit anti‐HIF‐1α—diluted 1:1 for GFAP and 1:10 for HIF‐1α in PBS‐Gelatin for 1 h were used. For vimentin‐HIF‐1α co‐localization, primary antibodies—mouse anti‐vimentin (Dako) and rabbit anti‐HIF‐1α—diluted 1:100 for vimentin and 1:10 for HIF‐1α in PBS‐Gelatin for 1 h were used. After 3 × 5 minutes washings in PBS‐Gelatin, the sections were incubated with FITC‐coupled goat anti‐mouse and CY3‐coupled goat anti‐rabbit and diluted 1:50 and 1:200, respectively, in PBS‐Gelatin for 1 h for GFAP‐HIF‐1α co‐localization and with FITC coupled goat anti‐rabbit and CY3‐coupled goat anti‐mouse for vimentin‐HIF‐1α co‐localization. Preimmune mouse and rabbit sera (Dako) replacing the primary antibodies served as a negative control. Sections were then washed and examined with an Olympus photomicroscope (Milan, Italy) equipped for epifluorescence, and digital images were obtained with a cooled CCD camera (Princeton Instruments, Princeton, NJ, USA).

ZO‐1 and Claudin‐1 immunofluorescence. 7 µm thick cryosectioned samples were treated as previously described. After fixation, washing with PBS, and blocking in 3% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.2% gelatin in PBS for 30 minutes, the sections were incubated with primary antibody (rabbit anti‐claudin‐1) (Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA), at a concentration of 30 µg/mL in PBS‐gelatin and rat anti‐ZO‐1 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) (1:200) in PBS‐Gelatin for 1 h. After 3 × 5 minutes washings in PBS‐Gelatin, the sections were incubated with CY3‐coupled goat anti‐rabbit and FITC‐coupled goat anti‐rat antibodies diluted 1:200 and 1:50, respectively, in PBS‐Gelatin for 1 h. Sections were then washed and examined with an Olympus photomicroscope, as described above.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation. Brains of mdx and control mice were homogenized using a Polytron apparatus in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 1% Triton X‐100, 1% NP‐40, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM NaV04, 10 mM NaF and protease inhibitors. Homogenates were centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 minutes and the protein concentrations of supernatant were determined using the detergent compatible Bio‐Rad DC protein assay (BIO‐RAD Laboratories, CA, USA). For immunoblotting, 60 µg/lane of protein extract were solubilized in Laemmli buffer, boiled at 90°C for 5 minutes and resolved on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel and the proteins were electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, UK). Blots were blocked with TBS‐Tween blocking buffer containing 5% non‐fat dry milk for 1 h and incubated for 2 h with the primary antibodies rabbit anti‐VEGF and rabbit anti‐VEGFR‐2 (Santa Cruz) diluted 1:500, rabbit anti‐Claudin‐1 diluted 1:100 (Zymed) and rat anti‐ZO‐1 (Chemicon) diluted 1:500. After four washings with blocking buffer, for VEGF and VEGFR‐2 and Claudin‐1, immunocomplexes were revealed using anti‐rabbit horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer, while peroxidase activity was revealed by chemiluminescence using the ECL system (Amersham Bioscience).

For ZO‐1 detection, the membrane was incubated for 1 h with alkaline phosphatase‐conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) diluted 1:3000 in blocking buffer, washed again and processed for enzyme activity determination by using a 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl‐phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium substrate. VEGF and VEGFR‐2 bands were quantified by scanning and analyzed using Sion Image software (NIH Image analysis). For ZO‐1 immunoprecipitation, 250 µg of protein extract were solubilized in lysis buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C on a roller for mixing with 5 µg of ZO‐1 antibody (Santa Cruz). Then 40 µL of protein G‐Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience) were added and samples were incubated for 4 h at 4°C, pelleted and twice washed with lysis buffer.

Samples were centrifuged for 2 minutes at 13 000 rpm and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 5 minutes and separated on 7% SDS‐polyacrylamide gels. They were then transferred to PVDF membrane and immunoblotting was performed by blocking the membrane with 5% non‐fat dry milk in TBST. Phospho ZO‐1 was detected by blotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA) diluted 1:1000 followed by secondary anti‐mouse IgG antibody linked to horseradish peroxidase and revealed by the chemiluminescence ECL kit (Amersham Bioscience).

RNA extraction and RT‐PCR. Total RNA was extracted from brain of mdx and control mice using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA was reverse‐transcribed by M‐MLV and oligo (dT)18–20 Primer (Invitrogen). Two µL of cDNA were used to amplify, by PCR, a 450 bp fragment using specific primers for VEGFR‐2 (forward 5′‐CAAGCTCAGCACACAGA AAG‐3′; reverse 5′‐GAGTAAAGCCTAT CTCGCTG‐3′), a 479 bp fragment with specific primers for VEGF (forward 5′‐GATGTATCTCTCGCTCTCTC‐3′; reverse 5′‐CTGCTCTAGAGACAAAGACG‐3′) and a 827 bp fragment with specific primers for HIF‐1α (forward 5′‐GAGCTTG CTCATCAGTTGCC‐3′; reverse 5′‐CTG TACTGTCCTGTGGTGAC‐3′) using recombinant Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). Expression levels of VEGF, VEGFR‐2 and HIF‐1α were normalized to those of the housekeeping gene beta‐actin. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The intensity of bands was quantified as arbitrary optical density units using the Scion Image System (based on NIH Image).

RESULTS

Morphology

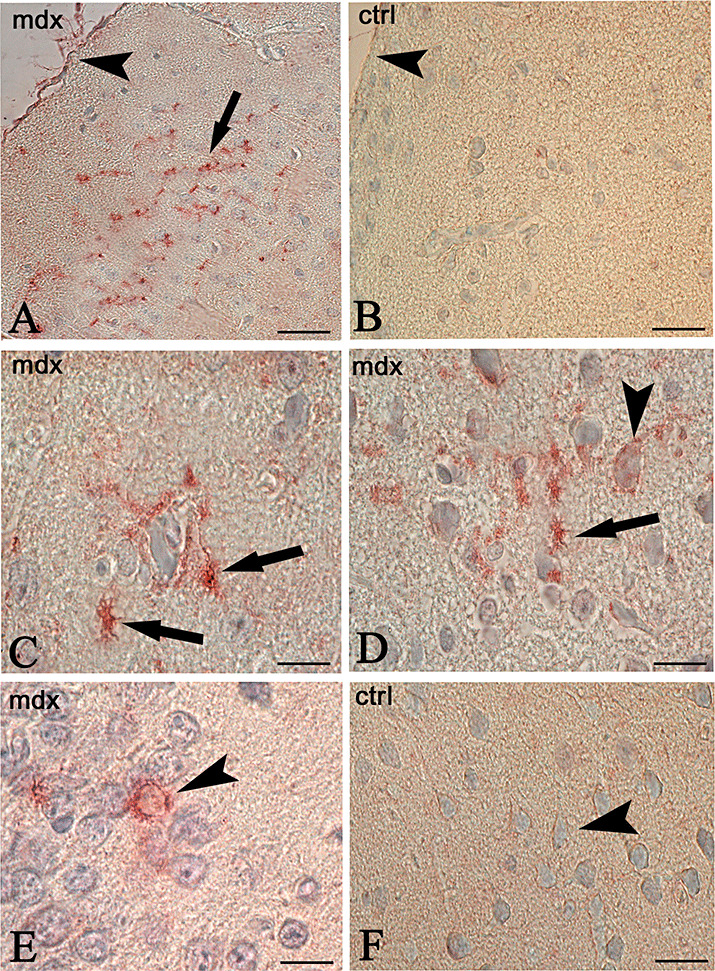

Astrocytes and neurons are positive to HIF‐1α in mdx mice. After the HIF‐1α immunocytochemistry reaction, the mdx mice showed strongly labeled astrocyte bodies and processes. Perivascular glial endfeet, touching the vessel wall, appeared HIF‐1α positive, as did the glia limitans membrane. Neurons of the brain cortex showed intense cytoplasmic and nuclear labeling (Figure 1). By contrast, no HIF‐1α staining was present in the brain of the control mice.

Figure 1.

Immunocytochemistry of hypoxia inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α) in the brain of mdx (A,C,D,E) and control (B,F) mice. Astrocytes scattered in the neuropil (A, arrow), perivascularly arranged (C,D, arrows), glia limitans membrane (A, arrowhead) and neurons (D,E arrowhead) are HIF‐1α strongly labeled in mdx brain. No reaction is detectable in the controls (B,F) where the glia limitans membrane (B, arrowhead), and neurons (F, arrowhead) are unlabeled. Scale bar: 50 µm (A,B); 25 µm (C,D,E,F).

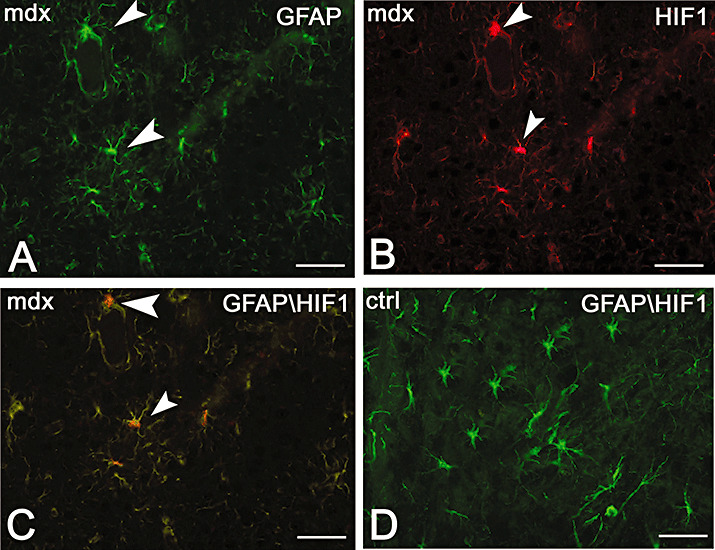

In order to demonstrate the HIF‐1α labeling of astrocytes, dual GFAP‐HIF‐1α immunolocalization was performed. As shown in Figure 2, astrocytes of mdx mice appeared labeled by both anti‐HIF‐1α and GFAP antibodies, with a merged orange staining prevalent in the astrocyte bodies. No co‐localization of both proteins was detected in the control brain, where the astrocyte bodies and processes were strongly stained only by GFAP.

Figure 2.

Dual immunofluorescence of hypoxia inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α, red) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, green) in mdx (A–C) and control (D) mice. Mdx astrocytes show a strong GFAP (A green, arrowhead), HIF‐1α (B red, arrowhead) and both GFAP and HIF‐1α (C orange, arrowhead) expression. No HIF‐1α expression is found in the control (D), where the astrocytes are only GFAP labeled. Scale bar: 25 µm.

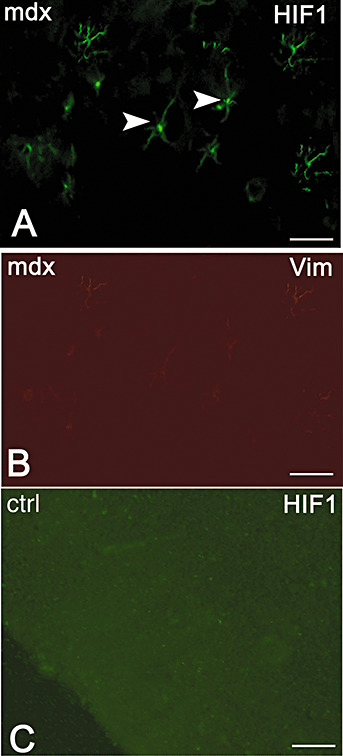

In order to demonstrate if astrocytes expressing HIF‐1α in the mdx brain have a maturational delay with persistence of immature intermediate filaments, dual vimentin‐HIF‐1α immunolocalization was performed. As shown in Figure 3, astrocytes of mdx mice appeared HIF‐1α labeled but any vimentin fluorescence signal was detectable.

Figure 3.

Dual immunofluorescence of hypoxia inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α, green) and vimentin (red) in mdx (A,B) and control (C) mice. Mdx astrocytes show HIF‐1α labeling (A green, arrowhead), while no vimentin expression is found in the mdx (B) and in the control (C), where the astrocytes are also HIF‐1α negative. Scale bar: 25 µm.

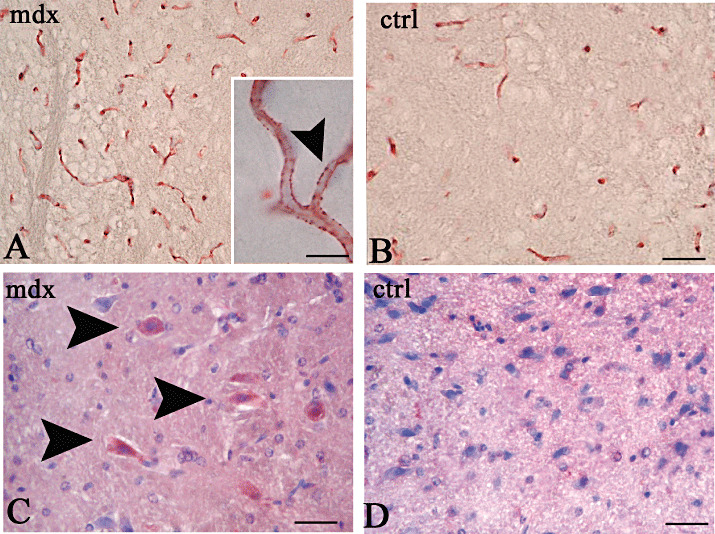

Neurons and vessels are positive to VEGF/VEGFR‐2 in mdx mice. Mdx brain showed cortical neurons that were intensely positive to VEGF, whereas no staining was detectable in controls. Moreover, numerous VEGFR‐2‐labeled dotted vessels were present in the mdx brain as compared with control ones, where they appeared only faintly labeled (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Immunocytochemistry of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2, A,B) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, C,D) in the brain of mdx (A,C) and control (B,D) mice. Numerous VEGFR‐2 labeled vessels (A) and VEGF cortical neurons (C, arrowheads) are recognizable in mdx brain, compared with controls (B,D) where a few vessels are faintly VEGFR‐2 labeled (B) and no VEGF stained neurons are present (D). Note in A, (inset, arrowhead) a dotted VEGFR‐2 staining of mdx vessels. Scale bar: 50 µm (A,B); 10 µm (A, inset), 25 µm (C,D).

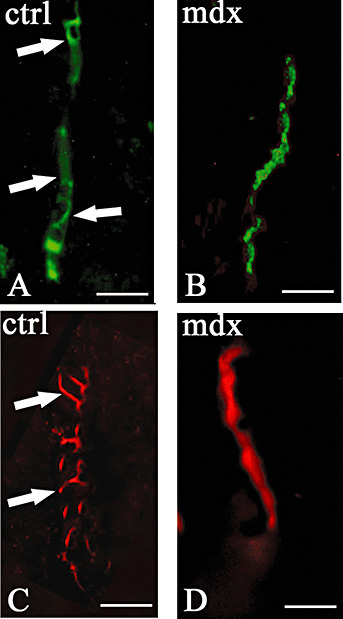

ZO‐1 and Claudin‐1 TJ proteins change their expression and distribution in mdx mice. As shown in Figure 5, after ZO‐1 immunolabeling, the mdx brain showed positivity only in the microvessels, whereas no labeling was observed in the neurons and neuropile. Furthermore, the pattern of expression of ZO‐1 was modified in mdx brain, where it was diffuse and continuous along the luminal vessels, whereas in the controls it was banded and discontinuous. Similarly, after the claudin‐1 immunoreaction, the mdx vessels showed continuous luminal labeling, while the control vessels displayed a dotted immunofluorescent signal (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Zonula occludens‐1 (ZO‐1) and Claudin‐1 immunofluorescence in control (A,C) and mdx (B,D) mice. Banded expression of ZO‐1 (green) and claudin‐1 (red) in control vessel (A,C arrows), and diffuse vascular expression of both proteins in mdx vessels (B,D). Scale bar: 12.5 µm.

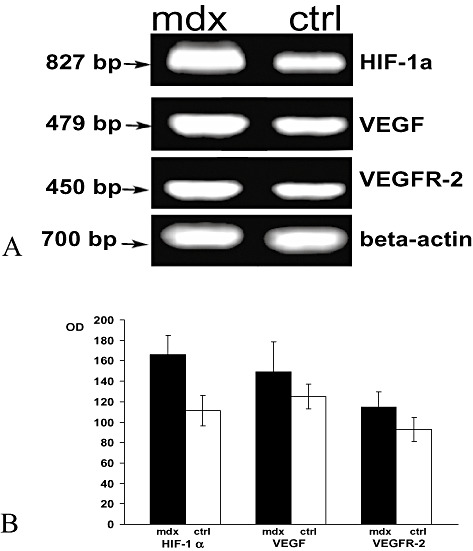

Biochemistry. Analysis of HIF‐1α mRNA levels by RT‐PCR showed a significant increase in expression in mdx brain compared with the control, as shown in Figure 6A. Densitometric analysis confirmed a significant increase of 34% (n = 6, P < 0.001) in mdx brain as compared with the control (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Analysis of hypoxia inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2) mRNA level in brain of mdx and control (ctrl) mice. A. Semiquantitative RT‐PCR analysis shows enhanced HIF‐1α, VEGF and VEGFR‐2 mRNA levels (bp) in mdx brain as compared with the control. The position of the beta‐actin mRNA marker (700 bp) is shown. B. Densitometric analysis of the bands revealed a significant increase in HIF‐1α, VEGF and VEGFR‐2 compared with the controls (166 ± 19.3 vs. 112 ± 15, P < 0.001; 149.5 ± 29 vs. 125 ± 12, P < 0.05; 114.7 ± 14.7 vs. 93 ± 12, P < 0.01). The error band represents the standard deviation of ten experiments. OD = optical density.

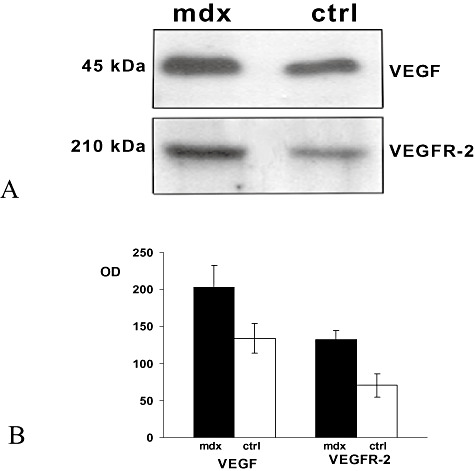

Immunoblotting analysis of VEGF and VEGFR‐2 proteins in mdx brain homogenates showed higher expression of both proteins than in the control (Figure 7A). Densitometric analysis confirmed that VEGF and VEGFR‐2 increased by 34.5% and 46% (n = 10, P < 0.001) compared with the control (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Immunoblotting analysis vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 (VEGFR‐2) protein expression in brain homogenates of mdx and control (ctrl) mice. A. 60 µg of total protein extract was run on a reducing SDS‐PAGE gel and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibody raised against VEGF and a polyclonal antibody raised against VEGFR‐2 respectively. B. Quantification of VEGF and VEGFR‐2 expression after Western‐blot analysis. The histograms show a significant increase in VEGF and VEGFR‐2 in mdx brain compared with the control (203 ± 29 vs. 133.8 ± 20, P < 0.0001; 132.2 ± 12.4 vs. 70.5 ± 15.8, P < 0.0001). The error band represents the standard deviation of ten experiments. OD = optical density.

In parallel with the rise in VEGF and VEGFR‐2 protein in mdx brain, analysis of the mdx gene’s activities by RT‐PCR showed higher mRNA expression in the dystrophic brain than in the control (Figure 6A). Densitometric analysis confirmed a significant increase in both mdx VEGF and VEGFR‐2 mRNA (n = 10, P < 0.05; n = 10, P < 0.001) in mdx brain compared with the control (Figure 6B).

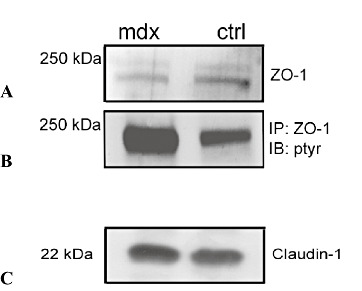

Immunoblotting analysis of ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 protein expression in mdx brain homogenates showed a reduction in ZO‐1 content compared with the control, while no difference in claudin‐1 content was detected (Figure 8A–C).

Figure 8.

Immunoblotting analysis of zonula occludens‐1 (ZO‐1) and Claudin‐1 protein expression (A,C) and immunoblotting precipitation of ZO‐1 (B) in brain homogenates of mdx and control mice. A,C. 60 µg of total protein extract was run on a reducing SDS‐PAGE gel and blotted to a polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membrane. B. 250 µg of brain proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation, using anti‐ZO‐1 antibody and the precipitate was analyzed by Western blot with a polyclonal anti‐phosphotyrosine antibody. A reduction in ZO‐1 content (A) and a ZO‐1 up‐phosphorylation (B) in mdx brain, as compared with the control, are recognizable; no difference in claudin‐1 content (C) is detectable. Abbreviations: ctrl = control; IP = immunoprecipitate; IB : ptyr = immunoblotting : phosphotyrosine.

To evaluate whether the mdx ZO‐1 immunocytochemical dislocation can be related to ZO‐1 tyrosine phosphorylation, ZO‐1 immunoblotting precipitation experiments were carried out. Results showed a strong increase in ZO‐1 phosphorylation in mdx brain as compared with the control (Figure 8B).

DISCUSSION

In previous studies in the brains of old mdx mice, we have shown an increased angiogenesis coupled with alterations of the BBB, enhancement in vascular permeability and immuno‐cytochemical overexpression of VEGF and VEGFR‐2 in neurons and endothelial cells (32, 33).

Here, for the first time, we demonstrate that in the brain of younger mdx mice HIF‐1α is activated in astrocytes and neurons, VEGF and VEGFR‐2 mRNA and proteins are overexpressed and the expression patterns of ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 TJ proteins are modified. Moreover, we found that this TJ protein structural rearrangement is correlated with a biochemical decrease in ZO‐1 content and an increase in its phosphorylation.

Pre‐natal expression of VEGF, VEGFR‐2, HIF‐1α and ZO‐1 during normal mouse brain development. Breier et al (5) demonstrated that VEGF mRNA is expressed in the ventricular layer of the developing neuroectoderm in 17‐day mouse embryos, while VEGFR‐2 is highly expressed in the perineural vascular plexus starting from day 11.5 (29).

Lee et al (22) showed in brain of 13.5 mouse embryos a strong immunoreactivity to HIF1‐α and VEGF and their co‐localization with hypoxic regions.

A faint‐spot‐like staining of ZO‐1 began to be recognizable in brain vessels of 15 day mouse embryos, parallel to BBB development (31). No data are available concerning claudin‐1 expression during mouse brain development.

Endothelial cells of mdx brain are characterized by an overexpression of VEGFR‐2 and by a peculiar pattern of expression of ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 TJ proteins. Our results demonstrate that numerous vessels immunoreactive to VEGFR‐2 are recognizable in mdx brain, as compared with control ones. These data confirm our previous study showing that in the brain of mdx mouse there is an increased vascular density which is correlated with an increased immunoreactivity of endothelial cells to VEGFR‐2 (32). Moreover, the pattern of expression of ZO‐1 in mdx brain microvessels is diffuse and continuous, whereas in controls, it banded and discontinuous. Mdx microvessels show a continuous luminal immunoreactivity to claudin‐1, while controls display a dotted signal. These data, obtained in younger mdx mice, confirm our previously published evidence obtained in old mdx mice, demonstrating that TJ alterations in mdx mice endothelial cells are associated with altered BBB permeability (33, 34). Moreover, this study demonstrates for the first time, decreased ZO‐1 protein content and increased phosphorylation.

HIF‐1α is up‐regulated in perivascular glial cells and neurons in mdx brain. HIF‐1 is a transcription factor, composed of two subunits, one constitutively (HIF‐1β), and one inducibly expressed (HIF‐1α) and selectively stabilized and activated in a hypoxic condition as the expression of an adaptive response of tissues to hypoxia (49).

In DMD, the absence of dystrophin, an actin‐binding protein linking muscle‐specific membrane proteins to actin filaments in the myofibrils (45), is often associated with respiratory failure leading to systemic hypoxia (4).

Increased HIF‐1α expression occurs in several organs, including the brain of mice and rats subjected to systemic hypoxia (51). In different cell types, such as neurons, astrocytes and ependymal cells, HIF‐1α is up‐regulated after CNS injury in response to ischemia and chronic hypoxia (10, 18).

In the present study, we have demonstrated an immunoreactivity to HIF‐1α in the perivascular astrocytes and neurons of mdx brain, and we have identified a large population of astrocytes co‐expressing both HIF‐1α and GFAP in the mdx cortex. In this sense, the up‐regulation of HIF‐1α in mdx brain reported in this study might be the consequence of a hypoxic condition occurring in this pathological condition (4).

HIF‐1α up‐regulation is coupled with VEGF/VEGFR‐2 overexpression in mdx brain. VEGF is a potent angiogenic cytokine, which triggers angiogenesis interacting with VEGFR‐2, expressed on the endothelial cells (35, 42, 43). VEGF and VEGFR‐2 are highly expressed during embryonic brain development and are down‐regulated in adult vasculature (5, 6, 37, 38), while an up‐regulation has been reported in pathological conditions associated with cerebrovascular hypoxia and ischemia (20, 39, 40). Angiogenesis can be interpreted as a compensatory mechanism, where the expression of VEGF leads to increased vascularization and enhanced partial oxygen pressure. In fact, up‐regulation of VEGF has been detected in the brain of mice and rats exposed to hypoxia (10, 21) coupled to HIF‐1α expression. Coexpression of VEGF and HIF‐1 mRNA has been described in activated astrocytes and neurons in rat spinal cord after radiation injury and in mouse brain after ischemia (9, 26, 30, 36). High VEGF expression, as well as a particular susceptibility to hypoxia, has been demonstrated in mdx cortical neurons (9, 27, 28, 32).

HIF‐1 target genes encode proteins involved in angiogenesis, such as VEGF (11), and evidence that VEGF is activated by HIF‐1 is provided in studies showing a spatio‐temporal co‐localization of HIF‐1 and VEGF in the developing mouse embryo (22). Moreover, both HIF‐1α and hypoxic cells also up‐regulate VEGFR (25, 48).

Our results demonstrate that VEGF and VEGFR‐2 are up‐regulated in the mdx brain, at both transcriptional and translational levels, in parallel with enhanced HIF‐1 mRNA activation in astrocytes and neurons, suggesting the existence of a paracrine loop activated by hypoxia and involving HIF‐1α activation in astrocytes and neurons which, in turn, stimulate VEGF/VEGFR‐2 gene expression, leading to compensatory cerebral angiogenesis.

HIF‐1α up‐regulation is coupled with increased ZO‐1 phosphorylation in mdx brain. ZO‐1 is a phosphoprotein associated with other integral proteins of the endothelial junctional membranes, including claudin‐1 (3, 12), which is directly connected with the PDZ domain of ZO‐1, linking the complex to a cellular scaffold (47). Changes to the pattern of ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 expression correlate with BBB damage, involving loss of specific cellular polarity, following alterations in cell–cell contact (15, 23) and modifications to the ZO‐1 phosphorylation state (41).

In this study, we found that in younger mdx mice, in accordance with previous results obtained in old mdx mice (33), a rearrangement in the pattern of expression of the endothelial TJs ZO‐1 and claudin‐1 occurs. Moreover, we demonstrated that ZO‐1 protein content decreases, while its phosphorylation degree is enhanced.

Data from literature indicate that hypoxia increases cerebral vascular permeability through alterations to the TJ proteins (13, 14, 24, 52) and that increased HIF‐1α expression is associated with loss/disassembly of occludin and ZO‐1, and a decrease in endothelial cortical actin (53). Moreover, HIF‐1 regulates VEGF expression by a mechanism directly involving HIF1‐VEGF promoter (19) and VEGF controls vascular permeability through ZO‐1 tyrosine phosphorylation (2, 13, 50).

Our data suggest that the increase in ZO‐1 tyrosine phosphorylation in mdx mice is involved in regulating endothelial permeability mediated by hypoxia and VEGF. In turn, the enhanced phosphorylation of ZO‐1 could be responsible for its cellular degradation, explaining the reduction in ZO‐1 protein content and the dislocation of ZO‐1 from a junctional level with a consequent redistribution of other TJ proteins, such as claudin‐1.

Overall, this study demonstrates major involvement of the endothelial cells, as compared with the astrocytes, in the alterations of the BBB occurring in mdx mice brain. In fact, our data indicate that a hypoxic condition occurs in the brain of dystrophic mice which firstly induces HIF‐1α activation in astrocytes and neurons. This activation, through an up‐regulation of VEGF in neurons and VEGFR‐2 and a decreased expression of ZO‐1 protein and enhancement of its phosphorylation in endothelial cells, is responsible for an increase in both angiogenesis and vascular permeability affecting endothelial cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (Regional Funds), Milan, Associazione Italiana per la Lotta al Neuroblastoma, Genoa, MIUR (FIRB2001; PRIN 2005, Project Carso 72/2 and local Fund), Rome, and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Puglia, Bari, Italy. The authors would also like to thank Anthony Green for revising the text prior to publication.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson JL, Head SI, Rae C, Morley JW (2002) Review. Brain function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Brain 125:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Hollinger LA, Wolpert EB, Gardner TW (1999) Vascular endothelial growth factor induces rapid phosphorylation of tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occludens 1. A potential mechanism for vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy and tumors. J Biol Chem 274:23463–23467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balda MS, Gonzalez‐Mariscal L, Contreras RG, Macias‐Silva M, Torres‐Marquez ME, Garcia‐Sainz JA, Cereijido M (1991) Assembly and sealing of tight junctions: possible participation of G‐proteins, phospholipase C, protein kinase C and calmodulin. J Membr Biol 122:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baydur A, Gilgott I, Trentice W, Carlson M, Fisher DA (1990) Decline in respiratory function and experience with long term assisted ventilation in advanced Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. Chest 97:884–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breier G, Albrecht U, Sterrer S, Risau W (1992) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor during embryonic angiogenesis and endothelial cell differentiation. Development 114:521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breier G, Clauss M, Risau W (1995) Coordinate expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐1 (Flt‐1) and its ligand suggests a paracrine regulation of murine vascular development. Dev Dyn 204:228–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bulfield G, Siller WG, Wight PA, Moore KJ (1984) X‐chromosome‐linked‐muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 8:1189–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bushby KM, Appleton R, Anderson LV, Welch JL, Kelly P, Gardner‐Medwin D (1995) Deletion status and intellectual impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy D. Dev Med Child Neurol 37:260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carmeliet P, Storkebaum E (2002) Vascular and neuronal effects of VEGF in the nervous system: implications for neurological disorders. Semin Cell Dev Biol 13:39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chavez JC, Agani F, Pichiule P, LaManna JC (2000) Expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1alpha in the brain of rats during chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 89:1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dvorak HF, Brown LF, Detmar M, Dvorak AM (1995) Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor, microvascular hyperpermeability, and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 146:1029–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fanning AS, Jameson BJ, Jesaitis LA, Anderson JM (1998) The tight junction protein ZO‐1 establish a link between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 273:29745–29753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fischer S, Wobben M, Marti HH, Renz D, Schaper W (2002) Hypoxia‐induced hyperpermeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells involves VEGF‐mediated changes in the expression of zonula occludens‐1. Microvasc Res 63:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fleegal MA, Hom S, Borg LK, Davis TP (2005) Activation of PKC modulates blood‐brain barrier endothelial cell permeability changes induced by hypoxia and posthypoxic reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289:H2012–H2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleming TP, Hay MJ (1991) Tissue‐specific control of expression of the tight junction polypeptide ZO‐1 in the mouse early embryo. Development 113:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frigeri A, Nicchia GP, Nico B, Quondamatteo F, Herken R, Roncali L, Svelto M (2001) Aquaporin‐4 deficiency in skeletal muscle and brain of dystrophic mdx‐mice. FASEB J 15:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang LE, Gu J, Schau M, Bunn HF (1998) Regulation of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha is mediated by an O2‐dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7987–7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jin KL, Mao XO, Nagayama T, Goldsmith PC, Greenberg DA (2000) Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1alpha by global ischemia in rat brain. Neuroscience 99:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jung YJ, Isaacs JS, Lee S, Trepel J, Neckers L (2003) IL‐1beta‐mediated up‐regulation of HIF‐1alpha via an NFkappaB/COX‐2 pathway identifies HIF‐1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J 17:2115–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krupinsky J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JP (1994) Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke 25:1794–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuo NT, Benhayon D, Przybylski RJ, Martin RJ, LaManna JC (1999) Prolonged hypoxia increases vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA and protein in adult mouse brain. J Appl Physiol 86:260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee YM, Jeong CH, Koo SY, Son MJ, Song HS, Bae SK, Raleigh JA, Chung HY, Yoo MA, Kim KW (2001) Determination of hypoxic region by hypoxia marker in developing mouse embryos in vivo: a possible signal for vessel development. Dev Dyn 220:175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liebner S, Fischmann A, Rasher G, Duffner F, Grote EG, Kalbacher H, Wolburg H (2000) Claudin‐1 and claudin‐5 expression and tight junction morphology are altered in blood vessels of human glioblastoma multiforme. Acta Neuropathol 100:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mark KS, Davis TP (2002) Cerebral microvascular changes in permeability and tight junctions induced by hypoxia‐reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282:H1485–H1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marti HH, Risau W (1998) Systemic hypoxia changes the organ‐specific distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15809–15814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marti HJ, Bernaudin M, Bellail A, Schoch H, Euler M, Petit E, Risau W (2000) Hypoxia‐induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression precedes neovascularization after cerebral ischemia. Am J Pathol 156:965–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mehler MF (2000) Brain dystrophin, neurogenetics and mental retardation. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 32:277–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mehler MF, Haas KZ, Kessler JA, Stanton PK (1992) Enhanced sensitivity of hippocampal pyramidal neurons from mdx mice to hypoxia‐induced loss of synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:2461–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Millauer B, Wizigmann‐Voos S, Schnrurch H, Martinez R, Moller NPH, Risau W, Ullrich A (1993) High affinity VEGF binding and developmental expression suggest Flk‐1 as a major regulator of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cell 72:835–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mu D, Jiang X, Sheldon RA, Fox CK, Hamrick SE, Vexler ZS, Ferriero DM (2003) Regulation of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha and induction of vascular endothelial growth factor in a rat neonatal stroke model. Neurobiol Dis 14:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nico B, Quondamatteo F, Herjen R, Marzullo A, Corsi P, Bertossi M, Russo G, Ribatti D, Roncali L (1999) Developmental expression of ZO‐1 antigen in the mouse blood‐brain barrier. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 114:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nico B, Corsi P, Vacca A, Roncali L, Ribatti D (2002) Vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 expression in mdx mouse brain. Brain Res 953:12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nico B, Frigeri A, Nicchia GP, Corsi P, Ribatti D, Quondamatteo F, Herken R, Girolamo F, Marzullo A, Svelto M, Roncali L (2003) Severe alterations of endothelial and glial cells in the blood‐brain barrier of dystrophic mdx mice. Glia 42:235–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nico B, Nicchia GP, Frigeri A, Corsi P, Mangieri D, Ribatti D, Svelto M, Roncali L (2004) Altered blood‐brain barrier development in dystrophic MDX mice. Neuroscience 125:921–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nicosia RF, Nicosia SV, Smith M (1994) Vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet‐derived growth factor, and insulin‐like growth factor‐1 promote rat aortic angiogenesis in vitro. Am J Pathol 145:1023–1029. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nordal RA, Nagy A, Pintilie M, Wong CS (2004) Hypoxia and hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 target genes in central nervous system radiation injury: a role for vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin Cancer Res 10:3342–3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ogunshola OO, Stewart WB, Mihalcik V, Solli T, Madri JA, Ment LR (2000) Neuronal VEGF expression correlates with angiogenesis in postnatal developing rat brain. Dev Brain Res 119:139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peters KG, De Vries C, Williams LT (1993) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression during embryogenesis and tissue repair suggests a role in endothelial differentiation and blood vessel growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:8915–8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Risau W (1992) Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential tumour angiogenesis factor in human gliomas in vivo . Nature 359:845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Mennel HD, Risau W (1994) Vascular endothelial growth factor and glioma angiogenesis: coordinated induction of VEGF receptors, distribution of VEGF protein and possible in vivo regulatory mechanisms. Int J Cancer 59:520–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rao RK, Basuroy S, Rao VU, Karnaky KJ Jr, Gupta A (2002) Tyrosine phosphorylation and dissociation of occludin‐ZO‐1 and E‐cadherin‐beta‐catenin complexes from the cytoskeleton by oxidative stress. Biochem J 368:471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Risau W (1997) Mechanism of angiogenesis. Nature 386:671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosenstein JM, Mani N, Silverman WF, Krum JM (1998) Patterns of brain angiogenesis after vascular endothelial growth factor administration in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7086–7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Semenza GL (1998) Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1: master regulator of O2 homeostasis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8:588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tinsley JM, Blake DJ, Zuellig RA, Davies KE (1994) Increasing complexity of the dystrophin‐associated protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:8307–8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tracey I, Dunn JF, Radda GK (1996) Brain metabolism is abnormal in the mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Brain 119:1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M (1999) Structural and signalling molecules come together at tight junctions. Curr Opin Cell Biol 11:628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vasir B, Jonas JC, Steil GM, Hollister‐Lock J, Hasenkamp W, Sharma A, Bonner‐Weir S, Weir GC (2001) Gene expression of VEGF and its receptors Flk‐1/KDR and Flt‐1 in cultured and transplanted rat islets. Transplantation 71:924–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang GL, Jiang BH, Semenza GL (1995) Effect of protein kinase and phosphatase inhibitors on expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 216:669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang Z, Castresana MR, Newman WH (2001) Reactive oxygen and NF‐kappa B in VEGF‐induced migration of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 285:669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wiener CM, Booth G, Semenza GL (1996) In vivo expression of mRNAs encoding hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 225:485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Witt KA, Mark KS, Hom S, Davis TP (2003) Effects of hypoxia‐reoxygenation on rat blood‐brain barrier permeability and tight junctional protein expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285:H2820–H2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Witt KA, Mark KS, Huber J, Davis TP (2005) Hypoxia‐inducible factor and nuclear factor kappa‐B activation in blood‐brain barrier endothelium under hypoxic/reoxygenation stress. J Neurochem 92:203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]