Abstract

Inflammatory processes are a major cause of hypoxic‐ischemic brain damage. The present study focuses on both the cerebral histamine system and mast cells in a model of transient focal ischemia induced by permanent left middle cerebral artery, and homolateral transient common carotid artery occlusion (50 minutes) in the P7 newborn rat. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that ischemia induces histamine (HA) accumulation in the core of the infarct 6–12 h post‐ischemia, and in the penumbra at 24–48 h, although in situ hybridization failed to detect any histidine decarboxylase gene transcripts in these regions. Immunohistochemical co‐localization of HA with the MAP2 marker revealed that HA accumulates in neuronal cells before they degenerate, and is accompanied by a very significant increase in the number of mast cells at 12 h and 48 h of reperfusion. In mast cells, histamine immunoreactivity is detected at 2, 6 and 12 h after ischemia, whereas it disappears at 24 h, when a concomitant degranulation of mast cells is observed. Taken together, these data suggest that the recruitment of cerebral mast cells releasing histamine may contribute to ischemia‐induced neuronal death in the immature brain.

INTRODUCTION

Perinatal hypoxic‐ischemic injury remains a major cause of mortality and morbidity susceptible to generate permanent neurological sequelae (mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy or learning disability) 6, 14, 30. The mechanisms leading to neuronal damage after hypoxia‐ischemia are not completely understood, but many interconnected pathways are involved in the process of brain injury, including production of oxygen‐free radicals, release of excitatory amino acids, intracellular calcium mobilization, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, synthesis of trophic factors and activation of the immuno‐inflammatory system (45).

Using a model of transient focal ischemia performed in the newborn rat 7 days after birth (P7) (38), we demonstrated that an extensive inflammatory reaction progresses for days and weeks, and plays a role in the secondary evolution of injury. Results indicated that microglia/macrophages, T cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes may be involved in the response to ischemia 5, 7, 9. The blood–brain barrier (BBB) impairment followed by gliosis and leukocyte infiltration, provides evidence of a strong local inflammatory response (5). Nevertheless, the pathophysiologic mechanism at the origin of this extensive inflammatory reaction is not known. In this study, we focus on the histaminergic system and mast cells, more particularly because they are abundant in the neonatal brain, and because of their potential immuno‐inflammatory and deleterious activities described in several pathological conditions.

In the brain, the number of mast cells and histamine (HA) content vary considerably during development 11, 12, 49. During embryogenesis, mast cells are detected in the brain within the pia matter and the choroid fissure 10, 26. HA levels are very high at E15 in the rat, and decrease until birth (43). HA neurons take place in the tuberomammillary nucleus around E14‐E16 in the rat, the development of most fibers taking place during the first two postnatal weeks 4, 19, 37. After birth, the number of mast cells greatly increases and then represents the principal source of cerebral HA 15, 26. During the first two postnatal weeks, HA brain levels are maximal and may contribute to rapid postnatal cell proliferation and growth 26, 27, 39. During late postnatal development, the mast cell number decreases, and HA is essentially produced by the neuronal pool (39).

In cerebral ischemia models, mast cell invasion occurs in adult rat thalamus one day after ischemia (21). Mast cell degranulation could contribute to BBB leakage, edema formation, and neutrophil accumulation (42). Several studies, also performed in the adult rat brain, suggest the involvement of HA in ischemia‐induced neurodegenerative processes. Ischemia induces neuronal HA release, and HA alleviates ischemic neuronal damage by H2 receptor activation [for review see (1)].

In neonatal mice (P5), recent studies reveal that HA released by mast cell degranulation, is involved in TGF‐beta1 effects on excitotoxic brain lesions (28). H1‐receptor antagonists and cromoglycate protect tissues against excitotoxicity, thereby suggesting a potential deleterious role of HA in the developing brain (35). Interestingly, mast cell stabilization also limits hypoxic‐ischemic brain damage in P7 rats (22). In addition, HA released from mast cells potentiates N‐methyl‐D‐aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor‐mediated excitotoxicity in embryonic cultured neurons, an effect amplified by acidification of the medium, and which may therefore be involved in neuronal death induced by cerebral ischemia during development (41).

The aim of the present study was to investigate both the HA system and mast cells in a model of transient focal ischemia that produces unilateral cortical injury in the neonatal rat brain (38).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Perinatal ischemia.

All experiments were conducted according to the French and European Community guidelines for the care and use of animals, and tended to minimize the number of animals used as well as their suffering.

Ischemia was performed in 7‐day‐old rats (17–21 g; Janvier, Le Genest‐St‐Isle, France), as previously described (38). Rat pups were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg). Anesthetized rats were positioned on their back and a median incision was made in the neck to expose the left common cartoid artery (CCA). Rats were then placed on the right side, and an oblique skin incision was made between the ear and the eye. After excision of the temporal muscle, the cranial bone was removed from the frontal suture to a level below the zygomatic arch. Then the left middle cerebral artery (MCA), exposed just after its appearance over the rhinal fissure, was coagulated at the inferior level of the cerebral vein. After this procedure, a clip was placed to occlude the left CCA. Rats were then placed in an incubator to avoid hypothermia. After 50 minutes, the clip was removed. Carotid blood flow restoration was verified with the aid of a microscope. Both neck and cranial skin incisions were then closed. During the surgical procedure, external body temperature was measured with an infrared cutaneous thermometer and maintained at 36–36.5°C using a heating pad. Pups were transferred to an incubator (32°C) until recovery, and then returned to their mothers.

Tissue preparation.

Animals were anesthetized with an overdose of pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with 0.9% NaCl (37°C) and 4% 1‐ethyl‐3(3dimethylaminopropyl) ‐ carbodiimide, 0.5% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (4°C) (33). The brains were removed and postfixed in the same solution overnight (4°C). Brains were cryoprotected in 10% sucrose, frozen by immersion in liquid monochlorodifluoromethane and kept at −20°C until use. Brain sections (20 µm) were prepared on a cryostat, thaw‐mounted onto Superfrost slides and kept at −20°C. Some sections were stained with 0.01% toluidine blue (pH 3.8) for mast cells detection, other sections were submitted to Terminal transference dUTP Nick End Labelling (TUNEL) detection.

TUNEL

Brain sections were submitted for fluorescence in situ labeling of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) as evidence of apoptotic cell death (18). Sections were processed for DNA strand breaks using the in situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche, Meylan, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry.

Cryostat sections (bregma −3.60 to −3.80 mm) were first incubated for 30 minutes in 0.1 M PBS containing 5% normal donkey serum and 0.1% tween 20 followed by a 3‐day incubation at 4°C with an antihistamine rabbit antibody (1:10 000, Delichon, Masala, Finland), 1% normal donkey serum, 0.05% tween 20 in 0.1 M PBS. The signals generated by the primary antibody were evidenced by incubation with a biotinylated donkey anti‐rabbit antibody (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK 1:200) at room temperature for 2 h, and the streptavidin‐biotin‐peroxydase complex (ABC Elite, Vector Laboratories, AbCys, Paris, France). Specificity of the obtained immunoreactivity was tested by pre‐absorption of the antiserum with HA‐ovalbumine (0, 10 and 100 µg/ml, overnight at 4°C, Delichon, see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Specificity of the antihistamine immunostaining. Ischemic brain sections were incubated with a polyclonal antihistamine antibody in the absence (A) or presence (B,C) of histamine‐ovalbumine at 10 µg/ml (B) and 100 µg/ml (C). Note that the two concentrations of histamine completely abolished the immunolabeling (core of the infarct, 24 h after ischemia). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Double immunofluorescence was performed to show co‐localization of HA with a neuronal marker (MAP2, microtubule‐associated protein). Briefly, sections were incubated with the anti‐HA antibody as described previously, and visualized with Alexa Fluor 555 anti‐rabbit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA 1:200, 2 h at room temperature). A second incubation of the sections was performed with the mouse anti‐MAP2 (Upstate Biotechnology, NY, USA 1:100, overnight at room temperature), visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 anti‐mouse. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma Aldrich, Fallavier, France) and mounted with mowiol.

In situ hybridization of histidine decarboxylase gene transcripts.

Sections were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes with proteinase K (1 µg/ml), acetylated for 10 minutes (in 0.1 M triethanolamine, pH 8, and 0.25% acetic anhydride) at room temperature, and dehydrated in graded ethanol up to 100%. Hybridization was performed overnight at 55°C in the presence of 4 × 106 dpm of a 33P‐labeled histidine decarboxylase cRNA probe previously described (19), probe in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2XSSC, 1X Denhardt’s solution, 50 mM Tris‐HCl buffer, 0.1% NaPPi, 0.1 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 0.1 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA, and 1 mM EDTA) as previously described (19). Subsequently, the sections were rinsed with 2XSSC for 5 minutes and incubated for 40 minutes at 37°C with RNase A (200 µg/ml). The sections were then extensively washed in SSC, dehydrated in graded ethanol, dried and dipped in a liquid photographic LM1 emulsion (Amersham) for 3 weeks. Dipped sections were then observed with a photomicroscope (Axiophot Zeiss, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

RESULTS

Ischemia‐induced lesions.

Permanent left MCA occlusion associated with transient occlusion of the left CCA produced a reproducible and well‐delineated cortical infarct lesion 48 h following reperfusion (Figure 2A), as previously reported 23, 38. Within the cortical infarct, TUNEL labeling confined to a well‐defined nuclear profile was observed in numerous nuclei in the core (Figure 2B), and in several ones in a so‐called penumbra zone (Figure 2C). The core evolved into a cavity 7 days after recovery (23).

Figure 2.

Histopathological changes of the left cerebral hemisphere after neonatal ischemia in P7 rats. A. Representative cresyl‐violet‐stained coronal brain section, 48 h following ischemia. Note the large ill‐defined pale area corresponding to the infarct (core C; and penumbra P). B,C. Ischemia‐induced cell death in the parietal cortex evidenced by DNA fragmentation and apoptotic bodies using fluorescent TUNEL assay in the core (B) and penumbra (C). Scale bar = 25 µm.

Ischemia‐induced HA accumulation.

In control conditions (sham operated rats), and in non‐ischemic areas, cellular bodies of the forebrain parenchyma did not show any histamine‐like immunoreactivity (HA‐like IR) (Figure 3E). HA‐like IR was only observed in hypothalamic magnocellular neurons (Figure 3H), as well as in choroid plexus and mast cells of the leptomeninges (data not shown). After ischemia, HA‐like IR first appeared in the core of the infarct, and then extended to the penumbra. As soon as 2 h following reperfusion, a faint HA‐like IR occurred in the wall of cortical blood vessels (Figure 3A). HA‐like IR was thereafter observed in many cortical cells localized in the core of the infarct, at 6 h (Figure 3B), and 24 h (Figure 3C) following ischemia. HA‐like IR appeared in the penumbra between 24 h and 48 h post‐ischemia (Figure 3F,G). In superficial cortical layers, phagocytic cells, probably macrophages, presented HA‐like IR at 48 h after ischemia (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Histamine accumulation in the cerebral cortex after neonatal stroke in the P7 rat. Ischemia induced a cortical infarct as shown in the diagram (C, core; P, penumbra). A–D. Histamine‐like immunoreactivity (HA‐like IR) observed in the core of the infarct. A. 2 h after ischemia, HA‐like IR transiently appeared in cortical blood vessels (V) of the ischemic core. B. At 6 h post ischemia, a faint immunostaining occurred in pyramidal‐shaped cortical cells (arrows). C. 24 h after reperfusion, HA‐like IR increased in intensity and was observed within many cells of the core. D. At 48 h, HA‐like IR phagocytic cells (arrow heads) were observed in the superficial cortical layers; blood vessels (v) were not labeled. E. Cortical cells not subjected to ischemia did not show any HA‐like IR. F,G. HA‐like IR in the penumbra at 24 h (F) and 48 h (G) post ischemia. H. HA‐like IR in histaminergic magnocellular neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus. I–K. In situ hybridization of histidine decarboxylase (hdc) gene transcripts did not reveal any signal in the ischemic infarct, neither 6 h (I), nor 24 h (J), following ischemia. K. A mast cell of the pia matter expressing hdc mRNAs. In A,C,D,E,G,I,J, brain tissues were counterstained with hemalun to vizualize cell nuclei. Photographs are representative of three different experiments on each animal. Scale bars represent 25 µm (A,D,F,H), 50 µm (B,C,E,G), 100 µm (I,J) and 10 µm (K).

In situ hybridization analysis did not reveal any histidine decarboxylase gene transcripts in neocortical cells, either at 6 h or at 24 h, following injury (Figure 3I,J). These transcripts were only detected in mast cells of pia matter and choroid fissure (Figure 3K).

In the penumbra, co‐localization studies of HA‐like IR with the MAP2 neuronal marker, revealed that HA‐like IR accumulation occurred in neurons (Figure 4). 48 h post‐ischemia, HA‐like IR was found in neuronal cells just entering in the degenerative process and in edematous neurons of the penumbra (Figure 4E). Note that in degenerating neurons, at the beginning of the process, MAP2 immunostaining resulted in segmental dendritic beading or varicosities, and loss of dendrites 20, 34 (Figure 4B,E). In the core, in degenerative cells showing characteristics of the apoptotic process HA‐like IR and MAP2 immunostaining have disappeared (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Co‐localization of histamine and the neuronal marker MAP2, 48 h after neonatal stroke, in the ipsilateral cortex at the limit core/penumbra (A–E) and in a non‐ischemic zone (F–I). The fluorescent labeling was evidenced with antibodies against histamine (red, A,F), MAP2 (green, B,G), and nuclear marker Hoechst 33342 (blue, D,H). Co‐localization of HA and MAP2 is shown in C and co‐localization of the three markers is shown in E and I. In the ischemic cortex (A–E), labeling demonstrates the co‐localization of histamine‐like immunoreactivity (IR) with MAP2 IR in the penumbra (C,E): in degenerating neurons at the beginning of the degenerative process (double arrow), at the end of dendritic loss (arrow head) and in neurons with edematous aspect (*). Note that in the degenerating neurons, MAP2 IR resulted in segmental dendritic beading or varicosities and loss of dendrites (B). In the core, Histamine‐like IR and MAP2 IR disappeared and neurons presented apoptotic characteristics with condensed chromatin and the presence of apoptotic bodies (arrows, E). In the control zone of the cortex (F–I), Histamine‐like IR was not detected (F) and MAP2 staining revealed dendritic processes and neuronal cell bodies characteristic of healthy neurons (G,I). V: blood vessel. Scale bar = 15 µm.

Ischemia‐induced changes in mast cell number.

In control (ie, non‐ischemic) conditions, numerous mast cells were observed in the pia mater of the P7 neonatal rat brain (Figure 5I). The quantification of mast cells within the choroid fissure located between the hippocampus and thalamus in both hemispheres, confirmed that the number of cerebral mast cells progressively declined between P7 and P14 (182 ± 34 vs. 33 ± 6, Table 1), as previously described 10, 26. After cerebral ischemia, the number of leptomeningeal mast cells was dramatically increased 12 h after the insult, when compared with the number of mast cells found in control conditions (425 ± 73 vs. 182 ± 34, P < 0.01, Table 1). This increase was followed by a very significant decrease 24 h after ischemia (63 ± 7 vs. 166 ± 25, P < 0.01). Nevertheless, at 48 h and 72 h of reperfusion, the number of mast cells increased again (Table 1). These increases were statistically significant, when compared with the number of mast cell observed in control conditions at the corresponding stages of development (282 ± 65 vs. 119 ± 9 at P9; 126 ± 24 vs. 70 ± 8 at P10, P < 0.05). Seven days after ischemia, the numbers of mast cell in ischemic and control brains were not significantly different (55 ± 15 vs. 33 ± 6, Table 1).

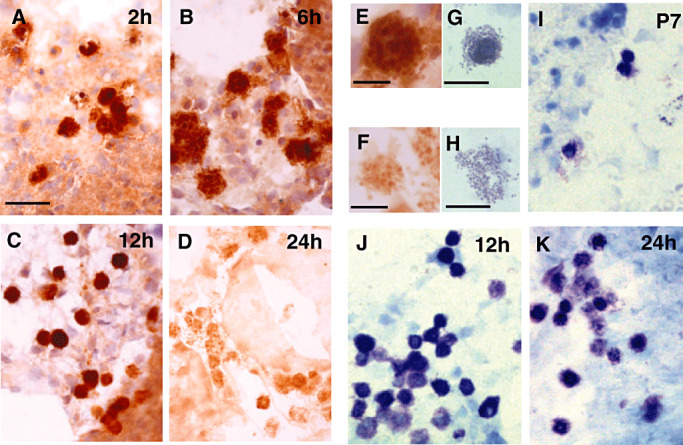

Figure 5.

Mast cells of the choroïd fissure after neonatal stroke. A–F. Mast cells containing histamine immunostaining were observed as early as 2 h (A), 6 h (B,E), 12 h (C) and 24 h (D,F) after ischemia. The marked decrease in histamine immunolabeling observed at 24 h (D,F) suggests that mast cells have degranulated. G–K. Acidic toluidine blue staining of mast cells in P7 control (I) and ischemic (J,K) rat brains. Note the presence at 24 h, of a great number of degranulating mast cells (K), at different states of mast cell degranulation: (G) mast cells poorly degranulated, (H) mast cell highly degranulated. Scale bars represent 40 µm (A–D,I–K), 10 µm (E,F) and 20 µm (G,H).

Table 1.

Quantification of mast cells after acidic toluidine blue staining.

| Control (n = 3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P14 | |

| Mast cells | 182 ± 34 | 166 ± 25 | 119 ± 9 | 70 ± 8 | 33 ± 6 |

| Degranulated mast cells (%) | 33 ± 4 | 33 ± 4 | 22 ± 6 | 24 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 |

| Ischemia (n = 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 7 days | |

| Mast cells | 425 ± 73† | 63 ± 7‡, § | 282 ± 65* | 126 ± 24* | 55 ± 15 |

| Degranulated mast cells (%) | 18 ± 4 | 48 ± 8‡ | 21 ± 7* | 39 ± 11*, ¶ | 14 ± 2 |

P < 0.05 vs. control P9 and P10.

P < 0.01 vs. control at P7.

P < 0.01 vs. ischemia at 12 and 48 h.

P < 0.05 vs. ischemia at 72 h.

P < 0.05 vs. ischemia at 12 h.

Concerning the HA content of mast cells, we did not observe any apparent change of HA‐like IR 2, 6 and 12 h after ischemia (Figure 5A–C,E). However, a dramatic decrease of immunological staining was evidenced 24 h after ischemia (Figure 5D,F). This decrease in HA‐like IR was associated with a massive degranulation of mast cells (Figure 5G,H), as shown by the increased percentage of degranulated mast cells found by acidic toluidine blue staining of brain sections (18 ± 4% at 12 h vs. 48 ± 8% at 24 h post‐ischemia, P < 0.01, Table 1).

DISCUSSION

This study shows for the first time, that ischemia induces HA accumulation in neurons of the neonatal brain. This HA accumulation is restricted to the infarcted regions (core and penumbra), and is observed before the occurrence of cell death. Neuronal HA accumulation is accompanied by a dramatic increased number of mast cells in pia matter tissues as well as by mast cell degranulation. We previously suggested that such immuno‐inflammtory phenomena could significantly contribute to ischemia‐induced neuronal death in the immature brain 5, 7.

In this study, HA was detected using a single technique (immunohistochemistry), which could be criticized. However, the antibody used has already been validated by other teams 31, 32, 33 and its specificity was confirmed in our experimental conditions by the abolition of immunoreactivity after pre‐absorption of the antibody with HA‐ovalbumin (Figure 1).

The HA that we observed in ischemic cerebral tissues, was not synthesized by ischemic cells themselves, as evidenced by in situ hybridization study, which failed to detect the presence of histidine decarboxylase gene transcripts in the injured territory. Our data therefore indicate that HA present within ischemic neurons, emanates from other extracellular sources. Among the latter, HA may originate from blood, mast cells and/or histaminergic neurons.

The early detection of HA‐like IR in the walls of cerebral vessels, observed 2 h after reperfusion, argues for a peripheral origin of HA, which would enter the brain during blood reperfusion. HA and HDC are not detected in cerebral endothelial cells of the adult rat brain (25). Although HA present in circulating blood does not cross the BBB in physiological conditions, it might enter the ischemic brain because of the BBB disruption induced by the ischemic insult (5). However, additional sources of HA probably contribute to its accumulation in ischemic neurons, because vascular HA‐like IR was only transiently observed, and vascular walls were no longer labeled 6 h after the reperfusion.

HA might also accumulate in vascular walls and in neuronal cells, after its release by histaminergic projections, originating from the tuberomammillary nuclei of posterior hypothalamus, and innervating neurons and capillaries present in the infarct region. Indeed, at the developmental stages studied, HA neurons are already present in the hypothalamus (as shown in Figure 3), and HA fibers are widely distributed (4) as in the adult brain 13, 32. Thus, ischemia, which induces ATP depletion and depolarization, would lead to a massive neuronal HA release from histaminergic terminals present in the telencephalic ischemic areas. Consistent with this hypothesis, ischemia induces a long lasting HA release from histaminergic nerve endings in the adult rat brain submitted to MCA occlusion 2, 3. We failed to detect any change in HA and HDC labeling at various set times following ischemia in the tuberomammillary nuclei (data not shown). However, this may not exclude that HA accumulated in the ischemic zone emanates from HA neurons. Indeed, the long lasting increase in HA neuron activity induced by ischemia is expected to be accompanied by an enhancement of HA turn over, rather than changes in HA‐like IR or HDC mRNA expression within tuberomammillary cell bodies.

In addition to blood and histaminergic neurons, mast cells may also constitute a major source of the HA accumulation observed in the ischemic neonatal brain. Numerous mast cells are present in neonatal brain 10, 26. We confirm here between P7 and P14 that they are localized in the external pia matter, and abundant in the choroid fissure surrounding the diencephalon, the fimbria of hippocampus and within the choroid plexus. We show that ischemia induces a dramatic increase in the number of cerebral mast cells 12 h after the insult. In addition, mast cells have massively degranulated 24 h after ischemia, a time point at which HA‐like IR was very high in the neurons of the infarct zone. These data are in agreement with recent observations made in a model of cerebral ischemia performed in the adult rat, in which the number of mast cells increased in the middle aspect of the thalamus, 1 day after the insult (21). Altogether, our data indicate that HA would accumulate in the lesion after its release by pia matter mast cells and its subsequent diffusion into the cerebral parenchyma. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the fact that we did not detect any HA‐like IR in the adult ischemic rodent brain (data not shown), which contains less mast cells than the developing brain 10, 26.

In the ischemic neonatal brain, the high levels of HA released from mast cells by the neonatal stroke, therefore add to the high HA levels found in neonatal brain at birth and during the first postnatal weeks 27, 36, 40, probably reaching high enough concentrations to accumulate within ischemic neurons.

How extracellular HA is transported into these ischemic neurons is unclear. In contrast to other monoaminergic systems, no clear evidence for a high‐affinity uptake system for HA in the brain could be found (40). Nevertheless, our observation that HA‐like IR was detected with the MAP2 marker, only in remaining healthy neurons, or neurons at the first step of degeneration, with its presence being detectable only several hours after ischemia, might suggest that HA enters the cells by some nonspecific and low‐affinity uptake system. The polyspecific organic cation transporters OCT2 and OCT3 may be involved (24). OCT2, a “background” transporter involved in the removal of monoamine neurotransmitters, is expressed in neurons of various rat and human brain areas and mediates low affinity transport of HA as well as catecholamines and serotonin 8, 47. HA is also a good substrate for OCT3. This transporter was initially identified as the major component of the extraneuronal monoamine transport system (EMT or uptake 2) (16). However, in situ hybridization revealed that OCT3 is widely distributed in different brain regions, with a prominent neuronal expression detected in cerebral cortex (46). OCT2 and OCT3 might therefore account, at least partly, for the uptake of neuronal HA induced by ischemia. Such an uptake of HA has already been hypothesized to explain the HA‐like IR observed in the absence of HDC gene transcripts, in various neuronal populations, such as neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the adult brain (29), or neurons of the raphe nucleus, autonomic ganglia, sensory neurons or motoneurons, during embryogenesis 17, 19, 31, 44.

The effects of HA, if any, within ischemic neurons remain unknown. HA accumulated within neurons may be directly involved in ischemic symptoms. In agreement with such a deleterious role of HA and mast cells in ischemia‐induced lesions, H1 antagonists and cromoglycate have been shown to protect developing tissues against excitotoxicity in P5 mice (35), a preponderant mechanism responsible of ischemic lesions. Cromoglycate stabilized brain mast cells and reduced their degranulation, reduced migration into ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres, and reduced neuronal death after hypoxic‐ischemia injury in P7 rats (22). In addition, HA released from mast cells potentiates NMDA receptor‐mediated excitotoxicity in embryonic cultured neurons (41). A deleterious effect of HA in ischemia might also be mediated by activation of H4 receptors. The H4 receptor is expressed primarily on cells involved in inflammation and immune response. It has effects on chemotaxis and cytokine production of mast cells, eosinophils, dendritic cells, and T cells, and H4‐receptor antagonists demonstrate efficacy as anti‐inflammatory agents in vivo (48).

Alternatively, HA may be involved in a compensatory manner to attenuate ischemic symptoms. Such a protective role of HA in the neonatal brain is supported by the beneficial effects of HA in adult ischemia models [for review see (1)]. Pretreatment with H2‐receptor antagonists, or impairment of HA neurotransmission, aggravates ischemic neuronal damage, whereas post‐ischemic loading with L‐histidine, the aminoacid precursor of HA biosynthesis, alleviates brain infarction, and delayed neuronal death, via H2‐receptor activation (1)

Whatever the mechanisms involved, the present data show that invasion and degranulation of mast cells, associated with neuronal HA accumulation, occur massively in the immature ischemic brain. They suggest that blockade of HA receptors and/or drugs targeting mast cells could pharmacologically modulate neonatal ischemic injury, and might constitute a therapeutic approach of choice in cerebral injuries occurring in the developing brain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adachi N (2005) Cerebral ischemia and brain histamine. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 50:275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adachi N, Oishi R, Saeki K (1991) Changes in the metabolism of histamine and monoamines after occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats. J Neurochem 57:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adachi N, Itoh Y, Oishi R, Saeki K (1992) Direct evidence for increased continuous histamine release in the striatum of conscious freely moving rats produced by middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 12:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auvinen S, Panula P (1988) Development of histamine‐immunoreactive neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 276:289–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benjelloun N, Renolleau S, Represa A, Ben Ari Y, Charriaut‐Marlangue C (1999) Inflammatory responses in the cerebral cortex after ischemia in the P7 neonatal. Rat Stroke 30:1916–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berger R, Garnier Y (1999) Pathophysiology of perinatal brain damage. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 30:107–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biran V, Joly LM, Heron A, Vernet A, Vega C, Mariani J, Renolleau S, Charriaut‐Marlangue C (2006) Glial activation in white matter following ischemia in the neonatal P7 rat brain. Exp Neurol 199:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Busch AE, Karbach U, Miska D, Gorboulev V, Akhoundova A, Volk C, Arndt P, Ulzheimer JC, Sonders MS, Baumann C, Waldegger S, Lang F, Koepsell H (1998) Human neurons express the polyspecific cation transporter hOCT2, which translocates monoamine neurotransmitters, amantadine, and memantine. Mol Pharmacol 54:342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coeroli L, Renolleau S, Arnaud S, Plotkine D, Cachin N, Plotkine M, Ben Ari Y, Charriaut‐Marlangue C (1998) Nitric oxide production and perivascular tyrosine nitration following focal ischemia in neonatal rat. J Neurochem 70:2516–2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dimitriadou V, Rouleau A, Tuong MD, Ligneau X, Newlands GF, Miller HR, Schwartz JC, Garbarg M (1996) Rat cerebral mast cells undergo phenotypic changes during development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 97:29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dropp JJ (1972) Mast cells in the central nervous system of several rodents. Anat Rec 174:227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dropp JJ (1979) Mast cells in the human brain. Acta Anat (Basel) 105:505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ericson H, Watanabe T, Kohler C (1987) Morphological analysis of the tuberomammillary nucleus in the rat brain: delineation of subgroups with antibody against L‐histidine decarboxylase as a marker. J Comp Neurol 263:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferriero DM (2004) Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med 351:1985–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gill CJ, Rissman EF (1998) Mast cells in the neonate musk shrew brain: implications for neuroendocrine immune interactions. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 111:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grundemann D, Liebich G, Kiefer N, Koster S, Schomig E (1999) Selective substrates for non‐neuronal monoamine transporters. Mol Pharmacol 56:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Happola O, Ahonen M, Panula P (1991) Distribution of histamine in the developing peripheral nervous system. Agents Actions 33:112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heron A, Pollard H, Dessi F, Moreau J, Lasbennes F, Ben Ari Y, Charriaut‐Marlangue C (1993) Regional variability in DNA fragmentation after global ischemia evidenced by combined histological and gel electrophoresis observations in the rat brain. J Neurochem 61:1973–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heron A, Rouleau A, Cochois V, Pillot C, Schwartz JC, Arrang JM (2001) Expression analysis of the histamine H(3) receptor in developing rat tissues. Mech Dev 105:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoskison MM, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Shuttleworth CW (2007) Calcium‐dependent NMDA‐induced dendritic injury and MAP2 loss in acute hippocampal slices. Neuroscience 145:66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu W, Xu L, Pan J, Zheng X, Chen Z (2004) Effect of cerebral ischemia on brain mast cells in rats. Brain Res 1019:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jin Y, Vannucci SJ, Silverman AJ (2006) Mast Cell Stabilization Limits Hypoxic‐Ischemic Brain Damage in the Immature Rat. Society for Neuroscience: Atlanta. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joly LM, Benjelloun N, Plotkine M, Charriaut‐Marlangue C (2003) Distribution of Poly(ADP‐ribosyl)ation and cell death after cerebral ischemia in the neonatal rat. Pediatr Res 53:776–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jonker JW, Schinkel AH (2004) Pharmacological and physiological functions of the polyspecific organic cation transporters: oCT1, 2, and 3 (SLC22A1‐3). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 308:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karlstedt K, Sallmen T, Eriksson KS, Lintunen M, Couraud PO, Joo F, Panula P (1999) Lack of histamine synthesis and down‐regulation of H1 and H2 receptor mRNA levels by dexamethasone in cerebral endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19:321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lambracht‐Hall M, Dimitriadou V, Theoharides TC (1990) Migration of mast cells in the developing rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 56:151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martres MP, Baudry M, Schwartz JC (1975) Histamine synthesis in the developing rat brain: evidence for a multiple compartmentation. Brain Res 83:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mesples B, Fontaine RH, Lelievre V, Launay JM, Gressens P (2005) Neuronal TGF‐beta1 mediates IL‐9/mast cell interaction and exacerbates excitotoxicity in newborn mice. Neurobiol Dis 18:193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Michelsen KA, Lozada A, Kaslin J, Karlstedt K, Kukko‐Lukjanov TK, Holopainen I, Ohtsu H, Panula P (2005) Histamine‐immunoreactive neurons in the mouse and rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur J Neurosci 22:1997–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nelson KB, Lynch JK (2004) Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol 3:150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nissinen MJ, Panula P (1995) Developmental patterns of histamine‐like immunoreactivity in the mouse. J Histochem Cytochem 43:211–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Panula P, Yang HY, Costa E (1984) Histamine‐containing neurons in the rat hypothalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81:2572–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Panula P, Happola O, Airaksinen MS, Auvinen S, Virkamaki A (1988) Carbodiimide as a tissue fixative in histamine immunohistochemistry and its application in developmental neurobiology. J Histochem Cytochem 36:259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Park JS, Bateman MC, Goldberg MP (1996) Rapid alterations in dendrite morphology during sublethal hypoxia or glutamate receptor activation. Neurobiol Dis 3:215–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Patkai J, Mesples B, Dommergues MA, Fromont G, Thornton EM, Renauld JC, Evrard P, Gressens P (2001) Deleterious effects of IL‐9‐activated mast cells and neuroprotection by antihistamine drugs in the developing mouse brain. Pediatr Res 50:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pearce LA, Schanberg SM (1969) Histamine and spermidine content in brain during development. Science 166:1301–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reiner PB, Semba K, Fibiger HC, McGeer EG (1988) Ontogeny of histidine‐decarboxylase‐immunoreactive neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus of the rat hypothalamus: time of origin and development of transmitter phenotype. J Comp Neurol 276:304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Renolleau S, Aggoun‐Zouaoui D, Ben Ari Y, Charriaut‐Marlangue C (1998) A model of transient unilateral focal ischemia with reperfusion in the P7 neonatal rat: morphological changes indicative of apoptosis. Stroke 29:1454–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ryu JH, Yanai K, Sakurai E, Kim CY, Watanabe T (1995) Ontogenetic development of histamine receptor subtypes in rat brain demonstrated by quantitative autoradiography. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 87:101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schwartz JC, Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Pollard H, Ruat M (1991) Histaminergic transmission in the mammalian brain. Physiol Rev 71:1–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Skaper SD, Facci L, Kee WJ, Strijbos PJ (2001) Potentiation by histamine of synaptically mediated excitotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurones: a possible role for mast cells. J Neurochem 76:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Strbian D, Karjalainen‐Lindsberg ML, Tatlisumak T, Lindsberg PJ (2006) Cerebral mast cells regulate early ischemic brain swelling and neutrophil accumulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26:605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tuomisto L, Panula P (1991) Development of histaminergic neurons. In: Histaminergic Neurons: Morphology and Function. Watanabe T, Wada H (eds), pp. 177–192. CRC Press: Boca Raton. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vanhala A, Yamatodani A, Panula P (1994) Distribution of histamine‐, 5‐hydroxytryptamine‐, and tyrosine hydroxylase‐immunoreactive neurons and nerve fibers in developing rat brain. J Comp Neurol 347:101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Volpe JJ (2001) Perinatal brain injury: from pathogenesis to neuroprotection. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 7:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu X, Kekuda R, Huang W, Fei YJ, Leibach FH, Chen J, Conway SJ, Ganapathy V (1998) Identity of the organic cation transporter OCT3 as the extraneuronal monoamine transporter (uptake2) and evidence for the expression of the transporter in the brain. J Biol Chem 273:32776–32786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu X, Huang W, Prasad PD, Seth P, Rajan DP, Leibach FH, Chen J, Conway SJ, Ganapathy V (1999) Functional characteristics and tissue distribution pattern of organic cation transporter 2 (OCTN2), an organic cation/carnitine transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290:1482–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang M, Venable JD, Thurmond RL (2006) The histamine H4 receptor in autoimmune disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 15:1443–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhuang X, Silverman AJ, Silver R (1999) Distribution and local differentiation of mast cells in the parenchyma of the forebrain. J Comp Neurol 408:477–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]