Abstract

Background:

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) appears more prevalent among children with intellectual disabilities (ID) as compared to children with typical development (Christensen et al., 2013). However, it remains unclear what drives this difference.

Methods:

Data from 70 youth with typical development (TD) and 20 youth with ID were drawn from The Collaborative Family Study. The relationships between child temperament and parent psychopathology (age 3), parenting behavior and child behavior problems (age 5), and ODD diagnosis (age 13) were explored via structural equation modeling. The predicted model was examined in the total sample, among children with and without ID separately, and with status (TD vs. ID) as a predictor.

Conclusion:

Many of the predicted relationships hold true for youth with and without ID. However, we found an unexpected relationship between negative-controlling parenting and child externalizing behavior problems for children with ID. The positive role of parental intrusiveness for children with ID is discussed, although limitations are noted due to the small sample size and preliminary nature of this study.

Keywords: Intellectual Disability, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Comorbidity, Etiology, Conduct Problems

Introduction

It is well established in the empirical literature that children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities (ID) are at a heightened risk for comorbid mental health disorders (Baker et al., 2010; Caplan et al., 2015; Einfeld, et al., 2011; Platt, et al., 2019). When categories of psychiatric disturbance are considered, disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) appear to be particularly elevated for youth with ID, with 20– 25% meeting criteria for a DBD (Emerson & Hatton, 2007). In contrast, prevalence rates for DBDs in children with typical development are approximately 4% (APA 2013; Emerson & Hatton, 2007).

The present study focuses on Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), a common psychiatric disorder for children, and a well-known disruptive behavior disorder. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder – 5th Edition (DSM-V; APA 2013, page 462) defines ODD as “a pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior, or vindictiveness lasting at least six months…and exhibited during interactions with at least one individual who is not a sibling.” Symptoms of ODD include losing one’s temper, being touchy or easily annoyed, being angry or resentful, arguing with authority figures or adults, actively defying authority figures, deliberately annoying others, blaming others for mistakes, and being spiteful or vindictive. To receive a diagnosis of ODD, children must exhibit four of these eight symptoms for a period of at least 6 months with significant impairment in social, academic, and/or occupational functioning.

Research suggests that children with ID demonstrate significantly higher rates of ODD than typically developing peers and, in one study, children with ID were twice as likely to meet ODD criteria as children with typical development (Christensen et al., 2013). However, these authors found no differences in the epidemiology of ODD for children with and without ID, suggesting that the clinical presentation of these disorders is very similar (with the exception of the aforementioned difference in prevalence rates). The current study expands upon previous research by drawing data from a 10-year longitudinal investigation to examine the etiology of ODD for children with and without ID. In so doing, the authors hope to address (a) whether ODD is the same disorder for both populations and (b) why the prevalence of ODD is higher for children with ID.

There has been little research to-date focusing on the development of ODD specifically. Instead, researchers have focused on risk factors for conduct problems -- often defined as a spectrum of aggressive, antisocial, defiant, delinquent and disruptive behaviors. Findings suggest that a variety of child characteristics and parental attributes contribute, often via parent-child interactions. With respect to child characteristics, researchers have focused on child temperament. Although different researchers use different nosology, negative emotionality/affectivity1 and fearfulness2 have been discussed as closely related to externalizing behavior problems (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). Negative emotionality can be understood as the frequency and intensity of negative mood states, while fearfulness/fearlessness can be understood as the child’s willingness to approach novel situations and stimuli (Kagan, 1989; Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). Both of these traits appear to vary across individuals, and there is substantial research suggesting that both negative emotionality and fearlessness are related to externalizing behavior problems (Baglivio, et al., 2016; Brandes et al., 2018; Stoltz, et al., 2017).

Parent variables associated with child conduct problems include a parental history of psychopathology; Lahey and co-authors (1999) suggested that parents with antisocial behaviors and those dealing with psychopathology such as substance use and/or depression may have chronically lower thresholds for tolerating their child’s behavior. Accordingly, these parents may be more likely to respond to oppositional behavior with inadequate supervision, inconsistent and/or overly punitive punishment, and possibly neglect (Callender et al., 2012). Over time, this back-and-forth between parent and child may escalate both the frequency and nature of behavior problems on the part of the child.

There has been some research supporting this parent-child interactional model of conduct problems (Jaffee et al., 2006; Lansford et al., 2011; Wang & Kenny, 2014). Simons and co-authors. (2004) used latent growth curve analyses to examine the trajectory of conduct problems over late childhood and adolescence; the goal of the study was to determine whether latent traits of impulsivity, risk-taking, and insensitivity to the needs of others explained the increase in conduct problems over time. The authors also examined a transactional model in which impulsive and aggressive children interact with their temperamentally-similar parents and through increasingly ineffective parenting, engage in more problematic behaviors. Contrasting these models, they found evidence for the role of ineffective parenting as a mediator between early child conduct problems and later antisocial behaviors.

As indicated, much of the research on child behavior disorders has focused on conduct problems; we are not aware of any research examining the aforementioned etiological model in children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). ODD is often conceptualized as part of a continuum of conduct problems with conduct disorder (CD), and there is some research suggesting that each of the risk factors associated with the development of conduct problems is also associated with ODD when considered separately. However, associations tend to be more robust with CD. Research is needed to examine the development of ODD to determine whether the same model of child temperament and ineffective parenting that account for more severe conduct problems also account for the emergence of ODD.

Children with intellectual disabilities experience a higher rate of general behavior problems apart from ODD (Baker et al., 2002; Whitaker & Read, 2006). Research suggests that behavior problems may contribute to increased parenting stress in parents of children with ID, and that increased parenting stress may lead to subsequent increases in child behavior problems (Baker, et al., 2003; Orsmond et al., 2003; Neece et al., 2012). Moreover, this link may be mediated by parent-child interactions. Given that much of the research on risk factors for conduct problems highlight negative interactions between parents and children, it may be the case that the higher prevalence of disruptive behavior disorders (and ODD in particular) among youth with ID is the result of increased behavior problems and/or parenting stress that heighten the frequency or intensity of negative interactions.

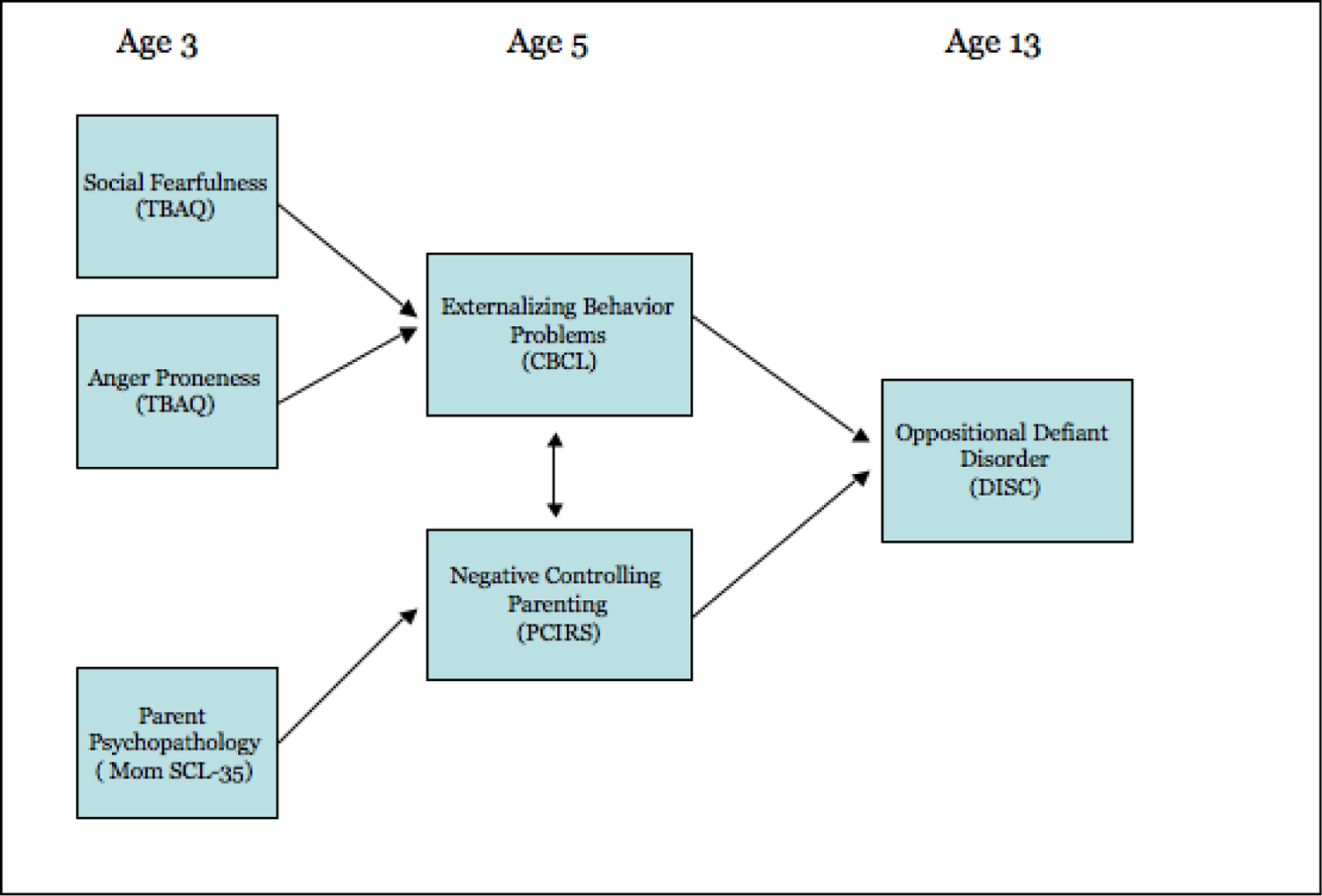

The current study examines the etiology of ODD in early adolescence, using data from families of children with developmental delays. We propose a model in which child temperament (specifically, negative emotionality and social fearfulness) contribute to later child externalizing behaviors, while parent psychopathology contributes to negative/controlling parenting behaviors. We suggest that ODD symptoms emerge from the interaction between child externalizing behavior problems and negative/controlling parenting behaviors. We examined this model (shown in Figure 1) in the combined sample, and separately for children with and without ID. We further examined the contribution of status group (i.e. having a developmental delay) to the model by adding it as a predictor with a relationship to later externalizing behavior problems.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model of Early Child & Parent Factors that Contribute to Adolescent ODD

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited to participate in a longitudinal study (entitled The Collaborative Family Study) conducted at University of California, Los Angeles, University of California, Riverside, and Pennsylvania State University. Families of typically developing children and families of children with developmental delays, residing in Southern California or Central Pennsylvania, were recruited through community agencies serving children with developmental disabilities, and the corresponding local preschools and daycare centers. Children were enrolled between ages 30 and 39 months. Selection criteria for typically developing (TD) children included a score at intake of 85 or above on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development – II (BSID II; Bayley, 1969), no history of prematurity, and no diagnosis of a developmental disability by an outside agency or professional (e.g. Regional Center). Criteria for children with developmental delays (DD) included a score between 40 and 84 on the BSID II, being ambulatory, and never having received a diagnosis of autism.

Participants and their families completed a battery of questionnaires and lab tasks annually, at child ages 3–9 years, and again at age 13. As is expected in longitudinal research, there was some attrition over time (Gustavson et al., 2012). Thus, the data included in this study are from 90 families who completed assessments at child ages 3, 5, and 13.

Although the BSID-II was used to recruit participants with and without developmental delays, scores from the BSID-II have been shown to have limited validity in predicting later cognitive abilities, particularly among high-risk populations (e.g. low-birth-weight infants; Hack et al., 2005; Luttikhuizen dos Santos et al., 2013). As such, children were classified based on their scores on the Stanford-Binet IV and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales II (VABS) at child age 5. The inclusion criterion for the typically developing group was an IQ on the Stanford-Binet IV above 85. Participants were considered to have an intellectual disability if they received an IQ of 70 or below on the Stanford-Binet IV and a score of 85 or below on the Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior II (VABS). Participants were considered to have borderline intellectual functioning (a DSM-IV-TR term, APA, 2000) if they scored between 71 and 84 on the Stanford-Binet IV and had scores on the VABS below 85. For this study, children with borderline intellectual functioning (n = 7) and those with intellectual disabilities (mild or moderate intellectual disabilities; n=13) were combined into one group (termed Developmental Delay, DD). Combining these groups is supported by prior research suggesting that children with borderline intellectual functioning experience rates of emotional and behavior problems that are similar to children with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities (Emerson & Einfeld., 2010).

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics at child age 13 by developmental status group (TD and DD). Child gender did not differ by status group. Child race, family income, and mothers’ education were significantly related to group status. The TD group had a higher percentage of white families, more families with an annual income of $50,000 or higher, and mothers completing significantly more years of school. Mother’s education did not have a significant relationship with any of the variables of interest in our model. Child race had a significant relationship with anger proneness on the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ-A) only. However, family income related significantly to externalizing behavior problems on the CBCL, ODD symptoms on the DISC, anger proneness on the TBAQ-A and parent psychopathology on the SCL. We did not covary any of these demographic variables in the analyses because of limitations related to the sample size and the number of pathways specified in the models. However, the relationship between family income and the aforementioned variables is supported by previous research and should be considered in future models that expand upon the model we examined.

Table 1.

Demographics by Delay Status at Child Age 13

| Demographic | Typically Developing (n=70) |

Developmental Delay (n=20) |

X2 or t (df) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| WISC-IV IQ | 109.3 (12.2) | 61.1 (14.0) | t = 14.53 (85)** |

| Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior | 95.8 (9.5) | 72.1 (14.3) | t = 8.05 (75)** |

| Gender (% Male) | 41 (58.6%) | 10 (52.6%) | X2 = 0.22 (N = 89) |

| Race/Ethnicity (% White-non Hispanic) | 46 (65.7%) | 7 (36.8%) | X2 = 5.17 (N=89)* |

| Mother and Family | |||

| Income $50,000+ | 57 (81.4%) | 11 (57.8%) | X2 = 4.59 (N=98)(*) |

| Mother’s Years of Schooling | 16.3 (2.3) | 14.4 (2.2) | t = 3.03 (85)* |

p < .05

p < .001

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the three collaborating universities. Interested parents completed a telephone intake interview between child ages 30 and 39 months. Subsequently, as close as possible to child age 36 months, two research assistants visited the family. After reviewing procedures, answering questions, and obtaining informed consent, the research assistants administered the Bayley Scales of Infant Development –II (Bayley, 1993) to the child. The data in the present report were obtained from measures completed by parents at the home visit at child age 3, a center visit at child age 5, and a center visit at age 13.

Measures

Stanford-Binet IV (SB-IV; (Thorndike et al.,1986)).

The SB-IV is a widely used instrument designed to assess the cognitive abilities of individuals 2 to 23 years in age. It yields a composite IQ score with a normative mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The composite score of the SB-IV was used as a measure of overall cognitive abilities at child age 5 years.

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003):

Scores from the Vocabulary, Matrix Reasoning, and Arithmetic subtests of the WISC-IV were used to further determine an estimated IQ range and confirm status group classification at child age 13. The sum of these three subtests correlates highly (r=.91) with the full WISC-IV (Sattler & Dumont, 2004).

Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior-II (VABS; Sparrow et al., 2005).

The VABS is a semi-structured interview conducted with a parent or other caregiver that assesses the child’s adaptive behavior in multiple domains. Scores from the communication, daily living skills and socialization subscales comprise the Adaptive Behavior Composite. The VABS was administered at ages 5 and 13, and the composite score was used to group participants into the DD and TD groups.

Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (Abbreviated; TBAQ-A; Goldsmith, 1996).

The TBAQ-A is a caregiver-report questionnaire of toddler behavior that includes five subscales addressing activity level, pleasure, social fearfulness, anger proneness, and interest/persistence. It has high internal consistency within the subscales. Likewise, there is good evidence for convergent validity with other measures of temperament. The TBAQ-A was administered to parents at child age 3 as a measure of child temperament.

Symptom Checklist-35 (SCL-35; Derogatis 1993).

The SCL-35 is a widely used measure of psychiatric symptomatology with subscales measuring somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, and hostility. Higher scores on the SCL-35 reflect more psychological symptoms. The SCL-35 at age 3 was used as a measure of maternal psychopathology.

Parent-Child Interaction Rating System (PCIRS; Belsky et al.,1996).

The Parent–Child Interaction Rating System is a coding system for parent-child interactions that can be applied to a variety of observational tasks. The PCIRS includes ratings of maternal behavior and child behavior, as well as dyadic ratings of mother-child interactions. Each variable is coded on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (not all characteristic) to 5 (highly characteristic). Maternal codes include positivity, negativity, intrusiveness, sensitivity, stimulation of cognition and detachment. Codes are combined to create two composite scores – positive parenting (positivity + sensitivity + stimulation of cognition – detachment) and negative/controlling parenting (intrusiveness + negativity – sensitivity). The PCIRS negative/controlling parenting score was used at age 5 as a measure of parenting behaviors.

Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1 ½ - 5 (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

This preschool version of the CBCL has 99 items that indicate child problems, listed in alphabetical order (from “aches and pains without medical cause” to “worries”). The respondent indicates, for each item, whether it is “not true” (0), “somewhat or sometimes true” (1), or “very true or often true” (2), now or within the past two months. The CBCL yields a total problem score, broadband externalizing and internalizing scores, 7 narrow-band syndrome scores, and 5 DSM-oriented scores. The externalizing behavior problems subscale at age 5 was used as a measure of mother-reported externalizing behavior problems.

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (DISC-IV; Costello et al., 1985).

The DISC-IV is a highly structured diagnostic interview administered to the parent or caregiver that covers DSM-IV-TR criteria for all of the major mental illnesses observed in children and adolescents. Respondents are asked about the presence or absence of symptoms within the diagnostic categories, and disorder-specific algorithms are used to derive diagnoses from responses to individual items. The DISC-IV was administered at ages 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 13 as a measure of child psychopathology. Standard administration was followed, except that mothers were given a brief description of each area (e.g. anxiety, fear, behavior problems) and asked to select those areas relevant to their child (with a minimum of one area). This procedure reduces administration time, increases reliability, and is judged to be more engaging for the respondents than the standard procedure of administering all areas in a fixed order (Edelbrock et al., 1999). For the 13-year assessment, however, all participants were administered the ADHD and ODD sections of the DISC-IV regardless of whether they endorsed these areas as being relevant for their child.

Results

Prior to examining the predicted model, we ran bivariate correlations to confirm expected relationships between predictor and outcome variables. Tables 2 and 3 show these analyses, conducted with the whole data set, including data from children with and without developmental delays. Overall, results suggest that anger proneness on the TBAQ-A was significantly related to the externalizing behavior problem subscale of the CBCL at age 5, and to the number of ODD symptoms on the DISC at age 13. However, social fearfulness on the TBAQ-A was not related to CBCL externalizing behavior problems or ODD symptoms. The total score from the Symptom Checklist-35 was significantly related to TBAQ-A anger proneness at age 3, negative/controlling parenting behavior on the PCIRS at age 5, CBCL externalizing behavior problems at age 5, and ODD symptoms on the DISC at age 13. Interestingly, negative/controlling parenting behavior as measured by the PCIRS was not related to ODD symptoms at age 13 or CBCL externalizing behavior problems at age 5.

Table 2.

A Priori Regression Tables – DISC ODD Symptoms at Child Age 13

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 1.24 | 0.21 | 5.93** | |

| Negative Parenting | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.34 |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T value | |

| (Constant) | 0.42 | 0.29 | 1.44 | |

| CBCL Externalizing Behavior Problems | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 3.71** |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T value | |

| (Constant) | −0.94 | 0.70 | −1.34 | |

| TBAQ Anger Proneness Subscale | 0.70 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 3.23* |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T Value | |

| (Constant) | 1.77 | 0.67 | 2.66* | |

| TBAQ Social Fear Subscale - | −0.18 | 0.22 | −0.10 | −0.84 |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T Value | |

| (Constant) | 0.76 | 0.28 | 2.73* | |

| Mother SCL Total | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 2.40* |

Table 3.

A Priori Regression Tables – CBCL Externalizing Problems & PCIRS Parenting Behaviors

| CBCL Externalizing Problems at Child Age 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T Value | |

| (Constant) | 11.24 | 1.01 | 11.10** | |

| Negative Parenting | −0.39 | 0.61 | −0.07 | −0.63 |

| (Constant) | −7.62 | 3.23 | −2.36* | |

| TBAQ Anger Proneness Subscale | 5.97 | 0.99 | 0.54 | 5.98** |

| (Constant) | 11.88 | 3.32 | 3.58* | |

| TBAQ Social Fear Subscale | −0.29 | 1.11 | −0.03 | −0.26 |

| PCIRS Negative Parenting Behaviors at Child Age 5 | ||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T Value | |

| (Constant) | 1.56 | 0.09 | 16.80** | |

| Mother SCL Total | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 1.98* |

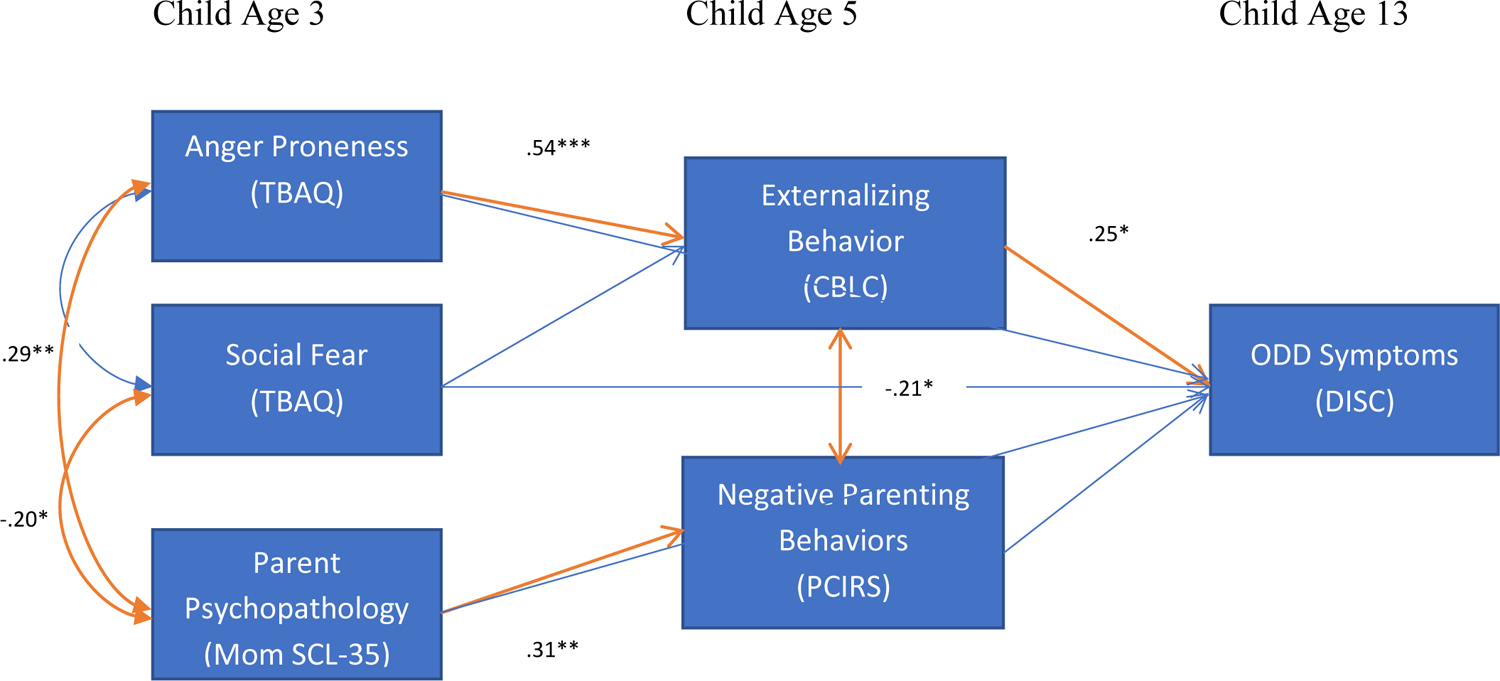

Following this, we examined the predicted model in the total data set using MPlus software. Figure 2 depicts both the predicted pathways and the results of this model. Anger proneness at age 3 was related to externalizing behavior at age 5. Parent psychopathology at child age 3 related to parenting behaviors at age 5. Externalizing behavior mediated the relationship between anger proneness at age 3 and ODD symptoms at age 13 (as the direct relationship between anger proneness and ODD symptoms no longer exists when externalizing behavior is included). Surprisingly, there was a significant negative relationship between negative/controlling parenting behaviors and child externalizing behavior. Moreover, there was no relationship between parenting behaviors at age 5 and ODD symptoms at age 13.

Figure 2:

Model 1 – Etiology of ODD Symptoms

(*) p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Note: All pathways included in the model are represented. Those in red are the significant pathways.

As shown in Table 4, measures of the variance explained for the dependent variables of the model (by the model’s paths to that variable) suggest that 30% of the variance in CBCL externalizing problems was explained by the model (p < .001) and 10% of the variance in negative parenting behavior was explained by the model (p = .11). More importantly, it appears that 18% of the variance in oppositional defiant symptoms was explained by the current model (p = .018). The model’s fit statistics were Chi-square/degree of freedom ratio = 2.47, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .92, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = .13 and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = .047. These values were contrasted with cut-offs discussed in the literature of <3 for the Chi-square/degree of freedom ratio (Carmines & McIver, 1981), CFI >.90 (Tanaka, 1987), RMSEA < .05 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and SRMR <.08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). According to all but the RMSEA, the model is a good fit for the data. Of note, there is some indication that RMSEA values may be subject to sampling error for models with small degrees of freedom and low sample sizes (Kenny, Kaniskan, & McCoach, 2011). As such, some researchers elect not to use the RMSEA or to focus on the confidence interval instead. In the current model, the 90% confidence interval is quite large (0.00 to 0.249), but includes zero, suggesting that the model may be a good fit for the data.

Table 4.

Models 1 & 2 – Variance Explained

| Model 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | R2 Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. |

| CBCL Externalizing | 0.30 | 0.08 | 3.65*** |

| Negative Parenting | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.60 |

| Oppositional Sx | 0.18 | 0.07 | 2.37* |

| Model 2 | |||

| Variable | R2 Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. |

| CBCL Externalizing | 0.33 | 0.08 | 4.09*** |

| Negative Parenting | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.67(*) |

| Oppositional Sx | 0.18 | 0.07 | 2.37* |

Next, we examined the aforementioned model in the two status groups separately. For the TD group, the significant pathways remained the same, with three exceptions. First, in this model, there was a significant negative relationship between social fearfulness and externalizing behavior problems. Second, there was no longer a significant negative relationship between negative/controlling parenting behaviors and externalizing behavior problems. Finally, the pathways between externalizing problems at age 5 and ODD symptoms at age 13, and between parent psychopathology and negative/controlling parenting dropped to trend level significance. This is at least in part the result of the decrease in sample size and the subsequent increase in standard errors. The variance explained in negative/controlling parenting, externalizing behavior problems and ODD symptoms was 4% (ns), 28% (p = .004) and 17% (p=.04), respectively. Generally, the fit statistics were within acceptable range with a Chi-square/degree of freedom = 1.96, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.12 and SRMR = 0.057.

For the DD group, all of the significant pathways remained the same as the combined sample’s model. However, the relationship between externalizing behavior problems and ODD symptoms dropped from significant to a trend level. Again, this is likely the result of larger standard errors due to the smaller sample size. The variance explained in negative/controlling parenting, externalizing behavior problems and ODD symptoms was 40% (p=.004), 31% (p = .02) and 47% (p=.08), respectively. However, the fit statistics were not within an acceptable range with a Chi-square/degree of freedom = 5.45, CFI = 0.60, RMSEA = 0.48 and SRMR = 0.227. This is likely the result of the very small sample size (n=20) for this group.

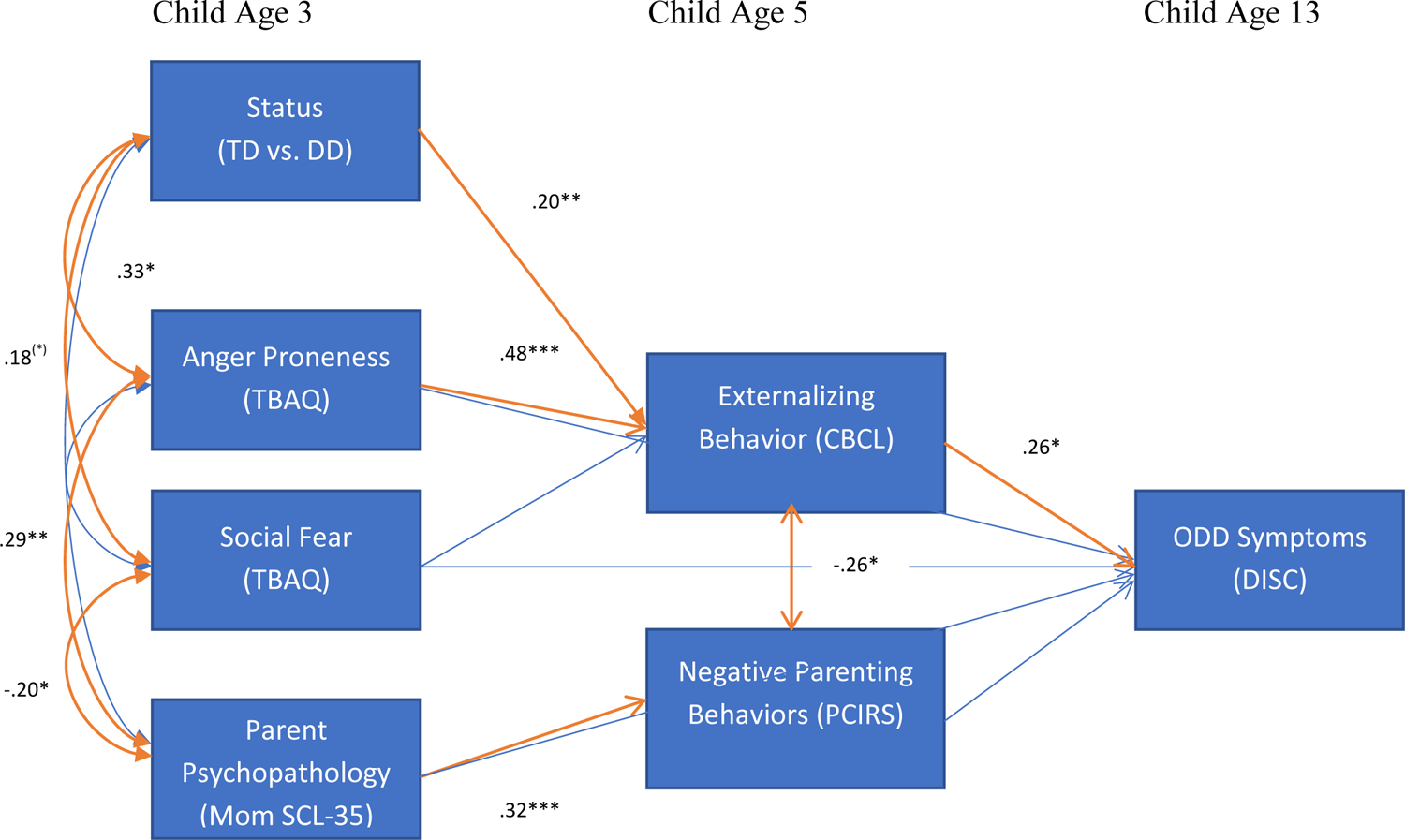

Finally, we examined a model that includes developmental delay as a variable impacting the rate of externalizing behavior problems. Figure 3 depicts both the predicted pathways and the results of this model. Anger proneness at age 3 related to externalizing behavior at age 5 and parent psychopathology at child age 3 related to negative/controlling parenting behaviors at age 5. Status had a significant contribution to externalizing behavior, and externalizing behavior appeared to mediate the relationship between anger proneness at age 3 and ODD symptoms at age 13. Again, there was a negative relationship between externalizing behavior problems and negative/controlling parenting behaviors at age 5. There continued to be no relationship between parenting behaviors at age 5 and ODD symptoms at age 13.

Figure 3:

Model 2 – Etiology of ODD Symptoms with Status as Predictor

(*) p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Note: All pathways included in the model are represented. Those in red are the significant pathways.

As shown in Table 4, measures of the variance explained by the model suggest that 33% of the variance in CBCL externalizing problems was explained by the model (p < .001) and 10% of the variance in negative parenting behavior was explained by the model (p < .10). More importantly, it appears that 18% of the variance in oppositional defiant symptoms was explained by the current model (p = .02). When we examined the overall fit statistics of the model, however, we found that some of the fit indices were poor. The current model’s fit statistics were Chi-square/degree of freedom = 2.26, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .89, RMSEA = .12 and SRMR = .053. These values were contrasted with the aforementioned cut-offs discussed in the literature of <3 for the Chi-square/degree of freedom ratio (Carmines & McIver, 1981), CFI >.90 (Tanaka, 1987), RMSEA < .05 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and SRMR < .09 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Accordingly, while the model explained significant variance in our dependent variables, it may not be a good fit for our data as only two of the four indices were above the reported criteria. Moreover, while greater variance in externalizing behavior was explained by the addition of status to the model, this is minimal and there was no change in variance explained for ODD symptoms.

Discussion

Given our small sample size, our results should be considered preliminary. However, our findings provide insight into the variables that may contribute to the etiology of ODD. First, our results suggest that there are significant relationships between measures of early childhood temperament and later ODD symptoms for children with and without DD. In particular, anger proneness on the TBAQ at age 3 was significantly related to symptoms of ODD on the DISC at age 13 (regardless of status group). This is consistent with prior research linking measures of negative emotionality in early childhood to later conduct problems. Of interest, however, we found a significant negative relationship between social fearfulness and ODD symptoms in the TD sample only. For the DD group, this relationship was non-significant. Accordingly, it appears that while social fearfulness relates to later ODD symptoms for children with typical development, this is not the case for children with DD. One possibility is that ODD symptoms in children with DD occur more as a function of their communication deficits in combination with negative emotionality, and thus, that social inhibition is unlikely to decrease these behaviors.

When measures of temperament are examined within the proposed etiological model, the relationship between anger proneness at age 3 and ODD symptoms at age 13 appears to be fully mediated by CBCL externalizing behavior problems, assessed here at age 5 (as the prior relationship between anger proneness and ODD symptoms disappears when externalizing behavior problems is added). In many ways, this finding appears intuitive and much of the literature supports relationships between measures of negative emotionality and later behavior problems beyond a specific relationship to conduct disorder/conduct problems. However, it is also possible that the results simply reflect the strong relationship between externalizing behavior problems and ODD, and not a path by which children develop ODD (e.g. demonstrating a broad array of behavior problems prior to developing ODD).

Our results also support a relationship between parent psychopathology on the SCL-35 at age 3 and ODD symptoms at age 13. However, this relationship was only significant when these variables were considered alone. When included in a model with child temperament, there was no longer a direct relationship between parent psychopathology at age 3 and ODD symptoms at age 13. Thus, it appears that the relationship between parent psychopathology and ODD may be fully mediated by the child’s temperament; the strong relationships between parent psychopathology and child temperament seen in the final model is evidence for this. Accordingly, it may be that parent psychopathology relates to child temperament, and that the latter is related to later externalizing behavior problems and ODD.

We also found a significant relationship between parent psychopathology as measured by the SCL-35 and negative/controlling parenting behaviors on the PCIRS. This relationship is consistent with previous research, which suggests that parents with antisocial behaviors and those dealing with psychopathology such as substance use and/or depression may have a chronically lower threshold for misbehavior and are more likely to respond in a harsh or negative way (Lahey, et al., 1999).

Interestingly, there appears to be a negative relationship between negative/controlling parenting and externalizing behavior problems, a finding that is somewhat counterintuitive (one would expect more externalizing behavior problems in response to higher levels of negative/controlling parenting). However, when we look at the two status groups separately, it appears that this relationship is driven by the DD group (and non-significant for the TD group). Previous research suggests that parents of children with ID may be more intrusive than parents of typically developing children (e.g. Herman & Shantz, 1983; Marfo, 1992). Moreover, this parental intrusiveness may be beneficial for children with ID depending upon the purpose served by the parent’s behavior and the level of sensitivity to their child’s needs and goals (Cielinski et al., 1995). Accordingly, the negative relationship between negative/controlling parenting and externalizing behavior problems may reflect the positive impact of parental intrusiveness for children with ID – a benefit that does not occur for children with typical development.

There was a non-significant relationship between negative/controlling parenting and ODD symptoms at age 13. This non-significant relationship (as well as the counterintuitive relationship between negative/controlling parenting and externalizing behavior problems) may be explained by the variable used to measure negative-controlling parenting, the PCIRS. The advantage of the PCIRS is that it is a live-coded interaction between mother and child that involves a variety of tasks, which range in difficulty. In this way, the PCIRS is able to capture interactions between the mother and child during activities that elicit some amount of struggle and/or conflict. However, given the nature of the task – being observed and videotaped, involving academic tasks and/or games – it is unlikely to elicit the overly critical, harsh or inconsistent discipline that may be characteristic of parents of children with ODD. This in turn may explain the lack of relationship between parenting behaviors as measured by the PCIRS and ODD symptoms on the DISC, and may partially explain the negative relationship between negative/controlling parenting and externalizing behaviors. Instead, different measures/instruments may be necessary to truly evaluate this relationship and to capture the parenting behaviors that may result in higher behaviors problems and ODD symptoms.

Taking the model as a whole, we found that the aforementioned predictors explained a significant amount of the variance in externalizing behavior problems and ODD symptoms. Moreover, our model appeared to largely fit the data in the combined sample and for the TD group alone. However, the fit indices for the model with status as a predictor (model 2) and for the DD group alone suggest that our model may fail to sufficiently capture the relationships present in the data. To some degree, the poor fit indices likely reflect the small sample size in the DD group. However, it also may be that we are missing important elements from an etiological model of ODD for children with DD (e.g. language, adaptive functioning). As mentioned previously, it may also be the case that our poor fit is partially attributable to our inability to capture truly harsh, critical and/or inconsistent parenting through the PCIRS.

When we added status group to the model, we found a significant contribution of status to the level of externalizing behavior problems. This is consistent with the literature on intellectual disabilities, which suggests that children and adolescents with ID demonstrate substantially higher rates of behavior problems than typically developing youth (Baker, et al, 2002; Einfeld & Tonge, 1996; Whitaker & Read, 2006). Thus, our findings suggest that one reason for the increased prevalence of ODD among children with ID may relate to the separate contribution of ID to behavior problems in early childhood.

Limitations

There are a few limitations that require consideration when interpreting the results of the current study. As a result of the 10-year span of data included in the analyses, many of the larger study’s participants did not have sufficient data to be included. Accordingly, our sample size, particularly in the DD group, is quite small. Although we were able to examine the model in the two groups separately, our small sample sizes may have resulted in biased estimates and larger standard errors. Accordingly, a number of findings failed to reach significance and we are limited in our ability to generalize our findings and conclusions beyond the current sample. Likewise, the model fit indices may be biased and thus, limit our ability to determine the true fit of the proposed model. For this reason, our study is appropriately considered a preliminary analysis and future research should replicate the current study with a larger sample. Nonetheless, our results suggest that much of the model holds true for ODD. Moreover, our findings suggest how having an intellectual disability may contribute to the etiology of ODD (via an increase in externalizing behavior problems) and result in higher prevalence rates for this population.

As discussed, another limitation of the current study relates to the instrument used to measure parenting behavior. Although the PCIRS allows for a detailed coding of a live interaction between mother and child, it likely does not capture the harsh, critical or inconsistent parenting practices that may relate to later ODD. It is possible that the relationship between parenting behavior and later ODD is not present for our sample. However, it is also possible that our measure of parenting simply failed to capture the more extreme disciplinary behaviors that do relate to later ODD.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Overall, our findings provide support for an etiological model of ODD that is largely consistent with previously described models for conduct problems. We find that temperament, and anger proneness in particular, play an important role in the development of externalizing behavior problems and later, ODD symptoms. Likewise, we find that parent psychopathology may contribute to later ODD through child temperament. However, while we find connections between parent psychopathology and parenting behavior, we find counterintuitive and/or non-significant relationships between parenting behavior and externalizing behavior problems and/or ODD. For children with ID, the negative relationship between negative/controlling parenting and externalizing behavior problems may be explained by the benefit of parental intrusiveness. Nonetheless, we find no relationship between negative/controlling behavior and later ODD symptoms even when considered alone. In this way, our findings do not replicate the proposed model for the development of ODD or prior models of conduct problems.

There is some indication that our parenting measure may have failed to capture the behaviors that contribute to ODD symptoms. In this light, future research may emphasize alternative approaches to capturing parenting behavior (and disciplinary practices in particular) in order to better examine the mechanism by which parent psychopathology impacts child behavior. However, should future studies replicate our results, there are a few implications for intervention. First, children with ID appear to benefit from parental intrusiveness. This suggests that caregivers of children with ID should be encouraged to be more directive as a way of preventing or reducing later externalizing behavior problems. This is not the case for typically developing children. Instead, interventions such as the Incredible Years and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), which emphasize child-directedness as a method for reducing behavior problems, may be more appropriate. Second, our findings highlight a possible reason for the higher prevalence of ODD among children with ID – specifically, that ID makes a unique contribution to later behavior problems. In this way, our results underscore the necessity for early intervention to address behavior problems among children with ID, to prevent the development of ODD in early adolescence.

Footnotes

For the purpose of this paper, the term “negative emotionality” will be used to capture susceptibility to negative emotions, including anger, frustration, and sadness. However, other investigators have captured this construct via neuroticism or emotional reactivity (Garstein et al., 2016; Tung et al., 2018).

Of note, fearfulness is the term used here, given the name of the associated scale in the measure used in the present study. However, this construct is also captured as shyness and/or behavioral/inhibitory control (Kagan, 1989).

Contributor Information

Lisa L. Christensen, USC University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

Bruce L. Baker, University of California at Los Angeles

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-IV, Fourth Edition Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Wolff KT, DeLisi M, Vaughn MG, & Piquero AR (2016). Effortful control, negative emotionality, and juvenile recidivism: an empirical test of DeLisi and Vaughn’s temperament-based theory of antisocial behavior. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 27(3), 376–403. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic KA, & Edelbrock C (2002). Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 107(6), 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Edelbrock C, Low C, & Crnic K (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Special Issue on Family Research, 47(4–5), 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Neece CL, Fenning RM, Crnic KA, & Blacher J (2010). Mental disorders in five-year-old children with or without developmental delay: focus on ADHD. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology 39(4), 492–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N (1969). Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. New York: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Woodworth S, & Crnic K (1996). Trouble in the second year: Three questions about family interaction. Child Development, 67(2), 556–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes CM, Kushner SC, & Tackett JL (2018). Negative affect. In Editor MM (Eds), Developmental Pathways to Disruptive, Impulse Control and Conduct Disorders. (pp. 121–138), Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA & Long JS (Eds.) Testing Structural Equation Models. pp. 136–162. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Callender KA, Olson SL, Choe DE & Sameroff AJ (2102). The Effect of Parental Depressive Symptoms, Appraisals, and Physical Punishment on Later Child Externalizing Behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(3), 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan B, Neece CL, & Baker BL (2015). Developmental level and psychopathology: comparing children with developmental delays to chronological and mental age matched controls. Research in developmental disabilities, 37, 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmines EG, & McIver JP (1981). Analyzing Models with Unobserved Variables: Analysis of Covariance Structures. In Bohrnstedt GW, & Borgatta EF (Eds.), Social Measurement: Current Issues (pp. 65–115). Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli V (2000). An Examination of the Trajectory of the Adult Child’s Caregiving for an Elderly Parent. Family Relations, 49(2), 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Cielinski KL, Vaughn B, Seifer R & Conteras J (1995). Relations among sustained engagement during play, quality of play, and mother-child interaction in samples of children with down syndrome and normally developing toddlers. Infant Behavior and Development, 18, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen L, Baker B & Blacher J (2013). Oppositional Defiant Disorder in Children with Developmental Delays: Prevalence, Age of Onset and Stability. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disability. 6(3), 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, & Costello AJ (1985). Validity of the NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children: A comparison between psychiatric and pediatric referrals. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 13(4), 579–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Coons HL (1993). Self-report measures of stress. In Goldberger L, & Breznitz S (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects (2nd ed.). (pp. 200–233). New York, NY, US: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edelbrock C, Crnic K & Bohnert A (1999). Interviewing as communication: an alternative way of administering the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 27(6), 447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einfeld SL, Ellis LA, & Emerson E (2011). Comorbidity of intellectual disability and mental disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 36(2), 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einfeld SL, & Tonge J (1996). Population prevalence of psychopathology in children and adolescents with intellectual disability: I. rationale and methods. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 40(2), 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, & Einfeld S (2010). Emotional and behavioural difficulties in young children with and without developmental delay: A bi-national perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(5), 583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, Einfeld S, & Stancliffe RJ (2011). Predictors of the persistence of conduct difficulties in children with cognitive delay. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(11), 1184–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, & Hatton C (2007). Mental health of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein M, Putnam S, Aron E, & Rothbart M (2016). Temperament and Personality. Maltzman S, Editor (Eds). In The Oxford Handbook of Treatment Processes and Outcomes in Psychology: A Multidisciplinary, Biopsychosocial Approach. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, & Shaw DS (2004). Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 16(2), 313–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH (1996). Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development, 67, 218–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson K, von Soest T, Karevold E, & Roysamb E (2012). Attrition and generalizability in longitudinal studies: findings from a 15-year-population-based study and a Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Public Health, 12, 918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack M, Taylor G, Drotar D, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Wilson-Costello D, Klein N, Friedman H, Mercuri-Minich N & Morrow M (2005). Poor Predictive Validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for Cognitive Function of Extremely Low Birth Weight Children at School Age. Pediatrics. 116(2), 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman M & Shantz C (1983). Social problem solving and mother-child interactions of educable mentally retarded children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 4, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Belsky J, Harrington H, Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2006). When parents have a history of conduct disorder: How is the caregiving environment affected? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(2), 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J (1989). Temperamental contributions to social behavior. American Psychologist, 44(4), 668–674. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kaniskan B, & McCoach DB (2011). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Unpublished paper, University of Connecticut. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Miller TL, Gordon RA, & Riley AW (1999). Developmental epidemiology of the disruptive behavior disorders. In Quay HC & Hogan AE (Eds.), Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders (pp. 23–45) New York, Plenium Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID, & McBurnett K (1999). The development of antisocial behavior: An integrative causal model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(5), 669–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Pettit GS, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2011). Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttikhuizen dos Santos ES, de Kievet JF, Konigs M, van Elburg RM & Oosterlaan J (2013). Predictive value of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development on development of very preterm/very low birth weight children: A meta-analysis. Early Human Development. 89, 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfo K (1992). Correlates of maternal directiveness with children who are developmentally delayed. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 6(2), 219–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, & Baker BL (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond GI, Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, & Hong J (2003). Behavior problems in adults with mental retardation and maternal well-being: Examination of the direction of effects. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 108(4), 257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt J, Keyes K, McLaughlin K, & Kaufman A (2019). Intellectual disability and mental disorders in a US population representative sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 49(6), 952–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler JM and Dumont R (2004). Assessment of children: WISC-IV and WPPSI-III. San Diego, Ca. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chao W, Conger RD, & Elder GH (2001). Quality of parenting as mediator of the effect of childhood defiance on adolescent friendship choices and delinquency: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 63(1), 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, & Balla BA (2005). Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior-Second Ed. Circle Pine, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz S, Beijers R, Smeekens S, & Deković M (2017). Diathesis stress or differential susceptibility? testing longitudinal associations between parenting, temperament, and children’s problem behavior. Social Development. 2017; 26: 783–796. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JS (1987). “How big is big enough?”: Sample size and goodness of fit in structural equation models with latent variables. Child Development, 58(1), 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike RL, Hagen EP, & Sattler JM The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. 4th ed. Guide for administering and scoring the fourth edition. Chicago: Riverside Publishing, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tung I, Norona AN, Lee SS, Langley AK & Waterman JM (2018). Temperamental sensitivity to early maltreatment and later family cohesion for externalizing behaviors in youth adopted from foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect. 76, 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M & Kenny S (2014). Longitudinal Links Between Fathers’ and Mothers’ Harsh Verbal Discipline and Adolescents’ Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms. Child Development, 85, 908–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2003). WISC-IV Technical and Interpretive Manual. San Antonio, TX; Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker S, & Read S (2006). The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among people with intellectual disabilities: An analysis of the literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 330–345. [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Glutting JJ & Watkins MW (2003). Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Fourth Edition (SB4): Evaluating the Empirical Bases for Interpretations. In Reynolds CR & Kamphaus RW (Eds), Handbook of psychological and educational assessment: Intelligence, aptitude and achievement (pp 217–242). New York, Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]