Abstract

Importance: Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) are important for independence, safety, and productivity, and people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) can experience IADL limitations. Occupational therapy practitioners should address IADLs with their clients with PD.

Objective: To systematically review the evidence for the effectiveness of occupational therapy interventions to improve or maintain IADL function in adults with PD.

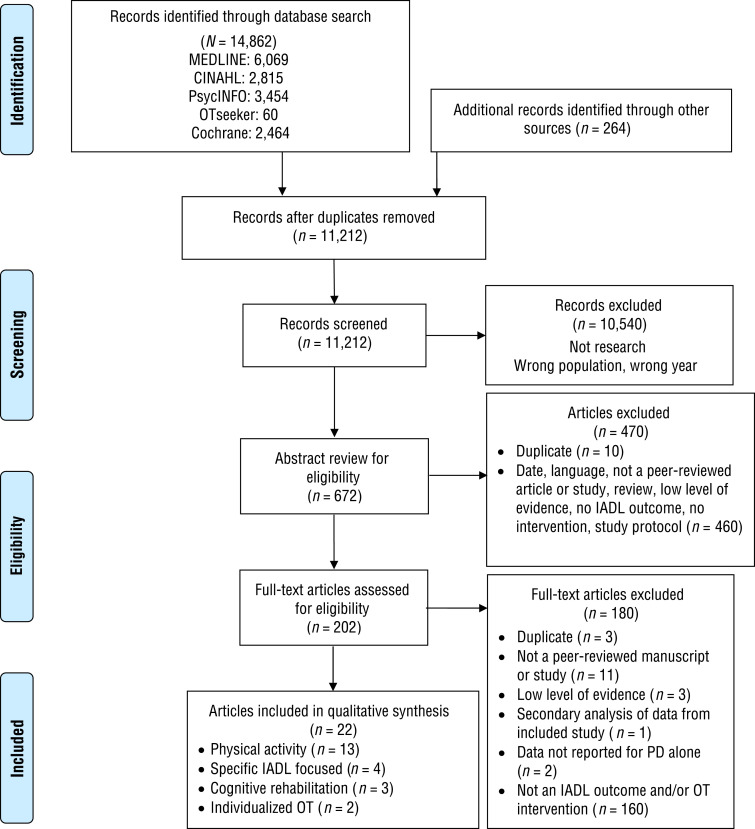

Data Sources: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, OTseeker, and Cochrane databases from January 2011 to December 2018.

Study Selection and Data Collection: Primary inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed journal articles describing Level 1–3 studies that tested the effect of an intervention within the scope of occupational therapy on an IADL outcome in people with PD. Three reviewers assessed records for inclusion, quality, and validity following Cochrane Collaboration and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Findings: Twenty-two studies met the inclusion criteria and were categorized into four themes on the basis of primary focus or type of intervention: physical activity, specific IADL-focused, cognitive rehabilitation, and individualized occupational therapy interventions. There were 9 Level 1b, 9 Level 2b, and 4 Level 3b studies. Strong strength of evidence was found for the beneficial effect of occupational therapy–related interventions for physical activity levels and handwriting, moderate strength of evidence for IADL participation and medication adherence, and low strength of evidence for cognitive rehabilitation.

Conclusions and Relevance: Occupational therapy interventions can improve health management and maintenance (i.e., physical activity levels, medication management), handwriting, and IADL participation for people with PD. Further research is needed on cognitive rehabilitation. This review is limited by the small number of studies that specifically addressed IADL function in treatment and as an outcome.

What This Article Adds: Occupational therapy intervention can be effective in improving or maintaining IADL performance and participation in people with PD. Occupational therapy practitioners can address IADL function through physical activity interventions, interventions targeting handwriting and medication adherence, and individualized occupational therapy interventions.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects almost 1 million people in the United States (Marras et al., 2018). PD is associated with motor and nonmotor manifestations that can lead to progressive disability and restricted participation in meaningful occupations (Duncan & Earhart, 2011; Shulman et al., 2008). Occupational therapy practitioners are well suited to address the occupational performance problems that result from PD.

One occupational domain negatively affected by PD is instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs; Choi et al., 2019; Foster, 2014). According to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (3rd ed.; OTPF–3; American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2014), IADLs are complex activities that support daily life in the home and community and include caring for others, communication management, driving and community mobility, financial management, health management and maintenance, home establishment and management, meal preparation and cleanup, religious and spiritual activities, safety and emergency maintenance, and shopping. Studies have found PD-related limitations in a variety of IADLs, including driving, financial management, medication management, shopping, and household management, even very early in the disease course (Crizzle et al., 2012; Foster, 2014; Hariz & Forsgren, 2011; Kudlicka et al., 2018; Pirogovsky et al., 2014). IADL limitations in people with PD are associated with withdrawal from everyday activities and reduced quality of life (Klepac et al., 2008; Kudlicka et al., 2018). These findings highlight the necessity and importance of interventions to address IADL function among people with PD.

Occupational therapy practitioners should be prepared to address IADLs as part of an overall plan of care for clients with PD. The purpose of this review is to assist practitioners in making evidence-based decisions regarding such interventions. A prior systematic review of occupational therapy–related interventions for adults with PD found that physical activity, external cues, and self-management and cognitive–behavioral approaches can benefit motor skills, basic activities of daily living, and health-related quality of life in this population (Foster et al., 2014). When that review was published, IADL function had rarely, if ever, been reported as an intervention target or outcome, but the authors of the review noted that such work was emerging. Therefore, our objective was to systematically search for, assess, and synthesize the new evidence on occupational therapy interventions for people with PD with a specific focus on IADLs (see Boone et al., 2021, and Doucet et al., 2021, for the updated systematic reviews addressing other occupational outcomes). We used the following focused question: What is the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions within the scope of occupational therapy to improve or maintain performance and participation in IADLs for adults with PD?

Method

This systematic review was supported and funded by the AOTA Evidence-Based Practice Program. It was conducted following an a priori review protocol and Cochrane Collaboration methodology (Higgins et al., 2019) and is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2010). AOTA staff, a research methodologist (Elizabeth G. Hunter), a medical librarian, and external experts developed the research question and search terms.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between January 2011 and December 2018 were eligible (the prior systematic review included articles published between January 2003 and May 2011; Foster et al., 2014). We included studies providing Level 1b, 2b, and 3b evidence (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2011; Table 1). We excluded systematic reviews and meta-analyses, Level 4 or 5 studies, protocols, dissertations and theses, presentations, abstracts, and commentaries and editorials. Systematic reviews were evaluated, and pertinent articles from them were included in the review. Included studies involved adults (age 18+) with PD; studies that did not report results specifically for participants with PD were excluded.

Table 1.

Levels of Evidence

| Level | Type of Evidence |

| 1a | Systematic review of homogeneous (e.g., similar population or intervention) RCTs with or without meta-analysis |

| 1b | Well-designed individual RCT (not a pilot or feasibility study with a small sample size) |

| 2a | Systematic review of cohort studies |

| 2b | Individual prospective cohort study, low-quality RCT (e.g., <80% follow-up or low number of participants, pilot or feasibility study), ecological study, two-group, nonrandomized study |

| 3a | Systematic review of case–control studies |

| 3b | Individual retrospective case–control study, one-group, nonrandomized pretest–posttest study, cohort study |

| 4 | Case seriesa (or low-quality cohort or case–control study) |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal |

Note. RCT = randomized controlled trial. Adapted from The Oxford 2009 Levels of Evidence, by Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2009. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxfordcentre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

Interpreted as any single-subject design (e.g., single-case experimental design, case study).

We included studies of interventions within the scope of occupational therapy practice with outcomes of interest related to IADL performance and participation, with IADLs defined according to the OTPF–3. Measures could include performance-based assessments, questionnaires, questions, or objective measures (e.g., activity monitor). Health-related quality of life and other functional outcome measures were not included unless IADL-specific data from them were reported.

Study Selection

A medical librarian conducted the search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, OTseeker, and Cochrane databases for articles published from January 2011 to December 2018 (see the supplemental material, available online with this article at https://ajot.aota.org). The research methodologist conducted an initial review of the search results and eliminated duplicates and other articles not meeting the inclusion criteria (e.g., wrong year, non-PD participants). Three reviewers (Erin R. Foster, Lisa G. Carson, and Jamie Archer) then reviewed the output to identify studies for inclusion. At least two reviewers independently screened each citation and abstract to identify studies for full-text review. The team met to rectify discrepancies and determine which full-text articles to retrieve.

At least two reviewers then independently reviewed each full-text article, and again the team met to rectify discrepancies before making the final determination for inclusion. Systematic review articles were searched to identify individual studies that met eligibility criteria, which then went through the above-described review method (n = 263 additional records). Forward and backward citation searches of included articles were completed to identify additional studies. One study that had not been returned in the initial search results was identified during full-text review (Nackaerts et al., 2016). Decisions were reviewed by AOTA staff and the research methodologist for quality control. Reviewers independently extracted data related to level of evidence, study design, participants, inclusion criteria, intervention setting, intervention and control descriptions, and IADL outcome measures and results from the included studies.

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Two reviewers (Foster and Carson) initially assessed study risk of bias; their results were then reviewed by the research methodologist (Hunter). The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized trials (Higgins et al., 2016), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (n.d.) risk-of-bias tool was used for noncontrolled research studies.

Strength of Evidence Grading

The strength of evidence within a theme was determined by number of studies, level of evidence, risk-of-bias evaluation, and significance of outcomes (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2018). Strong strength of evidence includes two or more Level 1b studies with low risk of bias and consistent results. Moderate strength of evidence includes at least one Level 1b study with low risk of bias or multiple Level 2b or 3b studies with low to moderate risk of bias providing evidence sufficient to determine effects on outcomes but with confidence constrained by number and size of studies, level of evidence, risk of bias, or inconsistent results. Low strength of evidence indicates insufficient evidence to assess effects on outcomes because of a variety of factors (e.g., small samples, inconsistent results, design or methodological flaws).

Results

We identified 22 articles describing 9 Level 1b, 9 Level 2b, and 4 Level 3b studies for inclusion in the final synthesis. Figure 1 depicts the flowchart for study selection. We organized the studies into four themes on the basis of primary type or focus of intervention: physical activity, specific IADL-focused, cognitive rehabilitation, and individualized occupational therapy interventions. The physical activity and specific IADL-focused themes were subdivided on the basis of study outcome. Table A.1 in the Appendix summarizes each study within the themes, and Tables A.2 and A.3 provide the risk-of-bias evaluations of included studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for studies included in the systematic review.

Note. IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living; OT = occupational therapy; PD = Parkinson’s disease. Figure format from “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement,” by D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, & D. G. Altman; PRISMA Group, 2010, International Journal of Surgery, 8, 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

Physical Activity Interventions

Thirteen studies provide evidence related to the effect of physical activity interventions on IADL function in people with PD. Two studies (Pretzer-Aboff et al., 2011; van Nimwegen et al., 2013) used general or lifestyle “physical activity,” defined by the World Health Organization (WHO; 2018) as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” (p. 14), including activities undertaken while working, engaging in recreational pursuits, and carrying out household chores. The remaining 11 studies used “exercise,” defined as physical activity that is “planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive” and that aims to improve or maintain physical fitness (WHO, 2018, p. 98). All studies used community- or home-based interventions. Three classes of IADL-related outcomes were assessed in these studies: physical activity level (11 studies), reported IADL function (3 studies), and reported IADL participation (1 study).

Physical Activity Level

Physical activity level was the primary outcome for 5 studies (Colón-Semenza et al., 2018; Nakae & Tsushima, 2014; Pretzer-Aboff et al., 2011; Ridgel et al., 2016), including 1 Level 1b RCT with low risk of bias (van Nimwegen et al., 2013). The interventions in these studies ranged from 8 wk to 2 yr in duration and, in addition to prescribing physical activity or exercise, incorporated health behavior change components to promote increased engagement in physical activity. Physical activity level was a secondary outcome in 6 studies (Cheung et al., 2018; Demonceau et al., 2017), including 4 Level 1b RCTs with low to moderate risk of bias (Canning et al., 2015; Goodwin et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014; Reuter et al., 2011). These studies used exercise interventions ranging from 10 wk to 6 mo in duration such as resistance, aerobic and flexibility exercise, balance training, walking, Nordic walking, yoga, and tai chi. Regardless of primary intervention target and intervention characteristics (e.g., type, dose), almost all studies found significant treatment-related improvements in physical activity levels during the interventions, immediately postintervention, or at follow-up using a variety of standardized and unstandardized questionnaires or activity trackers or monitors as outcome measures. Thus, strong strength of evidence supports physical activity interventions to increase physical activity levels (measured by, e.g., steps per day, actigraphy, reported physical activity).

Reported IADL Function

Three studies assessed the effect of exercise interventions on reported IADL function (Colón-Semenza et al., 2018; Nakae & Tsushima, 2014; Nascimento et al., 2014). Only 1 of these studies, which used a more comprehensive exercise program with a higher dose than the others, found significant treatment-related improvements (Nascimento et al., 2014). Because of the small number of lower level studies with moderate risk of bias and inconsistent results, low strength of evidence is available that physical activity interventions can improve reported IADL function.

Reported IADL Participation

One Level 1b RCT with low risk of bias found significant treatment-related improvements in reported IADL participation during a 12-mo community-based tango dance intervention (Foster et al., 2013). This study provides moderate strength of evidence that participation in tango dance classes can increase IADL participation.

Specific IADL-Focused Interventions

Four studies provide evidence for interventions targeting a specific IADL in people with PD. Two IADLs were the target of intervention in these studies: handwriting (3 studies) and medication adherence (1 study).

Handwriting

Three studies, including 1 Level 1b RCT with low risk of bias (Collett et al., 2017), tested the effect of handwriting training on handwriting function (Nackaerts et al., 2016; Ziliotto et al., 2015). The interventions had different treatment components (e.g., hand exercises, writing with external cues); ranged in intensity, frequency, and duration (e.g., 30–90 min sessions, 1–5×/wk, over 6 wk to 6 mo); and had different delivery methods (e.g., workbook, in person). However, they all resulted in significant improvements in handwriting as assessed by self-report (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Item 2.7) or objective measures (e.g., writing amplitude, surface area, superior margin). Therefore, strong strength of evidence supports handwriting training.

Medication Adherence

One Level 1b RCT with moderate risk of bias found significant improvements in medication adherence after 7 weekly 1:1 home-based sessions using a cognitive–behavioral approach with care partner participation (Daley et al., 2014). Thus, moderate strength of evidence supports medication adherence therapy.

Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions

Three studies provide evidence related to cognitive rehabilitation interventions to address IADL function in people with PD. Two studies used a cognitive process training approach in people with PD who did not have dementia; the approach involved structured practice on tasks designed to target and improve specific cognitive functions (e.g., working memory, processing speed; Disbrow et al., 2012; París et al., 2011). Neither found significant treatment-related improvements in objective or reported IADL function. One study used a functional goal–oriented strategy training approach with people with PD-related dementia; this approach involved the use of strategies to compensate for or reduce the impact of cognitive impairment and improve everyday activity function (Hindle et al., 2018). This study found no significant treatment-related improvements in informant-reported IADL function. Thus, low strength of evidence is available that cognitive rehabilitation may benefit IADL function in people with PD.

Individualized Occupational Therapy Interventions

Two Level 1b RCTs provide evidence related to guidelines-based, comprehensive, individualized occupational therapy interventions to address IADL function in people with PD. A large, multicenter, pragmatic RCT tested occupational therapy based on the U.K. National Health Service guidelines that was provided in an average of four 1-hr sessions over 8 wk in community and outpatient settings (Clarke et al., 2016). The intervention focused on transfers, dressing, grooming, sleep, fatigue, indoor mobility, household tasks, and other environmental issues and had no significant effect on clinician-rated IADL performance. A multicenter assessor-blind RCT tested occupational therapy following the Dutch national practice guidelines that was provided for an average of eight 1-hr sessions over 10 wk in the home (Sturkenboom et al., 2014). The intervention included self-management, coaching, and skills training for compensatory strategies, task and routine simplification, adaptive equipment, and environmental modification and had significant effects on reported IADL participation but not on IADL performance. Together, these studies provide moderate strength of evidence that comprehensive individualized occupational therapy interventions can improve IADL participation but low strength of evidence that it can improve IADL performance.

Discussion

This systematic review is part of an update of a prior systematic review of occupational therapy–related interventions for people with PD (Foster et al., 2014), but it focuses specifically on IADL function as an outcome. It revealed four general categories of interventions used to address IADL function in PD: physical activity, specific IADL-focused, cognitive rehabilitation, and individualized occupational therapy interventions. Strong strength of evidence indicates that physical activity interventions can increase physical activity levels and that handwriting interventions can improve handwriting. Moderate strength of evidence indicates that tango dance classes and individualized home-based occupational therapy can increase IADL participation and that medication adherence therapy can improve medication adherence. Low strength of evidence is available for physical activity interventions and cognitive rehabilitation to improve general IADL function. Our results are consistent with those of the prior review, which also found that interventions focused on physical activity or that incorporate external cues (e.g., Nackaerts et al., 2016) and self-management or cognitive–behavioral approaches (e.g., Daley et al., 2014; Sturkenboom et al., 2014; van Nimwegen et al., 2013) can benefit people with PD, and the current review extends these findings specifically to IADL function.

Physical activity, specifically exercise, can improve motor and nonmotor function and quality of life in people with PD; however, these benefits are likely derived only if the person engages in adequate levels of physical activity in daily life. Thus, occupational therapy practitioners have a role in helping people with PD incorporate and maintain physical activity in their daily routine as an aspect of health management and maintenance. This systematic review shows that education, peer mentoring, social support and interaction, goal setting, action and coping planning, and activity tracking may aid this process. In addition, social forms of exercise such as dance may stimulate increased participation in IADLs and other daily activities.

Interventions that focus on a specific problematic IADL, namely handwriting and medication adherence, appear to improve performance. Occupational therapy practitioners can provide hand exercises, writing activities, and external cues for increased writing amplitude (e.g., colored visual target zones) to improve subjective and objective handwriting ability. In addition to addressing actual performance of medication management activities in the context of the client’s life (AOTA, 2017), findings suggest that to improve medication management in people with PD, occupational therapy practitioners should involve the care partner, assess the client’s medication regimen, understand their perceptions of medication use, and help them problem solve practical and attitudinal barriers to adherence (Daley et al., 2014). Improvements in specific IADLs from a focused intervention may translate to improved overall occupational performance and participation in people with PD, but this possibility remains to be tested.

Because of the limited number of studies and lack of significant findings, low strength of evidence is available for the effect of cognitive rehabilitation interventions. Although cognitive process training can improve cognitive test performance among people with PD who do not have dementia, evidence supporting the translation of these improvements to IADL function is lacking (Disbrow et al., 2012; Leung et al., 2015; París et al., 2011). Notably, the functional goal–oriented cognitive strategy training approach resulted in improved goal attainment in participants with PD-related dementia (Hindle et al., 2018), but the goals may not have been IADL related. More research is needed in this area because cognitive impairment is related to reduced IADL function in people with PD (e.g., Cahn et al., 1998; Pirogovsky et al., 2014) and functional cognition is a critical domain of concern for occupational therapy practitioners (Giles et al., 2020).

The evidence is mixed for the effect of individualized occupational therapy interventions. Tailored home-based occupational therapy improved IADL participation (Sturkenboom et al., 2014), but no significant improvements were found in IADL performance (reported and observed) in either of the large RCTs included in this review (Clarke et al., 2016; Sturkenboom et al., 2014). In addition to increased IADL participation, Sturkenboom et al. (2014) reported improvement on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), but they did not specify whether or how many COPM goals were IADL related. The small number of studies and differences between them, such as intervention approach, dose, usual care versus best practice, and setting, limit firm conclusions. The findings within this theme do suggest that occupational therapy assessment should include measures of IADL performance and IADL participation, which are important and dissociable constructs, and that clients with PD need moderate to high doses of treatment (e.g., ≥8 sessions, ≥10 wk) to experience benefit.

Although the evidence base has increased greatly since the prior systematic review (Foster et al., 2014), the number of intervention studies explicitly addressing IADL outcomes aside from physical activity levels is still small. More research is needed on the effects of physical activity interventions on general IADL function, interventions targeting other problematic IADLs (e.g., financial management), comprehensive individualized occupational therapy, and cognitive rehabilitation. In addition, reporting of IADL-specific outcomes is limited. For example, many studies used outcome measures that include IADL items (e.g., Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire–39), but the IADL items represent a small proportion of the entire scale or were not reported separately. Similarly, several studies used standardized measures of change in individualized treatment-related goals (e.g., Goal Attainment Scaling, COPM, Bangor Goal-Setting Interview), which is consistent with best practice principles of client-centeredness and tailoring. However, these outcomes were not included in this review because it was unclear whether the goals were IADL related. Because the use of these clinically meaningful measures is increasing in PD research (e.g., Foster et al., 2018; Hindle et al., 2018; Reuter et al., 2012; Sturkenboom et al., 2014; Vlagsma et al., 2018), a future systematic review on the effect of occupational therapy–related interventions on individualized goals in people with PD may be warranted.

Although we present four intervention themes, we note that these categories are not mutually exclusive. Many of the studies tested complex interventions that involved simultaneous application of different and interacting treatment components; multiple ingredients, targets, and outcomes; and flexibility and tailoring (Craig et al., 2008; Hart et al., 2019; Whyte, 2014; Whyte & Hart, 2003) and thus overlapped with one another in different ways. For example, studies in the physical activity (e.g., Pretzer-Aboff et al., 2011; van Nimwegen et al., 2013), specific IADL-focused (Daley et al., 2014), and individualized occupational therapy (Sturkenboom et al., 2014) themes used self-management or cognitive–behavioral strategies; a handwriting study used exercise (Collett et al., 2017); and both of the individualized occupational therapy studies (Clarke et al., 2016; Sturkenboom et al., 2014) incorporated task-specific training. As the field moves toward better specification of rehabilitative interventions, researchers’ ability to evaluate, synthesize, and compare treatments and treatment components and their effectiveness in addressing IADL function in people with PD will be enhanced (Fasoli et al., 2019; Zanca et al., 2019).

Limitations

The precision of our findings was limited by the small number and heterogeneity of studies targeting IADLs. Although a thorough search of research databases was conducted and standardized methodology was followed, it is possible that pertinent articles were missed. Additionally, this review was limited to English-language articles and ended in December 2018, which may have resulted in the exclusion of important articles. Finally, there is a chance that publication bias existed and that studies without positive findings were less often published and thus missed by this review.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice

The findings of this systematic review have the following implications for occupational therapy practice with people with PD:

Assessments should include measures of IADL performance and IADL participation.

Occupational therapy practitioners can promote engagement in physical activity by using health behavior change techniques.

Social physical activity may stimulate increased participation in IADLs.

Occupational therapy practitioners should consider task-specific training for problematic IADLs. Handwriting can be addressed through upper extremity strengthening, writing activities, and external cues. Medication management interventions should incorporate a cognitive–behavioral approach and care partner participation.

Conclusion

Occupational therapy interventions can improve health management and maintenance (i.e., physical activity levels, medication management), handwriting, and IADL participation for people with PD. Further research is needed on cognitive rehabilitation. This review is limited by the small number of studies that specifically addressed IADL function in treatment and as an outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deborah Lieberman, Hillary Richardson, and Kim Lipsey for their guidance and support during the process of this review. Preliminary results from this review were presented at the 2020 American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Virtual Conference.

Elizabeth G. Hunter works as a research methodologist for the AOTA Evidence-Based Practice Project. This did not influence the outcomes of this review. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

AOTA provided support for this work. Erin R. Foster is funded by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging [NIA] Grant R21AG063974, NIA Grant R01AG065214, and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01DK064832) and the Advanced Research Center of the Greater St. Louis chapter of the American Parkinson Disease Association.

Appendix. Supplemental Tables.

Appendix. Evidence and Risk-of-Bias Tables for the Systematic Review

Table A.1.

Evidence Table for the Systematic Review of Interventions Within the Scope of Occupational Therapy Practice for IADLs for Adults With PD

| Author/Year | Level of Evidence/Study Design and Risk of Bias/Participants/Inclusion Criteria/Setting | Intervention and Control | Outcome Measures | Results |

| Physical Activity Intervention | ||||

| Canning et al. (2015) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by a habitual physical activity questionnaire measuring hr/wk of exercise at postintervention | No significant treatment-related improvements were found for the entire sample (M difference = 0.7 hr/wk, 95% CI [–0.2, 1.6], p = .15). Post hoc subgroup analysis showed a significant increase in habitual exercise among participants with lower disease severity (M difference = 1.5 hr/wk, 95% CI [0.03, 3.05], p = .046) but not higher disease severity (M difference = –0.4 hr/wk, 95% CI [–1.2, 0.5], p = .38). |

| Cheung et al. (2018) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by the LAPAQ at postintervention | The intervention group had significantly lower physical activity postintervention compared with the control group (M difference = 3,187, 95% CI [790, 5,584]) and baseline (M difference = –3,138, 95% CI [–6,252, −24]). |

| Colón-Semenza et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

No significance tests were performed because of the small sample size. The mentee group had a 31% increase in average steps/day (4 of 5 mentees’ increases exceeded the minimally clinically important difference of 779 steps/day), a 42% increase in active min/wk, and a 20% increase in frequency of achieving 30 fairly or very active minutes. LLFDI score changes did not exceed the minimal detectable change of 11.62 points. |

| Demonceau et al. (2017) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by the PASS postintervention | The strength and aerobic training groups’ PASS scores improved more than the control group’s (strength, d = 0.34, 95% CI [–0.17, 1.25]; aerobic, d = 0.54, 95% CI [–0.38, 1.06]; control, d = –0.10, 95% CI [–0.82, 0.61]; interaction p = .022). |

| Foster et al. (2013) |

|

|

IADL participation assessed by the ACS Current Instrumental Activities, % Instrumental Activities Retained, and New Instrumental Activities scores at 3, 6, and 12 mo after baseline assessment | Significant intervention-related improvements were found in % Instrumental Activities Retained, which increased in the tango group from 76% at baseline to 87% at 3 mo before declining to 81% at 12 mo (p = .02), whereas the control group remained at 80% (p = .70). No significant intervention-related improvements were found for Current and New Instrumental Activities (data not reported). |

| Goodwin et al. (2011) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by the Phone-FITT (household and recreational physical activity) at postintervention and 10-wk follow-up | The intervention group reported significantly higher recreational physical activity levels than the control group at postintervention (M difference = 0.43, 95% CI [–0.05, 0.90], p = .08) and follow-up (M difference = 0.61, 95% CI [0.12, 1.10], p = .02). No significant effects were found for household physical activity levels (postintervention and follow-up, M difference = –0.25, 95% CI [–0.7, 0.19], p = .26). |

| Li et al. (2014) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by self-report of “continuing to exercise” after the intervention (defined as exercising ≥2×/wk for ≥30 min per session) at 3 mo postintervention | 63% (n = 123) of all participants reported continuing to exercise. Significantly more participants in the tai chi group (n = 47) continued to exercise than in the resistance training (n = 41) and stretching (n = 35) groups (p < .05). |

| Nakae & Tsushima (2014) |

|

|

|

Participants spent a significantly lower percentage of their time lying (36.7 vs. 29.3, p < .05) and sitting (24.0 vs. 31.9, p < .05) per day postintervention compared with preintervention. No significant change was found in TMIG Index of Competence scores (data not reported). |

| Nascimento et al. (2014) |

|

|

IADL function assessed by the Brazilian version of the PIAQ at postintervention | The exercise group’s PIAQ scores improved (% improvement = 24.6%), whereas the control group’s worsened (% improvement = –17.5%) from pre- to postintervention, F(1, 23) = 14.6, p = .001. |

| Pretzer-Aboff et al. (2011) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by the YPAS at 2, 6, and 12 mo after baseline | There were significant increases from baseline to 12 mo in hours spent exercising, F(1, 24) = 4.95, p = .004; energy expended, F(2, 43) = 4.32, p = .017; and hours spent in all physical activities, F(3, 60) = 6.06, p < .001. |

| Reuter et al. (2011) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by an activity log the last week of the intervention and a phone interview (e.g., Do you continue the training you practiced during the study? How often do you exercise per week?) 6 mo after intervention completion | At the end of the training period, the Nordic walking and walking groups spent significantly more time than the flexibility and relaxation group doing heavy exertion (9.4 and 6.3 hr/wk vs. 3.8 hr/wk), F(2, 87) = 11.25, p < .001, and less time sitting (5.6 and 5.7 hr/day vs. 8.9 hr/day), F(2, 87) = 14.22, p < .001. 6 mo after study completion, 100% of Nordic walking participants continued Nordic walking, 60% of the walking group continued walking and 30% switched to Nordic walking, and 50% of the flexibility and relaxation group continued their training regimen. |

| Ridgel et al. (2016) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by the IPAQ at 12 wk postintervention and 24-wk follow-up | A significant intervention-related effect was found; the EXCEED group showed a 34% increase in physical activity from Wk 12 to Wk 24, whereas the SGE group showed a 32% reduction in activity over this period (p = .03). The EXCEED group had 56% more physical activity than the SGE group at 24 wk (1,472.7 MET min/wk vs. 646.5 MET min/wk). |

| van Nimwegen et al. (2013) |

|

|

Physical activity level assessed by the LAPAQ (primary outcome), an activity diary, and an ambulatory activity monitor at 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo (6- and 24-mo data averaged for analysis) | No significant treatment-related improvements were found on the LAPAQ (group difference = 7%, 95% CI [–3%, 17%], p = .19). The ParkFit group had significantly greater increases in physical activity levels compared with the control group according to the activity diary (difference = 30%, 95% CI [17%, 45%], p < .001) and activity monitor (difference = 12%, 95% CI [7%, 16%], p < .001). |

| Specific IADL-Focused Interventions | ||||

| Collett et al. (2017) |

|

|

|

A significant improvement was found for the handwriting training group in perceived handwriting difficulty (OR = 0.55, 95% CI [0.34, 0.91], p = .02). Moderate effect sizes of the handwriting intervention were found for writing amplitude (total area, d = 0.32, 95% CI [–0.11, 0.70], p = .13), but there were small or no effects for writing speed or progressive reduction (d ≤ 0.11). |

| Daley et al. (2014) |

|

|

Medication adherence assessed by the MMAS–4 at 7 and 12 wk postrandomization (primary outcome, 12 wk) | Significant treatment-related improvements were found at both 7 and 12 wk; more people had improved MMAS–4 scores in the adherence therapy group compared with the control group (at 7 wk, 64.8% vs. 26.3%, OR = 6.1, 95% CI [2.2, 16.4]; at 12 wk, 60.5% vs. 15.8%, OR = 8.2, 95% CI [2.8, 24.3]). |

| Nackaerts et al. (2016) | Level 2b RCT; moderate risk of bias N = 38 (M age = 63; 61% male) Intervention group, n = 18 Control group, n = 20 Inclusion Criteria H&Y Stage I–III, right-handed as determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory; score ≥1 on Item 2.7 of the MDS–UPDRS, MMSE score ≥24, no visual impairments, no upper limb problems that would impede handwriting, no deep brain stimulation Intervention Setting Home, Belgium |

Intervention Intensive writing amplitude training consisting of pen-and-paper writing and exercises on a touch-sensitive tablet with colored target zones and gradual progression of difficulty, 30 min of practice 5 days/wk for 6 wk, plus weekly observations Control Stretch and relaxation exercises provided on a DVD, 30 min of practice 5 days/wk for 6 wk, plus weekly observations |

Handwriting amplitude assessed by a touch-sensitive tablet and paper-and-pencil (SOS) test at postintervention and 6-wk follow-up | Significant treatment-related improvements were found for various measures of handwriting amplitude assessed by the tablet; the intervention group had increased amplitude at postintervention and follow-up compared with the control group and with baseline (ps ≤ .05). The intervention group had increased writing size on the SOS test at postintervention compared with the control group, F = 3.69, p = .034, and with baseline (p = .037). |

| Ziliotto et al. (2015) |

|

|

Handwriting amplitude, progressive reduction, direction, surface area, superior margin, force exerted, and velocity assessed using a written phrase postintervention | At postintervention, the handwriting group had significantly increased writing amplitude, surface area, and superior margin compared with the control group and with baseline (ps ≤ .02). No significant treatment-related effects were found in progressive reduction, direction, force exerted, or velocity (data not reported). |

| Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions | ||||

| Disbrow et al. (2012) |

|

|

IADL performance assessed by the TIADL postintervention | No significant treatment-related improvements were found on the TIADL (data not reported). |

| Hindle et al. (2018) |

|

|

IADL function assessed by the FAQ at 6 mo postrandomization | No significant treatment-related improvements were found on the FAQ (data not reported). |

| París et al. (2011) |

|

|

Difficulty with everyday cognition (including some IADLs) assessed by the CDS postintervention | No significant treatment-related improvements were found on the CDS (d = 0.09, F = 0.06, p = .81). |

| Individualized Occupational Therapy Interventions | ||||

| Clarke et al. (2016) |

|

|

IADL function assessed by the NEADL Kitchen Activity and Domestic Tasks domains at 3, 9, and 15 mo postrandomization (primary outcome, 3 mo) | No significant treatment-related improvements were found for the NEADL total score (difference = 0.5, 95% CI [–0.74, 1.7], p = .41) or any of the NEADL domains (Kitchen Activities difference = 0.005, 95% CI [–0.3, 0.3], p = .97; Domestic Tasks difference = 0.5, 95% CI [–0.06, 1.0], p = .08) at 3 mo or across all time points. |

| Sturkenboom et al. (2014) |

|

|

|

The intervention group had significantly better ACS % Instrumental Activities Retained compared with the control group after the intervention (M difference = 5.9%, 95% CI [8%, 10%], p = .006). There was no effect for the PRPP (M difference = 0.8%, 95% CI [–7.5, 9.0], p = .848). |

Note. ACE–III = Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–III; ACS = Activity Card Sort; ADLs = activities of daily living; CDS = Cognitive Difficulties Scale; CI = confidence interval; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire; FOG = Freezing of Gait Questionnaire; GDS–15 = 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale; H&Y = Hoehn & Yahr; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living; IPA = Impact on Participation and Autonomy Questionnaire; IPAQ = International Physical Activity Questionnaire; LAPAQ = Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam Physical Activity Questionnaire; LLFDI = Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument; MADRS = Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MDS–UPDRS = Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; MET = metabolic equivalent; MMAS–4 = Morisky Medication Adherence Scale–4; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NEADL = Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale; OR = odds ratio; OT = occupational therapy; PASS = Physical Activity Status Scale; PD = Parkinson’s disease; PDD = Parkinson’s disease dementia; PIAQ = Pfeffer Instrumental Activities Questionnaire; PRPP = Perceive, Recall, Plan, Perform; PT = physical therapist/therapy; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SOS = Systematic Screening of Handwriting Difficulties; TIADL = Timed Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Tasks; TMIG = Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology; WAIS–III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd ed.; YPAS = Yale Physical Activity Survey.

Citation: Foster, E. R., Carson, L. G., Archer, J., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Occupational therapy interventions for instrumental activities of daily living for adults with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review (Table A.1). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 7503190030. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.046581

Table A.2.

Risk-of-Bias Table for Randomized and Nonrandomized Controlled Trials

| Citation | Selection Bias | Performance Bias | Detection Bias | Attrition Bias: Incomplete Outcome Data | Reporting Bias: Selective Reporting | Overall Risk of Bias Assessment | ||||

| Random Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Baseline Differences Between Intervention Groups | Blinding of Participants During Trial | Blinding of Study Personnel During Trial | Blinding of Outcome Assessment: Self-Reported Outcomes | Blinding of Outcome Assessment: Objective Outcomes | ||||

| Physical Activity Interventions | ||||||||||

| Canning et al. (2015) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | L |

| Cheung et al. (2018) | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | L |

| Demonceau et al. (2017) | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | + | + | M |

| Foster et al. (2013) | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | L |

| Goodwin et al. (2011) | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | M |

| Li et al. (2014) | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | L |

| Nascimento et al. (2014) | – | – | ? | – | – | – | + | – | + | M |

| Reuter et al. (2011) | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | M |

| Ridgel et al. (2016) | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | M |

| van Nimwegen et al. (2013) | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | L |

| Specific IADL-Focused Interventions | ||||||||||

| Collett et al. (2017) | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | L |

| Daley et al. (2014) | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | M |

| Nackaerts et al. (2016) | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | + | + | M |

| Ziliotto et al. (2015) | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | + | M |

| Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions | ||||||||||

| Hindle et al. (2018) | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | L |

| París et al. (2011) | + | ? | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | L |

| Individualized Occupational Therapy Interventions | ||||||||||

| Clarke et al. (2016) | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | M |

| Sturkenboom et al. (2014) | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | L |

Note. Categories for risk of bias: + = low risk of bias; ? = unclear risk of bias; – = high risk of bias. IADL = instrumental activity of daily living; L = low overall risk of bias (0–3 minuses); M = moderate overall risk of bias (4–6 minuses). Risk-of-bias table format adapted from “Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies,” by J. P. T. Higgins, D. G. Altman, and J. A. C. Sterne, in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0), by J. P. T. Higgins and S. Green (Eds.), March 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Copyright © 2011 by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Citation: Foster, E. R., Carson, L. G., Archer, J., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Occupational therapy interventions for instrumental activities of daily living for adults with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review (Table A.2). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 7503190030. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.046581

Table A.3.

Risk-of-Bias Table for Noncontrolled Studies

| Citation | Study Question or Objective Clear | Eligibility or Selection Criteria Clearly Described | Participants Representative of Real-World Patients | All Eligible Participants Enrolled | Sample Size Appropriate for Confidence in Findings | Intervention Clearly Described and Delivered Consistently | Outcome Measures Prespecified, Defined, Valid and Reliable, and Assessed Consistently | Assessors Blinded to Participant Exposure to Intervention | Loss to Follow-up After Baseline ≤20% | Statistical Methods Examine Changes in Outcome Measures From Before to After Intervention | Outcome Measures Were Collected Multiple Times Before and After Intervention | Overall Risk of Bias Assessment |

| Physical Activity Interventions | ||||||||||||

| Colón-Semenza et al. (2018) | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | M |

| Nakae & Tsushima (2014) | Y | Y | Y | NR | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | M |

| Pretzer-Aboff et al. (2011) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions | ||||||||||||

| Disbrow et al. (2012) | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | Y | Y | N | NR | Y | N | M |

Note. N = no; NR = not reported; Y = yes. Adding Yes scores for each item and dividing by 11 yields an overall risk-of-bias rating: L = low overall risk (76%–100%), M = moderate overall risk (26%–75%). Risk-of-bias tool adapted from Quality Assessment Tool for Before–After (Pre–Post) Studies With No Control Group, by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, n.d. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Citation: Foster, E. R., Carson, L. G., Archer, J., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Occupational therapy interventions for instrumental activities of daily living for adults with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review (Table A.3). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 7503190030. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.046581

Supplemental Material

Search Strategy for CINAHL

S1: TI (parkinson OR parkinsons OR parkinsonism OR “parkinson's disease”) OR AB (parkinson OR parkinsons OR parkinsonism OR “parkinson's disease”)

S2: TI (“best practices” OR “case control” OR “case report” OR “case series” OR “clinical guideline” OR “clinical guidelines” OR “clinical trial” OR cohort OR “comparative study” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “cross over” OR “cross sectional” OR “double blind” OR epidemiology OR “evaluation study” OR “evidence based” OR “evidence synthesis” OR “feasibility study” OR “follow up” OR “health technology assessment” OR intervention OR longitudinal OR “main outcome measure” OR “meta analysis” OR “multicenter study” OR “observational study” OR “outcome and process assessment” OR “practice guideline” OR “practice guidelines” OR prospective OR “random allocation” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “randomized controlled trials” OR retrospective OR sampling OR “single subject design” OR “standard of care” OR “systematic literature review” OR “systematic review” OR “treatment outcome” OR “validation study”) OR AB (“best practices” OR “case control” OR “case report” OR “case series” OR “clinical guideline” OR “clinical guidelines” OR “clinical trial” OR cohort OR “comparative study” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “cross over” OR “cross sectional” OR “double blind” OR epidemiology OR “evaluation study” OR “evidence based” OR “evidence synthesis” OR “feasibility study” OR “follow up” OR “health technology assessment” OR intervention OR longitudinal OR “main outcome measure” OR “meta analysis” OR “multicenter study” OR “observational study” OR “outcome and process assessment” OR “practice guideline” OR “practice guidelines” OR prospective OR “random allocation” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “randomized controlled trials” OR retrospective OR sampling OR “single subject design” OR “standard of care” OR “systematic literature review” OR “systematic review” OR “treatment outcome” OR “validation study”)

S3: TI (Activities OR “assistive technology” OR “assistive devices” OR “communication technology” OR “assistive technology” OR “assistive equipment” OR cognition OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR “community care” OR “community programs” OR “disease management” OR education OR “emotional regulation” OR environment OR “environmental modification” OR “energy conservation” OR exercise OR “executive function” OR falls OR “fall prevention” OR fatigue OR “health literacy” OR “health maintenance” OR “health promotion” OR “health-care utilization” OR “home health” OR lifts OR mindfulness OR mobility OR “mobility equipment” OR neurorehabilitation OR “non-motor symptoms” OR “occupational therapy” OR pain OR positioning OR psychosocial OR “quality of life” OR rehabilitation OR scooters OR “self-management” OR services OR “social engagement” OR therapy OR treatment OR walkers OR “wellness programs” OR wheelchairs OR yoga OR telehealth OR “home modifications” OR leisure OR “physical activity”) OR AB (Activities OR “assistive technology” OR “assistive devices” OR “communication technology” OR “assistive technology” OR “assistive equipment” OR cognition OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR “community care” OR “community programs” OR “disease management” OR education OR “emotional regulation” OR environment OR “environmental modification” OR “energy conservation” OR exercise OR “executive function” OR falls OR “fall prevention” OR fatigue OR “health literacy” OR “health maintenance” OR “health promotion” OR “health-care utilization” OR “home health” OR lifts OR mindfulness OR mobility OR “mobility equipment” OR neurorehabilitation OR “non-motor symptoms” OR “occupational therapy” OR pain OR positioning OR psychosocial OR “quality of life” OR rehabilitation OR scooters OR “self-management” OR services OR “social engagement” OR therapy OR treatment OR walkers OR “wellness programs” OR wheelchairs OR yoga OR telehealth OR “home modifications” OR leisure OR “physical activity”)

S4: TI (“Activity therapy” OR “child care” OR “child rearing” OR “communication skills training” OR “computer literacy” OR “community mobility” OR cooking OR “daily activities” OR driving OR “emergency preparation” OR “energy conservation” OR “financial management” OR “financial skills” OR “food preparation” OR grandparent OR grandparents OR grandparenting OR “home maintenance” OR “home management” OR “household maintenance” OR “household management” OR “household security” OR housekeeping OR “instrumental activities” OR “instrumental activities of daily living” OR laundry OR “meal planning” OR “meal preparation” OR “medication management” OR “menu planning” OR “money management” OR pets OR “religious activities” OR “religious service attendance” OR routines OR safety OR “electronic security systems” OR shopping OR telephone OR transportation OR walking) OR AB (“Activity therapy” OR “child care” OR “child rearing” OR “communication skills training” OR “computer literacy” OR “community mobility” OR cooking OR “daily activities” OR driving OR “emergency preparation” OR “energy conservation” OR “financial management” OR “financial skills” OR “food preparation” OR grandparent OR grandparents OR grandparenting OR “home maintenance” OR “home management” OR “household maintenance” OR “household management” OR “household security” OR housekeeping OR “instrumental activities” OR “instrumental activities of daily living” OR laundry OR “meal planning” OR “meal preparation” OR “medication management” OR “menu planning” OR “money management” OR pets OR “religious activities” OR “religious service attendance” OR routines OR safety OR “electronic security systems” OR shopping OR telephone OR transportation OR walking)

S5: S3 OR S4

S6: S1 AND S2 AND S5

Citation: Foster, E. R., Carson, L. G., Archer, J., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Occupational therapy interventions for instrumental activities of daily living for adults with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review (Supplemental materials). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 7503190030. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.046581

Footnotes

Indicates studies included in the systematic review.

Contributor Information

Erin R. Foster, Erin R. Foster, PhD, OTD, OTR/L, is Assistant Professor, Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO; erfoster@wustl.edu

Lisa G. Carson, Lisa G. Carson, OTD, OTR/L, is Occupational Therapist, Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

Jamie Archer, Jamie Archer, MOT, OTR/L, is Occupational Therapist, Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO..

Elizabeth G. Hunter, Elizabeth G. Hunter, PhD, OTR/L, is Assistant Professor, Graduate Center for Gerontology, University of Kentucky, Lexington.

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Suppl. 1), S1–S48. 10.5014/ajot.2014.682006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2017). Occupational therapy’s role in medication management. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(Suppl. 2), 7112410025. 10.5014/ajot.2017.716S02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone, A. E., Henderson, W., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Role of occupational therapy in facilitating participation among caregivers of people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 7503190010. 10.5014/ajot.2021.046284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn, D. A., Sullivan, E. V., Shear, P. K., Pfefferbaum, A., Heit, G., & Silverberg, G. (1998). Differential contributions of cognitive and motor component processes to physical and instrumental activities of daily living in Parkinson’s disease. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology , 13, 575–583. 10.1016/S0887-6177(98)00024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Canning, C. G., Sherrington, C., Lord, S. R., Close, J. C., Heritier, S., Heller, G. Z., . . . Fung, V. S. (2015). Exercise for falls prevention in Parkinson disease: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology , 84, 304–312. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Cheung, C., Bhimani, R., Wyman, J. F., Konczak, J., Zhang, L., Mishra, U., . . . Tuite, P. (2018). Effects of yoga on oxidative stress, motor function, and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies , 4, 162. 10.1186/s40814-018-0355-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. M., Yoon, G. J., Jung, H. J., & Kim, B. C. (2019). Analysis of characteristics affecting instrumental activities of daily living in Parkinson’s disease patients without dementia. Neurological Sciences , 40, 1403–1408. 10.1007/s10072-019-03860-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Clarke, C. E., Patel, S., Ives, N., Rick, C. E., Dowling, F., Woolley, R., . . . Sackley, C. M.; PD REHAB Collaborative Group. (2016). Physiotherapy and occupational therapy vs no therapy in mild to moderate Parkinson disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurology , 73, 291–299. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Collett, J., Franssen, M., Winward, C., Izadi, H., Meaney, A., Mahmoud, W., . . . Dawes, H. (2017). A long-term self-managed handwriting intervention for people with Parkinson’s disease: Results from the control group of a Phase II randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation , 31, 1636–1645. 10.1177/0269215517711232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Colón-Semenza, C., Latham, N. K., Quintiliani, L. M., & Ellis, T. D. (2018). Peer coaching through mHealth targeting physical activity in people with Parkinson disease: Feasibility study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth , 6, e42. 10.2196/mhealth.8074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M.; Medical Research Council. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ , 337, a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crizzle, A. M., Classen, S., & Uc, E. Y. (2012). Parkinson disease and driving: An evidence-based review. Neurology , 79, 2067–2074. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182749e95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Daley, D. J., Deane, K. H. O., Gray, R. J., Clark, A. B., Pfeil, M., Sabanathan, K., . . . Myint, P. K. (2014). Adherence therapy improves medication adherence and quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical Practice , 68, 963–971. 10.1111/ijcp.12439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Demonceau, M., Maquet, D., Jidovtseff, B., Donneau, A. F., Bury, T., Croisier, J. L., . . . Garraux, G. (2017). Effects of twelve weeks of aerobic or strength training in addition to standard care in Parkinson’s disease: A controlled study. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine , 53, 184–200. 10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Disbrow, E. A., Russo, K. A., Higginson, C. I., Yund, E. W., Ventura, M. I., Zhang, L., . . . Sigvardt, K. A. (2012). Efficacy of tailored computer-based neurorehabilitation for improvement of movement initiation in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Research , 1452, 151–164. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, B. M., Franc, I., & Hunter, E. G. (2021). Interventions within the scope of occupational therapy to improve activities of daily living, rest, and sleep in people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75, 7503190020. 10.5014/ajot.2021.048314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R. P., & Earhart, G. M. (2011). Measuring participation in individuals with Parkinson disease: Relationships with disease severity, quality of life, and mobility. Disability and Rehabilitation , 33, 1440–1446. 10.3109/09638288.2010.533245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasoli, S. E., Ferraro, M. K., & Lin, S. H. (2019). Occupational therapy can benefit from an interprofessional rehabilitation treatment specification system. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 7302347010. 10.5014/ajot.2019.030189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E. R. (2014). Instrumental activities of daily living performance among people with Parkinson’s disease without dementia. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 68, 353–362. 10.5014/ajot.2014.010330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E. R., Bedekar, M., & Tickle-Degnen, L. (2014). Systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational therapy–related interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 68, 39–49. 10.5014/ajot.2014.008706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Foster, E. R., Golden, L., Duncan, R. P., & Earhart, G. M. (2013). Community-based Argentine tango dance program is associated with increased activity participation among individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 94, 240–249. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, E. R., Spence, D., & Toglia, J. (2018). Feasibility of a cognitive strategy training intervention for people with Parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation , 40, 1127–1134. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1288275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles, G. M., Edwards, D. F., Baum, C., Furniss, J., Skidmore, E., Wolf, T., & Leland, N. E. (2020). Health Policy Perspectives—Making functional cognition a professional priority. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74, 7401090010. 10.5014/ajot.2020.741002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Goodwin, V. A., Richards, S. H., Henley, W., Ewings, P., Taylor, A. H., Campbell, J. L., & Campbell, J. L. (2011). An exercise intervention to prevent falls in people with Parkinson’s disease: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry , 82, 1232–1238. 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariz, G. M., & Forsgren, L. (2011). Activities of daily living and quality of life in persons with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease according to subtype of disease, and in comparison to healthy controls. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica , 123, 20–27. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T., Dijkers, M. P., Whyte, J., Turkstra, L. S., Zanca, J. M., Packel, A., . . . Chen, C. (2019). A theory-driven system for the specification of rehabilitation treatments. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 100, 172–180. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.09.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Boutron, I., . . . Eldridge, S. (2016). A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. In J. Chandler, J. McKenzie, I. Boutron, & V. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane methods (pp. 29–31). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 10(Suppl. 1). 10.1002/14651858.CD201601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). Wiley. 10.1002/9781119536604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Hindle, J. V., Watermeyer, T. J., Roberts, J., Brand, A., Hoare, Z., Martyr, A., & Clare, L. (2018). Goal-orientated cognitive rehabilitation for dementias associated with Parkinson’s disease—A pilot randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 33, 718–728. 10.1002/gps.4845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepac, N., Trkulja, V., Relja, M., & Babić, T. (2008). Is quality of life in non-demented Parkinson’s disease patients related to cognitive performance? A clinic-based cross-sectional study. European Journal of Neurology , 15, 128–133. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudlicka, A., Hindle, J. V., Spencer, L. E., & Clare, L. (2018). Everyday functioning of people with Parkinson’s disease and impairments in executive function: A qualitative investigation. Disability and Rehabilitation , 40, 2351–2363. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1334240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, I. H., Walton, C. C., Hallock, H., Lewis, S. J., Valenzuela, M., & Lampit, A. (2015). Cognitive training in Parkinson disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology , 85, 1843–1851. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Li, F., Harmer, P., Liu, Y., Eckstrom, E., Fitzgerald, K., Stock, R., & Chou, L. S. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of patient-reported outcomes with tai chi exercise in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders , 29, 539–545. 10.1002/mds.25787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras, C., Beck, J. C., Bower, J. H., Roberts, E., Ritz, B., Ross, G. W., . . . Tanner, C. M.; Parkinson’s Foundation P4 Group. (2018). Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinson’s Disease , 4, 21. 10.1038/s41531-018-0058-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G.; PRISMA Group. (2010). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery , 8, 336–341. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nackaerts, E., Heremans, E., Vervoort, G., Smits-Engelsman, B. C., Swinnen, S. P., Vandenberghe, W., . . . Nieuwboer, A. (2016). Relearning of writing skills in Parkinson’s disease after intensive amplitude training. Movement Disorders , 31, 1209–1216. 10.1002/mds.26565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nakae, H., & Tsushima, H. (2014). Effects of home exercise on physical function and activity in home care patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Physical Therapy Science , 26, 1701–1706. 10.1589/jpts.26.1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nascimento, C. M. C., Ayan, C., Cancela, J. M., Gobbi, L. T. B., Gobbi, S., & Stella, F. (2014). Effect of a multimodal exercise program on sleep disturbances and instrumental activities of daily living performance on Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatrics and Gerontology International , 14, 259–266. 10.1111/ggi.12082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d). Quality assessment tool for before–after (pre–post) studies with no control group. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. (2009). The Oxford 2009 levels of evidence. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- *París, A. P., Saleta, H. G., de la Cruz Crespo Maraver, M., Silvestre, E., Freixa, M. G., Torrellas, C. P., . . . Bayés, A. R. (2011). Blind randomized controlled study of the efficacy of cognitive training in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders , 26, 1251–1258. 10.1002/mds.23688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirogovsky, E., Schiehser, D. M., Obtera, K. M., Burke, M. M., Lessig, S. L., Song, D. D., . . . Filoteo, J. V. (2014). Instrumental activities of daily living are impaired in Parkinson’s disease patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology , 28, 229–237. 10.1037/neu0000045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pretzer-Aboff, I., Galik, E., & Resnick, B. (2011). Feasibility and impact of a function focused care intervention for Parkinson’s disease in the community. Nursing Research , 60, 276–283. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318221bb0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Reuter, I., Mehnert, S., Leone, P., Kaps, M., Oechsner, M., & Engelhardt, M. (2011). Effects of a flexibility and relaxation programme, walking, and Nordic walking on Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Aging Research , 2011, 232473. 10.4061/2011/232473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, I., Mehnert, S., Sammer, G., Oechsner, M., & Engelhardt, M. (2012). Efficacy of a multimodal cognitive rehabilitation including psychomotor and endurance training in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Aging Research , 2012, 235765. 10.1155/2012/235765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ridgel, A. L., Walter, B. L., Tatsuoka, C., Walter, E. M., Colón-Zimmermann, K., Welter, E., & Sajatovic, M. (2016). Enhanced exercise therapy in Parkinson’s disease: A comparative effectiveness trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport , 19, 12–17. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L. M., Gruber-Baldini, A. L., Anderson, K. E., Vaughan, C. G., Reich, S. G., Fishman, P. S., & Weiner, W. J. (2008). The evolution of disability in Parkinson disease. Movement Disorders , 23, 790–796. 10.1002/mds.21879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sturkenboom, I. H. W. M., Graff, M. J. L., Hendriks, J. C. M., Veenhuizen, Y., Munneke, M., Bloem, B. R., & Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M. W.; OTiP Study Group. (2014). Efficacy of occupational therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurology , 13, 557–566. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70055-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Grade definitions. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions

- *van Nimwegen, M., Speelman, A. D., Overeem, S., van de Warrenburg, B. P., Smulders, K., Dontje, M. L., . . . Munneke, M.; ParkFit Study Group. (2013). Promotion of physical activity and fitness in sedentary patients with Parkinson’s disease: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 346, f576. 10.1136/bmj.f576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlagsma, T. T., Duits, A. A., Dijkstra, H. T., van Laar, T., & Spikman, J. M. (2018). Effectiveness of ReSET; a strategic executive treatment for executive dysfunctioning in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30, 67–84. 10.1080/09602011.2018.1452761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, J. (2014). Contributions of treatment theory and enablement theory to rehabilitation research and practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 95(Suppl.), S17–S23. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, J., & Hart, T. (2003). It’s more than a black box; it’s a Russian doll: Defining rehabilitation treatments. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 82, 639–652. 10.1097/01.PHM.0000078200.61840.2D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: More active people for a healthier world. https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/global-action-plan-2018-2030/en/

- Zanca, J. M., Turkstra, L. S., Chen, C., Packel, A., Ferraro, M., Hart, T., . . . Dijkers, M. P. (2019). Advancing rehabilitation practice through improved specification of interventions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , 100, 164–171. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.09.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ziliotto, A., Cersosimo, M. G., & Micheli, F. E. (2015). Handwriting rehabilitation in Parkinson disease: A pilot study. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine , 39, 586–591. 10.5535/arm.2015.39.4.586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]